Abstract

The accelerating global urbanization process has posed new challenges to urban planning. With the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) technology, the application of AI in urban planning has gradually emerged as a prominent research focus. This study systematically reviews the current state, development trends, and challenges of AI applications in urban planning through a combination of bibliometric analysis using Citespace, AI-assisted reading based on generative models, and predictive analysis via support vector machine (SVM) algorithms. The findings reveal the following: (1) The application of AI in urban planning has undergone three stages—namely, the budding stage (January 1984 to January 2017), the rapid development stage (January 2017 to January 2023), and the explosive growth stage (January 2023 to January 2025). (2) Research hotspots have shifted from early-stage basic data integration and fundamental technology exploration to a continuous fusion and iteration of foundational and emerging technologies. (3) Globally, China, the United States, and India are the leading contributors to research in this field, with inter-country collaborations demonstrating regional clustering. (4) High-frequency keywords such as “deep learning,” “machine learning,” and “smart city” are prevalent in the literature, reflecting the application of AI technologies across both macro and micro urban planning scenarios. (5) Based on current research and predictive analysis, the application scenarios of technologies like deep learning and machine learning are expected to continue expanding. At the same time, emerging technologies, including generative AI and explainable AI, are also projected to become focal points of future research. This study offers a technical application guide for urban planning, promotes the scientific integration of AI technologies within the field, and provides both theoretical support and practical guidance for achieving efficient and sustainable urban development.

1. Introduction

The concept of artificial intelligence (AI) was first conceptualized in 1942 and has traversed multiple evolutionary stages [1] while achieving extensive implementation across diverse disciplines [2,3,4,5,6]. In urban planning, the development has evolved from the early adoption of CAD, GIS, and BIM technologies to the continuous development of algorithms, including machine learning and deep learning. Today, breakthroughs driven by the Fourth Industrial Revolution, along with the emergence of generative AI and explainable AI, have provided new opportunities for the transformation and innovation of urban planning [1,6]. Currently, AI technologies have been applied in various domains of urban planning, including transportation system optimization [7,8,9,10,11], land use and spatial design [12,13,14,15,16,17], environmental and energy management [18,19,20,21,22,23], and public health and safety [24,25,26,27,28,29]. However, significant challenges and bottlenecks remain in areas such as cross-scale urban system integration [30,31,32,33,34,35], technological inclusiveness and adaptability [36,37,38,39,40], and the alignment of theory and policy [38,41,42], mainly due to the lack of effective coordination of AI technologies at the macro level. With the intensification of urbanization, problems such as environmental degradation and traffic congestion have become increasingly prominent [43,44], and urban issues are growing more diverse and complex. As urbanization rates continue to rise [45,46] and living standards improve, urban planning demands a higher quantity, efficiency, and accuracy of data processing [47,48,49,50]. Integrating planning, construction, management, and operation has become an inevitable trend in urban planning. Traditional planning approaches do not address increasingly complex, dynamic, and refined urban problems. Overcoming the limitations of experience-based planning and data constraints has become imperative, and AI technologies are now essential for driving reform and transformation in urban planning [50,51,52].

Current review studies predominantly focus on sector-specific AI applications, with limited comprehensive analyses addressing macro-scale integration. The existing literature remains fragmented, typically concentrating on discrete sectors such as transportation or climate mitigation, failing to provide strategic guidance for holistic AI implementation in urban planning. Furthermore, with continuous breakthroughs in existing AI technologies and the emergence of new ones under the backdrop of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, the application of AI in urban planning has expanded rapidly and iteratively in recent years. There is an urgent need to systematically reassess the current landscape and provide scientifically grounded references for advancing the field. To establish the analytical framework of this study and ensure that the results of bibliometric analysis can be transformed into substantive insights into planning practices, it is necessary to first clarify the main research objects of artificial intelligence technology, the core dimensions of concern in modern urban planning practices, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

A Framework of Core Dimensions in Urban Planning Practice and Corresponding AI Applications.

This study innovatively establishes a comprehensive analytical framework encompassing AI’s full-cycle development in urban planning. It conducts a thorough and systematic review of existing research on AI and urban planning, and offers well-grounded forecasts regarding future directions in the field. The study provides scientific guidance for the discipline, providing both forward-looking and practical significance. Methodologically, it is also innovative in applying generative AI to academic research. AI tools optimize retrieval processes, assist in the literature data collection, and enable efficient reading, data statistics, and information synthesis, offering a new approach to the academic application of AI technologies [53].

This paper aims to investigate and address the following key research questions, thereby offering guidance for the field’s development:

(1) What are the current stages of development, research networks and distributions, research hotspots, and the technical application status of AI in urban planning?

(2) What are the future trends, potential hotspots, and challenges of AI in urban planning? What key issues will future research address, and what development goals are expected to be achieved?

(3) How can we better leverage AI technologies to advance urban planning in the future?

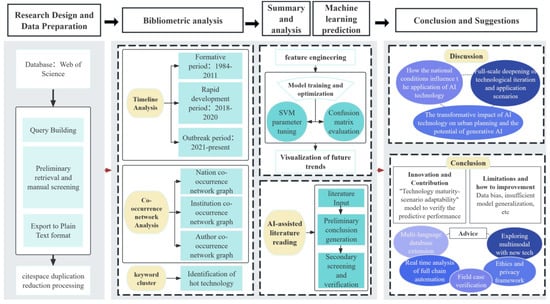

The research framework for this study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research Technology Roadmap.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

The data for this study were obtained from the Web of Science Core Collection. The retrieval was conducted on 20 March 2025, covering the period from January 1984 to January 2025. The selected document types included articles, proceedings papers, and review articles. The covered disciplines spanned Engineering, Electrical, Electronic, Computer Science, Information Systems, Artificial Intelligence, Remote Sensing, Environmental Science, Urban Studies, Architecture, Urban Planning, and Construction Building Technology. We employed eight AI platforms (DeepSeek-V3, GPT-4o-mini, Claude-3.5-Haiku, Gemini-2.0-Flash, Llama-3.2-90B, Kimi, Wenxin Yiyan, and Doubao) to screen and refine keywords comprehensively (a summary of keyword frequencies is provided in Table 1). Based on this, the final search query was defined as follows:

TS = ((“Urban Planning” OR “City Planning” OR “Spatial Planning” OR “Regional Planning” OR “Urban Design” OR “Smart City” OR “Intelligent City” OR “Digital City”) AND (“Artificial Intelligence” OR “AI” OR “Machine Learning” OR “Deep Learning” OR “Computer Vision”)) NOT TS = (“Medical” OR “Agriculture” OR “Rural Development” OR “Environmental Planning”)

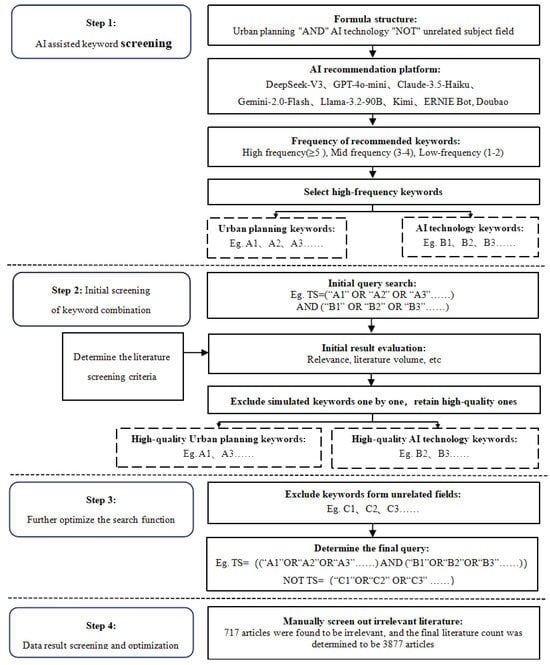

This search initially yielded 4594 records. After manually reviewing titles, keywords, and abstracts, 717 records that were irrelevant to the research topic were excluded (the inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed in Table 2). Ultimately, 3877 documents were identified as the final dataset for this study (the retrieval process is illustrated in Figure 2).

Table 2.

Summary of High-Frequency Key Vocabulary.

Figure 2.

Literature Screening and Data Collection Process.

