Abstract

Anthropogenic disturbances and morphological constraints pose significant threats to lake–wetland functions. However, conventional assessments often overlook the influence of wetland morphology on the spatial realization of ecosystem services, which limits effective ecological restoration. This study presents a multidimensional framework coupled with the InVEST model to evaluate the Integrated Ecosystem Service Capacity (IESC) in the Jianghan Lake Cluster. The assessment focuses on key ecosystem services, such as habitat quality, carbon storage, and water purification. The results reveal significant morphology-driven heterogeneity in IESC. Zonal optimization strategies, including ecological water replenishment, buffer-strip construction, and polder-to-lake conversion, significantly enhance IESC across conservation, regulation, and restoration zones. Model simulations indicate that these targeted interventions can reduce non-point source pollution by approximately 35%, and increase carbon sequestration and biodiversity indices by 15–20% and 30%, respectively. This study elucidates the coupling mechanisms between lake morphology and ecosystem service capacity and provides a spatial framework for restoring “lake–river–polder” composite wetland systems.

1. Introduction

Wetland ecosystem services (WES) form a vital link between natural ecological processes and human well-being. WES supports key functions, such as climate regulation, water purification, habitat provision, and carbon sequestration. Over recent decades, research on ecosystem services has expanded into a multidimensional framework integrating diverse theoretical and methodological perspectives. Key approaches, including functional classifications of ecosystem services [1], models integrating service supply and demand [2], and analyses of service trade-offs and synergies [3], have contributed to the development of comprehensive theories and evaluation methods. However, most existing studies have mainly focused on quantifying the magnitude of ecosystem service functions, with limited research on their spatial distribution and underlying response mechanisms. Consequently, these studies provide insufficient insights into the spatial heterogeneity and disturbance patterns of ecosystem services across different landscape units [4,5].

In recent years, Integrated Ecosystem Service Capacity (IESC) has received increasing attention as a framework for assessing service supply and spatial suitability in ecological spaces [6]. Previous studies have mainly used models such as Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Trade-offs (InVEST) and ARIES to simulate key services, including carbon storage, habitat quality, and water purification [7,8]. However, systematic research on the coupling among wetland morphology, stress intensity, and service efficiency remains limited. Particularly, the mechanisms by which distinctive morphological types (such as enclosed or in-dyke lakes) constrain the spatial efficiency of ecosystem services in lacustrine wetlands remain unclear.

Compared with conventional assessments that quantify individual ecosystem service functions, the evaluation of IESC highlights the spatial configuration and combined performance of multiple services [9,10]. In recent years, research has increasingly shifted from single-service quantification toward integrated service optimization, including analyses of service synergies, trade-offs, spatial patterns, and scenario-based simulations [11,12]. Nevertheless, most studies have been limited to regional-scale assessments, and the coupling mechanisms between wetland morphology and service capacity remain underexplored. This gap is particularly evident in wetland systems, in which the spatial constraints of landscape features on IESC have yet to be systematically examined.

The Jianghan Lake Cluster was selected as the study area owing to its representativeness and the urgent need for targeted restoration. This lake, located in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River, represents a typical “lake–river–polder” composite wetland system. This wetland system plays a vital role in regional ecological security through flood regulation, water purification, and carbon sequestration [13,14]. Additionally, this region serves as a key unit for ecological regulation and biodiversity maintenance within the Yangtze River Basin. Notably, the wetland exhibits pronounced morphological heterogeneity, with a sharp contrast between natural lakes and highly regulated enclosed polder lakes. However, long-term human disturbances—including polder reclamation, aquaculture, and agricultural non-point source pollution—have led to widespread ecological degradation, reduced service capacity, and increased ecological security risks in in-dyke lakes. Consequently, wetland ecosystem service capacity has significantly decreased. These morphological constraints make the Jianghan Lake Cluster an ideal system for investigating the coupling mechanisms between lake morphology and IESC, which is the core objective of this study. Previous studies have mainly focused on quantifying and assessing wetland ecosystem functions at regional scales. Although these studies examine the spatiotemporal distribution of major services, they provide limited insights into the mechanisms underlying service formation and spatial allocation. Models such as InVEST are widely utilized but cannot capture fine-scale morphological constraints owing to their reliance on generalized input parameters. In “lake–river–polder” systems, characterized by complex morphologies and heterogeneous hydrological connectivity, conventional functional assessments cannot capture the intrinsic coupling between ecological processes and spatial structure. This limitation reduces the relevance of these assessments for restoration and management. Therefore, investigating the mechanism by which wetland morphological characteristics influence the spatial configuration and supply of ecosystem services is crucial for enhancing regional ecosystem performance and guiding targeted restoration strategies. Developing an integrated analytical framework linking wetland morphology to IESC is vital for elucidating the mechanisms underlying observed service patterns. This framework provides a scientific basis for zonal restoration, capacity optimization, and ecological security enhancement in plain lake regions such as the Jianghan Lake Cluster.

Building on these considerations, this study presents a multidimensional framework for evaluating WES in the Jianghan Lake Cluster, including carbon storage, habitat quality, water purification, and soil retention. By integrating the InVEST model with spatial statistical approaches, we analyze the spatial distribution of ecosystem services and their coupling with lake morphology. Areas with varying service efficiency and their key limiting factors are identified, and optimization strategies are developed for conservation, regulation, and restoration areas. This study aims to establish an IESC assessment framework for lacustrine wetlands. The coupling mechanisms between lake morphology and the spatial heterogeneity of ecosystem services are elucidated. Additionally, efficiency optimization strategies are developed for distinct functional zones. The findings provide quantitative and practical guidance for ecological restoration, spatial management, and service efficiency enhancement in the Jianghan Lake Cluster and comparable lake–wetland systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area Overview

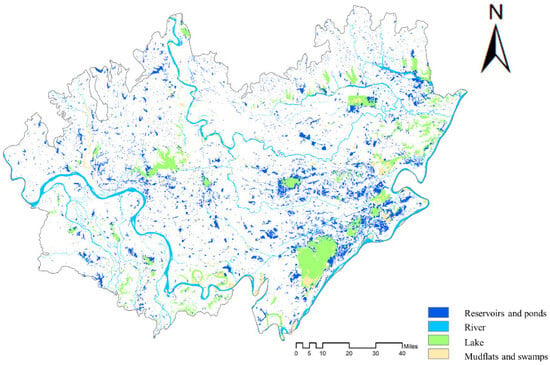

The Jianghan Plain, located in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River, is a key geomorphological unit in central China. Geographically, this plain lies in the south-central part of Hubei Province, bounded by the southern foothills of the Dahong Mountains to the north and the eastern extensions of the Dabie Mountains to the east. Additionally, the region is bordered by the hilly areas of western Hubei to the west and the main stem of the Yangtze River to the south, forming a basin-shaped terrain enclosed on three sides and open to the south. The Jianghan Plain, a compound alluvial plain shaped by both the Yangtze and Han Rivers, was formed through continuous tectonic subsidence after the Yanshan Movement in the Mesozoic era. Subsequent sediment deposition by the Yangtze, Han, and their tributaries throughout the Quaternary period (approximately 2.6 million years ago to the present) gradually filled the basin. This process formed a vast lowland plain of ~40,000 km2, with an average elevation of only 20–30 m. Therefore, the Jianghan Plain is one of China’s least extensive alluvial plains. The plain features a dense fluvial network, with a drainage density of 0.5–1.2 km per km2. The intersection of the Yangtze and Han Rivers gives rise to a confluence zone with a pronounced bifurcation pattern, geometrically resembling an inverted letter “Y”. The tributaries of these rivers—such as the Dongjin and Tongshun Rivers—interlace with numerous scattered lakes, creating a distinctive “interwoven river and dotted lake” wetland landscape. Historically, the Jianghan Plain was known as the “Province of a Thousand Lakes”. Today, over one hundred lakes with surface areas exceeding 1 km2 remain, including Honghu, Changhu, and Liangzi Lakes. Moreover, water bodies still cover over 10% of the total area. These lakes serve as crucial flood-regulation and storage basins in the middle Yangtze Basin, with a combined storage capacity exceeding 3 billion m3. Additionally, the lakes contribute to the regional hydrological cycle through surface–groundwater interactions, establishing a unique “lake–river–groundwater” hydrological connectivity. This study focuses on the wetland systems in the southeastern core of the Jianghan Plain, which contains the Jianghan Lake Cluster. The spatial distribution of various wetland types in the lake cluster is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Spatial distribution of various wetland types in the Jianghan Lake Cluster.

