Urban Green Space per Capita for Sustainable and Equitable Urban Planning: A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How has UGSPC been applied in developed and developing countries?

- What trends emerge in the included studies concerning the integration of UGSPC into research, urban planning and sustainability analyses?

- To what extent has UGSPC been utilized as a standalone indicator in the analysis and assessment of urban green spaces?

2. Materials and Methods

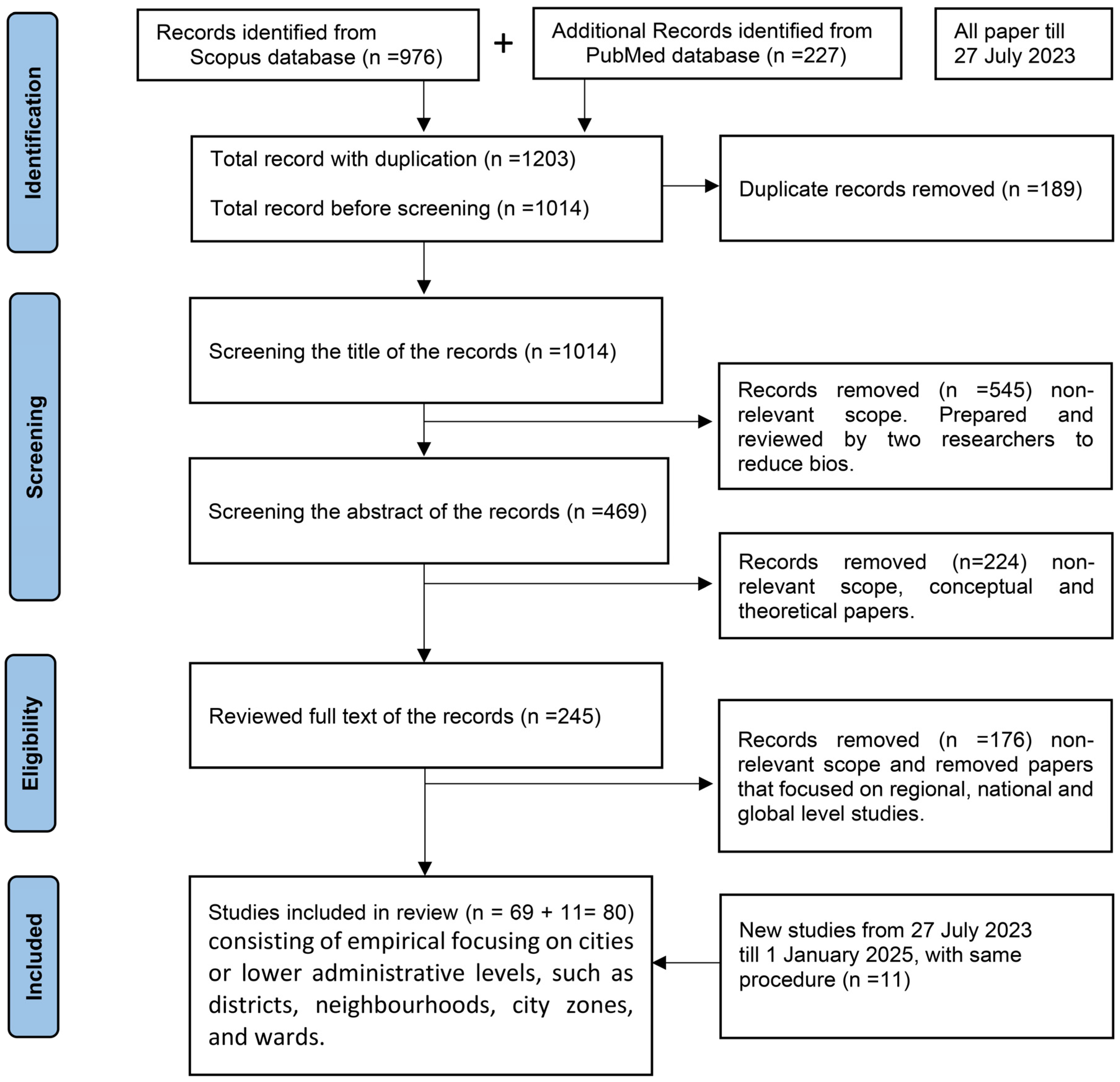

2.1. Data Acquisition

2.2. Screening, Eligibility and Inclusion

3. Results

3.1. Urban Green Space per Capita Application

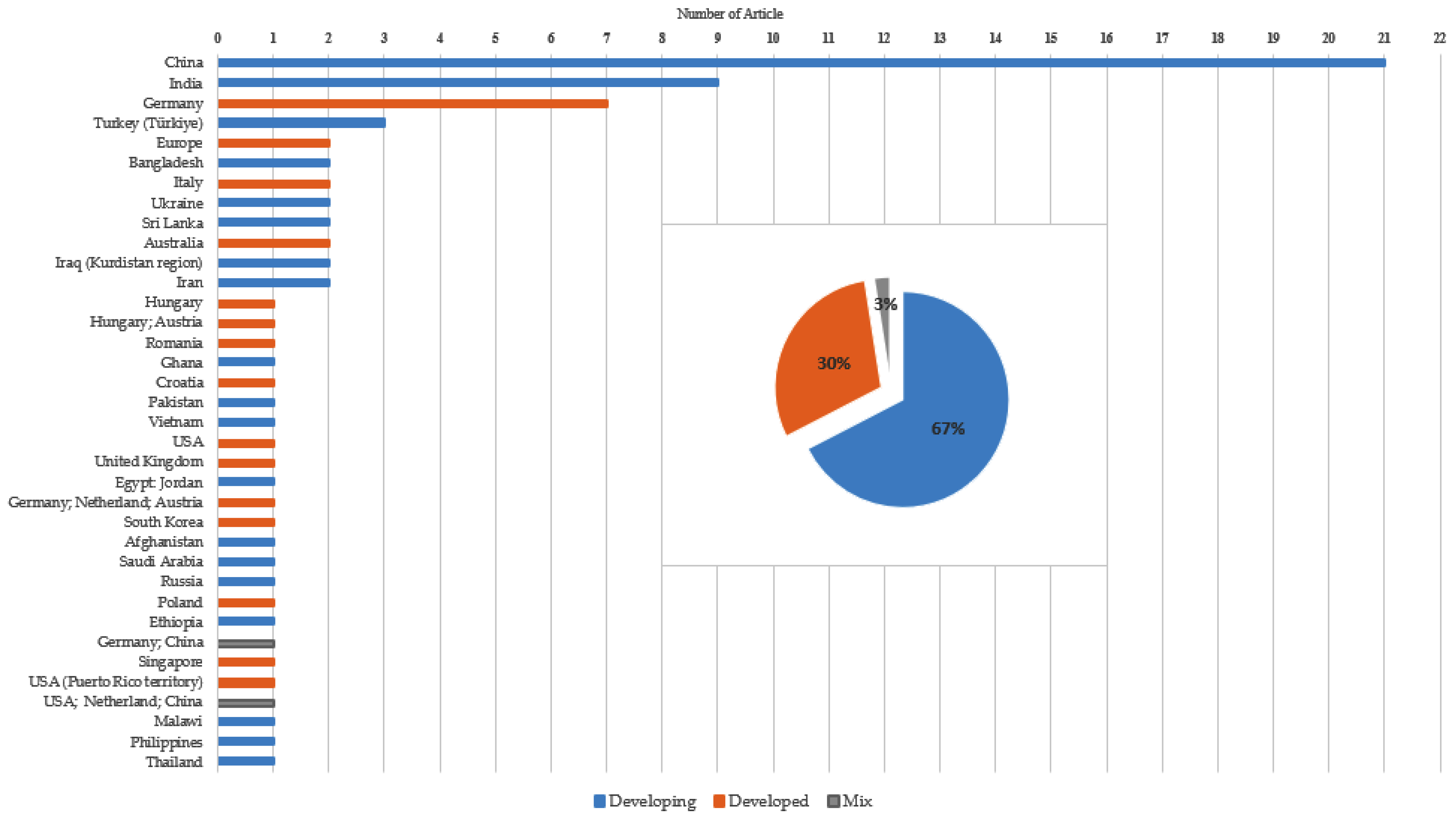

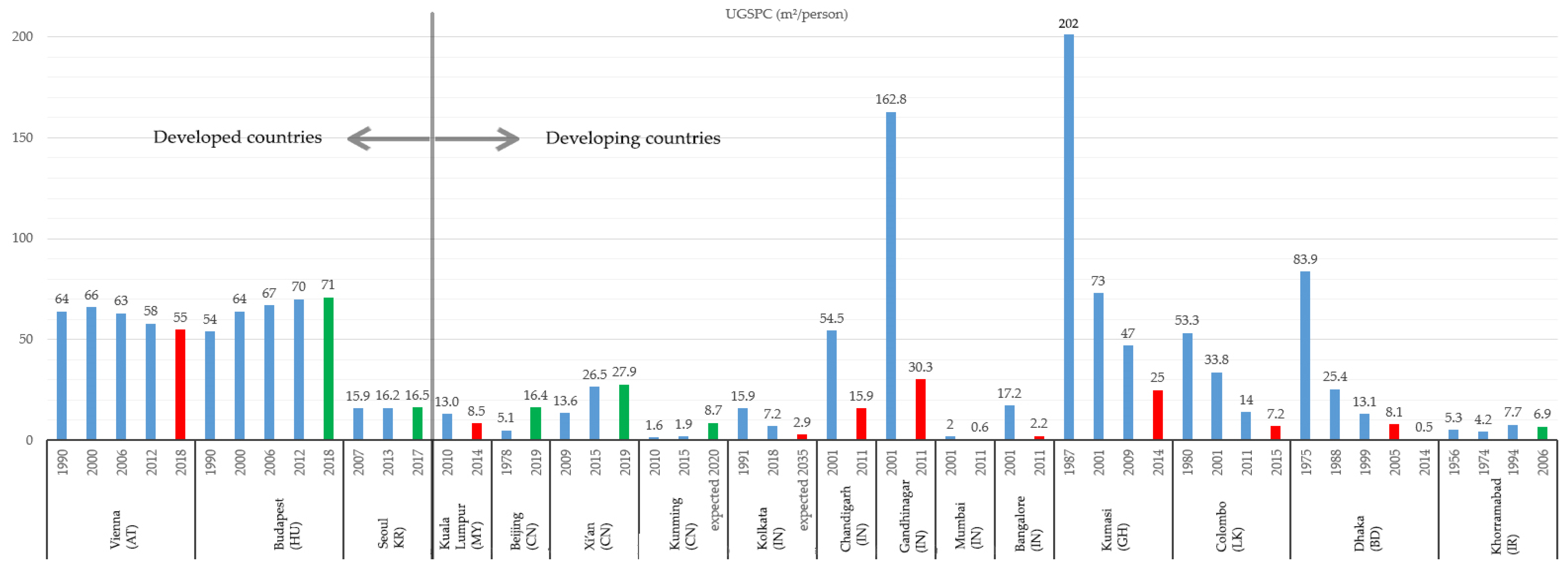

3.1.1. A Global Analysis of Urban Green Space per Capita Through Case Studies

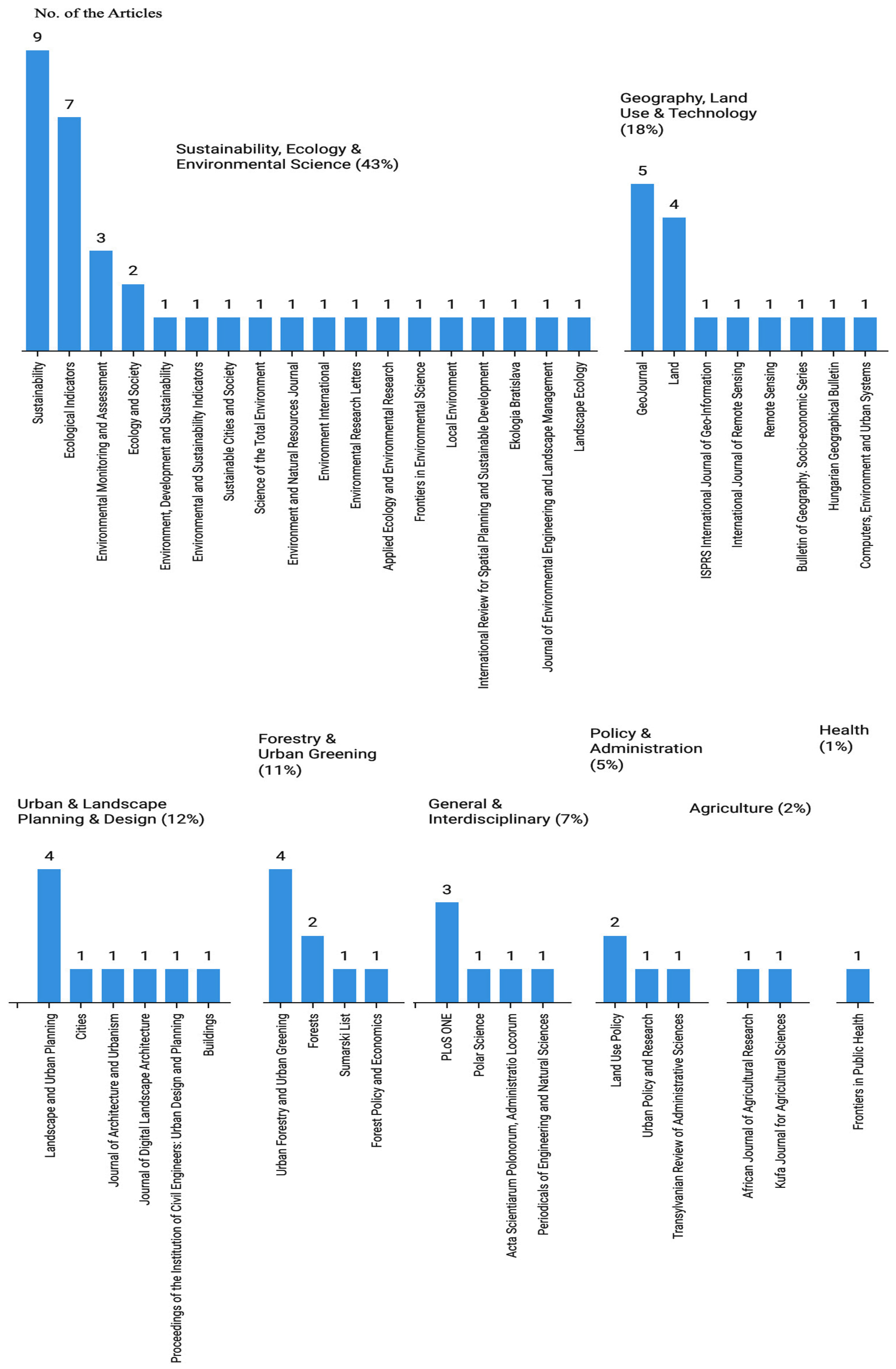

3.1.2. Publication and Thematic Patterns Across Journals

3.1.3. UGSPC Definition and Formula

3.1.4. Terms Used in Relation to Urban Green Space

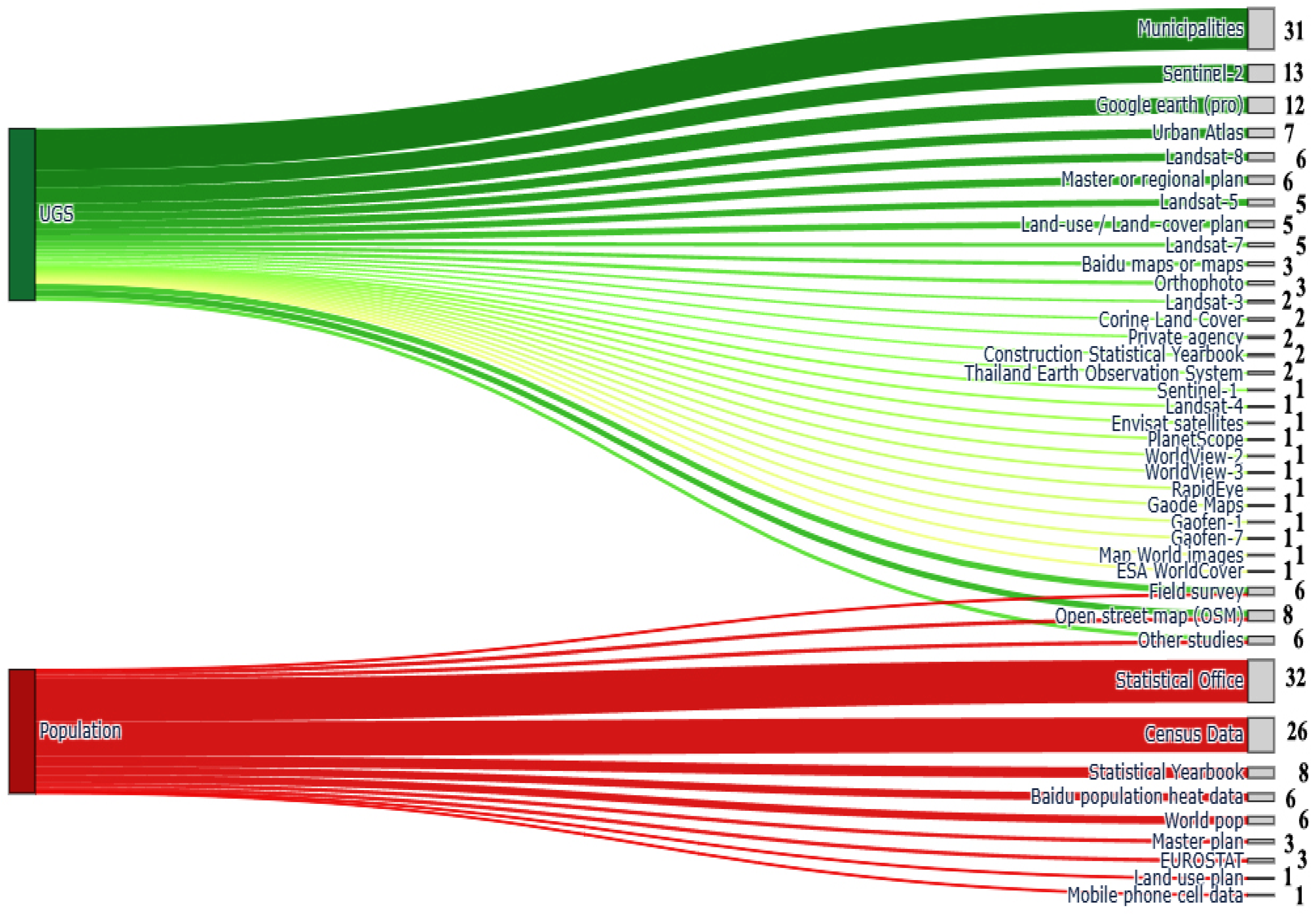

3.1.5. UGS and Population Sources Utilized in the Studies

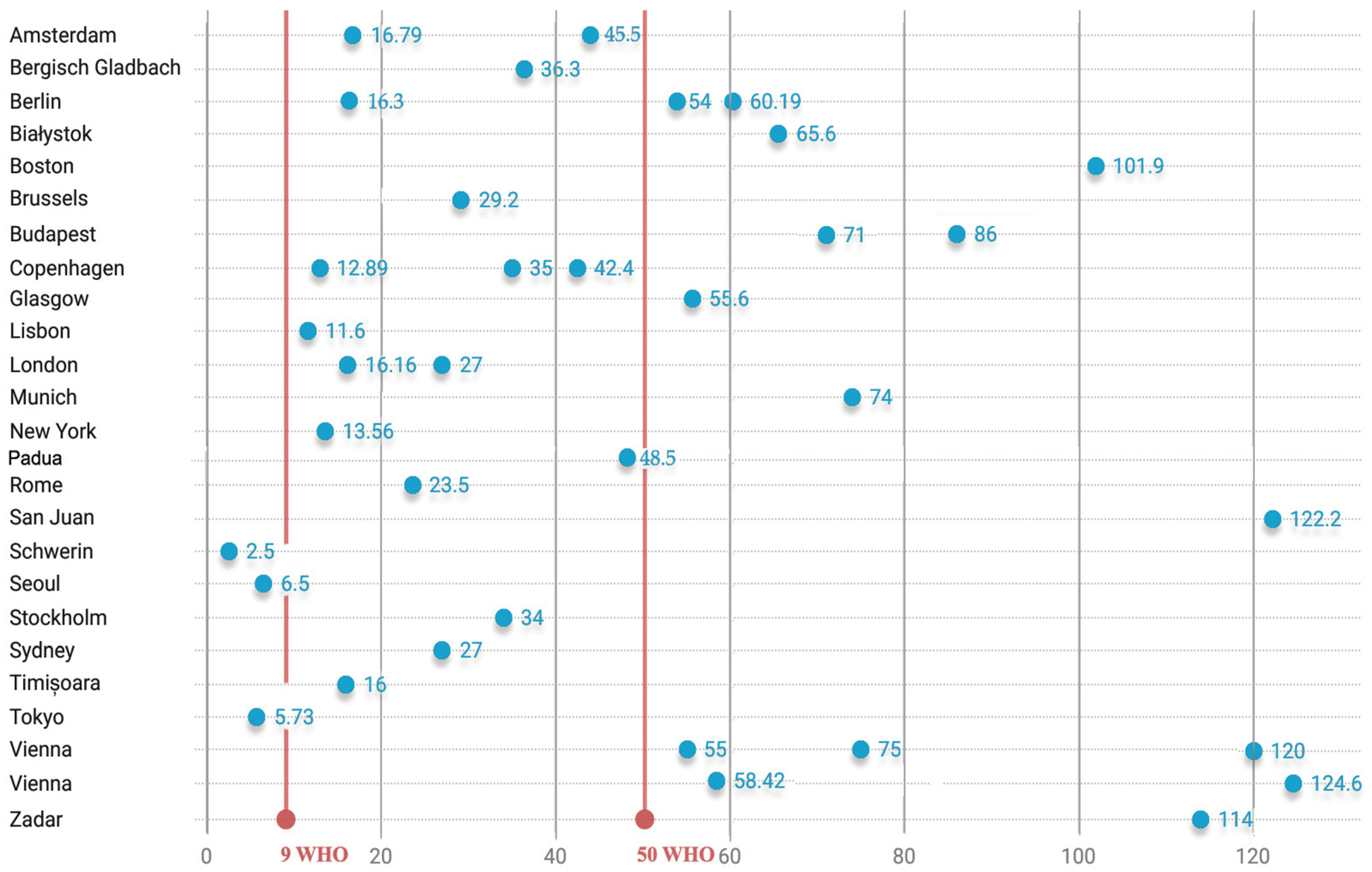

3.1.6. UGSPC Value Across Developed Countries

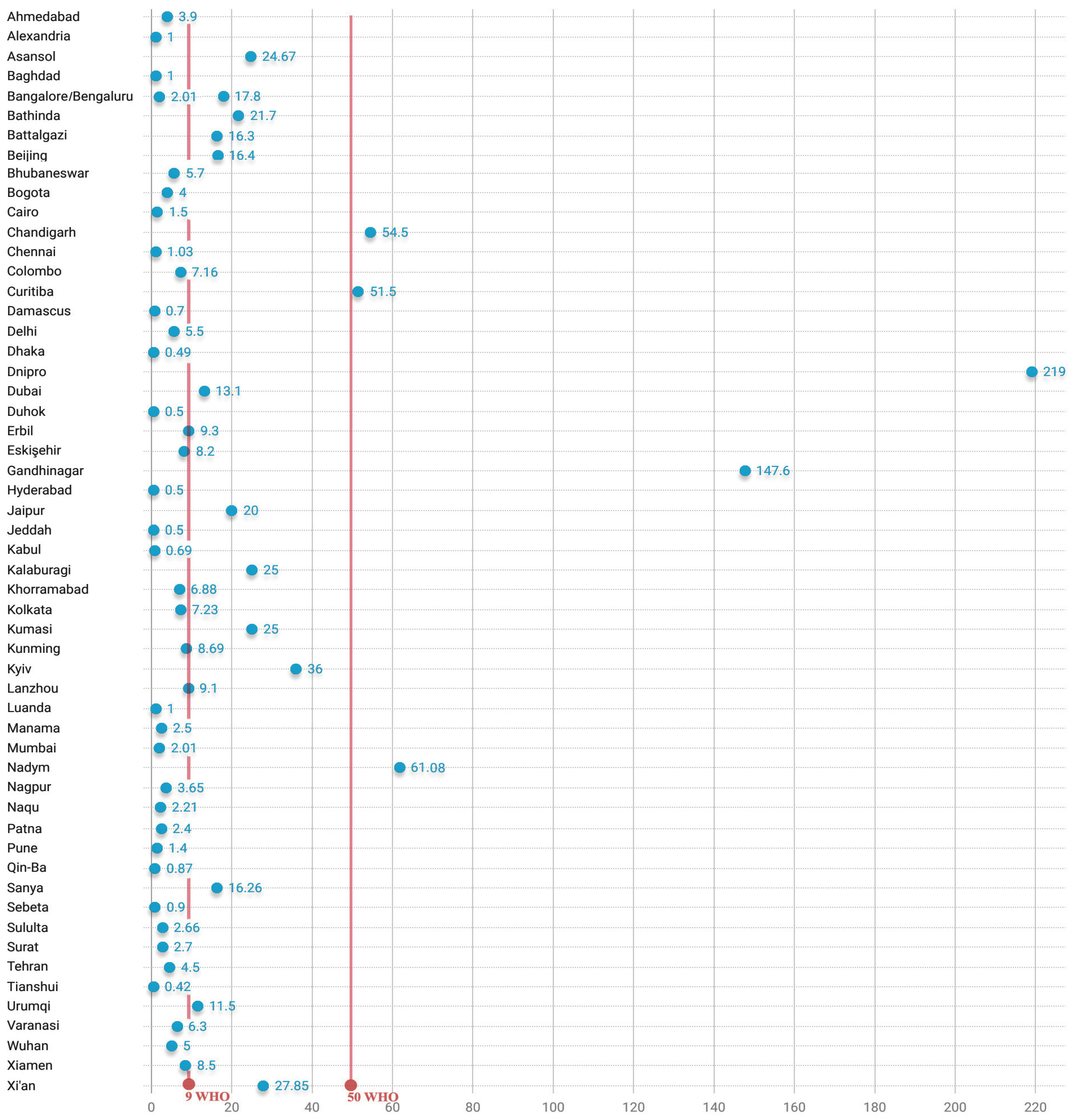

3.1.7. UGSPC Value Across Developing Countries

3.2. The Trend in UGSPC

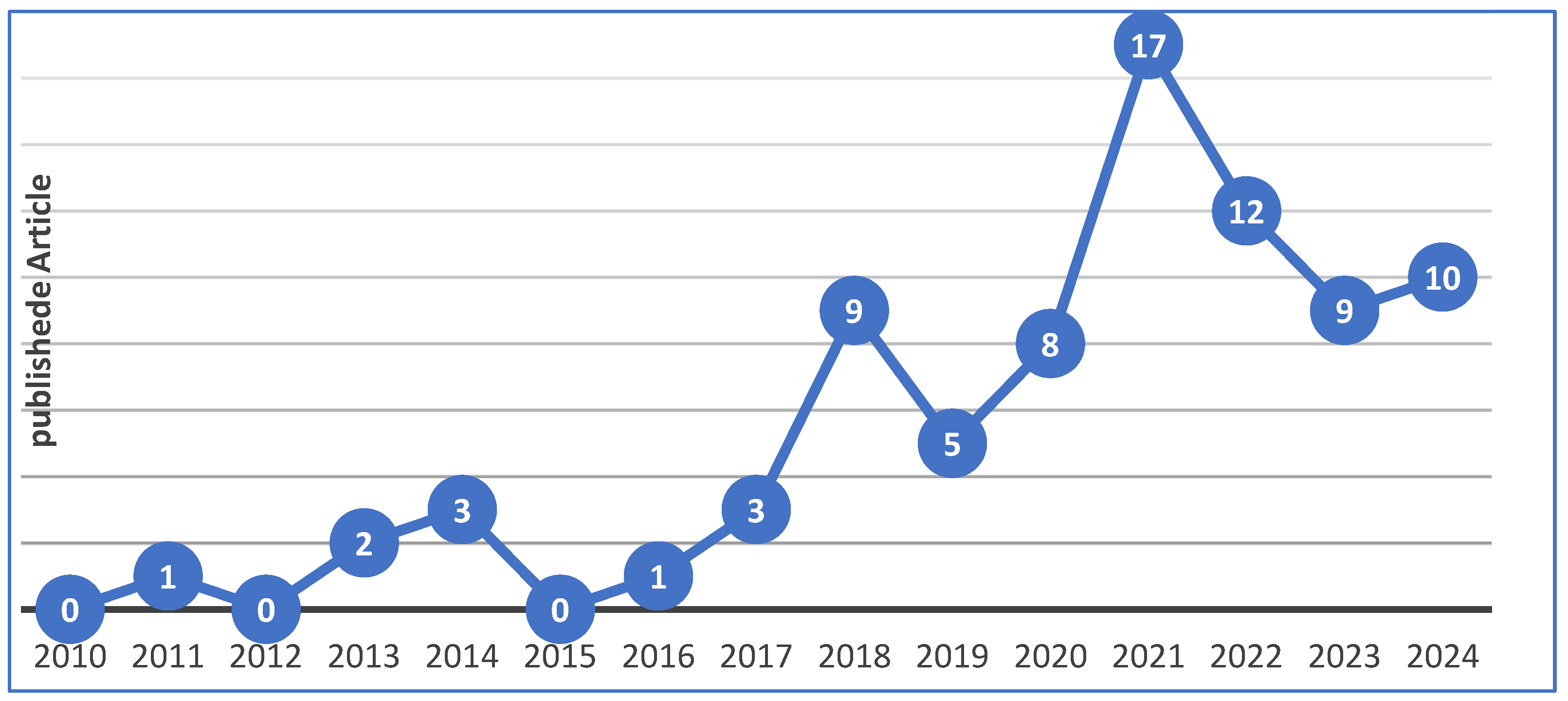

3.2.1. Publication Trend in Urban Green Space per Capita

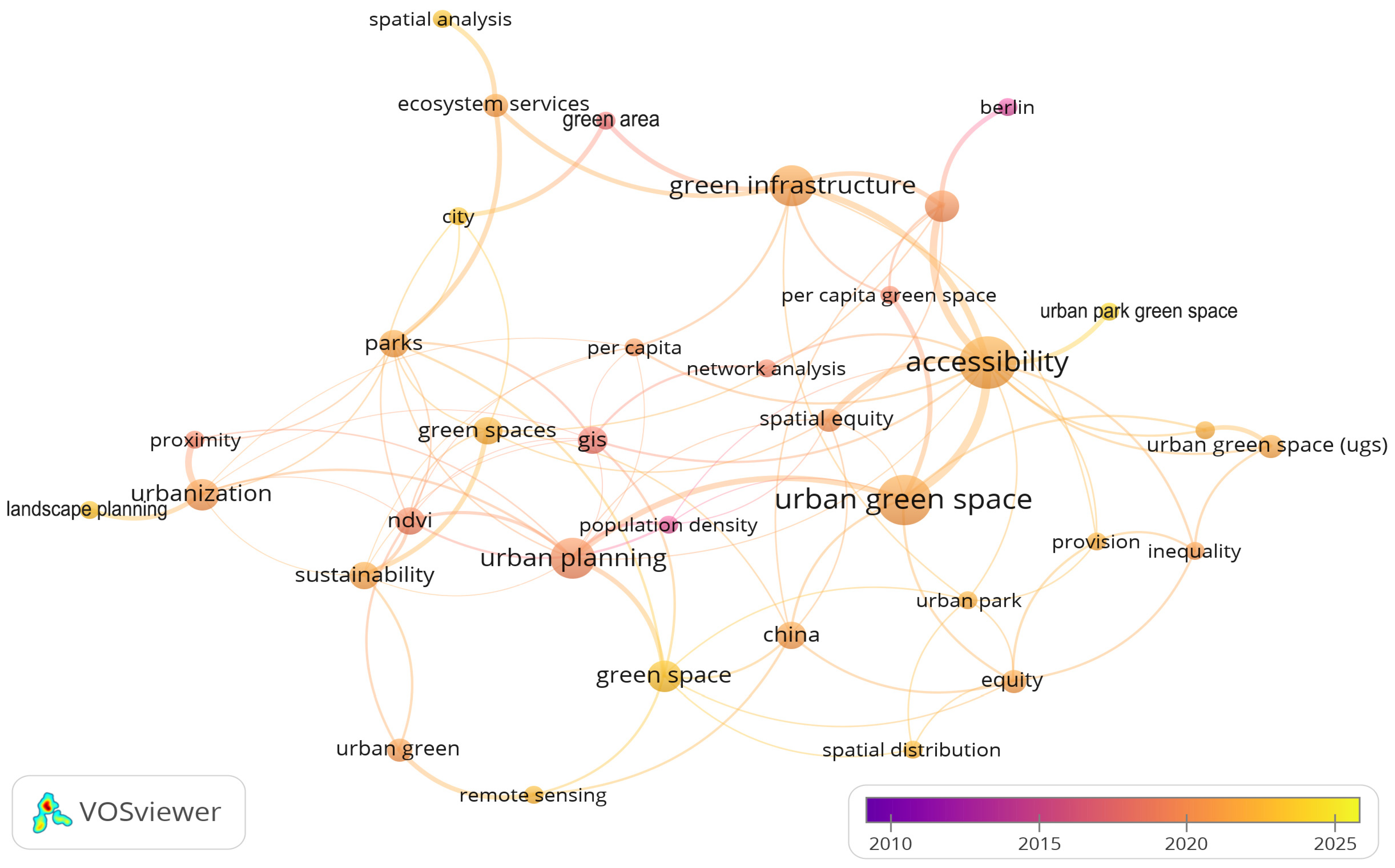

3.2.2. The Authors’ Keywords Co-Occurrence

