Abstract

The article examines mechanisms for reorganizing leased agricultural land in Ukraine and Germany to foster sustainable agricultural structures. Both countries face distinct challenges: Ukraine confronts the dual challenge of war-related land rehabilitation and farm structural modernization, while Germany aims to integrate ecological considerations into voluntary lease reorganization. The study analyzes the legal and practical frameworks governing agricultural leases, identifies unresolved challenges, and develops approaches for implementing sovereign land consolidation tools. By addressing issues such as land use fragmentation and “patchwork” of leased parcels within the same field, this research proposes solutions for achieving long-term stability in agricultural structures through land lease reorganization. It also explores integrating ecological practices into lease agreements to balance economic productivity with environmental sustainability. The findings emphasize the need for tailored legal, institutional, and procedural frameworks to ensure agricultural land use’s long-term viability and resilience in both countries.

1. Introduction

Agriculture forms a fundamental basis for every society to ensure food security, even if it is fundamentally possible to supply a society with food produced worldwide in times of globalization. The crises of recent years have shown how vulnerable such a supply can be. At the same time, locally produced food promotes responsibility for the environment and reduces the ecological footprint. In this respect, local value chains in food production provide economic as well as ecological and social benefits.

Accordingly, agriculture needs the necessary framework conditions to establish such local value chains. These include efficiently cultivable areas with suitable access to ensure stable farming conditions. At the same time, the ecological situation should at least be stabilized. Where this is disturbed, improvement measures must be taken. Both are only possible if the necessary adjustments to the ownership and tenure of agricultural land are also possible. Achieving these goals requires a stable framework for agricultural land use, including effectively managing land tenure and ownership structures. Sustainable farming is contingent upon sustainable agricultural structures, which can be achieved through land consolidation and coherent lease agreements, which prevent land fragmentation and facilitate improved agricultural practices.

The fragmentation of agricultural land remains one of the most significant structural issues in making farming more efficient and sustainable. In several Central and Eastern European countries, including Ukraine, past land reforms and privatization processes have led to fragmented ownership and lease structures, resulting in ineffective land use and unstable land tenure. In Western Europe, particularly in the southwestern states of Germany, small-scale land structures arose mostly as a result of the inheritance law that previously applied to agricultural land and farms (real division law []), and such issues have been mostly handled because of effective land management institutions and land consolidation tools.

As a method for improving farm structures in Europe, land consolidation is not a new concept [,,,,]. However, it is less widely recognized that land lease reorganization can be valuable for assembling land into sustainable structures. Elvestad and Sky [] consider land consolidation as an instrument to reduce the fragmentation of leased agricultural land and propose three possible options within the framework of Norwegian legislation. Analyzing the experiences of the Netherlands, Romania, and Turkey, Louwsma & Lemmen [] emphasize the critical importance of considering leased land for successful consolidation irrespective of the presence of a formal or informal (informal land leasing) land market. The authors argue that ignoring informal tenure rights (land use) during land consolidation will not help solve the problem of fragmentation. Existing international works [,] focus mainly on the study of the rights and role of landowners as lessors, their interest in participating in land consolidation, and compliance with existing lease agreements. The practice of land consolidation is mainly based on the fact that landowners and/or lessors, as landowners, are the primary (key) participants in this process. With this approach, as a rule, lessees play a secondary role and often do not directly impact decision-making on land re-allotment. Thus, the issue of the lessee’s or lessees’ initiative in improving the structure of agricultural land use through land consolidation, especially for countries without a land consolidation procedure, remains understudied. It can be a crucial gap for countries where the agricultural land lease ranges between 60% and 90%. Under such conditions, lessees play a key role in optimizing agricultural land use, since their interests and needs are directly related to efficient land use. Underestimating the lessees’ role in assembling land into sustainable structures is unacceptable in this context. Their active participation and involvement in the decision-making on land lease reorganization are critically important for achieving positive results.

There is a trend in Europe towards an increase in leasing agricultural land []. This phenomenon is explained by various reasons, including the need to respond to modern technological and market challenges by forming larger and more efficient farms, as well as the improper functioning of the land market. However, the legal frameworks governing agricultural leases vary significantly between countries, presenting unique challenges and opportunities.

This issue is particularly relevant in the Ukrainian context. Due to the nearly two-decade ban on the purchase and sale of agricultural land, land leasing reached phenomenal proportions, serving as the only available tool for improving the structure and increasing the area of agricultural enterprises (farms). Therefore, it is unsurprising that many Ukrainian researchers [,,,,] associated land leasing with land consolidation. They define land leasing (especially long-term land leases of more than 10 years) as a form of land consolidation that facilitates farm (agricultural enterprises) enlargement through a clearly defined legal framework for lease agreements. Noting positive trends in the increasing farm size, researchers focus on the ambiguous role of agroholdings as the main lessees of agricultural land. On the one hand, these structures consolidate substantial land areas through leasing, increasing operating efficiency, and providing income (rent) to landowners. On the other hand, agroholdings are not necessarily intended to promote rational land use and land protection. Opposing views [,,,] argue that land leases cannot be considered land consolidation because it does not involve rearranging land rights. Thus, the land lease is a temporary measure confined to the lease agreement term. When the lease agreement ends, there are no guarantees regarding the conclusion of a new lease agreement with the same lessor(s). This can result in a return to land fragmentation. These studies highlight the multifaceted nature of using land leases as a tool for better layout of leased farmland and emphasize the importance of having a clear mechanism for reorganizing agricultural leased land to create more sustainable agricultural structures.

In this context, it is essential to distinguish between the two key instruments: land consolidation and lease reorganization. Land consolidation is a sovereign (public-law) procedure that restructures ownership through the reallocation of property rights. As a result, land consolidation leads to a permanent reconfiguration of land tenure structures, as ownership boundaries and titles are legally modified by an administrative decision, and participation is generally compulsory for all owners within the designated area once the process is initiated. In addition to changing property rights, existing leasehold rights are also reorganized to the extent necessary due to the changed property rights. Of course, leasehold rights can also be reorganized beyond this if the rights holders concerned agree to this.

In this paper, the term “land lease reorganization” refers to the process of reorganizing the spatial configuration and legal relationships of existing leasehold rights on agricultural land to enhance the efficiency and coherence of land use. The ownership rights to the land are not reorganized in this process. Land lease reorganization, in contrast to land consolidation, is a private law tool that focuses on the temporary re-arrangement of land use rights (leases) with preserving the existing ownership structures. It is primarily operated voluntarily by landowners and lessees, with no state (public) force. Although lease reorganization can help to improve spatial integrity and land use efficiency, its impact is limited by the duration and terms of lease agreements.

When viewed through the analytical dimensions of the nature of property-rights reconstruction and the degree of compulsoriness, lease reorganization can therefore be understood as a complementary or transitional instrument rather than a complete alternative to land consolidation—particularly in contexts such as Ukraine, where the formal framework for sovereign land consolidation is not yet institutionalized. Of course, the tool is also used (e.g., in Germany–expert interview 29 October 2025) in the run-up to or after a land consolidation process to achieve rapid adjustments to existing change processes.

This study examines land lease reorganization as a distinct contractual process operating within existing property systems. Therefore, the main idea is not to directly analyze land consolidation procedures (very up-to-date descriptions of the situation in Germany can be found, for example, at []), but to assess whether land lease reorganization can serve as a functional complement to land consolidation or as a standalone tool that enhances spatial coherence and stability in agricultural land use. This distinction is crucial for interpreting the comparative results presented in this paper.

