Abstract

The urban–rural relationships in China are experiencing a dual structure period, balancing an urban–rural development period and coordinated urban–rural development period, and urban–rural integrated development has become the current strategy. Urban–rural integrated development has become an important measure to address the unbalanced development between urban and rural areas. Despite proactive explorations by governments at various levels to promote integrated urban–rural development, the anticipated outcomes remain difficult to achieve due to multiple constraints, such as inefficient flow of production factors and unequal provision of basic public services between urban and rural areas. There is an urgent need to re-examine how to advance deeper urban–rural integration from the perspective of collaborative governance. Taking the Yangtze River Delta region as a case study, this research reviews related policy documents, official texts, and development plans regarding urban–rural integrated development, social (urban–rural community) collaborative governance, and urban development at the central and regional levels in recent years. Meanwhile, this study interviews experts in the field of public administration and government officials, and visits the experimental area and demonstration area of integrated development in the Yangtze River Delta region. Through grounded theory method and multi-level coding, concepts, initial categories, main categories are clear, and six core categories in total are identified: policy planning capability, public participation, participation of non-governmental organization, openness of government information, supervision and evaluation, and implementation capacity. This bottom-up construction of the theoretical framework serves as an extension and enrichment of collaborative governance theory. Based on the six core elements identified through the research, the Yangtze River Delta region may implement targeted policy adjustments across these dimensions to enhance the effectiveness of collaborative governance, and it may provide referential insights for urban–rural development practices in other regions.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

The urban–rural relationship is the most basic economic and social relationship [1,2]. The urban–rural relationships in China experienced dual structure period, balancing urban–rural development period, coordinated urban–rural development period, and urban–rural integrated development has becoming the latest description [3,4]. Urban–rural integrated development represents the most mature and ideal stage in the evolution of urban–rural relationships [5,6]. Urban–rural integrated development, as an important feature and main goal in the second half of the new urbanization, has become a significant measure to address the unbalanced development between urban and rural areas [7]. Meanwhile, urban–rural integrated development has been gradually become research hotspot in the field of public administration [8,9,10]. In the global processes of urbanization and modernization, the contrast between rural decline and urban prosperity is evident—a phenomenon notably prevalent in developing countries, where rural decline has become a widespread reality [11]. From a holistic perspective, cities and villages form a system in which they hold equal status, differing only in the functions they undertake [12]. For a long time, dual urban–rural system in China, characterized by urban-biased development strategies, citizen-oriented distribution systems, and industry-oriented industrial structures, has led to obvious structural contradictions in urban–rural development [13]. These contradictions are embodied in the imbalanced urban–rural development, inadequate rural development, widening urban–rural disparities, and gradual decline of rural areas. These issues have become the concentrated manifestation of the contradiction between the ever-growing needs of the people for a better life and inadequate development, severely constraining the high-quality and sustainable development of both urban and rural areas in China. In the rapid process of urbanization, factors such as labor, capital, and land have formed a configuration pattern flowing from rural areas to cities, leading to the rapid development of cities [14,15]. Meanwhile, the output and spillover effects of cities on rural areas remain relatively limited. This predominantly unidirectional “rural-to-urban” flow pattern constitutes a primary driver of rural underdevelopment in China [16]. Empirical studies have indicated that prior to 2010, rural areas were in a state of passive development, largely relying on the driving force of cities to propel rural development. However, since 2010, the advancement of agricultural modernization and rural development has fostered greater dynamism in factor mobility between urban and rural areas, marking the beginning of an accelerated phase of urban–rural interaction [17,18]. Cities and villages form a community with a shared future, mutually promoting and supporting each other, in order to achieve a harmonious, enduring, and virtuous cycle of urban–rural co-prosperity and symbiosis [19]. Consequently, reshaping the urban–rural relationships and integrating urban–rural development constitute the fundamental approach and logic underpinning the implementation of Chinese rural revitalization strategy [20,21]. Against the backdrop of achieving high-quality development and advancing sustainable urban–rural development, integrating urban–rural development has demonstrated its significance and necessity in ameliorating the urban–rural relationship and alleviating the issues of inadequate and unbalanced regional development [22,23]. In China, the concept of “national governance” was formally introduced for the first time at the Third Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, which called for a shift from “traditional social management” to “modern social governance”, thereby advancing the modernization of the national governance system and governance capacity. This governance philosophy is conducive to addressing the issues of “fragmentation” and “atomization” in the process of government administration, thereby avoiding the “Tacitus Trap”, and achieving an efficient situation characterized by joint discussion, consensus, collaboration, sharing, and co-governance [24]. After witnessing instances of “governmental failure” and “market failure”, governance theory has gradually emerged as a prominent topic in the field of public administration. Under the influence of the New Public Management Movement, government functions have gradually shifted from “controller” to “steersman”. Government public administration has evolved from being a “governance-oriented administration” to a “service-oriented administration”, progressively abandoning the omnipotent model of government that encompasses all responsibilities. Instead, it encourages and incorporates the participation of diverse entities such as non-governmental organizations, businesses, and citizens in social governance [25]. Collaborative governance refers to an institutional arrangement in which governmental and non-governmental actors participate on an equal basis, guided by shared objectives, to jointly implement public administrative affairs. It has proven to be an effective policy tool in the field of public management. Effective governance, in this sense, involves the collaborative and shared administration of diverse stakeholders centered around common interests [26,27,28]. Ye & Liu recognizes that urban–rural collaborative governance has emerged as a significant issue of paramount importance for both current and future development [29]. Despite urban–rural integrated development being elevated to a national strategy and actively explored by governments at all levels, its anticipated outcomes remain elusive due to multiple challenges—including constrained flows of factors between urban and rural areas and unequal provision of basic public services. It is therefore imperative to reconsider how to advance urban–rural integrated development from the perspective of collaborative governance.

Based on the above arguments, this study aims to seek key elements and establish the collaborative governance impact mechanism for the urban–rural integrated development in the Yangtze River Delta region as its ultimate objective.

