An HUL Assessment for Small Cultural Heritage Sites in Urban Areas: Framework, Methodology, and Empirical Research

Abstract

1. Introduction

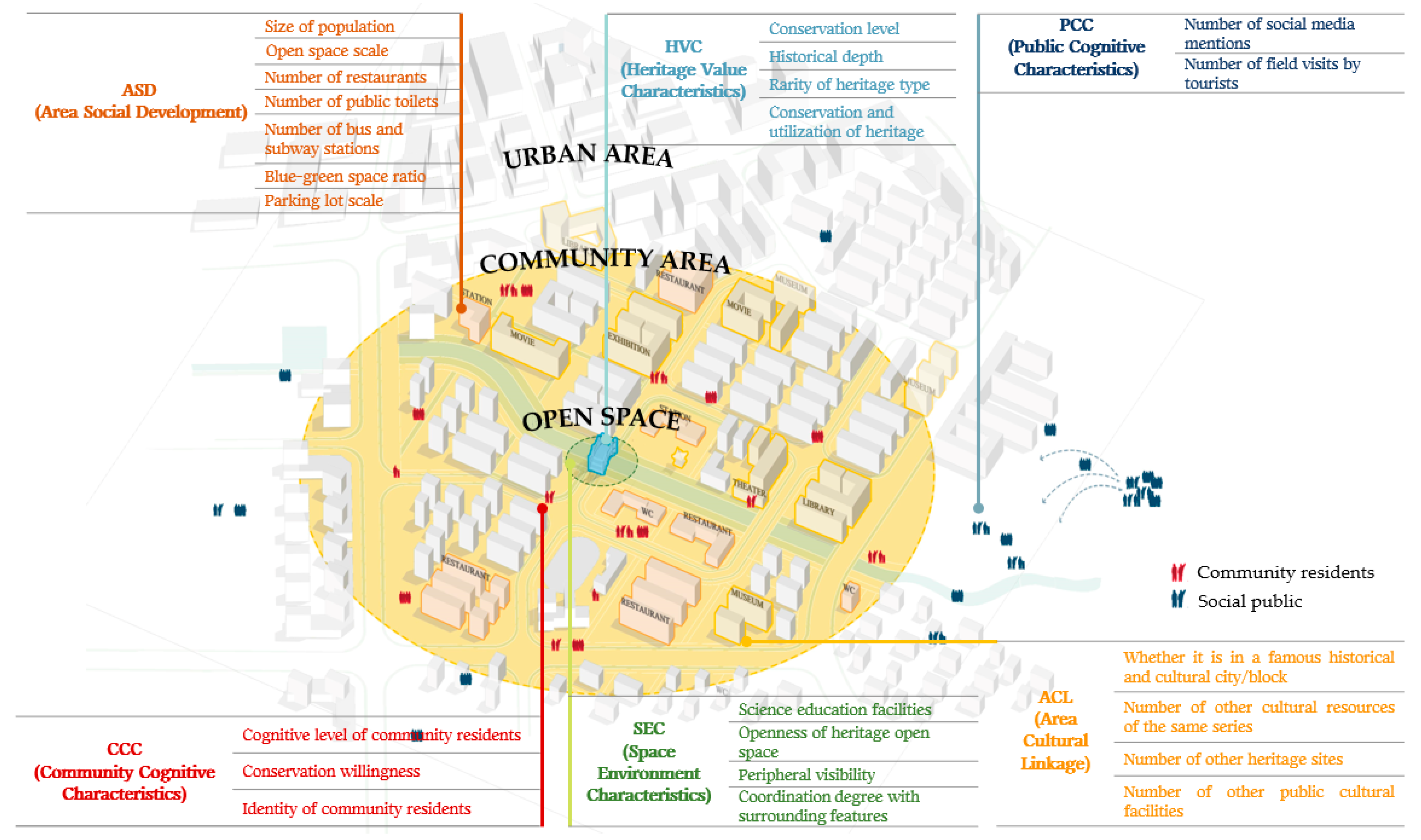

2. Assessment Framework and the Path of Application

2.1. Assessment Framework: Six Dimensions and 24 Indicators

2.2. The Path of Application Method

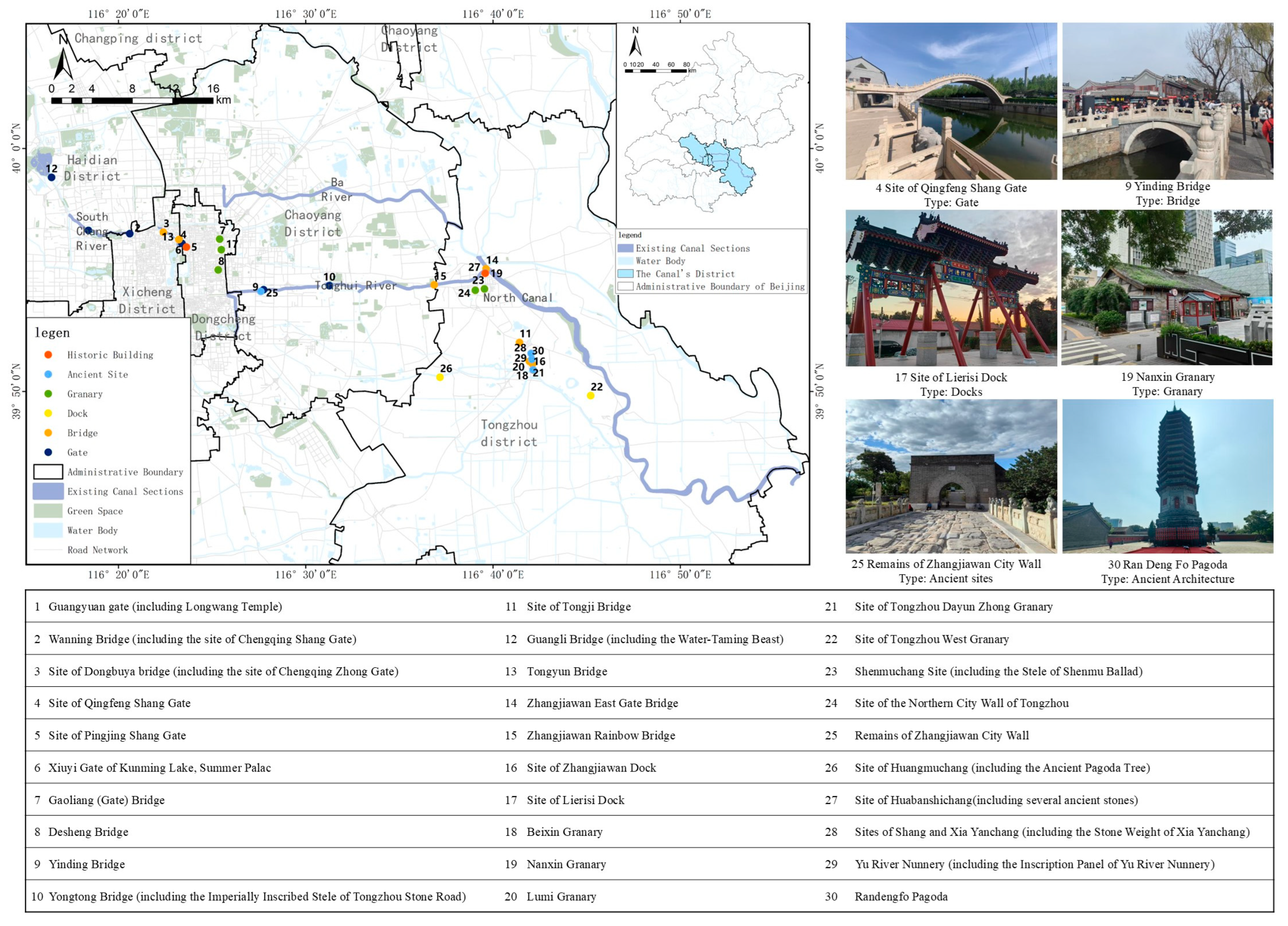

3. Empirical Research on 30 SCHS in the Beijing Section of the Grand Canal

3.1. Research Object

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis Steps

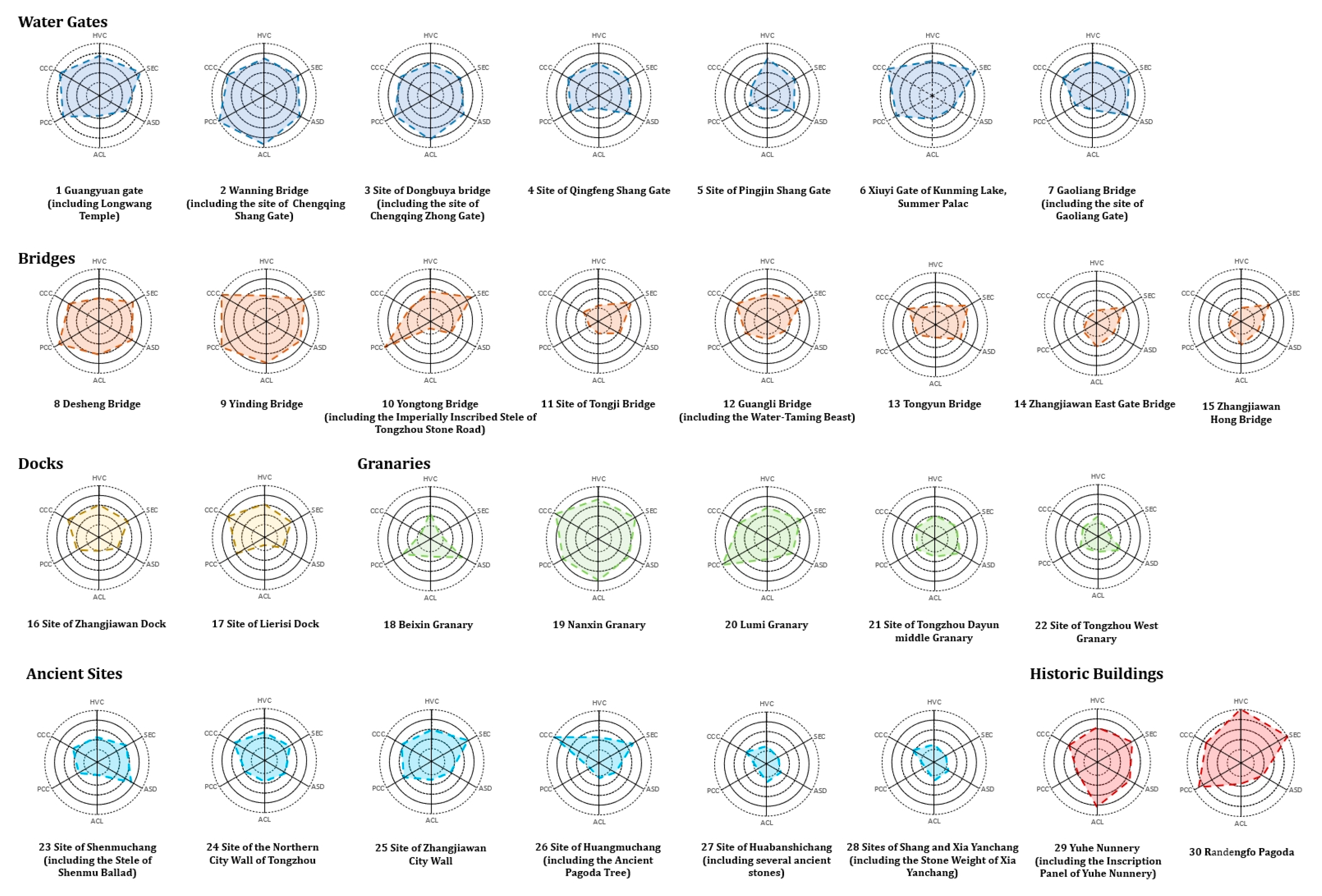

3.3. Result

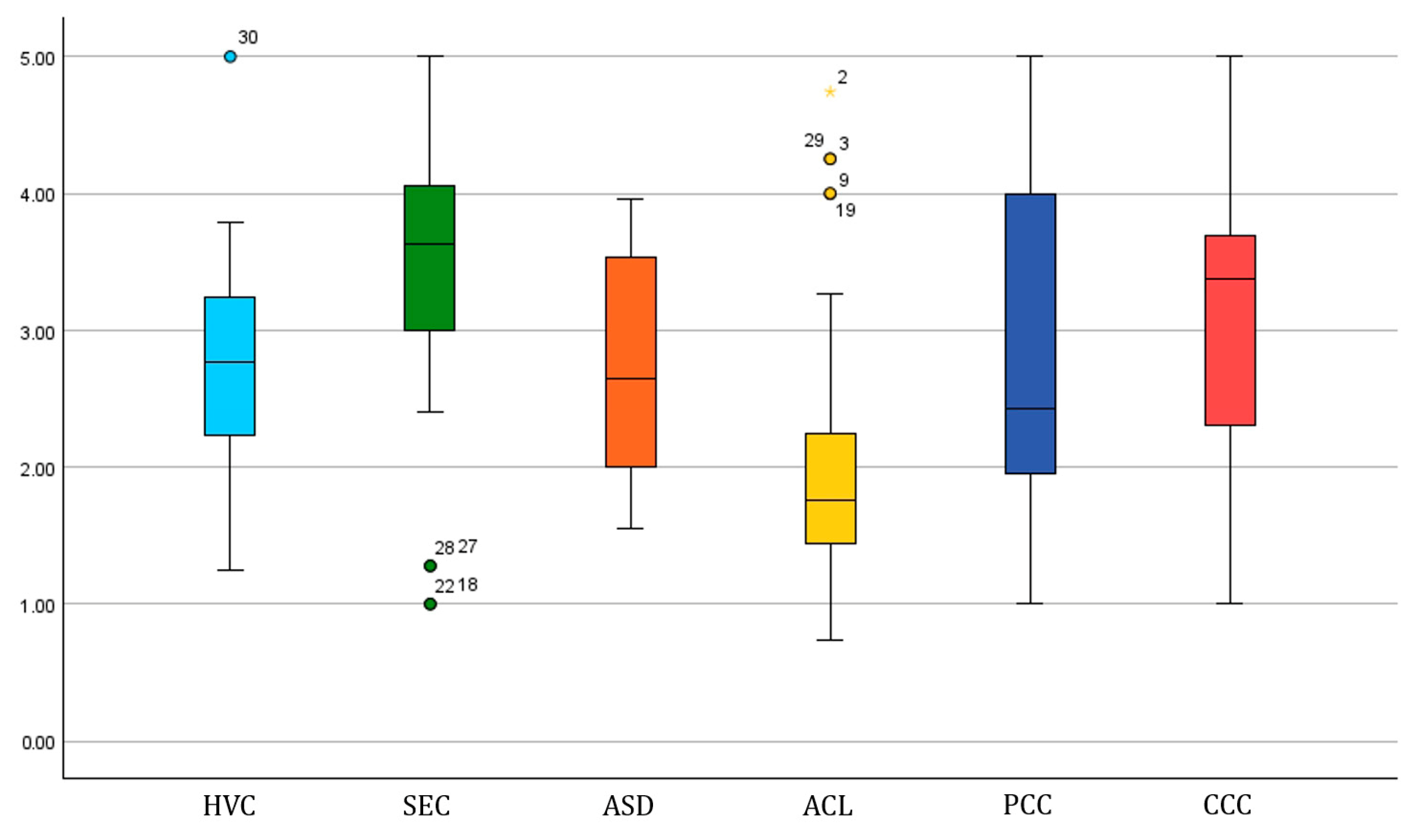

3.3.1. Univariate Analysis at the Dimensional Level

3.3.2. Correlation Analysis

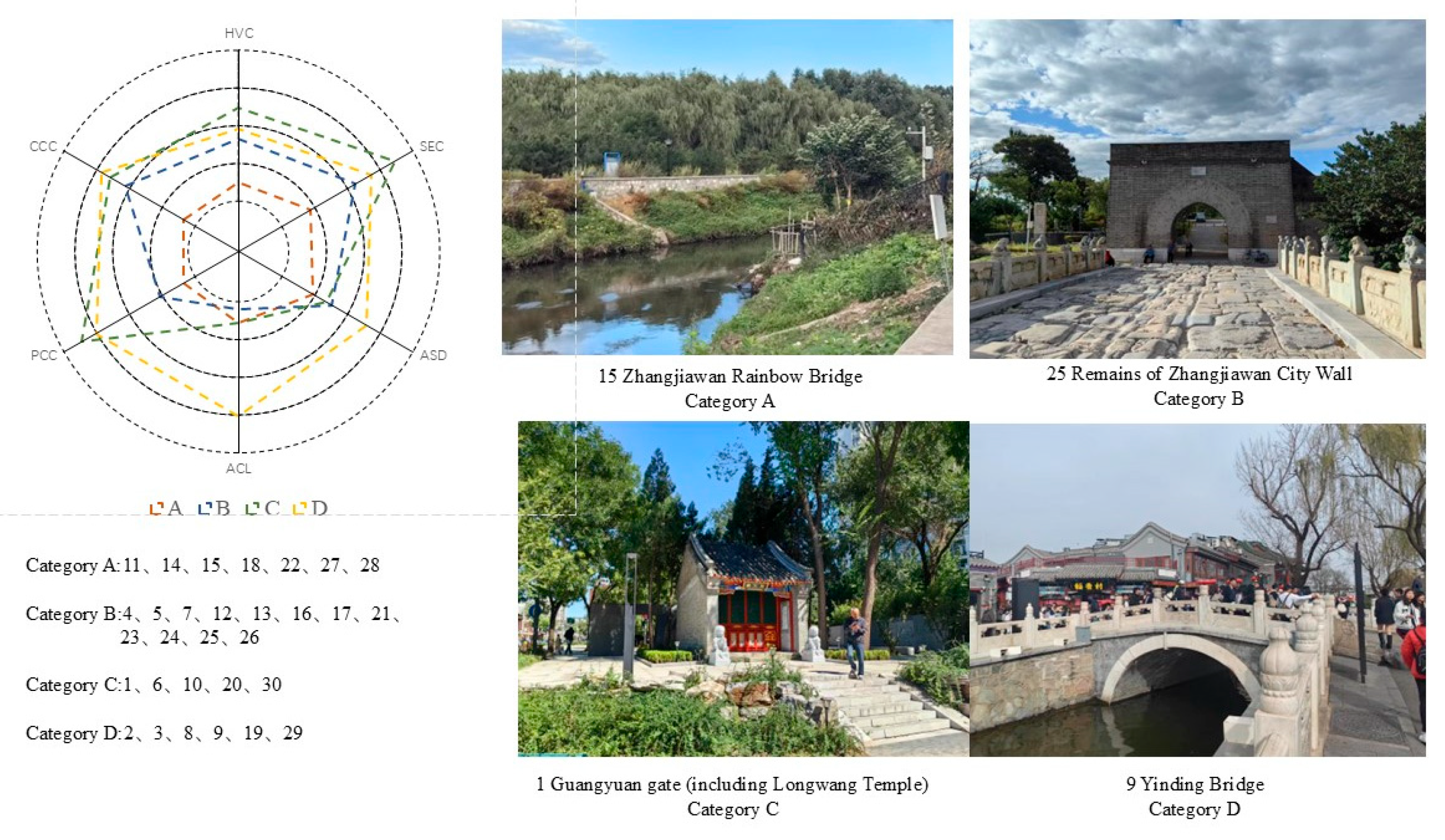

3.3.3. Cluster Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. The Advantages and Application Potential of the HUL Assessment for SCHSs

