Abstract

Urban parks are important places, reflecting the culture of residential communities. The role of urban parks in providing cultural experiences and creating local cultural value is becoming increasingly prominent. Based on attention restoration theory (ART), this paper uses structural equation modeling (SEM) to verify the relationship between perceived restorativeness and various factors in the sociocultural value of urban parks. The results show that being away, fascination, coherence, and compatibility all have significant positive effects on residents’ aesthetics; being away and fascination have direct positive effects on well-being; and fascination, coherence, and compatibility have direct positive effects on place identity. Therefore, the paper concludes that urban parks play a key role as cultural spaces. A higher level of perceived restorativeness of urban parks helps to enhance the social and cultural value of the area, promote residents’ aesthetics and well-being, improve residents’ sense of local identity, help build community culture, and showcase local residents’ lives.

1. Introduction

In terms of the sustainable development of cities, the impact of public spaces on the health and well-being of residents has received increasing attention [1,2]. Urban green spaces and public recreational areas are important indicators of the quality of urban life and can enhance residents’ well-being. Parks are among the most basic types of urban green space and a vital part of urban public spaces. Urban parks are a central hub of residents’ lives and culture [3], increasingly valued as sites that enable people to connect and share social benefits within their communities [4]. Based on the social functions of such urban parks, studying the cultural formation mechanisms of urban residents’ living space is an important topic in urban research.

The urban natural environment has the function of restoring attention. Attention restoration refers to the process of regaining lost attention in the environment, illuminating the connection between the environment and human health [5,6]. Previous studies have provided a broad evidence base to suggest that contact with nature can bring residents noneconomic benefits, including stress relief, increased positive emotions, and mental health improvement [7,8]. These effects in turn deepen people’s attachment to places [9,10]. Urban parks enhance residents’ health and allow for the nurturing of relationships between people and the land by providing opportunities to access nature. Through explorations of residents and places, perceptions of urban parks are formulated as the basis for local identity, thereby enhancing the value of local cultural assets [11].

Sociocultural value reflects the subjective perceptions and preferences of residents in the environment and constitutes the noneconomic value of ecosystem services [12]. When people reside in a place with a beautiful natural environment and strong cultural atmosphere, they are more likely to feel more relaxed and less fatigued, which in turn affects their mental state and behavior. This process can be understood as the construction of residents’ identities by the environment [13]. In urban green spaces, parks provide accessible cultural ecosystem services and serve as a microcosm of residents’ living culture [14]. By exploring the predictors of urban parks’ sociocultural value, the residential environment and the sustainability of the urban environment can be improved.

Recent studies have promoted the mainstreaming of sociocultural value in forest land development and urban green space management [15,16,17], and the results have demonstrated the feasibility of sociocultural value indicators in evaluating forests, parks, and cultural heritage areas. For example, Granobles Velandia et al. (2024) [15] evaluated the perceived sociocultural value of parks from diverse stakeholder perspectives and found that sociocultural value was influenced by park characteristics. However, evidence on the specific impacts of urban park characteristics on sociocultural value is still lacking. Existing research studies have focused on the evaluation validity of socio-cultural value and have not yet established the structure of the relationship with the specific perceived characteristics of urban parks.

One unexplored aspect is how the perceived restorativeness of urban environments predicts sociocultural value, which is the central issue of this study. This study addresses this research gap by investigating if residents with more positive perceptions of the restorativeness of urban parks are happier, enjoy beauty more, and have a stronger sense of place identity. To this end, we developed a model to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the structural links between attention restoration theory (ART) and sociocultural value concepts. We then used the structural equation modeling (SEM) method to validate the model. The path analysis results demonstrate the link between perceived restorativeness factors (being away, fascination, coherence, and compatibility) and sociocultural value factors (aesthetics, well-being, and place identity). Additionally, we provide evidence for the role of aesthetics in shaping well-being. The research enriches the ART findings and expands the research scope of sociocultural value theory. It is conducted from the perspective of residents, which has the practical implication of helping to elucidate the establishment of human–land relationships.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Definition of the Concepts

2.1.1. ART

ART proposes that attention lost in daily life can be restored through the environment [5]. The interaction between people and places has become the theoretical basis for a growing body of empirical research into individual psychological restorativeness [18]. ART has been used in analyzing a diverse range of empirical contexts to explore the social benefits of natural environments.

Kaplan and Talbot (1983) [19] proposed four dimensions in measuring environmental restorativeness: being away, extent, fascination, and compatibility. Being away refers to getting away from daily life; this requires directing one’s attention toward and immersing oneself in an environment that is different from the usual environment. Extent refers to the size and consistency of the environment into which one can enter and spend time. Fascination refers to whether the environment itself is interesting and engaging. Compatibility refers to the degree to which what the environment provides matches the individual’s expectations and needs [19,20]. Extent can be divided into two sub-components: coherence and scope. Coherence is the perception of the structure of the environment; it is used to describe whether the environment is considered orderly and understandable [21]. Scope refers to an environment’s capacity to provide exploration opportunities [20,22]. As this study focuses on the perception of the environment, we selected the four dimensions of being away, fascination, coherence, and compatibility as the key metrics for determining perceived environmental restorativeness.

