Abstract

In many traditional villages in China, substantial government investment has been directed toward reconstructing public spaces for tourism development. Yet, many of these newly built spaces remain underused, revealing a persistent mismatch between top–down planning and villagers’ everyday needs. To address this gap, this study employs a mixed-methods approach to evaluate the quality of rural public spaces. Drawing on a systematic review, a four-dimensional assessment model—encompassing environmental, social, cultural, and economic attributes—was developed and operationalized through 17 specific indicators. The model was applied to three traditional villages in Chongqing, Southwest China, using field observation, questionnaire surveys, confirmatory factor analysis, and semi-structured interviews. The findings show that while environmental and cultural qualities are generally appreciated, villagers’ overall evaluations are strongly shaped by livelihood considerations and the extent to which public spaces support everyday practices. In tourism-oriented villages, public spaces often function primarily as attractions rather than as sites of daily life, limiting their social usefulness despite significant investment. The results demonstrate that economic indicators, which are often overlooked in existing studies, are essential for assessing the quality of public space in traditional villages and for strengthening community engagement. These insights contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of rural public space and offer practical guidance for rural revitalization and community-based planning.

1. Introduction

In a country with more than 5000 years of farming history, China’s villages are perceived as carriers of agricultural civilization. China’s central government proposed the concept of “traditional villages” in 2012 to highlight rural communities with various cultural heritages, such as vernacular architecture, rituals, and performance arts [1,2]. Beginning in 2016, China’s “No. 1 central document”, issued annually by the central government to outline the year’s most crucial policy strategies, has constantly supported the conservation activities of traditional villages. In practice, however, many local governments have adopted tourism-oriented development as the primary strategy for rural transformation, resulting in substantial investments in the construction and renovation of public spaces.

Public spaces refer to the shared physical environments within villages that accommodate daily social interaction, community activities, and cultural practices [3]. These spaces include squares, ancestral halls, temples, markets, village entrances, and other communal areas embedded in the built environment [4]. They provide settings where villagers gather, interact, exchange information, and sustain collective traditions [5]. As such, they serve not only as physical locations but also as social and cultural nodes that structure village life.

Existing research provides valuable insights into rural public space, yet several limitations remain. Scholars have defined the social and spatial characteristics of rural public space and examined its cultural and functional roles [6]. However, few studies offer a systematic and multidimensional evaluation of the quality of public space in rural settings. Although prior research has documented the spatial and cultural attributes of rural public spaces, the literature provides more limited discussion of villagers’ perceptions, the economic dimensions of public-space use, and the consequences of a top–down redevelopment.

This gap holds particular practical relevance. Although many traditional villages have redesigned public spaces to support tourism development, these spaces frequently remain underutilized or even idle, indicating a misalignment between planned spatial functions and the everyday needs of villagers [7]. In tourism-oriented settings, public spaces may further be transformed in ways that interrupt local livelihoods, weaken community cohesion, or erode the social value embedded in routine social spaces. Understanding how villagers assess public space quality is therefore essential for improving planning and supporting rural revitalization that serves local communities.

In this sense, this study makes two major contributions. First, it proposes a multidimensional assessment framework for the quality of public spaces in traditional villages, grounded in the four dimensions of rural sustainability—environmental, social, cultural, and economic. This structure synthesizes and extends existing research by integrating indicators relevant to heritage conservation, rural social life, and economic livelihood needs, thereby contributing a more context-sensitive and theoretically informed model to the literature. Second, the study provides practical significance by empirically testing the framework in three traditional villages in Chongqing. Through mixed methods, the research identifies the strengths and weaknesses of reconstructed public spaces, reveals the factors that influence villagers’ engagement, and generates insights for policy-makers, planners, and village committees. These findings offer actionable guidance for designing rural public spaces that genuinely support villagers’ livelihoods, enhance community participation, and improve the effectiveness of rural revitalization policies.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Defining Rural Public Space

Research on rural public space has been relatively limited compared with the extensive scholarship on urban public space. This tendency is observable across both international and Chinese academic contexts, where studies on urban environments, publicness, and spatial quality have developed earlier and on a much larger scale. In China, however, interest in rural public space has increased noticeably since the introduction of the “Building a New Countryside” policy in 2005, which stimulated research on traditional villages, rural landscapes, and community spaces. Within this body of work, scholars have proposed a range of definitions reflecting the spatial and social complexity of rural public space.

Wang et al. [3] describe rural public space as a setting rooted in longstanding social structures, supporting daily activities as well as collective events such as rituals, ceremonies, and communal gatherings. Zhang [8] approaches public space through a spatial–administrative lens, defining it as the residual areas between private household spaces where interaction, negotiation, and social conflicts occur. Lu et al. [5] expand the concept by introducing “implicit public space,” referring to domestic and semi-commercial spaces—such as kitchens, eaves corridors, tea houses, and farm guesthouses—that function as everyday social nodes. Wen et al. [4] further conceptualize public space as a multi-scalar system encompassing domestic, communal, and natural environments.

These perspectives highlight the dual nature of rural public space: it is both a material environment and a social arena shaped by everyday practice and collective memory. In this study, rural public space is defined as the built environment that enable social life in traditional villages, including temples, markets, village entrances, ancestral halls, and community offices, while excluding the broader natural landscape identified in Wen et al. [4].

2.2. Indicators of the Quality of Rural Public Space

Based on the existing studies of the quality of public space in rural China, this study critically reviews studies on the design of rural public space and also adopts suitable indicators from studies on the quality of urban public space. This study performed a systematic retrieval of sources available in academic databases, including CNK and Web of Science to locate related literature. The search keywords refer to “rural public space”, and “the quality of public space”. In total, 742 publications were collected, covering public space design, rural planning and sustainable development. After removing duplicates and irrelevant studies, 87 publications were retained. Studies were included if they:

- (a)

- proposed evaluation indicators of public space or rural built environment;

- (b)

- discussed design principles for rural or village public spaces.

Studies on the quality of rural public space has undergone a gradual conceptual expansion, shifting from early attention to physical attributes toward a more comprehensive understanding that incorporates social, cultural, and economic dimensions. Although individual studies vary in terminology and analytical focus, the reviewed literature consistently conceptualizes the quality of public space as a multidimensional construct. This convergence is visible across several research traditions, including urban public space studies, rural settlement research, heritage conservation, and rural revitalization. These strands provide the theoretical basis for organizing indicators into four domains: environmental, social, cultural, and economic.

Early studies largely focused on the physical environment, highlighting spatial form, comfort, and legibility as foundational qualities of public space. Environmental attributes such as “spatial size” and “enclosure and boundary clarity” strongly influence how users perceive openness, orientation, and spatial coherence [9,10,11]. Natural elements, such as vegetation and shade, further enhance environmental experience [12]. The provision of furniture in public space, including seating and shading structures, supports prolonged use and facilitates everyday social interaction. Across these studies, environmental comfort and physical functionality emerge as the baseline conditions necessary for the use of rural public space.