2.2. Data

The data system used in this study comprises five categories of datasets and parameters, which support the parameterization and operation of the InVEST submodules. (1) Land-use data: Land-use maps were obtained from the Chinese National Land Use and Cover Change (CNLUCC) dataset at a resolution of 30 m × 30 m. The dataset from the Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, was used to classify land-use types, delineate wetland spatial distributions, and identify habitat threat sources. The dataset served as the unified land-cover base map for the habitat quality, Nutrient Delivery Ratio (NDR), Sediment Delivery Ratio (SDR), and carbon-storage modules. (2) Geospatial data: Topographic data were obtained from the ASTER GDEM dataset (30 m × 30 m) via the geospatial data cloud platform. These data were used to delineate sub-basins and river networks and derive terrain factors such as slope and flow accumulation. These factors provide the topographic framework for simulating water-purification and soil-retention processes. (3) Climatic data: Annual precipitation data (30 m × 30 m) were obtained from the National Earth System Science Data Center. These data were used to calculate rainfall-erosivity factors (R) or equivalent rainfall drivers required for the water-purification and soil-retention modules. (4) Carbon-pool parameters: Carbon-density values were compiled from the National Ecosystem Science Data Center and the InVEST model documentation (statistical parameters without fixed spatial resolution). Four types of carbon pools—aboveground biomass, belowground biomass, dead organic matter, and soil organic carbon—were assigned to each land-use category for carbon-storage simulations. (5) Biophysical parameters: According to the InVEST model guidelines, biophysical parameters were defined for each land-use type. These included nutrient-export coefficients, maximum retention efficiencies, and critical retention distances, which support water-purification simulations. All datasets were resampled to a uniform spatial resolution and aligned within a consistent coordinate framework. Overall, these datasets form an integrated data framework for land-cover classification, terrain analysis, rainfall input, and parameter assignment in evaluating WES in the Jianghan Lake Cluster. The data used in this study are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Datasets used in this study.

2.3. Methods

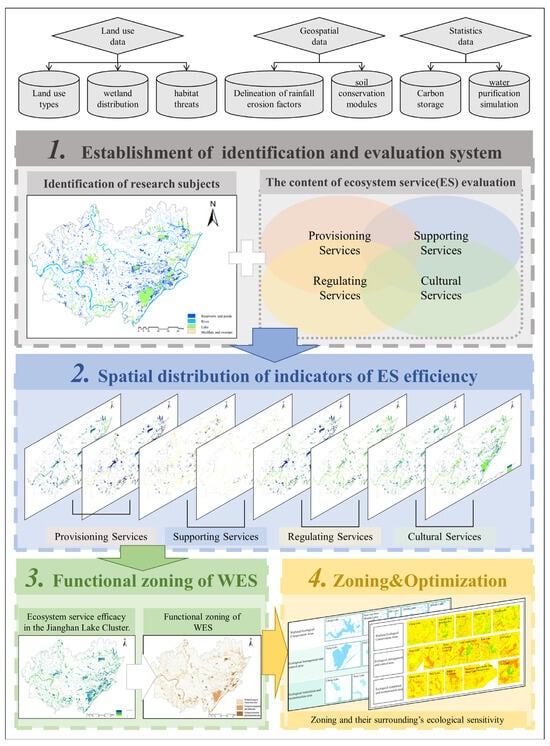

Wetlands are classified into four functional types (riverine, lacustrine, reservoir, and pond) to maintain modeling consistency and ensure computational feasibility within the integrated assessment framework. Although this classification simplifies finer variations in wetland size and management history, it remains appropriate because it captures the major hydrological and morphological contrasts. These contrasts drive change in ecosystem service capacity across the study area. This approach preserves the key morphological heterogeneity (natural vs. enclosed) required for the subsequent coupling analysis. The workflow for evaluating and optimizing wetland IESC in the Jianghan Lake Cluster is shown in Figure 2. According to the established evaluation framework and the ecological characteristics of the study area, a multidimensional assessment system was developed. The system incorporates eight core indicators, including habitat quality, carbon storage, and water purification. The InVEST model was used to quantitatively evaluate key ecosystem services, including habitat quality, water purification, and carbon storage. Additional indicators were assessed using value-based methods and integrated with the InVEST outputs to map the spatial distribution of overall IESC. The spatial patterns of wetland morphology were coupled with IESC to identify functional zones within the Jianghan Lake Cluster. The area was classified into ecological conservation, ecological regulation, and ecological restoration zones. Moreover, corresponding optimization strategies were developed. Conservation zones should prioritize limiting urban development, protecting and restoring wetlands, establishing ecological monitoring networks, and ensuring ecological water replenishment. Overall, this methodological framework provides a systematic approach for quantifying IESC and supporting spatially differentiated wetland restoration and management.

Figure 2.

Technical Roadmap for evaluating WES in the Jianghan Lake Cluster.

2.3.1. Principles of the InVEST Model

The InVEST model, developed by the Natural Capital Project, is a spatially explicit tool designed to quantify ecosystem service supply and spatial distribution at the pixel scale. The model mainly uses land use and land cover (LULC) data as input. The model integrates topographic, climatic, soil, and ecological parameters to evaluate multiple ecosystem services, including carbon storage, habitat quality, water purification, and soil retention [15,16,17].

In this study, four core submodules of InVEST were used:

(1) Carbon-Storage Module: This module estimates carbon stock for each land-use type using carbon-density parameters, enabling spatial analysis of regional carbon-sequestration patterns.

(2) Habitat Quality Module: This module quantifies habitat degradation through the integration of data on threat sources, habitat sensitivity, and distance-decay functions. The module generates a habitat-quality index, thereby identifying degradation hotspots and conservation-priority zones.

(3) NDR Module: This module simulates the export and retention of nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus across different land-use types. The module quantifies the ability of wetlands to mitigate non-point source pollution.

(4) SDR Module: This module assesses soil erosion and retention across land-use types based on the Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation (RUSLE).

Model parameters were mainly obtained from the official InVEST User Guide [18] and relevant domestic and international studies [19,20,21]. These parameters were localized to reflect the geographical characteristics of the Jianghan Lake Cluster [22]. Detailed theoretical formulations and computational algorithms of InVEST are provided by Wen Li et al. [23].

2.3.2. Data Processing

All spatial datasets—including CNLUCC land-use data, ASTER GDEM, and annual precipitation—were first quality-checked in ArcGIS 10.8. The datasets were re-projected to a unified coordinate system, resampled to a 30 m × 30 m resolution, clipped to the study-area boundary, and aligned at the pixel level. DEM was processed using depression-filling. Subsequently, slope, flow direction, and flow-accumulation layers were generated to delineate sub-basins and extract the river-network base maps.

The CNLUCC dataset was reclassified into the LULC categories required by the InVEST model. Major wetland types, such as rivers, lakes, reservoirs/ponds, and tidal flats/marshes, were extracted to create a wetland mask. A key–value mapping table linking each LULC class to its corresponding model parameters was developed according to the InVEST guidelines.

Annual precipitation data were resampled and spatially aligned with the DEM and LULC layers. The rainfall-erosivity factor (R) was calculated according to the InVEST model documentation for use in both the NDR and SDR modules. Additionally, comprehensive consistency and completeness checks were performed, including verification of coordinate systems, resolution, pixel alignment, code uniqueness, and parameter coverage. The standardized LULC, DEM, and precipitation raster datasets, along with the parameter tables, were exported as the formal inputs for each InVEST submodule.

2.3.3. Selection of Wetland IESC

Since the early 21st century, the release of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) has marked a significant advancement in the classification and standardization of ecosystem services. The MA [24] framework categorizes ecosystem services into four groups—provisioning, regulating, cultural, and supporting services—providing a more intuitive and widely applicable structure. This framework has become an authoritative reference for evaluating wetland ecosystem service values. Considering the ecosystem service functions, natural conditions, socio-economic setting, and ecological restoration goals of the Jianghan Lake Cluster, an indicator framework was developed to assess wetland IESC. The framework—guided by scientific validity, feasibility, and local adaptability—defines four main WES categories with eight key indicators. These indicators capture the multidimensional service performance of the region in carbon storage, habitat quality, water purification, and soil retention.

