Abstract

As a typical arid region, the change in Xinjiang’s vegetation carbon footprint is crucial for assessing ecological restoration and resource allocation. This study analyzes the changes in the vegetation carbon footprint and its influencing factors in Xinjiang by employing a range of models, including Net Ecosystem Productivity (NEP), carbon emission fitting, carbon footprint analysis, and structural equation modeling (SEM). Furthermore, using the carbon deficit vegetation investment estimation method, we quantify the additional vegetation area and investment required for Xinjiang to achieve carbon neutrality. The results show the following: (1) Net Ecosystem Productivity (NEP) increased slowly, with six regions (Altay, Bortala, Bayingolin, Kizilsu Kirghiz, Tacheng, and Yili) contributing 66.95% of the total NEP, forming the main carbon sink. Meanwhile, carbon emissions rose significantly, coming largely from Urumqi, Changji, Kumul, and Karamay (61.31% of total emissions). (2) The carbon footprint expanded 3.44 times, from 30.41 × 104 km2 to 104.49 × 104 km2. Human activities were the main positive driver, while vegetation factors negatively influenced the carbon footprint. (3) Based on the 21-year average carbon deficit, achieving carbon neutrality in Xinjiang requires an estimated investment of USD 106.77 × 108 to expand cropland, woodland, and grassland by 8029 km2, 1710 km2, and 35,016 km2, respectively. Implementing vegetation expansion, improving carbon markets, and transforming carbon-source economies are essential to achieving the “double carbon” goal. This study clarifies regional carbon sources/sinks and supports the carbon neutrality strategy in arid ecosystems.

1. Introduction

Addressing global warming is a pressing issue for humanity, and the IPCC (2018) states that in order to avoid extreme hazards, it is crucial to limit global warming to no more than 1.5 °C [1]. China’s high carbon emissions, coming from the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter, have a significant impact on global climate concerns, which not only places enormous international pressure on China, but also represents a bottleneck for China’s economic development. Since 2010, China has been committed to addressing climate change through a robust dual-control mechanism for carbon emissions. By controlling both the total amount and intensity of emissions, and by pushing for a disconnection between carbon emissions and energy consumption, the government is actively pursuing its low-carbon development objectives.

As an internationally recognized quantitative tool for carbon emissions, the carbon footprint serves as a critical metric for tracking greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions throughout a product’s entire life cycle. It systematically elucidates the core mechanisms by which human activities impact the climate system. Currently, there are two primary perspectives on the carbon footprint. The first defines it as the total amount of greenhouse gases emitted directly or indirectly by a specific activity or entity [2,3]; the other perspective views the carbon footprint as the vegetation area required to absorb these carbon emissions [4,5]. The former approach focuses on assessing the quantity of carbon emissions at each stage of a product’s or activity’s entire life cycle. In contrast, the latter systematically measures the area of terrestrial vegetation ecosystems needed to sequester these emissions. This study adopts the second concept to investigate the carbon footprint of Xinjiang. Current research on carbon footprints, both domestically and internationally, primarily focuses on three aspects: their quantification, spatiotemporal patterns, and influencing factors. Relevant studies indicate that China’s carbon footprint has shown a year-on-year increasing trend [6]. Concurrently, it exhibits a spatial pattern of being higher in the north and lower in the south [7,8]. Factors such as energy structure, level of economic development, and technological development have been found to significantly influence the spatial variation in carbon footprints [9,10]. Furthermore, it has been suggested that their level can be curbed by reducing political and financial risks [11,12,13] and increasing the use of clean energy [14]. Moreover, with respect to the objects of study, investigations have assessed the ecological repercussions of carbon emissions through analyses of the breadth and profundity of carbon footprint [15]. The scope of such research encompasses the carbon footprints of disparate products and industrial sectors [16], exemplified by the discovery of evolutionary trends in the carbon footprint of food consumption [17]. From a methodological standpoint, the principal analytical instruments comprise Input–Output Analysis (IOA) [18], Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) [19], and the Logarithmic Mean Divisia Index (LMDI) [20]. Illustrative applications include the construction of energy-consumption-based carbon emission models using the IPCC methodology to investigate industrial spatial carbon footprints [21], the utilization of input–output models (MIRO) for the accounting of private-consumption-induced carbon footprints [22], and the estimation of various crop carbon footprints via LCA, which furnish a theoretical foundation for the green transformation of conventional cultivation systems [23,24]. Furthermore, some studies have combined Input–Output Analysis with LCA to measure the carbon footprints of various regions in China and to analyze inter-regional carbon transfers [25,26]. In the research on the spatiotemporal distribution of regional carbon footprints, most studies have concentrated on exploring spatial correlations, while the underlying driving factors have been insufficiently investigated. Therefore, future research needs to further delve into the causes of carbon footprint changes and explore feasible carbon reduction implementation methods.

