Abstract

The 2025 large-scale forest fire in North Gyeongsang Province (Gyeongbuk) caused habitat fragmentation and disrupted ecological networks. This study quantitatively assessed both structural and functional connectivity loss and derived scientifically grounded restoration priorities. Fire intensity was assessed using Sentinel-2-based dNBR, and connectivity changes before and after the fire were analyzed by integrating MSPA (Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis) and Omniscape (circuit theory-based model). MSPA captured extreme fragmentation, showing an 84% reduction in core habitats and a 976% increase in isolated patches, but failed to reflect functional movement flows. Omniscape approximated this using circuit theory, quantifying a 60% loss in cumulative current flow within the fire boundary and confirming that structural disconnection led to functional connectivity collapse. The restoration priority assessment (53 patches), based on source–sink theory, identified 14 high-priority patches (66% of total area). These patches were characterized by their adjacency to undamaged external cores, which serve as potential population sources for post-restoration recolonization. Notably, the top-priority areas were identified as key connection points within the national ecological corridor where Juwangsan National Park, the Nakdong Ridge, and Grade 1 Ecological Natural Areas overlap. This study demonstrated that integrating MSPA with Omniscape can simultaneously quantify both morphological fragmentation and functional disconnection caused by forest fires. This framework suggests that restoration planning should consider connectivity with broader ecological networks, in addition to recovering lost habitat area.

1. Introduction

Forest fires are a primary disturbance factor altering forest ecosystem structure and function [1,2], with climate change accelerating their frequency and intensity [3]. Beyond vegetation loss, large-scale fires cause habitat fragmentation and disrupt connectivity between habitats, diminishing long-term ecosystem resilience [4,5,6]. South Korea has experienced increasingly larger forest fires over the past decade, with the 2025 Gyeongsangbuk-do fire marking the largest single-disaster forest damage on record [7]. Such large-scale disturbances highlight the need for systematic approaches to restore landscapes and reconnect fragmented areas.

Habitat connectivity—the degree to which landscapes facilitate movement and gene flow—is recognized as a key factor determining ecosystem recovery after disturbance [8,9,10,11,12,13]. When connectivity is weakened, population movement is restricted and recovery is delayed, particularly as habitat fragmentation worsens [10,11].

In South Korea’s forest ecosystems, the yellow-throated martens (Martes flavigula) are considered a suitable surrogate species for assessing habitat connectivity [14]. As a forest-dwelling medium-sized mammal exhibiting high mobility and utilizing diverse forest types such as broadleaf forests and mixed forests, it represents the movement characteristics of forest landscapes and is useful for assessing the potential for recolonization between fragmented habitats following forest fires [14]. Therefore, this study selected the yellow-throated martens as the representative species to analyze habitat fragmentation and changes in functional connectivity caused by forest fires.

Habitat connectivity analysis has employed various spatial analysis techniques. Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis (MSPA), a form-based spatial pattern analysis, quantifies landscape structure using binary land cover information and identifies the spatial relationships of key landscape elements such as core, edge, and link areas [15,16]. Meanwhile, the Circuitscape and Omniscape models, based on circuit theory, quantify functional connectivity between habitats using the principle of current flow [17]. These models express potential wildlife movement routes or gene flow as current density, enabling the identification of remaining connectivity corridors and fragmentation points after forest fires [18,19]. In particular, Omniscape’s cumulative current density maps reflect connectivity flows across entire landscapes, not limited to specific species, making them useful for assessing the linkage of multi-species habitats and ecosystem services [19,20,21].

However, existing connectivity studies typically employ either structural (MSPA) or functional (circuit theory) approaches in isolation, and recent research has highlighted the need to integrate both approaches [22,23,24]. To address this methodological gap, this study applies source–sink population theory [25,26,27] as the conceptual basis for restoration prioritization. In this framework, habitats are classified as sources (where populations increase) or sinks (where populations depend on external recruitment) [25]. After fire-induced habitat loss, patches adjacent to undamaged sources have greater potential for recolonization [28,29,30], providing a theoretical basis for connectivity-based priority assessment.

This study aimed to: (1) quantify both structural and functional connectivity loss by integrating MSPA and Omniscape, and (2) develop a restoration priority framework grounded in source–sink theory. The framework was applied to the 2025 Gyeongbuk forest fire and examined in relation to national ecological corridors and protected areas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

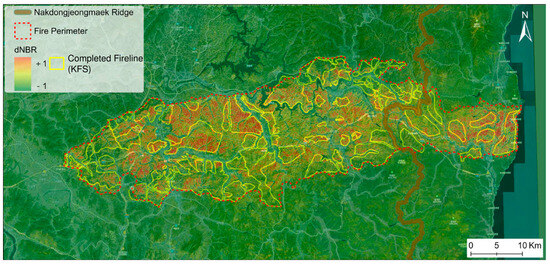

The study area was defined as approximately 550,000 ha, encompassing a buffer zone of about 10 km radius around the core damage area, including the site of the large-scale forest fire that occurred in Gyeongsangbuk-do in March 2025 (Figure 1). The Korea Forest Service conducted an initial damage survey by local governments from 28 March to 8 April, immediately after the fire was extinguished, and confirmed the damage area through field verification by a joint investigation team from 9 April to 15 April. Concurrently, an emergency diagnosis was conducted on 4207 secondary areas at risk of damage from 28 March to 11 April. Boundary data for fully extinguished areas provided by this survey were overlaid with results from Sentinel-2 imagery-based NBR analysis to verify the extent of forest fire damage.

