Regeneration of Military Brownfield Sites: A Possible Tool for Mitigating Urban Sprawl?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

- What is the size of the site in question?

- What was its former function? What type of Soviet facility operated on the site and what was its purpose?

- What was the condition of the site following the departure of the Soviet forces?

- When did the rehabilitation of the area begin (if it took place at all), who was/were the main stakeholder(s) behind the project (state, private company, etc.), and how successful was it?

- Who acquired ownership of the area following its rehabilitation? What types of investors arrived in the area?

- What concepts were proposed for the utilization of the site? Why was the final project implemented instead of other alternatives? What sources of funding were used for the redevelopment?

- What has been the main impact of the redevelopment regarding the wider development of the city, and what potential effects it may have in the future?

- How well does the newly established function resulting from the redevelopment align with the social and economic character of the city?

- Did the development increase or decrease the level of built-up areas compared to the previous conditions?

- How did locals perceive the redevelopment, both residents living in the immediate vicinity and the city as a whole? Did the regeneration have any positive or negative impact on the surrounding areas?

4. Results

4.1. Intact Sites

4.2. Redeveloped Sites in the Compact City (‘Compact’)

“The site with the former Soviet barracks gives our district a significant development potential, as it lies along the main transit road leading to the suburbs. This is probably the reason why potential developers interested in the area appeared soon after the political changes”.(Respondent 3)

4.3. Redeveloped Sites Outside the Compact City (‘Peripheral’)

“The local government has been planning for the area a sub-center function for a long time to relieve the burden on the city center and provide services for the outer parts of the city. There are still 30 hectares of unused land available in the area, for which several plans have been made. The latest plan envisaged an urban sub-center with mixed-functions and good public transport connections with the city center, and a bike path”.(Respondent 1)

