Abstract

Sand dune migration, as a typical dynamic process of aeolian geomorphology in arid regions, directly influences regional ecological security and infrastructure development. Focusing on the western edge of the Kumtag Desert, this study uses remote sensing imagery and field investigations, combined with multi-factor meteorological observations and CMIP6 climate scenarios, to quantitatively analyze the migration characteristics and influencing factors of representative dunes, and to construct a predictive model for future migration trends. The dominant migration direction is W–WNW–NW, which closely matches the composite resultant drift potential. The average annual migration speed is 12.86 m·a−1, classifying these dunes as fast-moving; small to medium dunes migrate faster (13.84 m·a−1) than large dunes (11.27 m·a−1). Wind speed, sand-moving wind frequency, drift potential (DP), Vegetation Fractional Cover (FVC), and precipitation significantly affect migration speeds; wind speed is the primary driver (single-factor R2 = 0.41), while precipitation (R2 = 0.26) and FVC (R2 = 0.27) exert a suppressing effect, particularly on small to medium dunes. Based on stepwise multiple regression analysis combined with CMIP6 multi-model predictions, under the SSP8.5 scenario, characterized by significant temperature increases, drastic fluctuations in precipitation patterns, and notable increases in wind speed, the average annual sand dune migration speed is projected to reach 18.59 m·a−1 by the end of this century, an increase of 5.78 m·a−1 compared to the current speeds; whereas under the SSP1–2.6 and SSP2–4.5 scenarios, changes are projected to be minor and overall relatively stable. The findings of this study provide a scientific basis for regional infrastructure and engineering planning, as well as for the renovation and protection of existing oil and power transmission lines.

1. Introduction

Sand dune migration is a key dynamic process in the aeolian geomorphology of arid regions, with its evolutionary patterns profoundly impacting regional ecological security and infrastructure development [1,2,3]. Primarily wind-driven, this process involves sand particle movement via creep, saltation, and suspension once wind velocity exceeds the critical threshold [4]. Migration speeds vary significantly by dune type: barchan dunes—characterized by simple morphology and formation under unidirectional winds [5]—can migrate over 10 m·a−1, ranking among the most mobile dune types [6,7], while linear and star dunes migrate more slowly [8]. As a core research focus, understanding barchan dune morphodynamics is crucial for predicting their migration paths and mitigating agricultural and infrastructure hazards, and insights from such studies provide a scientific basis for resource management and sand-control engineering in sandy regions.

The migration of sand dunes is a complex process resulting from the interaction between the physical properties of sand materials and environmental factors. Wind serves as the direct driving force, with its intensity, frequency, and direction governing the migration path and speeds of sand dunes [8,9]. For instance, in Qatar, sand dune migration has been demonstrated to be closely associated with the prevailing “Shamal” wind system [10]. Similarly, research by Li et al. (2021) [11] in the Ulan Buh Desert revealed a positive correlation between drift potential and sand dune migration distance. Beyond wind conditions, vegetation acts as another key controlling factor by covering the surface and altering sand flux [12,13]. Studies by Mahmoud et al. (2020) [14] in northern Sudan indicated that the migration speeds of sand dunes in vegetated areas is significantly lower than in bare sand regions. In the Mu Us Sandy Land, vegetation recovery has even been shown to promote sand dune stabilization [15,16]. Furthermore, climate change exerts profound influences by regulating hydrothermal conditions. For example, Dörwald et al. (2023) [17] reported that increased precipitation and temperature over the past 50 years on the Tibetan Plateau have led to a deceleration in sand dune migration. Therefore, understanding these complex interrelationships and establishing accurate predictive models are of great significance for research in geomorphology and environmental science. In the development of predictive models for sand dune migration, the seasonal autoregressive integrated moving average (SARIMA) model has been applied to forecast the spatiotemporal dynamics of sand dunes in the Errachidia region of Morocco [18]. Additionally, Megahed et al. (2024) [19] utilized a linear support vector machine (SVM) to model sand dune erosion in the Western Desert of Egypt, providing decision support for urban planning and road maintenance.

The Kumtag Desert, as a typical high-mobility desert in China, has relatively limited research on the driving mechanisms of sand dune migration. Existing studies have indicated that the migration of sand dunes on the western edge of this desert is influenced by factors such as height, width [20], and local wind fields [21]. However, the quantitative contribution of environmental factors has not yet been clarified. More importantly, in our field investigation, we found that there are important transmission lines and oil pipelines distributed on the western edge of the area. Strong winds and active sand dune activity have caused the sand dunes to continue to move rapidly eastward, leading to serious problems such as wind erosion exposure of pole foundations and sand accumulation and burial along the pipeline, posing a direct threat to infrastructure safety. Despite the implementation of engineering reinforcement measures, the erosion caused by quicksand still leads to the failure of protective facilities. Therefore, it is urgent to conduct systematic research on the migration characteristics and future evolution trends of sand dunes in this region, providing scientific guidance for the relocation planning and protection measures optimization of transmission lines and oil pipelines, and ultimately achieving effective prevention and control of sandstorms and long-term guarantee of infrastructure operation safety.