Figure 1.

Map of the study area showing the burn severity (dNBR) of the 2025 Gyeongsangbuk-do forest fire, the derived fire perimeter, completed firelines (KFS), and the Nakdongjeongmaek Ridge.

The 10 km buffer is based on the average home range (32.2 ± 12.9 km2) and maximum movement distance (approximately 15 km) of the yellow-throated marten (Martes flavigula) [14] and is considered an ecologically valid range for analyzing the restoration potential of habitat networks fragmented by forest fires, given its suitability for assessing population movement and connectivity recovery around fire-damaged areas and its consideration of the spatial range of medium-sized carnivores [23,31].

Furthermore, this region forms a major connecting axis for the eastern South Korean forest ecosystem due to its north–south continuous mountainous terrain and high forest coverage, serving as the backbone of the ecological network linking the Baekdudaegan Range, its main ridges, and secondary ridges. Therefore, the study area is evaluated as highly representative not only for assessing fire damage but also for evaluating the continuity and resilience of the national ecological axis.

2.2. Analysis of Forest Fire Intensity Using Satellite Imagery

The intensity of forest fire damage is assessed by calculating the Normalized Burn Ratio (NBR) using the NIR (Band 8) and SWIR (Band 12) of Sentinel-2 imagery and evaluated using the dNBR (differenced Normalized Burn Ratio) index, which calculates the difference between pre-fire (1 March 2024) and post-fire (28 March 2025) imagery. Analysis was performed on forest areas after removing cloud and haze regions.

Forest fire intensity classifications were determined using the USGS FIREMON guidelines [32]. The classification intervals were defined as unaffected (dNBR < 0.10), low-intensity (0.10–0.27), medium-intensity (0.27–0.44), high-intensity (0.44–0.66), and very-high-intensity (>0.66). This criterion was also utilized in domestic analyses of the Uljin forest fire in South Korea, in 2022 [33,34].

2.3. Habitat Resistance Map Generation

A resistance surface is data that quantifies environmental factors that inhibit the movement or dispersal of organisms. After a forest fire, movement resistance increases due to factors like soil exposure and canopy loss. Therefore, a resistance surface reflecting disturbance intensity is used as a key input for assessing functional connectivity [35,36]. In this study, a resistance map was constructed using land cover, topography, and forest fire damage intensity as primary input data to reflect changes in habitat characteristics before and after forest fires. The details are as follows.

First, the National Land Cover Map produced by the Ministry of Environment (MOE) was used. This map is a dataset constructed for national environmental management and ecosystem monitoring. It is produced based on high-resolution satellite imagery (SPOT-5, Kompsat-2, Sentinel-2) and aerial photographs, categorized into major classes (Level-1, 7 items), intermediate classes (Level-2, 23 items), and detailed classes (Level-3, 41 items). Field verification maintains classification accuracy at approximately 85% or higher. This study used the 2022 Level-2 data to calculate baseline resistance values for each habitat type, assigning values within the range of 1–150 (deciduous/mixed forests 1, coniferous forests 2, natural grasslands 25, orchards 40, farmland 50–70, roads 90, residential areas 100–110, urban/industrial areas 120–150). The relative structure of these values reflects the habitat preference order of forest-dependent mammals in Korea (e.g., Asian martens): broadleaf/mixed forests > coniferous forests > open areas/artificial landscapes [14,37].

Second, to reflect topographic characteristics, slope was calculated from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) 30 m resolution Digital Elevation Model (DEM). The movement cost multiplier was set based on slope: 0–15° = 1.0 times, 15–25° = 1.1 times, 25–35°: 1.3 times, 35–45°: 1.8 times, and ≥45°: 2.5 times [31,37]. This classification reflects both domestic ecological corridor design and habitat preference studies (preference for flat or gently sloping terrain) and observations that post-fire topography acts as a movement corridor/barrier [37].

Third, to restore functional connectivity, the disturbance intensity caused by forest fires was incorporated into the resistance value [29,30]. Forest fire damage intensity was assessed using the previously analyzed dNBR, applying the criteria from Key & Benson (2006): undamaged areas (dNBR < 0.1) were assigned a resistance value of 0, low intensity (0.1–0.27) was 30, moderate intensity (0.27–0.44) was 80, high intensity (0.44–0.66) was 150, and very high intensity (>0.66) was 250 [32].

The final resistance maps were constructed separately for pre- and post-fire conditions. The pre-fire resistance map was calculated by multiplying the base land cover resistance value by the slope multiplier (base resistance × slope multiplier). The post-fire resistance map was constructed as an additive integrated model by adding the dNBR-based fire impact value to this base resistance.

Areas with high fire intensity and steep slopes were represented by high resistance values, while gently sloping areas with continuous forest cover were represented by low resistance values. This allowed for the assessment of changes in functional connectivity reflecting disturbance intensity after the fire.

