Abstract

Against the backdrop of accelerating population aging, urban green spaces have become primary venues for elderly daily activities, with their winter thermal comfort emerging as a critical determinant of senior wellbeing. However, existing studies lack quantitative guidelines on how plant characteristics affect thermal comfort, limiting age-friendly design. Thirty representative landscape space sites (waterfront, square, dense forest, and sparse forest) in Beijing’s Zizhuyuan and Taoranting Parks were analyzed through microclimate measurements, 716 questionnaires, and scoring evaluations, supplemented by PET field data and ENVI-met simulations. A scoring system was developed based on tree density, plant traits (height, crown spread), and spatial features (canopy closure, structure, enclosure, and evergreen coverage). Key findings: (1) Sparse forests showed the best overall thermal comfort. Square building spaces were objectively comfortable but subjectively poor, while waterfront spaces showed the opposite. Dense forests performed worst in both aspects. (2) Wind speed and humidity were key drivers of both subjective and objective thermal comfort, and differences in plant configurations and landscape space types shaped how these factors were perceived. (3) Differentiated optimal scoring thresholds exist across the four landscape space types: waterfront (74 points), square building (52 points), sparse forest (61 points), and dense forest (88 points). (4) The landscape space design prioritizes sparse forest spaces, with moderate retention of waterfront and square areas and a reduction in dense forest zones. Optimization should proceed by first controlling enclosure and shading, then adjusting canopy closure and evergreen ratio, and finally refining tree traits to improve winter thermal comfort for the elderly. This study provides quantitative evidence and optimization strategies for improving both subjective and objective thermal comfort under diverse plant configurations.

1. Introduction

Population aging stands as one of the most significant trends of the 21st century. By 2050, the global population aged 60 and above is projected to rise to 20%. In 2024, China’s population aged 45–60 reached 330 million, accounting for 23.9% of the total, while those aged 60 and above numbered 310 million, representing 22.0%. As the reserve cohort for the elderly, middle-aged individuals are gradually entering a state of physical decline [1], with the incidence of related diseases steadily rising during this stage [2,3]. China’s aging presents characteristics of rapid progression, large scale, and pronounced advanced age. Over the next three decades, the nation will enter a period of accelerated deepening aging, with those aged 45 and above already entering the elderly stage. The Decision of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Further Comprehensively Deepening Reform and Advancing Chinese Modernization states, ‘Actively respond to population aging and improve policy mechanisms for developing elderly care services and industries’ [4]. This represents a major strategic deployment to implement a proactive national strategy for addressing population aging, grounded in China’s evolving demographic landscape.

The Central Urban Work Conference in July 2025 emphasized that urban development should prioritize creating comfortable and convenient livable cities [5]. Within China’s urbanization process, urban green spaces (UGS) serve as vital public activity areas, with their utilization efficiency ranking among key indicators of urban liveability. Against the backdrop of rapid population aging, the elderly have become the primary users of these spaces in daily life. Enhancing the comfort of UGS thus constitutes an effective strategy for building age-friendly cities that support healthy aging. Thermal comfort stands as a core factor influencing the overall comfort of UGS. Against the backdrop of concurrent urbanization and population aging in China, research has increasingly focused on how to design and optimize these spaces to enhance thermal comfort for elderly activities [6,7].

Research indicates that physiological changes result in significant differences in outdoor heat perception between elderly people and other age groups [8,9]. Furthermore, shifts in psychological states and declining cognitive abilities may impair their capacity to accurately and objectively assess thermal environments, making them less likely to adopt necessary adaptations to safeguard their health [10,11]. Consequently, against the backdrop of intensifying global climate change, elderly people face heightened risks of heat-related health issues.

In recent years, research into thermal comfort among the elderly has increasingly focused on examining psychological and physiological factors inherent to older adults themselves, alongside their environmental context. This research centers on investigating the relationships between age, meteorological factors, types and intensity of outdoor activities, and thermal comfort among the elderly [12,13], focused on thermal comfort indices (PET, PMV, UTCI) and related subjective metrics [14,15] (TAV, TCV, TSV, etc.) [16,17,18]. There is a lack of research that quantitatively classifies and compares the spatial characteristics of the environment from a design perspective, specifically lacking studies that explicitly explore the relationship between thermal comfort indicators for elderly people and the spatial features of UGS.

Regarding the creation and design optimization of comfortable urban green landscape spaces, some studies have focused on the role of plant elements within these spaces in enhancing ecological functions (such as regulating microclimate), increasing biodiversity, and creating aesthetically pleasing and functional landscape environments. These studies explore the benefits of different design approaches based on spatial characteristics of plant communities (such as canopy closure, tree–shrub–grass structure, plant enclosure, and evergreen ratio). overall plant community spatial characteristics (canopy closure, tree–shrub–grass structure, plant enclosure, evergreen ratio, etc.) [19,20,21,22]. Some studies have preliminarily assessed thermal comfort using plant elements, such as employing leaf area density (LAD), crown diameter (CD), and tree height (HT) as standards, and utilizing weighted outdoor thermal comfort autonomy (OTCAw) as a quantitative indicator of thermal comfort over time [23]. Others have explored the impact of different plant element combinations [24] and vegetation coverage [25] on thermal comfort.

A variety of mature software systems have been developed for outdoor microclimate and thermal comfort research, including ENVI-met, RayMan, SOLWEIG, and DUTE, which are widely applied to environmental assessments at multiple spatial scales, such as urban streets, parks, plazas, and building exterior spaces. ENVI-met is among the most commonly used three-dimensional dynamic microclimate models; it simulates energy exchanges among buildings, vegetation, and the atmosphere and is often employed to evaluate the effects of cooling, shading, and greening measures on the overall microclimate. RayMan, by contrast, is a radiation balance-based thermal comfort tool capable of rapidly calculating PET and other comfort indices through sky-view factor estimation and surrounding obstruction geometry, making it particularly suitable for detailed analyses of radiation and shading at specific observation points [26,27,28]. In landscape-scale thermal comfort research, the combined use of ENVI-met and RayMan is regarded as one of the most common and appropriate methodological approaches. ENVI-met provides a complete three-dimensional dynamic microclimate field at the landscape scale, enabling comparisons of how different vegetation structures and spatial configurations influence air temperature, humidity, wind patterns, and other microclimatic factors. RayMan, in turn, allows for detailed analysis of radiation, shading variations, and thermal comfort at key observation points, thereby offering a more realistic representation of users’ actual thermal experience at typical activity locations [29,30].

Existing research tends to focus on larger scales (e.g., cities, districts, neighborhoods, streets), lacking detailed design patterns for small-scale environments. Winter urban space studies are often confined to purely conventional thermal comfort factors like wind speed and humidity [31,32], while non-plant elements—such as building orientation, waterfront proximity, and site volume [33]—remain under-evaluated without established assessment systems. Furthermore, even when small-scale landscape features are studied, single quantitative metrics often replace the integrated coupling of plant elements within the overall landscape space [34,35]. For instance, when using Rayman for thermal comfort simulations, the Shrub Vegetation Function (SVF) is frequently used as the sole proxy for plant characteristics within the landscape space. Similarly, when employing Envi-met for site modeling, predefined plant types are often utilized. Consequently, reference standards for evaluating and optimizing plant community space (PCS) arrangements still remain insufficiently detailed [36,37,38,39]. Synthesizing the above research reveals that while studies incorporating plant elements to explore thermal comfort in winter urban parks exist, they predominantly focus on conventional thermal comfort factors. Although evaluation systems for plants have been developed, these tend to concentrate on plant characteristics themselves, lacking integrated systems that examine the relationship between plants and spatial context.

Moreover, for studies that focus on seasonal characteristics of thermal comfort, existing research has noted that in cold regions—such as the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei area in northern China—the mechanisms governing outdoor thermal comfort in winter differ markedly from those in summer [40,41]. During the cold season, people primarily face “cold discomfort” rather than heat-related stress. Nevertheless, vegetation within urban parks remains an unavoidable environmental element in the activity spaces used by older adults. For already built-up areas or locations where large-scale renovation is impractical, it is neither feasible nor reasonable to expect older adults to travel long distances to seek fully open, sun-exposed spaces for winter activities when suitable warm outdoor environments are lacking within their immediate surroundings [42]. In recent years, there has been a growing research interest in evaluating and optimizing thermal comfort in landscape spaces during the cold season. The central aim is to examine how, under existing vegetation configurations, different greening structures and spatial layouts can improve the local winter microclimate. Such studies seek to enable vegetated environments themselves to provide reasonable thermal comfort conditions in winter and to develop corresponding design recommendations, rather than requiring users to modify their behavior in order to accommodate unfavorable environmental conditions [43,44].

