Abstract

The “three rights separation” system plays a vital role in enhancing the economic efficiency of rural residential land use, thereby contributing to land revitalization and rural-urban integration. Using survey data from 456 farmers in Yujiang District and Deqing County, this study employs DEA, Tobit, and threshold regression models to analyze the system’s effects. The results show that the system improves economic efficiency by approximately 8.9%, primarily by incentivizing investment and promoting land transfers. A nonlinear threshold effect exists: investment incentives become significant only when idle land exceeds 35 m2, consistent with farmers’ economic decision-making. Land transfers enhance efficiency via marginal return equalization, however, economies of scale are not evident, being constrained by legal and coordination factors. The findings highlight the importance of deepening reform implementation, enhancing farmers’ understanding of property rights, adopting differentiated incentives tailored to land size and farmer capacity, and regulating the land transfer market to ensure transparency and fairness. Furthermore, promoting collective or service-based management models can help overcome natural scale limitations, thereby unlocking the system’s full institutional dividends.

1. Introduction

Rural areas have long served as the cornerstone of China’s socioeconomic development. As both the spatial carrier and material foundation of economic activity, land resource allocation and utilization efficiency are central to advancing agricultural and rural modernization. Since the start of reform and opening-up, rural-to-urban migration has accelerated, yet rural residential land has expanded despite a declining rural population declines [1]. Over 20% of this land is estimated to lie idle, largely because migrant workers keep their rural residential land as security against the uncertainties of urban integration [2]. This mismatch between land use and population not only exacerbates urban congestion and land scarcity but also significantly constrains rural revitalization [3,4]. Improving the allocation of rural residential land and raising its utilization efficiency have thus emerged as urgent policy priorities.

Globally, rapid urbanization has often led to “urban diseases”. As early as the 1950s, countries like the United States adopted counter-urbanization strategies to mitigate the social and economic challenges of urban congestion [5]. In the 21st century, similar dynamics have emerged in Chinese megacities such as Beijing and Shanghai. The Chinese government launched the rural revitalization strategy in 2018, positioning rural areas as engines of national development [6]. At its core, the strategy emphasizes rural industrial growth, which relies heavily on the availability and efficient use of land resources [7]. Therefore, unlocking the potential of idle rural residential land and aligning it with industrial functions has become a pressing policy and academic priority.

In the 20th century, the issue of “land fragmentation” attracted broad attention across Europe and North America, where farms were divided into numerous small, spatially dispersed plots that hinder agricultural productivity [8]. Scholars have traced its roots to private land tenure systems and inheritance laws [9]. In response, countries such as Germany, France, and the Netherlands launched systematic land consolidation programs [10], which strategically exchange and merge parcels to create contiguous holdings and enable large-scale farming [11,12,13]. In some Western European countries, these efforts extended to rural residential land reorganization to improve the efficiency of land use and reduce idleness [14]. Throughout this process, European and North American countries adopted flexible approaches to land tenure adjustment. Unlike the Western model of private land ownership, China follows a system of socialist public ownership. This creates fundamental differences in land management institutions [15]. Even so, property rights systems remain a universal driver of efficient land use. Evidence from Europe and North America shows that complete property structures, flexible land use regulations, and open transfer mechanisms can greatly enhance land use efficiency. Against this backdrop, academic interest in the role of property rights reform in activating rural residential land has grown [16]. In 2018, China’s No. 1 Central Document proposed expanding the existing “separation of ownership and use rights” into a “three rights separation” system—including ownership, qualification rights, and use rights. This reform aims to clarify property structures, ease land use restrictions, promote optimal allocation, and unlock the asset value of rural residential land to support rural industries. Clearly, improving the economic efficiency of rural residential land use has become a core objective of the “three rights separation” system provided that farmers’ residential rights are secured.

Since the launch of the “three rights separation” system, scholars have debated its rationale, institutional design, and implementation challenges [17,18,19]. Proponents emphasize three main advantages. First, by relaxing land use restrictions, the system encourages farmers to participate in non-agricultural industries, thereby enhancing their investment incentives [20]. Second, clearer property structures make rural residential land easier to transfer [21]. Third, the system incentivizes collective economic organizations to utilize idle rural residential land to develop industries [22], thereby exerting a driving effect on farmers [23]. However, dissenting opinions also exist. Some scholars argue the system’s incentive effects are weaker than expected, citing policy lags, long investment horizons, and heterogeneity among farmers [24,25]. While delays and slow returns explain part of the problem, they do not fully account for the underperformance. Recent studies suggest the core issue lies in farmer heterogeneity. Farmers differ greatly in capabilities, willingness, and resource endowments [26], leading to uneven levels of land use efficiency [27]. Regrettably, few studies have examined this issue in detail. Another significant obstacle is the persistence of the endowment effect. As property rights become more clearly defined, farmers’ emotional attachment to their rural residential land tends to increase. This raises their expectations for rental returns and increases resistance to land transfer [22]. This suggests the transfer of land is not driven solely by economic rationality but is also influenced by complex cognitive and emotional logics [22,28]. In response, some scholars advocate for enhanced policy communication and cognitive interventions to correct farmers’ misperceptions [22]. These measures may encourage participation, but they do not remove the transaction costs associated with the endowment effect. Instead, such costs are shifted to governments and collective organizations in various forms. This underscores the need for deeper adjustments to the property rights structure itself—an approach rarely highlighted in the current literature.

Most existing studies have focused on land transfers, income effects, or the collective economy. While some evidence supports the positive impact of the “three rights separation” system, directly evaluating its effectiveness in improving the efficiency of rural residential land use remains a challenge. This challenge contributes to the divergent findings in the literature. Although some studies have examined whether land is being used, binary assessments overlook the complex mechanisms behind land use decisions.

As a result, research has increasingly shifted toward assessing rural residential land use efficiency, particularly its social and economic dimensions [29]. This study builds on that foundation by focusing on economic efficiency, a dimension that remains underexplored in the context of the “three rights separation” system. To address this gap, this study develops an analytical framework that links the two together. Specifically, this study explores two key questions: (1) Can the “three rights separation” system enhance the economic efficiency of rural residential land use? (2) Through what mechanisms does it influence economic efficiency? By answering these questions, the study aims to offer insights for the optimization of the “three rights separation” system and improve the economic utilization of rural residential land.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 develops the theoretical framework and formulates the research hypotheses. Section 3 describes the data, variables, and empirical strategy. Section 4 presents the main results. Section 5 discusses the key findings and policy implications. Section 6 concludes with a summary and future research directions.

