Abstract

To address the misalignment between conservation–development policies and villagers’ needs in traditional villages, this study identifies core demands through a questionnaire survey in 112 villages across three counties in Hubei Province, China. An evaluation system encompassing public facilities, infrastructure, exterior environment, interior environment, and village culture (23 indicators) was analyzed using the Kano model and Better–Worse coefficients (211 valid questionnaires). Results reveal the primary needs ranking: village culture > exterior environment > interior environment > infrastructure > public services. Key findings show villagers prioritize traditional building conservation, cultural identity, and roof improvement, while certain public service investments (e.g., water supply, signage, education) yield lower satisfaction. Notably, villagers are indifferent to lighting improvements. This indicates a deviation from past government priorities and underscores the necessity of integrating villager perspectives into “top-down” decision-making for sustainable village development. The findings provide practical guidance for habitat improvement and precise policy formulation in Northeastern Hubei.

1. Introduction

The United Nations Human Settlements Programme emphasizes the sustainable development of human settlements at different levels, including cities, towns, and villages [1]. Sustainable village development is essential to conserve and improve resources [2]. The conservation and development of villages worldwide vary from country to country and region to region, and in general, there are common challenges and urbanization problems faced by governments in the process of village building and development [3,4,5,6].

Some traditional villages in Japan, such as those in Tamakasa City, are facing abandonment and disrepair due to tourism development and urbanization [7]. In order to protect these traditional villages, the government and social groups have intensified their efforts to promote and protect them, encourage cultural heritage conservation, restoration, and development of traditional villages, and raise public awareness and preservation of traditional villages [8]. Most of the traditional villages in Korea are located in Gyeongsangbuk-do. The state of preservation of traditional villages varies from village to village, and in some cases, the prototypes have been destroyed, making it difficult to find traces of traditional villages. Its government systematically surveys traditional villages at the national level and develops management plans [9]. Some of Italy’s traditional villages, such as Tuscany and Umbria, attract many tourists because of their long history and cultural value. To ensure the sustainable development of these traditional villages, the government and social groups have taken measures such as restricting tourist development and vehicle traffic and encouraging the conservation and restoration of cultural heritage [10].

As a result of rapid urbanization and population loss, many traditional villages in China have become “hollowed out” and damaged [11,12]. In response to such challenges, the Chinese government has adopted a series of policies to enhance the protection and development of traditional villages. Since 2012, China has established a system for protecting traditional villages in China, organizing six national surveys and listing 8155 traditional villages on the national protection list by 2023, and forming a four-tier protection system from national to provincial, municipal, and county levels. It also includes establishing special funds, implementing traditional village protection signs for listing and protection, and formulating demonstration plans for conserving and using traditional villages in a concentrated and contiguous manner [13]. Overall, the conservation and development of traditional villages in China have experienced a shift from the protection of ancient buildings and the spatial pattern of the entire village to the importance and protection of the intangible cultural heritage of traditional villages; from the mere protection of ancient buildings and physical spatial production to spatial production with social significance, which includes the spatial form and planning of traditional villages, village culture, a social interaction system, and the regional characteristics formed on this basis [14]. The above measures are undeniable. Undeniably, the above actions have contributed to the conservation and development of traditional villages to a certain extent. Still, the key to the sustainable development of traditional villages lies in whether villagers are willing to live there for a long time, which is the basis for the sustainable development of living villages. At present, a large number of traditional villages are in a state of inactivity due to poor living conditions and inadequate supporting facilities; in addition, a large amount of capital investment is required in the process of renovation, development, and governance, and the role of financial assistance from the government alone is still limited.

Recent research on village habitat in China has been conducted mainly from the perspectives of improvement, design, and assessment methods [15]. Some studies have concluded that the quality of life of rural residents can be effectively improved by improving rural infrastructure, environmental sanitation, and public services [16]; some studies have mentioned indicators of the social dimension of sustainable village development [17] and constructed a system of indicators of rural environmental suitability in terms of plant landscape, activity space, and humanistic care [18]. In addition, promoting the improvement of village habitat depends not only on the physical characteristics of the living environment but also on the environmental and psychological variables of villagers [19]. Villager satisfaction has been considered one of the most influential factors in achieving quality of life [20]. Therefore, village improvement should combine ‘top-down’ and ‘bottom-up’ approaches, and all villagers should be encouraged to participate. In recent years, although China has been continuously improving its village environment under the rural revitalization strategy, village improvement is mainly a top-down decision by the government, which does not fully understand the real needs of villagers and makes it difficult to stimulate their initiative and enthusiasm to participate in the conservation and use of villages.

Today, the Kano model is widely used in customer satisfaction analysis, outlining functional customer satisfaction indicators, wants, needs, or indifference. The Kano approach attempts to understand the emotional impact of different features on customers based on particular questionnaires and Kano assessment forms [21]. Although this approach has been applied to many fields such as computer science [22,23], medicine [24,25], services [26,27,28,29,30,31], education [32,33,34], and product design [35], and has been extensively researched by scholars in recent years. However, this approach has been less studied regarding village habitat improvement needs. The Kano model has been used in various fields and may be further applied across borders, for example, in urban planning, environmental protection, and public services [36,37]. Each feature or function in the Kano model has a specific category, so it can help decision-makers prioritize improvements and has some implementation ability in prioritizing village habitat improvement needs [38]. In summary, the Kano model can assist in exploring villagers’ needs and expectations and formulating appropriate policies to improve the quality of traditional village habitat and villagers’ satisfaction.

