Titling as Land Reform in Tanzania: Contours, Conflicts and Convergence

Abstract

1. Introduction: Land Titling as Land Reform

- Village Land: Land in registered villages under the jurisdiction of elected village councils;

- Reserved Land: Land protected for conservation purposes and spanning numerous categories (e.g., national parks, game reserves, wildlife management areas, forest reserves, water sources), administered by the relevant authority (e.g., national parks fall under the jurisdiction of the Tanzania National Parks Authority, TANAPA, while forests are managed by the Tanzania Forest Services, TFS);

- General Land: All public land which is not reserved land or village land, generally including urban settlements, infrastructure and public utilities, and large-scale (>50 acres) investments in rural areas.

2. Methods

3. Plurality of Titling Initiatives

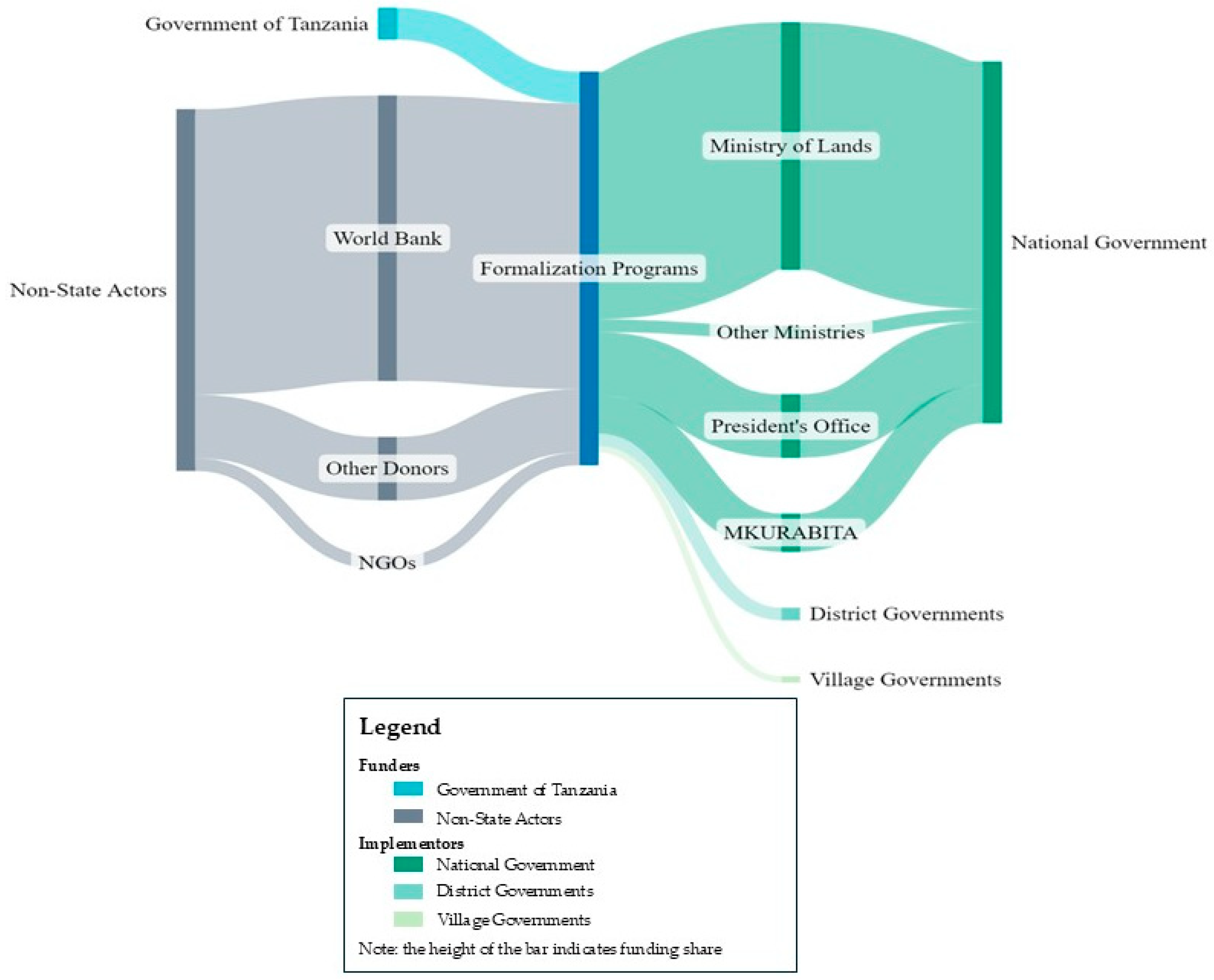

3.1. Plural Actors: State and Non-State Institutions

3.2. Plural Programs, Procedures and Technologies

3.3. Plural Motivations

- Titling can increase the security of tenure by:

- Offering protection against potential land-grabbing;

- Improving agricultural productivity as it has been argued that low agricultural productivity is a consequence of tenure insecurity.

- Titling can reduce conflict by:

- Clarifying ownership and boundaries.

- Titling can alleviate poverty by:

- Securing the livelihoods of those who depend on land for subsistence;

- Facilitating access to credit thereby enabling smallholders to launch new business activities or secure capital to further their agricultural activities.

- Titling can secure land rights for vulnerable groups including:

- Women as a means of female empowerment;

- Pastoralists and other Indigenous communities as a means to sustain their traditional ways of life.

- Titling can improve land market efficiencies by:

- Facilitating sales and transfers;

- Identifying land available for land-based investment.

- Titling can improve government’s functions and finances by:

- Providing access to information about land ownership and land planning, thereby improving land administration;

- Providing increased transparency as to who owns what and where, thereby improving governance over land;

- Expanding the tax base so that the GoT may decrease its reliance on donor aid and loans and be more accountable to its citizens.

- Titling can protect the environment by:

- Protecting natural resources from degradation and destruction, including water sources, wildlife, and environmental resources (ecological, vegetation, forests, marine);

- Mitigating the effects of climate change by conserving forests and green spaces.

