Abstract

Historical cropland reconstruction is crucial for modeling long-term agricultural dynamics and assessing their climatic and ecosystem impacts, while also providing critical regional benchmarks for improving global land-use datasets. This study presents a millennium-long reconstruction of cropland area at the provincial level for the Korean Peninsula by integrating multi-source historical cropland records, land surveys, and modern statistical and remote-sensing-based data. Then, a land suitability model for cultivation and a spatial allocation model were developed by incorporating topographic, climatic, and soil variables to generate 10 km resolution gridded cropland data over the past millennium. Our analysis revealed a long-term increasing trend in cropland area at the provincial level over the past millennium, with significant spatial and temporal variations. Spatially, cropland was primarily distributed in western coastal areas, with historical southward expansion. After the peninsula’s division, trends diverged, with continued growth in the north Korea but a decrease in the south Korea by 2000. The spatial allocation model validation results show strong spatial and quantitative agreement between the reconstructed historical cropland and the remote-sensing-based data, with 72.12% of grids differing by less than ±20%. This high consistency confirms the feasibility of the applied reconstruction method.

1. Introduction

Anthropogenic land use—including cultivation, deforestation, grazing, and urbanization—has transformed nearly half of the Earth’s natural vegetation into agricultural and urban landscapes [1,2,3,4]. These changes not only alter surface ecology and increase ecosystem vulnerability but also influence climate through biogeophysical feedbacks (e.g., albedo, roughness) and biogeochemical processes (e.g., carbon cycling) [5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. Research indicates that global cropland area has expanded from 0 Mha to approximately 16.4 Mha since 10,000 BCE, driven by factors including population growth, technological advancements, socioeconomic changes, and land-use policies [2]. This expansion has occurred primarily through the conversion of non-cropland areas, such as forests and grasslands. Such land cover transformations alter surface energy and water exchanges with the atmosphere, consequently influencing local to regional climate variables including temperature, humidity, precipitation, convection, and wind speed [3]. Furthermore, agricultural ecosystems are significant contributors to anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, accounting for roughly 50% of global methane (CH4) and 60% of global nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions [6]. To better understand the long-term spatiotemporal dynamics of land use and land cover change (LULCC) and their environmental impacts, international research programs such as LUCC, BIOME 300, Global Land Project, and LandCover6k emphasize the critical need to reconstruct historical LUCC changes. Such efforts are vital for understanding past human–environment interactions and providing baseline data for climate modeling [12].

Significant progress has been made in reconstructing historical LULCC, driven by international research initiatives. Notable global datasets have been developed, including: the HYDE dataset (Historical Database of the Global Environment) by the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency, covering the period from 10,000 BC to AD 2015 [13,14]; the SAGE cropland dataset (AD 1700–2007) from the University of Wisconsin’s Center for Sustainability and the Global Environment [15,16]; the PJ dataset (AD 800–1992) developed by Pongratz et al. [17] based on HYDE and SAGE; and the KK10 land cover reconstruction (8000 BP–AD 1850) by Kaplan et al. [18]. These datasets provide valuable methodological references and foundational data for analyzing long-term LUCC patterns and simulating climate–ecological interactions [19,20,21,22]. However, as their developers acknowledge, such global-scale products are primarily suitable for continental-to-global level analyses. Due to uncertainties in regional data sources, underlying assumptions, and reconstruction methodologies, they require local validation before being applied to regional-scale studies [15,23].

Uncertainties in global datasets arise from several methodological limitations. First, extrapolating trends from sparse historical cropland data often overlooks regional variations driven by diverse geographical conditions, social systems, and economic development patterns. Second, the estimated per capita cropland area—a key parameter in quantitative reconstructions—may not align with historical realities, directly affecting the reliability of the results. Third, modern cropland distribution data, which serve as the baseline for gridded reconstructions, are themselves uncertain. For example, spatial consistency among ten global cropland datasets derived from different remote sensing sources is only about 40% [24]. The selection of different baseline data can significantly influence the spatial allocation and suitability weights of historical cropland. Fourth, spatial modeling often fails to adequately account for pronounced regional differences in natural environmental factors or incorporate critical human influences—such as population distribution, modes of production, and agricultural technology—that strongly shape cropland dynamics [24].

Regional assessments have demonstrated that global datasets cannot accurately capture the spatiotemporal characteristics of land-use change in specific areas, such as China and Central/Northern Europe [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. In response, the PAGES LandCover6k initiative emphasizes the integration of regional historical documents and paleoenvironmental evidence to enhance LUCC reconstructions—particularly in typical regions (e.g., traditional farming areas and change hotspots) and during key historical transitions (e.g., AD 1000, 1500, and 1850) [33]. Such regionally grounded efforts are essential for providing reliable data for climate and ecological effect simulations and for improving the accuracy of global land-use products [34,35,36,37,38,39,40].

The Korean Peninsula represents a critical region for understanding long-term agricultural land-use changes in Northeast Asia, owing to its rich historical archives and documented history of agricultural development. However, current research has predominantly focused on the recent 50-year period, supported by modern remote sensing data [41,42,43,44], while the millennium-scale land-use history remains largely unexamined. Although global historical cropland datasets (e.g., HYDE and SAGE) [13,14,15,16] cover the Korean Peninsula, existing data still exhibit limitations at the regional scale, including relatively coarse spatial resolution (typically 0.5° × 0.5°), substantial uncertainties inherent to the reconstruction methods, and a lack of effective validation against regional historical records [24].

To address this gap, this study aims to reconstruct a provincial-level cropland area series for the Korean Peninsula spanning the past millennium, integrating historical documents, land surveys, and contemporary statistical sources. Building on this reconstructed series, we intend to develop a land suitability model for cultivation and a spatial allocation model that incorporate the key factors influencing cropland distribution, in order to generate a 10 km gridded cropland dataset. This study provides a high-resolution gridded dataset that (1) enables a detailed analysis of cropland spatiotemporal dynamics and serves as reliable historical land-use forcing data for regional-scale climate modeling, (2) establishes a validated regional benchmark to refine the accuracy of global land-use reconstructions, and (3) offers a methodological template for integrating historical archives with remote sensing data, applicable to other regions with rich historical documentation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

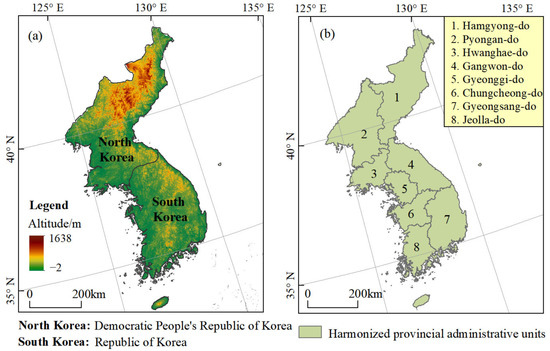

The Korean Peninsula is strategically situated in Northeast Asia, bordered by Russia and China to the north and northwest, and flanked by the Yellow Sea and the Sea of Japan. It spans latitudes 33–43° N and longitudes 125–131° E, encompassing the peninsula mainland and approximately 3300 smaller islands. The total land area is approximately 220,800 km2, of which the mainland accounts for about 97%. This study focuses on the mainland and Jeju Island. The mainland topography is characterized by higher elevations and extensive mountainous terrain in the north and east, contrasting with the hilly and coastal plains of the south and west (Figure 1a). The peninsula exhibits a humid to semi-humid monsoon climate, comprising both temperate and subtropical zones. Annual rainfall ranges from approximately 1300–1500 mm in the southern regions to 1000–1200 mm in the northern areas. Historical records on agriculture development indicate that agricultural reclamation initially focused on the fertile southern coastal plains. Over the centuries, driven by population growth and technological advances, land reclamation expanded in both intensity and scope, progressing from the plains into lower elevation mountainous areas and significantly transforming land cover [45,46].

