Abstract

The tangible and intangible heritage of a region can form the basis for innovative tourism models capable of fostering sustainable development in a specific local area. In this context, thematic trails are increasingly recognized as a tool for connecting tourism to local heritage, although they tend to focus on food and wine itineraries, avoiding the development of structured models that can be replicated in other production chains. This study aims to fill this gap by proposing a scalable framework for designing thematic tourism itineraries that integrate and enhance local heritage. Inspired by the “Destinazione Impresa” model, the proposed framework emphasizes community engagement and multilevel collaboration among stakeholders as key factors for sustainable and localized tourism. The framework was tested in two rural areas of Piedmont (Italy) selected for their distinctive productive traditions and limited exposure to mass tourism: Moncucco Torinese, linked to the gypsum supply chain, and the Biellese area, linked to dairy production. The participatory methodology employed, based on the Delphi method, confirmed the willingness of local stakeholders to co-design thematic trails. Findings highlight the potential of thematic trails to enhance economic diversification, foster community participation and preserve local identity, while offering a practical and transferable methodology for sustainable tourism development in underexplored areas.

1. Introduction

In recent years, tourists have sought authentic experiential tourism that allows them to connect with local culture, history and traditions [,]. On the one hand, food and wine tourism and its various forms have established themselves as effective tools not only to enrich the visitor experience, but also to promote territorial development and economic diversification, particularly in rural and marginal areas [,,]. In this sense, participation in visits to farms and local markets and the interaction with producers stimulate a deeper understanding of a local heritage and promoting immersive and educational tourism []. Food and wine tourism generates direct benefits for local economies by supporting small producers and local operators. Furthermore, it contributes to the preservation of cultural traditions, often vulnerable to the pressures of mass tourism [,]. At the same time, the growing number of museums dedicated to food reflects a widespread commitment to protecting local knowledge and promoting the cultural value of gastronomy, which is accompanied by tourists’ growing desire for knowledge and storytelling [,].

On the other hand, tourism based on production chains, other than food ones, shares the scope of local development with gastronomic tourism [,]. It is characterized by distinctive elements, such as the promotion of resources and traditions linked to the industrial, handcrafting and manufacturing production of a local area, helping to preserve and promote these chains []. This kind of tourism allows visitors to discover and appreciate production processes (e.g., glass, ceramics, metals, wood) creating a link between cultural and industrial heritage. Through visits to factories, handcrafting workshops, industrial museums or interactive exhibitions, tourists can deepen their knowledge of traditional and modern techniques used in the production process [,]. Furthermore, local businesses involved in these activities can benefit from greater visibility and an improved image, thanks to direct contact with consumers []. At the international level, thematic tourism trails have found widespread application in various forms and several examples can be provided, such as wine routes in France and Spain, cultural and religious itineraries in Southwestern Europe (e.g., the Camino de Santiago) and industrial heritage itineraries in Germany and the United Kingdom. Similarly, ecomuseums in Central and Northern Europe and food and wine itineraries in North America and Australia demonstrate how integrating local resources into narrative itineraries can promote regional development and cultural identity.

By placing the Italian cases within this broader context, this study highlights both their comparability with established international practices and their potential to enrich the global debate on place-based tourism models. In particular, the aim of this study is to propose a framework for the creation of thematic tourist trials that enhance specific local resources, such as extractive resources or traditional food products, as a key element for the development of integrated and sustainable tourism experiences. The framework is based on a pre-existing framework developed within the Interreg Italy-Switzerland 2007–2013 program, originally conceived to structure company visits, named “Destinazione Impresa” []. This research expands its scope, including the entire supply chain, from raw materials to finished products, in a participatory and community-oriented approach.

To test the framework, two Piedmontese case studies were selected: the gypsum area of Moncucco Torinese (Asti province) and the dairy area around the city of Biella (including the municipalities of Pollone, Mongrando, Sordevolo, and Occhieppo Superiore). These areas have been chosen for their tourism potential, their connection with distinctive local production networks, and their geographical limitations.

The paper is structured as follows: Section Literature Review presents a literature review, identifying gaps in existing thematic tourism trail models. Section 2 describes the areas of the study and the research methodology, including the application of the Delphi method. Section 3 discusses the main findings, focusing on the definition and the interpretation of the proposed framework. Section 4 compares the literature review with the evidence emerging from the study, highlighting the main characteristics of the framework. Finally, Section 5 presents the final remarks, addresses the limitations of the study, and identifies potential directions for future research.

Literature Review

Growing interest in experiential tourism has led to the diversification of tourism offerings, particularly in rural areas, where local food production and natural resources are closely linked. Several studies have highlighted the potential of food and wine tourism to support sustainable local development, combining diverse aspects such as economic, social and environmental dimensions [,,,,,,]. A part of literature focuses on tourism linked to agri-food supply chains, such as those of milk-cheese, and other local products, which typically develop in rural and mountainous contexts [,,]. These kinds of tourism generate a win-win system: on the one hand, they create added value for producers and local operators and, on the other, they enrich the visitor experience through contact with authentic local practices.

The most commonly used conceptual framework for structuring such initiatives is the thematic trail. This term generally refers to a journey curated around a shared theme, often gastronomic, with the aim of promoting both the product and the region of origin [,]. Thematic trails foster a deeper connection between the visitor and the host community, highlighting several aspects of local supply chains such as the cultural, environmental, and economic dimensions [,].

One study has shown that the quality of the experience is crucial for tourist satisfaction and loyalty []. From a marketing and destination management perspective, the ability to create differentiated and rooted tourism products is essential for competitiveness, especially in less frequented areas [,]. In this sense, thematic trails represent an opportunity to integrate diverse territorial resources, such as natural or cultural ones, into a coherent tourism offer [,]. Their success often depends on the level of coordination between local stakeholders and the ability to share knowledge systems [,,,,].

In recent years, the concept of the eco-cultural itinerary as a model that combines ecological and cultural dimensions has gained ground. This approach aligns with the principles of sustainable tourism and ecotourism, promoting low-impact activities, such as walking, hiking, or cycling, that enhance the landscape and heritage [,]. Furthermore, eco-cultural itineraries emphasize storytelling, local knowledge and community involvement in building the tourist experience [,].

Beyond Italy, several theoretical frameworks and applied experiences provide relevant insights for the design of thematic itineraries. The literature on cultural itineraries highlights their role in heritage conservation and regional development [,,,], and eco-cultural itineraries reinforce this evidence by emphasizing the synergies between environmental sustainability and community engagement [,]. The best-known international examples concern international cultural heritage sites (e.g., the Camino de Santiago), which combine religious and economic aspects, or national environments characterized by a very strong connection to the productive past (e.g., the German Industrial Heritage Trail), demonstrating the potential of reusing industrial landscapes for tourism purposes. In the gastronomic context, wine itineraries in France, Spain, and Portugal, as well as culinary itineraries in North America and Australia, have been theorized as service ecosystems that generate both economic and cultural value []. These different frameworks suggest that thematic itineraries can function as multifunctional tools for territorial development [], but they also reveal the need for adaptable models capable of integrating local supply chains and stakeholder governance with sustainable development criteria.