2. Theoretical Framework

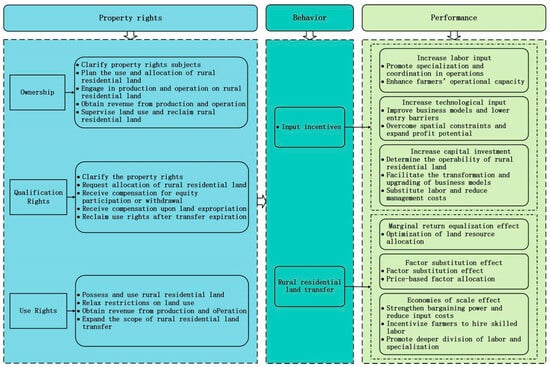

Effective institutional arrangements can define property rights, stimulate investment, and reduce transaction costs, which in turn improve economic performance [30]. The implementation of the “three rights separation” system has sparked widespread discussion on how clearer property rights can unlock the latent value of rural residential land. A prevailing view holds that clarified property rights enhance the economic value of rural residential land and increase farmers’ asset-based income [31]. However, even under the earlier “two rights separation” system, when boundaries were blurred, some farmers still managed to utilize rural residential land resources. This indicates that efficient property institutions depend not only on the delineation of rights but also on their effective implementation. The “three rights separation” reform aligns with this logic. Based on this understanding, this study constructs an analytical framework following a “property rights–behavior–performance” logic. It examines how the “three rights separation” system affects the economic efficiency of rural residential land use through property rights delineation and implementation.

2.1. The Connotation of the “Three Rights Separation” System

A thorough examination of the relationship between the “three rights separation” system and the economic efficiency of rural residential land use requires, as a first step, a clear understanding of the system. In 2018, the central government introduced the ”three rights separation” system reform. Its goals were to increase farmers’ property income, revitalize idle rural residential land, and stimulate rural development. This reform builds on the two rights separation framework established in 1962. It restructures rural residential land properties into three components: ownership, qualification rights, and use rights. The core of the reform is to refine the division of rights and optimize their functions. These can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

- Improving ownership. This system aims to address the weakening of the rural residential land ownership subject and explore ways to realize ownership effectively. It clarifies rural collective economic organizations as the sole holders of ownership and grants them legal authority over the planning, allocation, and adjustment of rural residential land [17]. This enhances their governance capacity in resource allocation and use efficiency [32].

- (2)

- Establishing qualification rights. Qualification rights grant members of rural collective economic organizations the legal entitlement to apply for rural residential land. This is a key step toward clarifying property rights. The system serves two main functions: (i) It guarantees farmers’ basic housing rights and helps maintain rural social stability, ensuring that every member “has a home to live in” [18] (ii) It separates qualification rights from use rights, allowing farmers to retain qualification rights while freely choosing to withdraw or transfer their use rights. Farmers who withdraw receive compensation and may reapply for rural residential land after a certain period, such as upon retirement or resettlement in the village. In cases of transfer, qualification rights are retained. This protects farmers’ legal interests, allows them to supervise the transferee’s land use, and ensures that use rights are unconditionally reclaimed if violations occur or when terms expire [32].

- (3)

- Liberalizing use rights. Under the “three rights separation” system framework, the holders of use rights are no longer restricted to members within the rural collective. Both the purposes of use and the channels for transfer have been gradually relaxed. Farmers can operate rural residential land themselves according to their capacity. They can also transfer use rights through leasing or sale [32,33]. This flexible design not only broadens the ways rural residential land can be used but also provides an institutional foundation for improving land use efficiency.

The innovation of the ”three rights separation” system lies not only in the finer definition of property rights but also in granting each category of rights holders greater authority. This represents a substantial breakthrough compared to the two rights separation stage. It is crucial to emphasize that ownership, qualification rights, and use rights are equally important in the system’s operation. Ownership secures the institutional foundation of collective land. Qualification rights guarantee members’ basic housing rights and the right to reclaim land after transfer. Use rights directly affect the utilization and allocation of rural residential land. These three rights complement each other and are indispensable. Only through their coordinated interaction can the optimal allocation and efficient use of rural residential land resources be achieved.

2.2. Definition of Economic Efficiency of Rural Residential Land Use

The economic efficiency of rural residential land use is a key metric for assessing the performance and outcomes of economic activities [34]. This concept stems from the economic functions attributed to rural residential land. In essence, economic use of rural residential land involves combining land with other inputs, such as labor and capital, to generate economic returns [35]. Accordingly, the economic efficiency of rural residential land use can be defined as the ability to achieve a given level of output under constrained inputs, or conversely, as the extent to which available inputs are optimally utilized to produce a fixed economic output.

2.3. The “Three Rights Separation” System, Input Incentives, and Economic Efficiency of Rural Residential Land Use

2.3.1. The Impact Mechanism of the “Three Rights Separation” System on Input Behavior

Following the implementation of the “three rights separation” system, first, in terms of property rights delineation, the definition of qualification rights and the issuance of property certificates clarify ownership boundaries, enhance perceived security and expected returns, reduce boundary disputes and protection costs, and ultimately strengthen farmers’ willingness to invest [21]. Second, in terms of property rights implementation, by liberalizing use rights, the “three rights separation” system promotes the development of rural residential land markets [32]. Under this institutional context: (1) Bidirectional flows of urban and rural factors enable farmers to access lower-cost production factors over a broader area, facilitating factor reallocation and expanding profit margins. (2) As land markets mature, farmers who subsequently shift to non-agricultural sectors can still recover part of their prior investments through market transactions, thus mitigating the risk of investment lock-in. (3) The inflow of advanced technologies and managerial concepts further improves farmers’ production and operational capabilities. These mechanisms collectively strengthen farmers’ incentives to invest in the utilization of rural residential land.

2.3.2. The Impact Mechanism of Input Levels on the Economic Efficiency of Rural Residential Land Use

Drawing on the existing literature [29], this study identifies labor, technology, and capital as the core inputs enabling economic activities on rural residential land. Specifically, labor includes household members, surplus rural labor, and high-quality labor such as returning migrants or urban entities. Technology refers to advanced tools and practices that improve operational efficiency, while capital encompasses the equipment and infrastructure required for production and service delivery. For example, homestay1 operations typically demand investments in accommodation amenities (e.g., air conditioners, televisions), bathing facilities (e.g., showers, toiletries), and kitchen equipment (e.g., stoves, cookware).

The relationship between input levels and economic efficiency can be summarized as follows: (1) Labor input enables task specialization and role differentiation, promoting professionalism and coordination in operations [29]. The involvement of high-quality labor enhances specialization, builds capacity among local farmers, and improves the quality and efficiency of economic activities. (2) Technology serves a dual function: it modernizes traditional production models and lowers entry barriers, while digital tools, in particular, help overcome geographic constraints and expand market access, thus improving economic returns [32]. (3) Capital is fundamental to enabling operability. Economic activities not only require space (i.e., land and housing) but also demand essential operational facilities. Capital thus determines whether land can be effectively used for business purposes [36]. Moreover, investment in specialized assets facilitates the shift from informal, household-based activities to more structured micro-enterprises. This transition enhances labor productivity, standardizes processes, and ensures more stable service delivery [37]. Capital can also substitute for labor, easing constraints from labor shortages and reducing the costs of monitoring opportunistic behavior such as shirking [29]. Collectively, these inputs contribute to the improvement of economic efficiency in the use of rural residential land.