In view of this, this study takes the western edge of the Kumtag Desert as the research area, and uses multi-period high-resolution remote sensing image data combined with field investigations to quantitatively analyze the dynamic characteristics of sand dune migration speeds in the research area; by observing and recording the multi-element meteorological environment in the research area, the wind conditions, sand dune migration patterns, and key driving factors affecting sand dune migration speed in the region are clarified, and a quantitative relationship model between sand dune migration speed and core influencing factors is constructed. In addition, based on CMIP6 multimodal integrated data, further predictions were made on the future evolution trends of sand dune movement under different climate scenarios (SSP1–2.6, SSP2–4.5, and SSP5–8.5). These research findings will provide a scientific basis for regional infrastructure planning and the renovation and protection of existing oil and power transmission lines. Additionally, they will serve as an important reference for infrastructure planning and the prevention and control of wind and sand disasters in similar environments in arid regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The study area is located in the northwest arid region of China, on the western edge of the Kumtag Desert in Shanshan (42°37′ N, 89°41′ E), which has an extremely arid continental climate. The average annual precipitation is below 25 mm, and the average annual evaporation exceeds 2800 mm, with speeds in desert areas even surpassing 3000 mm. Due to its extreme aridity and low rainfall, this region is referred to as the “Extreme Drought Zone” [22]. The Kumtag Desert experiences intense wind and sand activity, being consistently influenced by prevailing westerly winds, with an annual average wind speed ranging from 1.2 to 1.8 m·s−1. Days with winds exceeding level 8 occur more than 100 days a year, with maximum wind speeds reaching up to 25 m·s−1. The strong wind characteristics provide the driving conditions necessary for the formation and development of the desert. The surface is covered with extensive areas of moving sand, and under the influence of wind, there are frequent sandstorm and dust weather events. This region is one of the areas in China with a high frequency of dust storms and significant dune mobility, with its area of wind erosion ranking second nationally [22,23].

2.2. Data and Methods

2.2.1. Wind Characteristics

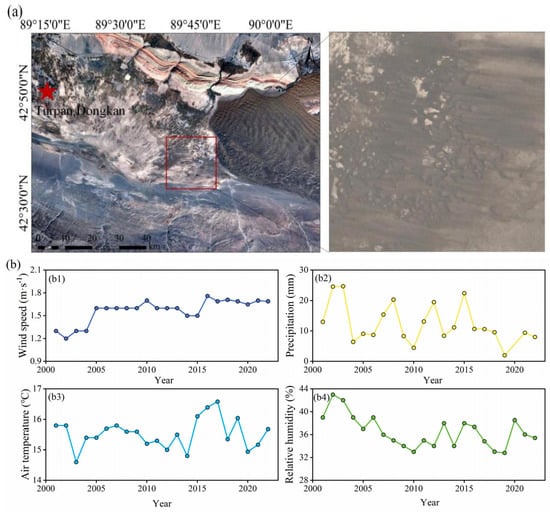

As shown in Figure 1, hourly observations (wind speed, wind direction, precipitation, air temperature, and relative humidity) from the Turpan Dongkan meteorological station—the nearest long-term station to the study area—for 2003–2019 were compiled and processed (Figure 1a). This station has been widely used in previous studies of the local wind–sand environment and its applicability for the study area has been validated [20]. According to earlier work, the sand-moving wind threshold in the study area at 10 m height is 6.0 m·s−1 [20,22]; therefore, only wind-speed records exceeding this threshold were selected as effective sand-moving wind events for statistical analysis (Figure 2). Drift potential (DP) quantifies the capacity of winds from a given direction to transport sand over a period and is used to evaluate wind-energy intensity and the directional composition of the wind regime. DP was calculated using the Fryberger–Dean method [24]. The DP for a wind class is computed as:

where DP is the drift potential (units: VU); V is wind speed at 10 m height; Vt is the sand-moving wind threshold at 10 m height; and t is the percentage frequency of occurrence of wind speed V in the record. DP not only assesses relative wind-energy strength but also characterizes the directional composition of the wind regime. Conventionally, DP < 200 VU indicates a low wind-energy environment; DP between 200 and 400 VU indicates a moderate wind-energy environment; and DP > 400 VU indicates a high wind-energy environment [24]. By vector-synthesizing the drift potential in 16 azimuthal directions, the resultant drift potential (RDP) and resultant drift direction (RDD) can be obtained. RDP represents the net sand-transporting capacity of a region, while RDD reflects the overall direction of sand transport. The ratio RDP/DP is used as an index of directional variability [25].

DP = V2 (V − Vt)t

Figure 1.

(a) Geographic location of the study area (the red pentagram indicates the Turpan Dongkan Meteorological Station); (b) annual average trend of various meteorological elements in the study area from 2001 to 2022 ((b1)–(b4) represent wind speed/m·s−1, precipitation/mm, air temperature/°C, and relative humidity/%, respectively).