3.2.3. Trend in the Value of UGSPC in the Studies

3.3. The Usability of UGSPC

3.3.1. Global Standards for Measuring UGSPC

3.3.2. Dimensions of Urban Green Space Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eldridge, D.J.; Cui, H.; Ding, J.; Berdugo, M.; Sáez-Sandino, T.; Duran, J.; Gaitan, J.; Blanco-Pastor, J.L.; Rodríguez, A.; Plaza, C. Urban greenspaces and nearby natural areas support similar levels of soil ecosystem services. npj Urban Sustain. 2024, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenman, T.S. Frederick Law Olmsted, green infrastructure, and the evolving city. J. Plan. Hist. 2013, 12, 287–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, J.A. Three Men in the Wilderness: Ideas and Concepts of Nature During the Progressive Era with Theodore Roosevelt, Gifford Pinchot and John Muir. Master’s Thesis, University of Northern Iowa, Cedar Falls, IA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.; Li, S. Design with Nature: Ian McHarg’s ecological wisdom as actionable and practical knowledge. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 155, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, E. Public and private: Rereading jane Jacobs. Landsc. J. 1994, 13, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, C. Geographies for the present: Patrick Geddes, urban planning, the human sciences and the question of culture1. Indep. Acad. 2003, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, C.C.; Francis, C. People Places: Design