Abstract

This study examines rural walking tourism as a sustainable strategy for revitalizing regional economies and preserving natural environments, focusing on the DMZ Punch Bowl in South Korea. Although rural walking tourism has been widely promoted for sustainability, little is known about its operation in geopolitically sensitive and militarized ecological zones, such as the Korean DMZ. Adopting the qualitative case study method, we explored three essential conditions for sustainable rural walking tourism: environmental friendliness, experiential immersion and sense of place, and local economic revitalization through stakeholder cooperation. We employed a hybrid thematic analysis using inductive and deductive coding to analyze the triangulated data collected from interviews, field observations, and policy documents. In-depth interviews with ten walking tourism experts revealed that storytelling that emphasizes local history, ecological conservation, and unique cultural identity enhances tourists’ emotional attachment and sense of place immersion. The DMZ Punch Bowl case was selected due to its effective integration of these elements, achieved through a collaborative governance structure involving government agencies, military units, and local communities. The findings highlight that coordinated management and stakeholder cooperation are crucial for balancing land use policies, ecological preservation, and tourism safety. Additionally, walking tourism significantly contributes to local economic growth through direct spending, job creation, increased resident incomes, the sale of local specialties, and participation in experiential activities. This study provides valuable insights and a replicable model for sustainably developing walking tourism in similarly sensitive or ecologically significant rural areas.

1. Introduction

Sustainable tourism, as defined by the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) [1], rests on three pillars: (1) efficient utilization of environmental resources and conservation of ecosystems, biodiversity, and natural heritage; (2) respect for sociocultural identities, including the preservation of local heritage and the promotion of intercultural understanding; and (3) the equitable distribution of socio-economic benefits fostering stable employment, income opportunities, and poverty alleviation. Walking tourism emerges as a strategic pathway to achieve these goals [2,3], blending a minimal environmental footprint with meaningful cultural immersion. However, empirical research remains limited in exploring how walking tourism can be systematically integrated into sustainable development frameworks beyond its environmental benefits, particularly in enhancing local community resilience.

Numerous developed nations, such as the UK, the US, New Zealand, Australia, and Germany, have long invested in walking tourism infrastructure, with examples including the National Trail in the UK and US, the Walkway in New Zealand, the Walking Track in Australia, and the Wandering Route in Germany [4]. These investments have positioned walking tourism as a core element of national tourism strategies. In rural contexts, walking tourism preserves natural landscapes and offers visitors immersive experiences with historical, ecological, and cultural resources, transforming the journey into an attraction. Walking tourism fosters a more sustainable travel approach by enabling direct engagement with nature and heritage while mitigating the environmental footprint of motorized transport. It revitalizes local economies by promoting sustainable consumption patterns and providing more authentic tourist experiences [5].

To contextualize walking tourism within sustainability debates, we draw on slow travel, a philosophy rooted in pre-industrial journeys, such as pilgrimages and grand tours [6,7]. Slow travel challenges industrialized mobility, advocating instead for leisure, sensory immersion, and ethical engagement [8]. Its three core principles, low-carbon transport, journey-centric meaning-making, and destination immersion, position walking tourism as a catalyst for sustainable consumption [2,9]. By traversing landscapes on foot or by bicycle, travelers become attuned to subtle environmental changes—the warmth of sunlight and the scent of forests, fostering emotional connections with places and encouraging responsible environmental behavior [10,11].

Walking tours have also been found to provide people with an escape from stress, fostering mental recovery and emotional detachment during the walking process. This recuperative effect enhances tourism satisfaction, with higher stress levels often correlating with greater satisfaction with walking tours [12]. Long-distance walking has been shown to significantly impact mental health and well-being [13]. Despite these benefits, research on the specific conditions required to revitalize walking tourism in alignment with local community development from a sustainable tourism perspective remains scarce.

Therefore, this study aims to explore the conditions for revitalizing rural walking tourism from a sustainable tourism perspective. To achieve this, we conducted in-depth interviews with walking tourism experts, and qualitative analysis was employed to examine the characteristics and prerequisites for promoting this activity. Based on these interviews, successful walking tourism cases were selected and analyzed to understand “how” and “why” these conditions operate.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2, Theoretical Framework, reviews the relevant literature and conceptual foundations. Section 3, Materials and Methods, describes the study design, data collection, and analytical procedures. Section 4, Section 5 and Section 6 present the empirical findings from Study 1 and Study 2. Finally, Section 7, Discussion, synthesizes the main findings, discusses theoretical and practical implications, and offers directions for future research.

2. Theoretical Analysis Framework

2.1. Rural Walking Tourism and Sustainable Development

Globally, the development of regional tourist destinations has been actively promoted to support local populations and stimulate economic growth through balanced development and the revitalization of local economies [14]. In rural areas, these efforts focus on increasing farmers’ incomes and generating employment by leveraging tourism-related activities, including selling local specialties, accommodations, food, and beverages. However, despite these initiatives, many rural regions struggle with economic stagnation due to limited infrastructure, inadequate promotion, and poor stakeholder cooperation.

Rural walking tourism, a form of nature-based, low-impact travel, has emerged as a promising strategy for revitalizing these areas. Walking tourism offers ecological benefits by minimizing carbon emissions and environmental degradation while supporting local economies through distributed visitor flows and small-scale, locally managed tourism experiences [3]. It also fosters deeper engagement with place, enabling tourists to form emotional connections with natural and cultural landscapes.

From a sociological perspective, theories of social capital and community resilience provide a valuable framework for understanding how local networks and strong community ties can drive sustainable tourism development [15]. These frameworks emphasize the importance of stakeholder collaboration through resource sharing and decision-making and by reinforcing community identity in the face of socio-economic challenges. In parallel, geographical theories, such as place attachment and spatial identity, highlight how emotional bonds shape tourists’ experiences and behaviors [16,17], reinforcing sustainable practices and the stewardship of local resources.

However, even as sustainable tourism practices gain global attention, empirical research remains limited on how these frameworks operate in sensitive rural contexts with geopolitical constraints or strict environmental protections. Tourism models in militarized zones remain underexplored in terms of governance, operational constraints, and stakeholder dynamics. This gap is evident when comparing the DMZ with other conflict-influenced destinations, such as Northern Ireland or the Middle East, where research has emphasized the importance of trust-building, visitor safety frameworks, and multi-scalar governance mechanisms for tourism viability [18]. As a human-powered, low-density activity, walking tourism presents a viable strategy that balances ecological conservation, local participation, and cultural education. Its integration into post-conflict or militarized zones, however, requires adaptive management that can reconcile conservation imperatives, safety concerns, and narrative sensitivity [19]. It aligns with the broader goals of slow tourism, which emphasize mindful travel, meaningful encounters, and community well-being [8].

2.2. From Border Constraints to Trail-Based Innovation

In South Korea, the revitalization of economically disadvantaged rural areas through tourism has been pursued via various national strategies. A particularly complex example is the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), which has recently been reimagined as a site for sustainable tourism despite its long history of military protection. Stretching across a 248 km military demarcation line, the DMZ region encompasses municipalities experiencing economic decline and population loss. Several areas, such as Ganghwa, Goseong, and Cheolwon, are experiencing sustained depopulation, highlighting the need for innovative approaches to regional revitalization [20,21].

From an ecotourism perspective, the DMZ’s restricted access over the past 70 years has preserved its natural environment. Spanning roughly 907 square kilometers, it supports diverse ecosystems and endangered species. In recognition of its ecological value, sections of the DMZ were designated as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in 2019 [22]. The creation of the Peace Path, a 510 km, 35-course walking trail, demonstrates how walking tourism has been integrated into policy efforts to promote regional development in a low-impact, culturally sensitive manner.