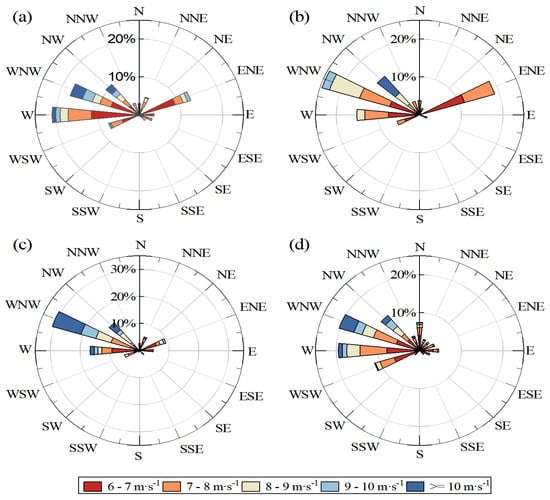

Figure 2.

Sand-moving wind direction rose diagrams in the study area from 2001 to 2022; (a), (b), (c), and (d) represent the sand-moving wind directions during periods P1 (2003–2010), P2 (2010–2011), P3 (2011–2013), and P4 (2013–2019), respectively.

2.2.2. Imagery Data

This study is based on the Google Earth platform to obtain five high-resolution remote sensing images (with a spatial resolution of 0.22 m) from 2003, 2010, 2011, 2013, and 2019. All images were reprojected to WGS 1984/UTM (Northern Hemisphere, zone 45) and geometrically corrected against 1:50,000 topographic maps to ensure a total positional error of less than one pixel. After radiometric enhancement, dune boundaries were manually interpreted and digitized by trained analysts. Combined with field surveys, 24 representative, isolated crescentic sand dunes were identified within the study area.

To analyze sand dune migration, the study period was divided into four stages: P1 (2003–2010), P2 (2010–2011), P3 (2011–2013), and P4 (2013–2019). Migration distance of each dune was determined by measuring the displacement of the same lee-side toe point between two successive images; mean annual migration speed was calculated by dividing migration distance by the number of years in the interval. To investigate the influence of dune size on migration behavior, dunes were classified into three size categories using the natural breaks method: small (<65,000 m2), medium (65,000–95,000 m2), and large (≥95,000 m2).

2.2.3. Analysis of Environmental Drivers

To quantify the effects of environmental drivers on sand dune migration, the following candidate variables were selected: sand-moving wind frequency, drift potential (DP), fractional vegetation cover (FVC), wind speed, precipitation, air temperature, and relative humidity. Correlation analysis and Random Forest (RF) modeling were first used to evaluate variable importance and to identify the key drivers affecting dune migration. Based on the RF screening results, linear regression analyses between migration speed and the selected key variables were performed to quantify relationships; finally, SPSS 27.0.1 software was used to gradually establish an estimation equation for sand dune migration speed through multiple regression analysis. The FVC data were obtained from the China regional annual 250 m resolution product (2003–2019) published by the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center. This product is derived from a two-endmember (vegetation–soil) model; land-use information is used to determine pure vegetation and bare-soil endmember values, and FVC is calculated from the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) [26]. The Random Forest analysis was implemented in Python 3.9. The model was configured with the following parameters: n_estimators = 150, max_features = 0.7, min_samples_leaf = 5, and max_depth = 4, with bootstrap enabled. To ensure robust assessment of variable importance, we utilized permutation importance combined with cross-validation.

2.2.4. CMIP6 Data

To assess the applicability of CMIP6 climate models (Data sourced from the official website: https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/projects/cmip6) in the study area, observational data from Turpan Dongkan station for 2001–2019 were used as the reference and paired monthly with the simulated data at the corresponding CMIP6 model grid points from 15 models. Evaluated variables included wind speed, precipitation, and air temperature. A month-by-month paired comparison was conducted, and the root-mean-square error (RMSE) for each variable was computed using SPSS 27.0.1. Based on the evaluation results, three best-performing models—BCC-CSM2-MR, MIROC6, and CanESM5—were selected (Table 1). On this basis, the selected data were bias-corrected; the bias-corrected CMIP6 data under different scenarios (including SSP1–2.6, SSP2–4.5, and SSP5–8.5) were then input into a stepwise multiple regression model to analyze and predict future dune migration trends.

Table 1.

Optimal CMIP6 climate models selected based on RMSE evaluation.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Study Area Wind Regime Analysis

Wind speed and direction are critical factors influencing aeolian sand dune activity. Wind speed determines the intensity of wind erosion, while wind direction controls the migration and accumulation orientation of sand dunes. The sand-moving winds (≥6 m·s−1) in the study area originated predominantly from the W, WNW, and NW directions. Among these, winds from the W and WNW directions exhibited the highest frequency of sand-moving events, followed by those from the NW direction (Figure 2). However, while wind rose diagrams illustrate the frequency distribution of wind directions, assessing the intensity of regional aeolian activity and the potential sand transport capacity requires comprehensive analysis using the drift potential.