In light of this, the present study focuses on winter parks in Beijing where elderly people frequently gather. Accordingly, the research aims to address the following scientific questions and research objectives: (1) How do different landscape space types influence both the objective thermal environment (meteorological conditions, PET) and the subjective thermal perceptions (TSV, TCV, TAV, WSV, HSV) of elderly users? (2) Based on the evaluation results, what plant configuration optimization strategies can be proposed to support human-centered, age-friendly winter thermal comfort design in urban parks?

2. Methods

2.1. Study Area

The climate classification in this study follows the Köppen–Geiger system, where Beijing is Dwa: a typical warm temperate semi-humid continental monsoon climate, characterized by hot, rainy summers and cold, dry winters, with brief springs and autumns [45]. Strong winds frequently occur during winter and spring. The annual average temperature ranges between 10 and 12 °C. January averages −7 to −4 °C, while July averages 25 to 26 °C. Extreme lows have reached −27.4 °C, and extremes exceed 42 °C. During winter, outdoor activities for elderly people are affected by environmental factors such as low temperatures, strong winds, and dry conditions.

Beijing’s aging population is becoming increasingly severe. By 2023, the resident population aged 60 and above had reached 4.948 million, accounting for 22.6% of the total population. It is projected to exceed 30% by 2035 [46].

The study selected Zizhuyuan Park (covering 47.35 hm2, with water bodies accounting for approximately one-third of the total area) and Taoranting Park (encompassing 56.56 hm2 in total, with 16.15 hm2 of water) as research sites, which possess typicality and uniqueness compared to other parks in Beijing for investigating winter thermal comfort among the elderly. Their core advantages lie in: First, the dense concentration of older residential communities surrounding these parks ensures high-frequency use by the elderly, guaranteeing the authenticity and relevance of the research sample; Second, the parks’ composite landscape structure—featuring water bodies, vegetation, and topography—offers diverse microclimate research samples for investigating how elements like vegetation (e.g., evergreen and deciduous combinations) and water bodies synergistically regulate critical winter environmental factors such as low temperatures and strong winds. This capability is unmatched by other parks in Beijing. Third, existing age-friendly care and service facilities at the study site—such as the Taoranting Subdistrict Comprehensive Elderly Care Service Center located in the northwest corner of Taoranting Park—offer a complete scenario for understanding older adults’ thermal adaptation behaviors from outdoor activities to indoor rest. This tight integration of “targeted demographics, complex environments, and foundational services” makes both parks ideal empirical subjects for exploring microclimate optimization for aging in northern cold-climate urban parks.

Based on field investigations, this study selected 15 locations within each of the two parks (totalling 30 sites) according to four landscape spatial types: ① Waterfront landscape spaces (WFLS): This human activity zone comprises pathways, with a distance between the activity zone and water bodies less than 15 m. Planting is distributed in clumps, linear formations, or scattered points along both sides of the pathways. ② Sparse forest landscape spaces (SFLS): This human activity zone comprises pathways situated at least 15 m from water bodies. Planting is distributed in scattered or small, loose clumps along the outer periphery of these pathways. ③ Square building landscape spaces (SBLS): This human activity zone is dominated by extensive paved areas and structures. Trees and shrubs are distributed as accent plantings at focal points within the plaza or building or as supplementary elements along the periphery. ④ Dense forest landscape spaces (DFLS): This human activity zone comprises pathways situated at least 15 m from water bodies. Planting predominantly forms compact clumps along the outer periphery of these pathways, creating a tightly enclosed setting. It should be mentioned that the 30 sampling sites were chosen to ensure that they were (1) frequently used by elderly visitors during winter, (2) spatially representative of the four major landscape space types in the two parks, and (3) structurally diverse enough to capture variation in vegetation configuration and microclimate conditions. Sites of different landscape spaces as illustrated in the accompanying Figure 1. Subsequent analysis will determine the influence of varying PCS structures on elderly individuals’ perceived thermal comfort levels.

Figure 1.

(a) Site number in Zizhuyuan Park; (b) Site number in Taoranting Park.

2.2. Data Acquisition

2.2.1. Meteorological Measurement

This study employed a Sima ST9866A (manufactured by Dongguan Wanchuang Electronic Products Co., Ltd., Dongguan, China, under authorization from Xima Instrument Group Co., Ltd. (Hong Kong)) handheld multifunctional meteorological instrument for on-site monitoring, which simultaneously records air temperature, relative humidity, atmospheric pressure, and wind speed. According to the technical manual, its main measurement ranges, resolutions, and accuracies are as follows: wind speed range 0.6–30 m/s, resolution 0.1 m/s, and accuracy ± (0.5 m/s + 0.05 × reading); air temperature accuracy ±2 °C with a resolution of 0.1 °C; relative humidity accuracy ±4% RH within 40–80% RH and ±7% RH outside this range, with a resolution of 1% RH; atmospheric pressure accuracy ±0.1 kPa × reading and resolution 0.1 kPa; illuminance accuracy ±4% × reading and resolution 1 LUX; ultraviolet radiation resolution 0.01 mW/cm2 with an accuracy of ±0.1 mW/cm2 × reading. The device is factory-calibrated; to ensure data reliability, a zero-point check and consistency check were performed before each measurement session.

Meteorological measurements were taken at the geometric center of activity areas (e.g., plazas, paved pathways) within the 30 selected sites. Each measurement point was set to record 10 repetitions. The observation dates were 24 December 2024, 15 January 2025, and 19 November 2025, covering three key stages of Beijing’s winter progression—from early winter to mid-winter and late winter—thus providing seasonal representativeness [47]. When selecting the measurement dates, conditions such as heavy snowfall, extreme winds, and cold-wave events were intentionally avoided, as these extreme weather situations may affect both outdoor safety and the thermal comfort of older adults. Ensuring that observations were conducted under stable, clear winter weather—conditions in which older adults typically visit parks—allowed the measurements to better reflect the actual thermal environment experienced by elderly users.

During monitoring, the instrument automatically recorded and stored all meteorological variables. Considering that older adults in Beijing generally engage in outdoor activities during midday hours in winter, the observation period was set from 10:00 to 14:00. At each site, data were automatically recorded at 5 s intervals, yielding 20 raw records per repetition. Each site underwent 10 repetitions—five in the morning and five in the afternoon. After removing anomalous and extreme values during data screening, the dataset was processed, and a total of 10 valid observations per site were retained for subsequent analysis and computation.

2.2.2. Questionnaire Investigation

The questionnaire survey targeted older adults aged 60 years and above as the primary study population, while also documenting the thermal perceptions of individuals aged 45–59, who are considered to be in the early stage of aging, to facilitate a more comprehensive analysis [48,49,50]. A total of 450 questionnaires were distributed across the two parks. Questionnaires were randomly handed out, and interviews were conducted with middle-aged and older adults within the 30 selected 50 m × 50 m sampling grids, with each site required to collect at least 15 completed questionnaires. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Beijing Forestry University (Approval No.: BJFUPSY-2025-086, approved on 20 November 2025). All procedures involving human participants strictly followed the Declaration of Helsinki and the ethical guidelines required by the institution. Participation in the questionnaire survey was entirely voluntary, and informed consent was obtained verbally prior to each interview.

A combination of convenience sampling and time-interval sampling was employed. At each site, surveyors invited older adults who were present and either engaging in activities or resting in the space to participate at fixed intervals of approximately five minutes. Before the formal interview, surveyors explained the meaning of each item and each scale value; for elderly respondents, the questionnaire items were read aloud to ensure consistency of understanding. After completion, all subjective votes were digitized and prepared for subsequent statistical analysis and thermal comfort assessment.

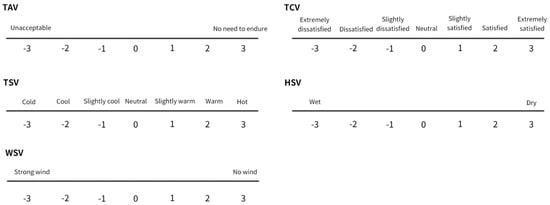

The questionnaire consisted of three components: respondents’ basic information (gender, age group, duration of stay, etc.), factors related to thermal comfort (clothing insulation, activity type, activity frequency), and five standardized seven-point subjective thermal sensation vote scales. These scales included Thermal Sensation Vote (TSV), Thermal Comfort Vote (TCV), Thermal Acceptability Vote (TAV), Wind Sensation Vote (WSV), and Humidity Sensation Vote (HSV). This system is among the most widely adopted in international outdoor thermal comfort studies and complies with ASHRAE Standard 55 and ISO 10551. The scales follow a symmetrical bipolar structure, capturing both the direction and magnitude of thermal sensations. Specifically, TSV ranges from “−3 very cold” to “+3 hot”; TCV from “−3 extremely uncomfortable” to “+3 extremely comfortable”; TAV from “−3 completely unacceptable” to “+3 completely acceptable”; WSV from “−3 strong wind” to “+3 no wind”; and HSV from “−3 humid” to “+3 very dry.” These voting scales are illustrated in the measurement ruler shown in Figure 2 [51,52,53]. The questionnaire content and detailed survey data are provided in the Supplementary Materials (File S1)

Figure 2.