The article aims to explore and propose mechanisms for reorganizing agricultural leased land in Ukraine and Germany to create more sustainable agricultural structures, examining whether such reorganization can fully substitute for land consolidation. This research examines the potential of leased land reorganization as an alternative or complementary tool to traditional land consolidation methods to create more sustainable agrarian structures, particularly considering how national characteristics influence approaches and challenges in land lease management.

In the Ukrainian context, a particular challenge is the need for structural transformation of the agricultural sector and restoring lands damaged by the war. The research focuses on how land lease reorganization, especially given excessive leased land resulting from the long-standing moratorium on agricultural land sales, can address problems such as land use fragmentation, illegal cultivation of field roads, and the complexities arising from the large number of leases concluded by large agroholdings. Furthermore, the study examines clear legislative approaches concerning dominant land users and assesses the practical effectiveness and limitations of such a majority-based approach.

The study aims to critically characterize voluntary approaches to reorganizing leased land based on private law in the German context. Given the continued concentration of farms and the increasing share of leased land in Western Germany, the research aims to assess the extent to which these voluntary methods are successful or unsuccessful in creating cohesive, effectively managed farms. Another objective is to analyze the possibilities for integrating environmental priorities (e.g., preserving biodiversity) into the reorganization of leases, offering more systemic, possibly locally supported or regulated solutions instead of purely voluntary lease agreements.

Furthermore, the research seeks to fill a notable gap in the existing literature, which often emphasizes the role of landowners in land consolidation while potentially underestimating the crucial role and initiative of lessees, especially in countries where leases dominate land tenure (e.g., Ukraine). The comparative analysis of the Ukrainian and German experiences in this research serves as a basis for identifying common lessons and developing models suitable for both countries, considering their specific legal, economic, and social contexts.

This article begins by discussing the current developments in agricultural enterprises as well as ownership and tenure structures in Ukraine and Germany. As a first step, Section 3.1 presents and compares the current trends and development patterns in both countries, based on statistical data, including the share of leased land, the size of the management units, and agricultural enterprises. In Section 3.2, the given legal situation regarding the land leasing framework in both countries is analyzed and compared, using preparatory documents, relevant acts, circulars, and reports. To check the relevance of older data and information taken from the literature and to update it, if necessary, experts from Western German states who have supported the voluntary land lease reorganization in the past and continue to do so today were interviewed. Additionally, the challenges of the current application of land lease reorganization processes in both countries are analyzed. After that, it identifies obstacles to its application and conducts a stakeholder analysis to clarify the influence of the various actors on the decision-making process for implementing a land lease reorganization in accordance with the current legal situation in both countries and to draw conclusions for future adaptation requirements. Subsequently, Section 3.3 describes the current possibilities for adapting the lease structure of agricultural land in both countries, as well as challenges that have not yet been resolved. Section 4 subsequently focuses on interpreting these results and discussing the future development of the land lease reorganization tool in both countries. Based on this, approaches are developed to introduce a land lease reorganization instrument in both countries, creating sustainable structures in economic, ecological, and social terms. The conclusive findings of this research are then presented and emphasized in Section 5.

2. Materials and Methods

To answer the research questions posed in the introduction, a comparative analysis method was chosen to compare current developments and challenges in dealing with ownership and leasing of agricultural land in Germany and Ukraine. The combined analysis of both countries allows conclusions to be drawn as to how the respective challenges can be overcome. Due to the selected comparison criteria, both quantitative and qualitative indicators are considered. The basic approach, drawing on the results of a literature analysis, consists of a comparative analysis of the two countries, Ukraine and Germany, concerning approaches to reorganizing leased land.

The study’s second methodological pillar was a comprehensive qualitative content analysis of foundational legal documents. This method was chosen to deconstruct the legislative architecture of land management in Ukraine, providing critical insight into its formal structures and operational procedures. The analysis focused primarily on key Ukrainian legislative acts, including: the Land Code of Ukraine, which establishes the fundamental provisions on the exchange of land use rights; the Law “On Land Lease” No. 161-XIV, which regulates the legal relations of leasing land, defining the terms, rights, obligations, and procedures for land lease agreements; the Law “On State Land Cadaster” No. 3613-VI, which defines the provisions for registering the agricultural land massif in state land cadaster for the possibility of exchanging of land use rights within such massif; and the Law “On State Registration of Real Estate Rights and Their Burdens” No. 1952-IV, which regulates the registration of use rights including lease rights. These documents formed the legislative basis for the study.

The legal documents were selected in such a way as to guarantee the representativeness, compatibility, and relevance of the legislative sources in both national contexts. The selected materials included key legal acts regulating agricultural land use, land lease, and land consolidation in Ukraine and Germany, as well as subordinate implementing regulations and official advisory documents of the bodies responsible for implementing land tenure policy. Ukrainian legal documents were obtained from the official legislation database of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, while German laws were obtained from the official publications of the legislative bodies. The inclusion criteria required that each document directly regulate land tenure, lease relations, or land consolidation; have national legal validity; and be in force or historically significant for the period of comparison (2000–2024). The analysis process employed a qualitative content analysis approach. Each legal text was reviewed to identify the legal definition of the lease framework and ownership rights, institutional responsibilities, and procedures, as well as the extent to which the document addressed spatial and tenure structures relevant to land use organization. This structured approach ensured methodological consistency, which allowed for a systematic and transparent comparison of legal documents between Ukraine and Germany.

The next methodological pillars were a comparative assessment of governance arrangements, focusing on the roles of administrative authorities, land users, and local self-government, and the authors’ expert-based interpretive synthesis, which translated the comparative findings into a framework for the land lease reorganization. The framework was not derived inductively from a single dataset but rather through interpretive comparison of legal, organizational, and procedural structures identified in Germany and Ukraine, supplemented by expert interviews in Germany. By analyzing the interaction between public institutions, lease regulations, and spatial management practices, the study abstracted a set of functional conditions that enable the coordination and reorganization of leased agricultural land.

The choice of Germany and Ukraine as comparative cases is based on their markedly different yet complementary institutional and spatial contexts of agricultural land management. Germany is a robust Western European model of property offered by a well-established system of property rights, secure lease relationships, and an integrated land consolidation and spatial planning system. It is the model of a lease mechanism in place within a consistent and legally secure context, with public institutions acting to ensure spatial cohesion and land tenure stability. Ukraine is an example of a post-socialist transition model characterized by an agricultural sector with excessive lease-based land use, mainly due to the historical moratorium on agricultural land sales and the absence of land consolidation. The country is situated in a dynamic and evolving institutional context, albeit during a period of war, with land reforms currently underway to enhance land governance and secure land tenure. Using these two cases provides a rare opportunity to investigate how conflicting institutional settings could affect the results of land lease reorganization. A comparison of Germany’s institutional sophistication with Ukraine in transition enables this study to examine whether the concepts and instruments of leasing reorganization might be conducive to achieving stronger agricultural structures in countries where formal land consolidation systems are not yet operational.

The limitation of this article is that the statistical data represent agricultural land use in Ukraine as of 24 February 2022, excluding the temporarily occupied territories of Crimea and parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts.

This date marks the endpoint of data collection, at which complete and verified land use data for the country could be obtained.

Events that occurred after February 2022 led to a profound transformation, rendering any subsequent data irrelevant for the purposes of our comparison. The full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine led to fundamental changes in land use (occupation, destruction, and contamination of land), as well as to informational and legal reconfiguration. Access to many state geoportals, including the Public Cadastral Map of Ukraine, was closed for security reasons. Moreover, special legislation was enacted (e.g., Laws No. 2145-IX [] and No. 2247-IX []), which significantly restricts land transactions and land use during wartime.