Guidlines for Urban Open Space; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Culpin, E.G.; Ward, S. The Garden City Movement Up-to-Date; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.L.; Eisenman, T.S. Building connections to the minute man national historic park: Greenway planning and cultural landscape design. In Proceedings of the Fábos Conference on Landscape and Greenway Planning, Amherst, MA, USA, 28–30 March 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski, Z.J.; McPhearson, T.; Matsler, A.M.; Groffman, P.; Pickett, S.T. What is green infrastructure? A study of definitions in US city planning. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2022, 20, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Sáez, E.; Lerma-Arce, V.; Coll-Aliaga, E.; Oliver-Villanueva, J.-V. Contribution of green urban areas to the achievement of SDGs. Case study in Valencia (Spain). Ecol. Indic. 2021, 131, 108246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyder, M.B.; Haque, T.Z. Understanding the linkages and importance of urban greenspaces for achieving sustainable development goals 2030. J. Sustain. Dev 2022, 15, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, D.M.; Singh, H.; Yahya, W. A brief discussion on human/nature relationship. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2015, 5, 90–93. [Google Scholar]

- Sibthorpe, R.L.; Brymer, E. Disconnected from nature: The lived experience of those disconnected from the natural world. In Innovations in a Changing World; Australia by Australian College of Applied Psychology: Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2020; pp. 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Projected to Reach 9.8 Billion in 2050, and 11.2 Billion in 2100. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/desa/world-population-projected-reach-98-billion-2050-and-112-billion-2100 (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division. World Urbanization Prospects 2018: Highlights; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, P.F. The golden fleece: The search for standards. Leis. Stud. 1985, 4, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiu, D.L.; Iojă, C.I.; Pătroescu, M.; Breuste, J.; Artmann, M.; Niță, M.R.; Grădinaru, S.R.; Hossu, C.A.; Onose, D.A. Is urban green space per capita a valuable target to achieve cities’ sustainability goals? Romania as a case study. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 70, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Cirella, G.T. Modern compact cities: How much greenery do we need? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; He, X.; Wang, C.; Fang, Y. Estimation of Carbon Density in Different Urban Green Spaces: Taking the Beijing Main District as an Example. Land 2025, 14, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukhnovskyi, V.; Zibtseva, O. Normalization of green space as a component of ecological stability of a town. J. For. Sci. 2019, 65, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.