Abstract

The Calakmul Biosphere Reserve, in southeastern Mexico, is a major conservation area known for its tropical forests, emblematic wildlife species, and long history of Maya occupation. Established in 1989 as a federal Natural Protected Area, it was incorporated into UNESCO’s Man and the Biosphere Program in 1993 and designated a mixed World Heritage Site in 2014. Its socioecological trajectory is distinctive: conservation efforts advanced alongside the contemporary rural settlement resulting from agrarian reform and subsequent development and welfare policies. This article examines the persistent imbalance between ecological conservation and socioeconomic development surrounding the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve, focusing on water vulnerability in adjacent communities. The study integrates environmental history with household-level survey data on water access and vulnerability among 200 households in eight communities in the Biosphere Reserve’s transition zone, complemented by interviews with key water-management stakeholders. We document the consolidation of conservation through management plans, advisory councils, payments for ecosystem services, scientific research, and expanding voluntary conservation areas. Yet these advances contrast sharply with everyday socioeconomic realities: 68% of households face prolonged water scarcity, with an average of more than 30 days annually without water. Calakmul’s case highlights structural mismatch between conservation and local human well-being in Natural Protected Areas contexts.

1. Introduction

Since the 1980s, the global conservation agenda has increasingly confronted a central conflict: how to balance biodiversity and ecosystem conservation with human well-being. Although Natural Protected Areas (NPAs) are important instruments for sustainable development [1], their establishment often restricts land use and access to resources for neighboring populations, failing to consider local livelihoods [2], especially in the Global South. This challenge has sparked extensive academic debate, policy innovation, and community mobilization. Critical academic approaches argue that exclusionary models of conservation, rooted in colonial legacies and fortress-like paradigms, have failed to deliver equitable outcomes [3,4,5]. In response, integrated conservation and development models, including participatory governance, have been promoted as alternatives [6]. However, despite their theoretical promise, the implementation of these models remains fraught with tensions, trade-offs, and uneven outcomes.

Sustainable development is a framework that specifically recognizes the interdependence of ecological integrity and human development as global goals [7,8,9]. The UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide the current framing for these and other objectives [7]. For example, this integrated vision is reflected particularly in goals and targets that link ecosystem conservation with human well-being, such as SDG 1 (Target 1.4), SDG 6 (Target 6.6), SDG 10 (Target 10.2), SDG 12 (Target 12.2), SDG 15 (Targets 15.1 and 15.9), as well as SDG 17 (Target 17.14), which emphasizes policy coherence for sustainable development [10]. However, in practice, there can be tensions between the delivery of environmental and social development targets [11,12], especially in environmentally strategic regions where conservation policies may prioritize ecosystem protection over sustained construction of social welfare, leading to trade-offs, conflicts, and uneven social outcomes [13,14,15].

Mexico’s Biosphere Reserve model is one of the NPA approaches adopted to promote more inclusive conservation schemes [16,17]. Originating in the early 1970s under UNESCO’s Man and the Biosphere (MAB) Program, the Biosphere Reserve model was designed to reconcile conservation and development by incorporating human populations into the management and governance of protected landscapes [17,18]. In Mexico, this model introduced a zoning system—core, buffer, and transition areas—that allows different levels of human activity depending on the sensitivity of surrounding ecosystems.

In core zones, ecosystem and species conservation are priorities. In adjacent buffer zones, compatible activities such as scientific research, environmental education, and sustainable tourism are permitted. Finally, transition or influence zones actively promote sustainable development by integrating local communities into economic and human activities designed to maintain environmental balance [19]. This framework is designed to support biodiversity and ecosystem protection while also fostering sustainable livelihoods [20]. Biosphere Reserves are therefore considered the MAB’s Program’s primary contribution to sustainable development [21]. The use of the biosphere reserve approach in Mexico has been celebrated for promoting community participation, decentralized management, and the integration of social and ecological priorities [22]. Yet, despite four decades of implementation, structural limitations have emerged. While zoning has offered some flexibility in different contexts, it has not resolved underlying power asymmetries between governmental agencies, conservation NGOs, and local populations [23]. Moreover, the socioeconomic benefits expected from conservation-driven development have often failed to materialize, particularly in marginalized rural communities [24,25,26,27].

These shortcomings are not solely the result of inadequate design, but rather, they are deeply embedded in a system of social relations, power structures and worldviews that underpin conservation agendas. As Durand [28] argues, asymmetrical structures with many actors often produce “unequal natures” shaped by different interests, knowledge systems, and access to decision-making arenas. Consequently, the ideal of integrated conservation and development remains aspirational rather than reality. The Calakmul Biosphere Reserve (CBR) illustrates both the promises and pitfalls of the Biosphere Reserve model.

Established in 1989 and designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2014 for its ecological and cultural significance [29], the CBR serves as a vital stronghold for tropical biodiversity. It should also be a bastion for the well-being of its heterogeneous human population. Immigration to the area began in 1970 and was characterized by policies of colonization, internal migration, infrastructure development, and the creation of ejidos (communal lands) [30]. However, since that decade, relations between the government and the local population have been particularly difficult in Calakmul. As Haenn [31] notes, both conservation and development have been invoked in the region as promises to gain public support for political parties and large-scale projects, including the CBR itself. Yet, these commitments have not translated through sustainable development. Achieving conservation and development simultaneously requires participation of the local population in a policy design that is genuinely responsive to local needs [32], promoting inclusion, transparency, and co-responsibility between government and society (e.g., participatory budgets, citizen councils, open councils, etc.) [33]. In addition, sustainable development requires effective leadership, multi-level governance and policy coherence [34].

This study examines the relationship between conservation and development around the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve. We use water vulnerability as an analytical lens, given that access to safe drinking water is one of the key indicators of social well-being in rural communities. We also draw on Calakmul residents’ local perceptions, a crucial dimension of local water narratives, to critically explore the relationships between conservation objectives and human well-being. Thus, the overall objective of this study is to examine how the systematic failure to fulfill regional development commitments has perpetuated inequalities and unsustainable practices in access to water within a Biosphere Reserve that is paradoxically promoted under the banner of sustainable development. The specific objectives are to (i) characterize household-level water insecurity; (ii) analyze local perceptions of water provision; and (iii) identify mismatches between conservation policies and development commitments. Accordingly, the central research question guiding this study is as follows: How are unfulfilled regional development promises reflected in the persistent lack of equitable and sustainable access to water in a region promoted through a sustainable development discourse? To answer this question, a mixed-methods approach was used, combining surveys distributed to 200 households in eight communities and semi-structured interviews with stakeholders, framed within an environmental historical perspective that traces the misalignment between conservation and development plans and social welfare policies in the region. We show how rural households across communities in the CBR buffer and transition zones still suffer from water insecurity despite the development commitments that came with the creation of the CBR

Unveiling the Social Dimension of Water Vulnerability

Around half of the world population experiences water scarcity and one quarter faces high levels of water stress [35]. In recent decades, global attention has increasingly focused on the complex interactions between humans and water in the search for alternatives to mitigate the water crisis, particularly due to its entanglement with broader social challenges such as extreme inequality, economic and demographic growth patterns, and climate uncertainty [36]. The global water agenda has gradually shifted from a predominantly technical paradigm toward one of political governance that embraces human rights, climate change, and international cooperation (e.g., SDG 6: “Clean Water and Sanitation”). However, transforming this agenda into a meaningful sustainability framework requires, among other actions, integrating local voices into global decision-making to achieve equitable governance [37,38].

From a water governance perspective, water scarcity, water stress and water insecurity are interrelated dimensions that reflect not only biophysical constraints but also institutional arrangements, power relations, and management capacities. Water scarcity describes the structural condition of there being insufficient water to meet human and environmental demands, while water stress expresses the pressure exerted by withdrawals on available water resources [39,40]. Water insecurity broadens this framework by incorporating dimensions of access, quality, reliability, and equity. This highlights that water problems persist even where the resource exists, but is governed in an unequal or exclusionary manner [41,42].

