Abstract

Traditional scholarship on early Chinese political geography has largely privileged textual analysis, often lacking quantifiable baselines for assessing spatial structure. Addressing this gap, this study utilizes the Shang-Zhou period Shandong region as a focal case to propose a replicable GIS framework—incorporating Kernel Density Analysis (KDA) and Voronoi diagrams—grounded in a null-hypothesis approach. Rather than attempting to simulate theoretical territories, these methods are employed to establish a purely geometric baseline for political space. Central to this study’s findings is the quantification of deviations from this geometric ideal. These measurable discrepancies—manifesting as “Voronoi voids” in mountainous zones and “scale violations” by major powers—serve as empirical indicators for interpreting the tangible impacts of topography, power dynamics, and resource allocation, such as the coastal salt fields identified via KDA. Ultimately, this study demonstrates that this deviation analysis framework functions as a vital quantitative complement to traditional institutional history, effectively elucidating the spatial logic and dynamic evolution of ancient political systems.

1. Introduction

“How China Became China”, a fundamental question probing the origin, formation, and development of Chinese civilization, has been one of the core themes in Chinese historical and archaeological research in recent decades. The Shang and Zhou periods represent a critical stage in the formation and transformation of the spatial order of early Chinese states [1,2,3]. Building on this broad inquiry, this study aims to address a specific and measurable question: how the spatial organization of early states in the Shandong region evolved under the combined influence of environmental constraints and institutional design. To achieve this, this paper proposes a geometric null-hypothesis model based on GIS spatial analysis, establishing a quantitative baseline that enables the measurement of deviations between ritualized ideals of territory (as prescribed in classical texts such as the Li Ji) and empirical political geography reconstructed from archaeological data. This approach transforms qualitative discussions of “ritual versus reality” into a spatially testable framework.

To understand this macro-process of Chinese civilization, it is essential to examine specific regional case studies where these dynamics played out most intensely. The Shandong region offers a unique vantage point. In this context, the question “How Shandong Became Shandong” is not merely rhetorical, but a process-oriented investigation into how geographic environment, political power, and ritual norms jointly structured the spatial order of early states. The Shandong region thus provides a concrete testbed for quantifying the transformation from pluralistic, landscape-bound communities to politically integrated territories.

This macro-historical process is visually manifested in the political-geographical landscape as a transition from “a multitude of Fang states” to “the dominance of powerful vassals”. This involved a shift from a loose, composite state structure comprising fang states to a Fengjian (enfeoffment) system maintained by patriarchal kinship ties, which was subsequently, and gradually, replaced by a centralized system built on geopolitics, bureaucracy, and territoriality [4]. This transformation from many to few and from small to large was not merely the result of military annexation but also a profound revolution in state spatial governance.

Marked by Su [5]’s “regional systems, cultural types” theory, the academic community has gradually broken away from the “unilinear evolutionism” perspective, which had previously regarded the Central Plains as the sole center. Instead, scholarship has come to recognize that Chinese civilization was formed through the long-term, complex, and pluralistic interaction, collision, and integration of multiple regional cultural systems across the vast East Asian continent. Yan [6]’s “multi-petaled flower” model further vividly depicted this process: the Central Plains formed the relative “core” of the flower, yet its flourishing was inseparable from the surrounding regional cultures, or “petals”, which provided support, interaction, and nourishment.

While these foundational theories from the 1980s provided the macro-historical narrative, recent scholarship has shifted towards quantifying these spatial relationships using advanced computational methods. In the last decade, the application of GIS in Chinese archaeology has surged. For instance, Liu et al. [7] utilized hydrological modeling to reveal the correlation between settlement distribution and geomorphology in Shandong. Wang and Cui [8] analyzed the spatiotemporal response of cultures to climate change in the Yellow River basin. More recently, Tian et al. [9] and Tong et al. [10] have employed quantitative spatial analyses to reconstruct the influence ranges of Neolithic-Bronze Age cities in Central China. These recent studies demonstrate a methodological shift from qualitative description to quantitative reconstruction, providing the necessary data foundation for testing classical theories.

It is important to position this study’s quantitative approach within the broader field of computational archaeology. While recent GIS-based studies have made substantial progress in reconstructing ancient settlement systems [9,11], more sophisticated methods for modeling political territory and interaction also exist. Cost-surface analysis and Least-Cost Path (LCP) analysis, for instance, provide more realistic simulations of movement and control by incorporating terrain friction [12,13]. Similarly, Agent-Based Models (ABM) can simulate the complex, bottom-up interactions of social agents [14], and gravity models can model social interaction [15].

In contrast, this study takes a conceptually inverse approach. It does not attempt to simulate this complex reality, but rather to establish a geometric null baseline against which that reality can be measured. The null hypothesis approach adopted here, using the simple Voronoi diagram, provides a more fundamental, easily replicable, and computationally inexpensive baseline.

This inversion of purpose transforms GIS from a descriptive or reconstructive tool into a diagnostic framework. The primary utility shifts from prediction to deviation measurement. That is, from “how states might have interacted” to “how far the historical spatial order diverged from geometric ideality”. The value lies in precisely measuring the tangible impact of the very “real-world” factors (topography, resources, power) that more complex models seek to integrate from the outset.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Geographical Context

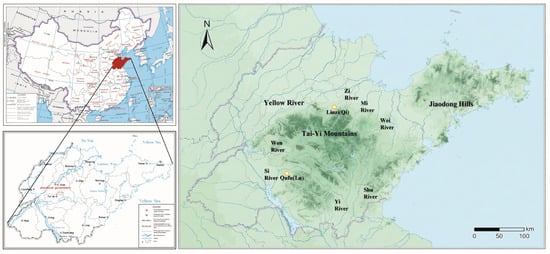

The geographical scope of this study is the Shandong region, roughly corresponding to the “Haidai region” (the area between Mount Tai and the Bohai Sea) in ancient geography. Geographically, it is located in and around the Tai-Yi Mountain range. It is bordered by the Bohai and Yellow Seas to the east, extends west to the ancient Ji River basin west of Mount Tai, reaches south to the northern edge of the Jiang-Huai River basin, and extends north to the vicinity of the ancient Yellow River channel. It is a vast area nourished by river systems such as the Yellow, Ji, Huai, and Yi-Shu rivers.