Different scales of evaluation.

2.2.3. Plant Community Space Observation

Observations of landscape spaces were conducted concurrently with climate measurements and questionnaire surveys. During the research process, corresponding records and calculations were made for all plant elements at each site within a 50 m × 50 m grid. This included the number of plants, species, evergreen status, planting location, crown spread, plant height, and diameter at breast height. Following collation, corresponding plan views and plant data tables were produced for different plant communities.

2.2.4. Thermal Comfort Index

Thermal comfort is a significant factor influencing the utilization of outdoor spaces, quantitatively describing individuals’ subjective perceptions within the objective environment of park green spaces. It serves as an evaluation metric encompassing both subjective and objective factors alongside a series of complex variables. Various methods for assessing thermal comfort have been employed in relevant research, including the Comfort Index of Human Body, Wet-bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT), Physiological Equivalent Temperature (PET), Predicted Mean Vote-Predicted Percentage of Dissatisfied (PMV-PPD), and Discomfort Index (DI) [54,55,56,57]. PET is a thermal comfort metric specifically developed for comprehensive outdoor environments. It holistically considers individual parameters such as human activity-induced heat production, expressed directly in degrees Celsius (°C), to intuitively represent human thermal comfort outdoors [58,59].

This study employs Rayman (V3.2, a widely used microclimate and human–biometeorology modeling software developed by Meteorological Institute, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany) for outdoor PET thermal comfort numerical calculations [60,61,62]. The input parameters included the measured air temperature, mean radiant temperature, relative humidity, and wind speed, as well as the geographical and temporal information of each site, such as latitude, longitude, date, and time. Based on questionnaire results and field observations, most older adults in the parks were either walking slowly or sitting with light activity. The questionnaire also collected information on clothing ensembles, showing that older adults in Beijing typically wear multi-layered winter attire, such as down jackets, sweaters, long trousers, and hats. Accordingly, the simulations adopted a unified set of personal parameters representing typical winter park users among the elderly: the metabolic rate was set to 80 W and the clothing insulation to 1.2 clo, while other individual parameters followed the default settings recommended by the RayMan model.

2.3. Establishment of Evaluation System

2.3.1. Selection Criteria

This study primarily employs the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP), a commonly used method in the field of landscape evaluation for garden plants. First, based on existing literature and the characteristics of plant diversity in the Beijing region [63,64,65], an AHP evaluation model comprising four layers was constructed through expert deliberation: the objective layer is “Comprehensive Landscape Value of Garden Plant Communities”, and the criterion layer includes two dimensions—“Individual Morphological Characteristics” and “Overall Spatial Characteristics”. The indicator layer was further subdivided into five specific evaluation indicators: average plant height (C1) and average crown spread [23] (C2) belonged to the former, while community canopy closure [66] (C3), spatial enclosure (C4), and proportion of evergreen plants [67] (C5) belonged to the latter.

Subsequently, faculty members and professors at Beijing Forestry University, conducting research related to landscape content, were invited to perform pairwise comparisons using a 1–9 scale to assess the importance of factors at the same level relative to the criteria at the upper level. Based on these comparisons, a series of judgment matrices was constructed. We computed the weight vectors for each matrix and conducted consistency tests, ensuring that the consistency ratio (CR) for all judgment matrices remained below 0.1 to guarantee logical coherence in the assessments. Finally, through hierarchical total ranking, we synthesized the composite weights of the five indicators relative to the overall objective, thereby establishing the plant landscape evaluation scoring system for this study.

2.3.2. Scoring System

In this study, the quantitative utilization of landscape spatial plant elements employed the AHP [68,69,70]. Integrating existing research findings and expert assessments, and following error adjustment, the final scoring system is presented in Table 1, with a total score of 100 points.

Table 1.

Plant System Evaluation Form.

3. Results

3.1. Meteorological Measurement

Among the four landscape types, temperatures ranged from 3.5 °C to 12.7 °C. The DFLS exhibited the highest average temperature (7.49 °C), followed by the SFLS (6.56 °C) and the SBLS (5.54 °C). The WFLS recorded the lowest average temperature (5.34 °C). Overall humidity across the four space types ranged from 20% to 43%, with the highest humidity recorded in the SBLS (31.86%), followed by the WFLS (29.29%) and SFLS (27%). The DFLS exhibited the lowest humidity (25.44%). Overall wind speeds across the four space types ranged from 0.0 m/s to 0.5 m/s. Wind speeds at measurement points were not significant during the study period, with generally low values. The SBLS recorded the highest average wind speed (0.13 m/s), with some points reaching 0.5 m/s. This was followed by the DFLS (0.08 m/s) and the WFLS (0.07 m/s), while the SFLS had the lowest wind speed.

3.2. Respondents

This study collected a total of 716 valid questionnaires, with 435 from Zizhuyuan Park and 281 from Taoranting Park. The number of respondents was evenly distributed across all survey points in each park. Following the World Health Organization’s age classification standards, respondents were divided into four age groups: middle-aged (45–59 years old, 33.1%), early elderly (60–74 years old, 46.8%), elderly (75–89 years old, 31%), and centenarians (90 years old and above, 2.1%). This study also included the middle-aged cohort in the survey. Considering that middle-aged individuals will eventually enter old age and experience initial declines in various physical indicators, they can also serve as a reference point for analyzing thermal comfort perceptions among the elderly to a certain extent.

This study conducted reliability and validity tests for thermal sensation, humidity perception, wind speed perception, overall thermal comfort, and thermal acceptability. The Cronbach’s α value for the thermal comfort assessment dimension in the questionnaire was 0.762 (greater than 0.7), as shown in Table 2. This indicates that the questionnaire used in this study possesses good reliability.

Table 2.

Results of Reliability and Validity Tests for Thermal Comfort Assessment Dimensions.

Additionally, Bartlett’s sphericity test and KMO analysis were conducted. The KMO value of 0.761 (greater than 0.7) indicates that the questionnaire possesses good validity.

3.3. Defining Plant Community Space with Structure Features

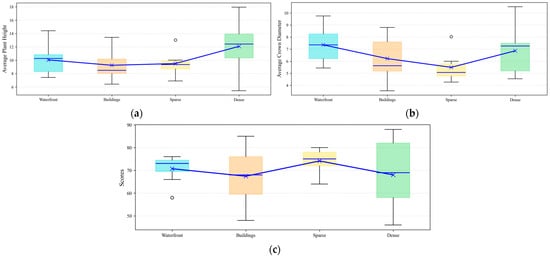

This study provides an overall comparison of the vegetation characteristics across the four landscape vegetation communities (WFLS, SBLS, SFLS, and DFLS), focusing on key indicators such as tree height, crown diameter, and plant element scores. The following four sections describe the vegetation characteristics of each landscape type in more detail, and the characteristics can be seen clearly in Figure 3 and the plant survey table is provided in the Supplementary Materials (File S2).

Figure 3.

(a) Average Plant Height in different types of landscape spaces; (b) Average Crown Diameter in different types of landscape spaces; (c) Scoring results in different types of landscape spaces.

The overall tree canopy at seven points along the WFLS exhibits a notably tall and expansive character. Their average height ranks second highest among the four categories (10.05 m), while their average crown spread is the widest across all four landscape spaces (7.35 m). Tree heights predominantly cluster between 8 m and 11 m, with crown spreads concentrated between 5.5 m and 8.5 m. This forms effective shaded corridors along roads adjacent to water bodies, creating an open and comfortable experience for waterfront activities. The scoring system for landscape space plant elements yielded an average score of 70.71 points.

The average tree height (9.25 m) across seven points in the SBLS is the smallest, while the average crown spread (6.22 m) ranks second lowest. Tree heights are predominantly distributed between 8 m and 12 m, with crown spreads concentrated between 5 m and 8.5 m. The overall plant elements primarily serve an accent role, designed to avoid obstructing rear buildings or disrupting the square’s sense of openness, thereby creating a relatively unobstructed activity space. Scoring results from the landscape space plant element scoring system yielded an average score of 67.43 points.