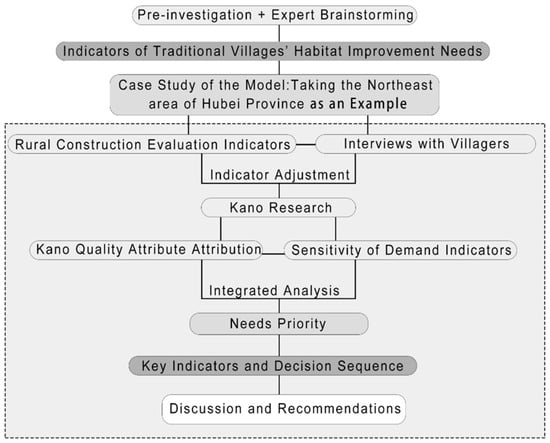

To systematically address these gaps, this study proposes a mixed-methods framework (Figure 1) integrating both expert knowledge and villager perspectives. The framework comprises four key phases: Indicator Identification: Initial indicators of habitat improvement needs are established through literature review, pre-investigation, and expert brainstorming; Field Validation & Refinement: Indicators are tested and adjusted via case studies (Northeast Hubei) and structured interviews with villagers; Demand Prioritization: The Kano model attributes quality characteristics to each indicator and quantifies demand sensitivity using the Better–Worse coefficient, enabling prioritization based on impact on villager satisfaction; Decision Support: An integrated analysis synthesizes findings to identify key improvement priorities and sequences for actionable recommendations. In summary, the Kano model can assist in exploring villagers’ needs and expectations and formulating appropriate policies to improve the quality of traditional village habitat and villagers’ satisfaction. The proposed framework (Figure 1) operationalizes this by translating localized needs into a hierarchical decision sequence.

Figure 1.

The method framework.

The study focuses on improving village habitat and explores the sustainable development of traditional villages in China from the perspective of villagers’ needs for habitat improvement. The study selects 112 villages with historical and cultural elements in the Northeastern Hubei Province region for investigation and research, conducts questionnaire and interview surveys to obtain data on villagers’ needs, and combines the Kano model and Better–Worse coefficient analysis to quantitatively analyze the priority of traditional village habitat improvement needs, intending to provide a basis for precise policy support for traditional village habitat improvement.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Scope of the Study and Data Sources

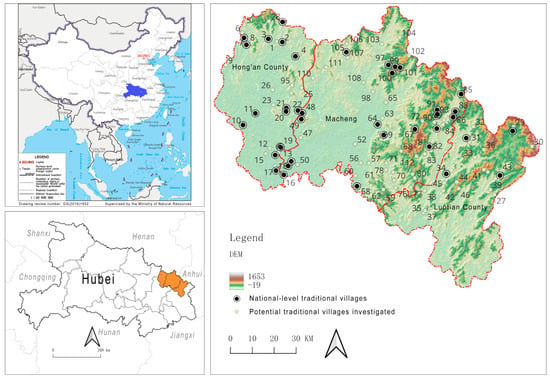

The study area is the three counties of the central part of China, which is located at the junction of the three provinces of Hubei, Anhui, and Henan, backed by the Dabie Mountain range, and contains Hong’an, Macheng, and Luotian counties. The area is historically famous as a revolutionary base, with many traditional historical buildings, traditional villages, revolutionary heritage, relics, and so on, which contain great cultural value and are worthy of preservation and development in patches [39]. The object of this study explicitly contains 112 villages (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Geographical location of the study area.

According to the ancient book Guangxu Guang’an Fu Xinzhi, immigrants from Macheng County played an important role in the migration of people from Hu-Guang to Sichuan. This migration promoted cultural exchange and dissemination. In addition, as one of the important bases of the Chinese revolution, Hong’an, Macheng, and Luotian Counties played an extremely important role in modern Chinese history. Hong’an County, renowned as China’s “First General County,” still preserves a wealth of historical sites and memories [40]. These traditional villages and historical memories serve as important historical carriers for the protection and transmission of China’s traditional and historical cultures. This study, taking resident satisfaction as its starting point, provides references and basis for improving the living environment in regions dedicated to the protection and transmission of historical and cultural heritage, thereby making significant contributions and holding important significance.

The data for this study comes from two sources. The first source is data on the current state of the living environment in 112 villages, which was collected on site using drones and other equipment. The data includes the status of public service facilities, the interior environment of traditional buildings, and the preservation of village culture. This data was mainly used to assess the local living environment. The second source is data on the needs of villagers, which was obtained through a Kano questionnaire survey.