Additionally, under the Green Détente policy, walking tourism has been used as a peacebuilding mechanism between North and South Korea. These initiatives reflect a convergence of ecological conservation, historical storytelling, and community-based tourism strategies within a geopolitically sensitive zone [23,24].

The DMZ tourism sector struggles due to political complexity, fragmented governance, and uneven regional capacity. Sustainable tourism development in these areas requires an understanding of military governance structures, which limit access yet provide an organizational framework (including security enforcement and access control) to support tourism management efforts. The region’s fragile ecological condition requires strict tourism flow regulations and promotes low-impact activities, such as walking tourism. Military and ecological factors are central determinants for stakeholder cooperation, tourism narrative development, and access regulation in the DMZ [25].

A specific application of the UNWTO three-pillar framework, which includes economic, environmental, and sociocultural sustainability, needs customization to fit militarized areas [3]. Economic sustainability requires implementing limited yet valuable tourism products under strict operational conditions. Protected ecosystems require strict conservation measures as part of environmental sustainability, which includes backing nature-based tourism activities, such as walking. Peace-centered storytelling combined with joint efforts between military personnel and civilians establishes sociocultural sustainability by strengthening community bonds and trust [22].

Nevertheless, the DMZ Punch Bowl Dulle-Gil offers a rare example of sustainable walking tourism implemented through cooperation among military authorities, government agencies, and residents. It demonstrates how trail-based tourism can address rural challenges while aligning with national sustainability goals [25].

3. Materials and Methods

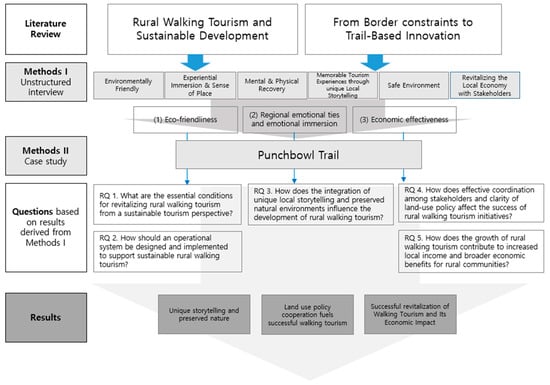

As shown in Figure 1, our research framework integrates theoretical perspectives with empirical inquiry to explore the development of sustainable walking tourism in geopolitically sensitive rural regions.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

This study was conducted in two phases to systematically explore the key conditions and strategies for promoting sustainable rural walking tourism. In Study 1, in-depth interviews were conducted with experts possessing practical experience and professional expertise in walking tourism. This step aimed to generate insights into rural walking tourism’s status, key challenges, and sustainability conditions. Building on these exploratory findings, Study 2 employed an in-depth single case study method to analyze practical examples where rural walking tourism successfully generated positive ecological, economic, and sociocultural impacts for local communities and tourists. Integrating expert perspectives (Study 1) and real-world case analyses (Study 2) gave comprehensive insights into effective sustainability-oriented walking tourism practices.

Ethics and Validity of the Study

To ensure the ethical integrity of this study, participants were informed via email or text before its commencement about the study’s purpose, scope, and content, the anonymity of their responses, and their right to participate voluntarily. During the interview process and upon its conclusion, we engaged in discussions with participants to review the interview content and research direction, addressing any concerns regarding anonymity or potential conflicts of interest. By implementing these measures, we aimed to uphold high ethical standards while enhancing the qualitative rigor and reliability of the research [26].

We adopted a prudent, objective, and systematic approach to ensure the trustworthiness of the results and interpretations in this qualitative study. Specifically, we established three selection criteria for participants: (1) a minimum of 10 years of experience in the tourism sector, (2) relevant experience in walking tourism-related work, and (3) experience in overseeing both field and administrative aspects of tourism operations. These criteria ensured that participants could provide comprehensive insights, reflecting macro-level social changes and evolving trends in the tourism industry. Recognizing the challenge of finding participants who meet all these conditions, we initially identified a researcher with a long-standing focus on walking tourism, dating back to the early 2000s, and invited them via email. The researcher recruited additional qualified participants after the initial interview, resulting in a total of 10 expert interviews. Relevant cases were further examined based on the insights gained from these interviews. Throughout this process, the appropriateness of the selected cases was continuously reviewed and discussed via text messages and emails.

Second, we recorded and transcribed the interviews, read them multiple times, and engaged in a thorough reflection. Additionally, to mitigate researcher bias or dogma, we discussed the content, process, and descriptions with two doctoral-level researchers experienced in qualitative research. For example, we deliberated on the ranking of outcomes by weighing their importance, ultimately concluding that all six initially considered outcomes were essential to understanding the value of walking tourism.

Third, to bridge the gap between the field context and research findings and to enhance the study’s transferability, the research results were reviewed and discussed with the interviewees via text or email. This iterative process helped fulfill the criteria of credibility, dependability, transferability, and confirmability [26,27].

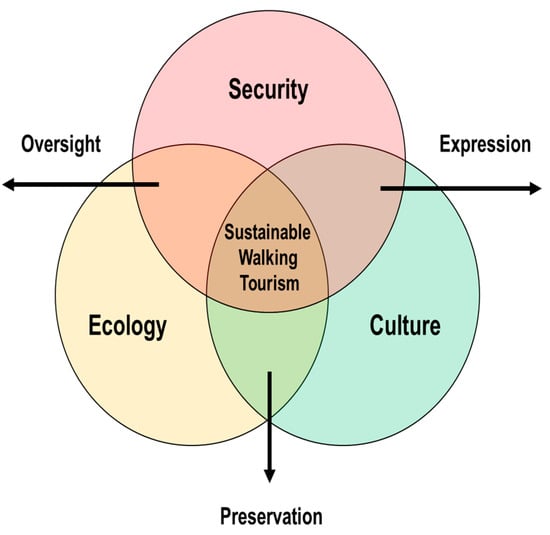

A visual model (Figure 2) demonstrates how security interactions with ecology and culture drive sustainable walking tourism development in rural military zones. This research’s empirical results and previous sustainable tourism governance theories form the model’s foundation. Security serves as a boundary condition requiring coordination while constraining actions within this framework, while ecology stands as the essential environmental asset to protect, and culture, through local storytelling and practices, delivers emotional value and unique narratives. When these three areas intersect, they form a tourism system that delivers safety, environmental awareness, and cultural significance. The tripartite interaction between these sectors develops dynamically through stakeholder negotiations alongside institutional arrangements. The model demonstrates how collaborative governance processes integrate these elements to guide tourism development that withstands geopolitical limitations.

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework of sustainable walking tourism in militarized ecological zones: balancing security, ecology, and culture.

4. Study 1: Exploring the Conditions for Sustainable Walking Tourism Through Expert Interviews

4.1. Study 1: Exploring Walking Tourism—Expert Perspective

The purpose of Study 1 was to explore the characteristics of rural walking tourism necessary for its sustainability. Specifically, the study aimed to identify the key attributes and operational conditions that contribute to the sustainable development of rural walking tourism by examining real-life examples. To achieve this, we employed purposeful sampling, selecting experts with more than 10 years of experience in tourism, walking tourism, and both field and administrative work in South Korea. The study utilized unstructured interviews to collect comprehensive, in-depth narratives. We asked minimal questions to elicit their stories and then focused on their experiences, thoughts, and feelings. Subsequent questions were naturally fluid and expanded based on their answers [16]. And Things related to the ecological, historical, cultural, and economic value of places in the DMZ border area answers [18]. Moreover, these experts were established professionals in their respective fields and enthusiasts of walking tourism as a form of serious leisure, placing them in a good position to describe walking tourism from both a professional and a user’s perspective.