2.4. The “Three Rights Separation” System, Rural Residential Land Transfer, and Economic Efficiency of Rural Residential Land Use

2.4.1. The Impact Mechanism of the “Three Rights Separation” System on the Transfer of Rural Residential Land

Rural residential land transfer is a key breakthrough under the “three rights separation” system. From the property rights delineation perspective, the system clarifies income entitlements and responsibility boundaries. This enhances the perceived security of both transferring farmers and transferees, lowers negotiation and contract enforcement costs, and facilitates successful transactions [38]. Additionally, allowing non-collective members to obtain use rights, breaks the traditional restriction whereby rural residential land could only be transferred within the collective [39]. From the property rights implementation perspective, first, the system empowers collective economic organizations with clear rights, enabling them to reclaim idle or over-occupied rural residential land [40], thereby encouraging more rational land use. Second, as collective organizations are entitled to a share of value appreciation from rural residential land transfers, their initiative is stimulated. This motivates them to actively participate in establishing and improving transaction platforms to ensure orderly transfers [33]. Third, qualification rights allow farmers to supervise land use and reclaim land at the expiration of transfers, mitigating “land loss” risks [41]. Moreover, the system grants greater contractual freedom, enabling both parties to agree on flexible revenue-sharing arrangements, which increases returns for both farmers and transferees and incentivizes optimal rural residential land utilization [42]. As land use regulations are moderately relaxed, rural residential land can accommodate new industries and business models, boosting the market value of use rights and further encouraging rural residential land transfers.

2.4.2. The Impact Mechanism of the Transfer of Rural Residential Land on the Economic Efficiency of Rural Residential Land Use

Through rural residential land transfers: First, rural residential land is reallocated to actors with stronger operational capabilities [28], a process known as the marginal return equalization effect. Second, rural residential land transfers improve local factor endowments, making advanced technologies, capital, and management practices more accessible. Farmers and operators reoptimize input portfolios based on market signals, thereby enhancing production efficiency and lowering input costs [43]. This is the factor substitution effect. Third, given the “integration of land and house” property of rural residential land, expansion of operational scale largely depends on the transfer of use rights. As operational scale increases, first, larger procurement volumes improve farmers’ bargaining power, securing better input prices and reducing unit costs. Second, operational expansion demands greater specialization, prompting farmers or new operators to recruit higher-skilled labor, fostering deeper division of labor, increasing labor productivity, and enhancing operational efficiency [29], this is the economies of scale effect.

Based on the theoretical framework above (Figure 1), this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Figure 1.

The mechanism of the “three rights separation” system on the economic efficiency of rural residential land utilization.

Hypothesis 1.

The “three rights separation” system can improve the economic efficiency of rural residential land use.

Hypothesis 2.

The “three rights separation” system enhances economic efficiency by stimulating input incentives.

Hypothesis 3.

The “three rights separation” system enhances economic efficiency by promoting rural residential land transfer.

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Study Area

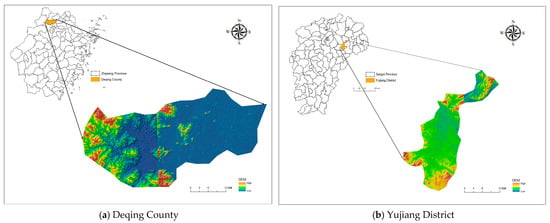

This study focuses on Yujiang District in Jiangxi Province and Deqing County in Zhejiang Province. Deqing is located in eastern coastal China, close to Shanghai and Hangzhou, and enjoys convenient transportation links, which reduces the cost for rural farmers to seek employment in cities. Yujiang is located in central China, where traditional agriculture still prevails and many farmers seek employment outside their hometowns. Both regions experience widespread idleness of rural residential land, which creates favorable conditions for land transfers. In addition, Deqing and Yujiang are pilot areas for China’s rural residential land reform and have accumulated extensive experience in policy innovation and practical experimentation. Deqing was among the first counties to pilot the “three rights separation” system. It was an early issuer of property rights certificates and established a relatively comprehensive system for the confirmation, registration, and transfer of land rights. In developing rural tourism, Deqing utilized idle land for homestays and agritainment, becoming a model for integrating land reform with rural revitalization. During its second round of land reform, Yujiang explored a reform path known as “one reform promoting six transformations”. It promoted the withdrawal, exchange, and transfer of rural residential land through diverse approaches and developed replicable and scalable practices, particularly in mechanisms for paid land exit and market-based transfers. These experiences provide valuable insights for further research.

Yujiang District, located in China’s traditional central region, exhibits a moderate level of economic development and a high proportion of rural labor migration, reflecting characteristics common to much of rural China. Deqing County, situated in the economically developed eastern coastal area, also has a share of migrant workers, while some farmers actively engage in production and business activities on their homesteads. Both regions possess practical foundations for transferring or utilizing rural residential land for economic purposes. Together, their differing economic contexts and shared patterns of rural land use make them broadly representative of rural conditions in China (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The study area.

3.2. Data

The data used in this study were collected through household surveys conducted by the research team in Deqing County (Zhejiang Province) and Yujiang District (Jiangxi Province) in January 2022 and January 2024. A stratified multistage random sampling approach was employed, taking into account factors such as rural residential land use, village economic development, and the progress of land reform. In each county, seven to eight townships were selected, followed by eight to ten villages in each township, and twelve to fifteen households in each village were surveyed using structured questionnaires. The questionnaire covered a wide range of topics, including respondents’ personal characteristics, household information, and features of rural residential land and housing. For the purposes of this study, a sample of 456 households engaged in economic activities on rural residential land was retained—278 from Deqing and 178 from Yujiang. Additional information on village characteristics was obtained from publicly available village documents.

The analysis of the basic characteristics of surveyed households shows that 81.14% of respondents are between 30 and 70 years old. In terms of gender distribution, females account for 57.68%, compared to 42.32% for males. With regard to occupational experience, only 19.52% of respondents have served as grassroots cadres; this subgroup tends to have a better understanding of the “three rights separation” system. Households are generally large, with 92.98% consisting of five to seven members. The distribution of rural residential land area is relatively concentrated: about half of the surveyed households hold plots between 100 and 200 m2, followed by those in the 200–300 m2 range. Regarding housing conditions, approximately 35.75% of respondents own homes in urban areas, which may influence their willingness and strategies for utilizing rural residential land.

3.3. Variables

Given that this study relies on cross-sectional survey data, traditional differences-in-differences (DID) models or their extensions are not directly applicable for causal identification. However, field survey results reveal significant variation in farmers’ perceptions of the “three rights separation” system, which are associated with differences in the economic efficiency of rural residential land use. This suggests that, following the rollout of the system, farmers with differing levels of perception experienced distinct changes in land use efficiency compared to the pre-implementation period (prior to 2018). Accordingly, this study examines the relationship between two change variables—changes in perception of the “three rights separation” system and changes in the economic efficiency of rural residential land use—to identify the system’s impact. It is important to note that because the “three rights separation” system was introduced in 2018, farmers’ perceptions were effectively zero at baseline. The perception measured at the time of the survey thus captures the change over time, serving as a proxy for the system’s implementation.

