Multi-Ecohydrological Interactions Between Groundwater and Vegetation of Groundwater-Dependent Ecosystems in Semi-Arid Regions: A Case Study in the Hailiutu River Basin

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

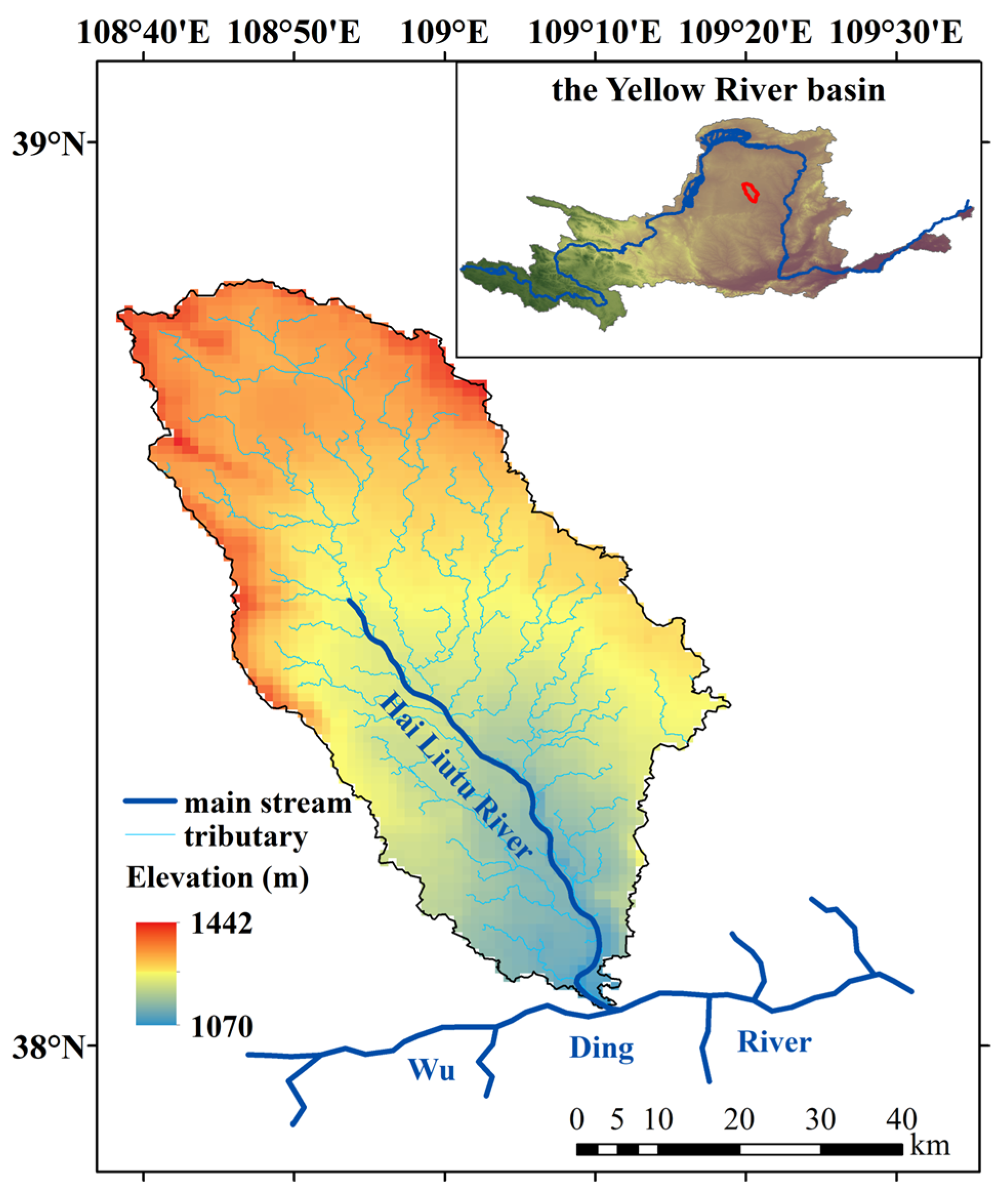

2.1. Study Area

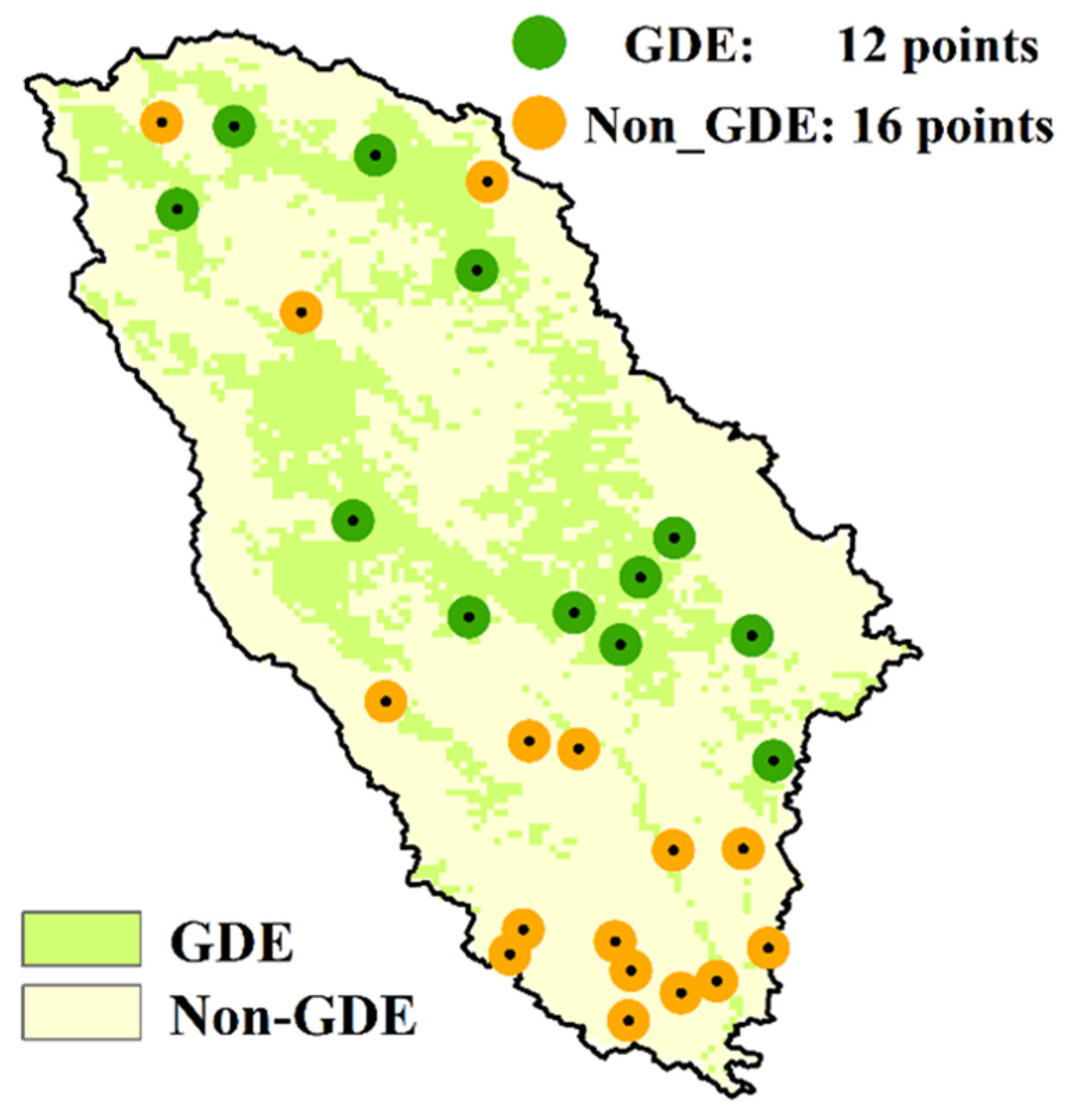