Figure 1.

Map of the study area (a) and harmonized provincial administrative units (b).

Over the past millennium, the Korean Peninsula has experienced several major political–administrative transitions, including the Goryeo Dynasty (AD 918–1392), the Joseon Dynasty (AD 1392–1910), Japanese colonial era (AD 1910–1945), and the post-1945 division into North and South Korea. These shifts were accompanied by significant changes in administrative boundaries. During the Goryeo period, the territory was organized into ten provinces as of AD 995. In the Joseon era, a major reorganization in AD 1413 established eight provinces: Gyeonggi-do, Chungcheong-do, Gyeongsang-do, Jeolla-do, Hwanghae-do, Gangwon-do, Pyeongan-do, and Hamgyeong-do (Figure 1b). Under Japanese administration, the region was further subdivided into 13 provinces, with only three of the original eight retained intact; the remaining five were split into northern and southern sub-units (Bukdo and Namdo). Following Korea’s liberation in 1945, the peninsula was divided along the 38th parallel, resulting in the separation of three provinces—Hwanghae-do, Gyeonggi-do, and Gangwon-do—between North and South Korea. To maintain consistency and reduce uncertainty in data processing, this study adopts the eight provincial units of the Joseon Dynasty as the baseline spatial framework for cropland area reconstruction.

2.2. Data Sources

2.2.1. Cropland Data

The cropland data utilized in this study were sourced from three distinct periods, characterized by contrasting origins and preservation status: historical archives of the Goryeo and Joseon dynasties, land survey data from the Japanese colonial period, and modern statistical data. The properties and origins of these datasets are detailed below.

- (1)

- Historical cropland data for the Goryeo Dynasty was sourced from the History of Goryeo (《高麗史》) [46], while records for the Joseon Dynasty were compiled from official historical documents, including the Annals of King Sejong (《世宗實錄》) [47] and the Supplementary Literature Compilation (《增補文獻備考》) [48] (Table 1). Key benchmark years—1069, 1420, 1590, and 1634—were selected based on their origin in nationwide land surveys, making them reliable indicators of actual cropland extent for their respective periods. Spatially, the data exhibit a distinct hierarchical structure: Goryeo-era records provide national-scale aggregates, whereas Joseon-era documentation offers provincial-level spatial granularity, enabling more detailed geographical analysis.

Table 1. Data sources utilized for cropland area reconstruction and gridding allocation model.

Table 1. Data sources utilized for cropland area reconstruction and gridding allocation model. - (2)

- The cropland data for the Japanese colonial period were derived from the Korean Economic Yearbook 1918, which contains comprehensive survey records for 23 time points [49]. These surveys, conducted by specially trained Japanese surveyors between 1910 and 1918, systematically documented cropland topography, parcel boundaries, and ownership. Despite the colonial motivations behind the data collection—which included land appropriation and tax expansion—the meticulous surveys provide a relatively accurate representation of cropland development during that era. Annual cropland verification and registration continued until 1940.

- (3)

- Modern cropland statistical data from 1975 to 2000 for South Korea were obtained from Statistics Korea (http://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=101&tblId=DT_1EB001&language=en&conn_path=I3) (accessed on 15 July 2025). For North Korea, cropland area data were primarily sourced from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations. These datasets represent the most widely used and internationally harmonized time-series for comparative agricultural statistics.

2.2.2. Other Modern Basic Data

The contemporary datasets employed in this study comprise modern cropland distribution, topographic features, climatic variables, and soil texture properties, which were used to construct the spatial allocation model for historical cropland. The specific sources and characteristics of these data are described below (Table 1).

- (1)

- The modern cropland data were obtained from the global land cover product by Liu et al. [50], accessible at http://data.ess.tsinghua.edu.cn/ (accessed on 15 July 2025). This dataset was generated on the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform using the latest GLASS Climate Data Records (1982–2015). It features annual land cover classifications—including cropland, forest, grassland, shrubland, tundra, barren land, and ice/snow—with an overall accuracy of 82.81%, confirming its high reliability for large-scale land-cover analysis.

- (2)

- Topographic data, comprising elevation and slope, were derived from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) Digital Elevation Model (DEM) (V4.1), provided by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) (http://srtm.csi.cgiar.org/) (accessed on 15 July 2025). Slope was calculated from the DEM to maintain data integrity and spatial resolution.

- (3)

- Climatic parameters, including growing degree days and precipitation averages for the 1960–1990 period, were sourced from the FAO’s Global Agro-ecological Zones (GAEZ) database (https://gaez.fao.org, accessed on 16 July 2025).

- (4)

- Soil texture data, including clay, silt, and sand content, were retrieved from SoilGrids (www.soilgrids.org) (accessed on 10 July 2025) at a spatial resolution of 250 m.

To maintain spatial consistency across the analysis, all input data with varying original resolutions were resampled to the 10 km × 10 km grid used for cropland reconstruction.

2.3. Methods for Cropland Area Reconstruction

2.3.1. Historical Cropland Area Correction

Through a critical analysis of historical cropland data sources and their characteristics from the Goryeo and Joseon dynasties, this study selected four highly reliable benchmark years—AD 1069, 1420, the 1590s, and 1634—for reconstructing cropland area on the Korean Peninsula. However, historical cropland records from the pre-modern period used the gyeol (a traditional Korean unit of land area) as the basic unit for land measurement, calculation, and registration. The actual area represented by one gyeol was not fixed and changed over time, making it impossible to directly compare these historical data with modern cropland statistics. Therefore, as an essential preprocessing step in the reconstruction process, all gyeol-based data were converted into modern standard area units to ensure consistency and comparability across the temporal series.