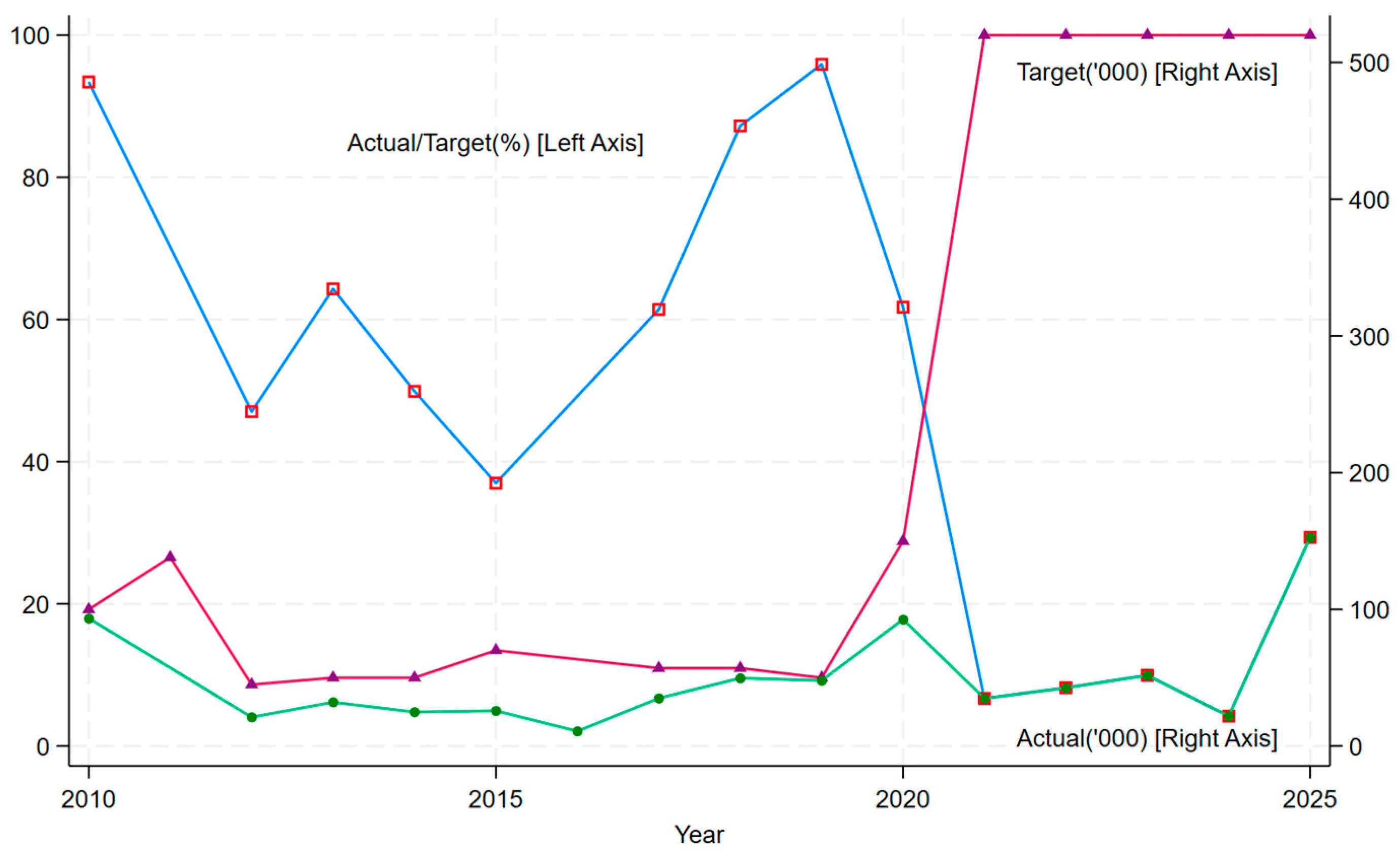

3.4. Plurality in Achievements

4. Tenuity of Titling Outcomes and the Rural Landowner

4.1. Security of Tenure for Whom, and at What Cost?

4.2. Impact of Formalization on Insecurity and Conflict

4.3. Formalization and Poverty Alleviation

4.4. Titling and Protecting Women’s and Pastoralists’ Rights to Land

4.5. Formalization’s Opportunity Costs

5. Conclusions

Contrary to the simple notions of aid agencies that see ‘insecurity of land tenure’ and ‘lack of clarity of property rights’ as the obstacles to increased production and to ‘development’ more broadly, the vast majority of rural producers in Africa are stymied by the loss of government-subsidized and managed programs of input delivery, credit, and other extension and market services, and by the overwhelming inequality faced by most African products in world markets…. ‘property rights’ to land without the means to use land productively is “a sick joke… because they lack the basic capital resources, and their social rights are being whittled away all the time” [22].

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Name of Organization | Acronym | NGO | Govt/Donor | Company |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| African Wildlife Foundation | AWF | 1 | ||

| Agricultural Non-State Actors Forum | ANSAF | 1 | ||

| Ardhi Institute Morogoro | ARIMO | 1 | ||

| Belgian Development Agency (formerly Belgian Technical Cooperation) | ENABEL | 1 | ||

| CARE International | CARE | 1 | ||

| Center for International Forestry Research | CIFOR | 1 | ||

| Commonwealth Forestry Association | CFA | 1 | ||

| Community Research and Development Services | CORDS | 1 | ||

| CONCERN Worldwide | CONCERN | 1 | ||

| Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research | CGIAR | 1 | ||

| Development Associates International | DAI | 1 | 1 | |

| Danish International Development Agency | DANIDA | 1 | ||

| Dodoma Environmental Network | DONET | 1 | ||

| Dorobo Safaris | 1 | 1 | ||

| Eastern Africa Land Administration Network | EALAN | 1 | ||

| Eco Village Adaptation to Climate Change in Central Tanzania | EcoACT | 1 | ||

| Economic and Social Research Foundation of Tanzania | ESRF | 1 | ||

| Environment for Development | EfD | 1 | ||

| European Union | EU | 1 | ||

| Food and Agricultural Research Management | FARM Africa | 1 | ||

| Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office (formerly DFID) (UK) | FCDO | 1 | ||

| Foundation for Civil Society | FCS | 1 | ||

| Global Water Initiative—East Africa | GWI | 1 | ||

| Great Lakes of Africa Centre, University of Antwerp | GLAC | 1 | ||

| HakiMadini | 1 | |||

| Illovo Sugar Africa | 1 | |||

| International Food Policy Research Institute | IFPRI | 1 | ||

| International Fund for Agricultural Development | IFAD | 1 | ||

| International Union for Conservation of Nature | IUCN | 1 | ||

| Journal of Land Administration in Eastern Africa | JLAEA | 1 | ||

| Kibaya, Kimana, Njoro, Ndaleta, Namelock, and Partimbo Development Program | KINNAPA | 1 | ||

| Kigoma Sugar | 1 | |||

| Land Equity International | 1 | |||

| Land Portal Foundation | 1 | |||

| Land Rights Research and Resources Institute | HAKIARDHI | 1 | ||

| Landscape Conservation in Western Tanzania (assoc w/Jane Goodall Institute) | LCWT | 1 | ||

| Lawyers’ Environmental Action Team | LEAT | 1 | ||

| Legal and Human Rights Centre | LHRC | 1 | ||

| Maasai Women Development Association | MWEDO | 1 | ||

| Mpango wa Kurasimisha Rasilimali na Biashara za Wanyonge Tanzania | MKURABITA | 1 | ||

| Mtandao wa Vikundi vya Wakulima Tanzania | MVIWATA | 1 | ||

| National Land Forum | NALAF | 1 | ||

| Nature Conservancy | 1 | |||

| Nile Basin Initiative | NBI | 1 | ||

| Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation | NORAD | 1 | ||

| Oxfam International | OXFAM | 1 | ||

| Parakuiyo Pastoralists Indigenous Community Development Organisation | PAICODEO | 1 | ||

| Pastoral Women’s Council | 1 | |||

| Pastoralists Indigenous Non-Governmental Organizations Forum | PINGO’s Forum | 1 | ||

