Abstract

The urban scenarios outlined by the environmental and economic crisis have fostered, on one hand, the unstoppable gentrification of the most central neighborhoods of the cities; and on the other hand, a growing associationism committed to cultural and environmental values, which demands tools from academia to negotiate with the administration. An emblematic case is that of Arganzuela, one of the three districts of the Spanish capital affected by the rise and fall of industrialization (the freight railway in 1861 and the M-30 ring road in 1970). The burying of these infrastructures began in 1990 with the Green Railway Corridor (PVF) operation, a year after the inauguration in Paris of the Promenade Plantée on the disused railway lands, which allows us to foreshadow new scenarios. The TRAHERE project researches the state of abandonment and disaffection of the public spaces of the PVF using social networks as a connection platform with participatory channels to promote its regeneration. The challenge is to convert the concept of transfer of results into a more inclusive one of knowledge exchange, which implies a methodological change in research, with an integrating perspective that combines urban historical studies with artistic practices of production and postproduction for the dissemination of content on the networks.

1. Introduction

The TRAHERE project is part of a little-explored line of landscape and urban studies that address documentary and historical research from a contemporary perspective with a clear vocation to become forums for citizen debate around the topics studied. As a national precedent, we point out “Aqueous Madrid”, a documentary and artistic research that considers the emotional reconnection of the city of Madrid with its watery past [1]. A space for reflection and debate was curated by Malú Cayetano Molina in collaboration with the International Biological Station DueroDouro’s “Water Project” [2]. Both projects share the aspiration to combine the exactitude and depth of scientific and urban historical studies with an artistic perspective, the consequence of a transversal approach, and a careful postproduction process of the results in order to provide emotional experiences that can be shared by citizens. In short, they seek to provide the didactic contents with an aesthetic, contemplative, and operational dimension at the same time.

As a starting point we ask ourselves:

Can the use of digital technology and social networks promote a process of reappropriation based on a shared knowledge of the urban landscape and its transformations? If that is the case, how can we carry it out from the universities?

If the concept of transfers of results entails “the dissemination of the results for their implementation in society through professional practice” [3], the exchange of knowledge through social networks implies an open attitude toward a shared knowledge within the reach of all citizens. In this sense, a change of attitude is proposed here that, in methodological terms, introduces the postproduction of results as a step after production and prior to dissemination through academic channels and social networks. Thus, a predominantly artistic practice is introduced into academic research. In fact, if the term “production” is synonymous with creation, elaboration, and original composition through the use of raw materials (from the Latin producere, in turn from ducere, meaning to drive toward something in particular), the concept of “postproduction” arose in 1989 in the digital culture as a set of operations that include dubbing, editing, mixing, and the eventual digital elaboration of sequences with special effects of videos, photos, or music tracks that precede the staging and/or marketing phase [4] (p. 2094).

The theoretical and conceptual framework is offered to us in this sense by the French historian and art critic Nicolás Bourriaud, who has theorized about this practice. According to Bourriaud, the contemporary creator acts as a disc jockey: rather than generating or composing new forms, he reprograms and combines those that already exist based on his information [5] (p. 25).

In this theoretical context, the objectives are, at a general level:

- Encourage a more democratic conservation of the landscape.

- Foster, at an academic level, a more democratic and open conception of research in the field of landscape.

At a specific level:

- To claim the care of the public space and its heritage, thereby promoting its knowledge in line with a new sensibility.

- To apply historical and heritage knowledge to more open and participatory social contexts through the use of storytelling techniques and the postproduction of results.

- Indicate strategies for the revitalization and enhancement of the public space by establishing physical, virtual, and cultural networks through social media.

Therefore, we are trying to give a contemporary response to the complexity of the contemporary landscape to an increasing presence of neighborhood associations in the political life of cities.

Our case study, the Pasillo Verde Ferroviario de Madrid (PVF), meets the requirements of a public space in a state of abandonment with a strong presence of neighborhood associations and that is very active on the social networks, which they use to share knowledge about the urban landscape and to call for actions for its improvement and conservation. Despite being the largest urban development operation carried out in the capital before Madrid Río, the residents of the area, and more generally of the city of Madrid, hardly know its history. Citizens have discovered their public spaces during the pandemic, when vegetation has taken over the city with an explosion of wild flora, especially around the tracks and monumental stations of Príncipe Pío and Delicias, which are located at the opposite ends of the area (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

State of abandonment of the public space of the PVF: (a) surroundings of the Delicias station; (b) wild flora on the roads. Photos by Ramón Gómez of Herba Nova for the TRAHERE project.

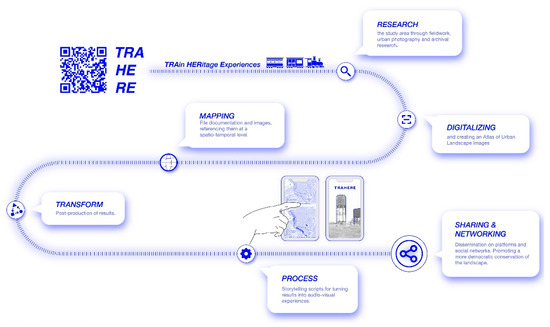

These starting conditions allow us to apply and validate our methodology through a study and rigorous analysis of the area and through a proposal for the future linked both to the river and to the postproduction of the results, which will in turn be disseminated to and exchanged with the public and the institutions through social networks. In this way, the aim is to turn the TRAHERE project into an operational tool for exchanging knowledge focused on the shared care of the urban landscape, which entails a change in the methodology of the research, as will be explained later (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Initial objectives. Source: TRAHERE’s own elaboration.

We have chosen as an acronym of our project the word TRAHERE (TRAin HERitage Experiences) because it is a Latin verb from which derives, through the Norman and by successive adaptations, the word (French first and English later) train. From trahere (drag) derives the vulgar traginare, in Old French (Middle English) trahiner (push something), and from this the noun to which we refer, train, used in both French and English. TRAHERE could also be summarized as TRAin HEritage REuse, thereby emphasizing the concept of reuse as a postproduction process in which unused materials find, with few means and without the need for specialized intervention, a new life [6].