Detailed descriptions of the categories, indicators, and corresponding variables are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Evaluation indicators for ecosystem services.

Considering the primary ecological functions of the Jianghan Lake Cluster wetlands, provisioning and supporting services were assigned the highest weights in the evaluation framework. Weighted overlay analysis was then used to calculate the coefficient of each indicator, providing a quantitative basis for assessing overall IESC. This approach enables a comprehensive and objective evaluation of the wetland ecosystem service performance in the Jianghan Lake Cluster.

2.3.4. Determination of Evaluation Indicator Weights

The eight ecosystem service indicators were calculated as follows:

(1) Carbon Storage

Carbon storage in ecosystems involves the accumulation of carbon in vegetation, organic matter, and soil. Through the sequestration of atmospheric CO2, ecosystems capture greenhouse gases and convert them into ecological value through carbon-storage services. Particularly, wetland ecosystems are highly effective in carbon accumulation and serve as natural carbon sinks.

In this study, the Carbon-Storage module of the InVEST model was used to quantify carbon stocks across different wetland types in the Jianghan Lake Cluster. The calculation involved several steps:

First, the carbon content of four key pools—soil carbon, litter organic carbon, aboveground biomass, and belowground biomass—was determined for each wetland type. Subsequently, a spatial overlay analysis was conducted to integrate these pools and estimate the total carbon storage of the wetland ecosystems.

The carbon-pool parameters for the various wetland types were obtained from datasets on carbon-sequestration ecosystem services in the Yangtze River Economic Belt [25,26]. These parameters were adjusted to reflect the biophysical properties of the Jianghan Lake Cluster. The biomass values (t·hm−2) for each wetland type are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Carbon-pool parameter values for various wetland types in the Jianghan Lake Cluster.

(2) Habitat Quality

Habitat quality was assessed using the Habitat Quality module of the InVEST model. This module evaluates ecosystem stability based on the spatial intensity of ecological threats (such as agricultural and construction land) and their interactions with habitat sensitivity. According to these inputs, the model simulates the spatial distribution of habitat quality and degradation across the Jianghan Lake Cluster (Table 4 and Table 5).

Table 4.

Habitat quality of wetland types relative to sensitivity to threat factors.

Table 5.

Relative weights, maximum influence distances, and spatial decay types of threat factors.

The simulation results indicate a strong spatial correlation between areas of high habitat quality and biodiversity hotspots. In contrast, areas with low-habitat quality correspond to regions with higher ecological vulnerability and reduced resilience. Detailed descriptions of the model parameters and computational algorithms are provided in the relevant literature [27,28].

(3) Water Purification Simulation

Wetland systems remove nitrogen and phosphorus pollutants through a synergistic combination of physical, chemical, and biological processes. Mechanisms such as adsorption and interception, plant uptake, substrate filtration, and microbial degradation create a multi-stage cascade that enables efficient nutrient removal. In this study, the NDR module of the InVEST model was used to quantify the water-purification service of the Jianghan Lake wetlands through simulation of the spatial distribution of total nitrogen (TN) export. The model assesses the influence of landscape characteristics on nutrient transport and retention and estimates the effectiveness of wetlands in mitigating non-point source pollution.

The simulation results revealed a strong negative correlation between TN export and purification efficiency. This confirms that TN export is a key indicator of wetland water-purification function. The model parameters for the Jianghan Lake Cluster are summarized in Table 6. Detailed algorithmic procedures are provided in the cited references [29,30,31].

Table 6.

Biophysical parameter values for the wetland water-purification service assessment model of the Jianghan Lake Cluster.

(4) Soil Retention Simulation

Soil erosion in the Jianghan Lake Cluster wetlands was analyzed using the SDR module of the InVEST model. This module integrates global hydrological datasets with empirical soil-erosion models to simulate soil particle movement. The module assesses the effects of hydrological conditions on erosion intensity and the dynamics of sediment transport and export [32]. The model inputs included soil parameters specific to the Jianghan Plain (Table 7) and precipitation and topographic data representing regional soil types, hydrological regimes, and terrain features. These inputs enabled the spatial quantification of soil erosion and retention, providing the basis for assessing the soil-conservation function of the wetland ecosystem.

Table 7.

Cover-management and conservation-practice factor values for wetland soil erosion in the Jianghan Lake Cluster.

During the simulation, the InVEST SDR module was used to model soil-erosion dynamics under varying hydrological conditions. The simulation incorporated three key processes:

(a) Infiltration: Rainfall infiltrates the soil surface. The combined effects of gravity and hydraulic forces mobilize soil particles and promote surface runoff erosion.

(b) Ecological Weathering: Vegetation mitigates erosion through raindrop interception and soil aggregate stabilization. Soil structural properties determine erosion resistance.

(c) Sediment Export: Detached soil particles are transported by wind and water, contributing to sediment yield at the watershed outlet.

The annual soil erosion volume of the Jianghan Lake Cluster wetlands was quantitatively simulated using the InVEST SDR module. The annual soil-erosion values were inversely normalized (i.e., higher erosion corresponds to lower soil-retention efficiency) to map soil-retention efficiency across the Jianghan Plain.

(5) Regulating Services

According to existing literature and field investigations, this study systematically developed a classification and valuation framework for regulating services. The framework focuses on two main components: climate regulation and hydrological regulation. Indicator weights were adjusted to reflect functional differences among wetland types. For example, small and medium-sized shallow lakes were assigned higher weights for flood-regulation capacity. In contrast, marsh wetlands were prioritized for their superior carbon-sequestration potential.

Climate-regulation services were further classified into two categories: local and global climate regulation. Each category was assessed according to the functional characteristics and biophysical attributes of the wetlands [2,33].

Local climate regulation was evaluated using indicators such as evapotranspiration capacity, air-humidity regulation efficiency, and local temperature-buffering potential. These indicators were quantified using remote-sensing data (e.g., land surface temperature and vegetation coverage) and ground-based meteorological observations (e.g., humidity and temperature records) to assess the influence of wetlands on surrounding microclimates.

Global climate regulation capacity was assessed based on carbon-sequestration ability (e.g., total carbon fixation and CO2 uptake rate) and the balance of greenhouse-gas emissions (e.g., methane fluxes). Wetland carbon-sequestration potential was estimated through integration of vegetation composition (such as reed and marsh species) and soil organic matter content with a carbon-density model. In the Jianghan Lake Cluster, small and medium-sized lake wetlands exhibited high carbon-fixation efficiency owing to their diverse plant communities.

Hydrological regulation services were classified into flood control and groundwater recharge and evaluated using both hydrological and socio-economic data. Flood-regulation capacity was assessed using indicators such as storage volume (wetland area and average depth), peak-flow attenuation rate, and flood-retention duration. These indicators were quantified through the analysis of historical flood records and the comparison of flood-retention performance across wetland types. Groundwater-recharge capacity was evaluated using indicators such as recharge rate, groundwater-level variations, and water-purification efficiency. A water-balance model combined with groundwater-monitoring data was used to quantify the contribution of wetlands to infiltration-driven groundwater recharge.

(6) Cultural Services

To assess cultural services in the Jianghan Lake Cluster wetlands, these services were categorized into two main dimensions: intrinsic biodiversity value and recreational and aesthetic value. Four wetland types—rivers, lakes, reservoirs/ponds, and tidal flats/marshes—were evaluated, with value assignments differentiated based on their ecological, aesthetic, and experiential characteristics. Intrinsic biodiversity value reflects the cultural and ethical significance of conserving species and habitats. This highlights the non-material contributions of wetlands to human perceptions of nature and ecological conservation. Recreational and aesthetic value captures benefits from landscape valuation, ecotourism, and educational experiences provided by wetland ecosystems. The assigned effectiveness values for cultural services across different wetland types in the Jianghan Lake Cluster are presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Assigned effectiveness values of cultural services in the Jianghan Lake Cluster.