2.2. Research Methods

2.2.1. Bibliometric Analysis Using CiteSpace

Following the determination of the literature sample, this study employed CiteSpace 6.4R1 (64-bit)—one of the most widely used tools for bibliometric analysis—for data analysis and visual representation [54,55]. After cleaning the previously retrieved dataset of 3877 publications using CiteSpace, 1394 records were excluded due to incomplete information or incompatibility with the platform. As a result, 2483 documents were included in the bibliometric analysis. The time-slicing interval was set to one year. Relevant analysis fields (authors, institutions, and keywords) were selected based on specific research questions. Visual analysis was conducted using “Timeline View” and “Clustering.” This study used the Timeline View and Burst Detection functions to divide the development stages; employed co-occurrence analysis to identify research networks and characteristics at the national, institutional, and author levels; and conducted keyword clustering analysis to summarize research themes, hotspots, and key technologies.

2.2.2. Literature Review and Data Analysis Assisted by Generative AI

This study employed generative AI tools—represented by platforms such as ChatGPT and DeepSeek [56]—to assist in the reading and analyzing of 3877 documents. By inputting full-text data exported from the Web of Science database and setting task-specific conditions based on the research objectives, the AI-generated textual outputs were further refined and summarized to derive research conclusions. For instance, relevant national-level datasets exported from the Web of Science were used to understand the research landscape of specific countries, and prompts such as “summarize the main research directions, application scenarios, and research characteristics of this country” were given. The reliability of the AI-generated output was then verified through targeted sampling of the source data and rapid keyword-based abstract reviews. This output was subsequently refined manually to achieve the research objectives. In this process, AI served solely as an analytical aid; all data sourcing and final conclusions were determined by the researchers. This approach harnessed the efficiency of AI while retaining essential human oversight, significantly enhancing the literature analysis, reducing the subjectivity associated with manual reading, and overcoming limitations of traditional review methods, thereby improving the reliability and evidential basis of the research findings.

2.2.3. Keyword Prediction and Trend Analysis Based on Support Vector

This study employs a Support Vector Machine (SVM) model with a Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel (Equation (1) [57]) to classify and predict future keywords. In Equation (1), K(x(i), x(j)) represents the kernel function, and (gamma) denotes the characteristic width of the RBF. The penalty parameter CCC is applied to minimize classification error, and a grid search method is used to optimize parameters and enhance model performance [58].

The predictability of keywords is evaluated based on multiple factors such as author characteristics and paper attributes [59] to forecast trends in keyword usage. The input data consists of an Excel file (Table 3) containing multiple predictor variables, where all non-numerical variables are converted into binary (0 or 1) numerical formats. The target variable, Citedmore, is classified into two non-numeric codes: CM (highly cited) and N (not highly cited).

Table 3.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Literature Screening.

The predictor variable data are sourced from the Web of Science (WOS). Considering the rapid development of AI technologies in urban planning in 2025, with a significant increase in publication volume and expanded technical and application scopes, this study adds 220 publications from January 2025 to the retrieval date of 20 March 2025, to the initial dataset of 3877 documents (ending January 2025). The final dataset used for machine learning prediction comprises 4097 documents. The citation thresholds are defined as follows: moderately cited papers are those cited between 1 and 10 times, while highly cited papers have a citation count of 15 or more [60,61].

The model’s accuracy in predicting the target variable is evaluated using a confusion matrix (Equation (2)). Cross-validation is employed to divide the dataset into training and test sets to assess the stability of model accuracy. Specifically, 15-fold cross-validation is selected due to its superior performance in model evaluation [62]. In this approach, the dataset is partitioned into 15 subsets; in each iteration, 14 subsets are used for training and 1 is used for testing, with the process repeated 15 times to ensure that each subset serves as the test set once. This procedure ensures consistency in model training.

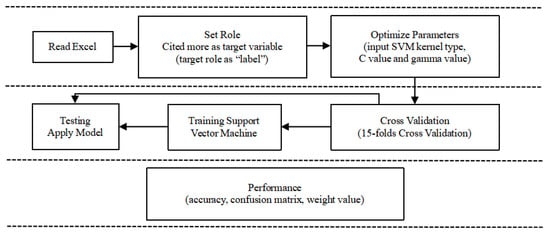

The SVM analysis results reflect the variables’ contribution to classification prediction through weight values (w). A positive weight indicates a positive correlation between the variable and the prediction outcome, while a negative weight suggests a negative correlation [63]. The larger the absolute value of the weight, the more significant the corresponding keyword is likely to be in future research [64]. Figure 3 illustrates the specific operational procedure of applying Python’s support vector machine (SVM) method.

Figure 3.

SVM specific operation flowchart [61].

3. Results

3.1. Evolution of Development Stages

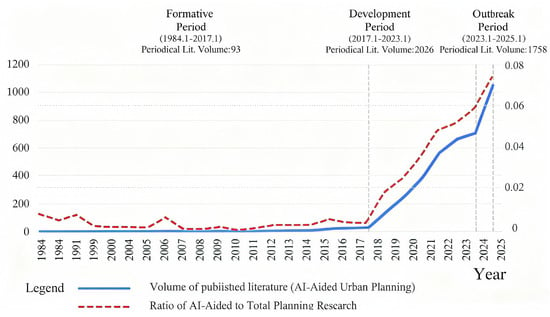

To gain a preliminary understanding of the developmental trajectory of the “application of AI technologies in urban planning,” a comprehensive analysis of the literature data was conducted. Findings indicate that since AI technologies were first applied in urban planning in 1984 [65], the evolution of this field—based on the annual volume of publications, research directions, and core technologies—can be broadly divided into three stages: the embryonic stage (January 1984–January 2017), the development stage (January 2017–January 2023), and the explosive growth stage (January 2023–January 2025). Notably, The number of publications in the two-year explosive growth stage was 3.6 times that of the previous 39 years combined (in Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Development

Through the analysis of the literature data across stages, the research hotspots and developmental characteristics of each phase are further elucidated as follows:

- Stage I The embryonic stage. (January 1984–January 2017)

This period marked the embryonic stage of the field, with 120 relevant publications. In 1984, Barath first put forward a visionary concept of a “regional planning system integrated with artificial intelligence principles” [65]. Though sustained research productivity did not emerge until after 2004. The 1990s witnessed the introduction of pivotal algorithms such as support vector machines (SVMs) and Boosting, which enabled substantial advancements in machine learning theory and practice, leading to the initial deployment of AI technologies in urban planning contexts [66,67,68,69,70,71,72], with a particular focus on data collection methodologies and technical dimensions [73,74,75,76]. The early 21st century witnessed the proliferation of electronic devices and the rapid development of the Internet, providing a broader range of application scenarios for technologies such as machine learning. Research directions shifted from algorithmic theory toward applied development, including domains such as computer vision. Toward the end of this phase, a significant breakthrough was achieved by Alex Krizhevsky in the ImageNet competition through the implementation of convolutional neural networks (CNNs), signaling the onset of the rapid development of deep learning. By the 2010s, deep learning had achieved state-of-the-art performance in speech recognition, image processing, and natural language processing, solidifying its status as a core AI discipline and inaugurating a new era of accelerated progress.

- Stage II Rapid Development Phase (January 2017–January 2023)

This stage was marked by a surge in scholarly output, with 770 publications contributing to the body of knowledge. Since 2018, the annual volume of publications rose sharply from approximately 20 in the preceding three years to 142, with a three-year trend of exponential growth. The concept of the “smart city” gained increasing traction and visibility [77,78,79], and urban planning began to receive significant attention [51]. The “Internet of Things (IoT)”, which emerged as a research hotspot at the end of the first stage, continued to demonstrate robust developmental momentum [80,81]. New research themes such as the “smart grid” [82,83] and “green space” [84,85] emerged [86,87,88], indicating that urban development was increasingly oriented toward digitization and sustainability across diverse application scenarios. Technologies such as “image segmentation”, “scene classification”, and “space syntax” also matured during this phase [12,89], and remote sensing technologies became more widely adopted [90,91,92]. “Machine learning” remained the core of AI technologies and continued to evolve, with deep learning based on multi-layer neural networks achieving particularly prominent results in this phase.

The 2020 COVID-19 pandemic served as a critical inflection point, amplifying national imperatives for optimized emergency resource allocation and accelerating the practical implementation of AI-driven solutions to enhance productivity [93]. This urgency catalyzed breakthroughs in nascent fields such as large language models and generative AI, which transitioned from theoretical inquiry to operational reality within a short timeframe [51,94], thereby redefining the research landscape at the AI–urban planning interface.

