Abstract

This paper investigates land-use as the cornerstone of spatial planning in rapidly urbanising contexts, focusing on the critical gaps at the mesoscale between centralised vision and local implementation. By exploring Java’s complex desakota landscapes, this study employs an innovative GIS-based land-use cluster analysis using multidimensional parameters—including slope, population density, agricultural land, forest cover, and surface water—to categorise land-use patterns. The resulting mesoscale clusters reveal cohesive functional territories that transcend traditional political boundaries, articulating distinctive ‘mixtures’ of urbanity within Java’s rural-urban continuum. This approach not only captures socio-environmental dynamics across administrative silos but also establishes a new strategic framework for regional planning challenges. By advancing boundary-making beyond mere political convention to reflect on-the-ground ecological and functional coherence, this framework responds to the urgent global challenge of reconciling accelerating suburban and regional development pressures with the preservation of local communities, agricultural systems, and natural landscapes.

1. Introduction

1.1. Epistemological Predicament

Since Lefebvre, the spatial disciplines have grappled with the limitations of their most critical tool: the boundary. Lefebvre critiqued the notion that political boundaries could adequately encapsulate the lived experiences and socio-spatial dynamics of individuals and communities [1]. Neil Brenner expands upon this through his concept of “scalar politics”, which posits that political and economic processes operate across multiple, intertwined scales—from the local to the global—creating a web of interdependencies that cannot be addressed through state-centric frameworks alone [2]. This lens elucidates how local economies often defy or reconfigure the impositions of political boundaries. In this vein, Brenner and scholars like Saskia Sassen argue that the socio-spatial dynamics of urban areas consistently spill across these boundaries, generating intricate economic and cultural linkages that elude conventional political frameworks.

This notion and Lefebvre’s critique of abstract space serve as the theoretical underpinnings of this study. State-centric boundaries often produce an “abstract space” that simultaneously homogenises and fragments the “lived space” of everyday social and ecological practice. Brenner, in particular, demonstrates how contemporary urbanisation operates as a variegated process of “rescaling,” generating polymorphic territorial configurations that effectively “explode” the urban-rural divide. Fundamentally, however, the ambiguity originates in ill-defined urban/non-urban divisions [3]. This conceptual lacuna has significant practical consequences for planning, as it undermines a central tenet of good practice: integration of socio-spatial systems. While the goal of developing strategies that cross temporal and scalar dimensions is much-vaunted, it remains seldom achieved. Realising this goal necessitates a cross-scalar representation of socioeconomic and environmental geographies—a task complicated in practice by conflicting goals, conditions, and toolsets at either end of the spectrum. This bifurcated reality pits macro-level, state-centric, technocratic schemas against micro-level, community-driven, disconnected initiatives. The result is a planning paradigm that relies on centralised visions to interpret diverse local conditions, while assuming diverse grassroots efforts will all align with central plans and visions. In reality, both forces driving urbanisation systematically bypass the critical meso-level territories that physically and conceptually connect strategies and projects forged at either scale.

A second, widely accepted tenet of spatial planning is environmental sustainability. Yet for ecological planning, a similar theoretical and practical void persists. Within this context, Friedmann and Weaver’s theoretical framing of the “functional region” (1979) posits that territory should be defined by integrated socio-ecological processes—such as watersheds or economic flows—rather than inherited political jurisdictions. This perspective reveals administrative boundaries to be frequently incongruent with the “assemblages” of human and non-human actors that co-produce space. Our analysis of Java’s desakota thus begins from the premise that effective planning requires a shift from managing static political territories towards governing dynamic functional ones. This entails systematic approaches to interconnected issues such as of natural ecologies, biodiversity, and waste and water management.

Yet, these challenges have become inherently cross-sectoral. In many parts of the world, technocentric, sectoral concerns no longer exist within discrete spatial boundaries. Instead, they are profoundly intertwined with peri-urban contexts—a reality that exacerbates complex landscape system issues, as exemplified by falling water tables, polluted surface water, and severe ecosystem fragmentation. Such phenomena invalidate singular, sectoral approaches and underscore the necessity of understanding the land-use implications of what are fundamentally wholly intertwined issues.

In this context, land-use analysis provides a crucial common denominator. Though often overlooked, land-use planning offers an essential framework for navigating complex, multifaceted challenges and for prioritising actions within long-term, cross-scalar, and multidisciplinary strategies [4].

However, practical and epistemological hurdles continue to subvert planning integration. This is particularly evident in land-use, where the increasing heterogeneity of peri-urban territories impedes the foundational tasks of spatial mapping and analysis. Integrative efforts are further challenged by a necessary yet complicating shift in focus: the planning community’s attention has rightly turned towards the metropolitan fringe and productive rural landscapes, where urban and rural systems collide. In rapidly transforming territories like Java’s fragile desakota, understanding and guiding this development is critically important. Yet here, the integrity of foundational planning concepts erodes; without distinct core/hinterland hierarchies, traditional models like the ‘compact city’ and ‘urban growth boundary’ lose their coherence.

More disconcertingly, centralised and spatially delimited planning schemes—from resiliency projects to housing compounds—increasingly dominate development in the Global South. Despite their clean configurations, these projects function as remote, disconnected interventions that invariably disrupt the very topographies they aim to enhance. This, in turn, accelerates the demand for costly infrastructural conduits, exacerbates socio-spatial contrasts, and ultimately fails to address the needs of local and rural communities [5].

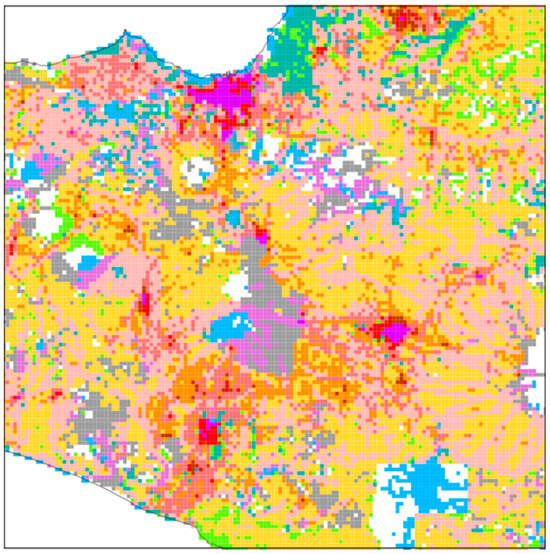

Advances in geospatial technology since the late 1980s have provided invaluable analytical tools, enabling the production of hyper-detailed maps of vast territories with granular precision, often transcending political boundaries. However, as our initial land-use analysis demonstrates (Figure 1), the detailed pixel-based maps commonly used to represent heterogeneous landscapes can obscure clear interpretations of regional development trends, ultimately failing to adequately inform policymakers and planners. Conversely, the vector maps typically used to delineate political boundaries and policy zones cannot capture the programmatic intricacies within their borders. While both tools are vital for research, their inherent complexity contrasts sharply with the calibrated abstraction necessary for prescriptive, flexible, and long-term planning at the mesoscale.

Figure 1.

Initial trial of pixelated representation of the raster data—using binary numeral system (0, 1).

The intermediary scale of the region, which spans between national policy and local action, continues to harbour significant administrative and epistemological blind spots. Addressing these is critical to prevent the much-discussed gap between urban theory and planning practice from widening further. To bridge this gap, this paper explores a cluster-based land-use analysis. Applied to Central Java, this method distils mesoscale land-use patterns to create a framework for planning across political boundaries and mediating between macro and micro-scale objectives. By integrating cultural, agricultural, and natural systems into a streamlined model, GIS-based clusters advance sustainable planning approaches that are resilient and grounded in local and regional realities.

1.2. Context—Colliding Morphologies and Ideologies

Java, the world’s most populous island, is also one of its most rapidly urbanising regions [6,7]. The Indonesian government’s response is a comprehensive national spatial plan for 2045, championing standardised contemporary global urbanism—e.g., new highways, ports, and tech hubs. However, this top-down trajectory risks exacerbating the vulnerabilities of Java’s unique and fragile desakota landscape. The risks infrastructure-driven centralised planning poses to fragile landscapes are twofold: first, a fundamental scalar disconnect that overlooks local spatial realities, and second, its role in catalysing subsequent rounds of in situ, informal development. These two forms of development—mechanised urbanity and productive rurality—compete for the same space in a symbiotic yet ultimately degenerative cycle, wherein the distinct qualities of both realms are lost, yielding more fractured and less sustainable hybridised landscapes.