Intrinsic biodiversity value was evaluated using three core indicators. These included species richness (e.g., number of wetland-endemic species), endangered-species protection level (e.g., proportion of species listed in the IUCN Red List), and ecosystem integrity (e.g., food-web complexity and stability of keystone species). These indicators were derived from field biodiversity surveys, including avian and fish census data across the Jianghan Lake Cluster. The indicators were further supported by vegetation-cover analysis from remote-sensing data and documented wetland restoration outcomes from the Comprehensive Lake Protection Plan of Jianghan District. Indicator weights were adjusted according to wetland type. For example, lacustrine wetlands (such as shallow lakes in the Jianghan region) exhibited high habitat connectivity and were assigned greater biodiversity weights. This weighting was based on successful conservation cases, such as the habitat restoration of the endangered Aythya baeri (Baer’s Pochard) in Liangzi Lake. Conversely, tidal-flat wetlands support unique intertidal species but face higher anthropogenic disturbances, necessitating sensitivity-based adjustments in their assigned values.

The recreational and aesthetic value was assessed using two categories of indicators: functional and perceptual. Functional indicators included landscape uniqueness (e.g., seasonal waterbird spectacles), tourism attractiveness (e.g., visitor numbers and tourism revenue), and cultural–educational functions (e.g., number of wetland education and outreach centers). Perceptual indicators were quantified using social-media analytics, including the popularity of photos and the frequency of aesthetic-related keywords in online comments. Differentiated value assignments were applied across wetland types. Reservoir and pond wetlands, dominated by artificial landscapes, exhibited higher recreational functionality but lower aesthetic value. Consequently, weight adjustments consistent with the functional orientation of these wetlands were applied. In riverine wetlands, the combination of linear waterfront landscapes and recreational activities was evaluated using the “riverside leisure belt” valuation model developed for the Pearl River Delta [34].

This multi-indicator framework enables rigorous quantification of cultural ecosystem service values and facilitates the integration of cultural dimensions into the overall IESC assessment of the Jianghan Lake Cluster wetlands.

2.3.5. Calculation of Wetland IESC in the Jianghan Lake Cluster

(1) Carbon Storage

According to land-use conditions and corresponding carbon-density data, the Carbon Storage and Sequestration module of the InVEST model was used to quantitatively evaluate the total ecosystem carbon stock of the Jianghan Lake Cluster. The carbon-storage value for each pixel was calculated as the sum of four main carbon pools—aboveground biomass, belowground biomass, dead organic matter, and soil organic carbon—using the following formula:

where represents the total carbon storage (t·hm−2); , , , and denote the carbon densities (t·hm−2) of aboveground biomass, belowground biomass, dead organic matter, and soil organic carbon, respectively.

(2) Habitat Quality

To calculate the Habitat Quality Index, habitat degradation () is first estimated using the Habitat Quality module. This measure reflects the cumulative impact of multiple threat sources on each habitat type. Habitat degradation is calculated using a sensitivity-weighted summation. Habitat types with higher sensitivity to specific threats exhibit greater degradation. Habitat degradation is calculated as follows:

Here,

represents a given threat factor;

denotes the total number of threat factors;

signifies the number of threat-source grid cells;

denotes the weighting coefficient of threat factor (0 ≤ ≤ 1);

quantifies the intensity of threat y;

describes the spatial influence of threat at distance ;

represents the legal accessibility level = 1;

reflects the sensitivity of habitat type j to threat ;

denotes the distance between grid cells x and y.

The maximum effective distance of threat is defined as .

Once degradation intensity () is calculated, the Habitat Quality Index () is derived using a half-saturation function:

where represents the habitat-quality score of cell x;

denotes the habitat-suitability score of land-cover type j;

indicates the degradation intensity of cell x;

indicates a model constant (set internally);

K denotes the half-saturation constant (default K = 0.5).

(3) Water Purification

The InVEST NDR model was used to simulate the water-purification service of the Jianghan Lake Cluster wetlands. This model quantifies the transport and retention of surface nutrients—nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P)—to evaluate the water-purification capacity of the ecosystem. The model further estimates the contribution of the Jianghan Lake Cluster to regional water-quality improvement.

(4) Soil Retention

The Soil Retention module of the InVEST model was used to assess soil-conservation efficiency in the target watershed based on an improved RUSLE framework. The soil-retention function includes two core dimensions:

(a) Reduction in soil erosion by surface vegetation: This is quantified as the difference between potential and actual soil loss.

(b) Sediment retention: The capacity of wetlands to trap and retain upstream sediments is calculated as the product of incoming sediment load and sediment-retention efficiency.

These indicators reflect the ability of wetland ecosystems to reduce erosion and maintain soil productivity across the Jianghan Plain.

(5) Regulating Services

The classification and valuation framework for regulating services was developed based on an integrated review of existing literature and field observations. The evaluation focused on two key functions: climate regulation and hydrological regulation. Indicator weights were adjusted according to functional differences among wetland types [35].

For example, small and medium-sized shallow lakes were assigned higher weights for flood-regulation capacity. In contrast, marsh wetlands were prioritized for their superior carbon-sequestration potential. This weighting scheme ensures that regulating-service assessments reflect the ecological differences among wetland types.

(6) Cultural Services

Cultural ecosystem services were classified into two main dimensions: intrinsic biodiversity value and recreational–aesthetic value.

Intrinsic biodiversity value was assessed using three core indicators: species richness, endangered-species protection level, and ecosystem integrity. Lacustrine wetlands (e.g., shallow lakes in Jianghan District) exhibit high habitat connectivity and were assigned higher biodiversity weights. In contrast, tidal-flat wetlands, which support unique intertidal species, are more vulnerable to anthropogenic disturbances. Therefore, the value scores of these wetlands were adjusted to reflect their ecological sensitivity.

For recreational and aesthetic values, key indicators included landscape uniqueness, tourism attractiveness, and cultural–educational significance. These were complemented by perception metrics derived from public engagement and social-media data to capture public aesthetic preferences for wetland landscapes [36].

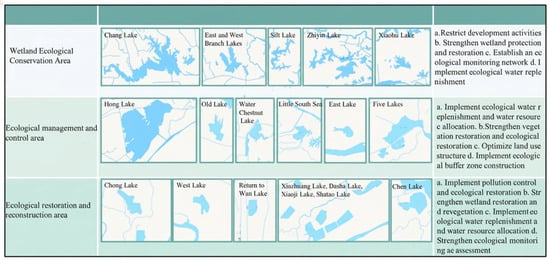

2.3.6. Ecological Sensitivity Assessment

Ecological sensitivity is the degree to which an ecosystem responds to anthropogenic disturbances and natural environmental changes and indicates its susceptibility to degradation. Ecological sensitivity reflects the likelihood and intensity of ecological impacts resulting from internal or external stressors. Regions with high ecological sensitivity respond strongly to even minor disturbances, potentially triggering significant declines in ecosystem functionality.

The ecological sensitivity assessment framework consists of a criterion layer and an indicator layer. The criterion layer comprises topographic factors and land-use types. The indicator layer includes five specific ecological factors. Sensitivity levels and their corresponding weights were assigned according to the standards in Table 9. This study utilized 30 m resolution DEM data (to derive slope, elevation, and aspect), Landsat-series satellite imagery (for calculating NDVI), and 2020 land-use data. All datasets were standardized to a consistent spatial reference system and resolution.

Table 9.

Criteria system for ecological sensitivity assessment.

On the ArcGIS platform, each factor was reclassified and assigned both sensitivity scores and weights according to Table 9. A weighted overlay analysis was used to calculate the composite ecological sensitivity index, expressed as:

where denotes the composite ecological sensitivity index, indicates the weight of the i-th factor, and represents its corresponding sensitivity score. Ecological sensitivity was categorized into five levels: (non-sensitive, low-sensitive, moderately sensitive, highly sensitive, and extremely sensitive) based on the calculated index.