Water insecurity, the main concept addressed throughout the article, is defined as insufficient and unsafe access to drinking water [43]. It is a technical, environmental, and above all social problem, because social structures such as poverty and political exclusion deeply influence it [44]. For instance, factors such as water infrastructure, monthly income, gender, age, and citizenship influence household water security [43,44]. Access to safe drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene is essential for health, dignity, equity, and sustainable development. Its ratification as a human right in 2010 reinforced its centrality and importance on the global agenda [45]. Effectively implementing this right can transform lives, reduce inequalities, and contribute significantly to human well-being. Nevertheless, much remains to be done to design water governance frameworks that respect cultural contexts and derive legitimacy from local realities. Such frameworks can be strengthened by incorporating environmental perceptions into public policy design, thereby enhancing public participation and helping to reconcile scientific approaches with the worldviews of local populations [46,47]. Perceptions have been shown to shape behavior: for instance, institutional distrust negatively impacts individuals’ engagement in water conservation or reuse initiatives, whereas higher trust levels tend to encourage confidence and participation [48].

Water insecurity for humans has been recorded in NPAs. The UNESCO report on vulnerability and risk to climate change in Biosphere Reserves and Global Geoparks in Latin America and the Caribbean [49] identified that 10.7 million people are exposed to water supply disruptions and, in some places, 100% of the population is affected. Problems with access to water are not unique to NPAs; many communities worldwide face similar challenges. However, habitat conservation in these areas can contribute to human well-being by regulating and providing resources such as water [50]. Protected areas such as Biosphere Reserves are designed to play a crucial role in safeguarding water resources and supporting sustainability strategies in local communities [49]. However, when management schemes operate in a centralized and sectorial manner, they can reproduce tensions between ecosystem protection and local water security, limiting the simultaneous achievement of environmental and social objectives [40,42].

It is, thus, paradoxical that communities within PNAs can still experience water insecurity. Several studies [50,51,52] have emphasized that conservation and social development must be addressed jointly through inclusive, equitable, and participatory approaches that better align conservation goals with human needs. Empirical work on Biosphere Reserves in Asia, Europe and Latin America shows progress in areas such as local stakeholder participation, strengthened co-management, greater investment in training and employment, and the integration of local values and regional networks [53,54,55,56,57,58]. Shifting from purely ecological reserves to biocultural ones offers a promising pathway toward a more balanced relationship between nature and society [59]. Yet, many reserves still operate through top-down governance, lack adequate funding for community well-being, and remain disconnected from Indigenous and smallholder practices.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The municipality of Calakmul is geographically bordered to the north by the municipalities of Hopelchen and Champoton, to the west by Escarcega and Candelaria, to the east by the state of Quintana Roo and Belize, and to the south by the Republic of Guatemala [60]. The CBR is practically immersed and almost entirely covered by the municipality of Calakmul, integrating a substantial part of the municipal territory with functions of ecological conservation and sustainable use of natural resources. Only a small portion of the north of the CBR is located in the municipality of Hopelchen [61].

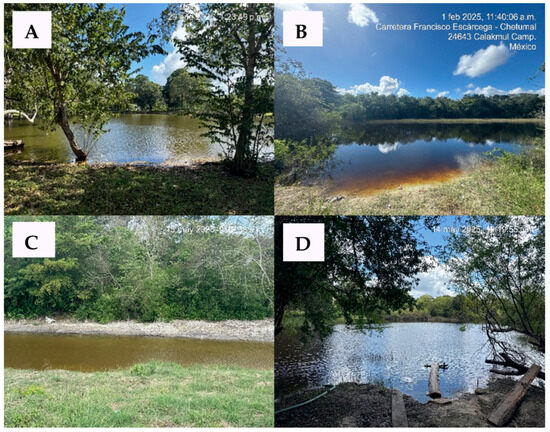

The municipality of Calakmul, including the CBR, lies in a karstic zone with dry tropical conditions characterized by high temperatures and intense evapotranspiration [62]. More than 90% of the Reserve is covered by vegetation, predominantly tropical dry forest [63]. This forest cover plays a critical role in regional water capture and helps connect the forested landscapes of Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize, maintaining ecological continuity across the Maya forest. The area hosts exceptional biodiversity, including over 80% of the plant species in the Yucatan Peninsula, 350 bird species, and nearly 100 mammal species, several of them threatened or endangered [64]. Flora and fauna in the CBR face harsh environmental conditions, marked by a scarcity of surface water due to the karst, resulting in a low density of natural water bodies (an average of one seasonal natural pond, locally called aguada, per 535 hectares) [65,66]. Different forms of surface water bodies occur (Figure 1). In past decades, rainfall has also been declining [62,67].

Figure 1.

Surface water bodies in the Calakmul region. (A) Aguada (seasonal natural ponds fed by rainwater) in Centauro del Norte, (B) Jagüey (artificial rainwater reservoir) in Valentin Gomez Farias, (C) Corriental (intermittent stream that flows during part of the year in response to seasonal rains) in Manuel Castilla Brito, (D) Aguada in El Refugio.

The current structure and composition of Calakmul’s forests reflect long-standing interactions between people and the environment. The landscape still shows the imprint of ancient Maya agricultural and silvicultural practices, shaped by human selection and natural regeneration [64]. Culturally, Calakmul is notable for its archaeological remains, more than 1500 years old, which are key to understanding the rise of the Preclassic and Classic Maya civilization in a challenging tropical forest setting and the factors that led to its decline [68].

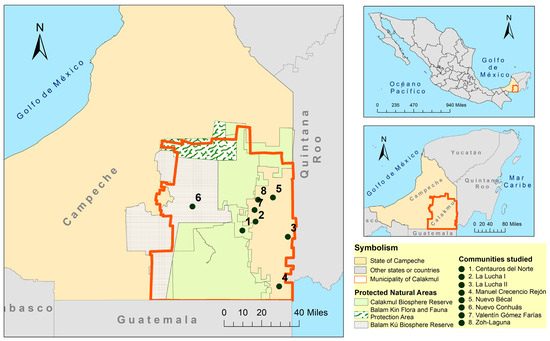

After the Maya civilization declined in population around 950 AD, the region remained largely uninhabited due to its inaccessibility and lack of surface water. It was not until the early 20th century that demand for chicozapote (Manilkara zapota) latex drew gum collectors to the area, followed by the establishment of logging camps in the 1940s. Still, the population remained small, as did government investment in infrastructure [30]. Major repopulation occurred in the 1960s and 1970s under government-led internal colonization policies [69]. Mexico promoted migration to tropical regions to expand agricultural frontiers, drawing marginalized rural populations seeking better opportunities [70]. Calakmul was ultimately settled by people from more than 23 Mexican states, and by 2020 had 31,714 inhabitants across 184 communities [71]. Most residents engage in subsistence agriculture (corn, beans, squash) and commercial crops (jalapeño peppers), complemented by livestock, beekeeping, forestry programs, and labor migration (to the United States and the Mayan Riviera) [72]. Despite these efforts, communities have remained predominantly rural and materially deprived. In 2020, of 8037 inhabited dwellings, only 14.5% had piped water, 51.9% had a cistern, 64.2% had a refrigerator, and 22.2% had a car [73]. Our study was developed in eight communities within the CBR’s influence area and buffer zone (Figure 2). The settlements were established in an area historically characterized by limited water availability and have since faced additional declines in rainfall, creating persistent and growing conditions of water scarcity.

Figure 2.

Map of studied communities and Natural Protected Areas in the municipality of Calakmul, Mexico. Source: Karina Noemí Chale Silveira.

By the 1980s, the expansion of the agricultural frontier had driven major land-use changes and loss of mature forests. This threatens ecological connectivity through increasing habitat fragmentation. In response, researchers and public officials proposed creating the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve, which was established in 1989 to protect the region’s exceptional ecological and cultural richness [74].