The SFLS features seven points with the second-lowest average tree height (9.51 m) and smallest average crown width (5.49 m). Most trees range between 8 m and 10 m in height, with crown widths concentrated between 4.5 m and 6 m. This creates a relatively sparse and open space along the roadside. Scoring via the landscape space plant element scoring system yielded an average score of 74.14 points.

The DFLS at 9 points exhibits the highest average tree height (12.08 m) and the second-highest average crown spread (6.86 m). Tree heights are concentrated between 10 m and 14 m, while crown spreads range from 5 m to 7.5 m. Through concentrated planting, effective canopy and vertical coverage are achieved, creating a profound dense forest effect. The scoring results obtained through the landscape space plant element scoring system yielded an average score of 68.0 points.

3.4. Outdoor Thermal Comfort Investigation in Different Spaces

3.4.1. PET Investigation in Different Spaces

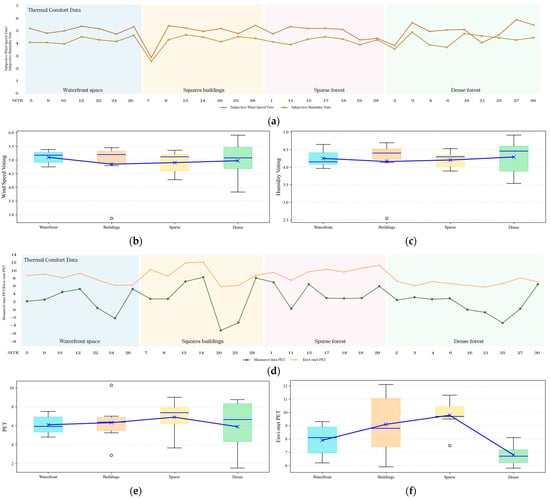

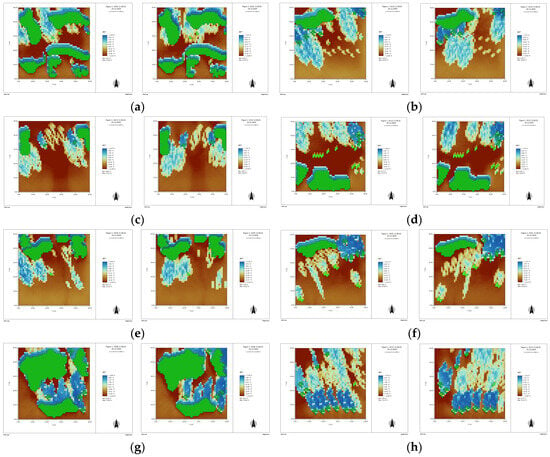

Regarding physiologically equivalent temperature, based on measured data, we also employed Envi-met (V5.6.1, a three-dimensional computational fluid dynamics–based microclimate model developed by ENVI-met GmbH, Essen, Germany) for simulation experiments to facilitate comparative analysis, thereby better demonstrating the differences and characteristics of thermal comfort among the elderly in various landscape spaces [71,72,73,74]. ENVI-met simulations were employed to capture differences in the overall microclimatic conditions across the various landscape types, while RayMan calculations based on field measurements were used to reflect the actual thermal comfort experienced by older adults at typical activity locations.

The measured meteorological data recorded between 10:00 and 14:00 were used as input parameters for the ENVI-met model to ensure that the simulation boundary conditions aligned with the actual winter environment in Beijing. The PET patterns generated by ENVI-met were highly consistent with the PET results calculated from field measurements using RayMan, and the ranking of thermal comfort across the four landscape space types was identical in both datasets: SFLS performed the best (measured 6.9 °C/simulated 9.79 °C), followed by SBLS (6.31 °C/9.1 °C), WFLS (6.1 °C/7.9 °C), and DFLS (5.89 °C/6.8 °C). This demonstrates that ENVI-met reliably captures the relative thermal comfort differences among the various landscape spaces.

In addition, when coupling Envi-met simulation results with measured PET values, we observed that simulated PET values were generally higher. The differences in radiation modeling between RayMan and ENVI-met may contribute to higher PET values in winter simulations. RayMan calculates Tmrt mainly from SVF and simplified surface information, whereas ENVI-met uses detailed 3D vegetation modeling. When winter canopy conditions are simplified, ENVI-met may underestimate shading and thus overestimate solar exposure, leading to higher Tmrt and PET. The validation shows that although the absolute PET values in the simulations were higher, the overall trends fully matched the measured results, indicating internal consistency within the model. Furthermore, all four landscape types exhibited higher simulated PET values, suggesting a systematic bias rather than space-specific model errors.

3.4.2. Thermal Comfort Voting Investigation in Different Spaces

In terms of TSV performance, as illustrated in Figure 4g,h, the SBLS (−0.04) demonstrated the best results, followed by the DFLS (−0.05), the WFLS (0.08), and the SFLS (−0.16). Regarding TCV, as illustrated in Figure 4g,i, the SFLS exhibited the highest overall thermal comfort (1.59), followed by the WFLS (1.50), the DFLS (1.42), and finally the SBLS (1.34). Regarding TAV, as illustrated in Figure 4g,j, the WFLS showed the highest thermal acceptability (0.91), followed closely by the SFLS (0.90), then the SBLS (0.64), and finally the DFLS (0.55). Overall, all four spatial types exhibited moderate thermal sensation with good thermal comfort and thermal acceptability.

Figure 4.

Outdoor thermal comfort voting and scoring results in different spaces. (a) Subjective wind speed vote and subjective humidity vote in different spaces; (b) Wind speed voting in different spaces; (c) Humidity voting in different spaces; (d) Measured data PET and Envi-met PET in different spaces; (e) PET in different spaces; (f) Envi-met PET in different spaces; (g) TSV, TCV and TAV vote in different spaces; (h) TSV in different spaces; (i) TCV in different spaces; (j) TAV in different spaces.

From the perspective of wind speed perception, which could be showed in Figure 4a,b, the WFLS exhibited the lowest wind speed perception (1.10), followed by the DFLS (0.97) and the SFLS (0.90). The SBLS showed the highest wind speed perception (0.85). Similarly, from the perspective of humidity perception, which could be showed in Figure 4a,c, the DFLS felt the driest (0.29), followed by the WFLS (0.25) and the SFLS (0.20). The SBLS felt the most humid (0.16).

4. Discussion

4.1. Evaluation of the Thermal Comfort of the Space

Based on this study’s analysis of thermal comfort in four types of landscape spaces, a complex interplay between objective and subjective perceptions was identified in elderly individuals’ thermal comfort evaluations. The findings indicate that the relationship between objective optimization of the physical environment and users’ subjective experiences is not a simple linear correlation. Among these, open forest landscape spaces were confirmed as the optimal environment for effectively coordinating both objective and subjective needs; conversely, plaza architecture and waterfront landscape spaces exhibited a phenomenon of perceptual disconnection. Further analysis of influencing mechanisms indicates that vegetation configuration is the core element regulating microclimate, with its shading intensity and layout orientation determining the quality of the objective thermal environment. Meanwhile, plant morphological characteristics exert a significant and differentiated influence on subjective perceptions across different spaces. Moreover, the elderly population generally exhibits a tendency for their perceptions of environmental factors such as wind speed and humidity to deviate from actual measured values. This underscores that landscape design for seniors must not only precisely control physical parameters but also fully consider their unique psychological perceptions and physiological needs.

4.1.1. Overall Thermal Comfort Performance

Based on the preceding analysis, we can determine the performance of various spatial types in terms of both objective and subjective thermal comfort, as well as the correlations among relevant factors.

Regarding thermal comfort performance, the SFLS demonstrated the best results in both objective and subjective evaluations. Objectively, its PET exhibited the best measured and simulated performance. Subjectively, this space achieved the highest thermal comfort perception and nearly tied for the best thermal acceptability. Although the thermal sensation was slightly cooler, its overall performance was the best among the four types.

The SBLS exhibited a pronounced divergence between objective and subjective evaluations. Its PET demonstrated the second-best measured and simulated performance. Subjective assessments indicated this space provides the closest thermal sensation to neutrality, yet it actually offered the lowest thermal comfort and relatively poor thermal acceptability. Concurrently, it showed that due to the highest wind speeds and maximum humidity stagnation, elderly individuals perceived moderate temperatures within this group-path space while experiencing poor actual comfort.