3. Results and Analyses

3.1. Parameter Optimization and Calibration of the InVEST Model

During parameter optimization and calibration of the InVEST model, the Carbon-Storage module was used to quantify total ecosystem carbon stocks. These estimates were validated using carbon-pool data from the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Spatial overlay analysis revealed distinct carbon-pool densities (t·hm−2) among wetland types. River wetlands exhibit carbon-pool densities of 2.91, 0.81, 64.03, and 0.12 t·hm−2 for aboveground biomass, belowground biomass, soil carbon, and dead organic matter, respectively. Lakes displayed densities of 2.75, 0.50, 64.03, and 3.98 t·hm−2. Reservoirs and ponds had densities of 2.30, 0, 64.03, and 3.98 t·hm−2. Tidal-flat and marsh wetlands exhibited densities of 2.02, 1.28, 64.03, and 3.98 t·hm−2. The Habitat Quality module was applied using parameters from Table 3 and Table 4. Habitat-suitability scores were assigned as follows: 1.0 for rivers, 0.9 for lakes, 0.9 for reservoirs and ponds, and 0.6 for tidal flats and marshes. Threat factors were parameterized as urban land (weight 1.0, maximum impact distance 10 km, exponential decay), paddy and dry farmland (weight 0.3 each, distance 1 km, exponential decay), and roads (weight 0.4, distance 3 km, linear decay). Representative sensitivity coefficients were set at 0.80 and 0.45 for rivers under urban and road influences, respectively, and 0.85 and 0.50 for lakes. Water-purification capacity was simulated using the NDR module (Table 5). Nitrogen export and retention parameters were set to 0.11 kg·hm−2·a−1, 0.50, and 0.5 m for rivers, lakes, tidal flats, and marshes, respectively. For reservoirs and ponds, these parameters were 3.42 kg·hm−2·a−1, 0.25, and 0.25 m. These values enabled spatial modeling of TN export and confirmed its significant negative relationship with purification efficiency. Soil-retention processes were simulated using the SDR module. The module integrated regional soil, topographic, and precipitation data from the Jianghan Plain and was calibrated with RUSLE factors (Table 6). Vegetation-cover and crop-management factors and soil-conservation measures were set as follows: rivers (0.050 and 0.3), lakes (0.008 and 0), reservoirs and ponds (0.200 and 0.1), and tidal flats and marshes (0.420 and 0.2). According to these configurations, the model simulated infiltration, ecological weathering, and sediment-transport dynamics to estimate annual soil-erosion volumes. These volumes were then inversely normalized to characterize the spatial distribution of soil-retention efficiency across the Jianghan Plain.

3.2. Ecosystem Service Spatial Patterns and Integrated Efficiency Analysis

3.2.1. Spatial Distribution of Key Ecosystem Service Elements

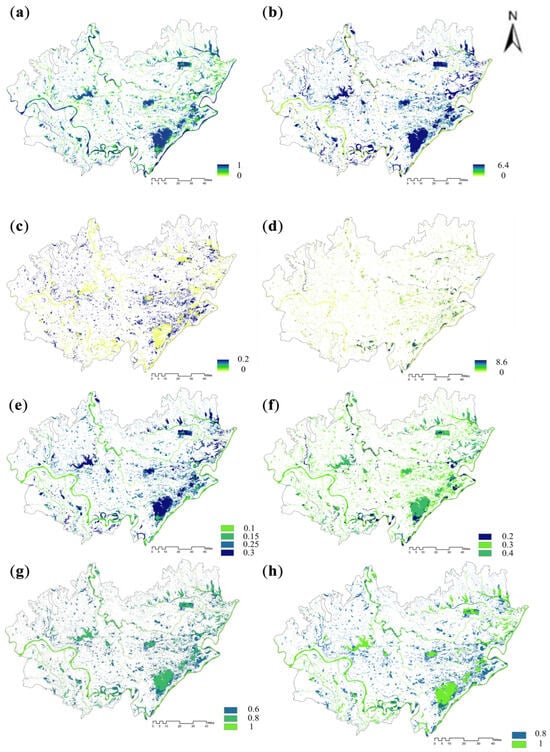

The spatial simulation of habitat quality in the Jianghan Lake Cluster revealed pronounced spatial heterogeneity (Figure 3a). Lakes and reservoirs exhibited the highest habitat quality. However, river channels, ponds, and the margins of in-dyke lakes displayed considerably lower habitat quality. Habitat quality patterns were strongly influenced by surrounding threat sources. Urban and rural construction lands caused the most pronounced disturbances. In contrast, agricultural areas such as paddy fields contributed to significant degradation along the shorelines of smaller lacustrine wetlands. The spatial distribution of carbon storage (Figure 3b) indicated that tidal flats, marshes, and lakes contained the largest carbon stocks, followed by reservoirs and ponds. River systems exhibited the lowest total carbon density. The spatial distribution of water-purification efficiency (Figure 3c) revealed that reservoirs and ponds had the highest nutrient-retention capacities among all wetland types. This pattern was mainly attributed to favorable hydrological conditions and enhanced sediment deposition. Terrain and rainfall-driven erosion further modulated purification potential. The spatial assessment of soil retention (Figure 3d) revealed a pronounced east–west gradient. Wetlands in the eastern Jianghan Plain exhibited stronger soil-conservation capacity than those in the west. This distribution reflects the combined effects of topography, soil texture, and erosion intensity. In some areas, sediment deposition from river channels altered local erosion–accretion dynamics, further influencing the overall soil-retention pattern.

Figure 3.

Spatial distribution of ecosystem service effectiveness in the Jianghan Lake Cluster wetlands. Note: Panels (a–h) represent the spatial distributions of (a) habitat quality, (b) carbon storage, (c) water-purification efficiency, (d) soil-erosion intensity, (e) climate-regulation efficiency, (f) water-regulation efficiency, (g) intrinsic biodiversity value, and (h) recreational–aesthetic value.

Climate-regulation services were categorized into local and global components and evaluated based on wetland functional differences (Figure 3e). The results indicated that lakes exhibited the highest climate-regulation efficiency, while rivers had the lowest regulation efficiency. Water-regulation services, including flood mitigation and groundwater recharge (Figure 3f), exhibited distinct spatial patterns. Tidal flats and marshes had relatively low storage capacity, mainly limited by their hydrological retention potential. Biodiversity values (Figure 3g) indicated that river wetlands supported the highest species richness, followed by lakes. This highlights the ecological role of both wetland types as key habitats within the wetland network.

Cultural services, particularly recreational and aesthetic values (Figure 3h), exhibited pronounced spatial variations among wetland types. Rivers and lakes demonstrated the highest cultural significance, reflecting their diverse natural landscapes, seasonal migratory-bird spectacles, and strong public appeal. The distinctive scenic character and higher tourist visitation of rivers and lakes significantly contributed to the regional ecotourism economy. These features were further supported by well-developed infrastructure, such as viewing platforms, boat piers, and visitor facilities. In contrast, reservoirs and ponds, though functionally valuable, exhibited lower aesthetic diversity owing to their artificial origin. The integration of recreational amenities with educational functions—such as wetland science centers and ecological restoration projects—further enhanced the cultural and educational value of riverine and lacustrine wetlands. This highlights the dual role of these wetlands as both ecological sanctuaries and venues for public engagement with nature.

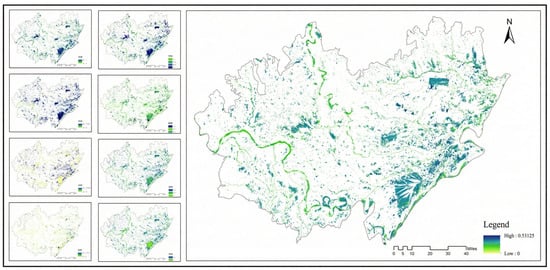

3.2.2. IESC Patterns and Spatial Differentiation Analysis

After normalization and weighted integration of the eight indicator variables, the comprehensive IESC of the Jianghan Lake Cluster was evaluated (Figure 4). The results revealed that overall IESC was relatively low along the margins of riverine and lacustrine wetlands. In contrast, reservoirs and ponds exhibited significantly higher service efficiency. Planar, embanked lakes, characteristic of the Jianghan Plain, displayed consistently low IESC owing to geomorphological constraints, intensive human disturbance, and inherent ecological fragility. These lakes, typically located in the central lowlands of the plain, are shallow and morphologically uniform, with flat lakebeds and thick silt deposits. The straight and monotonous shorelines, with minimal embayment development, result in a low shoreline development index. This morphological simplicity severely limits hydrodynamic mixing and water exchange, creating a homogeneous physicochemical environment within the lake. Additionally, the shallow, low-energy conditions of these lakes make them highly susceptible to external disturbances, such as sediment accumulation, biogenic deposition, and anthropogenic interference. These disturbances further weaken the ecological service functions of the lakes.