2.1.2. Place Identity Theory

Place identity is defined as a combination of feelings about specific physical associations, emphasizing an individual’s perception and understanding of the environment [23]. As an important dimension of place attachment, it is used to explain behavior and attitudes [24]. Place identity theory emerges from the addition being made to identity theory of place as a key part of self-identity [9]. In the group relationships that are formed and fostered in urban places, place identity has a significant impact on neighborhood satisfaction, residential environment satisfaction, group prejudice, etc. [25,26]. In addition, place identity can be deployed as an important concept when implementing practical projects, such as in tourism development and regional governance contexts [27,28,29]. As awareness of the impact of place identity on people’s well-being and local development has grown, the impact of factors such as city size, place quality, and green space on place identity has also been increasingly demonstrated [30,31,32].

In the context of urban renewal, the theoretical exploration of the formation of place identity should consider not only physical elements but also the meaning that people perceive there to be in the pervading social culture of the place [33]. Zheng et al. (2023) [34], for example, examined cultural memory as a predictor of place identity. This study accordingly defines place identity as a reflection of urban social culture, accepting Proshansk’s (1978) [23] definition of place identity as a sense of self-identity formed by an individual through interaction with a specific place.

2.1.3. Sociocultural Value

Sociocultural value is a nonmonetary form of value that people attach to goods or services [35]. Bullock et al. (2018) [36] described sociocultural value as a product of daily life within cultural and social contexts, consisting of a multiplicity of value, including well-being, moral principles, and utilitarian considerations. In the field of ecosystem services, sociocultural value is an evaluation index that can be used to represent the sum of a society’s needs, perceptions, and preferences for ecosystem services [37]. According to this perspective, a “city” can be viewed as an ecosystem, culture (and art) can be conceived as resources, and residents can be construed as stakeholder subjects who drive social change. Here, we define sociocultural value as the emotional, cognitive, and other noneconomic values of people’s activities that occur in their lives or their environments.

Throsby (2001) [38] argued that cultural value consists of four components: aesthetic value, spiritual value, historical value, and social value. Bullock et al. (2018) [36] posited that sociocultural value is a comprehensive concept that expresses the relationship between humans and nature through utility, aesthetics, and ethics. Klamer (2004) stated that social value includes belonging, identity, and social distinction [39]. Drawing from the framework developed by Lampinen et al. (2021) [40], this article measures sociocultural value across the subcategories of well-being, aesthetics, and identity.

2.2. Development of Hypotheses

2.2.1. Perceived Restorativeness and Well-Being

Well-being can be defined according to the values of hedonism and eudaimonism. It pertains not only a person’s emotions (happiness and unhappiness) but also multiple cognitive, social, and affective factors, such as mental health, physical health, social relationships, individual or group behavior, and life satisfaction [41,42]. Well-being is an important aspect in the concept of sociocultural values, covering an individual’s subjective feelings about various aspects of his/her overall life.

The way space is organized and used is closely related to well-being [43]. Perceptions of the environment can reflect, inform, and interact with well-being. Some research has shown that perceived environmental restorativeness, an environmental perception, has a positive impact on well-being [2,8]. For instance, Yusli et al. (2021) [7] showed that being away, fascination, and compatibility, among the various perceived restorativeness factors of natural landscapes, have a significant impact on well-being. This study proposes the following hypotheses based on the findings and theories of the research to date in an effort to reveal the impact of the perceived restorativeness of urban parks on well-being.

H1a.

The influence of being away on well-being is positive and significant.

H1b.

The influence of fascination on well-being is positive and significant.

H1c.

The influence of coherence on well-being is positive and significant.

H1d.

The influence of compatibility on well-being is positive and significant.

2.2.2. Perceived Restorativeness and Aesthetics

Aesthetics, in this context, refers to people’s emotional judgments of sensory data, including personal preferences, evaluations, and feelings [44]. Chatterjee (2014) [45] defined aesthetics as the perception of, production of, and reaction to art, as well as the feelings elicited through interaction with objects/environments. Aesthetics is an important factor of sociocultural value used to evaluate the composition and quality of the environment [46], because it involves people’s intuitive feelings and evaluations of the environment.

In the context of urban spaces, aesthetics is a sustainable and unconscious source of pleasure [47]. A relaxing environment, such as a well-manicured lawn, a trickling stream, and the melodious singing of birds in the forest, is often beautiful. A study of urban green spaces by Deng et al. (2020) [48] showed a positive relationship between restorativeness and aesthetic preferences. The existing evidence suggests that multiple dimensions of perceived restorativeness can separately influence aesthetic preference. For example, ref. [49] revealed that being away has a significant impact on preferences in urban environments. Moreover, Van Geert and Wagemans (2021) [50] demonstrated that aesthetic preference increases with visual fascination. Mutlu Danaci and Kiran (2020) [51] verified that the compatibility of urban facilities has a positive impact on aesthetic preferences. Finally, Jiang et al. (2016) [52] showed that people have an aesthetic preference for unified and orderly visual designs. According to the existing evidence, we hypothesize that perceived restorativeness factors have a positive impact on perceived aesthetics in the context of urban parks.

H2a.

The influence of being away on perceived aesthetics is positive and significant.

H2b.

The influence of fascination on perceived aesthetics is positive and significant.

H2c.

The influence of coherence on perceived aesthetics is positive and significant.

H2d.

The influence of compatibility on perceived aesthetics is positive and significant.