-Y.; Hawken, S.; Sepasgozar, S.; Lin, Z.-H. Beyond the backyard: GIS analysis of public green space accessibility in Australian metropolitan areas. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziari, K.; Zebardast, K. Spatial distribution and equity of urban green space provision in Tehran Metropolis using hybrid Factor Analysis and Analytic Network Process (F′ ANP) model. Geomatica 2024, 76, 100022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Y.N.; Zhen, S.; Sharbazhery, A.O.; Du, C.; Jombach, S. Evaluating Urban Green Space Accessibility and Per Capita Distribution in Erbil and Sulaymaniyah, Kurdistan Region of Iraq. In Proceedings of the Fábos Conference on Landscape and Greenway Planning, Amherst, MA, USA, 11–13 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ledraa, T.; Aldegheishem, A. What Matters Most for Neighborhood Greenspace Usability and Satisfaction in Riyadh: Size or Distance to Home? Sustainability 2022, 14, 6216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keleg, M.M.; Butina Watson, G.; Salheen, M.A. A critical review for Cairo’s green open spaces dynamics as a prospect to act as placemaking anchors. Urban Des. Int. 2022, 27, 232–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassew, A.; Fikresilassie, A. An assessment of the availability, accessibility, and attractiveness of urban green space and parks in three African cities. Afr. J. Land Policy Geospat. Sci. 2024, 7, 53–70. [Google Scholar]