2. Case Study

2.1. Status of the Issue on the Area of Study

Studying the PVF means analyzing and measuring in qualitative and qualitative terms the impact of the irruption, rise, and decline of industrialization in the city of Madrid—an arc of two centuries whose analysis has allowed us to verify that in the case of the PVF, the relation between the generation of public spaces and the defense and care of the industrial landscape and its heritage is not entirely balanced.

The specific bibliography on the Green Railway Corridor is brief. The most relevant is formed by the publications of the Urban Consortium itself [7] and the subsequent ones of its technical director, Alfonso García Santos, who has detailed in several articles the experience of management and technical materialization of the operation [8]. There are brief useful reviews such as those from the guides of the Madrid City Council, in particular the one published in 2016 and coordinated by Ramón López de Lucio, Álvaro Ardura, José Javier Bataller, and Javier Tejera [9] (pp. 44–47); and the 2014 guide of the Historical Service of the Official College of Architects of Madrid (COAM) [10]. Both publications clarify, in a summarized way, the responsibilities, main legal procedures, phases, and results of the project. An important contribution is the study published in 1995 by geographers Dolores Brandis and María Isabel del Río, in which the repercussions of the project management and the successive modifications in buildability and uses in the affected area are explained in depth [11] (pp. 113–128).

Among the technical reports, we point out the evaluation of the Green Railway Corridor carried out by Testing Consulting in 2003 for the Ministry of Planning and Cooperation (MIDEPLAN) of Chile as an example of management along with seven other international case studies such as Puerto Madero (Buenos Aires, Argentina), San Diego Downtown (CA, USA), Paris Rive Gauche (Paris, France), and London Docklands (London, UK). The document is accessible through the digital library of the Inter-ministerial Office for Transport Planning (SECTRA). It thoroughly analyzes the management and financing model of the operation on the basis of data largely provided by the Urban Development Consortium [12].

The recently published book The Urbanism of Transition: The Master Plan of Madrid 1985 by Carlos Sambricio and Paloma Ramos provides data and reflections of interest on aspects related to the PVF [13].

An important book to help understand the grounds of the operation is Madrid Proyecto Madrid 1983–1987, which collected the activity developed by the Municipal Management during the years indicated in the title and was based on a series of operations that laid the foundations of the Green Railway Corridor a few years before [14].

The original documentation of the Green Railway Corridor is distributed among multiple files. All the monthly reports of the Technical Assistance to the Works of the Green Railway Corridor of Madrid are kept in the deposit of the library of the Technical School of Civil Engineers of the Polytechnic University of Madrid donated by Alfonso García Santos, who informed us of its existence and location. It is a set of approximately 200 volumes (from the end of 1989, when the operation started, until the end of 1996) with detailed technical information that is especially related to the railway infrastructure. The bulk of the photographic, graphic, and documentary documentation is kept in the Regional Archive of the Community of Madrid (ARCM) and is organized in five volumes related to the five sections in which the operation was structured (A-B-C-D-E). The documentation relating to the new interchangers is kept in the General Archive of the Administration of Alcalá de Henares (AGA). The Museum of Science and Technology (MUNCYT) preserves documentation relating to the multiple files and projects for restructuring the Delicias station and its surroundings into the museum [15] (p. 153).

2.2. The Green Railway Corridor (PVF) Hypothesis and Objectives

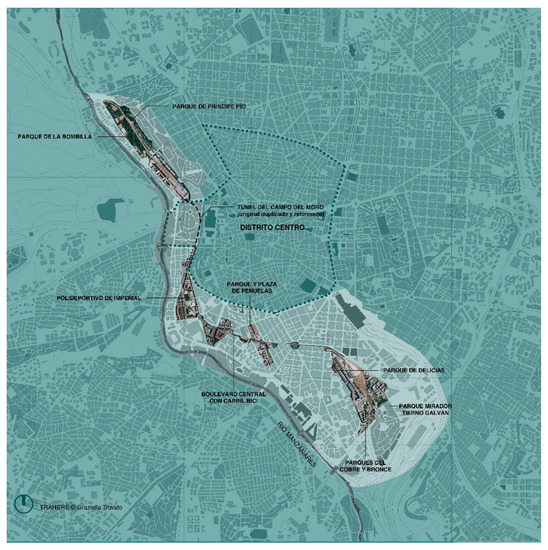

The PVF was carried out between 1989 and 1996 through the 1st Modification of the General Plan with the creation of an Urban Consortium formed by representatives of the National Network of Spanish Railways (RENFE) and the City Council. The work involved the regeneration of an urban corridor of 8 km in length between Puente de los Franceses in the Moncloa district and the Delicias station in Cerro de la Plata. In other words, it was a radical transformation of the northwest–southeast arc of the capital parallel to the Manzanares River (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The PVF and the scope of action between the Central District of the capital and the Manzanares River. The parks of Príncipe Pío, Bombilla, Peñuelas, Delicias, Mirador de Tierno Galván, Cobre, and Bronce stand out, as well as the central boulevard with a bike lane. Source: TRAHERE’s own elaboration.

The burial of the railway route was, in fact, the opportunity for the regeneration of a portion of the city that occupies 163 Ha in the districts of Moncloa-Aravaca, Centro (although tangentially), and Arganzuela. The area gained urban parks, intermediate spaces between landscaped blocks, bike lanes, a central boulevard, and non-residential buildings at no cost to the municipality. The cost in terms of industrial heritage, however, has been high: many factories disappeared, some of them of architectural, typological, and cultural interest; several buildings were reused without much sensitivity; and there is scarce tangible railway heritage left that is basically limited to the Delicias station, which was converted into the Railway Museum and the National Science and Technology Museum. In the case of the Príncipe Pío station, it is safe to say that it has been mistreated in many ways, both in the treatment of its surroundings and in a series of extensions unrelated to its initial use that have trivialized and altered the legibility of the original station.