In this context, a thematic trail can be a vehicle for economic growth and a tool for cultural transmission and environmental awareness. Visitors are guided along the entire supply chain of a product, whether food or mineral, to discover the unique characteristics of the place and the people who work there [,,]. Furthermore, thematic trials can be adapted to different kinds of tourism, such as religious or industrial tourism, making them particularly effective in promoting slow and multidimensional tourism experiences [,].

Some contributions also highlight the role of museums, particularly those located in rural contexts, as key tools for the conservation and dissemination of tangible and intangible heritage [,,]. Eco-museums, for instance, support the preservation of local identity and the promotion of different types of tourism [,].

The literature suggests that models able to integrate local stakeholders, enhance production networks, and align with sustainability criteria are the most promising for developing thematic trails [,,] and generating positive impacts for the geographical area involved [,,,]. However, structured methodologies capable of guiding the design and implementation of such models are lacking, particularly in areas with limited tourism infrastructure or poor visibility.

This research aims to fill this gap by proposing a replicable framework that connects tangible and intangible local heritage through a participatory approach.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Areas

This study focuses on two rural areas in Piedmont (Northwestern Italy): the Biellese area and Moncucco Torinese (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study areas.

Both areas possess distinct local identities and production traditions, dairy products in the Biellese area and gypsum in the Moncucco Torinese area, which form the basis for local development strategies through themed tourism. These areas were selected based on three main criteria:

- Presence of a specific local production chain (milk-cheese and gypsum, respectively);

- Absence of infrastructure related to mass tourism, indicating untapped potential;

- Geographical compactness, which facilitates the creation of coherent and accessible itineraries.

The Biellese area includes the municipalities of Pollone, Mongrando, Sordevolo and Occhieppo Superiore, historically linked to cattle breeding and milk processing, with the presence of three important dairies and significant museum initiatives. The Moncucco Torinese area, located in the Asti hills near Castelnuovo Don Bosco, is characterized by a historic gypsum mining industry, the production of decorative stucco, and a growing tourist interest linked to nature and religious itineraries.

2.1.1. Biellese Area

The area of the province of Biella, which is the subject of the analysis, includes the Elvo Valley area, with particular reference to the municipalities of Biella, Occhieppo Superiore, Mongrando, Sordevolo and Pollone. It is characterised by a tradition of cattle breeding, in particular of the local “Pezzata Rossa d’Oropa” breed and by the availability of pastures and mountain dairies in the mountainous areas. The dairy tradition is also evidenced by historic dairies and museums, often family-run. The Pier Luigi Rosso Dairy, active since 1894 in Sordevolo, keeps alive the family tradition of producing and maturing typical cheeses, now carried on by the fourth generation; the Caseificio Valle Elvo, a cooperative founded in 1999, has 55 members and produces a wide range of cheeses and dairy products; the Botalla Formaggi, founded in 1947 and run by the Bonino family since 1978, combines tradition and innovation, recently expanding its production with the opening of a new processing plant in Mongrando. In 2019, Botalla (in collaboration with Birra Menabrea) inaugurated MEBO, a museum dedicated to the history of local cheese (and the historical Italian beer Menabrea), and in 2024, Caseificio Rosso opened its own museum, “FORMA”, in Pollone, thanks to European funding for the development of sustainable tourism.

Alongside these medium-sized businesses, the area is characterised by the presence of small dairy producers (farmers) and small milk processors (farmers-producers), who help to keep the traditional supply chain alive and preserve the direct link between the land, farming and processing. Milk producers are often also suppliers to dairies and tend to operate in the plains during the winter, while in summer they move to the mountains, using pastures and mountain dairies when weather conditions allow.

As one might imagine, these realities represent, on one hand, a support system for an important food chain (dairy) and, on the other, a guardian of the memory and culture of the local area for the preservation of local intangible heritage.

2.1.2. Moncucco Torinese Area

Moncucco Torinese, a small village in the province of Asti, is located on the border with the province of Turin, in the heart of the Basso Monferrato hills. The surrounding area, known for its wine and truffles, combines nature and culture and is an ideal destination for excursions. The local trails retrace ancient connections between the villages, while the nearby village of Castelnuovo Don Bosco is home to Colle Don Bosco, a major centre of religious tourism and part of a large Salesian devotional complex. To enhance both the landscape and the historical and religious heritage, the “Cammini di Don Bosco” (Don Bosco Trails) have been created, over 175 km of itineraries connecting Turin and the rural landscapes of Asti province. The municipalities of Castenuovo Don Bosco, Moncucco Torinese and the surrounding areas is also known as the “Land of Saints”, as it is the birthplace and/or place of education of many saints and blessed figures, and boasts a rich Romanesque heritage, with the Abbey of Vezzolano as the most famous example.

Despite the high number of religious visitors, tourism in this area struggles to integrate its spiritual offering with other types of tourism, as most of the services are bound and managed by the Salesian religious order. In any case, religious aspects are not the only ones that can be promoted locally. The historic centre of Moncucco Torinese, for example, is characterised by its medieval castle, built in the 12th century as a strategic and commercial stronghold on a network of fortified settlements (it has hosted civil and social functions in the past and still houses the primary school and nursery school today), and the presence of the Società Operaia di Mutuo Soccorso, a historic institution of assistance and solidarity, where the first Bottega del Vino del Piemonte (Piedmont Wine Shop) was founded in 1981.

The territory of Moncucco Torinese is also linked to the tradition of gypsum, used for centuries in construction and decoration. The first documented extractions date back to the 17th century, with a quarry that employed over twenty workers in the 20th century. The activity, which passed through various owners over time, ceased at the beginning of the millennium, leaving a landscape that has now been recolonised by vegetation. A few kilometres away, in Bardella di Castelnuovo Don Bosco, is the only preserved gypsum kiln in Monferrato, a clear example of Piedmontese industrial archaeology. In order to promote and enhance the memory of this production chain, the Gypsum Museum was established, born from thematic exhibitions and housed in spaces that recount the geology, extraction techniques, tools and artistic applications of the material. Currently, the museum is located in the medieval castle and is managed by volunteers from the association “In Collina”.