2.4. MSPA Before and After Forest Fire

MSPA was applied to derive core habitats and quantify structural changes before and after the fire [15,16,38]. Input data consisted of binary forest masks extracted from the Ministry of Environment’s 2022 land cover map. Post-fire masks excluded forests with dNBR ≥ 0.1. Analysis parameters were: Edge width = 30 m (considering microclimate influence at forest edges [39]), Transition = True, Intext = 1. The ‘Core Area Index’ (Core/total forest area) and ‘Connectivity Index’ (Bridge + Loop/total forest area) were calculated. Analysis was performed using GuidosToolbox 3.8.

2.5. MSPA-Based Omniscape Connectivity Modeling

Omniscape, a circuit theory-based model, was applied to quantify functional connectivity changes [17,18,20]. Model inputs included pre- and post-fire resistance surfaces and core habitats (≥100 ha) from MSPA [15,38]. The movement radius was set to 15 km based on yellow-throated marten dispersal distance [14]. Connectivity loss was calculated as the difference between pre- and post-fire normalized current flow. Analysis was performed using Omniscape.jl (v0.6.2) in Julia [18,40].

2.6. Restoration Priority Assessment

The restoration priority assessment in this study combined the previously analyzed MSPA and Omniscape results, utilizing the following three key indicators for analysis:

- (1)

- Restoration Scale (S): The damaged core area within the fire boundary, representing the investment scale required for restoration.

- (2)

- Source Capacity (C): The area of undamaged core outside the fire boundary, quantifying the size of source habitats from which surrounding populations can migrate post-restoration [25].

- (3)

- Network Importance (I): The average current value of Omniscape within the fire boundary, indicating the extent to which the patch functions as a hub or bottleneck within the entire ecological network [17].

To select evaluation targets, cores intersecting the fire boundary were divided into internal and external areas. Among these, cores with an internal area of 100 ha or larger were extracted. Based on source–sink population theory, these were then divided into two groups based on the presence or absence of an external area. Following source–sink population theory, cores were classified based on their potential for population recovery. Cores with external areas were classified as the priority set because adjacent undamaged sources can provide population influx essential for post-restoration recolonization. Cores without external areas were classified as the deferred set, as they lack adjacent source populations and thus face greater challenges for natural recovery. This classification reflects a methodological framework for prioritization rather than a prescriptive restoration strategy.

Each indicator for the priority set (29 sites) was normalized to the range 0–1 using min–max normalization. These indicators were then integrated using the geometric mean to calculate restoration priority scores. The geometric mean assigns higher values when individual factors are balanced at high levels, making it a suitable integration method for ecological assessment systems where restoration effectiveness is determined by the interaction of multidimensional factors [12,35].

The Priority Score is calculated as follows:

The final restoration priority was categorized into three tiers: (1) High (Top Priority)—Top 50% within the priority assessment group, (2) Low (Second Priority)—Bottom 50% within the same group, (3) Deferred (Lower Priority)—24 cores without external sources. Finally, the characteristics of the restoration priority areas were examined based on the status of protected areas such as major ecological corridors and national parks within the study region.

3. Results

3.1. Forest Fire Intensity Results

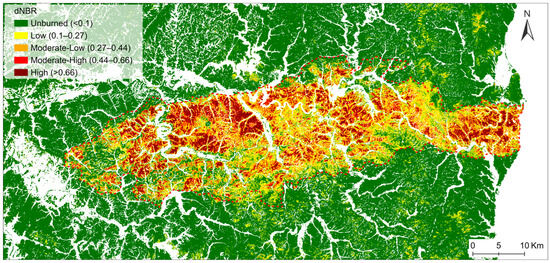

To quantify the intensity of the 2025 Gyeongbuk forest fires, the dNBR (differenced Normalized Burn Ratio) was calculated using the USGS forest fire intensity classification system. The total analyzed area within the fire boundaries was 113,171 ha, with an average dNBR value of 0.309 ± 0.265 (Table 1, Figure 2). The fire intensity classification results showed that the Unburned area (dNBR < 0.1) covered 26,151 ha (23.1%), while the Low-intensity area (dNBR 0.1–0.27) occupied the largest area at 38,105 ha (33.7%). Moderate–low-intensity damage areas (dNBR 0.27–0.44) covered 19,607 ha (17.3%), while moderate–high-intensity damage areas (dNBR 0.44–0.66) covered 11,823 ha (10.4%). High-intensity (High, dNBR > 0.66) damage areas totaled 17,486 ha (15.5%). High-intensity damage areas (Moderate–High + High) covered a total of 29,309 ha, accounting for 25.9% of the entire forest fire boundary. The average dNBR values by fire intensity were 0.031 ± 0.048 for unaffected areas, 0.183 ± 0.048 for low-intensity areas, 0.340 ± 0.048 for moderate–low-intensity areas, 0.546 ± 0.065 for moderate–high-intensity areas, and 0.804 ± 0.083 for high-intensity areas, confirming clear distinctions between intensity classes.

Table 1.

Fire severity classification and area distribution based on dNBR analysis.

Figure 2.

Forest fire burn severity classification based on dNBR (differenced Normalized Burn Ratio) derived from Sentinel-2 imagery. The classification follows USGS standards with five severity levels. The red dotted line indicates the fire perimeter. The study area experienced predominantly low-to-moderate severity burning.