1.2. Study Area

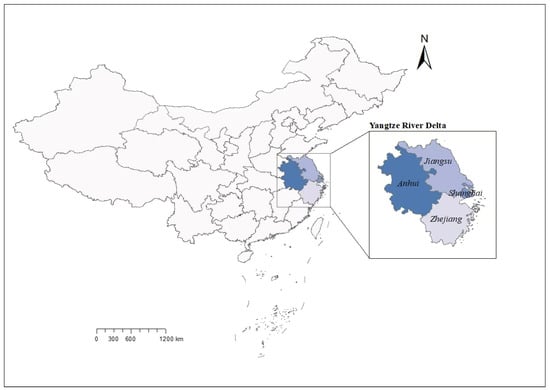

The Yangtze River Delta region, situated in the alluvial plain formed by the lower reaches of the Yangtze River before it empties into the Yellow and East China Seas, constitutes a strategically pivotal zone where the Belt and Road Initiative converges with the Yangtze River Economic Belt. This unique geographical positioning endows it with critical significance in China’s broader context of modernization and comprehensive opening-up policies. Located within the administrative framework of the People’s Republic of China, the Yangtze River Delta region comprises the entirety of four provincial-level divisions: Shanghai Municipality, Jiangsu Province, Zhejiang Province, and Anhui Province, as shown in Figure 1. The Yangtze River Delta region covers an area of 358,000 square kilometers, accounting for only 3.72% of the Chinese land area, nonetheless the GDP of this region accounts for about 25% of the China. As one of the most economically developed and most densely populated city-regions in China, the Yangtze River Delta region has played an important role in the process of new-type urbanization and rural revitalization, with high level and rate of urban–rural development [30,31]. However, there are still significant development gaps between urban and rural areas, also between different provinces [32,33]. Therefore, this study selects the Yangtze River Delta region as its research area. Its high urbanization rate, advanced socio-economic development, complex stakeholder relationships, and governance challenges collectively render it an exemplary testing ground for investigating urban–rural integrated development and collaborative governance practice. Meanwhile, examining the developmental experience of the Yangtze River Delta region can provide comprehensive institutional references for urban–rural integrated development. When conditions mature, these practices may be elevated to exemplary institutional arrangements and policy frameworks for regional or even nationwide urban–rural integrated development and collaborative governance practice.

Figure 1.

Position of the Yangtze River Delta region.

2. Research Method and Data Collection

2.1. Research Method

The qualitative research approach known as grounded theory, jointly developed by Strauss and Glaser, represents a unique methodology for constructing theory from existing data. It focuses on a particular proposition or phenomenon and involves the processes of collecting, analyzing, organizing, summarizing, and comparing empirical materials. Through the decomposition and conceptualization of these materials, the approach extracts concepts that reflect social phenomena. Subsequently, it reintegrates the materials in an innovative manner to establish a theory that approximates the real world, possesses strong explanatory power, and can unveil causal relationships [34,35]. The strength of grounded theory lies in its independence from pre-existing theories and hypotheses. Instead, it involves the synthesis and organization of existing data and social phenomena, transforming seemingly discrete and complex raw materials and social observations into generalized summaries. Through this process, dynamic processes and patterns of change are identified, enabling the ascent to a theoretical framework that can be comprehended and acknowledged by those within the scholars in the same field [36,37].

The adoption of grounded theory is justified by two considerations. On the one hand, among the scholars who have utilized this method to explore collaborative governance of urban–rural integrated development, many have focused solely on a single dimension, such as urban–rural integrated development itself, community collaborative governance. Consequently, there is a lack of comprehensive induction, generalization, and refinement of the underlying logic behind the practices of collaborative governance of urban–rural integrated development. On the other hand, the practical logic of collaborative governance of urban–rural integrated development entails abstracting the interactive relationships and dynamic patterns between governance subjects and contents through intricate governance processes. This aligns well with the objectives of grounded theory, which is grounded in data, involves interpretive processes, and aims to identify underlying regularities. Furthermore, it meets the requirements of grounded theory in addressing specific issues within unique and emerging domains. Following the New Public Management movement, scholarly research on collaborative governance has witnessed gradual growth both domestically and internationally. This study seeks to investigate the collaborative governance mechanisms operative in the process of urban–rural integrated development, thereby extending and enriching the existing corpus of theoretical work on collaborative governance. Grounded theory has been extensively applied in public management research, and has sorted out a variety of public management issues suitable for this methodology. In the field of public management, grounded theory holds significant theoretical and practical implications, both for constructing related theories and for achieving a more structured understanding of practice processes [38,39]. In result from differences in fundamental national conditions, traditional culture, and the progress of urban–rural development, certain social issues in China cannot be addressed by drawing lessons from foreign literature or experiences. The grounded theory approach is precisely applicable for uncovering practical problems encountered in the process of collaborative governance in urban–rural integrated development within the specific context of China. Furthermore, the grounded theory approach facilitates a deeper focus on the process, the search for solutions, and the summation of experiences. In the context of current urban–rural integrated development, the collaborative governance practices across various regions in the Yangtze River Delta region have furnished a vast array of accessible primary materials for grounded theory research.

Therefore, this study employs a grounded theory methodology, collecting primary data from multiple sources and identifying core categories through multi-stage coding procedures, in which the impact mechanism of collaborative governance in promoting urban–rural integrated development within the Yangtze River Delta region will be explored.

2.2. Data Collection

In the grounded theory approach, the materials required for the coding process can originate from primary sources such as questionnaires and interviews, as well as secondary sources including policy documents and newspapers. Written discourse, while reflecting a “structured and regular whole world”, simultaneously constructs a “described world” [40]. Therefore, policy documents constitute an important source of data for grounded theory research. Through the interpretation and analysis of policy documents, one can also piece together clues to an underlying world [41]. Policy documents represent specific forms of discourse that embodies the aspirational goals, guiding principles, defined tasks to be accomplished, and general steps for implementation, articulated by state and political organizations within particular historical periods. They possess both representativeness and authority [42,43,44]. This study contends that policy documents pertaining to urban–rural integrated development and collaborative governance in the Yangtze River Delta region, which possess both theoretical and practical significance, serving as the standardized official discourse system, embody the cognition of public power organizations towards urban–rural integrated development and process of collaborative governance. Consequently, this study intends to utilize relevant policy documents issued by Yangtze River Delta region as one of the pivotal materials for grounded theory approach, complemented by semi-structured interviews and field observation records. To ensure a robust and diverse array of materials supporting the application of the grounded theory approach and to allow for mutual corroboration among high-quality data, thereby guaranteeing the reliability and validity of the research, this study collected relevant materials from the following three aspects.