| Pastoralists’ Survival Options | NAADUTARO | 1 | ||

| PELUM Association Tanzania | PELUM | 1 | ||

| Regional Strategic Analysis and Knowledge Support Systems | ReSAKSS | 1 | ||

| Research on Poverty Alleviation | REPOA | 1 | ||

| Resource Conflict Institute | RECONCILE | 1 | ||

| Resource Equity | 1 | |||

| Rift Valley Institute | RVI | 1 | ||

| Royal Danish Embassy of Tanzania | 1 | |||

| Netherlands Development Organization | SNV | 1 | ||

| Southern African Development Community | SADC | 1 | ||

| Southern African Legal Information Institute | SAFLII | 1 | ||

| Southern Agricultural Growth Corridor of Tanzania | SAGCOT | 1 | ||

| Swedish International Development Agency | SIDA | 1 | ||

| Swiss Development Cooperation Program | SDC | 1 | ||

| Tanzania Gender Networking Program | TGNP | 1 | ||

| Tanzania Land Alliance | TALA | 1 | ||

| Tanzania National Parks Authority | TANAPA | 1 | ||

| Tanzania Natural Resource Forum | TNRF | 1 | ||

| Tanzania Women Lawyers Association | TAWLA | 1 | ||

| Tanzanian Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries | MALF | 1 | ||

| Tanzanian Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements Development | 1 | |||

| Ujamaa Community Resource Team | UCRT | 1 | ||

| United States Agency for International Development | USAID | 1 | ||

| University of Dar es Salaam | UDSM | 1 | ||

| Vétérinaires Sans Frontières Belgium | VSF Belgium | 1 | ||

| Wildlife Conservation Society | WCS | 1 | ||

| Women’s Land Tenure Security | WOLTS | 1 | ||

| Women’s Legal Aid Centre | WLAC | 1 | ||

| World Bank | WB | 1 | ||

| World Wildlife Fund | WWF | 1 | ||

| Totals | 53 | 22 | 6 |

| Start Year | Project | Source | Source Type | Total Amount (USD) | Est Amount on Land Reform |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | Land Management Programme (LAMP) | SIDA | Bi-Lateral Donor | 16,874,520 | 14,278,440 |

| 2002 | Mbozi Pilot Project | EU | Bi-Lateral Donor | 1,000,000 | 1,000,000 |

| 2004 | MKURABITA | Norway | Bi-Lateral Donor | 7,000,000 | 7,000,000 |

| 2005 | Private Sector Competitiveness Project (PSCP) 1 | World Bank | Multi-Lateral Donor | 22,500,000 | 18,000,000 |

| 2005 | PSCP 1 | World Bank | Multi-Lateral Donor | 4,000,000 | 3,200,000 |

| 2005 | PSCP 1 | World Bank | Multi-Lateral Donor | 17,500,000 | 14,000,000 |

| 2005 | Rights-Based Programme | Concern | NGO | 3,602,808 | 3,602,808 |

| 2007 | MKURABITA | URT | Government | 10,000,000 | 10,000,000 |

| 2007 | MKURABITA | URT | Government | 4,191,200 | 4,191,200 |

| 2012 | Agricultural Sector Development Programme | IFAD | Multi-Lateral Donor | 2,370,000 | 2,370,000 |

| 2009 | MKURABITA | URT | Government | 2,508,000 | 2,508,000 |

| 2010 | MKURABITA | URT | Government | 4,536,000 | 4,536,000 |

| 2010 | Sustainable Management of Land and Environment, SMOLE, II | Finland | Bi-Lateral Donor | 11,946,474 | 9,557,179 |

| 2010 | Lindi and Mtwara Agribusiness Support project LIMAS | Finland | Bi-Lateral Donor | 9,982,980 | 1,996,596 |

| 2011 | MKURABITA | URT | Government | 4,500,000 | 4,500,000 |

| 2011 | Land and Natural Resources Tenure Security Learning Initiative | IFAD | Multi-Lateral Donor | 300,000 | 300,000 |

| 2012 | SERA Project | USAID | Bi-Lateral Donor | 1,500,000 | 1,500,000 |

| 2013 | PSCP 2 | World Bank | Multi-Lateral Donor | 35,000,000 | 35,000,000 |

| 2013 | PSCP 2 | World Bank | Multi-Lateral Donor | 15,000,000 | 15,000,000 |

| 2013 | PSCP 2 | World Bank | Multi-Lateral Donor | 10,500,000 | 10,500,000 |

| 2013 | Land Transparency Partnership | DFID | Bi-Lateral Donor | 8,200,000 | 8,200,000 |

| 2014 | Mobile App | USAID | Bi-Lateral Donor | 1,000,000 | 1,000,000 |

| 2014 | Mobile Pilot | USAID | Bi-Lateral Donor | 1,000,000 | 1,000,000 |

| 2015 | Land Tenure Assistance | USAID | Bi-Lateral Donor | 6,000,000 | 6,000,000 |

| 2016 | Land Tenure Support Program | DANIDA/SIDA/DFID/NORAD | Bi-Lateral Donor | 10,484,779 | 10,484,779 |

| 2021 | Land Tenure Improvement Program | World Bank | Multi-Lateral Donor | 150,000,000 | 150,000,000 |

| Total Funding | USD 339,725,002 | ||||

| Year | Villages | CCROS (Ministry) | CCROS (LSTP) | CCROS (LTIP) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Target | Actual | Target | Actual | Target | Actual | |

| 2005/06 | 1262 | ||||||

| 2006/07 | 3940 | ||||||

| 2007/08 | 8815 | ||||||

| 2008/09 | 11,000 | 20,512 | |||||

| 2009/10 | 11,000 | 100,000 | 93,400 | ||||

| 2010/11 | 138,000 | ||||||

| 2011/12 | 11,817 | 45,000 | 21,169 | ||||

| 2012/13 | 11,467 | 50,000 | 32,155 | ||||

| 2013/14 | 50,000 | 24,945 | |||||

| 2014/15 | 70,000 | 25,897 | |||||

| 2015/16 | 12,545 | 10,891 | |||||

| 2016/17 | 57,000 | 35,002 | 50,000 | ||||

| 2017/18 | 57,000 | 49,716 | 57,000 | ||||

| 2018/19 | 12,545 | 50,000 | 47,944 | 120,000 | |||

| 2019/20 | 150,000 | 92,585 | 60,000 | ||||

| 2020/21 | 12,319 | 520,000 | 34,869 | ||||

| 2021/22 | 520,000 | 42,684 | |||||

| 2022/23 | 12,318 | 520,000 | 51,762 | 50,000 | |||

| 2023/24 | 12,318 | 520,000 | 21,953 | 200,000 | |||

| 2024/25 | 12,333 | 520,000 | 152,667 | 300,000 | |||

| Totals | 3,367,000 | 772,168 | 287,000 | 193,529 | 550,000 | 347,387 | |

| 1 | The government ministry responsible for land matters has changed names several times over the years. The current name is the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements Development (MLHHSD). For ease of reading, we refer to it going forward as the Ministry of Lands and its minister as the Minister of Lands. |