4.1.1. Interview and Data Collection

Interviews for data collection were conducted in person or by phone, depending on the participants’ schedules and work locations. The data collection spanned three weeks, from 10 February to 5 March 2025, during which two interviews were conducted, each lasting between 40 and 90 min. This duration ensured participants had sufficient time to provide thoughtful, focused responses. The interviews were conducted until content saturation was achieved, resulting in a final sample of 10 participants. The interview profiling is as shown in Table 1. Saturation was determined when no new codes or conceptual insights emerged in the final two interviews, indicating that the data had become thematically redundant. The participants were professionals with 10 to 30 years of experience in tourism-related fields in Korea, working in private or national organizations or conducting academic research on walking tourism. Most hold master’s or doctoral degrees in tourism, equipping them with theoretical expertise and practical insights, ensuring a solid understanding of the field. Experts were selected using purposive sampling based on their long-term involvement in walking tourism development, site management, or tourism policy.

Table 1.

Interviewees’ profile.

4.1.2. Interview Data Analysis

The constant comparison method was employed to achieve the research objectives, and the analysis was conducted using open, axial, and selective coding procedures [28]. Two researchers independently conducted open coding by closely reviewing each transcript line by line to identify repeated, meaningful expressions. Codes were initially developed using in vivo and descriptive labels. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved collaboratively. In the axial coding stage, these codes were clustered into higher-order categories by examining patterns, causal conditions, and interrelationships. We maintained a shared codebook and documented coding decisions in an audit trail to ensure analytic transparency. Finally, selective coding was used to integrate the axial categories into overarching themes that reflected the participants’ collective narratives. Simultaneously, the relevant literature was examined to assess its appropriateness and validity, considering the emerging analysis [29]. Therefore, the theory, analysis, and results are interconnected in a circular manner.

We applied a hybrid approach combining deductive and inductive coding to ensure analytic transparency. The initial coding framework was informed by sustainability-oriented tourism frameworks (e.g., environmental conservation, local revitalization, visitor experience), allowing new categories to emerge inductively from the interview data. Through iterative clustering and refinement, six primary thematic categories were identified and summarized in Table 2: (1) environmentally friendly practices, (2) experiential immersion and sense of place, (3) mental and physical recovery, (4) memorable tourism experiences through unique local storytelling, (5) safe environment, and (6) revitalizing the local economy through stakeholder cooperation. These themes reflect the most frequently referenced and meaningfully interrelated elements across the interviews.

Table 2.

Results of participant interviews.

Accordingly, this study conducted interviews on walking tourism, and through participants’ responses, the theory was extended to slow travel. Furthermore, the appropriate trial cases were selected in consultation with the participants, integrating empirical findings with theoretical insights throughout the research process.

4.1.3. Results

- (1)

- Environmentally friendly

Interview findings suggest that walking tourism is a relatively environmentally friendly tourism activity because it minimizes carbon-emitting transportation, such as airplanes and cars, and utilizes the human body as a means of slow movement. Additionally, one participant established and operated a private organization dedicated to walking tourism and spearheaded initiatives to protect the local mountain’s natural ecosystem through educational programs. Participants viewed their engagement as an immersive opportunity to reconnect with nature, heightening their awareness of environmental preservation.

Participants expressed a common perception that walking tourism is eco-friendly because it generates almost no carbon emissions, primarily due to its reliance on human-powered movement.

I think walking and cycling are the only forms of transportation that utilize the human body to move, making them eco-friendly forms of tourism with minimal carbon emissions.(Participant 3)

When I walk on the path connected to the course for walking tourism, I feel that I am one with life in nature.(Participants 6 and 7)

The walking paths in the city serve multiple purposes. Still, when comparing the paths in the city and those in the countryside, the primary purpose of walking in the countryside is for strolls, making the beautiful natural environment a crucial aspect. Consequently, the purpose of ecotourism is served.(Participants 9 and 10)

The participants noted that the rural walking paths, explicitly designed for pedestrian use, highlight how an unspoiled natural environment promotes ecotourism (Participants 9 and 10). Participants emphasize that eco-friendly tourism not only conserves the natural environment but also serves an educational function by preserving local history and culture.

The reason why I decided to create a path for walking tourism was that I was involved in a citizen’s solidarity group to protect the mountains in my area, and I was campaigning against development. At the same time, a circumferential path was being built in Korea, which gave me a hint. I approached it from the perspective of education to preserve local ecology, history, and culture.(Participant 5)

When we walk through the forest, we sit under a tree or a rock, have a quick snack, and bring our trash in a bag. It has religious significance, so we want to preserve it better.(Participant 6)

- (2)

- Experiential Immersion and Sense of Place

Participants described walking tourism as cultivating a “sense of place” through sensory engagement (e.g., sounds, smells, colors), enabling tourists to form deeper connections with local environments through slow movement and physical engagement [16]. This experience fosters mindfulness, encourages reflective observation, and develops a sense of familiarity, which can be understood through three dimensions: place identity, place attachment, and place dependence [30]. Additionally, the storytelling of local guides further enriches tourists’ understanding of regional history and culture [31]. By discovering hidden gems, such as narrow alleys and small shops, walking tourism offers an off-beat and immersive experience [32] that allows tourists to feel like locals.

Participants who experienced the sense of place referred to by Tuan [16] during walking tourism reported feeling as if they were residents of the area. This suggests that the ecological environment and local uniqueness strongly influence place identity, place attachment, and place dependence in rural walking tourism [30].

When you go on a walking tour, you get to see the unique aspects of the area, not like a tourist, but like a local. I feel like you get to see the real thing about the area. When I go on a walking tour with my friends on the weekend, I feel like I get to see the place inside and out and live like a local, unlike when I visited a tourist spot before.(Participant 4)

When you use your body and walk at a slow pace, you become sensitive to your surroundings —the wind, the air, the trees, the houses, everything that exists as you pass by—and then you see everyday things in a new light. You have a special experience that you don’t get in a typical tourist destination, and you remember it vividly afterward.(Participants 3 and 10)

According to Urry [10], non-mainstream and differentiated tourism experiences, such as discovering small shops or hidden places, help tourists feel like locals. These immersive experiences can significantly strengthen local bonds and foster deep emotional attachments.

For instance, one participant described a typical day on a countryside trek:

A 4-km walk for an adult can take an hour, but if you connect with mountain trails, it can take up to an hour and a half. Suppose you are trekking 10 to 15 km in the countryside. In that case, a typical schedule might include walking 5 km in the morning, taking a break for lunch, and then walking another 5 to 7 km in the afternoon. While walking, you can enjoy nature and discover unique local resources, which helps you form a positive image of the area and develop an affection for it. Afterward, you might have an extra meal or buy snacks and local specialties, which naturally increases local spending.(Participant 8)

When I was trekking in Japan, I saw vegetables and fruits at local specialty stores, and I felt like I was indeed in the Japanese countryside. I felt like talking to the people who grew those vegetables and fruits, so it was nice.(Participant 7)

- (3)

- Mental and Physical Recovery

Participants reported that walking tours contributed to mental and physical recovery. This aligns with previous studies demonstrating that walking tourism has a positive impact on tourist satisfaction by providing an experience that alleviates daily stress [12]. Furthermore, research on long-distance walking indicates that journeys spanning multiple days can significantly reduce mental stress [13]. These findings suggest that walking tourism can serve as an effective measure for both stress relief and overall mental health recovery. Additionally, even shorter walks of 12 km or less, or those completed within a day, can have a positive impact on both mental and physical health, regardless of age. A study on college students experiencing sleep disorders found that walking outdoors fostered mindfulness, improved sleep quality, and reduced mood disorders [33].

In line with previous studies indicating that walking tourism fosters self-reflection, participants described significant mental stress relief and satisfaction. For instance, one participant noted that “When I am walking, I clear my mind of distractions; if I have worries or problems to solve, I simply walk to regain focus”.

Another participant shared that having a companion during a walk enhances the experience by allowing them to converse and relieve stress, benefiting both mental and physical health.