The Shandong region can be broadly divided into three distinct geographical units: the central mountainous and hilly region dominated by the Tai-Yi Mountain system; its periphery, which is encircled by alluvial plains (the southwestern and northwestern plains) and coastal lowlands; and the gently undulating hilly region of the east (the Jiaodong hilly region). The Tai-Yi Mountain range, acting as the core watershed, is the region’s primary geographical constraint (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Map of the Study Area.

This physical stage is profoundly influenced by two critical waterways: the Yellow River and the Ji River. The Yellow River’s frequent course changes and devastating floods have historically exerted an enormous, often negative, impact on settlement distribution. In contrast, the Ji River’s stable course and abundant water volume made its basin more suitable for long-term human settlement. As the GIS analysis will demonstrate (see Section 3 and Section 4), these geographical features, particularly the central mountains and the fertile plains, are the single most important factor explaining the deviation of reality from the idealized geometric models.

During the Shang and Zhou periods, this was not a unified administrative unit but rather a geopolitical stage where numerous Fang states (polities), vassal states, and ethnic groups were complexly intertwined. It transformed from the eastern boundary of the Shang culture to the strategic focal point of the Western Zhou Fengjian system (incorporating states like Qi and Lu), and finally to the primary stage for geopolitical conflict in the Eastern Zhou.

The spatial order of this period was built upon a deep prehistoric cultural legacy. This sequence began with the early Neolithic Houli and Beixin cultures and evolved through the Dawenkou culture. However, for this study’s spatial analysis, the two most critical phases are the immediate predecessors to the Shang: the Longshan (c. 2600–2000 BCE) and Yueshi (c. 1900–1500 BCE) cultures. The Longshan period established the foundational demographic-geographical pattern: massive population aggregation in the fertile plains and the first large-scale development of coastal salt production. This was followed by the Yueshi period, where social complexity declined and political networks fragmented. Thus, the Shang dynasty entered a fractured zone superimposed upon this uneven spatial inheritance.

The Longshan culture period (c. 2600–2000 BCE) represents the prehistoric peak of social complexity and settlement morphology in this region. This period is highlighted by a population explosion, the establishment of a multi-tiered settlement system, and the widespread appearance of large-scale walled sites. Regional centers like Chengziya, often regarded as capitals of “Fang states” (polities), demonstrate that the landscape was already organized into a complex political network. Crucially, the Longshan period established the foundational demographic-geographical pattern: massive population aggregation in the fertile plains (the future Qi and Lu heartlands) and the first large-scale development of coastal salt production (e.g., the Shuangwangcheng site).

This was followed by the Yueshi culture period (c. 1900–1500 BCE). Abrupt climatic shifts toward cold and dry conditions likely led to setbacks in agricultural production and social turmoil. This resulted in a sustained decline in social civilization, with a marked decrease in the number and scale of settlements. The integrated political network of the Longshan era, which had been based on regional-center nodes, ceased to exist. It was replaced by a pattern that was more politically fragmented and spatially dispersed (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of Prehistoric Sites in the Shandong Region.

Therefore, when the Shang dynasty’s power expanded eastward, it was not confronted by an empty landscape, nor by a unified state. It entered a fractured zone composed of numerous smaller, competing Yueshi cultural polities, superimposed upon the high-potential (but temporarily stressed) demographic legacy of the Longshan period.

This prehistoric spatial legacy provided the direct foundation for the Shang and Zhou periods. The subsequent political order was, to a large extent, built upon this uneven spatial inheritance:

Inheritance of Centrality: Many important capitals in the Qi and Lu regions (e.g., Linzi, Qufu) were located near prosperous prehistoric settlement centers, inheriting their demographic and agricultural base.

Inheritance of Resources: The development of coastal areas, particularly for salt, had already begun, setting the stage for the large-scale salt production that would later fuel the Qi state.

Inheritance of Barriers: The plains on both flanks of the Tai-Yi Mountain range had been the most densely populated areas since the Neolithic, reinforcing the mountains themselves as a persistent “void” in political control.

In the late Shang period, this area included the eastern territories ruled by the Shang dynasty and independent Fang states of the Yi peoples. In the early Western Zhou, the Zhou king enfeoffed Lü Shang (founder of Qi) at Yingqiu and Bo Qin (eldest son of the Duke of Zhou) in Lu, formally incorporating this region into the Zhou dynasty’s Fengjian system. During the early Eastern Zhou, the Qi state occupied the majority of modern Shandong, while the Lu state was located in the southwest; the two developed concurrently. In addition, smaller Eastern Yi states like Ju and Lai, as well as enfeoffed states related by marriage such as Ji and Cao, were also scattered throughout the area.

2.2. Temporal Scope

The temporal scope of this study is primarily defined as the Shang, Western Zhou, and Eastern Zhou periods (c. 1600 BCE–221 BCE). This long-duration timeframe completely covers the entire process of the early Central Plains state’s power expanding into the Shandong region: from point-like intervention (Shang), to networked systematic construction (Western Zhou), and finally to territorialized transformation (Eastern Zhou).

Among these, the core timeframe for the Fengjian analysis is the period from the Western Zhou to the Warring States. This core period was selected because: the Western Zhou’s establishment of states through Fengjian marked the Zhou dynasty’s formal extension of the Huaxia ritual order into the Shandong region, bringing the settlement systems of states like Qi and Lu onto a regulated track of ritual governance. Subsequently, during the Eastern Zhou (Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods), phenomena such as the hegemony of the Qi state and the philosophies of Confucius and Mencius were all closely related to the spatial patterns and order of settlements. The end point is the fall of the Qi state to the Qin (221 BCE) at the end of the Warring States period. After this point, the Qin dynasty implemented the Jun-Xian system nationwide, completely reorganizing the traditional spatial order of regional enfeoffed states.