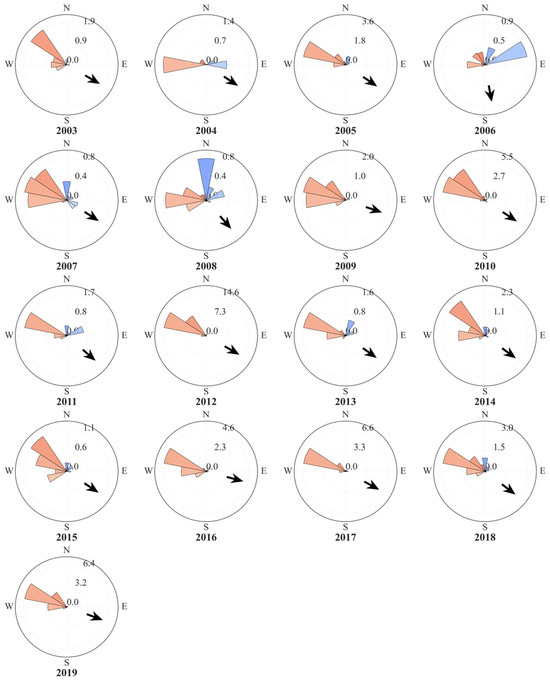

The annual drift potential in the study area ranged from 0 to 26 vector units (VUs) (Table 2). According to Fryberger’s classification of wind-energy environments (DP < 200 VU), this region falls into the low-energy wind environment category. Significant interannual fluctuations were observed in the drift potential, with the highest value occurring in 2012 (26 VU), followed by 2019 (13.5 VU). In contrast, the years 2006 (2.5 VU) and 2008 (3.3 VU) recorded relatively lower values. Interannual variability is closely related to the frequency and intensity of regional strong-wind events. For example, the markedly elevated DP value in 2012 coincides with successive strong wind and dust-storm events in April of that year, reflecting the significant contribution of intense wind activity to the drift potential. As shown in Figure 3, the resultant drift direction (RDD) was predominantly oriented towards W, WNW, and NW, consistent with the dominant wind directions. Furthermore, the resultant drift potential (RDP) exhibited a high degree of correspondence with the interannual variations in drift potential. Specifically, years with higher drift potential values also showed enhanced RDP. The directional variability index (RDP/DP) in the study area ranged between 0.45 and 0.92, indicating moderate directional variability. This suggests that aeolian activity in the region is influenced by multiple wind directions, although the W-WNW sector remained the dominant orientation.

Table 2.

Variations in the wind-energy environment of the study area for the period 2003–2019.

Figure 3.

Drift potential rose for the study area for the period 2003–2019 (the black arrow indicates the resultant drift direction, RDD).

3.2. Analysis of Sand Dune Migration Speeds

In this study, the migration speeds of barchan sand dune were calculated by measuring the displacement at the toe of their leeward slopes. The average annual migration speeds were obtained by dividing the total displacement distance by the number of years. As shown in Table 3, the dune migration speeds in the study area exhibited significant variability. During phases P1 to P4, the annual average migration speeds were 12.81, 14.44, 10.84, and 13.64 m·a−1, respectively, indicating pronounced interannual fluctuations in dune migration. The overall average annual migration speed for dunes in the study area was 12.86 m·a−1, with a maximum speed of 22.85 m·a−1 and a minimum of only 2.3 m·a−1. Large dunes migrated relatively slowly, with an average annual speed of 11.27 m·a−1, while small to medium dunes exhibited higher speeds (13.84 m·a−1). The difference in migration speeds between these two dune types was most significant during phases P2 and P4, with differentials reaching 3.72 m·a−1 and 4.52 m·a−1, respectively. According to the dune migration intensity classification standard proposed by Zhu Zhenda (1966) [27] (>10 m·a−1), the dunes in this region fall into the rapidly migrating category. Based on Bagnold’s theory [28], dune migration speeds are proportional to the sand transport speeds, which themselves are proportional to the cube of the wind speed above the threshold for sand migration. However, the average dune migration speeds in the study area (P2 > P4 > P1 > P3) were not strictly proportional to the magnitude of the annual drift potential. Nevertheless, the migration direction was largely consistent with the resultant drift direction, indicating that the regional prevailing wind direction remained the dominant controlling factor. This discrepancy may arise from the modulating effects of local climatic conditions, vegetation cover, and other factors, further illustrating that dune dynamics result from the synthesis of multiple environmental influences. Consequently, a more in-depth analysis of the factors influencing dune migration speeds is warranted.

Table 3.

Sand dune migration speeds in the study area (m·a−1).