Although previous research on carbon footprints has led to considerable progress in this field, studies concerning mainland China, and particularly Xinjiang—the country’s largest provincial-level administrative region and a typical arid zone worldwide—are notably scarce. While we have previously assessed the capacity of Xinjiang’s vegetation to offset regional emissions [27], a quantitative assessment of the precise vegetation area required to achieve carbon neutrality is still lacking. Many studies analyzing carbon footprints primarily focus on carbon emissions from energy consumption, often neglecting those from other production activities. This limitation can lead to an assessment of only partial carbon neutrality outcomes. Therefore, this study utilizes annual Net Ecosystem Productivity (NEP) data from 2000 to 2020 to represent the carbon sequestration level of vegetation in Xinjiang. We integrate this with total carbon emission data from all human activities, including industry, agriculture, and tourism, to calculate the region’s carbon footprint. Subsequently, we analyze its spatiotemporal variations and driving factors, and investigate the monetary investment in vegetation required for Xinjiang to achieve carbon neutrality. The research aims to explore a viable pathway toward a carbon neutrality strategy for arid-zone ecosystems, thereby providing a practical case study and a scientific reference for formulating refined carbon reduction policies for the world’s arid regions to meet their “dual-carbon” goals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

Xinjiang is located on the northwestern border of China (73°40′–96°18′ E, 34°25′–48°10′ N), with a total area of one-sixth of China’s land area and 14 prefectures and cities (Figure 1). The top five regions with regard to economic development in terms of GDP in 2023 are the five regions of Urumqi, Changji, Aksu, Yili, and Bayingolin, accounting for about 56.71% of Xinjiang’s total GDP, while the remaining nine regions account for about 43.21% of the GDP. The terrain is dominated by plateaus, plains, and basins. Vegetation types include forests, grasslands, and desert vegetation. The climate type is a temperate continental arid climate, with low and uneven distribution of precipitation, with an average annual precipitation of about 170 mm, long sunshine hours, high evaporation, low vegetation cover, hot summers, and cold winters. The land is extremely sandy and desertified, and the ecological environment is fragile. The proportions of area occupied by each land-use type (arable land, forest land, grassland, and other land) in Xinjiang are about 6.29%, 2.01%, 21.66%, and 70.04%, respectively. Xinjiang’s energy content is rich and diverse, with coal, oil, and natural gas reserves proven to be among the most abundant in the country. Relying on energy to drive the rapid development of urbanization and industrialization, the process of economic development has brought about huge carbon emissions and highlighted environmental problems, and there is an urgent need to shift to a green, low-carbon, and sustainable development model. With the intensification of human activities and economic development, the intensity of land use in Xinjiang has been increasing, which has placed great pressure on the ecological environment, and it is of great significance to explore the carbon footprint of vegetation in Xinjiang by using the NEP and carbon emission data of Xinjiang to achieve the regional “double carbon” strategic goal.

Figure 1.

Overview of the study area.

2.2. Data Sources

Remote sensing data, meteorological data, human footprint data, land-use data, and administrative district vector boundary data were used in this study (Table 1). Among the remote sensing data, the MODIS NPP annual data were downloaded from the MOD17A3HGF product provided by the GEE platform, with a spatial resolution of 500 m and a temporal resolution of years. Meteorological data, including precipitation and temperature, were provided by the Resource and Environment Science Data Platform of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, with a spatial resolution of 1 km. Human Footprint Data were obtained from the annual human footprint dataset for the global landmass mapped by the Remote Sensing of Agriculture and Land group using eight variables reflecting human pressures, with values ranging from 0 to 50, where the higher the value, the more frequent the human activity. Carbon emissions data were obtained from the China Urban Greenhouse Gas Working Group. The nighttime lighting data were obtained from the National Earth System Science Data Sharing Service Platform. Land-use data were obtained from the China 30 m land use dataset, and the vector data of the study area were obtained from the Sky Map Service Center. To ensure the consistency of spatial resolution, all raster data were resampled to 1 km.

Table 1.

Data sources.

2.3. Research Methodology

2.3.1. NEP Calculation

NEP is often used to describe the dynamics of carbon balance in a region, which can indicate the carbon balance of plants per unit area per unit time; in addition, it can be used not only as a key factor to measure the activity of vegetation, but also to characterize the health and carbon sequestration capacity of vegetation [28], and it can be used to characterize carbon sequestration in terrestrial and atmospheric ecosystems without considering other natural and anthropogenic factors. NEP > 0 indicates that vegetation sequesters more carbon than is emitted by soil heterotrophic respiration (Rh), manifesting as a vegetation carbon sink. Conversely, NEP < 0, indicating that the ecosystem is a carbon source. The formula is as follows:

where NEP(x, y), NPP(x, y), and Rh(x, y) are the vegetation Net Ecosystem Productivity, vegetation net primary productivity, and soil respiration on image element x in year y, all in g C m−2 yr−1.

In this paper, soil heterotrophic respiration Rh was indirectly estimated from air temperature and precipitation using the empirical formula established by [29]. Validation has been performed to show that this equation can be used to monitor soil heterotrophic respiration in Xinjiang [27,30]. The formula is as follows:

In Equation (2), T refers to mean annual temperature (°C); R refers to annual precipitation (mm); and Rh is total annual soil heterotrophic respiration (g C m−2 yr−1).

2.3.2. Carbon Emission Fitting Models

Carbon emission fitting models were constructed for each of the 14 regions in the study area by establishing the relationship between nighttime lighting values and carbon emission statistics [31]. In this paper, the nighttime lighting data from 2000 to 2020 are used as the basis for counting the total value of nighttime lighting in 14 regions of Xinjiang, and carbon emission data with the corresponding years are available to establish a fitting model to obtain carbon emission values of 14 regions for the years with missing data, so as to obtain carbon emission data of the whole study area for the consecutive 21 years from 2000 to 2020. The formula is as follows:

where Cmn denotes simulated carbon emissions, DNt is total value of nighttime light brightness, and f denotes the regression coefficient.