4.2. Comparative Analysis and Implications Based on Empirical Research

4.3. Limitation

- (1)

- The environments, cultural backgrounds, and stages of social and economic development in different cities are all different, and there are also significant differences in the goals of diverse assessments. Therefore, as an action-oriented proactive assessment method, the selection of indicators in this study has limitations for different research objects and environments in the future. The value of the six dimensions constructed in this study is much greater than the selected indicators. As a framework from the HUL perspective, it requires a flexible selection of indicators to adapt to the needs of the assessment. For instance, the refinement of personnel characteristics such as age, educational level, and ethnicity should be carried out [66,67]. In terms of the sources of viewpoints, relevant government organizations and profit-making institutions should be included [68]. In the viewpoints themselves, more diverse types including negative attitudes should also be incorporated. A broader environment often means the emergence of more inconsistent voices; these voices should be regarded as important references for continuously optimizing policies and actions for the conservation and utilization of heritage, and will also be conducive to enriching a diverse contemporary understanding of the urban historical landscape in areas with high heritage potential.

- (2)

- (3)

- The weights of the dimensions and the acquisition of some information in the assessments are determined through manual judgment. This may lead to inconsistent results due to differences in viewpoints among different assessors. In the future, digital instruments and artificial intelligence technologies can be combined to achieve a transformation from subjective evaluation to scientific quantification. However, at the same time, the long-term requirements of the assessment should also be considered, and a balance should be achieved between scientificity and efficiency. Since there are only 30 SCHSs in the Beijing section of the Grand Canal, the sample size has certain limitations. In the future, research can be conducted on a larger number of SCHSs in specific areas, which will help improve the accuracy of the impact mechanism research and also promote the exploration of more diverse application methods of this assessment framework.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HUL | Historic Urban Landscape |