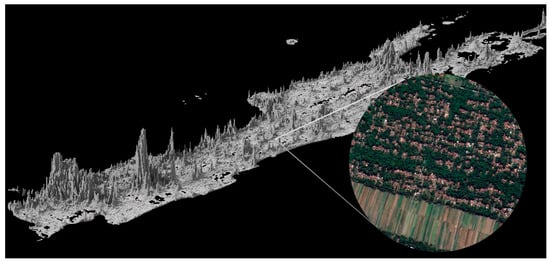

The desakota—Indonesia’s distinct manifestation of a densely populated rural-urban typology—is a case in point. While extensively researched [8,9,10], comprehensive planning models for the desakota, and similar peri-urban settings, remain scarce [11]. Having evolved in unison with the natural geography, the desakota blankets Java’s hinterland with striated networks of villages interspersed with private orchards (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Population density graph of Java Island. Census 2020. Circle insert: typical desakota striation, north of YIA airport, Central Java.

This intricate topology formed the bedrock of a virtually autarkic, productive landscape. However, in recent decades, the desakota has been progressively incorporated into the economic spheres of Java’s metropolitan centres [12] and their expanding infrastructural support systems. Notably, following the 2008 financial crisis, the influx of global capital has accelerated generic urban-industrial transformations [13]. Consequently, at a time when its inherent qualities of resilience, self-sufficiency, compactness, and—ultimately—carbon storage are deemed critical in climate mitigation, the fundamental socio-spatial, cultural, and ecological cohesion of the desakota is systematically eroded.

Unlike China’s dramatic reform era urban overhaul, Java’s spatial transformation is not solely rooted in the urban centres, nor to its ‘Extended Metropolitan Regions’. Instead, Java economic transitions are drawn out across its productive landscape—home to around 100 million people, of which 65% live in villages officially labelled as desakota. While extensively documented since the early 1990s, the ubiquitous desakota typology is rapidly mutating beyond its initial definition, as formulated by Terry McGee in the late 1980s. Once self-contained and local, the vast strands of villages, now forced to operate at the scale of global supply chains, are spawning landscapes that “resist being taken-up into a more formal urban system of interconnected, functionally specialised zones” [14] (p. 118).

The practical challenge of addressing this landscape’s erosion is, we posit, embedded in the difficulty of formulating theoretically coherent models. The desakota’s vast, capillary networks constitute the structural antithesis of the metro-core/green-hinterland dichotomy that continues to underpin urban and regional planning. Adapted to local geographies, its delicate waterways and fine-grained infrastructure have largely sufficed until now. Today, however, Java’s agrarian output is increasingly insufficient, and fresh produce cannot efficiently reach distant urban markets, leaving rural communities struggling to sustain themselves. While new highways may bring economic relief to villages near interchanges, integrating these communities into Java’s urban economies also intensifies pressure on existing networks and accelerates land-use transformation and degradation. Ultimately, prevailing planning models—from sectoral zoning and transport-led corridor development to the proliferation of industrial enclaves—fail to strike a deliberate balance between industrial development and preservation, between top-down visions and informal bottom-up processes, and between local rural lifestyles and their deepening dependence on globalised urban economies.

The growing rural-urban codependence and spatial fusion invalidate models based solely on either top-down metropolitan development or the isolated preservation of rurality. While planning discourse in Java has moved beyond a stagnant progress-preservation binary, fundamental predicaments persist. Within the emerging ‘post-desakota’ condition—characterised by average densities of nearly 1000 persons/km2 and increasingly conceptualised as an ‘agro-manufacturing complex’ [15]—the central challenge is no longer whether to integrate colliding realities, but how. This demands answers to more nuanced questions: How can planning instruments mediate the transition of land from agrarian to hybrid uses without accelerating landscape degradation? And, more specifically, how can regional infrastructure be designed to reinforce, rather than erode, the inherent resilience and expanding needs of these intricate settlement systems?

However, the fundamental strategic challenge, palpable across the ASEAN+ region, remains unaltered: balancing progress and preservation [7]. This conflict plays out across scales, as generic, large-scale projects—fueled by neoliberal modes of urbanisation—are crudely juxtaposed onto rural territories, representing incompatible speeds, contrasting morphologies, and opposing ideologies. Meanwhile, with equally transformative force, countless micro-incentives seep into the desakota’s intricate networks, continuously gaining momentum.

The desakota thereby exposes a critical blind spot in regional planning, as manifest in frameworks like Indonesia’s 2045 vision: the cumulative impact of incremental transformations and growing socio-spatial contrasts actively defies the logic of large-scale blueprint planning—and vice versa. The ensuing spatial dynamics, forged at the intersection of global and local transitions, demand critical examination, advanced geospatial analysis, and—most urgently—new planning models capable of mediating disparate socioeconomic realities across temporal and scalar hierarchies.

As Indonesia’s Climate Change Sectoral Roadmap (ICCSR) underscores, rural land-use is the pivotal yet persistently overlooked parameter in this equation. The piecemeal nature of urbanisation—both planned and unplanned—demands a process-driven discipline that can nevertheless be scientifically benchmarked. It is precisely this ad hoc and mercurial dynamic—most prevalent in rapidly transforming productive landscapes—that necessitates the robust, land-use-based methodology advanced in this paper to reconceptualise and ultimately foster a more resilient rural-urban continuum.

1.3. Resilience Matters

1.3.1. The Co-Option of Resilience

A second, widely accepted axiom in planning is a commitment to resilience. In response to urgent climate warnings, the urban disciplines have embraced this concept, which extends beyond sustainability to encompass preparation for systemic shocks. However, this agenda has increasingly been co-opted by neoliberal ‘global city’ narratives preoccupied with securing capital flows. As Adam Ross notes, schemes framed by the risk-resilience binary are “shedding theoretical conjecture” to instead offer actionable projects that aim to “defend and develop” [16]. Yet, the beneficiaries of such developments remain ambiguous. The poorest communities, most vulnerable to climate impacts, rarely receive targeted investments for meaningful risk reduction. Instead, the rhetoric of resilience is used to justify large-scale infrastructure—such as seawalls, Special Economic Zones, and corporate campuses—which, in the ASEAN+ context, functions less as a shield against climate doom and more as a vehicle for opportunistic suburbanisation, aligning with forces of globalisation rather than tangible local needs.

Conceptual inconsistencies exacerbate these practical concerns [17]. The central conflict is a clash of paradigms. On one hand, ‘resiliency urbanism’ is a normative project premised on a city-nature binary; it seeks to reintegrate the urban fabric with a regional ecosystem it assumes is separate and external. Its goal is a designed symbiosis. On the other hand, the theory of ‘planetary urbanisation’ [18] presents a starker analytical reality: there is no non-urban, no “outside.” Urban processes relentlessly subsume all non-urban realms, creating a fragmented planetary fabric where the very idea of a bounded city reconciling with its “natural context” becomes a paradox. Thus, the planning ideal of building resilient cities in symbiosis with nature is fundamentally contradicted by the analytical reality of building them through the continuous subsumption of nature.

It is precisely within the hyper-refined spatial intricacy of the desakota that this theoretical conflict crystallises into a double bind. First, while ‘planetary urbanisation’ describes a deleterious, dispersed global urbanity, its logical spatial antidote is urban compactness. The desakota, however, presents a profound exception: a dispersed settlement that historically achieved a high degree of autonomy through socio-ecological integration, thereby challenging the core assumption that dispersion is inherently unsustainable. Second, corporate agents of ‘resiliency urbanism’ strive to assimilate green solutions within the city model, in order to manufacture a new nature-habitat symbiosis that the desakota has long embodied. Through the lens of technocentric planning, this intricate fabric is thus rendered illegible and out of reach to a practice adamant on infrastructural retrofitting through concrete projects—either heavy-handed or more nature based.