Figure 4.

Spatial distribution of ecosystem service efficacy in the Jianghan Lake Cluster.

Historically, the flat terrain and accessibility of these planar lakes have made them focal areas for land reclamation, aquaculture, and agricultural expansion, thereby enclosing them within embanked polder systems. Intensive human activities have degraded peripheral wetlands and reduced natural vegetation, thereby diminishing the buffering capacity and ecological resilience of the lakes. For example, aquaculture operations within embanked areas and industrial wastewater discharge have significantly increased nutrient loads, leading to eutrophication and biodiversity decline. Moreover, concentrated human activities along lake margins have intensified spatial disparities in ecosystem service performance, forming characteristic “low-efficiency zones” around the lakes.

Ecologically, embanked planar lakes are fragile systems with limited self-purification capacity. The shallow, enclosed morphology of these lakes hinders pollutant dilution and degradation. Additionally, the homogeneous environment limits habitat diversity and reduces aquatic biodiversity. Consequently, the ecosystem functions of planar lakes are mainly confined to provisioning services, such as water supply and agricultural support. In contrast, regulating and cultural services remain underdeveloped. These findings indicate that the spatial heterogeneity of IESC in the Jianghan Lake Cluster is closely related to wetland morphology and anthropogenic pressures. This highlights the need for differentiated management and ecological restoration strategies tailored to lake typology and vulnerability.

3.3. Ecosystem Restoration and Service Efficiency Optimization in the Jianghan Lake Cluster

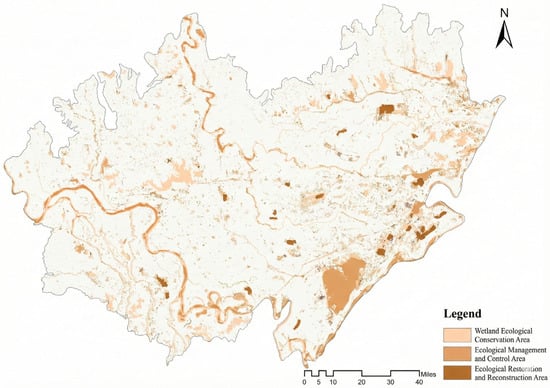

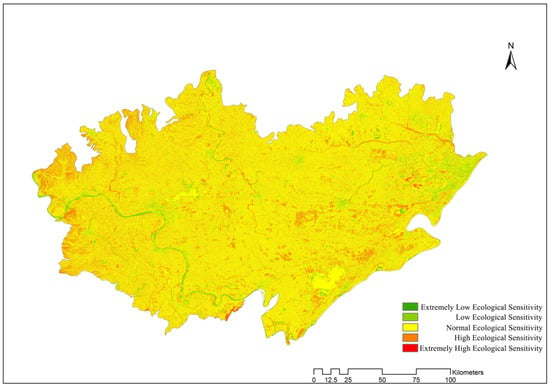

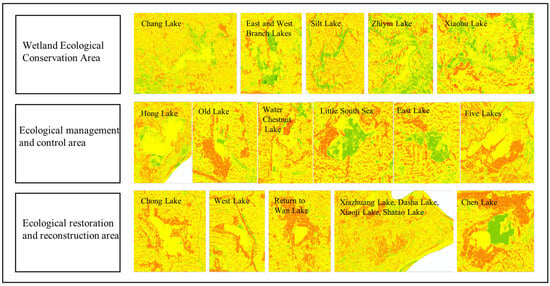

3.3.1. Ecological Functional Zoning

The planar, embanked lakes of the Jianghan Lake Cluster exhibit relatively low IESC owing to their simple morphology, intensive anthropogenic disturbances, and inherent ecological fragility. However, these characteristics make the lakes high-priority targets for ecological restoration and functional optimization. Targeted restoration measures can enhance the ecological functionality of these lakes, thereby promoting sustainable resource use and the development of self-sustaining ecological cycles. Through the integration of wetland morphology with IESC, the Jianghan Lake Cluster was classified into functional zones based on differences in ecosystem service value, morphological features, and ecological attributes. Three main functional zones were delineated. First, Ecological Conservation Zones prioritize wetland protection and strict control of human disturbance. Second, Ecological Regulation and Management zones focus on ecological governance, water-quality regulation, and buffer area construction. Finally, Ecological Restoration and Reconstruction Zones prioritize large-scale rehabilitation and habitat reconstruction. These zones were assigned progressively higher restoration priorities, forming a hierarchical framework for regional wetland management and efficiency optimization (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Functional zoning of WES.

3.3.2. Optimization Strategies for IESC

The implementation of the optimization strategies can significantly enhance the IESC of the Jianghan Lake Cluster. This enhancement promotes sustainable regional resource use and supports the development of a resilient, self-regulating ecological system. This approach integrates ecological restoration, management, and conservation measures. These measures further strengthen the structure–function coupling of wetland ecosystems and promote long-term improvements in IESC. The overall strategy for optimizing IESC in the Jianghan Lake Cluster is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Zonation and Optimization Strategies for IESC in the Jianghan Lake Cluster.

(1) Wetland Ecological Conservation Zones

Wetland ecological conservation zones are areas within the Jianghan Lake Cluster characterized by high IESC and relatively intact ecological functions. Optimization strategies for these zones should prioritize preserving existing ecosystem functions and maintaining ecological stability and landscape-scale integrity. Specific strategies include the following:

Restricting development activities: Developments within designated conservation areas, such as land reclamation and lake infilling, should be strictly prohibited to preserve lake morphology and reduce anthropogenic disturbances to aquatic and riparian ecosystems.

Enhancing wetland protection and restoration: Restoration measures, such as re-vegetation and the conversion of farmland back to wetlands, should be implemented to strengthen the structural integrity and functional stability of the wetland ecosystem.

Establishing an ecological monitoring network: A long-term ecological monitoring system should be developed to continuously track key ecological indicators, including water quality, vegetation cover, and biodiversity. These results provide scientific support for conservation management and informed decision-making.

Implementing ecological water replenishment: Rational water-resource allocation should be used to implement ecological replenishment measures that stabilize lake water levels, improve hydrological conditions, and sustain ecosystem service performance.

(2) Ecological Regulation and Management Zones

The ecological regulation and management zones include areas with moderate IESC and considerable potential for ecological enhancement. Optimization strategies in these zones should focus on maintaining and improving ecological functions through adaptive management measures. The main strategies are as follows:

Implementing ecological water allocation and replenishment: Water resources should be scientifically managed to maintain stable hydrological regimes, improve lake water quality, and promote overall ecosystem health.

Strengthening vegetation restoration and ecological rehabilitation: For degraded wetlands and exposed areas, vegetation restoration projects should be implemented using locally adapted species to enhance ecological resilience and hydrological regulation capacity.

Optimizing land-use structure: Land-use planning should aim to reduce agricultural non-point source pollution, mitigate nutrient runoff into wetlands, and promote a balance between ecological conservation and economic development.

Constructing ecological buffer zones: Establishing buffer strips between human activity areas and wetlands can effectively mitigate anthropogenic impacts, enhance ecological connectivity, and improve overall ecosystem stability.

(3) Ecological Restoration and Reconstruction Zones

The ecological restoration and reconstruction zones correspond to areas with low IESC and fragile ecological functions. Optimization strategies in these zones should focus on ecological restoration and remediation to rehabilitate lake ecosystem functions and enhance regional service efficiency. Specific strategies include the following:

Implementing pollution control and ecological remediation: Targeted measures should address water and sediment contamination, such as sediment dredging and pollution-source reduction, to improve water quality and facilitate ecological recovery.

Reinforcing wetland restoration and vegetation reconstruction: Wetland restoration projects should use native or regionally adapted species to rebuild vegetation structure, enhance ecological functionality, and improve habitat stability.

Applying ecological water replenishment and hydrological regulation: Water resources should be scientifically managed to stabilize lake levels, improve aquatic environments, and restore ecological balance.

Strengthening ecological monitoring and evaluation: A long-term monitoring and evaluation system should be developed to regularly assess water quality, vegetation cover, and biodiversity. This system ensures that restoration outcomes are scientifically evaluated and supports adaptive management.