The WFLS also exhibited a degree of subjective–objective divergence. While their PET performance was average, subjective evaluations revealed the highest thermal acceptability and second-highest thermal comfort in this space, despite a slightly warm thermal sensation. It demonstrated good subjective thermal comfort acceptability despite limited actual thermal environmental regulation capacity.

The DFLS performed poorly in both objective and subjective evaluations. PET was the lowest among the four space types. Subjectively, this space had the lowest thermal acceptability and poor thermal comfort, despite a thermal sensation close to neutral. Concurrently, it exhibited poor wind speed perception and the driest humidity sensation, indicating inadequate ventilation and excessively low humidity, resulting in overall suboptimal comfort.

For the same subjective thermal comfort perception, the healthiest environment for elderly people in terms of both subjective and objective thermal comfort is the SFLS, followed by the objectively healthier SBLS. Meanwhile, although the WFLS has limited thermal regulation capabilities, it significantly enhances the subjective psychological thermal comfort of elderly individuals.

4.1.2. Envi-Met Indications

Analysis of the ENVI-met simulation outputs shows that the degree of vegetation shading surrounding activity areas has a pronounced influence on the PET levels experienced by older adults. A comparison of the four landscape space types indicates that the two spaces with better PET performance—SFLS and SBLS—exhibited relatively low and spatially uniform shading in the central activity zones, which could be seen in Figure 5. Under winter thermal comfort conditions, such spatial characteristics are particularly important: light canopy filtering reduces glare and discomfort from localized intense radiation while still allowing sufficient solar gains to enter the space, providing the radiant warmth needed during winter. Excessive shading, by contrast, substantially reduces Tmrt, resulting in lower PET values and diminishing the sense of warmth and comfort among older users. A decrease in MRT directly reflects reduced net radiant heat gain, and winter thermal comfort for older adults depends on maintaining either a positive or only slightly negative heat balance. Inadequate radiant gain therefore increases net heat loss, pushing PET away from the “slightly warm–neutral” comfort range.

Figure 5.

(a) ENVI-met Simulated PET Distribution in the WFLS at Site 9 (11:00, 13:00); (b) ENVI-met Simulated PET Distribution in the WFLS at Site 12 (11:00, 13:00); (c) ENVI-met Simulated PET Distribution in the SBLS at Site 7 (11:00, 13:00); (d) ENVI-met Simulated PET Distribution in the SBLS at Site 13 (11:00, 13:00); (e) ENVI-met Simulated PET Distribution in the SFLS at Site 1 (11:00, 13:00); (f) ENVI-met Simulated PET Distribution in the SFLS at Site 15 (11:00); (g) ENVI-met Simulated PET Distribution in the DFLS at Site 3 (11:00, 13:00); (h) ENVI-met Simulated PET Distribution in the DFLS at Site 6 (11:00, 13:00).

Further examination of the simulation maps reveals significant directional differences in how vegetation influences winter thermal comfort. When large-canopy, tall trees are located on the southern side of an activity area, they block low-angle winter sunlight and create extensive low-PET “cold zones,” which negatively affect comfort. In contrast, when vegetation of the same type is positioned on the northern side, its shading effect on winter sun is negligible; instead, it provides effective wind blocking, helping to maintain higher PET levels—sometimes even superior to conditions with no shading. Similarly, placing small-canopy or low-height vegetation on the southern side avoids excessive shading that produces cold spots while still contributing to localized wind protection, making this configuration better suited for winter activity spaces. Together, the radiative modulation and wind-blocking capacity of vegetation influence both radiant heat gain and convective heat loss, thereby altering the net human energy balance and ultimately shaping the spatial variation in PET.

Previous studies have likewise reported that the orientational placement of vegetation within a site exerts differentiated effects on thermal comfort, emphasizing the need for careful plant selection in north–south arrangements. A well-designed combination of vegetation types that forms an appropriate spatial enclosure has been identified as a key factor affecting winter thermal comfort in landscape environments [23].

4.1.3. Plant Height and Crown Diameters

The average tree height and average crown size at specific locations exerted the most significant influence on TSV, TCV, and TAV in SBLS, followed by WFLS and DFLS. Their correlation with subjective thermal comfort in SFLS was relatively low. Similarly, average tree height and average crown size exerted the most pronounced influence on PET in SBLS, followed by DFLS, while exhibiting lower correlations with subjective thermal comfort in WFLS and SFLS. Consequently, we observe that the average tree height and average crown size at specific locations exert the most pronounced influence on both subjective and objective thermal comfort in SBLS compared to other spatial types.

4.1.4. Wind and Humidity

Regarding wind speed and perceived wind angle, elderly people in DFLS and WFLS tended to subjectively perceive wind as weaker than actual wind speeds, whereas those in SFLS showed the opposite tendency—perceiving wind as stronger than actual wind speeds. SBLS exhibited greater consistency, being both subjectively and objectively the spaces with the highest wind speeds.

Regarding humidity and perceived humidity, elderly people in WFLS tended to report lower perceived humidity and drier air, while SFLS showed the opposite effect. DFLS exhibited consistent subjective and objective humidity perceptions, ranking as the driest community spaces. Similarly, SBLS consistently ranked as the most humid community spaces.

4.2. Thermal Comfort Optimization of the Space

4.2.1. Choice of Different Types of Landscape Space

As indicated above, when selecting winter landscape spaces, we should prioritize designing SFLS to ensure optimal thermal comfort for the elderly, both subjectively and objectively. Additionally, we should reserve certain WFLS and SBLS to showcase the superior thermal comfort experiences—whether subjective or objective—offered by different spatial configurations. Simultaneously, the quantity of DFLS should be controlled. When optimizing landscape spaces, those with suboptimal thermal comfort performance can be primarily adjusted to align with the characteristics of SFLS.

It should be clarified that the recommendations—such as prioritizing the design of sparse forest landscape spaces (SFLS) and moderately reducing the proportion of dense forest landscape spaces (DFLS)—are derived specifically from the objective of improving winter thermal comfort for the elderly. These suggestions target a single functional dimension and should not be interpreted as diminishing the importance of dense forest areas or other spatial types within the broader context of park planning and ecological design. Therefore, the optimization strategies proposed in this study should be understood as season-specific guidance, rather than a comprehensive replacement for multifunctional landscape planning.

4.2.2. Optimization by Different Elements

As discussed earlier, among the four spaces, the most significant factor influencing PET is the intensity of site shading. Therefore, in areas designated for elderly activities, priority should be given to planting tall trees on the north side to avoid creating large shaded areas within these zones. This ensures ample direct sunlight exposure, thereby increasing PET values and enhancing objective thermal comfort. Avoid concentrating major plantings on the south or west sides to prevent intense afternoon sunlight. Previous studies have also demonstrated that larger tree crowns possess greater heat exposure reduction capabilities [75,76]. This further indicates that during winter conditions, it is necessary to avoid the impact of extensive tree shade on thermal comfort within activity areas.

Additionally, since larger tree crowns can impede air circulation [77], medium-height tree species with moderate crown spreads should be selected for plaza architectural landscapes. This avoids the oppressive feeling or ventilation blockage caused by excessively tall or dense canopies, thereby optimizing subjective thermal comfort for the elderly. The same principle applies to dense forests and waterside landscape spaces.

The coupling of wind perception, humidity perception, and subjective thermal comfort indicates that, within known ranges, lower perceived wind speed (calmer winds) and lower perceived humidity (drier air) correlate with higher thermal comfort for the elderly. Additionally, regarding wind perception, DFLS and WFLS feature taller trees with broader canopies, more enclosed enclosures, and greater tree density in clustered formations. This creates a subjective illusion of wind protection for the elderly. In contrast, sparse forest landscapes, with their less dense vegetation, create an illusion of stronger wind for the elderly. Therefore, in design, enhancing the enclosure around areas where the elderly are likely to move, increasing the density and number of trees, and planting trees with greater height and canopy spread should be employed. This approach aims to raise the elderly’s expectation of wind protection from vegetation, thereby reducing their subjective perception of wind and improving their thermal comfort. The same principle applies to humidity and perceived humidity.