2.2. Field Survey of Vegetation in GDE

2.3. Groundwater and Vegetation Changes

3. Methods

3.1. Trend Analysis

3.2. Partial Correlation Analysis

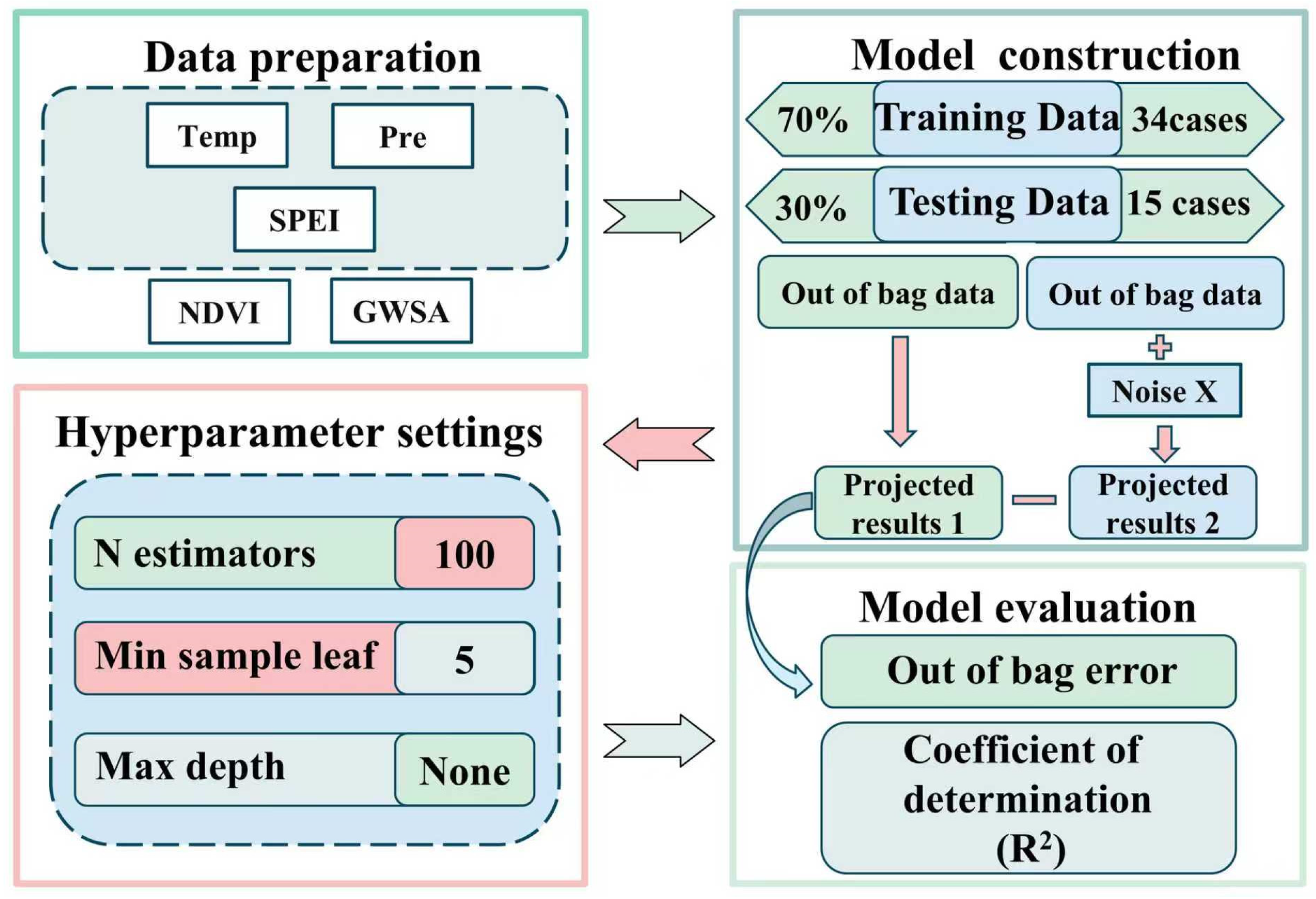

3.3. Random Forest Analysis

4. Result

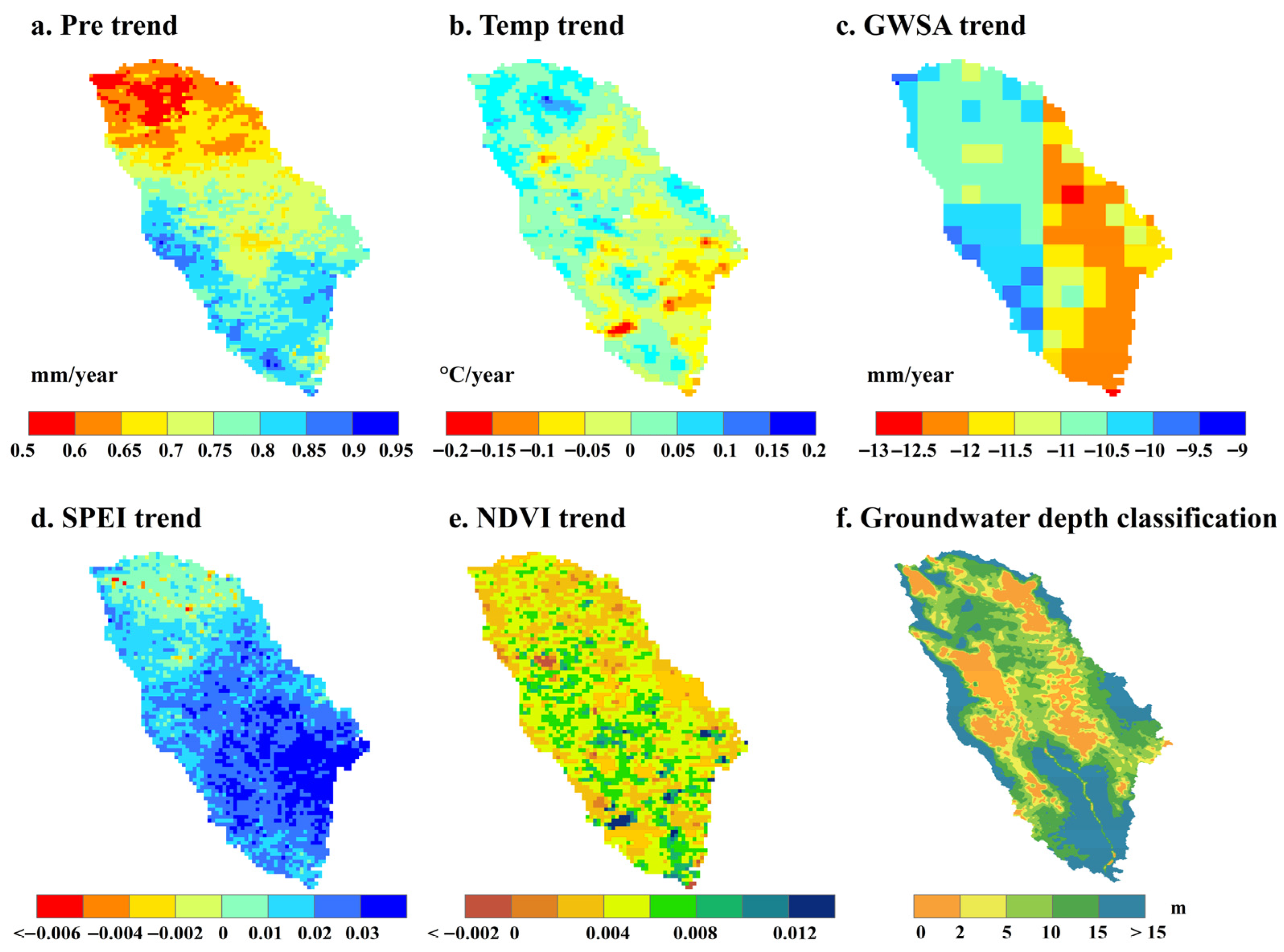

4.1. Spatiotemporal Changes in Meteorological and Hydrological Variables