2.2. Research Methods

2.2.1. The Kano Model

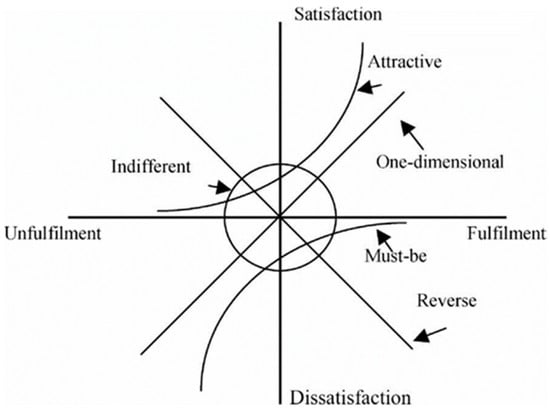

The Kano model is a two-dimensional cognitive model proposed by Noriaki Kano (Figure 3), which is an analytical model of charm quality theory in the field of business management and is used to distinguish the relationship between the “provision” of different needs and “satisfaction” [3,4]. Kano’s model differs from asking respondents directly about their needs and instead breaks away from the traditional questionnaire approach by setting both positive and negative questions to assess respondents’ satisfaction, classifying them into five categories of needs (Table 1): essential needs (M), desired needs (O), charismatic needs (A), Indifferent needs (I) and reverse demand (R). In this study of the demand for habitat improvement in traditional villages, the Kano demand categories can be expressed as follows: (1) Essential demands: These are the types of improvements that villagers believe must be provided. These improvements may not increase the villagers’ satisfaction with their lives, but their absence would be inconvenient or unbearable. (2) Desired needs: These are the types of improvements that the villagers expect to have, and their improvement would make them feel satisfied, while their absence would make them feel dissatisfied but not unbearable. (3) Attractive needs: These are the improvements that the villagers would not expect or be surprised by. These improvements are beyond their expectations and would not affect their everyday lives if they were not provided. Still, if provided, they would significantly improve villagers’ satisfaction and quality of life. (4) Non-differentiated needs: are the types of improvements that villagers do not care about and whose improvement or non-improvement would have little impact on their lives. (5) Reverse needs: are the types of improvements villagers do not want to make.

Figure 3.

Kano model of quality attributes.

Table 1.

Kano quality-type evaluation table.

Formulas for calculating the positive and negative questions in the KANO model questionnaire:

where A represents the frequency of the charm quality element, M represents the frequency of the essential quality element; and O represents the frequency of the expected type demand. The KA, KM, and KO results are combined for size comparison. If this evaluation quality factor KM is the largest, the evaluation quality factor is essential quality; if KO is the largest, the evaluation quality factor is desired quality; if KA is the largest, the evaluation quality factor is charismatic quality.

2.2.2. Better–Worse Coefficient Analysis

By processing the questionnaire data and using the scores of each indicator as the base data, the Better–Worse coefficient analysis was used to calculate the satisfaction influence and dissatisfaction influence of each demand indicator to quantify the satisfaction level of the demand indicator, where

This indicator is between 0 and 1, the higher the value, the higher the sensitivity and the higher the priority. The higher the value, the greater the sensitivity and the higher the priority;

Which ranges from −1 to 0. The smaller the value, the greater the sensitivity and the higher the priority.

3. Kano Questionnaire and Statistical Analysis

3.1. Indicator System Establishment

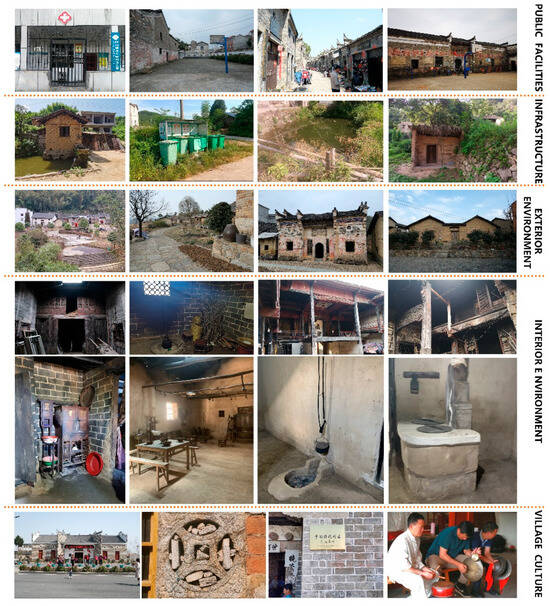

Based on literature search, site regional characteristics, evaluation indicators of rural construction in Hubei Province in 2022, and expert suggestions, this study proposes a traditional village living environment improvement demand index system, uses the Kano model for questionnaire design, and constructs a demand priority evaluation model. Then the Better–Worse coefficient analysis method is used to build a satisfaction index matrix, classify the intensity of traditional village habitat improvement demand indicators, prioritize the indicators in the same kind of demand intensity, and finally put forward further suggestions for improving the village habitat environment by combining the 2022 Hubei rural construction evaluation data (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Photos of the evaluation system (taken by the authors).

In order to build a comprehensive indicator system and to ensure that the types of demand are holistic and different, the primary indicators are constructed from five dimensions: public facilities, infrastructure, exterior environment, interior environment, and village culture, by combining research, villagers’ interviews, literature review, and experts’ suggestions. The first-level indicators were then selected to represent the meaning of the first-level indicators. Five primary and Twenty-Three secondary demand indicators were established (Table 2).

Table 2.

Traditional habitat improvement needs indicator framework.

3.2. Kano Questionnaire Design

The design of this Kano questionnaire was divided into two main parts: firstly, the basic information of the interviewees, and secondly, the Kano questionnaire question set. Each question was set as positive and negative (Table 3. The 23 secondary needs corresponded to 46 positive and negative item questions.

Table 3.

Kano model questionnaire form.

