Abstract

While the concept of Post-Occupancy Evaluation (POE) is widely applied in landscape architecture and other relevant fields, the term POE is not well-defined. By reviewing and analysing a representative set of POE definitions collected from existing academic and grey literature using content analysis methods, this study aims to enhance understanding of the breadth of the concept and its relevant practices. Our research found that the concept of POE was developed in architecture in the 1970s and subsequently adopted in landscape architecture in the 1980s. With the growth of the field in architecture and its adaptation to landscape architecture, the scope of POE was significantly expanded over recent decades, and with this growth, there have been considerable divergences in definitions and understandings of how to carry out POE. A range of different evaluation objects and four evaluation models were identified by this study. By surveying the conceptual terrain of POE, our research establishes the need for practitioners to be aware of the breadth of the concept and the potential ambiguity surrounding what is meant by the approach. Consequently, practitioners need to be specific and explicit about their understanding of POE. The findings also demonstrate how interdisciplinary differences appear to have been overlooked when adapting POE from one discipline to another. We, therefore, argue that it is crucial to keep shaping and trimming the concept to support the adaption of POE processes into different disciplinary domains.

1. Introduction

Post-Occupancy Evaluation (POE) is a type of assessment approach commonly used in the design and planning disciplines [1,2]. The main focus of such assessments is to understand and evaluate how a built work functions in reality after it is constructed and occupied. POE is applied in a wide range of environmental design disciplines and professions, including landscape architecture, architecture, urban planning, and other relevant fields. This type of evaluation is always carried out after the built work has been occupied or been in service to allow the users to fully experience the design and for potential problems to become apparent [3]. As argued by numerous scholars and practitioners [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15], evaluating the actual performance of implemented designs is considered highly important for the healthy growth of the environmental design discipline and to help the relevant professions to better understand how their design solutions work in reality and, therefore, contribute to a better-performing built environment. There is a considerable number of studies published around POE since the late 1960s. However, the term and the concept of POE remain contested.

It is argued by many scholars and practitioners that there is no industry-accepted definition for the term POE. Hadjri and Crozier [16] suggest that, due to the ‘mutability’ of the concept of POE, there is no definitive agreement concerning what POE actually is, and the term is adopted to refer to a wide range of practices. This means that different scholars and professionals perceive the concept differently when using and understanding this term in academic and professional communications. A similar observation is stated by Hiromoto [17], who argues that an assortment of services has come to be covered by the concept today. Hadjri and Crozier’s [16] research also pointed out that, due to the ‘mutability’ of the concept, a variety of attempts had been made to define it. However, the scope of and the methodologies for POE are getting more diverse, with increasingly wide-ranging positions on what should be included in a POE and how to conduct it [18,19]. This makes the concept even more complex and more challenging to be encapsulated in a single definition without systematically reviewing the idiomatic use of the term and its evolving process. A beneficial attempt is made by Hosey [19], who suggests that, among the various possibilities, two common focuses of POE practices are (1) how well a design project is meeting its design intentions and (2) how satisfied the occupants of the project are. Another contribution to the understanding of the breadth of POE regarding its forms and focuses was made by Hadjri and Crozier [16], who suggest that POE can be explored not only architecturally, but also psychologically and sociologically, and at same time can have various focuses, ranging from technological aspects to socio-psychological interests. Such attempts provide future research with a good basis to further clarify the concept and map its terrain by using a systematic and empirical approach.

Apart from the ill-defined concept and term of POE, another challenge for the evaluation-related terminology in the environmental design field is the existence of a large amount of weakly defined “alternative” concepts and terms for POE-type practices, including Landscape Performance Evaluation (LPE) (or landscape performance assessment), environmental audit, environmental design evaluations, facility assessment, building performance evaluation, building appraisal, building evaluation, building-in-use assessments, building pathology, and building diagnosis 1 [3,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. These “alternative” terms are used to refer to a series of similar concepts that are closely related to each other, but at the same time are not absolutely the same. Further, clear distinctions between these terms and POE have not been clearly defined in the literature. A question highlighting the terminology dilemma was raised by Duffy [22] and remains unanswered: how do concepts such as building appraisal differ from POE, and how are they interrelated (e.g., subset, intersection, or parallel)? Conducting a systematic review of the use of the concept and terminology of POE is the first step to answering the remaining question and legitimising the academic and professional use of the concept and the term.

As a result of the lack of a definitive way of using the term and the concept, the phrase ‘Post-Occupancy Evaluation’ was observed to be interpreted literally in some cases [28,29]. However, as the term itself is not transparent and inclusive enough to comprehensively denote the blend of various concepts and practices covered by the concept today, the term is considered misleading in some cases [30]. It is observed by Preiser [29] and Riley, Kokkarinen and Pitt [28] that the term ‘Post-Occupancy Evaluation’ gives the misconception that a POE is a one-off inspection and should only occur once a project is constructed and occupied. Yet, it is argued that a collective view from specialists in the field assumes that such evaluations should not be a one-off practice, rather, POE should be a recurring process accompanying the entire project delivery cycle [29,30]. The misconception of the concept also hints at the necessity to study the current idiomatic usage of the term and its semantic evolvement, and further, to legitimise the use of the concept.

The conceptual and terminological fuzziness of POE is a prominent issue. The extensive range of possibilities for what is covered under this umbrella concept and what are the possible approaches to conducting such evaluation means that it is challenging to achieve a global view of POE and to conduct an evaluation in a comprehensive manner. A comprehensive ‘map’ is needed to help potential future evaluators to navigate through the complex ‘terrain’ of POE. However, no known empirical research has focused on mapping the complex and fragmented terrain of the concept and term use of POE, as well as its development in recent decades. This study seeks to examine the complexity and fragmentation of the terrain of POE and to characterise the various practices covered by the concept today. The research objectives are to (1) explore the key agreements and divergences in how POE is defined by different scholars and practitioners and how these agreements and divergences are shaped by the disciplinary context, (2) investigate how the concept was evolved throughout history and how it is shaped by the growth of the discipline and the industry, and (3) characterise the key existing models (i.e., the focus of an evaluation and how an evaluation is conducted) of POE practices.

2. Methods

This study collected, analysed, and characterised a representative collection of written Post-Occupancy Evaluation (POE) definitions embedded in both academic and professional publications. The methods are outlined below.

2.1. Collecting Definition Materials

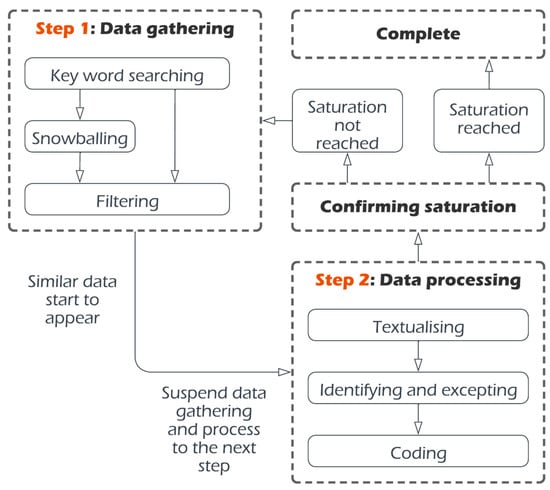

The first step of the definition study was to collect text materials containing definitions of relevant concepts or terms (as shown in Figure 1). Collected materials included both academic literature and grey literature, i.e., academic articles, reports conducted by professional institutes, academic institutions and the government, articles published on professional and academic websites and professional magazines, and books. It is worth noting that grey literature is often excluded from the data sources of many review papers. However, as POE is considered a professional practice more often than an academic practice, it is necessary to include grey literature as a source for data collection to ensure the integrity of the exploration.

Figure 1.

Overview of research methods.

2.1.1. Channels for Definition Collecting

The collected materials were sourced from three channels: academic database (i.e., Google Scholar, for academic contents), search engine (i.e., Google Search, for grey literature), and the reference lists of collected materials. For the last channel, relevant materials were identified by scanning through the titles in the reference lists of collected materials. The researchers then obtained those identified materials from a range of avenues, including academic databases, search engines, and the physical library. As for the search engine selection, we recognise that Google Search has limitations in its algorithm transparency and timeliness, as suggested by Matsler, et al. [31]. However, it is still sufficiently informative and instrumental to capture a snapshot of the current discourses distributed over the public realm [31].