4.4. Generations of Former Soviet Military Sites

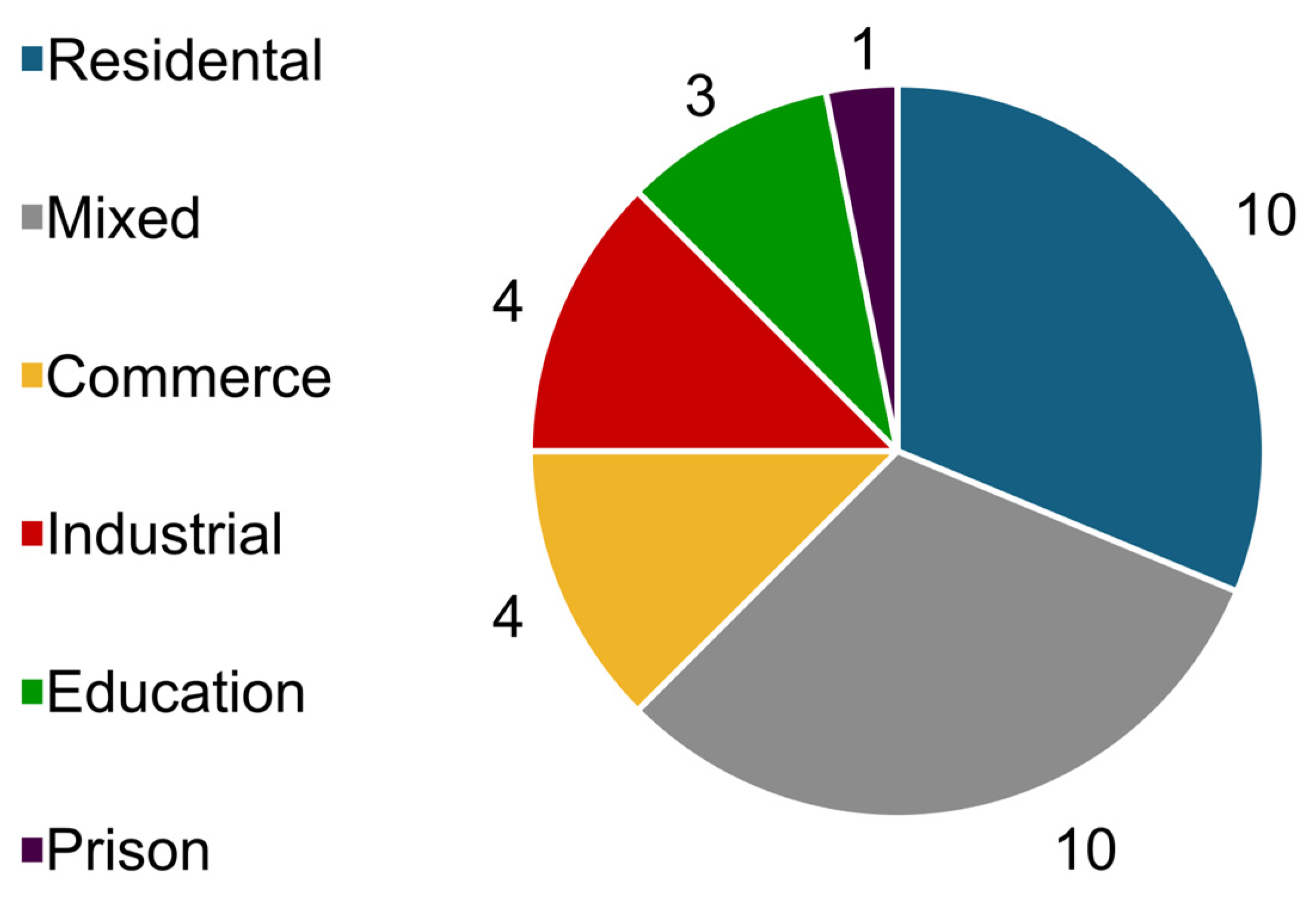

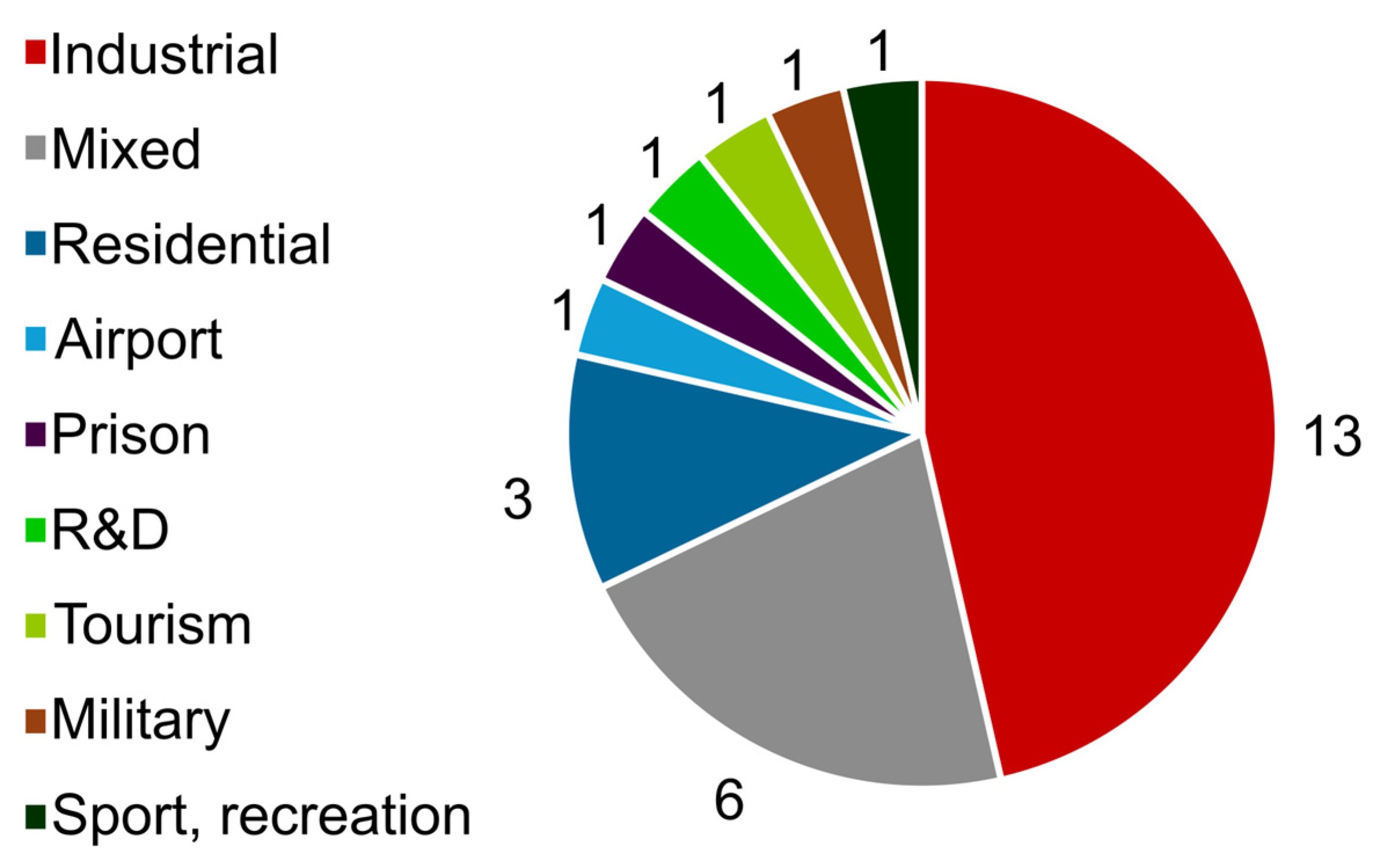

4.5. Functions of the Reuse of Soviet Military Brownfields

“The main building of the barracks stood empty for a long time, because the municipality did not have sufficient resources for renovation. Situation changed when the county level institution of the national archives was removed there. Then the renovation was carried out from public money and the building got a new function”.(Respondent 8)

5. Discussion and Conclusions

“Local governments’ budgets are getting smaller and smaller due to government restrictions. They are unable to compete with real estate speculators. Local governments can only implement smaller developments from their own resources (e.g., infrastructure development). The best chance is if the city successfully applies for state or EU funds, which may limit the development that can be carried out, but at least the area can be recycled”.(Respondent 1)

“As a significant part of the area became privatized the possibility for the municipality to have influence on the utilization of buildings became very limited. It does not help either that the area has been divided up among several owners, and buying back the land is not a possible solution. We can only hope that new developments recently evolved at the urban fringe will have a positive impact on the future of the military barracks”.(Respondent 2)