3.2. Changes in Post-Fire Habitat Spatial Structure

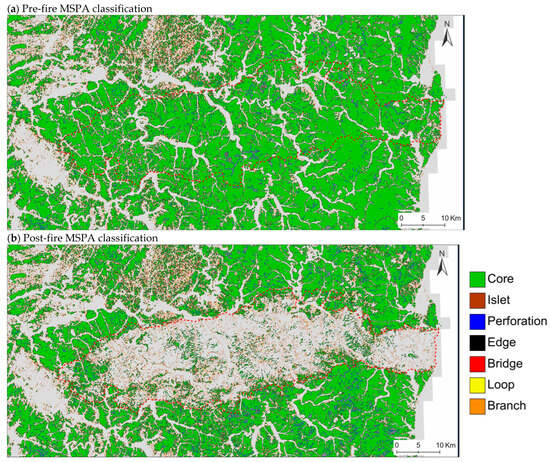

MSPA revealed significant structural changes in forest habitats (Table 2, Figure 3). Core area decreased by 34% across the study region and by 84% within the fire boundary (Table 2 and Table 3). Islet area increased by 144% region-wide and by 976% within the fire boundary (Table 2 and Table 3), indicating severe fragmentation of continuous core habitats.

Table 2.

Changes in MSPA landscape classes before and after forest fire.

Figure 3.

Spatial distribution of MSPA classes before and after forest fire in the study area. (a) Pre-fire MSPA classification showing continuous core habitats. (b) Post-fire landscape structure showing severe core fragmentation. Key transitions include: Core loss (red dashed boundary interior, −83.85%), Islet proliferation (+975.69%), and Edge expansion (+18.25%p). Quantitative changes for all classes are detailed in Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 3.

MSPA class changes within fire boundary region.

Significant changes were also observed in the connectivity structure. Bridge area increased by 302.40 ha (58.19%), from 519.70 ha before the fire to 822.10 ha after the fire. Loop area also increased by 98.20 ha (25.89%), from 379.36 ha to 477.56 ha (Table 2). Within the fire boundary, the increase in these connectivity structures, such as a 240.35% increase in Bridges (Table 3), appears paradoxical. However, this is interpreted as the fire causing Core fragmentation, which generated many small connected fragments. Despite the increase in Bridge and Loop areas, the size of the Core patches they connect decreased, and a qualitative decline occurred. Consequently, overall functional connectivity is judged to have deteriorated.

The Edge ratio increased by 4.16 percentage points, from 12.53% before the fire to 16.69% after the fire (Table 2). Within the fire boundary, this ratio surged by 18.25 percentage points from 10.65% to 28.90% (Table 3). This indicates that the fire reduced the internal forest area and increased the external edge effect.

The Core Area Index (the proportion of core areas within the entire forest) decreased by 12.52 percentage points, from 75.12% to 62.59% (Table 2). Particularly within the fire boundary, this index plummeted by 44.14 percentage points, from 79.06% to 34.92% (Table 3), indicating a severe deterioration in habitat quality. Conversely, the Connectivity Index (Bridge + Loop ratio) increased by 1.90 percentage points from 2.30% to 4.21% (Table 2), reflecting an increase in small connected fragments due to fragmentation. This structural change is assessed to have ultimately resulted in a decline in habitat quality and weakened functional connectivity.

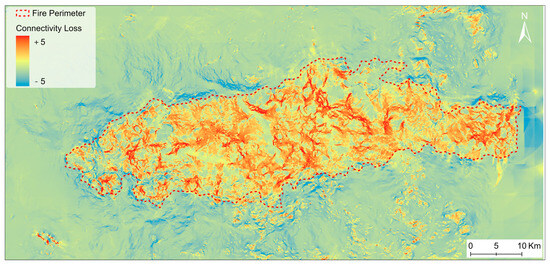

3.3. Results of Connectivity Loss After Forest Fire

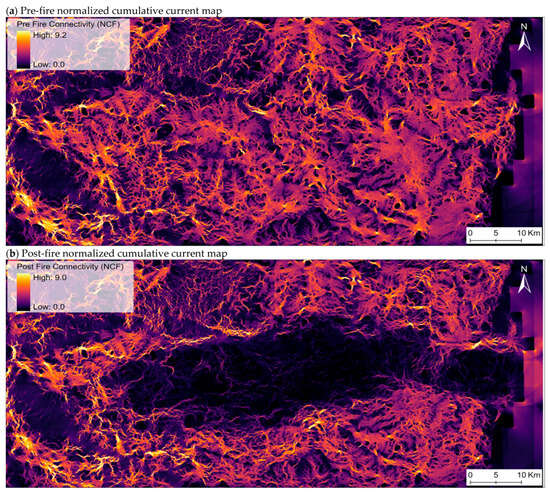

Analysis using Omniscape quantified changes in functional connectivity before and after the forest fire, revealing a significant reduction in connectivity across the entire study area (Table 4, Figure 4 and Figure 5). The average value of the normalized cumulative current map before the forest fire was 0.97, but it decreased to 0.84 after the forest fire, resulting in an average connectivity loss of 0.21 (12.9%).