2.3. Data Sources and Processing

This study is grounded in archaeological evidence. The dataset was primarily derived from the authoritative Atlas of Chinese Cultural Relics: Shandong Fascicle [17], Historical Atlas of Shandong Province [16] and data from the Third National Cultural Relics Census. The authors digitized the spatial coordinates sites from these maps. These data were cross-referenced with published archaeological survey reports and excavation briefs to ensure accuracy. Field investigations were also conducted to verify the geographical locations and preservation status of key sites.

The selection of samples adheres to the following principles:

- (1)

- Clear Chronology and Strong Representativeness: The main period or significant phases of a site must fall within the timeframe set by this study. Priority is given to representative sites with clear cultural attribution and those holding a high rank or special function within the regional settlement hierarchy.

- (2)

- Rich and Reliable Archaeological Data: Priority is given to sites that have been thoroughly excavated and studied to ensure that basic information is relatively complete, such as geographical coordinates, area, primary remains (e.g., city walls, moats, architecture, tombs), and cultural attribution. Conversely, sites with scattered or dubious data are treated with caution to avoid compromising the reliability of the conclusions.

- (3)

- Systematic Coverage: The Shandong region is vast, with diverse topography including the southwestern plains, the central mountainous areas, and the hills of the Jiaodong Peninsula. Different geographical environments may foster different settlement models. Therefore, while ensuring a focus on key sites, the sample strives for a geographical distribution that covers the different natural-geographical units (plains, mountains, coastal areas) and political units within the study area. This ensures the samples are continuous and comparable in time and space, thereby constructing a relatively complete regional settlement system.

Based on the principles above, this study will attempt to construct a multi-level, multi-regional settlement sample system. By integrating archaeological site distribution maps with spatial analysis methods, it endeavors to comprehensively depict the features of the settlement spatial order in the Shandong region during the Shang and Zhou periods, aiming to capture the regularities in the social-spatial organization of the time and the deep-seated dynamics that generated them.

2.4. GIS Spatial Analysis Methods, Parameters and Theoretical Framework

The quantitative analysis employs two primary GIS spatial methods: Kernel Density Analysis (KDA) and Voronoi diagrams (Thiessen polygons). To ensure the rigor and replicability of this study, the parameters and theoretical framework for these analyses are detailed below.

- (1)

- Kernel Density Analysis (KDA)

The KDA was performed using the Kernel Density tool within the ArcGIS Pro platform. The analysis employed the standard Quartic (bi-weight) kernel function, which is the software’s default. Crucially, the search radius (bandwidth) was not set to an arbitrary manual value. Instead, we adopted the software’s default calculation based on Silverman’s Rule of Thumb. This method automatically computes an optimal search radius based on the spatial configuration (density and distance) of the input point data for each specific period. This data-driven approach ensures a statistically appropriate level of smoothing to identify settlement clusters and makes the resulting density maps steady and replicable.

- (2)

- Voronoi Diagram (Thiessen Polygons) Analysis: Theoretical Framework and Generator Point Selection

It is essential to clarify this study’s theoretical framework for Voronoi diagrams. They are employed not as a simulation of “actual” political territory, but as a heuristic tool and a null hypothesis.

Model’s Purpose and Assumptions: The Voronoi model operates on a single, simple assumption: a flat, homogenous, and featureless landscape where spatial “control” is determined only by geometric proximity (the nearest neighbor). It intentionally ignores all real-world variables, such as topography (mountains, rivers), resources (salt, mines), or transportation.

The Model’s Value (in Deviation): The value of this model lies not in its accuracy, but in its function as a null hypothesis. By comparing the results of this purely geometric model (e.g., the “ideal” areas in Section 3.2) with historical-textual evidence (like the Li Ji’s ritual standards) and known geographical constraints (like mountains), we can more clearly identify and measure the deviation of reality from this ideal model.

Interpreting the Results: This deviation is the finding. When the model’s “territory” (e.g., the Shang median of 797.2 km2) differs from the ritual standard (e.g., the Earl’s fief of c. 847.16 km2), or when the polygons clearly cut across impassable mountains, it powerfully highlights the shaping influence of the very non-geometric factors (topography, resources, military power) that the model ignores.

Selection of Generator Points: Based on this theoretical framework, the selection of “generator points” is a deliberate theoretical design reflecting this paper’s core argument: the fundamental unit of political-spatial organization evolved dramatically during the Shang and Zhou periods. The choice of generator points is designed to model the basic political node of each era:

- Shang Period: “Fang States” and Cities

Rationale: The political landscape of Shang-period Shandong was a fragmented mixture of numerous local polities (Fang Guo) and enclave strongholds of Shang culture. Fang states were, in themselves, relatively independent political entities. Therefore, using both archaeologically confirmed fang state centers and Shang cultural cities as joint generator points is intended to reconstruct this pluralistic, decentralized, and non-unified political geography.

- Western Zhou Period: States (Major and Minor)

Rationale: The key political innovation of the Western Zhou was the Fengjian (enfeoffment) system. In this system, the State (guo), regardless of size, was the basic political unit recognized and enfeoffed by the Zhou king. The model does not exclude major states (like Qi and Lu); Linzi (Qi) and Qufu (Lu) are clearly included as generator points in Section 3.2. The analysis prioritizes the minor states surrounding Qufu because these smaller polities are dimensionally closer to the Li Ji’s prescribed standards (Earl, 70 Li; Viscount/Baron, 50 Li). They are, therefore, the most sensitive analytical subjects for testing the gap between “ritual ideal” and “geopolitical reality”.

- Eastern Zhou Period (Spring and Autumn/Warring States): Cities

Rationale: This shift constitutes a core finding of the diachronic comparison. The most fundamental political-spatial shift from the Western to the Eastern Zhou was the collapse of the “State” unit and the rise of the “City” unit.

