Abstract

The world is urbanizing rapidly, and many urbanized regions deplete and degrade their environment. The additional polycrisis of climate change, biodiversity loss, epidemics, food insecurity, and reduced water, air, and soil quality asks for a transformational vision for the design and planning of these urban regions. Current planning practices are not able to respond to the complexity of the problems associated with the polycrisis. At the same time, regenerative thinking has not yet been practical enough to be accepted into spatial planning practices and create regenerative regions that can respond to the global polycrisis. This mismatch reinforces the status quo of well-thought-through regenerative frameworks on the one hand and ongoing spatial planning in urban regions on the other. The aim of this study is to create a regenerative framework for regional planning. A range of regenerative frameworks have been analyzed and integrated into one ‘framework of frameworks’, highlighting clusters of attributes describing the ‘what’, ‘when’, ‘how’, and ‘who’ of what needs to happen to create a regenerative world. On the other hand, expert judgement of planning practices in nine urban regions around the world provided insight about the priorities for regional regenerative development. This clarified the ‘what’ and ‘where’ of different aspects of urban planning in the region. Bringing the theoretical frameworks and practical understanding of urban planning together, the regenerative framework for regional planning provides a practical approach for navigating the complexities of creating a regenerative region. It starts by backtracking to the 1st generation city (of first settlements and indigenous understanding of the land). When this equilibrium is found, it is used to create a vision for the 3rd generation city (in which regenerative potentials are fully used). The comparison with the 2nd generation city (a current anthropogenic industrial city) clarifies what must change, how this change can be achieved, and who the agents of change are to make it happen.

1. Introduction

At a global level, an increasing number of scholars embrace the idea that a polycrisis [1,2,3] is emerging. This gives reason to fundamentally transform the approaches we use to shape our environment and societies. Anthropogenic [4,5] practices, which are mainly driven by human-centered thinking and economic exploitation, have led to ecological degradation [6,7], climate change [8], exhausted soil systems [9,10], interrupted water systems [11,12], overexploitation of natural resources [13,14], and social inequalities [15,16,17].

Generally, current spatial planning practices are not very well equipped to accommodate solutions for these increasing problems. Some say that the discrepancy between urban changes on the long term and planning for the short term prevents the realization of urban resilience [18]. The domination of short urban cycles makes long-term planning futile; disasters are not used to inform urban transformation and rigid planning systems restrict temporal flexibility in planning. Because spatial planning regulates the use of land and hence the scarce resources on the planet, it plays a central role in whether the polycrisis can be countered or will deepen. Therefore, spatial planning needs to be re-founded in ecological rationality [19]. Despite increasing attention on the relationship between human well-being and nature, this has not translated into growing attention on planning practices [20].

Scholars have developed several alternative concepts to redefine the relationship between human beings and nature [21]. These alternative concepts are based on the understanding that humans are a part of the natural systems around them [22,23] and we must live in symbiosis with it [24]. Moreover, all living beings have intrinsic value [25,26], and humanity should stop seeing nature as a resource but as something that must be protected regardless of its economic value to humans [27]. Nature is not simply another thing to be managed by people. Instead, we must ask the question, with whom (e.g., all organisms) do we as people interact and for whom (again, all organisms) are we as people responsible [28]. Nature also has (legal) rights [29] and plays an important role in regenerating both natural and social systems [30]. Nature operates as an interconnected myriad of human and non-human individuals and social-ecological systems [31].

We start the article with an exploration of the basic understanding of the different viewpoints regarding regenerative thinking (Section 2). After the methodological Section 3, we present the ‘framework of regenerative frameworks’ (Section 4.1), the outcomes of the comparative analysis of planning practices in nine urban regions (Section 4.2), and the final framework (Section 4.3). In Section 5, the results are discussed and conclusions are drawn.

2. Background

2.1. Spatial Planning Discourse

The root cause of the imbalance between the need to become more regenerative and the apathy of spatial planning to incorporate this in its approach can be found in spatial planning traditions, as indeed the core element in both positivist and post-positivist planning schools is the allocation of functions, translating to land use. Positivist approaches, which look for the ultimate truth, are based in science and top–down methods [32,33,34] and therefore require a lot of data [35]. In post-positivist planning schools, which take a specific perspective as the point of departure of the planning process, the allocation is driven by stakeholder interests or are market driven [33]. Especially when spatial problems are complex [36], it leads to simplification [37] in order to maintain existing system balances and turn them into spatial plans [38]. Therefore, the preferred modus operandi of most of theoretical and practical spatial planning [39] does not accommodate complexity, adaptivity, or temporal and spatial flexibility but prefers a specific topic above a holistic planning approach, focuses on developing an (unchangeable) blueprint plan, prescribes rules and regulations, and plans for the reiteration of the past. Alternative approaches can only come into view when western planning mono-rationality, in which planning plays by the rules, repeats prior experiences, and creates a ‘non-innovative status quo’, is left behind [40] and is replaced by an ‘unsafe’ planning practice of poly-rationality, where liquid, turbulent, or even wild boundaries of both planning thought and spatial territory can occur. This alternative would fit with the current complexity of problems apparent in the polycrisis.

Decisions about the future of (vulnerable) urban regions are, in current spatial planning processes, still made with a specific interest in mind (such as the ‘market’ or the stakeholders), rather than the intrinsic values of nature and landscape. In these processes, one-dimensionality and linearity are dominant factors determining what goes where in a given area. The choices and decisions are, as mentioned before, often incentivized by economic value prospects of land development and objectives to increase land value. Urban regions that encounter uncertainties and are threatened by unprecedented (climate) events and sudden changes are therefore ill-prepared if the value of land is the only criterium that matters. This is also the reason why so many cities suffer from disasters. Instead, spatial planning must gain the ability to instantly change the urban form and be flexible and adaptive enough to accommodate sudden changes. Such strategic planning is open to novel spatial paradigms and changes the way nature is seen (no longer as a resource to exploit for the benefit of the urban dweller).

To tackle the polycrisis, an approach to spatial planning is required that connects the long and short term and the large and small scale and has the power to simultaneously act swiftly. Two main problems stand in the way. The first one is that current spatial planning is too rigid to respond to and/or plan for the dynamics urban regions have to deal with. This leads to unnecessarily large impacts and disasters in these areas. Secondly, most regenerative frameworks are too abstract and lack the tools that can be used in spatial planning. Therefore, a new holistic framework (which integrates existing regenerative frameworks) is required that can be used in an adapted and simplified form in urban regional planning. This is our contribution to a new body of knowledge. To develop it, we have chosen two points of departure: the theory of regenerative thinking and the practice of planning in regional urban regions.

2.2. Regenerative Thinking

Regenerative thinking puts nature at the center. This distinguishes regenerative thinking from resilience and sustainability, as these concepts see the human system as the point of departure. Regenerative thinking includes complexity, non-linearity, and adaptation, e.g., ways cities should become less vulnerable to the unprecedented impacts of the polycrisis. Therefore, “a regenerative city can be the role model for an environmental and economic future path towards more resilience. This is not a final state in which the beginning and the end must be clearly defined. In fact, it describes a process of constant renewal and development” [41].

Many frameworks for regenerative development have been proposed. Although every framework has its own merit, each one is also created from a specific, sometimes biased, perspective. Where some lack a clear temporal aspect [42], others focus more on the processes [43,44,45], the necessary transitions [31,46], or take a more practical approach [47]. Moreover, many frameworks lack a spatial or design perspective. For widespread use of regenerative thinking, there are too many frameworks, they are too different, and they focus too much on process. When this spatial-temporal aspect is included in the framework [48], it comes at the cost of attention on processes and social aspects. In general, the matter of spatial scaling is overlooked, and when the focus is on abstract models, there is limited attention on practical applicability.

Thinking about regeneration is widespread yet diverse. ‘To regenerate’ means, according to the American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language and Merriam Webster Dictionary, to:

- Give new life or energy; to revitalize; to bring or come into renewed existence; to impart new and more vigorous life;

- Form, construct, or create anew, especially in an improved state; to restore to a better, higher, or more worthy state; refreshed or renewed;

- Reform spiritually or morally; to improve moral condition; to invest with a new and higher spiritual nature;

- Improve a place or system, especially by making it more active or successful.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the meaning is “changing the system into something different and better as well as to bringing about a thorough moral change or improvement.” Hence, this goes beyond reinvigorating or reviving the system or restoring it to a better state or condition. ‘Regenerate’ emphasizes not only new practices, but a new way of being [49]. “Regeneration puts life at the center of every action and decision. It applies to all of creation. Nature and humanity are composed of exquisitely complex networks of relationships, without which forests, lands, oceans, peoples, countries, and cultures perish. Vital connections between human beings and nature have been severed. The earth biological decline is how it adapts to what we are doing. Nature never makes a mistake. We do.” [50]. Therefore, we need to create the conditions for self-organization by listening to the stories of the original inhabitants that lived pre-colonization, pre-cultivation.

2.2.1. Regenerative Design

Regenerative design aims for the supply systems of energy and materials to be continually self-renewing, or regenerative, in their operation. A regenerative system can be achieved by reincorporating the basic life-support services of nature, such as energy conversion, water treatment, cycling nutrients, and waste assimilation, into the design of landscapes. The landscape is a medium for regulating flows and recycling resources [51]. Regenerative design applies technologies and strategies based on an understanding of the inner workings of ecosystems that regenerate socio-ecological wholes (i.e., generate anew their inherent capacity for vitality, viability, and evolution) rather than deplete their underlying life support systems and resources [42].

2.2.2. Urban Regeneration

Urban regeneration is often seen as the revitalization of an urban precinct, as it “seeks to bring about lasting improvements in the condition of an area that has been subject to change” [52], not necessarily the regeneration of resource flows or the societal system. Many urban regeneration initiatives aim at restoring the urban fabric in the intra- and peri-urban environment, turning run down industrialized areas into improved urban precincts. However, regenerative cities should go beyond this, “linking comprehensive measures for improving the conditions of city-life with measures for creating an environmentally enhancing, restorative relationship between humanity and the natural world” [53].