3.2.1. Questionnaire Data Reasonableness Test

In this study, on-site research and questionnaire collection was carried out in 112 villages. Considering the villagers’ reading habits and literacy levels, the questionnaire data were collected online and offline. A total of 352 questionnaires were collected, and 141 invalid questionnaires were excluded, making 211 accurate and valid questionnaires available for subsequent data analysis, with a valid return rate of 59.9%.

The Kano questionnaire was analyzed for reliability and validity through SPSS25.0. The results are as follows (Table 4). The overall Cronbach’s alpha value of the questionnaire was 0.929, including 0.918 for the positive questions and 0.975 for the negative questions, with values greater than 0.9. The KMO measure was 0.928, and Bartlett’s sphere test statistic had a significant probability of 0.000, which was less than 0.01 and was relevant, indicating that the questionnaire had good validity.

Table 4.

Kano questionnaire reliability analysis.

3.2.2. Characteristics of the Kano Respondents

The basic information of Kano respondents is shown below (Table 5), covering gender, age, education level, and occupation. The statistical analysis of the questionnaire shows that 64.93% of the respondents were male and 35.07% were female; their ages were mainly in the 19–45 and 45–60 age groups; their education levels were primarily high school or secondary school, accounting for 40.28%; and their occupations were primarily farmers, accounting for 20.85%. The interviews with local villagers show that the population of the traditional villages in the area is old, with most young people working outside and children staying in interiors during holidays, with few exterior activities. The hollowing out of the village “people—residence—production” is obvious.

Table 5.

Kano questionnaire—respondents’ basic information.

4. Results

4.1. Presentation of Kano Model Results

Based on the Better–Worse coefficient analysis, the initial priority ranking of demand types in the results can be determined based on the importance determination of “M > O > A > I.” Still, since the demand of the same intensity type in the results cannot be determined by a single comparison of the Better and Worse values, it is necessary to introduce the sensitivity calculation to determine the degree of demand for each type of indicator. The final comparison of the magnitude of the values is used to determine the priority ranking of demand for the same intensity type. In this paper, the sensitivity of a demand indicator is expressed in terms of the R-value, and the results are calculated as follows (Table 6). The final demand type and priority ranking results are as follows (Table 7).

Table 6.

Sensitivity of demand indicators—R.

Table 7.

Prioritization of demand indicators.

From the comprehensive analysis of the data, it can be seen that the five primary needs are ranked as E (village culture) > C (exterior environment) > D (interior environment) > B (infrastructure) > A (public services). Among the desired attributes, the ranking is E2 (traditional building conservation), E3 (cultural identity), D1 (roof improvement), D3 (toilet improvement), A4 (commercial facilities), and B5 (waste disposal system); there are more indicators of charm attributes, the first three are E1 (regional cultural identity), E5 (artisan spirit) and E4 (event organization). The latter is C3 (courtyard gardens), D2 (roof improvements), C2 (recreational plaza green areas), A3 (sanitary facilities), B1 (lighting systems), D4 (kitchen improvements), C1 (day care centers for the elderly) and C4 (public buildings) respectively. The last five are B3 (drainage improvement systems), A2 (recreational and sports facilities), B4 (tap water supply systems), B2 (signage and guidance systems), and A1 (educational facilities). Among the non-differentiated attributes, D5 (light demand) is an indicator that villagers do not care about.

4.2. Identification of Villagers’ Priorities for Habitat Improvement in Traditional Village Areas

Identification of Villagers’ Priorities for habitat improvement in traditional village areas. The results of the questionnaire show that villagers are more concerned about the following aspects of the habitat environment in traditional village areas: E2 (traditional building conservation), E3 (cultural identity), D1 (house roof improvement), D3 (house toilet improvement), A4 (village commercial facilities) and B5 (waste disposal system). The results are very useful in guiding the local government in the direction of later work and in formulating relevant decisions and measures.

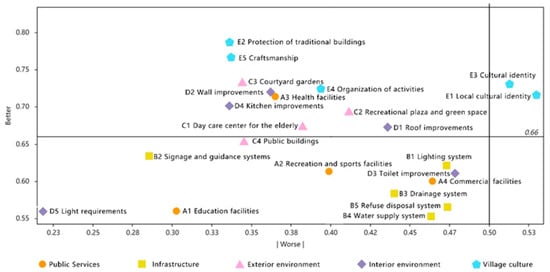

Higher cultural identity of Villagers in traditional village areas. According to the study’s results (Figure 5), the villagers’ need for the cultural identity of the village takes precedence over the need to improve village infrastructure. Among the desired attributes, the first two are E2 (traditional building conservation) and E3 (cultural identity), which take precedence over B5 (waste treatment system) in the infrastructure indicator; among the charm attribute indicators, the first three are E1 (regional cultural identity), E5 (artisan spirit) and E4 (event organization), all of which are related to the village culture indicator; At the same time, three of the last five are infrastructure indicators, namely B3 (drainage system), B4 (water supply system), and B2 (signage system).

Figure 5.

Four-quadrant diagram of demand quality.

Villagers’ demand for public services such as commercial facilities and lighting is high. According to the study’s results (Figure 5), extracting the mean values of each secondary demand indicator under the primary demand shows that villagers’ demand for infrastructure improvement has priority over the demand for public service improvement in the village. Among the desired attributes, A4 (commercial facilities) has a higher priority than B5 (waste disposal system). Among the attractive attributes, B1 (lighting system) and B3 (drainage improvement system) have a higher priority than A1 (educational facilities) and A2 (recreational and sports facilities).