2.2. Methodology

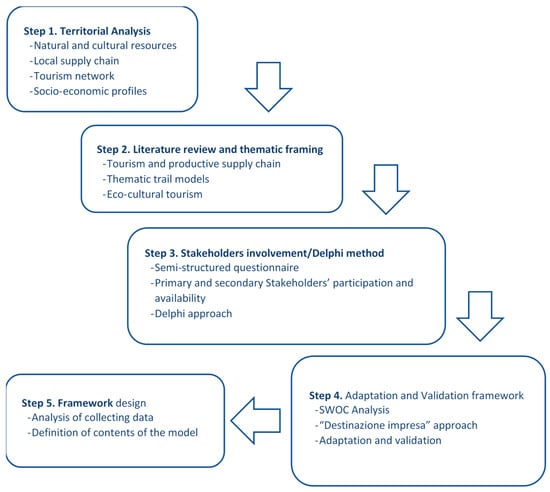

The development of the thematic trail framework followed a multi-phase approach, integrating several different techniques. The main phases of the methodology can be listed as follows: Step 1 (Territorial Analysis); Step 2 (Literature Review and Thematic Framing); Step 3 (Stakeholder Involvement/Delphi Method); Step 4 (Adaptation and Validation Framework); Step 5 (Framework Design).

In the first step, an in-depth analysis of the two areas was conducted to map the following: natural and cultural resources; the structure and dynamics of local production chains; existing tourism infrastructure; socioeconomic and demographic profiles. This phase aims to identify the value-generating elements of each area and assess their potential as pillars for the development of thematic trails.

In the second step, a literature review was conducted to define a theoretical and operational framework on the following topics: tourism linked to production chains; thematic trail models; eco-cultural tourism; participatory planning methods. This review guides the development of survey tools and methodological choices for stakeholder engagement.

In the third step, a qualitative approach based on the Delphi method was adopted, aimed at gathering input from key local stakeholders [,,,,,]. This technique, widely used in forecasting and scenario building, allowed for a structured collection and progressive synthesis of stakeholder opinions on various topics, such as tourism potential, the level of preparedness of local stakeholders, perceived barriers and opportunities, and desirable elements for a thematic trail. Participants included different kind of local operators, e.g., producers, tourism and cultural operators. To this end, a semi-structured questionnaire was developed to be administered to a selection of local stakeholders. The questionnaire consists of open-ended questions and was developed to gather qualitative information on local stakeholders’ perceptions and expectations regarding the development of thematic tourism trails. The questionnaire was designed in a unified version, valid for both study areas, Moncucco Torinese (resource: gypsum) and the province of Biella (resource: dairy supply chain), to ensure homogeneity in data collection and allow for a consistent comparison between the two geographical contexts. The questions were designed to explore the relationship with the local area and its distinctive resource, the perception of the connection between the resource and local cultural identity, the visitor experience and proposals for improvement symbolic places linked to the resource, the identification of places or entities for the territorial narrative, opinions regarding the creation of thematic tourist trails, profile of potential visitors most interested in such itineraries, the willingness to use digital tools to enrich the experience, and the willingness to actively participate in the tourist trail design. The open-ended nature of the questions encouraged open responses, rich in insights and personal reflections, which contributed to a better understanding of the area’s tourism potential, stakeholder availability, and perceived critical issues. A track of the questionnaire is provided in Appendix A. The final version of the questionnaire was developed after conducting a preliminary validation focus group. The group consisted of academic experts with proven experience in the sustainable tourism sector and industry, as well as sector experts committed to enhancing local heritage. Participants provided helpful suggestions for feasible rewording of the questions, with the aim of improving the ability to obtain detailed answers consistent with the research objectives, avoiding terminological ambiguity, and ensuring lexical consistency with respect to local contexts. Another essential aspect of the third step is the involvement of a wide range of local stakeholders. Indeed, in addition to diverse actors and institutional stakeholders, the involvement of local communities is essential for the success of the initiative []. Community participation is therefore recognized as both a fundamental resource and a challenge, given the existing limitations in terms of skills, financial resources, and organizational capacity in creating an effective local network. In the research, in fact, numerous local stakeholders operating in the two areas were identified and involved. The stakeholders were selected based on their direct or indirect connection with the local resource, as well as their potential influence in the development of thematic tourist trails. With reference to the classic definition of stakeholders [,,], a distinction was made between primary stakeholders, i.e., subjects directly interested or involved in the project as an active part of the supply chain (e.g., producers, tourist guides), and secondary stakeholders, who, although not directly involved in the use or management of the resource, play a supporting or regulatory role (e.g., public bodies, restaurateurs). In the Moncucco Torinese area, for example, the primary stakeholders were identified in the Gypsum Museum, the Workers’ Mutual Aid Society and the local tourist guides; secondary stakeholders include the Municipality, the Pro Loco tourist board and restaurateurs. In the case of Biella, for example, primary stakeholders include local dairies, supply chain museums, breeders, and tour guides. Secondary stakeholders include different kinds of organization such as the Local Action Group, Local Foundation, restaurant, Local Associations. The complete list of participants is provided in Table 1. This classification was used to more effectively structure the investigation phase, differentiating approaches and analysis tools depending on the type of stakeholders involved.

Table 1.

List of stakeholders involved.

In the fourth step, the pre-existing “Destinazione Impresa” model, originally developed for industrial tourism and company visits, was used as the conceptual basis. The model was reinterpreted to include the entire production chain, from raw materials to finished products, and to integrate local tangible and intangible heritage, extending it to types of tourism beyond company visits. A SWOC (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Challenges) analysis was applied to the data collected through interviews and fieldwork, with the aim of validating the feasibility and adaptability of the framework to the two geographical contexts []. This type of analysis provides a structured approach to assessing internal factors (strengths and weaknesses), along with external conditions (opportunities) and a combination of internal and external conditions (challenges), thus supporting a comprehensive assessment of the proposed model’s potential and limitations. In this context, challenges are conceived as practical obstacles or constraints that must be addressed to ensure the proposed model’s effective implementation and long-term sustainability.

In the fifth step, the outcome can be defined as a thematic trail framework, based on participatory governance and the integration of the tangible and intangible local heritage in a scalable and adaptable manner in different territorial contexts (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Diagram of the research methodology.

3. Results

This section presents the main findings of the study, resulting from field analysis, stakeholder interviews and the application of the Delphi method. The findings are organized around two main areas of analysis: (1) an in-depth evaluation of the two pilot areas, Biella and Moncucco Torinese, and (2) a comprehensive SWOC analysis assessing the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and challenges associated with the implementation of the proposed thematic trail framework.

3.1. Local Resources and Stakeholder Feedback

3.1.1. Biella Area

The Biella area shows strong potential for the development of themed tourism based on its traditional dairy heritage. The presence of family-run or cooperative dairies offers concrete anchors for the construction of a supply chain-based trail.