2.2. Instruments and Data Collection Techniques

In our methodological approach, we started with a historical review of how the environmental agenda and development projects emerged in the region, offering a perspective that links national and international conservation agendas to the current situation of local communities. We then carried out documentary research drawing on regulatory and technical documents, development plans, and government reports related to Calakmul. These included municipal meeting minutes, the CBR management program, official reports submitted to UNESCO by agencies such as the National Commission for Protected Natural Areas (CONANP), the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), as well as UNESCO’s corresponding assessments and responses. This was complemented by archival research and a review of scientific literature.

Fieldwork took place between 2023 and 2025, using a mixed-methods approach with a qualitative emphasis, including participant observation with detailed field notes and photographs. Initial visits were exploratory, aimed at understanding the social–ecological context and identifying key stakeholders. During this phase, we conducted a brief diagnostic survey to assess water-related issues across the region, though the data were not analyzed in depth for the present study. This short survey was carried out in 20 communities selected primarily for their geographic distribution—north, south, southeast, and west—to capture a comprehensive municipal-level perspective. In each community, sampling continued until no new information emerged, indicating saturation at an average of six surveys per community [75].

Building on insights from the exploratory phase, we developed a detailed survey for subsequent visits. It consisted of 71 questions grouped into five thematic sections: respondent demographics; perception of agency by the community; access to and use of water; vulnerability, perception of risk, attribution of responsibility, and adaptive responses; climate change (Survey S1: Water situation in the Calakmul region, Mexico). For the purposes of this paper, we focus exclusively on the analysis of household water sources and water vulnerability. We applied this detailed survey in eight communities (Figure 2). Five had already been visited during the exploratory phase (Nuevo Conhuas, Nuevo Becal, Lucha I, Lucha II, and Valentín Gómez Farías), and three were newly added (Centauro del Norte, Manuel Crescencio Rejon, and Zoh-Laguna; see Figure 2). The selection of communities was based primarily on their access or not to piped water, and subsequently their geographical location.

We applied the survey to 20% of the households in each community. According to the 2020 census [71], there are 8037 inhabited dwellings in the municipality. Of these, 1009 correspond to the eight communities visited. Households were surveyed through convenience sampling. In practice, this meant going from house to house and interviewing any available and willing individuals. As a result, most respondents were women (Table 1), since men are often working in their plots or outside the community during the day. This gender bias proved beneficial: due to traditional gender roles, women are typically more knowledgeable about household water management [44]. Nonetheless, this convenience sampling strategy of selecting 20% of households in each community allowed us to obtain detailed information despite logistical constraints in the territory. However, the results are not statistically representative of the entire population. Due to limitations in statistical representativeness, the findings should be interpreted as contextual evidence relevant to the analysis of local governance, rather than as generalizable population inferences. More accessible households are likely to be overrepresented, as was the case with the female population [76,77]. In total, we administered 204 surveys, although four were later excluded due to incomplete information, as respondents chose to terminate the survey early for personal reasons.

Table 1.

Socioeconomic profile of the people surveyed in the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve. Source: Prepared internally based on the following sources [71,78,79,80].

We also conducted 15 semi-structured interviews, based on a guide of six open-ended questions, with key stakeholders identified during the exploratory and main research phases. These actors represented a range of sectors, including community leaders, government officials, and non-governmental organizations. Throughout the article, we use testimonies collected from these interviews. Interviews were conducted throughout fieldwork, mostly by appointment, depending on the availability of each interviewee.

All data collection instruments were administered with the informed consent of participants. A printed consent form was available, which we read and explained to each participant to obtain their informed consent verbally. This approach was adopted because participants expressed discomfort with signing documents. Additionally, we requested prior permission from the relevant authorities in each community for field visits and the application of instruments in households, both out of respect for them and to ensure the safety of the research team. During the interviews, participants were also asked for permission to audio-record the conversation, or alternatively, to allow note-taking if they declined to be recorded (Letter of Opinion S1: Outcome from the ethics committee).

2.3. Data Analysis

The data we collected over the nearly two years of fieldwork was analyzed using multiple techniques. We organized documentary research into a chronological timeline outlining the evolution of the environmental and development agenda in Calakmul. We transcribed the survey data into a database and analyzed it primarily using descriptive statistical analyses. Measures of central tendency were applied to summarize key variables.

For the qualitative data, we transcribed interviews, field notes, and diary entries. We then coded the data in Atlas.Ti 25 software using inductive coding. Although the analysis was guided by a set of predefined qualitative categories, this allowed us to identify central narratives that complement and contextualize the survey findings. For example, the category “access to water”, which explores the availability, infrastructure, and quality of water, generated codes such as insufficient infrastructure, pumping problem or dependence on water trucks.

Nevertheless, establishing direct causal relationships regarding water scarcity in Calakmul is methodologically constrained, as the factors involved are deeply interrelated and operate across multiple spatial and temporal scales. Hydrogeological conditions, regulatory frameworks, and institutional capacities mutually shape one another, generating cumulative and path-dependent processes such as historical planning decisions and the gradual deterioration of infrastructure. Accordingly, this study does not advance a linear causal explanation; instead, it documents the extent and spatial distribution of water supply disruptions and examines the interplay of ecological, regulatory, and institutional factors that produce unequal access to water. This analytical boundary is made explicit to avoid causal claims that exceed the scope and design of the study.

3. Results

The results are divided into three sections. Section 3.1 and Section 3.2 provide a historical overview based on a literature review, while the last section (Section 3.3) is based on information gathered during fieldwork.

3.1. Navigating Tensions Between Conservation and Development in the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve

The 1970s marked the rise of Biosphere Reserves, signaling a turning point in global conservation thinking. The launch of UNESCO’s “Man and the Biosphere” Program in 1971 embodied a paradigm shift toward an integrated approach that unites science, education, and local community participation, departing from the earlier protectionist model of national parks [20]. Increasing criticism, particularly from Indigenous and peasant movements, of national parks’ exclusionary practices spurred conservation debates to consider local contexts and to challenge the displacement of communities in the name of conservation. By the 1980s, these ideas entered national policy arenas, coinciding with the framework of the Man and the Biosphere Program proposed by UNESCO, and the first models of Biosphere Reserves were adopted, involving both scientists and local populations, shaping what became known as the “Mexican model” promoted by Gonzalo Halffter and Julia Carabias, two national and global leaders in conservation policy [17,18]. At the same time, national policies pushed agricultural frontiers deeper into the humid tropics, creating lasting tensions between conservation and development—tensions that are clearly illustrated in the case of Calakmul [31,69,81].

Beginning in the 1970s and intensifying in the 1980s, the Calakmul region experienced substantial population growth driven both by a government-sponsored colonization program promoting the relocation of rural populations from land-scarce areas and by untargeted migration to the tropical forests of southeastern Mexico. Motivated by the promise of land, the incoming population was highly heterogeneous: migrants came from 23 states and included Indigenous peoples such as Yucatec Maya, Ch’ol, Tzeltal, and Tzotzil [82]. The area was soon settled by small, campesino (peasant) communities who rebuilt their livelihoods from the ground up. At the same time, a conservation-research project began to take shape within government spheres, spearheaded by archaeologist William Folan. This initiative culminated in 1989 with the official designation of the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve [83].

When the CBR was established, 40% of its 723,185 hectares were designated as the core zone and the remaining 60% as a buffer zone. Its creation was driven by academics and government officials, and established by presidential decree in 1989, without consulting local communities. This omission triggered conflicts, particularly with those settled within the core zone, where activities were now heavily restricted [82]. The clash between conservation objectives and rural development needs was stark. On one side were recently settled communities striving to establish territorial rights through agricultural and livestock practices; on the other, a conservation model that severely limited such activities [31].