The variables are defined as follows:

(1) Dependent variable: economic efficiency of rural residential land use

To measure the economic efficiency of rural residential land use, this study adopts a super-efficiency Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) model. Traditional BCC models often classify multiple decision-making units (DMUs) as efficient, failing to capture efficiency variations among them; the super-efficiency DEA approach resolves this limitation. Input Variables: Based on prior studies and considering data availability and validity [29], three categories of inputs are selected: Land Inputs, measured by the area of rural residential land and the area of housing. Labor Inputs, measured by the number of labor inputs. Capital Inputs include expenditure on productive assets, expenditure on renovation and repairs, annual electricity cost, annual water cost, average annual fuel cost. The output variable is measured in terms of operating revenue (Table 1).

Table 1.

Evaluation index system of economic efficiency rural residential land use utilization.

(2) Core independent variable: “three rights separation” system

The perception of the “three rights separation” system among farmers is used to represent policy. The ability of a property rights system to motivate its holders depends not on the timing of its introduction or formal implementation, but on when the rights holders genuinely perceive the system and its effects. Following methods from prior research [44], perception is quantified through survey questions specifically designed to capture understanding of collective ownership, qualification rights, and use rights: A set of questions based on the functional attributes of the three rights was constructed. Respondents evaluated their understanding using a Five-point Likert Scale. The entropy method was used to assign weights to each question (as shown in Table 2). Farmers’ perceptions of each component (collective ownership, qualification rights, and use rights) were aggregated using weighted sum. As mentioned earlier in Section 2.1, since each right holds equal importance within the “three rights separation” system, equal weights (1/3) were assigned during aggregation. In terms of questionnaire design, this study simultaneously considers both self-use and land transferred in. Because farmers who transfer out their rural residential land generally no longer reside in the village, which makes direct interviews challenging, two separate sets of questions were designed: one for local farmers and another for farmers who have transferred in. The questionnaire for local farmers focused on their perceptions of land use, residential stability, and community integration, while the one for transferred farmers emphasized their motivations for relocation, experiences with land acquisition, and adjustments to new living environments. To ensure comprehensive data collection, structured interviews were conducted with village leaders and local government officials to gather insights into the broader policy context and its implementation at the grassroots level.

Table 2.

Measurement of the “three rights separation” system.

(3) Control variables

To minimize omitted variable bias, control variables were selected based on prior studies [22,23,33] and field observations. These cover: individual characteristics, household characteristics, rural residential land and housing characteristic, village-level characteristic.

(4) Mechanism variables

Input incentives: Measured by farmers’ self-reported changes in investment behavior, based on responses to the question: “Have you increased your investment in production or business activities?” Rural residential land transfer: Given that transfer-out farmers generally no longer reside locally, and transfer-in and transfer-out are simultaneous, land transfer is measured by asking: “Have you transferred in rural residential land?” Both mediating variables are constructed as binary variables.

The specific information regarding the variables can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Evaluation index system of rural residential land production efficiency.

3.4. Model

3.4.1. Tobit Regression Model

Since the efficiency values of the decision-making units calculated using the super-efficiency DEA model are all greater than zero and constitute truncated data, the Tobit model is used to estimate the impact of the “three rights separation” system on the economic efficiency of rural residential land use. The specific model construction is as follows:

In Equation (1), represents the economic efficiency of rural residential land use, represents the “three rights separation” system, represents the control variables, represents the regional fixed effects, is the intercept term, is the parameter to be estimated, and is the random disturbance term.

3.4.2. Binary Logistic Regression Model

In testing the mechanism of the “three rights separation” system, following related research [44], we directly examine the relationship between the “three rights separation” system and the mechanism variables. Since the mechanism variables are binary response variables, a binary logistic regression model is employed for analysis. The specific model construction is as follows:

In Equation (2), represents the mechanism variables, is the regression coefficient, and represents the log odds ratio increment caused by a one-unit increase in the core explanatory variable, the “three rights separation” system. is the random disturbance term.

3.4.3. Threshold Regression Model

This study applies a threshold regression model suitable for cross-sectional data [45,46], with its basic form as follows:

In Equations (3) and (4), and represent the economic efficiency of rural residential land use and the “three rights separation” system, respectively, and represents the threshold variable—the area of idle rural residential land, measured by “the area of idle rural residential land in 2018”. Based on the threshold value corresponding to the threshold variable , the research sample is divided into two groups. The regression coefficients for each group are represented by and , with representing the random disturbance term.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Results of Economic Efficiency of Rural Residential Land Use

This study uses DEA-Solver Pro 5 software to measure the economic efficiency of rural residential land use. The results show that the maximum observed change in economic efficiency is 1.686, the minimum is 0.220, and the average is 0.690. Using the mean value of farmers’ perception of the “three rights separation” system (0.422) as the threshold, the sample is divided into two groups. A comparison shows that for farmers with perception levels above the mean, the maximum change in the economic efficiency of rural residential land use is 1.324, the minimum is 0.616, and the average is 0.885. In contrast, for farmers with perception levels below the mean, the maximum change is 1.003, the minimum is 0.026, and the average is 0.697. These findings provide preliminary evidence supporting Hypothesis 1.

4.2. Baseline Regression Analysis

Regression analysis is conducted using Stata 16.0. Table 4 presents the baseline estimation results of the impact of the “three rights separation” system on the economic efficiency of rural residential land use. Column (1) includes only the “three rights separation” system, while columns (2)–(5) sequentially add control variables. As more control variables are added, the model’s explanatory power increases, indicating that the baseline regression model constructed in this study has reasonable explanatory power. The results show that, regardless of the inclusion of control variables, the coefficient of the “three rights separation” system remains significantly positive at the 1% level. This indicates that the “three rights separation” system promotes the economic efficiency of rural residential land use, thus supporting Hypothesis 1. The following analysis takes the regression results from column (5) as the baseline.

Table 4.

Benchmark regression results.

4.3. Robustness Test

Two approaches are used to verify the robustness of the results: First, we replace the efficiency measurement method. Instead of the super-efficiency DEA model, a traditional input-oriented DEA model is employed, followed by Tobit regression analysis. Second, we replace the key independent variable. Instead of the perception score, we use whether the farmer has received a rural residential land title certificate as a proxy for the “three rights separation” system. The results in Columns (6) and (7) consistently show that the “three rights separation” system significantly improves the economic efficiency of rural residential land use, confirming the robustness of the main findings (Table 5).

Table 5.

The results of robustness test.

4.4. Endogeneity Tests

To address potential endogeneity arising from simultaneity or sample selection bias between the “three rights separation” system and the economic efficiency of rural residential land use, the following strategy was employed. First, an instrumental-variable (IV) approach was adopted, using the proportion of surrounding farmers known to have obtained property rights certificates as the instrument. The relevance condition is satisfied because, due to peer effects, farmers’ perception of the proportion of property rights and certificates issued to surrounding farmers influences their perception of the “three rights separation” system. The exogeneity condition is satisfied because there is no direct correlation between farmers’ perception of surrounding property rights and certificates and the efficiency of their own homestead utilization. The first-stage regression indicates that the Wald F-statistic for the instrument well exceeds the Stock-Yogo 10% critical value of 16.38, suggesting no weak-instrument problem. Moreover, the instrument’s coefficient is significantly positive at the 1% level, further supporting its validity (Table 6).