2.2.3. Regenerative Development

Regenerative development [42] is defined as a system of developmental technologies and strategies that works to enhance the ability of living beings to co-evolve, so that the planet continues to express its potential for diversity, complexity, and creativity [46] through harmonizing human activities with the continuing evolution of life on our planet, even as we continue to develop our potential as humans. Regenerative development provides the framework and builds the local capability required to ensure regenerative design processes can achieve maximum systemic leverage and support through time. It blends modern and ancient technologies to accomplish positive ecological and social results that include [54]:

- Improving the health and vitality of human and natural communities—physical, psychological, economic, and ecological;

- Producing and reinvesting surplus resources and energy to build the capacity of the underlying relationships and support systems of a place needed for the resilience and continuing evolution of those communities;

- Creating a field of caring for, commitment, and deep connection to places that enables the changes required for the above to take place and to endure and evolve through time [55].

“Development is the use of resources to improve the wellbeing of a society. What is called sustainable development is the use of resources to improve society’s wellbeing in a way that does not destroy or undermine the support systems needed for future growth. Regenerative development is the use of resources to improve society’s wellbeing in a way that builds the capacity of the support systems needed for future growth. What sustainable development is to traditional economic development, regenerative development is to sustainable development” [56].

2.2.4. Regenerative Culture

A regenerative culture is a culture that is consciously building the capacity of everybody in a particular place to respond to change and accepts transformation as something that life just “does” [57]. It facilitates the healthy personal development of a human being and the evolution of consciousness to (eventually) a cosmos-centric perspective of the self. It unfolds the potential for a compassionate, empathic, and collaborative culture of creativity and shared abundance, driven by biophilia [32] (p. 35).

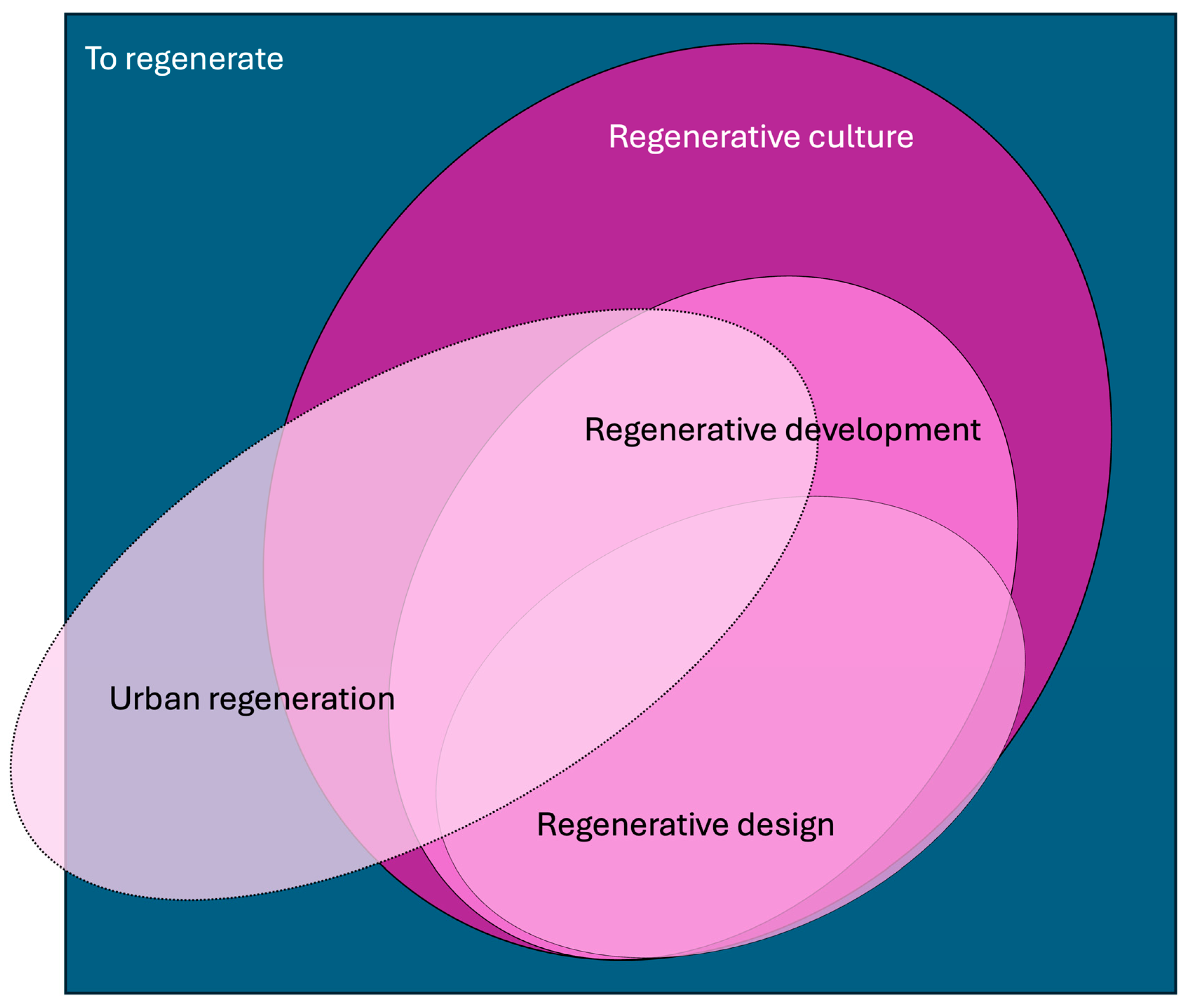

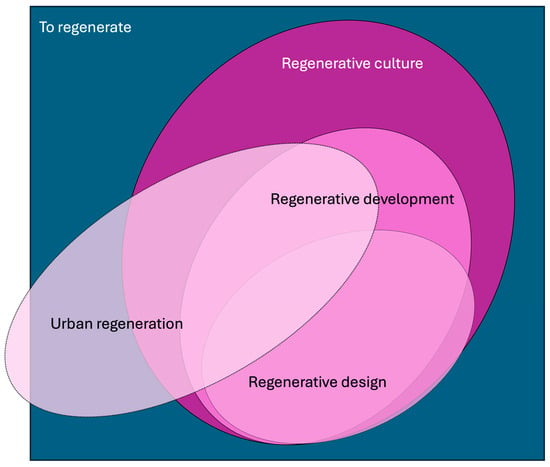

In summary, the different definitions of regeneration overlap (Figure 1). Regenerative culture aims to embrace both regenerative design and development, and it includes parts of the urban regeneration principles, as these are not always entirely focused on the regeneration of environmental resources [52]. The overlap between regenerative development and design is also partial because development includes a broader spectrum than that served by the (spatial) design disciplines (such as psychology or the deep connection to place) [55]. Urban regeneration overlaps with all three other forms of regeneration but can also have adverse effects in the form of using more resources than can be regenerated, and therefore, it is partly placed outside the ‘to regenerate’ box. This article focuses on creating a regional regenerative framework and starts from the spatial perspective (design) to subsequently embrace regenerative development and culture from there.

Figure 1.

Interconnectedness of regenerative concepts (by the author).

3. Methodology

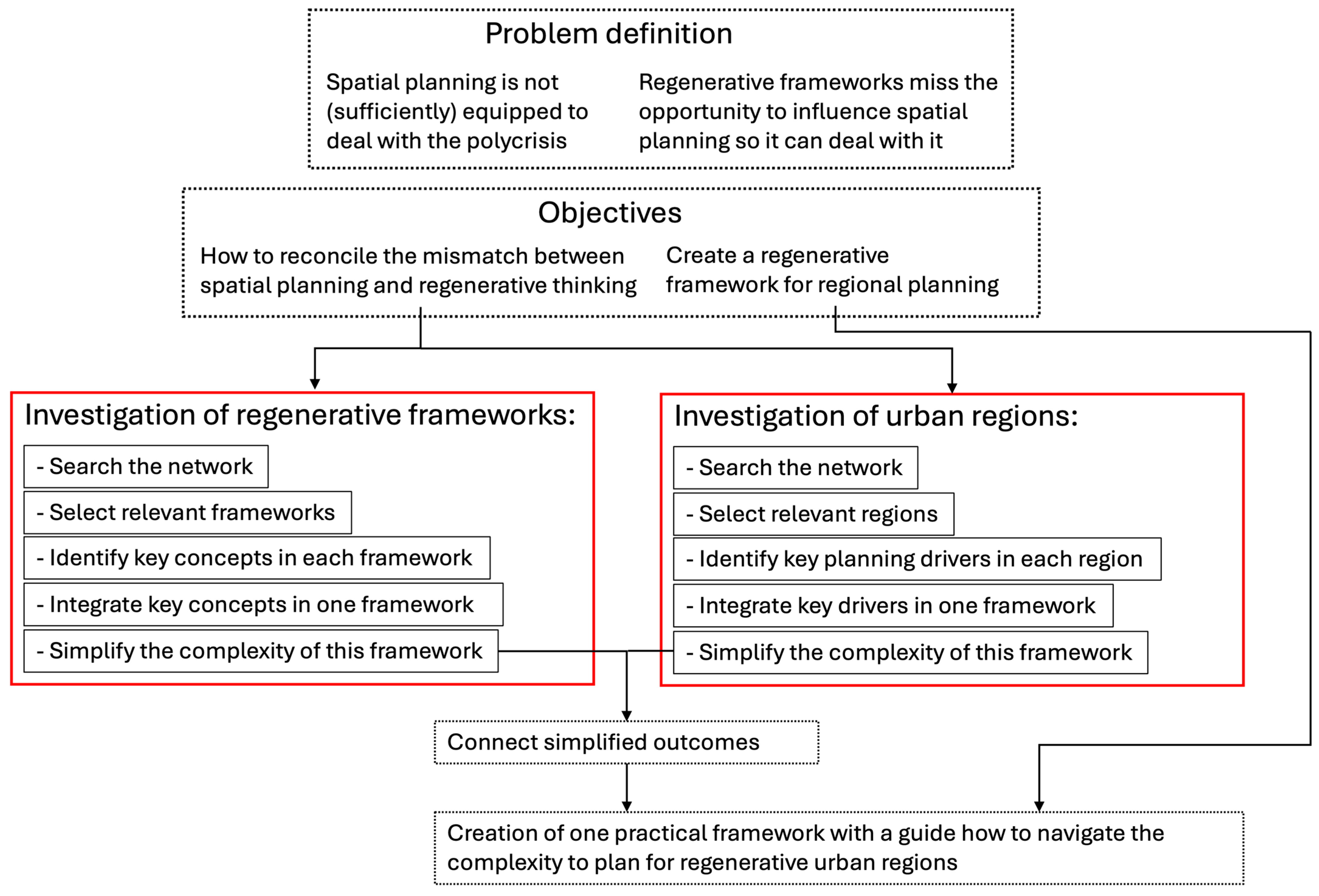

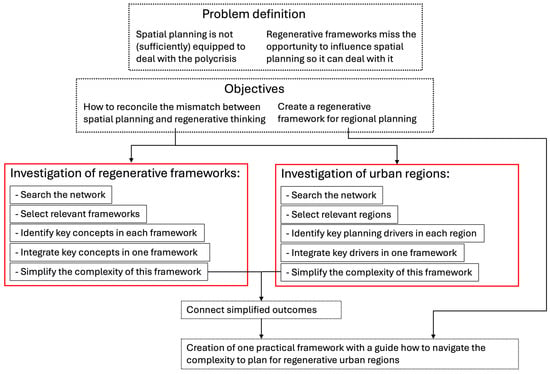

The goal is to reconcile the mismatch between a failing spatial planning system and the impotency of regenerative frameworks, transforming spatial planning into a system that could create regenerative regions. The main research question is how to create a regenerative framework for regional planning. To tackle this question, a mix of methods was used (Figure 2). Two pathways of investigation were distinguished: a theoretical pathway, investigating existing regenerative frameworks, and a practical pathway, exploring existing urban regions.