As annexation warfare intensified, minor States were absorbed by major powers. These powers no longer practiced re-enfeoffment but instead established “counties” (Xian), the precursor to the Jun-Xian system, which were administered by bureaucrats from a central City.

Therefore, the shift in generator points from the Western Zhou “State” to the Eastern Zhou “City” is a direct quantitative visualization of the fundamental historical transition from a Fengjian system (organized by states) to a Jun-Xian system (organized by cities). This demonstrates that the basic unit and logic of spatial control had profoundly changed.

3. Results

3.1. Diachronic Analysis of Settlement Patterns

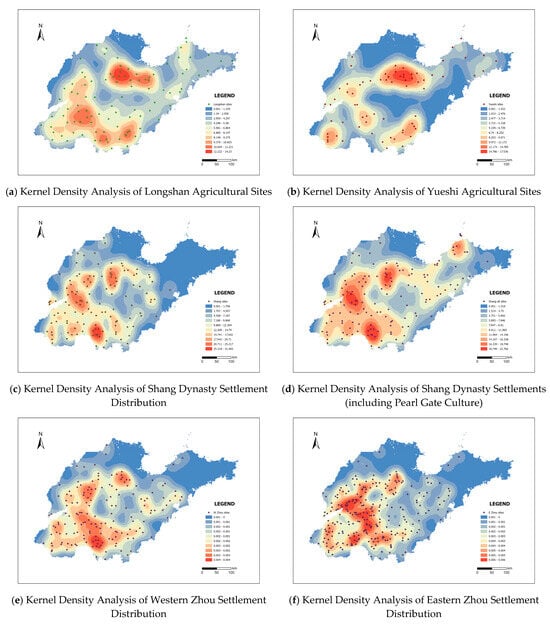

Kernel Density Analysis was conducted on settlement point data from the Longshan, Yueshi, Shang, Western Zhou, and Eastern Zhou periods to reveal the spatiotemporal evolution of settlement centers (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Kernel Density Analysis of Settlements.

In situations where the number of early civilization sites is relatively small, utilizing agricultural sites for kernel density analysis offers strong feasibility and methodological advantages. First, agricultural sites (e.g., paddy field remains, ash pits, storage pits, agricultural tool find-spots) are typically closely related to long-term human habitation and production activities. Their spatial distribution can more directly reflect the actual extent of settlement land use and population-carrying capacity. In contrast, common site types (like isolated tombs or small workshops) often carry a stronger element of chance and functional limitation in settlement distribution studies, making it difficult to comprehensively reveal a region’s social-spatial structure. Second, agricultural sites have a higher frequency of discovery and identifiability in field archaeology, providing a more continuous and larger dataset that serves as a stable foundation for KDA.

A kernel density analysis conducted on agricultural sites from the Longshan culture period shows that their distribution exhibits high density and regional clustering in two main areas: the middle and lower plains of the Zi, Wei, and Mi rivers to the north; and the middle and lower plains of the Si, Yi, and Shu rivers to the south. The settlement clustering reflected by this concentration of Longshan agricultural sites precisely and highly coincides with the later distribution of the two major cultural centers in this region, Qi and Lu. This indicates that the geographical environment had a significant influence on the political patterns and cultural trajectories of the regional society.

A KDA performed on Yueshi culture agricultural sites demonstrates a high degree of continuity in the core areas of settlement distribution compared to the Longshan period, but with an overall decline in the number of settlements. The distribution range in the middle and lower Zi, Wei, and Mi rivers contracted, while the settlement clustering in the middle and lower Si, Yi, and Shu rivers markedly decreased. The settlement distribution shifted from being widespread and dense during its peak to relatively sparse. The social center of gravity transitioned from a state of multiple large, coexisting cities to a structure supported by a few remaining strongholds. The relatively integrated political network of the Longshan era, which had been based on regional-center nodes, ceased to exist. It was replaced by a pattern that was more politically fragmented and spatially dispersed. When the Shang dynasty’s power expanded eastward, it was not confronted by a unified and powerful Longshan-style state alliance, but rather by a fractured zone composed of numerous smaller, competing Yueshi cultural polities. This power vacuum provided favorable conditions for the Shang dynasty’s military conquest and the implantation of a new political order.

The overall settlement distribution pattern in the Shang dynasty Shandong region can be roughly divided into three tiers: high-density core zones, secondary-density zones, and low-density/empty zones. The high-density core zones were the strategic pivots and civilizational centers for the Shang dynasty’s management of Shandong, presenting a dual-core configuration with the Daxinzhuang site (Jinan) and the Qianzhangda site (Tengzhou) standing parallel. These two core zones were not only the areas with the highest concentration of population and settlements but also the most solid cornerstones for the eastward transmission of Shang culture and royal rule, representing the highest level of Shang civilization’s development in this region. Surrounding these cores were expansive secondary-density zones. The settlement density in these areas was lower than in the core zones, and they were primarily distributed in several key bands: one was the Zi-Wei River basin centered on the Subutun site, which was a frontline for the intense collision between Shang culture and the indigenous Eastern Yi culture; a second was the traditional transportation corridor in the middle Si River area; and a third comprised areas that may have been early Shang capitals or important political centers which, despite their core status having potentially shifted, still maintained relatively substantial population and settlement scales due to their deep historical legacy. The low-density and empty zones reveal the boundaries of Shang cultural influence. In most of the Jiaodong Peninsula, the hinterlands of the Tai-Yi Mountains, and the coastal areas of southeastern Shandong, the number and scale of Shang settlements were significantly reduced. Shang cultural power found it difficult to penetrate the complex terrain of the mountains and peninsula, which were also areas of strong resistance from the indigenous Eastern Yi culture, essentially stopping west of the Wei River line in the middle of the peninsula. Particularly noteworthy is the sharp contrast to the sparseness of Shang culture: the indigenous Pearl Gate (Zhenzhumen) culture of the Yi system exhibited a high settlement density in coastal areas such as Changdao (Yantai). This spatial distribution pattern of one-waxes-and-one-waning vividly delineates the complex historical tableau of coexistence, confrontation, and even demarcated governance between the Shang and Yi cultures in the Shandong region.