Table 4.

Summary statistics of connectivity loss analysis for the study area.

Figure 4.

Normalized cumulative current maps before and after forest fire showing landscape connectivity patterns. Note: This figure presents the landscape-scale connectivity patterns quantified through Omniscape circuit theory modeling, illustrating normalized current flow intensity across the study area under pre-fire and post-fire landscapes. Panel (a) displays the pre-fire normalized cumulative current map, and Panel (b) shows the post-fire.

Figure 5.

Spatial distribution of connectivity loss across the study area. Note: This connectivity loss map reveals the heterogeneous spatial pattern of functional connectivity degradation caused by the forest fire, calculated as the pixel-wise difference between pre-fire and post-fire normalized cumulative current values.

Connectivity loss was spatially heterogeneous, with 39.9% of forest pixels showing reduced connectivity (mean loss: 0.21, max: 4.77). Within the fire boundary, connectivity decreased by 60% (Table 4).

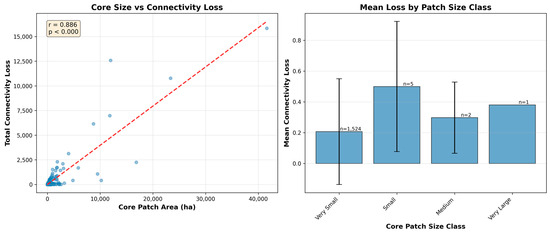

Analysis of connectivity loss per MSPA Core patch revealed a decrease in connectivity in 1532 (46.7%) of the total 3282 Core patches (Table 5, Figure 6). A strong positive correlation (r = 0.886, p < 0.001) was found between patch size and loss amount, indicating that larger Core patches experienced greater connectivity loss. The average loss per patch was calculated as 0.21. Within the forest fire boundary, loss occurred in 458 out of 520 patches (88.1%), showing an even stronger correlation with patch size (r = 0.994, p < 0.001).

Table 5.

Core patch statistics and connectivity loss by patch size.

Figure 6.

Relationship between Core patch size and connectivity loss.

Furthermore, analysis of connectivity loss by forest fire intensity (Table 6) revealed a tendency for connectivity loss to increase with higher forest fire intensity. Particularly within the ‘fire boundary’ area, regions with low-intensity damage (Low, 0.75) already exhibited high losses, and all regions with moderate–low-intensity damage (Moderate–Low, 0.81) or higher recorded high average loss values of 0.79 or above. This demonstrates that even low-intensity damage with dNBR values of 0.1 or higher significantly increases habitat resistance, severely impairing functional connectivity. Interestingly, even unburned areas within the fire boundary (Unburned, 0.61) showed much higher losses than unburned areas in the entire study region (0.11). This is interpreted as these unburned patches becoming isolated as surrounding areas transformed into high-resistance zones due to the fire.

Table 6.

Mean connectivity loss by fire severity class.

Scatter plot illustrating the strong positive correlation between MSPA core patch area (x-axis) and total normalized connectivity loss (y-axis). Each point represents one of 1532 core patches with measurable loss. The relationship is highly significant (r = 0.886, p < 0.001), with patch size explaining 78% of the variance in connectivity loss (r2 = 0.785).

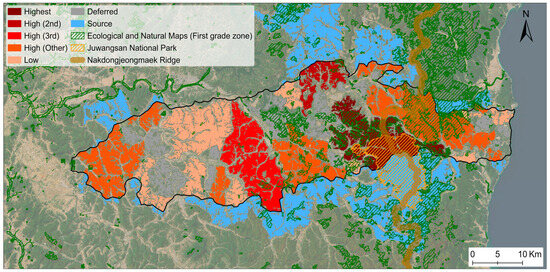

3.4. Restoration Priority Areas

The 53 patches classified as Core both before and after the forest fire were evaluated for restoration priority. Among these, 24 patches with no external remnant habitat outside the fire boundary were classified as Deferred. The 29 patches with external remnant habitat (the priority evaluation group) were finally classified as 14 High-priority and 15 Low-priority patches (Table 7, Figure 7).

Table 7.

Restoration priority classification based on restoration scale, source capacity, and network importance.

Figure 7.

Spatial distribution of restoration priority classes across fire-affected core habitats. The black line indicates the fire perimeter.

The total restoration area was calculated as 84,019.3 ha. High-priority patches accounted for 55,762.4 ha (66.4%), Low-priority patches for 15,934.1 ha (19.0%), and Deferred patches for 12,322.8 ha (14.7%).

High-priority patches (14 patches) had an average restoration size of 3983.0 ha, average source capacity of 3784.7 ha, and average network importance of 1.464. showing higher values across all indicators compared to Low-priority patches (average restoration size 1062.3 ha, average source capacity 178.4 ha, average network importance 1.412).

The top-priority patch exhibited the largest scale with a restoration area of 11,390.8 ha and a source capacity of 19,832.8 ha. The area where this patch is located was identified as a spatially overlapping zone of Juwangsan National Park, Grade 1 Ecological Natural Areas, and the Nakdong Ridge. The second-priority patch had a restoration area of 3304.9 ha and a source capacity of 11,049.4 ha, demonstrating excellent individual supply capacity to surrounding areas. The third-priority patch showed the second-largest scale with a restoration area of 10,735.2 ha.