Figure 2.

Methodology.

3.1. Investigation of Regenerative Frameworks

This investigation consisted of several steps.

- a.

- The first stage was to undertake a literature and Google search for existing frameworks (using the terms regenerative, regeneration, and framework).

- b.

- A selection of the found frameworks was made based on the following criteria:

- -

- What are the dimensions used in the framework: does it include spatial or time dimensions, does it relate to cultural, physical, or social dimensions, is it nature driven or human centric?

- -

- What are the main fields of attention: is it focused on socio-psychological or transformational processes, which content is part of it, do spaces, places, and areas play a role?

- -

- What are the key characteristics of the framework: which principles for regeneration are distinguished?

- -

- What keywords represent these characteristics?

The following frameworks were selected: the civic transformation framework [31], the four returns framework [48], the regenesis framework [42], five key principles for regeneration [43], biomimicry design lenses [45], worldview shift and transformed relationships [58], eight principles for a regenerative future [48], and regenerative design [47]. This selection includes traditional, well-established frameworks, such as the regenesis framework [42], which are combined with frameworks in the field of civic transformation [31], landscape [48], or biomimicry [45]. This selection also implies that not all frameworks could be included, such as the LENSES framework [59,60], certification programs [61] such as LEED, Greenstar, and BREEAM [62,63], or the living building challenge [64]. - c.

- The key concepts were identified. Every framework has specific characteristics and focus. In abstraction, their main vocabulary is often represented in a diagram that shows the interrelations and coherence between all the parts. These terms were identified and selected to be included in the integration framework.

- d.

- Integration of concepts. The compilation of frameworks was undertaken by understanding the abstraction level of each of the frameworks. Some are generic while others are more specific. The sequence for creating the integration started with the generic and included the specific ones after.

- e.

- Simplification of the framework was needed because of the large number of key concepts. The method in this last step was to cluster the key concepts into a couple of coherent groups, which were predefined (what, who, when and how). Each key concept was linked to one of these clusters.

3.2. Investigation of Urban Regions

The investigation of urban regions also consisted of several similar steps.

- The search for urban regions was carried out by searching the network, both online and through the academic networks of the authors.

- The selection of urban regions was based on several criteria: geographical spread over continents, climatic and landscape variety, different cultural backgrounds, a range of socio-economical stages of development, different political systems, and size of the population. Willingness to participate in this investigation and availability to provide the geographical data and participation in the workshop were also important. In total, nine regions were selected: Monterrey (MEX), London (UK), Kharkiv (UKR), Pretoria (SA), Guadalajara (MEX), Port Moresby (PNG), Randstad (NL), Medellin (COL), and Queretaro (MEX).

- For each city, the key planning drivers were mapped. Each urban region was mapped at the same scale and the same size of 80 × 80 km. Although this size might appear arbitrary, it was chosen because all regions with their urban cores and urban–rural fringes fit in this square. Moreover, the relationship between urban settlements and the surrounding landscape could be included within this area. In every urban region, local experts were asked to deliver basic information about their region. The following layers were collected and used to integrate into one map per region:

- -

- Elevation contours illustrating the steepness of slopes connecting these with the main green and natural spaces and the existing urban area;

- -

- The space for the existing water system, including the main waterways (rivers and creeks), and the boundaries of (sub)watersheds;

- -

- Current biodiversity, existing ecosystems, and forests;

- -

- Possible areas for the development of new forests;

- -

- Existing urban agriculture practices in the urban, peri-urban, and urban regions;

- -

- Historic urban growth or decline in development stages of roughly 10–20 years, if possible, including the expected urban development;

- -

- Main infrastructure, such as public transport and the main road system.

Every map had the same legend/key, which was necessary to make all regions comparable. The maps were finalized centrally to make sure the maps were similar. - Each region was different but showed the same aspects on the maps. In this step, the findings of every region were integrated. For this integration, representatives came together for an intensive workshop of six hours during the International Symposium of Regenerative Regions, held in Monterrey in March 2024. During this symposium, the regional maps were presented, and the planning drivers of each region were discussed and ranked by the experts. The higher the rank, the more significance for creating a regenerative region. Moreover, in a separate discussion, other major driving forces were identified that shape an urban region.

- After creation of the maps and the ranking of regenerative planning drivers, the findings were linked to the SDGs, based on the order of objectives as proposed in the so-called ‘wedding cake’ [65,66].

The methodology for integrating the theoretical regenerative framework and the urban regions findings was based on the relationship between process and design. The underlying assumptions were that humans are seen as part of nature, an open mind is deployed so the world can be seen in new ways, the designer is given a new role in which eco-socio-cultural and psychological literacy plays a major role, and in the process, the goal is to improve the value of the whole system by working developmentally [67]. The new regenerative framework for regional planning deployed these values by simultaneously creating the environment (the design) in which people and living systems can then create their new potential (the process). Or in reverse order: to identify the process of creating new potentials by crafting a design that enhances this. The genius loci, or the specific place, was placed central to create a local narrative by understanding the complex, adaptive, and dynamic patterns as parts of a bigger picture [49]. In this way, it bridged the biophysical and social-ecological systems [68].

The integrated framework started with the design proposition (the ‘what’, ‘when’, and ‘where’), which shaped the conditions and spaces for natural and human systems to fill (or deploy) their potential (the ‘who’ and ‘how’) in this spatial condition. Besides this, a proposal for navigating the new framework was developed by organizing the progressive steps and feedback that can be used during the planning process for creating regenerative regions.

4. Results

4.1. Regenerative Frameworks

The nine frameworks and approaches to regenerative thinking were analyzed and subsequently used to build up a narrative for an integrated regenerative framework. The sequence of the story used the generic frameworks first, before detailing the integrated framework with specific elements of the other frameworks and approaches.

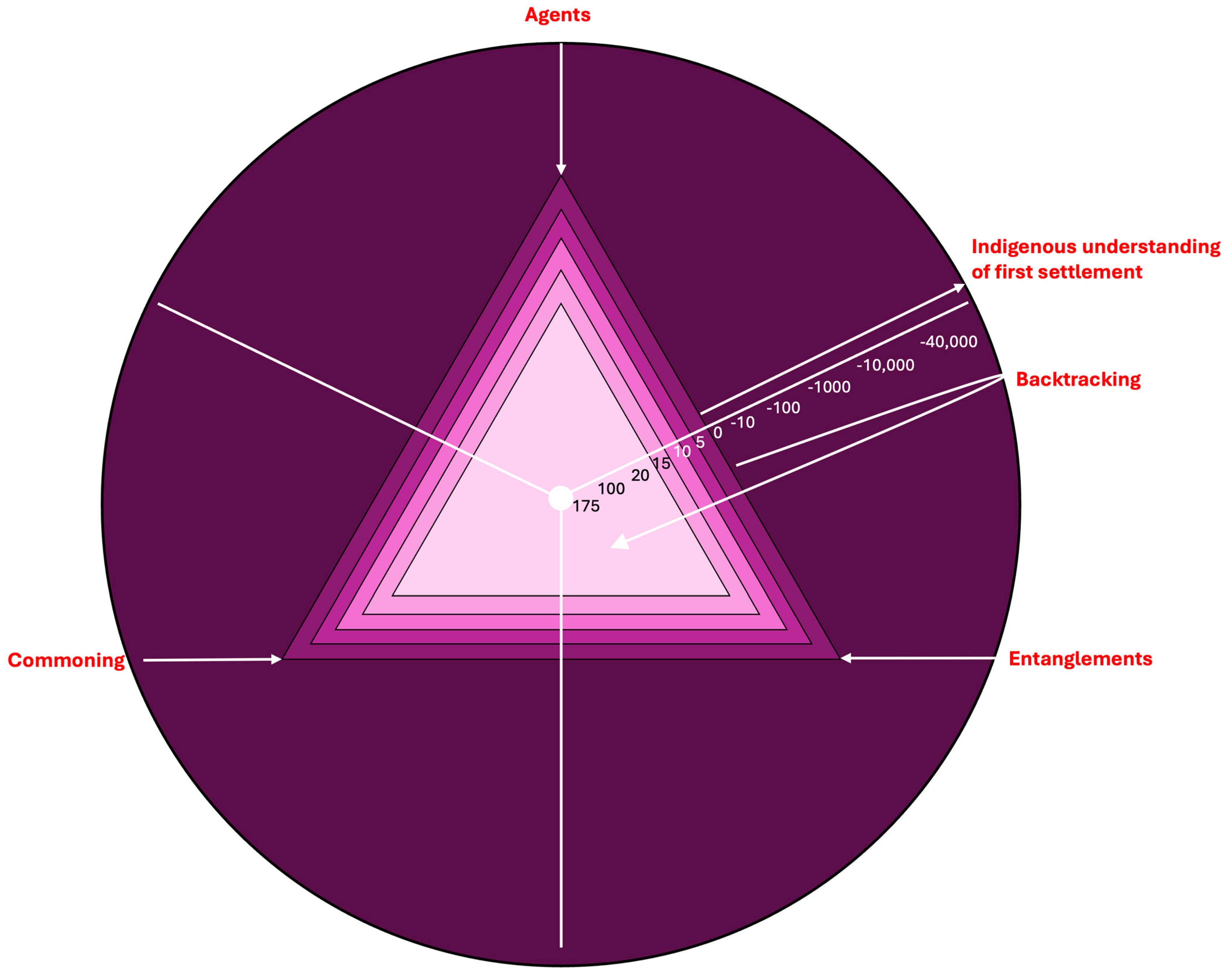

The civic transformation framework [31] was used as the basis. The reason for this is that this framework describes meta-transformations that are happening or are needed in civic society. Three transformations are at the core of this framework:

- The transition from objects to agents. Everything, human beings and non-human organisms, has agency in reimagining the relationships with the land, built on care, mutuality, and reciprocity.