2.2.3. Perceived Restorativeness and Place Identity

The characteristics or attributes of a place affect people’s sense of identity. From the perspective of sociocultural value, place identity can reveal the stage effects of the interaction between people and the environment. Mao et al. (2022) [32] argued that community identity increases in strength and resonance with the perception of residential quality. In particular, as an important aspect of assessing the quality of the natural residential environment, perceived restorativeness needs to be further explored in relation to place identity. Korpela and Hartig (1996) [53] examined environmental preference as a characteristic of place identity and showed that the perceived restorativeness factors of being away, fascination, coherence, and compatibility differed in different environments. Hu et al. (2022) [18] verified that being away and compatibility have a positive impact on the sense of belonging to a region. The results of [54] showed that perceived plasticity and perceived charm among the perceived restoration factors had a positive effect on place identity. Based on these former research findings, this study posits the following hypotheses:

H3a.

The influence of being away on place identity is positive and significant.

H3b.

The influence of fascination on place identity is positive and significant.

H3c.

The influence of coherence on place identity is positive and significant.

H3d.

The influence of compatibility on place identity is positive and significant.

2.2.4. Well-Being and Place Identity

Well-being can explain how the environment affects place identity. Wester-Herber (2004) [55] revealed that an increase in happiness helps strengthen the connection between people and the environment, affecting their cognition and behavior. When residents positively evaluate their living environment, they form a connection with the place’s culture, and their behavior is influenced by local cultural norms. Moreover, Loureiro (2014) [56] provided empirical evidence that pleasant arousal (such as happiness and excitation) positively affects individuals’ attachment to and memory for places (two aspects of place identity). Lv and Xie (2017) [57] verified that well-being has a positive impact on place identity. Based on these findings, this study posits the following hypothesis:

H4.

The influence of well-being on identity is positive and significant.

2.2.5. Aesthetics and Well-Being

According to Dewey (1934) [58], aesthetic experience can boost personal and social well-being, but few empirical research studies have tested this hypothesis. In terms of the connection between aesthetics and neurology, there is evidence that aesthetic experience modulates cognition and emotion [59,60]. As positive emotions are an important part of well-being, the evidence that art and aesthetic experiences have a positive impact on mental health suggests that environments with high aesthetic value will increase well-being [46]. The results of the study [61] showed that workplace design aesthetics can promote the well-being of hotel employees. However, the direct relationship between aesthetics and well-being needs to be further explored [62]. Based on the scholarly discussion that has taken place thus far, we posit the following hypothesis:

H5.

The influence of perceived aesthetics on well-being is positive and significant.

2.2.6. Aesthetics and Place Identity

Urban aesthetics play an important role in shaping place identity and local culture and in facilitating social transformation [63]. Aesthetics is an important factor when implementing people-oriented urban planning policies. If people live in a beautiful place, they love it and develop a strong sense of belonging. According to Fingerhut et al. (2021) [63], identity can be constructed through preferences for culture and art, with identity changing with aesthetics. Findings from a mixed study suggest that street aesthetics contribute to place identity as a sign that residents care about their neighborhood [64]. In addition, Yang et al. (2022) [65] provided empirical evidence that aesthetics can predict tourists’ cultural identification with cultural heritage areas. Based on the discussion of the relationship between aesthetics and place identity, we propose the following hypothesis:

H6.

The influence of perceived aesthetics on identity is positive and significant.

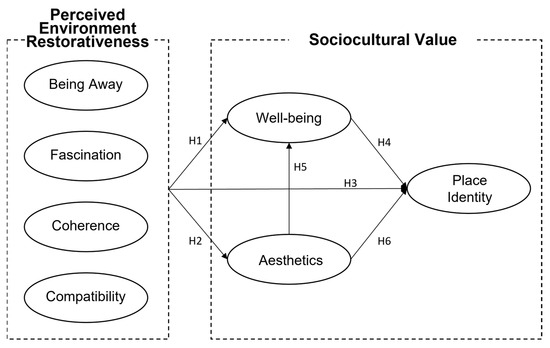

On the basis of the six hypotheses proposed, this study developed a conceptual model, positioning residents as the main subjects to explore how residents’ perceived restorativeness of park environments relate to sociocultural value. We used the framework as a measurement model to study the nature and significance of the relationships between the seven variables. The conceptual model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model for the examination of relationships between the variables.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Measures

The questionnaire used to collect the data consisted of three sections. The first collected data on the demographic characteristics of the participants. The second included 21 items pertaining to the four dimensions of perceived restorativeness (being away, fascination, coherence, and compatibility), based on the Perceived Restorativeness Scale (PRS) developed by Hartig et al. (1997) [22], combined with key aspects of other related research [66,67], from which the importance of measuring the perceived resilience of the environment was derived. The third part covered three factors of sociocultural value (well-being, aesthetic preference, and place identity). Well-being was measured via five items adapted from the Perceived Well-being Scale developed by Ryff (1989) [68] and the ONS (UK Office of National Statistics), consisting of four indicators: happiness, life satisfaction, positive relations with others, and self-acceptance. Aesthetics was measured via six items based on the metrics used by Lampinen et al. (2021) [40], including three specific indicators: beauty, cleanliness, and preference. Place identity was measured via six items adopted by former researchers, including four specific indicators: attachment, sense of identity, belonging, and special connection. All items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

3.2. Data Collection

The focal site selected for this study was Labor Park, located in the center of Dalian City, Liaoning Province, China (see Figure 2). Built in 1898, it has a long history. Labor Park covers a large area; it provides a comprehensive range of facilities, consists of rich natural scenery, hosts animal ecosystems, comprises a complete infrastructure, and includes transportation facilities. The large football-shaped building in the park is a landmark building of Dalian City. Labor Park is representative of the culture of Dalian City, seeking to meet residents’ needs for entertainment, leisure, sports facilities, and so on. It is the most popular park in the local area. Therefore, the Dalian Labor Park is considered to have both natural and cultural elements providing a restorative environment, which makes it a good location for exploring the relationship between perceived environmental restorativeness and sociocultural value.