Higher villagers’ demand for front-of-house vegetable garden planning and interior toilet and kitchen environment improvement. According to the results of the study (Figure 5), villagers have a higher priority for the need to improve the quality of the physical environment, both interiors and exteriors, especially for the planning of the vegetable garden in front of and behind the house and the improvement of the interior toilet and kitchen environment. At the exterior environment level, the demand indicators related to exterior environment improvement are all charismatic demands, with C3 (gardening) topping the list of villagers’ demands, followed by C2 (recreational plaza and green space), C1 (daycare Centre for the elderly) and C4 (public buildings); at the interior environment level, D1 (roof improvement) and D3 (toilet improvement) have the highest priority, followed by D2 (roof improvement), D4 (kitchen improvement) and D4 (kitchen improvement), D4 (kitchen improvements), and D5 (light needs) for translucent tiles has the lowest priority.

5. Discussion and Recommendations

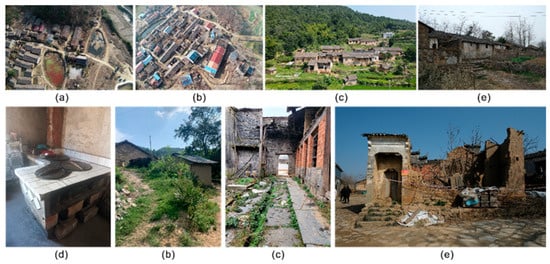

As the transmission of history and memory in rural revitalization, the core of the conservation and development of traditional villages needs to revolve around the villagers’ central consciousness rather than mere material space. Retaining memories requires integrating capital logic and cultural logic into the social life scenes of villages [14] and meeting villagers’ needs for a better living environment based on preserving the historical appearance. The research found that the following common problems exist in the study area (Figure 6): poor drainage and waste disposal infrastructure, poor quality of public space at village entrances and streets, some buildings in disrepair and need of repair, low level of interior modernization, and hollowing out of villages. Based on this, the following discussion is conducted to improve the quality of the habitat of traditional villages, increase villagers’ satisfaction and better promote the development and construction of villages.

Figure 6.

Photos of the village research site. (a) Poor drainage and waste disposal infrastructure; (b) poor quality of public space; (c) buildings in disrepair; (d) low level of interior modernization; (e) hollowing out of villages (taken by the authors).

5.1. The Government’s “Top-Down” Decision-Making Mechanism Tends to Ignore the Central Status of Villagers

Traditional villages are not cultural relics, and the previous top-down decision-making mechanism of the government tends to result in the over-protection of traditions, which prevents villagers from freely repairing their ancestral houses and highlights the conflict between people and land. The protection and use of traditional villages in China have always relied on the model of “government requests and planners’ technical proof.” Traditional villages are controlled in style, and traditional buildings are repaired according to “repairing the old as the old” and “restoring the original plateau to its original location.” This model has achieved outstanding results in conserving traditional villages, extensively restoring their historical appearance, and reshaping memories. Still, the focus of this model is on the control of the architectural style and the restoration of historical elements. There is a lack of consideration for optimizing the front of the house and the interior environment. Unlike in urban areas, villagers have a high degree of decision-making power over their living environment, and the planning of their home base and the layout and decoration of the interior of their houses all depend on their wishes. In traditional village areas, however, the ‘top-down’ model tends to ignore the villagers’ wishes and restrict their behavior, resulting in over-protection. According to the results of the questionnaire, villagers have the highest demand for C3 (vegetable garden) and C2 (green space in the recreation square) for the exterior environment and D3 (toilet improvement) and D4 (kitchen improvement) for the interior environment. The priority of the results also reflects the government’s lack of comprehensive understanding of villagers’ needs, no effective channels to communicate with villagers and understand their real needs, and neglect of the central position of villagers.

5.2. The Government’s Orientation Towards the Construction of the Habitat of Traditional Villages Conflicts with the Real Needs of Villagers

Over the years, the government has invested significant human and financial resources into the preservation of traditional villages. For example, efforts have been made to preserve the overall architectural style of village buildings and to construct roads within and around the villages. Significant achievements have been made in the comprehensive preservation of traditional villages. However, public facilities closely related to residents’ comfort, as well as improvements to indoor and outdoor environments, are often overlooked. For example, recreational squares, green spaces, rooftops, restrooms, and commercial facilities. The study found that the population of villages continues to decline, and with the accelerated urbanization process, the population of villages is moving to towns and central cities. At the same time, due to the unique nature of traditional preservation, there are many restrictions on the renovation of the indoor and outdoor environments of traditional buildings. These restrictions are crucial for the protection of traditional culture. However, how to meet the contemporary villagers’ needs for the layout of their living spaces and facilities is equally worthy of the government’s and society’s attention. The results show that increasing the number of daily grocery stores and parcel delivery points can enhance villagers’ satisfaction. The rational development of rural convenience facilities is the foundation of rural revitalization and one of the effective measures to improve villagers’ satisfaction [41,42]. The Kano model, based on villagers’ genuine needs, statistically identifies the key areas of rural development that influence villagers’ satisfaction, providing important references for the future protection and development of traditional villages.

