Abstract

The loss of functions in Spanish rural areas has triggered territorial inequalities and injustices in a highly complex geographical environment. After the COVID-19 pandemic and in a context of overpopulation in large cities, the rural area emerged as a space of opportunity for more sustainable territorial rebalancing. Despite the evident tendency towards their population emptying, they are places endowed with their own qualities and specific values, currently in danger, especially in border areas between the regions, which are far from centralised nuclei and generate conflicts due to the transfer of powers to them from the State. Among these values is cultural heritage, the safeguarding and enrichment of which depends on the balance between the landscape and the society that hosts it. This work focuses on access to archaeological sites—an important form of heritage prior to the establishment of actual regional divisions, in the depopulated frontier between Cantabria and Castile and Leon—whose potential is presented by their intrinsic relationship with the territory and their ability to identify historical landscapes, advocating for future sustainability on a territorial scale. With all of the above, a cultural landscape delimitation is proposed between both regions that share common characteristics and problems, promoting synergies and territorial readings by analysing the territorial assets of these interior areas so that their potential is not diminished.

1. Introduction

Since the end of the 20th century, one of the main problems in Europe from a multi-scale territorial perspective has been depopulation. This phenomenon can be defined as a decrease in the number of inhabitants in the territory or in urban and rural areas compared to a previous period [1]. These imbalances prevent social, territorial and productive equity, leading, among other things, to a loss and degradation of local identity values and of the cultural landscape.

To this must be added the processes of over-concentration of large cities, deteriorating and unbalancing the territory and making it unsustainable to live in inner urban areas. Currently, more than half of the population live in cities—a percentage that is expected to increase to 70% by 2050 [2]. The evolution of urbanisation is not a new problem as it has marked different historical periods, with its maximum effect occurring during the industrial revolutions, when the population moved in search of job opportunities. With more citizens, more urban land area is expected, putting increasing pressure on natural land reserves. Nevertheless, the digital revolution in which we live, where smart work is widespread, will allow us in the coming years to replace traditional working life with work initiatives based on offshoring [3].

In this context, sparsely populated territories exemplify the contradictions of development, because despite having economic indicators that could be considered acceptable in terms of income, wealth and employment levels, expectations are negative, and they are often initially unattractive places to live [1]. Therefore, population density is a variable to which other important socio-economic factors can be added. This unattractiveness occurs because of the difficult access to some of these localities, resulting in population loss and socio-economic issues within a vulnerable area that needs to be adequately managed in order to have a regional balance. However, if one looks at their potential, these territories—which in Spain occupy 84% of the total surface area [4]—can become places of opportunity for society to settle in them, both as habitats and productive spaces in the new digital era. Moreover, in those zones, the role of heritage is very important as the resources that are found, such as the cultural assets, can ensure that the territory is sustainable and resilient through the reinforcement of local identity and the increase in tourist appeal, among other aspects. This last idea could also mean a more sustainable tourism network as it would be more distributed throughout the territory and not only centred in over-touristed centres.

The rural heritage, together with the territory understood in terms of heritage, allows this identity to remain in the face of external pressures. This would maintain the elements inherited by the current generation over time in a balanced and egalitarian way, and these heritage assets could contribute to the social and physical sustainability of the environment in which they are situated [5]. Consequently, heritage should be considered as a resource for development, understanding development beyond the economic aspect of the increase in tourist appeal, reaching the integration of other dimensions such as the creative capacity or autonomy to make decisions [6], as in the case of the depopulated rural areas mentioned above. However, the qualities and values of rural cultural landscapes are in danger of disappearing in territories in demographic depression, which is why research is working towards recovery to advocate for their future resilience and balance through effective protection [7].

The European Union, and the countries themselves, have specific programming that favours strategies and initiatives to counteract the depopulation of inland areas in an intelligent, sustainable and inclusive way. Their proposal is to establish macro-territories of small networks of cities and polarise some centres linked to each other, using a hierarchical structure of settlements that leads to processes of deterritorialization over time, emptying some inland areas and concentrating large cities [1]. For these solutions to work in the long term, it is first necessary to optimise the connecting infrastructures, as an initial condition for all other subsequent actions to work. Through state funding, the maintenance of existing networks and the efficient integration of new parts deemed necessary must be ensured. Secondly, the specificities of inland areas should be valued through sustainable development strategies, such as valuing their natural and cultural capital, highlighting local craftsmanship or recognising their energy independence thanks to renewable energy sources [3]. Moreover, some of the initiatives to counteract the depopulation of certain villages altogether, involving the reuse of existing natural and historical resources, have become a strategy for sustainable development. In contrast, other less systematic proposals have only involved solutions that have worked in the short term.

All this must go hand in hand with the conservation of these natural and cultural resources, specific to each place and undoubtedly linked to the territory. In general, linking cultural heritage to the territory has meant the discovery of a resource that can satisfy the needs of society, as it incorporates human and social production: memory and identity and their interpretation and the daily use of the people who live there. Its conception as a territorial resource is essential to guarantee its sustainability, which, for example, is applied and defended by UNESCO [8]. It is important that the proposal is sustainable and ensures quality of life, with spaces that are in balance with the landscape and the society that inhabits it, returning to a quality of life based on sustainability and democracy, seeking communitarian historicity and identity in the essential factors.

With all this, it is necessary to return to local elements, which, together with the concept of a bioregion, propose a system of networks of municipalities. This broad network would be made up of small cities connected through nodes that enhance existing values: natural, cultural, social, economic, territorial, etc. [9]. The new system could create synergies among those towns that, on their own, do not have enough capability to face rural challenges but together are stronger.

In Spain, depopulation is not occurring in an equal or balanced manner at the territorial level between Autonomous Communities or inside them. Moreover, the transfer of powers to the Autonomous Communities in the 1980s means that the main problems of disconnection and depopulation occur in the border areas—that are mainly rural—of the regions, far from the main hubs. Moreover, the frontier between regions is especially delicate, as the legislations on both sides of the line are different in terms of territorial planning and cultural heritage protection, among other aspects. This means that a territory that can be identified as unitarian—because the border line does not exist physically—is managed in different ways, which becomes a real problem when talking about the management of that area and for the daily living of its habitants.