Figure 2.

Aerial view of Labor Park in Dalian City.

The opening section of the questionnaire outlined the concept of urban parks for the respondents and asked them to recall their experiences of visiting Labor Park in the past year. The data were gathered via an online survey using a convenience sampling method. After eliminating invalid answers, a total of 228 valid questionnaires were collected.

The respondents were all residents of Dalian City. In terms of gender distribution, 46.5% were male and 53.5% were female. Almost half (46.1%) of the respondents were aged 20–29, 43% were 30–59, and a minimal number were aged 60 and over (2.6%). The income range for most participants (35.5%) was RMB 5000 (USD 700)–RMB 10,000 (USD 1400) per month. In terms of frequency of visits, a total of 87.4% of respondents reported that they had visited Labor Park more than three times in the past year. The top three reasons the participants gave for visiting cultural parks were to engage in daily leisure activities (38.2%), to relieve stress (17.7%), and to go on dates (14.0%). Overall, the sample used for analysis has a balanced gender and age distribution, demonstrates diverse educational and occupational backgrounds, and is consistent with the law of population distribution. The visit frequency, purpose, and companion data reflect the sample’s closeness to the park and the diverse functions. The result of demographic characteristics and visit features of sample are showed in Table S1.

3.3. Data Analysis Methods

This study used the SEM method to test the proposed research model. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA), reliability analysis, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), confirmatory validity analysis, and SEM were conducted in sequence. EFA was conducted using SPSS 26 to verify the intrinsic validity and reliability of the measurement scales. CFA and SEM were conducted using AMOS 26, which was employed to check the external validity of the measurement scales and the fit of the research model. Finally, the hypotheses were accepted or rejected based on the obtained path analysis results. The results of these analyses are presented in the following sections.

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity of the Measurement Model

In the EFA, principal component analysis was performed using the varimax orthogonal rotation method based on an E value > 1. Intrinsic validity was ensured after excluding items BA1, FA2, CH5, AE6, and PI1 with factor loading values below 0.5. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value was 0.901 (>0.5), making it suitable for factor analysis. Bartlett’s test of sphericity showed that the results were highly significant, with a significance probability of x2 = 3694.375 (p = 0.000, <0.05). The cumulative explanatory power of each factor was 64.785%.

The reliability analysis results showed that the Cronbach’s α coefficient of each factor was above 0.7. This indicates that the reliability of the set of measurement items was good and that the internal consistency of the variables was ensured. The results of EFA and Cronbach’s α coefficient are available in Table S2.

4.2. Measurement Model

CFA confirmed the validity of the proposed measurement model. The AVE values used to determine internal consistency were all greater than the standard value of 0.5, and the composite reliability (CR) values were all above 0.7. Thus, the reliability and conceptual validity of each factor were confirmed. In the evaluation of convergent validity, all the loading values were found to be above 0.5. The R-value was greater than 1.96 and significant, with a p-value < 0.01, indicating that the factor had internal consistency. Therefore, central validity was secured for all latent variables with desirable reference values. The model’s fit was thus considered acceptable, with indices that meet the recommended thresholds (χ2/df = 1.356; CFI = 0.950; NFI = 0.936; TLI = 0.944; RMSEA = 0.040) (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Results of the measurement model.

Discriminant validity analysis was conducted to determine whether there were multicollinearity issues among variables. As shown in Table 2, the square root of the AVE index was higher than the inherent variance, so it was determined that the latent variables were distinct structures in this model and there was no multicollinearity problem [69,70].

Table 2.

Results of the discriminant validity.

4.3. Structural Model Results

We conducted an analysis of the subsequent structural equations based on the analysis of the measurement model’s validity. The objective here was to validate the structural model and test the research hypotheses. A satisfactory adjustment was found for the structural model (χ2/df = 1.430; CFI = 0.934; NFI = 0.811; TLI = 0.927; RMSEA = 0.044).