5.3. Government Guidance to Stimulate Villagers’ Initiative and Motivation and to Keep People in the Village Is the Core of Sustainable Development

Village development cannot be achieved without the guidance and support of the government. A single “bottom-up” model tends to weaken the central role of villagers. The basic logic of villagers’ initiative is “interest-related, simple and practical.” As a decision-making body, the government plays a role in making decisions and guiding the direction of traditional village cultural heritage conservation. It should recognize the central role of villagers, stimulate their sense of belonging and enthusiasm, meet their needs for modernizing their living environment and improving their livability, and leave people behind as the key to sustainable village development.

In improving the habitat, the “top-down” concept emphasizes the leading role of government departments. The government can guide and promote habitat improvement by formulating policies, providing financial support, and coordinating resources. This approach can unify the direction and objectives of improvement and ensure the coordination and consistency of improvement measures. The ‘bottom-up’ approach focuses on the participation and autonomy of villagers. As a group living directly in the village, villagers should actively participate in environmental improvement. They can make suggestions and recommendations, participate in planning and decision-making, and organize themselves to improve and maintain the environment. These actions will better meet the needs and interests of villagers and enhance the sustainability and adaptability of improvement measures. Therefore, when formulating strategies to improve the habitat of traditional villages, it is necessary to understand the logic of village self-organization, combine the cultural and social characteristics of the village, make use of the existing conditions of social organization within the village, and meet the needs of the villagers as far as possible, while controlling the overall appearance. Through the joint creation of “government + villagers + society,” we can explore effective forms of villagers’ participation, realize the local nature of the national conservation policy, respect the local values of the village, and promote the return and development of the village’s living culture.

6. Conclusions

Data analysis shows that villagers have the highest demand for conserving traditional buildings, which is the top improvement need. At the same time, roof improvements, toilets, and kitchens are at the top of the priority list. Due to the rapid development of urbanization, traditional agricultural production can no longer sustain the primary livelihood of villagers. As a result, many villagers have chosen to go out to work, leaving the village in a “hollow village” situation [43,44,45,46,47]. Many of the remaining ancient buildings have been left without human management and repair for a long time, resulting in increasing deterioration of the buildings, which has damaged the overall appearance of the buildings to a great extent and affected the comfort of the residents. In addition, the installation of daycare centers for the elderly and the provision of communal landscaping in front of and behind the houses in the village public spaces can effectively increase the villagers’ satisfaction. After satisfying the basic physiological level, people’s needs for psychological and emotional levels also gradually emerge [48], and they have higher requirements for the environmental quality of village spaces. Some studies have shown that high-quality village spaces can create a sense of place and spatial belonging and unite villagers’ cultural identity [16,49,50]. The model of villagers’ co-creation workshops reflects a paradigm shift in traditional urban and rural planning, changing the traditional top-down, government-led mechanism of planning and allowing villagers to participate in the improvement of the village environment through the workshop model, enhancing villagers’ sense of participation and happiness in creating a better home together [51], and gathering villagers’ sense of cultural identity.

Strategic planning for village development focuses on economic growth and sustainable development [52,53]. In the post-epidemic era, people are demanding a healthier and more comfortable life [54,55], and along with the revitalization of China’s countryside, there is a clear trend of people returning home from work, which means that sustainable improvement of village habitats is urgent. The sustainable improvement of the habitat of traditional villages is vital for improving villagers’ satisfaction with their lives, stimulating their participation and motivation, and enhancing the economic vitality of villages. This system can be used to assess the current situation of traditional village habitat and guide us in improving the quality of traditional village habitat, as well as helping us to prioritize the improvement of traditional village habitat, to scientifically plan the construction of traditional village habitat, and to create a livable village living environment so that villagers can experience a more humane, comfortable and convenient living environment. The village is a vital place to live.

It is only by understanding the internal logic of village development and its role in the bottom-up and top-down processes that we can adopt policies for improving the habitat of traditional villages that are not one-size-fits-all and that take into account the various specificities of villages rather than rigidly transferring the experience of one place to another. We need to explore forms of autonomy suitable for village culture based on the empirical investigation to improve the living environment of traditional villages, to truly realize the sustainable development of traditional villages. However, our study also has some limitations. First, there are limitations in the scope of the study. Due to the difficulties and restrictions in distributing and collecting questionnaires, we only conducted surveys, distributed, and collected questionnaires in 112 traditional villages across three counties and cities. The study results cannot represent the true needs of residents in traditional villages across all of China. Additionally, since the remaining villagers are older and have limited cognitive abilities, some villagers may not fully understand the meaning of the questionnaire during on-site interviews. A significant portion of the collected questionnaires did not meet the standards. Future research should optimize the methods of questionnaire distribution and interviews, and expand the scope of the study and interviews.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.X. and Y.X.; methodology, Y.X.; validation, L.Y.; investigation, L.X., L.Y. and Y.X.; resources, L.X.; data curation, Y.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.X. and L.Y.; writing—review and editing, L.X. and L.Y.; visualization, Y.X.; supervision, L.X.; project administration, L.Y.; funding acquisition, L.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by [Huazhong University of Science and Technology Cross-research Support Fund] grant number [2023JCYJ020]. And The APC was funded by [2023JCYJ020].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to that our questionnaire is anonymous and does not involve the disclosure of any personal information. Furthermore, our research does not involve human biological research.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the Data Availability Statement. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

References

- Tosics, I. Habitat II Conference on Human Settlements, Istanbul, June 1996. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 1997, 21, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-F.; Chiou, S.-C. Study on the Sustainable Development of Human Settlement Space Environment in Traditional Villages. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attractive Quality and Must-Be Quality|CiNii Research [EB/OL]. Available online: https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1572261550744179968 (accessed on 9 April 2023).