We believe that data obtained during the war cannot be considered representative of the pre-war situation. That is why the article intentionally limits the Ukrainian statistical dataset to 2022, providing a reliable basis for comparative analysis with Germany.

3. Results

With the advancement of mechanization in agriculture, concentration processes are taking place on farms []. In many cases, the land of abandoned farms is leased rather than sold for economic reasons. This leads to increased leased land, as illustrated by the development in Ukraine and Germany described below.

3.1. Development of Land Ownership and Tenure

3.1.1. Ukraine

Land reform resulted in the privatization of 12,421 collective agricultural enterprises and state farms by subdividing 27.5 million hectares of agricultural land—66% of the country’s total agricultural land—and transferring it to the private ownership of 6.9 million Ukrainian citizens []. These new landowners were former employees of collective farms or rural service workers, such as teachers and healthcare providers. About 40% of Ukraine’s rural population became landowners, with parcels averaging 4 ha. Parcel sizes vary regionally, from 8.69 ha in the eastern part to 1.1 ha in the western part of Ukraine. Notably, land parcels within the territory of privatized collective agricultural enterprises have an equal normative monetary value1, and their size depends on the soil quality—the better the soil, the smaller the land parcel size.

As of 2020, Ukraine’s total agricultural land area of 41.4 mm ha (including arable and non-arable land) covers 68.7% of the country (with 55% being arable land) of which 31 mm ha are privately owned, 1.7 mm ha are owned by communities, and 8.7 mm ha remain under state ownership. Agricultural production in Ukraine is primarily divided between agricultural enterprises and households. Agricultural enterprises (including farms), around 39.301 with a total area of 20.2 million ha, produce 68% of the gross output. The second group includes over 4 million households (smallholders and peasant farms) with a total area of 6.1 million hectares, cultivating an average of 1.23 hectares per holding, generating nearly 32% of gross agricultural output []. Households operating on small land parcels and an area three times smaller produce a third of gross agricultural output. This highlights the productivity and resilience of small-scale farming, which provides a substantial share of the national output relative to its land area. While enterprises drive high output through efficient use of large areas, smallholders maintain considerable output on limited land, underscoring their importance in local economies and food security.

Between 2008 and 2021, the average land area of agricultural enterprises expanded from 420 to 1250 hectares, and farms grew from 113 to 186 hectares, mainly due to a decrease in small and medium-sized holdings. This increase is primarily attributed to a decline in the number of small and medium-sized holdings, as shown in Table 1 and Table 2. By the end of 2020, the 117 largest agroholdings collectively managed 6.45 million ha, accounting for 16% of all agricultural land in Ukraine.

Table 1.

Grouping of agricultural enterprises by the area of agricultural land in use [].

Table 2.

Grouping of farms by the area of agricultural land in use [].

3.1.2. Germany

Due to historical developments, Germany ultimately has a three-part agricultural structure. Because of the right of primogeniture that applies in northwestern Germany, farms and agricultural land are rarely divided there, so that the agricultural structure is characterized by larger plots of land and farms, which are usually owned by families. In contrast, the real division of property law customary in southwestern Germany has led to very small plots of land and agricultural businesses, which are also owned by families. During the era of the German Democratic Republic, the eastern German states experienced an almost complete dissolution of family-run farms. Instead, large state-owned agricultural enterprises were formed, which continued to operate as private agricultural holdings after reunification. Due to their market-dominating position and the lack of alternatives for individual landowners, the farming units are large to very large, although there are also very small-scale ownership structures, especially in the southeastern federal states [].

The existing agricultural structure and the industrialization of agriculture, combined with a lack of farm successors, have led to a significant decline in the number of farms in recent decades. The number of farms in Germany has fallen considerably since the Second World War, from more than 1.7 million farms in 1949 to 255,100 in 2023. At the same time, the utilized agricultural area in Western Germany fell by 1,613,700 ha between 1949 and 1995 and by 651,900 ha for Germany as a whole between 1995 and 2020. The average size of a farm with 5 ha or more agricultural land increased from 42.8 to 68.6 ha for Germany between 1995 and 2020. In the same period, the average size in the new federal states fell from 273.2 to 241.9 ha, with the number of farms over 200 ha increasing from 5414 to 6598 [].

3.1.3. Comparative Analysis

A comparison of Ukraine and Germany shows that the southwestern German states and Ukraine in particular have similar small-scale ownership structures for agricultural land. While these structures in the southwestern German states are largely determined by inheritance law, those in Ukraine were created by the privatisation of collective agricultural enterprises and state farms.

In Ukraine, land reform resulted in a large number of small private owners (approximately 6.9 million citizens receiving parcels averaging 4 hectares), but productive control of agricultural land concentrated rapidly in larger enterprises and agro-holdings that operate primarily on leased plots. This duality, characterized by many small owners on paper but concentrated operational control in larger leasing enterprises, describes Ukraine’s mixed but increasingly consolidated agrarian structure.

Germany, by contrast, displays a historically differentiated three-part agricultural structure rooted in varied inheritance regimes and the legacy of division between West and East. The German pattern combines (a) relatively large family farms in regions with primogeniture, (b) very small ownership structures in regions with equal partition traditions, and (c) large former state units (particularly in the eastern states) that persisted as large private holdings after reunification. Over the decades, the country experienced a strong decline in the number of farms, while average farm sizes increased (for Germany overall and in specific regions), resulting in a structural shift toward fewer but larger operational units.

Thus, whereas Ukraine’s land concentration has been driven chiefly by leasing of numerous small private parcels to larger enterprises, Germany’s consolidation is shaped by historical ownership patterns, demographic succession issues, and market-driven farm exits.

3.2. Land Lease Frameworks

A prerequisite for the development and use of land leasehold reorganization procedures is that the legal framework in the respective country allows this and that supporting measures are in place to enable the implementation of a land leasehold reorganization procedure. The legal and the organizational framework conditions for both countries are therefore analyzed below.

3.2.1. Case of Ukraine

Leased Area

Until 1 July 2021, Ukraine’s moratorium on agricultural land sales made leasing the primary method for structuring land use and expanding agricultural enterprises (farms). This contributed to the rise of agricultural holdings. Among 6.9 mm private landowners, averaging 4.0 ha each, about 90% lease their land to agricultural enterprises. Currently, agricultural enterprises and farms lease 64% of the country’s agricultural land, 29% is cultivated directly by landowners, and 7% remain uncultivated []. Notably, as of 2018, 85% of lease agreements are with the enterprises from which landowners received their land shares [].

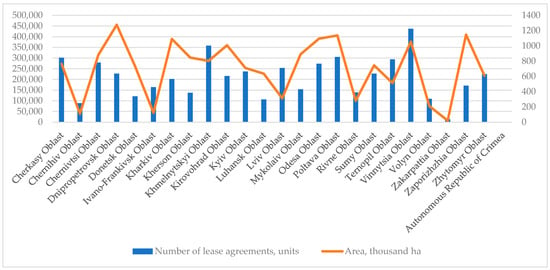

Despite land reforms, Ukraine’s agricultural sector continues to be dominated by large-scale enterprises operating on leased land. Agricultural enterprises have to manage thousands of lease agreements, with 5 million such agreements in 2019 covering 16.9 million hectares (Figure 1). Each agreement averaged 3.4 hectares, meaning 125 leases are required to secure 500 hectares []. Research indicates [] that 93% of agricultural enterprises’ land area comprises leased land. Currently, some extensive agricultural holdings control over 35% of the agricultural land in specific local communities through lease agreements, with land concentration in some cases exceeding 500,000 hectares.