- From externalities to entanglements. Because everything is connected to everything [69], the current economic definition of value denies the complex system of relationships. The complex entanglement of relationships between agents determines the value of all individual species, geographies, and the biodiversity of ecosystems.

- From the private–public dichotomy to commoning. Global challenges such as pandemics, climate change, or growing inequality transcend our constructs of boundaries, departments, and disciplines and cannot be solved by the government or the private sector. Therefore, decision making over shared resources should be reconsidered. Commoning (or becoming in common [70]), could guide planetary collaboration, the way resources, materials, and spaces are used, and how shared risks could be solved.

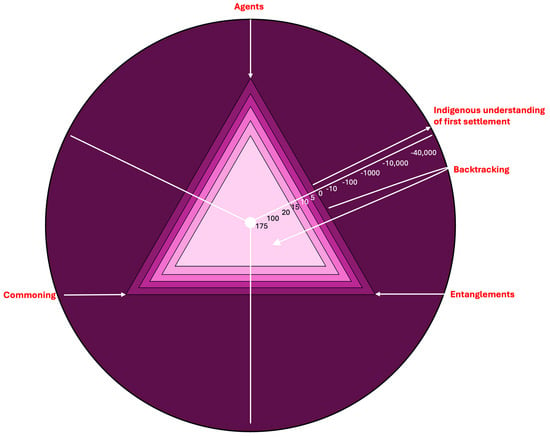

Commoning, entanglements, and agents formed the three cornerstones of the framework. Because civic transformations have determined the way of living together for a long time, and will do so in the far future, the depth of the model showed the connection to country as embraced in nearly all traditional and indigenous cultures [71,72], up to 40,000 years back. This was the reason for integrating the timeline in the framework, so that an ongoing civic transformation could emerge from the past to the design for seven future generations [73,74], for more than 175 years (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Integrating regenerative frameworks: step 1 | new agents | based on [31].

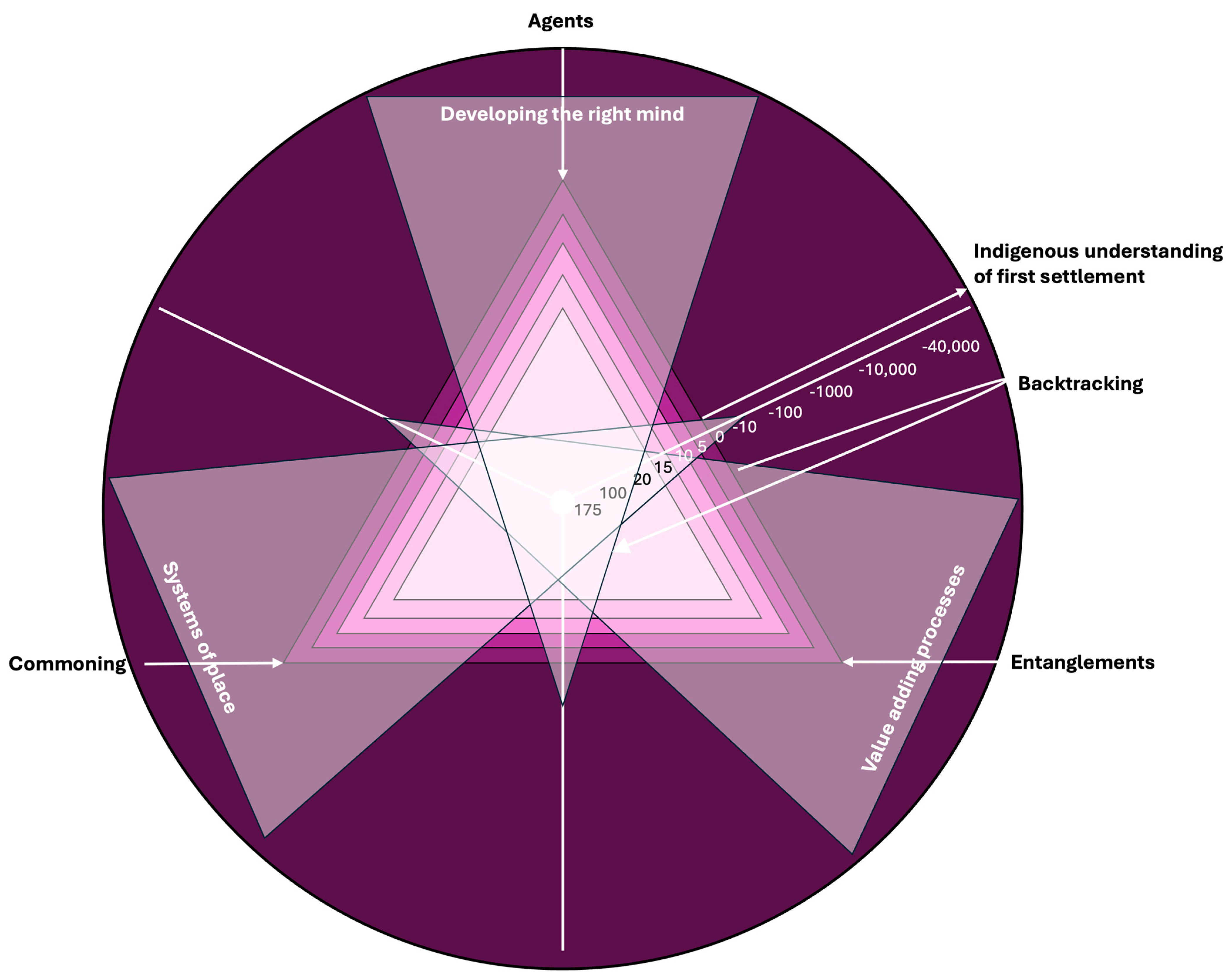

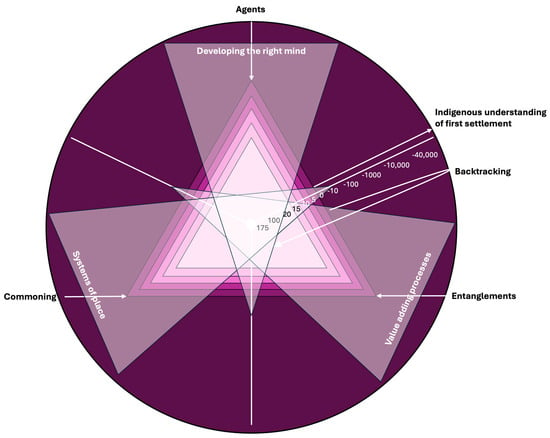

The three key dimensions of the regenesis framework [42] were subsequently connected to this model (Figure 4). The systems of place (ecologically, social and culturally) were linked to commoning, where resources, responsibility, materials, and places are shared. The value adding processes, such as providing food and shelter, transacting and adorning, and recreating and communing, fit with the entanglements. Finally, the development of the right mind (function, being, will) focused on the agents in a process of growing awareness, consciousness, and conviction.

Figure 4.

Integrating regenerative frameworks: step 2 | adding the regenesis framework | based on [48].

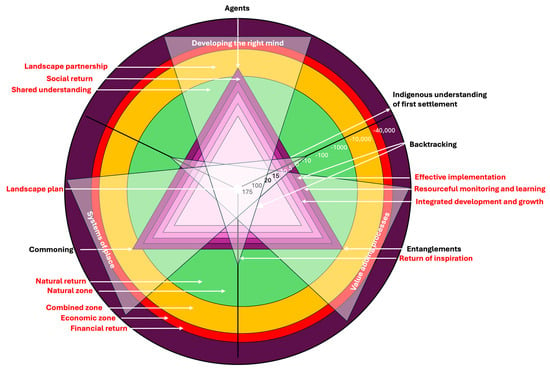

The four returns framework [42] was the third addition. It involves the shared understanding and establishment of a landscape partnership, developing a landscape plan, implementation, and monitoring. These aspects were located in the framework close to the agents, entanglements, or commoning (Figure 5). Moreover, the type of return (inspiration, social, natural, or financial) was similarly placed in the framework. As layers beneath the civic framework, the zones of intensity were integrated: the lowest intensity in the biggest natural zone, the intermediate intensity in the combined zone, and the largest intensity (and smallest size) in the economic zone. Finally, this framework was aligned strongly with the long timelines of the relationship to country by defining landscape returns to periods of at least 20 years.

Figure 5.

Integrating regenerative frameworks: step 3 | adding the four returns framework (new concepts in red) | based on [48].

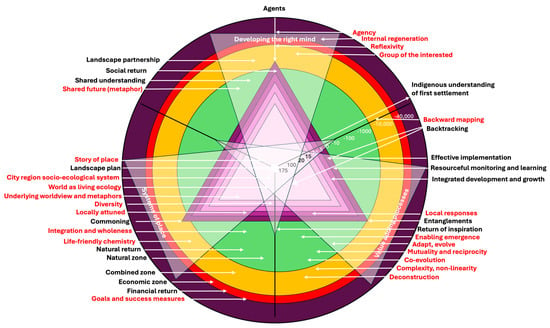

Figure 6 shows the integration of the key concepts of five separate frameworks. We have included this in one figure because each concept is located in the model shaped by the civic transformation, the regenesis, and the four returns frameworks, but the visual itself does not change.

Figure 6.

Integrating regenerative frameworks: step 4 | adding new worldviews [58], regenerative futures [44], biomimicry [45], and regenerative principles [43] (new concepts in red).