- Stage III Explosive Growth Phase (January 2023–January 2025)

This period marks the explosive growth phase, characterized by the publication of 3207 relevant articles. The field has witnessed a surge in the literature output, with 220 publications produced in less than the first four months of 2025 alone, representing an approximate 400% year-on-year increase compared to the same period in 2024 (1 January–20 March). New urban planning paradigms such as “service-oriented cities”, “healthy cities”, “green cities”, and “people-centered cities” have emerged in this phase [9,95,96,97]. Concurrently, as traditional AI technologies continued to develop at an unprecedented pace, emerging technologies such as “explainable AI” [98], “generative AI” [14,99,100], and “large language models” [100,101] gained prominence. These innovations have offered new perspectives for applying AI in urban planning. For example, integrating advanced AI language models such as ChatGPT has significantly enhanced environmental monitoring and urban planning initiatives [102].

At the same time, in order to more accurately reflect the development status since the application of artificial intelligence in urban planning, according to Figure 2 and Figure 3, it can also be concluded that the proportion of artificial intelligence topics in urban planning-themed papers has changed, which is basically consistent with the three stages of development trends in publication volume mentioned earlier. From January 1984 to January 2017, the proportion was almost zero, but since 2017, with the rapid development of the artificial intelligence field, the proportion has also risen rapidly, with an average annual growth rate of nearly 1%, reaching around 6% by the end of 2022. After 2023, it will be even faster, and based on existing data, it is estimated that the average annual growth rate will double.

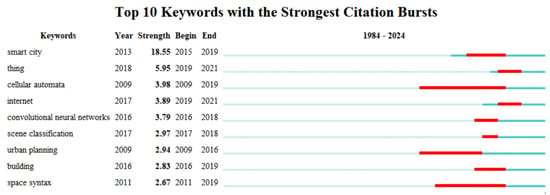

Finally, a burst term analysis was conducted on the literature from January 1984 to January 2025 (Figure 5). Overall, the number of burst terms was relatively limited. Early research was relatively theoretical. The earliest burst terms, “urban planning” and “cellular automata,” emerged in 2009, with durations of 7 years and 10 years, respectively, and moderate burst intensities, reflecting the long-term, incremental optimization of technologies and the relative stability of research themes. “Cellular automata” have been widely applied in analyzing complex urban planning datasets from multiple sources and can serve as pre-processing or post-processing tools for machine learning. This makes them a critical foundation for the deep integration and development of AI technologies within urban planning. In 2011, the term “space syntax” emerged, introducing a new demand in urban planning by revealing the influence of architectural and urban forms on social behavior through quantitative analysis of topological, geometric, and spatial relationships. In 2015, the concept of the “smart city” entered the view of a growing number of urban planning researchers, and the application of AI technologies in urban planning rapidly began to deepen. The emergence of burst terms such as “scene classification” and “convolutional neural network” in 2016 and 2017 reflected a further deepening of research directions and technologies during the rapid development phase, particularly in scenario-based applications. No burst terms have yet been identified in the explosive growth phase, which may be attributable to this period’s relatively short time span. However, it also reflects the trend toward a more focused and fine-grained research landscape during this stage, in contrast with earlier periods.

Figure 5.

Visualization of Mutation Words from 1984 to 2024.

In summary, beyond the significant increase in publication volume, the research on the application of AI technologies in urban planning has evolved from generalized technological exploration to scenario-specific technological adaptation, and subsequently to value-oriented technological innovation. This progression has gradually formed an integrated research framework encompassing technology, scenario, and objective dimensions. AI technologies in urban planning demonstrate a promising development trajectory and broad application prospects, and are expected to remain a focal point of scholarly attention for the foreseeable future.

3.2. Research Network Analysis

3.2.1. National Research Network Analysis

- 1.

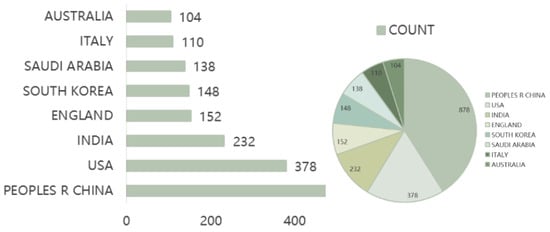

- Ranking of National Research OutputThe number of publications from each country was compiled by analyzing the countries of origin for data within the literature database (Figure 6). The analysis revealed that China (PEOPLES R CHINA) has produced the most significant volume of research in the field of “the application of AI technologies in urban planning,” with a total of 878 publications, accounting for approximately 35% of all publications (joint publications by multiple countries were counted only once). The United States (USA) ranked second with 378 publications, comprising about 15%. Other countries with a relatively abundant research output include India (INDIA) with 232 publications, England (ENGLAND) with 152, South Korea (SOUTH KOREA) with 148, Saudi Arabia (SAUDI ARABIA) with 138, Italy (ITALY) with 110, Canada (CANADA) with 109, and Australia (AUSTRALIA) with 104. All remaining countries each contributed fewer than 100 publications.

Figure 6. Number and proportion of published literature in each country (multi-country collaborative literature participating in multiple calculations).To more scientifically evaluate the research situation in different countries/regions, we normalized it by combining economic and scientific research scale indicators. Specifically, based on the population (2023), GDP (2023) and the proportion of R&D expenditure in GDP (the latest available data) published by the World Bank, the number of articles per million people, the number of GDP articles per trillion dollars and the corresponding number of articles per unit of R&D expenditure (estimated value) are calculated. The standardized results of some major countries/regions are shown in Table 4.

Figure 6. Number and proportion of published literature in each country (multi-country collaborative literature participating in multiple calculations).To more scientifically evaluate the research situation in different countries/regions, we normalized it by combining economic and scientific research scale indicators. Specifically, based on the population (2023), GDP (2023) and the proportion of R&D expenditure in GDP (the latest available data) published by the World Bank, the number of articles per million people, the number of GDP articles per trillion dollars and the corresponding number of articles per unit of R&D expenditure (estimated value) are calculated. The standardized results of some major countries/regions are shown in Table 4. Table 4. Standardized Comparison of Research Output by Country/Region.Continuing to analyze Table 4, it can be seen that although China leads in the original publication volume, after normalizing population and GDP, its research density is lower than that of countries such as the United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia, and South Korea. Saudi Arabia and South Korea have outstanding performance in the unit R&D expenditure output index, followed by the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. China has a moderate performance, while India has the lowest.

Table 4. Standardized Comparison of Research Output by Country/Region.Continuing to analyze Table 4, it can be seen that although China leads in the original publication volume, after normalizing population and GDP, its research density is lower than that of countries such as the United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia, and South Korea. Saudi Arabia and South Korea have outstanding performance in the unit R&D expenditure output index, followed by the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. China has a moderate performance, while India has the lowest. - 2.

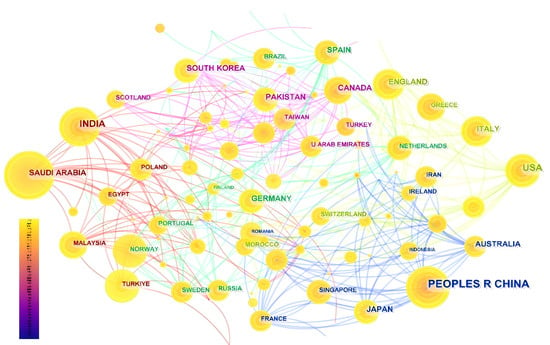

- National Collaboration NetworkCollaborative relationships among researchers from different countries were evident. A country co-occurrence analysis was conducted to construct a national collaboration network (Figure 7), thereby uncovering patterns of international collaboration.

Figure 7. National Cooperation Network.Globally, China has the closest collaboration with Japan, co-authoring 71 publications, accounting for approximately 3% of the global population. These publications represent 8% and 92% of China’s and Japan’s total outputs. Other bilateral collaborations with more than 10 co-authored publications include England and Switzerland (24 publications), Spain and Germany (21 publications), the United Arab Emirates and Canada (16 publications), Saudi Arabia and Malaysia (15 publications), Saudi Arabia and India (13 publications), the United States and Switzerland (13 publications), and Australia and England (12 publications). The analysis shows that China collaborates frequently with East and Southeast Asian countries, but has relatively fewer collaborations with Western countries, with powerful ties to Japan. The United States has a more dispersed collaboration pattern across Europe and Asia, with modest collaboration volumes with Switzerland (13 publications), the United Kingdom (8 publications), Israel (8 publications), and several other European nations. The UK collaborates mainly with European countries, with Australia as a notable exception. Saudi Arabia and the UAE maintain extensive collaborations spanning Europe and Asia, with significant geographic breadth. Switzerland primarily collaborates with Western countries and maintains many co-authored publications. Overall, international collaboration exhibits a cluster-based tendency; however, leading publishing countries tend to cooperate less with one another. This suggests that national conditions and geographic proximity significantly influence such collaboration.