It was the consequence of the decline of the industrial fabric and the obsolete character of the 19th-century single-track railway contour line that was intended for the transport of goods. The process began at the Planning Office of the Municipal Management in a climate of strongly politicized democratic construction. The burial of the railway route, in fact, was the opportunity for fairer growth that was in line with planning aimed at balancing the differences between a northern area of a privileged Madrid and a depressed and underdeveloped working-class south. In addition, the city discovered the difficulties of continuing to grow to the north according to the guidelines of the Zuazo-Jansen plan of 1929 due to, among other things, the existence of the neighborhoods of Fuencarral and Hortaleza. This highlighted the development opportunities of a wide swath of the city already immersed in a transformation phase and with abandoned plots and empty interstitial areas due to the decline of the industrial sector. The possibility of designing and shaping a new city with public parks, non-residential areas, and housing was foreshadowed in a new development in the southwest of the capital [16] (pp. 43–46).

It was a question of modernizing the transport network via the execution of a modern Network of Suburban and Metro Interchanges and at the same time regenerating the public space as derived from the restructuring of the disused railway fabric.

The residents of Arganzuela, one of the three districts affected by the operation and in turn composed of five neighborhoods of the capital, were responsible for the movement to demand the burial of the rails, which crossed our study area on the surface and frequently caused accidents [13] (pp. 250–255). This associative system was reactivated in 2002 to claim a public use of the old Municipal Slaughterhouse and achieved its conversion into a Cultural Center against the planned privatization, and finally in 2011, as a result of Operation Madrid Río, which is tangent to the one we are now dealing with, to defend the district from a growing gentrification [17] (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Activism of neighborhood associations of Madrid after the Democratic Transition. (a) First protest of the neighborhood associations of Madrid in 1977 (Archivos de la Transición [18]); (b) an example of the presence of neighborhood associations on social networks: the current profile of the Pasillo Verde Imperial Association on Twitter.

However, since the PVF ended in 1996, it has remained in a state of total abandonment. Despite the beneficial effects of the operation, it was not publicized, probably as a result of a zero-cost financing model, which forced the disused land to be rezoned on several occasions to increase buildability and consequently its profitability. We found an urban landscape in a state of degradation due to lack of maintenance and unknown to a large part of the citizens. Publications, as we said, are scarce, and almost entirely driven by their own creators.

We ask ourselves: what are the causes of this ignorance and lack of care?

As a starting point we find:

- Loss of Industrial Memory and Disaffection.

The PVF today lacks a recognizable identity. In general, the set of railway facilities will be seriously compromised if the PVF chooses to replace the heritage landmarks with, according to the testimony of the then director of the Consortium, Manuel Ayllón, a symbolic framework of Masonic origin whose meaning is ignored by citizens and is not related to the city and its memory [7] (pp. 10–14). The structuring elements and landmarks of the PVF have a monumental character not related to the historical memory of the city, although fragments of its railway past appear occasionally that are disconnected from its original fabric and meaning. They are seen as solitary elements that are indifferent to the urban fabric and its inhabitants. All this led us to relate, in an initial hypothesis, the loss of neighborhood memory to disaffection.

- The Loss of Connection between the Green Railway Corridor and the River.

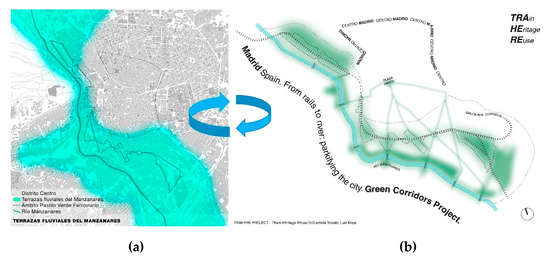

The PVF never sought a connection with the river despite being settled precisely on its old river terraces. In fact, “Terrazas del Manzanares” was the name given in the early 19th century to the archaeological area located on the old bank of the river at an approximate height of 600 m above sea level between El Pardo and Getafe. This area, which affects the entire Railway Green Corridor, was the first settlement in Madrid and has been logically close to the waters of the river since the Paleolithic, as evidenced by the discoveries preserved in the Madrid-based Museum of San Isidro and other samples in the Museum of History of the capital. The burial of the M-30 with Madrid Río in the first decade of the XXI century and the newly opened Plaza de España today allow us to imagine new scenarios for the future: an urban continuum that connects the Green Railway Corridor with the banks of the river through sustainable mobility and a greater biodiversity. Between the river and rails is, in short, a proposal for an integrated return to the river in a desirable circularity (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Two diagrams that synthesize the circularity proposal. (a) The scope of the PVF in the old fluvial terraces of the river. The following are distinguished: the downtown district, the area of the PVF, and that of the old terraces. (b) The proposal for the connection project between the PVF and Madrid Río “Towards a desirable circularity”. Source: TRAHERE’s own elaboration.

3. Materials and Methods, “Postproduction” vs. “Transfer”, and Academia in a Process of Change

As has been explained, we distinguished in the research process between the “production” of results and the “postproduction” of them. The first focused on the transfer of results (book, book chapter, conference papers, and scientific articles) and the second on what we understand as dissemination and exchange of knowledge through digital platforms, physical and virtual networks and presence in public spaces. Both phases alternate and overlap so that production and postproduction of results are understood in a relationship of constant and mutual feeding.

In both phases the approach must be, in our opinion, holistic, transversal, and integrative. To achieve this, the first step is the formation of an interdisciplinary team with the ability to combine humanities with sciences and the digital world, as well as a quantitative analysis with a qualitative one, in functional, aesthetic, and patrimonial terms. A team composed of an architect (Graziella Trovato, main researcher), an urban planner (Luis Moya), a heritage manager (Melín Nava, granted for this project by the Carolina Foundation), urban photographers (Davide Curatola Soprana and Ramón Gómez; the latter specializes in wild flora and railway botany), and a digital design team (Diego Iglesias and Cristóbal Baños from Hyper Studio). The GIPC architects and researchers (Clara Álvarez García, Isabel Rodríguez de la Rosa, and Beatriz Salido) have also collaborated in graphic and audiovisual production as well as in data editing and documentary research. The Pasillo Verde Imperial Neighborhood Association, the largest of those present in the area, has also been involved, especially in fieldwork and the location of disused buildings for their possible transformation for public use.