Despite these tensions, the consolidation of the CBR advanced throughout the 1990s. In 1993, the reserve was admitted to UNESCO’s Man and the Biosphere Program and established a Consultative Council composed of different sectors involved in local resource use, development, and conservation [84]. Some of these stakeholders had been conducting long-term ecological and archaeological research in the region (e.g., The Nature Conservancy, World Wildlife Fund, and the Autonomous University of Campeche) [83]. A decade after its decree, the CBR was admitted to Mexico’s National System of NPAs in recognition of its contribution to national biodiversity conservation [85]. In 2000, the National Institute of Ecology developed the management plan in collaboration with the different sectors involved in the area and community representatives. This plan replaced the 1992 preliminary plan and consists of eight components, including one on conservation and one on social development, which has a specific section on strategies and actions to improve communities’ access to water [74].

Eight years after the establishment of the biosphere reserve, when State-sponsored community programs in the region began to decline, the CBR and its buffer zone were incorporated into Mexico’s “first ecological municipality” [21] (p. 6). Calakmul was declared a municipality in December 1996 and the decree came into effect on 1 January 1997 [60]. Since then, basic infrastructure such as roads, street lighting, and aqueducts has been constructed to improve local conditions. As mentioned in Article 115, section III of the Mexican Constitution, municipalities are responsible for public services such as drinking water, drainage, sewerage, wastewater treatment and disposal, street lighting, cleaning, waste collection, transport, and final disposal, among others [86]. In 1998, the territory of Calakmul was reorganized due to the creation of the municipality of Candelaria [60], and the first underground aqueduct was built to supply water from Laguna de Alvarado (near the community 16 de Septiembre) to Xpujil (municipal capital), supplying the communities along the route [87]. Around the same time (1995–97), many communities gained ejido status as part of the rural development agenda, for example, Nuevo Becal in 1995, Centauro del Norte, Nuevo Conhuas, Valentin Gómez Farías, and Manuel Crescencio Rejon in 1996, and La Lucha I in 1997 [78]. This allowed communities to access government agricultural subsidies (e.g., PROCAMPO) and conservation programs (e.g., PROREST), which became important sources of household incomes.

By the early 21st century, the CBR was firmly established and began receiving national and international recognition. In 2002, UNESCO declared the site a World Cultural Heritage Site. The conservation agenda evolved from focusing on protection and development to focusing on connectivity and shared governance [88]. During this period, it became part of the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor Project, which connected Calakmul with the Sian Ka’an Biosphere Reserve to support wildlife movement [89]. In 2006, the MAB-designated area expanded to 1.4 million hectares, integrating the CBR with Balam Kú, Balam Ki, and the Bala’an Ka’ax protected areas, forming the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve Region. In 2014, UNESCO reclassified the site as a Mixed World Heritage Site [90]. By then, multiple actors—including academics, government agencies, NGOs, and local communities—were actively involved in research (e.g., INECOL, ECOSUR, INAH, local universities, WWF, Pronatura), promotion (INAH, CONANP, SEMARNAT, Ministry of Culture), and local development projects (e.g., Xpujil Regional Council, local tourism enterprises) [64].

In the past decade, the conservation agenda has increasingly embraced inclusive approaches, integrating local actors into land management. Conservation actors have also employed restorative approaches to reverse the environmental impacts of deforestation around the CBR. Some communities began participating in the REDD+ program and, with support from CONANP, 18 communities obtained certification as Voluntarily Designated Conservation Areas. The original core zone of the reserve has expanded from 40% to 99% of the CBR’s total area, and the adjacent state reserves have been reclassified: Balam Kú as a Biosphere Reserve and Balam Kin as a Flora and Fauna Protection Area [91]. The Mexican government now proudly refers to it as “El Gran Calakmul” (The Great Calakmul) and seeks to extend the conservation area into Guatemala and Belize. Very recently, the three governments signed the Declaration of Calakmul: Corredor Biocultural Gran Selva Maya to protect 5.7 million hectares [92]. In the 36 years since the creation of the CBR, remarkable progress has been made on the conservation agenda in Calakmul, earning it global recognition and national acclaim (Table 2).

Table 2.

Emergence and chronological evolution of the environmental and municipality development (with a focus on water availability) agenda around the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve.

3.2. The Challenge of Access to Water in a Promised Land

In contrast to conservation efforts, social development has lagged behind and local communities continue to face significant unmet needs. According to the latest annual report on poverty and social backwardness, only 35.2% of the municipality’s population has access to nutritious, quality food, and only 22.5% has access to health services [93]. Xpujil, the municipal seat and largest population center, still lacks many essential services. Residents often travel to nearby cities like Chetumal or Escarcega, a two-hour drive, to access healthcare, banking, or hard-to-find goods (e.g., specialized medicines, medical and technological equipment). Although infrastructure has improved, including roads and public transportation, it remains insufficient.

Water access remains a pressing challenge. The decentralization of water and sanitation services in 1983, which transferred responsibilities to states and municipalities, created financial burdens [94]. Municipalities like Calakmul, marked by poverty and low revenue-generating capacity, lack sufficient resources to meet the population’s needs. Although two additional aqueducts were built in 2005 (Santa Rosa–16 de Septiembre and López Mateos–Xpujil), and improved access to water in some areas, maintaining the infrastructure has proven economically and administratively difficult [95]. According to a comparison of municipal planning carried out for the annual report on poverty and social backwardness 2025, water investment in Calakmul over the last three years, made with resources from the Fund for Municipal Social Infrastructure and Territorial Demarcations of the Federal District, has been USD 1.4 million in 2022, USD 0.88 million in 2023, and USD 0.45 million in 2024 [93].

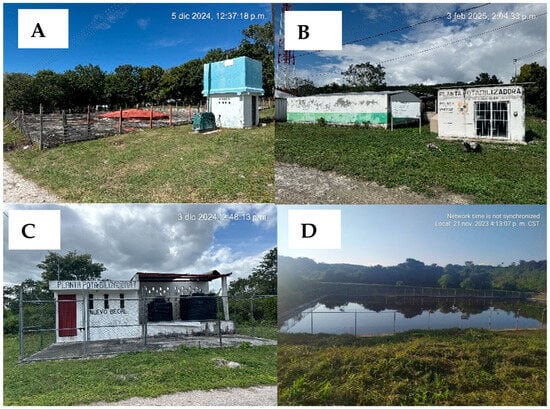

This narrative, supported by documentary research and fieldwork, illustrates that water scarcity remains a persistent and well-known challenge in the region, and despite a development agenda committed to improving living conditions, progress has been limited over the past 36 years. When settlers first arrived in the region, water access was extremely precarious. There was no water infrastructure, and households were entirely dependent on whatever rainwater they could capture, and the few natural surface water bodies scattered throughout the area (see Figure 1). Over time, the gradual construction of water infrastructure has improved access to some extent. Most notably, communities now have large rainwater-harvesting systems—such as 200,000-L cisterns (aljibes) intended for domestic use, and pond liners originally designed for agricultural purposes but now also used to supply households (Figure 3). However, these improvements have required persistent pressure from communities and often the involvement of non-governmental actors.

Figure 3.

Community infrastructure for water access in the study localities in the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve. (A) Community cistern in Nuevo Becal (subterranean aljibe), (B) Community cistern (surface aljibe) and water treatment plant in M. Crescencio Rejon, (C) Water treatment plant in Nuevo Becal, (D) Pond Liner in Dos Lagunas Norte.