3.3. Analysis of Factors Influencing Sand Dune Migration

3.3.1. Identification of Key Influencing Factors

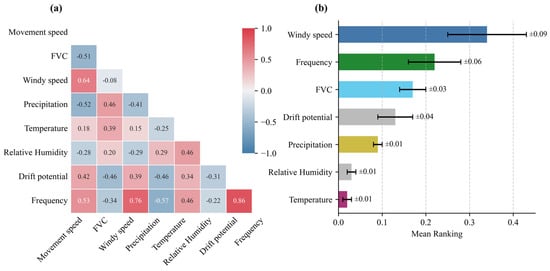

To quantify the influence of environmental factors on sand dune migration speeds, a combined approach of correlation analysis and Random Forest (RF) was employed to assess the impact of environmental factors on the migration speeds of barchan dunes (Figure 4). Correlation analysis revealed significant relationships between sand dune migration speeds and several environmental factors. Specifically, drift potential, wind speed, and sand-moving wind frequency were all positively correlated with sand dune migration speeds. Among these, wind speed exhibited a stronger correlation (p < 0.05). Conversely, precipitation and FVC showed significant negative correlations with sand dune migration speeds, indicating that vegetation cover and moisture conditions exert an inhibitory effect on sand dune activity. Air temperature and relative humidity did not show significant correlations with migration speeds, suggesting these factors have minimal direct influence on dune migration within the study area. Feature importance ranking based on the Random Forest algorithm further elucidated the relative contribution of each factor. Wind speed emerged as the most significant factor influencing migration speeds, with an importance value substantially higher than other factors (0.34 ± 0.09), which is consistent with the correlation analysis results. Sand-moving wind frequency (0.22 ± 0.06) and FVC (0.18 ± 0.03) ranked second and third, respectively. Notably, the feature importance of drift potential was markedly higher than anticipated based solely on simple correlation analysis. This discrepancy may stem from an interactive enhancement effect between drift potential and wind speed factors.

Figure 4.

Evaluation of various environmental factors affecting sand dune migration speeds. (a) Correlation analysis between various environmental factors and sand dune migration speeds; (b) importance ranking of environmental factors affecting sand dune migration speeds based on Random Forest analysis. Note: the “frequency” in the figure refers to the frequency of sand dune migration.

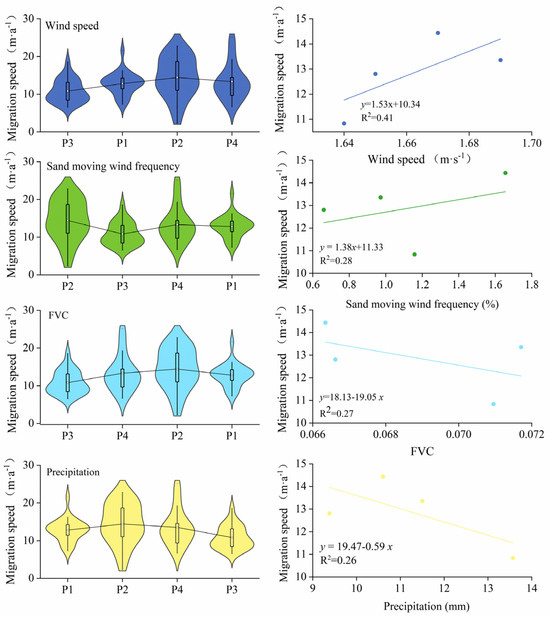

3.3.2. Effects of Key Factors on Sand Dune Migration Speed

Based on the results of the aforementioned analyses, we selected wind speed, sand-moving wind frequency, FVC, and precipitation to establish linear regression models with sand dune migration speeds (Figure 5). Significant positive relationships were observed between sand dune migration speeds and both wind speed and sand-moving wind frequency. Wind speed, in particular, exhibited a stronger fit (R2 = 0.41). This indicates that wind is the primary driving factor for dune migration. Specifically, the higher the wind speed, the faster the migration speed of sand particles; a higher frequency of sand-moving winds indicates more frequent aeolian activity, which in turn accelerates the overall migration speed of the dunes. This finding aligns with the conclusion of Yang et al. [29] in the Hobq Desert, although their reported fit for wind speed (R2 = 0.35) was lower than in the present study. Both FVC (R2 = 0.27) and precipitation (R2 = 0.26) exhibited negative effects on sand dune migration speeds. The former reduces migration speeds by lowering wind speed, trapping sand particles, and enhancing surface stability [17]. The latter suppresses sand migration by moistening the surface sand layer. These regression results are consistent with findings reported by [30] in the Taklamakan Desert.

Figure 5.

Linear regression of dune migration speed against key factors.

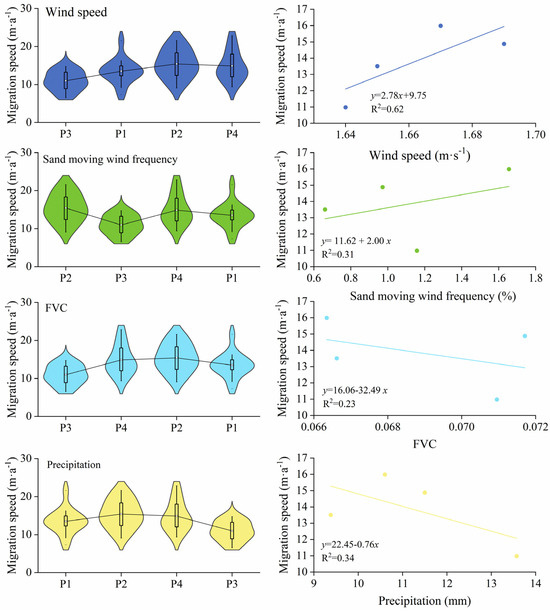

Given the influence of dune morphometric attributes on migration speed, large dunes (area > 9500 m2) were excluded from this specific analysis. The results (Figure 6) show that small to medium dunes exhibited greater sensitivity to environmental factors. The correlation between migration speeds of small to medium dunes and wind speed was significantly stronger (R2 = 0.62). This difference stems from the dynamic response related to dune morphology: smaller volumes make the windward faces of small to medium dunes more susceptible to wind shear stress, accelerating their overall migration. The correlation between migration speeds of small to medium dunes and precipitation was also significantly enhanced (R2 = 0.34). This is likely due to their limited water storage capacity, leading to heightened sensitivity to moisture content changes [31]. The inhibitory effect of FVC on the migration of small to medium dunes was largely consistent with its effect on large dunes. Overall, the influence of various environmental factors on dune migration differed significantly. However, analysis of individual factors was insufficient to fully reveal the interactions and synergistic effects among them.