Figure 7. National Cooperation Network.Globally, China has the closest collaboration with Japan, co-authoring 71 publications, accounting for approximately 3% of the global population. These publications represent 8% and 92% of China’s and Japan’s total outputs. Other bilateral collaborations with more than 10 co-authored publications include England and Switzerland (24 publications), Spain and Germany (21 publications), the United Arab Emirates and Canada (16 publications), Saudi Arabia and Malaysia (15 publications), Saudi Arabia and India (13 publications), the United States and Switzerland (13 publications), and Australia and England (12 publications). The analysis shows that China collaborates frequently with East and Southeast Asian countries, but has relatively fewer collaborations with Western countries, with powerful ties to Japan. The United States has a more dispersed collaboration pattern across Europe and Asia, with modest collaboration volumes with Switzerland (13 publications), the United Kingdom (8 publications), Israel (8 publications), and several other European nations. The UK collaborates mainly with European countries, with Australia as a notable exception. Saudi Arabia and the UAE maintain extensive collaborations spanning Europe and Asia, with significant geographic breadth. Switzerland primarily collaborates with Western countries and maintains many co-authored publications. Overall, international collaboration exhibits a cluster-based tendency; however, leading publishing countries tend to cooperate less with one another. This suggests that national conditions and geographic proximity significantly influence such collaboration. - 3.

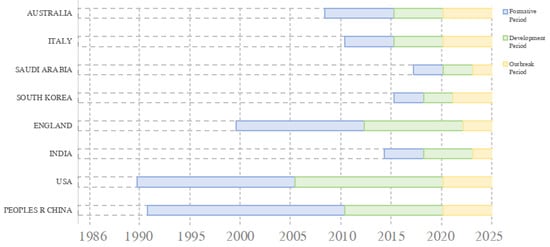

- National Research CharacteristicsA data analysis and content review were conducted on countries with more than 100 publications to understand each country’s research profile. These countries’ developmental trajectories can be broadly categorized as shown in Figure 8. Most countries progress from foundational AI technologies to complex system integration, eventually focusing on sustainability, ethics, and brilliant processes. This evolution is typically demonstrated as follows: in the emergence phase, there is basic technical exploration and initial policy planning, with a low volume of publications; in the rapid development phase, research becomes more specialized and scenario-oriented, accompanied by systematic policy frameworks and a significant increase in publication volume; in the explosive growth phase, cutting-edge technologies such as generative AI and digital twins emerge rapidly, full-process applications are deepened, and the integration with national policy and strategic frameworks becomes more prominent.

Figure 8. Research History of Top Ten Ranked Countries.

Figure 8. Research History of Top Ten Ranked Countries.

A summary of national research characteristics is provided in Table 5. It is evident that, beyond differences in development speeds, which are strongly correlated with national economic development levels, each country also displays specific preferences in research directions across different phases, often closely aligned with policy orientations. For instance, China’s Smart City Pilot Policy [103] and the New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan (2016) [104] directly accelerated the application of deep learning and digital twin technologies in traffic forecasting and urban microclimate simulation. The United States, through its National Artificial Intelligence Research and Development Strategic Plan (2019 Update) [105], emphasized the integration of data-driven decision-making and ethical governance [106], which facilitated the deployment of computer vision in streetscape analysis [107] and crime monitoring [108]. These examples highlight the strong linkage between the technical emphases and development patterns of AI in urban planning and the release of corresponding national policies.

Table 5.

Literature screening process.

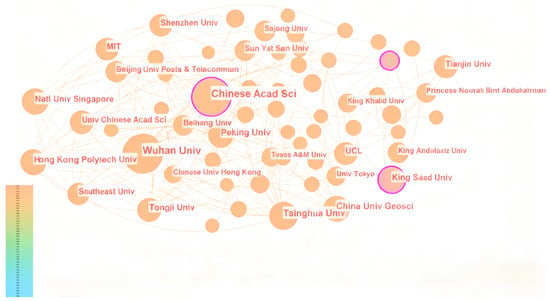

3.2.2. Institutional Research Network Analysis

This section follows a macro-level analysis of the national research landscape and further explores individual institutions’ publication performance. CiteSpace was employed to visualize the institutional collaboration network (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Institutional Cooperation Network.

The top ten institutions by publication volume are presented in Table 6. Wuhan University recorded the highest number of publications, totaling 63, among all research institutions. The remaining top-ranking institutions, ordered by publication volume, are as follows: Chinese Academy of Sciences (59 publications); University of Hong Kong (34 publications); Tsinghua University (34 publications); China University of Geosciences (31 publications); Hong Kong Polytechnic University (30 publications); Peking University (29 publications); National University of Singapore (28 publications); King Saud University (28 publications); and Tongji University (26 publications).

Table 6.

SVM Data Input and Source.

It is evident that research institutions based in China consistently produce high volumes of scholarly publications in this field. Notably, 80% of the top ten institutions worldwide in terms of publication volume are in China.

The analysis of high-yield research institutions not only needs to focus on the number of publications, but it also needs to be interpreted in conjunction with the city type and research focus of their location, avoiding inferring the influence of institutions solely based on counting. Table 7 analyzes several representative institutions in Table 8.

Table 7.

Research Profiles of Leading Institutions in AI for Urban Planning.

Table 8.

Top Institutions by Publication Volume.

According to Table 7, the research direction of the institution is highly correlated with the urban characteristics and core challenges it faces in its location. For example, research by Chinese institutions extensively covers various urban scales and issues, with Wuhan focusing on flood simulation due to its abundant water resources, and Hong Kong focusing on high-density urban morphology research due to insufficient land use; however, institutional research in Saudi Arabia and Singapore focuses more on responding to their unique resource and environmental constraints or national smart city strategies.

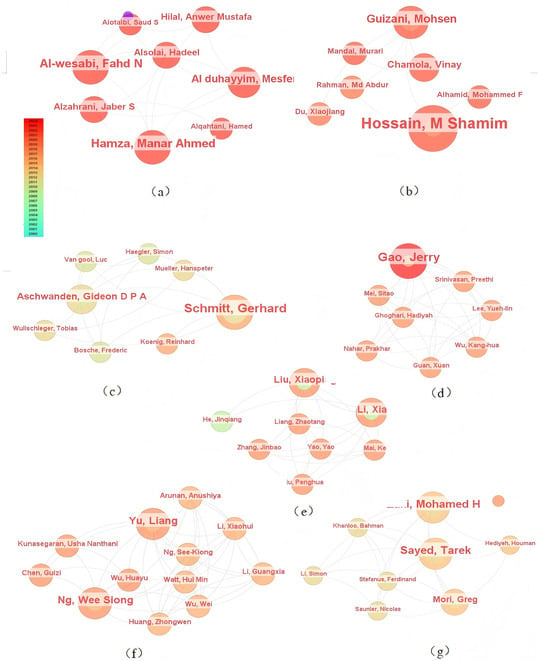

3.2.3. Author Collaboration Network Analysis

At the individual-author level, CiteSpace was used to visualize the author collaboration network. Globally, this field’s largest collaborative research team consists of 8 members, including Hamza, Manar Ahmed; Al Duhayyim, Mesfer; and Al-Wesabi, Fahd N (Figure 10). Other research teams with more than two jointly authored publications include the following: a 7-member team including Hossain, M. Shamim and Guizani, Mohsen; an 11-member team including Yu, Liang and Ng, Wee Siong; a 9-member team including Zaki, Mohamed H. and Sayed, Tarek; an 8-member team including Gao, Jerry; and another 8-member team including Schmitt, Gerhard.

Figure 10.

Author Collaboration Network. (a) The group with the highest output; (b) The second highest output group; (c) The forth highest output group; (d) The fifth highest output group; (e) The seventh highest output group; (f) The third highest output group; (g) The sixth highest output group.

Table 9 summarizes the top 10 most productive authors in terms of publication output. Globally, the most prolific author is Biljecki, Filip, with 11 publications. The remaining top 10 authors, ranked by number of publications in descending order, are as follows: Khan, Muhammad Adnan (9 publications); Park, Jong Hyuk (9 publications); Abbas, Sagheer (8 publications); Lv, Zhihan (8 publications); Hossain, M. Shamim (8 publications); Yang, Yang (7 publications); Yigitcanlar, Tan (7 publications); Zhang, Fan (6 publications); and Guan, Qingfeng (6 publications).