2.3.3. Carbon Footprint and Vegetation Investment Estimates

Carbon footprint was assessed from a dual-system perspective, encompassing both natural and socio-economic systems. The carbon sequestration of the natural ecosystem was quantified using the NEP. The total carbon emissions from the socio-economic system were calculated as the sum of emissions from human activities, primarily including industry, agriculture, and tourism, and the area of productive vegetation was extracted from land-use data. Referring to relevant studies [8,32,33], we constructed the following equations for carbon footprint measurement and estimation of the investment in vegetation required to achieve carbon neutrality:

where CFmf is the carbon footprint of region m in year f (km2); CTmf is the total carbon emission of region m in year f (104 t/yr); Smf is the vegetation area of region m in year f (km2); NEPmf is the total carbon sequestration by vegetation in region m in year f, i.e., the total amount of NEP (104 t/yr); CBImf is the carbon footprint pressure index; ΔCFmf denotes carbon deficit (km2); and Dv denotes the investment budget for planting a unit area of vegetation (104 USD/km2). Referring to relevant documents of Xinjiang Department of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, we determined that the cost of investing in the construction of cropland, woodland, and grassland is 63 × 104, 42 × 104, and 14 × 104 USD/km2, respectively [34], and PL denotes total amount of investment in vegetation.

2.3.4. Structural Equation Models

This method is based on the researchers’ a priori knowledge of the pre-set dependencies between the factors in the system, the ability to discern the strength of the relationship between the factors, and the ability to fit and judge the overall model. Structural equation modeling consists of two parts: the measurement model and the structural model [35]. The formula is as follows:

where X denotes the vector of exogenous measured variables, Λx denotes the factor loading matrix of X on ξ, ξ denotes the exogenous latent variable, δ denotes the error term of the exogenous indicator, Y denotes the vector of endogenous measured variables, Λy denotes the factor loading matrix of Y on η, η denotes the vector of endogenous latent variables, and ε denotes error term of the endogenous indicator. B denotes the matrix of the coefficients of the paths of the effect between the endogenous latent variables, Г denotes matrix of the paths of the effect of the exogenous latent variables on the path coefficient matrix of the endogenous latent variables, and ζ denotes the residual term of the structural equation.

X = Λxξ + δ

Y = Λyη + ε

η = Bη + Γξ + ζ

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Analysis of Spatial and Temporal Changes in Carbon Sequestration and Carbon Emissions

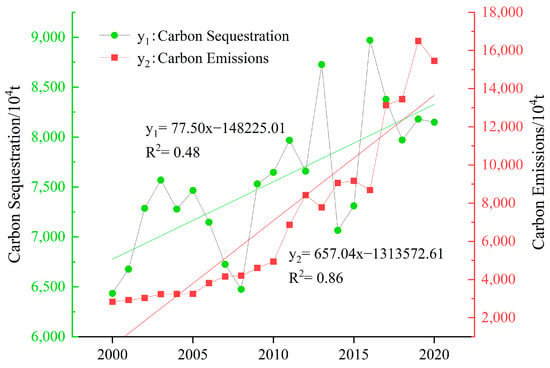

From Figure 2, total annual NEP of vegetation in Xinjiang from 2000 to 2020 showed a slow upward trend, with the annual total NEP fluctuating and increasing from 6434.45 × 104 t in 2000 to 8149.66 × 104 t in 2020, with an average annual growth rate of 1.19%, and an average annual growth of 77.50 × 104 t yr−1. The smallest value of this was in 2000 at 6434.45 × 104 t, and the highest value occurred in 2016 at 8970.76 × 104 t. In summary, the annual total NEP of the vegetation in Xinjiang in the past 21 years, despite the fluctuation, showed a more significant increasing trend, indicating that the carbon fixation capacity of the vegetation in Xinjiang is increasing. It can also be seen that from 2000 to 2020, Xinjiang’s carbon emissions show a significant growth trend. The total carbon emissions in Xinjiang grow from 2836.08 × 104 t in 2000 to 15457.91 × 104 t in 2020, with an average annual growth rate of 8.84%, and an average annual growth of 657.04 × 104 t. Changes in total carbon emissions can be roughly divided into two stages, with a slow increase in carbon emissions between 2000 and 2010, with total carbon emissions growing from 2836.08 × 104 t in 2000 to 4941.98 × 104 t in 2010, with an average annual growth rate of 5.75%. Carbon emissions increased significantly between 2011 and 2020, with total carbon emissions growing from 6870.19 × 104 t in 2011 to 15,457.91 × 104 t in 2020, with an average annual growth rate of up to 9.3%, especially during the period of 2016–2020, indicating that Xinjiang’s economy is entering a stage of high-speed development, while also facing the serious challenge of energy consumption and carbon emission management.

Figure 2.

Trends in carbon sequestration and emissions in Xinjiang from 2000 to 2020.

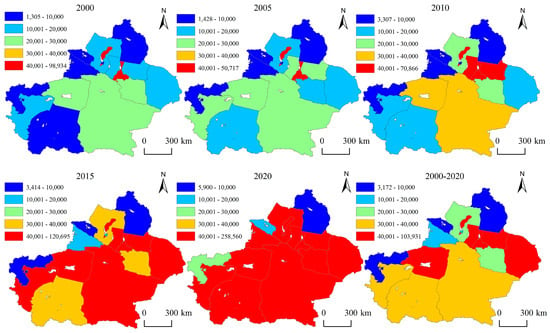

3.2. Spatial Changes in Carbon Footprint

As shown in Figure 3, the carbon footprints of 14 cities in Xinjiang exhibited an overall increasing trend, to varying degrees, from 2000 to 2020. These changes can be classified into three distinct patterns. First, Altay, Urumqi, and Turpan were classified as the slow-increase type, with their carbon footprints rising from 0.14, 6.18, and 2.27 × 104 km2 in 2000 to 0.59, 7.91, and 4.43 × 104 km2 in 2020, respectively. Second, ten cities—Aksu, Bayingholin, Bortala, Changji, Hotan, Hami, Kashgar, Kizilsu Kirgiz, Tacheng, and Yili—belonged to the significant-increase type, with their carbon footprints escalating from 2.64, 2.19, 0.13, 1.71, 0.35, 1.08, 1.87, 0.20, 1.32, and 0.41 × 104 km2 in 2000 to 9.11, 6.17, 1.79, 25.86, 11.05, 16.24, 6.14, 2.43, 4.11, and 4.26 × 104 km2 in 2020, respectively. Third, Karamay was the only city that exhibited a slow-decrease type, with its carbon footprint declining from 9.89 × 104 km2 in 2000 to 4.39 × 104 km2 in 2020.