| HIA | Heritage Impact Assessment |

| SCHSs | Small Cultural Heritage Sites |

| HVCs | Heritage Value Characteristics |

| SECs | Space Environment Characteristics |

| ASD | Area Social Development |

| ACL | Area Cultural Linkage |

| PCCs | Public Cognitive Characteristics |

| CCCs | Community Cognitive Characteristics |

References

- Tweed, C.; Sutherland, M. Built Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Urban Development. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 83, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape. In Proceedings of the Records of the General Conference 36th Session, Paris, France, 25 October–10 November 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sesana, E.; Gagnon, A.S.; Bonazza, A.; Hughes, J.J. An Integrated Approach for Assessing the Vulnerability of World Heritage Sites to Climate Change Impacts. J. Cult. Herit. 2020, 41, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Lu, Y.; Gao, H.; Wang, M. Cultivating Historical Heritage Area Vitality Using Urban Morphology Approach Based on Big Data and Machine Learning. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2022, 91, 101716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, B.; Kloos, M.; Neugebauer, C. Heritage Impact Assessment, beyond an Assessment Tool: A Comparative Analysis of Urban Development Impact on Visual Integrity in Four UNESCO World Heritage Properties. J. Cult. Herit. 2021, 47, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agapiou, A.; Alexakis, D.D.; Lysandrou, V.; Sarris, A.; Cuca, B.; Themistocleous, K.; Hadjimitsis, D.G. Impact of Urban Sprawl to Cultural Heritage Monuments: The Case Study of Paphos Area in Cyprus. J. Cult. Herit. 2015, 16, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornelas, C.; Sousa, F.; Guedes, J.M.; Breda-Vázquez, I. Monitoring and Assessment Heritage Tool: Quantify and Classify Urban Heritage Buildings. Cities 2023, 137, 104274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Tian, D. Public Participation in the Conservation and Management of Canal Cultural Heritage Worldwide: A Case Study of the Rideau Canal and Erie Canal. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veillon, R. State of Conservation of World Heritage Properties—A Statistical Analysis (1979–2013); UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira Roders, A.; Van Oers, R. Guidance on Heritage Impact Assessments: Learning from Its Application on World Heritage Site Management. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 2, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiwael, P.R.; Groote, P.; Vanclay, F. Improving Heritage Impact Assessment: An Analytical Critique of the ICOMOS Guidelines. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2019, 25, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyedashrafi, B.; Ravankhah, M.; Weidner, S.; Schmidt, M. Applying Heritage Impact Assessment to Urban Development: World Heritage Property of Masjed-e Jame of Isfahan in Iran. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 31, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginzarly, M.; Teller, J. Eliciting Cultural Heritage Values: Landscape Preferences vs Representative Images of the City. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 8, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Tang, Y.; Pan, J.; Li, Q. Assessment of Urbanization Impact on Cultural Heritage Based on a Risk-Based Cumulative Impact Assessment Method. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodwell, D.; Turner, M. Impact Assessments for Urban World Heritage: European Experiences under Scrutiny. Built Herit. 2018, 2, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, E.H.; Chan, E.H. Problem Issues of Public Participation in Built-Heritage Conservation: Two Controversial Cases in Hong Kong. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ikebe, K.; Kinoshita, T.; Chen, J.; Su, D.; Xie, J. How Heritage Promotes Social Cohesion: An Urban Survey from Nara City, Japan. Cities 2024, 149, 104985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, A.; Smyth, K. Heritage, Health and Place: The Legacies of Local Community-Based Heritage Conservation on Social Wellbeing. Health Place 2016, 39, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzmán, P.C.; Roders, A.P.; Colenbrander, B.J.F. Measuring Links between Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Urban Development: An Overview of Global Monitoring Tools. Cities 2017, 60, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riganti, P.; Nijkamp, P. Valuing Cultural Heritage Benefits to Urban and Regional Development. In Proceedings of the 44th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: “Regions and Fiscal Federalism”, Porto, Portugal, 25–29 August 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Grimwade, G.; Carter, B. Managing Small Heritage Sites with Interpretation and Community Involvement. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2000, 6, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, G.; Al-Tikriti, W.Y.; Mahdy, H.; Al Nuaimi, A.; Al Kaabi, A.; Altawallbeh, D.E.; Ali Muhammad, S.; Marcus, B. Protecting the Invisible: Site-Management Planning at Small Archaeological Sites in al-Ain, Abu Dhabi. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2014, 16, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodadadi, M.; Pezeshki, F.; O’Donnell, H. Small but Perfectly (in) Formed? Sustainable Development of Small Heritage Sites in Iran. J. Herit. Tour. 2022, 17, 74–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palka, J.W. A Small Rural Travel Stopover at the Late Postclassic Maya Site of Mensabak, Chiapas, Mexico: Overland Trade, Cross-Cultural Interaction and Social Cohesion in the Countryside. Camb. Archaeol. J. 2024, 34, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erny, G. Statistical Approaches to Small Site Diversity: New Insights from Cretan Legacy Survey Data. J. Mediterr. Archaeol. 2023, 36, 71–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, S. Protecting China’s Cultural Heritage Sites in Times of Rapid Change: Current Developments, Practice and Law. Asia Pac. J. Environ. Law 2007, 10, 253. [Google Scholar]