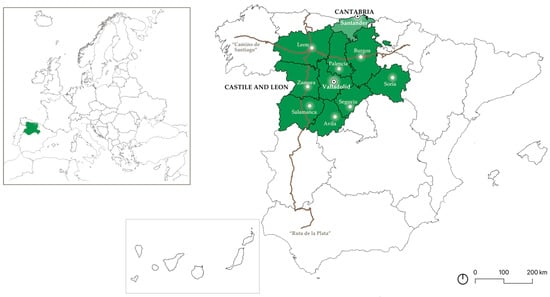

The demographic changes in these fragile areas can be recognised through the permanent aspects of the territory, which can also help in the characterisation of its heritage and landscape, whose borders do not necessarily coincide with the current boundaries. This is the case in the Autonomous Communities of Cantabria and Castile and Leon, which, not so long ago, were united as Old Castile. These Autonomous Communities have been chosen for the current study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Map of the current Autonomous Communities’ and the provinces’ limits where the study is going to centre in darker green the ones of Castile and Leon and in lighter green the uniprovince of Cantabria, at a Spanish scale and in the European context. The main historical routes that cross the study area are also shown in brown, as they will be relevant later in the text. Source: own elaboration based on the National Geographical Institute’s cartography and the Geoportal of the Spatial Data Infrastructure of Spain.

In order to frame some of the main features of these regions, Table 1 provides some basic information on both Castile and Leon and Cantabria and displays the existing large differences between the regions. However, this contrast can strengthen the vulnerabilities of each region if they cooperate. In general, this study is carried out for a total of almost 3 million inhabitants that are unequally distributed throughout the total almost 100,000 km2 surface area.

Table 1.

Table of the basic features that define the Autonomous Communities of Castile and Leon and Cantabria. Source: own elaboration based on the National Geographical Institute’s data.

Some of the permanent aspects in rural territories are materialised through archaeological sites, as they can be recognised as an integral and inseparable part of the human and natural construct. This is because there is a clear reference to a particular culture and time—before the current frontiers existed—as they are vestiges of human activity and identity elements of a place, which make up both cultural and territorial identity [10]. They can present the historical models of certain areas and provide necessary information to understand how the territory was organised in the past and learn from it. Therefore, the current study centres on the archaeological sites, which are the concretion of the archaeological vestiges’ safeguard in a category that the Spanish heritage protection law system adopts. This is the initial stage of recognition of the historical remnants in the territory, having an intrinsic and undeniable relationship with the landscape. Furthermore, this protection figure can assist in a comparative study between Autonomous Communities, since all the regional heritage laws include this protection category of the Spanish Historical Heritage, as it comes from the national Law 16/1985 of the 25th of June [11]. After the national Law, each Autonomous Community has developed its own heritage law, adding different safeguarding figures, leading to an overly heterogeneous heritage protection legal system in Spain.

Archaeological assets in the territory, in general, are dispersed forms of heritage found mainly in rural areas—as they have not has as much intervention as the urban sectors—in which, until now, only specific, decontextualised actions have been carried out. However, if municipalities—even from different Autonomous Communities—were to be brought together through archaeological heritage, it would allow for a cross- and territorial analysis of the settlement system, which configures the network that makes up the territory, favouring an extension of and articulation with adjoining regions. At this point, the cultural landscape figure appears as the most suitable category to fulfil the need of understanding the identified area. It is the perfect tool to recognise the territory together with its heritage value, characterising the rural depopulated area and allowing for a new process of territorialization [12].

This work therefore aims to propose an area of opportunity and develop an approach to the landscape characterisation of this territory with demographic loss in the rural border zone. We take as case studies the bordering territories between Cantabria—which is uniprovincial—and Castile and Leon—the provinces of Leon, Burgos and Palencia—which have great archaeological wealth and consequently a high potential for reactivation. This would facilitate the possibility of promoting a cultural offer involving several municipalities, thereby establishing a stronger economy and a more sustainable touristic model for the whole territory, far from the main over-touristed nodes. Sustainable proposals for heritage management can help to strengthen the socio-economic fabric of the most vulnerable territories through the generation of new relations, which can be shown through the characterization of the cultural landscape they belong to. This includes the structural elements of the resulting system of municipalities, which would strengthen social cohesion in resilient communities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Objectives

This research aims to identify cultural landscapes in rural municipalities at risk of depopulation in the frontier of Cantabria and Castile and Leon by means of their archaeological heritage remains, in order to define areas of opportunity for the reactivation of this cross-border territory, making it more resilient and sustainable.

Its specific objectives include the following:

- To contextualise the territories and explore the archaeological dimension of these Autonomous Communities.

- To analyse the framework of regional heritage legislation.

- To define the accessibility of archaeological heritage in both regions.

- To study and graphically represent the archaeological areas and their accessibility and to find the areas of opportunity in which the heritage keys in the territory that have remained unchanged can be found.

- To propose a cultural landscape in a cross-border zone between the two regions.

- To expose synergies and systematic elements that could characterise the cultural landscape for a greater potential of the heritage.

2.2. Methodology

After a rigorous search and bibliographic, documentary and cartographic review, reading and analysis allowed us to frame the context of study of this research. We identified its endogenous strengths and weaknesses, as well as its exogenous opportunities and threats, typical of a SWOT matrix, and this information has been taken into account throughout the whole article.

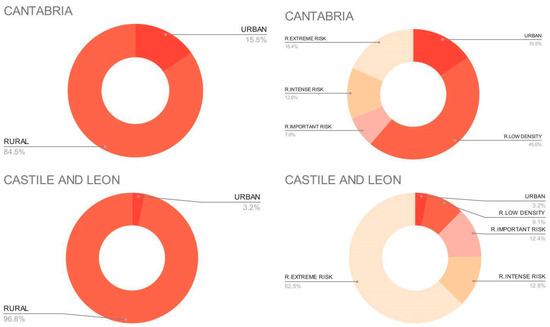

In order to define rural areas and identify which of them are at risk of depopulation, a method was proposed based on statistical data on population density and populations from the National Statistics Institute of Spain [13] and in accordance with the criteria proposed by UN-Habitat [14] and the Strategy to Combat Depopulation in Navarre [15]. Thanks to this method, the areas at risk of depopulation—<25 inhabitants/km2—of the study territory between Castile and Leon and Cantabria were identified. In Spain, the Autonomous Community with the greatest depopulation problem is Castile and Leon, as it has the largest area at extreme risk of depopulation: 62.5% (Figure 2). For this reason, we decided to work in the northern part of this region, in contact with Cantabria, which, despite 91% of its surface area being considered rural, has only 16.4% at extreme risk (Figure 2)—the area on its southern border with the Community of Castile and Leon.