However, a more troubling paradox collapses this neat binary. The desakota’s resilience was predicated on its localisation, diversity and self-reliance. As it is now irrevocably tied into globalised economies, its fine-grained systems are often rendered insufficient, threatening the very autarky that once defined it. The common land-use patterns of budding industrial centralities and their logistic networks are absorbed within its ancient morphology; inherent resilience is replaced by contemporary (planetary) urban dispersion. Thus, the desakota stands not as a naive ideal, but as a pragmatic, existing, and acutely threatened synthesis—a landscape that embodies the functional integration planning theory aspires to, yet cannot replicate or even adequately model.

1.3.2. Land Use Analysis on the Urban Fringe

The city’s edge is the third conceptual hurdle complicating sustainable planning procedures. As urban systems perniciously expand into natural and productive landscapes, they carve out an ever larger heterogeneous peri-urbanity surrounding Asia’s metro regions. These lack the distinct characteristics of either urban or natural landscapes, yet encompass the drawbacks of both. Treating such spaces separately is no longer tenable. Consequently, established models such as the ‘compact city’ become both impractical and logically inconsistent. Enforcing urban growth boundaries is politically difficult in ‘edgeless’, infrastructure-stressed megacities, while the paradigm’s inherently static nature conceptually fails to capture the ongoing, multidirectional dynamics of exurbanisation and rural in situ—or ‘doorstep’—industrialisation [19].

Urban fields such as Java’s Extended Metropolitan Regions are a case in point: compact forms may reduce commutes and fragmentation, but a balance must be struck with other land intensive requirements. Crucially, urban metabolic needs—food, water, energy—demand vast territories for production, harvesting and storage, often far beyond the city core. The concept of ‘artificial cities’ [3] underscores this paradox: dense urban footprints become increasingly reliant on long-distance resource supply chains, a dependency characterised by diminishing returns. The desakota epitomises this tension.

Here, cluster-based land-use analysis offers a critical alternative: as urban programmes scatter beyond political boundaries into the intricate patterns of the desakota, it can capture the ambiguous and shifting edges of metropolitan areas through an objective, data-driven lens [20]. By identifying cohesive regional land-use clusters, planners can establish a consistent delineation between urban and non-urban land types, enabling more tailored and sustainable urbanisation strategies across these ubiquitous transitional zones.

1.3.3. A Method for a Threatened Synthesis

This desakota’s precarious status gives urgent purpose to its study. It demonstrates that achieving density and compactness, socio-spatial cohesion, and localised sustenance across extensive territories is possible [3]. Its symbiotic logic proves that integrated land-use is critical for sustainability and regional resilience. However, this integration cannot materialise through conventional functional zoning or transport-focused territorial definitions, which consistently favour large-scale, context-averse, neoliberal interventions. It is here that our cluster-based land-use analysis intervenes: by translating the desakota’s intricate, existing socio-ecological logic into a legible and defensible spatial framework, it provides an empirical basis to advocate for more resilient and equitable planning. This method moves beyond abstract planning rhetoric, offering a data-driven model to steer investment away from monolithic projects and towards reinforcing the fine-grained, multifunctional landscapes that constitute the region’s innate resilience. Consequently, this analysis is designed not merely to describe through data modelling, but to articulate the type of geospatial tools and land-use principles that can adhere to this synthesis, capturing its logic at a time when its fragile fabric is being dismantled by the speculative forces of both the formally planned and informal components of planetary urbanisation.

1.4. Research Objectives

The drawbacks of planning based strictly on political boundaries are well documented. Less established is the empirical evidence for a land-use-based alternative. This paper’s central objective is to present and validate a land-use cluster model for Java Island, contrasting it with existing administrative district and regency (kabupaten) boundaries. It outlines the cluster methodology and justifies the specific datasets that inform it.

The research is guided by three overarching aims:

- To define the optimal combination of land-use parameters for delineating clusters that promote sustainable planning.

- To determine if land-use clusters can serve as a bottom-up scalable tool for formulating spatial strategies across similar territories.

- To postulate whether, beyond methodological clarity, land-use-based planning can foster new local alliances centred on shared environmental concerns.

To advance these aims, the paper pursues two concrete objectives: first, to test a new geospatial methodology for analysing heterogeneous landscapes—constituting the primary focus of this paper; and second, to prototype the cartography that can inform a grassroots planning process centred on land-use patterns. The mapping exercise overlaying Java’s political boundaries with our land-use cluster analysis for Central Java, supported by initial stakeholder engagement, serves as a prototype for this latter aim [21]. Ultimately, the model’s practical effectiveness must be validated through further field research and tangible planning applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Java Model: Network and Land USE Analysis + Stakeholder Engagement

To critically explore a cluster-based boundary model, this paper builds on the “Metro Java 2045” regional planning project (Mars, Krill, UNDIP, and UGM) and the ensuing studies collectively titled “The Java Model” [21,22]. These works reveal Java’s complex socio-spatial interdependencies and the misalignment between political boundaries and land-use patterns. Leveraging these insights, this paper proposes a land-use-derived taxonomy of functional territories that transcend administrative fragmentation.

This cluster-based approach presents several advantages with broader relevance. It generates maps that (1) reveal practical gradients between urban and non-urban landscapes, which increasingly defy effective categorisation; (2) organise the mesoscale into clusters of manageable size, highlighting regional commonalities often obscured by pixel-based data representation; (3) merge political subdivisions into larger zones that foster community cooperation aligned with natural topographies; (4) enable the replication of bottom-up strategies across similar clusters; and (5) integrate sectoral challenges within a unified environmental framework.

By addressing interrelated issues—such as transport, water, and biodiversity—in an integrated manner, this framework allows complex phenomena like suburbanisation to be reframed for spatial analysis and planning. It is a prerequisite for the cross-sector coordination needed to manage ecosystems, infrastructure, and economic zones holistically, enabling targeted policy interventions across micro-, meso-, and macro-scale realities. Furthermore, as geospatial technologies advance, these cluster boundaries can evolve over time, offering a crucial temporal flexibility unattainable with static political borders.

Naturally, this approach poses challenges, including governance complexities, resistance from local governments, and difficulties integrating novel boundaries into entrenched political processes. We have encountered all these firsthand during stakeholder sessions in Central Java. Nevertheless, exemplars like the Greater London Authority’s functional boundaries demonstrate that, supported by robust institutions and deliberate engagement, land-use-based integrated planning is feasible and effective. Thus, despite the hurdles, this method offers a compelling innovation for coherent planning in dynamic, heterogeneous contexts.

2.2. The RGB-Cluster Method

2.2.1. The Premise of Unifying R/G/B

Central Java’s rural-urban continuum manifests as a fine mesh of people, settlements, and landscapes, where a fractal-like repetition of components ensures their pervasive presence at any scale. If a city is defined by the collocation of people and infrastructure, then planning for Java must account for the collocation of the urban and non-urban as an intrinsic condition.

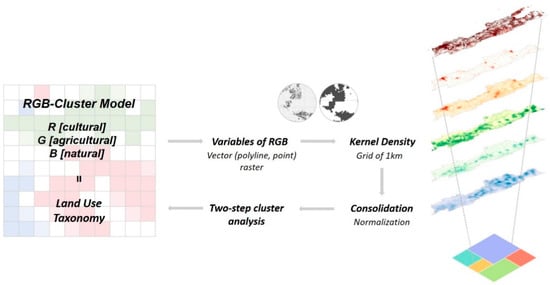

The RGB-cluster method is conceived as a direct response to the epistemological and practical limitations of political boundaries, as outlined in the introduction. Traditional planning relies on administrative units—regencies and districts—that often act as arbitrary containers, fragmenting integrated landscapes and impeding coherent regional strategies. The overall workflow of the RGB-cluster method—from the RGB land-use taxonomy, through kernel density surfaces, to the consolidated cluster layers—is summarised in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The overall research method and process. The RGB-cluster model groups land-use features into three systems: cultural/built (R, red), agricultural/productive (G, green), and natural/restorative (B, blue), which are converted into kernel density layers and then clustered.

Conventional, pixel-based land-use analyses (Figure 1) offer high granularity but often obscure the strategic interpretation essential for mesoscale planning. The obstacle is not data visualisation itself, but the lack of a conceptual framework that translates data into functional planning units. This method’s core premise is that for planning to be effective at the mesoscale, its primary units must be derived from the territory’s functional properties and be legible as such. To this end, we propose a framework that categorises land-use into three fundamental systems—a synthesis we term the “RGB-cluster model”:

- Cultural (Red, R): The built environment and human agglomeration, mapped through building density, population, and road networks.