Low priority patches were assessed as having limited potential to enhance connectivity with surrounding habitats during restoration due to their relatively small restoration scale and low source capacity. Deferred patches had the smallest average restoration scale at 513.4 ha and were judged to have difficulty achieving independent recovery as no residual habitat remains outside the fire boundary.

4. Discussion

4.1. Changes in Landscape Structure and Loss of Functional Connectivity Following Forest Fires

The forest fire acted as a complex disturbance, causing both structural fragmentation (84% core loss, 976% islet increase within fire boundary) and functional disconnection (60% current flow loss). Notably, the strong correlation between patch size and connectivity loss (r = 0.886) indicates that larger cores, which likely served as network hubs, suffered disproportionate impacts. Furthermore, unburned patches within the fire perimeter experienced significant connectivity loss (mean: 0.61) despite no direct damage, demonstrating that isolation effects extend beyond burned areas. The abrupt increase in Edge and Islet proportions (Edge: +18.25%p, Islet: +9.70%p within fire boundary) may exacerbate edge effects, potentially leading to altered microclimates, increased vulnerability to invasive species, and elevated predation pressure. These findings highlight that fire impacts on connectivity cannot be assessed solely by examining damaged areas.

4.2. Interpretive Implications of the MSPA–Omniscape Integrated Analysis

The MSPA-Omniscape integration addresses the complementary limitations of each method. MSPA’s paradoxical increase in Connectivity Index (+1.9%p after fire) illustrates its limitation: this reflects an increase in small structural fragments from core fragmentation, not functional improvement. Conversely, Omniscape alone lacks explicit structural context for defining habitat cores. By using MSPA-derived cores as Omniscape sources and incorporating fire damage intensity into resistance surfaces, this integration ensures both structural validity and functional realism.

The integrated analysis revealed that while some post-fire core connections were completely severed, weak diffuse flow persisted in areas with relatively low resistance around remaining cores. This finding has important restoration implications: focusing solely on damaged areas would yield limited network recovery, as functional connectivity depends on linkages between cores. Consequently, effective restoration should prioritize re-establishing connectivity between cores through a composite approach that considers both structural continuity and functional flow pathways.

4.3. Spatial Implications of Restoration Priorities and Linkage with Protected Area Management

Restoration priority was calculated by integrating three indicators: restoration scale, core capacity, and network importance (current value). Applying this framework, ‘High’ priority areas were predominantly identified as patches adjacent to undamaged external cores. This spatial pattern is a direct outcome of incorporating source capacity as a key indicator: patches connected to larger external sources scored higher because source–sink theory predicts greater potential for population influx. It is important to note that this result reflects the application of our assessment criteria, not a comparative evaluation of alternative restoration sequences. Simulating specific restoration scenarios (e.g., prioritizing different spatial zones) would require assumptions about restoration timelines and ecological responses that extend beyond the current framework, representing a potential direction for future research.

Notably, as confirmed in the results, the top-priority patch is located within Juwangsan National Park, an area where Grade 1 Ecological Natural Areas and the Nakdong Ridge spatially overlap. Grade 1 Ecological Natural Areas are defined under Article 34 of the Natural Environment Conservation Act as key habitats for endangered wildlife, major ecological corridors and pathways, and areas with particularly outstanding ecosystems. The Nakdong Ridge is a major forest axis in southern Korea, branching off from the Baekdudaegan Range and extending southward. The spatial alignment of these core protected areas, ecological corridors, and top-priority patches demonstrates the region’s pivotal role in restoring ecological connectivity.

Furthermore, the study area is a core section of the national ecological corridor formed along the major forest axis in southern Korea, serving as a connecting link between the Nakdong Ridge and the Baekdudaegan Mountain Range. This area is designated as a core connecting section of the southern forest axis in Korea’s Third Ecological Corridor Conservation and Restoration Plan (2024–2028) [41]. It is managed as a protected area and ecological corridor management zone, playing a vital role in maintaining migration pathways for endangered wildlife and the continuity of ecosystem services. Therefore, the structural disruption caused by this forest fire could impact the continuity of the entire Korean Peninsula’s ecological network, extending beyond mere local damage.

Accordingly, restoration efforts must be pursued at spatial scales transcending administrative boundaries and designed to complement the functions of existing protected areas. For instance, designating buffer zones between core and peripheral protected areas as restoration hubs can expand the habitat conservation functions of existing protected areas to focus on connectivity.

4.4. Limitations of the Study and Future Tasks

Future research requires the following improvements. First, the Omniscape model did not explicitly consider species-specific characteristics. While the radius parameter was set based on medium-to-large mammals, different species possess varying movement capabilities and habitat preferences. Future studies require a multi-species approach or focal species-based analysis.

Second, this study focused on spatial connectivity but did not sufficiently consider temporal dynamics. Connectivity will also change gradually during post-fire vegetation recovery, necessitating long-term monitoring and time-series analysis. In particular, tracking studies spanning 2–3 years are needed to distinguish areas undergoing natural recovery from those requiring artificial restoration.