2.1.2. Keywords for Searching

As POE (Post-Occupancy Evaluation) was the initial focus of this research, the keywords used for searching were initially synonyms/relevant terms of “landscape architecture” coupled with synonyms/relevant terms of “Post-Occupancy Evaluation”. However, as the data collection progressed, a series of relevant concepts and terms gradually emerged in the search process. These newly identified concepts and terms of relevance were then also used as keywords for searching (Figure 1). The keywords used for definition collecting are listed in Table 1. Each of the listed synonyms or relevant terms of “landscape architecture” was combined with each synonym or relevant term of “POE” by using Boolean logic operators, as shown in Table 1. The combined strings of words were then used as commands for searching in the academic database and search engine.

Table 1.

Synonyms or relevant terms of “Landscape architecture” and “POE” were combined as the keywords for searching.

It is worth noting that the researchers were not trying to include all the possible terms in Table 1, as the keywords within the table were just used for initial searching. As explained above, as the searching process progressed, some more relevant terms emerged from the collected materials. These terms were also adopted as keywords for a snowballing phase of searching to help discover a wider range of materials (Figure 1). One hundred and thirteen pieces of textualised materials were eventually collected.

2.1.3. Filtering the Collected Materials

The search results from the academic database and the search engine were then filtered to screen out irrelevant information, which included materials that were obviously irrelevant to landscape architecture-related fields, materials that obviously contained no definition segment, and materials whose authors could not be identified (Figure 1).

2.1.4. Signal for Suspending the Material Collecting

Data saturation was the signal for suspending the process of collecting material (Figure 1). “Data saturation” is a term that is widely used in qualitative studies, describing the situation when there is “very little new or surprising information” achieved from collecting new data [32]. At this time, it can be considered that the diversity of data has reached “saturation”, and therefore, it is time to stop further data collecting [13,33,34].

However, it is difficult to determine whether data saturation has been reached until the collected materials were further processed and coded (The methods used for confirming data saturation are described in Section 2.3.3). Therefore, at this stage, the researchers only made approximate estimations on the possibility of reaching data saturation. Material collecting was suspended when the researchers found similar materials began to appear in the search results. However, the actual state of saturation was not yet confirmed until finishing the later coding stage (Figure 1). If data saturation was found to have not been reached in the coding stage, the research was taken back to where the material collecting had been suspended and the collecting was resumed for obtaining more materials (Figure 1). The material collecting was formally completed with the confirmation of data saturation in the coding stage.

2.2. Processing the Collected Materials

The collected materials were then processed into a text-identifiable format and imported into NVIVO. By using the “text search query” tool in NVIVO, the collected raw materials were processed into definition segments, which were further coded in the next step.

2.2.1. Textualizing the Collected Materials

Although most of the collected materials were in text-identifiable formats, some others were not. These included physical books, journals, and some non-copyable online contents. These materials were transferred into PDF files by scanning or screen capture. The PDF files were then processed into text-identifiable PDF files by using a character recognition programme. Through these two steps, all the collected materials were processed into text-identifiable file formats.

2.2.2. Identifying and Excerpting Definition Segments

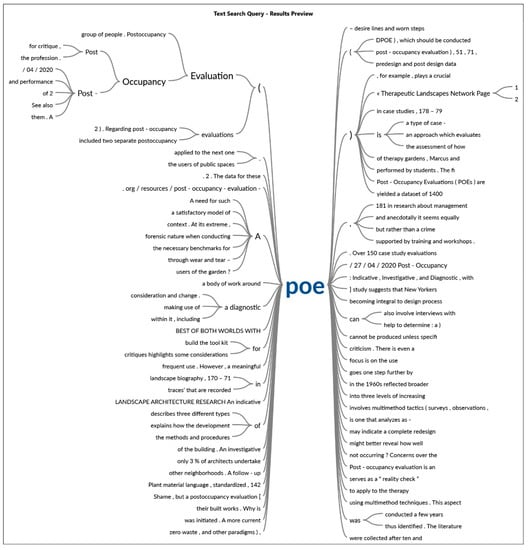

All the processed files were then imported into NVIVO. The “text search query” tool in NVIVO can conduct global text searching among all the imported files, i.e., all the imported text materials would be included in one database, and the textual information distributed in different files would be able to be retrieved with one search query. By using the “text search query” tool in NVIVO, the contexts (i.e., the words that are immediately before and after the searched word(s) in the original files) of the searched word(s) in each imported file were identified and structured into a “word tree”, as shown in Figure 2 (The word tree in Figure 2 is only an example to demonstrate the result drawn from 5 textual files. The word tree produced by the actual search query conducted is too long to fit in a page format). Some words (or word groups, or combinations of words and punctuations) such as “is”, “) is”, “as”, “was”, and “) Post-Occupancy Evaluations are” immediately after the searched terms signalled that the corresponding text segments were highly likely to be a definition. Therefore, the researchers then traced back to those segments in the original files and excerpted those segments after confirming that they were definitions.

Figure 2.

An example “word tree” exported from NVIVO.

2.2.3. Products from This Step

Forty-six definitions were eventually excerpted in this step, as shown in Appendix A.

2.3. Coding Excerpted Definition Segments

The excerpted definition segments were then coded to draw the key ideas from texts.

2.3.1. Open Coding

Open coding is often the first step of content analysis [35]. In this step, the collected text data (definition segments) were broken into discrete parts, with codes specifically assigned to each of them to draw every identifiable idea from the texts [35]. As the term “open coding” itself suggests, researchers should try keeping themselves opened up to all kinds of theoretical possibilities in this step of coding and avoid being influenced by their preconceived notions to minimise the biases that would possibly arise from the coding process [36,37]. Therefore, no predetermined codes were introduced in this stage. Instead, all the codes were created in the line-by-line coding process according to the meaning conveyed by the discrete parts of texts alongside the consideration of their context. By open-coding the excerpted definition segments, 136 initial codes were created from this step, as shown in Appendix B.

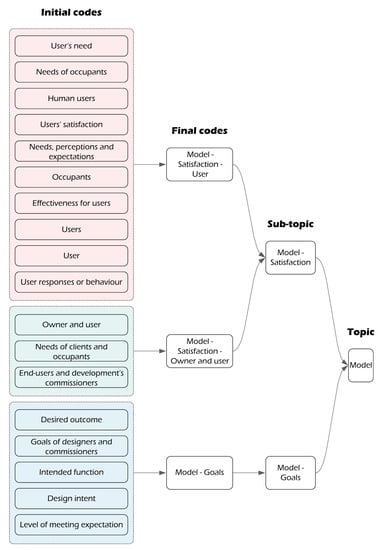

2.3.2. Axial Coding

As no predetermined codes were introduced in the initial open coding process and all the open codes were created according to the meaning conveyed by the text being coded, it can be expected that some codes created in the open coding process may be different expressions denoting very similar meanings (Figure 3). In some other cases, for example, by comparing an initial code with another (e.g., ‘owner and user’ vs. ‘desired outcome’, as shown in Figure 3), it may be found that the two codes belong to different logical hierarchies. The reason for such phenomena is that the interrelationships between and the hierarchical connections of initial codes were not considered in the open coding stage purposely. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct a comprehensive examination of the initial codes to identify the relationships between the code, as well as build a hierarchical structure for them [37,38,39]. This process is called axial coding in qualitative content analysis studies [37]. Axial coding is often the second step of coding which is normally conducted after achieving open codes [37]. In this step, the initial codes were grouped, edited, and structured to form a series of more abstract codes, which could better reflect the characteristics, trends, and divergences that underlie the texts [37,38,39,40,41,42].

Figure 3.

An example of the axial coding process demonstrating how open codes were grouped, edited, and structured into the final codes in this study.

Overall, the 136 initial codes developed in the open coding process were grouped, edited, merged, and structured into 36 final codes according to the procedure of axial coding, as shown in Appendix C. The final codes and their counts are shown in Appendix D and Appendix E, respectively.

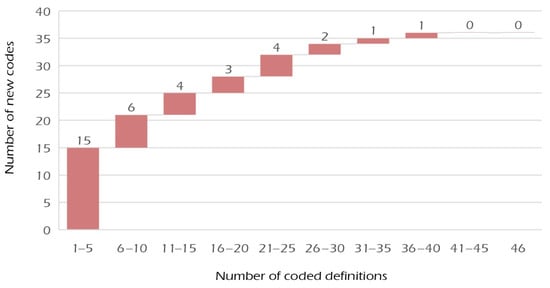

2.3.3. Confirming Data Saturation

As shown in Figure 4, a large number of new codes were quickly developed in the initial coding process. Yet, as the coding proceeded, repeating codes appeared, as some of the ideas further identified were similar to the ideas previously discovered. As a result, the number of newly created codes gradually reduced as the coding proceeded (as shown in Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The number of newly created codes (counted as the equivalent number of axial codes) reduces as the coding proceeds, and the data saturation has been reached at the end of the open coding process.