Figure 1.

Number of Agricultural Land (for Commercial Farming) Lease Agreements by Administrative-Territorial Units of Ukraine. Source: prepared by the authors based on [].

Lease Price

The amount of rent for land plots owned by the state, municipal, and private property is set differently.

The rent for a privately owned agricultural land parcel is determined in the contract. Still, it must be at least 3% of the normative monetary valuation of the parcel, as stipulated by Presidential Decree No. 92 of 2 February 2002 []. The rent amount may be higher, depending on the agreement, and there is no single maximum rate for private land. The rent per hectare of leased private agricultural land is relatively low by European standards, averaging between €65 and €113 per hectare per year.

For state and municipal agricultural lands, the rent cannot be less than the land tax. It cannot exceed 12% of the normative monetary valuation of such a land parcel (except in the case of determining the lessee on a competitive basis, for example, at a land auction). It is worth noting that for specific categories (for example, for state-owned companies), a minimum rent rate of 12% of the normative monetary valuation is established. The rent for leasing state agricultural land at auctions can reach up to €614–819 per hectare per year and for municipal agricultural land is €199 per hectare per year, according to the “Prozorro.Sales” system.

Lease Term

The Law on Land Lease defines the minimum and maximum lease terms for land parcels []. For agricultural land used in commercial production, farming, or personal peasant farming, the lease term must be mutually agreed upon but cannot be less than 7 years, or at least 10 years for irrigated land. For land parcels used to plant or grow perennial crops (such as fruit, berry, nut, or grape plantations), the lease term must be at least 25 years. The maximum lease term for any agricultural land parcels is limited to 50 years [].

All land lease agreements must be registered in the State Register of Property Rights to Real Estate []. A lease agreement can only be concluded if the land parcel is registered in the State Land Cadaster.

3.2.2. Case of Germany

Leased Area

The proportion of leased land rose from 47% to 56% in the former federal territory during this period, falling from 90% to 67% in the new federal states []. The proportion of leased land is highest in the eastern federal states at around 77%, with an average leased area of around 154 ha per farm. In the northwestern German federal states with inheritance rights, the proportion of leased land is around 66% with an average leased area of around 60 ha per farm. In the southwestern German states with real division of inheritance rights, the proportion of leased land is only 64%, with an average leased area of approximately 34 ha per farm []. Due to the small-scale agricultural structure in the German states with real division of inheritance rights, the number of lease agreements per agricultural farm and ha is significantly higher than in the other two regions.

Lease Price

Lease prices for agricultural land also vary across Germany depending on the agricultural structure and the dominance of individual local lessees. The highest lease prices are achieved in federal states where the right of primogeniture dominates (2023: €480 to €560/ha per year), while lease prices in federal states with a small-scale agricultural structure, especially in southwestern Germany, depending on real division of property law, are significantly lower (2023: €207 to €290/ha per year) []. In the eastern federal states, lease prices range between €185 and €323/ha per year []. This indicates that local lessees are at least partially dominant and, despite the high productivity of the land, especially in Thuringia, are able to keep lease prices low due to a lack of competition.

Rental prices for agricultural land have risen by almost 40% in the last ten years [], while inflation-related price increases during this period were only around 20% []. The production costs of agricultural businesses have risen accordingly, which calls for more efficient management of agricultural land.

Lease Term

The relevant legal provisions governing agricultural lease agreements can be found in Sections 585 to 597 of the German Civil Code (BGB) []. Section 585 BGB stipulates that an agricultural lease agreement is deemed to exist if a plot of land with residential or farm buildings (farm) used for its cultivation or a plot of land without such buildings is leased predominantly for agricultural purposes. Agriculture is defined as land cultivation and animal husbandry associated with land use for the purpose of obtaining plant or animal products, as well as horticultural production. If agricultural lease agreements concluded for a period longer than two years are not agreed in writing, the agreement is valid for an indefinite period. Furthermore, information on the description of the leased property, the typical obligations and encumbrances of the contract, the lease maturity and measures for maintenance or improvement, as well as termination, are regulated.

In principle, contracting parties in Germany enjoy considerable freedom in terms of contract design. Only a few regulations apply, such as in the case of lease agreements with a term of more than 30 years. In such cases, either party may terminate the agreement within the statutory notice periods after 30 years.

While the provisions of the BGB set out the obligations and rights of landlords and lessees, the Land Lease Act [] regulates how and when the relevant land lease agreements must be reported to the competent authority and what measures the authority can take. The aim is to have land lease agreements reviewed by the authorities for

- an unhealthy distribution of land use, in particular an unhealthy accumulation of agricultural and forestry land,

- an uneconomical division of the use of spatially or economically connected plots of land, and

- an inappropriate ratio of lease to yield.

In Germany, there is no register that officially records all land lease agreements.

3.2.3. Comparative Analysis

The analysis of lease frameworks of agricultural land in Ukraine and Germany shows that leasing is becoming increasingly important in the management of agricultural land and the development of agricultural businesses in both countries.

In Ukraine, the predominance of leasing results primarily from the long-term moratorium on agricultural land sales, which transformed leasing into the only legally key tool for enlarging agricultural enterprises. Exceptionally high lease concentration characterizes contemporary land use in Ukraine. Over 60% of agricultural land is leased by agricultural enterprises and farms, with a situation where larger agroholdings often control more than one-third of the community’s total area in some regions.

In Germany, a relatively high share of leased land also exceeds 50%. However, it has formed under market-based conditions and within a functioning property market. Land leasing primarily serves to facilitate generational change and structural change in agriculture and to offset fewer ownership restrictions. Lessees are typically family farms or medium-sized businesses with a balanced ownership structure, often found in rural areas.

A comparison of the legal basis for lease agreements and thus for voluntary reorganizations of use based on lease agreements in Ukraine and Germany shows that both are based on private law, with the freedom of the contracting parties being more extensive in Germany. In Ukraine, there is an official register for lease agreements, whereas in Germany, almost all lease agreements are merely reviewed by the authorities without an official register being established on this basis. Information on existing lease agreements is therefore better documented in Ukraine.

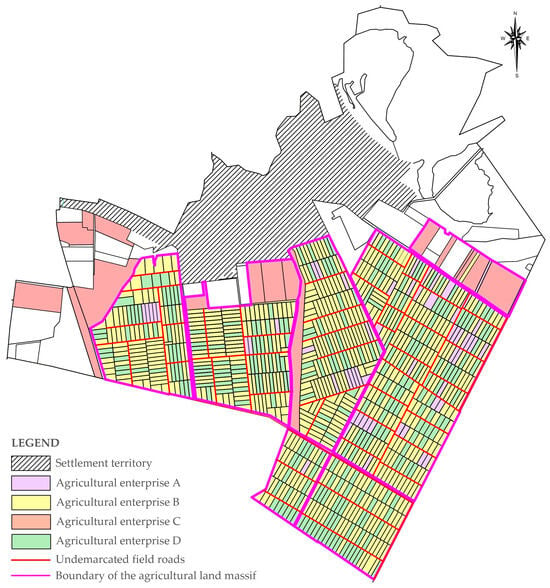

While in eastern Germany the local market dominance of individual private agricultural holdings, as successors to large state-owned agricultural enterprises, dominates the lease market, in Ukraine several of these agricultural holdings are active in the local real estate market, resulting in stronger competition. This results in large-scale farming structures with fragmented lease parcels (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Spatial Allocation of Leased Land Parcels among Agricultural Enterprises within Semenivska Territorial Community, Kremenchutskyi Raion, Poltavska oblast, Ukraine. Source: prepared by the authors.