- Tantinipankul, W. Thailand’s Neglected Urban Heritage: Challenges for Preserving the Cultural Landscape of Provincial Towns of Thailand. Int. J. Tour. Anthropol. 2013, 3, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.A.; Abouelfadl, H. Stitching the Gap between Contemporary Archaeology and the City through “URBAN DOTS”: Case Study of Kōm al-Nāḍūra Area, Alexandria, Egypt. Alex. Eng. J. 2022, 61, 12891–12914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Q. A Chinese Approach to Urban Heritage Conservation and Inheritance: Focus on the Contemporary Changes of Shanghai’s Historic Spaces. Built Herit. 2017, 1, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, X.; Weng, F.; Ding, F.; Wu, Y.; Yi, Z. Evolution of Cultural Landscape Heritage Layers and Value Assessment in Urban Countryside Historic Districts: The Case of Jiufeng Sheshan, Shanghai, China. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. The Development and Institutional Characteristics of China’s Built Heritage Conservation Legislation. Built Herit. 2022, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q. A Model Approach for Post Evaluation of Adaptive Reuse of Architectural Heritage: A Case Study of Beijing Central Axis Historical Buildings. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Han, Y. Vitality Evaluation of Historical and Cultural Districts Based on the Values Dimension: Districts in Beijing City, China. Herit. Sci. 2022, 10, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Roders, A.P.; Van Wesemael, P. Informing or Consulting? Exploring Community Participation within Urban Heritage Management in China. Habitat Int. 2020, 105, 102268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jin, C.; Wang, T.; Xu, D. The Interpretation of Historical Layer Evolution Laws in Historic Districts from the Perspective of the Historic Urban Landscape: A Case Study in Shenyang, China. Land 2025, 14, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Li, W. Study on Historic Urban Landscape Corridor Identification and an Evaluation of Their Centrality: The Case of the Dunhuang Oasis Area in China. Land 2025, 14, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Dai, F.; Chen, X. Mediating Roles of Cultural Perception and Place Attachment in the Landscape–Wellbeing Relationship: Insights from Historical Urban Parks in Wuhan, China. Land 2025, 14, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tang, J.; Dai, D. Using Public Participation Geographic Information System to Study Social Cohesion and Its Relationship with Activities and Specific Landscape Characteristics in Shanghai’s Modern Historic Parks. Land 2024, 13, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reher, G.S. What Is Value? Impact Assessment of Cultural Heritage. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 10, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.L.; Cabrera, A.T.; del Pulgar, M.L.G. The Potential Role of Cultural Ecosystem Services in Heritage Research through a Set of Indicators. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 117, 106670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichumbaki, E.B.; Mjema, E. The Impact of Small-Scale Development Projects on Archaeological Heritage in Africa: The Tanzanian Experience. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2018, 20, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, L.; Huang, W.; Shen, M.; Yi, X.; Zhang, J.; Lu, S. Extending X-Reality Technologies to Digital Twin in Cultural Heritage Risk Management: A Comparative Evaluation from the Perspective of Situation Awareness. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aigwi, I.E.; Filippova, O.; Sullivan-Taylor, B. Public Perception of Heritage Buildings in the City-Centre of Invercargill, New Zealand. City Cult. Soc. 2023, 34, 100538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idilfitri, S.; Rodzi, N.I.M.; Mohamad, N.H.N.; Sulaiman, S. Public Perception of the Cultural Perspective towards Sustainable Development. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 168, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Xu, Y.; Rollo, J.; Esteban, Y.; Tong, H.; Yin, X. Developing a Comprehensive Assessment Model of Social Value with Respect to Heritage Value for Sustainable Heritage Management. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras, V.C.; Moscoso Cordero, M.S.; Wijffels, A.; Tenze, A.; Jaramillo Paredes, D.E. Heritage Values: Towards a Holistic and Participatory Management Approach. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 9, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petti, L.; Trillo, C.; Makore, B.C.N. Towards a Shared Understanding of the Concept of Heritage in the European Context. Heritage 2019, 2, 2531–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.S.; Macedo, D.V.; Brito, A.Y.S.; Furtado, V. Assessment of Urban Cultural-Heritage Protection Zones Using a Co-Visibility-Analysis Tool. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2019, 76, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Wang, N.; Li, Y.; Sun, D.J. 15-Min Pedestrian Distance Life Circle and Sustainable Community Governance in Chinese Metropolitan Cities: A Diagnosis. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Divigalpitiya, P. Availability and Adequacy of Facilities in 15 Minute Community Life Circle Located in Old and New Communities. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 2176–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissfazekas, K. Circle of Paradigms? Or ‘15-Minute’Neighbourhoods from the 1950s. Cities 2022, 123, 103587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zancheti, S.M.; Hidaka, L.T.F. Measuring Urban Heritage Conservation: Indicator, Weights and Instruments (Part 2). J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 2, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. The Hot Spots and Frontiers of Research on the Grand Canal Culture Belt in China: Literature and Academic Trends. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, A.P. Built Heritage and Development: Heritage Impact Assessment of Change in Asia. Built Herit. 2017, 1, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, N. Towards a Culturally Sustainable Environmental Impact Assessment: The Protection of Ainu Cultural Heritage in the Saru River Cultural Impact Assessment, Japan. Geogr. Res. 2013, 51, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafiah, M.H.; Jamaluddin, M.R.; Riyadi, A. Local Community Support, Attitude and Perceived Benefits in the UNESCO World Heritage Site. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 11, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apaydin, V. Value, Meaning and Understanding of Heritage: Perception and Interpretation of Local Communities in Turkey. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference of Best Practices in World Heritage: People and Communities, Mahon, Minorca, Spain, 29 April–2 May 2015; pp. 204–211. [Google Scholar]