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| ID | Settlement Name | Object Name | Size (ha) | Former Function | New Function | Redeveloped | Partially Renewed | Intact | Selected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aszód | József Attila barracks | 5.85 | barrack | Mixed | X | No | ||

| 2 | Baja | Bethlen Gábor barracks | 28.33 | barrack | - | X | No | ||

| 3 | Baja | training ground | 90.62 | training ground | Military | X | No | ||

| 4 | Baja | Damjanich jános barracks | 16.40 | barrack | Commercial | X | Yes | ||

| 5 | Balatonfüred | hospital, sanatorium | 1.81 | hospital | Culture | X | No | ||

| 6 | Berettyóújfalu | airport | 164.31 | airport | Agriculture | X | No | ||

| 7 | Bócsa | training ground | 950.63 | training ground | Nature reserve | X | No | ||

| 8 | Budapest | military residential buildings | 14.94 | residential building | Mixed | X | Yes | ||

| 9 | Budapest | Dózsa György barracks | 7.17 | barrack | Mixed | X | Yes | ||

| 10 | Budapest | Landler Jenő barracks | 13.22 | barrack | Mixed | X | Yes | ||

| 11 | Budapest | hospital | 7.33 | hospital | - | X | Yes | ||

| 12 | Budapest | Rákóczi Ferenc barracks | 19.11 | barrack | Mixed | X | Yes | ||

| 13 | Budapest | airport | 43.48 | airport | Sport, recreation | X | Yes | ||

| 14 | Budapest | barracks | 10.20 | barrack | Industrial | X | Yes | ||

| 15 | Budapest | military residential buildings | 0.43 | residential building | Residential | X | Yes | ||

| 16 | Budapest | military residential buildings | 1.77 | residential building | Residential | X | Yes | ||

| 17 | Budapest | radio station | 3.42 | radio station | Industrial | X | Yes | ||

| 18 | Budapest | Beloiannisz barracks | 20.33 | barrack | Residential | X | Yes | ||

| 19 | Budapest | Stromfeld Aurél barracks | 26.31 | barrack | Industrial | X | Yes | ||

| 20 | Budapest | Budatétény barracks | 3.20 | barrack | Industrial | X | Yes | ||

| 21 | Cegléd | Kossuth Lajos barracks | 24.18 | barrack | Mixed | X | Yes | ||

| 22 | Cegléd | barracks, ammunition depot | 10.08 | barrack | Industrial | X | Yes | ||

| 23 | Cegléd | ammunition depot | 25.77 | warehouse | - | X | Yes | ||

| 24 | Csákvár | airport | 195.67 | airport | Nature reserve | X | No | ||

| 25 | Csákvár | barracks | 24.52 | barrack | Industrial | X | No | ||

| 26 | Császár | barracks | 116.81 | barrack | - | X | No | ||

| 27 | Csemő | ammunition depot | 35.88 | warehouse | - | X | No | ||

| 28 | Csévharaszt | ammunition depot | 74.13 | warehouse | Tourism | X | No | ||

| 29 | Debrecen | Gábor Áron barracks | 17.70 | barrack | Mixed | X | Yes | ||

| 30 | Debrecen | Esze Tamás barracks | 27.38 | barrack | Prison | X | Yes | ||

| 31 | Debrecen | radio station | 0.76 | radio station | Residential | X | Yes | ||

| 32 | Debrecen | airport | 402.45 | airport | Airport | X | Yes | ||

| 33 | Debrecen | ammunition depot | 10.77 | warehouse | - | X | Yes | ||

| 34 | Debrecen | radio station | 0.65 | radio station | Residential | X | Yes | ||

| 35 | Debrecen | training ground | 240.01 | training ground | Nature reserve | X | Yes | ||

| 36 | Debrecen | radio station | 0.86 | radio station | Residential | X | Yes | ||

| 37 | Debrecen | warehouse | 1.92 | warehouse | Industrial | X | Yes | ||

| 38 | Debrecen | ammunition depot | 11.52 | warehouse | Sport, recreation | X | Yes | ||

| 39 | Dunaföldvár | Hunyadi barracks | 14.78 | barrack | Mixed | X | No | ||

| 40 | Dunaújváros | Tolbuchin barracks | 15.90 | barrack | Industrial | X | Yes | ||

| 41 | Dunavarsány | radio station | 10.51 | radio station | Tourism | X | No | ||

| 42 | Esztergom | Malinovszkij barracks | 7.39 | barrack | Commercial | X | Yes | ||

| 43 | Esztergom | Rózsa Ferenc barracks | 11.45 | barrack | Mixed | X | Yes | ||

| 44 | Esztergom | KECS barracks | 5.65 | barrack | - | X | Yes | ||

| 45 | Esztergom | Zalka Máté barracks | 19.13 | barrack | Industrial | X | Yes | ||

| 46 | Esztergom | Nagy Sándor barracks | 38.60 | barrack | - | X | Yes | ||

| 47 | Esztergom | hospital | 3.45 | hospital | Education | X | Yes | ||

| 48 | Etyek | Fürst Sándor barracks | 16.04 | barrack | Residential | X | No | ||