Figure 2.

Diagrams of the percentage of rural municipalities—and the percentage of them that are at risk of depopulation—and urban municipalities in Cantabria and Castile and Leon. Modified from: EL Patrimonio Cultural Como Recurso de Desarrollo Sostenible de los Territorios en Despoblación: La Accesibilidad al Legado Rural Español [11].

In addition to the search of the areas at risk of depopulation, an economic study has also been carried out using the average household income by municipality, in order to identify the financial context of the regions.

After setting out the framework of depopulation in Cantabria and Castile and Leon, the hierarchy of cities was defined. The criteria proposed for ranking cities are important since, in order to study accessibility, it is essential to have a starting node, and this node has its own qualities, making it necessary to distinguish between cases in which accessibility is calculated from a large city, a medium-sized city or a rural area [13].

On the other hand, the aim is to improve the potential of these regions through heritage, and it is necessary to understand the legislation on cultural heritage in general—and archaeological heritage in particular. This ranges from the Spanish Historical Heritage Law, Law 16/1985 [11], and Laws 11/1998 of 13 October on Cultural Heritage in Cantabria [16] to Law 12/2002 of 11 July—derogated—[17] and Law 7/2024 of 20 June [18] on Cultural Heritage in Castile and León. It is important to point out that the transfer of powers in the field of culture from the State to the Autonomous Communities has meant the unequal protection of assets in each of the regions. Therefore, for the current study, the declared cultural interest goods, archaeological sites, were chosen to be those elected by the regions as culturally relevant. Nevertheless, this choice leaves aside other important archaeological vestiges that have not been protected and other cultural assets that would need to be included in future studies.

This research seeks to measure the levels of access of citizens to these assets as an indicator that helps us to understand the existing territorial balance: the greater the access, the greater the potential of the heritage resource for sustainable local development [8]. The accessibility is linked to the possibility to reach unique [19] archaeological goods. The analysis of the accessibility to cultural heritage has already been studied [8], as has accessibility to geoheritage [19] For the analysis of accessibility to archaeological sites in both regions, 20% of the most populated municipalities in both regions have been selected, since the main services are located and established in these places to reduce costs [20] and, therefore, this is where a large part of the population is located. From these nodes, the origin of the isochrones’ marking accessibility is established, defined by the time needed to cover areas from one point. The times for the different isochrones are based on existing sources [8], and for each of them, different degrees of accessibility are established depending on the city of origin [13].

With all the previous layers, a summarised cartography is proposed, at the base of which are the road infrastructures on which the intermediate zones of opportunity are defined. In this cartography, the cross-border area of opportunity is finally drawn by the features shared by both communities.

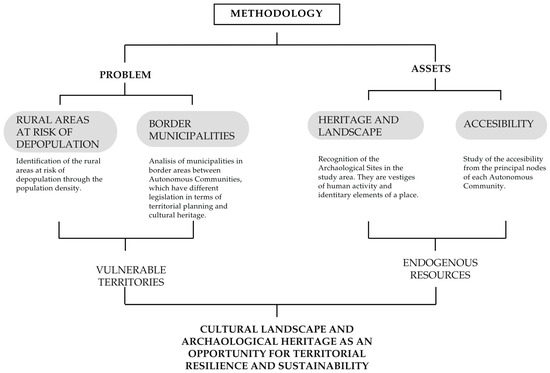

Once the opportunity zone is selected, its cultural landscape is exposed during the analysis of the territory’s main features. It is important to work on a large scale to show the cultural network of the site, which would protect its cultural footprint in a more resilient way. The previous methodology is resumed in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Diagram of the methodology followed to achieve the goal of the paper. Source: own elaboration.

All the previous information has been managed and represented through the production of our own cartographies in Geographic Information Systems applications, such as QGIS, based on Geographical Information System (GIS) technology. Through this tool, complex realities such as depopulation or the distribution of heritage can be exposed on a large scale, as part of the presentation of the current situation, but it has also served to identify areas of opportunity.

3. Results

3.1. Territorial Context of Castile and Leon and Cantabria

Spain follows the same tendency as other developed economies, which all tend towards urbanisation: 25% of the Spanish population lives in large cities, with more than one million inhabitants, but more than 90% of Spanish municipalities have less than 5000 inhabitants [13].

This situation comes from the demographic changes in Spain that have happened since 1950, with industrialization. In 1990, the municipalities in general did not have high population densities, so there was a kind of social and demographic balance, making the situation considerably more sustainable than the one we have today. Throughout the second half of the 20th century, an absolute demographic decline occurred. During the period from 1950 to 1975, in the midst of a dictatorship, economic growth was very intense, entailing large population transfers from rural regions to leading regions such as the cities [1]. In the second period, from 1990 onwards, the urban percentage continued to increase but much more slowly, which coincided with the establishment of the new economic model and the development of the welfare state in Spain. Therefore, the increase in the population of urban areas compared to rural areas is due to the natural population growth differential between rural and urban zones [21]. In the first decade of the 21st century, the great growth of the Spanish economy brought about substantial changes. The rate of depopulation slowed down and showed heterogeneous behaviour, some of which was justified by the massive influx of immigrants to Spain during the years of the economic boom. However, the crisis that began in 2008 and continued intensely until 2011 reactivated the process of negative natural growth and consolidated a trend of rural abandonment, which, together with the reduced arrival of immigrants, extended the problem of depopulation to almost the entire country [20].

However, this loss did not occur equally in all territories as it occurred with Castille and Leon and Cantabria. In the first region, for example, the population density has decreased more than the Spanish median from 1960 to today, meaning that most of the municipalities in Castile and Leon have below eight inhabitants/km2. Moreover, almost 90% of the 2248 municipalities in 2020 had less than 1000 inhabitants. This situation leads to the abandonment and ageing of the people. Emigration, particularly female emigration, has played a crucial role in this process, as it has led to a reduction in births and the masculinisation of the territory. This phenomenon is the cause of the population shift from rural to urban areas in Castile and Leon—a problem that has gradually altered the majority of the region, concentrating the population in specific places such as provincial capitals, industrial cities and county capitals. However, throughout history, individuals have also left the region and moved to other Spanish Autonomous Communities and other nations, particularly to the American continent [22].