A second cluster of literature highlights the social qualities of public space, emphasizing its role in sustaining rural everyday life. Public spaces in villages serve as key sites for kinship interaction, communal activities, and informal communication. Accessibility is widely recognized as a prerequisite for participation [13], while safety and security—both physical and perceived—are essential for enabling social cohesion [14,15]. Indicators such as the capacity to meet basic needs and the presence of mixed uses reflect the multifunctional character of rural public space [16]. Social inclusiveness, particularly regarding gender and vulnerable age groups such as children and the elderly [6,17,18], is increasingly recognized as central to understanding how rural public spaces support daily routines and community well-being.

A third body of research emphasizes cultural attributes, particularly in studies of heritage conservation and traditional villages. Material authenticity, which relates to vernacular architecture and traditional craftsmanship, is regarded as essential for preserving cultural continuity [19,20]. Color schemes rooted in regional aesthetics strengthen place identity [15,21,22]. Symbolic elements embedded in the built environment, including ancestral motifs and ritual markers communicate local meaning [23,24]. Other studies highlight spiritual connections mediated through rituals, festivals, and shared emotional attachment to place [25]. These cultural indicators underscore the symbolic and identity-forming functions of rural public spaces, especially in traditional settlements.

More recent studies, particularly those situated within rural revitalization, tourism development, and multifunctional landscape research, identify economic attributes as important components of the quality of public space [26,27]. Public spaces increasingly serve as platforms for livelihood activities, enabling direct economic benefits such as selling agricultural goods or offering tourism-related services. They also produce indirect economic effects by enhancing village visibility, attracting visitors, and supporting broader development potential [28]. The potential value of public spaces, particularly their capacity to adapt to future economic or community needs, is likewise recognized as an important evaluative attribute [29]. These studies highlight the expanding role of public spaces as socio-economic resources in rural development.

Although previous studies have proposed various indicator systems for evaluating public space, most existing frameworks differ in emphasis depending on research context. Urban-oriented studies typically prioritize environmental comfort, accessibility, and physical design attributes [10,13]. In rural studies, recent frameworks increasingly recognize the importance of livelihood-related functions [30,31], yet economic attributes are often treated implicitly or examined separately from spatial quality.

Compared with these approaches, the framework adopted in this study does not seek to replace existing models, but rather synthesizes their common conceptual structure into four dimensions that repeatedly emerge across the literature, including environmental, social, cultural, and economic. Similar multidimensional approaches have also been applied in rural contexts, where the quality of public space is assessed through the combined evaluation of built-environment characteristics and users’ perceptions [32].

By integrating these dimensions within a single analytical framework, the proposed model remains consistent with earlier studies while making economic attributes more explicit in order to reflect the livelihood-oriented realities of traditional villages shaped by tourism development and rural revitalization policies. Overall, the literature suggests that although specific indicators vary across studies, they tend to cluster around these four interrelated conceptual domains.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Areas

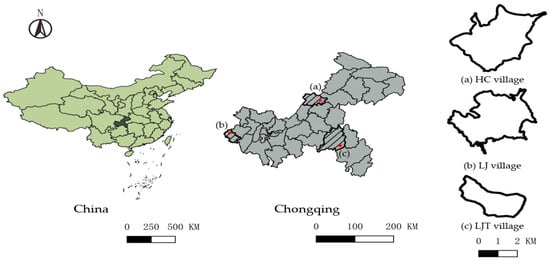

This study adopted a maximum variation sampling strategy rather than probabilistic sampling. The objective was to capture key contrasts in economic structure, cultural background, and modes of public space development within traditional villages, rather than to achieve statistical representativeness. Such an approach is appropriate for exploratory mixed-methods research that seeks to test the applicability of a conceptual framework across diverse contexts. Following this sampling strategy, three traditional villages were selected as case study areas (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study area.

Located in Chongqing, a mountainous region in Southwest China, the three selected traditional villages as case studies are all endowed with rich tourism resources. Luojiatuo (LJT) village is located in Anzi Town, Pengshui County, southeast of Chongqing. In ancient China, one of the main roads between Sichuan and Hunan passed through LJT village, which was also the trade route connecting Hunan, Hubei, and Guizhou. LJT village is not only a clan village, but also the best-preserved and largest village for the Miao ethnic group in Chongqing. Currently, although the Han and Miao cultures have influenced each other in LJT village over a long period, most villagers still maintain their local customs and traditional habits. The stilted building (diaojiaolou, 吊脚楼) and the folk song “Jiao Ayi” are the main cultural heritage indications of LJT village.

Liuji (LJ) village is located in Rongchang County, west of Chongqing, and its name commemorates the sacrifice of the Captain of People’s Liberation Army (PLA), Liu Ji. Tonggu stockaded village is the main residential area in LJ village, and it is also the place where the war between the Chinese Communists and Nationalists in LJ village took place in 1950. In 1800, rampant bandits in the Rongchang area threatened the safety and personal property of villagers, especially some landlords and rich people. Thus, the local respected and influential clans constructed Tonggu stockaded village. The stockade village had four gates—dongan (东安), nanzhi (南治), xiji (西吉), and beiqing (北清)—and they were connected by four stone walls with a total length of 9 km. In the present day, some of the gates and stone walls are still well preserved. Currently, the tourism development of LJ Village is primarily developed the themes relates to Chinese revolutionary culture 1 and the village’s cultural heritage.

Hucao village (HC village) is situated in Panlong town, Liangping County, northeast of Chongqing. The agricultural products of HC village, particularly rice and watermelons, are well known for their high quality. The village was built in the early Qing dynasty and named after the Hu clan, which moved there from Hubei. Due to its proximity to the ancient post road between Sichuan and Hubei and its convenient transportation, HC village was historically favoured by many Buddhist and Taoist practitioners, foreign missionaries, and wealthy gentry. Several temples were constructed within HC village, including Guanyin Temple, Chuanzu Temple, Yujia Hermitage, and Tianbao Hermitage, in the late Qing dynasty. However, tourism in HC Village relies less on cultural heritage and more on the high-altitude summer resort industry.

Although the three selected villages are all located within Chongqing, they represent distinct developmental contexts. LJT Village is located in an area with relatively limited economic and transportation development, but it possesses exceptionally rich cultural resources. Although Rongchang County has a relatively strong economic base, Liuji Village’s considerable distance from the urban center weakens its locational advantages and constrains its access to transportation, industrial linkages, and tourism opportunities. Liangping District is a nationally recognized grain-producing area, and HC Village has a relatively stable agricultural structure. As HC Village is close to the urban center, the circulation of agricultural products, access to employment opportunities, and the availability of public services have all improved.