Figure 3.

Spatial and temporal changes in carbon footprint in Xinjiang from 2000 to 2020.

Overall, the total carbon footprint in Xinjiang showed a significant growth trend, increasing from a total area of 30.41 × 104 km2 in 2000 to 104.48 × 104 km2 in 2020, representing an approximate 3.44-fold increase. Spatially, the carbon footprint distribution in Xinjiang was notably heterogeneous. Although the total footprint was generally larger in the northern part than in the southern part, the growth rate in the southern region was significantly faster than that in the northern region.

3.3. Calculation of Carbon Deficit and Vegetation Investment Required to Mitigate It

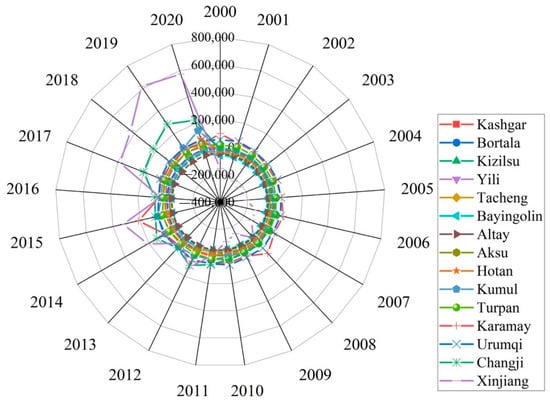

From the change in carbon deficit in Xinjiang from 2000 to 2020 (Figure 4), it can be found that Changji Prefecture has the highest level of carbon deficit among all the cities and municipalities in Xinjiang, with the average value of carbon deficit for many years being 6.74 × 104 km2, and the carbon deficit for the rest of the cities are, from highest to lowest, Karamay (6.30 × 104 km2), Urumqi (5.72 × 104 km2), Kumul (2.72 × 104 km2), Turpan (2.02 × 104 km2), Aksu (0.60 × 104 km2), Hotan (0.15 × 104 km2), Kashgar (−0.14 × 104 km2), Bortala (−1.02 × 104 km2), Kizilsu Kirghiz (−2.51 × 104 km2), Yili (−3.29 × 104 km2), Tacheng (−3.69 × 104 km2), Bayingolin (−4.55 × 104 km2), and Altay (−4.56 × 104 km2). The average carbon deficit of Xinjiang cities during the study period shows that seven cities are in carbon deficit, among which three cities, namely Karamay, Urumqi, and Turpan, have always been the main carbon source areas, and four cities, namely Changji, Kumul, Aksu, and Hotan, have been changed from carbon sinks to carbon sources. In particular, the carbon emissions of Changji Prefecture have surpassed those of Urumqi since 2010, making it the primary carbon source area in Xinjiang. There are seven cities in carbon surplus, including Altay, Bayingolin, Tacheng, Yili, Kizilsu Kirghiz, and Bortala, and they are the major carbon sinks in Xinjiang. And Kashgar was transformed from a carbon sink to a carbon source area after 2013. The carbon deficit in Xinjiang as a whole increased from −15.54 × 104 km2 in 2000 to 57.44 × 104 km2 in 2020, with an average annual carbon deficit of 4.47 × 104 km2 over the study period, suggesting that Xinjiang is showing a transition from a carbon surplus to a carbon deficit. The carbon emissions from 2000 to 2011 did not exceed the carbon sequestration capacity of Xinjiang vegetation ecosystems, and vegetation in Xinjiang can reach carbon neutrality; from 2012 to 2020, Xinjiang was in a carbon deficit all year round, indicating that the vegetation NEP in Xinjiang is not enough to offset the carbon emissions in the whole region, and vegetation in Xinjiang is in an overloaded state.

Figure 4.

Changes in carbon deficit in Xinjiang from 2000 to 2020.

From Figure 5 below, we can obtain the annual average budget for investment in vegetation needed to achieve carbon neutrality in Xinjiang as a whole and in cities in each region from 2000 to 2020; it shows that the vegetation in Altay, Bayingolin, Bortala, Kashgar, Kizilsu Kirghiz, Tacheng, and Yili is able to absorb carbon emissions and achieve carbon neutrality and still have more vegetation, which generates surplus value of USD 111.06 × 108, 90.62 × 108, 32.54 × 108, 7.81 × 108, 39.51 × 108, 98.13 × 108, and 89.35 × 108, respectively. In the same period, the carbon emissions of the seven regions of Aksu, Changji, Kumul, Hotan, Karamay, Turpan, and Urumqi were greater than the amount of carbon sequestered by vegetation, so these regions could not achieve carbon neutrality, and in order to rely on vegetation to achieve carbon neutrality, it is necessary to invest the following amounts in vegetation in these seven regions: USD 17.34 × 108, 173.65 × 108, 46.91 × 108, 2.85 × 108, 178.91 × 108, 44.54 × 108, and 111.59 × 108, respectively. From the sum of vegetation gains and losses of the fourteen cities in Xinjiang, we can obtain a total investment of 106.77 × 108 dollars in Xinjiang as a whole, and the areas of new cultivated land, forest land, and grassland added by the investment are 8029, 1710, and 35,016 km2, respectively.