Third, some subjectivity may be involved in setting resistance surfaces. Resistance values by land cover type were set based on literature, but actual movement preferences of organisms may vary by species. Follow-up research combining GPS tracking data or genetic analysis data is needed to validate and calibrate resistance surfaces.

Fourth, the analysis of restoration effectiveness did not sufficiently consider practical constraints such as land ownership status (e.g., public vs. private land), actual restoration costs, and topographical accessibility. Future research requires integrated analysis combining ecological priority with socioeconomic feasibility.

Finally, given the increasing frequency and intensity of forest fires due to recent climate change, restored areas may become vulnerable to forest fires again. Therefore, restoration strategies considering resilience are required. While this study analyzed a single forest fire event, subsequent research needs to consider long-term and cumulative impacts.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that integrating MSPA and Omniscape enables simultaneous assessment of structural fragmentation and functional connectivity loss following forest fires. The source–sink-based priority framework identified patches with high recolonization potential based on their connectivity to undamaged source habitats. The spatial overlap of high-priority patches with Juwangsan National Park, the Nakdong Ridge, and Grade 1 Ecological Natural Areas underscores the importance of linking site-level restoration to national ecological corridor management. This framework provides a transferable approach for connectivity-based restoration prioritization applicable to various disturbance contexts beyond forest fires.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C. and S.L.; methodology, H.S. and C.C.; software, C.C.; validation, C.C., S.L. and H.S.; formal analysis, C.C.; investigation, S.L.; data curation, C.C. and H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.C. and H.S.; writing—review and editing, H.S.; visualization, C.C.; supervision, C.C. and H.S.; project administration, C.C. and H.S.; funding acquisition, H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Institute of Ecology (No. NIE-B-2025-18).

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study contain sensitive environmental and spatial information related to protected areas and wildlife habitats. Therefore, the datasets cannot be made publicly available in order to comply with national environmental data protection regulations. Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Processed spatial datasets (e.g., dNBR, MSPA, and Omniscape outputs) can also be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bowman, D.M.J.S.; Balch, J.K.; Artaxo, P.; Bond, W.J.; Carlson, J.M.; Cochrane, M.A.; D’Antonio, C.M.; DeFries, R.S.; Doyle, J.C.; Harrison, S.P.; et al. Fire in the Earth System. Science 2009, 324, 481–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pausas, J.G.; Keeley, J.E. Wildfires as an Ecosystem Service. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2019, 17, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, W.M.; Cochrane, M.A.; Freeborn, P.H.; Holden, Z.A.; Brown, T.J.; Williamson, G.J.; Bowman, D.M. Climate-Induced Variations in Global Wildfire Danger from 1979 to 2013. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenmayer, D.B.; Fischer, J. Habitat Fragmentation and Landscape Change: An Ecological and Conservation Synthesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; ISBN 1-59726-606-X. [Google Scholar]

- Loehman, R.A.; Keane, R.E.; Holsinger, L.M. Simulation Modeling of Complex Climate, Wildfire, and Vegetation Dynamics to Address Wicked Problems in Land Management. Front. For. Glob. Change 2020, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.G.; Braziunas, K.H.; Hansen, W.D.; Harvey, B.J. Short-Interval Severe Fire Erodes the Resilience of Subalpine Lodgepole Pine Forests. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 11319–11328. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Korea Forest Service. 2025 Yeongnam Region Wildfire Damage Assessment; Korea Forest Service: Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2025.

- Taylor, P.D.; Fahrig, L.; Henein, K.; Merriam, G. Connectivity Is a Vital Element of Landscape Structure. Oikos 1993, 68, 571–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooks, K.R.; Sanjayan, M. Connectivity Conservation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; Volume 14, ISBN 1-139-46020-X. [Google Scholar]

- Fahrig, L. Effects of Habitat Fragmentation on Biodiversity. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2003, 34, 487–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankham, R. Genetics and Extinction. Biol. Conserv. 2005, 126, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura, S.; Pascual-Hortal, L. A New Habitat Availability Index to Integrate Connectivity in Landscape Conservation Planning: Comparison with Existing Indices and Application to a Case Study. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 83, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilty, J.; Worboys, G.L.; Keeley, A.; Woodley, S.; Lausche, B.J.; Locke, H.; Carr, M.; Pulsford, I.; Pittock, J.; White, J.W. Guidelines for Conserving Connectivity Through Ecological Networks and Corridors; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2020.