Based on previous research, which involved a detailed analysis of land classification and the corresponding conversion factors from the traditional Korean unit gyeol to hectares for four historical periods, the following specific coefficients were applied: for the year AD 1069, when land was not classified into grades, a uniform conversion factor of 2.56 was used; for AD 1420, when land was classified into upper, middle, and lower grades, the coefficients were 0.61, 0.96, and 1.38, respectively; for the 1590s and AD 1634, when land was divided into six grades, the coefficients were 0.91, 1.07, 1.30, 1.65, 2.28, 3.65 and 1.00, 1.17, 1.43, 1.81, 2.50, 4.00, respectively [51,52]. Using the historical cropland records and these gyeol-to-hectare conversion factors, we reconstructed the cropland area from the Goryeo to Joseon periods. The formula is:

where is the national or provincial cropland area in year t, represents the historical cropland data from the Goryeo and Joseon dynasties recorded in gyeol, n is the total number of cropland grades, i denotes a specific grade, and is the grade-specific conversion coefficient from gyeol to hectares. In practice, when historical records specified the gyeol area for each grade, the corresponding coefficient was applied, respectively. Conversely, if only the total gyeol area was available, the conversion used the coefficient for the lowest-grade cropland.

2.3.2. Regional Cropland Area Reconstruction

Based on available cropland records and calibration methods, this study reconstructed total cropland area for the Korean Peninsula for the years AD 1069, 1420, 1590, 1630, 1910–1940, and 1975–2000, along with provincial-level cropland areas for AD 1420, 1590, and 1630. To ensure consistent administrative units for gridded reconstruction and enhance the reliability of spatial allocation, provincial cropland areas were also reconstructed for six additional key time points (AD 1069, 1910, 1930, 1940, 1980, and 2000). This was achieved by apportioning the total cropland area of each period using province-specific cropland ratios. The provincial ratios for 1980 and 2000 were derived directly from contemporary remote sensing-based land use data. For AD 1069, 1910, 1930, and 1940, where direct records were lacking, provincial ratios were extrapolated based on data from 1420, 1630, and 1980, respectively, taking into account the historical context of agricultural expansion. Ultimately, this process yielded a complete reconstruction of total cropland area spanning the past millennium and provincial-level cropland area for nine major historical periods.

2.4. Methods for Spatially Explicit Allocation

2.4.1. Determination of the Maximum Extent of Cropland

An analysis of agricultural development on the Korean Peninsula reveals a long-term increasing trend in cropland area, driven largely by population growth. In North Korea, cropland expanded rapidly until the 1990s, after which it stabilized. In South Korea, cropland area peaked in the 1960s–1970s before declining due to urbanization and ecological restoration. Critically, the literature indicates that the net reduction in South Korea’s cropland from 1900 to 2000 was minimal, amounting to only 0.71% of the total area—a change too small to substantially alter the overall distribution pattern. This consistent historical trajectory supports the fundamental premise of this study: the vast majority of historical cropland during the study period likely falls within the extent of modern cropland distribution.

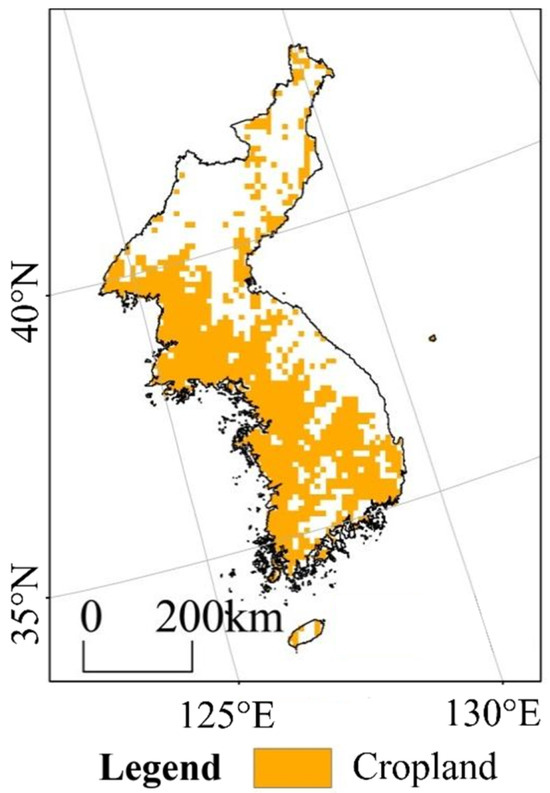

Guiding by the rationale that historical cropland largely falls within modern extents, this study utilized the longest available satellite-derived cropland inventory by Liu et al. [50] as the baseline. This dataset, spanning 1982 to 2015, informed the creation of a maximum cropland extent map for the Korean Peninsula. We generated a unified coverage by calculating the spatial union of LUCC data at a 10 km × 10 km grid resolution for key years (1982, 1985, 1990, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015). The resulting distribution highlights a concentration of arable land in the southwestern and southern coastal regions, with limited grid availability in the northeast (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Extent of maximum cropland distribution on the Korean Peninsula.

2.4.2. Land Suitability Model for Cultivation

To quantitatively assess land reclamation suitability at the grid scale, we selected key drivers of land use change based on the established principle that cultivation prioritizes more accessible and productive lands first. This approach yields a spatially explicit suitability index for the Korean Peninsula.

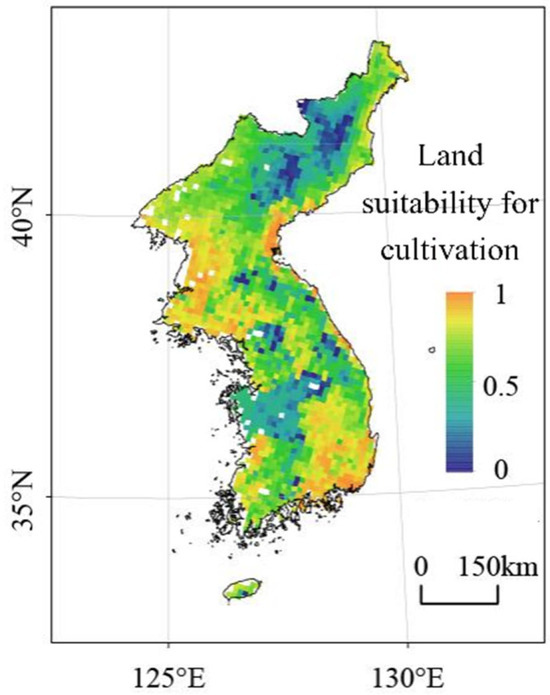

Historical evidence indicates that cropland distribution on the Korean Peninsula has been historically concentrated in plains and lower elevations, with climate and soil being primary controlling factors. Despite advanced agricultural techniques that introduced drought-resistant crops and irrigation—making cumulative temperature a key climatic determinant—inherently poor soil quality consistently constrained land use. These factors informed our selection of modern spatial drivers for suitability modeling.

Based on the principles of dominance, stability, and data availability, we constructed a spatially explicit land suitability model for cultivation at the grid scale. For a given province with known cropland quota and potential distribution area, this model integrates four normalized factors: cumulative temperature and soil sand–clay ratio (reflecting land quality), alongside elevation and slope (indicating reclamation difficulty). An equal-weight approach was applied to combine these factors into the final model.