- Agricultural (Green, G): The productive landscape, mapped through tree cover and irrigation networks.

- Natural (Blue, B): The restorative and protective landscape, mapped through elevation, slope, and waterways.

This RGB division broadly corresponds to ‘built-up’, ‘unbuilt’, and ‘protected’ land, aligning with ‘consumptive’, ‘productive’, and ‘restorative’ systems respectively. This taxonomy advances a critical paradigm shift: from managing land cover to governing a region’s functional metabolism. By categorising territory along this division, the model reframes planning as the integrated management of interdependent flows [3]. It makes explicit the non-negotiable dependencies of the urban economy on its productive hinterlands and restorative ecosystems, establishing a foundational logic for cross-sectoral governance, while highlighting how the spatial fracturing of any single system is detrimental to the whole.

This framework provides a rigorous basis for strategic metabolic trade-offs and performance-based goals. Any new ‘consumptive’ development must be evaluated against its spatial and metabolic cost—the productive capacity it consumes and the restorative systems it degrades. This logic enables targeted interventions: intensifying efficiency in consumptive zones, safeguarding yield in productive lands, and ensuring integrity in restorative areas. It provides the analytical handles needed to decisively move beyond the vague sustainability rhetoric prevalent in regional planning.

Ultimately, this system elevates spatial planning from descriptive mapping to strategic, land-positive stewardship. It provides a scientific rationale for prioritising spatial ‘contiguousness’—whereby the consolidation of specialised territories into larger, interconnected forms is encouraged in order to strengthen their systemic productivity, whether natural or manmade. Contiguousness thus offers a benchmark for spatial form and a pragmatic, easy-to-asses logic to balance consumption, production, and restoration for long-term regional viability.

Paradoxically, by combining these three channels into a single, unified model, we move beyond sectoral or single-function analyses whereby their individual integrity can be observed. This synthesis allows us to articulate the defining characteristic within the complex mixtures of landscapes like the desakota. A pixel is no longer classified as simply ‘urban’ or ‘agricultural’; instead, it is revealed as part of a specific context with proportional combinations of R, G, and B values.

This approach directly addresses the “ill-defined urban/non-urban divisions” cited in the introduction, rejecting the static binary in favour of a continuous, multidimensional gradient. The resulting clusters are not mere land cover classifications but functional territories—coherent zones that can be strategised according to their shared assets.

The RGB framework thus fulfils this paper’s research aims. It provides a coherent, empirically derived land-use cluster pattern for systematic comparison with political boundaries. It enables the identification of an “optimal combination of land-use components”—as defined by the statistical coherence of the resulting clusters, the public availability of the underlying data, and the direct relevance of the seven parameters to regional sustainability and land-use management goals. This fulfils the first research aim. Furthermore, by generating these coherent, mesoscale units, the model itself constitutes a data-derived “tool for bottom-up planning”, providing a spatial framework for locally-informed strategies that can be scaled within and across similar clusters. Ultimately, by framing these clusters as shared socio-ecological environments, this methodology lays the essential groundwork to “foster new local alliances centred on shared environmental concerns”, thereby setting the stage for the research’s broader, long-term ambition.

2.2.2. Data Preparation

Operationalising this theoretical framework required the selection of geographic variables that accurately represent the R, G, and B systems. This process balanced data availability with the need to capture the essential characteristics of Central Java’s landscape.

Selecting RGB variables is a crucial step in defining cluster resolution. While previous studies often rely on numerical assessments of demographic and socio-economic indicators to characterise rural-urban interactions [13,23], this research utilises location-based geographic information processed with Quantum GIS (QGIS) 3.10 “A Coruña” (QGIS.org Assosiation, Zürich, Switzerland).

A distinguishing feature of this study is its cluster-based representation, which simplifies complex descriptive geometries into groups of quantitative cells. Traditionally, analyses have used administrative boundaries as units [13,24] or focused on single land-use functions [25]. The former reinforces political divisions along bureaucratic lines, while the latter overlooks the dynamic interactions between land-use functions—both approaches fail to address integrative, systematic strategies. In contrast, the cell-based approach enables a comprehensive understanding of Java Island, reflecting regional urbanisation patterns [7].

Selecting data sources for land use classification in Indonesia requires balancing official, open-access datasets with supplementary sources to address data gaps and enhance spatial detail. The Indonesia Geospatial Portal, Ina-Geoportal, serves as the official national platform providing open-source land use data, widely used for baseline mapping and policy support. However, national datasets may have limitations in spatial resolution, update frequency, or thematic detail, especially in heterogeneous or rapidly changing landscape [26]. Supplementary spatial datasets, including buildings and infrastructure networks, were sourced from OpenStreetMap (OSM) and the European Environment Agency (EEA). OSM provides extensive, up-to-date, and globally crowdsourced geospatial data on buildings, infrastructure, and land use. Its open-access nature and high spatial granularity make it valuable for supplementing official datasets, especially where government data are incomplete or outdated. OSM is increasingly used in Indonesia for extracting road networks, building footprints, and other infrastructure, often outperforming some official datasets in urban and peri-urban areas [27]. EEA data are recognised for their thematic consistency and are often integrated with OSM and satellite imagery to enhance classification accuracy and cross-validate results [28].

As mentioned, land use integration as cultural (red, R), agricultural (green, G), and natural (blue, B) systems must be combined into a single model. Through five iterative trials, the resolution and legibility of the cluster patterns were calibrated and optimised, in a process that strategically accommodated the constraints of limited geospatial data availability. Initial principal datasets included buildings, tree coverage, and waterways. To enhance clustering resolution, additional variables—demography (population), infrastructure (road networks), and natural geography (elevation and slope)—were incorporated into the final RGB-cluster model. These ancillary variables reflect Central Java’s landscape conditions and closely correspond to local agricultural practices. Table 1 provides a detailed description of the RGB variables.

Table 1.

Variables classified for the RGB-cluster model.

In order to proceed with the clustering analysis, the RGB variables were converted into a pixel grid with a 1 km resolution. A 1 km grid is commonly used in regional and urban studies because it balances spatial detail with computational efficiency. It is fine enough to capture meaningful landscape heterogeneity, such as settlement density or land use variation, yet coarse enough to avoid excessive noise, which can result in computational challenges [29]. As the 1 km scale is widely adopted in global and regional land use, ecological, and urban studies, there is also a higher possibility to facilitate comparisons with other research and datasets.

Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) was applied to capture the geographical concentration of each variable, which is a widely used method to generate the density surfaces for various spatial variables, enabling the identification of clusters and spatial patterns [30]. To enable comparability, raster surfaces were rescaled and normalised between 0 and 1 as preprocessing step. While normalisation is commonly applied to many spatial variables, population and elevation data is treated differently due to their unique statistical properties and interpretive role in spatial analysis [30,31,32]. Additionally, slope—derived from elevation—was reclassified into a scale from 1 to 5 according to an optimised natural classification. This process transforms continuous slope values into discrete categories, making it easier to interpret terrain effects on land use, erosion risk, or agricultural suitability [33].

2.2.3. Spatial Typological Analysis Using Two-STEP Clustering

Cluster analysis is an exploratory statistical method used for classification problems, often referred to as typological analysis. It visualises spatial patterns based on similarities or ‘distances’ between observations. Traditionally, distance-based cluster analysis applies to quantitative (continuous) variables. However, recent studies increasingly incorporate mixed data types, including qualitative (categorical) variables, necessitating appropriate new methods. The two-step clustering procedure in IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 25.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) is specifically designed for such mixed-type datasets, making it suitable for typological analysis in heterogeneous datasets [34]. It automatically determines the optimal number of clusters, though the final decision can be guided by the researcher.

Seven clusters were delineated with the validation against traditional territorial interpretations using high-resolution aerial imagery data in order to ensure they reasonably captured the defining characteristics of the desakota of Central Java. Field-based point verification conducted for the Metro Java 2045 project further confirms that the clusters accurately reflect the distinct land use types. While the initial choice of parameters was constrained by the limited public availability of large spatial datasets, these comparisons seem to substantiate the validity of the initial model in describing conditions on the ground.