The overall settlement distribution pattern of the Western Zhou period largely continued the foundation established by the Shang. The multiple regional centers and developed settlement clusters already formed in Shandong by the late Shang were not destroyed in the political transition; rather, they were taken over by the Zhou dynasty and incorporated as key nodes in the new order. For example, the enfeoffment of Lü Shang at Yingqiu utilized the former Shang culture’s key salt-producing area in northern Shandong; the enfeoffment of Bo Qin at Qufu was also a direct takeover of the former lands of the state of Yan. While inheriting the Shang network, the number of settlements in the Western Zhou period increased and began to show a trend of penetration and expansion into the eastern part of the peninsula, the former territory of the Eastern Yi culture.

By the Eastern Zhou period, this process accelerated. The number of settlements continued to climb, and their distribution became increasingly dense. A significant change occurred in the vast plains and hilly areas of southwestern Shandong, stretching from south of the Yellow River to the Wen and Si River basins. The gaps between the various settlement clusters, which had previously exhibited a grouped distribution, were gradually filled by new settlements. Ultimately, these clusters interconnected and merged into a contiguous expanse, forming a new core region of unprecedented scale and more intensive human activity.

3.2. Simulating the Theoretical Spheres of Control for States

This study employs the Voronoi diagram (also known as Thiessen polygons) spatial analysis method to investigate the spheres of influence and spatial patterns of the Fang states and vassal states in the Shandong region during the Shang and Zhou periods. The specific procedure involves using the centers of states, confirmed through archaeological and textual research, as the core generator points. Voronoi diagrams are then constructed on a GIS platform, dividing the entire study area into multiple spatial units, each centered on one of the core points. The boundaries of the Voronoi polygons represent the nearest zone of influence for each state in geospatial terms and can be regarded as the “theoretical territory” or maximum geopolitical sphere of influence of a state under ideal conditions. In this way, the discrete site points, originally scattered on the map, are transformed into a political influence map composed of contiguous, seamlessly covering polygons.

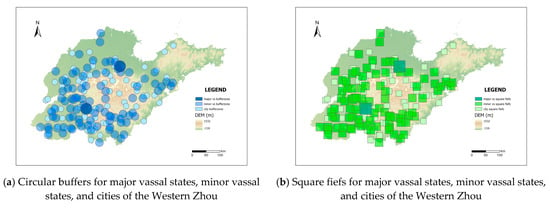

To convert the hierarchical order of enfeoffments into concrete map elements, it is first necessary to discuss the conversion relationship between the Western Zhou and modern systems of weights and measures. Referencing the Shang Yang bronze fang sheng (a standard volume measure) and the Eastern Zhou bronze ruler excavated from the Jincun ancient tombs in Luoyang, academia generally estimates the length of a Qin Chi to be 23.1 cm [18]. According to textual records, the Qin state defined one Bu (pace) as six Chi, and one Li as three hundred Bu. Based on this calculation, the length of one Li is 415.8 m. This figure differs considerably from the modern Li (which equals 500 m).

Secondly, this ratio must be used to convert the ritual norms into approximate areas in square kilometers. It is noted that the descriptions of fief sizes in the Zhou Li (Rites of Zhou) and the Li Ji (Book of Rites) show significant discrepancies. However, the smallest fief size mentioned in the Zhou Li (Barons, 100 Li square) corresponds to the largest fief size in the Li Ji (Dukes/Marquesses, 100 Li square). Regarding this difference, academia generally adopts the Li Ji standard and considers the records in the Zhou Li to be exaggerated or idealized (Table 2).

Table 2.

Fief Area Conversions from Different Classical Texts.

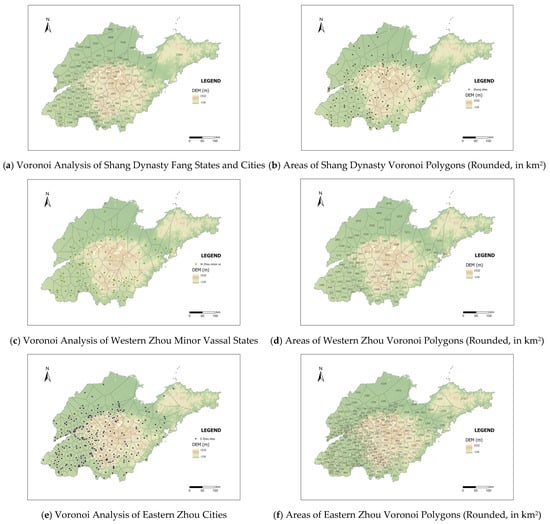

An analysis of the Shang dynasty Fang states (polities) indicates that after using “computational geometry” to calculate the area of a total of 123 polygons, and removing the anomalous data resulting from 20 polygons located at the map’s margins, the mean area of the remaining 103 polygons is 970.2 km2, with a median area of 797.2 km2.

The mean being significantly larger than the median indicates that a few polygons with exceptionally large areas skewed the mean upwards. Regions with areas larger than the mean are concentrated in two natural barrier zones: the Tai-Yi Mountain range and the paleochannel of the Yellow River. This suggests that the natural environment exerted a strong constraining effect on state boundaries. The median area (797.2 km2) might represent the standard or typical scale of a fang state in the Shandong region during the late Shang period. This figure closely approximates the Earl’s fief of 70 Li square (c. 847.16 km2), as stipulated in the “Wang Zhi” (Royal Regulations) chapter of Li Ji (Book of Rites) discussed above. The presence of 123 polygons within a finite study area implies that political power was highly dispersed and the geopolitical environment was exceedingly complex. Consequently, boundary friction, strategic alliances, resource competition, and cultural exchange among these policies would have been exceptionally frequent.