Figure 6.

Linear regression of migration speed for small to medium dunes against key factors.

3.4. Future Evolution Trends of Sand Dune Migration Speed

The process of sand dune migration is synergistically regulated by multiple environmental factors, with various climatic elements collectively influencing migration characteristics through complex interactions. Against the backdrop of global climate change, phenomena such as rising temperatures, altered precipitation patterns, and increased frequency of extreme weather events will profoundly impact dune migration [32,33]. Over long timescales, the direct influence of temperature and humidity becomes particularly significant. Specifically, temperature and humidity indirectly affect sand dune migration speed by mediating surface moisture conditions and vegetation growth [34]. Consequently, a stepwise multiple regression analysis was employed to reveal the synergistic effects of climatic factors—including wind speed, precipitation, air temperature, and relative humidity—on sand dune migration speed, excluding variables such as drift potential and vegetation cover.

The stepwise regression results (Table 4) indicated that precipitation alone had limited explanatory power for sand dune migration speed (R2 = 0.325). However, the inclusion of wind speed significantly enhanced the model’s explanatory power to 0.65. This demonstrates a significant synergistic effect between wind speed and precipitation in arid regions. Mechanistically, wind speed primarily governs the threshold for sand particle entrainment and sediment transport flux, while precipitation alters sand erodibility by modulating the moisture content of surface sediments. Together, these factors constitute the primary driving system for sand dune migration [35,36]. As auxiliary factors such as air temperature and relative humidity were progressively introduced, the model’s explanatory power gradually increased to 0.69. The coefficient for air temperature shifted from positive to negative, reflecting its dual role: at lower temperatures, it maintains sand moisture by suppressing evaporation, while at higher temperatures, it accelerates soil desiccation and cracking, promoting sand migration. Relative humidity exhibited a negative effect, consistent with theoretical expectations [37,38].

Table 4.

Stepwise multiple regression of sand dune migration speed with environmental factors.

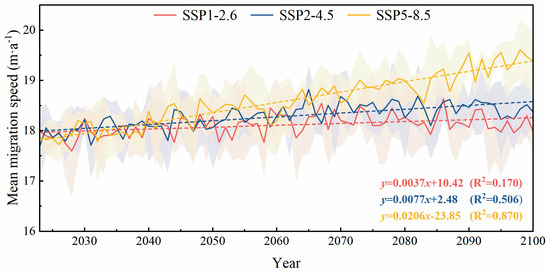

Based on CMIP6 future climate projections, this study utilized the stepwise multiple regression equation (y = 7.83 − 0.10 * Pre. + 3.12 * u + 0.25 * Ta)—selecting the model with minimal observational data error—to predict future evolution trends of sand dune migration speeds in the study area (Figure 7). Under the high-emission SSP5–8.5 scenario, sand dune migration speed exhibited the highest projected increase (R2 = 0.840). By 2100, the maximum migration speed is projected to reach 19.61 m·a−1, with an annual average speed of 18.59 m·a−1. This represents an increase of 5.78 m·a−1 compared to current levels, indicating a particularly pronounced acceleration trend under high-emission conditions. Specifically, under the SSP5–8.5 scenario, temperatures rise significantly, precipitation patterns fluctuate markedly, and wind speeds increase substantially—together enhancing sand-entrainment conditions and transport capacity, thereby accelerating sand dune migration. By contrast, under SSP1–2.6 and SSP2–4.5, changes in temperature and wind speed are much smaller and precipitation patterns remain relatively stable, producing comparatively modest changes in predicted dune migration speeds.

Figure 7.

Predicted changes in the annual movement speed of sand dunes on the western edge of the Kumtag Desert in the future (2020–2100) under three SSP scenarios based on the CMIP6 model. The shadow in the figure represents the standard error, and the dashed line represents the trend fitting line.