| 49 | Etyek | training ground | 40.24 | training ground | - | X | No | ||

| 50 | Fertőd | Klapka György barracks | 17.98 | barrack | Mixed | X | No | ||

| 51 | Fertőd | ammunition depot | 5.15 | warehouse | Agriculture | X | No | ||

| 52 | Fertőd | radio station | 3.62 | radio station | Utility | X | No | ||

| 53 | Gödöllő | warehouse | 29.40 | warehouse | Culture | X | No | ||

| 54 | Győr | Frigyes barracks | 2.77 | barrack | Mixed | X | Yes | ||

| 55 | Győr | Vadász barracks | 12.20 | barrack | Mixed | X | Yes | ||

| 56 | Győr | Lovassági barracks | 15.52 | barrack | Residential | X | Yes | ||

| 57 | Győr | warehouse | 2.63 | warehouse | - | X | Yes | ||

| 58 | Hajdúböszörmény | fuel depot | 8.15 | warehouse | - | X | Yes | ||

| 59 | Hajdúhadház | training ground | 1711.72 | training ground | Military | X | No | ||

| 60 | Hajmáskér | barracks | 40.30 | barrack | - | X | No | ||

| 61 | Hajmáskér | barracks | 5.45 | barrack | - | X | No | ||

| 62 | Hajmáskér | ammunition depot | 30.54 | warehouse | - | X | No | ||

| 63 | Igal | radar station | 22.44 | radio station | Industrial | X | No | ||

| 64 | Kalocsa | airport | 474.26 | airport | Airport | X | No | ||

| 65 | Kalocsa | Bethlen Gábor barracks | 39.88 | barrack | - | X | No | ||

| 66 | Kaposszekcső | Tolbuchin barracks | 33.34 | barrack | Industrial | X | No | ||

| 67 | Kecskemét | Losonczi barracks | 13.00 | barrack | Mixed | X | Yes | ||

| 68 | Kecskemét | Zrínyi barracks | 3.88 | barrack | Education | X | Yes | ||

| 69 | Kecskemét | Petőfi barracks | 2.41 | barrack | Residential | X | Yes | ||

| 70 | Kecskemét | Homokbánya barracks | 70.07 | barrack | Mixed | X | Yes | ||

| 71 | Kecskemét | Zalka Máté barracks | 6.70 | barrack | Commercial | X | Yes | ||

| 72 | Kecskemét | training ground | 131.34 | training ground | - | X | Yes | ||

| 73 | Kecskemét | helicopter base | 56.10 | airport | Industrial | X | Yes | ||

| 74 | Kecskemét | fuel depot | 3.59 | warehouse | Residential | X | Yes | ||

| 75 | Kecskemét | KECS barracks | 2.20 | barrack | Prison | X | Yes | ||

| 76 | Kiskunhalas | Esze Tamás barracks | 27.49 | barrack | Mixed | X | Yes | ||

| 77 | Kiskunhalas | Gábor Áron barracks | 6.44 | barrack | Industrial | X | Yes | ||

| 78 | Kiskunlacháza | Kilián György barracks, airport | 510.17 | airport | - | X | No | ||

| 79 | Kiskunmajsa | Ságvári Endre barracks | 39.67 | barrack | Mixed | X | No | ||

| 80 | Komárom | Klapka György barracks | 64.46 | barrack | Mixed | X | Yes | ||

| 81 | Komárom | barracks | 8.77 | barrack | - | X | Yes | ||

| 82 | Kunmadaras | airport | 769.22 | airport | - | X | No | ||

| 83 | Lepsény | Szondi György barracks | 35.20 | barrack | Mixed | X | No | ||

| 84 | Lepsény | ammunition depot | 9.57 | warehouse | - | X | No | ||

| 85 | Lovasberény | barracks | 13.27 | barrack | Industrial | X | No | ||

| 86 | Lovasberény | ammunition depot | 152.34 | warehouse | - | X | No | ||

| 87 | Lőrinci | Damjanich János barracks | 11.79 | barrack | Industrial | X | No | ||

| 88 | Lőrinci | ammunition depot | 2.91 | warehouse | - | X | No | ||

| 89 | Mád | fuel depot | 17.33 | warehouse | Industrial | X | No | ||

| 90 | Mezőkövesd | barracks | 24.05 | barrack | - | X | No | ||

| 91 | Mór | Kinizsi Pál barracks | 14.81 | barrack | Industrial | X | No | ||

| 92 | Mór | ammunition depot | 15.49 | warehouse | Mixed | X | No | ||

| 93 | Mosonmagyaróvár | Táncsics Mihály barracks | 12.32 | barrack | Mixed | X | Yes | ||

| 94 | Nagykőrös | Nagy Sándor barracks | 21.39 | barrack | Industrial | X | Yes | ||

| 95 | Nagykőrös | Széchenyi barracks | 15.28 | barrack | Industrial | X | Yes | ||

| 96 | Nagytevel | training ground | 131.49 | training ground | Sport, recreation | X | No | ||

| 97 | Nagyvázsony | barracks | 32.40 | barrack | - | X | No | ||

| 98 | Nyíregyháza | warehouse | 1.89 | warehouse | Commercial | X | Yes | ||

| 99 | Orgovány | training ground | 196.93 | training ground | Nature reserve | X | No | ||

| 100 | Pápa | Bottyán barracks | 63.21 | barrack | Industrial | X | Yes | ||

| 101 | Pétfürdő | fuel depot | 33.27 | warehouse | Industrial | X | No | ||

| 102 | Piliscsaba | Perczel Mór barracks | 39.22 | barrack | Education | X | No | ||