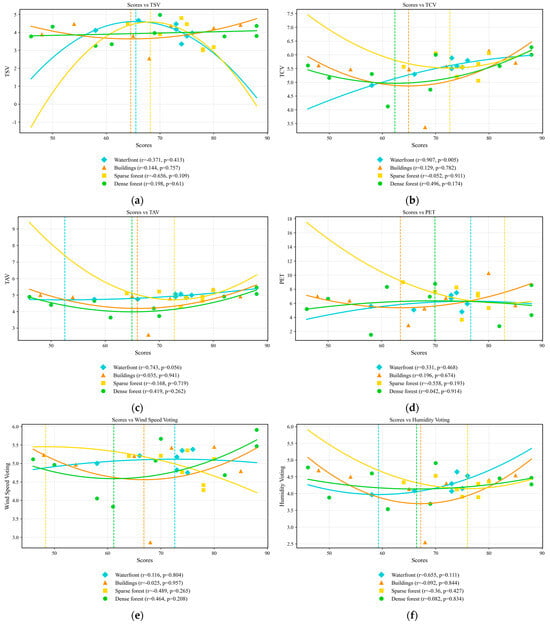

4.2.3. Optimization by Different Elements

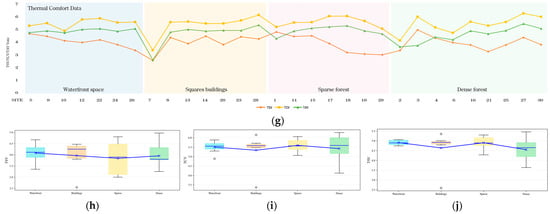

Based on the exploration of the relationship between scoring within the same type and subjective thermal comfort evaluation as described earlier, correlation calculations were performed between the scoring values at 30 sites and the thermal comfort indicators TSV, TCV, and TAV. This yielded overall correlations to facilitate comparisons of subjective thermal comfort performance across different plant community spatial types.

In addition, this study adopts an analytical framework that combines trend interpretation with multi-criteria evaluation to examine the relationship between thermal sensation voting data and the plant element scoring system. The overall assessment is based on four steps:

- (1)

- Assessment of correlation trends: Pearson correlation coefficients (r) between the scoring values and the thermal comfort indicators TSV, TCV and TAV were first calculated. The direction and magnitude of r were used to determine the general trend of thermal comfort as scores increase, thereby identifying potential positive or negative associations.

- (2)

- Identification of the extremum in quadratic regression models: For each landscape type, a quadratic regression model was constructed between the scoring values and the thermal comfort indicators. The vertex of the model was taken as the theoretical point at which thermal comfort reaches its optimum within the corresponding score range. This extremum reflects the optimal or least favorable comfort tendency associated with score variation and serves as a key mathematical basis for determining the threshold. When the computed optimal score contained decimals, it was rounded to the nearest integer to maintain consistency with the integer-based scoring system.

- (3)

- Constraint based on the TSV = 4 (optimal thermal sensation): Since TSV = 4 represents the commonly accepted “optimal thermal sensation” under winter conditions, only the samples falling within the acceptable comfort interval (TSV ≈ 3–5) were considered as valid candidates for threshold determination. For TCV and TAV, the judgment followed their physical meaning, in which higher values indicate better subjective thermal comfort.

- (4)

- Restriction by the actual distribution of observed scores: To ensure that the resulting thresholds remain applicable and meaningful, the final thresholds were confined to the intersection between the model-derived vertex and the actual distribution range of observed scores within each landscape type. This avoids identifying theoretical optimal values that fall outside the empirical score range.

For the WFLS, thermal comfort reached its optimal level when TSV = 4. At this point, the scoring values ranged between 57 and 74 points. TSV values across all points fell within the neutral acceptable range of 3 to 5, indicating generally favorable performance. Regarding TCV and TAV, within the scoring range of the points, both TCV and TAV values increased as the scores rose. Comprehensive analysis indicates that when the score reaches 74 points, elderly people experience relatively good overall subjective thermal comfort. Thus, 74 points is approximately the optimal subjective thermal comfort score for waterfront landscape spaces.

For the SBLS, thermal comfort peaks when TSV = 4. At this point, the assigned scores ranged from 52 to 78 points. Except for point 7, TSV values at all other points fall between 3 and 5, indicating neutral and acceptable levels with generally good performance. Regarding TCV and TAV, within the assigned score range, they exhibit an upward-opening quadratic function relationship with the assigned scores, sharing a symmetry axis at x = 65 points. Comprehensive analysis indicates that a score of 52 corresponds to optimal subjective thermal comfort for the elderly. Thus, 52 represents the optimal subjective thermal comfort score for the SBLS.

For the SFLS, thermal comfort reaches its optimal level when TSV = 4, with corresponding scores ranging from 61 to 75 points. TSV values across all points fall between 3 and 5, indicating neutral and acceptable conditions with generally favorable performance. Regarding TCV, it exhibits a downward-opening quadratic relationship with scoring within the point range, centered on the symmetry axis at x = 73 points. Similarly, TAV exhibits an upward-opening quadratic relationship with scoring within the point range, with the axis of symmetry at x = 73 points. Comprehensive analysis indicates that a score of 61 provides elderly individuals with the best overall subjective thermal comfort perception, making 61 points the optimal subjective thermal comfort score for sparse forest landscape spaces.

For the DFLS, TSV remains consistently above 4. Specifically, when the score is 65 points, TSV approaches 4 most closely, indicating relatively optimal thermal comfort. TSV values across all points fall between 3 and 5, falling within the neutral acceptable range and demonstrating generally favorable performance. Regarding TCV, within the scoring range, it exhibits an upward-opening quadratic relationship with the assigned score, with the axis of symmetry at x = 62 points. Similarly, TAV exhibits an upward-opening quadratic relationship with scoring within the point scoring range, with the axis of symmetry at x = 65 points. Comprehensive analysis indicates that higher scores correlate with greater overall subjective thermal comfort among the elderly. Within the point scoring range, 88 points represents the optimal subjective thermal comfort score for DFLS. The above analytical process can be illustrated in Figure 6 and the overall dataset used for the integrated analyses is provided in the Supplementary Materials (File S3).

Figure 6.

(a) TSV–Scores in different types of landscape spaces; (b) TCV–Scores in different types of landscape spaces; (c) TAV–Scores in different types of landscape spaces; (d) PET–Scores in different types of landscape spaces; (e) Subjective Humidity Vote–Scores in different types of landscape spaces; (f) Subjective Wind Speed Vote–Scores in different types of landscape spaces.

Additionally, it should be noted that each site in this study contains only 15–30 sampling questionnaires, resulting in limited statistical power for significance testing. As a consequence, several indicators exhibit clear trends despite not reaching a statistically significant p-value. Under such small-sample conditions, relying solely on statistical significance may fail to capture the actual relationship between variables. Therefore, this study determines the optimal scoring range through an integrated approach combining the trend of correlation (direction and magnitude of r), the extremum of the quadratic regression model, the acceptable TSV comfort interval, and the observed distribution of scores. This multi-criteria method provides a more robust and meaningful interpretation of the scoring–thermal comfort relationship when the sample size is limited.

From this, we can conclude that there exists a threshold for spatial differentiation among plant communities. The optimal subjective thermal comfort assignment thresholds for the four plant community types are 74, 52, 61, and 88 points, respectively. Based on these findings, we can propose potential optimization directions for enhancing winter thermal comfort for the elderly in existing UGS, guided by the optimal assignment scores.

For existing plant community spaces, design and optimization recommendations should be developed guided by their respective optimal subjective thermal comfort scores.

- Distinguish spatial types of plant communities.

- Conduct corresponding scoring.

- Compare assigned scores with target optimal scores:

- Qualified points: 0 ≤ absolute difference from optimal score ≤ 3

- Points requiring optimization: absolute difference from optimal score > 3

- Utilize scoring to quantify Excel spreadsheets and optimize site design in conjunction with CAD floor plans:

- Holistic approach: Macro-level control of crown density, enclosure ratio of planting/activity areas, and evergreen coverage across communities;

- Harmonize individual characteristics to meet site qualification standards (±3);

Simultaneously integrating optimization for optimal subjective thermal comfort scoring, the overall design approach should prioritize the degree of enclosure provided by plantings relative to activity areas. Secondary considerations include site crown density and evergreen coverage within each site, followed by coordination of individual characteristics.

For the WFLS, while ensuring they function as quality water views—where plant density does not compromise the overall scenic quality—thermal comfort must also be considered. This involves controlling enclosure levels, utilizing northern clusters for wind protection, minimizing southern cluster shading, and enhancing sunlight penetration (+20). Concurrently, site canopy closure should be set between 25 and 50% (+20), with evergreen coverage within sites controlled at 30–45% (+20). After achieving a baseline score of 60 points, macro-adjust individual tree characteristics within sites to attain a qualified site score of 74 ± 3 points.