3.1. Production of Results: Materials and Methods

As a basis for the landscape and urban analysis, the materials used in the first phase of production of results were:

- The General Plans: from the Castro Plan of 1860 until today, including the various modifications of the General Plan of 1985 with which the PVF was carried out. This documentation, which is kept in the Regional Archive, was unpublished because the modifications, with the exception of the first, responded to the need to rezone the soil in order to make bigger profits.

- Historical cartography: 15 plans in total that included land register and topographic plans and others related to plots of land from the years 1622 to 2020. In addition, it includes four orthophotos from 1975, 1991, 1999, and 2020. These documents were selected based on the degree of information provided to measure the impact of industrialization in the study area.

- A total of 850 documents that included various documentation from public and private archives; photo libraries; newspaper archives; and municipal, regional, and state libraries. They included unpublished and/or unreferenced documentation such as the original plans of the railway contour line project of 1861 as well as other materials that documented the creation and consolidation of the PVF in the 1990s.

- Material obtained from fieldwork carried out throughout the research process. As we stated previously, part of this process was carried out with the Pasillo Verde Imperial Association via actions organized through its social networks (mainly Twitter and Instagram) (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Fieldwork in the PVF. Action organized by the Pasillo Verde Imperial Association in the Parque del Gasómetro via Twitter. It reads: “We walked the #parquedelachimenea with the urban planning architects Luis Moya and Graziella Trovato @ETSAMadrid @La_UPM, with extensive experience designing urban parks, to assess recent actions #fencing and possible improvements #urbanregeneration #Arganzuela #Homeless”.

Figure 6. Fieldwork in the PVF. Action organized by the Pasillo Verde Imperial Association in the Parque del Gasómetro via Twitter. It reads: “We walked the #parquedelachimenea with the urban planning architects Luis Moya and Graziella Trovato @ETSAMadrid @La_UPM, with extensive experience designing urban parks, to assess recent actions #fencing and possible improvements #urbanregeneration #Arganzuela #Homeless”.

On this basis and with the use of graphic design programs (mostly InDesign, AutoCAD, and Photoshop), the method consisted of:

- Developing different location diagrams of the study area accompanied by quantitative data on the of the operation in its entirety and the balances related to the area occupied by the railway and industrial heritage, housing, and public and non-residential spaces before and after the PVF.

- Tracing the evolution according to the stages of the area from its origins (river terraces) to the irruption of the railway (1861), the construction of the M-30 ring road (1970), the burial of the railway (PVF 1990), and the burial of the M-30 (Madrid Río 2011).

- Mapping the documentation of archives and locating and indexing it to historical plans and orthophotos. This allowed a spatio-temporal reading of the PVF understood as a cultural landscape and the measurement from the quantitative point of view of the heritage by identifying and differentiating between what has disappeared and what has been transformed through reuse operations.

- Photographing the public spaces and historical landmarks of the PVF and its area of influence. To the urban signature photography (Davide Curatola Soprana), we conferred an operative role in the critical sense that Zevi attributes to this word; that is to say, propositional (for the quantitative and qualitative analysis of the operation) and at the same time contemplative. At a general level, we tried to capture and interpret the complex transformation phenomena that affect the Green Railway Corridor today, which we understand to be extensible to other areas of similar characteristics. These processes can be either natural or man-made in public policies and citizenship. In their interpretation, we understood that there was, in part, a solution: to indicate paths that point toward new and different singularities (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Image by Davide Curatola Soprana from Urban Reports for TRAHERE. It intends to show the state of abandonment, squatting, and (at the same time) the potential of this urban space.

Figure 7. Image by Davide Curatola Soprana from Urban Reports for TRAHERE. It intends to show the state of abandonment, squatting, and (at the same time) the potential of this urban space.

- Cataloguing the wild flora and railway botany in 142 files corresponding to the species registered during the pandemic in a time arc of 5 months. Spontaneous species have been one of the main protagonists of public spaces since the pandemic. The lack of maintenance due to COVID-19, in the case of the PVF, must be added to years of neglect by the administration. Far from constituting a threat to our environment, these species are a source of environmental wealth and biodiversity. Moreover, as the photos of the botanist Ramón Gómez show, they are beautiful and have a great richness of shapes and colors. The cataloguing includes data on the origin of the species, habitat, and ethnobotany, thus favoring the construction of multiple stories and tales. Gómez makes it clear: there are no bad species, and they all contribute to biodiversity. In our specific case, the railway corridors help channel biodiversity and, as demonstrated in this study, the largest number of species (with two of them on the path to extinction) have been registered around the stations of Delicias and Príncipe Pío and the remaining tracks on the surface. This allowed us to defend the protection of these areas as urban forests for public use at the height of a neighborhood protest calling for the temporary cession by ADIF on the land between the aforementioned Delicias station and the Regional Archive (the former El Águila Brewery) of the development of a privately managed leisure center.

- Interviewing the main actors of the operation, including urban technicians, engineers, and neighbors. The interviews were decisive for the research and highlighted the contributions of representatives of the Neighborhood Association with their testimony regarding the transformation of the neighborhood. Due to the pandemic, some of the interviews were conducted via Zoom, which allowed us to record without added costs and share previously selected graphic documentation on screen that enriched the discourse regarding heritage in the final video.