In the case of Cantabria, throughout the 20th century, the rural community has experienced an intense process of emigration. The rural exodus began early in certain regions, before the middle of the century, but reached its peak from the 1960s onwards and spread over the following decades. Since the last decade of the former century, the population of rural municipalities has continued to decline at a slower pace, while the total population of the region continued to increase modestly. The most alarming point is that in the early years of the 21st century, the decline of the rural population continued in a general scenario of population stagnation. The study of demographic evolution varies not only in time but also in space, as the coastal regions do not experience the same process as the municipalities of the mountains, which suffered a considerable reduction in their population [23].

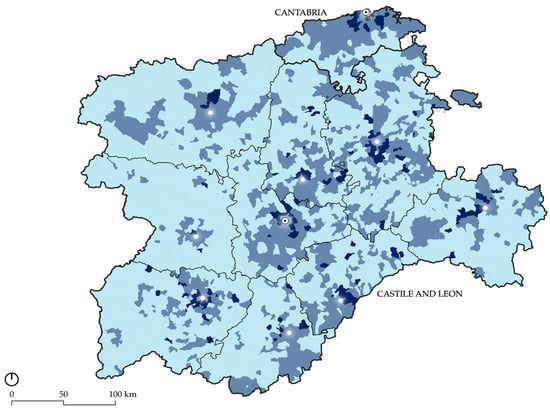

As shown on the map (Figure 4), the reduction of the population between the years 2011 and 2021 happens principally in the inland of the study area, far from the main cities or the coast of Cantabria. Nowadays, the main problem lies in the Community of Castile and Leon, where almost 88% of the municipalities are at general population risk (Figure 2). However, we should not overlook the problem that may arise in other regions such as Cantabria, which, despite not having data as alarming as Castile and Leon, has suffered from the neglect of the interior of the community in favour of the coastal areas.

Figure 4.

Map of the variation of the population between the years 2011 and 2021: in light blue a variation of more than a 10% reduction of the population; in medium blue, the variation of between a 10% of reduction or augmentation of the population; and in dark blue, the variation on the augmentation of more than a 10% of the population. The points are the capitals of the provinces, and the ones with the black dot the capitals of the Autonomous Communities. Source: own elaboration based on the methodology developed with the data of the Spanish National Institute of Statistics and based on the National Geographical Institute’s cartography.

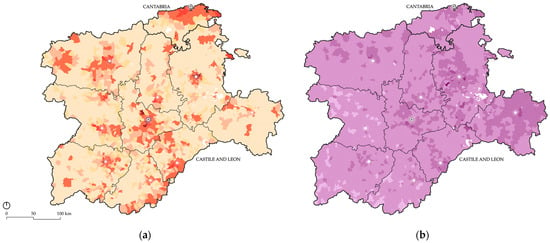

In the planimetry of the population density of both communities by municipality (Figure 5a), it can be seen that the problem of depopulation is most significant in the border areas, far from the centralised main cities of Castile and Leon or the Cantabrian coast.

Figure 5.

Planimetry showing population density by municipality (a), related to Table 2 and the average household income by municipality (b), related to Table 3. The points are the capitals of the provinces, and the ones with the black dot the capitals of the Autonomous Communities. Source: own elaboration based on the methodology developed with the data of the Spanish National Institute of Statistics and the Geoportal of the Spatial Data Infrastructure of Spain and based on the National Geographical Institute’s cartography.

Table 2.

Table of related to the Figure 5a, where the division of the municipalities is explained. Source: own elaboration.

Table 3.

Table related to Figure 5b, where the average household income of the municipalities is explained. Source: own elaboration.

Nevertheless, population loss is a variable to which other criteria could be added, such as the average household income, which can be seen in Figure 5b and related to Table 3. Taking a look at the map, it can be seen that it is quite homogeneous throughout the study area—the average household income is between EUR 20 and 30 thousand. In the surroundings of the main cities, this income increases, where in general terms, the population is larger, especially in the northeast of the area. On the other side, in the southwestern areas, far from the provincial capitals, the household income decreases. The border areas between both Autonomous Countries have mainly between EUR 20 and 30 thousand of income, but some municipalities happen to have increased earnings up to EUR 40,000. This means that the study border area is not especially wealthy (in the middle–lower part of the table), but this is the case for the whole regions of Castile and Leon and Cantabria in general.

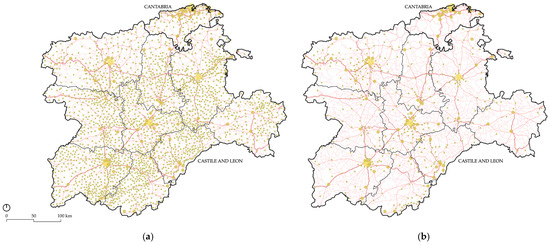

Taking into account the hierarchy of cities outlined above, all categorised cities are presented, divided into large cities, medium-sized cities or rural municipalities (Figure 6a). In Cantabria, it can be observed that the larger cities are concentrated on the coast, while the smaller municipalities are in the interior of the region. On the other hand, in Castile and Leon, a system of centralised main cities surrounded by numerous small municipalities is observed, and these ‘fade away’ as one moves away from the large nodes. For this research, only the 20% most populated in each region were used (Figure 6b). In the case of Cantabria, these are large and medium-sized cities, and in the case of Castile and Leon, they are large, medium-sized and small. It is from these 20% most populated cities that accessibility is calculated using the data set out in the methodology, as shown below (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Classification of large, medium and small cities in Cantabria and Castile and Leon over the road network layer in red, according to the new criterion. On the right, all cities (a), and on the left, the 20% most populated cities (b), related to Table 4. Source: own elaboration based on the methodology developed with the data of the Spanish National Institute of Statistics and based on the National Geographical Institute’s cartography.

Table 4.

Table of related to the Figure 6, where the classification of the cities is explained. Source: own elaboration.

Figure 7.

Map of the isochrones from the largest cities (Figure 6b) in both Castile and Leon and Cantabria over the road network layer in red, related to Table 5. Source: own elaboration based on the methodology developed with the data of the Spanish National Institute of Statistics and based on the National Geographical Institute’s cartography.

Table 5.

Table of related to the Figure 7, where the accessibility ranges are explained, including optimal, favourable, poor or very poor accessibility. Source: own elaboration.