For the GIS spatial analysis of the Western Zhou enfeoffed states, the central city of each state was used as the base point. A circular buffer was created with a radius equal to half the side length of the corresponding fief. A minimum bounding rectangle was then generated from this buffer to produce a square fief conforming to the Li Ji standards. These squares were oriented by default along the north–south and east–west axes, aligned with the coordinate system (Figure 3). Circular buffer radii (rounded): 50 Li square: r = 10.40 km; 70 Li square: r = 14.55 km; 100 Li square: r = 20.79 km. The square-shaped fiefs (Figure 3b) are a deliberate, literal interpretation of the classical text’s description (e.g., in the Li Ji) “Fang Qi Shi Li” (a square with a side length of 70 Li).

Figure 3.

Simulation of Western Zhou Enfeoffed Vassal States.

The results of the square fief simulation demonstrate that the spheres of influence of major vassal state capitals, such as Linzi and Qufu, overlap with those of surrounding minor vassal states and cities. This phenomenon suggests that the fiefs of these minor states may have been, to a large extent, merely nominal. Their actual political and military control had likely already been subsumed under the jurisdiction of the major vassals. Further observation of the mutual overlap among the minor vassal states reveals that in the middle and lower plains of the Wen, Si, Yi, and Shu rivers, which happen to be the area surrounding Qufu, the minor states are densely distributed, and the overlap is pronounced. It can be inferred that in such regions, the actual area of control for any single state was inevitably compressed, falling far short of its corresponding theoretical scale within the enfeoffment system. Consequently, these regions were also prone to more intense resource competition and military conflict. The simulation results indicate that the Western Zhou Fengjian pattern did not cover the entire Shandong region. In areas such as the Tai-Yi Mountains of central Shandong and the Jiaodong hills, large territories remained that were not effectively incorporated into the enfeoffment system. These power vacuums reflect the constraints imposed by the natural geographical environment on enfeoffment activities. They also demonstrate that the Zhou dynasty’s rule in Shandong was primarily concentrated in the river valley plains and along key transportation arteries, whereas its control over the mountainous, hilly, and coastal zones was comparatively weak.

In conducting the Voronoi spatial analysis for the Western Zhou period, the capitals of minor vassal states were prioritized as the core analytical units. This is because, in the archaeological materials, the remains of minor vassal states are often more abundant and more easily identifiable than those of common cities, thus enabling the constructed state model to more closely approximate the actual political-geographical landscape (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Simulation of Settlement Control Ranges.

After calculating the areas of a total of 91 polygons and removing the anomalous data from 18 polygons located at the map’s margins, the mean area of the remaining 73 polygons is 1306.6 km2, and the median area is 1084.4 km2. Compared to the analytical results for the Shang dynasty fang states, the number of minor vassal states decreased by approximately one-quarter, while the total number of minor vassal states and cities increased by about one-third. This indicates that the overall scale of the “states” tended to expand. This demonstrates that after entering the Western Zhou period, the power structure in the Shandong region became more centralized. A portion of the Fang states were annexed or downgraded, and integrated into a larger system of enfeoffed states.

Both the mean and median areas are significantly higher than the “Earl’s fief of 70 Li square” (c. 847.16 km2) stipulated in the Li Ji (Book of Rites). Only slightly less than 30% of the minor vassal states had areas that complied with the ritual specifications, and all of these were located in the middle and lower plains of the Wen, Si, Yi, and Shu river basins. This suggests that the actual area of control for most minor vassal states exceeded the ritual stipulations, indicating a gap between the ritual system and reality. In the resource-rich and agriculturally advanced river valley plains, the scale of the states was closer to the ideal model of the ritual design. This may reflect the Zhou dynasty’s greater ability to implement ritualized spatial control in its core areas, whereas the peripheral regions exhibited greater compromise with geopolitical realities and geographical conditions.

Comparing the Eastern Zhou (Spring and Autumn period) to the Western Zhou period, the number of minor vassal states decreased from 91 to 38, a reduction of 58%. The number of cities increased from 72 to 217, a threefold increase. The sharp decline in minor vassal states is the most direct quantitative evidence of the annexation warfare of the Spring and Autumn Period. The original enfeoffment system progressively disintegrated. The declining small states were absorbed, annexed, or downgraded to subsidiary towns by rising great powers. After annexing these smaller states, the great powers no longer practiced re-enfeoffment.

Using the cities as the generator points for the Voronoi spatial analysis, and after calculating the polygon areas and removing anomalous data from marginal polygons, the mean area of the remaining polygons is 429.3 km2, and the median area is 333.5 km2. The control area of most cities was already far smaller than the smallest, lowest-ranking fief stipulated in the Li Ji (50 Li square, c. 432.2 km2). The units of spatial order became denser, the sphere of control radiated by a single city was smaller, and the granularity of geographical control became more refined.

It must be emphasized that Voronoi spatial analysis is an idealized mathematical model. It cannot fully reflect the actual boundaries created by natural barriers such as mountains and rivers, nor does it account for heterogeneous factors like cultural or military strength. However, as an analytical starting point and a heuristic tool, it is capable of transforming the ambiguous concept of a “state” into a structured spatial model that can be analyzed and tested.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Dynamic Mechanisms of Spatial Integration: Interpreting Model Deviations

The evolution of spatial order in the Shandong region was driven by a complex interplay of power dynamics, the geographical environment, resource allocation, and cultural traditions. This section re-interprets these four factors, using the quantitative findings and model deviations from the GIS analysis as direct evidence.

The primary finding of the GIS modelling is that reality deviates significantly from the idealized geometric “null hypothesis” (the Voronoi model). These deviations are not failures of the analysis; they are the findings themselves. They quantify the immense pressure that these four “real-world” factors exerted upon the abstract logic of spatial geometry.