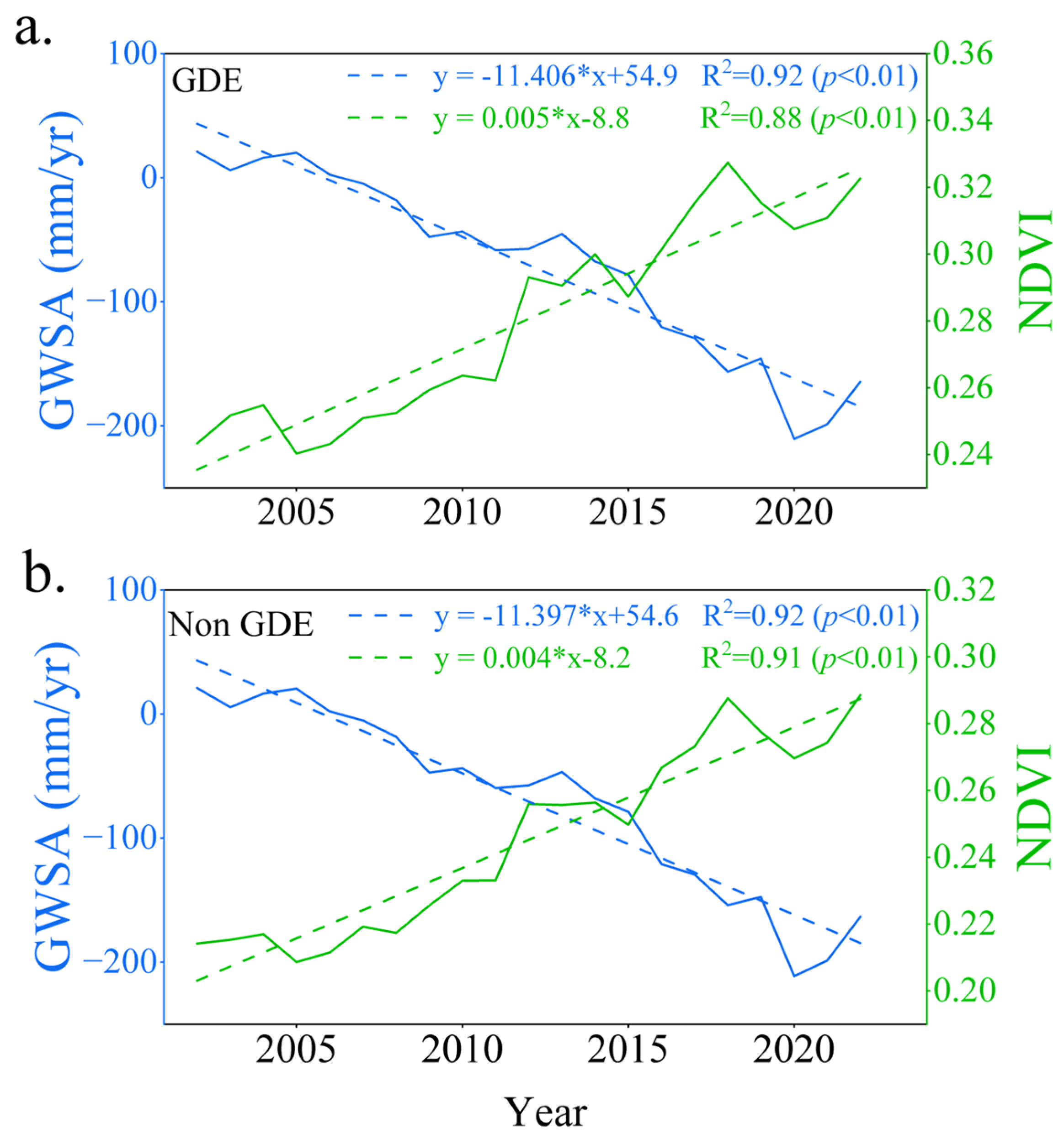

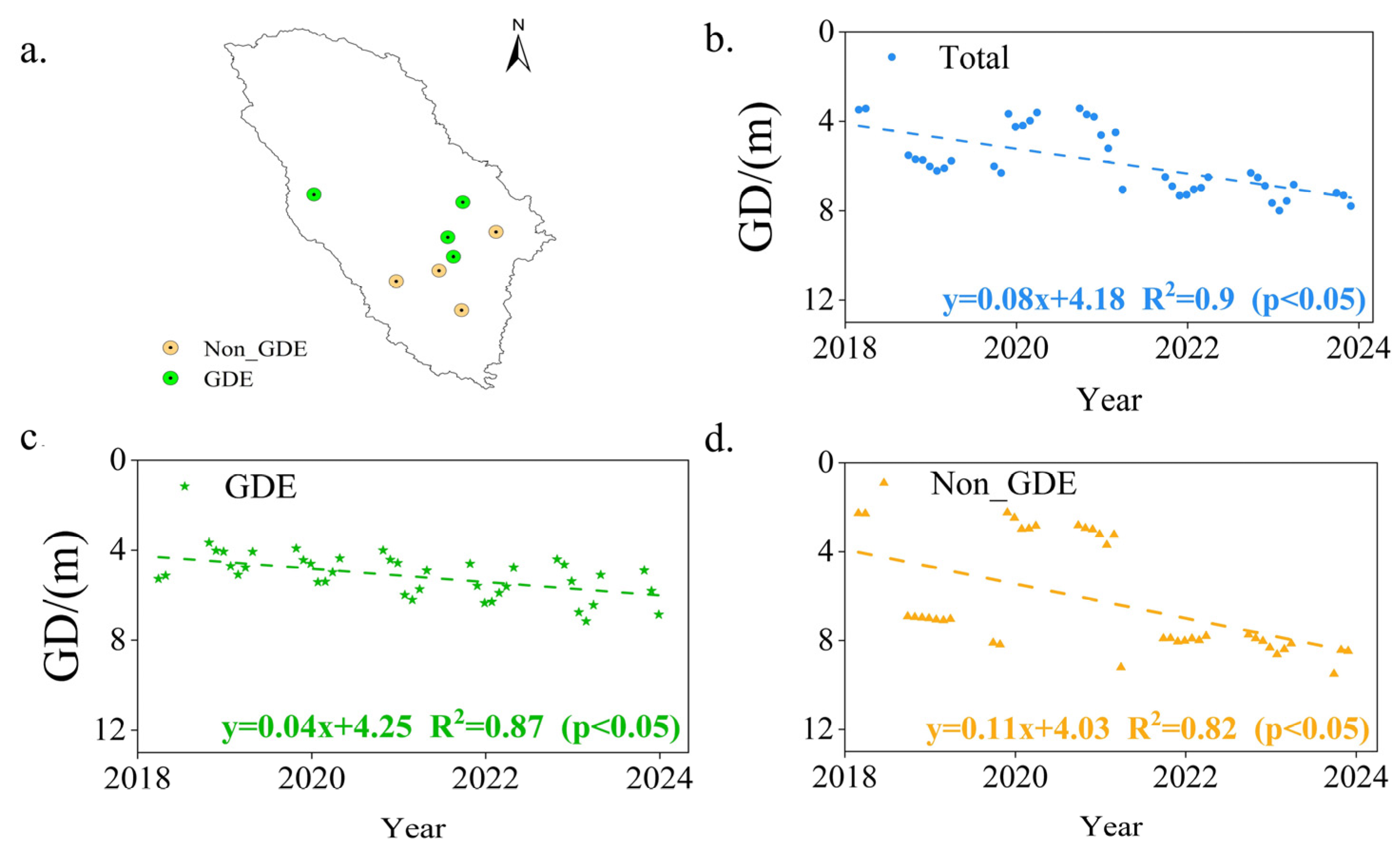

4.2. Temporal Changes in Groundwater and Vegetation of GDE and Non-GDE Area

4.3. Drivers of Vegetation and Groundwater Variations: A Cross-Validation Analysis Using Partial Correlation and Random Forest Models