- Jimura, T. The Impact of World Heritage Site Designation on Local Communities–A Case Study of Ogimachi, Shirakawa-Mura, Japan. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L. The Two Opposing Impacts of Heritage Making on Local Communities: Residents’ Perceptions: A Portuguese Case. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2014, 20, 616–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apaydin, V. Heritage Values and Communities: Examining Heritage Perceptions and Public Engagements. J. East. Mediterr. Archaeol. Herit. Stud. 2017, 5, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazazzadeh, H.; Nadonly, A.; Attarian, K.; Najar, B.S.A.; Safaei, S.S.H. Promoting Sustainable Development of Cultural Assets by Improving Users’ Perception through Space Configuration; Case Study: The Industrial Heritage Site. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, J. Community Perception of Heritage Values Regarding a Global Monument in Ghana: Implications for Sustainable Heritage Management. J. Humanit. Appl. Soc. Sci. 2022, 4, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Nik Hashim, N.H.; Goh, H.C. Public Perception of Cultural Ecosystem Services in Historic Districts Based on Biterm Topic Model. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gargiulo, C.; Sgambati, S.; Zucaro, F. The Analysis of the Urban Open Spaces System for Resilient and Pleasant Historical Districts. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications 2023, Athens, Greece, 3–6 July 2023; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 564–577. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, L.; Xue, M.; Li, J.; Ma, J. Historic District Conservation: A Critical Review of Global Trends, Development in the 21st Century, and Challenges Through CiteSpace Analysis. Buildings 2025, 15, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zukin, S.; Living, L. The Cultures of Cities, 1995; Blackwell Publishers Ltd.: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Pokotylo, D.; Guppy, N. Public Opinion and Archaeological Heritage: Views from Outside the Profession. Am. Antiq. 1999, 64, 400–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y. Cultural Entrepreneurs and Urban Regeneration in Itaewon, Seoul. Cities 2016, 56, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Noronha Vaz, E.; Cabral, P.; Caetano, M.; Nijkamp, P.; Painho, M. Urban Heritage Endangerment at the Interface of Future Cities and Past Heritage: A Spatial Vulnerability Assessment. Habitat Int. 2012, 36, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, L.; György, E.; Oláh, G.; Teixeira Lopes, J.; Sonkoly, G.; Apolinário, S.; Azevedo, N.; Ricardo, J. Gentrification and Touristification in Urban Heritage Preservation: Threats and Opportunities. Cult. Trends 2024, 33, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Indicator | Type | Connotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| HVCs | Conservation level | A | The level of conservation (determined according to official documents, e.g., national, provincial, municipal, district, and unranked) reflects the historical value from an official perspective. |

| Historical depth | A | The historical depth of a SCHS is expressed through the dynastic representation of its origins, contextualized within regional/national historical narratives. | |

| Rarity of heritage type | A | Uniqueness quantified by the inverse proportion of similar heritage types within the research area (e.g., 10% of total sites = rare), indicating historical distinctiveness. | |

| Conservation and utilization of heritage | B | Dual assessment: (1) Physical preservation quality (e.g., material decay rate) and (2) Functional adaptation (e.g., adaptive reuse as cultural venues), focusing on whether heritage has been integrated into new social, economic, or cultural functions, reflecting conservation, transmission, and utilization. | |

| SECs | Science education facilities | B | Assessing the capacity and effectiveness of heritage in popularizing heritage-related scientific knowledge and disseminating history and culture, as reflected by the type, size, and number of science education facilities around the site. |

| Openness of the heritage open space | B | Assessing the extent to which open spaces where heritage is located are accessible to the public and how easily they can be accessed. | |

| Peripheral visibility | B | Focus on visibility and the visibility of heritage in its open space, reflecting environmental visibility, assessed by the direction of openness, distance of visibility, and level of attraction. | |

| Harmony with surrounding features | B | Evaluate the coherence of the heritage with its open space in terms of landscape (both man–made elements such as buildings and natural elements such as plants and waters), reflecting environmental coherence. | |

| ASD | Size of population | C | Statistics on the total number of people in the community area, reflecting the permanent population of the community. |

| Open space scale | C | Statistics on the total area of open space (including squares, green spaces, and parks) within the community area, reflecting the public environmental quality. | |

| Number of restaurants | C | Statistics on the number of food and beverage outlets in the community area reflect the public service capacity. | |

| Number of public toilets | C | Statistics on the number of public toilets in the community area reflect the public service capacity. | |

| Number of bus and subway stations | C | Statistics on the total number of bus and metro stations in the community area, reflecting public transport accessibility. | |

| Blue-green space scale | C | Statistics on the total area of blue (water) and green spaces within the community area, reflecting the ecological environmental quality. | |

| Parking lot scale | C | Statistics on the total area of car parks in the community area, reflecting private transport accessibility. | |

| ACL | Whether it is in a famous historical and cultural city/block | C | Investigate whether the community area has been included in the official overall conservation zone, reflecting the overall conservation situation of the area. |

| Number of other heritage sites of the same series | C | Statistics on the number of other cultural heritages belonging to the same heritage series within the community area to reflect the degree of aggregation of a specific historical culture. | |

| Number of other heritage sites | C | Statistics on the number of other municipal or higher-level heritage sites within the community area to reflect the overall concentration of historical and cultural resources. | |

| Number of other public cultural facilities | C | Statistics on the number of public cultural facilities (including museums, exhibition halls, cultural squares, cinemas, theatres, and libraries) in the community area, reflecting the potential for connection with contemporary cultural resources. | |

| PCCs | Number of social media mentions | D | Statistics on the number of keyword mentions of each SCHS on social media platforms, reflecting the level of social concern. |

| Number of field visits by tourists | D | Statistics on the number of historical comments on each SCHS from tourism platforms, reflecting the on-site visits of the public. | |

| CCCs | Familiarity degree of community residents | E | Conducting field research in the communities to examine the degree of familiarity of the community residents with the SCHSs. |

| Conservation willingness of community residents | E | Conducting field research in the communities to examine the conservation willingness of the community residents of the SCHSs. | |

| Identity of community residents | E | Conducting field research in the communities to examine the degree of recommendation of the community residents of the SCHSs. |