The post-reform agricultural landscape of Ukraine is characterized by an anomalous combination of mass private ownership and operational concentration of land parcels through leasing, which creates a complex pattern of separate lease agreements, low lease prices, and mutual relations between landowners (lessors) and agricultural enterprises (lessees). Germany’s formation of agricultural structures is more historically rooted and regionally differentiated, resulting in higher lease rates, the dominance of medium-sized farms in many states, and a more developed land lease market.

The continuing rise in lease prices in Germany is forcing farmers to manage their land efficiently. Even though lease prices in Ukraine are significantly lower in absolute terms than in Germany in some cases, the top prices achieved at auctions show that there may be local demand that makes even high-priced consolidation economically viable.

The above results show that policy instruments such as land market regulation, lease law, auction mechanisms, taxation, and competition policy play an essential role in the efficient management of owned and leased land, and large-scale agricultural units ultimately make sense for every farm, which can be achieved by reorganizing ownership structures or lease rights.

3.3. The Significance of Land Leasing and Challenges

3.3.1. Case of Ukraine

There is no land consolidation procedure in Ukraine. Today, land leasing is the most accessible and well-established method of land concentration, enabling agricultural enterprises to efficiently and rapidly optimize the size of their landholdings. As a result, the average farm field size ranges from 50 to 200 hectares. The primary stakeholders and beneficiaries of land leasing are agribusinesses.

While land leasing offers advantages, excessive reliance on it has led to significant drawbacks for agricultural enterprises. A key issue is land use fragmentation within a single field, disrupting its integrity and creating logistical challenges. Fragmented parcels hinder the movement of agricultural machinery, complicate irrigation, and make managing large irrigated areas difficult. Such fragmentation also undermines the feasibility of constructing effective reclamation systems. Additionally, it provides opportunities for exploitation by unscrupulous landowners or users who impose artificial obstacles, enabling coercion, blackmail, or “raiding” to extract financial or material gains.

Another issue is the variation in lease terms across holdings, leading to a “patchwork” of leased parcels within the same field (Figure 2). This creates a situation where landowners and lessees effectively hinder each other from cultivating land within the same field. Not all landowners in a field typically lease their parcels to a single lessee, resulting in fragmented areas interspersed with parcels leased or owned by others. When multiple lessees operate in the same field, they may informally agree to divide it into sections proportional to their leased areas to form land parcels into a regular shape. While some agreements are formalized through mutual sublease contracts, this solution is limited by legal constraints. The Law on Land Lease requires landowner consent for subleasing, and not all landowners grant such permission. Moreover, sublease rights must undergo state registration, further complicating the process.

Another challenge in land use is the illegal cultivation of crops on field roads by agricultural enterprises. Field roads were designated to access individual land parcels during the land privatization process. However, these roads exist only on maps without formal documentation establishing (physical marking) them as community property (see Figure 2). These field roads cover approximately 500,000 ha across Ukraine. Additionally, accessing land parcels surrounded by leased land is often problematic. Field roads intended for access are frequently ploughed during agricultural activities, further complicating land use and management.

To address these issues, mainly to avoid land use fragmentation, legislative changes have been introduced to reorganize usage (lease) rights. These measures will be explored in Section 3.4.

3.3.2. Case of Germany

To promote rural development and, in particular, to implement land consolidation procedures in accordance with the Land Consolidation Act [], each federal state has established authorities responsible for implementing land consolidation procedures.

In addition, financial resources are made available under the Act on the Joint Task of Improving Agricultural Structures and Coastal Protection (GAK Act) [] to promote the implementation of rural development measures. This also includes the promotion of voluntary land lease reorganization if a federal state opens this promotion (e.g., Baden-Württemberg, Bavaria, Hesse, North Rhine-Westphalia and Rhineland-Palatinate). Financial supports are regularly approved by the land consolidation authority. They also advise farmers on initiating land exchange processes [,].

As a rule, subsidies are available for the services of a moderator to facilitate the negotiation process, as well as for costs incurred in connection with the implementation of the land lease exchange agreement (e.g., []).

In Germany, the expansion of agricultural holdings regularly takes place by leasing agricultural land from holdings that the owner no longer manages. Under German tax law, a distinction must be made between dormant and abandoned farms. In the case of a dormant farm, the leased farmland or a leased farm as a whole remains part of the business assets (Section 13 EStG). In contrast, land from abandoned farms is part of private assets (§ 21 EStG). While profits from the sale of agricultural land that is part of the business assets are taxable, income from the sale of privately owned land remains tax-free if it has been part of the owner’s private assets for more than 10 years [,]. If owners of agricultural businesses decide to privatize their agricultural assets, they are required, for tax reasons, not to sell their land for a period of at least 10 years. Therefore, owners of land that they no longer farm themselves will regularly lease rather than sell. In addition to the tax aspects, expectations regarding the value development of agricultural land play a role, be it cyclical changes in value due to changing supply or demand [], or qualitative changes in value if higher-value uses are permitted on agricultural land, e.g., for the generation of renewable energies through wind power and photovoltaic systems. Suppose there is a demand for agricultural land on the agricultural property market, and such land is offered for lease. In that case, an owner of an agricultural business is regularly found who concludes a corresponding lease agreement with the lessor on economically viable terms. This usually results in a fragmented structure of agricultural land on a farm with a high proportion of leased land. This increases the traveling and set-up times when cultivating this land. In this respect, the farm owner has a great interest in maintaining contiguous farmland, regardless of whether this land is owned or leased by him. In principle, it would make sense for the land owned by a farm and the leased land to form contiguous farming units. This could be achieved by reorganizing the ownership of owned and leased land through land consolidation in such a way that correspondingly large farming units are created. However, this only makes sense if it results in stable structures for the farming units formed in the long term. In practice, however, further concentration of agricultural businesses is to be expected, as the number of agricultural businesses with too little land for long-term economic viability is still high, and there is a lack of farm successors for many family farms. According to a study by the Thünen Institute, 30% of the farms surveyed have not yet decided on a farm succession or have already decided to give up the farm []. This will lead to a further increase in the leasing of agricultural land, meaning that stable farming structures will not yet emerge in the long term.

In order to create larger farming units, a reorganization can also be carried out by agreeing on corresponding lease contracts that ensure stable farming structures for the agreed contract term and enable an adjustment to situations that may have changed in the meantime at the end of the contract term. If the framing structures created by the contract are likely to be stable in the long term, a reorganization of the ownership structure through a corresponding land consolidation procedure can also secure this.

In order to halt the decline in biodiversity in rural areas and increase biodiversity, the European Union [] aims to place 30% of land and marine areas across Europe under legally binding protection by 2030, 10 per cent of which will be under strict protection, i.e., without human intervention. Germany fulfills 27% of these requirements in the area of under legally binding protection (as of 31 December 2019, []) and 6.5% in the area of strictly protected areas (as of 31 December 2019, []). Above all, Germany has some catching up to do, as the actual effectiveness of many existing protected areas has not been conclusively proven. Therefore, Germany is striving for more ecologically orientated land use, e.g., in the field of organic farming. To this end, some of the land that was previously used intensively for agriculture is to be farmed only extensively in the future, and a certain proportion of agricultural land is to be taken out of cultivation altogether, at least temporarily.