- Yaysis. Planning Approach: Spatial Analysis. 2022. Available online: https://yaysis.istanbul/en/planning-approach/spatial-analysis (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Hassan, Y.N.; Ali, Z.F.; Üsztöke, L.; Jombach, S. A Comparative Assessment of UGS Changes and Accessibility Using Per Capita Metrics: A Case Study of Budapest and Vienna. J. Digit. Landsc. Archit. 2024, 723–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nero, B.F. Urban green space dynamics and socio-environmental inequity: Multi-resolution and spatiotemporal data analysis of Kumasi, Ghana. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2017, 38, 6993–7020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryanti, M.; Khadijah, H.; Uzair, A.M.; Ghazali, M. The urban green space provision using the standards approach: Issues and challenges of its implementation in Malaysia. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2017, 210, 369–379. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala-Azcarraga, C.; Diaz, D.; Fernandez, T.; Cordova-Tapia, F.; Zambrano, L. Uneven distribution of urban green spaces in relation to marginalization in Mexico City. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Haase, D. Green justice or just green? Provision of urban green spaces in Berlin, Germany. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 122, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haaland, C.; van Den Bosch, C.K. Challenges and strategies for urban green-space planning in cities undergoing densification: A review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 760–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaschke, P.; Pedersen Zari, M.; Chapman, R.; Randal, E.; Perry, M.; Howden-Chapman, P.; Gyde, E. Multiple roles of green space in the resilience, sustainability and equity of Aotearoa New Zealand’s cities. Land 2024, 13, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endalew Terefe, A.; Hou, Y. Determinants influencing the accessibility and use of urban green spaces: A review of empirical evidence. City Environ. Interact. 2024, 24, 100159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, Z.; Nakaya, T.; Liu, K.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, J. The effects of neighbourhood green spaces on mental health of disadvantaged groups: A systematic review. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, W.; Bojke, L.; Coventry, P.A.; Murphy, P.J.; Fulbright, H.; White, P.C. A Systematic Review of the Impact of Changes to Urban Green Spaces on Health and Education Outcomes, and a Critique of Their Applicability to Inform Economic Evaluation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Lu, Z.; Fan, X.; Zhai, W.; Zhang, L.; Xu, D.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Ye, X.; Qin, H. Urban heatwave, green spaces, and mental health: A review based on environmental health risk assessment framework. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 948, 174816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, N.R.; Pineda-Pinto, M.; Gulsrud, N.M.; Cooper, C.; O’Donnell, M.; Collier, M. Exploring the restorative capacity of urban green spaces and their biodiversity through an adapted One Health approach: A scoping review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 100, 128489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihle, T.; Jahr, E.; Martens, D.; Muehlan, H.; Schmidt, S. Health effects of participation in creating urban green spaces—A systematic review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilcins, D.; Sly, P.D.; Scarth, P.; Mavoa, S. Green space in health research: An overview of common indicators of greenness. Rev. Environ. Health 2024, 39, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fan, C.; Xue, D. A review of the effects of urban and green space forms on the carbon budget using a landscape sustainability framework. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Brown, C.D.; Pearson, A.L. A systematic review of audit tools for evaluating the quality of green spaces in mental health research. Health Place 2024, 86, 103185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.K.; Singh, P.; Karmakar, M.; Leta, J.; Mayr, P. The journal coverage of Web of Science, Scopus and Dimensions: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics 2021, 126, 5113–5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Van Leeuwen, E.; Tsendbazar, N.-E.; Jing, C.; Herold, M. Urban green inequality and its mismatches with human demand across neighborhoods in New York, Amsterdam, and Beijing. Landsc. Ecol. 2024, 39, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambazo, O.; Nazombe, K. The spatial heterogeneity of urban green space distribution and configuration in Lilongwe City, Malawi. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Liu, D.; Niu, J.; He, J.; Xu, F. Spatial Heterogeneity Analysis of the Multidimensional Characteristics of Urban Green Spaces in China—A Study Based on 285 Prefecture-Level Cities. Land 2024, 13, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olfato-Parojinog, A.; Dagamac, N.H.A.; Limbo-Dizon, J.E. Assessment of urban green spaces per capita in a megacity of the Philippines: Implications for sustainable cities and urban health management. GeoJournal 2024, 89, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattanakiat, S.; Vongvassana, S.; Phutthai, T.; Nakmuenwai, P.; Chiyanon, T.; Bhuket, V.R.N.; Sattraburut, T.; Chinsawadphan, P.; Khincharung, K. Spatial Green Space Assessment in Suburbia: Implications for Urban Development. Environ. Nat. Resour. J. 2024, 22, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchavyi, Y.; Lovynska, V.; Samarska, A. A GIS assessment of the green space percentage in a big industrial city (Dnipro, Ukraine). Ekológia 2023, 42, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, B.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, J.; Yang, L. Calculating optimal scale of urban green space in Xi’an, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 147, 110003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, A.A.A.; Jassim, M.A. Optimization of the urban green area in Erbil territory for sustainable development. Period. Eng. Nat. Sci. 2023, 11, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, M.; Chakraborty, M. Distribution of green spaces across socio-economic groups: A study of Bhubaneswar, India. J. Archit. Urban. 2023, 47, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouya, S.; Aghlmand, M. Evaluation of urban green space per capita with new remote sensing and geographic information system techniques and the importance of urban green space during the COVID-19 pandemic. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, G.; Roy, A.; Mandal, M.H.; Ghosh, S.; Basak, A.; Singh, M.; Mukherjee, N. An assessment on the changing status of urban green space in Asansol city, West Bengal. GeoJournal 2022, 87, 1299–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasri Roodsari, E.; Hoseini, P. An assessment of the correlation between urban green space supply and socio-economic disparities of Tehran districts—Iran. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 12867–12882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, J.; Sitaula, C.; Aryal, S. NDVI threshold-based urban green space mapping from sentinel-2A at the Local Governmental Area (LGA) level of victoria, Australia. Land 2022, 11, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ge, Y.; Yang, G.; Wu, Z.; Du, Y.; Mao, F.; Liu, S.; Xu, R.; Qu, Z.; Xu, B. Inequalities of urban green space area and ecosystem services along urban center-edge gradients. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 217, 104266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolcsár, R.A.; Csete, Á.K.; Kovács-Győri, A.; Szilassi, P. Age-group-based evaluation of residents’ urban green space provision: Szeged, Hungary. A case study. Hung. Geogr. Bull. 2022, 71, 249–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Ren, Z.; Fu, Y.; Hu, N.; Guo, Y.; Jia, G.; He, X. Decrease in the residents’ accessibility of summer cooling services due to green space loss in Chinese cities. Environ. Int. 2022, 158, 107002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, C.; Libetta, A.; Conticelli, E.; Tondelli, S. Accessibility to and availability of urban green spaces (UGS) to support health and wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic—The case of Bologna. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathey, J.; Hennersdorf, J.; Lehmann, I.; Wende, W. Qualifying the urban structure type approach for urban green space analysis–A case study of Dresden, Germany. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 125, 107519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ma, X.; Hu, Z.; Li, S. Investigation of urban green space equity at the city level and relevant strategies for improving the provisioning in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Kim, S.K. Exploring the equality of accessing urban green spaces: A comparative study of 341 Chinese cities. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 121, 107080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zeng, Y.; Cheng, B.; Li, H. Designating National Forest Cities in China: Does the policy improve the urban living environment? For. Policy Econ. 2021, 125, 102400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinda, S.; Chatterjee, N.D.; Ghosh, S. An integrated simulation approach to the assessment of urban growth pattern and loss in urban green space in Kolkata, India: A GIS-based analysis. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 121, 107178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Kim, S.K. Does socioeconomic development lead to more equal distribution of green space? Evidence from Chinese cities. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 757, 143780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Halik, Ü.; Abliz, A.; Mamat, Z.; Welp, M. Urban green space accessibility and distribution equity in an arid oasis city: Urumqi, China. Forests 2020, 11, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Wu, Y.; Wang, L. Characterizing horizontal and vertical perspectives of spatial equity for various urban green spaces: A case study of Wuhan, China. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhar, S.; Aryal, J. Role of geospatial technology in understanding urban green space of Kalaburagi city for sustainable planning. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 46, 126450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahoti, S.; Lahoti, A.; Saito, O. Benchmark assessment of recreational public Urban Green space provisions: A case of typical urbanizing Indian City, Nagpur. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 44, 126424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.K. Urban green space availability in Bathinda City, India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2018, 190, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šiljeg, S.; Marić, I.; Nikolić, G.; Šiljeg, A. Accessibility analysis of urban green spaces in the settlement of Zadar in Croatia. Šumarski List 2018, 142, 487–496. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, J.; Shakeryari, M.; Nazari Nejad, A.; Mastalizadeh, H.; Maleki, M.; Wang, J.; Rustum, R.; Rahmati, M.; Doostvandi, F.; Mostafavi, M.A. Comparison of the analytic network process and the best–worst method in ranking urban resilience and regeneration prioritization by applying geographic information systems. Land 2024, 13, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Tian, D.; Zhang, M.; Hou, Y. Spatial green space accessibility in Hongkou District of Shanghai based on Gaussian two-step floating catchment area method. Buildings 2023, 13, 2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumm, O.; Zeringue, R.; Dong, N.; Carlow, V.M. Green densities: Accessible green spaces in highly dense urban regions—A comparison of Berlin and Qingdao. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukhnovskyi, V.; Zibtseva, O. Green space trends in small towns of Kyiv region according to EOS Land Viewer–a case study. J. For. Sci. 2020, 66, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, S.; Nori-Sarma, A.; Kim, S.; Lee, J.-T.; Bell, M.L. Do persons with low socioeconomic status have less access to greenspace? Application of accessibility index to urban parks in Seoul, South Korea. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 084027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghrabi, A.; Alyamani, A.; Addas, A. Exploring pattern of green spaces (Gss) and their impact on climatic change mitigation and adaptation strategies: Evidence from a saudi arabian city. Forests 2021, 12, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuklina, V.; Sizov, O.; Fedorov, R. Green spaces as an indicator of urban sustainability in the Arctic cities: Case of Nadym. Polar Sci. 2021, 29, 100672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taubenböck, H.; Reiter, M.; Dosch, F.; Leichtle, T.; Weigand, M.; Wurm, M. Which city is the greenest? A multi-dimensional deconstruction of city rankings. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2021, 89, 101687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Singh, R.; Bryant, C.; Raghubanshi, A.S. Green space indicators in a social-ecological system: A case study of Varanasi, India. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 60, 102261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Rahman, M.M.; Momotaz, M. Environmental quality evaluation in Dhaka City Corporation–using satellite imagery. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Urban Des. Plan. 2019, 172, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Lin, T.; Zhao, Q.; Li, X.; Ye, H.; Zhang, G.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Y. Spatial pattern of urban green spaces in a long-term compact urbanization process—A case study in China. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 96, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, M.; Haase, D. Mediating sustainability and liveability—Turning points of green space supply in European cities. Front. Environ. Sci. 2019, 7, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Haase, D.; Pauleit, S. The impact of different urban dynamics on green space availability: A multiple scenario modeling approach for the region of Munich, Germany. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 93, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morar, T.; Radoslav, R.; Spiridon, L.C.; Păcurar, L. Assessing pedestrian accessibility to green space using GIS. Transylv. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2014, 10, 116–139. [Google Scholar]

- Senanayake, I.; Welivitiya, W.; Nadeeka, P. Urban green spaces analysis for development planning in Colombo, Sri Lanka, utilizing THEOS satellite imagery–A remote sensing and GIS approach. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onder, S.; Polat, A.T.; Korucu, S. The evaluation of existing and proposed active green spaces in Konya Selçuklu District, Turkey. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2011, 6, 738–747. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Li, S.; Lei, H.; Zhao, N.; Liu, C.; Fang, J.; Liu, X.; Lu, S.; Xu, X. Application of High-Spatial-Resolution Imagery and Deep Learning Algorithms to Spatial Allocation of Urban Parks’ Supply and Demand in Beijing, China. Land 2024, 13, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.S.; Hammo, Y.H. Evaluate of Green space (Parks) in Duhok city by use Image satellite, Google earth, GIS,(NDVI), and Field survey Techniques. Kufa J. Agric. Sci. 2023, 15, 73–92. [Google Scholar]