- He, L.; Song, W.; Wu, Z.; Xu, Z.; Zheng, M.; Ming, X. Quantification and integration of an improved Kano model into QFD based on a multi-population adaptive genetic algorithm. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2017, 114, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Zhou, M.; Bonenberg, W.; Ma, Z. Smart Eco-Villages and Tourism Development Based on Rural Revitalization with Comparison Chinese and Polish Traditional Villages Experiences. In Advances in Human Factors in Architecture, Sustainable Urban Planning and Infrastructure; Charytonowicz, J., Falcão, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 966, pp. 266–278. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Kong, Z.; Li, X. Research on the Spatial Pattern of Traditional Villages Based on Spatial Syntax: A Case Study of Baishe Village. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 295, 032071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-K. A Study on the Regional Revitalization through Regeneration and Utilization of Vacant Houses in Historic Village—Focused on the Traditional Housing Regeneration Project of Tambasasayama in Japan-. J. Korean Inst. Rural. Archit. 2020, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzuan, I.S.M.; Fukami, N.; Ahmad, Y. Incentives for the conservation of traditional settlements: Residents’ perception in Ainokura and Kawagoe, Japan. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2015, 13, 301–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-K. Analysis of Korea Traditional Villages Characteristics using GIS. J. Assoc. Korean Photo-Geogr. 2015, 25, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Q.; Aimar, F. How Are Historical Villages Changed? A Systematic Literature Review on European and Chinese Cultural Heritage Preservation Practices in Rural Areas. Land 2022, 11, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, A. Advances in the study of rural territorial system degradation. Chin. Agron. Bull. 2014, 30, 112–116. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhai, R. The geography of rural hollowing in China and the practice of remediation. J. Geogr. 2009, 64, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Chu, S.; Du, X. Safeguarding Traditional Villages in China: The Role and Challenges of Rural Heritage Preservation. Built Herit. 2019, 3, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L. The capital logic and cultural logic of revitalizing traditional villages and their governance orientation. Exploration 2021, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Sun, H.; Chen, B.; Xia, X.; Li, P. China’s rural human settlements: Qualitative evaluation, quantitative analysis and policy implications. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 105, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, H.; Chen, J.; Wang, C.; Xu, W.; Tang, J. Social Network, Sense of Responsibility, and Resident Participation in China’s Rural Environmental Governance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, S.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Z.; Vessio, G. Correlation Study between Rural Human Settlement Health Factors: A Case Study of Xiangxi, China. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 2484850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, L.; Ng, E.Y.Y. Evaluation of the social dimension of sustainability in the built environment in poor rural areas of China. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2018, 61, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilleard, C.; Hyde, M.; Higgs, P. The Impact of Age, Place, Aging in Place, and Attachment to Place on the Well-Being of the Over 50s in England. Res. Aging 2007, 29, 590–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Juan, Y.-K. Optimal decision-making model for exterior environment renovation of old residential communities based on WELL Community Standards in China. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2022, 18, 571–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Rabaiei, K.; Alnajjar, F.; Ahmad, A. Kano Model Integration with Data Mining to Predict Customer Satisfaction. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2021, 5, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobuj, M.; Alam, M.A.; Zannat, A. Evaluation of face masks quality features using Kano model and unsupervised machine learning technique. Res. J. Text. Appar. 2022, 27, 560–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potra, S.A.; Alptekin, H.D.; Pugna, A.; Kucun, N.T.; Ozkara, B.Y.; Pop, M.-D. Challenges in Testing the Kano Model’s Validity through Computer-Assisted Human Behaviour Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Technology and Engineering Management Conference (TEMSCON Europe), Izmir, Turkey, 25–29 April 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Materla, T.; Cudney, E.A.; Antony, J. The application of Kano model in the healthcare industry: A systematic literature review. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2019, 30, 660–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.A.; Johnson, J.C. Kano and other quality improvement models to enhance patient satisfaction in healthcare settings. J. Fam. Community Med. 2021, 28, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Guo, W.; Wang, L.; Rong, B. An analysis method of dynamic requirement change in product design. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 171, 108477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, K.; Han, S. Sustainable Design of Takeout Product Service System of Milk Tea Drinks in Chinese University Campus Based on KANO Model. In Sustainable Design and Manufacturing, KES-SDM 2021; Scholz, S.G., Howlett, R.J., Setchi, R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; Volume 262, pp. 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirgizov, U.A.; Kwak, C. Quantification and integration of Kano’s model into QFD for customer-focused product design. Qual. Technol. Quant. Manag. 2022, 19, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Chen, H.; Fang, Y.; Liang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Guo, Z.; Chen, H. Research on the Method of Acquiring Customer Individual Demand Based on the Quantitative Kano Model. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 5052711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ren, M.; Xiang, Z. Research on Users’ Satisfaction of App Interface of Mobile Phone Business Hall Based on Kano Model and Eye Movement Tracking. In Man-Machine-Environment System Engineering, MMESE; Long, S., Dhillon, B.S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; Volume 800, pp. 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, S. Research on Wearable Smart Products for Elderly Users Based on Kano Model. In Human Aspects of It for the Aged Population: Design, Interaction and Technology Acceptance, Pt I; Gao, Q., Zhou, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 13330, pp. 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; Zhang, Y. Analysis of MOOC Quality Requirements for Landscape Architecture Based on the KANO Model in the Context of the COVID-19 Epidemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujs, D.; Vrhovec, S.; Žvanut, B.; Vavpotič, D. Improving the efficiency of remote conference tool use for distance learning in higher education: A kano based approach. Comput. Educ. 2022, 181, 104448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinker, P.; Swarnakar, V.; Singh, A.; Jain, R. Prioritizing NBA quality parameters for service quality enhancement of polytechnic education institutes—A fuzzy Kano-QFD approach. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 47, 5788–5793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.-H.; Tsai, S.-B.; Lee, Y.-C.; Hsiao, C.-F.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J.; Shang, Z.; Deng, Y. Empirical research on Kano’s model and customer satisfaction. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.; Juan, Y.-K. Applying The DQI-based Kano model and QFD to develop design strategies for visitor centers in national parks. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2021, 19, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.; Gimpel, H.; Schnaak, F.; Wolf, L. Promoting Energy-Conservation Behavior in a Smart Home App: Kano Analysis of User Satisfaction with Feedback Nudges. In Proceedings of the ICIS 2022 Proceedings, Copenhagen, Denmark, 9–14 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Li, S.; Juan, Y.-K.; Wolf, L. A Kano–IS Model for the Sustainable Renovation of Living Environments in Rural Settlements in China. Buildings 2022, 12, 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yuan, L.; Tan, G. Identification and Hierarchy of Traditional Village Characteristics Based on Concentrated Contiguous Development-Taking 206 Traditional Villages in Hubei Province as an Example. Land 2023, 12, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Xu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Y. Traditional Village Clustered Protection and Utilization Methods Based on Network Science. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Zhao, J.; Zhao, X. Study on Planning Strategy of Urban Villages: With Lujiazhuang Urban Village as an Example. In Advances in Civil and Industrial Engineering, Pts 1–4; Tian, L., Hou, H., Eds.; Trans Tech Publications Ltd.: Zurich, Switzerland, 2013; Volume 353–356, pp. 2891–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.S.Y.; Hassan, N.; Ghaffarianhoseini, A.; Daud, N. The relationship between satisfaction towards neighbourhood facilities and social trust in urban villages in Kuala Lumpur. Cities 2017, 67, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xu, M. Characteristics and Influencing Factors on the Hollowing of Traditional Villages—Taking 2645 Villages from the Chinese Traditional Village Catalogue (Batch 5) as an Example. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Zhao, L.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, Z.; Jiang, H. Research on Hollow Village Governance Based on Action Network: Mode, Mechanism, and Countermeasures—Comparison of Different Patterns in Plain Agricultural Areas of China. Land 2022, 11, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Lv, Q. Multi-dimensional hollowing characteristics of traditional villages and its influence mechanism based on the micro-scale: A case study of Dongcun Village in Suzhou, China. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Liu, Y.; Xu, K. Hollow villages and rural restructuring in major rural regions of China: A case study of Yucheng City, Shandong Province. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2011, 21, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Woods, M.; Zou, J. Accelerated restructuring in rural China fueled by the ‘increasing vs. decreasing balance’ land-use policy for dealing with hollowed villages. Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, R.J.; Leung, H.H. Becoming a Traditional Village: Heritage Protection and Livelihood Transformation of a Chinese Village. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Construction of Sense of Place and Rural Governance: A Case Study of Chaoshan Ancestral Hall [EB/OL]. Available online: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/alldb/full-record/CSCD:6778922 (accessed on 9 April 2023).