2.2.4. Scale Change to the Meso Level

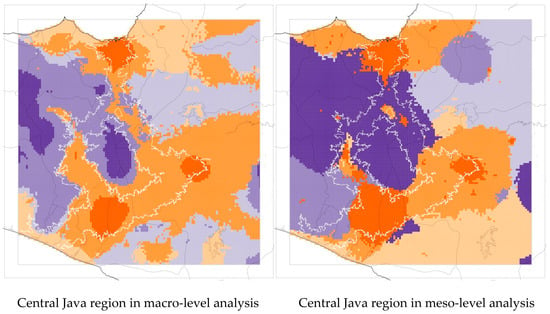

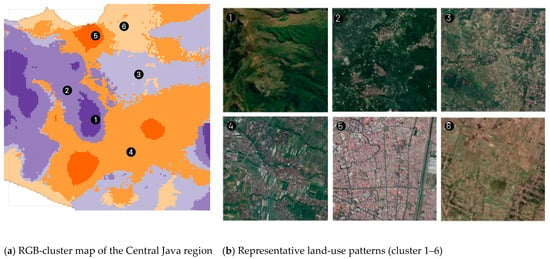

Central Java, the study area for the overarching Metro Java 2045 project, is undergoing widespread urban transformation [13]. A key government initiative is upgrading the road system into a Semarang-Yogyakarta tollway network, potentially forging a future urban belt. Our regional-scale cluster analysis for Central Java reveals an embedded pattern that broadly coincides with the project’s explored ‘one-hour city’ corridor, indicated by the white contour line in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The comparison of different scales of analysis. The number of clusters—six—is identical at both levels. Note. The colours serve only as a comparison of the different resolutions of each pattern. The white outline refers to a one-hour travel corridor simulated in a parallel study [21].

However, when the analysis is narrowed to the meso level, the altered resolution changes the land use clusters. For instance, mountain areas and villages consolidate into a single cluster, while urban cores expand territorially. At the macro level, Cluster 4 (dispersed urbanisation) exhibits a cyclical contiguity that aligns with the one-hour travel corridor. While this ring structure does not appear at the meso level, a trait of contiguity persists along the western segment where urban areas agglomerate. This intriguing multi-scalar correlation will be further explored to formulate an alternative development vision and planning strategy for the region.

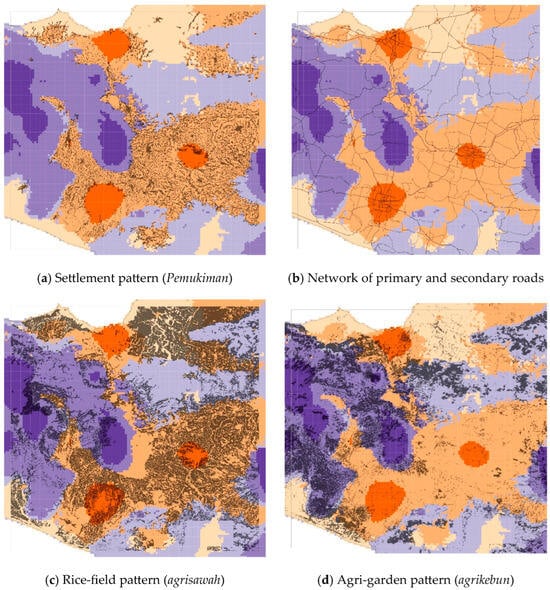

2.3. Contiguousness as a Benchmark for Land Use Integration

As the cluster maps reveal (Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7), Central Java functions as a cohesive landscape system composed of six discrete land use typologies. To benchmark spatial strategies within this system, we introduce “contiguousness”—a metric capturing shared land-use territories’ size, cohesion, and integrity. This concept offers a vital lens for assessing land-use integration. Larger, connected tracts are presumed to enhance regional resilience and productivity more effectively than fragmented parcels. This principle applies across the RGB spectrum: urban systems (R) benefit from a sustained compactness; productive landscapes (G) become more profitable and manageable, also when enabling collective stewardship; and natural systems (B) support larger, more robust biotopes and wildlife corridors. Consequently, adopting contiguousness as an evaluative benchmark provides a novel, quantitative lens for interpreting cluster maps and rigorously assessing spatial interventions across scales. It is a critical tool which, while requiring further mathematical nuance, has the potential to furnish an objective framework for regional planning strategy assessment writ large.

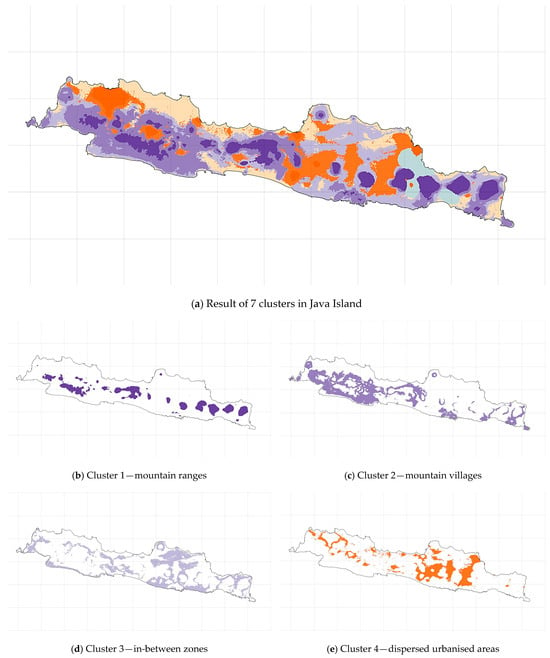

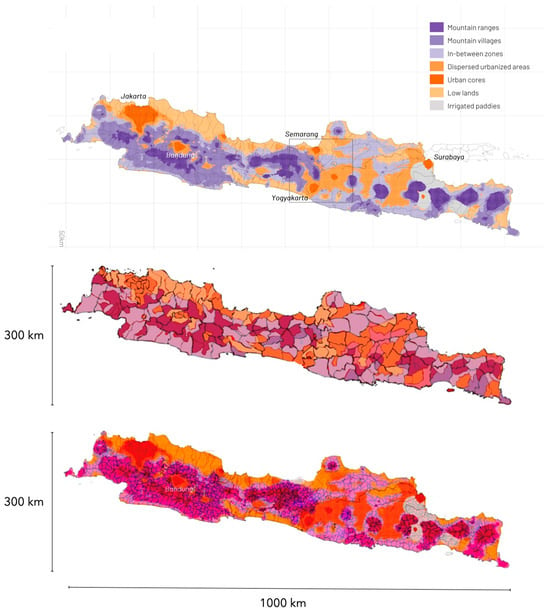

Figure 5.

Results of the RGB cluster model at the macro level. Panel (a) shows the spatial distribution of the seven land-use clusters across Java, while panels (b–h) display each cluster individually. Different colours represent different clusters (1–7), and the same colour denotes the same cluster in all panels. The background grid has a spacing of 100 km.

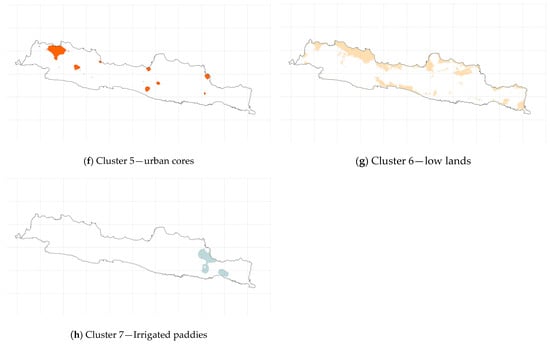

Figure 6.

Zoom-in of the Central Java region. (a) RGB-cluster map, where colours indicate different land-use clusters (same colour scheme as in Figure 4). (b) Land-use patterns illustrated by representative satellite images for each cluster: (1) mountain ranges; (2) mountain villages; (3) transitional zones at the urban–rural fringe; (4) dispersed urbanised areas within the agricultural matrix; (5) compact urban cores; (6) lowland plains. Satellite images (1–6) show representative local morphologies from the corresponding clusters within the watershed (source: Google Maps).

Figure 7.

RGB-cluster map of the Central Java region overlaid with different land-use layers shown in black. Background colours represent the six land-use clusters (same colour scheme as in Figure 4); The overlays indicate that rice fields are largely concentrated within cluster 4 (orange, representing dispersed urbanisation areas), whereas agricultural gardens occur predominantly within cluster 2 (purple, representing mountain villages).