For the SBLS, while ensuring functionality as an open activity area—adhering to principles of appropriate plant distribution along edges and focal points in the center—thermal comfort should be considered by controlling enclosure. Avoid excessive tree enclosure that blocks sunlight in activity areas, setting the standard to no enclosure (+15). Simultaneously, set the site crown density reasonably between 0 and 25% (+10) and control the proportion of evergreens within the site between 0 and 30%. Select certain deciduous tree species to facilitate light penetration (+10). After achieving a base score of 35 points, macro-adjust individual tree characteristics within the site to obtain a qualified site score of 52 ± 3 points.

For the SFLS, while preserving their characteristic openness, thermal comfort must be prioritized. Enclosure conditions should be controlled to reasonably utilize northern clusters for wind protection while minimizing shading effects on southern clusters. Increase sunlight penetration (+20) and set crown density within the range of 25–50% (+20) to achieve adequate windbreak effects. Simultaneously, control the proportion of evergreen trees within the site to 0–30% to balance wind protection and light penetration (+10). After achieving a core score of 50 points, macro-regulate the characteristics of individual trees within the site to obtain a qualified site score of 61 ± 3 points.

For the DFLS, while maintaining their characteristic density, thermal comfort should be prioritized by controlling the enclosure. Leverage the windbreak effect of denser northern clusters while minimizing southern clusters’ shading to increase sunlight penetration (+20). Set crown density reasonably between 25 and 50% (+20) to prevent excessive enclosure that degrades thermal comfort and creates cold environments. Additionally, control the evergreen coverage within the site to 30–45% (+20). After achieving a core score of 60 points, macro-adjust individual tree characteristics within the site to obtain a qualifying score of 28 ± 3 points. To achieve optimal scoring, further refine individual tree characteristics. The overall scoring process is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Plant System Optimization Form.

5. Conclusions

This study systematically examined how plant community spatial characteristics shape both the objective thermal environment and the subjective thermal perceptions of elderly users in winter urban parks. Beyond providing case-specific findings for two Beijing parks, the research contributes a conceptual and methodological framework for integrating plant configuration parameters into winter thermal comfort evaluation.

It demonstrates that plant community space (PCS) can function as an interpretable and quantifiable spatial unit for analyzing winter microclimates. By synthesizing tree height, crown diameter, crown density, enclosure conditions and evergreen configuration into a unified scoring framework, the research provides a transferable method for linking vegetation composition with thermal comfort responses and found that:

- SPLS offers optimal thermal comfort in both objective and subjective terms. SBLS provides good objective thermal comfort but poor subjective experience, while WFLS delivers better subjective experience but poorer objective comfort. DFLS performs poorly in both aspects.

- Wind speed and humidity significantly influence seniors’ subjective and objective thermal comfort. However, differing plant compositions across landscape types create variations in perceived wind speed and humidity, thereby affecting seniors’ thermal comfort perception.

- Each space type exhibits distinct optimal scoring thresholds: WFLS (74 points), SBLS (52 points), SFLS (61 points), and DFLS (88 points). This result means that differentiated optimal scoring thresholds across landscape types reveal that thermal comfort cannot be generalized through uniform design criteria. Winter plant configuration guidelines require landscape-type-specific calibration.

- Based on evaluation results and the scoring system, design guidelines for optimizing plant elements within landscape spaces are proposed. Designing sparse forest landscapes should be prioritized while reserving adequate WFLS and SBLS and reducing the number of DFLS. Considering the park’s ecology, it is recommended that the aforementioned design guidelines be applied in areas frequently used by the elderly to ensure their thermal comfort. Other areas should undergo planning for different scales and functions. Within each landscape space, first, the plant enclosure and shading conditions should be controlled; then, canopy closure and evergreen coverage should be regulated; and finally, individual plant characteristics should be coordinated to enhance winter thermal comfort for elderly people.

This research offers a theoretical step toward bridging microclimate modeling and landscape design decision-making. While the case-study data are regionally bounded, the methodological framework presented here provides a foundation for future research. Overall, this study advances the understanding of plant and vegetation communities, microclimates, and elderly thermal comfort optimization and offers actionable pathways for creating aging-friendly winter park environments.

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

The model data in this study were collected from two representative winter parks in Beijing, where older adults frequently engage in outdoor activities. Although these sites capture typical patterns of elderly park usage, the regional and seasonal constraints may still limit the applicability of the evaluation criteria. Therefore, expanding the scope of future research is necessary.

- (1)

- First, although the selected parks effectively reflect the winter activity characteristics of older adults in Beijing, additional parks with high concentrations of elderly users should be included in future studies to further validate and strengthen the generalizability of the findings.

- (2)

- Second, the study area should be extended beyond Beijing to cover larger regions, such as the broader North China area (e.g., Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei, the North China Plain), as well as other climatic zones in China and even around the world. Differences in winter climate conditions and vegetation composition may influence thermal comfort perceptions among older adults, making cross-regional comparative studies both meaningful and necessary.

- (3)

- Furthermore, although reliability and validity analyses confirmed the effectiveness of the questionnaire data, the overall sample size remains relatively limited. Since thermal comfort votes such as TSV, TCV, and TAV are highly subjective, some correlations did not reach statistical significance. Increasing the number of survey responses in future work will help improve statistical power and enhance the robustness of the results.

- (4)

- Lastly, the microclimate and thermal comfort measurements in this study were based on data collected during a single winter season. Future studies should incorporate multi-year and multi-period measurements to more comprehensively capture the mechanisms through which plant element characteristics influence the thermal comfort perceptions of older adults, thereby improving the stability and applicability of the model.

These improvements will be progressively incorporated into subsequent research to develop a more comprehensive evaluation framework and optimization strategies for winter thermal comfort in urban green spaces used by older adults.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land14122440/s1. File S1: Questionnaire content; File S2: Plants survey table; File S3: Overall data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. (Yan Lu) and S.Y.; Methodology, Y.L. (Yan Lu) and S.Y.; Validation, Y.L. (Yiyang Li); Formal Analysis, Y.L. (Yan Lu), Z.W. and Y.L. (Yiyang Li); Investigation, Y.L. (Yan Lu), Z.W. and Y.L. (Yiyang Li); Data Curation, Y.L. (Yan Lu); Writing—Original Draft Y.L. (Yan Lu) and Z.W.; Writing–Review and Editing, Y.L. (Yan Lu), Z.W., Y.L. (Yiyang Li) and S.Y.; Visualization, Y.L. (Yiyang Li); Project Administration, Y.L. (Yan Lu); Supervision, Z.W. and S.Y.; Resource, S.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 32401651; and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, grant number BLX202206.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The researchers obtained ethical approval for this research study from the Human Study Ethics Committee of Beijing Forestry University on 18 November 2025 (BJFUPSY-2025-086).