The ‘five key principles for regeneration’ [43] added aspects from an ecological worldview: reflexivity, mutualism, agency, and diversity. ‘Biomimicry design lenses’ [45] added adaptation, being locally attuned and responsive, integration of development with growth, being resourceful with materials and energy, applying life-friendly chemistry, and evolving to survive. The ‘shift in worldview’ [58] introduced living systems, a world as a living ecology, integration and wholeness, complexity and non-linearity, enabling and emergence, local responses, and mutuality and reciprocity, while ‘new relationships’ emphasized reciprocity through embedding projects in a network of many agents in the city, the regional community, and the ecological system. Finally, the ‘regenerative futures framework’ added eight principles [44]: the story of place, the underlying worldview and its metaphors, goals and success measures, a shared image of the desired future, deconstruction, backward mapping, co-evolution of human and natural systems, and the cultivation of internal self-regeneration. All key concepts are represented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of regenerative frameworks and approaches, their key concepts and belonging.

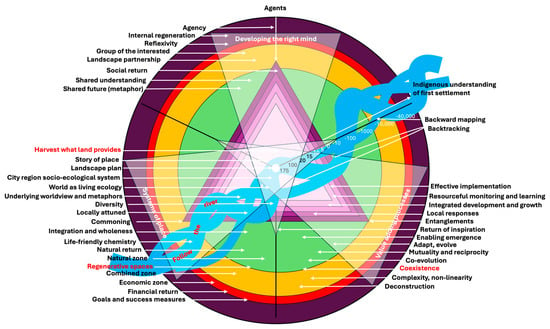

The integrated framework of regenerative frameworks and approaches was finalized by adding key elements of the ‘regenerative design principles’ [47]. A key concept in this framework was the suggestion to follow the river, as an underlying current, connecting and flowing through the framework. This must be seen as a metaphor for life. It always continues, flows, and creates shapes in the landscape. It is also the source of life, as it brings water to the land for fertilizing the soil and growing food. It is the ultimate connection between human and natural systems, as it gives people the resources to live and also as an ecologically enriching natural system itself. Metaphorically, it may lead us through different places, times, and stages of development, connecting the different aspects of regeneration. Furthermore, it shows us the reason for mutual coexistence of human and non-human organisms in ecosystems, it creates regenerated spaces as closely as possible to their natural state, and it allows for productive landscapes so we can harvest what the land can provide (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Integrating regenerative frameworks: step 5 | adding regenerative design principles, new concepts in red | based on [47].

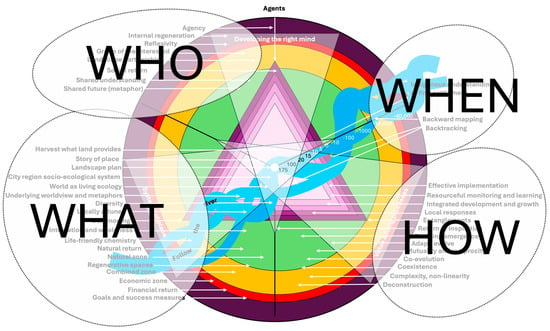

The key concepts were allocated according to their intrinsic role in the process of regeneration (see Table 1 and Figure 8). Some of the concepts discuss the understanding of time and the past (WHEN), others focus explicitly on the content (WHAT), the way to achieve regeneration (HOW), or the responsible people, institutions, or groups (WHO). Now that the characteristics were placed in the framework, the coherence became clear. Central in this was the symbol of the river, which could be followed to establish the most regenerative outcomes for the region. If we follow the river, the long history of the place is connected with a future vision of the long-term landscape plan, which is driven by reciprocity and mutuality and sees the world as a living system. In this shared future of commoning, the city and region form one socio-ecological system, where regenerative, life-friendly places provide the return of inspiration. Co-evolution and emergence are key processes to provide continuous adaptation to change. A shared understanding and relationship to the land guides local responses and harvesting what the land provides.

Figure 8.

Key concepts clustered according their role in the regeneration process.

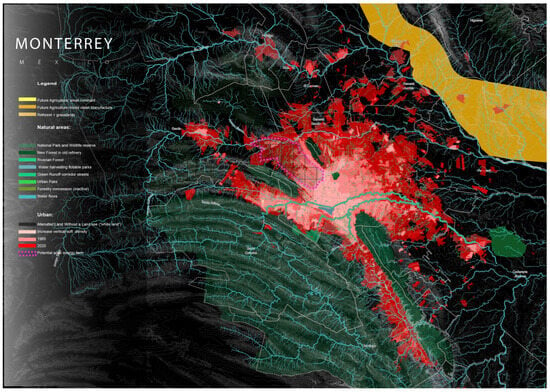

4.2. Regenerative Regions

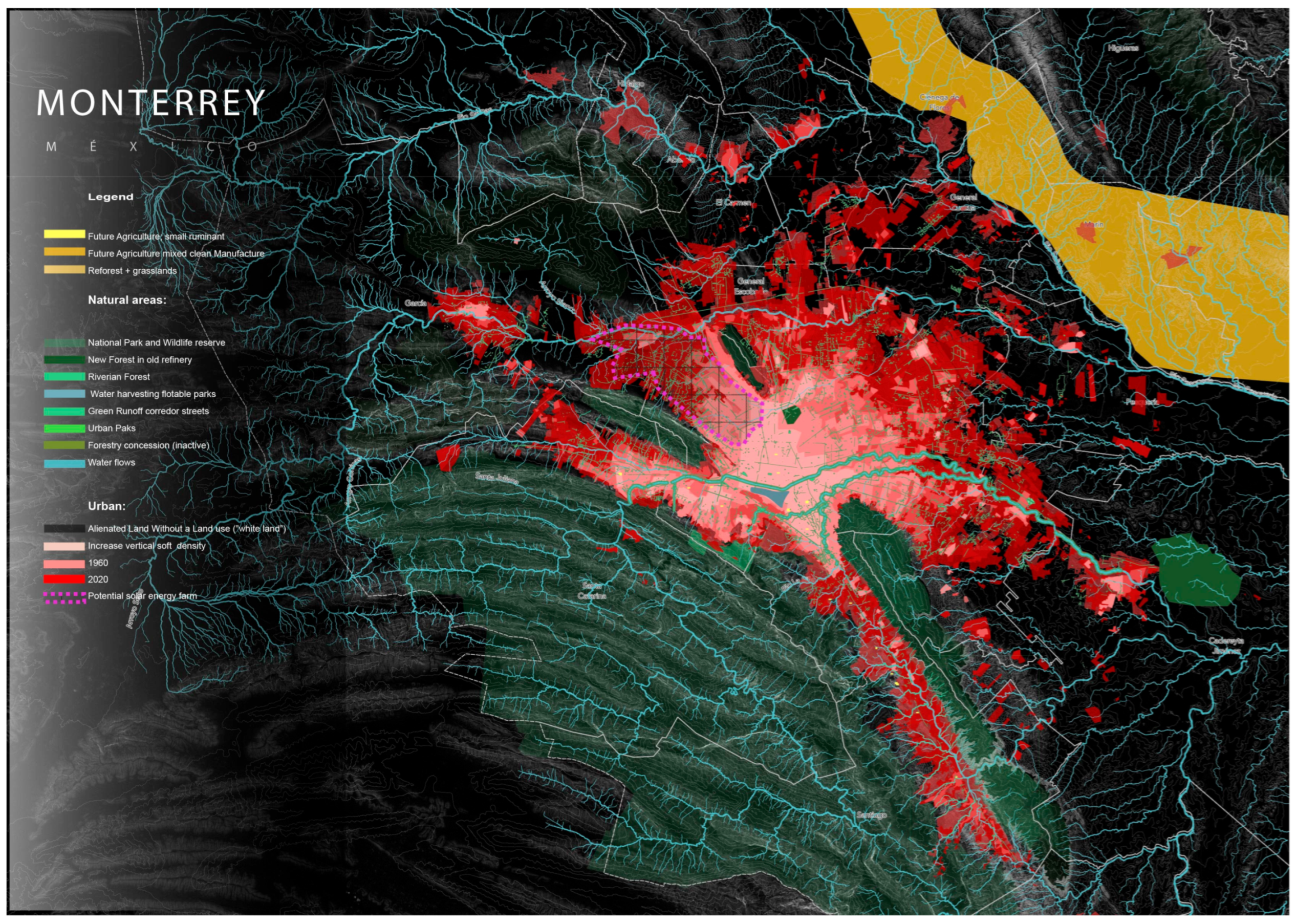

The nine regions were mapped in a comparable way, see the Monterrey version here as an example (Figure 9). The maps showed the differences between regions and also the dominance of some aspects over others, such as density/compactness, the landscape qualities, the role of water, green and natural areas, etc.

Figure 9.

The map of the Monterrey metropolitan region, one of the nine analyzed regions (credit: Rodrigo Junco).

The question of what the main spatial aspects are for creating a regenerative region was qualitatively assessed by local experts of these regions. In total, the experts identified 13 aspects that play or could play important roles in developing the regenerative potentials of urban regions. The relative importance of each aspect was estimated by expert judgement (Table 2). When the rankings of each aspect were combined, the most relevant regenerative aspects emerged: (1) landscape; (2) land; (3) politics; (4) elevation; (5) water; (6) food; (7) ecology; (8) infrastructure; (9) culture; (10) housing; (11) safety; (12) relationship to country; and (13) industry.

Table 2.

Overview of urban regions, their characteristics, and relative importance of key aspects.