3.3.3. Comparative Analysis

Since Ukraine does not yet have a law on land consolidation and therefore no administrative structures for its implementation, unlike in Germany, there is a lack of support for farmers in terms of both advice and funding to optimize the size of their landholdings. The Ukrainian land-use pattern is marked by significant intra-field fragmentation (so-called “patchwork” effect) where multiple lessees and owners operate within the same field. Such fragmentation arises from the lack of coordinated actions regarding the conclusion of lease agreements and the absence of a land consolidation framework. Informal, voluntary arrangements between lessees sometimes mitigate land use fragmentation, but they lack legal certainty and long-term stability. As a result, this produced administrative burdens [] (many small leases per agricultural enterprise) and potential governance issues (dominant agricultural holdings controlling a huge amount of land parcels locally by lease rather than ownership).

In contrast, Germany’s system benefits from a mature institutional environment in which formal land consolidation procedures and spatial planning instruments complement lease relations. Although land leasing is widespread, land fragmentation is being reduced through processes of voluntary reallotment and land consolidation. Consequently, German agricultural structures have better territorial integrity and operational efficiency than those in Ukraine. Germany’s well-developed land market, differentiated regional institutions (inheritance regimes), and stronger local lease markets produce clearer price signals and a more consolidated leasing market, albeit with their own risks, such as the decline of family farms and succession gaps in many states.

While both countries rely on leases, which are generally long-term and legally secure, their structural consequences differ. The Ukrainian approach to agricultural land leasing has facilitated the rapid growth of the agricultural sector at the expense of land fragmentation and instability in land use. On the other hand, the German model provides stronger legal procedures that support spatial integrity and guarantee long-term land-use stability, although being more expensive for lessees due to high land rentals. Furthermore, the German framework increasingly integrates environmental objectives into land management, aligning lease structures with the European Union’s biodiversity and climate goals.

3.4. Approaches to the Land Lease Reorganization in Ukraine and Germany

In order to draw the necessary conclusions for the further development of the land lease reorganization procedures, this chapter analyses the legal basis in both countries with regard to the lease agreement procedures to be able to draw conclusions from this in Section 5.

3.4.1. Case of Ukraine

The land lease reorganization is permitted only within the boundaries of a designated agricultural land massif and only after its registration in the State Land Cadaster []. The agricultural land massif is a set of agricultural and non-agricultural land parcels (such as land for field roads, reclamation systems, linear objects, engineering infrastructure facilities, wetlands, other lands located within the land massifs), which have common boundaries and are limited by natural and/or artificial elements of a landscape (e.g., public roads, shelterbelts and other protective plantations, water bodies, etc.). Figure 2 illustrates the possible boundaries of the agricultural land massif, providing a clearer visualization of this specific land unit. The determination of boundaries, formation, and registration of an agricultural land massif in the State Land Cadaster is carried out by the land surveyor. It is worth noting that after the formation of such massif and its registration in the State Land Cadaster, the land surveyor does not participate in the land lease reorganization. Forming an agricultural land massif establishes legal grounds for land parcels designated as field roads (excluding those surrounding the massif) by landowners and lessees. These parcels may be utilized under lease agreements to access other land parcels within the massif and to cultivate agricultural products.

Owners and lessees of agricultural land parcels are legally allowed to exchange usage rights for the period of validity of the lease agreement if the parcels are located within the same agricultural land massif. This exchange is carried out through the mutual conclusion of lease or sublease agreements for the respective land parcels []. The conclusion of a sublease agreement does not require the lessor’s consent (landowner). However, the lessee remains responsible to the lessor for fulfilling the terms of the original lease agreement. If either the lease or sublease agreement for a land parcel exchanged under this arrangement is terminated, the corresponding agreement concluded in exchange is also terminated. This condition must be explicitly specified in both agreements.

It should be noted that in the case at hand, the conclusion of such agreements is a right, not a duty, for the landowners or lessees of the land parcels. If the parties disagree on the exchange of usage rights or if a lessee cannot reach an agreement with the landowner to conclude a lease, the interested party in reorganizing the lease agreement cannot compel them to do so, even with court intervention.

Lessees of land parcels are required to notify lessors in writing (via registered mail) about the exchange of usage rights for the land parcels following the state registration of the sublease agreement. The written notification must include the cadastral number of the land parcel, the duration of the sublease agreement, and the identity of the individual or entity to whom the land parcel was subleased.

The use of this approach to land lease reorganization is unlikely to be effective. This is primarily because the process for exchanging the usage (lease) rights is decentralized and inconsistent. The exchange of lease rights to reorganize lease agreements is conducted without considering the interests of other landowners and land users (lessees). As a result, while the initiators resolve their own land fragmentation issues through sublease agreements, they simultaneously risk creating new land use fragmentation challenges for other landowners or lessees.

A more favorable approach to reorganizing leased land occurs when a dominant land user initiates the process. A dominant land user is an individual or entity who holds lease rights for land parcels located within a single agricultural land massif, with a total area comprising at least 75% of the entire massif. A dominant land user has the right to lease agricultural land parcels from other owners located within the agricultural land massif. If these parcels are already under lease, the dominant land user may sublease them, provided that the original lessee is offered a comparable land parcel within the same massif under the same terms and for the same duration. Such an arrangement is permitted when the farmland patchwork hinders the rational use of the land parcels already managed by the dominant land user. According to the Law of Ukraine “On Land-Use Planning”, a farmland patchwork (a checkerboard) refers to the arrangement within a single agricultural land massif where land parcels owned or used (through ownership, lease, sublease, or emphyteusis) by one person are interspersed with land parcels owned or used (through ownership, lease, sublease, or emphyteusis) by another person [].

If another party proposes entering into a lease agreement for the same land parcel during the reorganization of leased land, the dominant land user (excluding those with a pre-emptive right to renew the lease agreement) has a priority right to conclude a lease agreement under terms no less favorable than those offered to the other party.

The dominant land user’s right to lease (or sublease) land parcels through an exchange of usage rights for another land parcel may be exercised under the following conditions:

- Equivalent Rent: The rent or sublease payments must align with the terms of the land exchange agreement.

- No Pre-emptive Purchase Right: The lessee does not have the first refusal right to purchase the leased land parcel.

- No Compensation for Improvements: The lessee or sublessee does not have the right to claim compensation for any improvements made to the leased land.

- No Automatic Lease Renewal: The lease or sublease cannot be automatically renewed if the other party objects.

- Access to Land: If the exchanged land parcel lacks direct access from the agricultural land massif’s edge, the dominant land user must grant free-of-charge access to such land parcel.

- Connected Land Parcels: If multiple land parcels belonging to the same person are leased or subleased to the dominant land user, the exchanged land parcels must share a common boundary.

The owner or user of a land parcel, whose land is leased or subleased to the dominant land user, is entitled to full compensation for any property damage resulting from this transfer. The amount of compensation is determined through a formal assessment process. As the initiator of the land lease reorganization, the dominant land user is responsible for selecting the appraiser and covering the associated costs. If the landowner or user disagrees with the initial assessment, they can commission a second assessment at their own expense.

To initiate the conclusion of a lease (sublease) agreement for the exchange of land use rights, the dominant land user must submit a written proposal to the other party. This proposal must include the following information:

- A description of the land parcels proposed for exchanging use rights, including cadastral numbers, area, location, and their normative monetary valuation.

- The amount of property damage, if any, caused to the owners or users of the land parcels as a result of the exchange of usage rights.

- The draft of the proposed lease (sublease) agreement and a draft lease (sublease) agreement for the land parcel whose usage rights are offered in exchange.

- A certified copy of the lease agreement for the land parcel operated by the dominant land user whose usage rights are proposed for transfer in the exchange.

The potential owner or lessee of the land parcel must review the proposal and either sign the agreement or provide a written explanation for their refusal within one month of receiving it.