- Policy Texts. This study analyzed over one hundred textual materials, including policy documents, official texts, and development plans concerning urban–rural integrated development, rural revitalization, and collaborative governance of urban–rural communities issued by the central government and the Yangtze River Delta region from 2023 to 2025. Here, the terms policy documents and official texts primarily refer to official, macro-level plans, whereas development plans denote micro-level implementation plans. The year, type, source and quantity of the texts are presented in Table 1. These materials, totaling more than forty thousand words, were sourced from newspapers, websites of party and government departments, serving as the primary source of data for the grounded theory approach employed in this study.

Table 1. Text details.

Table 1. Text details. - Semi-structured Interviews. Between July 2024 and July 2025, this study conducted over a dozen depth interviews based on a theoretical sampling strategy, targeting professors, associate professors, doctoral candidates in the field of public administration from universities, as well as government officials in the field of urban–rural development. This group possesses profound professional experience and insights into collaborative governance, urban–rural development, and grassroots governance. Their interview data are of significant importance for theoretical construction and development. Interviewing was terminated when additional data no longer contributed to the development of new theoretical categories or dimensions. The primary focus of these interviews encompassed integrated development in the Yangtze River Delta region, urban–rural integrated development, and collaborative governance practices within urban–rural communities. Each interview lasted approximately 90 to 120 min. To ensure the authenticity of the interview contents and the psychological comfort of the interviewees, this study refrained from audio recording during the interviews. However, the information provided by the interviewees and the contents of the interviews were meticulously sorted and reviewed to guarantee the completeness of the interview materials. These materials served as valuable supplements to the data required for the grounded theory approach.

- Field Observation. This study conducted visits to multiple cities in the Yangtze River Delta region, engaging in on-site observations and documentation of collaborative governance practices. These observations served as a valuable supplement to the materials required for the grounded theory approach.

3. Coding Process

3.1. Opening Coding

The analytical steps of the grounded theory approach primarily encompass open coding, axial coding, and selective coding. Open coding is the process of coding the primary sources word by word, sentence by sentence, paragraph by paragraph, setting the corresponding labels and entering them, and then obtaining the initial concepts and the conceptual categories from them [45]. In the process of conceptualization, it was observed that there existed a proximity in the content described across various policy documents and interview materials. Concepts with similar content can be grouped under a more superior concept, which in the grounded theory methodology is also termed as a category. The coding process was iterative and involved a structured consensus-building approach. When encountering controversies, extensive discussions were conducted until the final coding results were unanimously agreed upon, for minimizing the personal bias of the researcher and ensuring the objectivity of the coding outcomes [46]. In addition, regular peer debriefing and expert consultation sessions were conducted to engage in critical discussions regarding the coding framework and emerging theoretical constructs. The insights derived from these deliberations were systematically incorporated to revise and refine the analytical framework. Ultimately, the triangulation of three distinct data sources ensured theoretical consistency, thereby significantly enhancing the reliability of the study.

Following this operation logic, a total of 134 initial concepts and 35 initial categories were extracted through the open coding process described above, as shown as in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of opening coding.

3.2. Axial Coding

After completing the open coding process, this study proceeds to explore the connections among various categories, analyze potential causal relationships, and further identify the logical relationships among the 35 initial categories, which are then reclassified. Following thorough adequately discussions, interviews and consultations, the initial categories were ultimately abstracted and refined into 13 major categories, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of axial coding.

3.3. Selective Coding

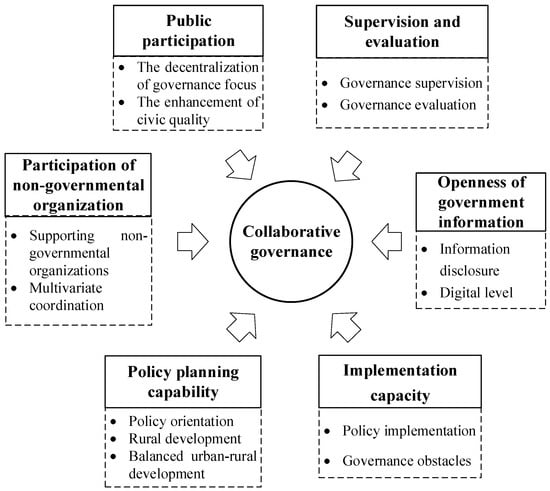

Selective coding is the systematic analysis of all the discovered conceptual categories and selecting a ‘core category’ with relevance and generality to coordinate other categories, thus forming a generalized formal theory [47,48]. After selective coding, six core categories are found, such as policy planning capability, public participation, participation of non-governmental organization, openness of government information, supervision and evaluation, and implementation capacity, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Theoretical framework.

3.4. Theoretical Saturation Test

It indicates that the existing theory has reached a state of saturation when newly collected data fails to provide additional contributions or impacts on the theoretical construction in this study, rendering further sampling and coding unnecessary [49,50]. In this research, the same three-step coding analysis was conducted on 20 pre-reserved policy documents, 4 interview transcripts, and 2 field observation records. All retained textual materials were independently coded by the research team until full consensus was achieved through iterative deliberation. The results revealed no emergence of new categories or relational influences, confirming the saturation level of the theoretical framework.

4. Research Results

4.1. Policy Planning Capability

China has entered a new phase characterized by urban–rural integrated development. The entrenched urban–rural dual structure, continues to serve as one of the major institutional obstacles impeding this developmental progression. In response to this challenge, successive rounds of policy reforms targeting urban–rural relations have been systematically enacted since the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China. “Urban–rural China” serves as a pivotal paradigm for comprehending the structural transformation of contemporary China. Any public policy that unilaterally emphasizes either rural construction or urban development would impede the nation’s progress toward achieving its grand transition [51,52]. A proper understanding of urban–rural relations is a historical process. It requires a correct assessment of the value orientation of urban–rural policies, the obstacles in policy implementation, and the need for coordinated policy reforms. Only by adhering to a people-centered approach can policies be effectively implemented and an integrated policy system be established to promote balanced urban–rural development [53].