The semi-structured interviews and surveys further revealed the lived experience of local communities. The process of community advocacy is illustrated in the following quote by a middle-aged male who was part of Xpujil Regional Indigenous and Popular Council (CRIPX)1 and has lived for 23 years in the region:

“I arrived in Xpujil around 2002, and the water we used came from jagüeyes—it had a horrible smell. The water we were given had tadpoles in it. (…) We had to treat it with chlorine so the sediment would settle at the bottom. Conditions were critical. In the municipal seat, we were allocated 200 L per week. (…) Back then, at CRIPX, our main social struggle was water. We used to submit formal requests whenever a new municipal administration began. There were no cisterns, only rudimentary water tanks. Around 2005–2006, the first 25,000–30,000-L cisterns appeared, led by the Presbyterian church—foreign churches—but they only gave them to their members. (…) Later, a foundation called SANUT arrived, and a year after that, Fondo para la Paz came in—this was around 2007–2008. That’s when the local government and the reserve also started to get involved. Cistern construction began, and our social struggle was legitimate, supported by all sectors of the community. It gave us a reason to come together, and people became more organized, more determined. Eventually, cisterns became more common. (…) Then came the aqueduct in 2009, and that truly gave us a breather in Xpujil—a huge relief. We finally had two aqueducts. But politicians think that building aqueducts is the solution. They don’t consider all the other factors involved in making one operational.” (N.J., CRIPX Key informant, 4 March 2024)

This testimony highlights both the chronic vulnerability and the agency of the population in demanding access to water—a basic yet unmet right. It also reveals the complex interplay between NGOs and government actors in addressing water insecurity. While infrastructure projects like aqueducts have provided partial relief, the broader challenges of maintenance, management, and institutional coordination remain unresolved. These systemic issues contribute to a persistent sense of water insecurity. The creation of inter-institutional working groups in the state congress in 2025 to investigate water scarcity, despite the re-inauguration of the Lopez Mateos–Xpujil aqueduct in 2024 (the first Lopez Mateos–Xpujil aqueduct was inaugurated in 2005), illustrates how little progress has been made in resolving the region’s water crisis [96,97,98,99]. A comparative summary of the main conservation and development initiatives—specifically access to water—carried out in Calakmul (Table 2) shows the lack of continuity and lag in social welfare efforts compared to conservation efforts in the area.

3.3. Water Insecurity Among Households in Calakmul

The construction of aqueducts, water distribution networks, community water tanks (aljibes), and household cisterns has undoubtedly improved access to water in the region. However, the pace of progress under the development agenda remains very slow, so that local populations continue to experience significant water vulnerability. Our survey data on household water vulnerability in the region show that, of 200 surveyed households, 136 (68%) have experienced prolonged periods without access to water in the last five years (Table 3). In three of the surveyed communities (Nuevo Becal, Valentin Gomez Farias, Nuevo Conhuas), the impact was particularly high: more than 80% of households reported having run out of water at least once in the past five years. Furthermore, in the communities studied, more than 80% of households (172 in total) reported that their community had experienced interruptions in water supply at some point (Table 3).

Table 3.

Water vulnerability of households studied by the community in the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve (last 5 years).

The average number of consecutive days that households went without water across all communities is 32.5—an alarming figure. In two communities (Nuevo Conhuas y Manuel Crescencio Rejon), this number exceeded 50 days, while only one community (Nuevo Becal) reported an average of 12 days without water—still a considerable amount of time to go without water. These findings suggest that, even though most communities in the region have a water supply network, households still face the risk of going without water for periods ranging from a single day to as long as a year.

Connection to piped water does not necessarily ensure water access. Our surveys showed that in three of the surveyed communities (Zoh-Laguna, Manuel Crescencio Rejon, Nuevo Conhuas), over 90% of households are connected to the piped water network; in another three (Valentin Gomez Farias La Lucha I), more than 50% are connected; and in two (Nuevo Becal; La Lucha II), no households have any access at all to piped water (Table 3). Moreover, surveys and interviews indicated that the reality is even more complicated. Seven communities have a piped water network, but it is only functional in four communities (Zoh-Laguna, Manuel Crescencio Rejon, Nuevo Conhuas, and Lucha I) and in one, it was not yet operational at the beginning of 2025 (Centauro del Norte) (Table A1). In one of the communities where the piped water network exists but does not work, households mentioned that the water network stopped working more than five years ago and has not been repaired. Such situations are common among public infrastructure projects, many of which are constructed but which lack adequate maintenance to ensure their long-term operation. For example, the following quote from the representative of a civil association established in Calakmul points to the lack of maintenance:

“I also interacted with civil society, meeting families, and sometimes the communities complained. They told us, “The projects were the same as always.” The projects are built, but there is no process to involve them in training and maintenance. So [the cisterns] already have cracks and fissures due to lack of maintenance, and there you have a white elephant that is no longer functioning. So, between having to renovate or restore them, it will also require an investment. It is a very heavy investment” (J.R. NGO Key Informant, 22 February 2024).

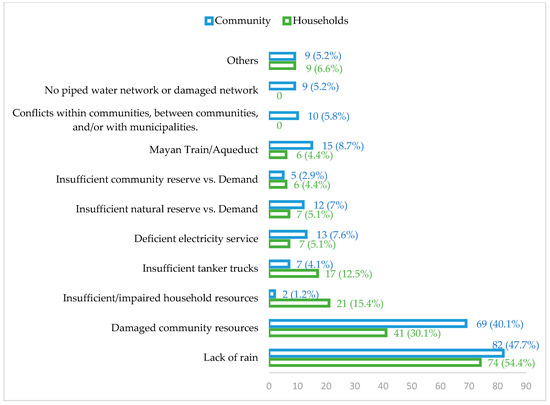

Thus, even among households with piped water connections, dependence on rainwater collection persists—just as it did when the region was settled in the 70’s. Our data indicate that over 90% of 200 surveyed households (185 households) continue to rely on rainwater as part of their water supply strategy (Table 3). In fact, in communities where the piped water network is either barely functional or non-functional, 100% of households rely on rainwater. Rainwater remains the most valued and relied-upon water source in Calakmul, playing a central role for water supply. Unlike in the early years of settlement, infrastructure now facilitates access not only to rainwater but also to groundwater. Community cisterns and pond liners have been built across most localities, and some comm-unities—such as Zoh Laguna and Manuel Crescencio Rejon—have wells that distribute water through local networks. Despite these improvements, households remain vulnerable to water scarcity and tend to attribute this vulnerability primarily to immediate, short-term causes rather than to underlying structural problems related to social injustice—issues that Mexico’s development agenda has failed to adequately address. For example, among the 136 households (68%) that had previously experienced water shortages, the most frequently cited reason was lack of rainfall, a predictable finding given the central role of rainwater in the local water system (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Causes of water shortages in a household and community level identified by surveyed households in the municipality of Calakmul.

Most of the remaining causes of water shortage point to infrastructure problems, deficiencies in public services, and resource constraints—factors that fall under the responsibility of the three levels of government and reflect deeper structural issues. These causes include damaged communal infrastructure (potable water networks, deep-well extraction equipment, community cisterns), insufficient municipal water delivery (such as tanker trucks), limited communal water reserves relative to demand, and unreliable electricity service. Large-scale construction projects, such as the Tren Maya2 and the renovation of the regional aqueduct, were also cited as sources of disruption. Altogether, these problems account for 77 responses (56.6%) among the 136 households that had experienced water shortages, exceeding those who blamed lack of rainfall (74 households, 54.4%). The contrast is even stronger at the community level. Among the 172 households reporting that their community had run out of water, 82 (47.7%) identified lack of rainfall as the main cause, whereas 118 (68.6%) attributed it to deficiencies in public services.

Only 21 (15.4%) respondents attributed their vulnerability to household-level factors, such as insufficient or damaged storage infrastructure (e.g., private cisterns), lack of labor capacity to collect or transport water, or financial limitations that prevent purchasing water from tanker trucks.