| 103 | Polgárdi | Kossuth Lajos barracks | 19.50 | barrack | Mixed | X | No | ||

| 104 | Polgárdi | ammunition depot | 8.40 | warehouse | - | X | No | ||

| 105 | Sárbogárd | Rákóczi barracks | 19.73 | barrack | Industrial | X | No | ||

| 106 | Sárbogárd | military residential buildings | 2.62 | residential building | Residential | X | No | ||

| 107 | Sárbogárd | ammunition depot | 6.07 | warehouse | Industrial | X | No | ||

| 108 | Sármellék | airport | 384.29 | airport | Airport | X | No | ||

| 109 | Szeged | Öthalom barracks | 120.43 | barrack | R&D | X | Yes | ||

| 110 | Székesfehérvár | Gyalogsági barracks | 12.18 | barrack | Education | X | Yes | ||

| 111 | Székesfehérvár | Kossuth Lajos barracks | 14.46 | barrack | Industrial | X | Yes | ||

| 112 | Székesfehérvár | Lovassági barracks | 16.63 | barrack | Mixed | X | Yes | ||

| 113 | Székesfehérvár | barracks, airport | 419.25 | barrack | Industrial | X | Yes | ||

| 114 | Szentendre | Dózsa György barracks | 33.16 | barrack | - | X | Yes | ||

| 115 | Szentkirályszabadja | barracks | 61.19 | barrack | - | X | No | ||

| 116 | Szolnok | József Attila barracks | 11.56 | barrack | Industrial | X | Yes | ||

| 117 | Szolnok | Nagy barracks | 3.70 | barrack | Mixed | X | Yes | ||

| 118 | Szolnok | Bocskai István barracks | 18.17 | barrack | Residential | X | Yes | ||

| 119 | Szolnok | hospital | 2.38 | hospital | Residential | X | Yes | ||

| 120 | Szombathely | Dózsa György barracks | 26.62 | barrack | - | X | Yes | ||

| 121 | Szombathely | ammunition depot | 5.62 | warehouse | Residential | X | Yes | ||

| 122 | Tab | Hunyadi barracks | 31.56 | barrack | - | X | No | ||

| 123 | Tab | training ground | 15.40 | training ground | Sport, recreation | X | No | ||

| 124 | Táborfalva | Kossuth Lajos barracks | 18.63 | barrack | - | X | No | ||

| 125 | Tamási | Szondi György barracks | 18.21 | barrack | Mixed | X | No | ||

| 126 | Tápiószentmárton | airport | 188.77 | airport | Airport | X | No | ||

| 127 | Tarany | radio station | 6.62 | radio station | Agriculture | X | No | ||

| 128 | Tolna | Bem József barracks | 17.58 | barrack | Mixed | X | No | ||

| 129 | Tolna | ammunition depot | 44.34 | warehouse | Agriculture | X | No | ||

| 130 | Tököl | airport | 463.64 | airport | Mixed | X | No | ||

| 131 | Vác | fuel depot | 17.00 | warehouse | - | X | Yes | ||

| 132 | Vát | training ground | 522.47 | training ground | Nature reserve | X | No | ||

| 133 | Veszprém | barracks | 93.67 | barrack | Military | X | Yes | ||

| 134 | Veszprém | Kossuth Lajos barracks | 7.27 | barrack | Mixed | X | Yes | ||

| 135 | Zalaegerszeg | airport | 123.38 | airport | Airport | X | Yes |

References

- Jacek, G.; Rozan, A.; Desrousseaux, M.; Combroux, I. Brownfields over the Years: From Definition to Sustainable Reuse. Environ. Rev. 2022, 30, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.; De Sousa, C.; Tiesdell, S. Brownfield Development: A Comparison of North American and British Approaches. Urban Stud. 2010, 47, 75–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alker, S.; Joy, V.; Roberts, P.; Smith, N. The Definition of Brownfield. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2000, 43, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunc, J.; Martinát, S.; Tonev, P.; Frantál, B. Destiny of Urban Brownfields: Spatial Patterns and Perceived Consequences of Post-Socialistic Deindustrialization. Transylv. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2014, 10, 109–128. [Google Scholar]

- Trócsányi, A.; Karsai, V.; Pirisi, G. Formal Urbanisation in East-Central Europe. Hung. Geogr. Bull. 2024, 73, 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorescu, I.; Dumitrică, C.; Dumitrașcu, M.; Mitrică, B.; Dumitrașcu, C. Urban Development and the (Re)Use of the Communist-Built Industrial and Agricultural Sites after 1990. The Showcase of Bucharest–Ilfov Development Region. Land 2021, 10, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Săgeată, R.; Mitrică, B.; Cercleux, A.-L.; Grigorescu, I.; Hardi, T. Deindustrialization, Tertiarization and Suburbanization in Central and Eastern Europe. Lessons Learned from Bucharest City, Romania. Land 2023, 12, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalski, T. A Geographic Approach to the Transformation Process in European Post-Communist Countries. In A Geographic Approach to the Transformation Process in European Post–Communist Countries; Wydawnictwo Bernardinum: Gdynia, Poland, 2006; pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- King, L.P.; Szelényi, I. 10. Post-Communist Economic System. In The Handbook of Economic Sociology, 2nd ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 205–230. [Google Scholar]

