How Has South Africa’s Land Reform Policy Performed from 1994 to 2024? Insights from a Review of Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

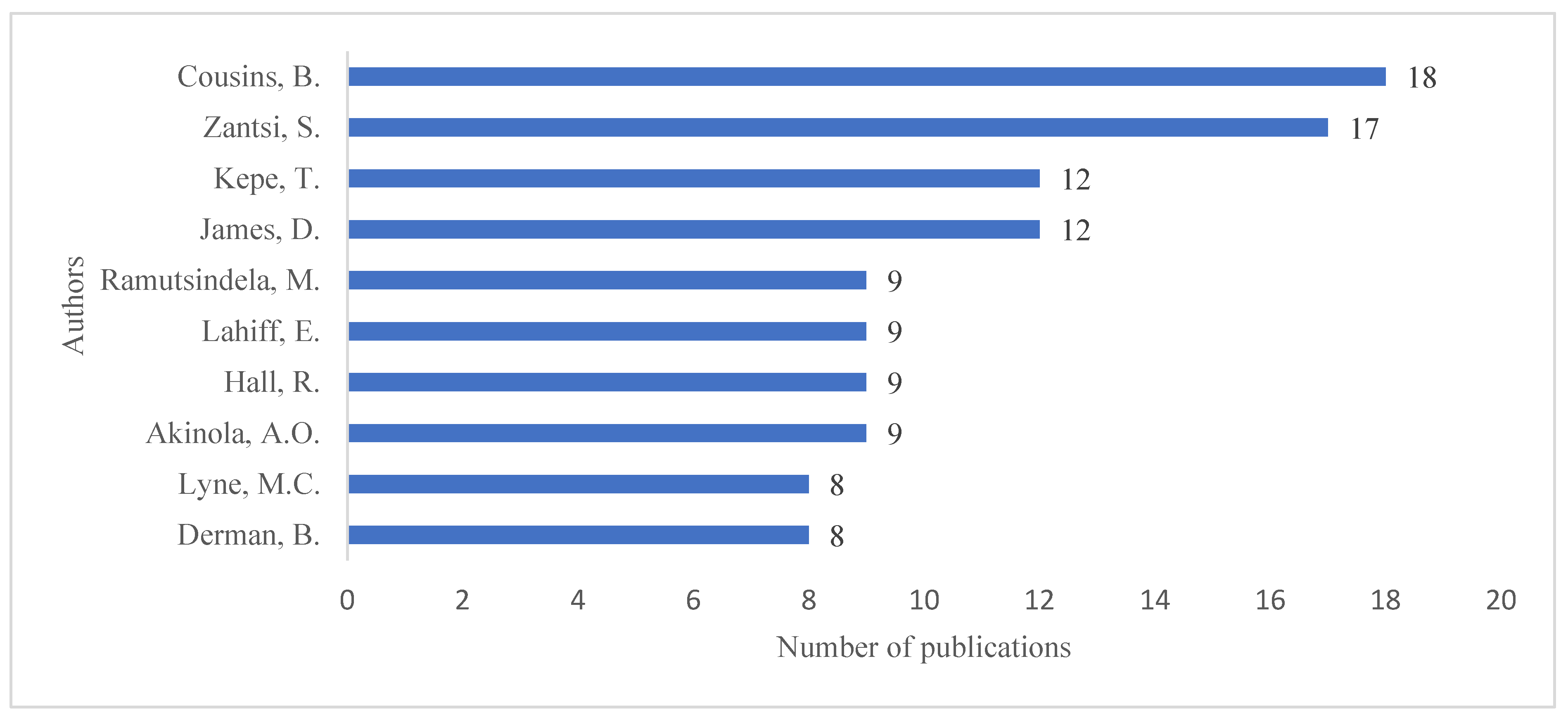

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Sourcing of Literature

3. Results and Synthesis of Literature

3.1. Performance of the South African Land Reform Policy

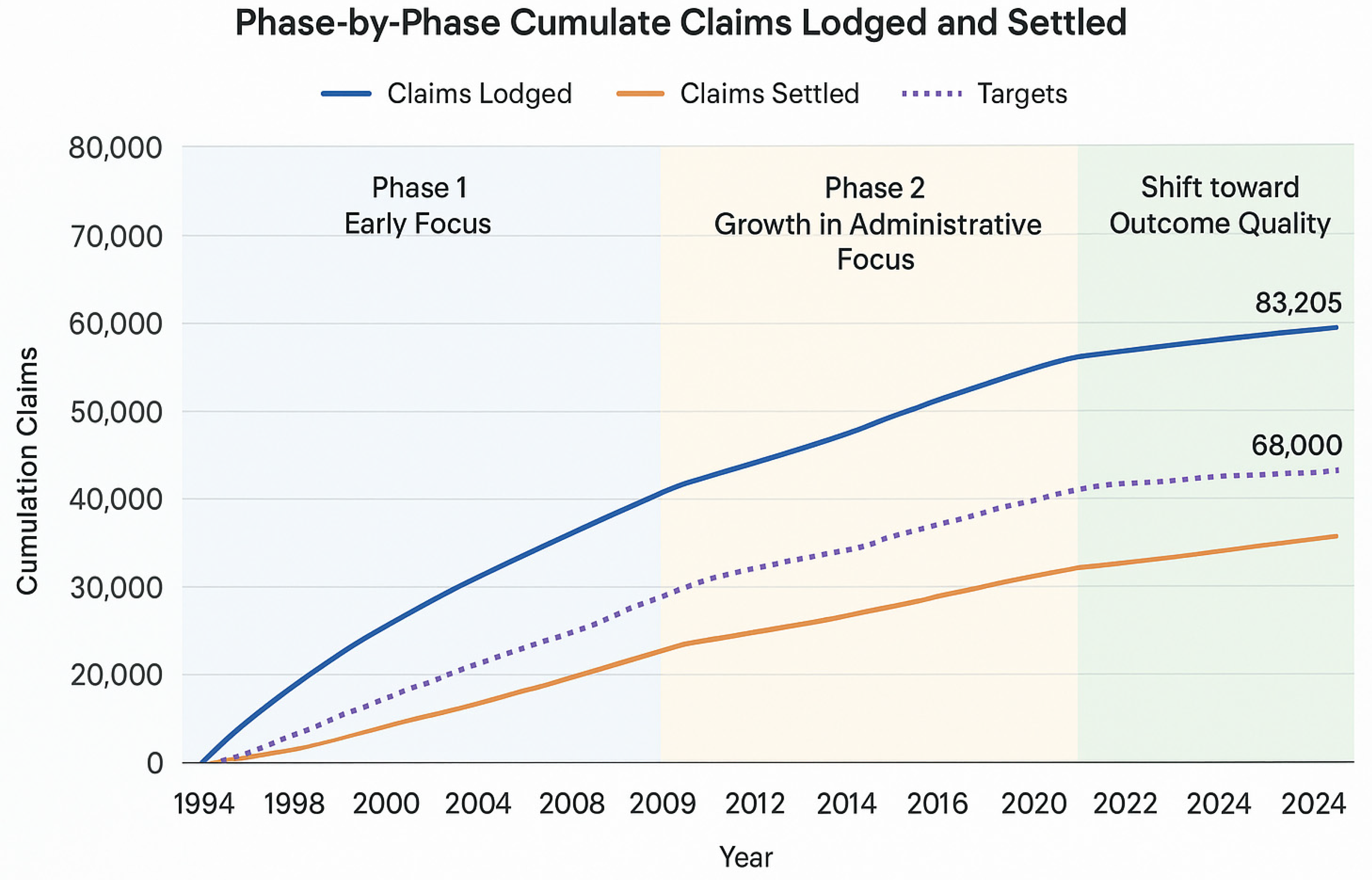

Land Restitution

3.2. Phase 1: Early Claims and Settlements (1994–2009)

3.3. Phase 2: Growth in Administrative Focus (2010–2020)

3.4. Phase 3: Shift Toward Outcome Quality (2021–2024)

3.5. Land Redistribution

3.6. Land Tenure

3.7. Tenure Security on Redistributed Land

3.8. Tenure Security on Restituted Land

3.9. Progress for Rural Women

3.10. Determinants and Outcomes of Tenure Security

3.11. Policy and Measurement Challenges

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison of Conditions Before and After Land Reform