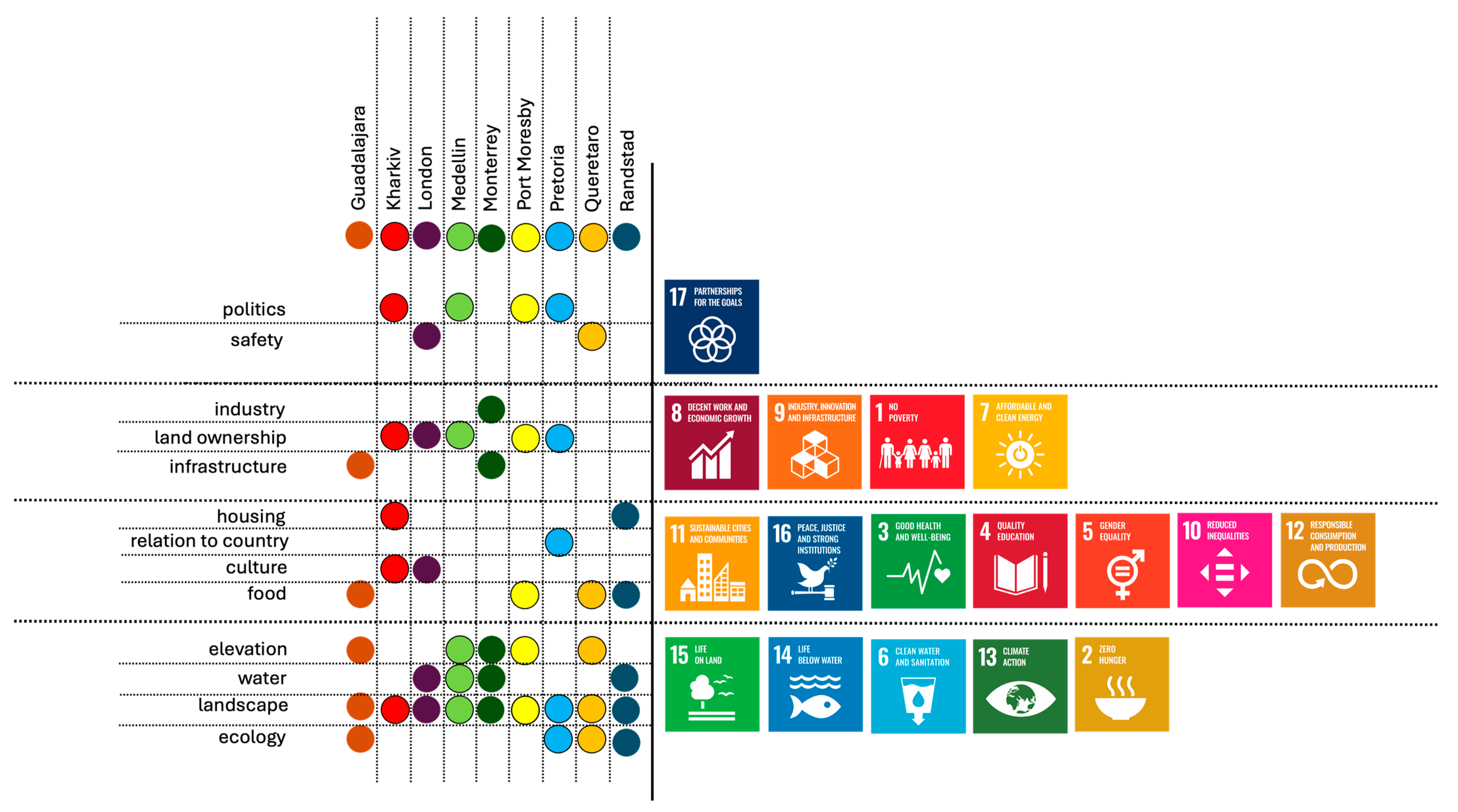

The order of concepts could be questioned because of the number of regions involved and the qualitative assessment method; however, it gives the first insight into what experts generally think the main aspects in a regional planning framework should be. When we assessed the top five aspects in every region and correlated these to the SDGs, the dominant group of aspects belonged to the biosphere base of the SDG wedding cake [75,76], with a second large group connected to the social layer and, except for land ownership, an even smaller portion connected to the economic and political layer (Figure 10). This reconfirmed the order of aspects as proposed by Folke and colleagues [75] and Rockström and Sukhdev [76].

Figure 10.

The key urban planning aspects linked to the SDG’s.

To use these findings in the final framework, the point of departure should be to allocate the aspects belonging to the biosphere (the base of the cake) in the region first, followed by social, economic, and political aspects.

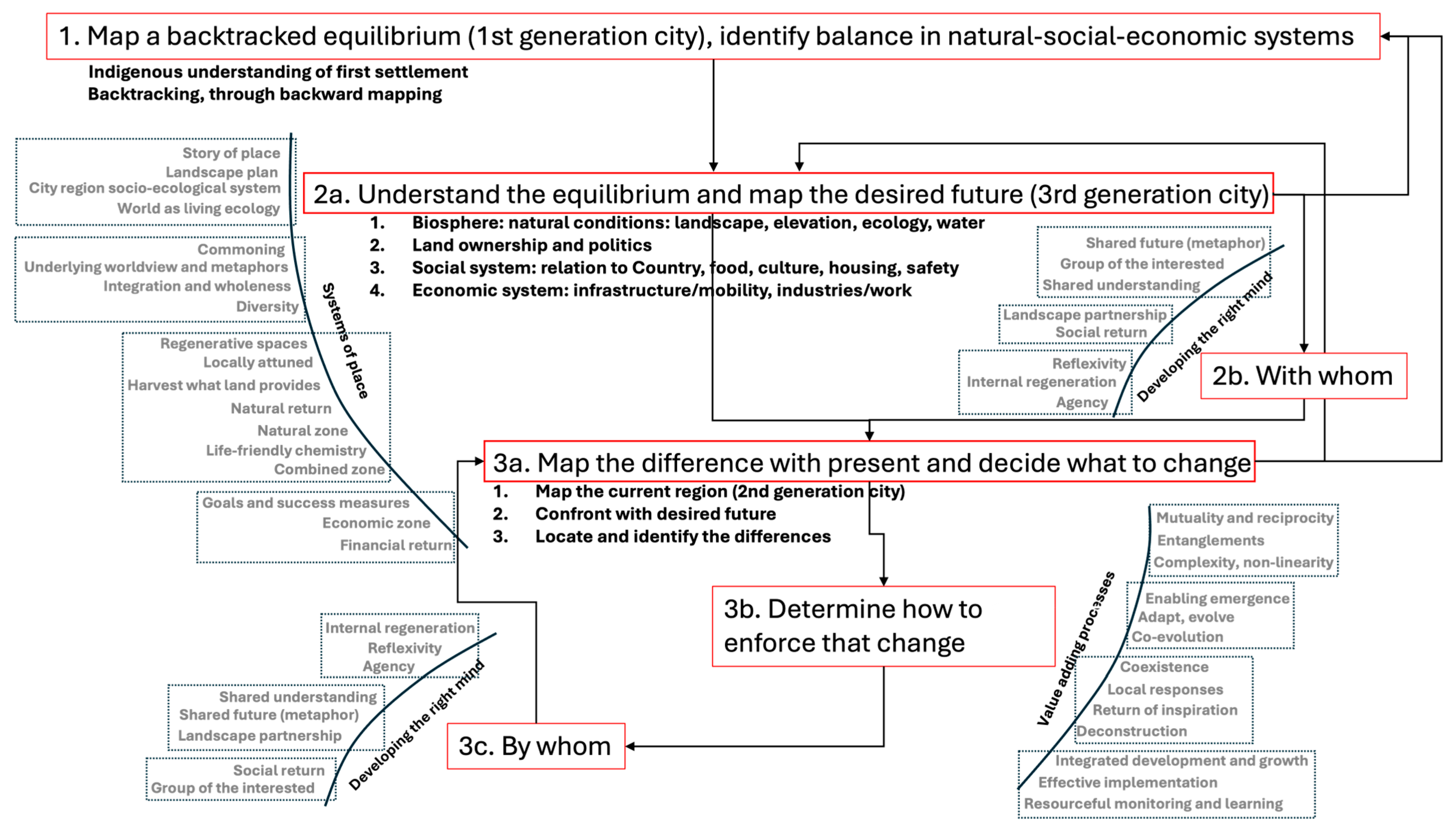

4.3. Regenerative Framework for Regional Planning

To address the core question of how to practice spatial planning in a way that intrinsically designs regenerative regions, the theoretical regenerative framework of frameworks (Figure 8) needed to be connected to regional spatial conditions whilst prioritizing the biosphere aspects. In simple wording, the ‘what’, ‘when’, ‘how’, and ‘who’ needed to be projected onto the regional map (the ‘where’). The proposed framework not only emphasizes the elements of the framework, but it also suggests how to navigate its complexity.

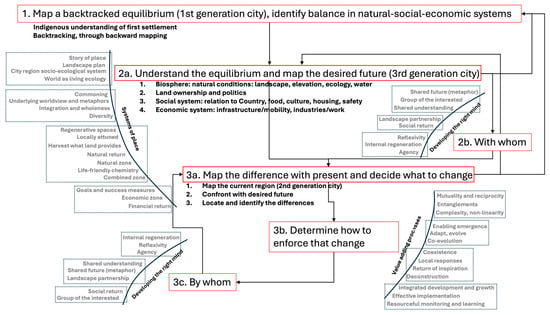

The regional planning framework consists of three stages (Figure 11):

Figure 11.

Comprehensive regenerative framework for regional planning, including ways to navigate its complexity.

- Understanding the past, present, and future of the region (the ‘when’) by mapping the backtracked equilibrium [77]. In search of a sustainable balance between the natural conditions and the socio-economic system, traditional knowledge about the relationship to country of indigenous peoples, at a time when first settlers started to build the city [71,72], was used. The map shows the natural resources and their reciprocal relationships with the use of resources in the early settlement, understanding the natural, urban, and social origins of the region. This explains how their relationship to country determined how people used resources, and how their reciprocal relationship with their environment established the sustainable equilibrium. This first-generation city [78] was the moment that the first settlers encountered the place and built a small settlement. Often these settlers were indigenous people, who in many cases were nomadic and stayed in different places in the region.

- Once this equilibrium was understood, it could be used as an inspiration to design the desired future for the area (Figure 11(2a)). For this third-generation city [78], the future can be twofold. Either the region will fall into ruins and nature re-occupies the place, eventually returning it to a natural reserve, or, the region continuously reestablishes an equilibrium in which natural and human resources are constantly regenerated. This requires planned flexibility and the establishment of adaptive processes, which allow nature to guide and direct urban uses in the city. As the urban regions highlighted, this starts with the natural aspects (landscape, elevation, water, and ecology), the elements that are essential to guarantee life in the long term. Secondly, the way landownership and politics support these aspects guide choices about land use. Within this spatial structure, social aspects were allocated, such as where food was grown and housing fit. Finally, the supportive infrastructure and the working locations and industry could be placed in the remaining spaces. All attributes of the systems of place (Figure 11) were applied in order to map out which specific regenerative potentials should be deployed, emphasizing the way people in the future reciprocally use the available resources. The desired future of the area told the story of place in a landscape plan, which communed and integrated the socio-ecological city-region as a diverse living system. It provided natural and social returns and harvested what the land provides (Figure 11(2a)). During this second stage, it was essential to design the process with which to envision this desired future (Figure 11(2b)), using the attributes of developing the right mind to establish a shared understanding about the future amongst a selected group of interested partners who want to take responsibility.