- Camerin, F.; Córdoba Hernández, R. What Factors Guide the Recent Spanish Model for the Disposal of Military Land in the Neoliberal Era? Land Use Policy 2023, 134, 106911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Relley, Z.E. From Totalitarian Central Planning to a Market Economy: Decentralization and Privatization in Hungary. J. Priv. Enterp. 2001, 17, 111–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ponzini, D.; Vani, M. Planning for Military Real Estate Conversion: Collaborative Practices and Urban Redevelopment Projects in Two Italian Cities. Urban Res. Pract. 2014, 7, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ural, E.; Severcan, Y.C. Assessing User Preferences Regarding Military Site Regeneration: The Case of the Fourth Corps Command in Ankara. Cities 2022, 129, 103807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarczewski, W.; Kuryło, M. Regeneration of Post-Military Areas in Poland. Eur. XXI 2010, 21, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korczak, J. Regeneration of Military Sites as a Factor in the Improvement of the Town’s Logistics Infrastructure. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 151, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Moniak, A. The Functioning of the Collective Memory of Lower Silesians within the Multicultural Community of Borne Sulinowo. Hist. Teor. 2016, 1, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Myrttinen, H. Base Conversion in Central and Eastern Europe 1989–2003. BICC 2003, 30. Available online: https://www.bicc.de/Publikationen/paper30.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Glintić, M. Revitalization of Military Brownfields in Eastern and Central Europe. Strani Prav. Ziv. 2015, 1, 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- Hercik, J.; Szczyrba, Z. Post-Military Areas as Space for Business Opportunities and Innovation. Stud. Ind. Geogr. Comm. Pol. Geogr. Soc. 2012, 19, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assylkhanova, A.; Nagy, G.; Morar, C.; Teleubay, Z.; Boros, L. A Critical Review of Dark Tourism Studies. Hung. Geogr. Bull. 2024, 73, 413–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, E.; Laprise, M.; Lufkin, S. Urban Brownfields: Origin, Definition, and Diversity. In Neighbourhoods in Transition; The Urban Book Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 7–45. [Google Scholar]

- Bolleter, J.; Edwards, N.; Cameron, R.; Hooper, P. Density My Way: Community Attitudes to Neighbourhood Densification Scenarios. Cities 2024, 145, 104596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, M.; Schneider, J. The Welfare Landscape and Densification—Residents’ Relations to Local Outdoor Environments Affected by Infill Development. Land 2023, 12, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloutas, T.; Frangopoulos, Y.; Makridou, A.; Kostaki, E.; Kourkouridis, D.; Spyrellis, S.N. Exploring Spatial Proximity and Social Exclusion through Two Case Studies of Roma Settlements in Greece. Land 2024, 13, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hercik, J.; Šimáček, P.; Szczyrba, Z.; Smolová, I. Military Brownfields in the Czech Republic and the Potential for Their Revitalisation, Focused on Their Residential Function. Quaest. Geogr. 2014, 33, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnicka-Bogusz, M. Innovative Use in Adaptation of Post Military Barrack Complexes. In Proceedings of the International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference, Albena, Bulgaria, 2–8 July 2018; SGEM: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Szabó, B.; Kovalcsik, T.; Kovács, Z. Lessons of the Regeneration of Former Soviet Military Sites in Hungary. In Achieving Sustainability in Ukraine Through Military Brownfields Redevelopment. NATOARW 2023. NATO Science for Peace and Security Series C: Environmental Security; Morar, C., Berman, L., Erdal, S., Niemets, L., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerin, F.; Gastaldi, F. Italian Military Real Estate Assets Re-Use Issues and Opportunities in Three Capital Cities. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerin, F. Former Military Barracks as Places for Informal Placemaking in Italy. An Inventory for New Insights. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2024, 17, 190–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morar, C.; Nagy, G.; Dulca, M.; Boros, L.; Sehida, K. Aspects Regarding the Military Cultural-Historical Heritage in the City of Oradea (Romania). Ann. Anal. Istrske Mediter. Stud. Ser. Hist. Sociol. 2019, 29, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jevremovic, L.; Stanojevic, A.; Djordjevic, I.; Turnsek, B. The Redevelopment of Military Barracks between Discourses of Urban Development and Heritage Protection: The Case Study of Nis, Serbia. Spatium 2021, 46, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnicka-Bogusz, M. The Genius Loci Issue in the Revalorization of Post-Military Complexes: Selected Case Studies in Legnica (Poland). Buildings 2022, 12, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemets, L.; Sehida, K.; Babichev, A.; Subiros, J.V.; Morar, C.; Grama, V.; Kravchenko, K.; Telebienieva, I. Issues of the Military Brownfields in Ukraine: A Sustainable Development Perspective. In Achieving Sustainability in Ukraine Through Military Brownfields Redevelopment. NATOARW 2023. NATO Science for Peace and Security Series C: Environmental Security; Morar, C., Berman, L., Erdal, S., Niemets, L., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matković, I.; Jakovcic, M. Conversion and Sustainable Use of Abandoned Military Sites in the Zagreb Urban Agglomeration. Hrvat. Geogr. Glas. Croat. Geogr. Bull. 2020, 82, 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komár, A. The Problems of the Revitalisation and Reusing of Former Military Lands in Central and Eastern Europe. Geografie 1998, 103, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezentsev, K.; Niemets, L.; Sehida, K. Transforming Brownfields: Urban Renewal in Ukrainian Cities. In Achieving Sustainability in Ukraine Through Military Brownfields Redevelopment. NATOARW 2023. NATO Science for Peace and Security Series C: Environmental Security; Morar, C., Berman, L., Erdal, S., Niemets, L., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendt, J.A.; Bógdał-Brzezińska, A. Historical Context and Political Conditions of Revitalization of Degraded Military Areas: Case Study “Garnizon” in Gdańsk. In Achieving Sustainability in Ukraine Through Military Brownfields Redevelopment. NATOARW 2023. NATO Science for Peace and Security Series C: Environmental Security; Morar, C., Berman, L., Erdal, S., Niemets, L., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauhiainen, J. Conversion of Military Brownfields in Oulu. In Rebuilding the City. Managing the Built Environment and Remediation of Brownfields; Urban, V.D., Ed.; Baltic University Press: Hamburg, Germany, 2007; pp. 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Havlick, D.G. Disarming Nature: Converting Military Lands to Wildlife Refuges. Geogr. Rev. 2011, 101, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, P.; Gallent, N.; Howe, J. Re-Use of Small Airfields: A Planning Perspective. Prog. Plann. 2001, 55, 195–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magyar, B.; Stickel, J.; Vero, L.; Padar, I. Assessment and Remediation of Environmental Damage in the Abandoned Soviet Military Bases in Hungary. In Proceedings of the IAHS-AISH Publication, Rome, Italy, 13–17 September 1994; pp. 255–266. [Google Scholar]