4.2. There Are Key Lessons from Other Countries That South Africa Can Consider

4.3. Limitations of the Study and Future Research

5. Conclusions

6. Recommendations

- (1)

- Strengthen tenure security—issue title deeds for redistributed land within a defined timeframe, with safeguards like the state’s right of first refusal to prevent speculative resale.

- (2)

- Improve post-settlement support—provide structured support for five years, including infrastructure, credit access, training, and market linkages.

- (3)

- Enhance institutional coordination—establish an integrated land reform management system with clear accountability and performance monitoring.

- (4)

- Address gender inequities—enforce gender quotas and targeted capacity-building for women farmers.

- (5)

- Ensure data transparency—create a centralized, publicly accessible database tracking transfers, beneficiaries, and outcomes.

- (6)

- Engage communities—harmonize statutory and customary governance through participatory frameworks promoting equity and transparency.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mabin, A. Dispossession, Exploitation and Struggle: An Historical Overview of South African Urbanization. In The Apartheid City and Beyond; Routledge: London, UK, 2003; pp. 12–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ngcukaitobi, T. Land Matter; Penguin Random House South Africa: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2021; Available online: https://www.penguinrandomhouse.co.za/book/land-matters-south-africa%E2%80%99s-failed-land-reforms-and-road-ahead/9781776095971 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Jacobs, P.; Lahiff, E.; Hall, R. Land Redistribution; Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS): Cape Town, South Africa, 2003; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10566/4423 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Mbatha, M.W.; Mlambo, V.H.; Mubecua, M.A. Apartheid legacies on South Africa’s agricultural sector: A sustainable livelihood approach. Artha J. Soc. Sci. 2022, 21, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Land Affairs. Land Reform|South African Government; Government of South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2016. Available online: https://www.gov.za/issues/land-reform (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (South Africa). Strategic Plan 2013–2018; Government of South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2013. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201501/daff-strategic-plan-2013-2014-2017-2018.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Department of Land Affairs (DLA). South African Land Policy White Paper; Government of South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 1997. Available online: https://www.gov.za/documents/white-papers/south-african-land-policy-white-paper-01-apr-1997 (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Mostert, H. Land restitution, social justice and development in South Africa. S. Afr. Law J. 2002, 119, 400. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development (DALRRD). Annual Report 2018/19; Government of South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2018. Available online: https://www.dalrrd.gov.za (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Cousins, B. Land reform in South Africa is failing. Can it be saved? Transformation 2016, 92, 135–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parliament of South Africa. Diagnostic Report on Land Reform in South Africa; Parliament of South Africa: Cape Town, South Africa, 2017. Available online: https://www.parliament.gov.za/storage/app/media/Pages/2017/october/High_Level_Panel/Commissioned_Report_land/Diagnostic_Report_on_Land_Reform_in_South_Africa.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation (DPME). Diagnostic Research to Determine the Reasons for Failure of Land Reform Projects; Government of South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2025. Available online: https://www.dpme.gov.za/publications/research/strategic%20research%20assignmentS/31.03.2025_Land%20reform%20synthesis%20report.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Masoka, N.S. Post-Settlement Land Reform Challenges: The Case of the Department of Agriculture, Rural Development and Land Administration, Mpumalanga Province. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Mpumalanga, Mbombela, South Africa, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tshigomana, T.S. Post-Settlement Challenges on Land Restitution Beneficiaries in the Vhembe District. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Venda, Thohoyandou, South Africa, 2021. Available online: https://univendspace.univen.ac.za/items/00c8e32b-8012-4c9f-a5f0-3d19f96fe4e1 (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Gumata, N.; Ndou, E. Accelerated Land Reform, Mining, Growth, Unemployment and Inequality in South Africa: A Case for Bold Supply-Side Policy Interventions; Springer Nature AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Makhetha, E. Rural livelihoods and land reform in South Africa: An intersectional perspective on women lived experiences. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2025, 10, 100234. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2590291124002341 (accessed on 1 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Jankielsohn, R.; Duvenhage, A. Radical Land Reform In South Africa—A comparative perspective? South. J. Contemp. Hist. 2017, 42, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, B. More than socially embedded: The distinctive character of ‘communal tenure’ regimes in South Africa and its implications for land policy. J. Agrar. Change 2007, 7, 281–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepe, T.; Ramutsindela, M. Poverty and natural resources in the rural areas of South Africa. Dev. S. Afr. 2012, 29, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zantsi, S.; Mack, G.; Möhring, A.; Cloete, K.; Greyling, J.C.; Mann, S. South Africa’s land redistribution: An agent-based model for assessing structural and economic impacts. Agrekon 2025, 64, 93–112. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03031853.2025.2509488 (accessed on 2 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Chitonge, H. Resettled but not redressed: Land restitution and post-settlement dynamics in South Africa. J. Agrar. Change 2022, 22, 722–739. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/joac.12493 (accessed on 2 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Government Gazette. Restitution of Land Rights Act. 1994. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/act22of1994.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Government Gazette. Extension of Security of Tenure Act. 1997. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/a62-97.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Mkhongi, F.A.; Musakwa, W. Trajectories of deagrarianization in South Africa—Past, current and emerging trends: A bibliometric analysis and systematic review. Geogr. Sustain. 2022, 3, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, A.A.; Nurmandi, A.; Tenario, C.B.; Rahayu, R.; Benectitos, S.H.; Mina, F.L.P.; Haictin, K.M. Bibliometric analysis of trends in theory-related policy publications. Emerg. Sci. J. 2021, 5, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandidzanwa, C.; Verschoor, A.J.; Sacolo, T. Evaluating Factors Affecting Performance of Land Reform Beneficiaries in South Africa. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mfune, W. Land Reform in South Africa: The Issues and Challenges—Ideology, Politics and Post-Settlement Support Services. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, R. A political economy of land reform in South Africa. Rev. Afr. Political Econ. 2004, 31, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihlobo, W. South Africa Is Making Progress with Its Land Reform. Wandile Sihlobo Blog. 2024. Available online: https://wandilesihlobo.com/2024/12/09/south-africa-is-making-progress-with-its-land-reform/ (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Netshipale, A.J.; Oosting, S.J.; Raidimi, E.N.; Mashiloane, M.L.; De Boer, I.J.M. Land reform in South Africa: Beneficiary participation and impact on land use in the Waterberg District. NJAS—Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2017, 83, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjale, M.M.; Mwale, M.; Kilonzo, B.M. Can restitution change lives of farm beneficiaries? Case of Waterberg district municipality, South Africa. Suid-Afr. Tydskr. Vir Landbouvoorligt./S. Afr. J. Agric. Ext. 2022, 50, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.R.; May, J. Poverty, livelihood and class in rural South Africa. World Dev. 1999, 27, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission on Restitution of Land Rights Annual Report: Briefing; Parliamentary Monitoring Group: Pretoria, South Africa, 2024; Available online: https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/5255/ (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Department of Agriculture (Republic of South Africa). Annual Report 1999; Department of Agriculture: Pretoria, South Africa, 1999.