From a governance perspective, achieving the new-era objectives of comprehensively urban–rural integrated development and rural revitalization necessitates state-led macro-level planning and guidance. Public policies must serve as institutional safeguards to facilitate synergistic development between urban and rural areas [54]. Under the urban–rural dualistic system, the strategy of prioritizing urban development was historically implemented, leading to a massive influx of labor, technology, capital, and other production factors into cities. This resulted in a range of socioeconomic disparities, including imbalanced regional development, unequal allocation of public resources, disparities in basic public services, and significant gaps in living standards between urban and rural residents [55,56]. During the phase of coordinated urban–rural development, while rural development issues have received greater policy attention compared to previous periods, the entrenched urban-dominant policy paradigm persists. Although increasing emphasis has been placed on the spillover and catalytic effects of urban centers on their peripheral rural regions, the latent potential of rural development remains substantially underexploited. The policy interventions and resource allocation mechanisms continue to demonstrate inadequate support for comprehensive rural revitalization [10]. In the new phase of urban–rural integrated development, the state must institutionally advance the equalization of basic public services through top-level policy design, rationally rebalance the spatial allocation of public resources, strategically prioritize rural infrastructure development, and extend critical urban infrastructure to suburban and rural areas [22,57]. Meanwhile, the complementary allocation of medical and educational resources between urban and rural areas should be enhanced, with particular emphasis on cultivating healthcare professionals and teaching staff in rural regions while prioritizing the development of rural education. Concurrently, policies should facilitate the absorption of surplus rural labor through employment opportunities to stimulate rural development, eliminate institutional barriers to urban migration for rural populations, incentivize urban professionals to relocate to rural areas and encourage the rural elites to participate in rural revitalization initiatives. It is essential to support and encourage farmers in entrepreneurship, broaden income-generating channels, and provide professional guidance, financial services, and e-commerce assistance for rural entrepreneurship. These measures aim to help smallholder farmers reduce costs and increase income, thereby achieving poverty alleviation and targeted poverty reduction. Public policies should leverage rural development potential can transform the weaknesses of rural areas into “opportunity spaces”, which involves cultivating distinctive and competitive rural industries, developing specialized branded products to establish brand effects, and focusing on peri-urban areas to construct characteristic towns. These towns can then serve as growth poles, radiating economic spillover effects to surrounding villages and ultimately forming a model development zone [58]. To achieve more efficient factor mobility, it is imperative to shift from the traditional unidirectional “rural → urban” flow pattern toward a more balanced and dynamic interaction between urban and rural areas. This entails facilitating freer population movement, strengthening capital flows, revitalizing underutilized rural land resources, and integrating urban and rural land markets [59].

4.2. Public Participation

It should be clarified that the term “public participation” in this study broadly refers to the engagement of residents and citizens as principal actors in collaborative governance. In contemporary society, the implementation of national public will heavily rely on bureaucratically structured government systems. Direct interface between such systems and the general public may potentially lead to institutionalized conflicts between authorities and civilians. Consequently, in the practice of collaborative governance, the establishment of an institutional platform enabling public stakeholders to articulate interest claims, seek policy consultation, or engage in decision-making processes would constitute a vital form of bottom-up political participation within the governance framework [8]. Public participation constitutes both a fundamental cornerstone and a pivotal driving force for collaborative governance in China’s social governance framework, while also serving as a dynamic manifestation of the Mass Line principle upheld by the Communist Party of China. Against the backdrop of advancing the modernization of national governance capacity, the principal-agent status of the public within the social governance system warrants further institutionalization and recognition [26,60,61]. The focus of social governance should shift downward to the grassroots level, with comprehensive understanding of the practical needs of urban and rural community residents, incorporation of frontline community workers’ perspectives, and institutionalized resident deliberation in major public decision-making processes concerning urban–rural communities. The coding process of grounded theory revealed that a significant proportion of residents demonstrate weak community identity and sense of belonging, exhibiting tenuous connections with their communities- a phenomenon consistent with the theoretical construct of “vanishing communities”. Consequently, expanding the channels and mechanisms for public opinion articulation and participatory engagement assumes critical significance. Exemplary modalities include governmental hotlines, and mayoral correspondence systems, which collectively facilitate the effective voicing of citizen demands. Efforts should be made to strengthen civic engagement awareness, bolster community identity and belonging among residents in both urban and rural areas, and reinforce their sense of social responsibility as active participants in governance processes. In the coding process, this study observed the frequent emergence of key terms such as “social learning” and “shared vision”. Social learning refers to the process by which the public acquires relevant social norms, skills, and knowledge to fulfill societal needs while enhancing their willingness to participate in social affairs [62]. Rapid social development and harmonious social relationships constitute the shared vision of the entire public.

In traditional Chinese society, particularly in rural governance structures, there has been a predominant emphasis on informal social relations, where the renqing (interpersonal reciprocity) principle served as a fundamental norm governing social interactions and the exchange of resources [63]. The new rural elites constituted a distinct social stratum closely associated with the bureaucratic establishment, wielding considerable informal authority within traditional power structures [64]. From the perspective of rural governance mechanisms, these individuals were institutionally recognized as influential actors whose efficacy in community governance derived principally from their ability to leverage personal prestige and maintain broad-based villager endorsement. Based on the empirical reality that urban areas offer more employment opportunities and better public services, the migration of talent from rural to urban areas appears to be a “taken-for-granted” phenomenon, whereas the reverse flow from urban to rural areas constitutes a form of “counter-current mobility”. The new rural elites, who possess both the subjective willingness and objective advantages to promote rural development, must serve as crucial “bridges” facilitating urban–rural integrated development, with their role becoming increasingly prominent in the collaborative governance practices of such integration. First, the broader context of urban–rural integrated development and the Rural Revitalization Strategy has created favorable opportunities and institutional environments for elite individuals to return to rural areas. Second, as rural communities constitute a critical arena within the national governance system, the new rural elites can leverage their competencies and resource advantages to engage in collaborative governance through informal authority. Lastly, the identity of these new rural elites is recognized as capable of fostering villagers’ sense of belonging, mobilizing shared aspirations for participatory governance, and ultimately enhancing the degree of public engagement in rural governance.