- Preparing, in a second phase, an Inventory and an Atlas of Heritage that included what still exists and what has disappeared as well as what is in use and/or reused. For its development, we considered the Green Corridor within a larger “area of influence” between the current boulevards (in the route of the old Cerca de Felipe IV) and the river. The methodology consisted of:

- Creating an inventory of 170 heritage elements in the corresponding files. Each of them included an image of the building that allowed it to be identified, the design authorship in the different phases and eventual modifications, and the list of uses and properties from a chronological perspective. There are 70 buildings that have maintained their original use while 44 have disappeared, of which 10% disappeared in the period in which the research was carried out (2019–2022). Additionally, three large groups were found in a state of abandonment, the most prominent being the former Museum of Military Pharmacy, which could be considered as the headquarters of the Arganzuela Neighborhood Space (EVA), which was recently evicted from the old Fruit and Vegetable Market near the Municipal Slaughterhouse by the current government.

- Sequencing heritage elements in an Atlas presented as a visual journey through the city “between river and rails”. This created a spatio-temporal sequence through the area (both diachronic and synchronic) that was organized in the three sections in which the entire analysis of the operation was structured (Puente de los Franceses-Imperial, Imperial-Peñuelas, and Peñuelas-Delicias-Cerro de la Plata). The Atlas consists of 177 images from the archives that are alternated with contemporary photographs.

- Finally, we considered as part of the methodology the elaboration of a proposal for the future from the viewpoint of circularity and biodiversity to connect the PVF with Madrid Río: a proposal of return integrated to the Manzanares in a desirable circularity.

3.2. Postproduction of Results: Materials and Methods

The postproduction phase consisted of transforming the contents and documentation described above into an audiovisual format. It must be taken into account that if the world of theoretical production is linear, rigorous, organized, slow, distant, and timeless, digital postproduction is multiple, selective, fast, and constantly changing.

The phases of the process can be summarized as:

- Development of narrative scripts (storytelling) aimed at an audience not necessarily specialized but interested in understanding the city of Madrid, the transformations of its urban landscape, its potential, and its possibilities for future development.

- Selection of materials and techniques to transform the guides into different experiences of the study area (collages and 3D animations) by preparing virtual tours and augmented experiences that added temporalities to the physical space.

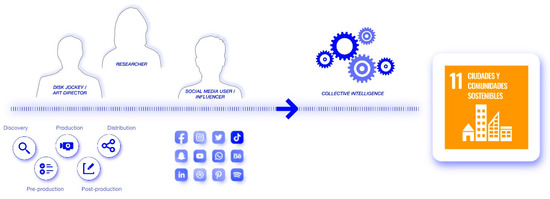

- Selection of physical and virtual platforms and appropriate social networks to share these experiences and improve results (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Conceptual diagram of the research method in which the postproduction work was combined with a presence on social networks. The purpose was collective intelligence and ultimately the Sustainable Development Goal 11, which refers to cities, within the 2030 Agenda. Source: TRAHERE’s own elaboration.

Figure 8. Conceptual diagram of the research method in which the postproduction work was combined with a presence on social networks. The purpose was collective intelligence and ultimately the Sustainable Development Goal 11, which refers to cities, within the 2030 Agenda. Source: TRAHERE’s own elaboration.

4. Results

The storytelling scripts were outlined in the transformation of the material produced into audiovisual content in MP4 video format of variable durations and resolutions that ranged between 3 and 12 min and 720p and 1080p, respectively, depending on the destination network and whether it was recorded face-to-face or through a virtual platform. We highlight five derivative scripts in five results described below:

- The first virtual trip developed was a flight through the study area. It was a 3D animation made using Google Earth that covered an itinerary between Puente de los Franceses and Atocha. It was accompanied by indications related to the urban landmarks of the PVF and its urban spaces and by sounds of the urban environment (birds, tree leaves, and walkers) and the commuter train that currently runs through the area next to the metro that was previously registered.

- The second trip, which was of a documentary nature, was structured in three blocks:

- Background: rise and fall of the industrial fabric.

- The green railway corridor: the project, the works.

- Future prospects.

The tour immerses the viewer in the river terraces of the Manzanares: sequences of images and selected shots of the riverbed alternate with the previously elaborated graphic documentation to lay the foundation of the project proposal: if these were the terraces of the river, now they have to go back the way they were. In the background, the sound of the waters of the Manzanares and the birds that populate the area can be heard.

- The third trip, made by Curatola Soprana with sequences of images and shots taken in different areas of the PVF, portrays daily life through its inhabitants.

- The fourth journey, which is elaborated from the Atlas, is a space–time journey through the area. It shows the transformations of the urban landscape and its heritage landmarks. The sound was edited on the basis of the nostalgic theme “Just (After Song of Songs)” composed and performed by David Lang for the soundtrack of Paolo Sorrentino’s Youth (2016). It is a song to lost loved ones that was used in reference to the demolished or abused heritage.

- The fifth trip, which is presented as a sensory and contemplative experience, was organized from the photographs of Ramón Gómez as a sequence of images of the plots occupied by the wild flora that alternates general shots with others of details of plants and flowers between rails, sidewalks, and pipelines.

- The sixth trip, “Between river and rails”, consists of the design and curatorship of the exhibition currently installed in CentroCentro, Cultural Center and Exhibition Hall of the City of Madrid, housed at the Palacio de Cibeles [19] (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

The exhibition “Between river and rails” announced and commented upon on LinkedIn by José María Ezquiaga, Head of Urban Planning of the Municipal Management in the 1980s and one of the first promoters of the PVF who today is an expert on urban planning.

For the dissemination of results, a TRAHERE YouTube channel was created and linked to the project website to seek the interconnection between the academic platform and the digital channels and networks using a QR code and a project profile on Instagram (username: entre_río_y_ra-iles.trahere).

The interviews conducted with the different actors involved in the PVF operation as well as those with international experts and representatives of neighborhood associations were edited, published on the TRAHERE YouTube channel, and referenced to the project website [20].