Table 6.

Regression results of collective trusteeship on the efficiency of rural residential land utilization after introducing instrument variables.

Second, we address potential sample selection bias using propensity score matching (PSM). After matching, the standardized differences for covariates are all below 10%, and t-tests show no significant systematic differences between treated and control groups. We estimate the average treatment effects (ATT) using nearest neighbor matching, caliper matching, and kernel matching (Table 7).

Table 7.

Regression results of PSM.

Overall, even after addressing endogeneity concerns, the positive effect of the “three rights separation” system on rural residential land use efficiency remains robust, providing further support for Hypothesis 1.

4.5. Mechanism Tests

4.5.1. Mechanism I: Input Incentives

The baseline regression confirms that the “three rights separation” system positively impacts the economic efficiency of rural residential land use. This section further examines whether the system effectively stimulates farmers’ input incentives (Table 8).

Table 8.

Mechanism analysis 1: the impact of the “three rights separation” system on input level.

As shown in the regression results of Table 8, the “three rights separation” system does not significantly incentivize farmers’ input levels. In fact, the improvement of rural residential land operation performance relies on the coordinated allocation of land, labor, and capital elements. Strengthening the input of only one element, while other elements remain unmatched, may even suppress performance growth [26]. Although technology and capital inputs play important roles in enhancing operational benefits, their high costs, asset specificity, and the legally restricted area of rural residential land limit the full realization of their effectiveness. Therefore, the incentive effect of the “three rights separation” system may be constrained by the area of residential land. Related studies also point out that small-scale operations tend to cause excessive investment in specific assets, thus increasing factor costs and weakening farmers’ willingness to invest [29]. In other words, the incentive effect of the “three rights separation” system on factor inputs may only emerge after the residential land area surpasses a certain threshold. Based on this, this study adopts a threshold regression model suitable for cross-sectional data to verify this relationship (Table 9). The results show that the single-threshold effect passes the 1% significance level test. A nonlinear relationship between the “three rights separation” system and input levels is thus confirmed, with a threshold value of 35 m2.

Table 9.

Regression results of threshold for idle rural residential land area.

Based on the threshold effect test, this section divides the sample into two groups using 35 m2 as the threshold and estimates the impact of the “three rights separation” system on input levels separately (Table 10). When the area of idle rural residential land in 2018 is less than or equal to 35 m2, the system does not significantly incentivize input behavior. When the area exceeds 35 m2, the incentive effect begins to emerge, confirming the earlier analysis, supporting Hypothesis 2. With the continued advancement of urbanization and industrialization, the opportunity cost of staying in rural areas rises. In this context, the relative relationship between the returns from rural residential land-based operations and opportunity cost becomes a key factor influencing labor allocation. In theory, when land-based returns exceed opportunity costs, labor is more likely to remain in rural areas and engage in productive activities. In practice, however, small-scale operations impose significant limitations on industrial upgrading and economic performance. Limited scale restricts specialization and collaboration, resulting in constrained professionalization and surplus labor. It also amplifies the specificity and indivisibility of capital assets. For example, specialized equipment used in homestay operations often exhibits low utilization rates due to seasonal or cyclical fluctuations, generating high sunk costs. Furthermore, capital indivisibility becomes more prominent at small scales, and the low marginal productivity of capital suppresses farmers’ investment incentives. As the area of idle residential land increases, these constraints gradually diminish, and the incentive effect becomes more evident. Expanding operational scale facilitates the spreading of fixed costs associated with advanced technologies and specialized assets, thereby increasing the marginal productivity of capital. It also supports professional division of labor and collaboration, enabling labor allocation according to comparative advantage and forming more efficient production organizations. For instance, in homestay operations, tasks such as front-desk reception, room management, and food service can be assigned based on functional needs. A clear division of responsibilities and effective coordination not only reduces labor redundancy but also improves service quality and operational outcomes. More importantly, larger operational scale partially alleviates the limitations posed by capital indivisibility and reduces investment risks for farmers. Operational land areas are generally smaller than the standard allocation of rural residential land. For example, 80 m2 for two-person households in Yujiang District and 90 m2 for 2–3 person households in Deqing County. This supports the validity of the threshold value estimated in this study.

Table 10.

The impact of the “three rights separation” system on input under different land-size intervals.

4.5.2. Mechanism II: Rural Residential Land Transfer

This section further examines whether the “three rights separation” system promotes rural residential land transfer (Table 11). The “three rights separation” system significantly promotes land transfer at the 1% level. This indicates that by clarifying property rights and empowering the exercise of use rights, the system facilitates the development of rural residential land markets. Under this environment, market mechanisms can more effectively optimize rural residential land allocation and improve economic efficiency. These findings provide empirical support for Hypothesis 3.

Table 11.

Mechanism analysis 2: the impact of the “three rights separation” system on the rural residential land transfer.

According to the theoretical analysis presented earlier, rural residential land transfer can generate three main effects: the marginal return equalization effect, the economies of scale effect, and the factor substitution effect. Among these, the first two can be directly realized through land transfer. The following analysis focuses on elucidating the transmission mechanisms through which land transfer enhances economic efficiency. Drawing on relevant studies [47,48], the marginal return equalization effect is tested using three indicators: output per unit area, labor productivity, and capital productivity. Specifically, output per unit area is measured as the ratio of rural residential land operating revenue to rural residential land area; labor productivity is calculated as operating revenue per labor input; and capital productivity is expressed as operating revenue per unit of capital investment. The economies of scale are assessed by evaluating changes in land area indicators before and after rural residential land transfer. As shown in Table 12, rural residential land transfer demonstrates a significant marginal return equalization effect, but no evidence of an economies-of-scale effect is observed. In theory, scale farming can expand profit margins. However, its promotion faces two main challenges in practice. First, farmers’ strong attachment to rural residential land leads them to raise transfer prices, which increases transaction costs. Moreover, the spatial fragmentation of rural residential land makes it difficult to achieve contiguous land use even when transfers occur. Second, during the two rights separation period, the ownership subject was vague for a long time. This limited the collective economic organizations’ ability to effectively coordinate land revitalization. As a result, individual farmers often lack unified planning in land use, making it hard to align with overall village development strategies. This situation diminishes the potential to realize scale and synergy effects. Addressing these problems is a key focus of the “three rights separation” system. These results also support the validation of this study’s hypothesis: although the “three rights separation” system does not effectively promote scale effects, it still enhances marginal productivity. This indicates that the primary pathway through which land transfer improves efficiency is the marginal return equalization effect, consistent with findings in related research [48].

Table 12.

Further discussion on the rural residential land transfer.

5. Discussion

5.1. Main Findings

Improving the economic efficiency of rural residential land use is a critical goal of China’s rural revitalization strategy and a core objective of the “three rights separation” system. Based on survey data from 456 rural households in Jiangxi and Zhejiang provinces, this study employs super-efficiency DEA, Tobit, and threshold regression models to investigate how the reform influences the economic efficiency of rural residential land.