| Heritage Type | HVCs | SECs | ASD | ACL | PCCs | CCCs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water Gate | 3.37 | 3.81 | 3.31 | 2.47 | 3.43 | 3.61 |

| Bridge | 1.98 | 3.72 | 2.53 | 2.08 | 2.85 | 2.59 |

| Dock | 3.18 | 3.07 | 1.99 | 0.99 | 2.74 | 3.75 |

| Granary | 2.71 | 2.42 | 3 | 2.16 | 3.17 | 2.51 |

| Ancient Site | 2.61 | 2.74 | 2.22 | 1.66 | 1.69 | 3.18 |

| Historic Building | 4.12 | 4.4 | 2.96 | 3.11 | 3.29 | 3.38 |

| Conservation Level | HVCs | SECs | ASD | ACL | PCCs | CCCs |

| National Conservation | 3.12 | 3.57 | 2.66 | 2.24 | 3.46 | 3.16 |

| Municipal Heritage Conservation | 2.84 | 3.08 | 2.95 | 2.4 | 3.12 | 2.63 |

| District Heritage Conservation | 2.53 | 3.58 | 2.87 | 2.23 | 2.92 | 3.74 |

| Unrated | 2.02 | 2.53 | 2.14 | 1.54 | 1.71 | 2.24 |

| District | HVCs | SECs | ASD | ACL | PCCs | CCCs |

| Haidian | 3.46 | 4.44 | 2.99 | 1.89 | 3.32 | 4.25 |

| Xicheng | 2.75 | 3.89 | 3.81 | 4 | 4.82 | 4.12 |

| Dongcheng | 3.13 | 3.17 | 3.39 | 3.22 | 3.6 | 3.06 |

| Chaoyang | 3.02 | 3.15 | 3.45 | 1.3 | 2.37 | 2.58 |

| Tongzhou | 2.56 | 3.3 | 2.26 | 1.69 | 2.35 | 2.91 |

| HVC | SEC | ASD | ACL | PCC | CCC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HVC | 1 | |||||

| SEC | 0.532 ** | 1 | ||||

| ASD | 0.355 | 0.196 | 1 | |||

| ACL | 0.203 | 0.220 | 0.506 ** | 1 | ||

| PCC | 0.591 ** | 0.537 ** | 0.468 ** | 0.422 * | 1 | |

| CCC | 0.579 ** | 0.603 ** | 0.226 | 0.335 | 0.489 ** | 1 |

| Number of Social Media Mentions | Nu IUmber of Field Visits by Tourists | Familiarity Degree of Community Residents | Conservation Willingness of Community Residents | Identity of Community Residents | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservation level | 0.480 ** | 0.504 ** | 0.257 | 0.527 ** | 0.366 * |

| Historical depth | 0.118 | 0.182 | 0.025 | 0.182 | 0.271 |

| Rarity of heritage type | −0.152 | 0.043 | −0.057 | 0.084 | 0.222 |

| Conservation and utilization of heritage | 0.423 * | 0.567 ** | 0.595 ** | 0.721 ** | 0.655 ** |

| Science education facilities | 0.465 ** | 0.511 ** | 0.482 ** | 0.597 ** | 0.564 ** |

| The openness of the heritage open space | 0.351 | 0.281 | 0.325 | 0.512** | 0.288 |

| Peripheral visibility | 0.405 * | 0.449 * | 0.452 * | 0.562 ** | 0.461 * |

| Harmony with surrounding features | 0.287 | 0.310 | 0.290 | 0.414 * | 0.368 * |

| Size of population | 0.335 | 0.499 ** | 0.110 | 0.289 | 0.262 |

| Open space scale | 0.226 | 0.406 * | 0.225 | 0.394 * | 0.405 * |

| Number of restaurants | 0.110 | 0.226 | −0.188 | −0.065 | −0.035 |

| Number of public toilets | 0.378 * | 0.290 | 0.023 | 0.080 | 0.153 |

| Number of bus and subway stations | 0.083 | −0.051 | −0.200 | −0.184 | −0.171 |

| Blue-green space ratio | 0.176 | 0.400 * | 0.298 | 0.433 * | 0.372 * |

| Parking lot scale | 0.232 | 0.307 | 0.313 | 0.144 | 0.110 |

| Whether it is in a famous historical and cultural city/block | 0.456 * | 0.413 * | 0.366 * | 0.484 ** | 0.471 ** |

| Number of other heritage sites of the same series | −0.312 | −0.298 | 0.004 | −0.051 | −0.115 |

| Number of other heritage sites | 0.383 * | 0.336 | −0.117 | 0.180 | 0.139 |

| Number of other public cultural facilities | 0.429 * | 0.341 | 0.064 | 0.274 | 0.250 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, S.; Sun, H.; Jiang, M.; Zhao, J. An HUL Assessment for Small Cultural Heritage Sites in Urban Areas: Framework, Methodology, and Empirical Research. Land 2025, 14, 1513. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081513

Zhang S, Sun H, Jiang M, Zhao J. An HUL Assessment for Small Cultural Heritage Sites in Urban Areas: Framework, Methodology, and Empirical Research. Land. 2025; 14(8):1513. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081513

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Shiyang, Haochen Sun, Muye Jiang, and Jingrui Zhao. 2025. "An HUL Assessment for Small Cultural Heritage Sites in Urban Areas: Framework, Methodology, and Empirical Research" Land 14, no. 8: 1513. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081513

APA StyleZhang, S., Sun, H., Jiang, M., & Zhao, J. (2025). An HUL Assessment for Small Cultural Heritage Sites in Urban Areas: Framework, Methodology, and Empirical Research. Land, 14(8), 1513. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081513