4.3. Participation of Non-Governmental Organization

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are institutionalized collective actors formally registered with civil administration departments, which emerge from non-state initiatives. As quintessential third-sector entities embodying non-profit orientation, civic participation, and voluntary engagement, their core institutional functions encompass the orchestration of philanthropic endeavors and the facilitation of policy-responsive collective action [65]. According to data from the China Social Organization Public Service Platform, the growth rate of NGOs in China has shown a downward trend. The number of NGOs per 10,000 people remains significantly lower than that of developed countries. The sluggish development of social organizations can be attributed to multiple factors, including insufficient total quantity, weak capacity for autonomous survival, low levels of specialization, and inadequate policy support. This issue is particularly pronounced in rural areas, significantly impeding the establishment of a collaborative governance mechanism for urban–rural integrated development. Meanwhile, the study on county-level social governance reveals that the current social formation has undergone a transformation from the traditional high-density structure to an “atomized morphology” [66]. At the grassroots level, this shift renders society prone to falling into a state characterized by the absence of organizational structures and a lack of leadership by elites, which is detrimental to the expression of negative sentiments among vulnerable groups toward administrative measures. Consequently, it is imperative to accelerate the cultivation of NGOs, thereby fostering a new form of social synergy. Such organizations can employ reasonable institutionalized means to engage with governmental authority and articulate their interest demands.

The advancement of political and economic institutional reforms has created conditions for delegating sectors experiencing dual government and market failures to NGOs, thereby leveraging their distinctive advantages as non-profit, voluntary actors in addressing social governance gaps [67]. Empirical evidence indicates a significant disparity in the prevalence of social organizations between urban and rural areas in China, with rural regions exhibiting a substantial numerical lag. Within the contemporary policy framework emphasizing urban–rural integrated development and rural revitalization, it is imperative to intensify efforts to cultivate social organizations in rural localities. This should be accompanied by the provision of professionalized guidance and systematic training programs for both staff members and volunteers within these organizations, thereby enhancing their operational efficacy and sectoral specialization. The legal framework in China explicitly safeguards citizens’ right to association. With the rise of civil society, there has been a marked increase in both awareness and enthusiasm among citizens regarding participation in NGOs and social governance. It is imperative to recognize the catalytic role played by local gentry and community leaders in fostering public consciousness around engagement in communal affairs. Policy measures should incentivize elite members of the rural gentry to leverage their resources, social capital, and reputational influence to establish NGOs in rural areas. This requires institutional support through targeted funding mechanisms, policy frameworks, and professional guidance, thereby enabling the active incorporation of motivated and capable citizens into these social organizations. NGOs are intrinsically driven by voluntarism, altruism, and mutual aid, serving as institutionalized platforms that represent the interests of diverse social strata and groups. By mobilizing disadvantaged and marginalized populations, they provide structured channels for societal members to articulate their demands. Public authorities should enhance the agency of NGOs by granting them greater autonomy, enabling them to identify societal needs and relay them to policymakers in a timely manner. Through the aggregation of multi-stakeholder perspectives, NGOs can thus exert influence on public policy formulation—a mechanism that constitutes an optimal pathway for addressing civic interests and demands. As pivotal actors within the collaborative governance framework, NGOs engage in deliberative co-governance with governmental agencies, the public, and other stakeholders. Their capacity to comprehensively integrate public resources enables them to compensate for the inherent limitations of government-led social governance mechanisms. This collaborative approach serves to enhance the overall efficacy and responsiveness of social governance systems [68].

4.4. Openness of Government Information

Within the context of collaborative governance, there is an intensified emphasis on innovating social governance mechanisms, advancing the development of digital society and digital government, and enhancing the digitization and intelligentization of social governance [69]. This paradigm integrates technological support as a core component of the social governance system. Contemporary social governance is inextricably intertwined with information technology. Emerging technologies such as big data, the internet, and artificial intelligence provide robust scientific and technological support for the innovation of social governance. These advancements enhance governmental operational efficiency and transparency while offering comprehensive technical foundations for the transformation of governance paradigms and the improvement of collaborative governance capabilities [70]. Collaborative governance, in essence, constitutes a form of collective action wherein multiple actors engage in communication and negotiation based on information exchange to arrive at optimal decision-making [71]. Under the traditional social management model, information resources were predominantly monopolized by public sector entities, resulting in asymmetrical power dynamics and unequal dialog between governmental and non-governmental stakeholders. Consequently, the current paradigm of social governance necessitates the establishment of a robust information-sharing mechanism to ensure timely and equitable information exchange among all participating actors.

The coding processes in grounded theory methodology reveals that to advance collaborative governance practices for urban–rural integrated development, multiple regional governments have proactively promoted the establishment of unified e-governance platforms through digital infrastructure. These platforms systematically integrate (1) cross-sectoral information sharing of public resources, (2) unified urban–rural taxation administration mechanisms, and (3) mutual recognition protocols for healthcare insurance between urban and rural populations. As the central actor within the governance system, government agencies acquire substantial first-hand data when delivering public services and exercising administrative functions. These datasets should be systematically integrated, processed, and disclosed to the public to ensure transparency in social governance. The in-depth processing and sharing of valid data and information not only serve as critical evidence for government decision-making processes but also provide effective channels for non-public sector actors to identify social issues and engage in collaborative governance. Despite considerable efforts by governments at various levels to promote administrative transparency, significant challenges persist in public access to government information services.

4.5. Implementation Capacity

To enhance the performance level of collaborative governance and ensure the capacity-building of various social actors in governance participation, it is imperative to first identify the obstacles within the social governance process. For instance, the urban–rural dual structure and household registration system (hukou) in China have significantly impeded the free flow of production factors between urban and rural areas. Additionally, the weakening of social ties among individuals and the pervasive fragmentation of social organizations further exacerbate governance challenges. The rise of civil society and the influence of the New Public Management (NPM) movement have contributed to heightened public awareness of public affairs. However, such engagement remains largely confined to domains directly tied to individual interests, such as social welfare and traffic congestion, while issues like climate change and environmental governance—where the linkage to personal benefits is less immediate—elicit comparatively weaker participatory enthusiasm. The decentralization of governance priorities to the grassroots level in urban and rural communities has intensified contradictions between cadres and the masses, necessitating targeted interventions to address systemic governance barriers—thereby enhancing participatory engagement among stakeholders and fostering residents’ sense of wellbeing.