- Deliry, S.I.; Uyguçgil, H. Accessibility assessment of urban public services using GIS-based network analysis: A case study in Eskişehir, Türkiye. GeoJournal 2023, 88, 4805–4825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, D.; Wolff, M. Enabling ecosystem services at the neighborhood scale while allowing for urban regrowth: The case of Halle, Germany. Ecol. Soc. 2022, 27, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushkani, R.A.; Ono, H. Spatial equity of public parks: A case study of Kabul city, Afghanistan. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Yang, F.; Wu, L.; Gao, X. Equity evaluation of urban park system: A case study of Xiamen, China. J. Environ. Eng. Landsc. Manag. 2020, 28, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wüstemann, H.; Kalisch, D.; Kolbe, J. Access to urban green space and environmental inequalities in Germany. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 164, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Pussella, P. Is Colombo city, Sri Lanka secured for urban green space standards? Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2017, 15, 1789–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Strohbach, M.; Haase, D.; Kronenberg, J. Urban green space availability in European cities. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 70, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pristeri, G.; Peroni, F.; Pappalardo, S.E.; Codato, D.; Masi, A.; De Marchi, M. Whose urban green? mapping and classifying public and private green spaces in Padua for spatial planning policies. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riad, P.; Graefe, S.; Hussein, H.; Buerkert, A. Landscape transformation processes in two large and two small cities in Egypt and Jordan over the last five decades using remote sensing data. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 197, 103766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y. Does economic development improve urban greening? Evidence from 289 cities in China using spatial regression models. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2018, 190, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, P.Y.; Wang, J.; Sia, A. Perspectives on five decades of the urban greening of Singapore. Cities 2013, 32, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zeng, P.; Xie, X.; Chen, D. Equitable evaluation of supply-demand and layout optimization of urban park green space in high-density linear large city. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0310015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Meng, Q.; Liu, X.; Allam, M.; Zhang, L.; Hu, X.; Bi, Y.; Jancsó, T. Evaluation of fairness of urban park green space based on an improved supply model of green space: A case study of Beijing central city. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yan, G.; Wang, S. Fairness evaluation of landscape justice in urban park green space: A case study of the Daxing Part of Yizhuang New Town, Beijing. Sustainability 2022, 15, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laan, C.M.; Piersma, N. Accessibility of green areas for local residents. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2021, 10, 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-González, O.M. The green areas of san juan, Puerto Rico. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Li, X.; Song, D.; Zhai, H. Evaluation and monitoring of urban public greenspace planning using landscape metrics in Kunming. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Liu, L.; Yu, Y.; Peng, Z. Evaluation and planning of urban green space distribution based on mobile phone data and two-step floating catchment area method. Sustainability 2018, 10, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzywnicka, I.; Jankowska, P. The accessibility of public urban green space. A case study of Białystok city. Acta Sci. Pol. Adm. Locorum 2021, 20, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, K.A.; Zhang, D. Analyzing the level of accessibility of public urban green spaces to different socially vulnerable groups of people. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelan, E.; Girma, Y. Urban green infrastructure accessibility for the achievement of SDG 11 in rapidly urbanizing cities of Ethiopia. GeoJournal 2021, 87, 2883–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Bardhan, S. Overview: Framework for quantitative assessment of Urban-Blue-and-Green-spaces in a high-density megacity. Int. Rev. Spat. Plan. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 10, 280–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Ma, S.; Cheng, K.; Kyriakopoulos, G.L. An evaluation system for sustainable urban space development based in green urbanism principles—A case study based on the Qin-Ba mountain area in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoari, N.; Ezzati, M.; Baumgartner, J.; Malacarne, D.; Fecht, D. Accessibility and allocation of public parks and gardens in England and Wales: A COVID-19 social distancing perspective. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Albert, C.; Von Haaren, C. Equality in access to urban green spaces: A case study in Hannover, Germany, with a focus on the elderly population. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 55, 126820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsi, F. How densely populated and green are the places we live in? A study of the ten largest US cities. Land Use Policy 2018, 76, 300–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, H.S.H.; Routray, J.K. From socioeconomic disparity to environmental injustice: The relationship between housing unit density and community green space in a medium city in Pakistan. Local Environ. 2018, 23, 536–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Rajak, F. Informal green space contribution to city’s recreational green open space need of a densely populated old city: A case of Patna, India. GeoJournal 2024, 89, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.-T.-H.; Labbé, D. Spatial logic and the distribution of open and green public spaces in Hanoi: Planning in a dense and rapidly changing city. Urban Policy Res. 2018, 36, 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusseau, D.; Baillie, R. Disparities in greenspace access during COVID-19 mobility restrictions. Environ. Res. 2023, 225, 115551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- bin Nor Azhar, A.S.; Hussain, M.R.b.M.; Tukiman, I. The Sustainability of Urban Green Space during Pandemic Crises. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1135, 012043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharp, K.M. Thematic co-occurrence analysis: Advancing a theory and qualitative method to illuminate ambivalent experiences. J. Commun. 2021, 71, 545–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedighi, M. Application of word co-occurrence analysis method in mapping of the scientific fields (case study: The field of Informetrics). Libr. Rev. 2016, 65, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Kim, G. History of Seoul’s parks and green space policies: Focusing on policy changes in urban development. Land 2022, 11, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukhnovskyi, V.Y.; Zibtseva, O.V.; Debryniuk, I.M. Evaluation of green space systems in small towns of Kyiv region. Bull. Geography. Socio-Econ. Ser. 2021, 53, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bille, R.A.; Jensen, K.E.; Buitenwerf, R. Global patterns in urban green space are strongly linked to human development and population density. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 86, 127980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jombach, S.; Hassan, Y.N.; Wagner, J.R.; Du, C.; Sölch, B.; Üsztöke, L. Changes in Green Space Intensity in Újbuda, in Budapest’s 11th district. 4D Tájépítészeti Kertművészeti Folyóirat 2024, 74, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Ye, Y.; Zhou, T.; Haase, D.; Lausch, A. Effectiveness Trade-Off Between Green Spaces and Built-Up Land: Evaluating Trade-Off Efficiency and Its Drivers in an Expanding City. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, L.; Hanaei, T. Comparative analysis of key factors influencing urban green space in Mashhad, Iran (1988–2018). Environ. Syst. Res. 2024, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigolon, A. A complex landscape of inequity in access to urban parks: A literature review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 153, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Liu, Y.; He, M. The spatial interaction effect of green spaces on urban economic growth: Empirical evidence from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saher, R.; Stephen, H.; Ahmad, S. Role of urban landscapes in changing the irrigation water requirements in arid climate. Geosciences 2022, 13, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Song, Y.; Lu, W. Effect of urban green space in the hilly environment on physical activity and health outcomes: Mediation analysis on multiple greenery measures. Land 2022, 11, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Chamberlain, B.; Park, H.Y. Toward a Construct-Based Definition of Urban Green Space: A Literature Review of the Spatial Dimensions of Measurement, Methods, and Exposure. Land 2025, 14, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobáľová, H.; Falťan, V.; Benová, A.; Kožuch, M.; Kotianová, M.; Petrovič, F. Measuring the quality and accessibility of urban greenery using free data sources: A case study in Bratislava, Slovakia. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 93, 128217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Yang, L.E.; Zeng, F.; Jia, J.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Z. Enabling urban climate resilience through integrated optimization of urban design. Front. Sustain. Cities 2025, 7, 1657008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Review Title | Main Focus | UGS Measurement | Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Determinants influencing the accessibility and use of urban green spaces: A review of empirical evidence [36] | Urban planning | Accessibility, Proximity, Socioeconomic factors | Spatial/Quantitative |

| 2 | The effects of neighbourhood green spaces on mental health of disadvantaged groups: a systematic review [37] | Mental health | Exposure, Availability, Equity of access | Spatial/Functional |

| 3 | A systematic review of the impact of changes to urban green spaces on health and education outcomes, and a critique of their applicability to inform economic evaluation [38] | Physical and mental health, Educational results | Change in UGS (extent and quality) | Temporal/Quantitative |

| 4 | Urban heatwave, green spaces, and mental health: A review based on environmental health risk assessment framework [39] | Mental health | Vegetation cover, Cooling capacity, Heat mitigation | Quantitative/Functional |

| 5 | Exploring the restorative capacity of urban green spaces and their biodiversity through an adapted one health approach: A scoping review [40] | Psychological restoration | Biodiversity, Restorative potential | Functional/Qualitative |

| 6 | Multiple roles of green space in the resilience, sustainability and equity of Aotearoa New Zealand’s cities [35] | Equity, Sustainability. | UGS per capita, Resilience, Equity | Quantitative/Functional |

| 7 | Health effects of participation in creating urban green spaces—a systematic review [41] | Health | Participation, Engagement, Co-creation | Qualitative/Functional |

| 8 | Green space in health research: An overview of common indicators of greenness [42] | Health | NDVI, Land cover, Proximity | Quantitative/Spatial |

| 9 | A review of the effects of urban and green space forms on the carbon budget using a landscape sustainability framework [43] | Sustainability (Carbon storage) | Vegetation type, Area, Spatial configuration | Spatial/Quantitative |

| 10 | A systematic review of audit tools for evaluating the quality of green spaces in mental health research [44] | Mental health | Quality (design and maintenance) | Qualitative/Functional |

| Response Combination | No | Yes | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| exclude + exclude | 0 | 18.6 | |