- A New Perspective of China Rural Governance Based on Modernity and Identity—All Databases [EB/OL]. Available online: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/alldb/full-record/CSCD:6711531 (accessed on 9 April 2023).

- Xiao, S.Y.; Bai, S.J. Predicaments of Heritage of Rural Cultural Landscape During Urbanization and Its Solutions. In Architecture, Building Materials and Engineering Management, Pts 1–4; Hou, H., Tian, L., Eds.; Trans Tech Publications Ltd.: Zurich, Switzerland, 2013; Volume 357–360, pp. 2075–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćurčić, N.; Svitlica, A.M.; Brankov, J.; Bjeljac, Ž.; Pavlović, S.; Jandžiković, B. The Role of Rural Tourism in Strengthening the Sustainability of Rural Areas: The Case of Zlakusa Village. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Gu, J.; Li, M. Sustainability-Oriented Urban Resilience Assessment: The Case of China’s Yangtze River Delta Region. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 514, 145835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Adeney, M.; Long, H. Functional Settings of Hospital Exterior Spaces and the Perceptions from Public and Hospital Occupants during COVID-19. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, M.; Adeney, M.; Chen, W.; Deng, D.; Tan, S. To Create a Safe and Healthy Place for Children: The Associations of Green Open Space Characteristics With Children’s Use. Front. Public Health 2022, 9, 813976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).