To eliminate governance obstacles in the process of urban–rural integration and enhance governance execution and efficiency, it is imperative to accord greater prominence to the role of legal safeguards within the social governance framework. The law serves as the cornerstone of national governance, with sound legislation constituting the prerequisite for good governance. It represents both an essential requirement and a critical safeguard for modernizing the state’s governance capacity [72]. This requires the development of localized regulations and government rules tailored to regional contexts, thereby strengthening the legal institutionalization of social governance. In rural areas, the transition from clan-based cultural norms and moral constraints to rule-of-law governance must be systematically advanced. This requires improving the integrated rural governance system that combines self-governance, rule of law, and moral guidance, thereby enhancing the overall legal institutionalization across both urban and rural regions. Furthermore, the collaborative governance process should emphasize cross-regional and interdepartmental cooperation, including the establishment of the Yangtze River Delta Regional Cooperation Office through personnel reassignment to achieve intergovernmental collaboration. During discussions on cooperative intentions, all provinces and municipalities may articulate their respective demands, thereby facilitating strategic intergovernmental alignment and planning coordination. This approach will establish an operational mechanism encompassing decision-making, coordination, and implementation tiers. In the implementation of urban–rural integration policies, grassroots departments must accurately identify systemic obstacles within the governance process. Each administrative unit should formulate standardized and professional implementation plans while maintaining cross-regional and interdepartmental coordination. This dual approach enhances policy implementation capacity and ensures the effective fulfillment of policy objectives with guaranteed quality. Simultaneously, the establishment of demonstration zones and pilot areas facilitates the replication and dissemination of successful governance practices, thereby generating more profound policy impacts.

4.6. Supervision and Evaluation

A fundamental prerequisite for effective public supervision is citizens’ access to information regarding governmental activities. The disclosure of government information serves as a critical prerequisite for enabling diverse governance actors to conduct effective supervision and evaluation of collaborative governance capacity and performance. Contemporary public finance theory posits that the fundamental relationship between taxpayers and the government constitutes a principal-agent paradigm, thereby obligating the government to disclose its operational performance to the public for effective societal oversight. Public oversight refers to the monitoring exercised by civil society, which serves as a complementary mechanism to state supervision. This form of societal constraint can effectively reduce the probability of collusion between regulatory agencies and the government within formal state oversight systems, thereby mitigating agency costs in public governance. However, extant research and practical applications have insufficiently acknowledged the significance of public oversight. Logically, as the agent of the public, the government is inherently subject to public monitoring. Public oversight constitutes a supplementary accountability mechanism that complements formal monitoring by state authorities, thereby enhancing the integrity of public governance systems [73]. Building upon government disclosure of public affairs, citizens acquire the capacity to scrutinize, analyze, advise on, and hold accountable governmental conduct. This enables their substantive participation in collaborative governance as legitimate stakeholders, thereby exerting measurable influence on state actions. The establishment of clearly defined evaluation metrics for urban–rural integrated development and collaborative governance standards is imperative for constructing a scientific, systematic monitoring and assessment framework [26,27]. Such a framework must comprehensively oversee all participating subjects, policy objects, and operational processes within the collaborative governance system. At the level of internal supervision, it is imperative to legally empower non-public sector entities to participate in the performance evaluation of social governance, while simultaneously regulating the conduct of various actors within the governance system. Public authorities must exercise their social functions in accordance with established norms, whereas non-governmental organizations and the public should articulate their interests through legitimate channels. This approach ensures the protection of supervisory rights for multiple stakeholders, while also guaranteeing that oversight mechanisms remain standardized and impartial. At the level of external supervision, it is essential to establish specialized and credible monitoring and evaluation institutions in both urban and rural areas, supported by a scientific assessment framework. These institutions should conduct systematic impact evaluations in regions where new policies promoting urban–rural integrated development are implemented. Concurrently, a participatory evaluation and feedback platform should be developed to facilitate direct input from urban and rural residents, thereby enhancing the alignment of public service provision with citizen needs and accurately reflecting governance performance. Furthermore, third-party evaluation agencies must themselves be subject to oversight from both society and the public to ensure accountability and transparency.

5. Conclusions

The urban–rural integrated development constitutes a fundamental imperative for achieving rural revitalization. It is equally critical for promoting new urbanization and facilitating a comprehensive reconceptualization of the relationship between cities and the countryside. This paper aims to excavate the key governance elements embedded in the practice of collaborative governance for urban–rural integrated development in the Yangtze River Delta region, with the objective of providing strategic insights and policy recommendations for advancing urban–rural integration and facilitating the implementation of the rural revitalization strategy in contemporary China. By employing a rigorous grounded theory methodology, which is grounded in the extensive review of policy documents, collection of interview data, and field investigations, this study constructs a theoretical model to elucidate the influencing mechanisms of collaborative governance in promoting urban–rural integrated development in the Yangtze River Delta region. This model aims to navigate the governance orientation amidst the intricate and multifaceted collaborative processes. Accordingly, this study conducts a meticulous comparative analysis of all conceptual labels, followed by multiple rounds of systematic examination of both primary and secondary categories. Through iterative comparisons and deliberations, it ultimately synthesizes six core categories: policy planning capability, public participation, participation of NGOs, openness of government information, supervision and evaluation, and implementation capacity.

In terms of policy planning capability, when formulating policy frameworks, public authorities should capitalize on the comparative advantages of both urban and rural systems, abandoning the path dependency of the “rural → urban” mobility paradigm and dismantling the institutional barriers inherent in the “rural → urban” flow pattern. This approach aims to maximize parallel development between urban and rural spheres, ultimately establishing a coupled interaction mechanism and achieving symbiotic integration of urban–rural development. In terms of public participation, public sectors should provide more platforms and channels for social learning, disseminating the necessity and importance of public affairs participation to urban and rural community residents. Public participation and feedback serve as an effective measure for evaluating the capacity and performance of social collaborative governance. Conversely, robust social collaborative governance capabilities can foster greater public willingness to engage, creating a mutually reinforcing and virtuous cycle between the two. In terms of participation of NGOs, to facilitate the urban–rural integrated development, it is crucial to implement a downward shift in the focus of collaborative governance by effectively leveraging NGOs in addressing public crises, social assistance, and philanthropic activities. Through coordinated efforts with government entities and the public, NGOs can generate synergistic effects to substantially mitigate social problems arising from “government failure”. In terms of openness of government information, current issues include delayed information updates, occasional inaccuracies, inter-departmental data discrepancies, and low levels of information integration, all of which substantially compromise user experience. These problems collectively constitute the “last-mile” dilemma in government transparency services. Consequently, it is imperative to adopt a citizen-centric approach to information disclosure, leveraging information technology to optimize governance frameworks and enhance institutional capacity. In terms of implementation capacity, legislative bodies should formulate programmatic laws for collaborative governance, which delineate the boundaries of rights, obligations, and conduct for all stakeholders, standardize their participation in governance processes, and ensure legal grounding for key procedures such as information disclosure, grievance reporting, and public deliberation. In terms of supervision and evaluation, performance-based supervision and evaluation of grassroots urban and rural community work can significantly enhance the governance efficacy of public authorities, non-governmental organizations, and the general public. This approach strengthens the implementation capacity and efficiency of social governance, incentivizing local public sectors to prioritize livelihood issues, mitigate social conflicts, and promote social equity. Ultimately, it contributes to sustainable societal development. These core categories form the theoretical framework of the impact mechanism of collaborative governance on urban–rural integrated development in the Yangtze River Delta region. As a region with advanced economic development and a high level of urban–rural integration, the Yangtze River Delta should leverage its strengths to foster participation from the public and NGOs in governance, enhance the transparency of government data, and improve the planning, implementation, and monitoring of policies, thereby elevating the performance of collaborative governance.