| 2 | We note that the term wanyonge, meaning “the weak” or “the oppressed” (literally “those who are hanged”), features only in the Swahili name of this program but not in the English version nor in the Swahili acronym. In response to our query about this, the MKURABITA Director of Finance and Administration replied that it is so “because [President] Mkapa wanted it that way. He wanted to place local emphasis on the wanyonge.” Interview with authors, Dar es Salaam, 7 July 2010. |

| 3 | https://www.nbs.go.tz/statistics/topic/national-panel-survey-nps (accessed on 5 June 2023) [52]. |

| 4 | While in rural areas CROs are associated with large-scale (>50 acres) holdings, we did come across some cases of CROs held by small-scale landholders who had secured them through their own effort and expense. Some were obtained before the 2004 introduction of CCROs; other were pursued out of the belief that they are more secure than CCROs—a not unfounded perception since banks more readily accept CROs as collateral over CCROs. |

| 5 | Interview with Babati District Council members, Babati town, 30 September 2009. |

| 6 | Pedersen and Haule refer to the titling project by its subtitle: Business Environment Strengthening for Tanzania (BEST) program, a subcomponent of the Private Sector Competitiveness Project (PSCP). |

| 7 | Interviews with villagers, 2010–2024. |

| 8 | Interview with Dr. Stephen Nindi, Director General of the National Land Use Planning Commission, 14 September 2016. |

| 9 | We also interviewed district land officers who provided a larger range of costs for village land use plans, the upper end of which represents costs in the absence of any donor funding. |

| 10 | Interview with Dr. Stephen Nindi, 14 September 2016, op. cit. |

| 11 | The percentage of formalized rural land (CCROs) in Tanzania can be computed from the 2020–2021 Wave 5 NPS data [51] as: 11.6% for plots in the last long rainy season and 10.5% for plots in the last short rainy season; https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/5639 accessed on 11 February 2024. |

| 12 | Interview with various officials at the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements Development, Dar es Salaam, 7 June 2010. |

| 13 | The Anker Living Income Reference Value for Rural Tanzania was USD 200. https://www.globallivingwage.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Rural-Tanzania-LI-Reference-Value-.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2025). The World Bank’s commitment to the Land Tenure Improvement Program (LTIP) was recently canceled on 30 June 2025 at the request of the Tanzanian government, after disbursing USD 49.9 million. So the new rough estimate per title, assuming the remaining USD 100 million authorized for LTIP is not disbursed, would be USD 260 per title. It should be noted that the spending over time has not been adjusted for inflation and would be much higher in today’s dollars. |

| 14 | Persha et al. present survey results from self-titled landowners (who paid to acquire their CCROs) and cite the top three reasons as reducing disputes/increasing security, value appreciation and credit access [79], p. 19. Importantly, they found that those who did not purchase a CCRO did so for lack of financial means to do so, and that vulnerable groups encompassing women, widowers and the elderly were not only more at risk for dispossession but more likely to pay more for their CCROs than men or wealthy households. |

| 15 | Imputed income is an income measure we used in our study. It includes own-consumption and conceptually, empirically and reliably captures a rural household’s productive activities [80]. |

| 16 | The percentage of loan recipients who used a CCRO as collateral for Rural Mainland at 0.7% was low as well [50]. |

| 17 | Interestingly, this percentage from just 77 CCROs is not very different from the percentage (~28%) observed among the 347,387 CCROs registered in the LTIP project [67] (p. 15), providing support for the reliability of the discussion on gender and titling. |

| 18 | For greater accuracy, we limited analysis to those households in which the respondent identified as the head of household (as opposed to, say, a spouse who may not know whether or not they are included on the CCRO. |

| 19 | |

| 20 | Interview with Dr. Stephen Nindi, 14 September 2016, op. cit. |

| 21 | Tanzania’s score on Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI) is 38/100; https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2022/index/tza (accessed 4 February 2024). |

References

- Parsons, K.H. Basic Elements in the World Land Tenure Problems. J. Farm. Econ. 1956, 38, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorner, P. Land Tenure, Income Distribution and Productivity Interactions. Land Econ. 1964, 40, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, K.H. Economic Citizenship on the Land. Land Econ. 1954, 30, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, K.H. Land Reform in the Postwar Era. Land Econ. 1957, 33, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, S.R. Objects and Purposes of Land Registration. In Proceedings of the Economic Commission for Africa Seminar on Cadastre, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 25 November–9 December 1970; United Nations, Economic Commission for Africa: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Vaessen, J. Using ‘Theories of Change’ in International Development. Available online: https://ieg.worldbankgroup.org/blog/using-theories-change-international-development (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- German, L. Power/Knowledge/Land: Contested Ontologies of Land and Its Governance in Africa; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2022; ISBN 047205533X. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, H. Institutional Transformation and Shifting Policy Paradigms: Reflections on Land Reform in Africa. In Rethinking Land Reform in Africa: New Ideas, Opportunities and Challenges; Ochieng, C.M.O., Ed.; African Natural Resource Centre, African Development Bank: Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, 2020; pp. 85–110. [Google Scholar]

- Everest-Phillips, M. The Myth of ‘Secure Property Rights’: Good Economics as Bad History and Its Impact on International Development; Overseas Development Institute Working Paper; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- North, D.C. Structure and Change in Economic History; W. W. Norton & Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- North, D.C.; Weingast, B.R. Constitutions and Commitment: The Evolution of Institutions Governing Public Choice in Seventeenth-Century England. J. Econ. Hist. 1989, 49, 803–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Long, J.B.; Shleifer, A. Princes and Merchants: European City Growth before the Industrial Revolution. J. Law. Econ. 1993, 36, 671–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Housing: Enabling Markets to Work; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- de Soto, H. The Mystery of Capital; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 1-9773-5931-0. [Google Scholar]

- Alchian, A.A. Some Economics of Property Rights. Il Politico 1965, 30, 816–829. [Google Scholar]