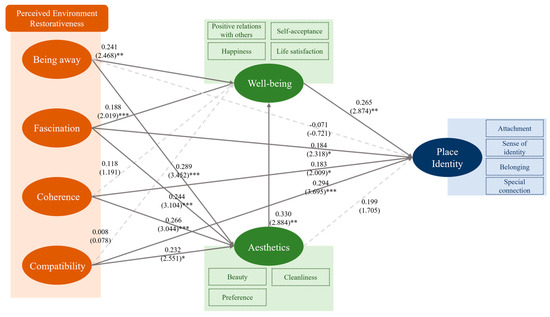

The relationships between the factors of perceived environmental restorativeness, such as being away (β = 0.241, p < 0.05), fascination (β = 0.181, p < 0.05), and well-being, were found to be statistically significant and positive (+). Therefore, H1a and H1b were accepted, and H1c and H1d were rejected. In terms of H2, all the perceived environmental restorativeness factors, namely, being away (β = 0.289, p < 0.001), fascination (β = 0.244, p < 0.01), coherence (β = 0.266, p < 0.01), and compatibility (β = 0.232, p < 0.05), were found to have a statistically significant positive (+) effect on aesthetics. In terms of H3, the perceived environmental restorativeness factors fascination (β = 0.183, p < 0.05), coherence (β = 0.216, p < 0.05), and compatibility (β = 0.407, p < 0.001) positively impacted place identity (H3b, H3c, and H3d were therefore accepted). As predicted, well-being had a positive impact on place identity (H4) (β = 0.265, p < 0.01), and aesthetics had a positive impact on well-being (H5) (β = 0.330, p < 0.01). Hypothesis H6, which assumed a positive relationship between aesthetics and place identity, was rejected (β = 0.199, p > 0.05). The predicted relationships, path estimates, and outcomes of the hypothesis tests are shown in Table 3 and Figure 3.

Table 3.

Results of structural model analyses.

Figure 3.

Results summary of measurement model. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

5. Discussion

This study examined the relationship between the perceived restorativeness and sociocultural value of urban parks. Overall, the findings support suggestions proposed in the environmental aesthetics and well-being literature, generally showing that residents’ perceptions of environmental restorativeness can enhance their well-being and aesthetic perceptions [8,48] and place identity [32]. Being away and fascination were found to be powerful aspects that stimulate well-being, similar to a previous finding [7]. According to Baklien et al. (2015) [71], being close to nature and away from the hustle and bustle of life enhances people’s relationships, happiness, and mental health. Fascinating environments can provide a sense of well-being, generating positive emotions and self-identity associated with the place [72]. However, coherence and compatibility did not show a significant effect on well-being. This may be related to cultural factors; that is, residents living here may pay more attention to the direct affective impact of the experience and be relatively insensitive to the consistency of the visual or functional environment or whether the surrounding environment matches their needs.

Previous studies have all found being away, fascination, coherence, and compatibility to have a significant positive impact on perceived aesthetics [49,50,51,52]. According to Abkar (2011) [49], people mainly visit urban parks for experiences that differ from their daily lives. The distance from daily life provides novel experiences and affects people’s aesthetic preferences [56]. The intuitive sense of novelty comes from the visual appeal, one source of aesthetics [44]. People tend to find harmony and unity beautiful, and have a negative view of lack of coherence or order [52]. According to Berghman and Hekkert (2017) [73], ordered, coherent perceptual input promotes smooth, efficient processing and increases aesthetic pleasure.

The results of the hypothesis tests showed that the fascination, coherence, and compatibility factors of perceived restorativeness had a significant and positive impact on place identity, which is similar to the findings previous studies [53,54]. Jorgensen et al. (2007) [64] claimed that a coherent and compatible landscape reflects a caring community and helps to establish connections between individuals and places, thereby influencing individuals’ identification with the place. In addition, when people are fascinated with an environment, they develop an emotional bond with and unique memories of the place. They tend to pay attention to local issues and to take positive actions [74]. Being away does not directly affect place identity but can play a role by shaping pathways to well-being. Moreover, we provided evidence consistent with existing research on the relationship between well-being and place identity [56,57]. That is, people who are satisfied with the environment feel a greater sense of belonging. In this study, there is no evidence to suggest there is a significant effect of aesthetics on place identity. Therefore, the notion that people with stronger perceptions of beauty are likely to identify more with the city was not supported [63].

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

Our study enriches theoretical work in environmental studies by integrating ART with sociocultural value theory to develop a conceptual framework that can be used to inform a measurement model. This is the first study to establish the structural relationship between environmental restorativeness and sociocultural value. The results show that well-being and aesthetics, as important factors of sociocultural values, are important in shaping place identity. Although previous research has demonstrated considerable interest in environmental aesthetics, quantitative evidence is lacking. This study considers perceived environmental restorativeness a multidimensional variable and demonstrates a strong relationship between it and aesthetics in urban green spaces. Moreover, the results enrich the evidence on the impact of well-being on place identity. Despite these significant findings, the relationships between aesthetics, well-being, and identity require further research.

5.2. Practical Implications

Our findings have practical implications for the design of urban public spaces. Urban parks, as accessible urban public green spaces, can provide sociocultural value through perceived restorativeness. First, residents’ psychological relaxation and aesthetic feeling can be enhanced by the restorative features of the environment (such as spacious green ground, staggered layers of plants, water views, etc.). The diversity of vegetation can shape the perceived environmental restorativeness. Tall trees can be used to establish a green barrier that isolates traffic noise and urban interference and enhances the tranquility and “sense of escape” of the environment. The ornamental plants can provide a visual “fascination” and help to enhance the perceived difference between parks and daily urban spaces, thereby improving the attractiveness and aesthetic value of the environment. Second, planners should focus on coordinating cultural facilities and natural landscapes, entirely use local historical and cultural resources, and create cultural landscapes with humanistic charm through art installations, cultural activity spaces, and landmark buildings that reflect local characteristics. It is important to ensure overall coordination and visual consistency, such as the arrangement of plants, the matching of building materials and facility colors, and the creation of a unified and comfortable landscape atmosphere. In addition, the versatility and flexibility of the park space are also important. The diverse spaces and facilities should satisfy various leisure activities, enhance residents’ sense of social belonging and cultural participation through health courses and community festivals, and further stimulate identification with and emotional investment in public spaces.