This research took 10% 2 of repetitively coded segments as the benchmark of data saturation. This means that there should be at least 10% of segments that were eventually coded without using new axial codes, or the researchers would keep collecting and coding cases until it reached the 10% threshold. In the actual coding process, among the 46 segments collected, the last seven were coded without creating new axial codes, at a proportion of 15.2% (higher than the 10% rate for determining saturation), at which data saturation is considered achieved.

2.3.4. Testing the Reliability of the Coding Framework

Coding practices are normally subjective due to the differences in understanding text materials among different individuals [44]. Therefore, in some cases, it is difficult for one coder to understand the coding result performed by another coder [41,44,45]. However, the coding difference cannot be eliminated but only minimised due to the human nature of the coders [46,47]. To minimise the subjectivity of the coding process, inter-coder agreement tests were conducted in this research to ensure the objectivity of the coding framework.

Two coders were recruited to conduct experimental coding by using the framework produced from the last step. Five randomly selected definition segments were coded by both coders. In the process of coding these segments, 185 coding decisions were made by both coders under the guidance of the coding framework. The overlapping rates of their coding results were 91.4% and 94.1%, respectively. According to Gottschalk [46], an overlapping rate of 80% is normally accepted as an acceptable margin for reliability. Since the overlapping rate of this research’s coding result is considerably higher than the acceptable margin of 80%, the high reliability of the coding framework is demonstrated.

2.4. Coding Results

Overall, 46 definitions were collected from various channels, as explained in Section 2.1. The collected definition texts are presented in Appendix A—Open coding result of POE definitions. Overall, these definitions were given by scholars and professionals from the fields of architecture, landscape architecture, and planning. The publication time of these definition texts ranged from 1978 to 2020 (as shown in Appendix A).

As explained in the previous chapter, Methods, the collected definition texts were firstly open-coded to form a range of initial codes (as shown in Appendix B). These initial codes were then edited and grouped into the final codes (as shown in Appendix D—Final coding result of POE definitions), which are analysed to identify the key agreements and divergences between the collected definitions. The level of agreements and divergences were indicated by the number of definitions sharing the same codes, as well as the existence of opposite codes reflecting counter-expressions excerpted from the collected definitions. The analyses and findings are presented below in Section 3.

3. Findings

3.1. The Common Elements of Existing POE Definitions

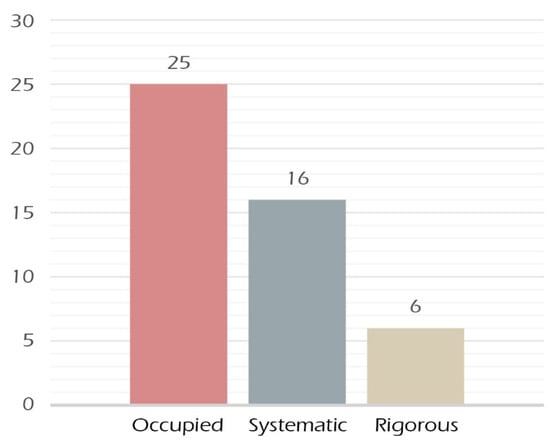

Three agreements about what a Post-Occupancy Evaluation (POE) is and how it should be conducted were identified from the collected definitions. As shown in Figure 4, the expressions that appear most frequently in POE definitions are “occupied”, “systematic”, and “rigorous”.

As shown in Figure 5, among the 46 collected definitions, 25 explicitly expressed the idea of “occupied”. As suggested by the phrase POE itself, these definitions indicate that a pre-requisite for a practice to be called a POE is that the object (i.e., the project or development) to be evaluated must be occupied. A range of expressions were adopted by these definitions to convey the pre-requisite of “occupied”, such as “in use by human occupants”, “during occupation”, and “fully operational” (a full list of the similar expressions of each final code is presented in Appendix C—Procedure of axial coding of POE definitions). Although the other 21 definitions did not explicitly express the pre-requisite of “occupied”, there were no counter-expressions about this either. This, therefore, could be assumed as an agreement among those scholars and practitioners.

Figure 5.

Agreements identified from the collected definitions.

Similarly, the expressions “systematic” and “rigorous” were indicated by sixteen and six definitions, respectively. Among these definitions, five signified “systematic” and “rigorous” at the same time. The definition given by Marcus and Francis [48], “… a systematic 3 evaluation of a designed and occupied setting from the perspective of those who use it”, for example, was coded [Systematic], while the one given by Preiser, Rabinowitz and White [10] “Post-occupancy evaluation is the process of evaluating buildings in a systematic and rigorous manner after they have been built and occupied for some time.” was coded [Systematic and rigorous] (a full list of the codes assigned to these two definitions and the other definitions coded with these codes are shown in Appendix D—Final coding result of POE definitions).

Similar expressions of “systematic” include “systematically”, “comprehensive”, and “structured”. Although approximately two-thirds of the definitions did not explicitly express the pre-requisite of “systematic” or “rigorous”, there were no counter-expressions about this either. The idea that a POE should be systematic and rigorous, therefore, was considered as an agreement among those scholars and practitioners.

3.2. The Main Divergences among Existing POE Definitions

Besides the elements commonly accepted by scholars and professionals, there are also some divergences among the definitions given by different scholars and professionals, including the objects (i.e., what to be evaluated) and models (i.e., how to evaluate) of POE.

3.2.1. The Object of a POE

The collected definitions held different opinions toward the question “what is the object of a POE?”. While some of these definitions diverge about the field of an evaluation object, others diverge about the workflow stage of an object.

3.2.1.1. The Field of the Evaluation Object

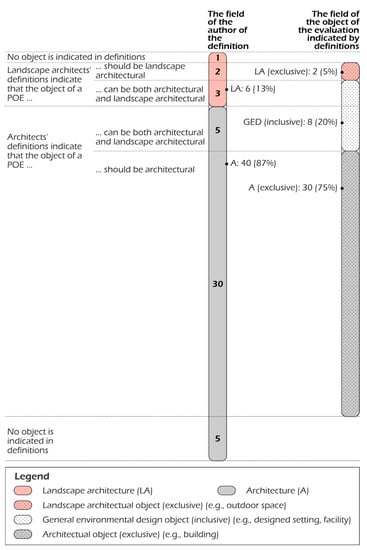

Different opinions were expressed by collected definitions regarding the field of the intended object of a POE. The opinions on this issue are closely related to the field of authors who offer those definitions. As shown in Figure 6, among the 46 collected definitions, 6 (making up 13% of the 46 definitions) were proposed by scholars and professionals in the landscape architecture field, while 40 (87%) were proposed by authors from the architecture field.

Figure 6.

The interrelationship between the field of the definition authors and the field of intended evaluation objects indicated by the authors.

As shown in Figure 6, among the six definitions given by landscape architects, two (33%) exclusively indicate that POE is a type of landscape architectural practice. For example, as proposed by Deming and Swaffield [13], “Postoccupancy evaluation (POE) is a type of case-study evaluation in landscape architecture and planning…”

By contrast, three (50%) landscape architect-proposed definitions inclusively indicate that the object of a POE can be both landscape architectural and architectural. Ozdil [9], for example, suggests that POE is defined as “the assessment of the performance of physical design elements in a given, in-use facility.”

Besides “physical design elements” and “facility”, the inclusiveness is also indicated by expressions such as “designed setting”, “designed environment”, “built environment”, and “space”. Even if these expressions appear in various contexts including both architectural and landscape architectural publications, their wording tends to be more inclusive, rather than limiting the object of an evaluation to be one of the exclusive options.

In contrast to the definitions offered by landscape architects, a majority (75%) of architect-supplied definitions exclusively indicate that the object of a POE should be architectural (as shown in Figure 6), in other words, a building, rather than a landscape development. For example, according to the National Research Council [3], “Post-occupancy evaluation (POE) is a process for evaluating a building’s performance once it is occupied.”

Among the forty definitions given by architects, there are also five (13%) that indicate inclusively that the intended evaluation objective of a POE can be both architectural and landscape architectural projects. For example, as suggested by Zimring and Reizenstein [49], “POE is the examination of the effectiveness for human users of occupied, designed environments.”