The incentive and resource allocation effects of property rights systems have long been central topics in property rights economics [49,50,51]. Extensive international studies show that clear and enforceable property rights can effectively improve land use efficiency. This finding is supported not only in developed countries but also in land reforms in developing countries like India and Ethiopia [52,53,54]. Our empirical analysis also finds that the “three rights separation” system helps enhance the economic efficiency of rural residential land use. This provides Chinese evidence for global reforms of property rights and resource allocation. Further analysis reveals that the input incentive effect of the “three rights separation” system has a threshold related to land area. The relationship between the two is nonlinear. Although this phenomenon is rarely discussed directly in existing literature, it aligns well with farmers’ behavioral logic. Our findings reveal a threshold effect: the incentive of the “three rights separation” system emerges only when the area of rural residential land exceeds a certain level. While this conclusion may differ from some prior studies, it is consistent with farmers’ economic decision-making logic. Specifically, engaging in economic activities on rural residential land typically requires large investments in specialized assets (e.g., homestay facilities, food service equipment), which are indivisible [29]. When the scale of rural residential land is small, high fixed costs cannot be effectively spread, making investments economically unjustifiable. In such contexts, rational and risk-averse farmers tend to withhold investment. When rural residential land reaches a sufficient scale, economies of scale reduce unit costs, increase expected returns, and lower investment risks, thus encouraging investment. This supports the assumption of rational farmer behavior [55]. Our findings help reconcile previous inconsistent conclusions. These results indicate a need for differentiated policy approaches.

Further studies generally agree that clear property rights help promote land market development and optimize land resource allocation. For example, land registration reforms in Kenya and Tanzania granted farmers stable land rights. This reduced transaction uncertainty and encouraged land transfers and investment [56,57,58]. This study further shows that the effects of the “three rights separation” system stem from both the clarification and implementation of property rights. Some studies suggest titling may reinforce emotional attachment and inflate land value expectations, we find that a transparent and efficient rural land market can mitigate this issue. Clear property rights provide the institutional foundation for functioning land transactions, rather than obstructing market development. Although property clarification may cause short-term overvaluation of the rent or reluctance to transact, the overall impact of the reform is to improve resource allocation and facilitate rural residential land transfers. This reinforces mainstream perspectives on institutional economics [38], and suggests “three rights separation” system is a pragmatic institutional reform in China’s rural context. For countries that retain collective or state ownership of land, China’s “three rights separation” system offers valuable insights into how to enhance the economic efficiency of rural residential land use. As such, it stands as a policy innovation from China that may serve as a useful reference for similar institutional contexts.

However, the findings reveal a new policy dilemma. The reform’s investment incentive effect materializes only when land exceeds the threshold size. While the “three rights separation” system empowers actors with stronger financial and operational capacity to lease land and develop economic activities based on their comparative advantages, it has not yet resulted in evident economies of scale. This limits the reform’s full potential. The legally prescribed size of homesteads restricts expansion [41], and the “integration of land and house” property of rural residential land means that even adjacent plots face high coordination costs when using specialized assets across locations. To overcome these challenges, some operators lease multiple homesteads for distinct functions (e.g., lodging, dining, agricultural exhibitions), creating a complementary division of labor. This reflects the neoclassical view that economies of scale often arise not from mere expansion, but from deeper specialization and division of labor [59]. However, achieving effective scale still depends on whether operators possess comparative advantages [60]. Rural residential land use involves multiple business types (e.g., lodging, food service, marketing). Operators without sufficient experience or skills may struggle to coordinate these diverse activities. This can lead to operational delays, poor customer experiences, and reduced profitability [29]. This underscores the equal importance of both property rights definition and implementation—an insight well supported by the broader literature [31]. Therefore, scale expansion alone does not guarantee improved efficiency. It is the interplay between operators’ capabilities and the quality of organizational arrangements that ultimately determines whether the reform delivers on its intended outcomes. This conclusion is empirically supported in both Chinese and international practice [61,62]. To ensure the reform achieves its intended outcomes, particular attention should be given to farmers with limited resources and weaker managerial capacity. Institutional reform must not merely amplify the advantages of strong actors, but should promote inclusive development through organized and collaborative approaches. Local governments, collective economic organizations, and specialized service providers should strengthen capacity-building efforts and institutional safeguards for less-advantaged farmers. This includes enabling cooperative operations, delegated management, and benefit-sharing models to unlock the value of idle rural residential land. Therefore, only through broad-based participation and strengthened inclusivity can the “three rights separation” system fully realize its intended institutional benefits.

5.2. Policy Suggestions

Based on the theoretical framework and empirical results of this study, the following policy recommendations are proposed to fully realize the institutional benefits of the “three rights separation” system and improve the economic efficiency of rural residential land use:

- (1)

- Deepen the “three rights separation” system and ensure effective implementation.

Our empirical analysis confirms that the “three rights separation” system indeed helps improve the economic efficiency of rural residential land use. Efforts should continue to consolidate land titling achievements, strengthen policy advocacy and practical guidance, and enhance farmers’ understanding of property boundaries, rights security, and expected returns. At the legal level, the property attributes and core entitlements of land use rights should be further clarified to provide stronger institutional guarantees. To facilitate efficient land transfer, a standardized and transparent trading platform should be established. Digital technologies can be leveraged to enable real-time information disclosure and online transactions. Collective economic organizations should play a key role in coordination and oversight, ensuring fairness and efficiency in the transfer process.

- (2)

- Adopt differentiated incentives to activate idle rural residential land.

Empirical analysis shows that the effects of the “three rights separation” system vary depending on farmers’ rural residential land endowments and their own capacities. Given the significant heterogeneity in land size and household resource endowments, policies should be tailored accordingly. For farmers with larger idle rural residential land, technical assistance and market intelligence should be provided to improve their operational capacity and risk resilience. For farmers with smaller plots, they should be encouraged to join specialized and centralized operational systems. Collective organizations or third-party service providers can offer unified operations to realize economies of service scale, improving resource efficiency and avoiding waste caused by fragmented small-scale operations.

- (3)

- Regulate the rural residential land transfer market and foster healthy development.

Promoting the transfer of rural residential land and achieving market-based allocation of these resources is not only a core goal of the “three rights separation” system but also a key step in improving the economic efficiency of rural residential land use. Market forces should be the primary mechanism for rural residential land allocation, while government should provide foundational institutional support, such as rent benchmarks and standardized contracts. Excessive administrative intervention should be avoided to prevent distortion of market signals. The contract enforcement and social oversight systems must be improved to reduce default risks and build market confidence. In addition, stricter regulation of capital entering rural areas is needed to prevent displacement of farmers by powerful market actors. Ensuring fair access and reasonable returns for farmers in land transactions is key to achieving genuine resource optimization and protecting rural livelihoods.

- (4)

- Promote service-based scale to overcome natural scale limitations.