Interviews revealed a general willingness among producers and institutional stakeholders to participate in tourism development. In particular, all the interviewees evidence a positive attitude towards the creation of tourism for the dairy supply chain, and they agree with the sentence “Possibility and the willingness to develop new typology of tourism that would attract a wide public to the territory”. The local tourist guides (no. 3) think that there is a positive attitude towards the creation of tourism for the dairy supply chain. At the same time, they claimed a slow beginning of development of industrial tourism on the territory. Mostly, the proposals developed on the territories nowadays are linked with one-day trails visiting on the way some farmhouses. In this sense, the level of preparation is uneven. The small producers evidence a lack of the infrastructures, personnel and training necessary to engage in regular tourism activities (no. 4 interviewees). They identified that the main challenges is access to mountain pastures and milk suppliers, which represent the initial stage of the dairy supply chain. These are often geographically dispersed and poorly connected, and farmers are understandably focused on production, with little time or incentive to participate in tourism activities (no. 3 interviewees).

Furthermore, the culture of hospitality is not so developed, with little willingness on the part of the actors themselves, who are often overburdened by production activities and are unable to devote themselves to other-side activities, especially if they are not so profitable from an economic point of view. This consideration is shared by 5 interviewees.

A promising direction is the inclusion of small integrated farms, where animal husbandry, milk processing and direct sales take place on-site. These initiatives offer manageable and immersive experiences, suitable for small groups and educational tourism (no. 3 interviewees). Furthermore, the presence of dedicated museums confirms the local interest in preserving and narrating the local dairy culture (no. 5 interviewees). These institutions could serve as interpretive centers for visitors, helping to contextualize dairy production within historical and territorial narratives (no. 7 interviewees).

In any case, local tangible and intangible heritage offers a range of opportunities to enrich the dairy journey (all the interviewees): there are natural hiking trails, mountain huts and religious paths (for example, linked to the Sanctuary of Oropa) which can contribute to the creation of a multifaceted offering that balances tangible and intangible aspects of the local heritage, such as gastronomic and spiritual dimensions.

Finally, it emerged that some local stakeholders have already independently developed thematic trails through micro-networks of operators, consisting of breeders, producers, and/or cultural institutions (no. 4 interviewees). These forms of network organization, often informal or associative, have proven effective in promoting specific local segments and facilitating operational synergies between entities sharing similar thematic interests or resources. However, the limited size and fragmentation of these micro-networks result in a limited capacity to systematically enhance the local area. In particular, the lack of a unified local-scale plan can compromise the construction of a cohesive and recognizable local identity, weakening the overall competitiveness of the area as a thematic tourism destination. Therefore, while these initiatives represent a positive sign of bottom-up activation, they also highlight the need for a coordination capable of integrating existing experiences into a shared strategic vision.

3.1.2. Moncucco Torinese

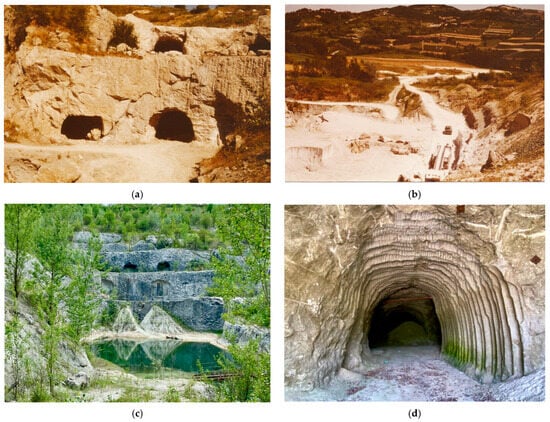

The Moncucco Torinese area presents a less explored context than the Biella area, yet the area is equally rich, based on gypsum mining, stucco production and a landscape affected by human activity. The Gypsum Museum and the historic gypsum kiln are unique resources, representative of Piedmont’s lesser-known industrial heritage. These sites could therefore serve as narrative hubs in a thematic trail linking geology, architecture and collective memory (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The gypsum quarry in Moncucco Torinese: (a) The gypsum quarry in Moncucco Torinese in 1983. Credits: I. Aires. (b) Entry routes to the site (1983) Credits: I. Aires and present (c) The gypsum quarry in Moncucco Torinese in 2025. Credits: R. Beltramo. (d) The gypsum quarry in Moncucco Torinese. Details (2025). Credits: R. Beltramo.

Interviews with the former quarrymen (no. 9) reveal a profound sense of identity and pride linked to the gypsum industry. Their testimonies highlight the solidarity and hardships shared by workers, the specificity of manual roles in the production cycle and the social significance of this activity within the community. Residents have also shown a willingness to open their homes to visitors, particularly to showcase their traditional plaster ceilings, a architectural feature that characterizes this area. This openness could be leveraged for participatory tourism initiatives, such as open-door events, workshops or narrated walks.

Primary and secondary local stakeholders involved in the study evidence the potential role of the gypsum supply chain as a tool to improve the tourism value of this local area: in fact, the majority of the interviewees (no. 9) believe that the creation of a gypsum thematic trail is possible with the collaboration of all the local stakeholders (no. 10) and the financial support of public bodies and/or foundations (no. 7). In any case, all the interviewees agree with the following sentence “The creation of thematic trails would represent an opportunity for economic growth and increased tourism for the town, as well as an investment and a new use for the now abandoned and closed quarry”.

Finally, the study highlighted opportunities for connecting the area and the landscape. The recovery and reinterpretation of trails, quarry and abandoned production sites would enable the development of new eco-industrial trail, positioning Moncucco Torinese as a hub for slow tourism. Furthermore, the study of the Moncucco Torinese area has led to discussions about plans to open private homes to the public, with the aim of enhancing the traditional decorated plaster ceilings, an expression of local architecture and handcrafted know-how.

All these elements, if appropriately documented and displayed, could strengthen the narrative power of the site and enhance its emotional value. The local context of Moncucco Torinese therefore presents favourable conditions for the development of a thematic trail, thanks to the shared and cross-cutting interest among local stakeholders, both primary and secondary. The diversity of the stakeholders involved, combined with a shared desire to enhance the tangible and intangible local heritage, provides a solid foundation for developing a cohesive local narrative.

The convergence of visions among the stakeholders, which emerged during the study, suggests an opportunity for participatory and inclusive governance capable of supporting bottom-up heritage enhancement processes. This approach fosters the emergence of an active collective memory and enables the development of a tourism offering that truly reflects the cultural and social specificities of the local area. In this sense, the Moncucco Torinese area, although less explored than other regional contexts, emerges as an ideal testing ground for implementing slow and community-based tourism practices, found on the integrated promotion of local resources and the direct involvement of local community. The only limitation identified is the lack of initial capital to launch coordination and planning activities, a necessary condition for translating existing potential into structured actions.