| exclude + maybe | 1 | 35.0 | |

| include + exclude or maybe + maybe | 2 | 18.7 | |

| include + maybe | 3 | 16.2 | |

| include + include | 4 | 11.4 |

| Terminology | Frequency of Occurrence | Sources |

| Urban green space(s) | 32 | [22,29,30,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74] |

| Green space(s) | 16 | [75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90] |

| Urban park | 10 | [33,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99] |

| Urban green(ing) | 04 | [100,101,102,103] |

| Urban park green space | 03 | [104,105,106] |

| Green area | 02 | [107,108] |

| Urban public greenspace | 02 | [109,110] |

| Public urban green space(s) | 02 | [111,112] |

| Urban green infrastructure | 01 | [113] |

| Urban-blue-and-green-spaces (UBGS) | 01 | [114] |

| Green land area | 01 | [115] |

| Public parks and gardens | 01 | [116] |

| Green and blue infrastructure | 01 | [117] |

| Park areas and greenery | 01 | [118] |

| Community green space | 01 | [119] |

| Urban green open space | 01 | [120] |

| Open and green public space(s) | 01 | [121] |

| Sources | Year | UGS Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| [47] | 2024 | UGS Index, Landscape Metrics and Pattern (Composition and Configuration) |

| [46] | 2024 | Inequality, Social Equity, Green Supply |

| [91] | 2024 | Parkland Distribution Pattern, Accessibility |

| [104] | 2024 | UPGS Accessibility, Social Equity, Supply–Demand Matching, Optimization |

| [29] | 2024 | Accessibility, Proximity, UGS Typologies |

| [48] | 2024 | UGS Quantity and Scale, UGS Spatial Patterns, Accessibility, Equity |

| [49] | 2024 | UGS Identification (Vegetation Index) Spatio-temporal Change, Accuracy Assessment |

| [120] | 2024 | Accessibility, Catchment Area, Informal Green Open Spaces Typologies, Quality analysis |

| [75] | 2024 | Urban Resilience, Regeneration Prioritization |

| [50] | 2024 | Green Space Classification, Pattern, UGS Index, Accessibility, Proximity |

| [92] | 2023 | Quantitative Measurement, Pattern Analysis (Remote Sensing Indices) |

| [105] | 2023 | Fairness and Equity Assessment, Accessibility, Supply and Demand, Optimization Modeling, UGS Quality |

| [51] | 2023 | Quantitative Measurement, Pattern Analysis (Remote Sensing Indices, Image Classification) |

| [52] | 2023 | Supply and Demand, Optimization Modeling, Cost–Benefit Analysis |

| [106] | 2023 | Accessibility, Fairness and Equity Assessment, Proximity, Pattern Analysis (Spatial Autocorrelation) |

| [53] | 2023 | Quantitative Measurement, Pattern Analysis, Supply and Demand, Optimization Modeling |

| [54] | 2023 | Fairness and Equity Assessment, Quantitative Measurement, Statistical Analysis |

| [93] | 2023 | Accessibility, Proximity, Supply and Demand, Optimization Modeling |

| [76] | 2023 | Accessibility, Pattern Analysis (Clustering, Interpolation) |

| [55] | 2022 | Quantitative Measurement, Pattern Analysis (Remote Sensing Indices, Image Classification) |

| [56] | 2022 | Accessibility, Spatial Pattern, Analysis Suitability Analysis |

| [113] | 2022 | Accessibility (Distance Approach) (Service Area) |

| [22] | 2022 | Accessibility, Proximity, Compound Metric (Accessible UGS per capita) |

| [57] | 2022 | UGS Justice, UGS Quantity (Supply), Accessibility |

| [58] | 2022 | Hierarchical UGS Mapping, Vegetation Detection, UGS Index |

| [114] | 2022 | Urban Blue Green Space Distribution Index, UBGS Availability Index |

| [77] | 2022 | Density Dimensions, Vegetation Identification, Accessible Recreational Green Space |

| [59] | 2022 | Inequality Measurement, ecosystem services |

| [60] | 2022 | Accessibility, and Attractiveness (Quality). |

| [94] | 2022 | Ecosystem Service Provision (Air Cooling), (Hydrological), Carbon Mitigation) |

| [61] | 2022 | Trend in UGS |

| [62] | 2021 | Accessibility |

| [78] | 2021 | Green Infrastructure Provision |

| [107] | 2021 | Accessibility (Minimal Walking Distance) |

| [63] | 2021 | Green Provision, Quality, Urban Green Volume |

| [79] | 2021 | UGS Access Inequality (Socioeconomic Status) |

| [64] | 2021 | Equity, UGS Quantity, Accessibility |

| [95] | 2021 | Place-based Equity (Horizontal Equity), Population-based Equity (Vertical Equity) |

| [65] | 2021 | Equality of Accessing Green Spaces, Access to UGS, Access to Parks (PGS) |

| [66] | 2021 | UGS Quantity and Coverage Environmental Outcome |

| [80] | 2021 | Climatic Mitigation, Ecosystem Benefits |

| [109] | 2021 | Pattern analysis, Configuration, Average Greening Index |

| [67] | 2021 | UGS Change Index |

| [68] | 2021 | Equality, Inequality (Distributional Equity) |

| [81] | 2021 | Vegetation Mapping, Classification, Accuracy Assessment |

| [111] | 2021 | Evaluation, Accessibility |

| [100] | 2021 | UGS Classification (Property and Use) |

| [82] | 2021 | UGS Classification, City Rankings |

| [115] | 2020 | Ecological Space Construction, Infrastructure Perfection (Accessibility) |

| [116] | 2020 | Crowdedness, Spatial Proximity, Catchment Area |

| [101] | 2020 | Landscape Transformation, Change Detection |

| [69] | 2020 | Accessibility, Spatial Distribution, Equity |

| [70] | 2020 | Equity (Horizontal and Vertical Equity) Park Supply Index, Proximity and Quality |

| [117] | 2020 | Urban Green Blue Infrastructure Accessibility, Equality |

| [83] | 2020 | Green space distribution, accessibility indicators |

| [96] | 2020 | Equity evaluation, Area-weighted Park Service Level |

| [84] | 2019 | Environmentally critical area, Determined qualitatively (CO, PM10, and PM2.5) |

| [71] | 2019 | spatial distribution, Mapping UGS Density of Greenness, UGS Index |

| [85] | 2019 | Spatial Characteristics and Pattern of GS, distribution |

| [72] | 2019 | Proximity, Accessibility, Distribution disparity |

| [86] | 2019 | Green Space Supply, Green Space pressure |

| [110] | 2018 | Supply and Demand analysis, UGS accessibility, Spatial distribution |

| [112] | 2018 | Accessibility, Time–Distance Weighted Technique, Spatial Equity |

| [73] | 2018 | Availability, Green Index |

| [102] | 2018 | Spatial Autocorrelation of Greening Indices, Relationship Between Greening and Socio-economic Variables |

| [74] | 2018 | Accessibility (Objective measures) Subjective Perception of UGS Accessibility |

| [87] | 2018 | Accessibility, Urban Dynamics, Multiple Scenario Modeling Approach |

| [119] | 2018 | Relationship Between Housing Density and Green Space Provision |

| [121] | 2018 | Spatial Accessibility, Proximity (Physical, Spatial accessibility) |

| [118] | 2018 | Population density (Density Indicator), UGS Change Analysis |

| [30] | 2017 | UGS Distributional inequities, Relationship between Socioeconomic conditions and UGS |

| [97] | 2017 | Accessibility, Environmental inequalities |

| [98] | 2017 | UGS Coverage Change Analysis |

| [99] | 2016 | UGS availability (Spatial availability) |

| [33] | 2014 | Accessibility, Unequal Distribution, Inequality |

| [108] | 2014 | Spatial Patterns of Green Areas |

| [88] | 2014 | Pedestrian accessibility (Network distance) |

| [89] | 2013 | Green Space Classification, Environmental Indices (SO2 or NO3) |

| [103] | 2013 | Distribution of UGS, Vegetation Quality |

| [90] | 2011 | UGS Distribution, Accessibility |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hassan, Y.N.; Jombach, S. Urban Green Space per Capita for Sustainable and Equitable Urban Planning: A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Land 2026, 15, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010029

Hassan YN, Jombach S. Urban Green Space per Capita for Sustainable and Equitable Urban Planning: A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Land. 2026; 15(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010029

Chicago/Turabian StyleHassan, Yaseen N., and Sándor Jombach. 2026. "Urban Green Space per Capita for Sustainable and Equitable Urban Planning: A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis" Land 15, no. 1: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010029

APA StyleHassan, Y. N., & Jombach, S. (2026). Urban Green Space per Capita for Sustainable and Equitable Urban Planning: A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Land, 15(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010029