3.2. Archaeological Dimension of Castile and Leon and Cantabria

The other fundamental pillar of this research is archaeological cultural heritage. In recent times, the meaning of cultural heritage has been developed at the same time as the need to protect it has grown. In its evolution, it has incorporated more and more heritage elements—in fact, it is called cultural heritage because it encompasses everything: historical, industrial, tangible and intangible, etc.—that did not exist in its conception at the beginning and during most of the 20th century. Furthermore, the scale on which it is understood has been progressively broadened. That is to say, we have moved from the singular element—the building—without taking into account its surroundings, to the consideration of heritage on a territorial level. This evolution from an individualised concept of assets to a current holistic view directly relates heritage to the territory and the society that inhabits it, forming a heritage whole that defines and characterises the cultural landscape [8].

This need to protect cultural heritage assets has led to numerous legislations that include, in the case of Spain, regional particularities, in the definitions and protections of numerous figures that comprise the Spanish cultural heritage. Firstly, Law 16/1985 [11] was developed, which was applied in the whole of the Spanish territory. In it, five protection categories were approved: historical complex, historical garden, monument, historical site and archaeological site. Nevertheless, this country is one of the most decentralised countries in Europe, since from the 1980s, the competences in various subjects have been ceded to the Autonomous Communities, covering cultural heritage protection and management. Since then, each of the Spanish regions has developed their own heritage law, including both Castile and Leon and Cantabria. The first was the Law 11/1998 of the 13th of October of the Cultural Heritage of Cantabria [16]. Four years later, the Law 12/2002 of the 11th of July of the Cultural Heritage of Castile and Leon [17] was approved. However, even though Cantabria still has its first law, Castile and Leon has recently approved a new law—Law 7/2024 of the 20th of June [18], derogating the former one, and the one that establishes the legal frame of this paper. Both of the actual regional laws include the figures of protection from the National Law of 16/1985 [11], but they also include new classifications that are needed for the type of goods that need to be protected. For example, on the one hand, the Cantabrian law considers figures such as ethnological interest sites and paleontological sites, all of them inside the frame of the classification of the historical place. The recent Castilian law, on the other hand, divides the figures between individual assets—in which the monuments or the historical gardens are included—or heritage areas, which involves wider protections: historical complex, historical site, archaeological site, ethnological complex, historical paths, industrial complex or cultural landscape. As seen, each region decides upon the protection of the cultural goods. This situation is especially delicate in the border areas of the Autonomous Communities, as the numerous legislations protect the same type of goods differently and without establishing relations between them, taking into account that when some of those assets were constructed the actual borders did not exist.

As said, until now, the vast majority of cultural assets have been protected on an ad hoc basis, disconnected from their context and without taking into account the system of relationships that make up the territory and in which human actions take place [24]. For this reason, it is essential to move away from the objective, since these heritage elements are intrinsically linked to the physical support where they are located [8] and disconnected from the system of relations that conform the heritage territory they are in. Moreover, it is necessary to act on a large scale to stop territorial imbalances such as depopulation [25], strengthening the socio-economic fabric of vulnerable communities with new sustainable opportunities [6].

Therefore, this research seeks to understand the archaeological sites in the same way, with a synergic and joint vision, in order to find the historical territorial heritage that will help us to understand the current dynamics of and value this heritage in rural areas, providing the keys by which the adjacent land has been ordered. The reasons why archaeological heritage has been chosen specifically are, on the one hand, because it is linked to a historical territorial heritage that will help to understand the current dynamics and to value the archaeological heritage of rural areas. Archaeological heritage responds to a territorial-scale heritage that is closely linked to the cultural landscape and can help us to understand past landscapes and anticipate future changes, thus defining future objectives for all stakeholders [26]. Therefore, it deserves special attention in territorial planning due to the risk of destruction to which it is subjected [24]. However, even though the protection figure of archaeological sites is present in both regions, it is important to point out that there are no common criteria either in the protection or management of archaeological heritage in the Heritage Laws or in the Territorial Management Plans at the state level.

3.3. Opportunity Areas of Castile and Leon and Cantabria

As noted, opportunity areas are going to be identified, among others, through the knowledge of accessibility to cultural heritage, thanks to which it is possible to understand the degree of well-being of a population, as they must have access to basic services such as a wide cultural offering [8]. It is also an indicator of equity, as the universal coverage of quality facilities and services is necessary for citizens. In addition, good accessibility can improve connectivity between territories and could assist in positive economic, social and cultural development [27].

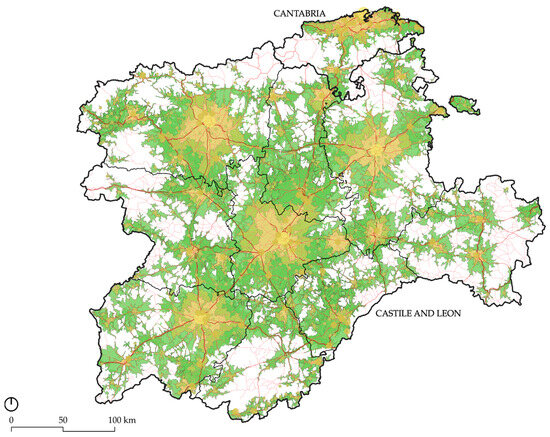

Employing the aforementioned layers, the municipalities at risk of depopulation, the archaeological sites—those in areas in risk of depopulation—and the isochrones from 20% of the most populated cities, together with the road infrastructures, a summary plan is established on which the opportunity sites will be drawn (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Summary plan indicates the proposed area of opportunity: brown lines network between numerous archaeological sites (brown points). This plan has been done over the previously explained Figure 5a (related to Table 2, Figure 7 and Table 5) with the layer of the main road network (connected red lines) and pointed the provincial capitals (white dots), and regional capitals (black dot in white dot). Source: own elaboration based on the National Geographical Institute’s cartography.

In the summary plan, it can be seen that, in general, both Autonomous Communities are accessible to a large percentage of their territories, and they are more inaccessible in the border areas between them or with other regions.

Once the accessibility of the most populated cities to the archaeological sites of the Autonomous Communities of Cantabria and Castile and Leon has been exposed, the aim is to propose territorial units with common characteristics, as these recognise areas that have historically been linked, protecting settlement systems that share identity traits [12].

In this case, the areas of opportunity are defined by three points that del Merino del Río [12] explains: because the settlements are grouped following the recognisable morphotypes of accessibility, because the rural environment shares common features with areas at risk of depopulation, and because the settlements being studied, in this case, the archaeological sites, follow the same dynamics—of abandonment and destruction.