- Demsetz, H. The Exchange and Enforcement of Property Rights. J. Law. Econ. 1964, 7, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noronha, R.; Lethem, F.J. Traditional Land Tenures and Land Use Systems in the Design of Agricultural Projects; Staff Working Paper; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, K.; Lerman, Z. Russian Federation—Land Reform and Farm Restructuring in Russia; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Deininger, K.; Binswanger, H. The Evolution of the World Bank’s Land Policy: Principles, Experiences, and Future Challenges. World Bank. Res. Obs. 1999, 14, 247–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Brink, R.; Thomas, G.; Binswanger, H.; Bruce, J.; Byamugisha, F. Consensus, Confusion, and Controversy: Selected Land Reform Issues in Sub-Saharan Africa; World Bank Working Paper; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dudwick, N.; Fock, K.; Sedik, D. Land Reform and Farm Restructuring in Transition Countries: The Experience of Bulgaria, Moldova, Azerbaijan, and Kazakhstan; World Bank Working Paper; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, P. Beyond Embeddedness: A Challenge Raised by a Comparison of the Struggles over Land in African and Post-Socialist Countries. In Changing Properties of Property; von Benda-Beckmann, F., von Benda-Beckhann, K., Wiber, M., Eds.; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 84–105. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, S. Debating the Land Question in Africa. Comp. Stud. Soc. Hist. 2002, 44, 638–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, C. Legal Empowerment of the Poor through Property Rights Reform: Tensions and Trade-Offs of Land Registration and Titling in Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Dev. Stud. 2019, 55, 384–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwood, D.A. Land Registration in Africa: The Impact on Agricultural Production. World Dev. 1990, 18, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrows, R.; Roth, M. Land Tenure and Investment in African Agriculture: Theory and Evidence. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 1990, 28, 265–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjaminsen, T.A.; Holden, S.; Lund, C.; Sjaastad, E. Formalisation of Land Rights: Some Empirical Evidence from Mali, Niger and South Africa. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, D.W. Formalising Property Relations in the Developing World: The Wrong Prescription for the Wrong Malady. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, D.W. Property Relations and Economic Development: The Other Land Reform. World Dev. 1989, 17, 867–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinzen-Dick, R.; Mwangi, E. Cutting the Web of Interests: Pitfalls of Formalizing Property Rights. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, S. African Land Questions, Agrarian Transitions and the State: Contradictions of Neo-Liberal Land Reforms; African Books Collective: Oxford, UK, 2008; ISBN 2869783841. [Google Scholar]

- Sjaastad, E.; Cousins, B. Formalisation of Land Rights in the South: An Overview. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toulmin, C. Securing Land and Property Rights in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Role of Local Institutions. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivji, I.G. Report of the Presidential Commission of Inquiry into Land Matters; The Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development, Government of the Republic of Tanzania: Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- United Republic of Tanzania. National Land Policy, 1995, 2nd ed.; Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements Development: Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 1997.

- United Republic of Tanzania. Sera Ya Taifa Ya Ardhi Ya Mwaka 1995 (Toleo Ya 2023); United Republic of Tanzania: Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- The Property and Business Formalization Programme. Executive Summary II: Reform Design Phase; The Property and Business Formalization Programme: Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Engström, L.; Bélair, J.; Blache, A. Formalising Village Land Dispossession? An Aggregate Analysis of the Combined Effects of the Land Formalisation and Land Acquisition Agendas in Tanzania. Land Use Policy 2022, 120, 106255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, H.; Odgaard, R.; Askew, K.M.; Maganga, F.P. The World Bank and Rural Land Titling in Africa: The Case of Tanzania. Dev. Change 2024, 55, 1150–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, T. The Properties of Markets: Informal Housing and Capitalism’s Mystery; Working Paper Series; Lancaster University: Lancaster, UK, 2004; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, H. Institutions, Structures and Policy Paradigms: Toward Understanding Inequality in Africa. In The Political Economy of Inequality: Global and U.S. Dimensions; Asefa, S., Huang, W.-C., Eds.; W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research: Kalamazoo, MI, USA, 2020; pp. 117–143. [Google Scholar]

- Reyna, S.P.; Downs, R.E. Introduction. In Land and Society in Contemporary Africa; Downs, R.E., Reyna, S.P., Eds.; University Press of New England: Hanover, NH, USA, 1988; pp. 1–22. ISBN 0-87451-456-8. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Migot-Adholla, S.; Hazell, P.; Blarel, B.; Place, F. Indigenous Land Rights Systems in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Constraint on Productivity? World Bank Econ. Rev. 1991, 5, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipton, P. The Kenyan Land Tenure Reform: Misunderstandings in the Public Creation of Private Property. In Land and Society in Contemporary Africa; University Press of New England: Hanover, NH, USA, 1988; pp. 91–135. ISBN 0-87451-456-8. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, T. The Properties of Markets. In Do Economists Make Markets?: On the Performativity of Economics; MacKenzie, D., Muniesa, F., Siu, L., Eds.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 244–275. ISBN 9780691214665. [Google Scholar]

- Juul, K.; Lund, C. Negotiating Property in Africa; Heinemann: Portsmouth, NH, USA, 2002; ISBN 0-325-07069-5. [Google Scholar]

- Falk Moore, S. Changing African Land Tenure: Reflections on the Incapacities of the State. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 1998, 10, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, C. Property and Political Order in Africa: Land Rights and the Structure of Politics; Cambridge Studies in Comparative Politics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 1-107-72320-5. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, R.H. Access to Land Reconsidered: The Land Grab, Polycentric Governance and Tanzania’s New Wave Land Reform. Geoforum 2016, 72, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Republic of Tanzania. National Panel Survey: Wave 5 Report, 2020–2021; National Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Finance and Planning: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2022. Available online: https://www.nbs.go.tz/statistics/topic/national-panel-survey-nps (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- United Republic of Tanzania. National Panel Survey 2020–2021, Wave 5 Microdata; National Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Finance and Planning: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2022. Available online: https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/5639 (accessed on 11 February 2024).

- Sullivan, T.; Solovov, A.; Mushaija, G.; Msigwa, M.; Issa, M. An Innovative, Affordable, and Decentralized Model for Land Registration and Administration at a National Scale in Tanzania. In Proceedings of the 2019 World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty, Washington, DC, USA, 25–29 March 2019; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Askew, K. Negotiated Outcomes in Low-Resourced Courts: Tanzania’s Land Courts System. In Negotiating Normative Spaces: Insights from and into African Judicial Encounters; Seidel, K., Elliesie, H., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 221–245. ISBN 1-00-301573-5. [Google Scholar]

- Havnevik, K.J.; Rwebangira, M.; Tivell, A. Land Management Programme in Tanzania. SIDA Evaluation 00/4; Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency: Stockholm, Sweden, 2000.

- PEM Consult. Final Evaluation of the Land Management Programme Phase II in Tanzania: Final Evaluation Report; PEM Consult: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, R.H.; Haule, S. Women, Donors and Land Administration: The Tanzania Case; DIIS Working Papers; Danish Institute for International Studies: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- United Republic of Tanzania, Ministry of Lands, Housing, and Human Settlements Development. Land Tenure Support Program (LTSP) Project Completion Report, 30th September 2019; United Republic of Tanzania: Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Walwa, W.J. Dispossession through Formalization? Examining the Implications of Land Formalization through Private Companies on Land Rights of Communities in Tanzania’s Urban Areas. In Proceedings of the Perspectives on Wealth in Africa Summer School, Kampala, Uganda, 17 September 2024; Makerere University: Kampala, Uganda, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bluwstein, J.; Lund, J.F.; Askew, K.; Stein, H.; Noe, C.; Odgaard, R.; Maganga, F.; Engström, L. Between Dependence and Deprivation: The Interlocking Nature of Land Alienation in Tanzania. J. Agrar. Change 2018, 18, 806–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laltaika, E.I.; Askew, K.M. Modes of Dispossession of Indigenous Lands and Territories in Africa. In Lands of the Future: Anthropological Perspectives on Pastoralism, Land Deals and Tropes of Modernity in Eastern Africa; Gabbert, E.C., Gebresenbet, F., Galaty, J.G., Schlee, G., Eds.; Berghahn Books: Oxford, UK, 2021; pp. 99–122. ISBN 978-1-80539-120-3. [Google Scholar]