The normalization of each factor was conducted based on its hypothesized relationship with reclamation suitability. A negative relationship was assumed for topographic factors: within each province, suitability increases with lower elevation and gentler slope. A positive relationship was applied to climatic factors, where higher cumulative temperature indicates greater suitability. For soil texture, suitability was defined as being proportional to the proximity of the sand-to-clay ratio to 1, reflecting optimal loam conditions.

Following this analysis, each factor was normalized and integrated to construct a composite land suitability model for cultivation. The normalization equations for each factor are described below:

- (1)

- Elevation and slopewhere and are normalized elevation and slope values for grid j within province i (range [0, 1]), respectively; and are the maximum elevation and slope values in province i, respectively; and are the original elevation and slope values for grid j in province i, respectively.

- (2)

- Accumulated temperaturewhere represents the normalized cumulative temperature value for grid j within province i (range [0, 1]); denotes the maximum cumulative temperature value in province i; is the original cumulative temperature value for grid j in province i.

- (3)

- The soil texturewhere , , and represent the sand-to-clay ratio, sand content, and clay content for grid j in province i, respectively; is the normalized sand-to-clay ratio of grid j in province i; and are the maximum sand-to-clay ratio in province i and the original sand-to-clay ratio of grid j in province i, respectively.

- (4)

- Land suitability model for cultivation:where is the land suitability for cultivation of grid j in province i; , , , and are the normalized elevation, slope, cumulative temperature, and sand-to-clay ratio of grid j in province i, respectively.

Based on the methodology described, a land suitability model for cultivation was developed and its spatial distribution is visualized in Figure 3. The resulting suitability map reveals a distinct spatial pattern: higher suitability values are concentrated in the western and southern coastal regions, while the northeastern part of the peninsula demonstrates consistently low suitability.

Figure 3.

Land suitability for cultivation of the Korean peninsula based on the regional unit.

2.4.3. Gridding Allocation Method for Cropland

The total cropland area for each province was disaggregated into its constituent grid cells based on the maximum cropland extent and modeled land suitability values to reconstruct the historical distribution for the Korean Peninsula, as formulated below:

where denote cropland area of grid j in year t; is the land suitability for cultivation of grid j in province i; represent cropland area of province i in year t. denote an indicator for the maximum cropland distribution extent; which equals 0 if grid j is outside the allowable cropland extent, and 1 otherwise.

Based on the gridded cropland reconstruction methodology, we spatially allocated the provincial-level cropland data of the Korean Peninsula to a 10 km grid scale. This process generated a gridded cropland dataset for nine historical time points over the past millennium: 1069, 1420, 1590, 1630, 1910, 1930, 1940, 1980, and 2000.

3. Results

3.1. Changes of Cropland Area

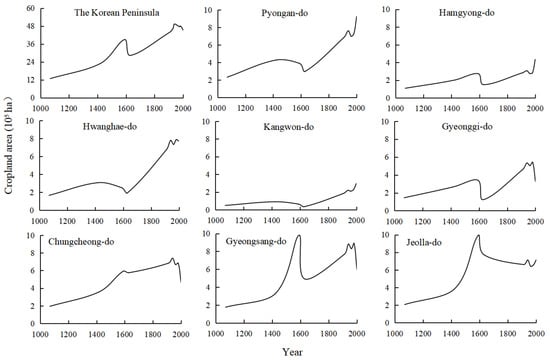

Over the past millennium, the total cropland area on the Korean Peninsula exhibited a fluctuating yet overall increasing trend, rising from 1.28 × 106 ha in AD 1069 to 4.53 × 106 ha in 2000—a net expansion of 3.25 × 106 ha (Figure 4). A notable peak of 4.93 × 106 ha was recorded in 1940. The long-term trajectory comprised four distinct phases: rapid increase (AD 1069–1590), sharp decline (AD 1590–1630), recovery and growth (AD 1630–1940), and a fluctuating decrease (1940–2000). The overall trend of provincial cropland mirrored that of the total area, but pronounced disparities remained among regions (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Changes of cropland area at the national and provincial level of the Korean Peninsula over the past millennium.

As shown in Figure 4, during AD 1069–1420, all provinces exhibited cropland expansion, though Gangwon-do lagged significantly (0.41 × 105 ha). The northern province of Pyeongan-do led with an increase of 1.94 × 105 ha, while southern provinces—Jeolla-do and Chungcheong-do—also expanded notably (1.75 × 105 ha and 1.65 × 105 ha, respectively). From AD 1420 to the 1590s, a clear north–south dichotomy emerged: northern and northeastern provinces (Pyeongan-do, Hwanghae-do, and Gangwon-do) experienced decline, with Hwanghae-do decreasing by 0.57 × 105 ha. In contrast, southern provinces underwent substantial growth—Gyeongsang-do and Jeolla-do increased by 6.55 × 105 ha and 6.11 × 105 ha, respectively, and Chungcheong-do rose by 2.33 × 105 ha. These shifts reflect agricultural incentives under the Goryeo and Joseon dynasties, which spurred rapid development in the topographically favorable south, while rugged terrain limited gains in the north and northeast.

By AD 1630, cropland area had declined across all provinces of the Korean Peninsula as a result of the Japanese invasions of Korea (the Imjin War and Jeongyu War). The most pronounced reduction occurred in Gyeongsang-do, which decreased by 4.89 × 105 ha, followed by Jeolla-do and Gyeonggi-do, with declines of 2.21 × 105 ha and 2.19 × 105 ha, respectively (Figure 4). Moderate losses were recorded in Hamgyeong-do (1.25 × 105 ha) and Pyeongan-do (0.90 × 105 ha), while the smallest decreases were observed in Gangwon-do (0.29 × 105 ha) and Chungcheong-do (0.18 × 105 ha). These patterns indicate that the southern provinces were more severely affected by the conflicts. Nevertheless, due to their originally larger cropland base, total cropland area in the south remained higher than in the northern regions.

During the subsequent period until 1940, cropland area increased across all provinces except Jeolla-do. The most substantial expansion occurred in the northern provinces of Hwanghae-do and Pyeongan-do, which grew by 5.86 × 105 ha and 4.65 × 105 ha, respectively. These were followed by the southern provinces of Gyeonggi-do and Gyeongsang-do, which increased by 4.10 × 105 ha and 3.90 × 105 ha. More moderate gains were observed in Gangwon-do (1.84 × 105 ha), Chungcheong-do (1.65 × 105 ha), and Hamgyeong-do (1.57 × 105 ha) (Figure 4). This widespread recovery and expansion can be attributed to a period of relative political stability, the implementation of the “Rice Production Increase Plan” under Japanese colonial administration, and rapid advancements in irrigation technology. These factors collectively facilitated agricultural reclamation, particularly in the previously less-cultivated northern regions, where cropland expansion was most pronounced.