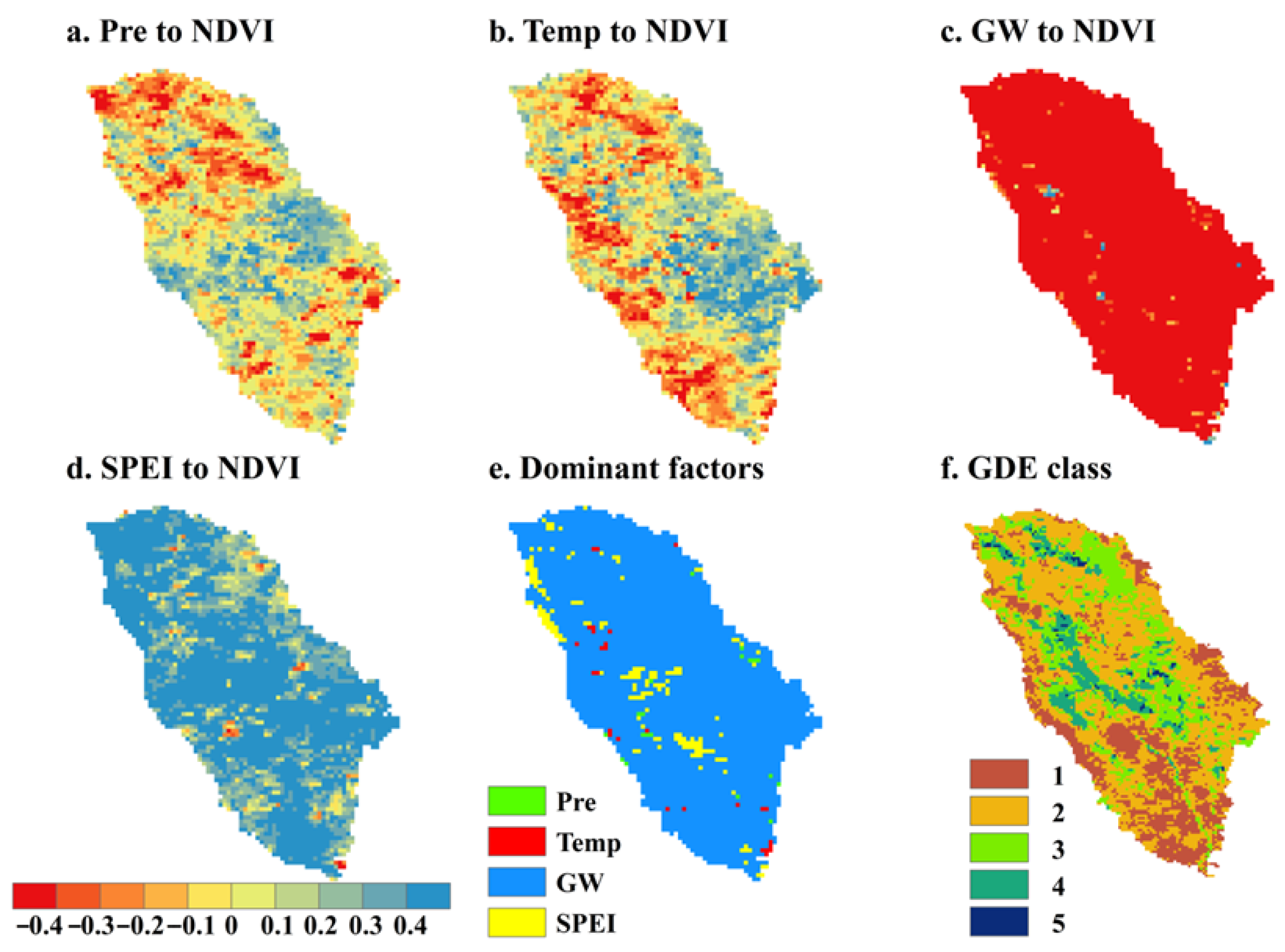

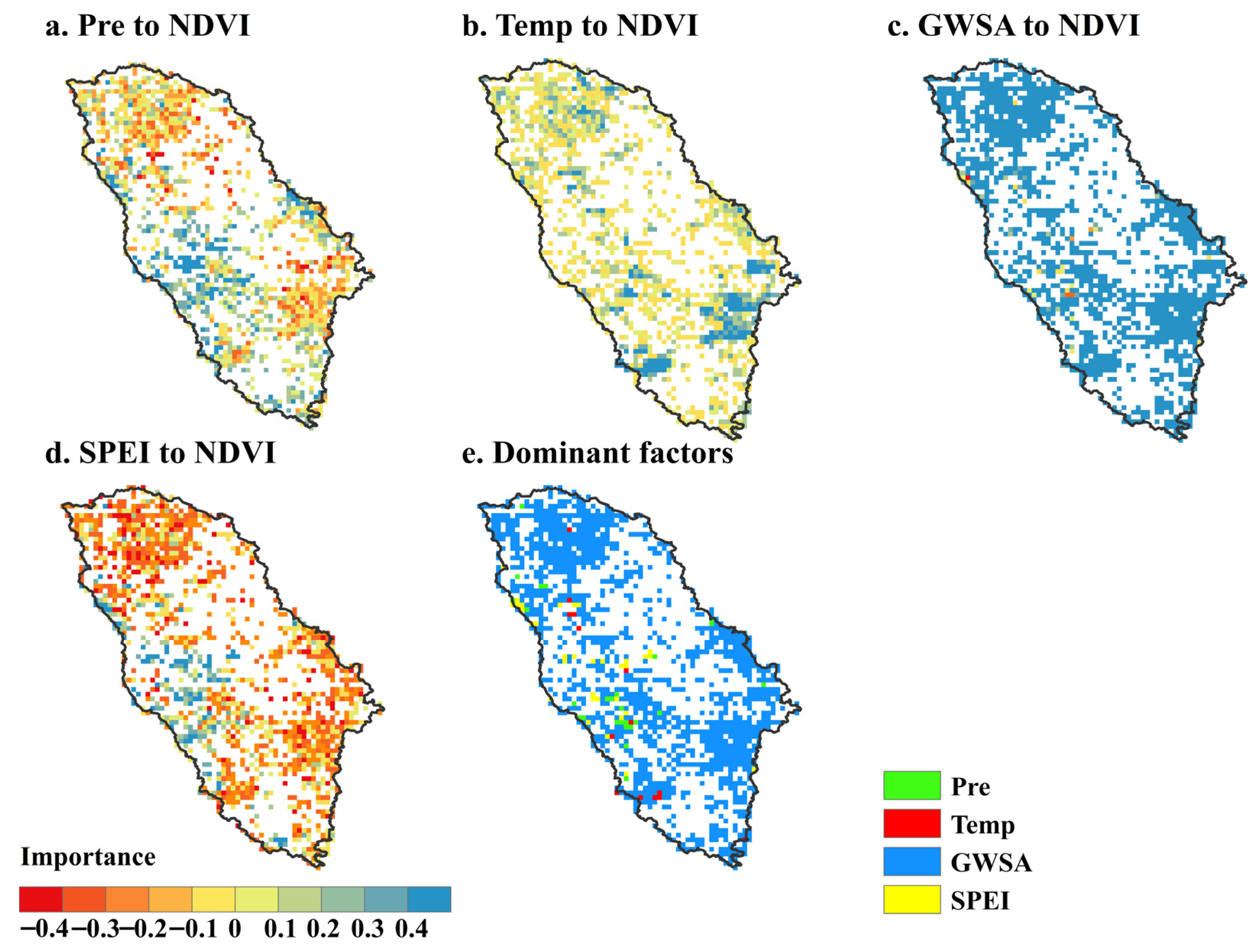

4.3.1. Vegetation Responses to Climate and Groundwater Storage Changes in GDE and Non-GDE

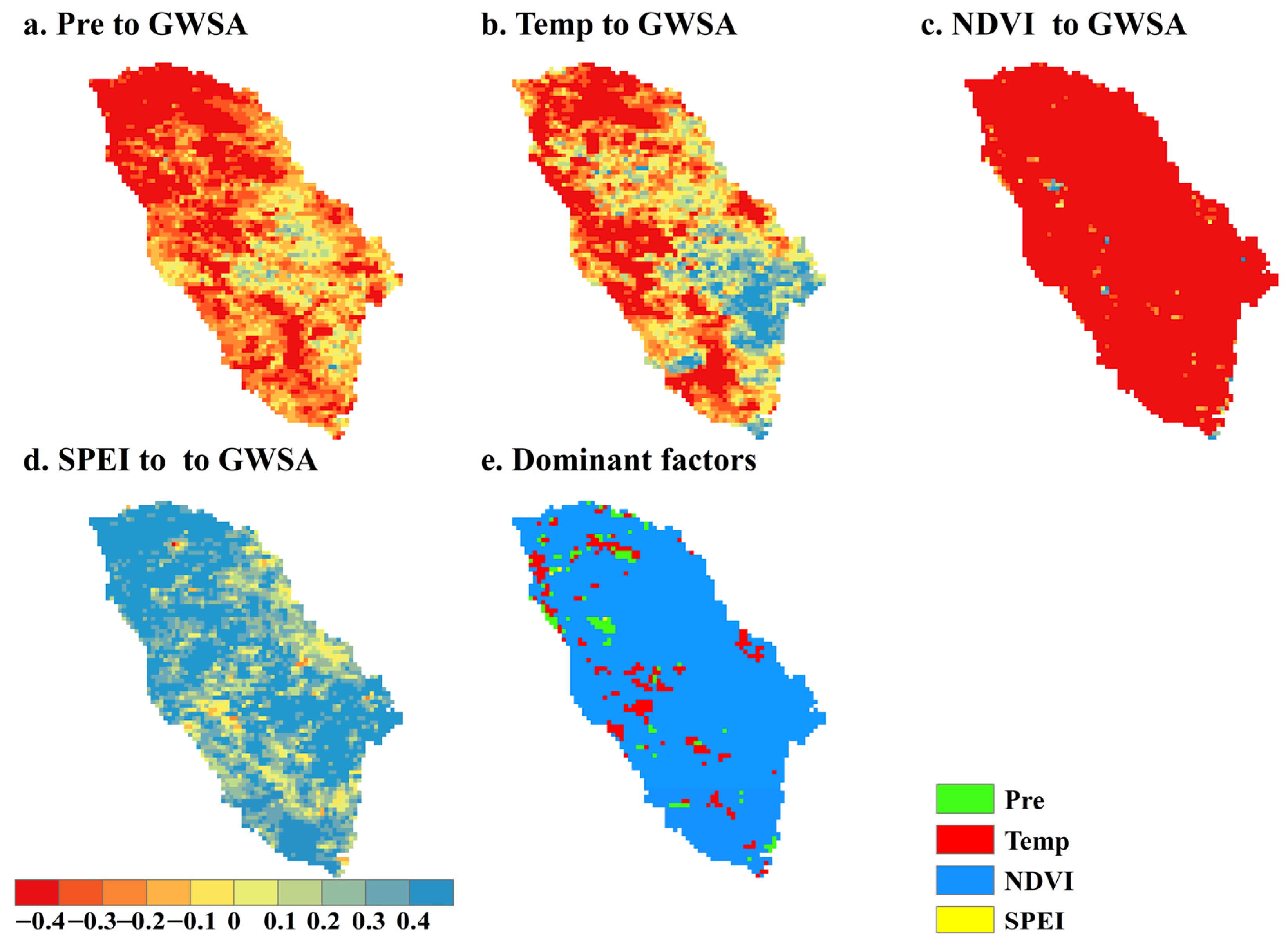

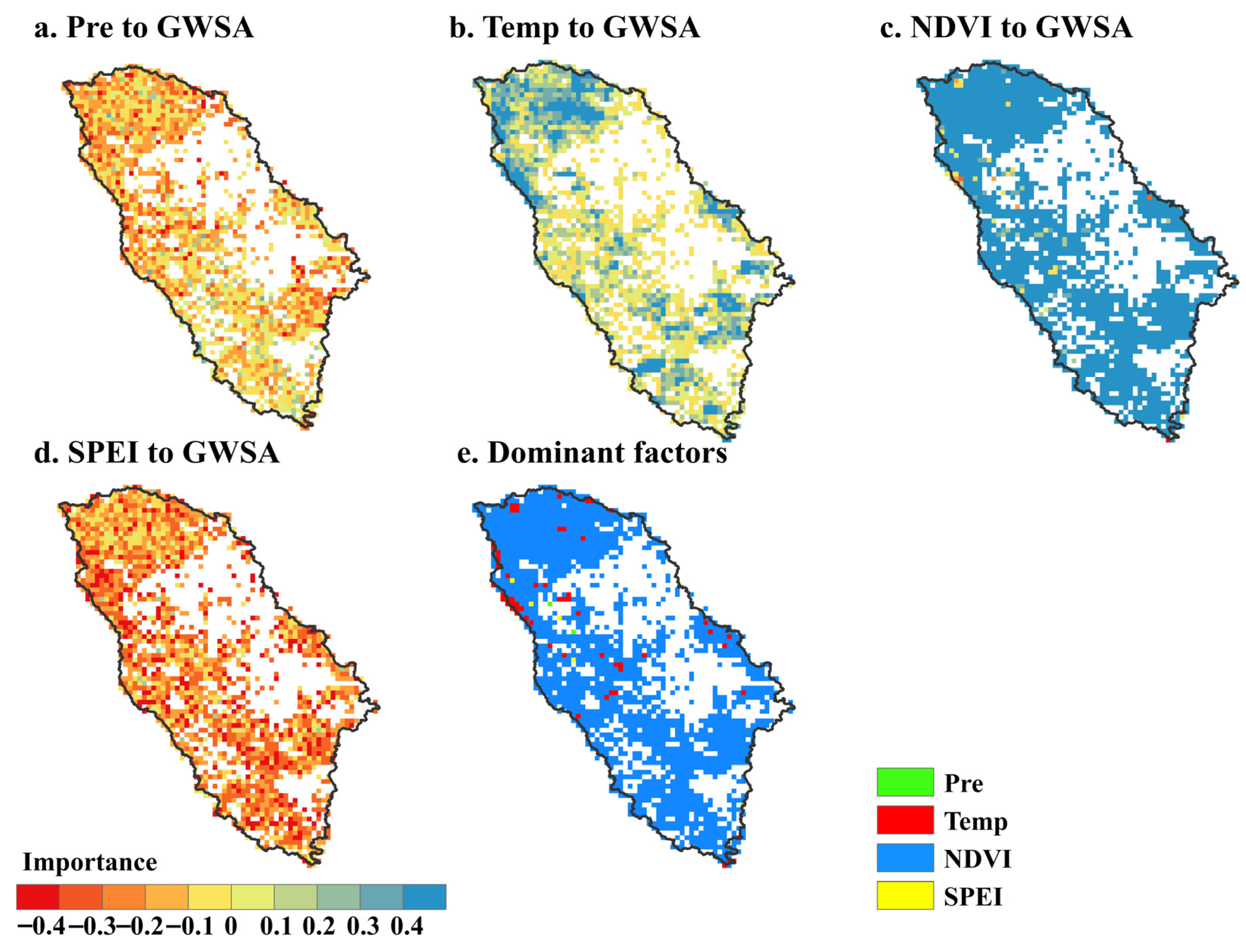

4.3.2. Groundwater Responses to Climate and NDVI Changes in GDE and Non-GDE

4.4. Model Validation and Uncertainty Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Q.; Ye, A.; Wada, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J. Climate change leads to an expansion of global drought-sensitive area. J. Hydrol. 2024, 632, 130874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Mao, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; Lin, Q. Dynamic simulation of land use change and assessment of carbon storage based on climate change scenarios at the city level: A case study of Bortala, China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 134, 108499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Q.; Shao, Z.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, W.; Feng, X.; Lv, X.; Ding, Q.; Cai, B.; Altan, O. Evolution of soil salinization under the background of landscape patterns in the irrigated northern slopes of Tianshan Mountains, Xinjiang, China. Catena 2021, 206, 105561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condon, L.E.; Atchley, A.L.; Maxwell, R.M. Evapotranspiration depletes groundwater under warming over the contiguous United States. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kløve, B.; Ala-Aho, P.; Bertrand, G.; Gurdak, J.J.; Kupfersberger, H.; Kværner, J.; Muotka, T.; Mykrä, H.; Preda, E.; Rossi, P.; et al. Climate change impacts on groundwater and dependent ecosystems. J. Hydrol. 2014, 518, 250–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde, M.M.; Albano, C.M.; Huggins, X.; Klausmeyer, K.R.; Morton, C.; Sharman, A.; Zaveri, E.; Saito, L.; Freed, Z.; Howard, J.K.; et al. Groundwater-dependent ecosystem map exposes global dryland protection needs. Nature 2024, 632, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, Y.; Huo, J.; Han, G.; Hu, R.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Groh, J.; Zhang, Z. Groundwater Altered Water Balance and Plant Water Use Efficiency in Desert Ecosystems. Water Resour. Res. 2025, 61, e2025WR040545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Guan, H.; Zhao, W.; Yang, Y.; Li, S. Groundwater facilitated water-use efficiency along a gradient of groundwater depth in arid northwestern China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2017, 233, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhou, P.; Song, X.; Sun, W.; Li, Y.; Song, S.; Zhang, Y. Dynamics of solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence (SIF) and its response to meteorological drought in the Yellow River Basin. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 360, 121023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Mason, J.A.; Lu, H. Vegetated dune morphodynamics during recent stabilization of the Mu Us dune field, north-central China. Geomorphology 2015, 228, 486–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Sun, H.; Dong, Z.; Liu, Z.; Li, C.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Li, L. Temporal variation of the wind environment and its possible causes in the Mu Us Dunefield of Northern China, 1960–2014. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2018, 135, 1017–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Chunyu, X.; Zhang, D.; Chen, X.; Ochoa, C.G. A framework to assess the impact of ecological water conveyance on groundwater-dependent terrestrial ecosystems in arid inland river basins. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 709, 136155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ge, J.; Guo, W.; Cao, Y.; Chen, C.; Luo, X.; Yang, L.; Wang, S. Revisiting Biophysical Impacts of Greening on Precipitation Over the Loess Plateau of China Using WRF With Water Vapor Tracers. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2023, 50, e2023GL102809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Tian, L.; Yang, Y.; He, X. Revegetation Does Not Decrease Water Yield in the Loess Plateau of China. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2022GL098025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, X.; Li, Z. Plants extend root deeper rather than increase root biomass triggered by critical age and soil water depletion. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 914, 169689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etesami, H.; Chen, Y. Chapter 28–Adapting to arid conditions: The Interplay of Plant Roots, Microbial Communities, and Exudates in the Face of Drought Challenges. In Sustainable Agriculture under Drought Stress; Etesami, H., Chen, Y., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025; pp. 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Niu, J.; Svenning, J.-C. Ecological restoration is the dominant driver of the recent reversal of desertification in the Mu Us Desert (China). J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 268, 122241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Fu, B.; Piao, S.; Wang, S.; Ciais, P.; Zeng, Z.; Lü, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Li, Y.; Jiang, X.; et al. Revegetation in China’s Loess Plateau is approaching sustainable water resource limits. Nat. Clim. Change 2016, 6, 1019–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhai, H.; Zhang, X.; Dong, X.; Hu, J.; Ma, J.; Sun, W. Time-lag and accumulation responses of vegetation growth to average and extreme precipitation and temperature events in China between 2001 and 2020. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 945, 174084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Guo, J.