- The Geographical Environment (The “Stage” and the “Barrier”)

The geographical environment is the foundational stage for human action, providing both corridors and barriers. The GIS analysis provides two clear, quantitative illustrations of its power:

Evidence from KDA (Figure 2): The KDA maps (all periods) consistently show that the vast majority of settlements, and thus, population density and political activity, are concentrated in the alluvial plains (northern, southwestern) and coastal lowlands. The central Tai-Yi Mountain range remains a persistent low-density zone.

Evidence from Voronoi (Figure 4): The Voronoi model, which is blind to geography, demonstrates this barrier through its absurdity. In the mountainous center (see Figure 4b,d,f), the model generates massive, unrealistic polygons (e.g., >3000 km2) simply because there are no generator points (cities) within them. This “Voronoi void” is the quantitative signature of a geographical barrier. It visually proves that the Tai-Yi range was not a space to be controlled but a fundamental constraint on power that fractured the region’s political geography, a reality the simple geometric model cannot comprehend.

- Power Dynamics (The “Driver” and the “Unit”)

State-level political and military actions are the most direct drivers of spatial change. The analysis captures this “power dynamic” not just through qualitative discussion, but through the evolution of the data itself.

Evidence from Generator Point Evolution: The diachronic shift in the generator points (detailed in Section 2.4) is the primary quantitative evidence for this paper. The transition from Fang States (pluralistic, Shang) to States (ritualized, W. Zhou) and finally to Cities (administrative, E. Zhou) is a direct model of the fundamental change in the unit of political-spatial organization.

Evidence from Scale Violation (Figure 4c): In the Western Zhou, the Fengjian system was a power dynamic. The Voronoi model visualizes its internal tensions. While minor states near Qufu conform to a dense, fractured pattern (approximating the ritual ideal), the polygons for major states like Qi (Linzi) and Lu (Qufu) are qualitatively larger. This visible “breakout” from the geometric median is the spatial signature of their exceptional political power, demonstrating their ability to transcend the standard ritual and geopolitical constraints that bound their neighbors.

- Resource Allocation (The “Fuel”)

The control of key resources is the economic foundation for political power. While the Voronoi model ignored resources, the KDA map provides strong, independent evidence for their role in shaping settlement patterns against simple agricultural logic.

Evidence from KDA (Figure 2): The most intense and persistent settlement cluster (KDA hot spot) across all periods (Longshan to E. Zhou) is located in the northern Zi-Wei river basin, close to the Bohai Sea. This area is not necessarily the region’s most fertile (compared to the southwestern plains).

Interpretation (Qi’s Salt): This anomaly is the quantitative, spatial footprint of the region’s vast salt fields. Long before the Qi state, the enduring high density of settlements here suggests a prehistoric concentration of population around this critical resource. The state of Qi did not “invent” this resource; it inherited and monopolized this pre-existing demographic-economic center. This KDA finding provides the geographical and economic context for the political power discussed in traditional texts (e.g., Guan Zhong’s reforms) and validates the qualitative discussion with spatial data.

- Cultural Traditions (The “Network” and the “Fault Line”)

Finally, cultural identity shaped the networks of allegiance and resistance. The GIS models help visualize the fault lines between different cultural groups.

Evidence from KDA (Figure 2d): The KDA map for the Shang dynasty distinctly shows the enclave nature of Shang power. The high-density red zones (e.g., Daxinzhuang, Qianzhangda) are separated by vast, lower-density areas. Crucially, the map also identifies a separate, dense cluster for the indigenous Pearl Gate (Zhenzhumen) culture on the coast, which exists outside the main Shang interaction sphere.

Interpretation: This spatial separation visualizes the “cultural mosaic” described in the textual and archaeological record (e.g., the Daxinzhuang M225 burial, with both Shang and Yi artifacts [20,21]). The KDA map shows that Shang and Yi power were not seamlessly integrated but co-existed in spatially distinct, and sometimes competing, zones of influence.

4.2. Limitations and Prospects

This study relies on archaeological site data, which is subject to preservation bias and uneven survey coverage. While the Voronoi model serves as a useful baseline, it remains a geometric abstraction that does not account for the specific friction of terrain or the agency of individual actors.

Future research should aim to bridge these gaps. Prospectively, this Null Hypothesis framework could be integrated with Cost-Surface Analysis to quantify exactly how much effort was required to maintain the ritualized borders identified here. Additionally, applying this method to other core regions of early Chinese civilization, such as the Yangtze River valley, would allow for a comparative analysis of how different environmental constraints shaped divergent pathways toward political complexity. Such comparative work is essential for building a more global understanding of the spatial logic of early state formation.

5. Conclusions

During the Shang and Zhou periods, the spatial order of the Shandong region underwent a profound and complex transformation. Its overall characteristics can be summarized as an evolution from a natural landscape, which was primarily constrained by the geographical environment and composed of relatively dispersed cultural units, into a politico-cultural regional system dominated by political power, possessing a clear hierarchical structure and increasingly networked characteristics. In this process of transformation, the changes in the number and scale of the states (political units) reflected the interwoven driving effects of the four core dynamics: power dynamics, the geographical environment, resource allocation, and cultural traditions.

The quantifiable framework presented in this study, grounded in a ‘null-hypothesis’ approach, was shown to be central to this interpretation. Rather than attempting to simulate a complex reality, GIS methods (KDA and Voronoi) were employed to establish a replicable, purely geometric baseline. The analytical value was found not in the model’s accuracy, but in its capacity to quantify the deviations from this ideal. These measured deviations, such as the “Voronoi voids” corresponding to the Tai-Yi Mountains or the “scale violations” by major powers like Qi, provided the direct, spatial evidence used to interpret the impact of the four core dynamics (geography, power, resources, and culture). This deviation analysis framework was thus demonstrated to be a crucial quantitative supplement to traditional textual analysis, effectively revealing the spatial logic and dynamic evolution of the ancient political system.