3.2. SWOC Analysis

A SWOC (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Challenges) analysis was conducted to generalize the study findings to the pilot areas and thus assess the feasibility and transferability of the framework (Table 2).

Table 2.

SWOC analysis synthesis.

The identified strengths can be described as follows. In both areas, stakeholders demonstrate a clear sense of belonging, with tangible and intangible resources, e.g., cheesemaking traditions, gypsum architecture, which can differentiate the tourism offering and foster authentic visitor engagement (local identity). The presence of established supply chains (dairy in the Biella area, gypsum in Moncucco Torinese area) ensures that the framework is grounded in a concrete economic and social infrastructure, increasing its credibility and feasibility (production networks). The existence of thematic museums provides a ready foundation for building engaging narratives, serving as a gateway to more widespread and territorial itineraries (thematic museums). Interviews with stakeholders reveal a positive attitude toward tourism as a form of cultural enhancement and economic diversification, especially in areas currently experiencing demographic and economic decline (community interest).

The identified weaknesses can be described as follows. Many sites, particularly mountain pastures or quarry areas, are difficult to reach due to poor infrastructure, limiting the inclusion of tourists with disabilities or short-term stays (limited accessibility). Several producers and stakeholders lack the training, staff, and/or facilities necessary to host visitors. This limitation affects both the quality and scalability of the tourism offering (poor hospitality). Existing tourism activities are often isolated and poorly integrated in terms of narrative or coherent itineraries, highlighting the need for coordination among local operators, which is essential to avoid duplication or inefficiencies (fragmentation). Furthermore, there is a certain tendency toward individualism on the part of some operators, who favour the creation of self-referential micro-networks, hindering the creation of broader, more inclusive, and strategically oriented coordination structures (lack of integration). Lastly, many stakeholders are already burdened by their core production activities and may not be able to engage in secondary activities such as guided tours or workshops unless adequate incentives are provided (workload).

The identified opportunities can be summarized as follows. Contemporary tourists increasingly seek experiential and educational travel. The proposed framework aligns well with these trends, offering direct access to local culture and nature (targeted tourism). The areas under consideration are close to areas with higher tourist flow. This represents an opportunity to define integrated strategies for organising day trips or itinerary extensions (proximity). The study highlights that the areas can intersect with different types of tourism, such as religious (the sites of Don Bosco or the Sanctuaries of Biella), industrial (the gypsum museum or company visits), or ecological (tours in green areas), creating layered narratives and seasonal flexibility (multi-thematic integration).

The challenges highlighted by the analysis suggest the following: successful implementation depends on clear and consistent communication strategies capable of conveying the value of the route to both residents and potential visitors (coordinated communication). Small rural municipalities often lack the financial resources and sometimes lack the strategic vision to implement complex tourism projects, which require external partnerships or regional coordination (public investment). Communities must equip themselves with the necessary tools to preserve local heritage and authenticity from tourist deviations that could diminish the value of the experience (cultural impoverishment).

3.3. Definition of the “Thematic Supply Chain Trail” Framework

Findings suggest that thematic trails based on production chains can generate added value by improving the visibility and accessibility of local production and culture. Furthermore, it can promote cross-sector collaboration and community pride and low-impact tourism. However, fully understanding the entire supply chain is often difficult to achieve considering aspects such as logistic issues. The study therefore suggests implementing a modular and adaptive framework, in which each identified area can define the scope, scale and priority of the intervention with an active involvement of local stakeholders as co-designers of the experience. The framework should therefore serve as a participatory planning tool that promotes inclusive development tied to the geographic area analysed.

In light of the results obtained from this study, the following considerations can be made. The proposed framework that can be constructed from the emerging evidence should aim to enhance tourism in underexplored areas through the integration of the local heritage (tangible and intangible), local stakeholders (enterprises, institutions, communities), local supply chains (e.g., agri-food or mining) and demand for experiential and sustainable tourism.

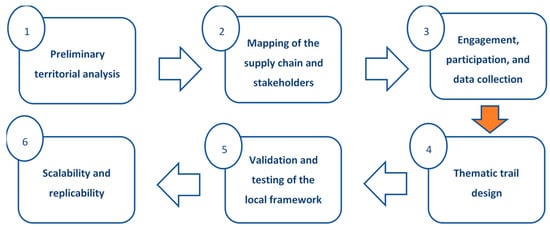

The framework can be structured into four operational phases that can be adapted to different territorial contexts:

- -

- Preliminary territorial analysis. Identification of a geographical area with a coherent and representative production chain, distinctive cultural and natural characteristics, available tourism potential.

- -

- Mapping of the supply chain and stakeholders. Identification of the actors involved in the supply chain, such as primary producers, processors, cultural institutions, museums, local authorities, tour guides and associations.

- -

- Engagement, participation and data collection. Activation of participatory processes (Delphi, interviews, focus groups) to assess stakeholder availability, gather ideas and needs, identify resources and critical issues.

- -

- Thematic trail design. Construction of a coherent narrative path that connects the various actors and locations, enhances all stages of the supply chain, and integrates landscape and local heritage.

To ensure the practical applicability and long-term effectiveness of the proposed framework, two additional phases are suggested. Although not directly investigated, they are based on established planning principles and observed stakeholder dynamics.

A validation and testing phase addresses the need for progressive refinement through the implementation of a pilot version of the thematic trail, effectively introducing the concept of continuous improvement. This activity allows the collection of direct feedback from visitors and local stakeholders, suggesting adjustments to enhance the experience and stakeholder engagement.

A second phase focuses on scalability and replicability. While not empirically verified, it represents a logical extension of the model. Adapting it to other production sectors and local contexts can lead to the creation of a network of interconnected thematic trails in a specific area. The integration of these two phases into the framework can help consolidate the role of the model as a strategic tool for local development. Therefore, the following phases are suggested to be added to the framework:

- -

- Validation and testing of the local framework. Creation of a pilot version of the trail, monitoring visitor and stakeholder reactions, and revising the itinerary based on the feedback gathered.

- -

- Scalability and replicability. Adaptation of the framework to other areas and/or sectors (e.g., textiles, wine, crafts), creation of a network of thematic trails on a local scale.

The final version of the framework can therefore be summarized as in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

“Thematic Supply Chain Trail” Framework.