3.2. Research Methods

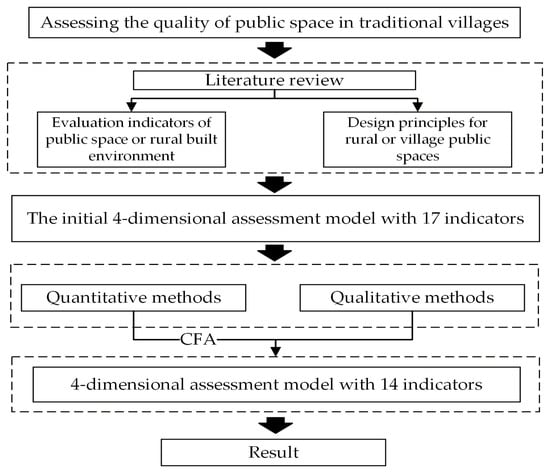

This study employed a mixed-methods research design integrating questionnaire surveys, semi-structured interviews, and field observation. The combination of quantitative and qualitative approaches enables triangulation of evidence and provides a comprehensive understanding of villagers’ perceptions and lived experiences of public space (see Figure 2). Specifically, the mixed-methods design adopts a complementary strategy, in which quantitative and qualitative data are integrated at the interpretation stage. Survey results are used to identify overall patterns and variations in perceived public-space quality, while interview and observational data are employed to contextualize and explain these patterns by revealing underlying practices, meanings, and livelihood-related constraints. This approach enhances explanatory depth rather than pursuing strict statistical triangulation.

Figure 2.

Research workflow.

3.2.1. Construction of the Indicator System

The 17 indicators used in the questionnaire were derived through a systematic, multi-step process grounded in the literature review. First, more than forty candidate indicators were extracted from existing studies on urban public space, rural settlement research, heritage conservation, and rural revitalization. Second, these indicators were conceptually clustered into four domains—environmental, social, cultural, and economic—based on recurring themes identified across the literature and consistent with multidisciplinary theoretical frameworks. Third, overlapping indicators were consolidated into broader constructs.

In this sense, a final set of 17 measurable indicators was established (see Table 1). These indicators formed the basis of the assessment model and were operationalized directly into questionnaire items.

Table 1.

The indicators of the quality of public space.

3.2.2. Questionnaire Design

The questionnaire was developed based on the 17-indicator assessment model constructed from the literature review.

Each indicator was selected only if it met two criteria: first, it could be theoretically located within one of the four dimensions identified in the literature review; second, it could be operationalized through villagers’ subjective perceptions of public space. In this way, the theoretical framework directly informed both the selection and the structure of the measurement instrument.

Additionally, each indicator was operationalized into a single statement rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), enabling quantitative evaluation of villagers’ perceptions of the quality of public space. The questionnaire consisted of two parts:

- Demographic information, including age, gender, education, income;

- Quality assessment items, corresponding to the four dimensions—environmental, social, cultural, and economic;

- This design ensured that the measurement instrument was directly aligned with the theoretically grounded indicator system and could be used to test the proposed four-dimensional structure through confirmatory factor analysis.

3.2.3. Interview Procedure

Semi-structured interviews were conducted to complement the quantitative data and to explore villagers’ experiences and expectations regarding public spaces. The interview protocol included open-ended questions on:

- Reasons for using or not using certain spaces;

- Perceived changes due to tourism or reconstruction;

- Expectations for future improvements.

3.2.4. Data Collection Steps

Data collection took place between May to August 2021 in the three villages. The process followed five steps:

- Participant recruitment: Coordination with village leaders to ensure random distribution of questionnaires across gender, age groups, and residential clusters.

- Questionnaire distribution: Paper-based questionnaires were administered face-to-face. Researchers provided assistance for participants with reading difficulties.

- Observation: Systematic observation of the usage of public space was conducted at different times of the day.

- Interview: Semi-structured interviews were conducted after questionnaire completion to further contextualize responses.

3.2.5. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using Mplus 8.0 to test the reliability and validity of the proposed four-dimensional assessment model. The analysis followed established procedures:

- Assessment of measurement model: Standardized factor loadings, composite reliability, and average variance extracted (AVE) were examined.

- Evaluation of model fit: Multiple indices were used, including χ2/df, RMSEA, CFI, and TLI.

- Comparison with alternative model: An 1-dimensional model was tested against the 4-dimensional structure to validate dimensionality.

- Modification indices: These were examined to ensure a theoretically justified and statistically sound model without overfitting.

4. Results

4.1. The State of Public Spaces

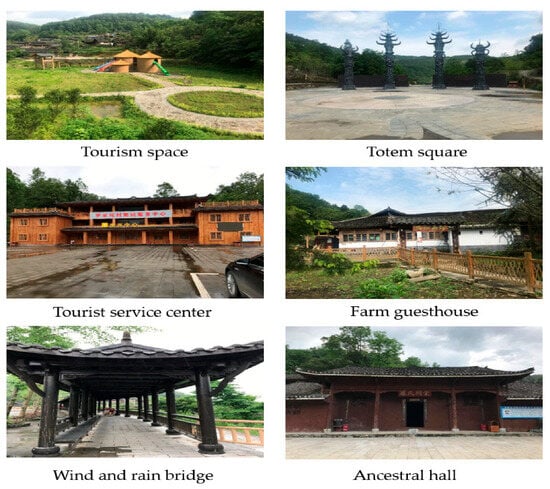

4.1.1. An Overview of LJT Village

Under the guidance of local government planning, most public spaces in LJT village have been reconstructed to serve tourism development (see Figure 3): the expansive but often underutilized tourism space; an totem square with sacred water buffalo pillars; a combined tourist service center and village committee office; a commercial tea house within a guesthouse; a wind and rain bridge built symbolically on land rather than over water; and an ancestral hall transitioning from ancestor worship to cultural exhibition. However, few tourists or villagers were present in these public spaces during the observation.

Figure 3.

Public spaces in LJT village.

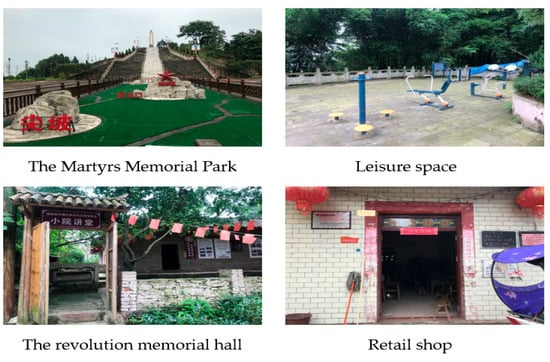

4.1.2. An Overview of LJ Village

Public spaces in the village serve two distinct functions: some are dedicated to commemorating revolutionary history, such as the Martyrs Memorial Park and the revolutionary memorial hall, while others cater to daily social and practical needs, such as leisure space and the retail shop (see Figure 4). The Martyrs Memorial Park, established in 1998 along Mount Tonggu, functions as a patriotism education base, featuring a command sand table, a central square for paying respects, and a monument. The revolutionary memorial hall, housed in a vernacular L-shaped building in the residential area, displays historical items such as weapons and equipment used in local battles. The leisure space with exercise equipment was seldom used or maintained, and a retail shop was run from a residential house as an informal gathering spot. Similar to LJT village, the villagers in LJ village rarely used public spaces. However, LJ village had a steady stream of tourists.