In practice, the limited adoption of the “dominant land user” mechanism can be attributed to a combination of legal, institutional, and procedural deficiencies that have hindered its effective implementation. As demonstrated in studies [,], the law lacks clear rules for initiating and forming an agricultural land massif, fails to define the competent authorities, and does not specify who may act as the initiator of such a procedure when several owners or users are involved. The bureaucratic complexity of obtaining the status of a dominant land user, the absence of transparent procedures for stakeholder participation and appeal, and the conflict of interest in the appraisal of damages have further undermined confidence in the process. Moreover, the threshold of 75% control over agricultural land massif grants disproportionate power to large leaseholders and contradicts constitutional guarantees of equal property rights. The lack of mechanisms for environmental responsibility and coordination among landowners and land users has rendered the instrument practically inoperative. As a result, despite initial expectations, only one agricultural land massif in Ukraine was formed []. However, the results of the lease reorganization remain unknown. All this confirms that the “dominant land user” mechanism remains a formally accepted yet ineffective alternative to land consolidation.

3.4.2. Case of Germany

In Germany, there are currently no statutory regulations that enable the land lease reorganization under public law, such as the reorganization of ownership relationships through land consolidation procedures. Rather, only the provisions of the German Civil Code are available for the reorganization of tenancies. Therefore, a reorganization of agricultural tenancies is only possible by means of contracts under private law, which require the consent of all owners and lessees affected by the contract. In individual federal states, e.g., Bavaria, Hesse, and Rhineland-Palatinate, owners and lessees can receive substantive and financial support if they seek to reorganize leases under private law [,]. The prerequisite for successful implementation is the voluntary signing of the negotiated contract by all parties involved. If the consent of the owners and lessees concerned can only be obtained for a smaller area, a corresponding land lease reorganization can only take place there.

The aim of the negotiations for a land lease reorganization is to reach a joint agreement that establishes new lease agreements to create better-managed farming units for all farms. To this end, the area in which the exchange of leased land is to take place (exchange area) must first be provisionally defined. A draft exchange concept must then be drawn up. Suppose municipal field roads will continue to be used as agricultural land. In that case, the municipality as the owner of the field roads must also be involved in the exchange concept and the subsequent negotiations. In individual cases, the farm owner can also lease land he owns to another farmer and, in return, lease land from another owner. All owners and lessees of agricultural land in the exchange area must negotiate the draft exchange concept until an amicable solution is found or the negotiations are broken off because no solution can be reached, not even for part of the exchange area. In principle, it is helpful if an external and independent expert drafts the exchange concept and coordinates and manages the negotiations. This means that the process is organized neutrally due to the lack of personal involvement of the external expert and the lack of dependence on a client in the form of an individual or group of owners.

If an amicable solution is reached, either new individual lease agreements are concluded between the owner and lessee of each exchange area or a collective lease agreement summarizing all individual lease agreements is signed by all owners and lessees. All lease agreements must contain provisions on a common start date for all lease agreements, the same term (e.g., 10 years), and the rent. The latter can differ depending on the quality and usability of the leased land [].

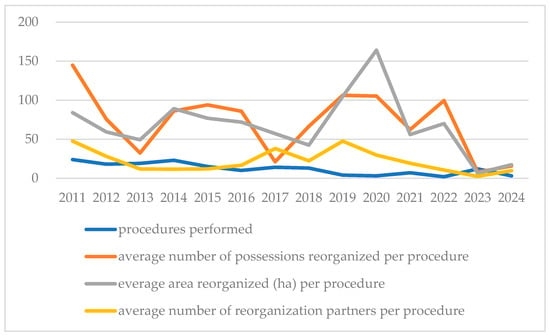

The number of successful private law proceedings for the reorganization of lease agreements with state support, as described in Section 3.2.2, are recorded statistically (Figure 3). The following are not included in the statistics:

Figure 3.

Voluntary processes of reorganizing lease agreements in Germany 2011–2024. Source: prepared by the authors, data: bmel-statistik.de.

- unsuccessful private law processes for the reorganization of lease agreements with state support,

- successful private law processes for the reorganization of lease agreements without state support, and

- unsuccessful private law processes for the reorganization of lease agreements without state support.

- Therefore, no reliable data can be evaluated for these cases. In this case, only the empirical values of experts can be used [interviews 29 October 2025, 5 November].

The development of private law processes for the reorganization of lease agreements with state support, which have been successfully implemented since 2011, shows that the number of processes has decreased during this period in general. The nature of the proceedings varies in terms of the number of possessions, the area and the partners involved in the process. In individual years, e.g., 2020, only 3 proceedings were successfully implemented, but these involved an average of 105 properties, 164 ha of land and 30 owners and lessees. In 2023, on the other hand, 12 processes were implemented, but these involved an average of only 8 properties, 7 hectares of land, and 3 owners and lessees. Experts [interviews–29 October 2025, 5 November 2025)] confirm that the number of voluntary land lease reorganization processes supported by the state has declined significantly.

The factors that promote the process of voluntary lease reorganization and the obstacles that prevent landowners and lessees from reaching agreement are of crucial importance for the further development of this instrument. To identify these, the results of a research project conducted in Hesse in 2006 are used below and validated based on expert interviews.

In this research project [,], eleven land lease exchange procedures were monitored in central Hesse in 2006, seven of which were successfully implemented. The successful schemes were implemented over a period of 3 to 8 months. Sixty percent of the farmers based there took part. Five hundred and nine fields covering an area of 253 hectares were exchanged, reducing the number of fields by 12% and almost doubling the size of the cultivated area. Further analysis of the successful lease exchange procedures showed that the financial costs of the land lease exchange procedures had been recouped within two years. The economic benefits resulted from a reduction in farm-field machinery costs, farm-field time requirements, machinery costs, and time requirements, as well as an increase in yield due to fewer field margins.

This research project [,] identified the following boundary conditions as necessary for the successful implementation of a land lease exchange procedure: the involvement of a moderator, the visualization of the current situation and possible exchange results, and legal knowledge for the drafting of legally secure lease contracts. The moderator must take a neutral position and not become actively involved in planning. It was also important to agree on rules of conduct within the group of exchanging farmers in order to ensure respectful interaction at all times and to strengthen group cohesion.

If owners and lessees cannot reach an agreement, even for part of the exchange area, the reorganization of the lease agreement fails. The reasons why individual owners and lessees are unwilling to cooperate can be very complex. This begins when there are economic disadvantages for individual parties because, for example, they have invested to increase the yield on the previously farmed land that was not made on the exchange land intended for the affected party. In such a case, financial compensation may have to be paid. It ends with subjective personal reasons of an affected person or individual affected persons that lead to a complete refusal to cooperate, or can only be eliminated by fulfilling unjustified demands.

The same research project [,] also analyzed the four failed land lease exchange procedures with regard to the reasons for their failure. In two cases, the land lease exchange procedures failed due to conflicts between group members. In another procedure, a large proportion of the farmers wanted to cease operations in the coming years due to their age, which would have significantly changed the lease structure in the area. In the fourth scheme, the mixing of conventionally and organically farmed land prevented the exchange of land.

In principle, amicable solutions agreed upon by farmers regarding new land lease structures should take precedence over official proceedings. However, this often results in small and potentially spatially disconnected solutions. An official procedure could be helpful here, initiating a lease exchange procedure for a specified area in which the interests of the individual and the common good are weighed fairly against each other []. In the event that the interests of the common good are to be given priority, e.g., because the implementation of the reorganization of the lease agreements can achieve an important improvement in the agricultural structure, while the non-cooperative party does not suffer any economic damage, the reorganization of the lease agreements could also be implemented against the will of individual affected parties.