Table 9.

Top Authors by Publication Volume.

Furthermore, a comparative analysis of the author productivity rankings and the author collaboration network reveals that several members of the most prominent research team globally, namely, Hamza, Manar Ahmed; Al Duhayyim, Mesfer; and Al-Wesabi, Fahd N, also rank among the top in publication output, demonstrating a strong correlation between collaboration intensity and research productivity.

3.2.4. Interdisciplinary Research Network Analysis

Due to the richness of the extension of the urban planning discipline, the practice of urban planning involves many sub fields and benefits widely from interdisciplinary teams. Therefore, we have sorted and classified the literature in the literature library according to the categories of the WoS literature, as shown in Table 10.

Table 10.

Distribution of Research Publications by Disciplinary Groups.

Specific analysis shows the following:

(1) Traditional urban planning, as a core discipline, contributes about one eighth of the research and forms the foundation for its application in the field. In existing practice, the transportation direction has achieved fruitful results and accounts for the largest proportion.

(2) Data Science and Artificial Intelligence is the absolute dominant force, accounting for over three-quarters and encompassing the most specific disciplines.

(3) Engineering and Technology accounts for over half of the research, indicating a high dependence on hardware, communication, sensing, and various infrastructure engineering technologies, with a focus on the implementation and execution of solutions.

(4) The high proportion of Environment, Geography and Geosciences highlights the extreme importance that research in this field places on ecological sustainability, climate change, resource management, and spatial geographic information (especially remote sensing).

(5) Social Sciences and Public Administration has the lowest proportion and is much lower than the top ranked ones. This indicates that the integration of humanities and social science perspectives such as socio-economic impact, public policy, and ethical governance in urban planning research is still insufficient, and it is an interdisciplinary direction that needs to be strengthened in the future.

Data analysis clearly shows that research on artificial intelligence in the field of urban planning has successfully bridged the gap with data science and engineering technology, and has formed a deep integration. This field is essentially a typical interdisciplinary research frontier with “data and AI as the core”, “environment and geography as the focus”, and “engineering and technology as the support”.

However, a significant imbalance lies in the absolute dominance of technology (“how to do it”), while the attention of social sciences (“why to do it” and “for whom to do it”) is seriously insufficient. This suggests that future research needs to pay more attention to the intersection with sociology, economics, public policy, and ethics while promoting technological innovation, in order to ensure that technological development is responsible, fair, and people-oriented.

3.3. Keywords and Technological Development Status

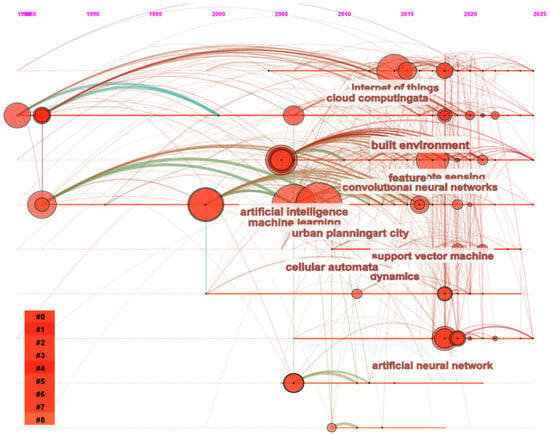

3.3.1. Keyword Evolution Timeline

Utilizing the CiteSpace platform, a visualized keyword timeline was generated based on the literature data (Figure 11). Upon examination, keywords can be broadly categorized into two groups. The first group consists of technology-oriented keywords, such as “machine learning,” “cloud computing,” “big data,” “cellular automata,” and “convolutional neural networks.” These technical keywords account for a substantial proportion of the total. The second group comprises keywords related to research themes and application scenarios, including “internet of things,” “built environment,” and “smart city.” These keywords often serve as the carriers or contextual frameworks for technical terms. Moreover, a longitudinal observation reveals that before the year 2000, few prominent keywords emerged. However, the number of high-frequency keywords increased significantly beginning in 2017, marking the onset of the field’s rapid development phase.

Figure 11.

Visualization of Keyword Timeline.

3.3.2. Timeline of Key Technologies Across Planning Scales

Building upon the analysis of prominent keywords in Section 3.3.1, this study further focuses on technology-related keywords as the core. By integrating the emergence of research themes and application scenario keywords at different time points and using various planning scales as analytical entry points, a summary of frequently occurring technical keywords—i.e., key AI technologies applied in urban planning—is conducted. Additionally, the primary application scenarios of these critical technologies across different urban planning scales are analyzed (Table 11 and Table 12).

Table 11.

Key Technology Development Timeline and Applications.

Table 12.

Chronological Development of Key AI Technologies in Urban Planning by Application Scale.

Based on the table contents, it is evident that the majority of key AI technologies applied in urban planning emerged after 2000, with their frequency of occurrence increasing markedly following the rapid development phase of the field in 2017. The application of AI technologies in urban planning spans macro scales—including data collection and land use, transportation, and infrastructure planning at regional and city levels; meso scales, such as service optimization, resource allocation, and traffic flow optimization at district and community levels; and micro scales, encompassing building boundary extraction, detailed analysis, and traffic flow optimization. Moreover, some AI technologies can cover the entire spectrum of urban planning scales.

A comprehensive observation reveals that AI technologies were predominantly applied at macro and meso scales during the early development stages, only gradually gaining broader adoption in micro-scale urban planning after the rapid growth phase. This further confirms the progressive refinement and increased focus of research directions. The application of AI technologies is expected to continue optimizing performance at both macro and micro scales, while being innovatively extended to a broader array of micro-scale urban planning tasks.

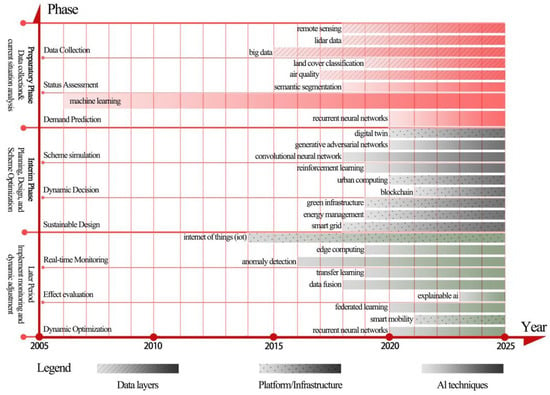

3.3.3. Timeline of Technological Development Across Application Scenarios

To further understand the application of various AI technologies in urban planning, this study focuses primarily on technology-related keywords, while categorizing urban planning work into three broad stages: data collection and status analysis; mid-term planning and scheme optimization; and late-stage implementation monitoring and dynamic adjustment. Each stage is subdivided into three specific tasks, with the types of AI technologies applied and their respective times of emergence differing across these planning steps (see Figure 12). The colored bands in the figure indicate when each AI technology was first utilized within the corresponding planning task and the duration over which the technology has been applied and developed.

Figure 12.

Timeline of Key Technology Development.

Figure 13 indicates that among all key technologies, machine learning was the first to be applied in urban planning, with its initial use documented as early as 2006 in the pre-planning stage for demand forecasting, showcasing the longest development timeline. In general, the application of AI technologies in the pre-planning stage emerged relatively early. In contrast, their implementation in the formal planning stage occurred later, with most advancements after 2017, when the field entered a phase of rapid development. Following this growth phase, research within both the pre- and formal planning stages has increasingly emphasized the refinement and specialization of existing technologies. Conversely, the emergence of entirely new key technologies has become less frequent. In contrast, the post-planning stage demonstrates a broader temporal span of AI technology adoption, beginning with the emergence of the Internet of Things (IoT) in 2014, and extending to the introduction of explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) in 2023, after the onset of a new surge in interest. The emergence of these technologies has been relatively scattered over time. XAI, now a major research focus, was initially applied in performance evaluation processes during the post-planning stage and currently represents the most mature AI application in this context. Notably, once a foundational AI technology is adopted within a specific planning step, it gradually diffuses to other stages of the urban planning process. This reflects a broader trajectory toward the expanded, deepened, and increasingly precise integration of AI across all phases of urban planning.

Figure 13.

Frequency Chart of Key Technology Emergence.