Our findings indicate that both national and international non-governmental actors play an important role in enhancing household water security. While some households can afford to purchase smaller water storage containers, most of the 10,000-L (or larger) tanks have been acquired through government programs or with support from non-governmental organizations such as Fondo para la Paz and Haciendas del Mundo Maya. Projects implemented by these non-governmental actors extend beyond material support. This is illustrated by the following testimony from a representative of a non-governmental organization who has been working in the region for more than 15 years, collaborating with local communities to develop long-term solutions to the main barriers to sustainable development:

“Well, the truth is that a lot of progress has been made. For example, in addition to drawing up this work plan, the water committees now have a kit that they use to monitor the quality of different water sources in their community. They carry out the monitoring, collect the data, and interpret it, because they are also taught how to interpret it, of course. They present the results to their assemblies or to their [community] authorities to see what needs to be done to improve water quality. They have been given certain tools so that, for example, if a valve breaks in the community, they don’t have to wait for the municipality to come and replace it. They have the knowledge, and many communities already have the resources. In addition, income-generating projects have been achieved. There are communities that are currently managing a community water purification plant, and a percentage of all the resources obtained from that plant is allocated exclusively to water and sanitation issues. In other words, it is a process that has been going on for 10 years” (M. NGO Key Informant, 21 February 2024).

Water storage containers represent a physical capital that enables households to secure their water supply (Figure 5). Households basically receive two types of support: water storage tanks with a capacity greater than 5000 L, and deliveries of water during the dry season. Storage tanks are the most appreciated, as they allow households to store enough water to meet their needs for several weeks—some even manage to cover the entire dry season. The delivery of half a water truckload (approximately 5000 L) during the dry season is part of the municipal emergency plan. However, as shown in Figure 3, one of the main causes of water scarcity cited by respondents is the insufficient number of municipal water trucks to meet the high demand during the critical dry season. This shortage results in long waiting times for water deliveries, even for households that can afford to pay for additional truckloads. As shown in Table 1, over 70% of households surveyed (200 N) have received aid from cisterns and/or water delivery, primarily from the municipal government.

Figure 5.

The most common types of water storage containers used in households in the Calakmul Municipality. (A) 5000 L (approx.) ferrocement cistern, (B) 10,000 L plastic cistern, (C) 2500 L (approx.) plastic cistern, (D) 5000 L plastic cistern, (E) 10,000 L ferrocement cistern.

4. Discussion

The findings suggest that social welfare in Calakmul has progressed more slowly than environmental conservation efforts. Despite the discourse of sustainable development framing the region, conditions of poverty and inequality persist, as evidenced by the lack of continuous access to water. More than thirty years after repopulation, many households still depend on rainwater harvesting. Of the 200 households analyzed, 68% reported interruptions in piped water supply, averaging approximately 32 days, primarily attributable to infrastructure deficiencies and institutional constraints. This highlights structural failures in governance. Furthermore, government support mechanisms primarily focus on providing physical capital, such as storage containers, and activating municipal emergency plans during the dry season. These measures are insufficient in the face of persistent structural problems. In this context, non-governmental actors are playing an increasingly important role in providing solutions and strengthening household water security, revealing a fragmented water governance system.

The difficulty in reconciling conservation and development objectives in environmentally strategic regions stems partly from an institutional model that prioritizes ecosystem protection over the long-term construction of social welfare [14,100]. Although the sustainable development framework proposes interdependences and synergism of conservation and development, in practice, they are often led by different institutions or departments and through different policies, which can cause challenges in their implementation [34,101]. Ecological conservation is a political act, shaped by competing ways of understanding nature, by power asymmetries and by the social and political consequences of environmental decisions [50]. Durand [28] refers to these dynamics as “unequal natures,” which hinder the integration of conservation and development goals. A key element in understanding this paradox is the differentiation of administrative responsibilities: environmental governance often lies primarily with the federal government, aligned with international agendas, whereas social welfare can be the responsibility of municipal authorities. This institutional divide helps explain the persistent gap between the two agendas in this case study: robust federal-international financing and lobbying on one side, and limited municipal capacities and resources on the other. The resulting asymmetry in goals and power relations produces territories where nature is effectively protected but local living conditions lag behind, reinforcing structural inequalities precisely in places promoted as sustainability models. As Adams and Hutton [50] note, the benefits of conservation are unevenly distributed, with local communities bearing many of the costs, including restricted access to land and resources.

The case of Calakmul clearly illustrates this paradox. Since its designation as a Biosphere Reserve (1989) and later as the first ecological municipality in the region (1997), conservation commitments have been formalized to improve the quality of life of residents through coordinated actions among the three levels of government involved with the CBR [74]. Yet, while conservation advanced with strong federal and international support, social development did not keep pace. Recent indicators of health, nutrition, basic services, and mobility presented by the Government of Mexico [93] reveal a persistent gap. This pattern is not unique to Calakmul. In other protected areas in Mexico, such as the Nevado de Toluca Flora and Fauna Protection Area, and many others, conservation policies have been implemented through centralized approaches that usually exclude local communities from decision-making, thereby limiting progress in social development [51,102]. Moreover, centralized federal management of many protected areas (e.g., Biosphere Reserves, Flora and Fauna Protection Areas, National Parks) ensures administrative continuity, in contrast to municipal planning cycles, which span only three years. With decentralization, additional responsibilities were transferred to municipalities without the corresponding resources, further constraining their ability to address social needs [103,104].

The paradox of unsustainability through failure of mutual conservation and human development is evident in water access for human consumption. Since the municipality of Calakmul was created, institutional discourse through municipal development plans and the CBR management program has been committed to improving access to water, which is essential to ensuring the well-being of the population [74,90,105]. Despite the formal existence now of limited infrastructure, most households continue to depend on rainwater, just as they did when they arrived in the region, and they experience interruptions in supply that can last for weeks or even months. This gap between the institutional promise of reliable service and its actual operation generates a persistent feeling of frustration and mistrust, as families once again assume responsibilities that were supposed to be covered by the public system.

In this context, water vulnerability among the population of Calakmul is clearly not only the result of diminishing rainfall, but also of long-term structural failures, which have a greater impact on supply interruptions than climatic factors themselves. For example, institutional barriers, administrative shortcomings, and limited technical capacity were identified by Almendarez-Hernández et al. [106] as obstacles across federal, state, and municipal levels. They exacerbate water challenges in Calakmul and throughout Mexico, including overexploitation, pollution, and inadequate infrastructure maintenance. At the same time, the most effective local solutions, such as household and community storage tanks, offer only temporary relief and ultimately shift the cost and responsibility for water security onto the most vulnerable populations, thereby perpetuating social inequality [44]. Ultimately, the water issue in Calakmul demonstrates that sustainability promoted through conservation alone has not translated into water justice or secure access to basic rights. The result is an incomplete model of “sustainable development”, clearly focused on the environmental sphere and with many challenges in the social, economic, and political arenas.

This study also demonstrates the complexity of development rights and responsibilities. Many of the communities were encouraged by the government to settle in the region only in recent decades, despite the well-known limitations in water availability. Hence, whilst it is a basic human right to have access to water, there is a challenge when responsibilities change or are unclear. In the case of CBR, the national government encouraged settlement, but the local government is now responsible for water availability. NGOs have assisted in the implementation of water rights and communities are taking some measures themselves. This shared responsibility creates confusion and contributes to development inertia against the clear responsibilities of conservation agencies.