Post-1945 to 2000, cropland area declined across most provinces except for the northern and northeastern regions of Pyeongan-do, Hamgyeong-do, and Gangwon-do. These three provinces experienced increases of 1.64 × 105 ha, 1.29 × 105 ha, and 0.80 × 105 ha, respectively. In contrast, the southern provinces of Gyeongsang-do, Chungcheong-do, and Gyeonggi-do saw the most significant reductions, declining by 2.86 × 105 ha, 2.77 × 105 ha, and 2.08 × 105 ha (Figure 4). This divergence reflects fundamentally different post-division development pathways: cropland expansion continued in the North Korea, driven by an agriculture-focused economy, while the South Korea experienced rapid urbanization, converting large areas of cropland to built-up land.

3.2. Spatial Pattern Changes of Cropland Cover

As shown in Figure 5, cropland in the Korean Peninsula was predominantly distributed in the western coastal regions during historical periods. Over the millennium, driven by population growth and advancements in agricultural technology, the cultivated land ratio increased progressively from 5.72% in 1069 to 20.31% in 2000. Concurrently, the extent of cultivated areas expanded gradually from the western coastal zone toward the eastern and southern regions.

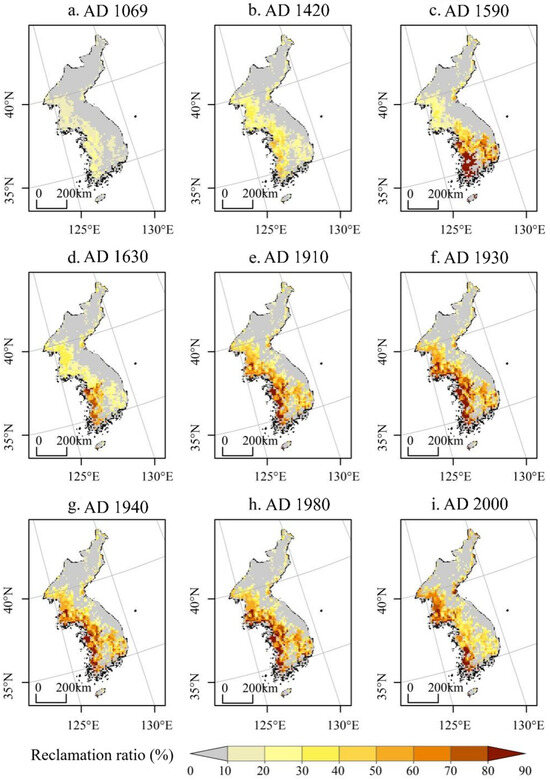

Figure 5.

Spatial distribution pattern of cropland in the Korean Peninsula over the past millennium (10 km × 10 km).

In AD 1069, croplands were predominantly concentrated in the topographically favorable western coastal zone, with minimal distribution in the mountainous northeast. Subsequently, a period of stability under the Goryeo dynasty, supported by pro-agricultural policies, fostered agricultural expansion. This trend continued into the Joseon dynasty with land system reforms, leading to the reclamation of fertile coastal areas along the southern and western seas. Consequently, the reclamation ratio increased by approximately 6% between AD 1069 and 1420. From AD 1420 to 1590, cropland expanded significantly in the southern regions, with the ratios in Chungcheong-do and Jeolla-do provinces rising to 38% and 40%, respectively. However, the Imjin War caused a notable decline of about 11% in Jeolla-do by AD 1630. A general increasing trend resumed from AD 1630 to 1980. Between 1980 and 2000, divergent trends emerged: the reclamation ratio continued to rise in the north but decreased in the south, with a reduction of up to 15% (Figure 5).

The grid-level reclamation intensity showed a clear increasing trend over time. In AD 1069, all grids had a reclamation ratio below 30%, with 88.7% of grids below 20%. By AD 1420, the proportion of low-intensity grids (20%) decreased to 43.2%, while grids with high intensity (>40%) emerged, accounting for 8.7%, and the maximum ratio reached 60%. This trend continued to AD 1590, with only 30.9% of grids below 20%, and high-intensity grids (>40%) rising to 30.5%, including 12.8% of grids exceeding 80%. However, the Imjin War and Jeongyu War led to a significant decline in reclamation ratios by AD 1630. From AD 1630 onwards, reclamation intensity increased substantially, with maximum values reaching 80–90%. The proportion of low-intensity grids (<20%) eventually decreased to just 12.44%, indicating a significant intensification of land use.

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with Satellite-Based Data

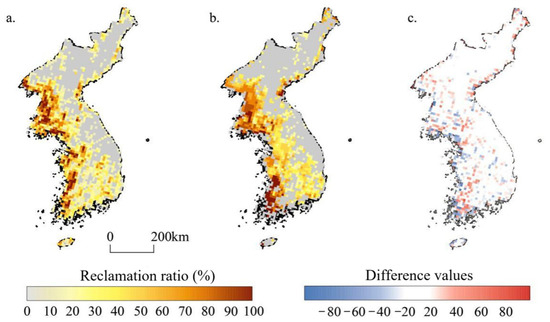

An indirect validation was performed to evaluate the cropland reconstruction method. We applied our method to downscale the year 2000 provincial-level cropland data (from remote sensing) to a grid scale and compared the output with contemporaneous remote sensing-based gridded cropland data [50]. The comparison (Figure 6) demonstrates a high degree of agreement in spatial patterns. The reconstruction accurately captures the concentration of cropland in the western and southwestern coastal areas, its lesser extent in the southeast, and its scarcity in the northeast. The gradient of higher cultivation intensity in the west compared to the south is also well represented, confirming the method’s reliability.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the spatial pattern between the remote sensing data of 2000 and the data of this study in Korean Peninsula ((a) remote-sensing data; (b) cropland reconstructed in this study for the same period; (c) spatial pattern comparison).

We quantitatively assessed the reliability of the reconstruction by calculating the relative difference in reclamation ratio at the grid scale between the reconstruction results and remote sensing data (Figure 6c). A relative difference closer to zero indicates smaller discrepancies between the two datasets. Moreover, a higher proportion of grids with smaller relative differences suggests better agreement between the reconstruction and remote sensing observations, reflecting the greater applicability of the model.

A quantitative comparison reveals strong agreement between the datasets (Table 2). Specifically, 72.12% of the grids exhibit relative differences within ±20%, while 20% show differences between ±20% and ±40%. Grids with differences exceeding ±70% account for only 1.37%, and those below −80% merely 0.14%. No grids had a positive difference greater than +80%. These results demonstrate that the cropland data reconstructed by our method show only minor deviations from the contemporary remote sensing data, indicating a high level of consistency with modern observations. Therefore, the reconstruction methodology presented in this study is validated as a feasible and reliable approach for generating historical gridded cropland datasets.

Table 2.