- Kepe, T.; Hall, R. Land Redistribution in South Africa: Towards Decolonisation or Recolonisation? Politikon 2018, 45, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Rural Development and Land Reform. 2007. Land Audit Report. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201802/landauditreport13feb2018.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Ranchod, V. Land Reform in South Africa: A General Overview and Critique. Ph.D. Thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rugege, S. Land reform in South Africa: An overview. Int. J. Leg. Inf. 2004, 32, 283–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minister of Agriculture and Land Affairs. Land Redistribution for Agricultural Development: A Sub-Programme of the Land Redistribution Programme. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/land-redistribution-agricultural-development.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Lahiff, E.; Cousins, B. Smallholder Agriculture and Land Reform in South Africa. 2005. Available online: https://uwcscholar.uwc.ac.za/items/86606854-f6ac-4406-9f7a-a173ea1c7a00 (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- South African Regional Poverty Network (SARPN). SARPN—South Africa. 2020. Available online: https://www.sarpn.org/documents/d0001822/index.php (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Anseeuw, W.; Mathebula, N. Land Reform and Development: Evaluating South Africa’s Restitution and Redistribution Programmes. 2008. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254389747_Land_Reform_and_Development_Evaluating_South_Africa%27s_Restitution_and_Redistribution_Programmes (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Mabuza, N.N. Socio-Economic Impact of Land Reform Projects Benefitting from the Recapitalisation and Development Programme in South Africa. Master’s Thesis, University of Pretoria (South Africa), Pretoria, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mtero, F.; Gumede, N.; Ramantsima, K. Elite capture in South Africa’s land redistribution: The convergence of policy bias, corrupt practices and class dynamics. J. S. Afr. Stud. 2023, 49, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government Gazette. Communal Land Rights Act. 2004. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/a11-041.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- van Huffel, A.L.S. State regulation and misconstructions of customary land tenure in South Africa. Afr. Hum. Rights Law J. 2024, 24, 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihlobo, W. BizNews: SA Govt. Is Hoarding 2,5 Million Hectares of Land Acquired Under Land Redistribution. 2025. Available online: https://iono.fm/e/1566964 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Makhetha, E.; Hart, T. Hunger for farmland among female farmers in Limpopo Province: Bodies, violence and land. Agenda 2018, 32, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zantsi, S. Profiling Potential Land Redistribution Beneficiaries In South Africa: Implications for Agricultural Extension and Policy Design. S. Afr. J. Agric. Ext. 2019, 47, 35–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kingwill, R. Land and Property Rights: ‘Title Deeds as Usual’ Won’t Work. Econ3 × 3. 2017. Available online: https://www.econ3x3.org/article/land-and-property-rights-title-deeds-usual-wont-work (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Yacim, J.; Grace Merafe, B.; Zulch, B.; Paradza, P. Assessing Land Management Strategies and Social Implications of PLAS Beneficiaries in Mahikeng, South Africa. 2023. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/afr/wpaper/afres2023-009.html (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Amoah, C.; Tyekela, N. The socio-economic impact of land redistribution on the beneficiaries in the Greater Kokstad Municipality of South Africa. Prop. Manag. 2021, 39, 653–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allsobrook, C. Tenure rights recognition in South African land reform. S. Afr. J. Philos. 2019, 38, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.E. Land reform for a landless chief in South Africa: History and land restitution in KwaZulu-Natal. Afr. Stud. Rev. 2021, 64, 884–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntshakala, T. Farm Evictions and Increasing Rural Local Municipal Responsibilities in Submission for the Division of Revenue: Technical Report 2017/2018; Financial and Fiscal Commission: Midrand, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, M. The everyday violence of eviction. Agenda 2018, 32, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, D. Going for Broke: The Fate of Farm Workers in Arid South Africa; HSRC Press: Cape Town, South Africa, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew, N. South Africa’s land ownership system as a barrier to social transformation. Rev. Int. Étud. Dév. 2020, 243, 233–261. [Google Scholar]

- Marais, L.; Lenka, M. Urban housing for rural peasants: Farmworker housing in South Africa. Dev. S. Afr. 2021, 38, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Human Settlement. Annual Report 2014/15 Municipality Profile, Stellenbosch Municipality; Western Cape Provincial Government: Cape Town, South Africa, 2014.