3. Results: A Cluster-Based Land Use Taxonomy for Java

3.1. A New Land Use Taxonomy

The results of the clustering analysis are presented in Figure 5 and Figure 6. The map reveals seven land-use patterns characterised by mixtures of the RGB landscape components, and the synthesis of population density with natural factors like elevation and slope reflects a clear gradient from desolate mountain peaks to compact, bustling urban cores.

The clusters are defined as follows:

- Cluster 1: Mountain ranges—This cluster represents the volcanic mountainous area, distinguished by high tree coverage, elevation, and slope.

- Cluster 2: Mountain villages—This cluster depicts villages located along the ridges of the highlands.

- Cluster 3: In-between zones—These consist of relatively undeveloped areas between larger clusters, with a low density of primary roads.

- Cluster 4: Dispersed urbanised areas—This cluster ranks second highest in population and road network density but differs more markedly from the urban cores; it is characterised by a high concentration of waterways, indicating a predominantly agricultural land use.

- Cluster 5: Urban cores—This cluster corresponds to urban cores, exhibiting peak values in population density and road networks, and encompasses major centres such as Semarang, Yogyakarta, Klaten, and parts of Magelang.

- Cluster 6: Low lands—Located mostly along Java’s coastline, this cluster shows the lowest elevation and slope values, overlapping with the alluvial plain.

- Cluster 7: Irrigated paddies—This cluster predominantly contains the irrigated rice paddies concentrated in eastern Java.

3.2. Seven Clusters

The selection of seven clusters represents a deliberate calibration that balances statistical fit with geographical interpretability, acknowledging the inherent methodological discretion in such analyses. The average land-use composition of each cluster is summarised in Table 2. While the algorithm suggested a viable range, the final number was validated as it provided the optimal resolution to meaningfully differentiate Java’s landscape into functionally coherent socio-ecological systems—such as watersheds, contiguous agricultural plains, and dispersed urbanising belts—defined by shared environmental vulnerabilities. We fully acknowledge that this configuration is not an absolute truth; the “optimal” cluster solution is inherently purpose-dependent, and studies focused on different objectives would justifiably yield alternative results. The validity of our seven-cluster model is therefore grounded not in universality, but in its specific utility for bridging macro-level policy with local action, providing a strategically viable taxonomy for cross-boundary environmental governance.

Table 2.

The average value of land-use composition for each cluster.

3.3. Connectivity and Development Potential by Cluster

Analyses of population and road density reveal patterns of current urbanisation and future growth potential. While large-scale infrastructure in developing nations can drive regional development and alleviate poverty [35,36], its effects are multifaceted. Table 3 presents these density statistics by cluster.

Table 3.

The statistical summary of population and road networks for each cluster.

The two extremes—Cluster 5 (urban core) with the highest densities and Cluster 1 (mountainous area) with the lowest—are excluded from this detailed analysis. The data shows that Clusters 3 and 6 exhibit high primary road network per capita (0.232 and 0.214), indicating strong macro-level accessibility and potential for industrial clustering, albeit with a risk of landscape fragmentation. Conversely, Clusters 4 (dispersed urbanisation) and 5 show dense residential street networks, suggesting vibrant local activity and high potential for social interaction.

Strategic opportunities become apparent, for instance linking these cluster types—connecting macro-accessibility with local vibrancy—to empower grassroots communities and foster multi-stakeholder participation in the region’s development.

3.4. Communities, Contours, and Constituencies

3.4.1. Historic Alignment

The intricate adaptation of Java’s traditional agricultural communities is a direct consequence of the island’s volatile topography and micro-climates, a relationship fundamentally configured by the forces that have shaped the desakota. This hybrid rural-urban tapestry is historically fine-tuned to its geographic imperatives, establishing a patchwork of hyper-specialised agrarian communities that have adapted their deeply rooted agricultural logic to the complex realities of hydrological gradients, light and slope angles, forests, soil types, etc.—as encapsulated by RGB.

The socio-agrarian structure of a village in the steep, volcanic highlands of Priangan was fundamentally different from one in the flat, alluvial plains of northern Central Java. Highland communities developed intricate terracing systems for rain-fed agriculture, cultivating crops like vegetables and robust upland rice varieties, often within communal forest gardens (talun or pekarangan). Their social organisation was adapted to managing complex, gravity-fed water channels and maintaining shared slopes. In contrast, lowland communities on the plains developed sophisticated, collectively managed technical irrigation systems for wet-rice cultivation (sawah). This required a different form of social cooperation, often organised around water user associations, to allocate flows and maintain canals. These were not just different crops, but entirely different cultural and governance systems born from the land itself.

The contemporary desakota condition has not erased this geographic determinism but has complicated it, forcing a radical adaptation of traditional practices. It layers new metabolic and economic pressures onto them, forcing communities to adapt their deeply rooted agricultural logic to a new, fragmented reality. As the desakota absorbs villages into extended metropolitan economies, the logic of the land collides with the logic of global supply chains. A farmer on a fertile, well-irrigated plain may be compelled to shift from rice to high-value, non-food commercial crops like ornamentals for urban markets, fundamentally altering the local water and nutrient cycle. Conversely, a community in a less accessible, sloped desakota zone might find its traditional mixed-garden system devalued, its land fragmented by speculative housing plots or small-scale industries that pay no heed to the underlying soil quality or erosion risk. The traditional, place-specific knowledge is not lost, but is often supplanted or hybridised by the need for immediate cash flow, leading to unsustainable practices like the overuse of pesticides on these new, market-driven monocultures.

Ultimately, the contemporary desakota represents a fierce negotiation between enduring geographic realities and transformative urban pressures. The resilience of these landscapes now depends on whether planning can recognise and work with this nuanced legacy. The inherent specialisation of the land—where certain slopes are best for tree cover, specific soils for rice, and well-drained terraces for homesteads—is being overwritten by a generic, plot-by-plot urbanisation. This creates a profound spatial contradiction: the desakota’s functional strength lies in its interconnectedness, yet its current transformation is driven by insular, disconnected decisions. Preserving the adaptive intelligence of Java’s agricultural communities, therefore, requires a planning model that sees these functional territories—the watersheds, the soil types, the historic striations of land use—as the essential framework for guiding development, rather than allowing them to be casualties of it.

3.4.2. Bridging Agency and Space Through Functional Land Use Analysis

The RGB-cluster analysis directly addresses this disjuncture by adhering to the very landscape logic that forged Java’s historic settlement patterns. It does not impose an external geometry but distils the functional territories—the cohesive socio-ecological systems—that have always existed but are now obscured and, arguably, complicated by political borders. This is the critical link: the clusters close the gap between the spheres of administrative agency and the spaces of their inherent solutions. By defining regions based on shared topographic, hydrological, and land-use characteristics, the model identifies the natural constituencies for collaboration. A watershed, a contiguous agricultural plain, or a dispersed urbanising belt, once mapped as a single cluster, becomes an undeniable visual and analytical argument for coordinated action. It creates a rational framework where the ‘sphere of agency’ for a group of villages or regencies can be purposefully aligned with the ‘space of the solution’—be it integrated water management, preserving a productive agricultural landscape, or coordinating infrastructure for a decentralised urban belt. The analysis thus moves beyond diagnosis to provide a blueprint for governance that is inherently more closely aligned to the spatial problems at hand.

3.4.3. Boundary Comparisons—From Functional Analysis to Political Constituencies

Spaces defined by a single land-use logic consistently transcend political boundaries. Our RGB cluster analysis reveals an immediate and critical discrepancy between these administrative units and the functional territories they purport to govern. Consequently, any regional strategy confined to regency (kabupaten) or district (kecamatan) boundaries is arbitrarily—and often detrimentally—truncated.

The path to implementation, however, lies not in supplanting the political landscape, but in mediating between it and the socio-ecological systems the clusters reveal. While the cluster offers a data-driven interpretation of the landscape’s inherent logic, the political apparatus—specifically the more granular district level—provides the essential administrative scale for actionable governance. Individual districts may be too small to constitute a functional territory alone, but their modular nature is their strength, offering the flexibility needed to assemble them into coherent, cluster-aligned spaces of action.