On the border of both regions, archaeological sites are located in rural areas at risk of depopulation, and with certain accessibility from the main cities. Between these archaeological sites, networks of relationships can be established due to their typology, origin or monolithic character, which could strengthen them and reactivate the territory.

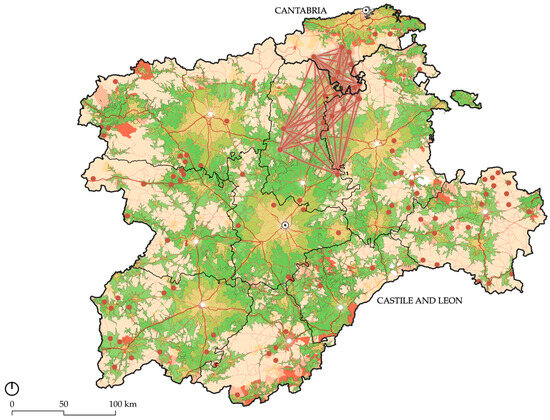

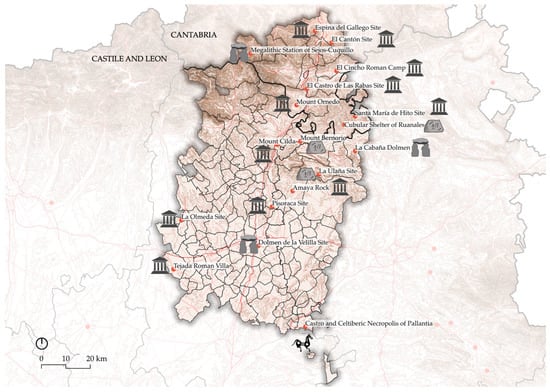

As seen in Figure 9, an area that includes eighteen archaeological sites has been selected. This zone is formed by 152 municipalities from three different provinces: Palencia, Burgos and Cantabria.

Figure 9.

Chosen municipalities and the archaeological sites –red points– over the main road network in red lines. Source: own elaboration based on the National Geographical Institute’s cartography.

In Table 6, it can be observed that the archaeological sites come from different times and belong to numerous types. The occupation of this area is dated to have started when megalithism was the way of construction, such as with the Dolmen de la Velilla Site or the Megalithic Station of Sejos-Cuquillo. Thereafter, the Iron Era it also left numerous heritage goods behind, such as the Cubular Shelter of Ruanales, Mount Bernorio or la Ulaña Site. This shows the historical value of occupation of this territory for successive centuries, starting in the early years of prehistory. Nevertheless, there is a period that continuously comes to light: that between Pre-Roman Hispania and the successive Roman period. Many of these vestiges are related and were important for the Cantabrian Autonomous Communities of the Pre-Roman period. In the year 29 BC, the Cantabrian Wars started between the local inhabitants and the Roman Empire under Augusto’s mandate, who sought to conquer this territory [28]. The war endured for almost ten years, ending with the Roman victory, finally leaving the Iberian Peninsula in peace. After this period, the Romans reused the previous places of the Cantabrians, some of which are listed above: the Pisoraca Site, Amaya Rock, Mount Ornedo, Mount Bernorio, El Canton and the Espina del Gallego Site. To these must be added the new constructions proposed by the new occupants of the territory, such as Mount Cilda, Castro de las Rabas Site, el Cincho Roman Camp, Tejada Roman Villa, the La Olmeda Site or the Santa Maria del Hito Site.

Table 6.

Table of the archaeological sites in the opportunity zone, including the municipality and province they belong to, their type and the altitude they are in. Source: own elaboration with data from the National Geographic Institute.

Moreover, taking a look at the altitude, leaving el Canton aside, the rest of the sites in the territory are at high altitudes, with the Megalithic Station of Sejos-Cuquillo being at the highest point. Curiously, the megalithic constructions are those situated at the highest altitudes, followed, in general, by those from the Iron Era or the Pre-Roman period. The high positions, chosen during the earlier times, offered good visibility and presented the domain of the territory. In the Roman period, as it was a peaceful era, defence and vigilance were not so important, and the people chose lower zones in the territory.

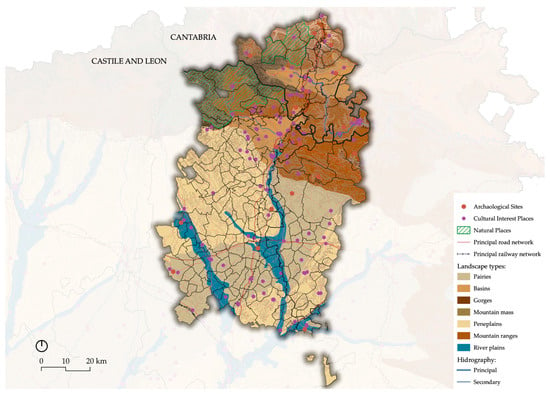

Once the historical context of the area was defined, an approach to the landscape characterisation of those municipalities was carried out. It is recognised that representing the archaeological sites with points removes them from their immediate context, but no one methodology can summarise every aspect of a place [29]. Therefore, a wide range of data has been collected in order to present the area through its landscape assets (Figure 10)—this would now need to be negotiated considering different viewpoints, as landscape is recognised to be subjective [30]. Nevertheless, what people perceive from the landscapes is rooted in materiality [31], and therefore, a first approach to the landscape characterization of the area is proposed. In this context, some of the structural elements of the territory of study are included, both natural and anthropic. Inside the first group, we can find elements such as hydrology, topography or the natural protected areas. The main hydrological network (blue) comes from the rivers of Pisuerga—that crosses from the north to the south of the study zone, Carrion—the southwestern part of the area—and Ebro, on the northeastern side of the sector. The topography (brown) shows that the northern third is at a higher altitude than the southern part. In relation to natural protected areas (green, striped pattern), there are two at the northwestern side of the territory: the Natural Park Saja-Besaya and the Natural Park of Fuentes Carrionas and Fuente Cobre. All these natural assets show that the boundaries do not specifically relate to an administration division, not at a regional scale nor a provincial one.

Figure 10.

Chosen municipalities and the archaeological sites. Source: own elaboration based on the National Geographical Institute’s cartography.