The Interpretation of “Thematic Supply Chain Trail” Framework

The proposed framework is based on cross-cutting elements that can be identified as follows. Community participation and co-design are key elements that enable the active involvement of local communities in all phases of the tourism development process. Communities are considered true co-creators of the tourism product, contributing their resources and vision. This approach ensures deeper cultural rooting and fosters greater acceptance and sustainability of the project over time, also fostering a sense of belonging and collective responsibility. Furthermore, the concept of community is also an element that create the opportunity to build networks and multilevel governance by fostering interaction between public and private local stakeholders. This network allows for more effective sharing of expertise, easier access to funding and projects and the possibility of replicating the model in other areas at the regional level. Community participation is combined with local narrative as a distinctive element that enables the construction of storytelling capable of giving meaning and coherence to the thematic trail. Each itinerary should tell a story that involves people, products, places and collective memory, defining in a better manner the identity of the area. Tools for constructing this narrative include oral histories, family archives, local museums and appropriate interpretive signage. The goal is to offer an emotionally engaging and identity-building experience.

The framework also is oriented to a multi-thematicity approach connecting different experiential dimensions, e.g., from gastronomic to religious tourism, from industrial archaeology to ecotourism, etc. This integration makes it possible to attract a broader and more diverse audience and extend the average visitor stay, stimulating an improvement in terms of tourist flow.

Finally, the framework meets the requirements of modularity and sustainability. On the one hand, it adapts to the complexity and characteristics of each local area, developing immersive and authentic itineraries that encompass the entire production chain and related stakeholders. This flexibility makes the framework applicable to a wide range of contexts, from marginal rural areas to peri-urban ones. On the other hand, the environmental and social dimensions of sustainability are appropriately integrated into the framework through the active involvement of supply chain stakeholders (equitable distribution of economic benefits while respecting local traditions) and the maintenance and/or restoration of ecosystem services.

4. Discussion

The effectiveness of thematic trails based on production chains depends on the proper execution of the operational phases and on a set of cross-cutting elements that ensure coherence and adaptability. These elements are discussed below, exploring their role and supporting their relevance with theoretical references and scientific literature.

The participation of local stakeholders is a pre-requisite for tourism development. When communities are involved as co-protagonists, the project acquires greater legitimacy and durability thanks to a stronger sense of belonging and shared responsibility. This approach fosters social empowerment and strengthens local identities, allowing tourism to become a tool for representation and not just economic gain [,].

The proposed framework is designed to be adaptable to contexts of varying size, stakeholder density and resource availability. Modularity allows each territory to adapt the thematic trail to its own characteristics and operational capabilities, in line with place-based development theories, which support the importance of policies tailored to local specificities with a bottom-up approach []. The ability of the framework to integrate different tourism dimensions (e.g., food and wine, nature, religion, industry) into a coherent and comprehensive offering is another aspect that contributes to the construction of a thematic trail. Multidimensionality, in fact, increases the attractiveness of the trial and allows for a diverse audience. This approach reflects the evolution of tourism oriented to slow and educational experiences [,].

The framework also contemplates the construction of a coherent narrative that supports and transforms the thematic trail into an experiential journey capable of engaging the visitor on an emotional and identity-building level. In this sense, storytelling enhances the histories and traditions of the geographical area involved. In the context of supply chain pathways, this means highlighting the human and cultural value of production as well as its technical aspects [].

The proposed framework also contemplates forms of shared governance between public, private and community actors. Local and interinstitutional networks foster coordination and access to financial resources or external expertise. In this sense, the framework is consistent with some of the literature that emphasizes the importance of trust in institutions and the ability to develop different kinds of collaboration as essential conditions for the development of a success model [,].

Finally, the framework can be oriented towards environmental and social sustainability, implying the need to define fair and eco-friendly tourism strategies that respect the carrying capacity of places and the local culture. This approach allows for the achievement of social equity objectives and the enhancement of local tangible and intangible heritage. Ecocultural pathways respond to this need, combining the protection of the natural landscape with the promotion of collective memory [,].

The proposed framework is also based on the identified cross-cutting elements, which constitute the fundamental pillars for the creation of authentic and resilient trails capable of generating value for the area and its inhabitants. Each area can adapt these principles to its own context. The literature contains several consolidated models that organically integrate elements similar to those of the “Thematic Supply Chain Trail” framework. For instance, some studies on ecocultural itineraries adopt an inclusive and transdisciplinary approach. Lukoseviciute et al. [] propose a strategy for the participatory development and management of ecocultural itineraries. The approach emphasizes shared governance and community engagement through focus groups and workshops at pilot sites. Ginting et al. [] highlight the importance of tourism governance from a sustainability perspective. Pulido-Fernández and Pulido-Fernández (2014) [] and Nunkoo [] focus on tourism governance by developing theoretical frameworks that include governance, stakeholder interaction and community participation. Giampiccoli and Saayman [] propose a community-based tourism model, found on the integration of the destination life cycle, community participation and the diversification of tourism offerings. Again, the proposed approach bears strong similarities to the “Thematic Supply Chain Trail” framework and its elements of community co-design and equitable benefit.

These studies highlight that many dimensions of the “Thematic Supply Chain Trail” framework are recognized and applied in academic studies on territorial trails and participatory tourism governance.

Overall, the comparison of the results with the literature suggests that the combination of various cross-cutting elements (i.e., community participation and co-design, networks and multilevel governance, territorial narrative, multi-thematicity and integration between different forms of tourism, modularity and sustainability) within a single integrated framework is the prerogative of this study (see also Section The Interpretation of “Thematic Supply Chain Trail” Framework). Furthermore, the discussion reveals tensions that challenge current theoretical interpretations. First, although the literature emphasizes the existence of cohesive stakeholder networks, the study highlights fragmentation and individualism among stakeholders, raising the question of the need for coordination and the willingness to share governance in marginalized areas. Second, the limited availability of hospitality infrastructure constrains theoretical models that emphasize experiential tourism as an sudden driver of local development, suggesting that the transition from production to tourism should be supported by a significant strengthening of public and private local bodies. Finally, this study integrates entire value chains of diverse nature and sector, extending its scope beyond traditional thematic trail models that primarily focus on single dimensions (e.g., environmental sustainability or gastronomy). These findings demonstrate the usefulness of more flexible and adaptive frameworks that recognize both the opportunities and constraints in translating local heritage into tourism products.

5. Conclusions

On the basis of the emerged findings, the present study proposed an operational framework for the creation of thematic trails based on local supply chains, tested in two Piedmont areas: the Biella area, for the dairy sector, and the Moncucco Torinese area, for the gypsum district. The analysis highlighted how the integrated enhancement of tangible and intangible resources combined with the active involvement of local communities, can be a strategic lever for the sustainable development of low-density tourism areas.

The framework stands out for its adaptability, making it suitable for regions with diverse characteristics and organizational capabilities. Furthermore, it systematically integrates various cross-cutting elements which strengthen its coherence and applicability in different contexts. Unlike other models in the literature, which often focus on a single dimension (e.g., environmental sustainability, food and wine tourism or community participation), the framework presented here proposes a holistic, scalable and replicable approach, capable of supporting the entire design and implementation process.