The findings of this study offer valuable reference insights for urban–rural development and collaborative governance in other regional contexts. However, it is important to acknowledge that the Yangtze River Delta region exhibits distinct characteristics—including its advanced economic development and high level of urban–rural integration—which may limit the direct transferability of our findings to regions with different socioeconomic conditions. This constitutes a recognized limitation of the present study. Future research should aim to incorporate case studies from other regions, thereby enabling comparative analysis and the development of more universally applicable governance recommendations.

Author Contributions

K.X.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft preparation, funding acquisition. S.W.: Supervision, Writing—review and editing. K.D.: Data curation. W.H.: Resources. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Jiangsu University Philosophy and Social Sciences Research General Project, grant number 2025SJYB1626; This research was funded by the Chongqing Federation of Social Sciences, grant number 2022BS074; This research was funded by the Major Special Project of Sichuan Provincial Philosophy and Social Sciences Foundation, grant number SCJJ24ZD39; This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province, grant number 2023J05098.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NGOs | Non-governmental organizations |

References

- Wang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, Y. Can the integration between urban and rural areas be realized? A new theoretical analytical framework. J. Geogr. Sci. 2024, 34, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Xie, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhong, T.; Lin, Y.; Wang, M. The Transformation of Peri-Urban Agriculture and Its Implications for Urban–Rural Integration Under the Influence of Digital Technology. Land 2025, 14, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C. On integrated urban and rural development. J. Geogr. Sci. 2022, 32, 1411–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yang, L.; Wang, H.; Yang, S.; Yan, Z. Spatiotemporal Evolution Characteristics and Impact Factors of Urban-rural Integrated Development in China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2025, 35, 802–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Long, H.; Liao, L.; Tu, S.; Li, T. Land use transitions and urban-rural integrated development: Theoretical framework and China’s evidence. Land Use Policy 2020, 92, 104465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Yang, Y.; Ye, W.; Liu, L.; Gu, X.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y. Study on the Efficiency, Evolutionary Trend, and Influencing Factors of Rural-Urban Inte-gration Development in Sichuan and Chongqing Regions under the Background of Dual Carbon. Land 2024, 13, 696. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, J. The Logic of Grassroots Administrative Regions Governance in Integrated Urban-Rural Development—A Case Study of Suburban Land Use. Adm. Trib. 2024, 2, 21–30. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.-G.; Xu, K.; Duan, K. Investigating the intention to participate in environmental governance during urban-rural integrated development process in the Yangtze River Delta Region. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 128, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Yin, L.; Yan, C. Urban-Rural Logistics Coupling Coordinated Development and Urban-Rural Integrated Development: Measurement, Influencing Factors, and Countermeasures. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 2969206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, L.; Wang, S.; Xie, S.; Zhang, Q.; Qu, Y. Spatial path to achieve urban-rural integration development—Analytical framework for coupling the linkage and coordination of urban-rural system functions. Habitat Int. 2023, 142, 102953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Fan, Y.; Fang, C. When will China realize urban-rural integration? A case study of 30 provinces in China. Cities 2024, 153, 105290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yu, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, T.; Liu, J.; Peng, D.; Zhang, X.; Fang, C.; Gong, P. China’s ongoing rural to urban transformation benefits the population but is not evenly spread. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.Z.; Mao, R.; Zhou, Y. Rurbanomics for common prosperity: New approach to integrated urban-rural development. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2023, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-C.; Ma, Z.; Nguyen-Phuoc, D.Q.; Fu, X. Influential factors and passenger satisfaction towards integrated urban-rural bus services: A case study of Chibi, China. Transp. Policy 2025, 172, 103769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wen, C.; Fang, X.; Sun, X. Impacts of urban-rural integration on landscape patterns and their implications for landscape sustainability: The case of Changsha, China. Landsc. Ecol. 2024, 39, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R. Urban-rural integration and rural revitalization: Theory, mechanism and implementation. Geogr. Res. 2018, 37, 2127–2140. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L.; Yan, J.; Du, Y. Identifying the Turning Point of the Urban–Rural Relationship: Evidence from Macro Data. China World Econ. 2018, 26, 106–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.H.; Ren, Y.Y.; Ma, D.M.; Yu, M.M. Retrospect and analysis to the progress, predicament and frame in the urban–rural relations of China since 1949. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2015, 29, 6–12. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Guo, S.; Yuan, H. The impact of total factor mobility on rural-urban symbiosis: Evidence from 27 Chinese provinces. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0294788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, X.; Ye, C. The Integration of New-Type Urbanization and Rural Revitalization Strategies in China: Origin, Reality and Future Trends. Land 2021, 10, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhou, M.; Wang, S. Localized practices of rural tourism makers from a resilience perspective: A comparative study in China. J. Rural Stud. 2025, 119, 103722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhu, M.; Xiao, Y. Urbanization for rural development: Spatial paradigm shifts toward inclusive urban-rural integrated development in China. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 71, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Liu, S.; Fang, F.; Che, X.; Chen, M. Evaluation of urban-rural difference and integration based on quality of life. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 54, 101877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Perc, M.; Zhang, H. A game theoretical model for the stimulation of public cooperation in environmental collaborative governance. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2022, 9, 221148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, B.; Sekulova, F.; Hörschelmann, K.; Salk, C.F.; Takahashi, W.; Wamsler, C. Citizen participation in the governance of nature--based solutions. Environ. Policy Gov. 2022, 32, 247–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative Platforms as a Governance Strategy. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2018, 28, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Ran, B. Paradoxes in collaborative governance. Public Manag. Rev. 2023, 26, 2728–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Liu, Z. Rural-urban co-governance: Multi-scale practice. Sci. Bull. 2020, 65, 778–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Xu, Y. Carbon reduction of urban form strategies: Regional heterogeneity in Yangtze River Delta, China. Land Use Policy 2024, 141, 107154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Mao, C. Evolutionary Game Analysis of Ecological Governance Strategies in the Yangtze River Delta Region, China. Land 2024, 13, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Ge, D.; Sun, J.; Sun, D.; Ma, Y.; Ni, Y.; Lu, Y. Multi-scales urban-rural integrated development and land-use transition: The story of China. Habitat Int. 2023, 132, 102744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, Z.; Li, M.; Zhang, H.; Li, M.; Qiu, X.; Zhou, C. Carbon emission and economic development trade-offs for optimizing land-use allocation in the Yangtze River Delta, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 147, 109950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.L. Qualitative Analysis for Social Scientists; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Goldkuhl, G.; Cronholm, S. Adding Theoretical Grounding to Grounded Theory: Toward Multi-Grounded Theory. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2010, 9, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman-MacLaren, M.; Mills, J. Transformational Grounded Theory: Theory, Voice, and Action. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2015, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafer, J. Developing the Theory of Pragmatic Public Management through Classic Grounded Theory Methodology. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2022, 32, 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y. Civic Participation in Chinese Cyber Politics: A Grounded Theory Approach of Para-Xylene Projects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 18, 12458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, M. Language and Political Understanding. Philosophy 1983, 58, 552–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, L. Public Opinion; Shanghai People’s Press: Shanghai, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.; Maybin, J. Documents, Practices and Policy. Evid. Policy 2011, 7, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Murat, B.; Li, J.; Li, L. How can Policy Document Mentions to Scholarly Papers be Interpreted? An Analysis of the Underlying Mentioning Process. Scientometrics 2023, 128, 6247–6266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, C.; Sergio, S. Mapping Science in Artificial Intelligence Policy Development: Formulation, Trends, and Influences. Sci. Public Policy 2024, 51, 1104–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Lin, X. Research on digital spillover effect of internet enterprises—An exploratory study based on grounded theory. Appl. Econ. 2023, 56, 4776–4790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Yu, X. The connotation, cause, and reform path of institutional transaction costs: A grounded theory analysis. Local Gov. Stud. 2024, 50, 893–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nah, F.; Tan, X. An Emergent Model of End-users’ Acceptance of Enterprise Resource Planning Systems: A Grounded Theory Approach. J. Database Manag. 2015, 26, 44–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, D.R.; Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K.; Thornberg, R. The pursuit of quality in grounded theory. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2020, 18, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.; Davey, M. The value of constructivist grounded theory for built environment researchers. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2018, 38, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, Y. From Native Rural China to Urban-rural China: The Rural Transition Perspective of China Transfor-mation. Manag. World 2018, 34, 128–146. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; LeGates, R.; Zhao, M.; Fang, C. The changing rural-urban divide in China’s megacities. Cities 2018, 81, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Sun, P.; Liu, H.; He, J. Spatial-temporal Evolution of the Urban-rural Coordination Relationship in Northeast China in 1990–2018. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2021, 31, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Liu, S. Does urbanization promote the urban-rural equalization of basic public services? Evidence from prefectural cities in China. Appl. Econ. 2024, 56, 3445–3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhu, Y. Impact of Labour Productivity Differences on Urban--Rural Integration Development and Its Spatial Effect: Evidence from a Spatial Durbin Model. Complexity 2022, 2022, 4675682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertel, T.; Zhai, F. Labor market distortions, rural–urban inequality and the opening of China’s economy. Econ. Model. 2006, 23, 76–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.; Hu, B.; Zhu, D. Do Regional Integration Policies Promote Integrated Urban–Rural Development? Evidence from the Yangtze River Delta Region, China. Land 2024, 13, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Deng, X.; Hui, E.C. Development of characteristic towns in China. Habitat Int. 2018, 77, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Pan, J.; Liu, Z. The historical logics and geographical patterns of rural-urban governance in China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2022, 32, 1225–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.K. Public Values and Public Participation: A Case of Collaborative Governance of a Planning Process. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2021, 51, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, T.A.; Thomas, C.W. Unpacking the Collaborative Toolbox: Why and When Do Public Managers Choose Collaborative Governance Strategies? Policy Stud. J. 2017, 45, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharov, A.; Bondarenko, O. Social status and social learning. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2021, 90, 101647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.L.-H. The dilemma of renqing in ISD processes: Interpretations from the perspectives of face, renqing and guanxi of Chinese cultural society. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2012, 31, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Zhang, D.; Irwin, D.D. The Prevalence and Importance of Semiformal Organizations and Semiformal Control in Rural China: Insights from a National Survey. Asian J. Criminol. 2022, 17, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, H.; Jiang, H.; Leung, J.C.B. The changing relationship between the Chinese Government and Non-governmental Organisations in social service delivery: Approaching partnership? Asia Pac. J. Soc. Work Dev. 2019, 29, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Tan, L. Quality Differences and Influencing Dimensions of County Social Governance under the Background of High Quality Development. J. Henan Norm. Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2021, 48, 67–77. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Doucet, T.C.; Duinker, P.N.; Charles, J.D.; Steenberg, J.W.; Zurba, M. Characterizing Non-governmental Organizations and Local Government Col-laborations in Urban Forest Management Across Canada. Environ. Manag. 2024, 73, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapia, F.; Oxhoa-Peralta, D.; Reith, A. From design to action: Service design tools for enhancing collaboration in nature-based solutions implementation. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 379, 124739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhan, G.; Dai, X.; Qi, M.; Liu, B. Innovation and Optimization Logic of Grassroots Digital Governance in China under Digital Empowerment and Digital Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanisch, M.; Goldsby, C.M.; Fabian, N.E.; Oehmichen, J. Digital governance: A conceptual framework and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 162, 113777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNaught, R. The application of collaborative governance in local level climate and disaster resilient development—A global review. Environ. Sci. Policy 2023, 151, 103627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, R. Role of Law, Position of Actor and Linkage of Policy in China’s National Environmental Governance System, 1972–2016. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Gu, X.; Li, Z.; Lai, Y. Government-enterprise collusion and public oversight in the green transformation of resource-based enterprises: A principal-agent perspective. Syst. Eng. 2024, 27, 417–429. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).