In my daily life, I often travel by car and sit down to work, so there are days when I don’t take even 200 steps.(Participant 6)

Furthermore, several participants emphasized that once they begin walking, their problems seem trivial in the expansive outdoors. They acknowledged that while returning to work might reintroduce stress, the act of walking provides them with renewed strength and better sleep at night.

Once I am walking, I feel like my problems are very small and trivial in the great outdoors. Of course, when I return to work, I will face stressful situations again, but upon reflection, I feel confident that I have the strength to overcome them. I sleep better at night because I walked a lot.(Participants 1, 8, 9, and 10)

- (4)

- Memorable Tourism Experiences through Unique Local Storytelling

Participants emphasized that unique local storytelling played a vital role in making walking tours more meaningful and memorable. Previous studies suggest that narratives highlighting a region’s history, culture, and natural environment not only motivate walking tourists by evoking a sense of the local history, culture, and natural environment but also forge deep emotional connections that enhance the overall experience. For instance, in DMZ tourism, storytelling that encompasses historical, political, and ecological contexts enhances the emotional response and sense of immersion [34]. Moreover, storytelling serves an educational function by transforming destinations into dynamic spaces where learning and experience converge, fostering cultural enrichment and critical reflection [35]. This suggests the potential of storytelling to turn a destination into a living classroom where experiential learning and cultural exchange mutually reinforce one another.

Participants noted that they were emotionally connected and immersed in the region’s storytelling, which effectively conveyed its local history, culture, and natural beauty. One participant explained

While working in walking tourism, I became increasingly curious about DMZ peace tourism and decided to participate in some tours. It is good for security tourism and also suitable for ecotourism because of its unique and beautiful natural environment. This is a place where many soldiers died during the Korean Civil War, and as it is the closest area to North Korea, you must follow a cultural guide. It offers not only beautiful natural scenery but also the important historical story of Korea, making it more memorable than other places. Moreover, it is said that local residents actually benefit from the spendings of walking tourists, so I felt like I was contributing to the local economy as a walking tourist.(Participants 3 and 10)

The attractiveness of a tourist destination is important, but I believe stories are what truly make a destination attractive. For example, the success of Jeju Olle was due to its creation to show people the hidden places and paths that local residents used to walk. Walking tourism is about enjoying the scenery and the stories that draw people in. For younger generations, knowing how to engage and what to do as part of entertainment culture is also important.(Participant 1)

The Dalma-godo Trail in Haenam-gun is located on Dalma Mountain behind Mireuksa Temple. The chief monk of Mireuksa Temple first proposed building the trail, but he requested that it be constructed entirely by hand, eschewing mechanized construction methods. It was likely intended for monks to use as part of their practice. As a result, the Dharma Road is barely wide enough for two people to pass each other. People dug the ground by hand and used the stones that came out to build embankments or make roads. This effort became a story, making the trail famous and attracting many visitors. Since there are no restaurants or shops nearby, visitors can order lotus leaf rice in advance at Mireuksa Temple, and it will be prepared for them upon arrival. While there are limited local amenities, the culinary and souvenir offerings at Miresa Temple can become unique attractions in their own right.(Participant 3)

However, some participants cautioned that overemphasizing storytelling might lead to interventions, such as incongruent sculptures, that disrupt the natural landscape and compromise safety. They emphasized that compelling storytelling must preserve the natural environment and maintain the authenticity of local culture, with strong backing from both the government and local community.

Participants also expressed concern that, in some cases, an excessive emphasis on storytelling may lead tourists to stray from designated paths, potentially harming natural landscapes and compromising safety. Therefore, while compelling storytelling enhances the tourism experience, it should be carefully balanced to ensure the preservation of the natural environment and the authenticity of the local culture. Achieving this balance requires strong government support and cooperation from residents.

For people who walk, safety through appropriate rest areas, clear signage, and security measures are paramount. While storytelling is essential for enriching the walking experience, it must be carefully balanced with safety considerations to avoid incongruent or disruptive interventions that could undermine both the natural setting and tour quality. One reason is that it is advantageous when receiving government funding.(Participants 1, 3, 5, 9, and 10)

- (5)

- Safe Environment

Participants emphasized that creating a safe environment is the most critical factor for the success of walking tourism. As a prerequisite for its revitalization, establishing basic safety infrastructure, such as pedestrian-only roads, rest areas, clear signage, information centers, and security systems, should be prioritized from the initial design stage. These measures ensure physical and psychological safety, a hallmark of advanced tourism [36]. Moreover, prior research identified four dimensions of safety: natural disasters (e.g., environmental pollution), social disasters (e.g., traffic accidents, incidents, public safety, diseases), life safety information (e.g., weather updates, healthcare facilities, information media), and security crisis information (e.g., war, terrorism). These dimensions serve as a comprehensive framework for safety management. Participants frequently cited Jeju Olle as a successful example of walking tourism in Korea, demonstrating how well-planned safety infrastructure can contribute to the continued development of walking tourism and local economic revitalization [37].

However, participants also expressed safety concerns. For example, in July 2012, the murder of a 40-year-old woman on Jeju Olle shocked the nation, underscoring vulnerabilities associated with the open and linear nature of walking tourism. Field studies further indicate that overly secluded and deserted environments can heighten feelings of insecurity and elicit negative psychological responses among walkers [38]. Moreover, participants stressed the importance of proactive planning to address complex safety challenges in natural environments, such as potential threats from wild animals.

Previous studies [37,38] classified safety management facilities on walking trails into four dimensions: safety facilities (e.g., dedicated walkways, lighting, night-vision CCTV, warnings about wild animals and plants, emergency rescue systems, and guard posts), information facilities (e.g., information boards, directional signs, QR code-based guidance), and convenience facilities (e.g., benches, viewing decks, toilets, drinking fountains, trash receptacles), and memorial facilities (e.g., memorial stones and cultural storytelling centers). These facilities ensure safe and convenient access for pedestrians.

According to the participants, establishing a safe environment for rural walking tourism not only protects tourists but also increases local consumption, positively impacting the vitality of rural areas and farmers’ income.

In Japan, I saw unmanned stores selling local farm products, which made me feel it was a safe place, showcasing how well-developed the walking trail infrastructure is. These days, there are fewer young people in rural areas, and not many young tourists walk. I am considering a program that utilizes vacant houses with good infrastructure for dinner and overnight stays, in return for which young people can assist busy farmers while walking around.(Participant 8)

Meanwhile, participants emphasized that sustained safety requires consistent maintenance, adequate budget allocation, and strong collaboration among local communities and other stakeholders.

Since the early 2000s, I’ve been involved in walking tours with a focus on cultural exploration, and I’ve been walking for 23 years. I’ve participated in creating local walking trails and contributed to research and books. For example, when we made the Hae-Parang Trail, safety was our top concern. There are many traffic accidents along the trails. The trails on mountains or embankments used to be safer, but now, with well-built roads, passengers can travel safely. Still, creating a safe environment, including signs, rest areas, and information centers, requires constant management.(Participants 1 and 3)

Walking tourism is common in developed countries because safety infrastructure is a prerequisite, like pedestrian-only roads, shelters, signs, and security. In Korea, a famous trail experienced a murder incident, causing a decline in walking for a while. Thus, safety is paramount. Additionally, when walking deep in the mountains, there are risks from wild animals, such as snakes or boars, so group travel is recommended. Still, Korea has developed interconnected trails similar to those found in advanced countries. And because these trails require maintenance, substantial budgets are needed.(Participants 2, 3, 9, and 10)

- (6)

- Revitalizing the Local Economy through the establishment of a cooperative system with Stakeholders

Participants emphasized the need to establish a cooperative system among stakeholders to ensure the sustainability of walking tourism. Prior research highlights that active local community participation and stakeholder cooperation are essential to the development of sustainable tourism. These partnerships facilitate the smooth integration of economic, environmental, and social considerations within ecotourism and sustainable tourism frameworks [39]. For instance, sustained government funding is essential for preserving tourism operations, advocating the need for active local community engagement. Thus, a strong community cooperation system not only benefits residents and promotes tourism development but also fosters optimism regarding the potential of sustainable walking tourism, ultimately leading to local revitalization [40].