The study has significant implications from both a theoretical and a practical perspective. Theoretically, the framework helps fill a gap in the literature on place-based tourism by proposing a framework that integrates the production chain, local identity and active community participation. Practically, the framework offers a replicable methodology for public and private actors engaged in local development, interested in enhancing their local area through an inclusive approach. Furthermore, adopting the framework could boost local capacity-building processes, fostering the growth of planning and organizational skills among stakeholders. The focus on co-design and multilevel governance also stimulates greater cooperation between traditionally fragmented sectors, such as culture, agriculture and tourism. Finally, potential long-term benefits include the creation of new local economies based on the integration of production, culture and hospitality, the strengthening of a sense of belonging and local identity and the greater resilience of marginalized areas to economic and demographic crises. In addition, this research contributes to a deeper understanding of the role of thematic supply chain trails as tools for sustainable local development. The proposed framework demonstrates the importance of combining tangible and intangible heritage with participatory governance and scalability, elements that go beyond traditional one-dimensional models. This approach should also include a more in-depth network analysis of stakeholder collaboration, which could further strengthen the evidence and improve the robustness of the framework. This would also allow future research to more precisely measure the outcomes of thematic trail implementation, strengthening the framework as both a theoretical and operational tool.

The study has some limitations. First of all, recognizing the qualitative nature of the study, future research should focus on quantitative approaches, such as visitor surveys and economic impact assessments. Second, the empirical phase was limited to a limited number of actors and areas, which may reduce the homogeneity of the evidence. Finally, it was not possible to conduct an ex-post evaluation of the impact of the actions because, as already noted, part of the proposed framework has yet to be implemented.

Looking ahead, research could therefore develop along three main lines: (1) extending the framework to other geographical contexts or production chains (e.g., wine, textiles, ceramics); (2) analyzing tourism demand to identify specific targets, visitor needs and expectations; (3) evaluating the impact of the thematic trails developed after their implementation, through shared studies or mixed-method approaches.

In conclusion, the proposed framework represents an original contribution to the literature on place-based tourism, offering a concrete tool for participatory local planning and opening new perspectives for the cultural and economic regeneration of marginalized areas.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.B., I.T. and A.B.; methodology R.B., I.T. and A.B.; validation, R.B. and A.B.; formal analysis, R.B., I.T. and A.B.; investigation, I.T.; data curation, R.B., I.T. and A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, R.B., I.T. and A.B.; writing—review and editing, R.B., I.T. and A.B.; visualization, I.T. and A.B.; supervision, R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper is produced as part of the NODES project, funded by the MUR (Ministry of University and Research) with M4C2 funds—Investment 1.5 Notice ‘Innovation Ecosystems’, as part of the PNRR (National Recovery and Resilience Plan) funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU (Grant agreement Code No. ECS00000036).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Turin (protocol code 0669410, 24 September 2025).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Questionnaire track.

Table A1.

Questionnaire track.

|

References

- Hoang, K.V. The benefits of preserving and promoting cultural heritage values for the sustainable development of the country. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 234, 00076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, W. Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. In The Political Nature of Cultural Heritage and Tourism, 1st ed.; Dallen, J.T., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; Volume 3, pp. 469–490. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, L.S.; Rizzo, R.G.; Trabuio, A. Tourist Itineraries, Food, and Rural Development: A Critical Understanding of Rural Policy Performance in Northeast Italy. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, G.; Vieri, S. The food and wine tourism: A resource for a new local development model. Amfiteatru Econ. J. 2016, 18, 988–998. [Google Scholar]

- Briedenham, J.; Wickens, E. Tourism routes as a tool for the economic development of rural areas—Vibrant hope or impossible dream? Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, R.; O’Mahony, B. On the trail of food and wine: The tourist search for meaningful experience. Ann. Leis. Res. 2007, 10, 498–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, B. Food routes, trails and tours. In The Routledge Handbook of Gastronomic Tourism, 1st ed.; Dixit, S.K., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 393–400. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, R.C. Having your cake and eating it: The problem with gastronomic tourism. In The Routledge Handbook of Gastronomic Tourism, 1st ed.; Dixit, S.K., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Park, E.; Xu, M. Beyond the authentic taste: The tourist experience at a food museum restaurant. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 36, 100749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Kim, S.; Xu, M. Hunger for learning or tasting? An exploratory study of food tourist motivations visiting food museum restaurants. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2022, 47, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otgaar, A.H.; Van den Berg, L.; Feng, R.X. Industrial Tourism: Opportunities for City and Enterprise; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzior, A.; Lyulyov, O.; Pimonenko, T.; Kwilinski, A.; Krawczyk, D. Post-industrial tourism as a driver of sustainable development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujok, P.; Klempa, M.; Jelinek, J.; Porzer, M.; Rodriguez Gonzalez, M.A.G. Industrial tourism in the context of the industrial heritage. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2015, 15, 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.F. Tourist satisfaction with factory tour experience. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2015, 9, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.F. An investigation of factors determining industrial tourism attractiveness. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2016, 16, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro, Z.; Marques, J.; Sousa, C. Industrial tourism as a factor of sustainability and competitiveness in operating industrial companies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltramo, R.; Pairotti, M.B. Imprese & Territori. Come Costruire e Gestire il Prodotto Turistico “Visita d’Impresa”; Edizioni Ambiente: Milano, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bonadonna, A.; Duglio, S. A Mountain Niche Production: The Case of Bettelmatt Cheese in the Antigorio and Formazza Valleys (Piedmont–Italy). Qual. Access Success 2016, 17, 80. [Google Scholar]

- Duglio, S.; Bonadonna, A.; Letey, M. The contribution of local food products in fostering tourism for marginal mountain areas: An exploratory study on Northwestern Italian Alps. Mt. Res. Dev. 2022, 42, R1–R10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltramo, R.; Bonadonna, A.; Duglio, S.; Peira, G.; Vesce, E. Local food heritage in a mountain tourism destination: Evidence from the Alagna Walser Green Paradise project. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 309–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonadonna, A.; Duglio, S. Local Food Products as an Element for Fostering Sustainable Mountain Tourism in Marginal Areas: Some Evidence from North-Western Italian Alps. In Pro-Poor Mountain Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2024; pp. 196–212. [Google Scholar]