Statistics on the percentage of grids with difference values between reconstructed cropland and remotely monitored cropland in 2000.

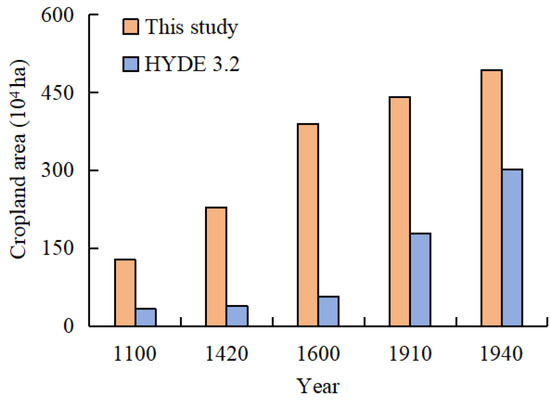

4.2. Comparison with Historical Reconstructions

Long-term cropland change on the Korean Peninsula has been reconstructed in only three global datasets: SAGE, PJ, and HYDE [13,14,15,16,17]. They have reconstructed land use for the Korean Peninsula over varying temporal scales: the past 300 years, the period from 800 to 1700 AD, and the past 12,000 years, respectively. Among these, the HYDE dataset—which covers the entire peninsula and has undergone multiple updates to enhance regional accuracy—serves as the primary benchmark for comparison in this study. HYDE estimates national cropland area based on historical population data and time-varying per capita cropland assumptions. Then, it further incorporates multiple anthropogenic and natural factors such as population and climate for land suitability assessment, which is then used as a weighting scheme to allocate the estimated cropland within statistical units to a grid scale [13].

In contrast, our reconstruction is grounded in a comprehensive analysis of regional historical records, including shifts in governance, tax systems, and land management practices. This approach enables a detailed, data-driven reconstruction of both national and provincial cropland areas across the millennium. Moreover, the gridding methodology adheres to fundamental principles of land reclamation in Korean Peninsula. Factor selection prioritizes dominant and stable determinants of cropland distribution, as well as data availability. Region-specific land-reclamation-suitability models and allocation models were developed to reconstruct the spatial-distribution patterns of cropland in the Korean Peninsula over the past millennium. Thus, the results should also be more reliable than the global datasets.

We extracted cropland area values—a critical input in global gridded reconstructions—from HYDE 3.2 for AD 1100, 1400, 1600, 1910, and 1940, and compared them with our estimates for AD 1069, 1420, 1590, 1910, and 1940. The comparison reveals a systematic underestimation of cropland area in HYDE 3.2 relative to our study (Figure 7). A comparison revealed that our reconstructed cropland totals for the five selected years were higher than those in HYDE 3.2 by factors of 3.9, 5.9, 6.8, 2.5, and 1.6, respectively. Notably, the relative differences are substantial in the pre-industrial period, with underestimations reaching approximately 487% in AD 1400 and 582% in AD 1600. These discrepancies highlight considerable inaccuracies in current global cropland reconstructions for the Korean Peninsula. As a critical input parameter for gridded reconstruction, discrepancies in cropland area will inevitably propagate to the resulting spatial distribution. A detailed comparative analysis falls beyond the scope of this paper and will be addressed in a separate study.

Figure 7.

The total cropland area of the Korean Peninsula from the HYDE 3.2 and this study.

4.3. Comparison with Previous Studies

Our reconstruction reveals a clear divergence in cropland trajectories between North and South Korea following the division of the peninsula. From 1975 to 2000, cropland area increased by roughly 4.9% in North Korea, while decreasing by about 14.6% in South Korea. This finding is supported by multiple lines of evidence: (1) the observed trends are consistent with previous studies on cropland change in both countries based on Landsat series imagery [42,43]; (2) the spatial and temporal patterns correspond with qualitative historical records of agricultural policies in the two regions; and (3) the divergent trajectories are consistent with the distinct physical and socio-economic contexts of North and South Korea.

In North Korea, the expansion was primarily driven by a national policy emphasis on food self-sufficiency and collectivized agriculture, exemplified by the Juche farming method. This, coupled with limited alternative economic development, may have necessitated the continued reclamation of marginal lands, including sloping terrain, to meet domestic food needs [42]. Conversely, in South Korea, rapid industrialization and economic growth from the 1960s onward led to massive rural-to-urban migration, agricultural intensification on prime lands, and significant conversion of cropland to urban and industrial uses. This process, embedded within state-led development plans, fundamentally reshaped the land-use system [43].

While this study provides a spatially explicit account of these divergent outcomes, a detailed quantitative attribution of the observed changes to specific drivers (e.g., exact contribution of policy vs. urban expansion) remains complex and is a recommended direction for future research. Nonetheless, the reconstructed patterns offer a critical empirical basis for understanding how divergent political and economic systems can manifest in distinct long-term land-cover trajectories.

4.4. Limitations of the Study

Although this study developed a provincial-level cropland reconstruction for the Korean Peninsula using local historical documents, several uncertainties remain. First, the reliability of historical agricultural statistics requires careful acknowledgment. Data from the study period may be subject to uncertainties inherent to the original reporting systems, including potential inconsistencies in statistical collection methodologies and limited options for independent ground verification. Particularly for North Korea in the late 20th century, while we have utilized internationally harmonized data (FAO), these inherent uncertainties propagate into our reconstruction. Second, the temporal coverage is constrained by the availability of historical records, resulting in unevenly distributed time points (e.g., 1069, 1420, 1590, 1630, 1910, 1930, and 1940) that may not fully capture continuous change over the past millennium. Third, spatial inconsistencies arise from variations in administrative boundaries across different dynasties and the use of disparate data sources—such as direct conversion of historical units for the Joseon Dynasty, remote sensing-based proportions for modern times, and proportional imputation for periods with missing data. These limitations highlight the need for future studies to integrate additional historical sources and statistical data from the study area and employ spatially explicit methods to improve the accuracy and resolution of long-term land-use reconstructions on the Korean Peninsula.

The land suitability index was constructed using contemporary data, yet applied to reconstruct cropland patterns over a millennium. This temporal extrapolation raises legitimate questions about the validity of applying modern environmental constraints to historical periods. However, we argue that this approach remains methodologically sound for several reasons. First, the index primarily relies on relatively stable natural geographical factors—including topography, soil texture, distance to water sources, and elevation—that change over geological timescales far exceeding the study period. These fundamental constraints have consistently governed agricultural land suitability throughout human history, as demonstrated in similar historical land reconstruction studies [37,38]. Second, we deliberately weighted the index more heavily toward these stable natural factors, while minimizing the influence of more dynamic human factors (e.g., technological inputs, crop varieties) that have indeed changed significantly over time. Third, our primary objective is to reveal macro-scale spatiotemporal patterns and long-term trends of cropland change, rather than to achieve precise pixel-level accuracy for specific years. For this purpose, the index based on stable geographical constraints provides a robust framework for understanding dominant spatial patterns. Nevertheless, we recognize that this approach introduces some uncertainty, particularly regarding potential changes in climate conditions and soil properties over the millennium. Future studies could further refine this methodology by incorporating paleoclimate reconstructions and paleosol data when available, which would help to better account for temporal variations in environmental conditions.