- Qayiso, O.; Modiba, F.S. How has South Africa’s land redistribution program improved women’s livelihoods? Russ. J. Agric. Socio-Econ. Sci. 2021, 118, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuzwayo, N.; Chipungu, L.; Magidimisha, H.H.; Lewis, M. Examining women’s access to rural land in UMnini Trust traditional area of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Town Reg. Plan. 2019, 75, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngarava, S. Implications of land restitution as a Transformative Social Policy for Water-Energy-Food (WEF) insecurity in Magareng Local Municipality, South Africa. Land Use Policy 2023, 133, 106878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development. Annual Performance Plan. 2025. Available online: https://static.pmg.org.za/DALRRD_2024-25_final_APP.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Mubecua, M.A.; Nojiyeza, S. Land expropriation without compensation: The challenges of Black South African women in land ownership. J. Gend. Inf. Dev. Afr. 2019, 8, 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Commission For Gender Equality. Do Women Reap What They Sow? The Experiences of Women Farm Workers. 2024. Available online: https://cge.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Women-Farmworkers-Report-Final-1.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Phuhlisani, N. Tenure Security of Farm Workers and Dwellers. 2017. Available online: https://www.parliament.gov.za/storage/app/media/Pages/2017/october/High_Level_Panel/Commissioned_Report_land/Commissioned_Report_on_Tenure_Security_Phuhlisani_NPC.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Pheko, L.L. Women, land and livelihoods in South Africa’s land reform programme. Policy Brief Policy Anal. Programme 2014, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, M.; Ferrer, S. Farm Workers’ Living and Working Conditions in South Africa: Key Trends, Emergent Issues, and Underlying and Structural Problems a Report Prepared by The Pretoria Office of the International Labour Organization. 2015. Available online: https://static.pmg.org.za/3/160127report.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Pienaar, G. Land Tenure Security: The Need for Reliable Land Information. 2013. Available online: https://hsf.org.za/publications/focus/focus-70-on-focus/focus-70-oct-g-pienaar.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Twala, C.; Vhiga, H.L. Pitfalls of PTOs in land ownership and control: Rethinking access for rural development in South Africa. Interdiscip. J. Rural Community Stud. 2024, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudhara, M.; Chitja, J.; Sahadeva, A. Application of Research Findings to Support Empowerment of Women for Irrigated Food Production and Improved Household Food Production; Water Research Commission: Pretoria, South Africa, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lahiff, E.; Li, G. Agricultural Land Redistribution and Land Administration in Sub-Saharan Africa: Case Studies of Recent Reforms; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkonen, A. Examining sources of land tenure (in)security. A focus on authority relations, state politics, social dynamics and belonging. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelder, J.L. What tenure security? The case for a tripartite view. Land Use Policy 2009, 27, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, T.-W.J.; Robinson, B.E.; Bellemare, M.F.; BenYishay, A.; Blackman, A.; Boucher, T.; Childress, M.; Holland, M.B.; Kroeger, T.; Linkow, B.; et al. Influence of land tenure interventions on human well-being and environmental outcomes. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 4, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaaga, F.A.; Hirons, M.A.; Malhi, Y. Questioning the link between tenure security and sustainable land management in cocoa landscapes in Ghana. World Dev. 2020, 130, 104913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doss, C.; Meinzen-Dick, R. Land tenure security for women: A conceptual framework. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, L.W.; Ontiri, E.; Alemu, T.; Moiko, S.S. Transcending landscapes: Working across scales and levels in pastoralist rangeland governance. Environ. Manag. 2017, 60, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, S.; Babalola, K.; Whittal, J. Theories of Land Reform and Their Impact on Land Reform Success in Southern Africa. Land 2019, 8, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliber, M.; Cousins, B. Livelihoods after Land Reform in South Africa. J. Agrar. Change 2013, 13, 140–165. [Google Scholar]