Figure 5.

Average profit and loss from investment in vegetation to achieve carbon neutrality in Xinjiang as a whole and in each city from 2000 to 2020 (Total > 0 indicates that vegetation in the region is able to absorb carbon emissions and generate profit, while Total < 0 indicates that vegetation in the region is not enough to absorb carbon emissions and requires an investment budget).

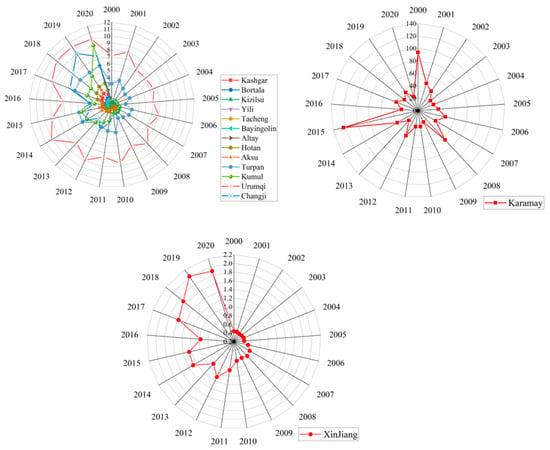

3.4. Change in Carbon Footprint Pressure Index

Looking at changes in the carbon footprint pressure index in Xinjiang as a whole and in the various cities and municipalities from 2000 to 2020 (Figure 6), Karamay has the highest carbon footprint pressure index, with an average multi-year carbon footprint pressure index of 40.77, and indices for the rest of the cities are, in descending order, Urumqi (7.91), Turpan (3.73), Changji (2.87), Kumul (2.46), Aksu (1.13), Hotan (1.02), Kashgar (0.94), Bayingolin (0.44), Tacheng (0.37), Bortala (0.36), Yili (0.34), Kizilsu Kirghiz (0.23), and Altay (0.06). It can be found that 8 of the 14 cities in Xinjiang were close to or exceeded the maximum carbon carrying capacity of vegetation ecosystems during the study period, of which the vegetation in the three cities of Kelamayi, Urumqi, and Turpan were in an overloaded state, and the Carbon Footprint Pressure Index in Xinjiang as a whole increased from 0.44 in 2000 to 1.89 in 2020, especially after 2012, when Xinjiang’s Carbon footprint pressure index was perennially greater than 1. These indicate that the carbon emissions in Xinjiang in the late stage have exceeded the maximum carbon carrying capacity of the vegetation, and the carbon emissions are far higher than the vegetation NEP; in addition, the vegetation in Xinjiang is in a perennial state of overload, and the excessive carbon emissions have led to the vegetation ecosystems not being able to absorb all of them efficiently, which in turn affects the operation efficiency of the carbon cycle of the ecosystems in Xinjiang.

Figure 6.

Changes in Xinjiang’s Carbon Footprint Pressure Index from 2000 to 2020.

3.5. Carbon Footprint Drivers

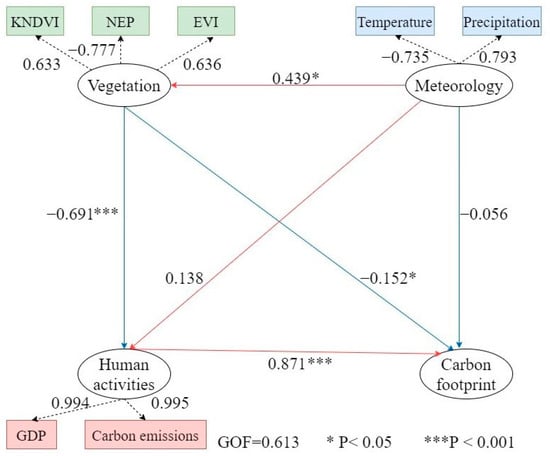

Structural equation modeling was used to investigate the direct and indirect effects of vegetation factors (KNDVI, NEP, EVI), meteorological factors (temperature, precipitation), and anthropogenic factors (GDP, carbon emissions) on the carbon footprint changes in Xinjiang (Table 2 and Figure 7). The goodness-of-fit (GOF) parameter of the structural equation model was 0.613, indicating a good model fit.

Table 2.

The impact of various factors on the variation in carbon footprint.

Figure 7.

Impact analysis of carbon footprint changes in Xinjiang from 2000 to 2020.(Dashed line indicates the factor loading relationship between observed variables and latent variables; red solid line indicates a positive effect, while blue solid line indicates a negative effect).

In terms of direct influence, human activities have the most significant influence on the carbon footprint in Xinjiang, with a direct influence coefficient as high as 0.871 (p < 0.001), indicating that human activities are the main factor driving changes in the carbon footprint in Xinjiang. The direct influence coefficient of the vegetation factor on the carbon footprint is −0.152 (p < 0.05), indicating that a change in vegetation cover has a certain negative influence on carbon footprint. The direct effect of the climate factor on the carbon footprint is relatively small, with a coefficient of −0.056, but still statistically significant. In terms of indirect influence, the vegetation factor has a strong indirect influence on the carbon footprint in Xinjiang by influencing human activities, with an indirect influence coefficient of −0.602. This indicates that a change in vegetation cover not only directly affects the carbon footprint, but also indirectly reduces the increase of carbon footprint by influencing human activities. The climate factor, on the other hand, has a strong indirect impact on the carbon footprint by influencing the vegetation factor, with an indirect impact coefficient of −0.212. Considering the direct and indirect impacts together, the total impact coefficient of the vegetation factor on the carbon footprint of Xinjiang is −0.754, which is largest negative impact among the three factors. The total impact coefficient of the climate factor is −0.268, which also shows a strong negative impact. The total impact coefficient of the human activity factor is 0.871, and all of the impacts are direct impacts, indicating that human activities play a decisive role in the change in the carbon footprint.