3.3.4. Technological Development Speed

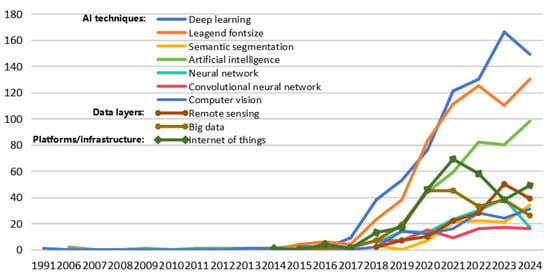

With a comprehensive grasp of how diverse AI technologies are applied across varying spatial scales and phases of urban planning, we further utilized CiteSpace to conduct a statistical analysis of the annual occurrence frequency of key technologies (Figure 14), providing a visual depiction of the rate at which these technologies have evolved within the domain of urban planning.

Figure 14.

Network Topology of Machine Learning-Predicted High-Frequency Future Keywords.

According to the data presented in the figure, deep learning and machine learning emerge as the AI technologies that were not only adopted earlier but have also exhibited the fastest growth trajectories in urban planning. The Internet of Things (IoT) also appeared relatively early and experienced rapid early-stage development; however, its application frequency declined somewhat after peaking in 2021, followed by a rebound beginning in 2023. Additionally, the results reveal a branching relationship between emerging and foundational technologies. For instance, convolutional neural networks (CNNs)—whose usage frequency has steadily increased since 2017—are a subset of the broader neural networks category. This trend further validates AI technologies’ ongoing specialization and refinement within urban planning.

3.3.5. Specific Applications of AI Technologies

From the research above, a general understanding of the application of AI technologies in urban planning has been formed from various perspectives. Based on this foundation, urban planning issues are categorized into key areas including land-use/land-cover mapping, growth/expansion simulation and scenario testing, accessibility and service catchments, housing supply/demand and price dynamics, environmental risks and resilient design, green/blue infrastructure planning and UHI mitigation, low-carbon and energy-aware planning, and equity and inclusion. For each category, we summarize the corresponding data requirements, AI methods, evaluation metrics, typical outputs, and limitations. Representative studies are also provided to serve as a reference for future researchers, offering practical guidance for the application of AI technologies in urban planning (Table 13).

Table 13.

Guidelines for Applying AI Technologies in Future Urban Planning.

Then categorize and interpret key technologies in urban planning, and summarize their application directions and methodologies (Table 14), aiming to provide guidance for the application of AI technologies in urban planning. Based on the above research, a general understanding of the application of AI technologies in urban planning has been formed from various perspectives. In the following section, key technologies in urban planning are categorized and interpreted, and their application directions and methods are summarized (Table 14). The aim is to provide a practical guide for applying AI technologies in urban planning, promote their integration into the planning process, and offer guidance for the long-term development of this field.

Table 14.

Key Technology Interpretation and Application Guidelines.

Based on application scenarios, key technologies in urban planning are categorized into several major sections: fundamental algorithms and technologies, perception and understanding technologies, data and computational support technologies, decision-making and reasoning technologies, ethics and safety technologies, and emerging cross-disciplinary technologies. Each section encompasses several main categories of AI technologies, with each category further divided into specific technical branches. For example, in the section on fundamental algorithms and technologies, the primary AI technologies applied include two major categories: machine learning and deep learning. Within machine learning, further subdivisions include supervised learning (e.g., classification and regression, such as SVM and random forest), unsupervised learning (e.g., clustering and dimensionality reduction, such as K-means and PCA), and reinforcement learning (RL) (for dynamic decision-making, such as DQN and PPO algorithms).

This classification is intended to assist urban planning researchers in quickly selecting appropriate AI tools based on specific application scenarios, thereby enabling the more accurate achievement of planning objectives. In addition, with the support of generative AI-assisted literature review and analysis, and based on a large body of the literature, each AI technology is briefly introduced, and its application scenarios, problem-solving capabilities, and cutting-edge development directions are analyzed. In addition, the data or algorithm platforms required for implementing each technology are listed, providing urban planners with more concrete guidance for applying AI technologies. This approach contributes to the broader adoption of AI in the urban planning field and supports deeper research in the future.

3.4. Prediction of Future Development Trends Based on SVM

Building on the current applications of AI technologies in urban planning, this study employs the support vector machine (SVM)—a machine learning algorithm—to predict future development trends and research hotspots in the field. It intends to guide academic inquiry and advance disciplinary progress.

Based on the previous analysis of the literature data using CiteSpace, the top 10 most frequently occurring keywords in the current research domain were preliminarily identified The confusion matrix shows that when the top 10 keywords are included as predictor variables, the model can effectively forecast and classify the potential for higher citation rates in future publications. The SVM model with a Radial Basis Function (SVM-RBF) kernel is employed. The value range for the parameter is 0.1, 1, 10, 100, and the value range for is set to scale, where scale = 1/(number of features × overall variance of all features), and auto = 1/number of features. Since the scale adapts to the data distribution, it usually performs better. After parameter optimization, the optimal values for the SVM-RBF model are determined as follows, which corresponds to the scale value. Based on 15-fold cross-validation, the confusion matrix for performance analysis of the support vector machine is presented in Table 15.

Table 15.

Confusion Matrix.

Based on the confusion matrix results, the model correctly classified 4092 out of 4097 analyzed data points. This includes 1110 true predictions of “CM” (highly cited) and 2982 true predictions of “N” (non-highly cited), achieving an overall accuracy of 99.88%. The normalized weight values of the top 10 keywords are shown in Table 16, revealing keywords that are relevant to future papers in the field of “AI technology applications in urban planning” and are likely to be frequently used.

Table 16.

Keyword Weight Distribution in Predictive Model.

According to the results in Table 16, the keyword “deep learning” holds the highest weight (w = 0.171), followed by “machine learning” (w = 0.142), “smart city” (w = 0.138), “artificial intelligence” (w = 0.121), and “model” (w = 0.105). The weights of the remaining keywords are all below the average value of 0.1. These findings indicate that all keywords positively correlate with the prediction model (all w values are positive), though the influence of different keywords varies significantly. Based on the calculated weights, it can be inferred that in the field of “AI technology applications in urban planning,” keywords such as “deep learning,” “machine learning,” “smart city,” “artificial intelligence,” and “model” are likely to be more frequently used in future research. In contrast, lower-weight keywords still retain potential application value.

Combining the findings from Section 3.3, the potentially high-frequency keywords in the future are classified into two major categories: technical keywords, and research themes and application scenarios. Among the future high-frequency technical keywords, “artificial intelligence” broadly reflects that AI technology will continue to be a research hotspot in the urban planning domain. Keywords “deep learning” and “machine learning” are expected to sustain current research enthusiasm and undergo deeper investigation and broader application. The keyword “big data” shows a relatively lower future frequency than the former; however, it still maintains significant research interest, possibly because theoretical research in big data has matured, shifting focus more toward methods of utilizing existing data [148]. Notably, some technical keywords with relatively low overall frequency, thus excluded from the machine learning prediction, still possess considerable development potential. Examples include “generative AI” and “explainable AI.” The relatively lower frequency of these AI technologies is likely related to their more recent emergence. Yet, analysis of the large-scale literature reveals that these technologies have become new focal points in recent years [9,149,150], offering novel perspectives for urban planning and thereby underscoring their importance.

Within the future high-frequency research themes and application scenarios category, “smart city” maintains a high level of research interest. A preliminary literature review reveals that the concept of a smart city is broad and encompasses multiple development directions, such as a “smart grid” and “intelligent transportation.” The machine learning prediction also indicates that “Internet of Things (IoT),” as one of the development directions under the broad concept of smart city, will continue to serve as a crucial carrier for AI technologies in the future, being realized and enhanced from multiple research perspectives and directions (Figure 14).

4. Discussion

4.1. Influence of National Policies and Conditions

The research results show that national policies and circumstances significantly impact the application of AI technologies in urban planning.

- 1.

- Guiding and Promoting Role of National Policies in Field DevelopmentFrom the global distribution of the literature output, countries such as China, the United States, and India have become dominant forces in this field due to policy support and technological accumulation (Figure 6). This illustrates that the formulation of national policies plays a crucial guiding role in shaping the development direction and application scenarios of AI technologies in urban planning. It is recommended that government agencies scientifically formulate relevant policies by considering the current status and future needs of both the country and the discipline, so as to promote development that aligns with national requirements.

- 2.