4. Conclusions

This study focuses on 24 typical sand dunes located on the western edge of the Kumtag Desert. By combining multi-temporal remote sensing imagery with meteorological observation data and employing the CMIP6 multi-model approach to predict future trends, the research systematically reveals the responses of sand dune migration to environmental factors and their future evolution characteristics. The results indicate that the study area is characterized by a low wind-energy environment, with significant interannual fluctuations in DP (0–26 VU). Sand-moving winds primarily originate from the W, WNW, and NW directions, which are highly consistent with the direction of sand dune migration. The average annual migration speed of the dunes is measured at 12.86 m·a−1, classifying them as a fast-moving type. The migration speed of small-to-medium sand dunes (13.84 m·a−1) is significantly higher than that of large sand dunes (11.27 m·a−1). Correlation and Random Forest analyses indicate that wind is the core factor influencing sand dune migration speed. Additionally, the frequency of sand-lifting winds and drift potential also significantly promote the migration of dunes. Conversely, precipitation and FVC demonstrate a negative effect on sand dune migration speed, highlighting the crucial role of moisture conditions and vegetation presence in stabilizing dune dynamics. Notably, the migration speed of small-to-medium sand dunes shows significant sensitivity to wind speed (R2 = 0.62) and precipitation (R2 = 0.34), emphasizing the complex interactions between environmental factors. The results of stepwise multiple regression based on climatic factors reveal a significant synergistic effect between wind speed and precipitation (R2 = 0.650), underscoring the dominant role of wind in arid regions.

The western edge of the Kumtag Desert is home to transmission lines and oil pipelines, which are severely threatened by wind activity, manifested as exposed pole foundations and accumulated sand along the pipeline. Using stepwise multiple regression combined with CMIP6 multi-model prediction, and assuming no substantial changes in vegetation or human interference, it is expected that the high-emission scenario (SSP5–8.5) will significantly accelerate sand dune migration, with an average migration speed of up to 19.61 m·a−1 by 2100. Therefore, we recommend using this value as a conservative engineering reference standard and combining it with local surveys for line protection and migration decisions. Thus enhancing the resilience of infrastructure while supporting regional ecological and sustainable development goals. It should be emphasized that the prediction framework relies on the current observation results and the stationarity of the statistical relationship between sand dune migration and environmental driving factors; long-term climate change and land-use change. Therefore, these predictions should be interpreted as trend warnings under current relationships, and future work should expand the sampling range and integrate dynamic vegetation wind sand coupling to improve the reliability of long-term predictions.

Author Contributions

F.Y.: Resources, Writing—Original Draft, Project Administration, Investigation. S.A. (Silaian Abudukade): Data Curation, Writing—Review and Editing. L.X.: Formal Analysis, Supervision. A.S. (Akida Salam): Writing—Review and Editing, Visualization. X.Y.: Software, Resources, Supervision. W.H.: Project Administration, Supervision, Conceptualization. A.M.: Project Administration, Supervision, Resources. X.Z.: Formal Analysis, Funding Acquisition. Y.L.: Methodology, Visualization. C.Z.: Resources, Supervision. M.M.: Project Administration, Supervision. F.Z.: Supervision, Software. C.W.: Project Administration, Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was jointly supported by the Scientific and Technological Innovation Team (Tianshan Innovation Team) project (2022TSYCTD0007), the Youth Innovation Team of China Meteorological Administration (CMA2024QN13), the Tianshan Talent Project of Xinjiang (2023TSYCCX0075), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2022MD723851), and the S&T Development Fund of CAMS (2021KJ034).

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to all authors who contributed directly or indirectly to this research.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare that there are no competing financial interests.