5.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

First, because we studied a single urban park and we did not develop a framework for differentiating between different types of urban parks, the results are not generalizable to all urban parks in all cultural or national contexts. Second, the resident attributes were not designed in advance, which may weaken the explanatory power. Subsequent research should include factors such as the distance from the residence of the visitors. In addition, the empirical data were obtained from self-reports and thus possibly suffered from subjectivity and low representativeness, potentially compromising their validity. Therefore, future studies should develop a typology of the various types of urban parks and collect data from more diverse and representative samples. Ongoing research should also be conducted to explore the intensity and direction of the impact of specific environmental factors, especially cultural characteristics, on perceived environmental restorativeness through experimental or comparative methods.

6. Conclusions

We defined perceived environmental restorativeness as a multidimensional variable in the context of urban parks and explored the impact of each dimension on sociocultural value factors. The results showed that an urban park can be an effective driving force in creating and strengthening sociocultural value and a vital component of an urban development plan geared toward supporting residents’ health and well-being.

Our study provides a new perspective that encourages urban planners to utilize cultural resources to develop urban public green spaces with environmental restorativeness. To achieve the people-oriented planning goal, it is recommended that well-being, aesthetic experience, and place identity be included in the urban park planning indicators. The design of urban parks should focus on creating an environment with restorative characteristics to enhance sociocultural values. The restorative perception of the urban park environment can be enhanced by diversifying vegetation types, building a landscape that coordinates nature and humanities based on local history and culture, and expanding cultural activities, thus promoting the harmonious coexistence of people and land and sustainable development of urban public green spaces.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land14051097/s1, Table S1: Demographic characteristics and visit features of sample. Table S2: Results of EFA and Cronbach’s α coefficient.

Author Contributions

Formal analysis, J.G.; investigation, J.G.; data curation, J.G.; writing—original draft preparation, J.G.; writing—review and editing, H.K.; supervision, H.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interest or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this study.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ART | Attention Restoration Theory |

| PRS | Perceived restorativeness scale |

| BA | Being away |

| FA | Fascination |

| CH | Coherence |

| CP | Compatibility |

| WB | Well-being |

| AE | Aesthetics |

| PI | Place Identity |

| ONS | UK Office of National Statistics |

| EFA | Exploratory factor analysis |

| CFA | Confirmatory factorial analysis |

| KMO | Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin |

| CR | Composite reliability |

| AVE | Average Variance Extraction |

| CFI | Comparative fit index |

| NFI | Normed Fit Index |

| TLI | Tucker-Lewis Index |

| RMSEA | Root-mean-square error of approximation |

References

- Altuğ Turan, İ.; Malkoç True, E. The perception of public space of the elderly after social isolation and its effect on health. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 101884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.-G.; Kim, J.-G.; Park, B.-J.; Shin, W.S. Effect of Forest Users’ Stress on Perceived Restorativeness, Forest Recreation Motivation, and Mental Well-Being during COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbluth, A.; Ropert, T.; Rivera, V.; Villalobos-Morgado, M.; Molina, Y.; Fernández, I.C. Between Struggle, Forgetfulness, and Placemaking: Meanings and Practices among Social Groups in a Metropolitan Urban Park. Land 2024, 13, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, P.A.; Vázquez, A.M. Between Planning and Heritage: Cultural Parks and National Heritage Areas. Eur. Spat. Res. Policy 2015, 21, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The Restorative Benefits of Nature: Toward an Integrative Framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.; Kaplan, R. The Visual Environment: Public Participation in Design and Planning. J. Soc. Issues 1989, 45, 59–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusli, N.A.N.M.; Roslan, S.; Zaremohzzabieh, Z.; Ghiami, Z.; Ahmad, N. Role of Restorativeness in Improving the Psychological Well-Being of University Students. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 646329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Y.; Ma, J. From Nature Experience to Visitors’ pro-Environmental Behavior: The Role of Perceived Restorativeness and Well-Being. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 32, 861–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauge, Å.L. Identity and Place: A Critical Comparison of Three Identity Theories. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2007, 50, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Vaske, J.J. The Measurement of Place Attachment: Validity and Generalizability of a Psychometric Approach. For. Sci. 2003, 49, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svendsen, E.S.; Campbell, L.K.; McMillen, H.L. Stories, Shrines, and Symbols: Recognizing Psycho-Social-Spiritual Benefits of Urban Parks and Natural Areas. J. Ethnobiol. 2016, 36, 881–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breyne, J.; Dufrêne, M.; Maréchal, K. How Integrating “socio-Cultural Values” into Ecosystem Services Evaluations Can Give Meaning to Value Indicators. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 49, 101278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horlings, L.G. Values in Place; A Value-Oriented Approach toward Sustainable Place-Shaping. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2015, 2, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, S.; Fu, J.; Rong, X.; Dai, L. Users’ Views on Cultural Ecosystem Services of Urban Parks: An Importance-Performance Analysis of a Case in Beijing, China. Anthropocene 2022, 37, 100323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granobles Velandia, F.A.; Trilleras Motha, J.M.; Romero-Duque, L.P.; Quijas, S. Understanding the Sociocultural Valuation of Ecosystem Services in Urban Parks: A Colombian Study Case. Urban Ecosyst. 2024, 27, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Luo, S.; Furuya, K.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.; Li, H.; Chen, J. The Restorative Potential of Green Cultural Heritage: Exploring Cultural Ecosystem Services’ Impact on Stress Reduction and Attention Restoration. Forests 2023, 14, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangas, K.; Brown, G.; Kivinen, M.; Tolvanen, A.; Tuulentie, S.; Karhu, J.; Markovaara-Koivisto, M.; Eilu, P.; Tarvainen, O.; Similä, J.; et al. Land Use Synergies and Conflicts Identification in the Framework of Compatibility Analyses and Spatial Assessment of Ecological, Socio-Cultural and Economic Values. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 316, 115174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Huang, S.; Chen, G.; Hua, F. The Effects of Perceived Destination Restorative Qualities on Tourists’ Self-Identity: A Tale of Two Destinations. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2022, 25, 100724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.; Talbot, J.F. Psychological Benefits of a Wilderness Experience. In Behavior and the Natural Environment; Altman, I., Wohlwill, J.F., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1983; pp. 163–203. ISBN 978-1-4613-3541-2. [Google Scholar]