- Impact of National Conditions on the Development of the FieldThe technological development level of a country is primarily determined by its comprehensive national strength and overall national conditions. Most countries with strong comprehensive strength and relatively stable national conditions, such as China, the United States, and the United Kingdom, initiated research in this field earlier. These countries exhibit relatively stable and continuous development while maintaining considerable growth potential. Some countries, such as Japan, Germany, and Italy, started later but have developed rapidly. These countries generally emphasize technological development, possess strong economic power and solid industrial bases, and have favorable conditions for growth.Meanwhile, differences in national conditions have also led to a differentiation in the focus of technological applications:(1) Research on high-density and large-scale cities focuses more on traffic optimization, energy management, and microclimate regulation; low-density cities are more concerned with infrastructure connectivity and the accessibility of public services. High-density urban countries such as Japan focus on disaster response [151] and cultural heritage [152];(2) Global/regional core cities include Beijing, Shanghai, Singapore, London, New York, etc. These cities are both research subjects and major testing grounds for new technologies. Characteristic challenging cities include cities in arid regions (Riyadh), high-density historic cities (Hong Kong, Seoul), and rapidly developing big cities (Delhi, Mumbai). Research often focuses on specific issues in these cities, such as heat islands, transportation, and heritage conservation. Emerging smart cities include Dubai (Saudi Arabia) and Songdo (South Korea). These cities are often studied as demonstration cases of new technologies. Saudi Arabia, a resource-based country, prioritizes the development of energy optimization and cultural heritage restoration technologies [153], reflecting the deep binding of policy objectives, urban location, and technological paths.(3) Economic strength and industrialization level directly affect the speed of technological iteration, and research frontiers in high-income countries often involve sustainability, carbon neutrality, livability, advanced data simulation (digital twins), and citizen participation; research on middle and low-income countries focuses more on improving basic services, expanding infrastructure, land management, disaster response, and applicable technologies (such as demand forecasting based on mobile data). Developed countries (such as Germany and the UK) have rapidly entered a period of explosive growth through policy guidance, while developing countries (such as India) are more concerned with inclusive technologies (such as federated learning) to bridge the social equity gap [154].

4.2. Transformative Impact of AI Technologies on Urban Planning

AI technologies in urban planning have evolved from tool-based assistance to the core driving force promoting innovation and development [155]. This transformative impact is mainly reflected in three aspects:

- 1.

- Restructuring of Planning ProcessesTraditional planning relies on experience and static data analysis [156]. In contrast, AI technologies realize intelligent planning processes through real-time data perception [34,140], multi-source data fusion [21], and dynamic modeling [157], significantly improving planning efficiency and scientific rigor [158,159,160].

- 2.

- Innovation Paradigm Triggered by Generative AIGenerative AI technologies disrupt traditional design methods, such as Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and ChatGPT [150]. Studies have shown that a GAN has been applied to traffic scenario simulation [161] and architectural form generation [162] (Table 8), while large language models can rapidly generate planning proposals through natural language interaction [102]. These technologies shorten design cycles and optimize decision-making through multi-solution comparisons, driving planning from “experience-driven” toward “data-algorithm collaborative-driven.”

- 3.

- Explainable AI Empowering Transparent GovernanceExplainable AI (XAI) techniques reveal model decision logic, addressing the trust crisis caused by AI’s “black box” nature [163,164], while helping the public understand the basis for resource allocation and promoting multi-stakeholder co-governance models [146].At present, the actual management of urban data is usually held by local governments and technology providers or enterprises commissioned by them. Governments often control data collection and access through public platforms, while private enterprises often play a substantive management role in data processing, modeling, and commercial applications.Some cities have started to introduce AI models in policy pilots, but their validation still relies heavily on development teams or internal government evaluations, lacking independent and publicly available third-party validation processes. The rationality, fairness, and reproducibility of model decision-making have not yet formed a unified standard at the industry or policy level. XAI is currently mostly used by planning agencies and communities as a post hoc explanatory tool, rather than embedding public participation into the model development and iteration process.In the future, integrating XAI and blockchain may further enable data traceability and compliance verification, reshaping the ethical framework of urban planning [60,165]. Meanwhile, the fusion of generative AI and XAI is expected to facilitate the emergence of “autonomous planning systems,” achieving full-chain automation from data collection to plan implementation [149].

4.3. Full-Scale Deepening of Tech Iteration and Applications

The application of AI technologies in urban planning exhibits characteristics of the “maturation of foundational technologies, refinement of emerging technologies, and comprehensive coverage of scenarios.”

- 1.

- Deep Penetration of Foundational TechnologiesMachine learning and deep learning have become general-purpose technologies in the planning field, supporting multi-level demands ranging from macro-scale traffic forecasting [19,156] to micro-scale building boundary extraction [166] (Table 11). Research shows that the literature on these two technology types continues to lead in proportion (Figure 14), with algorithmic optimizations further enhancing the accuracy of data fusion and pattern recognition [167].

- 2.

- Emerging Technologies Expanding Micro-Scale ScenariosEmerging technologies such as federated learning and edge computing fill gaps left by traditional methods. For example, edge computing enables real-time parking space recognition [168], while semantic segmentation technology achieves pixel-level analysis of building details [111]. These technologies drive planning from “district-level” optimization to “building-facility-level” precise regulation, which is especially prominent in smart communities and heritage conservation [169].

- 3.

- Full-Scale Collaboration and Cross-Domain IntegrationAI technology applications span the urban planning lifecycle [170,171,172] (Table 8). Additionally, integrating AI with the Internet of Things (IoT) and 6G has spawned interdisciplinary technologies such as cellular automata, enabling dynamic simulation of complex urban systems [120]. In the future, micro-scale technologies (e.g., explainable AI, autonomous vehicles) will deeply couple with macro models (e.g., fog computing, graph neural networks), forming an intelligent planning system characterized by “comprehensive perception–real-time response–closed-loop optimization.” With breakthroughs in quantum computing and neuro-symbolic AI, planning technologies will evolve toward “ultra-precision” and “self-adaptiveness”.

5. Conclusions

This study employed bibliometric analysis, generative AI-assisted reading, and SVM-based prediction models to investigate the current landscape, development trends systematically, and challenges in applying artificial intelligence (AI) technologies within urban planning. A total of 3877 relevant publications were analyzed, addressing five core research questions:

- 1.

- Development Stages:The evolution of AI applications in urban planning can be categorized into three distinct phases: the nascent stage (January 1984–January 2017), the rapid development stage (January 2017–January 2023), and the outbreak stage (January 2023–January 2025). Over time, the field has transitioned from generalized technological exploration to scenario-specific adaptation, and further toward value-driven innovation. This evolution has gradually established a tripartite research framework comprising technology, context, and objectives. AI is expected to remain a central research focus in the field of urban planning for the foreseeable future.

- 2.

- Publication Landscape:China (878 publications), the United States (378), and India (232) are the top three countries in terms of publication volume. National policies and contextual conditions significantly influence AI deployment in urban planning. Wuhan University and the Chinese Academy of Sciences demonstrated high productivity among research institutions. In the global author collaboration network, the Hamza research group made notable contributions, while the most prolific individual author was Filip Biljecki.

- 3.

- Keyword Analysis:High-frequency keywords include deep learning, machine learning, smart cities, and big data. These can be broadly divided into two categories: technological keywords and those related to research themes and application scenarios. Technological advancements are developed mainly in tandem with specific application contexts, reflecting an overall trend toward maturity, focus, and expansion across diverse spatial scales.

- 4.

- Future Directions:Established technologies such as deep learning and machine learning will continue to serve as research focal points. Meanwhile, emerging technologies—particularly generative AI and explainable AI—are expected to offer novel perspectives. The future trajectory is characterized by a shift from macro-level coordination to micro-level precision, supported by full-scale integration and interdisciplinary convergence.

- 5.

- Challenges and Gaps:Current limitations include issues related to data privacy, the digital divide, and ethical concerns. Addressing these challenges will require strengthened international collaboration, promoting inclusive technology, and exploring hybrid applications that integrate various AI paradigms.

This study innovatively integrates generative AI and SVM techniques to enable efficient large-scale literature analysis, systematic synthesis, and predictive insights. It provides a panoramic roadmap for AI deployment in urban planning. Nonetheless, certain limitations must be acknowledged: the data are sourced exclusively from the Web of Science, potentially omitting regional studies; AI-assisted literature data analysis represents an innovative endeavor, offering a potential solution to data limitations in traditional review methodologies within the context of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. However, enhancing the reliability and rigor of this approach remains necessary. While generative AI improves efficiency, its outputs require human verification to mitigate algorithmic biases. Future research should focus on methodological refinements to strengthen this approach; and trend forecasts, based on historical data, may be affected by future technological breakthroughs or policy shifts.

Future studies should consider the following directions to advance this research domain further:

- 1.

- The current research is only based on the WOS core collection, expanding multilingual databases such as CNKI and Scopus to enhance data comprehensiveness;

- 2.