All of the documentation prepared was shared with the neighborhood associations that, in addition to collaborating in the previous phases as explained above, participated in various acts of the dissemination of the results. This included sharing the presentation of the book at the Ateneo de Madrid and the inauguration of the exhibition in CentroCentro mainly through their Twitter channel (PasilloVerdeImperial: @AVVerdeImperial), as well as materials and ideas: “if these used to be the terraces of the river, they must be so again” (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

The presentation of the book Madrid, Between River and Rails [19] through a Twitter thread of the Neighborhood Association. The images show a projection screen with the PVF study area, analysis, and proposals. The neighbors shared and made the information and the objectives of the research their own. The tweets read: “ ‘If these are the #ManzanaresTerraces, they must be so again’ Graziella Trovato @ETSAMadrid #PasilloVerde” and “ ‘The #PasilloVerde, a great unknown, gained space for housing, but destroyed the #industrialheritage of which very little remains’ Graziella Trovato @ETSAMadrid”.

Through the exhibition, the TRAHERE project is present on the social networks of the Madrid City Council (CentroCentro), including Twitter (15,400 followers), Instagram (22,900 followers), and Flickr, where a complete photographic report of the room is available [21] (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Image sequences of the exhibition “Between river and rails” on the Flickr profile of CentroCentro, an exhibition hall and cultural center of the Madrid City Council, at its headquarters in Plaza de Cibeles. Its curation was the result of a process of storytelling and postproduction of the results of the TRAHERE research.

All of the videos were uploaded to a YouTube channel specifically created by CentroCentro for the exhibition and shared through the aforementioned page, where it is also possible to download the brochure.

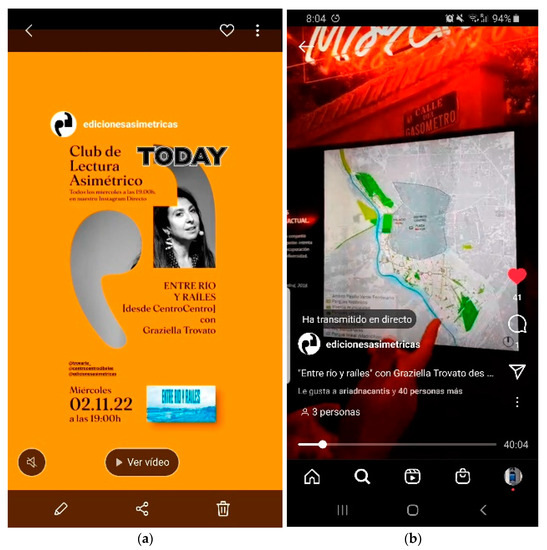

In addition to organizing face-to-face visits to the exhibition, there was a live one-hour presentation on Instagram within the Asymmetric Reading Club directed by María Fernández and Juan García Millán that included a tour and description of the different sections that composed it and all of its material (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

One-hour Instagram Live guided tour showing all the results and including the videos. (a) The banner; (b) an image of a moment of the video documentary “Las terrazas del Manzanares”.

The video, which can be downloaded through this social network on the Asymmetric Editions profile, has so far registered 428 visits [22].

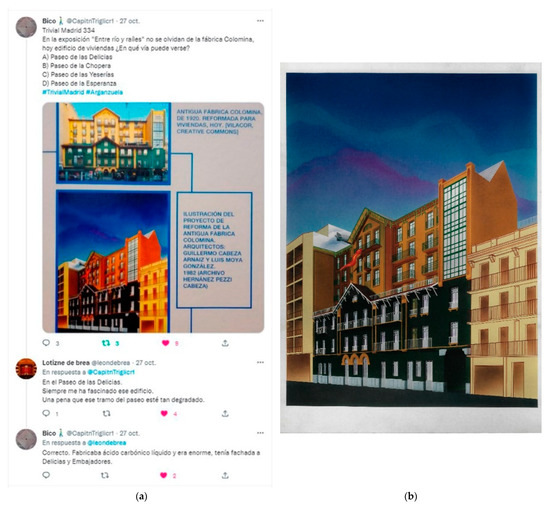

The project has been shared on social networks by citizens. For some, it offers an opportunity to reflect on the city’s past and its transformations with a certain nostalgia for its lost heritage. Sometimes it is carried out through play: this is the case of Bico, who poses riddles about singular patrimonial elements little known by the public. In his tweets, he provides data related to his recollections. In this instance, he shared one of the panels from the exhibition “Between the river and rails” with images of the old Colomina factory on Paseo de las Delicias that was transformed into a residential building in 1982 by Luis Moya and Guillermo Cabeza [23]. Bico specifies that Colomina manufactured liquid carbonic acid and was huge, facing two streets (Delicias and Embajadores) (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Twitter thread with a photo of a panel from the “Between river and rails” exhibition with a riddle about the Colomina factory. Here, Bico shares his memories and presents new information about the building before the remodeling. (a) Twitter thread; (b) project of Moya and Cabeza from 1982.

For others, it is an occasion for critical debate as one of the topics on how the models for financing and management of public space can influence its conservation or abandonment (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Twitter thread by the Asociación Pasillo Verde Imperial that included photos of neighbors visiting the exhibition. A debate was generated around the “zero cost” management model and the state of abandonment. Two neighbors indicated the photo of the authorities in the presentation of the PVF model. Among the comments can be read the following: Naranch replying to @madridete: “The exhibition is very top. It captures very well the transformation of the downtown industrial belt +ffcc into urban fabric. And how in this case, brick prevailed over ’green’. Similar processes took place in Barcelona, Valencia or Bilbao.”; Antonio Rguaz: “It is curious to see in the brochures of the time how they boasted that the operation did not cost the public treasury anything. Well, it did cost the transfer of a lot of land to build flats. An operation that Tierno (Enrique Tierno Galván) began to develop and that Manzano ended. No wonder it ended up degrading.”.

5. Discussion

Fernando de Terán argued: “It is a very interesting and singularly satisfactory part of the not always pleasant history of modern urbanism which refers to the way in which the conceptual understanding of the action on the urban reality has been built (and the legal attention and social valuation derived from it) to protect, defend and care for what has been generically called cultural heritage. Until reaching the current situation, in which the idea itself has widened, evolving and transforming from a mainly objectual perspective to another that is fundamentally environmental, which implies and incorporates notions that come from ecology and an attention to the environment and leads to an intention of general protection of biodiversity. All of which configures a much broader and integrative understanding, which in reality supposes a certain redefinition of the conditions of human intervention on the existing, including of course and in the first place the inherited city” [15] (p. 8).