- United Republic of Tanzania. Basic Facts and Figures on Human Settlements, 2012: Tanzania Mainland; United Republic of Tanzania: Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, S.T.; Otsuka, K. The Roles of Land Tenure Reforms and Land Markets in the Context of Population Growth and Land Use Intensification in Africa. Food Policy 2014, 48, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Republic of Tanzania. Hotuba Ya Waziri Wa Ardhi, Nyumba Na Maendeleo Ya Makazi, Mheshimiwa John Pombe Magufuli, (MB), Akiwasilisha Bungeni Makadirio Ya Mapato Na Matumizi Ya Wizara Kwa Mwaka Wa Fedha 2007/08; United Republic of Tanzania: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- United Republic of Tanzania. Hotuba Ya Waziri Wa Ardhi, Nyumba Na Maendeleo Ya Makazi, Mheshimiwa Deogratius J. Ndejembi (MB.), Akiwasilisha Bungeni Makadirio Ya Mapato Na Matumizi Ya Wizara Kwa Mwaka 2025/26; United Republic of Tanzania: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- United Republic of Tanzania. Muhtasari Wa Hotuba Ya Waziri Wa Ardhi, Nyumba Na Maendeleo Ya Makazi, Mheshimiwa Jerry W. Silaa (MB.),Akiwasilisha Bungeni Makadirio Ya Mapato Na Matumizi Ya Wizara Ya Mwaka 2024/25; United Republic of Tanzania: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Walwa, W.J. Land Use Plans in Tanzania: Repertoires of Domination or Solutions to Rising Farmer–Herder Conflicts? J. East. Afr. Stud. 2017, 11, 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. The Tanzania Land Tenure Improvement Project (LTIP) (P164906) Implementation Support Mission June 2 to 6, Aide-Memoire; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Land Tenure Improvement Project (P164906) Implementation Status and Results Report; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sumari, N.S.; Ujoh, F.; Samwel Swai, C.; Zheng, M. Urban Growth Dynamics and Expansion Forms in 11 Tanzanian Cities from 1990 to 2020. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2023, 16, 1985–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singirankabo, U.A.; Ertsen, M.W.; van de Giesen, N. The Relations between Farmers’ Land Tenure Security and Agriculture Production. An Assessment in the Perspective of Smallholder Farmers in Rwanda. Land Use Policy 2022, 118, 106122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maganga, F.; Askew, K.; Odgaard, R.; Stein, H. Dispossession Through Formalization: Tanzania and the G8 Land Agenda in Africa. Asian Journal of African Studies 2016, 40, 3–49. [Google Scholar]

- Odgaard, R. Scrambling for Land in Tanzania: Processes of Formalisation and Legitimisation of Land Rights. In Securing Land Rights in Africa; Benjaminsen, T.A., Lund, C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 71–88. ISBN 0714683159. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T. Practices of Assemblage and Community Forest Management. Econ. Soc. 2007, 36, 263–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleaver, F. Development Through Bricolage: Rethinking Institutions for Natural Resource Management; Routledge: Abingdon and Oxon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 9781844078684. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, C. Negotiating Property Institutions: On the Symbiosis of Property and Authority in Africa. In Negotiating Property in Africa; Juul, K., Lund, C., Eds.; Heinemann: Portsmouth, NH, USA, 2002; pp. 11–43. [Google Scholar]

- Boone, C. Political Topographies of the African State: Territorial Authority and Institutional Choice; Cambridge Studies in Comparative Politics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2003; ISBN 0521825571. [Google Scholar]

- Amanor, K. Global Restructuring and Land Rights in Ghana: Forest Food Chains, Timber, and Rural Livelihoods; Nordic Africa Institute: Uppsala, Sweden, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. International Development Association Project Appraisal Document on a Proposed Credit in the Amount of SDR 106.5 Million (US$150 Million Equivalent) to the United Republic of Tanzania for a Land Tenure Improvement Project. Report No. PAD2833. November 30; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Persha, L.; Panfil, Y.; Sherman, S.; Mpelembe, M.I.; Rutizibwa, M. Tanzania Demand for Documentation Study: Who Pays for Land Documents, and Why? United States Agency for International Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- Stein, H.; Askew, K.; Nagaraj, S.; Odgaard, R.; Maganga, F. Assessing Poverty Interventions: Conceptual, Methodological and Empirical Perspectives Relating to Property Rights Formalization in Rural Tanzania. Mod. Econ. 2025, 16, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rweyemamu, A. Land Cases Takes the Lead with 850 Filed Annually. The Guardian, 16 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- The Citizen. Editorial: Why Land Dispute Cases Are on the Rise. The Citizen, 14 February 2016.

- Christopher, J. Land: Digitalization a Priority as Government Eyes Sh8 Trillion Investment. The Citizen, 26 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cotula, L.; Toulmin, C.; Hesse, C. Land Tenure and Administration in Africa: Lessons of Experience and Emerging Issues; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Obeng-Odoom, F. Land Reforms in Africa: Theory, Practice, and Outcome. Habitat. Int. 2012, 36, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, T. The Work of Economics: How a Discipline Makes Its World. Eur. J. Sociol. 2005, 46, 297–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, H.; Maganga, F.P.; Odgaard, R.; Askew, K.; Cunningham, S. The Formal Divide: Customary Rights and the Allocation of Credit to Agriculture in Tanzania. J. Dev. Stud. 2016, 52, 1306–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askew, K.; Odgaard, R. Deeds and Misdeeds: Land Titling and Women’s Rights in Tanzania. New Left Rev. 2019, 118, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, R.H. A Less Gendered Access to Land? The Impact of Tanzania’s New Wave of Land Reform. Dev. Policy Rev. 2015, 33, 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Republic of Tanzania, Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements Development. Private Sector Competitiveness Project: Component 1, Sub-Component B: Land Reforms, Evaluation Report for Pilot Project on Systematic Adjudication in Babati, Bariadi, Namtumbo and Manyoni Districts–Tanzania, Phase 1 (February- December 2009); United Republic of Tanzania: Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Maganga, F.; Askew, K.; Odgaard, R.; Stein, H. Dispossession through Formalization: Tanzania and the G8 Land Agenda in Africa. Asian J. Afr. Stud. 2016, 40, 3–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hillbom, E. The Right to Water: An Inquiry into Legal Empowerment and Property Rights Formation in Tanzania. In The Legal Empowerment Agenda: Poverty, Labour and the Informal Economy in Africa; Banik, D., Ed.; Ashgate: Surrey, UK, 2011; pp. 193–214. ISBN 131523873X. [Google Scholar]