Discrepancies between conservation objectives and human well-being have been documented across multiple international contexts within NPAs. For instance, Romangy et al. [107], drawing on a comparative analysis of several Biosphere Reserves in the Mediterranean region, highlight the difficulties these conservation designations face in translating the Sustainable Development Goals—including water security—into effective local implementation. These challenges stem from the fact that populations coexisting within biodiversity-rich NPAs are often socially stratified, with large segments experiencing structural vulnerability, while simultaneously inhabiting ecologically fragile territories shaped by historical resource overexploitation and increasingly exposed to biophysical variability associated with climate change. From a complementary water governance perspective, González et al. [108] examine a set of case studies—primarily in Global South contexts—where water resource management, including local access to water, is undermined by competing pressures from economic sectors operating within or adjacent to NPAs, such as urban expansion, intensive agriculture, mining, and tourism. Their analysis underscores the technical, institutional, and governance constraints that hinder the implementation of integrated, watershed-based water planning approaches grounded in multi-level coordination and principles of environmental justice. Taken together, these studies—spanning cases in both the Global North and Global South—demonstrate that efforts to reconcile biodiversity conservation with human well-being in NPAs through sustainable development frameworks are profoundly complicated by intersecting factors, including social polarization, inadequate comprehensive planning, environmental fragility, sectoral pressures, and deficiencies in institutional capacity and governance arrangements. Consistent with these findings, our analysis of the CBR reveals that water-related vulnerability among local populations arises from multiple, interrelated drivers, including the degradation of regional water resources, chronic underinvestment in public service infrastructure, weak governance mechanisms, and an uneven policy trajectory in which a robust conservation agenda has advanced more rapidly than initiatives addressing basic human well-being. To advance toward a water-justice approach that complements—rather than competes with — environmental conservation, we must shift from a needs-based framework to a rights-based, governance-centered one [50,51,109]. This involves recognizing water simultaneously as a social right and ecological good, ensuring equitable access, and protecting water sources. In Mexico, organizations such as Coalition of Mexican Organizations for the Right to Water, as well as initiatives promoted in the Forums for the General Water Law— spaces created to gather citizen and community proposals for a new legal framework— have emphasized the value of participatory councils, community assessments, and other deliberative mechanisms as key tools for harmonizing federal environmental goals with local water welfare. Latin American experiences also demonstrate that strengthening community water systems, such as the Juntas de Agua in Ecuador and Bolivia [110,111], can establish hybrid governance structures in which the state provides technical support and regulatory oversight, and local users manage distribution, maintenance and conflict resolution. Boelens and Seemann [112] discuss the intricate relationship between formal and alternative “water securities” and the cultural politics of rights recognition. These models demonstrate that aligning conservation and justice requires infrastructure, shared decision-making power, transparency, and long-term institutional support.

5. Conclusions

Calakmul reveals a persistent and deeply rooted paradox: an area that is internationally celebrated for its ecological importance yet characterized by chronic social vulnerability. This is particularly evident in terms of the rural population’s access to safe water supplies. Despite three decades of conservation initiatives and official declarations of intent to combine environmental protection with improved living conditions, the region continues to suffer from severe structural deficits in the areas of water supply security, basic services, and public investment. Our findings show that although rainwater harvesting systems and infrastructure projects have provided some relief in recent years, many households still must cope with prolonged periods without water. This is often less due to lower and irregular rainfall than to administrative failures, inadequate public services, and limited technical capacities.

This study shows that the discrepancy between conservation and development agendas is not accidental but is rooted in institutional arrangements that assign environmental authority to the federal government, while social welfare is delegated to local governments with limited resources. The resulting asymmetry—in decision-making power, funding, and planning horizons—has led to “unequal natures” that protect biodiversity but leave communities behind. In this sense, water insecurity in Calakmul is an expression of structural inequality characterized by the privilege of ecological goals without sufficient consideration of the social conditions necessary for sustainable human well-being.

However, as with any case study, the findings are anchored to a specific geographical, institutional, and temporal context. This implies that some dynamics could vary in other municipalities or NPAs with different governance structures. Likewise, the work is based on the availability and quality of administrative and interview data, which may limit the generalization of certain patterns. Nevertheless, as other studies show [113,114,115], these limitations emphasize the importance of continuing to investigate the relationship between conservation, social welfare, and water governance in other comparable territories. Future studies could also delve deeper into the coordination processes between federal, state, and municipal actors to identify the administrative bottlenecks that limit water supply, thereby broadening our understanding of the mechanisms that sustain the gap between environmental and social agendas.

To bridge this gap, we propose that water policy must be rethought in the future, considering equality and taking a biocultural approach, recognizing local knowledge, strengthening community capacities, and ensuring investment in water infrastructure. Ensuring water justice in Calakmul depends on placing communities at the center of policy design and implementation, while balancing conservation commitments with long-term social development strategies. Only by addressing these intertwined challenges can NPAs fulfill their dual mission of conserving nature and improving the lives of the people who inhabit and manage biodiverse landscapes. Further questions that need to be considered include the extent to which placing communities at the center of socioenvironmental governance can achieve water justice or to which additional resources and innovative technologies are required. Finally, traditional technologies and local solutions may facilitate water justice if enabled and supported within integrated knowledge exchange and multi-level decision making systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land15010124/s1, Survey S1: Water situation in the Calakmul region, Mexico; Letter of Opinion S1: Outcome from the ethics committee.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.C.-M., T.R.-N., and B.S.; methodology, G.C.-M., B.S., S.C., D.O.M.-R. and R.M.W.; formal analysis, G.C.-M., T.R.-N. and B.S.; investigation, G.C.-M.; resources, B.S. and S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, G.C.-M. and T.R.-N.; writing—review and editing, G.C.-M., T.R.-N., B.S., S.C., D.O.M.-R. and R.M.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Author G.C-M. was supported by a fellowship from the Secretariat of Science, Humanities, Technology, and Innovation (SECIHTI), fellowship number CVU 737963 (PhD. Scholarship).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (Project identification code CEI/2023/4052/05) on 23 October 2023. It was a non-interventional study, using surveys and interviews, and all participants were fully informed that their anonymity would be guaranteed, why the research was being conducted, how their data would be used, and whether participation carried any risks, as outlined in Section 2.2 of this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to ethical, legal, and institutional restrictions, as the information was collected under informed consent and in compliance with ECOSUR’s internal research ethics and data management regulations.

Acknowledgments

Xhunaxhi Jiménez-Jiménez is thanked for her support during fieldwork and administrative tasks. Karina Chale-Silveira is thanked for her technical support in creating the map. The authors who prepared the original draft are native Spanish speakers. To facilitate collaboration, artificial intelligence (AI) translation tools (DeepL desktop version 25.12.1.19303+a07d1aa03cecbaf3510e79ba54a594de1d12c757) were used in the early drafts of the manuscript. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CBR | Calakmul Biosphere Reserve |

| NPA | Natural Protected Area |

| MAB | Man and the Biosphere Program |

| SDGs | UN Sustainable Development Goals |

| NGO | Non-governmental organization |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| AD | Years after Christ |

| CONANP | National Commission for Protected Natural Areas |

| INAH | National Institute of Anthropology and History |

| PROCAMPO | Direct Support Program for Rural Areas |

| PROREST | Program for the Protection and Restoration of Priority Ecosystems and Species |

| INECOL | Ecology Institute, A. C. |

| ECOSUR | The College of the Southern Border |

| WWF | World Wildlife Fund Inc |

| SEMARNAT | Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources |

| REDD+ | Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation Program |

| ADVC | Area Voluntarily Designated for Conservation |

| PROAGUA | Drinking Water, Drainage, and Treatment Program |

| CRIPX | Xpujil Regional Indigenous and Popular Council |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Water sources, infrastructure, and support by the community.

Table A1.

Water sources, infrastructure, and support by the community.