In our case, the study of the PVF gave us the opportunity to study and suggest a proposal for the future of an area equipped with a strong associative fabric that, approximately three decades ago, promoted a process of reuse of railway heritage that we continue to debate today.

In the final phase of the research, a discussion forum was established with international experts who endorsed our initial hypotheses and method of study and pointed toward the process of reuse as the future of urban and architectural heritage to respond to the crisis of resources in which we live. We cite, among the cases analyzed for their analogy with our case study, the Paris Rive Gauche (France) and The Seven Railway Scales of Milan 2030 (Italy), which is predicted to be one of the largest urban regeneration operations of the next decade [15] (pp. 230–270). Both reuse and recyclage are concepts that emerged, in fact, in the middle of the energy crisis in the 1970s as an expression of the need to curb the consumerist euphoria of the good life and promote the saving of natural resources. Reuse, in addition, is in itself participatory because, unlike restoration and other intervention techniques in heritage areas, it implies forms of appropriation that do not require technical specialization. Our era manufactures objects of all scales with a vocation of precariousness and temporality from a perspective of pure consumerism at the economic level and opportunism at the political level. This inevitably affects our immediate surroundings, our desks, our houses, our buildings, and our public spaces. Nowadays, thinking in terms of reuse, in our opinion, is better defined as an act that comes from a broader awareness of postproduction and inclusion rather than recycling. The prefix “post-”, Bourriaud reminds us, does not indicate a conceptual overcoming but a zone of activity and an attitude [5].

The urgency of this change is evident, and the continuous aggressions toward the urban landscape confirm it. The TRAHERE project aspires, with its presence in public spaces such as CentroCentro and the social networks, to contribute to this change.

6. Conclusions

This research project aimed to discuss the postproduction of the urban environment through a process of the postproduction of academic results for their conversion into a forum for urban debate.

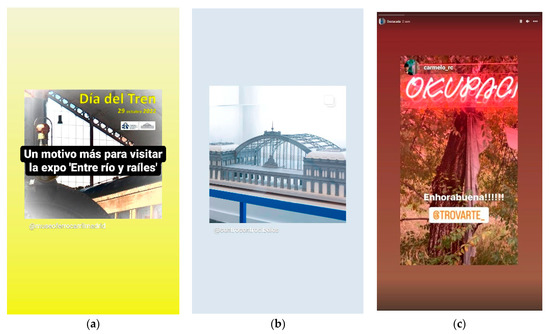

Converting the concept of the transfer of results into that of knowledge exchange implies, as we stated previously, a new approach to research. The digital age has imposed a paradigm shift in which any barrier between the theorist (the researcher/narrator) and their “spectator” has been erased. The critical distance imposed by the book as a physical object is blurred in the “copy-paste” world of networks where everything is shared and commented on and thus transformed. Hypertext, as McLuhan already warned us, resembles the pre-alphabetic oral world where stories were enriched by new stories and characters in their journeys from town to town [24]. Beyond the problems of regulation and control of copyrights that all this poses, as well as the future implementation of blockchain systems to defend institutional rights, the academic world faces new challenges that at the same time involve the possibility of turning scientific research into shared knowledge that is available to all citizens. After the publication of the book Madrid, Between River and Rails. Past, Present and Future of the Railway Green Corridor [15], the first result of the research, both the materials and the inspiring ideas of this project have been shared in physical (Madrid City Council) and virtual (Twitter, Instagram and other mentioned networks) forums of neighborhood associations and institutions (in addition to the City Council and the Spanish Association of Landscape Architects, we mention the Railway Museum, among others) apart from citizens who warn of modifications and changes and interact with the contents of the research (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Presence of the research on Instagram through: (a) the profiles of the Railway Museum of the Spanish Railways Foundation (FFE); (b) the Madrid City Council; and (c) a citizen (the prominent architect and activist Carmelo Rodríguez, founder of Enorme Estudio).

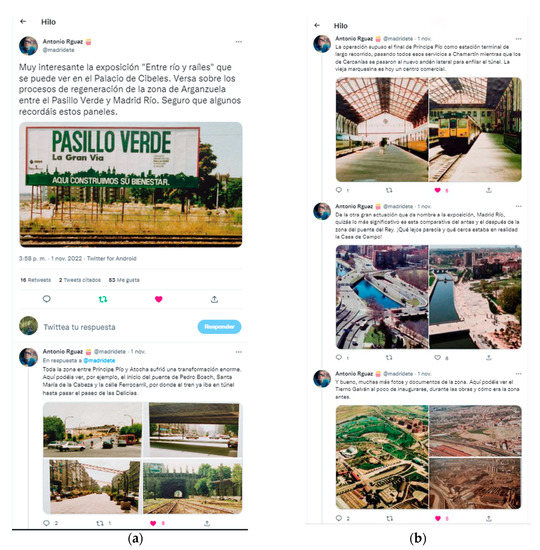

All these stories in their various formats encourage new areas for reflection and debate on the conservation of the urban landscape. In addition, they open up new avenues for analyzing the current and future presence of academic research on social networks through postproduction processes and the dissemination of results. Their tweets and comments become part of the story and create new fields of reflection and avenues for research (Figure 16).

Figure 16.

(a,b) Twitter thread from a citizen who made the story about the PVF his own and enriched it with his memories. (a) It reads: “The Exhibition Between River and Rails that can be seen in the Palacio de Cibeles is very interesting. It deals with the regeneration processes of the Arganzuela area between the Green corridor and Madrid Río. Surely some of you remember these panels” (…) “The whole area underwent a huge transformation. Here you can see, for example, the beginning of Pedro Bosch, Santa María de la Cabeza and Ferrocarril street, where the train used to go underneath a tunnel until it passed Paseo de las Delicias”.