Figure 4.

Public spaces in LJ village.

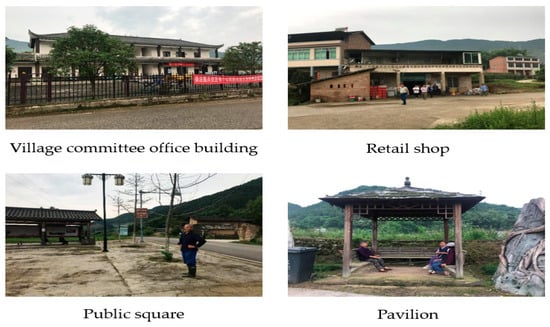

4.1.3. An Overview of HC Village

Public spaces in HC village primarily serve four distinct functions: administrative service, commercial trade, social congregation, and casual rest. The village committee building provides flexible public services, including an agricultural supermarket and a financial station, operated by local villagers on an on-call basis. A residential retail shop runs on a seasonal schedule, with a distinct lull during lunch hours. Social gatherings predominantly occur at the periphery of the public square, especially under the shaded wind and rain bridge, as the central plaza remains vacant and lacks seating. Meanwhile, a pavilion nestled between fields functions as a natural meeting point and resting spot for morning walkers. During the observation, public spaces in HC village are frequently used by villagers (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Public space in HC village.

In conclusion, the field observations reveal clear differences in how public spaces operate across the three villages. In LJT and LJ, tourism-oriented and commemorative projects produced spaces that were visually upgraded but only weakly connected to residents’ daily routines, resulting in limited use. In contrast, the public spaces in HC village were closely integrated with everyday social interaction, informal commerce, and accessible public services, which supported frequent use.

4.2. Villagers’ Responses on the Quality of Public Space

4.2.1. Demographic Differences

Table 2 how demographic characteristics influence villagers’ evaluations of the quality of public space. Although gender shows little variation, the clear age-related differences suggest that older residents tend to express higher levels of satisfaction across most indicators. This pattern is consistent with findings in environmental-behavior research, which indicates that older individuals often have more stable daily routines, spend more time within their immediate environment, and may possess stronger emotional attachment to familiar rural settings. As a result, they are more likely to evaluate existing public spaces positively, even when functional limitations are present.

Table 2.

The mean scores of quality indicators based on demographic differences.

Educational differences display the opposite trend. Respondents with a high school education consistently provided the lowest scores, which may reflect higher expectations for spatial quality or greater exposure to urban public-space standards. These participants may more readily recognize deficiencies in design, maintenance, or function, leading to more critical assessments. Income-related variation also provides insight into how economic conditions shape spatial perceptions. Participants with moderate household incomes (3000–10,000 CNY) reported the highest satisfaction levels, possibly because their livelihood pressures are neither as severe as those of lower-income groups nor accompanied by the elevated expectations often held by higher-income villagers. This supports the argument in rural livelihood studies that economic security influences not only spatial use but also perceived spatial adequacy.

Across all demographic groups, environmental and cultural dimensions received relatively high scores, suggesting that villagers generally appreciate the physical setting and cultural expression of public spaces, even when functional aspects are limited. In contrast, lower scores in the social and economic dimensions indicate persistent challenges related to everyday usability, livelihood support, and the integration of public spaces into daily life. The minimal variation in the scores for “safety and security,” “natural elements,” and “gender equality” further reinforces the idea that these attributes are broadly shared across the villages. High perceived safety reflects strong kinship-based trust networks typical of rural communities, while uniformly positive assessments of natural elements correspond to the consistently high-quality ecological environment common to the region. The limited differentiation in gender-related perceptions may indicate that villagers understand gender equality primarily in terms of basic survival and access, rather than in terms of nuanced spatial needs.

Overall, these demographic patterns demonstrate that subjective evaluations of public space are shaped not merely by spatial design but by broader socio-economic conditions, life experiences, and cultural expectations. The findings highlight the importance of situating public space assessment within the lived realities of different social groups, rather than relying solely on environmental or aesthetic criteria.

Table 3 presents age, age (r = 0.579, p < 0.01), educational level (r = −0.474, p < 0.01), and income (r = −0.393, p < 0.01) were significantly associated with the quality of public space. In addition, age was also significantly associated with the four dimensions of the quality of public space, while educational level was significantly related to the environmental dimension, and income was significantly associated with the environmental and cultural dimensions.

Table 3.

The correlation between the quality of public space and demographic factors.

4.2.2. Variations in Quality Assessments Across Villages

The application of the four-dimensional framework across the three villages illustrates how differences in livelihood conditions, spatial functions, and everyday practices shape villagers’ evaluations of public space. Rather than treating the framework as an abstract classification, the analysis demonstrates how each dimension becomes more or less salient under different development contexts.

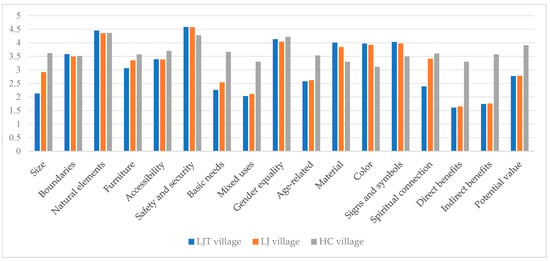

Figure 6 presents the ratings of the quality of public space by villagers across the three villages. Participants were more satisfied with the quality of the environmental and cultural dimensions of the public space in LJT village but expressed dissatisfaction with the quality of the economic dimension of these public spaces; The evaluations of the quality of public space provided by villagers of LJ and LJT villages exhibit only minor variation; compared to the other two villages, the inhabitants of HC village are more satisfied with the social and economic dimensions of the quality of their public spaces. These findings align with the prior observational and interview data. Furthermore, scores for “safety and security”, “natural elements” and “gender equality” still show little differences across the surveyed villages.

Figure 6.

The mean scores of the quality of public spaces in the three villages.

The cross-village comparison reveals several important mechanisms that help explain villagers’ differing evaluations of the quality of public space. These differences are rooted not only in environmental attributes, but more fundamentally in how public spaces intersect with villagers’ livelihoods, social organization, and cultural practices.

In LJT Village, the low satisfaction with economic indicators reflects the tension between top–down tourism-driven reconstruction and villagers’ everyday livelihood structures. Public spaces were redesigned primarily as tourism attractions, yet the village’s remote location and weak tourism market limited the expected economic returns. According to rural livelihood theory, when reconstruction projects fail to generate tangible income, villagers are less motivated to participate in public life, leading to underuse of otherwise well-designed spaces. This outcome illustrates that the effectiveness of rural public-space interventions depends not only on physical improvement but also on whether these spaces align with local economic realities.