Uncertainties in the spatial gridding procedure stem from several methodological limitations. First, the coarse resolution of historical records introduces ambiguity in delineating period-specific cropland extent. To mitigate this, we applied a foundational assumption informed by the agricultural history of the Korean Peninsula: given that modern population density far exceeds pre-industrial levels and reclamation technologies have advanced significantly, historical cropland area must have been smaller than contemporary distributions. While pragmatic, this approach may result in cropland being allocated to areas not cultivated in the past. Second, the spatial allocation model, though practical for large-scale, long-term reconstruction, is subject to a “flat-allocation bias” common to suitability-driven methods: grid cells with positive suitability scores within the maximum allocable area are assigned cropland regardless of historical cultivation. This effect is especially pronounced in low-suitability zones and may lead to systematic overestimation. Finally, because factor quantification and model construction were performed at the sub-regional scale, minor discontinuities can arise along the boundaries of adjacent spatial units.

5. Conclusions

This study reconstructs a millennium-long provincial-level cropland area series for the Korean Peninsula by integrating historical records from the Goryeo and Joseon dynasties, land surveys from the Japanese colonial period, and modern statistics. Then, we constructed a cropland spatial allocation model, and the provincial totals were thereby allocated to a 10 km × 10 km grid. The resulting dataset can enhance the accuracy of global historical land-use products and serve as foundational data for research on historical climate change. The main conclusions are as follows.

The total cropland area on the Korean Peninsula has shown a fluctuating yet overall increasing trend at the provincial level, with significant regional variations over the past millennium. The long-term trajectory comprised four distinct phases: rapid increase (AD 1069–1590), sharp decline (AD 1590–1630), recovery and growth (AD 1630–1940), and a fluctuating decrease (1940–2000). The overall trend of provincial cropland mirrored that of the total area, but pronounced disparities remained among regions.

The gridded reconstruction reveals that cropland on the Korean Peninsula was predominantly concentrated in the western coastal regions. Over the past millennium, agricultural expansion progressed southward from this initial core, driven by population growth and technological advances. Following the division of the peninsula in the mid-20th century, divergent trends emerged: cropland continued to expand in North Korea, while South Korea experienced a reduction in cultivated area by 2000 compared to 1980.