- Lawal, S. Tanzania Wants to Evict Maasai for Wildlife—But They’re Fighting Back. Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2024/8/5/tanzania-wants-to-evict-maasai-for-wildlife-but-theyre-fighting-back (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Nnoko, J.; Nyeko, O. Conservation in Tanzania No Excuse to Violate Indigenous Rights|Human Rights Watch. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/08/09/conservation-tanzania-no-excuse-violate-indigenous-rights (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Oakland Institute Setting the Record Straight About Evictions & Abuses to Expand Ruaha National Park. Available online: https://www.oaklandinstitute.org/setting-record-straight-about-evictions-abuses-expand-ruaha-national-park (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Sharland, H. Maasai Displaced for Luxury Safari Tourism in More Land-Grabbing. Available online: https://www.thecanary.co/global/world-news/2024/04/18/land-grabbing-luxury-safari-tourism-is-displacing-maasai-communities-in-tanzania/ (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Peters, P. The Limits of Negotiability: Security, Equity and Class Formations in Africa’s Land Systems. In Negotiating Property in Africa; Juul, K., Lund, C., Eds.; Heinemann: Portsmouth, NH, USA, 2002; pp. 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- Hann, C. Socialism: Ideals, Ideologies and Local Practice; Hann, C., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1993; ISBN 9781134889396. [Google Scholar]

- United Republic of Tanzania. Hotuba Ya Waziri Wa Ardhi, Nyumba Na Maendeleo Ya Makazi, Mheshimiwa William V. Lukuvi (MB.), Akiwasilisha Bungeni Makadirio Ya Mapato Na Matumizi Ya Wizara Kwa Mwaka Wa Fedha 2019/20; United Republic of Tanzania: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- United Republic of Tanzania. Hotuba Ya Waziri Wa Ardhi, Nyumba Na Maendeleo Ya Makazi, Mheshimiwa William V. Lukuvi (MB.) Akiwasilisha Bungeni Makadirio Ya Mapato Na Matumizi Ya Wizara Kwa Mwaka Wa Fedha 2020/2021; United Republic of Tanzania: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- United Republic of Tanzania. Hotuba Ya Waziri Wa Ardhi, Nyumba Na Maendeleo Ya Makazi, Mheshimiwa William V. Lukuvi (MB.), Akiwasilisha Bungeni Makadirio Ya Mapato Na Matumizi Ya Wizara Kwa Mwaka Wa Fedha 2021/22; United Republic of Tanzania: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- United Republic of Tanzania. Hotuba Ya Waziri Wa Ardhi, Nyumba Na Maendeleo Ya Makazi, Mheshimiwa Dkt. Angeline S.L. Mabula (MB.), Akiwasilisha Bungeni Makadirio Ya Mapato Na Matumizi Ya Wizara Kwa Mwaka 2022/23; United Republic of Tanzania: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- United Republic of Tanzania. Hotuba Ya Waziri Wa Ardhi, Nyumba Na Maendeleo Ya Makazi, Mheshimiwa Dkt. Angeline S.L. Mabula (MB.), Akiwasilisha Bungeni Makadirio Ya Mapato Na Matumizi Ya Wizara Kwa Mwaka 2023/24; United Republic of Tanzania: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- United Republic of Tanzania. Makadirio Ya Mapato Na Matumizi Ya Wizara Ya Ardhi, Nyumba Na Maendeleo Ya Makazi Kwa Mwaka Wa Fedha 2017/2018.; United Republic of Tanzania: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- United Republic of Tanzania. Hotuba Ya Waziri Wa Ardhi, Nyumba Na Maendeleo Ya Makazi, Mheshimiwa William V. Lukuvi (MB.), Akiwasilisha Bungeni Makadirio Ya Mapato Na Matumizi Ya Wizara Kwa Mwaka Wa Fedha 2018/2019; United Republic of Tanzania: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- United Republic of Tanzania. Hotuba Ya Mhe. John Zefania Chiligati, (MB.), Waziri Wa Ardhi, Nyumba Na Maendeleo Ya Makazi, Akiwasilisha Bungeni Makadirio Ya Mapato Na Matumizi Ya Wizara Ya Ardhi, Nyumba Na Maendeleo Ya Makazi, Kwa Mwaka 2010/11; United Republic of Tanzania: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- United Republic of Tanzania. Hotuba Ya Waziri Wa Ardhi, Nyumba Na Maendeleo Ya Makazi, Mheshimiwa Prof. Anna Kajumulo Tibaijuka (MB), Akiwasilisha Bungeni Makadirio Ya Mapato Na Matumizi Ya Wizara Ya Ardhi, Nyumba Na Maendeleo Ya Makazi, Kwa Mwaka Wa Fedha 2011/2012; United Republic of Tanzania: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- United Republic of Tanzania. Hotuba Ya Waziri Wa Ardhi, Nyumba Na Maendeleo Ya Makazi Mheshimiwa Prof. Anna Kajumulo Tibaijuka Akiwasilisha Bungeni Makadirio Ya Mapato Na Matumizi Ya Wizara Hiyo Kwa Mwaka Wa Fedha 2013/2014; United Republic of Tanzania: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- United Republic of Tanzania. Taarifa Ya Mafanikio Ya Utekelezaji Wa Majukumu Ya Wizara Kwa Kipindi Cha Miaka Minne Kati Ya Desemba 2005 Hadi Desemba 2009; United Republic of Tanzania: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- United Republic of Tanzania. Hotuba Ya Waziri Wa Ardhi, Nyumba Na Maendeleo Ya Makazi, Mheshimiwa Prof. Anna Kajumulo Tibaijuka (MB.), Akiwasilisha Bungeni Makadirio Ya Mapato Na Matumizi Ya Wizara Ya Ardhi, Nyumba Na Maendelea Ya Makazi Kwa Mwaka Wa Fedha 2014/2015; United Republic of Tanzania: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- United Republic of Tanzania. Hotuba Ya Waziri Wa Ardhi, Nyumba Na Maendeleo Ya Makazi, Mheshimiwa William V. Lukuvi (MB.), Akiwasilisha Bungeni Makadirio Ya Mapato Na Matumizi Ya Wizara Kwa Mwaka Wa Fedha 2015/16; United Republic of Tanzania: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- United Republic of Tanzania. Hotuba Ya Waziri Wa Ardhi, Nyumba Na Maendeleo Ya Makazi Kuhusu Makadirio Ya Mapato Na Matumizi Ya Wizara Hiyo Kwa Mwaka Wa Fedha 2016/2017; United Republic of Tanzania: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- United Republic of Tanzania. Hotuba Ya Waziri Wa Ardhi, Nyumba Na Maendeleo Ya Makazi, Mheshimiwa Prof. Anna Kajumulo Tibaijuka (MB), Akiwasilisha Bungeni Makadirio Ya Mapato Na Matumizi Ya Wizara Ya Ardhi, Nyumba Na Maendeleo Ya Makazi, Kwa Mwaka Wa Fedha 2012/2013; United Republic of Tanzania: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- United Republic of Tanzania. Hotuba Ya Waziri Wa Ardhi, Nyumba Na Maendeleo Ya Makazi, Mheshimiwa William V. Lukuvi (MB.), Akiwasilisha Bungeni Makadirio Ya Mapato Na Matumizi Ya Wizara Kwa Mwaka Wa Fedha 2017/2018; United Republic of Tanzania: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Program Name | Land Management Program (LAMP) | Mbozi Pilot Project | Private Sector Competitiveness Project (PSCP) | Property and Business Formalization Program MKURABITA | Women’s Social and Economic Empowerment Program | Mobile Application to Secure Tenure (MAST) | Feed the Future Land Tenure Assistance (LTA) | Land Tenure Support Program (LTSP) | Land Tenure Improvement Project (LTIP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Year | 1997 | 2002 | 2005 | 2006 | 2009 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2021 |