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or Supplementary Material.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Xiaopu Zhang, Jingyi Zeng, Yimeng Ming, Liping Wang, Yafengyuan Wang, Chunying Shi, Aiying Zhang, Yang Guo, and Shiwan Ren for their technical assistance in data collection during the field surveys.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yang, S.; Tu, J.; Zhang, L.; Wu, L.; Huang, H. Exploration of the Change of Aging Degree and Its Inflection Point Age of Residents in Some Communities in Jiangxi. Chin. J. Dis. Control Prev. 2023, 27, 1435–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Shen, J.; Shi, R.; Xue, J. Risk Assessment and Analysis of Ischemic Cardiovascular Disease in Middle-Aged Community Populations. Chin. J. Gen. Med. 2015, 18, 2894–2902. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, Q.; Zheng, S.; Luo, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhu, W.; Shi, Q.; Bai, Y. Risk and Influencing Factors of Hypertension in Jinchang Cohort Population. Chin. J. Hypertens. 2020, 28, 953–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinhua News Agency. Decision of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Further Comprehensively Deepening Reform and Advancing Chinese Modernization. People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/202407/content_6963770.htm (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Xinhua News Agency. The Central Urban Work Conference Was Held in Beijing, Where Xi Jinping Delivered an Important Speech. People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/yaowen/liebiao/202507/content_7032083.htm (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Zhou, P.; Song, D.; Zhang, C. Visualization Analysis and Optimization Strategy of Thermal Landscape in Retrofitted Elderly Care Buildings: A Case Study in Shanghai. Indoor Built Environ. 2024, 34, 477–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Wang, B.; Han, B. Study on Environment Regulation of Residential in Severe Cold Area of China in Winter: Base on Outdoor Thermal Comfort of the Elderly. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, H.; Li, B.; Chen, B.; Kosonen, R.; Jokisalo, J. Age Differences in Thermal Comfort and Physiological Responses in Thermal Environments with Temperature Ramp. Build. Environ. 2023, 228, 109887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, T.; Zhang, T.; Fukuda, H. Thermal Comfort Research on the Rural Elderly in the Guanzhong Region: A Comparative Analysis Based on Age Stratification of Residential Environments. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.K.C.; Pan, H.; Nie, W.; Li, X.; Wu, J.; Yin, Z.; Han, J. Effects of Perceived Environmental Quality and Psychological Status on Outdoor Thermal Comfort: A Panel Study in Southern China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 112, 105578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Cao, B.; Ji, W.; Ouyang, Q.; Lin, B.; Zhu, Y. The Underlying Linkage between Personal Control and Thermal Comfort: Psychological or Physical Effects? Energy Build. 2016, 111, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Pan, R.; Huang, Y. Study on the Correlation between Microclimate in Urban Parks and Activity Behavior of the Elderly: A Case of Luolong Park in Kunming. Urban Archit. 2020, 17, 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, H.; Qiao, L.; Cui, P. Research on Winter Thermal Comfort of Campus in Severe Cold Regions Based on Outdoor Activities. Build. Sci. 2021, 37, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos Nouri, A.; Costa, J.P.; Santamouris, M.; Kolokotsa, D. Approaches to Outdoor Thermal Comfort Thresholds through Public Space Design: A Review. Atmosphere 2018, 9, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Lian, Z.; Lai, D. Thermal Comfort Models and Their Developments: A Review. Energy Built Environ. 2021, 2, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamei, E.; Rajagopalan, P.; Seyedmahmoudian, M.; Jamei, Y. Review on the Impact of Urban Geometry and Pedestrian Level Greening on Outdoor Thermal Comfort. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 1002–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleghani, M. Outdoor Thermal Comfort by Different Heat Mitigation Strategies—A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 2011–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Brown, R.D. Integrating Microclimate into Landscape Architecture for Outdoor Thermal Comfort: A Systematic Review. Land 2021, 10, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, T.; Zhao, Q.; Huang, J. Optimization of tree locations to reduce human heat stress in an urban park. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 86, 128017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, C.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Song, T.; Liu, Y. Exploring the adaptive spatial patterns and impact factors for the cooling effect of park green spaces in riverfront area. Urban Clim. 2024, 55, 101900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Yuizono, T.; Li, R. Synergistic Landscape Design Strategies to Renew Thermal Environment: A Case Study of a Cfa-Climate Urban Community in Central Komatsu City, Japan. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivanit, M.; Hokao, K. Evaluating the cooling effects of greening for improving the outdoor thermal environment at an institutional campus in the summer. Build. Environ. 2013, 66, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Fan, X.; Guo, Y.; Li, S.; He, W.; Deng, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Wang, P.; Wu, C. Tree form characteristics as criteria for tree species selection to improve pedestrian thermal comfort in street canyons: Case study of a humid subtropical city. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 105, 105339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, M.M.; El Menshawy, A.; Nabil, J.; Ragab, A. Investigating the Impact of Various Vegetation Scenarios on Outdoor Thermal Comfort in Low-Density Residential Areas of Hot Arid Regions. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, T.; Yu, Y.; Wang, L.; Zang, H.; Cang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, X. Impacts of Vegetation Ratio, Street Orientation, and Aspect Ratio on Thermal Comfort and Building Carbon Emissions in Cold Zones: A Case Study of Tianjin. Land 2024, 13, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Xi, T. A Review of Thermal Comfort Evaluation and Improvement in Urban Outdoor Spaces. Buildings 2023, 13, 3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, D.; Lian, Z.; Liu, W.; Guo, C.; Liu, W.; Liu, K.; Chen, Q. A comprehensive review of thermal comfort studies in urban open spaces. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 742, 140092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandić, L.; Đjukić, A.; Marić, J.; Mitrović, B. A Systematic Review of Outdoor Thermal Comfort Studies for the Urban (Re)Design of City Squares. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shooshtarian, S.; Lam, C.K.C.; Kenawy, I. Outdoor thermal comfort assessment: A review on thermal comfort research in Australia. Build. Environ. 2020, 177, 106917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnabawi, M.H.; Hamza, N. Review on Gaps and Challenges in Prediction Outdoor Thermal Comfort Indices: Leveraging Industry 4.0 and ‘Knowledge Translation’. Buildings 2024, 14, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Zhang, J. Integrating thermal perception and public space use—An experimental outdoor comfort study in cold winter-hot summer zone: Beijing, China. Urban Clim. 2024, 58, 102138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wagner, A. Thermal comfort of students in naturally ventilated secondary schools in countryside of hot summer cold winter zone, China. Energy Build. 2024, 305, 113891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Pan, W.; Zhang, R.; Hong, Y.; Wang, J. Thermal comfort study of urban waterfront spaces in cold regions: Waterfront skyline control based on thermal comfort objectives. Build. Environ. 2024, 256, 111515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Nan, X.; Wang, H.; Hu, Y.; Bao, Z.; Yan, H. Optimizing the Surrounding Building Configuration to Improve the Cooling Ability of Urban Parks on Surrounding Neighborhoods. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Hong, B.; Jiang, R.; An, L.; Zhang, T. Outdoor thermal comfort of shaded spaces in an urban park in the cold region of China. Build. Environ. 2019, 155, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, B.; Guldmann, J.-M. Impact of Greening on the Urban Heat Island: Seasonal Variations and Mitigation Strategies. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2018, 71, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, M.; Meng, Q.; Jim, C.Y.; Shi, J.; Tan, M.L.; Ma, X. Landscape and Vegetation Traits of Urban Green Space Can Predict Local Surface Temperature. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 825, 154006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhan, W.; Jin, S.; Han, W.; Du, P.; Xia, J.; Lai, J.; Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Li, L.; et al. Separate and Combined Impacts of Building and Tree on Urban Thermal Environment from Two- and Three-Dimensional Perspectives. Build. Environ. 2021, 194, 107650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.-Q.; Yu, Z.-W.; Ma, W.-Y.; Yao, X.-H.; Xiong, J.-Q.; Ma, W.-J.; Xiang, S.-Y.; Yuan, Q.; Hao, Y.-Y.; Xu, D.-F.; et al. Vertical Canopy Structure Dominates Cooling and Thermal Comfort of Urban Pocket Parks during Hot Summer Days. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2025, 254, 105242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Luo, M.; Li, M.; Zhu, Y. Too cold or too warm? A winter thermal comfort study in different climate zones in China. Energy Build. 2016, 133, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, D.; Guo, D.; Hou, Y.; Lin, C.; Chen, Q. Studies of outdoor thermal comfort in northern China. Build. Environ. 2014, 77, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Li, T.; Chang, B.; Xiong, W. Research on Thermal Comfort Evaluation and Optimization of Green Space in Beijing Dashilar Historic District. Buildings 2024, 14, 3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Fang, X.; Ma, Y.; Xue, S.; Yin, S. Assessing Effects of Urban Greenery on the Regulation Mechanism of Microclimate and Outdoor Thermal Comfort during Winter in China’s Cold Region. Land 2022, 11, 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, S.; Qian, J. A Simulation Approach to Assessing Vegetation Configuration Effects on Thermal Comfort in Cold Region Pocket Parks. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peel, M.C.; Finlayson, B.L.; McMahon, T.A. Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2007, 11, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beijing Association for the Aged. Report on the Development of Elderly Care Services in Beijing (2024). Beijing Municipal Civil Affairs Bureau. 2025. Available online: https://mzj.beijing.gov.cn/art/2025/9/17/art_4490_746228.html (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Chinese Meteorological Administration. Cold Wave Warning Issued for Multiple Regions. CMA Official Website. Available online: https://www.cma.gov.cn/2011xwzx/2011xmtjj/202411/t20241112_6688112.html (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Mao, H.; Yu, H.; Tang, Y.; Weng, Q.; Zhang, K. Age differences in thermal comfort and sensitivity under contact local body cooling. Build. Environ. 2025, 268, 112355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Younes, J.; Velashjerdi Farahani, A.; Kilpeläinen, S.; Kosonen, R.; Ghaddar, N.; Melikov, A.K. Local thermal response differences due to sex and BMI among older adults in warm environments. Build. Environ. 2025, 282, 113275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Ma, Y.; Niu, J.; Huo, J.; Wei, X.; Yan, J.; Han, G. Investigating differences of outdoor thermal comfort for the elderly among genders across seasons: A case study in Chongqing, China. Urban Clim. 2025, 61, 102398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Lu, B.; Jing, W.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Luo, W.; Zhang, J.; Qiu, J.; Dong, Y. Creating comfortable outdoor environments: Understanding the intricate relationship between sound, humidity, and thermal comfort. Urban Clim. 2024, 55, 101967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]