3.2.1.2. The Workflow Stages of the Evaluation Object

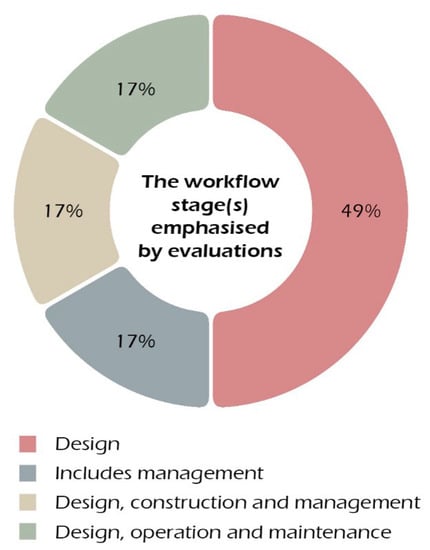

Apart from the professional field of the intended evaluation object, some definitions also indicate the workflow stage of the evaluation object. Different scholars and practitioners hold different views on this issue. As shown in Figure 7, among the scholars and professionals who indicate the workflow stage of the intended evaluation objective in their definition, half suggests that the object of a POE is the ‘design’ of a project, rather than other workflow stages such as construction, operation, and management. Ilesanmi [20], for example, suggests “POE is about procedures for determining whether or not design decisions made by the architect are delivering the performance needed by those who use the building”.

Figure 7.

The percentage of the workflow stage of the intended evaluation object indicated by the collected definitions.

Different views were expressed by others. Hadjri and Crozier [16], for example, suggest that management is also a part of the objective of a POE—“POE is a process that involves a rigorous approach to the assessment of both the technological and anthropological elements of a building in use. It is a systematic process guided by research covering human needs, building performance and facility management.”

Similarly, Preiser and Vischer [12] suggest that, apart from design, the operation and maintenance of a project are also a part of the evaluation object—“[POE] addresses the needs, activities, and goals of the people and organizations using a facility, including maintenance, building operations, and design-related questions.”

The widest evaluation scope was suggested by Roberts, Edwards, Hosseini, Mateo-Garcia and Owusu-Manu [7], who suggest that the object of a POE should include not only design and management, but also construction—“To measure a building’s operations and performance, a post-occupancy evaluation (POE) is typically utilised to determine whether decisions made by the design, construction and facilities management professionals have met the envisaged requirements of end-users and the development’s commissioners.”

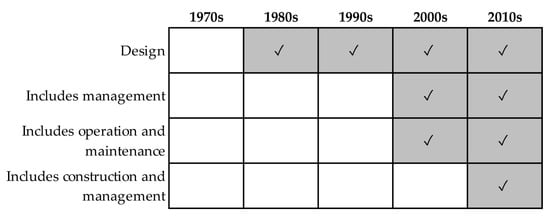

By correlating the workflow stage of the evaluation object with the time when the definitions were proposed, this research found that the scope of the POE object has been gradually widened in the past few decades, as shown in Figure 8. In the 1970s, no definition indicates what the workflow stage of a POE should be. With the further development of the concept, some definitions proposed later in the 1980s and 1990s began to define the scope of POE and regard design as the only evaluation object of a POE. The expressions which suggest that operation and maintenance (or management) are also a part of the evaluation object did not appear until the 2000s. In the 2010s, the evaluation object of a POE was further enriched to cover the construction stage as well.

Figure 8.

The trend of the inclusion of workflow stages in the evaluation objects indicated by definitions.

3.2.2. Model for Evaluation

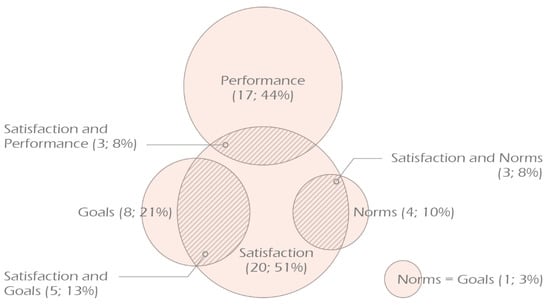

Another major divergence among the collected definitions is the model for evaluation. As Bowring [1] suggests, the nature of a normative critique is to compare the actual performance of a project with the performance of an ‘ideal project’. POE, as a type of evaluation with a clearly normative purpose, can be considered the same in nature, comparing the actual performance of a project with the ‘ideal’ performance of the project. It is also suggested by Deming and Swaffield [13] that “a meaningful POE cannot be produced unless specific standards or criteria are available for comparison.” By coding the collected definitions, this research found that the ‘ideal condition’, ‘standards’, or ‘criteria’, with which the actual performance is compared, is defined differently by different scholars and practitioners. As shown in Figure 9, there are generally four types of models indicated by the definitions for defining the ‘ideal’: satisfaction, performance, goals, and norms.

Figure 9.

The evaluation models indicated by the collected definitions and their count.

Among the 46 collected definitions, 39 contain expressions related to the evaluation model. In addition, among the 39 definitions, as shown in Figure 9, 20 (51%) adopt the model of satisfaction. Second only to the satisfaction model, the performance model is indicated by 17 definitions, accounting for 44% of the 39 definitions which contain model-relevant information. This type of evaluation model tends to be more holistic or general than the satisfaction model (this is explained in Section 3.2.2.4 in detail). Apart from the satisfaction model and the performance model, there is also a small portion of definitions that indicate that a POE should evaluate a project against its goals or certain norms. These two types of evaluation models make up a proportion of 21% and 10%, respectively.

There are also some definitions, which adopt more than one model. Among the thirty-nine definitions, five (13%) definitions indicate that a POE should consider both the goals of a project and the satisfaction of a certain group of stakeholders. Three (8%) definitions adopt the satisfaction model and the norm model at the same time. Satisfaction and performance have been mentioned simultaneously by three definitions as well, which make up a proportion of 8%. One definition suggests that both norms and the goals of a project should be considered when conducting a POE and, ideally, the goals of a project should be integrated with certain norms. All these evaluation models are explained in detail in the following sub-sections, along with corresponding definitions.

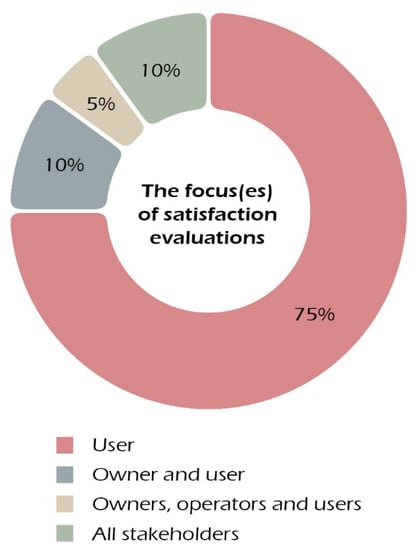

3.2.2.1. Evaluation Model—Satisfaction

As explained previously, the satisfaction model is adopted by 20 definitions. Among these 20 definitions, there are further divergences on whose satisfaction should be considered. As shown in Figure 10, three-quarters of these definitions indicate that the emphasis should be placed on the users and the nature of a POE is to measure how satisfied users are with the project.

Figure 10.

The percentage of the groups emphasised by the definitions which adopt the satisfaction model.

The definition offered by Friedmann, et al. [50], for example, is a users’ satisfaction-oriented definition—“POE is an appraisal of the degree to which a designed setting satisfies and supports explicit and implicit human needs and values of those for whom a building is designed.”

In addition, 10% of the satisfaction-oriented definitions consider not only users’ satisfaction, but also the design commissioners’ satisfaction. For example, Roberts, Edwards, Hosseini, Mateo-Garcia and Owusu-Manu [7] suggest “… a post-occupancy evaluation (POE) is typically utilised to determine whether decisions made by the design, construction and facilities management professionals have met the envisaged requirements of end-users and the development’s commissioners.”

Furthermore, in addition to users and owners, the operators of a project are also taken into account in an evaluation by the National Research Council [3]—“… A POE necessarily takes into account the owners’, operators’, and occupants’ needs, perceptions, and expectations.”

3.2.2.2. Evaluation Model—Goals

In contrast to the definitions adopting the satisfaction model, the goal-oriented definitions do not consider satisfaction. According to this evaluation model, a POE should evaluate a project against the original goals set up for the project, instead of measuring the satisfaction of a certain group as suggested by the satisfaction model. For example, as suggested by Arnold [11], “Post-occupancy evaluation (POE) is the assessment of how an existing building measures up to its design intent.”

3.2.2.3. Evaluation Model—Norms

The third type of evaluation model emphasises the use of existing external norms that are independent of the project goals and the satisfaction of certain groups. The norms invoked by the collected definitions include the established frameworks of sustainability, productivity, and resource consumption. The definition offered by RIBA, et al. [51], for example, invoked some norms in addition to the satisfaction model—“… POE is not just about energy and user satisfaction but can also include more intangible issues such as productivity, identity, atmosphere and community.”