3.3.3. Sensitivity Analysis

The results of the ecological sensitivity analysis are presented in Figure 7 and Figure 8. Areas of high ecological sensitivity (shown in red) are mainly concentrated around lakeside settlements, along major transportation corridors, and in regions of intensive agricultural reclamation. These areas exhibit significant habitat fragmentation and are highly exposed to anthropogenic disturbances. In contrast, regions of low ecological sensitivity (highlighted in green) are mainly located within the core water bodies of large lakes, contiguous forest patches, and remote lake-centered zones far from urbanized areas. These regions largely maintain their ecosystem integrity.

Figure 7.

Ecological sensitivity analysis results for the study area.

Figure 8.

Ecological sensitivity analysis results under optimized ecosystem service enhancement strategies.

For the representative lakes within the Wetland Ecological Conservation Zone, the average proportion of highly sensitive areas is relatively low. This indicates that ecosystems in this zone are generally stable, with minimal human disturbance and strong ecological integrity. From a “low-vulnerability” perspective, these findings support the designation of this zone as a priority conservation core area.

In the Ecological Management and Regulation Zone, representative lakes exhibit a significantly higher average proportion of highly sensitive areas compared with the conservation zone. This reflects a moderate level of anthropogenic disturbance, with ecosystems maintained in a state of dynamic balance. Although the ecosystems face degradation risks, they retain significant potential for improvement through appropriate management interventions. These results support the implementation of an optimization strategy focused on “maintenance and enhancement” within this zone.

In the Ecological Restoration and Reconstruction Zone, the representative lakes exhibit the highest average proportion of highly sensitive areas, which significantly exceeds those of the other two zones. This indicates that these lake ecosystems are the most fragile owing to severe habitat fragmentation and intensive human pressures. The findings highlight the necessity and urgency of prioritizing this zone for ecological restoration efforts.

The spatial heterogeneity of ecological sensitivity provides refined guidance for tailoring restoration measures within each zone. In the Restoration and Reconstruction Zone, highly sensitive areas (such as lakeshore belts adjacent to village settlements) should be prioritized for wetland reconversion, the establishment of ecological buffer strips, and habitat rehabilitation. In contrast, the Management and Regulation Zone should focus on industrial upgrading and pollution control in areas of moderate to high sensitivity.

4. Discussion

4.1. Spatial Patterns and Driving Mechanisms of Integrated Ecosystem Services

This study systematically examined the spatial distribution patterns and driving mechanisms of IESC in the Jianghan Lake Cluster wetlands using a multidimensional evaluation framework. Eight core ecosystem service indicators, including habitat quality, carbon storage, and water purification, were quantitatively assessed through an integrated InVEST modeling approach. The results revealed pronounced spatial heterogeneity in IESC. Riverine and lacustrine wetlands with strong natural attributes exhibited higher biodiversity value but lower regulating services than reservoirs and ponds, which are more intensively managed.

Building on the conventional ecosystem service evaluation framework, this study incorporated lake-morphological parameters to develop an innovative morphology–efficiency coupling model. The relationships between the shoreline development index and IESC were quantitatively assessed through weighted regression and spatial overlay analyses. The results reveal that the low-efficiency patterns in planar, embanked lakes are driven by enclosed hydrological conditions and limited water exchange. This morphology-driven efficiency decline highlights the structural constraints shaping wetland ecosystem performance and provides a basis for targeted restoration and ecological management in the Jianghan Lake Cluster. These spatial heterogeneity patterns are consistent with previous InVEST-based assessments in Dong ting Lake and other Yangtze-connected lake regions [37]. Similarly, more natural lake systems exhibit higher ecosystem service capacity and declines associated with reclamation/urbanization.

4.2. Model Applicability and Parameterization Assessment

The InVEST model provides an integrated framework for the spatially explicit assessment of multiple ecosystem services. The Carbon Storage module estimates steady-state carbon levels across four carbon-pool components, making it suitable for cross-scenario comparisons. The Habitat Quality module assesses habitat degradation through a “threat–sensitivity–distance/decay” mechanism, enabling the identification of disturbance hotspots. Additionally, the NDR and SDR modules simulate nutrient and sediment transport dynamics based on terrain connectivity, thereby effectively capturing spatial propagation effects across landscapes.

The InVEST model is highly sensitive to several key parameters. In the Carbon Storage module, carbon-pool density values determine the magnitude and spatial variation of total carbon storage. In the Habitat Quality module, the weights and maximum impact distances of threat factors strongly influence habitat degradation intensity. For the NDR module, nutrient export coefficients, maximum retention efficiency, and critical distances govern nutrient export and retention dynamics. Similarly, the SDR module is highly sensitive to the C (cover-management) and P (conservation-practice) factors, slope-length and steepness (LS) parameters, and the overall connectivity index.

In this study, region-specific parameters were first compiled from existing datasets and literature and then adjusted to reflect the biophysical and anthropogenic characteristics of the Jianghan Lake Cluster. This hybrid parameterization approach ensured both regional adaptability and cross-scenario comparability, thereby enhancing the robustness and transferability of the ecosystem service assessment results.

4.3. Management Implications and Zonal Optimization Strategies

The integration of the composite IESC spatial distribution with lake morphology enables the delineation of three functional zones. Each zone requires differentiated management strategies. In the Ecological Conservation Zone, priority should be given to limiting urban development, enhancing wetland protection and restoration, establishing long-term ecological monitoring networks, and implementing ecological water replenishment to maintain high-value services. The Ecological Regulation and Management Zone should focus on ecological water allocation, vegetation rehabilitation, optimized land-use planning, and non-point source pollution control. Additionally, the construction of ecological buffer zones and intelligent monitoring systems should be implemented to enhance ecosystem service provision and system resilience. The Ecological Restoration and Reconstruction Zone requires both engineering and institutional restoration interventions, such as sediment dredging, pollution-source remediation, lake reconnection, and habitat reconstruction, to restore fragmented and low-efficiency service areas.

The proposed three-tier optimization framework represents a shift from passive protection to proactive restoration. Quantitative assessments indicate that ecological water replenishment and vegetation restoration in conservation zones could increase regional carbon-sequestration capacity by 15–20%. The construction of ecological buffer zones and intelligent monitoring systems in regulation zones could intercept over 35% of non-point source pollutants. Embankment removal and habitat reconstruction in restoration zones could enhance the biodiversity index by ~30%. The study highlights the need to integrate restoration planning with agricultural transformation in polder areas. Specifically, conventional paddy fields should be converted into wetland–farmland composite systems to maintain food security and reduce nitrogen and phosphorus loads by over 40%.

Through the integration of spatial planning with adaptive governance, these strategies provide a practical pathway to rebuild ecological security, optimize service functions, and enhance value transformation in the Jianghan Lake Cluster.

5. Conclusions

This study presents an operational framework and spatial basis for the differentiated restoration and refined management of lacustrine wetlands. The proposed approach supports the identification of conservation-priority areas, optimization of buffer-zone layouts, and integrated evaluation of engineering and ecological measures. These findings provide scientific guidance for enhancing regional ecological security and sustaining ecosystem service performance. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) A multidimensional ecosystem service assessment system for lacustrine wetlands was established through the integration of InVEST modules for carbon storage, habitat quality, water purification, and soil retention. This system incorporates indicators of regulating and cultural services. This integrated framework provides a quantitative and reproducible method to support scenario comparisons and spatially informed decision-making.

(2) The ecosystem services of the Jianghan Lake Cluster exhibited pronounced spatial heterogeneity. Habitat quality was generally higher in lakes and reservoirs. However, low-quality areas were concentrated along river channels, ponds, and the shorelines of embanked lakes. Tidal flats, marshes, and lakes demonstrated strong carbon-storage capacity. In contrast, rivers exhibited the lowest carbon-storage capacity. Reservoirs and ponds exhibited superior water-purification efficiency. Soil-retention capacity displayed a distinct east–west gradient, shaped by sediment deposition along certain rivers and canals.