| Donor or NGO | SIDA | European Union | World Bank | NORAD | Concern | USAID | USAID | DFID/FCDO DANIDA SIDA | World Bank |

| Lead Agency | Prime Minister’s Office | Ministry of Lands | Ministry of Lands | President’s Office | District Govt | Village Govt | Ministry of Lands | Ministry of Lands | Ministry of Lands |

| Type | Land use planning, Village certification, Spot titling | Village certification, Spot titling | Systematic titling | Spot titling | Spot titling | Spot titling | Spot titling | Systematic titling | Systematic titling |

| Technology | Surveyor, Aerial photos, GPS/GIS | Aerial photos, GPS/GIS | Satellite imaging | GPS/GIS | Surveyor | Crowd sourcing, Mobile app | Satellite Imaging, Mobile app | GPS/GIS | Drones, Mobile app |

| Total | None | Donor-Sponsored Initiatives | Self-Supported Initiatives | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spot Coverage | Comprehensive Coverage | ||||

| Number of Villages | 40 | 21 | 6 | 8 | 5 |

| Villages with, or adjacent to, large investment schemes (% of villages) | 57.5% | 47.6% | 33.3% | 75.0% | 100% |

| Villages with a SACCO or VICOBA (% of villages) | 47.5% | 33.3% | 66.7% | 87.5% | 20.0% |

| Total | None | Donor-Sponsored Initiatives | Self-Supported Initiatives | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spot Coverage | Comprehensive Coverage | ||||

| Number of Heads of Household (HH) | 1510 | 760 | 257 | 292 | 201 |

| Owned land (% of HH) | 89.8% | 87.9% | 91.8% | 94.5% | 87.6% |

| Number of landowners with a CCRO | 118 | 0 | 31 | 65 | 22 |

| Percentage of landowners with a CCRO | 6.4% | 0.0% | 9.4% | 17.8% | 10.1% |

| Median real (2019) annual imputed income per capita (USD) of landowners with a CCRO | $117.04 | $73.61 | $83.10 | $202.82 | |

| No CCRO | CCRO | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Heads of Household (HH) | 1298 | 100 | 1398 |

| Felt insecure (% of HH) | 43.1% | 27.0% | 41.9% |

| Was involved in a land conflict (% of HH) | 18.0% | 8.0% | 17.3% |

| Felt CCRO has not improved life (% of HH) | 65.3% | ||

| Number of HH who felt insecure | 559 | 27 | 586 |

| Worried about government takeover (% of those who felt insecure) | 53.7% | 74.1% | 54.6% |

| Lived in village with large investments inside or outside (% of those who felt insecure) | 64.8% | 70.4% | 65.0% |

| Lived in village with designated conservation sites inside or outside village (% of those who felt insecure) | 84.4% | 100% | 85.2% |

| No CCRO | CCRO | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Heads of Household (HH) | 1310 | 92 | 1402 |

| Had a Savings Accounts (n, % of HH) | 181 (13.8%) | 29 (31.5%) | 210 (15.0%) |

| Had a loan from a savings institution (n, % of savings account holders) | 63 (34.8%) | 16 (55.2%) | 79 (37.6%) |

| Used collateral (n, % of loan recipients) | 45 (71.4%) | 14 (87.5%) | 59 (74.7%) |

| Used loan for agricultural investment (n, % of loan recipients) | 14 (22.2%) | 7 (43.8%) | 21 (26.6%) |

| Used CCRO as collateral (n, % of loan recipients) | 1 (6.2%) | 1 (1.2%) |

| Female | Male | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Heads of Household (HH) | 134 | 323 | 457 |

| Owns land (% of HH) | 87.3% | 91.6% | 90.4% |

| Had a CCRO (% of landowning HH) | 17.2% | 16.7% | 16.9% |

| Number with a CCRO | 23 | 54 | 77 |

| Single (% of CCRO holders) | 00% | 2 3.7% | 2 2.6% |

| Currently married (% of CCRO holders) | 6 26.1% | 52 96.3% | 58 75.3% |

| Separated, divorced or widowed (% of CCRO holders) | 17 73.9% | 00% | 17 22.1% |

| Photo of owner only (% of CCRO holders) | 12 52.2% | 28 51.9% | 40 52.0% |

| Photos of owner and spouse (% of CCRO holders) | 10 43.5% | 24 44.4% | 34 44.2% |

| Photos of owner and spouse, and son or father (% of CCRO holders) | 1 4.4% | 2 3.7% | 3 3.9% |

| Farmers | Pastoralists | Others ^ | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Heads of Household (HH) | 1394 | 121 | 50 | 1565 |

| Lived in a village with self, spot or comprehensive titling (n, % of HH) | 742 (53.2%) | 13 (10.7%) | 22 (44.0%) | 777 (49.7%) |

| Owned land (% of HH) | 89.9% | 89.3% | 78.0% | 89.5% |

| Number of landowners | 1253 | 108 | 39 | 1400 |

| Had a CCRO (n, % of landowners) | 98 (7.8%) | 1 (0.9%) | 2 (5.1%) | 101 (7.2%) |

| Sector | Rank | Mean | Median | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| Water | 46% | 19% | 13% | 12% | 10% | 2.2 | 2.0 |

| Health | 19% | 34% | 24% | 16% | 6% | 2.6 | 2.0 |

| Education | 11% | 19% | 33% | 26% | 10% | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Roads | 9% | 16% | 18% | 29% | 27% | 3.5 | 4.0 |

| Titling | 14% | 11% | 11% | 17% | 46% | 3.7 | 4.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Owens, K.E.; Askew, K.M.; Nagaraj, S.; Maganga, F.; Stein, H.; Odgaard, R. Titling as Land Reform in Tanzania: Contours, Conflicts and Convergence. Land 2025, 14, 2247. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112247

Owens KE, Askew KM, Nagaraj S, Maganga F, Stein H, Odgaard R. Titling as Land Reform in Tanzania: Contours, Conflicts and Convergence. Land. 2025; 14(11):2247. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112247

Chicago/Turabian StyleOwens, Kathryn E., Kelly M. Askew, Shyamala Nagaraj, Faustin Maganga, Howard Stein, and Rie Odgaard. 2025. "Titling as Land Reform in Tanzania: Contours, Conflicts and Convergence" Land 14, no. 11: 2247. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112247

APA StyleOwens, K. E., Askew, K. M., Nagaraj, S., Maganga, F., Stein, H., & Odgaard, R. (2025). Titling as Land Reform in Tanzania: Contours, Conflicts and Convergence. Land, 14(11), 2247. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112247