In LJ Village, the moderate evaluations highlight a different dynamic. Although heritage conservation and memorial functions are well established, villagers’ engagement with reconstructed spaces remains limited due to the loss of farmland and declining agricultural livelihoods. This finding supports the argument in cultural landscape theory that public spaces perform best when they maintain continuity with everyday practices. When commemorative and tourism-oriented spaces overshadow daily needs, their social value diminishes, even if they are culturally significant.

In contrast, HC Village demonstrates how stable livelihood conditions and organically evolved public spaces enhance satisfaction across both social and economic dimensions. Here, public spaces have emerged gradually through long-standing patterns of use rather than through rapid, externally driven reconstruction. This corresponds to theories of place attachment, which suggest that sustained interaction with familiar spaces strengthens social cohesion and reinforces positive evaluations of spatial quality. Moreover, the stable income generated through land leasing reduces livelihood pressures and enables villagers to use public spaces more regularly, increasing both functional and social value.

As a result, these findings show that the perceived quality of public space is closely tied to three key factors: (1) livelihood security, (2) continuity with local cultural and social practices, and (3) the degree of alignment between spatial interventions and everyday needs. The value of these results lies in demonstrating that public-space quality in traditional villages cannot be adequately assessed through physical design indicators alone. Instead, broader socio-economic and cultural contexts can be integrated into evaluation frameworks to produce meaningful and actionable insights for rural revitalization.

4.3. Villagers’ Narratives on the Quality of Public Space

The interview data were used to further interpret the quantitative findings by providing contextual explanations for observed patterns across villages and dimensions. Rather than being analyzed independently, qualitative narratives were examined in relation to survey results to clarify why certain indicators received higher or lower scores in different contexts.

4.3.1. LJT Village

In LJT, many villagers described a clear sense of disconnection from the newly reconstructed public spaces. They repeatedly emphasized that these spaces were created primarily for tourism rather than for everyday use, and several interviewees noted that “the new square used to be our best farmland.” Because the reconstructed spaces displaced agricultural land yet failed to attract sufficient visitors due to the village’s remote location, villagers saw little economic benefit from the redevelopment. This sentiment is fully consistent with the low economic scores in the survey and reflects a broader livelihood concern: without stable income from either agriculture or tourism, villagers have little incentive or available time to engage in non-productive public activities (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Coding structure of interview data in LJT village.

These interview insights help explain the low economic and social scores observed in the survey results, particularly villagers’ limited engagement with reconstructed public spaces and their dissatisfaction with livelihood outcomes.

4.3.2. LJ Village

Interviewees in LJ village expressed a different but related experience (See Table 5). While they acknowledged the historical importance of the Martyrs Memorial Park and the memorial hall, several participants noted that these spaces “belong more to history and visitors” and have limited relevance to their daily lives. Some also mentioned that after the conversion of farmland to forest, they had to focus on finding substitute income sources, leaving little time for public sociability. These narratives help explain the moderate satisfaction recorded in the social dimension: the spaces are appreciated for their symbolic value, but they do not effectively support contemporary social interaction or livelihood activities (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Coding structure of interview data in LJ village.

These interview insights help explain the moderate social scores observed in the survey results, particularly the villagers’ limited everyday use of commemorative public spaces and their constrained opportunities for social interaction following livelihood restructuring. Although residents recognize the historical and symbolic value of the Martyrs Memorial Park and related facilities, the interviews reveal that these spaces are perceived as oriented towards visitors rather than daily village life. As a result, their contribution to contemporary social engagement remains limited, which is reflected in the survey-based evaluation of social quality.

4.3.3. HC Village

By contrast, villagers in HC village repeatedly described public spaces as an integral part of everyday routines (see Table 6). Many referred to the wind-and-rain bridge, the pavilion near the fields, and the village committee courtyard as places they visit “naturally, without thinking about it.” Interviews revealed that villagers use these spaces for a wide range of purposes—resting during farm work, discussing neighborhood matters, selling small quantities of produce, gathering after dinner, or simply meeting acquaintances by chance. This everyday embeddedness is made possible by the relatively stable livelihoods in the village: because land leasing provides a secure and predictable source of income, villagers have more discretionary time and fewer livelihood pressures (see Table 6). This reality aligns closely with the higher survey scores in both the social and economic dimensions.

Table 6.

Coding structure of interview data in HC village.

In this sense, these qualitative insights show that villagers’ evaluations of public spaces are shaped not only by design features but also by the ways in which spatial interventions intersect with their economic needs, social practices, and established rhythms of rural life. Villagers’ satisfaction with the quality of public spaces tends to be low when spatial interventions disrupt traditional livelihood structures or fail to accommodate everyday routines. In contrast, their satisfaction is higher when public spaces emerge organically from long-established patterns of use and coexist with stable local economic conditions. The interview findings therefore reinforce the mixed-methods analysis by demonstrating that the meaning and value of rural public spaces are inseparable from the broader socio-economic environment in which they are embedded.

4.4. Validation of the Assessment Model

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) is employed to verify the hypothesized relationships between observed variables and their underlying latent constructs [54]. Given that the assessment model comprises multiple factors, CFA serves as an appropriate approach for testing and validating the measurement scale.

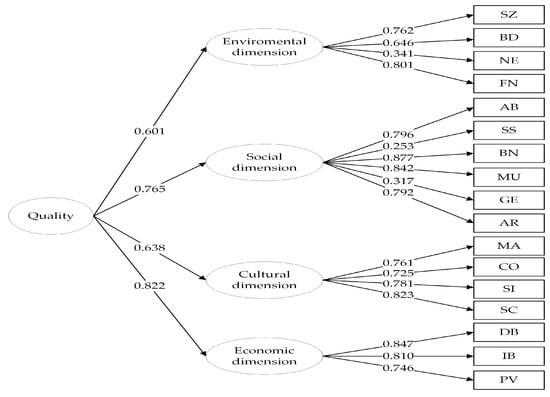

4.4.1. Factor Loadings

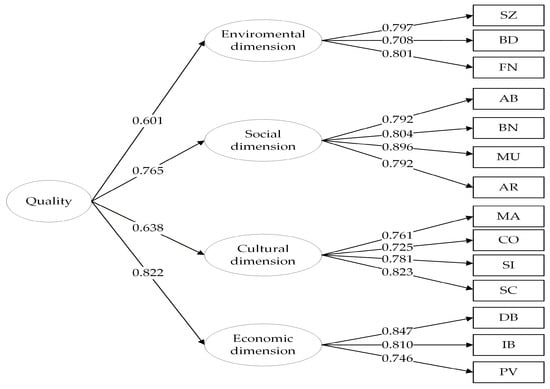

Figure 7 reports the first- and second-order factor loadings for assessing the quality of public space. Three items (NE, SS, and GE) had loadings below 0.5, indicating that they were not valid indicators in the initial model. The four-factor model with 17 items also showed poor overall fit (Table 7). After removing these three items and re-estimating the model, the revised four-factor structure with 14 items showed improved fit, and all factor loadings exceeded 0.5 (Table 7 and Figure 7). However, the fit indices still did not fully meet the acceptable thresholds, suggesting limited validity.