(3) The study coupled composite ecosystem efficiency with lake morphology to identify three functional zones: conservation, regulation, and restoration. Each zone has distinct management priorities. Conservation zones focus on restricting urban development, protecting and restoring wetlands, implementing long-term monitoring, and ensuring ecological water replenishment. Regulation zones prioritize water allocation, vegetation rehabilitation, land-use optimization, and buffer-zone construction. Restoration zones prioritize sediment dredging, pollution-source control, embankment removal, and habitat reconstruction to restore ecological connectivity and ecosystem service functionality. This zonal framework provides a spatially explicit and operationally feasible approach for the ecological restoration and management of the Jianghan Lake Cluster.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.M. and Y.W.; Methodology: Y.M. and Y.W.; Formal analysis: Y.M., Y.W., L.J., W.Z. and D.W.; Investigation: Y.W. and L.J.; Data curation: Y.W. and L.J.; Writing—original draft: Y.M., Y.W. and W.Z.; Writing—review and editing: D.W.; Visualization: Y.W. and L.J.; Supervision: D.W.; Project administration: D.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was Supported by Beijing Natural Science Foundation under Grant No. 8244055. The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by the foundation, which was crucial for completing this work.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. The Land Use and Cover Change (CNLUCC) (available at: https://igsnrr.cas.cn/) and ASTER GDEM data can be accessed via the Geospatial Data Cloud Platform (available at: https://www.gscloud.cn/). Specific local survey data regarding biodiversity are restricted due to privacy and conservation policies and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Costanza, R.; de Groot, R.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M.; Hannon, B.; Limburg, K.; Naeem, S.; Paruelo, J.; Raskin, R.; Sutton, P. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Ecol. Econ. 1998, 25, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhard, B.; Kroll, F.; Nedkov, S.; Müller, F. Mapping ecosystem service supply, demand and budgets. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 21, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, E.; Mendoza, G.; Regetz, J.; Polasky, S.; Tallis, H.; Cameron, D.; Chan, K.M.; Daily, G.C.; Goldstein, J.; Kareiva, P.M. Modeling multiple ecosystem services, biodiversity conservation, commodity production, and tradeoffs at landscape scales. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2009, 7, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seppelt, R.; Dormann, C.F.; Eppink, F.V.; Lautenbach, S.; Schmidt, S. A quantitative review of ecosystem service studies: Approaches, shortcomings and the road ahead. J. Appl. Ecol. 2011, 48, 630–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, D.; Schwarz, N.; Strohbach, M.; Kroll, F.; Seppelt, R. Synergies, trade-offs, and losses of ecosystem services in urban regions: An integrated multiscale framework applied to the Leipzig-Halle Region, Germany. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geijzendorffer, I.R.; Martín-López, B.; Roche, P.K. Improving the identification of mismatches in ecosystem services assessments. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 52, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, A.; Avishek, K. Assessing Tradeoffs and Synergies between Land Use Land Cover Change and Ecosystem Services in River Ecosystem Using InVEST Model. Res. Sq. 2024. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, Z.; Zubair, M.; Zha, Y.; Mehmood, M.S.; Rehman, A.; Fahd, S.; Nadeem, A.A. Predictive modeling of regional carbon storage dynamics in response to land use/land cover changes: An InVEST-based analysis. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 82, 102701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wu, J. Spatial and temporal driving mechanisms of ecosystem service trade-off/synergy in national key urban agglomerations. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, D.E.; Gosnell, H. Integrating multiple perspectives on payments for ecosystem services through a social–ecological systems framework. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 116, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biao, Z.; Yunting, S.; Shuang, W. A review on the driving mechanisms of ecosystem services change. J. Resour. Ecol. 2022, 13, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yinglan, A.; Wang, J.; Zeng, Q.; Wu, S.; Yan, L.; Liu, H.; Yang, Z.; Yang, Q.; Wang, L.; Hu, P. Optimization of wetland water replenishment process based on the response of waterbirds. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 156, 111142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Yang, C.; Guluzada, E.; Safarova, N.; Zhang, X. Methods and Challenges for Coastal Wetlands Restoration in the Jianghan Plain: Integrating Remote Sensing, Financial Indicators and Ecological Indicators. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 177, 113799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sheng, Y.; Tong, T.S.D. Monitoring decadal lake dynamics across the Yangtze Basin downstream of Three Gorges Dam. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 152, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahmasebi, M.; Bruck, J.; Sadaf, A. Modeling Future Land Cover and Predicting Carbon Storage and Sequestration in Coastal Areas. In AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts; AGU: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; p. GC21K-0019. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R.; Nehren, U.; Rahman, S.A.; Meyer, M.; Rimal, B.; Aria Seta, G.; Baral, H. Modeling land use and land cover changes and their effects on biodiversity in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Land 2018, 7, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Guan, Q.; Lin, J.; Yang, L.; Luo, H.; Ma, Y.; Tian, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, N. The response and simulation of ecosystem services value to land use/land cover in an oasis, Northwest China. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 118, 106711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, R.; Tallis, H.; Ricketts, T.; Guerry, A.D.; Wood, S.A.; Chapin-Kramer, R.; Nelson, E.; Ennaanay, D.; Wolny, S.; Olwero, N.; et al. InVEST 3.2.0 User’s Guide; The Natural Capital Project; The Nature Conservancy, and World Wildlife Fund: Arlington, VA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Cheng, W. Effects of land use/cover on regional habitat quality under different geomorphic types based on InVEST model. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Yu, W.; Meng, P.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J. Impacts of land use change on landscape pattern and habitat quality. Land Degrad. Dev. 2022, 33, 2870–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, J. Identifying priority areas for biodiversity conservation based on Marxan and InVEST model. Landsc. Ecol. 2022, 37, 3043–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, H.; Song, Y. A review on principle and application of the InVEST model. Ecol. Sci. 2015, 34, 204–208. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Geng, J.; Bao, J.; Lin, W.; Wu, Z.; Fan, S. Spatial and temporal variations in ecosystem service functions in Anxi county. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assessment, M.E. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Our Human Planet-Summary for Decision-Makers; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Hu, S.; Frazier, A.E.; Xie, W.; Zang, Y. Cultivated Ecosystem Services in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Land Degrad. Dev. 2025, 36, 3827–3843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yang, G.; Tan, Y.; Liu, J.; Hu, H. Ecosystem services trade-offs in China’s Yangtze River Economic Belt. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 634, 1601–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlinszky, A.; Heilmeier, H.; Balzter, H.; Czúcz, B.; Pfeifer, N. Remote sensing and GIS for habitat quality monitoring: New approaches and future research. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 7987–7994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moilanen, A.; Hanski, I. Metapopulation dynamics: Effects of habitat quality and landscape structure. Ecology 1998, 79, 2503–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Xia, Z.; Wei, X.; Wei, X.; Liu, L.; Yuan, C. Response of wetland ecosystem services to landscape patterns. Wetl. Sci. 2024, 22, 139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Kong, L.; Xiao, Y.; Zheng, H. Landscape Patterns and Ecosystem Water Purification in the Yangtze River Basin. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2019, 39, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, Y.; Fan, M.; Zhou, L.; Yu, X. Ecosystem services in Ganzi Prefecture. Environ. Sci. 2025, 46, 3070–3084. [Google Scholar]

- Gashaw, T.; Bantider, A.; Zeleke, G.; Alamirew, T.; Jemberu, W.; Worqlul, A.W.; Dile, Y.T.; Bewket, W.; Meshesha, D.T.; Adem, A.A.; et al. Evaluating InVEST model for estimating soil loss and sediment export in data scarce regions of the Abbay (Upper Blue Nile) Basin: Implications for land managers. Environ. Chall. 2021, 5, 100381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Ma, T.; Li, X.; Cui, B. Ecosystem Service Simulation of Coastal Wetlands. Wetl. Sci. 2015, 13, 667–674. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Liu, G. Energy-Based Evaluation of Wetland Ecosystem Service Values. Acta Sci. Circumst. 2018, 38, 4527–4538. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, H.; Hu, Y.; Huang, Y. Coupling and Coordination between Ecosystem Services and Well-being. J. Zhejiang AF Univ. 2025, 42, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Umer, M. Ecotourism Suitability in Taihangshan National Park. Sustainability 2025, 17, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Sun, R.; Kazemi, E.; Pang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, K. Evaluation of Ecosystem Services in Dongting Lake Wetland. Water 2019, 11, 2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).