- Woo, D.G. A Study on Ecological Characteristics and Conservation of Yellow-Throated Marten. Ph.D. Thesis, Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Soille, P.; Vogt, P. Morphological Segmentation of Binary Patterns. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2009, 30, 456–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Choi, C.; Lee, S.; Kim, J. Analysis of Ecological Connectivity of Forest Habitats Using Spatial Morphological Characteristics and Roadkill Data. Korean J. Ecol. Environ. 2024, 57, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, B.H.; Dickson, B.G.; Keitt, T.H.; Shah, V.B. Using Circuit Theory to Model Connectivity in Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation. Ecology 2008, 89, 2712–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, V.A.; Shah, V.B.; Anantharaman, R.; Hall, K.R. Omniscape.jl: Software to Compute Omnidirectional Landscape Connectivity. J. Open Source Softw. 2021, 6, 2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belote, R.T.; Barnett, K.; Zeller, K.; Brennan, A.; Gage, J. Examining Local and Regional Ecological Connectivity throughout North America. Landsc. Ecol. 2022, 37, 2977–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, B.G.; Albano, C.M.; Anantharaman, R.; Beier, P.; Fargione, J.; Graves, T.A.; Gray, M.E.; Hall, K.R.; Lawler, J.J.; Leonard, P.B. Circuit-theory Applications to Connectivity Science and Conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2019, 33, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Cillero, R.; Siggery, B.; Murphy, R.; Perez-Diaz, A.; Christie, I.; Chimbwandira, S.J. Functional Connectivity Modelling and Biodiversity Net Gain in England: Recommendations for Practitioners. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 328, 116857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindlmann, P.; Burel, F. Connectivity Measures: A Review. Landsc. Ecol. 2008, 23, 879–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushman, S.A.; McRae, B.; Adriaensen, F.; Beier, P.; Shirley, M.; Zeller, K. Biological Corridors and Connectivity. In Key Topics in Conservation Biology 2; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 384–404. [Google Scholar]

- Keeley, A.T.; Beier, P.; Creech, T.; Jones, K.; Jongman, R.H.; Stonecipher, G.; Tabor, G.M. Thirty Years of Connectivity Conservation Planning: An Assessment of Factors Influencing Plan Implementation. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 103001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulliam, H.R. Sources, Sinks, and Population Regulation. Am. Nat. 1988, 132, 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brawn, J.D.; Robinson, S.K. Source-Sink Population Dynamics May Complicate the Interpretation of Long-Term Census Data. Ecology 1996, 77, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foppen, R.P.; Chardon, J.P.; Liefveld, W. Understanding the Role of Sink Patches in Source-sink Metapopulations: Reed Warbler in an Agricultural Landscape. Conserv. Biol. 2000, 14, 1881–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donovan, T.M.; Thompson, F.R., III; Faaborg, J.; Probst, J.R. Reproductive Success of Migratory Birds in Habitat Sources and Sinks. Conserv. Biol. 1995, 9, 1380–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.; Smith, H.; Green, R.; Wasser, S.; Purcell, K. Fisher Use of Postfire Landscapes: Implications for Habitat Connectivity and Restoration. West. N. Am. Nat. 2021, 81, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, B.H.; Hall, S.A.; Beier, P.; Theobald, D.M. Where to Restore Ecological Connectivity? Detecting Barriers and Quantifying Restoration Benefits. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e52604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D.J.; Fuller, A.K.; Proulx, G. Martens and Fishers (Martes) in Human-Altered Environments: An International Perspective; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; ISBN 0-387-22580-3. [Google Scholar]

- Key, C.; Benson, N. Landscape Assessment: Ground Mea-Sure of Severity, the Composite Bum Index, and Remote Sens-Ing of Severity, the Normalized Bum Ratio FIREMON: Fire Effects Monitoring and Inventory System; Gen Tech Rep RMRS-GTR-164; USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: Ogden, UT, USA, 2006.

- Baek, S.; Lim, J.; Kim, W. Analysis on the Fire Progression and Severity Variation of the Massive Forest Fire Occurred in Uljin, Korea, 2022. Forests 2022, 13, 2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Son, S.; Bae, J.; Park, S.; Seo, J.; Seo, D.; Lee, Y.; Kim, J. Single-Temporal Sentinel-2 for Analyzing Burned Area Detection Methods: A Study of 14 Cases in Republic of Korea Considering Land Cover. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeller, K.A.; McGarigal, K.; Whiteley, A.R. Estimating Landscape Resistance to Movement: A Review. Landsc. Ecol. 2012, 27, 777–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson-Holt, C.; Watts, K.; Bellamy, C.; Nevin, O.; Ramsey, A. Defining Landscape Resistance Values in Least-Cost Connectivity Models for the Invasive Grey Squirrel: A Comparison of Approaches Using Expert-Opinion and Habitat Suitability Modelling. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, T.Y.; Yang, B.G.; Woo, D.G. The Suitable Types and Measures of Wildlife Crossing Structures for Mammals of Korea. J. Environ. Impact Assess. 2012, 21, 209–218. [Google Scholar]

- Vogt, P.; Riitters, K.H.; Estreguil, C.; Kozak, J.; Wade, T.G.; Wickham, J.D. Mapping Spatial Patterns with Morphological Image Processing. Landsc. Ecol. 2007, 22, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, K.A.; Macdonald, S.E.; Burton, P.J.; Chen, J.; Brosofske, K.D.; Saunders, S.C.; Euskirchen, E.S.; Roberts, D.; Jaiteh, M.S.; Esseen, P. Edge Influence on Forest Structure and Composition in Fragmented Landscapes. Conserv. Biol. 2005, 19, 768–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezanson, J.; Edelman, A.; Karpinski, S.; Shah, V.B. Julia: A Fresh Approach to Numerical Computing. SIAM Rev. 2017, 59, 65–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Environment. Korean Peninsula Ecological Corridor Conservation and Restoration Plan (Phase 3, 2024–2028); Ministry of Environment: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2024.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).