References

- Schueth, J.; Laycock, D. The Search for the World’s Fastest Sand Dune: Using Google Earth Historical Imagery to Measure Sand Dune Migration rates. SSRN Electron. J. 2022, 4062731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochanski, K.; Mohan, D.; Horrall, J.; Rountree, B.; Abdulla, G. Deep Learning Predictions of Sand Dune Migration. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.10798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokarram, M.; Pham, T.M. Predicting Dune Migration Risks under Climate Change Context: A Hybrid Approach Combining Machine Learning, Deep Learning, and Remote Sensing Indices. J. Arid. Environ. 2025, 231, 105447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinske, A.A. Criteria for determining sand-transport by surface-creep and saltation. Eos. Trans. AGU 1942, 23, 639–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Dong, Z.; Hu, G.; Parteli, E.J.R. Migration and Morphology of Asymmetric Barchans in the Central Hexi Corridor of Northwest China. Geosciences 2018, 8, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daudon, C.; Beyers, M.; Jackson, D.; Avouac, J.P. Prediction of barchan dunes migration using climatic models and speed-up effect of dune topography on air flow. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2024, 648, 119049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, N.; Zhang, D.; Gao, B.; Weng, X.; Qiu, H. Yardang-controlled dune morphology and dynamics in the Qaidam Basin: Insight from remote sensing and numerical simulations. Catena 2024, 235, 107697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Dong, Z.; Wu, G. Field observations of sand transport over the crest of a transverse dune in northwestern China Tengger Desert. Soil Tillage Res. 2017, 166, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biabani, L.; Khosravi, H.; Zehtabian, G.; Haydari Alamdarloo, E.; Rayegani, B. Forecasting the Impact of Climatic Factors on Sand Dune Mobility in the Salt Lake Basin using Sensitivity Analysis. Desert 2024, 29, 97954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, M.; Boesl, F.; Brückner, H. Migration of Barchan Dunes in Qatar–Controls of the Shamal, Teleconnections, Sea-Level Changes and Human Impact. Geosciences 2018, 8, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Dong, Z.; Qian, G.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, A. Monitoring of Sand Dune Migration Speed and Analysis of Influencing Factors Along the Yellow River Based on Drone Technology. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2021, 37, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Chu, L.; Daryanto, S.; Lü, L.; Ala, M.; Wang, L. Sand Dune Stabilization Changes the Vegetation Characteristics and Soil Seed Bank and Their Correlations with Environmental Factors. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 648, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesse, P.P.; Telfer, M.W.; Farebrother, W. Complexity confers stability: Climate variability, vegetation response and sand transport on longitudinal sand dune in Australia’s deserts. Aeolian Res. 2017, 25, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.M.A.; Novellino, A.; Hussain, E.; Marsh, S.; Smith, M. The Use of SAR Offset Tracking for Detecting Sand Dune Migration in Sudan. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Mason, J.A.; Lu, H. Vegetated dune morphodynamics during recent stabilization of the Mu Us dune field, north-central China. Geomorphology 2015, 228, 486–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Liang, P.; Yang, X.; Li, H. The control of wind strength on the barchan to parabolic dune transition. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2020, 45, 2300–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörwald, L.; Lehmkuhl, F.; Walk, J.; Delobel, L.; Boemke, B.; Baas, A.; Zhang, D.; Yang, X.; Stauch, G. Dune migration under climatic changes on the north-eastern Tibetan Plateau as recorded by long-term satellite observation versus ERA-5 reanalysis. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2023, 48, 2613–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinsin, T.; Mounir, F.; El Aboudi, A. Modeling and assessing driving factors of the spatial and temporal dynamics of the sand dune in the district of Errachidia, Morocco. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megahed, H.; Farrag, A.; GabAllah, H.; AbdelRahman, M.; Badawy, R. Develop of a machine learning model to evaluate the hazards of sand dune. Earth Sci. Inform. 2024, 17, 4001–4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiyare, S.; Mao, D.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, F.; Zan, M. Characteristics of Wind Conditions and Sand Dune Migration Patterns on the Western Edge of the Kumtag Desert. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2021, 35, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Qian, G.; Dong, Z.; Tian, M.; Lu, J. Migration of barchan dunes and factors that influence migration in the Sanlongsha dune field of the northern Kumtagh Sand Sea, China. Geomorphology 2021, 378, 107615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Qu, J.; Qian, G.; Zhang, Z. Aeolian Geomorphological Regionalization of the Kumtagh Desert. J. Desert Res. 2011, 31, 805–814. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Dong, Z.; Zhao, A.; Qian, G. Characteristics of Aeolian Activity in the Kumtag Desert. Arid Zone Geogr. 2010, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryberger, S.G. Dunes Forms and Wind Regime. In A Study of Global Sand Seas; USGS Professional Paper 1052; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, G.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, M.; Shang, L. Characteristics of Wind Conditions and Sand Transport in the Zoige Basin. J. Desert Res. 2020, 40, 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Zhang, W.; Shen, W.; Xiao, T.; Zhang, Y. China Regional 250 m Fractional Vegetation Cover Data Set (2000–2024); National Tibetan Plateau/Third Pole Environment Data Center: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Zhu, Z.; Wu, Z.; Li, J.; Chen, Z.; Wu, G.; Li, B. A Study on the Aeolian Landforms of the Taklamakan Desert. Chin. Sci. Bull. 1966, 1, 620–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnold, R.A. The Physics of Blown Sand and Desert Dunes; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1942. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Cao, J.; Hou, X. Characteristics of Aeolian Dune, Wind Regime and Sand Transport in Hobq Desert, China. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 5543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Gao, X. Migration Characteristics of Crescent-shaped Dunes at the Southern Edge of the Taklamakan Desert. Arid Zone Res. 2024, 41, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, S.; Jin-Chao, F. Spatiotemporal change of water content in the sand dune soil—A case study in dabqig (Uxin Qi), a town in semiarid region. J. Yunnan Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2010, 32, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baas, A.; Delobel, L. Desert dunes transformed by end-of-century changes in wind climate. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 999–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Miao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Q.; Gao, L. Extreme Wind Events in China over the Past 50 Years and Their Impact on the Changes of Dust Storms. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 10, 1058275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Duan, L.; Tong, X.; Liu, T.; Wang, G.; Zhang, L. Simulation and partition evapotranspiration for the representative landform-soil-vegetation formations in Horqin Sandy Land, China. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2020, 140, 1221–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.Y.; Skidmore, E.; Hasi, E.; Wagner, L.; Tatarko, J. Dune sand transport as influenced by wind directions, speed and frequencies in the Ordos Plateau, China. Geomorphology 2005, 67, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhang, C.; Huang, X.; Wang, X.; Cen, S. The effect of wind speed averaging time on sand transport estimates. Catena 2019, 175, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Chen, J.; Zheng, X.; Xue, J.; Miao, C.; Du, Q.; Xu, Y. Effect of Sand Mulches of Different Particle Sizes on Soil Evaporation during the Freeze–Thaw Period. Water 2018, 10, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelis, W.M.; Gabriels, D. The effect of surface moisture on the entrainment of dune sand by wind: An evaluation of selected models. Sedimentology 2003, 50, 771–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).