3.2.2.4. Evaluation Model—Performance

As explained previously, there are 17 definitions adopting the performance model. This type of evaluation model tends to be more holistic or general than the three models mentioned previously. For example, as suggested by Mustafa [52], “POE is the evaluation of the performance of buildings after they have been occupied.”

Although none of the literature relating to POE explicitly connected the concept of ‘performance’ with the other three identified types of models (i.e., satisfaction, goals, and norms), the Landscape Performance Evaluation (LPE) and Building Performance Evaluation (BPE) literature offers some insights. According to Evaluating landscape performance—a guidebook for metrics and methods selection, published by the Landscape Architecture Foundation (LAF), the evaluation of landscape performance takes into account the satisfaction of relevant stakeholders, the projects’ initial intentions, as well as certain norms, such as the well-established framework of sustainability [23]. This indicates that the performance model is considered a more comprehensive and inclusive evaluation model covering all the other models explained previously. Similar views are also expressed by Preiser, et al. [53] and Preiser, et al. [54] in explaining the framework of Building Performance Evaluation (BPE). It is suggested that ‘performance evaluation’ is a more holistic concept that has grown out of POE [54]. Therefore, the performance model adopted by the POE definitions can probably be regarded as the rudiment of the concept of ‘performance evaluation’ before it grew out of the concept of POE.

3.2.2.5. Evaluation Model—Satisfaction and Performance

As shown in Figure 9, there are also overlaps between different evaluation models. For example, there are three definitions adopting the satisfaction model and performance model at the same time. As explained in the previous section, according to some publications on LPE and BPE [23,53,54,55], the performance model always takes into account the elements such as satisfaction, goals, and certain norms. In addition, ‘performance’ is often used as a general term denoting various evaluation models. However, different views were indicated by the three definitions, which adopt the satisfaction and performance model at the same time. This suggests a juxtaposing relationship, rather than a subordinating relationship between the performance model and the other evaluation models. These definitions did not consider ‘performance’ as a holistic and general model, which covers elements such as satisfaction. Instead, the term ‘performance’ is adopted to specifically refer to the physical or technological aspect of a project. For example, as the definition proposed by Breadsell, et al. [56], “Post-occupancy evaluation is an established method of studying occupants of buildings for feedback and/or through measurements of building performance.”

3.2.2.6. Evaluation Model—Satisfaction and Goals

There are also overlaps between the satisfaction model and the goal model in five definitions (as shown in Figure 9). These definitions emphasise that the two considerations of a POE are satisfaction and the level of meeting original intentions or expectations. Hosey [19], for example, suggests “Today, POEs vary widely in scope, but generally they focus on two basic questions: Is the building behaving as intended? And are occupants happy with the results?”

3.2.2.7. Evaluation Model—Satisfaction and Norms

There are also three definitions combining the model of satisfaction and norms together. The definition given by Tookaloo and Smith [57], for example, includes not only elements of satisfaction, but also some norms that are independent to project goals and satisfaction—“POE is the collection and review of occupant satisfaction, space utilization, and resource consumption of a completed constructed facility after occupation to identify key occupant and building performance issues.”

3.2.2.8. Evaluation Model—Satisfaction and Norms

Although different models are jointly used by some definitions, the relationship between these different models is seldom discussed in the collected definitions and known literature. However, an insightful view is offered by Deming and Swaffield [13] to attempt to unite different models. They suggest that, ideally, the goals of a project should be well-integrated with standards or norms—“Ideally, [in a POE, the collected] data should be compared with a set of purposeful standards and norms accepted (by designers, clients, or both) as goals for the project.”

3.2.2.9. The Evolution Trend of the Evaluation Models

By correlating the adoption of evaluation models with the time when the definitions were given, this research found that the evaluation model of POE is consistently evolving through time. Table 2 demonstrates the proportion of the models’ adoption in five decades of concept development.

Table 2.

The proportion of the models’ adoption in five decades of the concept development (according to the model adopted by collected definitions).

Firstly, an overall trend demonstrated by the table is that the evaluation model of POE was getting increasingly diverse with the history of concept development. The number of types of evaluation models has been growing from one in the 1970s, to two in the 1980s and 1990s, to seven in the 2000s, and finally to ten in the 2010s. This evolution trend has also been observed by National Research Council [3] and Hosey [19], who argue “…POEs have become broader in scope and purpose…” and “today, POE vary widely in scope…”, respectively.

Secondly, there is a relatively clear shift from the prevailing adoption of the “users’ satisfaction” model in the 1970s to the wider adoption of the “performance” model since the 1980s and 1990s. As shown in Table 2, in the 1970s, the only focus of POE is users’ satisfaction. However, since the 1980s, “performance” has become one of the most commonly adopted model in POE definitions, alongside nine other models.

3.2.2.10. The Distribution Pattern of the Adoption of Evaluation Models in Different Disciplines

By correlating the adoption of evaluation models with the discipline of the definition authors, this research found that there are considerable differences between landscape architecture and architecture in adopting evaluation models. Table 3 demonstrates the distribution pattern of the model adopted in the definitions given by landscape architects and architects, respectively.

Table 3.

The proportion of the models’ adoption in landscape architecture and architecture (according to the model adopted by collected definitions).

An overall pattern presented by the table is that the model distribution is relatively more concentrated among the definitions given by landscape architects than the ones given by architects. The authors have identified two possible reasons for this pattern. Firstly, POE has a longer history in the architecture field. In the concept’s development history of more than half a century, various investigations have been carried out, with which the scope of POE has been largely expanded (as explained in the previous section). The second reason is that there are significantly more architectural researchers who specialise in POE. As a result, there are considerably more architectural publications on POE and its definition. Although the focus was on publications in the field of landscape architecture, rather than architecture, in the process of definition collection, the collected landscape architectural definitions account for only 13% of all the definitions collected, while the architectural ones account for 87% (see Section 3.2.1.1 for more details). Therefore, with a greater number of definitions available, the model adoption in architectural definitions has a greater probability of showing a more widespread pattern.

In addition, as shown in Table 3, the evaluation model that has been most frequently adopted by landscape architects is the model of ‘users’ satisfaction’. Half of the definitions given by landscape architects suggest that the nature of a POE is a type of user-oriented evaluation that mainly focuses on how satisfied the users are with a project. By contrast, the model that is most commonly adopted by architectural definitions is the performance model, accounting for 29% of the total adoption. The difference in model adoption between landscape architecture and architecture may reveal that landscape architecture lags behind architecture in the evolution from the mono-focus model of users’ satisfaction to the comprehensive performance model. The concept of “performance evaluation” was proposed in architecture in 1997, but this concept did not establish in landscape architecture until 2010 when the concept of Landscape Performance Evaluation was proposed by the LAF.

4. Discussion

4.1. One Concept, Multiple Meanings

The findings of this research echoed the observations of Hadjri and Crozier [16], Hiromoto [17], Boarin, Besen and Haarhoff [18], and Hosey [19] arguing that the concept of Post-Occupancy Evaluation (POE) is not well-defined and there are no agreements regarding what a POE is and how to conduct it. Although some fundamental agreements (i.e., occupied, systematic, and rigorous) were identified by this research, we found that there are major divergences among the objects (i.e., what should be evaluated) and models (i.e., how a project is evaluated) of POEs. Each of the divergences can lead to dramatic differences in the implementations of POE, as well as consequent misunderstandings and miscommunications, and further limit the development of robust evaluation frameworks and the delivery of effective evaluation outcomes. Therefore, it is vital to distinguish these conceptual differences. Our terrain mapping has identified a wide range of different possibilities for POE conceptualisation and has explored the breadth of the concept.

However, as argued by Matsler, Meerow, Mell and Pavao-Zuckerman [31], conceptual breadth itself is not an issue. On the contrary, we argue that the breadth of POE conceptualisations can help to bridge the gaps between different practices contributing to the performance of the built environment and can foster better collaboration between scholars and practitioners concerning different aspects of the performance of the built environment, ranging from planners, designers, builders, facilities managers, project commissioners, users, governments, and even a wider range of the general public.

Yet, the precondition for conceptual breadth to play its role as a bridge and have a positive impact is to be able to explicitly define and clearly communicate the concept. We argue that it is necessary for scholars and practitioners to be aware of the wide range of possibilities covered by the concept and explicitly specify the object(s) and model(s) of the POEs they intend to employ in their communications.