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, S. How did the Chinese Loess Plateau turn green from 2001 to 2020? An explanation using satellite data. Catena 2022, 214, 106246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, X.; Jia, G.; Liu, Z.; Sun, L.; Zheng, P.; Zhu, X. Grassland soil moisture fluctuation and its relationship with evapotranspiration. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 131, 108196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuxi, W.; Li, P.; Yuemin, Y.; Tiantian, C. Global Vegetation-Temperature Sensitivity and Its Driving Forces in the 21st Century. Earth’s Future 2024, 12, e2022EF003395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Yang, P.; Vrieling, A.; Tol, C.V.D. Vegetation optimal temperature modulates global vegetation season onset shifts in response to warming climate. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denissen, J.M.C.; Teuling, A.J.; Pitman, A.J.; Koirala, S.; Migliavacca, M.; Li, W.; Reichstein, M.; Winkler, A.J.; Zhan, C.; Orth, R. Widespread shift from ecosystem energy to water limitation with climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilong, P.; Jingyun, F.; Wei, J.; Qinghua, G.; Jinhu, K.; Shu, T. Variation in a Satellite-Based Vegetation Index in Relation to Climate in China. J. Veg. Sci. 2004, 15, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Wang, X.S.; Zhou, Y.; Qian, K.; Wan, L.; Eamus, D.; Tao, Z. Groundwater-dependent distribution of vegetation in Hailiutu River catchment, a semi-arid region in China. Ecohydrology 2012, 6, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, S.; Hannah, D.M.; Sadler, J.P.; Wood, P.J. Ecohydrology on the edge: Interactions across the interfaces of wetland, riparian and groundwater-based ecosystems. Ecohydrology 2011, 4, 477–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde, M.M.; Stella, J.C.; Singer, M.B.; Roberts, D.A.; Caylor, K.K.; Albano, C.M. Establishing ecological thresholds and targets for groundwater management. Nat. Water 2024, 2, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, P.U.; Heuzard, A.G.; Le, T.X.H.; Zhao, J.; Yin, R.; Shang, C.; Fan, C. The impacts of climate change on groundwater quality: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, S.A.; Irvine, D.J.; Rau, G.C.; Bayer, P.; Menberg, K.; Blum, P.; Jamieson, R.C.; Griebler, C.; Kurylyk, B.L. Global groundwater warming due to climate change. Nat. Geosci. 2024, 17, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, B.R.; Hose, G.C.; Eamus, D.; Licari, D. Valuation of groundwater-dependent ecosystems: A functional methodology incorporating ecosystem services. Aust. J. Bot. 2006, 54, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, J.K.; Dooley, K.; Brauman, K.A.; Klausmeyer, K.R.; Rohde, M.M. Ecosystem services produced by groundwater dependent ecosystems: A framework and case study in California. Front. Water 2023, 5, 1115416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Wang, M.; Liu, K.; Wang, B. High-resolution Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) reveals trends in drought and vegetation water availability in China. Geogr. Sustain. 2025, 6, 100228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Yang, T.; Fu, J.; Song, W. Utility of the standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index (SPEI) to detect agricultural droughts over China. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 58, 102190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Zhang, J.; Gu, X.; Gao, H.; Yang, B.; Yang, X.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, T.; Yin, L.; Wang, X. Groundwater dependent ecosystems assessment in catchment scale of semi-arid regions: A case study in the Hailiutu catchment of the Ordos Plateau. Geol. China 2024, 51, 1855–1867. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Wenninger, J.; Uhlenbrook, S.; Wang, X.; Wan, L. Groundwater and surface-water interactions and impacts of human activities in the Hailiutu catchment, northwest China. Hydrogeol. J. 2017, 25, 1341–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wenninger, J.; Yang, Z.; Yin, L.; Huang, J.; Hou, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, D.; Uhlenbrook, S. Groundwater–surface water interactions, vegetation dependencies and implications for water resources management in the semi-arid Hailiutu River catchment, China – a synthesis. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 17, 2435–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.M.; Guo, R.H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, Y.X.; Zhang, D.R.; Yang, Z. Response of vegetation pattern to different landform and water-table depth in Hailiutu River basin, Northwestern China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2014, 71, 4889–4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wu, Z.; Wang, P.; Wu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, J.; Yu, J.; Wang, H.; Guan, X.; Xu, H.; et al. Plant-groundwater interactions in drylands: A review of current research and future perspectives. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2023, 341, 109636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, G.; Guan, Y.; Zhang, D.; Yu, B.; Zhu, J. The Impacts of Climate Variability and Land Use Change on Streamflow in the Hailiutu River Basin. Water 2018, 10, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Save, H.; Bettadpur, S.; Tapley, B.D. High-resolution CSR GRACE RL05 mascons. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2016, 121, 7547–7569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Save, H. CSR GRACE and GRACE-FO RL06 Mascon Solutions v02; University of Texas at Austin: Austin, TX, USA, 2020; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.-W.; Famiglietti, J.S.; Purdy, A.J.; Adams, K.H.; McEvoy, A.L.; Reager, J.T.; Bindlish, R.; Wiese, D.N.; David, C.H.; Rodell, M. Groundwater depletion in California’s Central Valley accelerates during megadrought. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Xu, T.; Yin, W.; Bateni, S.M.; Jun, C.; Kim, D.; Liu, S.; Xu, Z.; Ming, W.; Wang, J. A machine learning downscaling framework based on a physically constrained sliding window technique for improving resolution of global water storage anomaly. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 313, 114359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, R.; Leblanc, S.G. Parametric (modified least squares) and non-parametric (Theil–Sen) linear regressions for predicting biophysical parameters in the presence of measurement errors. Remote Sens. Environ. 2005, 95, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, P.K. Estimates of the Regression Coefficient Based on Kendall’s Tau. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1968, 63, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.; Xie, X.; Zhu, B.; Wang, Y. The relative contribution of vegetation greening to the hydrological cycle in the Three-North region of China: A modelling analysis. J. Hydrol. 2020, 591, 125689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wei, W.; Chen, L.; Chen, W.; Wang, J. Response of temporal variation of soil moisture to vegetation restoration in semi-arid Loess Plateau, China. Catena 2014, 115, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, H.B. Nonparametric Tests Against Trend. Econometrica 1945, 13, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isabona, J.; Imoize, A.L.; Kim, Y. Machine Learning-Based Boosted Regression Ensemble Combined with Hyperparameter Tuning for Optimal Adaptive Learning. Sensors 2022, 22, 3776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Gao, M.; Dong, J. The use of random forest to identify climate and human interference on vegetation coverage changes in southwest China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 144, 109463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.C.-W.; Paelinckx, D. Evaluation of Random Forest and Adaboost tree-based ensemble classification and spectral band selection for ecotope mapping using airborne hyperspectral imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 2999–3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shen, H.; Huang, T.; Wu, Y.; Guo, B.; Liu, Z.; Luo, H.; Tang, J.; Zhou, H.; Wang, L.; et al. Improved random forest algorithms for increasing the accuracy of forest aboveground biomass estimation using Sentinel-2 imagery. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 159, 111752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Zhang, G.; Wang, T.; Ye, Y.; Zhao, Q. Geographically Weighted Random Forest Based on Spatial Factor Optimization for the Assessment of Landslide Susceptibility. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, B.L.; Carey, L.D.; Amiot, C.G.; Mecikalski, R.M.; Roeder, W.P.; McNamara, T.M.; Blakeslee, R.J. A Random Forest Method to Forecast Downbursts Based on Dual-Polarization Radar Signatures. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fildes, S.G.; Doody, T.M.; Bruce, D.; Clark, I.F.; Batelaan, O. Mapping groundwater dependent ecosystem potential in a semi-arid environment using a remote sensing-based multiple-lines-of-evidence approach. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2023, 16, 375–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, T.; Wang, X.-S.; Han, P.-F. Controls of groundwater-dependent vegetation coverage in the yellow river basin, china: Insights from interpretable machine learning. J. Hydrol. 2024, 631, 130747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Luo, W.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L. Spatiotemporal Variations and Driving Mechanisms of Vegetation Phenology Across Different Vegetation Types in Yan Mountain from 2000 to 2022. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Wen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Lin, Z.; Han, P.; Shi, H.; Wang, Z.; Su, T. Vegetation response to changes in climate across different climate zones in China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 155, 110932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Du, M.; Lu, J.; Chen, X. Drought Amplifies the Suppressive Effect of Afforestation on Net Primary Productivity in Semi-Arid Ecosystems: A Case Study of the Yellow River Basin. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Qin, H.; Zhang, X.; Xue, H.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H. The Impact of Meteorological Drought at Different Time Scales from 1986 to 2020 on Vegetation Changes in the Shendong Mining Area. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, W.; Wang, L.; Smith, W.K.; Chang, Q.; Wang, H.; D’Odorico, P. Observed increasing water constraint on vegetation growth over the last three decades. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Lü, Y.; Jiang, X. Increased precipitation and vegetation cover synergistically enhanced the availability and effectiveness of water resources in a dryland region. J. Hydrol. 2025, 654, 132812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Cui, A.; Ji, R.; Huang, S.; Li, P.; Chen, N.; Shao, Z. Spatiotemporal Responses of Global Vegetation Growth to Terrestrial Water Storage. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Eldridge, D.J.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Guirado, E. Highly protected areas buffer against aridity thresholds in global drylands. Nat. Plants 2025, 11, 2041–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belgrano, A.; Cucchiella, F.; Jiang, D.; Rotilio, M. Anthropogenic modifications: Impacts and conservation strategies. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Tan, L.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Y.; Duan, Z.; Xu, Y.; Gao, C. Impacts of climate change and anthropogenic activities on vegetation change: Evidence from typical areas in China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 126, 107648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Fan, L.