- Once the desired future was mapped, the differences with the current, second-generation city [78] were identified. This second-generation city is the region as we know it now; often an industrialized, anthropogenic city driven by economic forces and degenerating its environment. After mapping the natural, social, and economic systems of the current city, these could be compared with the same systems in the desired future (Figure 11(3a)). Again, all attributes of the systems of place were used here. The required change was the difference between the desired future and the current situation. Following this, the process of how this transformation from current to future can be achieved used all attributes of the value adding processes (Figure 11(3b)), enhancing the complex processes of adaptation, emergence, and reciprocity, so local responses could be effectively implemented. Finally, the agency of local interested groups was brought in, which have a shared understanding and the capacity of internal regeneration to establish landscape partnerships and social returns (Figure 11(3c)), the attributes of developing the right mind.In this way, the regenerative framework for regional planning started from understanding the basic balances in the region as a basis for creating a shared future vision, which then, by comparison, showed the gaps and transformation needed for reaching that future, the ways this can be achieved, and the agents who are required to realize that shared future. Within the framework, several feedback loops were included to reconnect the latter stages with the first ones.

5. Discussion

A framework is a framework and can be used or not [79]. There is not a clear definition, use, or common application of a framework. The purpose of a framework varies across disciplines [80]. Nevertheless, there are many qualifications that are deemed to describe what a framework is. According to the Cambridge Dictionary, it is seen as a system of rules, ideas, or beliefs that provide a foundation for inquiry [81] to connect different ideas [82]. It consists of a set of plurals and connected assumptions, concepts, values, and practices, able to develop a common language [83] as a basic vocabulary to organize diagnostic, descriptive, and prescriptive inquiries [84] and assist in analyzing complex, nonlinear interdependencies [85].

The state of global problems is complex and multifaceted, also called a polycrisis [1,2,3]. This complexity makes current spatial planning redundant. However, a possible alternative is not readily available. Potentially, regenerative thinking could offer this alternative, but the many regenerative frameworks are too abstract for application in spatial planning. This mismatch is not the cause of inadequate planning and cities that are ill-prepared for the consequences of climate hazards and other significant changes. When a regenerative framework, however, matches the practice of spatial planning, it will bring an opportunity to urbanized regions to move in the direction of becoming regenerative.

The theoretical regenerative frameworks used in this study contain a richness of concepts and articulate the need for holistic planning. This content was used to create one ‘framework of frameworks’, simplifying the complexity without losing its richness. Each key concept can be used in different stages of the planning process. Therefore, these are clustered according to the role they can play in the planning process, such as finding the moment in history when the region was regenerative, what a regenerative region consists of, how this regenerative region can be achieved, and who can make this happen (see Figure 8).

When urban regions are discussed, comparative analyses are also widespread and each one has its own purpose. A general definition of a spatial development framework is: “a strategic planning method used to analyze and describe the regional structure and interdependencies between settlements in a country or region” [86]. Some of them specialize in floods [87], others in bike-sharing [88], or ecosystem services [89], and there are many others. Generally, each spatial planning framework serves its own very specific topic. To make the case for a regional planning framework that can be combined with regenerative thinking, the underlying aspects that can create such a regenerative region have to be discovered. These are general themes that are most important in shaping such urban regions. In this article, we rely on practical expertise derived from the regions involved. Personal judgements gave us insight into which key aspects of planning were deemed most relevant. The themes that we found are all crucial for regional regeneration, the capability to recreate and replenish natural resources in the area. The landscape, its elevation, water, and ecological systems play major roles in making that possible. Secondly, land ownership and political decisions are crucial. This practice-based knowledge is then related to the complex and comprehensive ‘framework of frameworks’.

6. Conclusions

The integration of theoretical regenerative frameworks and practical understanding of regional regeneration potentials has led to the integrated regenerative framework for regional planning (Figure 11). This framework highlights the content as well as practical use of it. It comprises three stages of thought: understanding the region in its original state, creating a shared view of the future, and determining the required transformation and how and with whom to get there. When compared to current regional planning approaches, these mostly start with analyzing the current state of the area and are connected to current objectives aiming to formulate a plan for future development, a future which is often no more than 20–40 years from the present. Two major problems arise from this. Firstly, the idea of analyzing the current state to base future decisions has the risk of the shifting baseline syndrome [90,91], which makes one think that the current situation is similar to the past. Secondly, working with future timespans that are within one generation implies an unconscious risk of prioritizing the interests of your own generation. Both problems distract from understanding longer periods and miss out on opportunities for regeneration that are linked to the natural history of the place and are meant to service generations that will live long after us [73].

The development of a regenerative region is by nature a complex matter. The future is fluid, and a multitude of interrelated complexities must be solved at the same time. Moreover, it is a future that is full of feedback mechanisms, uncertainties, and unprecedented developments ahead of us. In such a complex environment, a solid ground is needed to decide what is working toward future survival and regeneration, and what is not. Therefore, the regenerative framework for regional planning also describes how future complexities can be navigated (see Figure 11). It starts with returning to a sustainable equilibrium in the past, when settlers first reached the region, then moves to thinking with people locally about the desired future, and then determines how and with whom the gap between the current region and a regenerative one can be closed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.R.; methodology, R.R.; software, R.J.; validation, R.R. and R.J.; formal analysis, R.R.; investigation, R.J.; resources, R.R.; data curation, R.J.; writing—original draft preparation, R.R.; writing—review and editing, R.R.; visualization, R.J.; supervision, R.R.; project administration, R.R.; funding acquisition, R.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the invaluable contributions to this study from the key persons in the nine selected regions, Karen Hinojosa (Monterrey), Maria Elena de la Torre (Gualdalajara), Diana Garcia and Rodrigo Pantoja (Queretaro), Peter Bishop (London), Steffen Nijhuis (Randstad), Marco Casagrande (Kharkiv), Chrisna du Plessis (Pretoria), Rod Simpson (Port Moresby), and Alejandro Echeverri (Medellin), for providing the data, maps, and feedback before, during, and after the mapping of the regions and the discussion in the workshop during the International Symposium on Regenerative Regions in Monterrey, Mexico, on 4–6 March 2024.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Henig, D.; Knight, D.M. Polycrisis: Prompts for an emerging worldview. Anthropol. Today 2023, 39, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyer, D.; Bennett, J.S.; Reddish, J.; Holder, S.; Howard, R.; Benam, M.; Levine, J.; Ludlow, F.; Feinman, G.; Turchin, P. Navigating polycrisis: Long-run socio-cultural factors shape response to changing climate. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2023, 378, 20220402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, M.; Homer-Dixon, T.; Janzwood, S.; Rockstöm, J.; Renn, O.; Donges, J.F. Global Polycrisis: The causal mechanisms of crisis entanglement. Glob. Sustain. 2024, 7, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crutzen, P.J.; Stoermer, E.F. The Anthropocene. Glob. Chang. Newsl. 2000, 41, 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, L.E. What is the Anthropocene. Eos 2015, 96, 6–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almond, R.E.; Grooten, M.; Peterson, T. Living Planet Report 2020-Bending the Curve of Biodiversity Loss; World Wildlife Fund: Gland, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chew, S.C. World Ecological Degradation: Accumulation, Urbanization, and Deforestation, 3000 BC-AD 2000; Rowman Altamira: Lanham, MD, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. In Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; p. 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, A.; McBratney, A.; Adams, M.; Field, D.; Hill, R.; Crawford, J.; Minasny, B.; Lal, R.; Abbott, L.; O’Donnell, A.; et al. Soil security: Solving the global soil crisis. Glob. Policy 2013, 4, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zika, M.; Erb, K.H. The global loss of net primary production resulting from human-induced soil degradation in drylands. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 69, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenmark, M.; Wang-Erlandsson, L.; Rockström, J. Understanding of water resilience in the Anthropocene. J. Hydrol. X 2019, 2, 100009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J.; Falkenmark, M.; Allan, T.; Folke, C.; Gordon, L.; Jägerskog, A.; Kummu, M.; Lannerstad, M.; Meybeck, M.; Molden, D.; et al. The unfolding water drama in the Anthropocene: Towards a resilience-based perspective on water for global sustainability. Ecohydrology 2014, 7, 1249–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampert, A. Over-exploitation of natural resources is followed by inevitable declines in economic growth and discount rate. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, I.; Gupta, R.K. Natural resources depletion and economic growth in present era. SOCH-Mastnath J. Sci. Technol. 2015, 10, 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Chase-Dunn, C.; Lawrence, K.S. The next three futures, part one: Looming crises of global inequality, ecological degradation, and a failed system of global governance. Glob. Soc. 2011, 25, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sernau, S. Worlds Apart: Social Inequalities in a Global Economy; Pine Forge Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Weiß, A. Global Social Inequalities. In Global Handbook of Inequality; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan, S.; Aydin, N.Y.; Comes, T. TIMEWISE: Temporal Dynamics for Urban Resilience theoretical insights and empirical reflections from Amsterdam and Mumbai. NPJ Urban Sustain. 2024, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rega, C. Ecological Rationality in Spatial Planning: Concepts and Tools for Sustainable Land-Use Decisions (Cities and Nature); Springer: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, S.; Zoppi, C. Sustainable Spatial Planning Based on Ecosystem Services, Green Infrastructure and Nature-Based Solutions. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEA. Exiting the Anthropocene? Exploring Fundamental Change in Our Relationship with Nature. Briefing. 2023. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/exiting-the-anthropocene/ (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Bekker, A.; Po, C.; Chang, F.-J. Radicle Civics—Building Proofs of Possibilities for a Civic Economy and Society. Dark Matter, 14 August 2023. Available online: https://provocations.darkmatterlabs.org/radicle-civics-building-proofs-of-possibilities-for-a-civic-economy-and-society-ee28baeeec70 (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- Wahl, D.C. Designing Regenerative Cultures; Triarchy Press: Axminster, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, G. Exiting the Anthropocene and Entering the Symbiocene. 2015. Available online: https://glennaalbrecht.wordpress.com/2015/12/17/exiting-the-anthropocene-and-entering-the-symbiocene/ (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Næss, A. The shallow and the deep, long-range ecology movement: A summary. Inquiry 1973, 16, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Næss, A. Self-realization: An ecological approach to being in the world. In Deep Ecology for the Twenty-First Century; Sessions, G., Ed.; Shambhala: London, UK, 1995; pp. 225–239. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, R.K. Sustainability: Principles and practices. In Sustainable Environmental Economics and Management: Principles and Practice; Turner, R.K., Ed.; Belhaven Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 1993; pp. 3–36. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, D. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- EESC. Towards an EU Charter of the Fundamental Rights of Nature—Study. 2019. Available online: https://www.eesc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/files/qe-03-20-586-en-n.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Cole, R.J.; Oliver, A.; Robinson, J. Regenerative design, socio-ecological systems and co-evolution. Build. Res. Inf. 2013, 41, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, T. The Self Delusion: The Surprising Science of How We Are Connected and Why That Matters; Weidenfeld & Nicolson Ltd.: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- McLoughlin, B. Urban and Regional Planning: A Systems Approach; Faber & Faber: London, UK, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Allmendinger, P. Planning Theory; Palgrave: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Allmendinger, P. Neoliberal Spatial Governance; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Banfield, E.C. Ends and means in planning. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 1959, xi, 361–368. [Google Scholar]