| Locality | Community Description of Water | Households Have Received Water Support (%, n) |

|---|---|---|

| Zoh-Laguna (Ejido Alvaro Obregón) | There is a piped water network, and the water distributed comes from a well in the community. There are areas of the community where households receive water seven days a week. Of the households surveyed, 95.4% receive piped water. There is a lagoon, and previously, the water distributed in the network came from it. Of the households surveyed, 86.2% mentioned that they use rainwater (65 N). | 63.1 (65 n) |

| Manuel Crescencio Rejon | There is a piped water network, and the water distributed comes from a well in the community. Households receive water two days a week. Of the households surveyed, 100% receive piped water. In addition, there is a community cistern (aljibe) and a water treatment plant in the community for community use. Of the households surveyed, 82.4% mentioned that they use rainwater (17 N). | 82.4 (17 n) |

| Nuevo Conhuas | There is a piped water network, and the water distributed comes from the Lopez Mateos–Xpujil aqueduct. Households receive water 1 or 2 days a week. Of the households surveyed, 97% receive piped water. In addition, there is a community cistern (aljibe) in the community, and they have their own water truck. Of the households surveyed, 90.9% mentioned that they use rainwater (33 N). | 78.8 (33 n) |

| Centauro del Norte | There is a piped water network, which was installed at the end of 2024. At the time of the surveys in January 2025, the water network was not yet operational. The water to be distributed will come from the Lopez Mateos–Xpujil aqueduct. Of the households surveyed, 53.3% reported being connected to the piped water network. In addition, there is a community cistern (aljibe), a pond liner, and a lagoon in the community. Of the households surveyed, 100% reported using rainwater (15 N). | 86.7 (15 n) |

| Lucha I | There is a piped water network, and the water distributed comes from the Lopez Mateos–Xpujil aqueduct. Households reported receiving water once a year, and only 64.7% reported receiving piped water. In addition, there are 2 community cisterns (aljibes) and a pond liner in the community. Of the households surveyed, 100% mentioned that they use rainwater (17 N). | 70.6 (17 n) |

| Valentin Gomez Faras | There is a piped water network, which was modernized at the end of 2023. The water distributed comes from the Lopez Mateos–Xpujil aqueduct, but according to the households surveyed, since the water network was reopened, it has not been working, and they have not been receiving water. Of the households surveyed, 61.9% reported being connected to the piped water network. In addition, there are two community cisterns (aljibes), a jagüey, and a pond liner in the community. Of the households surveyed, 100% reported using rainwater (21 N). | 81 (21 n) |

| Lucha II | There is no piped water network. According to the households surveyed, they receive water by water truck every month. There is a community cistern (not working) and a pond liner in the community. Of the households surveyed, 100% mentioned that they use rainwater (9 N). | 88.9 (9 n) |

| Nuevo Becal | There is a piped water network, but it does not work. There are two community cisterns (aljibes) and a lagoon in the community. Of the households surveyed, 100% mentioned that they use rainwater (23 N). | 65.2 (23 n) |

| General | 7 of 8 communities surveyed have a piped water network, but it only works in 4 communities. 2 communities have their own wells and the others receive water from the Lopez Mateos–Xpujil aqueduct. The community that does not have a piped water network receives water by tanker truck every month. Of the households surveyed, 71.5% receive piped water and 92.5% use rainwater (200 N). | 73 (200 N) |

Notes

| 1 | CRIPX is an intercultural organization with a gender focus that fights for participatory democracy, autonomy, and comprehensive management of natural resources, as well as the management and execution of comprehensive projects for the well-being of the inhabitants of the Calakmul region through the revaluation and strengthening of local capacities and knowledge [96]. |

| 2 | The Tren Maya is one of the megaprojects carried out during the administration of former President Lopez Obrador (2018–2024). It is a railway project covering five states in southeastern Mexico (Chiapas, Tabasco, Campeche, Yucatan, and Quintana Roo), which was inaugurated in 2024. According to the Mexican government, it is a project to promote the social, cultural, and economic development of the Yucatan Peninsula. Among its objectives are to restore the biological connectivity of natural areas, promote the conservation of ecosystems and environmental services, and rehabilitate degraded ecosystems, especially in NPAs, for this reason, the integration of the Calakmul region into the project was of utmost importance [99]. |

References

- Loos, J. Reconciling Conservation and Development in Protected Areas of the Global South. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2021, 54, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusack, J.J.; Bradfer-Lawrence, T.; Baynham-Herd, Z.; Tickell, C.Y.; Duporge, I.; Hegre, H.; Moreno Zárate, L.; Naude, V.; Nijhawan, S.; Wilson, J.; et al. Measuring the Intensity of Conflicts in Conservation. Conserv. Lett. 2021, 14, e12783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaccaro, I.; Beltrán, O.; Paquet, P.A. Political Ecology and Conservation Policies: Some Theoretical Genealogies. J. Political Ecol. 2013, 20, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.J.; Roth, R.; Klain, S.C.; Chan, K.; Christie, P.; Clark, D.A.; Cullman, G.; Curran, D.; Durbin, T.J.; Epstein, G.; et al. Conservation Social Science: Understanding and Integrating Human Dimensions to Improve Conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 205, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbera, E.; Maestre-Andrés, S.; Collins, Y.A.; Buchi Mabele, M.; Brockington, D. Decolonizing Biodiversity Conservation. J. Political Ecol. 2024, 28, 889–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seixas, C.S.; Davy, B. Self-Organization in Integrated Conservation and Development Initiatives. Int. J. Commons 2008, 2, 99–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Blanc, D.; Roehrl, R.; Rits, J.; Jussila, R.; Plutakhina, M.; Zubcevic, I.; Soltau, F.; Martinho, M.; O’Connor, D. Global Sustainable Development Report 2015 (Advance Unedited Version) (GSDR 2015); UNDESA: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Raworth, K. Why It’s Time for Doughnut Economics. Progress. Rev. 2017, 24, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, E.A.C.; White, R.M. Education for Sustainable Development: Definitions, Debates and Design. In Perspectives and Practices of Education for Sustainable Development: A Critical Guide for Higuer Education; White, R.M., Kemp, S., Price, E.A.C., Longhurst, J.W.S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2025; pp. 9–35. ISBN 978-1-003-45156-3. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Resolution 70/1 Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, L.M.; Domingues, J.P.; Dima, A.M. Mapping the Sustainable Development Goals Relationships. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, C.; Warchold, A.; Pradhan, P. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Are We Successful in Turning Trade-Offs into Synergies? Palgrave Commun. 2019, 5, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, W.M.; Aveling, R.; Brockington, D.; Dickson, B.; Elliott, J.; Hutton, J.; Roe, D.; Vira, B.; Wolmer, W. Biodiversity Conservation and the Eradication of Poverty. Science 2004, 306, 1146–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, P.; Igoe, J.; Brockington, D. Parks and Peoples: The Social Impact of Protected Areas. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2006, 35, 251–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büscher, B.; Fletcher, R. The Conservation Revolution: Radical Ideas for Saving Nature Beyond the Anthropocene; Verso: London, UK, 2020; ISBN 978-1-78873-771-5. [Google Scholar]

- Halffter, G. Las Reservas de La Biosfera: Conservación de La Naturaleza Para El Hombre. Acta Zoológica Mex. 1984, 5, 4–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halffter, G. El Concepto de Reserva de La Biosfera. In Estudio Integrado de los Recursos Vegetación, Suelo y Agua en la Reserva de la Biosfera de Mapimí; Montaña, C., Ed.; Ambiente Natural y Humano; Instituto de Ecología, A.C.: Xalapa, Mexico, 1988; pp. 19–44. ISBN 968-7213-09-4. [Google Scholar]

- Halffter, G. Reserva de La Biosfera: Problemas y Oportunidades En México. Acta Zoológica Mex. 2011, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Coung, C.; Dart, P.; Hockings, M. Biosphere Reserves: Attributes for Success. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 188, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsdorf, A.; Araya Rosas, P. El modelo de Reservas de la Biosfera: Conceptos, características e importancia. In Reservas de la Biosfera de Chile: Laboratorios para la Sustentabilidad; Moreira-Muñoz, A., Borsdorf, A., Eds.; Geolibros; Academia de Ciencias Austriaca, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Instituto de Geografía: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2014; pp. 4–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bridgewater, P. The Man and Biosphere Programme of UNESCO: Rambunctious Child of the Sixties, but Was the Promise Fulfilled? Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2016, 19, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara, S.; Laborde, J. The Landscape Approach: Designing New Reserves for Protection of Biological and Cultural Diversity in Latin America. Environ. Ethics 2008, 30, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, L.; Figueroa, F.; Trench, T. Inclusion and Exclusion in Participation Strategies in the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve, Chiapas, Mexico. Conserv. Soc. 2014, 12, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, B.F.; Cevallos, J.; Santana, M.F.; Rosales, J.; Graf, M.S. Losing Knowledge about Plant Use in the Sierra de Manantlan Biosphere Reserve, Mexico. Econ. Bot. 2000, 54, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]