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of the Causes of Carbon Footprint Changes

From 2000 to 2020, Xinjiang’s carbon footprint experienced a considerable rise, characterized by two distinct stages: a slow increase from 2000 to 2011, followed by a significant acceleration from 2012 to 2020. The total vegetation carbon footprint area expanded from 30.41 × 104 km2 in 2000 and 46.42 × 104 km2 in 2011 to 104.48 × 104 km2 in 2020, marking a 3.44-fold increase over the two decades. This surge is attributable to several interconnected factors. Economically, Xinjiang’s industrial structure is dominated by heavy industries like energy, chemicals, and metallurgy, which are highly energy-intensive and carbon-emissive. Demographically, rapid urbanization and population growth have fueled higher energy demand, a trend exemplified by the surge in car ownership and associated transportation emissions. Societally, rising living standards and evolving consumption patterns have further contributed to the carbon footprint.

Concurrently, the region’s natural carbon sinks are weakening. This study observed a slow decline in the Net Ecosystem Productivity of Xinjiang’s forests, potentially due to forest aging. Research indicates that by 2020, the average age of natural coniferous forests in the Altay and Tianshan Mountains had reached 74 years, trending towards an old-growth stage [36]. This maturation reduces their carbon sequestration capacity, thereby diminishing their carbon sink function [37,38]. Furthermore, ecological pressures from overcultivation and overgrazing in some areas have degraded vegetation quality and weakened carbon absorption. The slow pace of energy structure transformation, with a low proportion of clean energy replacing fossil fuels, has exacerbated the issue. To address these challenges, future strategies must focus on upgrading industrial technology and improving energy efficiency. In the agricultural sector, the adoption of green, low-carbon agrochemicals and energy-efficient tillage and irrigation techniques will be essential to effectively reduce the overall carbon footprint.

4.2. Accelerating the Construction of the Carbon Trading Market in Xinjiang

This study identified major carbon source and sink areas in Xinjiang and quantified the vegetation investment required for carbon neutrality at both the regional and prefectural levels. These findings can directly inform a carbon trading market, facilitating transactions between source and sink areas to promote sustainable economic and environmental development. The carbon trading market, a mechanism for achieving emission reductions through the buying and selling of carbon credits, incentivizes enterprises to lower emissions, thereby fostering green, low-carbon growth. The 2024 implementation of the Interim Regulations on Carbon Emission Trading Administration has provided a crucial national legal framework for Xinjiang, clarifying core rules on quota allocation, data verification, and market supervision. As a major energy province, Xinjiang has made phased progress in establishing its carbon market, driven by the “dual-carbon” goals.

Pioneering local projects offer valuable models. Altay initiated Xinjiang’s first grassland carbon sink trading under an international voluntary standard, using proceeds from restored grasslands to fund further ecological restoration. This demonstrates a viable pathway for transforming ecological value in arid regions and exploring a “grassland carbon sink + eco-tourism” model. Similarly, Yili was selected as a national forestry carbon sink pilot, achieving a win–win for ecology and the economy through a “systematic management + land greening + carbon trading” approach. In Kashgar, corporate investment in forest carbon sink data mapping is unlocking development potential suitable for southern Xinjiang’s climate.

Despite this progress, Xinjiang lacks a regional carbon trading market. This results in limited financing channels, high transaction costs, low market liquidity and awareness, and an over-reliance on the national market, leading to insufficient market connectivity. Looking ahead, a synergistic policy and market effort is needed to build a robust regional carbon trading platform. Enhancing liquidity and participation is paramount. By leveraging Xinjiang’s unique ecology, a “carbon sink+” integrated development model—combining carbon trading with eco-tourism and green agriculture—must be realized. This will transform carbon trading into a new engine for green growth, reducing Xinjiang’s carbon footprint and steering the region toward sustainable, high-quality development and the ultimate goal of a carbon-neutral Xinjiang.

4.3. Recommendations for Promoting Carbon Neutrality in Xinjiang

From 2000 to 2020, most cities in Xinjiang exhibited trend of declining carbon neutrality, with several key areas like Aksu, Hami, Hotan, and Kashgar transitioning from carbon sinks to sources post-2012. Major cities such as Urumqi and Kelamayi remained persistent carbon sources throughout this period. This alarming trend, highlighting severe challenges to Xinjiang’s dual-carbon goals [39], is primarily driven by an energy-intensive industrial structure dominated by heavy industry and a fossil fuel-dependent energy mix. Rapid urbanization and the proliferation of automobiles have further exacerbated emissions. To reverse this, future strategies must focus on sustainable land use and enhancing the region’s vast carbon sink potential. Although predominantly desert, Xinjiang’s unutilized land holds significant sequestration capacity [40]. Therefore, optimizing territorial spatial planning and fully leveraging the immense carbon sink of its deserts are critical measures for decoupling economic growth from emissions and achieving a green, low-carbon transition.