Figure 7.

Factor loadings of the 4-dimensional model with 17 indicators.

Table 7.

Fit statistics for the quality of public space confirmatory factor analysis.

As shown in Table 7, the one-dimension assessment model with 14 indicators produced the weakest fit: the discrepancy-to-ratio value exceeded 3.0, RMSEA was greater than 0.1, and both CFI and TLI fell below 0.9. In contrast, the four-dimension assessment model with the same 14 indicators met all acceptable fit thresholds (see Table 7 and Figure 8). This indicates that the four-dimensional structure provides a substantially better representation of the data. Overall, these results demonstrate that the final four-dimensional assessment model is a valid tool for evaluating the quality of public space in traditional villages.

Figure 8.

Factor loadings of the 4-dimensional assessment model with 14 indicators.

4.4.2. Partial Correlations

The partial correlations revealed in Table 8 demonstrate the moderate interrelationship among the four dimensions of the assessment model, and the range of partial correlations between the four dimensions is from 0.252 to 0.507. These results indicate that while each dimension reflects a unique aspect of the quality of public space, they collectively contribute to overall spatial experience.

Table 8.

Partial correlations between the quality and its sub-dimensions.

5. Discussion

This study examined the quality of public spaces in three traditional villages in Chongqing using a mixed-methods framework that integrated field observations, questionnaire surveys, confirmatory factor analysis, and interview-based thematic coding. The findings reveal that villagers’ assessments of public-space quality are shaped not solely by spatial design, but more fundamentally by the interplay of livelihood security, everyday social practices, and cultural continuity. This finding echoes recent empirical studies showing that spatial design features influence residents’ social and cultural perceptions through their everyday experiences and behavioral responses [55].

5.1. Livelihood Security as a Foundational Determinant of Perceived Spatial Quality

Across all three villages, livelihood security consistently emerged as the most influential factor shaping villagers’ evaluations of public-space quality. The quantitative results show that the economic dimension received the lowest scores in both LJT Village and LJ village, and the interviews reveal the underlying causes. In LJT village, large tracts of farmland were converted into tourism-oriented public spaces without compensation, directly undermining villagers’ traditional farming-based livelihoods. Similarly, in LJ, the Returning Farmland to Forest Programme eliminated productive land and offered limited economic alternatives. As a result, villagers in both villages relied heavily on subsidies or remittances from migrant family members, and they expressed frustration that tourism development has not translated into actual income opportunities.

These findings align with rural livelihood theory, which argues that when fundamental livelihood assets—such as land, labor, or agricultural income—are weakened, villagers deprioritize participation in non-essential community activities. This dynamic is evident in LJT and LJ: although tourists occasionally visit, the lack of stable, village-level income channels means that public spaces are perceived as disconnected from everyday life. The aesthetic improvements brought by reconstruction are thus insufficient to offset the loss of land or the absence of economic return.

By contrast, HC presents the opposite scenario. Stable economic conditions—generated through diversified agricultural production, convenient logistics, and land leasing to agricultural companies—provide villagers with predictable income and reduce livelihood pressure. Interview data highlight that villagers have more discretionary time and are more willing to engage in social activities, visit public spaces, and participate in community life. Consequently, HC recorded higher satisfaction levels in both the social and economic dimensions of the questionnaire.

As a result, these patterns suggest that livelihood stability functions as a precondition for villagers’ meaningful engagement with public space. Without economic security, improvements to physical infrastructure or cultural features have limited impact on subjective spatial quality.

5.2. Continuity with Daily Routines and Social Practices

A second major finding is that public spaces are evaluated positively when they align with, or emerge from, villagers’ everyday routines. In both LJT and LJ village, reconstructed public spaces were designed primarily for tourism or patriotic education, resulting in weak connections to daily practices. The interview results repeatedly highlight that villagers view these spaces as “for visitors” rather than for themselves. With farming activities relocated to neighboring areas or eliminated due to land conversion, villagers spend less time within the immediate village and have fewer reasons to engage with the newly developed spaces. Moreover, the lack of utilities such as natural gas, the broken exercise equipment, and the absence of shade or seating further reduces the functional relevance of these areas.

These observations resonate with the literature on everyday urbanism and cultural landscape theory, which argues that public spaces derive their social meaning not from physical form alone, but from their integration with habitual behaviors. When spaces are introduced through top–down planning and not embedded in daily routines, they tend to be underutilized even if they possess cultural, historical, or aesthetic qualities. The totem square in LJT village and the Martyrs Memorial Park in LJ village exemplify this pattern: they are visually distinctive but do not correspond to the rhythms of village life.

In contrast, the wind-and-rain bridge, the pavilion, and the courtyard of the village committee office show how public spaces gain meaning through everyday use. These places have gradually formed around villagers’ routines, such as resting during farm work, talking in the evening, selling small amounts of produce, or handling simple administrative matters. Because these spaces support daily activities rather than interrupt them, villagers express higher satisfaction and a stronger sense of attachment.

The comparison demonstrates that usability of public space is fundamentally relational: it depends on how well spatial form corresponds to habitual action, social norms, and daily rhythms within the village.

5.3. Environmental and Cultural Quality in Relation to Everyday Use

Across all demographic groups and all three villages, environmental and cultural dimensions received consistently high ratings. Attributes such as safety, natural elements, material authenticity, and cultural expression were widely appreciated. Interviews reinforce this view, with villagers expressing recognition of cultural features embedded in built structures such as ancestral halls, bridges, or vernacular materials.

However, the results also show that environmental and cultural enhancements alone are insufficient to generate overall satisfaction with public spaces. This is particularly evident in LJT village and LJ village, where the reconstructed spaces incorporate rich cultural symbolism and aesthetic improvement, yet economic and social satisfaction remain low. In these contexts, high-quality environmental and cultural design cannot compensate for disrupted livelihoods or the lack of functional relevance to everyday life.

This finding highlights an important nuance within place–attachment theory, which is cultural expression and environmental familiarity contribute to symbolic attachment and emotional stability, but they do not automatically translate into active spatial engagement [56]. In traditional villages, cultural and environmental attributes serve as supportive components that enhance the experiential quality of public space, but they must be paired with economic opportunities and daily-use functions to produce holistic spatial satisfaction.

HC village offers an example of this synergy. Environmental comfort, vernacular continuity, and cultural recognition work together with stable livelihoods and daily embeddedness to elevate satisfaction across all four dimensions. The results therefore suggest that cultural and environmental qualities play complementary roles. They enrich meaning, support identity, and enhance aesthetic experience, and they become effective drivers of satisfaction only when they are grounded in functional and economic realities.