- Belliggiano, A.; Ievoli, C.; Bispini, S.; Conti, M. Food value chains configurations and resilience of rural mountain communities: Three dairy business models in central Apennines (Italy). Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1436214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widawski, K.; Oleśniewicz, P. Thematic Tourist Trails: Sustainability Assessment Methodology. The Case of Land Flowing with Milk and Honey. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, N.; Gretzel, U.; Waitt, G.; Yanamandram, V. Gastronomic trails as service ecosystems. In The Routledge Handbook of Gastronomic Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 169–178. [Google Scholar]

- Wojcieszak, M.; Gazdecki, M. Culinary trails as an example of innovative tourist products. Eur. J. Serv. Manag. 2018, 27, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaconescu, D.M.; Moraru, R.; Stănciulescu, G. Considerations on gastronomic tourism as a component of sustainable local development. Amfiteatru Econ. J. 2016, 18, 999–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Lukoseviciute, G.; Henriques, C.N.; Pereira, L.N.; Panagopoulos, T. Participatory development and management of eco-cultural trails in sustainable tourism destinations. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2024, 47, 100779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benur, A.M.; Bramwell, B. Tourism product development and product diversification in destinations. Tour. Manag. 2015, 50, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Shen, Z.; Teng, X.; Mao, Q. Cultural Routes as Cultural Tourism Products for Heritage Conservation and Regional Development: A Systematic Review. Heritage 2024, 7, 2399–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentz, M. The role of theme routes in the development of rural tourism. Int. J. Prof. Bus. Rev. 2024, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Fernández, M.; Pulido-Fernández, J. ¿Existe gobernanza en la gestión de destinos turísticos? PASOS—Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2014, 12, 685–705. [Google Scholar]

- Nunkoo, R. Tourism development and trust in local government. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boros, L.; Martyin, Z.; Pàl, V. Industrial tourism–trends and opportunities. Forum Geogr. 2013, 12, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampiccoli, A.; Saayman, M. Community-based tourism development model and community participation. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2018, 7, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Pedrosa, A.; Martins, F.; Breda, Z. The critical success factors for tourism routes development: A systematic review. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2025, 39, 3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouridaki, M.; Apostolakis, A.; Kourgiantakis, M. Cultural routes through the perspective of sustainable mobility: A critical literature review. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 26, e2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginting, N.; Gardiner, S.J.; Rahman, N.V.; Saragih, S.N. Towards a Conceptual Framework for Sustainable Tourism Governance: A literature review. Environ. Behav. Proc. J. 2024, 9, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatas, E.; Özköse, A.; Heyik, M.A. Sustainable Heritage Planning for Urban Mass Tourism and Rural Abandonment: An Integrated Approach to the Safranbolu–Amasra Eco-Cultural Route. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oikonomopoulou, E.; Delegou, E.T.; Sayas, J.; Moropoulou, A. An innovative approach to the protection of cultural heritage: The case of cultural routes in Chios Island, Greece. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2017, 14, 742–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogacz-Wojtanowska, E.; Góral, A. Networks or structures? Organizing cultural routes around heritage values. Case studies from Poland. Humanist. Manag. J. 2018, 3, 253–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottaviani, D.; Demiröz, M.; Szemző, H.; De Luca, C. Adapting methods and tools for participatory heritage-based tourism planning to embrace the four pillars of sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sannazzaro, A.; Del Lungo, S.; Potenza, M.R.; Gizzi, F.T. Revitalizing Inner Areas Through Thematic Cultural Routes and Multifaceted Tourism Experiences. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moliterni, S.; Zulauf, K.; Wagner, R. A taste of rural: Exploring the uncaptured value of tourism in Basilicata. Tour. Manag. 2025, 107, 105069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakya, M.; Vagnarelli, G. Creating value from intangible cultural heritage. The role of innovation for sustainable tourism and regional rural development. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Policy 2024, 14, 12057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haven-Tang, C.; Thomas, A.; Fisher, R. To What Extent Does the Food Tourism ‘Label’ Enhance Local Food Supply Chains? Experiences from Southeast Wales. Tour. Hosp. 2022, 3, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P. Toward a Theoretical Foundation for Experience Design in Tourism. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 543–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedram, B.; Emami, M.A.; Khakban, M. Role of the open-air museum in the conservation of the rural architectural heritage. Conserv. Sci. Cult. Herit. 2018, 18, 101–120. [Google Scholar]

- Shehata, A.M.A.E.R.; Mostafa, M.M.I. Open museums as a tool for culture sustainability. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2017, 37, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzić, A.; Bjeljac, Ž.; Jovičić, A.; Penjišević, I. Cultural Route and Ecomuseum Concepts as a Synergy of Nature, Heritage and Community Oriented Sustainable Development Ecomuseum “Ibar Valley” in Serbia. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chang, C.; Annerstedt, M.; Herlin, I.S. A narrative review of ecomuseum literature: Suggesting a thematic classification and identifying sustainability as a core element. Int. J. Incl. Mus. 2015, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndivo, R.M.; Cantoni, L. Rethinking local community involvement in tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 57, 275–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J. How does tourism in a community impact the quality of life of community residents? Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.; Farmer, J. Including the rural excluded: Digital technology and diverse community participation. In Digital Participation Through Social Living Labs; Chandos Publishing: Hull, UK, 2018; pp. 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Choi, H.C.; Jeong, C. Trails of Transformation: Balancing Sustainability, Security, and Culture in DMZ Walking Tourism. Land 2025, 14, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barca, F. The case for regional development intervention: Place-based versus place-neutral approaches. J. Reg. Sci. 2012, 52, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, P.R. Integrating factor analysis and the Delphi method in scenario development: A case study of Dalmatia, Croatia. Appl. Geogr. 2016, 71, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konu, H. Developing nature-based tourism products with customers by utilising the Delphi method. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 14, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoopetch, C.; Kongarchapatara, B.; Nimsai, S. Tourism Forecasting Using the Delphi Method and Implications for Sustainable Tourism Development. Sustainability 2023, 15, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peira, G.; Bonadonna, A.; Beltramo, R. Improving the local development: The stakeholders’ point of view on Italian railway tourism. Leis. Stud. 2023, 43, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltramo, R.; Peira, G.; Bonadonna, A. Creating a tourism destination through local heritage: The Stakeholders’ priorities in the Canavese Area (Northwest Italy). Land 2021, 10, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peira, G.; Pasino, G.; Bonadonna, A.; Beltramo, R. A UNESCO Site as a Tool to Promote Local Attractiveness: Investigating Stakeholders’ Opinions. Land 2022, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Reed, D.L. Stockholders and stakeholders: A new perspective on corporate governance. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1983, 25, 93–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, M. A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 92–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutanga, C.N.; Kolawole, O.D.; Gondo, R.; Mbaiwa, J.E. A review and SWOC analysis of natural heritage tourism in sub-Saharan Africa. J. Herit. Tour. 2023, 19, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).