Empirical analysis shows that although some farmers are willing to engage in production and business activities, legal limits on rural residential land area and the inseparability of houses and land restrict natural scale expansion. This constraint hinders improvements in the economic efficiency of rural residential land use. Given the legal restrictions on rural residential land area and “integration of land and house” property of rural residential land, a shift from natural scale expansion to service-based scaling is essential. This can be achieved through the integration of multiple rural residential plots by collective economic organizations, cooperatives, or specialized third-party service providers. Unified spatial planning, function-based division of labor, and outsourced professional operations should be encouraged to form cross-parcel and cross-stage collaborative business systems. Service-based scaling allows for more efficient allocation of production factors and deeper specialization, compensating for the limited size and managerial capacity of individual operators. It reduces factor input costs, improves overall operational efficiency, and ultimately unlocks the institutional dividends of the “three rights separation” system, thereby enhancing the economic efficiency of rural residential land use.

6. Conclusions

After securing farmers’ basic residential rights, improving the economic efficiency of rural residential land use is a logical and necessary goal of the “three rights separation” system—and a key driver of rural revitalization. Based on first-hand survey data from 456 farmers in Yujiang District and Deqing County, this study empirically investigates how the “three rights separation” system influences the economic efficiency of rural residential land use. Three main conclusions emerge: (1) The system significantly improves the economic efficiency of rural residential land. Specifically, its implementation leads to an average increase of approximately 8.9% in the economic efficiency of rural residential land. This finding remains robust after various statistical tests and endogeneity controls. (2) The “three rights separation” system enhances the economic efficiency of rural residential land use through input investment This relationship is non-linear: taking the idle rural residential land area in 2018 as the threshold variable, the incentive effect of the system will only be apparent when the area exceeds 35 m2. We found that the threshold value calculated in this article is in line with the actual situation through comparison with the standard for the allocation area of homestead land and existing research, which also indicates that the results of this article have practical display guidance significance. (3) The “three rights separation” system can promote the transfer of rural residential land and improve the economic efficiency of rural residential land use. During this process, the transfer of rural residential land has generated a marginal return equalization effect, but has not yet shown the economies of scale effect.

Nonetheless, this study is not without its limitations, which merit further discussion.

- (1)

- The size of the sample significantly influences the reliability and generalizability of the findings. Due to constraints in data collection—particularly those related to time and personnel—this research ultimately draws on 456 samples. While this sample size offers a degree of representativeness under current conditions, it falls short when considering the broader diversity of rural regions and household characteristics across China.

- (2)

- Given that rural residential land reform in China is still at the pilot stage, this study selected Deqing County in Zhejiang Province and Yujiang District in Jiangxi Province as research sites. As noted in Section 3.1, these two areas possess a certain degree of representativeness. The findings confirm the positive effects of the central government’s “three rights separation” system. However, considering China’s vast territory and significant differences in geography and socio-economic development, future research should include more pilot areas. This will help enhance the generalizability and representativeness of the results.

- (3)

- It should be noted that the implementation of the “three rights separation” policy was not randomly assigned. Therefore, the study results may be influenced by some unobserved factors, such as farmers’ skill levels, collective leadership capacity, and local development conditions. These factors could simultaneously affect farmers’ awareness of the policy and the efficiency of land use. This introduces potential endogeneity issues. Although the empirical analysis employed methods to mitigate these concerns, it is important to emphasize that a more precise validation of the conclusions is necessary once the “three rights separation” system is fully implemented.

- (4)

- This study uses cross-sectional data, which can reflect farmers’ characteristics and policy effects at a specific point in time. However, it cannot capture the dynamic changes in farmers’ behavior and policy impacts over time. A limitation of cross-sectional data is its inability to explain causal relationships and long-term trends across the time dimension. This is especially true for institutional reforms like the “three rights separation” system, whose effects often take time to fully manifest. Future research should focus on longitudinal surveys of farmers. Long-term and continuous data collection is needed to build panel data with extended time series.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft and investigation Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, supervision and funding acquisition, Y.H.; writing—review and editing, M.W.; formal analysis, investigation H.L. All of the authors contributed to improving the quality of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number 42171263), Ministry of Education of Humanities and Social Science Project (Grant number 21YJA630033), The Project of Department of Crop Management, Ministry of Agricultural and Rural Affairs, PRC (Grant numbers 152510008, 152410004).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

We obtained informed consent from all the subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Note

| 1 | Homestays in China are typically family-run accommodations that integrate lodging with local cultural, agricultural, or ecological experiences. They have become a key component of rural tourism and a tool for promoting rural revitalization. |