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Liu, D.; Zhao, F. Future climate change exacerbates streamflow depletion in the Wei River Basin, China. J. Hydrol. 2025, 663, 134146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasechko, S.; Seybold, H.; Perrone, D.; Fan, Y.; Shamsudduha, M.; Taylor, R.G.; Fallatah, O.; Kirchner, J.W. Rapid groundwater decline and some cases of recovery in aquifers globally. Nature 2024, 625, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.A.; Bailey, R.T.; White, J.T.; Arnold, J.G.; White, M.J. Estimation of groundwater storage loss using surface–subsurface hydrologic modeling in an irrigated agricultural region. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocker, B.D.; Tumber-Dávila, S.J.; Konings, A.G.; Anderson, M.C.; Hain, C.; Jackson, R.B. Global patterns of water storage in the rooting zones of vegetation. Nat. Geosci. 2023, 16, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, R.W.H.; Niswonger, R.G.; Ulrich, C.; Varadharajan, C.; Siirila-Woodburn, E.R.; Williams, K.H. Declining groundwater storage expected to amplify mountain streamflow reductions in a warmer world. Nat. Water 2024, 2, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liu, J.; He, W.; Xu, P.; Nguyen, N.T.; Lv, Y.; Huang, C. Shifted vegetation resilience from loss to gain driven by changes in water availability and solar radiation over the last two decades in Southwest China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2025, 368, 110543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Zheng, C.; Jia, L.; Menenti, M.; Lu, J.; Chen, Q. Evaluating the Performance of Irrigation Using Remote Sensing Data and the Budyko Hypothesis: A Case Study in Northwest China. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yue, Y.; Cui, J.; Liu, H.; Shi, L.; Liang, B.; Li, Q.; Wang, K. Precipitation sensitivity of vegetation growth in southern China depends on geological settings. J. Hydrol. 2024, 643, 131916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Lian, X.; Huntingford, C.; Gimeno, L.; Wang, T.; Ding, J.; He, M.; Xu, H.; Chen, A.; Gentine, P.; et al. Global water availability boosted by vegetation-driven changes in atmospheric moisture transport. Nat. Geosci. 2022, 15, 982–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Liu, M.; Li, Y.; Guan, C. Response of total primary productivity of vegetation to meteorological drought in arid and semi-arid regions of China. J. Arid Environ. 2025, 228, 105346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, T.; Feng, P.; Liu, W. Response of vegetation to SPI and driving factors in Chinese mainland. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 291, 108625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Lv, S.; Wang, F.; Xu, J.; Zhao, H.; Tang, L.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H. Investigation into the temporal impacts of drought on vegetation dynamics in China during 2000 to 2022. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; O’Connor, D.; Hou, D.; Jin, Y.; Li, G.; Zheng, C.; Ok, Y.S.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Luo, J. Groundwater depletion and contamination: Spatial distribution of groundwater resources sustainability in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 672, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Li, H.; Wu, D.; Chen, W.; Zhao, X.; Hou, M.; Li, A.; Zhu, Y. LAI-indicated vegetation dynamic in ecologically fragile region: A case study in the Three-North Shelter Forest program region of China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 120, 106932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Wang, S.; Bai, X.; Luo, G.; Wu, L.; Chen, F.; Wang, J.; Li, C.; Yang, Y.; Hu, Z.; et al. Vegetation greening intensified soil drying in some semi-arid and arid areas of the world. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 292, 108103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Zhao, W.; Wang, L.; Feng, Q.; Ding, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X. Variations of deep soil moisture under different vegetation types and influencing factors in a watershed of the Loess Plateau, China. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2016, 20, 3309–3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, B.R.; Fakhreddine, S.; Rateb, A.; de Graaf, I.; Famiglietti, J.; Gleeson, T.; Grafton, R.Q.; Jobbagy, E.; Kebede, S.; Kolusu, S.R.; et al. Global water resources and the role of groundwater in a resilient water future. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, J.A.; Nicholson, E.; Ferrer-Paris, J.R.; Keith, D.A.; Murray, N.J.; Sato, C.F.; Tóth, A.B.; Tolsma, A.; Venn, S.; Asmüssen, M.V.; et al. Assessing risk of ecosystem collapse in a changing climate. Nat. Clim. Change 2025, 15, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, X.; Gleeson, T.; Serrano, D.; Zipper, S.; Jehn, F.; Rohde, M.M.; Abell, R.; Vigerstol, K.; Hartmann, A. Overlooked risks and opportunities in groundwatersheds of the world’s protected areas. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodell, M.; Velicogna, I.; Famiglietti, J.S. Satellite-based estimates of groundwater depletion in India. Nature 2009, 460, 999–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundzewicz, Z.W.; DÖLl, P. Will groundwater ease freshwater stress under climate change? Hydrol. Sci. J. 2009, 54, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchett, D.; Manning, S.J. Response of an Intermountain Groundwater-Dependent Ecosystem to Water Table Drawdown. West. North Am. Nat. 2012, 72, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde, M.M.; Biswas, T.; Housman, I.W.; Campbell, L.S.; Klausmeyer, K.R.; Howard, J.K. A Machine Learning Approach to Predict Groundwater Levels in California Reveals Ecosystems at Risk. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Vegetation Type | Number |