6. Conclusions

This study assessed the quality of public spaces in three traditional villages through an integrated mixed-methods approach. The results show that villagers’ evaluations of public spaces are shaped by a combination of environmental, social, cultural, and economic considerations, with distinct patterns emerging across different village contexts. While environmental and cultural attributes were consistently appreciated, the findings highlight the central importance of aligning public space development with local livelihood systems and everyday practices.

6.1. Summary of Main Findings

First, livelihood stability emerges as the most influential determinant of spatial satisfaction. In LJT village and LJ village, top–down reconstruction projects displaced agricultural land and failed to generate sustainable tourism income, leading to low satisfaction in economic and social dimensions despite improvements in aesthetics. Conversely, HC village, characterized by stable agricultural income, land-leasing arrangements, and diversified rural commerce, recorded significantly higher satisfaction across all four dimensions.

Second, villagers engage most actively with public spaces that are embedded in their daily routines. Spaces created mainly for tourism or commemoration were often seen as disconnected from daily life. In contrast, organically evolved or multifunctional places, such as the village committee office, supported routine social interaction and informal activities.

Third, although environmental and cultural qualities were evaluated positively across all villages, these attributes alone were insufficient to generate high overall satisfaction. Natural elements, safety, and cultural expression foster emotional attachment but cannot compensate for disrupted livelihoods or limited functional relevance.

In this sense, these findings suggest that the quality of public space in traditional villages is fundamentally relational. Spatial design, cultural symbolism, and environmental comfort all matter, but their effectiveness depends on whether they correspond to villagers’ economic realities and everyday practices.

6.2. Theoretical and Practical Contributions

By showing that villagers’ evaluations are deeply conditioned by livelihood security, the analysis broadens conventional understandings of spatial quality, which typically emphasize physical form or cultural expression, and instead situates the perception of public space within the realities of rural economic life. At the same time, the findings highlight the significance of everyday social practices, illustrating that public spaces in traditional villages gain their meaning through repeated, routine use rather than through design intention alone. In addition, the study empirically validates a four-dimensional measurement framework that incorporates environmental, social, cultural, and economic indicators, offering a more comprehensive and transferable tool for assessing the quality of public space in traditional village in China.

Beyond its theoretical contributions, this study offers practical insights into rural planning and development. The four-dimensional assessment framework provides a structured tool for evaluating the quality of public space from villagers’ perspectives, enabling planners and local governments to identify which aspects of public space function well and which require intervention. Rather than focusing solely on physical improvement or cultural symbolism, the findings underscore the importance of aligning public space design with local livelihoods and everyday practices.

In practical terms, the framework can support more context-sensitive planning decisions by highlighting the risks of tourism-oriented reconstruction that displaces productive land without generating sustainable income. It also suggests that multifunctional and organically used spaces, such as village committee courtyards or shaded gathering areas, should be prioritized and protected in rural renewal projects. By integrating social, cultural, and economic considerations into spatial evaluation, the framework can help guide more balanced and sustainable approaches to public-space development in traditional villages.

6.3. Implications

The findings of this study offer several important implications for rural revitalization and governance of public space. A central priority is ensuring that spatial interventions do not undermine villagers’ livelihoods; removing productive land without providing viable economic alternatives weakens the social foundation of rural communities and reduces participation in public life. Policies should therefore support multifunctional spaces that integrate rest, gathering, small-scale commerce, and agricultural practices, rather than prioritizing single-purpose or aesthetically driven designs. Strengthening infrastructure is also essential for improving the usability of public space, including public transportation, reliable utilities, and basic amenities. Additionally, meaningful community involvement in decision-making and maintenance, which can reduce mismatches between planning intentions and actual needs while simultaneously creating income opportunities for villagers.

For planners, architects, and local governments, the results underscore the necessity of designing public spaces that are closely aligned with villagers’ everyday rhythms and spatial practices. Effective public spaces are situated along habitual routes and embedded in routine activities, rather than positioned in visually symbolic but socially peripheral locations. Ecological and cultural authenticity must be maintained, but not at the expense of functionality or daily relevance. Finally, tourism-oriented development must be carefully balanced with local use; public spaces intended for visitors should also incorporate features that benefit villagers to prevent disconnection and underuse.

This study offers insights based on three traditional villages in Chongqing, but the limited sample size means that the findings should be interpreted with caution. Traditional villages in other regions may differ in social organization, economic conditions, and cultural practices, which could influence how public spaces are perceived and used. Future research should therefore expand the sample to villages in different provinces. A broader dataset would help verify the applicability of the proposed assessment model and refine the indicators to better reflect the diversity of rural contexts in China. In addition, from a statistical perspective, the limited number of cases restricts the generalizability of the findings. Future studies could expand the sample across multiple regions and adopt larger-scale survey designs to further validate the assessment model and examine regional variation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.W. and Y.G.; methodology, W.W. and Y.G.; software, W.W. and Y.C.; validation, W.W. and Y.C.; formal analysis, W.W. and Y.G.; investigation, W.W., J.Z. and L.Z.; resources, W.W. and L.D.; data curation, W.W.; writing—original draft preparation, W.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.G.; visualization, W.W. and Y.C.; supervision, Y.G. and L.D.; project administration, Y.G. and L.D.; funding acquisition, W.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Scientific and Technological Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission, grant number KJQN202500720; Chongqing Jiaotong University Scientific Research Start-up Project, grant number F1240003; Humanities and Social Sciences Research Project of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission, grant number: 20JD060; Student Innovation Training Project of Chongqing Jiaotong University, grant number X202510618028.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

Jieying Zeng is employed by Chongqing Rail Transit Design and Research Institute Co., Ltd. Lingfei Zhou is employed by Chongqing Aotong Environmental Technology Co., Ltd. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Note

| 1 | Revolutionary culture originates from the long revolutionary course of the Chinese people, specifically encompassing the cultural forms that emerged during the periods of the Agrarian Revolutionary War, the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, and the War of Liberation. In this research, revolution culture is related to the War of Liberation from June 1946 to June 1950. |

References

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, Y. Appraisal and selection of “Chinese traditional village” and study on the village distribution. Arch. J. 2013, 12, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, S.; Cao, W.; Cao, C. The concept and cultural connotation of traditional villages. Urban Dev. Stud. 2014, 21, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Li, G. The research of the rural public space evolution and characteristics under the function and form perspectives. Urban Plan. Int. 2013, 28, 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Q.; Mou, P.; Xu, H. Analysis of Public Space in Youyang Traditional Villages from the Pattern Language Perspective. New Archit. 2022, 5, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Jiang, M.; Su, Y.; Jiang, Z. An Implicit System of Public Space in Contemporary Villages: A Case Study in Hunan. Archit. J. 2016, 8, 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Ju, S.; Wang, W.; Su, H.; Wang, L. Intergenerational and gender differences in satisfaction of farmers with rural public space: Insights from traditional village in Northwest China. Appl. Geogr. 2022, 146, 102770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alameddine, Z.A. The Role of Public Space in Post-War Reconstruction: The Case of the Redevelopment of Beirut City Centre, Lebanon. Annexe Thesis Digitisation Project 2017 Block 15. 2004. Available online: https://era.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/26624?show=full (accessed on 31 January 2018).