References

- Liu, Y. Introduction to land use and rural sustainability in China. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Zhan, L.; Jiang, G.; Ma, W.; Dong, X. How to Address “Population Decline and Land Expansion (PDLE)” of rural residential areas in the process of Urbanization:A comparative regional analysis of human-land interaction in Shandong Province. Habitat Int. 2021, 117, 102441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, W.; Li, Q.; Shi, H.; Xu, W.; Shao, Z. Effects of Spatial Accessibility on Farmers’ Willingness to Withdraw from Rural Homesteads in China. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2025, 151, 04025018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, C.; Dou, H.; Cheng, G.; Zhang, J.; Lei, X.; Huang, X. A strategy of building a beautiful and harmonious countryside: Reuse of idle rural residential land based on symbiosis theory. Habitat Int. 2025, 155, 103238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridding, L.E.; Watson, S.C.L.; Newton, A.C.; Rowland, C.S.; Bullock, J.M. Ongoing, but slowing, habitat loss in a rural landscape over 85 years. Landsc. Ecol. 2020, 35, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Gong, D.; Gong, Y. Index system of rural human settlement in rural revitalization under the perspective of China. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y. Revitalize the world’s countryside. Nature 2017, 548, 275–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janus, J.; Markuszewska, I. Land consolidation—A great need to improve effectiveness. A case study from Poland. Land Use Policy 2017, 65, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisec, A.; Primožič, T.; Ferlan, M.; Šumrada, R.; Drobne, S. Land owners’ perception of land consolidation and their satisfaction with the results—Slovenian experiences. Land Use Policy 2014, 38, 550–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, D.; Crecente, R.; Alvarez, M.F. Land consolidation in inland rural Galicia, N.W. Spain, since 1950: An example of the formulation and use of questions, criteria and indicators for evaluation of rural development policies. Land Use Policy 2005, 23, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupidura, A.; Łuczewski, M.; Home, R.; Kupidura, P. Public perceptions of rural landscapes in land consolidation procedures in Poland. Land Use Policy 2014, 39, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ye, Y. Advances in Land Consolidation and Land Ecology. Land 2024, 13, 1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Long, H.; Deng, W. Land consolidation: A comparative research between Europe and China. Land Use Policy 2022, 112, 105790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, A.; Lisec, A. Land consolidation for large-scale infrastructure projects in Germany. Geod. Vestn. 2014, 58, 46–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Kang, J. Decision Making and Influencing Factors in Withdrawal of Rural Residential Land-Use Rights in Suzhou, Anhui Province, China. Land 2023, 12, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, T.; Luo, B.; Tang, L.; He, Q. Does land tenure security increase the marketization of land rentals between acquaintances? Appl. Econ. Lett. 2022, 29, 790–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. On the Policy Connotation and Legal Realization of the “Separation of Three Rights” in Homestead. Jurist 2021, 35, 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, S.; Mei, W. Legal Implication and Institutional Realization of the Policy of “Separation of Three Rights Relating to Homestead”. Law Sci. 2018, 9, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Han, W.; Xie, L. The Plight of Power and Realization of the Power for the “Three Rights Division” of the Homestead in Countryside. Issues Agric. Econ. 2018, 39, 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; Peng, W.; Huang, X.; Fu, Q.; Zhang, Q. Homestead management in China from the “separation of two rights” to the “separation of three rights”: Visualization and analysis of hot topics and trends by mapping knowledge domains of academic papers in China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI). Land Use Policy 2020, 97, 104670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G. Research on the “Three Rights Separation” System of Rural Homesteads in China. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2023, 5, 170–177. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.; Jiang, J.; Yu, C.; Rodenbiker, J.; Jiang, Y. The endowment effect accompanying villagers’ withdrawal from rural homesteads: Field evidence from Chengdu, China. Land Use Policy 2020, 101, 105107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y. Practice Path and Institutional Norms of Idle Rural Residential Land Redevelopment Led by Rural Collectives. China Land Sci. 2023, 37, 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C. Legal Structure and Gradual Reform Path of the Separation of the Three Rights of Homestead under the Background of Rural Revitalization Strategy. Nanjing J. Soc. Sci. 2025, 35, 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, L.; Liu, H. Effective Utilization of Rural Idle Homestead: Dynamic Basis and Realization Path: Based on the Observation of Y Village in Kunming Rural Revitalization Pilot Zone. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2023, 23, 132–143. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, B. The Property Rights: From Delimitation to Implementation: The Logical Clue of Chinese Farmland Management System Transformation. Issues Agric. Econ. 2019, 1, 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Barzel, Y. What are ‘property rights’, and why do they matter? A comment on Hodgson’s article. J. Inst. Econ. 2015, 11, 719–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Liu, S.; Xu, D. Can the Return of Rural Labor Effectively Stimulate the Demand for Land? Empirical Evidence from Sichuan Province, China. Agriculture 2025, 15, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Luo, H.; Wang, C.; Hu, Y. Study on the Impact of Collective Trusteeship on Rural Residential Land Use Efficiency in the Context of “Tripartite Entitlement” System. China Land Sci. 2024, 38, 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Coase, R.H. The Problem of Social Cost. J. Law Econ. 2013, 56, 837–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. China’s initiatives towards rural land system reform. Land Use Policy 2020, 94, 104567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, J. The “Three Rights Separation” Reform of Homestead and Increase of Farmers’ Income. Reform 2021, 33, 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Yang, H.; Xu, G.; Cheng, C. The Influence of Rural Land Transfer on Rural Households’ Income: A Case Study in Anhui Province, China. Land 2025, 14, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, M.J. The Measurement of Productive Efficiency. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 1957, 120, 253–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.; Hu, B.; Shi, K.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Q. The structural and functional evolution of rural homesteads in mountainous areas: A case study of Sujiaying village in Yunnan province, China. Land Use Policy 2019, 88, 104100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, S.; Wang, D.; Wei, Y. Multifunctional Identification and Transition Path of Rural Homesteads: A Case Study of Jilin Province. Land 2024, 13, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Tong, D.; Long, J.; Shen, Y. County urban-rural integration and homestead system reform:Theoretical logic and implementation path. J. Nat. Resour. 2023, 38, 2135–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Wu, Y.; Chen, L. Does the land titling program promote rural housing land transfer in China? Evidence from household surveys in Hubei Province. Land Use Policy 2020, 97, 104701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, T. Behavioural selection of farmer households for rural homestead use in China: Self-occupation and transfer. Habitat Int. 2024, 152, 103163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Tong, C.; Nian, S.; Yan, J. Realization Mechanism of Farmers’ Rights and Interests Protection in the Paid Withdrawal of Rural Homesteads in China—Empirical Analysis Based on Judicial Verdicts. Land 2024, 13, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xue, K.; Cao, H.; Hu, Y. The Non-Linear Relationship between the Number of Permanent Residents and the Willingness of Rural Residential Land Transfer: The Threshold Effect of per Capita Net Income. Land 2023, 12, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, P.; Tian, Y.; Zou, Y. A novel framework for rural homestead land transfer under collective ownership in China. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Huang, Z.; Fu, Z.; Dai, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, W. Does Land Transfer Enhance the Sustainable Livelihood of Rural Households? Evidence from China. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, G.; Liu, Q.; Guan, B. Why Property Right Intensity Fails to Accelerate the Rural Land Transfer: Mediating Role of the Endowment Effect and Moderating Role of the Land Attachment. J. Lanzhou Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2021, 49, 66–79. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, B.E. Threshold effects in non-dynamic panels: Estimation, testing, and inference. J. Econom. 1999, 93, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B.E. Sample Splitting and Threshold Estimation. Econometrica 2000, 68, 575–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Yang, R.; Wang, L.; Wu, B. Rural Land Transfer and the Change of Agricultural Production Mode in China. J. Manag. World 2024, 40, 76–88. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, C. Impact of land transfer on high-quality agricultural development: Analysis based on the green TFP perspective. J. Nat. Resour. 2024, 39, 1418–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzel, Y. Economics Analysis of Property Rights; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Alchian, A. Some Economics of Property Rights. II Politico 1965, 30, 816–829. [Google Scholar]

- Demsetz, H. Toward a Theory of property Right II: The competition between Private and Collective Ownership. J. Legal Stud. 2002, 31, S653–S752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, S.T.; Deininger, K.; Ghebru, H. Tenure Insecurity, Gender, Low-cost Land Certification and Land Rental Market Participation in Ethiopia. J. Dev. Stud. 2011, 47, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.; Fletschner, D.; Savath, V.; Peterman, A. Can Government-Allocated Land Contribute to Food Security? Intrahousehold Analysis of West Bengal’s Microplot Allocation Program. World Dev. 2014, 64, 860–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singirankabo, U.A.; Ertsen, M.W. Relations between Land Tenure Security and Agricultural Productivity: Exploring the Effect of Land Registration. Land 2020, 9, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.; Luo, B.; Hu, X. Land titling, land reallocation experience, and investment incentives: Evidence from rural China. Land Use Policy 2020, 90, 104271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orongo, N.D.; Mátyás, G. Performance Evaluation of Land Administration System (LAS) of Nairobi Metropolitan Area, Kenya. Land 2022, 11, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deininger, K. Land Policies for Growth and Poverty Reduction; A World Bank Policy Research Report; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddulph, R.; Hillbom, E. Registration of private interests in land in a community lands policy setting: An exploratory study in Meru district, Tanzania. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A. Increasing returns and economic progress. Econ. J. 1928, 38, 527–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, S.; Luo, X.; Liu, X. How to Build a Rural Community to Develop High-Quality Rural Tourism: A Case Study of Innovative Development Strategies for Idle Rural Homesteads in China. Land 2024, 13, 2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Abdulai, A. Does cooperative membership improve household welfare? Evidence from apple farmers in China. Food Policy 2016, 58, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.L.; Dwivedi, P.; Kumar, A. Evaluating the Impact and Challenges of Farmer Producer Organizations on Agricultural Development in Jaipur District, Rajasthan, India. Asian Res. J. Agric. 2024, 17, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).