- Validate the applicability, operability, and social acceptance of AI technology in complex scenarios such as urban renewal and disaster response through field cases.

- 3.

- Generative AI and explainable AI have become emerging hotspots, especially in the areas of scheme generation and decision-making transparency. In the future, their application research in collaborative design, public participation, and ethical governance should be strengthened.

- 4.

- The number of works in the literature on emerging technologies is still relatively small, and most of them are in the conceptual or experimental stage. Their actual integration path, technological maturity, and policy adaptability have not been systematically evaluated.

- 5.

- Current research is mostly focused on a single technology or data source, and a complete technology chain and standard framework have not yet been formed. In the future, efforts should be made to strengthen multimodal data fusion and real-time analysis capabilities, supporting dynamic programming and adaptive decision-making.

- 6.

- The existing literature on AI ethics, data privacy, and social impact is still relatively scattered, lacking systematic evaluation tools and policy recommendations, especially in the context of cross-cultural and cross-institutional comparative research. AI applications need to balance efficiency and fairness, and in the future, an interdisciplinary ethical governance framework should be established.

In the future, through interdisciplinary collaboration and technological iteration to continuously optimize technology, and establish policy collaboration mechanisms, AI technology is expected to be more systematically and responsibly integrated into the entire urban planning process, helping to build a more efficient and sustainable smart city ecosystem.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S., Y.Y. and J.W.; methodology, S.S., Y.Y. and J.W.; software, Y.Y.; validation, S.S., Y.Y. and J.W.; formal analysis, S.S. and Y.Y.; investigation, S.S. and Y.Y.; data curation, S.S. and Y.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S. and Y.Y.; writing—review and editing, S.S., Y.Y. and J.W.; visualization, S.S. and Y.Y.; supervision, J.W.; project administration, S.S. and Y.Y.; funding acquisition, J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42471124), the Ministry of Education of China Humanities and Social Sciences General Project (Grant No. 22YJA760086), and the Yangtze River Cultural Park Construction Project of Hubei Provincial Department of Culture and Tourism (Project Title: Functional Zoning Identification and Planning Layout Methods for the Yangtze River National Cultural Park (Hubei Section) Based on Digital Twin).

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in WoS at DOI or reference.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| DQN | Deep Q-Network |

| PPO | Proximal Policy Optimization |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| ResNet | Residual Network |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| BERT | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| CV | Computer Vision |

| 3D Recon | 3D Reconstruction |

| KR | Knowledge Representation |

| FL | Federated Learning |

| GenAI | Generative AI |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| XAI | eXplainable AI |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| LIME | Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations |

| K-means | K-means Clustering |

| MARL | Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning |

References

- Haenlein, M.; Kaplan, A. A Brief History of Artificial Intelligence: On the Past, Present, and Future of Artificial Intelligence. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2019, 61, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.; Lee, S.Y. Large language models in education: A focus on the complementary relationship between human teachers and ChatGPT. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 15873–15892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahlan, A.; Ranjan, R.P.; Hayes, D. Artificial intelligence innovation in healthcare: Literature review, exploratory analysis, and future research. Technol. Soc. 2023, 74, 102321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlacic, B.; Corbo, L.; Silva, S.C.E.; Dabic, M. The evolving role of artificial intelligence in marketing: A review and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 128, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.L.; Yin, D.X.; Qiu, H.L.; Bai, B. A systematic review of AI technology-based service encounters: Implications for hospitality and tourism operations. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebekozien, A.; Aigbavboa, C.; Emuchay, F.E.; Aigbedion, M.; Ogbaini, I.F.; Awo-Osagie, A.I. Urban solid waste challenges and opportunities to promote sustainable developing cities through the fourth industrial revolution technologies. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2024, 42, 729–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Huan, Z.; Kai, J.; Zheng, H.T.; Yue, C.; Peng, C. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Energy-Efficient Edge Caching in Mobile Edge Networks. China Commun. 2024, 21, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.R.; Wu, G.Y.; Barth, M. A Complete State Transition-Based Traffic Signal Control Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 9th Annual IEEE Conference on Technologies for Sustainability (IEEE SusTech), Corona, CA, USA, 21–23 April 2022; pp. 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.F.; Bibri, S.E.; Keel, P. Generative spatial artificial intelligence for sustainable smart cities: A pioneering large flow model for urban digital twin. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 2025, 24, 100526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavirani, F.; Gokhale, G.; Claessens, B.; Develder, C. Demand response for residential building heating: Effective Monte Carlo Tree Search control based on physics-informed neural networks. Energy Build. 2024, 311, 114161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.C.; Yi, X.; Deger, Z.T.; Liu, H.K.; Chen, S.Z.; Wu, G. Rapid post-earthquake damage assessment of building portfolios through deep learning-based component-level image recognition. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 111380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, A.; Pradhan, B.; Gite, S.; Alamri, A. Building Footprint Extraction from High Resolution Aerial Images Using Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) Architecture. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 209517–209527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, M.H.; Afsar-Manesh, N.; Bierman, A.S.; Chang, C.S.E.; Colón-Rodríguez, C.J.; Dullabh, P.; Duran, D.G.; Fair, M.; Hernandez-Boussard, T.; Hightower, M.; et al. Guiding Principles to Address the Impact of Algorithm Bias on Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health and Health Care. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2345050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Brackel-Schmidt, C.; Kucevic, E.; Leible, S.; Simic, D.; Gücük, G.L.; Schmidt, F.N. Equipping Participation Formats with Generative AI: A Case Study Predicting the Future of a Metropolitan City in the Year 2040. In HCI in Business, Government and Organizations; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 14720, pp. 270–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.L.; Johnson, N.N.; McCurdy, D.; Olajide, M.S. Facial recognition systems in policing and racial disparities in arrests. Gov. Inf. Q. 2022, 39, 101753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Aslam, S.; Aurangzeb, K.; Alhussein, M.; Javaid, N. Multiscale modeling in smart cities: A survey on applications, current trends, and challenges. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 78, 103517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsanjani, J.J.; Helbich, M.; Vaz, E.D. Spatiotemporal simulation of urban growth patterns using agent-based modeling: The case of Tehran. Cities 2013, 32, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.Y.; Shi, X.D.; Zhang, H.R.; Song, X.; Zhang, D.X.; Chen, Y.T.; Yan, J.Y. A Phone-Based Distributed Ambient Temperature Measurement System With an Efficient Label-Free Automated Training Strategy. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2024, 23, 11781–11793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.K.; Wang, J.; Zang, H.Y.; Ma, N.; Skitmore, M.; Qu, Z.Y.; Skulmoski, G.; Chen, J.L. The Application of Machine Learning and Deep Learning in Intelligent Transportation: A Scientometric Analysis and Qualitative Review of Research Trends. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.D.; Song, Z.Y.; Lv, C. Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Energy-Efficient Decision-Making for Autonomous Electric Vehicle in Dynamic Traffic Environments. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2024, 10, 875–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.C.; Yan, Y.B.; Hao, X.X.; Hu, Y.H.; Wen, H.M.; Liu, E.R.; Zhang, J.B.; Li, Y.; Li, T.R.; Zheng, Y.; et al. Deep learning for cross-domain data fusion in urban computing: Taxonomy, advances, and outlook. Inf. Fusion 2025, 113, 102606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, E.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Duffy, K.; Ganguly, S.; Madanguit, G.; Kalia, S.; Shreekant, G.; Nemani, R.; Michaelis, A.; Li, S.; et al. Semantic Segmentation of High Resolution Satellite Imagery using Generative Adversarial Networks with Progressive Growing. Remote Sens. Lett. 2021, 12, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.J.; Zhu, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.W.; Yu, F.R.; Tang, T. Digital Twin-Driven VCTS Control: An Iterative Approach Using Model-Based Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 3913–3924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, C.A.; Chacón, M.; Donatti, C.I.; Garen, E.; Hannah, L.; Andrade, A.; Bede, L.; Brown, D.; Calle, A.; Chará, J.; et al. Climate-Smart Landscapes: Opportunities and Challenges for Integrating Adaptation and Mitigation in Tropical Agriculture. Conserv. Lett. 2014, 7, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanusa, J.; Baraja, M.C.; Anghel, A.; von Niederhäusern, L.; Altman, E.; Pozidis, H.; Atasu, K. Graph Feature Preprocessor: Real-time Subgraph-based Feature Extraction for Financial Crime Detection. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on AI in Finance, Brooklyn, NY, USA, 14–17 November 2024; pp. 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]