The second group, related to the anthropic elements, however, includes the populations and the main transport infrastructure, such as the A-67 and N-611 main roads (red) from north to south that join Santander and Palencia, and the A-231 and N-120 main roads that unite Leon and Burgos, from east to west. Furthermore, the railway system is exposed (black), with the lane that follows the highway from Santander–Palencia and another one that links Leon with Bilbao and crosses through the east and west the of the northern study area.

Finally, the cultural layer comes from the archaeological sites previously identified: the cultural itineraries (purple) and the points of interest the National Geographic Institute believes are important (purple), including other protected goods or reference elements for the society, such as churches. The cultural itineraries can be divided in two main branches: that of the northern paths and that related to the French “Camino de Santiago”. Lastly, it is important to reinforce the idea of the great potential these cultural assets have, as they belong to different periods of time that reinforce the idea of the value of use of these territories.

Considering all the previous elements, an advance towards the cultural landscape characterization of the area has been made through the proposal of a rural interregional zone, seeking to contribute to a more sustainable territory through the resilience of the archaeological heritage system.

4. Discussion

The results sought from this research have been obtained, and a cultural landscape of opportunity has been proposed at the frontier between Castile and Leon and Cantabria. This could reactivate the border areas at risk of depopulation, which are generally the furthest away from the centres but are accessible and with great archaeological heritage potential.

The chosen heritage goods are in rural areas that are at risk of depopulation with less than 25 inhabitants/km2 and an average household income of between EUR 20 and 30 thousand. In all of them, archaeological heritage on a larger scale allows for the recognition of historical territorial patterns and can generate identity through the restoration of landscape formation dynamics, creating synergies between municipalities in different regions with different cultural heritage and territorial planning legislation but a common physical environment that does not respond to the administrative division. Moreover, the situation of these division areas is quite delicate as the legislation of territorial planning and cultural heritage—among other things—is ceded to the regions, so on both sides of the line, the management of the territory is different, making it tremendously vulnerable. Therefore, it is believed that a certain amount of homogenization is needed in these management and protection legislation tools and have the Autonomous Communities working in cooperation and collaboration to alleviate the problems created in the border.

The area of opportunity has been delimited on the basis of the territorial criteria themselves, exposing the accessibility to the archaeological assets in rural depopulated municipalities and characterising them through the specification of their archaeological time and the physical elements and landscape type that made the ancient civilizations choose that location specifically. This process uncovered an archaeological heritage system that can help us to identify the keys to the formation of some of the first historical landscapes, enabling us to understand the past and anticipate future changes in order to reactivate the area through the relation between the heritage assets. In this case, the eighteen archaeological sites defined, in general, showed the long period of occupation of the area: from the prehistoric societies that needed high altitudes to control the territory to today, where we can observe the great legacy from the Pre-Roman and Roman period. The cultural landscape where this heritage system is inserted has also been shown, exposing natural elements that define the territory, including the main rivers, topography and two natural parks. Moreover, the anthropic layer displayed the north–south and east–west transport infrastructure that has also been used for a long time, shown by the cultural itineraries.

This resulting cultural landscape that combines the two sides of the borders of Castile and Leon and Cantabria could fix the current population and be engaging for an interesting touristic cultural project. Nevertheless, a debate on the landscape characterisation of the area must be carried out, including several opinions, in order to integrate varied perceptions and allow for the integration of its dynamic quality.

5. Conclusions

Consequently, it has been shown that in the current context of overpopulation of large cities and the depopulation of rural areas, territorial balance is needed. Rural areas are places of opportunity both as habitats and as possible touristic spaces, made possible through sustainable development strategies. These plans must imply valuing natural and cultural capital and conserving it, starting with their first vestiges, which are materialised and protected through the figure of the archaeological sites in Spain. Nevertheless, these sites are at risk of abandonment and destruction because they have been individually safeguarded, and, therefore, it is important that they are recognised and protected on a large territorial scale, including all the landscape layers that characterise the area, especially in areas that are on the border of different Autonomous Communities. This would create synergies among those localities that could result in a more than appealing cultural offer.

In future research, the archaeological landscape could be enhanced by proposing a cultural itinerary among some of the sites at a territorial scale, maybe between those of the same period. Thus, it could be useful to identify which of the sites have interpretation centres. If they do not, it could be suggested to build one at the beginning of the proposed cultural itinerary, which would bring together all the sites through a common discourse, making it easier for citizens to understand and easily identify with them.

However, it would be necessary to look more closely at other forms of heritage protection, both tangible and intangible, since for reactivation to be effective, it is not only archaeological areas that should be taken into account. Moreover, the subjective component of the cultural landscape makes it mandatory to involve local inhabitants in the debate, as they are the ones who live in the territory and find their identity in the heritage goods. On the other hand, it would also be important to include digital accessibility as well as physical accessibility, since in the current era of digitalisation, it is essential for local and regional development, as well as for national and international dissemination.

Nevertheless, in conclusion, we have shown the great potential of rural depopulated areas, and if interregional municipalities come together, they can really strengthen the heritage layer of the cultural landscape, making the territory more resilient and definitely more sustainable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T.P.C. and A.M.A.; methodology, M.T.P.C. and A.M.A.; software, A.M.A.; validation, M.T.P.C.; formal analysis, M.T.P.C. and A.M.A.; investigation, M.T.P.C. and A.M.A.; resources, M.T.P.C. and A.M.A.; data curation, M.T.P.C. and A.M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.A.; writing—review and editing, M.T.P.C.; visualization, M.T.P.C. and A.M.A.; supervision, M.T.P.C. and; project administration, M.T.P.C. and A.M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