|---|---|

| Tree | 8 |

| Shrub | 12 |

| Herb | 8 |

| Vegetation | Common Species | Scientific Name |

|---|---|---|

| Tree | Drought Willow, Black Poplar, Korean Pine | Populus angustifolia, Populus nigra, Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica |

| Shrub | Sand Willow, Sand Sagebrush, Nitraria, Calligonum, Small-leaved Caragana, Sabina, Altai Arctic Daisy, Gobi Onion, Sand Blue Thistle | Salix psammophila, Artemisia ordosica, Nitraria tangutorum, Calligonum mongolicum, Caragana microphylla, Sabina przewalskii, Cremanthodium arcticum, Allium gobicum, Echinops setifer |

| Grassland | Feather Grass, Sand Wormwood, Suaeda, Suaeda physophora, Alfalfa | Achnatherum splendens, Artemisia scoparia, Suaeda glauca, Suaeda physophora, Medicago sativa |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zeng, L.; Xu, L.; Song, B.; Wang, P.; Qiao, G.; Wang, T.; Wang, H.; Jing, X. Multi-Ecohydrological Interactions Between Groundwater and Vegetation of Groundwater-Dependent Ecosystems in Semi-Arid Regions: A Case Study in the Hailiutu River Basin. Land 2026, 15, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010060

Zeng L, Xu L, Song B, Wang P, Qiao G, Wang T, Wang H, Jing X. Multi-Ecohydrological Interactions Between Groundwater and Vegetation of Groundwater-Dependent Ecosystems in Semi-Arid Regions: A Case Study in the Hailiutu River Basin. Land. 2026; 15(1):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010060

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Lei, Li Xu, Boying Song, Ping Wang, Gang Qiao, Tianye Wang, Hu Wang, and Xuekai Jing. 2026. "Multi-Ecohydrological Interactions Between Groundwater and Vegetation of Groundwater-Dependent Ecosystems in Semi-Arid Regions: A Case Study in the Hailiutu River Basin" Land 15, no. 1: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010060

APA StyleZeng, L., Xu, L., Song, B., Wang, P., Qiao, G., Wang, T., Wang, H., & Jing, X. (2026). Multi-Ecohydrological Interactions Between Groundwater and Vegetation of Groundwater-Dependent Ecosystems in Semi-Arid Regions: A Case Study in the Hailiutu River Basin. Land, 15(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010060