Participants agreed that securing sufficient budgets and the understanding and cooperation of all stakeholders are essential for the revitalization and sustainability of walking tourism.

We operate within budgets allocated by the Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism and the Ministry of the Interior and Safety. However, since we conduct commissioned projects, sometimes our budget proposals are ignored or reduced, which is frustrating. The government’s budget support is critical for sustainability, so when that part doesn’t go well, it’s very stressful.(Participants 1, 5, and 7)

In walking tourism, it is crucial to have a large number of people involved to ensure safety. Promotion is essential to attract visitors through walking clubs and word of mouth. However, a sufficient promotional budget is also required.(Participants 2 and 3)

Participants noted that efforts to revitalize rural economies and increase local income through walking tours are heavily dependent on stakeholder cooperation. Regional cooperation and robust support systems are, therefore, indispensable for promoting walking tourism and stimulating local economic development [40,41].

We have attempted to establish a base village, run programs, and offer bed and breakfast services. However, the business did not perform well because we were unable to hire staff due to budget limitations. Also, since the four regions are united, the number of tourists walking the trails is not consistent across all courses. Therefore, I am trying to utilize vacant houses or idle land for backpacking accommodations. Visitors pay a certain fee to use the village spaces. I am preparing to improve and support these initiatives after receiving approval from the village.(Participant 5)

In Korea’s security tourism, tourists are required to follow a cultural guide. The areas where walking tours are conducted as part of security tourism tend to be sparsely populated, allowing residents and the region to share in the economic benefits generated by the tourists. In well-developed walking tourism areas, residents often contribute suggestions to promote walking tourism, and these suggestions are frequently adopted in practice.(Participants 8, 9, and 10)

5. Study 2: Case Study: Analysis of a Rural Walking Tourism Case

Characteristics of Walking Tours as Sustainable Tourism Derived from the Interview Results

Based on the interview results, three characteristics of walking tourism that contribute to revitalizing rural walking tourism have been identified. First, walking tourism is environmentally friendly. It is an eco-friendly form of tourism that minimizes carbon emissions by relying on human-powered movement rather than high-carbon transportation. Utilizing pre-existing trails minimizes the environmental impact while preserving natural landscapes. This approach aligns with the core principles of sustainable tourism outlined by the UNWTO [1], which emphasize the preservation of ecosystems and the efficient use of natural resources. Consequently, walking tourism not only safeguards biodiversity but also enhances tourists’ ethical awareness of low-carbon practices, reinforcing the importance of environmental conservation [11].

Second, walking tourism is characterized by strong local emotional ties and a high level of emotional immersion. During slow travel, tourists develop a profound sense of place by engaging their senses and experiencing the wind, sounds, scents, and vital cues of the surrounding scenery [16,30]. Rather than focusing on mainstream tourist attractions, they encounter everyday local life imbued with historical significance and cultural authenticity. These non-mainstream tourism experiences enable tourists to immerse themselves in the community as if they were residents [32]. Storytelling further enriches this connection, deepening their understanding of the region’s history and culture. This emotional connection is essential for fulfilling the social and cultural dimensions of sustainable tourism [17].

Third, walking tourism has a strong economic impact. Walking tourists contribute directly to the local economy by spending on food, lodging, and local products [4,12], generating jobs and stimulating local economic activity. However, sustaining these economic benefits requires strong cooperation among local communities, governments, and the private sector [39,40]. This collaboration for designing and implementing walking tours ensures the fulfillment of regional needs while promoting overall economic revitalization. Together, these three elements—environmental sustainability, emotional immersion, and economic effectiveness—form the foundation of sustainable tourism, as outlined by the UNWTO [3].

The six themes derived from the primary interviews in this study (Study 1) are (1) environmental friendliness, (2) regional and emotional ties and a sense of place, (3) mental and physical recovery, (4) memorable tourism experiences through storytelling, (5) a safe environment, and (6) revitalizing the local economy through stakeholder cooperation. However, in Study 2, the case study focused on three key factors—environmental friendliness, emotional attachment to the region, and immersion—as the key analytical framework.

The reasons are as follows. First, it is central to the sustainability of walking tourism. According to the UNWTO [1], the three key pillars of sustainable tourism are (1) environmental sustainability, (2) social and cultural sustainability, and (3) economic sustainability. Thus, this study focused on three themes—environmental sustainability, emotional immersion, and economic revitalization—that are directly related to the three pillars of sustainability proposed by the UNWTO [1,2,3]. Second, these themes offer strong feasibility for case analysis. Case studies require factors that can be observed in real-life regions for in-depth analysis. While we recognize the importance of storytelling, safety, and stakeholder collaboration discussed in the interviews, these factors can be indirectly reflected in the abovementioned themes. For example, we determined that storytelling is a key component of local emotional immersion and that stakeholder cooperation can be a significant factor in achieving economic effectiveness. Third, structural conditions for the revitalization of rural walking tourism were prioritized. Unlike urban areas, rural areas face structural constraints, including population decline, inadequate infrastructure, and limited tourism demand. Therefore, long-term operation would face challenges unless a structure is created where residents can directly benefit from walking tourism to revitalize the area [39,40].

- (1)

- Research questions

This study adopted Yin’s case study methodology to empirically analyze cases based on the themes derived from the interviews. This approach is beneficial for investigating research questions that seek to understand how and why particular social phenomena occur [42]. The unit of analysis serves as a standard for establishing the temporal and content boundaries of the study, ensuring clarity in data collection and analysis. Accordingly, the unit of analysis in this study was defined by reorganizing the themes identified from the previous interviews within the sustainable tourism framework. The final units of analysis consist of three dimensions: (1) eco-friendliness, (2) regional emotional ties and emotional immersion, and (3) economic effectiveness.

Based on these units of analysis, this study aims to identify the essential conditions and operational mechanisms for revitalizing rural walking tourism within a sustainable tourism framework.

Accordingly, the research questions guiding this study are as follows:

- RQ1: What are the essential conditions for revitalizing rural walking tourism from a sustainable tourism perspective?

- RQ2: How should an operational system be designed and implemented to support sustainable rural walking tourism?

- RQ3: How does the integration of unique local storytelling and preserved natural environments influence the development of rural walking tourism?

- RQ4: How do effective coordination among stakeholders and clarity of land use policy affect the success of rural walking tourism initiatives?

- RQ5: How does the growth of rural walking tourism contribute to increased local income and broader economic benefits for rural communities?

- (2)

- Data Collection and the Validity and Reliability of the Research

To qualify as a case study, a case must exhibit significance, extremity, rarity, and longitudinal characteristics [43]. Given these criteria, this study excluded widely researched cases, such as Jeju Olle, and instead focused on Dulle-Gil trails within the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). The DMZ is an area that has been restricted from development due to division and military tension since the Korean War. Nevertheless, it has preserved unique ecological resources, historical sites, and security-related features for over 70 years. Therefore, both high expectations and significant concerns coexist regarding the revitalization of walking tourism in this region. After extensive exploration of potential cases and consultations with experts, the DMZ Punch Bowl Dulle-Gil in Yanggu County was selected as the final case study.

To systematically investigate the research questions, a case study protocol and database were developed, including research objectives, case selection criteria, data collection and analysis methods, and strategies to ensure reliability and validity. The theoretical framework was established based on various primary and secondary sources, such as the academic literature, official publications, field interviews, and policy documents, to ensure consistency with existing studies.