3.4.4. Low-Hanging Fruit

While nation-wide strategies can be construed purely on comprehensive land-use cluster maps without the need for a dramatic overhaul of the existing political spatial frameworks, the regional and local scales demand a practical response. Selected groupings of adjacent districts can be configured into new, pragmatic alliances that align closely with the shapes of the functional land-use patterns identified by the clusters. This approach directly engages with the distinct planning mandates of Indonesia’s political units. The regency (kabupaten) operates at a strategic, regional scale, possessing the fiscal and administrative authority for broad land-use planning and infrastructure development. The district (kecamatan) functions as the critical intermediary, its mandate rooted in local coordination, service delivery, and understanding community-level dynamics. Therefore, a cluster representing a “dispersed urbanisation area” or a “contiguous agricultural plain” can be operationalised by forming a collaborative planning body comprising the relevant district heads and reporting to the involved regencies. This creates a constituency for action that is both ‘politically legitimate’ and ‘functionally coherent’.

A preliminary overlay analysis (Figure 8) confirms that specific combinations of districts and regencies can serve as this pragmatic intermediary spatial lens. This offers a scalable means to approximate functionally coherent territories, facilitating regional planning even where comprehensive geospatial models are unavailable. More importantly, it unlocks a tapestry of local and regional alliances. It carves out territories of collaboration where village, district, and regency officials are empowered to tackle distinctly shared problems—such as watershed management or agricultural value chains—within their cohesive socio-ecological environments. This finally aligns the spheres of political agency with the spaces of their inherent solutions.

Figure 8.

Land use cluster map overlaid with Java’s regency and districts. Top: the Land Use Cluster Map. Middle: The Cluster maps compared to Java’s Regencies. Bottom: The Cluster map compared to Java’s district boundaries.

4. Discussion

4.1. Disparate Approaches

The Metro Java 2045 study underscores that fluid regional-scale dynamics inherently challenge the bureaucratic silos of centralised planning and the rigid project-focussed templates of commercial ‘best practices.’ In response, an emerging interdiscipline fusing environmentalism and urbanism has produced a myriad of loosely connected methods, exemplified by compendiums such as Ecological Urbanism [37]. Amid this proliferation, a clear hierarchy of planning steps—and their relative impact over time—is lost.

We posit that land-use integration provides the critical framework for prioritising these disparate approaches. Land-use analysis and management are, by their very nature, foundational; they establish the physical and metabolic canvas upon which all other planning actions—be they economic, social, or infrastructural—must ultimately be inscribed. Given the finite—and increasingly contested—nature of land, its allocation must be central to any matrix balancing economic and environmental criteria. While this is an urgent imperative in emerging markets, it has become a global reality, as explosive land requirements for modern infrastructure—from renewable energy farms to data centres and resilience infrastructure—intensify competition for space. Consequently, land-use patterns offer a strategic lens to discern clear priorities amidst multiple urgencies. In short, land-use planning must be an urban planner’s primary concern.

This leads to a core methodological question: how can RGB-derived cluster maps practically advance multifaceted planning strategies to deliver measurably better land-use outcomes?

4.2. Doom-Dream

In response to this challenge, our contribution is twofold: a contextual analysis of Central Java’s urbanisation drivers, and a conceptual framework for benchmarking the land-use patterns distilled by our clustering analysis.

In emerging markets, where volatile land transformation is endemic, integrated land-use planning is both critically pertinent and potentially highly effective. Yet, strategic land-use integration remains conspicuously absent from mainstream planning agendas [38]. This omission raises two profound long-term concerns. First, as urban land-use patterns consolidate, they lock in energy-intensive metabolic flows and enforce a path dependency that determines long-term urban performance. Second, despite planning efforts, spatial fragmentation perpetuates as new projects stretch the circumference of the ever-expanding suburban periphery. As Alain Bertaud observes, cities exceeding five million inhabitants are prone to severe inherent fracturing along their edges [39]. Beyond this threshold, powerful regional dynamics dominate, making corrective interventions—such as effective public transit—increasingly difficult and less effective.

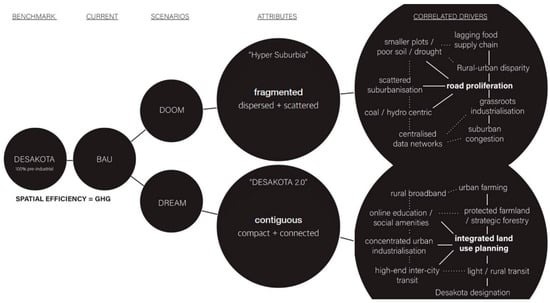

We contend that the future of Indonesia’s rural-urban continuum will be determined at the intersection of land-use integration and infrastructure development (Figure 9). For planners—beyond fiscal tools like taxation—it is the deployment of physical infrastructure that offers the most potent and direct lever to enact any spatial strategy. A binary doom-and-dream scenario elucidates the forces shaping the desakota beyond a business-as-usual trajectory. The ‘doom scenario,’ dominated by road proliferation, entails accelerated exurbanisation, the disruption of fragile land-use patterns, exponential urban fragmentation, splintered land parcels, and growing socioeconomic disparities.

Figure 9.

The pre-industrial desakota as a benchmark for dream and doom scenario. Solid lines indicate stronger conceptual correlations between elements, whereas dotted lines indicate weaker or indirect correlations.

Conversely, the ‘dream scenario’ envisions fostering contiguous land-use clusters to enhance regional resilience and productivity. This vision is premised on land-use integration as a strategy to manage Java’s diversifying peri-urban functions by promoting connected and coherent socio-ecological systems. Such “contiguousness” finds a historical precedent in the desakota’s distinct morphology, where land tracts manifest parallel “striations” of agriculture, forest, sawah, and industry—elongated bands of homogeneous land-use that enable robust productive landscape connectivity. In the Metro Java 2045 proposal, these striations are then intersected perpendicularly by minimal-impact foot and bike passages, facilitating efficient access across diverse functions without compromising spatial-ecological integrity.

Growing concerns for Java’s desakota indicate that integrated land-use management will likely become a policy priority. This paper’s conceptual model reframes the role of the desakota and the mesoscale, moving beyond their current function as a mere buffer zone for undirected growth. Instead, it positions them as the central arena for the dynamic interplay between land-use and infrastructure development. While infrastructure planning remains a pivotal tool for actualising regional strategies, this model approaches the two systems as complementary and interdependent topologies: land-use comprises extensive, dynamic surface typologies, while infrastructure consists of rigid, linear networks. It is their ongoing and fierce entanglement that will ultimately shape the future evolution of the desakota.

5. Conclusions

Indonesia’s desakota presents both profound challenges and paradigmatic solutions for planning in dynamic peri-urban regions, prevalent across Southeast Asia and other developing global territories. This landscape, which sustains city-level densities across a vast territory within a cohesive, productive rural fabric, epitomises a core planning dilemma: centralised schemas consistently fail to accommodate complex local socio-spatial geographies. Where urbanisation is driven more by informal ‘affordances’ than formal regulation, both top-down and bottom-up incentives risk eroding intrinsic landscape cohesion, underscoring the urgent need for integrated, land-use-focused planning.

In response, this research has presented an RGB-cluster model that maps functional territories at the mesoscale, bridging the gap between macro-level vision and micro-level collaboration. The model reveals a fundamental misalignment between political jurisdictions and functional socio-ecological systems. Its true utility, however, lies in its transferability. The methodology offers a replicable framework for other rapidly urbanising regions—from the Pearl River Delta to the Gangetic Plain—where similar rural-urban fusion and administrative misalignments are prevalent. The core innovation is its ability to generate a data-driven, yet interpretable, spatial lexicon. Planners can use these functional clusters to prioritise infrastructure investments, target environmental remediation, and design governance partnerships that align political agency with ecological reality.