- Zhang, N. Twilight of the Land: An Analysis of Micro-Rights in China’s Rural Experience; China Renmin University Press: Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J. Life Between Buildings; The Danish Architectural Press: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gnanasambandam, S. Study of the perceived functions and the quality of physical boundaries of public spaces. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2020, 14, 233–250. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, F.; Valcuende, M.; Matzarakis, A.; Cárcel, J. Design of natural elements in open spaces of cities with a Mediterranean climate, conditions for comfort and urban ecology. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 26643–26652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, S. Public Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. Study on Rural Whole-Village Crime and Governance. Master’s Thesis, Nanchang University, Nanchang, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, J.; He, J.; Tang, H. The vitality of public space and the effects of environmental factors in Chinese suburban rural communities based on tourists and residents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Sima, L. Analysis of outdoor activity space-use preferences in rural communities: An example from Puxiu and Yuanyi village in Shanghai. Land 2022, 11, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L. Women, public Space, and mutual aid in rural China: A case study in H village. Asian Women 2012, 28, 75–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Buranaut, I. Age-friendly Rural Communities: A Multi-Case Study on Public Space Innovations for Active Aging. J. Community Dev. Res. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2025, 18, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Refined Design Research on Public Space of Visitor Center. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing University, Nanjing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Y. Research on the Optimizing Strategy of the Public Space of Traditional Town in Sichuan & Chongqing. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S. Research on the Color Landscape of Urban Public Space. Master’s Thesis, Southwest University, Chongqing, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y. Application of Emotion Design in Public Space. Packag. Eng. 2017, 38, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, N.; Nourian, P.; Pereira Roders, A.; Bunschoten, R.; Huang, W.; Wang, L. Investigating rural public spaces with cultural significance using morphological, cognitive and behavioural data. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2023, 50, 94–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xie, B.; Zeng, Y.; Liu, A.; Liu, B.; Qin, L. Intergenerational Transmission of Collective Memory in Public Spaces: A Case Study of Menghe, a Historic and Cultural Town. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birer, E.; Adem, P.Ç. Role of public space design on the perception of historical environment: A pilot study in Amasya. Front. Archit. Res. 2022, 11, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Káposzta, J.; Nagy, H. The major relationships in the economic growth of the rural space. Eur. Countrys. 2022, 14, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataya, A. The impact of rural tourism on the development of regional communities. J. East. Eur. Res. Bus. Econ. 2021, 2021, 652463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Kong, X. Tourism-led commodification of place and rural transformation development: A case study of Xixinan village, Huangshan, China. Land 2021, 10, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanan, L.; Ismail, M.A.; Aminuddin, A. How has rural tourism influenced the sustainable development of traditional villages? A systematic literature review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. The core of China’s rural revitalization: Exerting the functions of rural area. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2020, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.L.; Fan, D.X.; Wang, R.; Ou, Y.H.; Ma, X.L. Does rural tourism revitalize the countryside? An exploration of the spatial reconstruction through the lens of cultural connotations of rurality. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2023, 29, 100801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shach-Pinsly, D.; Shadar, H. The public open space quality in a rural village and an urban neighborhood: A re-examination after decades. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, D. Human-centered urban public spaces. Urban Plan. Forum 2006, 5, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C.; Yang, B. Design of Staying Space & Emergence of Public Life—The study on Jan Gehl’s Theory of Public Space Design (Part 2). Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2012, 28, 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Aljabri, H. The Planning and Urban Design of Liveable Public Open Spaces in Oman: Case Study of Muscat. Ph.D. Thesis, Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X. Research on the Design Strategy of Public Art Interveningin Rural Public Space Facilities. Packag. Eng. 2025, 46, 372–376. [Google Scholar]

- Van Oostrum, M. Appropriating public space: Transformations of public life and loose parts in urban villages. J. Urban Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2022, 15, 84–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, Z. The Public Dilemma of Rural Public Space and Its Reconstruction. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 2, 1–7+163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Dang, A.; Song, Y. Defining the ideal public space: A perspective from the publicness. J. Urban Manag. 2022, 11, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntakana, K.; Mbanga, S.; Botha, B. The Significance of Safety and Security in Urban Public Space Design for Sustainability. J. Public Adm. 2022, 57, 262–271. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, X.; Ma, L.; Tao, T.; Zhang, W. Do the supply of and demand for rural public service facilities match? Assessment based on the perspective of rural residents. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 82, 103905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Qian, J.; Cai, W. Discussion on mixed use of rural residential land research framework. J. Nat. Resour. 2020, 35, 2929–2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Ye, J. Hollow Lives: Women Left Behind in Rural China. J. Agrar. Change 2016, 16, 50–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, S.; Lei, D.; Chan, F.Y.; Tieben, H. Public space usage and well-being: Participatory action research with vulnerable groups in hyper-dense environments. Urban Plan. 2022, 7, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, K. Being together in urban parks: Connecting public space, leisure, and diversity. Leis. Sci. 2010, 32, 418–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X. Study on the Pavement Design of Urban Public Space. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Marusek, S.; Wagner, A. Public art and the mural: Interpreting public memory through prominence, place, and color. Law Cult. Humanit. 2024, 17438721241300651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soszyński, D.; Sowińska-Świerkosz, B.; Kamiński, J.; Trzaskowska, E.; Gawryluk, A. Rural public places: Specificity and importance for the local community (case study of four villages). Eur. Plan. Stud. 2022, 30, 311–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, H.; Huang, M. Public Waterfront Space Design Practice of the East Bund of the Huangpu River in Shanghai. Archit. J. 2019, 8, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, X.; He, J.; Liu, M.; Morrision, A.M.; Wu, Y. Building rural public cultural spaces for enhanced well-being: Evidence from China. Local Environ. 2024, 29, 540–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q. The Reconstruction Strategy of Rural Public Space in Zhaoqing under the Background of Rural Revitalization. Acad. J. Humanit. Social. Sci. 2023, 6, 142–147. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, G.; Yang, Q. The spatial production of rural settlements as rural homestays in the context of rural revitalization: Evidence from a rural tourism experiment in a Chinese village. Land Use Policy 2023, 128, 106600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Fan, B.; Tan, J.; Lin, J.; Shao, T. The spatial perception and spatial feature of rural cultural landscape in the context of rural tourism. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B. Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis: Understanding Concepts and Applications; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Q.; Ding, Z.; Li, M.; Gu, J. Beyond the horizon: Unveiling the impact of 3D urban landscapes on residents’ perceptions through machine learning. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 177, 113736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inalhan, G.; Yang, E.; Weber, C. Place attachment theory. In A Handbook of Theories on Designing Alignment Between People and the Office Environment; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 181–194. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).