- Zantsi, S.; Nengovhela, R. The policy–practice gap: A comment on South Africa’s land redistribution. Dev. Pract. 2024, 34, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertus, M.; Popescu, B. Does Equalizing Assets Spur Development? Evidence From Large-Scale Land Reform in Peru. SSRN Electron. J. 2019, 15, 255–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsten, J.; Machtehe, C.; Ndlovu, T.; Lubambo, P. Performance of land reform projects in the Northwest province of South Africa: Changes over time and possible causes. Dev. S. Afr. 2016, 33, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbatha, N.C.; Muchara, B. Slow progress in South Africa’s Land Reform Process: Fear of Property Rights and Free Markets? J. Green Econ. Dev. 2015, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bjornlund, V.; Bjornlund, H.; van Rooyen, A.F. Exploring the factors causing the poor performance of most irrigation schemes in post-independence sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2020, 36 (Suppl. S1), S54–S101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. Rural land system reforms in China: History, issues, measures and prospects. Land Use Policy 2019, 91, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliber, M. Forms of agricultural support and the “culture of dependency and entitlement”. Agrekon 2019, 58, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahiff, E. Land Redistribution in South Africa: Progress to Date. 2007. Available online: https://sarpn.org/documents/d0002695/Land_Redistribution_South_Africa.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Wan, G.; Zhang, J.; Zuo, C. The Welfare Effects of Land Reform: Lessons from Yunnan, China. J. Dev. Stud. 2023, 59, 1608–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipenda, C. A Transformative Social Policy Perspective on Land and Agrarian Reform in Zimbabwe. Afr. Spectr. 2024, 59, 89–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narh, P.; Cosmas, L.; Sabbi, M.; Pham, V.; Nguyen, T. Land Sector Reforms in Ghana, Kenya and Vietnam: A Comparative Analysis of Their Effectiveness. Land 2016, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, A.F.; Rajabifard, A.; Shojaei, D. Undertaking land administration reform: Is there a better way? Land Use Policy 2023, 132, 106824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resosudarmo, I.A.P.; Tacconi, L.; Sloan, S.; Hamdani, F.A.U.; Subarudi Alviya, I.; Muttaqin, M.Z. Indonesia’s land reform: Implications for local livelihoods and climate change. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 108, 101903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phase & Years | Achieved | Not Achieved |

|---|---|---|

| Phase 1: Early Emphasis on Land Transfer (1994–2010) Goal: This period was about kick-starting redistribution |

|

|

| Phase 2: Broadening the Agenda (2010–2018): This phase saw expansion and diversity. |

|

|

| Phase 3: Accountability and Outcome-Driven Focus (2019–2024): This phase introduced monitoring, accountability, and justice debates, with a continued disconnect between policy and implementation and tangible outcomes. |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shiba, W.; Lungwana, M.; Abutaleb, K.; Mamabolo, M.; Mboweni, T.J.; Zantsi, S.; Matli, M.W.; Mdwebi, P.; Madyo, S.; Kubeka, P. How Has South Africa’s Land Reform Policy Performed from 1994 to 2024? Insights from a Review of Literature. Land 2025, 14, 2443. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122443

Shiba W, Lungwana M, Abutaleb K, Mamabolo M, Mboweni TJ, Zantsi S, Matli MW, Mdwebi P, Madyo S, Kubeka P. How Has South Africa’s Land Reform Policy Performed from 1994 to 2024? Insights from a Review of Literature. Land. 2025; 14(12):2443. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122443

Chicago/Turabian StyleShiba, Walter, Mamakie Lungwana, Khaled Abutaleb, Manana Mamabolo, Tribute Jabulile Mboweni, Siphe Zantsi, Mankaba Whitney Matli, Portia Mdwebi, Sipho Madyo, and Papi Kubeka. 2025. "How Has South Africa’s Land Reform Policy Performed from 1994 to 2024? Insights from a Review of Literature" Land 14, no. 12: 2443. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122443

APA StyleShiba, W., Lungwana, M., Abutaleb, K., Mamabolo, M., Mboweni, T. J., Zantsi, S., Matli, M. W., Mdwebi, P., Madyo, S., & Kubeka, P. (2025). How Has South Africa’s Land Reform Policy Performed from 1994 to 2024? Insights from a Review of Literature. Land, 14(12), 2443. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122443