Achieving sustainable development in Xinjiang requires strategic land-use reconfiguration, prioritizing the conversion of underutilized land into grasslands under strict water-use constraints to boost ecosystem carbon sequestration. This ecological restoration must prioritize native, drought-resistant species adapted to local conditions. The region’s flora includes desert xerophytes like Haloxylon and Tamarix, grassland species such as Stipa, and forests featuring Picea, Larix, and Populus euphratica. These species are ideal due to their extensive root systems and water-conserving traits. Successful implementation of ecological restoration also depends on upholding key national policies. Xinjiang must continue to enforce regulations protecting arable land and advancing major ecological projects, including the Three-North Protective Forest and the Degraded Grassland Rehabilitation initiatives. By integrating scientific, site-specific planting with these robust policy frameworks, Xinjiang can effectively expand its carbon sinks and ensure the stability of its arable land, forest, and grassland areas, paving the way for its carbon neutrality goals.

To achieve its carbon neutrality goals, Xinjiang must adopt a differentiated, region-specific strategy. For the six major carbon sinks—Altay, Bortala, Bayingolin, Kizilsu Kirgiz, Tacheng, and Yili—the focus should be on strengthening ecological protection and leveraging their favorable environments to develop eco-tourism. Concurrently, the four major carbon source areas—Changji, Karamay, Turpan, and Urumqi—must accelerate industrial upgrading, enhance energy efficiency, and transition towards clean energy sources. Beyond these industrial and ecological measures, fostering broad societal participation in carbon neutrality initiatives is crucial. The integrated implementation of these strategies is fundamental to steering Xinjiang towards a sustainable future, ensuring the realization of its carbon neutrality objectives and the vision of a beautiful Xinjiang.

5. Conclusions

This study explored the carbon footprint of Xinjiang and its influencing factors to provide data support for the vegetation area and investment needed to achieve carbon neutrality. The results show that from 2000 to 2020, while the total annual Net Ecosystem Productivity of vegetation slowly increased from 6434.45 × 104 t to 8149.66 × 104 t, carbon emissions surged dramatically from 2836.08 × 104 t to 15457.91 × 104 t. A factor analysis revealed that human activities were the primary positive driver of this growing carbon footprint, whereas the vegetation factor acted as the main negative inhibitor. This dynamic imbalance is evident in the geography: six regions (Altay, Bortala, Bayingolin, Kizilsu Kirgiz, Tacheng, and Yili) formed the major carbon sinks (66.95% of total Net Ecosystem Productivity), while four regions (Urumqi, Changji, Kumul, and Karamay) were the dominant carbon sources (61.31% of total emissions). Consequently, Xinjiang’s carbon footprint expanded significantly, with its total area increasing from 30.41 × 104 km2 in 2000 to 104.49 × 104 km2 in 2020, an increase of about 3.44 times. The vegetation’s capacity to offset emissions was exceeded after 2011. To reverse this trend, an investment of USD 106.77 × 108 is required to convert 8029 km2 of cropland, 1710 km2 of woodland, and 35,016 km2 of grassland. Achieving this demands a multi-pronged strategy: accelerating the establishment of a regional carbon trading market, enforcing sustainable spatial planning, and implementing strict ecological protection. This includes targeted afforestation, optimizing crop types, and, crucially, strengthening carbon sinks in areas like Altay and Yili through eco-tourism, while accelerating low-carbon economic transformation in source areas like Urumqi and Karamay. Promoting a low-carbon lifestyle and broad societal participation are also essential for Xinjiang to meet its dual-carbon and sustainable development goals.

Author Contributions

S.Y.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Review and Editing, Writing—Original Draft; M.Z.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Review and Editing; S.Y., C.X., J.Z., L.Z., Z.Z., J.K. and M.Z.: Data Collection, Figure Design, Formal Analysis, Visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (42261013, Mei Zan) and the Key Project of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Natural Science Fund (2023D01A49, Mei Zan).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- IPCC. Global Warming of 1.5 °C; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Hu, S.; Tong, H. Carbon footprint of household meat consumption in China: A life-eyele-based perspeclive. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 169, 103325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouladvand, J.; Oudendijk, R.; Hooimeijer, M.; Derks, R.; Berndsen, S. Carbon footprint of a news broadcasting organisation. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 39, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Zhou, J.; Xu, X.; Luo, H.; Zhao, J.; Yang, C. Effect of land use changes on the temporal and spatial patterns of carbon emissions and carbon footprints in the Sichuan Province of Western China, from 1990 to 2010. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2016, 36, 7244–7259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L. Spatial and Temporal Evolution of Crop Cultivation Carbon Footprint in the Loess Plateau: Driving Force and Trend Prediction. Environ. Sci. 2025, 46, 3148–3160. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Huang, X.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, X. Spatiotemporal changes of carbon footprint based on energy consumption in China. Geogr. Res. 2013, 32, 326–336. [Google Scholar]