The representative range of definitions we collected demonstrates that scholars and practitioners may not often be aware of the full terrain of the concept or present its definition in a complete form. As shown in Figure 9, among the 39 collected definitions that have indicated the model of conducting POEs, 24 (62%) cover only one model, while 15 (38%) indicate 2 models. No definition covers all three models identified by this research or illustrates the relationships between them. Similarly, as reported in Section 3.2.2.1, among the satisfaction-oriented definitions, the majority of them considered the users of a project as the only party that related to satisfaction evaluation, but the other parties such as the owners, operators, and other stakeholders of a project were not considered. The satisfaction of these less-included parties, by contrast, is often also an important consideration in measuring the success of a built environment. These parties, often, more or less, have different needs and views towards a built environment and can provide valuable feedback towards the performance of a built environment. Given the fact that no collected definition covers the ‘full picture’ of POE and the scope of the collectively defined POE is much wider than each individual definition, this suggests that the scholars and practitioners who defined POE were likely not aware of the other possibilities that POE may associate with.

Although some scholars and practitioners [16,17,18,19] are aware of the issue of terminology and definition, without a systematic investigation like this study, none of the previous studies have demonstrated an awareness of the ‘whole picture’ of the concept. For example, the argument made by Hosey [19] captured two models of conducting evaluation—evaluating a project against its design intentions and according to satisfaction. However, as explained in Section 3.2.2, our investigation found that, in addition to these two models, some other scholars and practitioners believe that a built environment can also be evaluated against exterior norms, standards, or a defined set of criteria.

This study, therefore, argues that it is a crucial practice for scholars or practitioners who intend to conduct POEs or to contribute to the further discourse about POE to become aware of its conceptual breadth (i.e., the diversity of the evaluation object and model) and clearly specify the object(s) and model(s) they intend to employ if the intended POE concept has a specific scope, other than the ‘full picture’ mapped by this study.

This research also demonstrates that there is often more than one angle from which to view and examine a landscape development—high users’ satisfaction, perfect fulfilment of the original design intent, or exact alignment to a certain set of exterior criteria may not always mean a clear success of a development. Furthermore, a ‘successful’ design may not often lead to a ‘successful’ outcome. Construction, operation, management, and other processes can also be considered the objects of an evaluation. Being aware of the ‘full picture’ that has been ‘mapped’ by this study, on the one hand, can help future evaluators to avoid missing out on any key aspect of a project and make their evaluations more comprehensive. On the other hand, although some evaluations are not intended to be comprehensive, having the ‘full picture’ available can also help the evaluators to better customise and justify their evaluations and, at the same time, understand the possible limitations.

4.2. Conceptual Evolution and Inter-Disciplinary Divergence

As explained in Sections 3.2.1.2 and 3.2.2.9, the concept of POE has been continually evolving and has been shaped by the discourse around it through time. In addition, as illustrated by Figure 8 and Table 2, the conceptual breadth has been gradually expanding with time, and in comparison to the discourse in the earlier history of the conceptual development, those updated conceptualisations are obviously more comprehensive and diversified.

In addition, by correlating the conceptual differences to the disciplinary variety, this research identified a range of inter-disciplinary divergences in the conceptualisation of POE. As explained in Sections 3.2.1.1 and 3.2.2.10, respectively, the scholars and practitioners in the landscape architecture discipline apply the concept differently, in comparison to the architecture discipline in terms of the objects and models of evaluations. It is clearly signalled by the inter-disciplinary divergences how the concept has been created in the architecture field in the 1970s and adopted later in the landscape architecture field. However, this research identified that, instead of adapting the concept accordingly, the concept was adopted mechanically without sufficiently considering the inter-disciplinary differences. For example, among the collected POE definitions, more than half of the landscape architecture definitions indicate that a project has to be ‘occupied’ in order to conduct such evaluations. Yet, a considerable share of the landscape projects (some natural reserve landscapes, for example), in contrast to architectural projects (i.e., buildings, in most cases), are not designed for human ‘users’ to occupy. Even though the ultimate goal of a natural reserve is to provide certain human groups with tangible and intangible benefits through enhanced landscape services (e.g., ecological health, carbon sequestration, and cultural preservation), many of the services that can be provided by such landscapes can be achieved not necessarily from human occupancy and, therefore, cannot be reflected or examined through human occupancy either. This incongruity in concept adaptation highlights the necessity to question the nature of the concept. For example, is ‘occupancy’ an essential precondition for such evaluations? Are POEs just assessing the benefits or detriments resulting from ‘occupancy’? Tracing back to the origin, the term ‘Post-Occupancy Evaluation’, as was considered initially, originated from the occupancy permit issued by a building inspection authority in order to verify that a building had met all the requirements and was ready for occupancy [58]. The concept then evolved gradually from a one-off checklist-based assessment into a more comprehensive form later in the 1970s and 1980s [28]. The nature of POE today has already been driven further away from practices related to the occupancy permit, and the precondition, ‘occupied’, has been ‘worn down’ from the nature of the concept and should be altered to better fit a broader range of practices and applications.

5. Conclusions

As POE gradually formed through growth and adaptation in different fields, it became increasingly complex and fragmented, creating a challenging context for scholars and practitioners to conduct an evaluation. Yet, this research does not see this complexity and fragmentation as the issue itself that needs to be resolved. Instead, they were considered as a complex ‘terrain’ which requires a ‘map’ to help evaluators in navigation. The aim of this research is to provide that ‘map’.

This study investigated a representative range of POE definitions collected from existing academic and grey literature by using content analysis methods. The results show that POE is a dynamic concept evolving with time and, at the same time, has considerable inter-disciplinary divergence in its conceptualisation. This research, therefore, argues that it is important for academics and practitioners to be aware of this dynamism and remain updated in POE practices. The common agreements and the divergences presented by this study would be instrumental for academics and practitioners to quickly catch on to the ‘full picture’ of the concept, including the object of POE (i.e., what to be evaluated) and the model of conducting POE (i.e., how to evaluate). In other words, this research mapped the key ‘attraction spots’ that have been visited by the representative range of scholars and practitioners. The ‘map’ created by this study will provide future evaluators and researchers with a clear picture of what are the ‘key attractions’ to be visited and what are the possible ‘routes’ they can take. This can also help them to customise their evaluation ‘journeys’ more easily and will possibly make their evaluations more comprehensive, ensuring they do not miss any key aspects that may be of special interest to their projects.

Furthermore, this paper argues that it is also important to become aware of the interdisciplinary differences in the concept and how these differences can affect the actual POE practices. Finally, in the process of inter-disciplinary concept adaptation, it is essential to keep shaping and trimming the concept according to the nature of the disciplines. Such shaping and trimming practices, in turn, are the main drivers of the concept evolvement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.C., J.B. and S.D.; Data curation, G.C.; Formal analysis, G.C.; Investigation, G.C.; Methodology, G.C., J.B. and S.D.; Resources, G.C., J.B. and S.D.; Software, G.C.; Supervision, J.B. and S.D.; Validation, G.C.; Visualization, G.C.; Writing—original draft, G.C.; Writing—review & editing, G.C., J.B. and S.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This publication has been partially financed by the Lincoln University Open Access Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Some data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Open Coding Result of POE Definitions

Table A1.

Open Coding Result of POE Definitions.

Table A1.

Open Coding Result of POE Definitions.

| No. | Year | Author | Definition Excerpt | Initial Codes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1978 | Friedmann, Zimring and Zube [50] | POE is an appraisal of the degree to which a designed setting satisfies and supports explicit and implicit human needs and values of those for whom a building is designed. | Appraisal; Building; User; Satisfies and supports human needs and values; Explicit and implicit |

| 2 | 1980 | Zimring and Reizenstein [49] | POE is the examination of the effectiveness for human users of occupied design environments. | Examination; Effectiveness of designed environments; Human users; Occupied; Designed environment |

| 3 | 1988 | Preiser, Rabinowitz and White [10] | POE is a comprehensive, hands-on process involving research but emphasizing the on-site examination of one or a number of buildings. | Comprehensive; Hands-on; Examination and research; Building |

| 4 | 1988 | Preiser, Rabinowitz and White [10] | “POE is a systematic and formal process.” | Systematic and formal |

| 5 | 1988 | Preiser, Rabinowitz and White [10] | Post-occupancy evaluation is the process of evaluating buildings in a systematic and rigorous manner after they have been built and occupied for some time. POEs focus on building occupants and their needs, and thus they provide insights into the consequences of past design decisions and the resulting building performance. | Systematic and rigorous; After built and occupied; Building; Occupants; Needs of occupants; Consequences of past design decisions; Performance |