- De Roo, G.; Rauws, W.; Zuidema, C. Rationalities for adaptive planning to address uncertainties. In Handbook on Planning and Complexity; De Roo, G., Yamu, C., Zuidema, C., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 110–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblom, C.E. The Science of “Muddling Through”. Public Adm. Rev. 1959, 19, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, J. A Conceptual Model for the Analysis of Planning Behavior. Adm. Sci. Q. 1967, 12, 225–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggema, R.E. Swarm Planning: The Development of a Spatial Planning Methodology to Deal with Climate Adaptation. Ph.D. Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davy, B. Plan ‘it´ without a condom! Plan. Theory 2008, 7, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schurig, S.; Turan, K. The concept of a ‘regenerative city’: How to turn cities into regenerative systems. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 2022, 15, 161–175. [Google Scholar]

- Mang, P.; Reed, B. Regenerative Development and Design. In Encyclopedia of Sustainability Science and Technology; Meyers, R.A., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 8855–8879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckton, S.J.; Fazey, I.; Sharpe, B.; Om, E.S.; Doherty, B.; Ball, P.; Denby, K.; Bryant, M.; Lait, R.; Bridle, S.; et al. The Regenerative Lens: A conceptual framework for regenerative social-ecological systems. One Earth 2023, 6, 824–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camrass, K. Regenerative Futures: Eight Principles for Thinking and Practice. J. Futures Stud. 2023, 28, 88–99. Available online: https://jfsdigital.org/articles-and-essays/2023-2/vol-28-no-1-september-2023/regenerative-futures-eight-principles-for-thinking-and-practice/ (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- Stevens, L.; Kopnina, H.; Mulder, K.; De Vries, M. Biomimicry design thinking education: A base-line exercise in preconceptions of biological analogies. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2021, 31, 797–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mang, P.; Haggard, B. Regenerative Development and Design: A Framework for Evolving Sustainability; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez Jaber, I. Regenerative Design: The Movement Aiming to Return Us to Our Roots. TEC Science, 30 June 2023. Available online: https://tecscience.tec.mx/en/human-social/regenerative-design/ (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- Dudley, N.; Baker, C.; Chatterton, P.; Ferwerda, W.H.; Gutierrez, V.; Madgwick, J. The 4 Returns Framework for Landscape Restoration; Commonland, Wetlands International Landscape Finance Lab and IUCN Commission on Ecosystem Management: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Gland, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hes, D.; Du Plessis, C. Designing for Hope. Pathways to Regenerative Sustainability; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hawken, P. Regeneration. Ending the Climate Crisis in One Generation; Penguin Books: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lyle, J.T. Regenerative Design for Sustainable Development; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, P. The evolution, definition and purpose of urban regeneration. In Urban Regeneration: A Handbook; Roberts, P., Sykes, H., Eds.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2000; pp. 9–36. [Google Scholar]

- Girardet, H. Creating Regenerative Cities; Routlegde: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mang, N.S. Toward a Regenerative Psychology of Urban Planning; Saybrook Graduate School and Research Center: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009; Available online: https://powersofplace.com/pdfs/Toward_a_Regenerative_Psychology_of_Urban_Planning.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Jenkin, S.; Pedersen Zari, M. Rethinking Our Built Environments: Towards a Sustainable Future; Ministry for the Environment, Manatu Mo Te Taiao: Wellington, New Zealand, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gabel, M. Regenerative Development: Going Beyond Sustainability. Kosmos, Fall/Winter 2015. Available online: https://www.kosmosjournal.org/article/regenerative-development-going-beyond-sustainability/ (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Wahl, D.C. What Are Regenerative Cultures? Resilience, 22 March 2021. Available online: https://www.resilience.org/stories/2021-03-22/what-are-regenerative-cultures/ (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Reed, B.; Holliday, M. A Regenerative Approach to Tourism in Canada; Destination Canada: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Living Environments and Regeneration. Lenses Overview Guide. How to Create Living Environments in Natural, Social, and Economic Systems. 2018. Available online: https://ibe.colostate.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/LENSES-Overview-Guide_Facing_6.9.18.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Plaut, J.M.; Dunbar, B.; Wackerman, A.; Hodgin, S. Regenerative design: The LENSES Framework for buildings and communities. Build. Res. Inf. 2012, 40, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, P.; Marchant, D.; Mitchell, J.; Plume, J.; Seo, S.; Roggema, R. Performance Assessment of Urban Precinct Design: A Scoping Study; CRC for Low Carbon Living: Sydney, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Awadh, O. Sustainability and green building rating systems: LEED, BREEAM, GSAS and Estidama critical analysis. J. Build. Eng. 2017, 11, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowri, K. Green building rating systems: An overview. ASHRAE J. 2004, 46, 56. [Google Scholar]

- International Living Future Institute. Book review Living Building Challenge. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 6, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katila, P.; Colfer, C.J.P.; De Jong, W.; Galloway, G.; Pacheco, P.; Winkel, G. (Eds.) Sustainable Development Goals; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Mang, P.; Reed, B. Designing from place: A regenerative framework and methodology. Build. Res. Inf. 2012, 40, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, C. Towards a regenerative paradigm for the built environment. Build. Res. Inf. 2012, 40, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commoner, B. The Closing Circle: Nature, Man, and Technology; Alfred A. Knopf: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Nightingale, A.J. Commoning for inclusion? commons, exclusion, property and socio-natural becomings. Int. J. Commons 2019, 13, 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, C.A. The Role of Indigenous Paradigms and Traditional Knowledge Systems in Modern Humanity’s Sustainability Quest–Future Foundations from Past Knowledge’s. In Designing Sustainable Cities; Roggema, R., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, C.; Twill, J. Using Indigenous knowledge in climate resistance strategies for future urban environments. In Design for Regenerative Cities and Landscapes: Rebalancing Human Impact and Natural Environment; Roggema, R., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Krznaric, R. The Good Ancestor; WH Allen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Roggema, R. The Eco-Cathedric City: Rethinking the Human–Nature Relation in Urbanism. Land 2023, 12, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Biggs, R.; Norström, A.V.; Reyers, B.; Rockström, J. Social-ecological resilience and biosphere-based sustainability science. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J.; Sukhdev, P. How Food Connects All the SDGs. Available online: http://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/research-news/2016-06-14-how-food-connects-all-the-sdgs.html (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Roggema, R. Shifting paradigms. In The Design Charrette: Ways to Envision Sustainable Futures; Roggema, R., Ed.; Springer Science+Business Media: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 61–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casagrande, M. Third Generation City; The International Society of Biourbanism: Artena, Italy, 2013; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Partelow, S. What is a framework? Understanding their purpose, value, development and use. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2023, 13, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M.; Villamayor-Tomas, S.; Epstein, G.; Evans, L.; Ban, N.C.; Fleischman, F.; Nenadovic, M.; Garcia-Lopez, G. Synthesizing theories of natural resource management and governance. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2016, 39, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlager, E. A Comparison of frameworks, theories, and models of policy processes. In Theories of the Policy Process, 1st ed.; Sabatier, P.A., Ed.; Routledge: Milton Park, UK, 2007; pp. 293–319. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming, G.S. Theoretical Frameworks for the analysis of social-ecological systems. In Social-Ecological Systems in Transition; Sakai, S., Umetsu, C., Eds.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, C.R.; Hinkel, J.; Bots, P.W.G.; Pahl-Wostl, C. Comparison of Frameworks for analyzing social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinnis, M.D.; Ostrom, E. Social-Ecological system framework: Initial changes and continuing challenges. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulver, S.; Ulibarri, N.; Sobocinski, K.L.; Alexander, S.M.; Johnson, M.L.; Mccord, P.F. Frontiers in socio-environmental research: Components, connections, scale, and context. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerboom, L.; Gibert, M.; Spaliviero, M.; Spaliviero, G. The Spatial Development Framework for Implementation of National Urban Policy. Rwanda J. Ser. D 2016, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, D.A.; Vercruysse, K.; Wright, N. A spatial framework to explore needs and opportunities for interoperable urban flood management. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 2020, 378, 20190205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loidl, M.; Witzmann-Müller, U.; Zagel, B. A spatial framework for Planning station-based bike sharing systems. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2019, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medcalf, K.; Small, N.; Finch, C.; Williams, J.; Blair, T.; Haines-Young, R.; Potschin, M.; Parker, J. Further Development of a Spatial Framework for Mapping Ecosystem Services; JNCC: Peterborough, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pauly, D. Anecdotes and the shifting baseline syndrome of fisheries. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1995, 10, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Gaston, K.J. Shifting baseline syndrome: Causes, consequences, and implications. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2018, 16, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).