- Kádár, K. The Rehabilitation of Former Soviet Military Sites in Hungary. Hung. Geogr. Bull. 2014, 63, 437–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauhiainen, J. Militarisation, Demilitarisation and Re-Use of Military Areas: The Case of Estonia. Geography 1997, 82, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagaeen, S.; Clark, C. Sustainable Regeneration of Former Military Sites; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Seljamaa, E.-H.; Czarnecka, D.; Demski, D. “Small Places, Large Issues”: Between Military Space and Post-Military Place. Folk. Electron. J. Folk. 2017, 70, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, E.; Pesce, M.; Pizzol, L.; Alexandrescu, F.M.; Giubilato, E.; Critto, A.; Marcomini, A.; Bartke, S. Brownfield Regeneration in Europe: Identifying Stakeholder Perceptions, Concerns, Attitudes and Information Needs. Land Use Policy 2015, 48, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peric, A.; Miljus, M. The Regeneration of Military Brownfields in Serbia: Moving towards Deliberative Planning Practice? Land Use Policy 2021, 102, 105–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagaeen, S.G. Redeveloping Former Military Sites: Competitiveness, Urban Sustainability and Public Participation. Cities 2006, 23, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazia, C.; Catania, G.F.G.; Sortino, F. The Recovery of Disused Infrastructure and Military Areas in Spain and Italy, Contributions to the Regeneration of Territories. In International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagaeen, S.; Celia, C. (Eds.) Sustainable Regeneration of Former Military Sites; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Morar, C.; Berman, L.; Erdal, S.; Niemets, L. (Eds.) Achieving Sustainability in Ukraine Through Military Brownfields Redevelopment; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2024; ISBN 978-94-024-2277-1. [Google Scholar]

- Squires, G.; Hutchison, N. Barriers to Affordable Housing on Brownfield Sites. Land Use Policy 2021, 102, 105276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, M.; Craighill, P.; Mayer, H.; Zukin, C.; Wells, J. Brownfield Redevelopment and Affordable Housing: A Case Study of New Jersey. Hous. Policy Debate 2001, 12, 515–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, C.A. Turning Brownfields into Green Space in the City of Toronto. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 62, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupar, S. Waste Frontiers/War Enclosures: Decolonial Geosocial Analysis of Contaminated Military Land Conversions. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2024, 114, 977–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganser, R. Redeveloping the Redundant Defence Estate in Regions of Growth and Decline—Challenges for Spatial Planning; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 9781409427414. [Google Scholar]