During the selection process, in-depth interviews and consultations with walking tourism experts were conducted to identify cases aligned with the research questions and units of analysis. This evaluation focused on two key factors: (1) the role of unique storytelling and preserved natural environments in revitalizing walking tourism and (2) the necessity of multi-stakeholder cooperation for effective land use and tourism management. Consequently, the DMZ Punch Bowl Dulle-Gil was selected as a representative case that requires complex stakeholder cooperation, including military and security authorities, ecological preservation agencies, residents, cooperatives, and organizations, such as the Korea Forest Service.

During the data collection and analysis phase, a triangulation approach was employed using multiple data sources. Specifically, we examined in-depth stakeholder interviews, analyzed policy documents, and reviewed previous research. Additionally, field observations from site visits and photographic documentation were incorporated to cross-validate findings and ensure methodological rigor. These collected data were systematically categorized into three analytical units: (1) eco-friendliness, (2) regional emotional ties and immersion, and (3) economic effectiveness and cooperation.

This process allowed for an in-depth analysis to examine how the preservation and utilization of local resources, resident participation, and stakeholder cooperation contribute to the revitalization of walking tourism. Furthermore, the study empirically assessed whether local resources and storytelling play a pivotal role in revitalization and whether walking tourism is a viable option positively impacting the local economy.

Furthermore, to enhance the validity of the research findings, interviews were conducted with local experts who have worked in the area for an extended period and possess knowledge of the actual operation of walking tourism, stakeholder interactions, and the status of tourist usage. These efforts were critical in ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the study’s results. This triangulated data strategy, incorporating interviews, observations, and document analysis, was critical for ensuring the accuracy, reliability, and credibility of the study’s results.

- (3)

- Case Selection

The Punch Bowl in Yanggu, Gangwon-do, situated near the North Korean border, holds historical significance as the site of intense battles during the Korean War. Due to its location near North Korea, a military base operates in the region, enforcing strict security protocols. While it has become a tourist destination, the area still poses risks due to residual landmines from past conflicts.

Therefore, reservations are required for walking tours, and tourists must travel in guided groups supervised by local cultural guides and safety personnel. Military authorization and effective communication are essential for ensuring security, while cooperation with relevant agencies, such as the Korea Forest Service, is critical for addressing ecological protection concerns. Moreover, coordinating land use policies through collaboration with various stakeholders, including residents and cooperatives, is essential for the successful operation of walking tourism.

Interestingly, these same security risks have inadvertently helped preserve the region’s unique ecological environment. The name “Punch Bowl” itself holds historical and cultural significance, offering visitors insights into Yanggu County’s unique identity, especially given its proximity to North Korea.

Moreover, since the DMZ Punch Bowl Dulle-Gil is a key security and ecological zone, no restaurants are available along the trail. In response, local villagers have organized a cooperative offering Forest Meals, made from locally harvested produce, to tourists for approximately KRW 10,000 (approximately USD 7). Tourists may also purchase local herbs featured in these Forest Meals, a cooperative initiative that has become a significant source of income for residents. For these reasons, we selected the DMZ Punch Bowl Dulle-Gil in Yanggu, Gangwon Province, for the case study. The validity and reliability of the study were enhanced through interviews with a local expert with over 30 years of local experience, including serving as a public official. The characteristics of the participants are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the study participant.

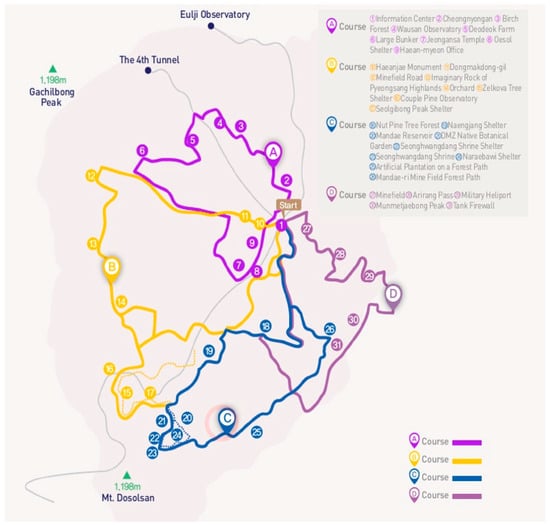

Also, Yanggu is the northernmost region in South Korea, and part of the walking trail follows the former southern border fence, earning it the name DMZ. This allows visitors to experience a trekking course within the border area. In particular, the Peace Trail course allows visitors to experience remnants of war and division, such as trenches, bunkers, and the Fourth Landmine Field, which remain today. On the other hand, Gachilbong Peak, located at the northern end of the perimeter trail, is situated just 780 m away from North Korean guard posts across the Military Demarcation Line. As a result, it is located in a militarily significant and dangerous area [41]. DMZ Punch Bowl Dulle-Gil is specifically presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

DMZ Punch Bowl Trail (Dulle-gil) courses (source: ygtour). DMZ Punch Bowl Dulle-Gil has a total of four courses: Course A: Pyeonghwauisup-gil (14 km, approximately 4 h), Course B: Oyubat-gil (21.12 km, approximately 5 h 30 min), Course C: Mandaebeolpan-gil (21.9 km, approximately 5 h 30 min), Course D: Meonmaetjae-gil (16.2 km, approximately 4 h 20 min).

6. Results

6.1. Unique Storytelling and Preserved Nature

Figure 4 is one of the DMZ Punchbowl Trail courses, located in Haean-Myeon, Yanggu-gun, Gangwon-do. The name “Punch Bowl” was coined by an American journalist who described the basin as evoking the image of a punch bowl. A brief historical context is essential for understanding the significance of this event. A large-scale armed conflict broke out on the Korean Peninsula on 25 June 1950, with North Korea supported by the Soviet Union and China, and South Korea backed by the US and 15 United Nations allies. The war lasted more than three years and ended in a ceasefire with the signing of the armistice on 27 July 1953 (National Archives of Korea).

Figure 4.

Punch Bowl Trail (Dulle-Gil) in Yanggu Country, offering views of villages in a punch owl-like landscape.

Haean-Myeon was a strategically vital area during the Korean War. Intense battles were fought to secure defensive positions and neutralize enemy advances. Although the area was eventually secured, approximately 2452 casualties occurred during the 14 days of combat in the war’s later stages.

This region remains strategically significant, with the armistice line between the South and North Korean guard posts positioned just 780 m apart. Visitors can see Mount Geumgang in North Korea from this area. Due to the presence of landmines left from the war, all visitors must strictly adhere to designated safe paths and observe all landmine warning signs. The landmine warning signs in Figure 5. Give a sense of the fierce battles that took place at that time.

Figure 5.

Landmines are still present along the DMZ Punch Bowl Trail (Dulle-Gil). The Non-English word in the photo refers to the Korean word for ‘landmine’.

Access to the DMZ Punch Bowl Dulle-Gil is permitted only through prior reservation and approval from the military. Two professional forest guides accompany visitors to ensure their safety and well-being. Thus, this trail serves as a symbolic space where visitors can reflect on the tension arising from proximity to North Korea, the devastation of war, and the importance of peace. Additionally, it offers a compelling storytelling experience, providing educational and cultural value by immersing visitors in the ongoing reality of division.