| 6 | 1988 | Preiser, Rabinowitz and White [10] | By analogy, POEs are intended to compare systematically and rigorously, the actual performance of buildings with explicitly stated performance criteria; the differences between the two constitute the evaluation. | Compare actual performance with criteria; Systematically and rigorously; Buildings; Actual performance; Explicitly stated criteria |

| 7 | 1988 | Preiser, Rabinowitz and White [10] | Post-occupancy evaluation. The process of systematic data collection, analysis, and comparison with explicitly stated performance criteria pertaining to occupied built environments. | Systematic; Compare with performance criteria; Explicitly stated criteria; Performance; Occupied; Built environment; |

| 8 | 1990 | Davis [59] | In 1990, a group of specialists gathered to discover ways of monitoring and measuring the general facility performance to find an answer to the question ‘What is an effective building’ and how they can measure its effectiveness. They called their process ‘Post-Occupancy Evaluation’. | Monitoring and measuring performance; Effectiveness; Building; Measure effectiveness |

| 9 | 1991 | Royal Institute of British Architects [60] | Post-Occupancy Evaluation is the systematic study of buildings in use to provide architects with information about how the performance of their designs and building owners and users with guidelines to achieve the best out of what they have already. | Systematic; Building; In use; Performance of design; Design; Owner and user; Provide architects with information and users with guidelines |

| 10 | 1995 | Preiser [29] | Post-occupancy evaluation (POE) is a diagnostic tool and system that allows facility managers to identify and evaluate critical aspects of building performance systematically. | Diagnostic tool and system; Facility manager; Identify and evaluate performance; Systematically; Building; Performance |

| 11 | 1995 | Preiser [29] | Post-occupancy evaluation (POE) is a new tool which facility managers can use to assist in continuously improving the quality and performance of the facilities which they operate and maintain. | Facility manager; Continuously improve facilities; Facility; Quality and performance |

| 12 | 1995 | Preiser [29] | Post-occupancy evaluation is the process of systematically comparing actual building performance, i.e., performance measures, with explicitly stated performance criteria. These are typically documented in a facility program, which is a common pre-requisite for the design phases in the building delivery cycle. The comparison constitutes the evaluation in terms of both positive and negative performance aspects. | Process of comparing actual performance with criteria; Systematically; Actual performance; Performance criteria; Building; Pre-requisite for design phases; Positive and negative |

| 13 | 1997 | Marcus and Francis [48] | The design recommendations in this book are largely drawn from research on existing outdoor spaces—how they are used, what seems to work, which elements are often overlooked. This kind of research is known as Post-Occupancy Evaluation (POE), a systematic evaluation of a designed and occupied setting from the perspective of those who use it. | Outdoor space; Site use; Elements that work; Elements that are overlooked; Designed; Occupied; User; Systematic; Evaluation |

| 14 | 2001 | Lackney [61] | Post-occupancy evaluation (POE) is generally defined as the process of systematically evaluating the degree to which occupied buildings meet user needs and organizational goals. | Process of evaluating; Systematically; Degree of meeting user needs and organizational goals; Building; Occupied |

| 15 | 2001 | National Research Council [3] | POE is the process of the actual evaluation of a building’s performance once in use by human occupants. A POE necessarily takes into account the owners’, operators’, and occupants’ needs, perceptions, and expectations. | Process of evaluation; Building; Performance; After use; Consider owners, operators and occupants; Needs, perceptions and expectations |

| 16 | 2001 | National Research Council [3] | Post-occupancy evaluation (POE) is a process for evaluating a building’s performance once it is occupied. | Process of evaluation; Building; Performance; After occupied |

| 17 | 2001 | National Research Council [3] | Post-occupancy evaluation (POE) is a process of systematically evaluating the performance of buildings after they have been built and occupied for some time. | Process of evaluating; Systematically; Performance; Buildings; After built and occupied |

| 18 | 2001 | National Research Council [3] | As POEs have become broader in scope and purpose, POE has come to mean any activity that originates out of an interest in learning how a building performs once it is built (if and how well it has met expectations) and how satisfied building users are with the environment that has been created. | Become broader in scope and purpose; Any activity that originates out of an interest in learning performance; Building; Perform; After built; Level of meeting expectation; Users’ satisfaction |

| 19 | 2001 | Baird [62] | Post-Occupancy Evaluation (POE), is the generic term for a variety of general programmes and procedures as well as specific techniques for the evaluation of existing buildings and facilities. | Programmes and procedures for evaluation; Existing; Building and facility |

| 20 | 2005 | Preiser and Vischer [12] | POE is a useful tool in BPE [Building performance evaluation] that has been applied in a variety of situations. | Tool of BPE |

| 21 | 2005 | Preiser and Vischer [12] | Post-occupancy evaluation (POE), viewed as a sub-process of BPE, can be defined as the act of evaluating buildings in a systematic and rigorous manner after they have been built and occupied for some time. | Sub-process of BPE; Act of evaluating; Building; Systematic and rigorous; After built and occupied |

| 22 | 2005 | Preiser and Vischer [12] | Several types of evaluations are made during the planning, programming, design, construction, and occupancy phases of building delivery. They are often technical evaluations related to questions about materials, engineering, or construction of a facility Examples of these evaluations include structural tests, reviews of load-bearing elements, soil testing, and mechanical systems performance checks, as well as post-construction evaluation (physical inspection) prior to building occupancy. POE research differs from these and technical evaluations in several ways; it addresses the needs, activities, and goals of the people and organizations using a facility, including maintenance, building operations, and design-related questions. | Differ from post-construction evaluation and technical evaluation; Needs, activities, and goals; User; Building; Maintenance, operation, and design |

| 23 | 2009 | Hadjri and Crozier [16] | POE is a process that involves a rigorous approach to the assessment of both the technological and anthropological elements of a building in use. It is a systematic process guided by research covering human needs, building performance and facility management. | Rigorous; Assessment; Technological and anthropological elements; Building; In use; Systematic; Human needs, performance and facility management |

| 24 | 2010 | Ilesanmi [20] | POE is a systematic manner of evaluating buildings after they have been built and occupied for a duration of time. (Paraphrased (Preiser, 1995, p. 3) | Systematic; Manner of evaluating; Building; After built and occupied |

| 25 | 2010 | Ilesanmi [20] | POE is a structured approach to evaluating the performance of buildings when fully operational, that is, after they have been occupied. | Structured; Approach to evaluating; Performance; Buildings; Fully operational; After occupied |

| 26 | 2010 | Ilesanmi [20] | POE is about procedures for determining whether or not design decisions made by the architect are delivering the performance needed by those who use the building. | Procedure for determining whether or not…; Design decision; Building; Performance; User’s need |

| 27 | 2011 | Arnold [11] | Post-occupancy evaluation (POE) is the assessment of how an existing building measures up to its design intent. | Assessment; Existing; Building; Design intent |

| 28 | 2011 | Deming and Swaffield [13] | Post-occupancy evaluation (POE) is a type of case-study evaluation in landscape architecture and planning that would benefit from more frequent use. However, a meaningful POE cannot be produced unless specific standards or criteria are available for comparison. This suggests that as early as possible in the life cycle of a project (perhaps even before design and construction takes place), baseline data should be collected and repeated at significant intervals. Ideally, these data should be compared with a set of purposeful standards and norms accepted (by designers, clients, or both) as goals for the project. | Landscape architecture and planning; Case-study evaluation; Specific standards or criteria; Ideally, standards and norms are accepted as goals |

| 29 | 2012 | Marcus [63] | Post-occupancy evaluation (POE), the study of the effectiveness for human users of occupied designed environments, is so named because it is done after an environment has been designed, completed, and occupied. | Effectiveness for users; Human users; Designed and occupied; Environments; After design, completion, and occupation |

| 30 | 2014 | Gebhardt [64] | Post-occupancy evaluations (POEs) are studies that examine completed building projects and evaluate how successful they are in fulfilling the goals of their designers and those who commissioned the buildings. | Examine and evaluate; Completed projects; Building; Successful; Goals of designers and commissioners |

| 31 | 2015 | Tookaloo and Smith [57] | POE is the process of evaluating the building in a systematic and rigorous way after it has been occupied. | Process of evaluating; Building; Systematic and rigorous; After occupied |

| 32 | 2015 | Tookaloo and Smith [57] | Post-occupancy evaluation (POE) is a process of assessing building performance for its users and intended function during occupation. | Process of assessing; Building; Performance; Users; Intended function; During occupation |

| 33 | 2015 | Tookaloo and Smith [57] | POE is the collection and review of occupant satisfaction, space utilization, and resource consumption of a completed constructed facility after occupation to identify key occupant and building performance issues. | Occupant satisfaction, space utilization and resource consumption; Completed constructed; Building; Identify issues; Performance |