- Menardo, E.; Scarpanti, D.; Pasini, M.; Brondino, M. Usability of Virtual Environment for Emotional Well-Being. In Proceedings of the Methodologies and Intelligent Systems for Technology Enhanced Learning, 9th International Conference, Ávila, Spain, 26–28 June 2019; pp. 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauru, K.; Lehvävirta, S.; Korpela, K.; Kotze, D.J. Closure of View to the Urban Matrix Has Positive Effects on Perceived Restorativeness in Urban Forests in Helsinki, Finland. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 107, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Korpela, K.; Evans, G.W.; Gärling, T. A Measure of Restorative Quality in Environments. Scand. Hous. Plan. Res. 1997, 14, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proshansky, H.M. The City and Self-Identity. Environ. Behav. 1978, 10, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine-Wright, P. Rethinking NIMBYism: The Role of place attachment and Place Identity in explaining Place-Protective Action. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 19, 393–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, F.; Palma-Oliveira, J.-M. Urban Neighbourhoods and Intergroup Relations: The Importance of Place Identity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleury-Bahi, G.; Félonneau, M.-L.; Marchand, D. Processes of Place Identification and Residential Satisfaction. Environ. Behav. 2008, 40, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Lin, Z.; Vojnovic, I.; Qi, J.; Wu, R.; Xie, D. Social Environments Still Matter: The Role of Physical and Social Environments in Place Attachment in a Transitional City, Guangzhou, China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 232, 104680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.; Chen, N.; Lee, J. The Role of Place Attachment in Tourism Research. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Yan, S.; Strijker, D.; Wu, Q.; Chen, W.; Ma, Z. The Influence of Place Identity on Perceptions of Landscape Change: Exploring Evidence from Rural Land Consolidation Projects in Eastern China. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casakin, H.; Hernández, B.; Ruiz, C. Place Attachment and Place Identity in Israeli Cities: The Influence of City Size. Cities 2015, 42, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, M.I.; Hedayati Marzbali, M.; Saad, S.N. Mediating Role of Place Identity in the Relationship between Place Quality and User Satisfaction in Waterfronts: A Case Study of Penang, Malaysia. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2022, 15, 130–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Peng, C.; Liang, Y.; Yuan, G.; Ma, J.; Bonaiuto, M. The Relationship Between Perceived Residential Environment Quality (PREQ) and Community Identity: Flow and Social Capital as Mediators. Soc. Indic. Res. 2022, 163, 771–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujang, N.; Zakariya, K. The Notion of Place, Place Meaning and Identity in Urban Regeneration. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 170, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Zhang, S.; Liang, J.; Chen, Y.; Ye, W. The Impact of Cultural Memory and Cultural Identity in the Brand Value of Agricultural Heritage: A Moderated Mediation Model. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iniesta-Arandia, I.; García-Llorente, M.; Aguilera, P.A.; Montes, C.; Martín-López, B. Socio-Cultural Valuation of Ecosystem Services: Uncovering the Links between Values, Drivers of Change, and Human Well-Being. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 108, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, C.; Joyce, D.; Collier, M. An Exploration of the Relationships between Cultural Ecosystem Services, Socio-Cultural Values and Well-Being. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 31, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, S.; Teng, J. Ecosystem Services as a Stakeholder-Driven Concept for Conservation Science. Conserv. Biol. 2010, 24, 907–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throsby, C.D. Economics and Culture; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, V.K.R.V.; Walton, M. (Eds.) Culture and Public Action; Stanford Social Sciences [u.a.]: Stanford, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lampinen, J.; Tuomi, M.; Fischer, L.K.; Neuenkamp, L.; Alday, J.G.; Bucharova, A.; Cancellieri, L.; Casado-Arzuaga, I.; Čeplová, N.; Cerveró, L.; et al. Acceptance of Near-Natural Greenspace Management Relates to Ecological and Socio-Cultural Assigned Values among European Urbanites. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2021, 50, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekhili, S.; Hallem, Y. An Examination of the Relationship between Co-Creation and Well-Being: An Application in the Case of Tourism. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; GRIFFIN, S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Azcárraga, C.; Diaz, D.; Zambrano, L. Characteristics of Urban Parks and Their Relation to User Well-Being. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 189, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, T. Bridging the Arts and Sciences: A Framework for the Psychology of Aesthetics. Leonardo 2006, 39, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A. The Aesthetic Brain: How We Evolved to Desire Beauty and Enjoy Art; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Galindo, M.P.G.; Rodríguez, J.A.C. Environmental aesthetics and psychological wellbeing: Relationships between preference judgements for urban landscapes and other relevant affective responses. Psychol. Spain 2000, 4, 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S. The Role of Natural Environment Aesthetics in the Restorative Experience. In Managing Urban and High-Use Recreation Settings; Forest Service: St Pual, MN, USA, 1993; pp. 