To validate the above findings with regard to their continued validity and, if necessary, to identify new success factors and obstacles, semi-structured interviews were conducted with experts from several federal states. These interviews [29 October 2025 and 6 November 2025] confirmed the above findings and identified the following additional possible obstacles:

- demands by nature conservation authorities for compensation under nature conservation law if the formation of larger management units results in the loss of areas that have previously been farmed less intensively (e.g., fenced areas used for grassland or dirt roads used for arable farming). It should be noted that in the case of successful private law processes for the reorganization of lease agreements without state support, such a demand by the nature conservation authority is not possible. Therefore, it may be that more processes are implemented without state support,

- non-agricultural uses, especially to produce renewable energies, i.e., wind turbines and photovoltaic systems, limit the willingness to conclude long-term lease agreements. This affects larger regions in cases where the locations to produce renewable energies have not yet been determined. In this way, landowners want to minimize the risk of not being able to lease their land to renewable energy plant operators at significantly higher lease prices if necessary.

3.4.3. Comparative Analysis

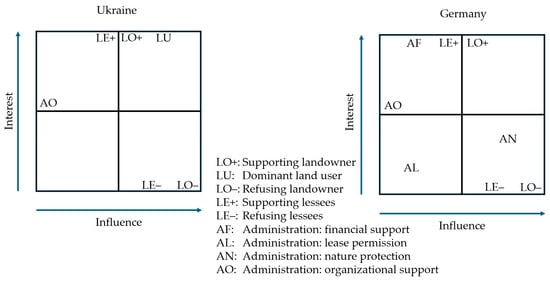

A comparison of the application of the land lease reorganization instrument in Ukraine and Germany shows that the successful application of the instrument in practice depends on many influencing factors. However, the influence that individual stakeholders can exert on the decision-making process ultimately determines its successful use. A stakeholder analysis (Figure 4) is used to compare the influence of individual stakeholders to draw conclusions for the further development of the instrument.

Figure 4.

Stakeholder analysis of the current land lease reorganization procedures in Ukraine and Germany. Source: prepared by the authors.

The key stakeholders in the decision-making process for implementing a land lease reorganization are primarily the landowners (LO) and the lessees (LE). Landowners have greater influence than lessees, as they can generally terminate lease agreements if, for example, better income opportunities arise for them. Each of these two groups can be further divided into those who are willing to participate in the land lease reorganization (LO+, LE+) and those who are not willing to participate (LO−, LE−). Only in Ukraine is there a dominant land user (LU) who, if the legal requirements are met, can force a land lease reorganization procedure.

In addition to landowners and lessees, various authorities can also influence the decision-making process. These include authorities that must approve lease agreements (AL). Their approval is guaranteed if the legal requirements are met. In both countries, there are also authorities that provide data and other non-financial support for such a land lease reorganization (AO), thereby supporting the decision-making process. Only in Germany is there an authority that provides state subsidies for a land lease reorganization (AF), thereby creating an incentive to participate. In addition, only in Germany are the nature conservation authorities (AN) involved, which can impose additional requirements for restructuring leased land, meaning that owners and lessees forego state subsidies to avoid additional costs.

The stakeholder analysis presented above shows that individual landowners or lessees whose properties play a central role in a possible land lease reorganization process and who, for whatever reason, are unwilling to cooperate, have a decisive influence on the outcome of the decision-making process (LO−, LE−). Landowners and lessees who are willing to participate (LO+, LE+) can therefore only develop solutions that are possible without the participation of landowners and lessees who are unwilling to participate. It is generally not possible to influence the latter landowners and lessees to participate. The only exception to this is the dominant land user in Ukraine, although the legal requirements are rarely met, and the process of enforcing rights is lengthy (Section 3.4.1).

The authorities tend to play a subordinate, mostly supportive role in the land lease reorganization process.

The following conclusion can be drawn from the above: First, legislators must decide whether they attach greater importance to the common good than to individual interests. The common good is primarily determined by improved agricultural structural use through land lease reorganization. However, other objectives of the common good can also be pursued, such as improving the ecological situation. Relevant experience has been gained over many decades with the land consolidation procedure and the reallocation of building land in Germany, which are then initiated ex officio and carried out by the authorities if private law solutions cannot be reached by mutual agreement between the landowners and there is a public interest in carrying out the procedure. The historical development of both instruments has shown that majority approval by landowners as a prerequisite for implementing an official procedure was not effective [].

4. Discussion

In Ukraine, some agricultural land is no longer available for cultivation due to the effects of the Russian war of aggression. In many cases, it will not be possible to repair war-related damage in the short term, meaning that agricultural land will not be available for farming in the medium to long term. If Ukraine joins the European Union in the long term, biodiversity will have to be given a higher priority there too, and organic farming will gain in importance.

As a result, less agricultural land will be available in both countries in the future. In this respect, the challenges in managing leased land for efficient and ecologically oriented agricultural use are very similar in both countries.

This means that both countries will have to deal with a high proportion of leased land in the future and use instruments that enable the sustainable management of agricultural land from an economic, ecological and social perspective. This will not be possible without resolving existing land use conflicts, which typically require a reorganization of ownership and property relations. A land lease reorganization can achieve solutions that can be implemented in the short term and adapted to the new situation with relatively little effort in the event of very dynamic changes in land use.

The description of the current legal situation in Ukraine and Germany with regard to land lease reorganization shows that this is primarily based on consensual private law solutions between owners and leaseholders, which as a rule cannot be achieved or can only be achieved to a limited extent.

In Ukraine, the reliance on a high threshold (75% control for dominant users) and the voluntary nature of exchanges, often lacking coordination and potentially creating new fragmentation elsewhere, demonstrate that current mechanisms fall short of providing a systematic solution comparable to land consolidation. The procedures are complex and, as noted, not widely adopted, suggesting practical hurdles or insufficient incentives. Due to the critical lack of a formal public lead system of land consolidation, land lease reorganization is a potentially useful but ultimately incomplete tool. This makes it particularly inadequate for addressing the creation of sustainable agrarian structures and the systemic challenges of post-war reconstruction that require coordinated interventions at the landscape level.

In contrast, Germany operates within the existing system of land consolidation, using voluntary land lease reorganization as a less mandatory and perhaps faster method that finds support in several federal states. However, the German experience clearly highlights a fundamental problem inherent in any voluntary, contractual approach: the possibility of failure due to the lack of consent of even one of the parties. Even with external moderation, the land lease reorganization process remains vulnerable to individual economic considerations, subjective perceptions of disadvantages (such as uncompensated investments), or personal motives, which prevent achieving optimal structural outcomes for collective (common) benefit. While proposals to integrate environmental objectives into land lease reorganization in Germany reflect a progressive vision of land multifunctionality, the mechanism’s effectiveness still depends on unanimous consent.

The research results indicate that the land lease reorganization, while providing localized improvements and a practical adaptation to the land tenure situation, cannot be a complete substitute for formal land consolidation with its comprehensive, legally binding, and spatially coordinated approach. The key difference is that the reorganization of land leases addresses use rights temporarily, while consolidation fundamentally restructures ownership rights, ensuring long-term structural land changes. Despite conceptual innovations (in particular, the dominant user right), the Ukrainian mechanisms for land lease reorganization appear insufficient to effectively overcome systemic land fragmentation or systematically address the post-war period’s challenges. While the German approach may be successful in specific situations where there is consensus, it does not have the binding force necessary to overcome obstacles in the public interest.