Validation of the gridded reconstruction method demonstrates a strong spatial agreement between the historical cropland distribution generated in this study and the reference data derived from remote-sensing imagery. Quantitatively, the discrepancies between the two datasets are generally small. Specifically, 72.12% of the grids exhibit relative differences within ±20%, while only 1.37% of grids show differences exceeding ±70%. This high level of consistency confirms the feasibility and reliability of the proposed method for reconstructing historical cropland coverage.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L. and F.H.; methodology, M.L. and C.Z.; software, M.L. and C.Z.; validation, M.L., C.Z., F.H., S.L. and F.Y.; formal analysis, M.L. and C.Z.; investigation, M.L., F.H. and S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L. and C.Z.; writing—review and editing, M.L., C.Z. and F.Y.; supervision, F.H. and S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 42307562, 42371260; the National Key R&D Program of China, grant number 2017YFA0603304.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors due to the data are part of an ongoing study.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author used ChatGPT 3.5 for writing assistance, mainly for grammar and spelling checks. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ellis, E.C.; Gauthier, N.; Klein Goldewijk, K.; Bird, R.B.; Boivin, N.; Díaz, S.; Fuller, D.Q.; Gill, J.L.; Kaplan, J.O.; Kingston, N.; et al. People have shaped most of terrestrial nature for at least 12,000 years. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2023483118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.W.; Yu, L.; Li, X.C.; Chen, M.; Li, X.; Hao, P.Y.; Gong, P. A 1 km global cropland dataset from 10000 BCE to 2100 CE. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 5403–5421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, N. How humans changed the face of Earth. Science 2019, 65, 865–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephens, L.; Fuller, D.; Boivin, N.; Rick, T.; Gauthier, N.; Kay, A.; Marwick, B.; Armstrong, C.G.D.; Barton, C.M.; Denham, T.; et al. Archaeological assessment reveals Earth’s early transformation through land use. Science 2019, 365, 897–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderman, J.; Hengl, T.; Fiske, G.J. Soil carbon debt of 12,000 years of human land use. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 10811–10816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, J.A.; Defries, R.; Asner, G.P.; Barford, C.; Bonan, G.; Carpenter, S.R.; Chapin, F.S.; Coe, M.T.; Daily, G.C.; Gibbs, H.K.; et al. Global consequences of land use. Science 2005, 309, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, A.M.d.; Franceschi, M.; Panosso, A.R.; Carvalho, M.A.C.d.; Moitinho, M.R.; Martins Filho, M.V.; Oliveira, D.M.d.S.; Freitas, D.A.F.d.; Yamashita, O.M.; La Scala, N., Jr. Effects of land use changes on CO2 emission dynamics in the Amazon. Agronomy 2025, 15, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, M.J.; Archontoulis, S.V.; Helmers, M.J.; Poffenbarger, H.J.; Six, J. Sustainable intensification of agricultural drainage. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 914–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findell, K.L.; Berg, A.; Gentine, P.; Krasting, J.P.; Lintner, B.R.; Malyshev, S.; Santanello, J.A., Jr.; Shevliakova, E. The impact of anthropogenic land-use and land-cover change on regional climate extremes. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Dong, G.; Meng, X.; Richard, A.; Houghton; Gao, Y.; He, F.; Li, M.; Li, W.; Liu, Z.; et al. Annual carbon emissions from land-use change in China from 1000 to 2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss. 2025, in review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, R.A.; Nassikas, A.A. Global and regional fluxes of carbon from land-use and land-cover change 1850–2015. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2017, 31, 456–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Past Global Changes Working Group. LandCover6k. Real Project. 2014. Available online: http://www.real-project.eu/landcover6k-pages-working-group/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Klein Goldewijk, K.; Beusen, A.; Doelman, J.; Stehfest, E. Anthropogenic land-use estimates for the Holocene—HYDE 3.2. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2017, 9, 927–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein Goldewijk, K.; Beusen, A.; Van Drecht, G.; De Vos, M. The HYDE 3.1 spatially explicit database of human-induced global land-use change over the past 12,000 years. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2011, 20, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramankutty, N.; Foley, J.A. Estimating historical changes in global land cover: Croplands from 1700 to 1992. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 1999, 13, 997–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramankutty, N. Global Cropland and Pasture Data from 1700–2007. Available online: https://search.dataone.org/view/Global_Cropland_and_Pasture_Data_from_1700-2007.xml (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Pongratz, J.; Reick, C.; Raddatz, T.; Claussen, M. A reconstruction of global agricultural areas and land cover for the last millennium. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2008, 22, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, J.O.; Ruddiman, W.F.; Crucifix, M.C.; Ellis, E.C.; Ruddiman, W.F.; Lemmen, C.; Klein Goldewijk, K. Holocene carbon emissions as a result of anthropogenic land-cover change. Holocene 2011, 21, 775–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, G.J.; Wei, L.; Wang, B.; Yu, L. Contrasting influences of biogeophysical and biogeochemical impacts of historical land use on global economic inequality. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Tian, P.; Luo, H.; Hu, T.; Dong, B.; Cui, Y.; Khan, S.; Luo, Y. Impacts of land use and land cover changes on regional climate in the Lhasa River basin, Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 742, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Quéré, C.; Andrew, R.M.; Friedlingstein, P.; Sitch, S.; Hauck, J.; Pongratz, J.; Pickers, P.A.; Korsbakken, J.I.; Peters, G.P.; Canadell, J.G.; et al. Global carbon budget 2018. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2018, 10, 2141–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Tian, H.; Lu, C.; Lu, C.Q.; Dangal, S.R.S.; Yang, J.; Pan, S.F. Global manure nitrogen production and application in cropland during 1860–2014: A 5-arcmin gridded global dataset for Earth system modeling. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2017, 9, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein Goldewijk, K.; Verburg, P.H. Uncertainties in global-scale reconstructions of historical land use: An illustration using the HYDE data set. Landsc. Ecol. 2013, 28, 861–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.Q.; Zhao, W.Y.; Zhang, C.P.; Zhang, D.Y.; Wei, X.Q.; Qiu, W.L.; Ye, Y. Methodology for credibility assessment of historical global LUCC datasets. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2020, 63, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.S.; He, F.N.; Yang, F.; Li, S.C. Uncertainties of global historical land use scenarios in past-millennium cropland reconstruction in China. Quat. Int. 2022, 641, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.J.; He, F.N.; Zhao, C.S.; Yang, F. Evaluation of global historical cropland datasets with regional historical evidence and remotely sensed satellite data from the Xinjiang area of China. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, L.; Li, S.; Gao, D.; Li, W. Uncertainties of global historical land use datasets in pasture reconstruction for the Tibetan Plateau. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.Y.; Fang, X.Q.; Yang, L.E. Comparison of the HYDE cropland data over the past millennium with regional historical evidence from Germany. Reg. Environ. Change 2021, 21, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.C.; He, F.N.; Zhang, X.Z.; Zhou, T.Y. Evaluation of global historical land use scenarios based on regional datasets on the Qinghai-Tibet Area. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 657, 1615–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, J.O.; Krumhardt, K.M.; Gaillard, M.J.; Sugita, S.; Trondman, A.K.; Fyfe, R.; Marquer, L.; Mazier, F.; Nielsen, A.B. Constraining the deforestation history of Europe: Evaluation of historical land use scenarios with pollen-based land cover reconstructions. Land 2017, 6, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.B.; Jansson, U.; Ye, Y.; Widgren, M. The spatial and temporal change of cropland in the Scandinavian Peninsula during 1875-1999. Reg. Environ. Change 2013, 13, 1325–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, J.O.; Krumhardt, K.M.; Zimmermann, N. The prehistoric and preindustrial deforestation of Europe. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2009, 28, 3016–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaillard, M.J.; Morrison, K.D.; Madella, M.; Whitehouse, N. Past land use and land-cover change: The challenge of quantification at the subcontinental to global scales. Past Land Use and Land Cover 2018, 26, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, H.X.; Chen, Q.; Wu, Z.L.; Zhi, Z.M.; Fang, W.G.; Sun, J.Q.; Shi, Y.N. Reconstruction of cropland for the Rikaze Area of China since the Tubo Dynasty (AD 655). Land 2025, 14, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, H.L. The application of ANN-FLUS model in reconstructing historical cropland distribution changes: A case study of Vietnam from 1885 to 2000. J. Nat. Resour. 2024, 39, 1473–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Li, J.; Fang, X.Q.; Zhang, D.Y.; Zhao, Z.L.; Wu, Z.L.; Lu, Y.J.; Li, B.B. Reconstruction of cropland change in European countries using integrated multisource data since AD 1800. Boreas 2023, 52, 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.N.; Yang, F.; Zhao, C.S.; Li, S.C.; Li, M.J. Spatially explicit reconstruction of cropland cover for China over the past millennium. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2023, 53, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.C.; Liu, Y.T.; Li, J.R.; Zhang, X.Z. Mapping cropping patterns in the North China Plain over the past 300 years and an analysis of the drivers of change. J. Geogr. Sci. 2024, 34, 2074–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, L.C.P.; Pimenta, F.M.; Santos, A.B.; Costa, M.H.; Ladle, R.J. Patterns of land use, extensification, and intensification of Brazilian agriculture. Glob. Change Biol. 2016, 22, 2887–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, R.; Herold, M.; Verburg, P.H.; Clevers, J.G.P.W. A high-resolution and harmonized model approach for reconstructing and analyzing historic land changes in Europe. Biogeosciences 2013, 10, 1543–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Ma, F.D.; Park, S.J.; Lee, D.K. Monitoring land-use/land-cover and landscape-pattern changes at a local scale: A case study of Pyongyang. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.L.; Yu, H.; Wang, Z.M.; Li, M.Y. Land cover change of the DPRK and its driving forces from 1990 to 2015. J. Nat. Resour. 2019, 34, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Z.M.; Ren, C.Y.; Mao, D.H.; Jia, M.M. Land cover change and its driving forces in the Republic of Korea since the 1990s. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2017, 37, 1755–1763. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.Y.; Tak, H.M. Land-use changes and climate patterns in Southeast Korea. J. Korean Assoc. Geographic Inf. Stud. 2013, 16, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, F.N.; Li, D.X. The Economic History of Korea; Yanbian University Press: Yanji, China, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, I.J. The History of Goryeo; Southwest University Press: Chongqing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hwangbo, R. The Annals of King Sejong; The Research Institute for Oriental Culture of Gakushuin University: Tokyo, Japan, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, B.H.; Lee, M.R.; Park, Y.D. Supplementary Literature Compilation; Meibundo: Toyama, Japan, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.R. 1948 Korean Economic Yearbook; Korea Bank Investigation Department: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Gong, P.; Wang, J.; Clinton, N.; Bai, Y.; Liang, S. Annual dynamics of global land cover and its long-term changes from 1982 to 2015. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2020, 12, 1217–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. Study on the Land System of Goryeo; Daewangsa: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Hiroshi, A. The restoration of Korean ancient Gyeolbe-je (結負制) and the origin of Japanese Dai-sei (代制). Soc. Hist. Metrol. Jpn. 2009, 31, 139–152. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.