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, L.; Luo, H.; Ma, J.; Huang, Z.; Sun, L.-X.; Jiang, M.-Y.; Zhu, C.-Y.; Li, X. Effects of Integration between Visual Stimuli and Auditory Stimuli on Restorative Potential and Aesthetic Preference in Urban Green Spaces. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 53, 126702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abkar, M.; Kamal, M.; Maulan, S.; Mariapan, M.; Davoodi, S.R. Relationship between the Preference and Perceived Restorative Potential of Urban Landscapes. HortTechnology 2011, 21, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Geert, E.; Wagemans, J. Order, Complexity, and Aesthetic Preferences for Neatly Organized Compositions. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2021, 15, 484–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutlu Danaci, H.; Kiran, G. Examining the Factor of Color on Street Facades in Context of the Perception of Urban Aesthetics: Example of Antalya. Int. J. Curric. Instr. 2020, 12, 222–232. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.; Wang, W.; Tan, B.C.Y.; Yu, J. The Determinants and Impacts of Aesthetics in Users’ First Interaction with Websites. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2016, 33, 229–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, K.; Hartig, T. Restorative qualities of favorite places. J. Environ. Psychol. 1996, 16, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Guo, Y.; Han, X. The Relationship Research between Restorative Perception, Local Attachment and Environmental Responsible Behavior of Urban Park Recreationists. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wester-Herber, M. Underlying Concerns in Land-Use Conflicts—The Role of Place-Identity in Risk Perception. Environ. Sci. Policy 2004, 7, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C. The Role of the Rural Tourism Experience Economy in Place Attachment and Behavioral Intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 40, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q.; Xie, X. Community Involvement and Place Identity: The Role of Perceived Values, Perceived Fairness, and Subjective Well-Being. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 951–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. Having an Experience. In Art as Experience; G. P. Patnum’s Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Leder, H.; Belke, B.; Oeberst, A.; Augustin, D. A Model of Aesthetic Appreciation and Aesthetic Judgments. Br. J. Psychol. 2004, 95, 489–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelowski, M.; Markey, P.S.; Forster, M.; Gerger, G.; Leder, H. Move Me, Astonish Me… Delight My Eyes and Brain: The Vienna Integrated Model of Top-down and Bottom-up Processes in Art Perception (VIMAP) and Corresponding Affective, Evaluative, and Neurophysiological Correlates. Phys. Life Rev. 2017, 21, 80–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillova, K.; Fu, X.; Kucukusta, D. Workplace Design and Well-Being: Aesthetic Perceptions of Hotel Employees. Serv. Ind. J. 2020, 40, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastandrea, S.; Fagioli, S.; Biasi, V. Art and Psychological Well-Being: Linking the Brain to the Aesthetic Emotion. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fingerhut, J.; Gomez-Lavin, J.; Winklmayr, C.; Prinz, J.J. The Aesthetic Self. The Importance of Aesthetic Taste in Music and Art for Our Perceived Identity. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 577703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, A.; Hitchmough, J.; Dunnett, N. Woodland as a Setting for Housing-Appreciation and Fear and the Contribution to Residential Satisfaction and Place Identity in Warrington New Town, UK. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 79, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Chen, Q.; Huang, X.; Xie, M.; Guo, Q. How Do Aesthetics and Tourist Involvement Influence Cultural Identity in Heritage Tourism? The Mediating Role of Mental Experience. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 990030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laumann, K.; Gärling, T.; Stormark, K.M. Rating scale measures of restorative components of environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.-L.; Shen, C.-C. The Sustainable Development of Organic Agriculture: The Role of Wellness Tourism and Environmental Restorative Perception. Agriculture 2022, 12, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness Is Everything, or Is It? Explorations on the Meaning of Psychological Well-Being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; David, F.L. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Baklien, B.; Ytterhus, B.; Bongaardt, R. When Everyday Life Becomes a Storm on the Horizon: Families’ Experiences of Good Mental Health While Hiking in Nature. Anthropol. Med. 2016, 23, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-J. Destination Fascination, Well-Being, and the Reasonable Person Model of Behavioural Intention in Heritage Tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 27, 288–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghman, M.; Hekkert, P. Towards a Unified Model of Aesthetic Pleasure in Design. New Ideas Psychol. 2017, 47, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezapouraghdam, H.; Akhshik, A.; Strzelecka, M.; Roudi, S.; Ramkissoon, H. Fascination, Place Attachment, and Environmental Stewardship in Cultural Tourism Destinations. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2024. advanced online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).