- Bagaeen, S. Framing Military Brownfields as a Catalyst for Urban Regeneration. In Sustainable Regeneration of Former Military Sites; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Oueslati, W.; Alvanides, S.; Garrod, G. Determinants of Urban Sprawl in European Cities. Urban Stud. 2015, 52, 1594–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, Z.; Farkas, Z.J.; Egedy, T.; Kondor, A.C.; Szabó, B.; Lennert, J.; Baka, D.; Kohán, B. Urban Sprawl and Land Conversion in Post-Socialist Cities: The Case of Metropolitan Budapest. Cities 2019, 92, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardi, T.; Repaská, G.; Veselovský, J.; Vilinová, K. Environmental Consequences of the Urban Sprawl in the Suburban Zone of Nitra: An Analysis Based on Landcover Data. Geogr. Pannonica 2020, 24, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubeš, J.; Szmytkie, R. Environmental Acceptability of Suburban Sprawl around Two Differently Sized Czech Cities. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2024, 32, 1231–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasárus, G.L.; Farkas, J.Z.; Hoyk, E.; Kovács, A.D. The Impact of Urban Sprawl on the Urban-Rural Fringe of Post-Socialist Cities in Central and Eastern Europe—Case Study from Hungary. J. Urban Manag. 2024, 13, 800–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlatar, J. Zagreb. Cities 2014, 39, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammaru, T.; Leetmaa, K.; Silm, S.; Ahas, R. Temporal and Spatial Dynamics of the New Residential Areas around Tallinn. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2009, 17, 423–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Fina, S.; Siedentop, S. Post-Socialist Sprawl: A Cross-Country Comparison. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 1357–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmytkie, R. The Impact of Residential Suburbanization on Changes in the Morphology of Villages in the Suburban Area of Wrocław, Poland. Environ. Socio-Econ. Stud. 2020, 8, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, R.; Klobučník, M. Residential Suburbanisation in the Hinterland of Bratislava—A Case Study of Municipalities in the Austrian Border Area. Hung. Geogr. Bull. 2021, 70, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csomós, G.; Szalai, Á.; Farkas, J.Z. A Sacrifice for the Greater Good? On the Main Drivers of Excessive Land Take and Land Use Change in Hungary. Land Use Policy 2024, 147, 107352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egedy, T.; Szigeti, C.; Harangozó, G. Suburban Neighbourhoods versus Panel Housing Estates—An Ecological Footprint-Based Assessment of Different Residential Areas in Budapest, Seeking for Improvement Opportunities. Hung. Geogr. Bull. 2024, 73, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, P.; Klein, G.; Todes, A. Scholarship and Policy on Urban Densification: Perspectives from City Experiences. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2021, 43, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulić, O.; Krklješ, M. Brownfield Redevelopment as a Strategy for Preventing Urban Sprawl, 17 February 2014; pp. 1371–1378. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281651820_Brownfield_Redevelopment_as_a_Strategy_for_Preventing_Urban_Sprawl.2014 (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Baing, A.S. Containing Urban Sprawl? Comparing Brownfield Reuse Policies in England and Germany. Int. Plan. Stud. 2010, 15, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kádár, K. Funkcióváltás Szovjet Katonai Objektumok Helyén. Barnamezős Katonai Területek Újra-Hasznosítása Hat Magyar Megyeszékhelyen [Functional Change at the Location of Soviet Mili-Tary Sites. Reuse of Military Brownfields in Six Hungarian County Centers]. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pécs, Pécs, Hungary, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Copernicus Services CORINE Land Cover. 2018. Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/en/products/corine-land-cover/clc2018 (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Copernicus Services CORINE Land Cover. 1990. Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/en/products/corine-land-cover/clc-1990 (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Pénzes, J.; Hegedűs, L.D.; Makhanov, K.; Túri, Z. Changes in the Patterns of Population Distribution and Built-Up Areas of the Rural–Urban Fringe in Post-Socialist Context—A Central European Case Study. Land 2023, 12, 1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsas, C.J.L. Qualitative Planning Philosophy and the Governance of Urban Revitalization, a Plea for Cultural Diversity. Urban Gov. 2022, 2, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Geographical Location | Level of Redevelopment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Intact | Redeveloped | ||

| Relative position of the site in 1990 | Within the compact city | Possible sprawl | Compact |

| Outside the urban fabric | No direct impact | Sprawl | |

| Respondent | Interviewee | Date of the Interview | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Kecskemét—strategic and urban development manager | 27 February 2024 | 3 h |

| 2. | Cegléd—urban developer | 6 March 2024 | 1 h |

| 3. | Budapest, 3rd district—project manager | 22 March 2024 | 2 h |

| 4. | Győr—property manager | 25 March 2024 | 1 h |

| 5. | Budapest, 18th district—museologist | 3 April 2024 | 1 h |

| 6. | Szeged—former chief architect | 5 April 2024 | 2 h |

| 7. | Szeged—former chief architect | 10 April 2024 | 1.5 h |

| 8. | Veszprém—archive director | 16 April 2024 | 1 h |

| Number | Size (Hectare) | Share (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intact sites (both in the compact city and periphery) | 12 | 613.51 | 24.2 |

| Redeveloped sites in the compact city (‘compact’) | 33 | 330.85 | 13.0 |

| Redeveloped sites in peripheral locations (‘peripheral’) | 28 | 1595.82 | 62.8 |

| Total | 73 | 2540.18 | 100.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szabó, B.; Kovalcsik, T.; Kovács, Z. Regeneration of Military Brownfield Sites: A Possible Tool for Mitigating Urban Sprawl? Land 2025, 14, 596. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14030596

Szabó B, Kovalcsik T, Kovács Z. Regeneration of Military Brownfield Sites: A Possible Tool for Mitigating Urban Sprawl? Land. 2025; 14(3):596. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14030596

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzabó, Bence, Tamás Kovalcsik, and Zoltán Kovács. 2025. "Regeneration of Military Brownfield Sites: A Possible Tool for Mitigating Urban Sprawl?" Land 14, no. 3: 596. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14030596

APA StyleSzabó, B., Kovalcsik, T., & Kovács, Z. (2025). Regeneration of Military Brownfield Sites: A Possible Tool for Mitigating Urban Sprawl? Land, 14(3), 596. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14030596

_Cheung.jpeg)