- Ti, J.; Zheng, Y.; Duan, W.; Zhao, H.; Qin, Y.; Yin, G.; Xie, L.; Dong, W.; Lu, X.; Song, Z. Carbon footprint of tobacco production in China through Life-cycle-assessment: Regional compositions, spatiotemporal changes and driving factors. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 165, 112216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Zhang, Y. Spatiotemporal patterns of energy carbon footprint and decoupling effect in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2021, 76, 206–222. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Sun, S.; Yin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Tang, Y.; Wu, P. Decoupling trend and drivers between grain water-carbon footprint and economy-ecology development in China. Agric. Syst. 2024, 217, 103904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zheng, D.; Xu, X. Factor decomposition analysis on the energy carbon footprint ecological pressure change in China. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2015, 29, 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Ma, R. Clean energy synergy with electric vehicles: Insights into carbon footprint. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 53, 101394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Murhed, M.; Alam, M.; Ghanallou, W.; Balsalobre-lorente, D.; Khudovkulov, K. Can minimizing risk exposures help in inhibiting carbon footprints? The environmental repercussions of international trade and clean energy. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 347, 119195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Lu, L. Assessment of carbon footprint size, depth and its spatial-temporal pattern at the provincial level in China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2020, 40, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Tam, Y.; Lai, X.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, S. Carbon footprint accouning of prefabneated buildings: A circular economy perspective. Build. Environ. 2024, 258, 111602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B. Transition of the food consumption carbon footprint of China’s urban and rural residents. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2023, 33, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Chen, W. Research on the correlation network of carbon emissions and economic between Chinese urban agglomerations. Urban Clim. 2024, 57, 102118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Yang, B. Research on the Dynamic Impact Effects of Regional Agricultural Carbon Footprint: A Case Study of Planting Industries in Weifang City. Rural. Econ. 2020, 37, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Han, R.; Li, X. Spatial-temporal dynamics of carbon budgets and carbon balance zoning: A case study of the middle reaches of the Yangtze River Urban Agglomerations, China. Land 2024, 13, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruhn, S.; Gislason, S.; Rogild, T.; Andreasen, M.; Ditlevsen, F.; Larsen, J.; Sønderholm, N.; Fossat, S.; Birkved, M. Pioneering historical LCA-A perspective on the development of personal carbon footprint 1860–2020 in Denmark. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 46, 582–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Study on the spatial decomposition of carbon footprint and the embodied carbon emission transfer of the e-commerce express box. Geogr. Res. 2022, 41, 92–110. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Fan, L. Tracing and Decomposing Carbon Footprint of FDI in Shanghai along National Value Chains: A Study Based on China’s Inter provincial Input output Database Distinguishing Firm Heterogeneity. Shanghai J. Econ. 2024, 45, 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Giusti, G.; Galo, N.; Pereire, R.; Silva, D.; Filimonau, V. Assessing the impact of drought on carbon footprint of soybean production from the life cycle perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 425, 138843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, L.; Ramaswami, A.; Chen, W.; Tong, K. Tracking a Chinese megacity’s community-wide carbon footprint and driving forces from a multi-infrastructure perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 460, 142420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, M.; Kratena, K. The carbon footprint of European households and income distribution. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 136, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Han, X.; Li, T.; Li, Y.; Li, K. Study on carbon footprint accounting by provinces and emission reduction strategy of potato in China—Based on life cycle assessment. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2024, 45, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H.; Zhu, Q. Accounting carbon footprint of rice in China based on life cycle evaluation. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2023, 37, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Zan, M.; Zhou, J.; Zhai, L.; Xue, C.; Ke, J.; Zhao, Z.; Li, R.; Liu, Y. Study on the carbon emission offset effect of vegetation in typical arid areas of Xinjiang, China. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 178, 114125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Ke, J.; Tang, Z.; Chen, A. Productivity parameters implications and estimations of four terrestrial. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2001, 25, 414–419. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, Z.; Zhou, C.; Ou, Y.; Yang, W. A carbon budget of alpine steppe area in the Tibetan Plateau. Geogr. Res. 2010, 29, 102–110. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, S.; He, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Y.; Xin, Y.; Mo, Y. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Vegetation Net Ecosystem Productivity and Its Response to Drought in Northwest China. GIScience Remote Sens. 2023, 60, 2194597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Pan, J. Spatio-temporal simulation and differentiation pattern of carbon emissions in China based on DMSP/OLS nighttime light data. China Environ. Sci. 2019, 39, 1436–1446. [Google Scholar]

- Zhe, S.; Xiao, L.; Jiang, C.; Yi, G.; Xuan, Z.; Ke, Z.; Jie, Z. Spatiotemporal Evolution and Influencing Factors of Carbon Footprint in Yangtze River Economic Belt. Land 2025, 14, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Fan, W.; Li, D.; Liu, X.; Song, M. Driving Factors of Global Carbon Footprint Pressure: Based on Vegetation Carbon Sequestration. Appl. Energy 2020, 267, 114914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urumqi, Department of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. Department of Agriculture and Rural Affairs Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region 2025 Department Budget Disclosure Report. 2025. Available online: https://nynct.xinjiang.gov.cn/xjnynct/ (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Spitale, D.; Pelraglia, A.; Tomaseli, M. Structural equation modelling detects unexpected differences between bryophyte and vascular plant richness along multiple environmental gradients. J. Biogeogr. 2009, 36, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zan, M.; Yang, X.; Dong, Y. Prediction of Forest Vegetation Carbon Storage in Xinjiang. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2023, 32, 226–234. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, Y.; Li, W.; Ciais, P.; Sun, M.; Zhu, L.; Yue, C.; Chang, J.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J.; et al. Forest Aging Limits Future Carbon Sink in China. One Earth 2024, 7, 822–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, R.; Chen, J.M.; Xu, M.; Lin, X.; Li, P.; Yu, G.; He, N.; Xu, L.; Gong, P.; Liu, L.; et al. China’s current forest age structure will lead to weakened carbon sinks in the near future. Innov. 2023, 4, 100515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Zan, M.; Yuan, R.; Chen, Z.; Kong, J.; Xue, C.; Zhou, J.; Zhai, L. Carbon Stock Changes and Forecasting in Xinjiang Based on PLUS and InVEST Model Approach. Environ. Sci. 2025, 46, 378–387. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Houghton, R.; Tang, L. Hidden carbon sink beneath desert. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 5880–5887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.