The mountains of North Korea are visible from this forest trail, as North Korea is about five kilometers away. So, there is no choice but to control the military units for security reasons. Many areas are characteristic of our Dulle-Gil. However, it is safe to walk only on the designated paths because the military units detected the mines when they built the forest paths. It is dangerous but attractive. Due to the presence of mines and security concerns, the number of people allowed is limited to approximately 200 per day, and CCTV has been installed in certain sections. At 9:20 a.m., a resident, who is also a forest trail guide, leads the group, with 25 to 40 guides assisting the guide. There are a total of six forest trail guides. They guide and protect the front and are the backbone of the group because mines are hazardous for tourists unfamiliar with the area. Sometimes, they sneak in and collect the fruit without permission, and when the military catches them, they claim to be lost tourists. Even though the place where they were was not a trail at all. Moreover, we check and report the time and location of everything.(Director)

Meanwhile, the history of restricting civilian access for security purposes has contributed to preserving a pristine forest ecosystem in Yanggu Province, specifically within the Forest Genetic Resource Conservation Area. As a result, the DMZ Punch Bowl stands out as a prime destination for both security tourism and ecotourism due to its exceptionally well-preserved natural environment. Recognizing its ecological conservation efforts, historical significance, and cultural value, it was designated South Korea’s No. 1 national forest trail in 2021 [21].

The director said

There is little artificial development here. Due to border-area restrictions, there are no apartments or large man-made structures that obstruct the natural landscape. So, I feel like I am one with nature. Some tourists feel as if they are on the battlefield from 70 years ago, seeing signs warning them to be careful of landmines and thinking that landmines may still be present. It conveys the urgency and vividness of the situation at the time. Although landmines are dangerous, I think the storytelling of the Punch Bowl Trail and its preservation of nature are helpful. Because landmines are present, people are forced to use only the designated trails, which may be protecting the ecosystem.

For example, Course A circles key sites, including the Information Center, Cheongnyongan, Birch Forest, Wausan Observatory, Deodeok Farm, Large Bunker, Jengansa Temple, Oesol Shelter, and Jae-an-Myeon Office, along with a traffic circle and bunkers. Additionally, prominent features, such as the bunkers and the 4th Tunnel, serve as stark reminders of the wartime legacy. This historical context has spurred numerous inquiries from middle and high schools seeking to incorporate history education into outdoor activities [44]. In the DMZ border area, storytelling not only enriches the visitor experience but also underscores the importance of continuous ecosystem preservation. The fusion of distinctive local narratives with dedicated nature conservation efforts has emerged as a key driver for revitalizing walking tourism while disseminating regional identity and promoting the values of peace [17,19].

In short, DMZ Punch Bowl Dulle-Gil offers tourists a unique experience that seamlessly weaves together geography, security, historical memory, and nature conservation. Notably, residents’ direct commentary and guidance vividly capture the immediacy of historical experience, establishing the site as an educational, cultural, and peaceful landmark. Therefore, DMZ Punch Bowl Dulle-Gil is a prime example of a sustainable tourism model that effectively integrates history, security, and ecology elements.

6.2. Land Use Policy Cooperation Fuels Successful Walking Tourism

These stakeholders collaborate through a voluntary cooperation system pivotal to building the Punch Bowl. For instance, the Korea Forest Research Institute and other experts provide advisory support to the private operator. Additionally, the operating committee suggested installing a “Dalmari”, a designated dining area, along with each course. In particular, the Dulle-Gil Council is crucial in conducting safety-related inspections and overseeing necessary repairs. As a result of these cooperative efforts, the number of walking tourists increased from 7713 in 2021 to 10,673 in 2024 [41].

Nevertheless, operational challenges persist, with budgetary constraints posing a significant hurdle to preserving the Dulle-Gil infrastructure. Although the managing corporation receives annual support for operating costs from the Korea Forest Service and the Korea Mountaineering and Trekking Support Center, financial stability remains a concern. The corporation reinvests 5% of its profits from forest food sales, accommodations, and agricultural products into trail maintenance to supplement its budget. However, a nearly 50% reduction in budget allocations has strained its operations, making the management of walking trails challenging.

When we received the budget, we had to mow the grass on the path connecting the forest to the farm road in the summer and repair the trees that had been felled by typhoons, as well as the damaged drainage ditches. However, the budget was cut in 2024, so we received about 90 million won, which is 60% of the budget. To minimize labor costs, only two people work there: me and a female employee. We mowed the grass ourselves and strived to reduce costs. And I do not work during the winter months. The Dulle-Gil remains closed during that time. Our foundation receives 5% of the sales from the sale of forest food, local accommodation, and agricultural products. We also use that money for environmental cleanup activities on the Dulle-Gil.(Director)

Second, cooperation with the military remains a significant challenge. Certain sections of the Dulle-Gil are difficult to connect due to safety and security concerns. According to a local operator

Consultations with the military are not easy, so there are cases where the connection of the courses is not natural. In particular, for the Forest Trail of the Mandae Plain Trail, it is possible to connect the two-kilometer section. However, due to military approval issues, it is necessary to detour to the three-kilometer farm road, which is causing the trail to be cut off.

For instance, the Forest Trail of the Mandae Plain Trail requires a detour via a three-kilometer farm road instead of a direct two-kilometer connection due to military approval issues, which disrupts the trail’s continuity. A system has been implemented to wirelessly report visitor numbers, entry times, and routes to the military base 48 h before, with real-time communication through a messenger app such as KakaoTalk. However, delays and restrictions still occur in some sections. Accordingly, establishing a systematic long-term agreement and management guidelines between the Korea Forest Service and the military is essential.

If the military unit declares that the area is unsuitable for military use, taking a different route would be unnatural and detrimental. Therefore, as a compromise, we must inform the military unit of the number of people entering the area at least 48 h in advance. We share information such as which course, at what time, how many people will depart, and where they will go from one time to another. 13 people, including the commanding officer, the regiment commander, and the platoon commander, share information about the forest trails. Fortunately, the route has become natural because we always keep our promise to the military base, where photography is prohibited. However, there are still some unnatural trails that we have not been allowed to use. An unnatural path means that the path is not smoothly connected. In other words, it means that part of the path is broken or awkwardly connected, making the walking path feel unnatural or uncomfortable. I have suggested it to the Forest Service and informed the military base’s Director.

Third, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted communication, creating significant challenges. Face-to-face meetings with military units, the Korea Forest Service, and local governments became impossible, hindering the consultation process. While introducing a video conferencing system helped mitigate this issue, the experience highlighted the need to institutionalize a flexible and remote consultation framework to ensure smoother coordination during future public health crises.

In conclusion, the DMZ Punch Bowl Dulle-Gil case exemplifies how strategic land use policy coordination and strong public–private cooperation can revitalize walking tourism. Policy coordination between the Korea Forest Service and military units, active resident participation, regular consulting meetings, and a balanced mix of budget support with private resources have collectively transformed DMZ Punch Bowl Dulle-Gil into a sustainable tourist attraction. As a cooperation model that balances the interests of tourists, environmental conservation, and local communities, it is a best practice model that could be replicated in other regions.

6.3. Successful Revitalization of Walking Tourism and Its Economic Impact

Yanggu, designated as one of Korea’s 89 depopulated areas in 2021, is a small town with approximately 23,000 residents, experiencing a steady decline in population over the past decade. Despite these challenges, the DMZ Punch Bowl Dulle-Gil was selected as an exemplary case for the 2021 National Balanced Development Project due to its successful forest trail network, which was achieved through active resident participation and effective management. Due to the town’s size, food and beverage options along the trail remain limited. Initially, pre-packed lunches were provided, but issues such as cold meals or spoilage arose. In response, residents collaborated to develop a new meal delivery system, delivering freshly prepared meals to tourists at designated times and locations along the trail, particularly for groups of 20 or more.

Two farms in Haean-Myeon provide Forest Meals that have signed contracts with the Punch Bowl Dulle-Gil Foundation and operate exclusively at officially approved locations. The price of the Forest Meal is KRW 10,000 (USD 7) per person and has become one of the primary sources of income. Additionally, five percent of the sales revenue is donated to the managing corporation, with the remainder distributed to the residents who provide the meals. As of 2021, 3251 out of 7713 walking tourists opted for the Forest Meal, demonstrating its popularity. Additionally, the sale of local specialties further boosts local revenue. By guiding tourists who have enjoyed Forest Meals to purchase side dishes and specialties at local stores, a sustainable profit model is emerging for the local economy. Therefore, plans are in place to establish a dedicated brand for Forest Meals in the future [41]. Figure 6 shows what is provided for forest meals.