Subsequent research will apply this methodology to mediate socio-spatial tensions within Java’s desakota. Documenting this implementation will be crucial for developing an evidence-based framework with applications for heterogeneous territories globally. The model’s ultimate contribution is its capacity to reframe the planning unit from a static political jurisdiction to a dynamic, functional constituency, offering a scalable approach to balance development pressures with the preservation of vital agricultural and ecological systems. In conclusion, this research celebrates the desakota as a vital, resolved planning paradox: a ‘theoretical loophole’ that refutes the doomed choice between planetary urbanisation’s fragmentation and global urbanism’s insular ideals. It stands as a living testament that dispersion, density, ecological sensitivity, and productivity can powerfully coincide.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, N.M.; Contextual research, A.W.; Data Curation, Y.B.; Formal Analysis, Y.B.; Funding Acquisition, N.M.; Investigation, Y.B. and N.M.; Methodology, N.M. and Y.B.; Software, Y.B.; Visualisation, Y.B.; Writing—Original Draft, N.M. and Y.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is part of a 3-year planning project by: MARS Architects/Dynamic City Foundation + Krill o.r.c.a., with UNDIP, Gajah Mada University, with support from Yogyakarta Heritage Society and the Ministry of Transportation of Indonesia. With generous support by the EFL Stichting and the Dutch Creative Industries Fund. For periodical updates: https://burb.info/view/Metro_Java (accessed on 15 March 2025).

Data Availability Statement

The input datasets used in this study are publicly available from OpenStreetMap, WorldPop, the European Environment Agency, GLAD, and Ina-Geoportal (see Table 1 for details). The processed datasets generated through kernel density estimation, 1-km grid aggregation, normalisation, and two-step clustering are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kinkaid, E. Re-encountering Lefebvre: Toward a critical phenomenology of social space. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2020, 38, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, N. The Urban Question: Reflections on Henri Lefebvre, Urban Theory and the Politics of scale. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2000, 24, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mars, N.; Hornsby, A. The Chinese Dream: A Society Under Construction; NAi010 Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Albrechts, L.; Balducci, A. Practicing strategic planning: In search of critical features to explain the strategic character of plans. Disp-Plan. Rev. 2013, 49, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A. Urban Informality: Toward an Epistemology of Planning. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2005, 71, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firman, T. The urbanisation of Java, 2000–2010: Towards ‘the island of mega-urban regions’. Asian Popul. Stud. 2017, 13, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilonoyudho, S.; Rijanta, R.; Keban, Y.T.; Setiawan, B. Urbanization and regional imbalances in Indonesia. Indones. J. Geogr. 2017, 49, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, T.G. The Extended Metropolis: Settlement Transition in Asia; Ginsburg, N., Koppel, B., McGee, T.G., Eds.; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 1991; The Emergence of Desakota Regions in Asia: Expanding a Hypothesis; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- McGee, T.G. Managing the rural–urban transformation in East Asia in the 21st century. Sustain. Sci. 2008, 3, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beall, J.; Guha-Khasnobis, B.; Kanbur, R. (Eds.) Urbanization and Development in Asia: Multidimensional Perspectives; Oxford University Press: New Delhi, India, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hudalah, D.; Winarso, H.; Woltjer, J. Peri-urbanisation in East Asia: A new challenge for planning? Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2007, 29, 503–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desakota Study Team. Re-Imagining the Rural-Urban Continuum: Understanding the Role Ecosystem Services Play in the Livelihoods of the Poor in Desakota Regions Undergoing Rapid Change; Institute for Social and Environmental Transition-Nepal (ISET-N): Kathmandu, Nepal, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Handayani, W. Rural-urban transition in Central Java: Population and economic structural changes based on cluster analysis. Land 2013, 2, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, S. Critical Reflections on Cities in Southeast Asia; Bunnell, T., Drummond, L., Ho, K.C., Eds.; Times Academic Press: Singapore, 2002; Troubling real estate: Reflecting on urban form in Southeast Asia; pp. 101–123. [Google Scholar]

- Metro Java 2045. Resume of Metro Java 2045 Export Workshop. Workshops, Metro Java 2045. 2021. Available online: https://pwk.ft.undip.ac.id/id/metro-java-2045-expert-workshop-kolaborasi-untuk-perencanaan-kawasan-borobudur-2045/ (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Adams, R.E. Tools for a Speculative Imperialism. Machines of Urbanization. 2018. Available online: https://rossexoadams.com/2018/08/28/tools-for-a-speculative-imperialism/ (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Adams, R.E. Natura urbans, natura urbanata: Ecological urbanism, circulation, and the immunization of nature. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2014, 32, 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, N. Implosions/Explosions; Jovis: Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Neuman, M. The Compact City Fallacy. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2005, 25, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R. Edgeless Cities: Exploring the Elusive Metropolis; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mars, N.; Pfaender, F. The Java Model: A time-weighted network analysis of the desakota. In Proceedings of the 14th Conference of the International Forum on Urbanism, Delft, The Netherlands, 25–27 November 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boo, Y.; Mars, N. The Java model: Unlocking heterogeneous rural landscapes through cluster-based land use analysis. In Proceedings of the 14th Conference of the International Forum on Urbanism, Delft, The Netherlands, 25–27 November 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyono, J.S.; Yunus, H.S.; Giyarsih, S.R. The spatial pattern of urbanization and small cities development in Central Java: A Case Study of Semarang-Yogyakarta-Surakarta Region. Geoplann. J. Geomat. Plan. 2016, 3, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchori, I.; Sugiri, A.; Maryono, M.; Pramitasari, A.; Pamungkas, I.T. Theorizing spatial dynamics of metropolitan regions: A preliminary study in Java and Madura Islands, Indonesia. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 35, 468–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshino, K.; Setiawan, Y.; Shima, E. Land use analysis using time series of vegetation index derived from satellite remote sensing in Brantas River watershed, East Java, Indonesia. Geoplann. J. Geom. Plan. 2017, 4, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi; Yowargana, P.; Zulkarnain, M.T.; Mohamad, F.; Goib, B.K.; Hultera, P.; Sturn, T.; Karner, M.; Dürauer, M.; See, L.; et al. A national-scale land cover reference dataset from local crowdsourcing initiatives in Indonesia. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biljecki, F.; Chow, Y.; Lee, K. Quality of crowdsourced geospatial building information: A global assessment of OpenStreetMap attributes. Build. Environ. 2023, 237, 110295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinenkugel, P.; Deck, R.; Huth, J.; Ottinger, M.; Mack, B. The Potential of Open Geodata for Automated Large-Scale Land Use and Land Cover Classification. Remote. Sens. 2019, 11, 2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaresi, M.; Halkia, M.; Ouzounis, G.K. Quantitative estimation of settlement density and limits based on textural measurements. In Proceedings of the 2011 Joint Urban Remote Sensing Event, Munich, Germany, 11–13 April 2011; pp. 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnier, A.; Finné, M.; Weiberg, E. Examining Land-Use through GIS-Based Kernel Density Estimation: A Re-Evaluation of Legacy Data from the Berbati-Limnes Survey. J. Field Archaeol. 2019, 44, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fafard, A.; van Aardt, J.; Coletti, M.; Page, D. Global Partitioning Elevation Normalization Applied to Building Footprint Prediction. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote. Sens. 2020, 13, 3493–3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawker, L.; Uhe, P.; Paulo, L.; Sosa, J.; Savage, J.; Sampson, C.; Neal, J. A 30 m global map of elevation with forests and buildings removed. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 024016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akıncı, H.; Özalp, A.Y.; Turgut, B. Agricultural land use suitability analysis using GIS and AHP technique. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2013, 97, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacher, J.; Wenzig, K.; Vogler, M. Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaftliche Fakultät, Sozialwissenschaftliches Institut, Lehrstuhl für Soziologie: Nürnberg, Germany, 2004; Arbeits- und Diskussionspapiere, 2004, 2nd corr. ed.; 23p. Available online: https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/32715 (accessed on 27 September 2020).

- Tambunan, T. SME development, economic growth, and government intervention in a developing country: The Indonesian story. J. Int. Entrep. 2008, 6, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetanah, B.; Ramessur, S.; Rojid, S. Does infrastructure alleviate poverty in developing countries. Int. J. Appl. Econom. Quant. Stud. 2009, 6, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafavi, M.; Doherty, G. (Eds.) Ecological Urbanism; Revised ed.; Harvard University Graduate School of Design: Cambridge, MA, USA; Lars Müller Publishers: Zurich, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghe, R.J.; Zondag, B. Challenges in Spatial planning for Java. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference IRSA: Political Economics of Regional Development, Bogor, Indonesia, 21–23 July 2009; IRSA: Bogor, Indonesia, 2009; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bertaud, A. Order Without Design: How Markets Shape Cities; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.