| 34 | 2016 | Ozdil [9] | POE is defined simply as the assessment of the performance of physical design elements in a given, in-use facility. (Paraphrased (Preiser et al., 1988, p. 3)) | Performance; Physical design elements; In-use; Assessment |

| 35 | 2017 | Mustafa [52] | POE is the evaluation of the performance of buildings after they have been occupied. | Evaluation; Performance; Buildings; After occupied |

| 36 | 2017 | Mustafa [52] | POE is the process of obtaining feedback on a building’s performance in use. | Building; Performance; After occupied |

| 37 | 2017 | RIBA, Hay, Bradbury, Dixon, Martindale, Samuel and Tait [51] | POE is not just about energy and user satisfaction but can also include more intangible issues such as productivity, identity, atmosphere and community. | Tangible and intangible; Energy, user satisfaction, productivity, identity, atmosphere and community; |

| 38 | 2017 | RIBA, Hay, Bradbury, Dixon, Martindale, Samuel and Tait [51] | Post-occupancy evaluation (POE) is the process of understanding how well a building meets the needs of clients and building occupants. POE provides evidence of a wide range of environmental, social and economic benefits core to sustainability. It can also address complex cultural issues such as identity, atmosphere and belonging. | Process of understanding how well…; Needs of clients and occupants; Building; Provide evidence; Environmental, social, economic and cultural; Sustainability; Identity, atmosphere and belonging |

| 39 | 2018 | Boarin, Besen and Haarhoff [18] | Stevenson and Rijal (2010) have defined the POE framework as the evaluation of quantitative aspects that provide a physical performance baseline and qualitative aspects related to the evaluations of user responses or their behaviour. (Paraphrased (Stevenson & Rijal, 2010, p. 551)) | Quantitative and qualitative; Physical performance baseline; User responses or behaviour; Evaluation |

| 40 | 2018 | Boarin, Besen and Haarhoff [18] | POE is a useful way of confirming the actual performance of the built environment, including quantitative and qualitative data. | Performance; Built environment; Including quantitative and qualitative data; Way of confirming |

| 41 | 2019 | Roberts, Edwards, Hosseini, Mateo-Garcia and Owusu-Manu [7] | To measure a building’s operations and performance, a post-occupancy evaluation (POE) is typically utilised to determine whether decisions made by the design, construction and facilities management professionals have met the envisaged requirements of end-users and the development’s commissioners. | Building; Measure operations and performance; Determine; Decisions made by design, construction, and facilities management professionals; End-users and development’s commissioners |

| 42 | 2019 | Breadsell, Byrne and Morrison [56] | Post-occupancy evaluation is an established method of studying occupants of buildings for feedback and/or through measurements of building performance. | Building; Feedback; Occupants and/or performance; |

| 43 | 2019 | Hosey [19] | Today, POEs vary widely in scope, but generally they focus on two basic questions: Is the building behaving as intended? And are occupants happy with the results? | Vary widely in scope; Intention and users’ satisfaction |

| 44 | 2020 | Bowring [1] | With a clearly normative purpose for critique, Post-Occupancy Evaluation (POE) is an approach which evaluates how a site functions for its users. | Normative purpose; Evaluate; Function; User |

| 45 | n.d. | Watson [65] | Post-Occupancy Evaluation is the architectural process for finding out from all stakeholders about how buildings support productivity and wellbeing. | Building; All stakeholders; Support productivity and wellbeing |

| 46 | n.d. | Therapeutic Landscapes Network [66] | Post-Occupancy Evaluations (POEs) are performed after a project has been built to see whether the space is having the desired outcome. | After built; To see whether; Space; Desired outcome |

Appendix B. Codes Count of the Open Coding of the POE Definitions

Table A2.

Codes Count of the Open Coding of the POE Definitions.

Table A2.

Codes Count of the Open Coding of the POE Definitions.

| Initial Codes | Counts |

|---|---|

| Building | 26 |

| Performance | 14 |

| After occupied | 5 |

| Process of evaluating | 5 |

| Systematic | 5 |

| After built and occupied | 4 |

| Buildings | 4 |

| Occupied | 4 |

| Systematically | 4 |

| User | 4 |

| Assessment | 3 |

| Evaluation | 3 |

| Systematic and rigorous | 3 |

| Actual performance | 2 |

| After built | 2 |

| Built environment | 2 |

| Existing | 2 |

| Explicitly stated criteria | 2 |

| Facility manager | 2 |

| Human users | 2 |

| In use | 2 |

| Act of evaluating | 1 |

| After design, completion and occupation | 1 |

| After use | 1 |

| All stakeholders | 1 |

| Any activity that originates out of an interest in learning performance | 1 |

| Appraisal | 1 |

| Approach to evaluating | 1 |

| Become broader in scope and purpose | 1 |

| Building and facility | 1 |

| Case-study evaluation | 1 |

| Compare actual performance with criteria | 1 |

| Compare with performance criteria | 1 |

| Completed constructed | 1 |

| Completed projects | 1 |

| Comprehensive | 1 |

| Consequences of past design decisions | 1 |

| Consider owners, operators and occupants | 1 |

| Continuously improve facilities | 1 |

| Decisions made by design, construction and facilities management professionals | 1 |

| Degree of meeting user needs and organizational goals | 1 |

| Design | 1 |

| Design decision | 1 |

| Design intent | 1 |

| Designed and occupied | 1 |

| Designed environment | 1 |

| Desired outcome | 1 |

| Determine | 1 |

| Diagnostic tool and system | 1 |

| Differ from post-construction evaluation and technical evaluation | 1 |

| During occupation | 1 |

| Effectiveness | 1 |

| Effectiveness for users | 1 |

| Effectiveness of designed environments | 1 |

| Elements that are overlooked | 1 |

| Elements that work | 1 |

| End-users and development’s commissioners | 1 |

| Energy, user satisfaction, productivity, identity, atmosphere and community | 1 |

| Environmental, social, economic and cultural | 1 |

| Environments | 1 |

| Evaluate | 1 |

| Examination | 1 |

| Examination and research | 1 |

| Examine and evaluate | 1 |

| Explicit and implicit | 1 |

| Facility | 1 |

| Feedback | 1 |

| Fully operational | 1 |

| Function | 1 |

| Goals of designers and commissioners | 1 |

| Hands-on | 1 |

| Human needs, performance and facility management | 1 |

| Ideally, standards and norms are accepted as goals | 1 |

| Identify and evaluate performance | 1 |

| Identify issues | 1 |

| Identity, atmosphere and belonging | 1 |

| In-use | 1 |

| Including quantitative and qualitative data | 1 |

| Intended function | 1 |

| Intention and users’ satisfaction | 1 |

| Landscape architecture and planning | 1 |

| Level of meeting expectation | 1 |

| Maintenance, operation, and design | 1 |

| Manner of evaluating | 1 |

| Measure effectiveness | 1 |

| Measure operations and performance | 1 |

| Monitoring and measuring performance | 1 |

| Needs of clients and occupants | 1 |

| Needs of occupants | 1 |

| Needs, activities, and goals | 1 |

| Needs, perceptions and expectations | 1 |

| Normative purpose | 1 |

| Occupant satisfaction, space utilization and resource consumption | 1 |

| Occupants | 1 |

| Occupants and/or performance | 1 |

| Outdoor space | 1 |

| Owner and user | 1 |

| Perform | 1 |

| Performance criteria | 1 |

| Performance of design | 1 |

| Physical design elements | 1 |

| Physical performance baseline | 1 |

| Positive and negative | 1 |

| Pre-requisite for design phases | 1 |

| Procedure for determining whether or not ... | 1 |

| Process of assessing | 1 |

| Process of comparing actual performance with criteria | 1 |

| Process of understanding how well … | 1 |

| Programmes and procedures for evaluation | 1 |

| Provide architects with information and users with guidelines | 1 |

| Provide evidence | 1 |

| Quality and performance | 1 |

| Quantitative and qualitative | 1 |

| Resource consumption | 1 |

| Rigorous | 1 |

| Satisfies and supports human needs and values | 1 |

| Site use | 1 |

| Space | 1 |

| Specific standards or criteria | 1 |

| Structured | 1 |

| Sub-process of BPE | 1 |

| Successful | 1 |

| Support productivity and wellbeing | 1 |

| Sustainability | 1 |

| Systematic and formal | 1 |

| Systematically and rigorously | 1 |

| Tangible and intangible | 1 |

| Technological and anthropological elements | 1 |

| To see whether | 1 |

| Tool of BPE | 1 |

| User responses or behaviour | 1 |