Figure 6.

Paid lunch in the forest for participants on the Yanggu DMZ Punch Bowl Trail (Dulle-Gil). Simple alcoholic beverages and local agricultural products are also available for purchase.

We can see where the tourists are because we are not a self-guided tour for security reasons, so if we tell them the location, we can prepare for them to have a meal at the farmhouse. They usually take one-hour lunch breaks so set lunch next to the valley, as there is a seating area, and the scenery is particularly good in this location. We also made a portable toilet nearby. It takes more than an hour to go out of the Punch Ball forest and have a meal in the city, and the food you bring with you spoils quickly, so you should eat in the forest or elsewhere in the park before or after walking. Apples, Shirigai, and potatoes are sold by mail order when you order them for your forest meals or when you order them from the office, accompanied by the business cards of the farms and farmers. Thanks to this, the sale of agricultural products is also being revitalized. When I explain the forest trails and discuss the characteristics of basins with low nighttime temperatures in summer and autumn and high daytime temperatures, the story of agricultural products arises, and it naturally leads to sales.(Director)

Despite the rich educational and ecological value, strict security measures limit visitor access to the Punch Bowl. Visitors must make online reservations (via Forest Nadeul) at least three days in advance. Unguided personal visits are strictly prohibited due to landmine risks and ongoing military training activities. As a result, all visitors are required to be accompanied by a certified tour guide, precisely three from Yanggu and three from Haean-Myeon, all of whom have completed safety training and obtained certification. The trail accommodates an average of 200 visitors per day and operates only from April to November, in compliance with seasonal and security regulations.

An economic impact study of the Punch Bowl Trail found that most visitors are in their 50s or older, reside in metropolitan areas, and travel an average of 3.5 h primarily for recreation, relaxation, and scenic enjoyment. These visitors usually spend about 4 h on the trails and often extend their trips to explore Yanggu or other regions of Gangwon Province, further contributing to the local economy. The economic ripple effect of walking tourism at the DMZ Punch Bowl Dulle-Gil amounts to annual direct spending of KRW 2.1 billion (approximately USD 1.6 million), total production of KRW 2.8 billion (approximately USD 2.15 million), value-added effects of KRW 1.3 billion (USD 1 million), and the creation of approximately 40 local jobs [19].

The tour guides, who are residents, are paid about 70.000 won a day. They have income because they work on the farm here, and they enjoy hiking, so they are satisfied. Approximately 90 to 100 residents participate in the program each year, typically attending when time is available from their farming work. This arrangement has significantly increased residents’ appreciation and ownership of the Dulle-Gil Trail as a valuable community resource.(Director)

7. Discussion and Conclusions

Tourism plays a vital role in modern society, influencing economic and social dynamics. Economically, tourism has served as a powerful tool for overcoming stagnation in developed countries and fueling rapid growth in developing countries [43]. A notable example is Spain, which overcame industrial decline, triggered by the 1970s oil crisis, increased industrial competition resulting from economic liberalization, and political instability, by rebranding itself as a top resort destination, regaining economic stability through the tourism industry. Socially and culturally, advancements in technology have alleviated the challenges of long-distance travel, allowing for more frequent and diverse tourism experiences. However, tourism activities generate significant social externalities, such as increased carbon dioxide emissions, waste production, and even crime, while fostering cultural exchanges that shape local identities and global perceptions. The environmental effects of unchecked tourism are exemplified by the 2018 crisis in Boracay, Philippines, where severe water pollution and excessive waste production led to a temporary shutdown of the island’s tourism industry, resulting in an estimated loss of Philippine Peso 1.96 billion. This incident underscored the urgent need to mitigate the environmental impact of tourism.

Simultaneously, growing public awareness about environmental degradation has driven a shift toward eco-friendly consumption. A survey indicates that most travelers now favor eco-friendly travel options and sustainable accommodations. Specifically, 74% of the respondents expressed a desire for tourism companies to offer more eco-friendly travel options, and 65% reported feeling optimistic about staying in sustainable accommodations Projections indicate that regions with well-preserved and pristine ecological landscapes will increasingly emerge as focal points for global ecotourism [45]. This shift has spurred interest in walking tourism, a form of slow travel that aligns with sustainable tourism principles by minimizing environmental impacts and enhancing local cultural experiences.

This study explored the conditions for revitalizing rural walking tourism through in-depth interviews with field experts. The analysis identified six themes: eco-friendliness, experiential immersion and sense of place, psychological and physical recovery, memorable tourism experiences through local storytelling, a safe environment, and a robust stakeholder cooperation system for local economic revitalization. These themes were synthesized into a three-pillar framework emphasizing environmental sustainability, emotional immersion, and economic effectiveness. The Gangwon-do DMZ Punch Ball Dulle-Gil case, analyzed through expert discussions, demonstrated how these dimensions transform a historically rich and challenging area into a sustainable tourism destination [43].

The findings extend sustainable tourism frameworks by integrating insights from slow travel, place attachment, and community resilience theories. They demonstrate that walking tourism fulfills the UNWTO’s sustainability pillars and enriches our understanding of how deep emotional and cultural bonds are formed with a destination. Practically, this study underscores the importance of developing tourism infrastructure that integrates eco-friendly practices, robust safety measures, and active stakeholder engagement. These strategies are crucial for policymakers and local communities aiming to revitalize rural economies, particularly in regions facing demographic decline and infrastructure constraints.

7.1. Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to the theoretical discourse on sustainable tourism by extending and refining existing frameworks in several significant ways. First, it integrates slow travel principles, positioning walking tourism as a low-impact, experiential form that aligns closely with the UNWTO’s sustainability pillars. The study illustrates how human-powered movement reduces environmental impact while fostering cultural and ecological awareness by situating walking tourism within the slow travel paradigm. In the DMZ context, slow tourism is an ideal mechanism for minimizing environmental disturbances, managing security-sensitive access, and fostering controlled, small-group interactions. This integration deepens our understanding of how minimal environmental footprints and authentic and intimate interactions with local environments can foster a more sustainable tourism model that prioritizes long-term ecological balance over short-term gains.

Second, the research strengthens and expands theories of place attachment and spatial identity, building on the foundational works of Tuan [25] and Relph [46]. It highlights how immersive, sensory-based experiences, such as those encountered during rural walking tourism, forge deep emotional connections between tourists and destinations. These bonds contribute not only to enhanced tourist satisfaction but also to the long-term preservation of both cultural heritage and natural resources. In this context, the study argues that engaging with local narratives, landscapes, and sensory stimuli creates a unique form of spatial identity, motivating visitors to advocate for preserving these environments. This expanded perspective bridges the gap between individual tourist experiences and broader, community-wide conservation efforts, reinforcing the critical role of emotional and cognitive connections in sustainable tourism.

Third, this study highlights the importance of community resilience and social capital, drawing on the theories of Putnam [47] and Adger [48]. It demonstrates that robust stakeholder cooperation and active local engagement are pivotal for driving sustainable tourism development. The findings reveal that when local communities are integrally involved in tourism initiatives, the resulting collaborative networks catalyze innovation and adaptability in tourism practices. These networks enable communities to overcome socio-economic and environmental challenges by pooling resources, sharing expertise, and developing adaptive strategies that ensure the long-term viability of tourism projects. Furthermore, the study posits that such resilient networks enhance the effectiveness of tourism initiatives and empower local stakeholders, ultimately transforming tourism into a tool for community development and economic revitalization. In the DMZ case, these cooperative mechanisms are particularly shaped by military governance structures and ecological fragility, requiring coordination with actors such as military authorities, conservation agencies, and municipal leaders.