Furthermore, these findings engage directly with broader anthropological theories concerning the political centralization of state societies. While spatial analysis models like Voronoi have inherent limitations in explaining the causal origins of social complexity, the “deviations” identified in this study offer a quantitative lens to view the struggle of early states to overcome geographical friction. The transition from the void-filled landscape of the Shang to the increasingly integrated network of the Eastern Zhou reflects a universal trajectory in social complexity: the progressive ability of a centralizing power to impose an artificial, administrative spatial order upon a heterogeneous natural landscape. This case study suggests that the Chinese path to empire was not merely an institutional evolution but a tangible spatial conquest, where ritual norms served as the initial blueprint for overcoming geographical fragmentation.

The Jun-Xian (commandery-county) system implemented following the Qin-Han unification serves as a crucial historical reference for this study. As the cornerstone for achieving centralized authoritarian rule, this system acted as the core tool for the “spatial formatting” of the empire’s vast territory, operating on a logic of standardization and vertical management. In Shandong, the once-prominent State of Qi and Lu were completely eliminated as political entities. Their former homelands were fragmented and assigned new administrative names (such as Linzi Commandery or Jibei Commandery) devoid of their old state affiliations, marking the definitive administrative end of the Fengjian order.

This transformation of the Shandong region’s spatial order by the Qin and Han empires was a process of both inheritance and fundamental reinvention. On the one hand, the new empire inherited and maximized the material and demographic foundations left by the previous eras, including the city systems, the agricultural population, and the transportation networks, which effectively reduced the empire’s costs of governance. On the other hand, it decisively dismantled the political and social structure of the Zhou periods, which had been centered on the Fengjian system. The new order, based on bureaucracy and law, enabled the central government to firmly control local resources and prevent the entrenchment of local powers, thus providing the long-term answer to the spatial-political questions first posed in the Shang and Zhou.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.W. and Y.Z.; methodology, X.W. and Y.Z.; software, X.W.; validation, X.W. and Y.Z.; formal analysis, X.W.; investigation, X.W.; data curation, X.W.; writing—original draft preparation, X.W.; writing—review and editing, X.W.; visualization, X.W.; supervision, Y.Z.; project administration, Y.Z.; funding acquisition, Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Key Laboratory of Information Technology for Architectural Culture Inheritance, Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the People’s Republic of China.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available at this time as they form part of a larger, ongoing research project that includes unpublished work.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Google Gemini 2.5 in order to improve the language only. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, F. Landscape and Power in Early China: The Crisis and Fall of the Western Zhou 1045–771 BC; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Shaughnessy, E.L. The Xia Shang Zhou Duandai Gongcheng Baogao and Its Chronology of the Western Zhou Dynasty. Early China 2023, 46, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.; Wu, X.; Wang, J.; Pan, Y.; Lin, Y.; He, J.; Cui, J. A modeling radiocarbon dating for the founding of Yan Vassal State in Western Zhou Dynasty. Radiocarbon 2025, 67, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Wang, F.; Childs-Johnson, E. The Spread of Erlitou Yazhang to South China and the Origin and Dispersal of Early Political States. In The Oxford Handbook of Early China; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 202–226. [Google Scholar]

- Su, B.; Yin, W. On the Question of Regional Systems and Cultural Types in Archaeology. Cult. Relics 1981, 10–17. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yan, W. The Unity and Diversity of Prehistoric Chinese Culture. Cult. Relics 1987, 38–50. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Zou, C.; Mao, L.; Jia, X.; Mo, D. The spatial and temporal distribution of archaeological settlement sites in Shandong Province from the Paleolithic to Shang and Zhou periods and its relationship with hydrology and geomorphology. Quat. Sci. 2021, 41, 1394–1407. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Cui, Y. The spatiotemporal pattern of cultural evolution response to agricultural development and climate change from Yangshao culture to Bronze Age in the Yellow River basin and surrounding regions, north China. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 657179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Chen, P.; Lu, P.; Yang, H.; Yang, S.; Zhang, L.; Luo, R. Evolution of Influence Ranges of Neolithic-Bronze Age Cities in the Songshan Mountain Region of Central China Based on GIS Spatial Analysis. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, M.; Li, B.; Li, Z. Research on the Spatial–Temporal Distribution and Morphological Characteristics of Ancient Settlements in the Luzhong Region of China. Land 2022, 11, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, H. Agriculture, the environment, and social complexity from the Early to Late Yangshao Periods (5000–3000 BC): Insights from macro-botanical remains in north-central China. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 662391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, D.A. The basics of least cost analysis for archaeological applications. Adv. Archaeol. Pract. 2015, 3, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidel, W. The shape of the Roman world: Modelling imperial connectivity. J. Rom. Archaeol. 2014, 27, 7–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanowska, I.; Wren, C.D.; Crabtree, S.A. Agent-Based Modeling For Archaeology: Simulating the Complexity of Societies; SFI Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chliaoutakis, A.; Chalkiadakis, G. An agent-based model for simulating inter-settlement trade in past societies. J. Artif. Soc. Soc. Simul. 2020, 23, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compilation Committee of the Historical Atlas of Shandong Province. Historical Atlas of Shandong Province; Atlas Press of Shandong Province: Jinan, China, 2016. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- National Cultural Heritage Administration. Atlas of Chinese Cultural Relics; Cultural Relics Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2008. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, G. A Study of Chinese Weights and Measures Through the Dynasties; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1992. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, Y. Collat. The Thirteen Classics with Commentaries and Notes; Zhonghua Book Company: Beijing, China, 1980. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Fang, Z.; Guo, J.; Li, M.; Fang, H.; Lang, J. Brief Report on the Excavation of Shang Tombs No.225 and No.256 at the Daxinzhuang Site in Jinan City. Archaeology 2022, 2, 54–69+2. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. The Bronzes with Character of Suo Unearthed at Daxinzhuang Site and The Geographical Location of Suo in Oracle Inscription. Palace Mus. J. 2023, 258, 17–24+132. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.