Funding

This work was supported by the Madrid Government (Comunidad de Madrid-Spain) under the Multiannual Agreement with Universidad Politécnica de Madrid in the line Excellence Programme for University Professors and in the context of the V PRICIT (Regional Programme of Research and Technological Innovation) and by the project LABPA-CM: CONTEMPORARY CRITERIA, METHODS AND TECHNIQUES FOR LANDSCAPE KNOWLEDGE AND CONSERVATION (H2019/HUM5692), funded by the European Social Fund and the Madrid regional government.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The project presented was based on the results of a line of research on which we have been working for years in collaboration with the Cultural Landscape Research Group (GIPC). We highlight in particular the participation in the recently completed research project, “The railway and the city at the crossroads: Urban landscape and industrial heritage in the surroundings of the stations of the Iberian Peninsula, 1850–2017. Digital Station” (main researcher Jordi Martí Henneberg) funded by the BBVA Foundation in the competitive Digital Humanities 2017 call. This project led to the creation of the interactive digital platform “The railway and the city in the Iberian Peninsula (1850–1950)”. The work is a catalogue and a compilation of railway information of various types and formats for 91 Spanish and 25 Portuguese cities. In this project, we want to maintain the interdisciplinary approach to industrial heritage and the integration and convergence of humanities and digital technologies for knowledge aimed at a society without cognitive, physical and cultural barriers [25]. Thanks to Clara Álvarez, Davide Curatola Soprana, Rodrigo de la O, Ramón Gómez, Luis Moya, Melin Nava, Isabel Rodríguez de la Rosa, Beatriz Salidoand Diego Toribio for their collaboration in the research. We are also grateful to the “Archivos de la Transición” [Figure 4] and Milla Hernández Pezzi for the transfer of rights for the reproduction of images (Figure 14a,b).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Madrid acuosa. LaPa Laboratorio de Paisaje. Available online: https://la-pa.es/madacuosa/ (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- Proyecto Agua (Water Project). Available online: https://www.iagua.es/ (accessed on 11 December 2022).

- RedOTRI Universidades. Las Oficinas de Transferencia de Resultados de Investigación (OTRI). Available online: http://www.redotriuniversidades.net/index.php/presentacion?id=272 (accessed on 11 December 2022).

- Devoto, G.; Oli, G.C. Dizionario della Lingua Italiana, 1st ed.; Edumont Le Monnier: Florence, Italy, 2004; p. 2094. [Google Scholar]

- Bourriaud, N. Postproducción, 2nd ed.; Adriana Hidalgo Editora: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2004; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Interferencias de Crítica: Arquitectura y Ciudad. Available online: https://interferenciasdecritica.com/trahere/ (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Consorcio Urbanístico Pasillo Verde Ferroviario de Madrid. Folleto Informativo de la Operación; Ayuntamiento de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- García Santos, A. El Pasillo Verde Ferroviario de Madrid, una experiencia de gestión. Planur-e Territ. Urban. Paisaje Sostenibilidad Diseño Urbano 2015, 25, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- López de Lucio, R.; Ardura, A.; Bataller Erguix, J.J.; Tejera Parra, J. Madrid 1979–1999: La Transformación de la Ciudad en Veinte Años de Ayuntamientos Democráticos; Ayuntamiento de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2016; Volume 2, pp. 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Guía de Arquitectura de Madrid. Available online: https://www.coam.org/es/fundacion/servicio-historico/guia-arquitectura-madrid (accessed on 21 November 2020).

- Brandis, D.; del Río, M.I. As grandes operaciones de transformación urbana. El Pasillo Verde Ferroviario de Madrid. Ería 1995, 37, 113–128. [Google Scholar]

- SECTRA. Programa de Viabilidad y Transporte Urbano. Gobierno de Chile. Available online: http://www.sectra.gob.cl/biblioteca/detalle1.asp?mfn=999 (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Sambricio, C.; Ramos, P. El Urbanismo de la Transición: El Plan General de Ordenación Urbana de 1985; Ayuntamiento de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 378–381. [Google Scholar]

- Ayuntamiento de Madrid. Madrid Proyecto Madrid; Ayuntamiento de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 1997.

- Trovato, G. Madrid, Entre Río y Raíles. Pasado, Presente y Futuro del Pasillo Verde Ferroviario; Lampreave: Madrid, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sambricio, C. Madrid entre historia y actualidad. Estructura y forma de la ciudad. In Madrid, Milano: Forma della Città e Progetto Urbano; Caputo, P., Ed.; Electa: Milano, Italy, 1998; Volume 1, pp. 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Trovato, G. Entrevista a Maite Gómez, Presidenta de la Asociación Pasillo Verde Imperial. Available online: https://interferenciasdecritica.com/entrevista-a-maite-gomez/ (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Archivos de la Transición. Available online: https://archivodelatransicion.es/ (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Exhibition Between River and Rails—CentroCentro. Available online: https://www.centrocentro.org/exposicion/entre-rio-y-railes (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- TRAHERE YouTube Channel. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCFpiqlNQKbzqHBeOU5BugWA (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- CentroCentro Cibeles. Available online: https://www.flickr.com/photos/centrocentrocibeles/ (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- Instagram Live—Guided Tour @edicionesasimetricas "Entre Río y Raíles" con Graziella Trovato desde @centrocentrocibeles. Available online: https://www.instagram.com/p/CkeCJ8XAGyo/?hl=es (accessed on 2 November 2022).

- Cabeza, G.; Moya, L. Ampliación de la Casa de Delicias, 139. Madrid 1981–82; Arquit. COAM 1983, 245, 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mantzou, P.; Trovato, G. Architecture in the Digital Machine Age. Critic All. In Proceedings of the I International Conference on Architectural Design & Criticism, Madrid, Spain, 12–14 June 2014; Available online: https://www.academia.edu/8975931/Architecture_in_the_digital_machine_age (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- El Ferrocarril y la Ciudad en la Península Ibérica (1850–1950). Available online: http://ciudadyferrocarril.com/ (accessed on 31 October 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).