These data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain: National Geographical Institute https://www.ign.es/web/cbg-area-cartografia (accessed on 17 December 2024) and Spanish National Institute of Statistics https://www.ine.es/ (accessed on 17 December 2024).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported with the predoctoral employment contract (PIF) Ainhoa Maruri has with the University of Seville, within the frame of the VIIth Own Research and Transfer Plan.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pinilla, V.; Saez, L.A. Rural depopulation in Spain: Genesis of a problem and innovative policies. Cent. Stud. Depopulation Dev. Rural Areas (CEDDAR) Rep. 2017, 2, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank, Panorama General del Desarrollo Urbano; Banco Mundial BIRF, AIF: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- Campisi, M.T. Depopulation of small urban centers. Cultural landscape as a resource for local communities. Resil. Between Mitig. Adapt. 2020, 3, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación (MAPA). Demografía de la población rural en 2020. S.G. Análisis, coordinación y estadística. AgrInfo 2021, 31, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Del Espino Hidalgo, B.; Horeczki, R. Innovative and Sustainable Cultural Heritage for Local Development in the Face of Territorial Imbalance. Archit. City Environ. 2022, 17, 11374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Salinas, V.; y Romero-Moragas, C. El patrimonio local y el proceso globalizador. Amenazas y oportunidades. In La Gestión del Patrimonio Cultural; Alonso Sánchez, J., Castellano Gámez, M., Eds.; Apuntes y casos en el contexto rural andaluz; Ara/Asociación para el Desarrollo Rural de Andalucía: Granada, Spain, 2008; Volume 4, pp. 17–29. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11441/84787 (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- ICOMOS. ICOMOS-IFLA Principles Concerning Rural Landscapes as Heritage. In Proceedings of the 19th ICOMOS General Assembly, New Delhi, India, 11–15 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Del Espino Hidalgo, B.; Rodríguez Díaz, V.; González-Campos-Baeza, Y.; Falcón, S. Indicadores de accesibilidad para la evaluación del patrimonio cultural como recurso de desarrollo en áreas rurales de Huelva. ACE Archit. City Environ. 2020, 17, 11375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarero Rioja, L.A. Los patrimonios de la despoblación: La diversidad del vacío. PH Boletín Del Inst. Andal. Del Patrim. Histórico 2019, 27, 50–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros-Arias, P.; Otero Vilariño, C.; Varela-Pousa, R. Los Paisajes Culturales desde la arqueología: Propuestas para su evaluación, caracterización y puesta en valor. ArqueoWeb. Rev. Sobre Arqueol. En Internet 2005, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Law 16/1985, of the 25th of June, of the Spanish Historical Heritage. «BOE» num. 155, of 29/06/1985. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/l/1985/06/25/16/con (accessed on 16 November 2024).

- Merino del Río, R. Towards a landscape project from territorial heritage. Estud. Geográficos 2022, 83, e094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruri Arana, A. El Patrimonio Cultural Como Recurso de Desarrollo Sostenible de los Territorios en Despoblación: La Accesibilidad al Legado Rural Español (Unpublished Master’s Thesis) 2023, University of Seville, Seville. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11441/158032 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Dijkstra, L.; Hamilton, E.; Lall, S.; Wahba, S. ¿Cómo Definir Ciudades, Pueblos y Áreas Rurales? ONU-Hábitat. (25 de enero de 2021). Available online: https://onuhabitat.org.mx/index.php/como-definir-ciudades-pueblos-y-areas-rurales (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Government of Navarre. Estrategia de la Lucha Contra la Despoblación de Navarra; Department of Territorial Cohesion. Government of Navarre, Spain, 2023; Available online: https://administracionlocal.navarra.es/areas/despoblacion-estrategialuchadespoblacion/default.aspx (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Law 11/1998, of the 13th of October, of Cultural Heritage of Cantabria. «BOE» num. 10 of 12/01/1999. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es-cb/l/1998/10/13/11/con (accessed on 16 November 2024).

- Law 12/2002, of 11th of June, de Cultural Heritage of Castile and Leon. «BOE» num. 183, 01/08/2002. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es-cl/l/2002/07/11/12/con (accessed on 16 November 2024).

- Law 7/2024, of 20th of June, de Cultural Heritage of Castile and Leon. «BOE» num. 177, 23/07/2024. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es-cl/l/2024/06/20/7 (accessed on 16 November 2024).

- Mikhailenko, A.V.; Ruban, D.A.; Ermolaev, V.A. Accessibility of Geoheritage Sites—A Methodological Proposal. Heritage 2021, 4, 1080–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oficina Nacional de Prospectiva y Estrategia del Gobierno de España (ONPEGE) (coord.). España 2050. Fundamentos y propuestas para una Estrategia Nacional de Largo Plazo; Ministerio de la Presidencia: Madrid, Spain, 2021; Available online: https://www.cedid.es/es/buscar/Record/563647 (accessed on 16 November 2024).

- Bank of Spain. The Spatial Distribution of Population in Spain en el Annual Report 2020; Bank of Spain: Madrid, Spain, 2021; pp. 247–293. Available online: https://www.bde.es/wbe/es/publicaciones/informes-memorias-anuales/informe-anual/informe-anual-2020.html (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Vidal Domínguez, M.J.; Fernandez Portela, J. El reto demográfico en Castilla y León (España): Una región desequilibrada y envejecida poblacionalmente. Perspect. Geográfica 2022, 27, 76–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viñas, C.D. El Estado Actual del Proceso de Despoblación de los Espacios Rurales de Cantabria. Nuevas Realidades Rurales en Tiempos de Crisis: Territorios, Actores, Procesos y Políticas: XIX Coloquio de Geografía Rural de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles y II Coloquio Internacional de Geografía Rural; Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2018; pp. 147–162. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Cacho, S. Patrimonio Arqueológico y Ordenación del Territorio en Andalucía; FUNDICOT Asociación Interprofesional de Ordenación del Territorio: Valencia, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- De las Rivas, J.L.; Castrillo-Romón, M.A.; Fernández-Maroto, M.; Jiménez-Jiménez, M. Morphology of traditional landscapes in inland Spain: The potential of the rural built environment in a more sustainable future. Ciudad Y Territorio. Estud. Territ. 2022, 53, 179–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, T.; Guichard, V.Y.; Álvaarez Sanchís, J. The place or archaeology in integrated cultural landscape management. J. Eur. Landsc. 2020, 1, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado Villa, M.P. Paisajes de la Movilidad Cotidiana. Puesta en Valor de los Accesos a la Ciudad Media Andaluza. Ph.D. Thesis, Depósito de Investigación de la Universidad de Sevilla, Seville, Spain, 2017. Available online: https://idus.us.es/handle/11441/71328 (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Solar, R. Las guerras Cántabras. Hist. Rei Mil. Hist. Mil. Política Y Soc. 2014, 7, 71–75. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, S.; Fairclough, G. Common culture: The archaeology of landscape character in Europe. In Envisioning Landscape: Perspectives and Politics in Archaeology and Heritage; Hicks, D., McAtackney, L., Fairclough, G., Eds.; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 120–145. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. European Landscape Convention; Florence 20. 10. European Treaty Series, No. 176; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2000; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, S. Landscape Archaeology for the Past and Future: The Place of Historic Landscape Characterisation. Landscapes 2007, 8, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).