Abstract

Spatial inequality, spatial injustice, and spatial inequity are topics that have been of great interest for academics in various research fields. Among them, the uneven distribution and accessibility of urban public facilities (abbreviated as “UPF”) as one of the most predominant research subjects explores the factors that lead to disparities for people to access indispensable resources and services, which might cause significant marginalization for certain communities and further increase overall inequality. Extensive research has contributed to a status-quo understanding of spatial inequality/injustice/inequity in UPFs from demographic, political, and morphological points of view. However, there lacks a detailed set of guidelines, particularly in terms of location-specific urban planning, urban design, and UPF management strategies, which seek for more equitable opportunities for the public to receive and use amenities. To fill the gap, this research carried out an in-depth review of literature that studied spatial inequality/injustice/inequity research related to UPFs. The results showed that the findings of the current literature that studied spatial inequality/injustice/inequity research in UPFs can be mainly distinguished into three aspects: (a) morphology: the spatial structure and character of physical urban elements; (b) quantity: the uneven quantity of UPFs; (c) quality: the disparity in the quality of UPFs. Based on that, this research proposed empirical planning and design interventions from a spatial perspective. In conclusion, a framework that displays a hierarchical process of understanding and interpreting the spatial inequality/injustice/inequity in UPFs from an ambiguous concept to detailed interventions was developed, extending knowledge-based principles for urban practitioners to thoroughly understand and communicate an equal and inclusive urban environment.

1. Introduction

As an adverse effect of globalization and liberalization, inequality has been a core subject of academic inquiry in the fields of geography (e.g., [1,2,3,4]), development studies (e.g., [5]), economics (e.g., [6,7]), environmental and urban studies (e.g., [8,9]), etc. It is a controversial problem which has caused long-lasting debates through the political, economic, or regional planning decision-making processes since the late 1980s [1,10]. As a key dimension of inequality, spatiality has triggered scholarly discussions, especially on its extent, dimension, consequence, and the policy [1]. It facilitates multidisciplinary research branches, such as spatial inequality [1], spatial justice [11], spatial inequity [12], environmental justice [8], urban inequality [4], urban justice [13], and landscape justice [14]. Throughout these subjects, the terms inequality, inequity, and injustice sometimes overlap and are not mutually exclusive. To establish the research scopes of these studies, it is necessary to identify the distinctions among them.

The definition of inequality is “difference in size, degree, circumstances, etc.; lack of equality”, which means it is potentially a neutral description of variation. The term injustice is defined as “an unfair act or an example of unfair treatment”, and inequity describes “a lack of fairness or justice” [15]. In definitional terms, injustice and inequity are conceptually interchangeable, but they cannot be used interchangeably with inequality. For example, the differences in the distribution of retirement centers can exist without injustice. Inequality is explained by the difference in individual needs or choices, whereas inequity exists when some people in need do not have basic nursing service or lack the access to nursing centers while others have more. Even though differences and intersections of these three terms do exist in a definitional context, from a spatial perspective, they are not obviously distinguishable and tend to overlap slightly when describing the phenomena, mechanism, and consequence of unequal issues. For example, the uneven geographical distribution of parks and urban green spaces (e.g., [16,17]), unequal access to educational resources and medical services (e.g., [18]), and unjust urban planning strategies and policies (e.g., [19,20]). Thus, this study refers to spatial inequality/injustice/inequity concurrently, with the intention to include a comprehensive overview.

As a predominant research subject, Urban Public Facility (abbreviated as “UPF”) refers to urban public services provided directly or indirectly by governments. UPF are the carriers of urban public services, which are related to the shaping of the urban environment and spatial structure as well as the normal operation of urban systems [21,22]. The uneven distribution and accessibility of UPFs leads to inequality for local residents to access public resources, marginalizing certain vulnerable communities and further increasing overall injustice and inequity [22,23,24]. The research scope of UPF studies has expanded more recently, where some academics have focused on essential livelihood facilities, such as educational facilities and medical services [25,26,27,28], while others have focused on public services for higher-level needs including landscape and recreational facilities [29,30,31]. Throughout previous studies, six main categories of UPF can be generated as: transportation facilities (e.g., transit stop, traffic network), healthcare facilities (e.g., clinic, hospital), educational facilities (e.g., primary school, high school), landscape spaces (e.g., urban green space, park, street trees), recreational facilities (e.g., sports hubs, play-space, libraries) and commercial facilities (e.g., retail shop, shopping center). Research on the spatial inequality/injustice/inequity found in UPFs is highly interdisciplinary and integrates social, political, and morphological concerns, which can be categorized into three approaches:

- (1)

- Socio-demographic factors and the spatial inequality/injustice/inequity in UPFs: The corresponding research intends to explore the relationship between demographical characters and UPFs from a spatial perspective. For example, Sun et al. [32] and Neutens et al. [33] studied the correlations between income gap and the unequal supply of UPFs across different districts in urban areas. Recent research which has explored differences in the quality and quantity of educational facilities for migrant workers and local residents are explored by Wu et al. [34]. Zeng et al. [35] and Yang et al. [36] showcased that marginalized communities living in affordable housing have a more limited level of access to UPFs than the other community members. Moreover, there are a few studies that link gender to spatial inequality and the ability to access UPFs. See Maroko et al. [37] for a study that explores the spatial injustice that homeless women face when seeking Healthcare facilities. Moreover, a study exploring women’s bypassing behavior when seeking medical facilities in remote areas was conducted by Ocholla et al. [38].

- (2)

- Governmental policies and economic activities referring to the spatial inequality/injustice/inequity in UPFs: Studies under this category showed a significant interest in investigating the underlying reasons of spatial inequality/injustice/inequity in the supplement of UPFs through governmental policies and economic activities. Chae et al. [39] point out the negative effects of urban shrinkage on spatial inequality and showcased that urban economic shrinkage results in the unequal supplement of educational facilities, medical facilities, commercial facilities, and recreational facilities. Mobaraki et al. [40] proved that the uneven redistribution of income and resources by the government may cause injustice in allocating UPFs. In addition, Habibov [41] showed that, in areas where private healthcare is more common, people without healthcare subsidies would need to pay more for expenditures when seeking medical attention.

- (3)

- The spatial allocation and distribution of UPFs: This category addressed the attributes and organization of UPFs from a spatial perspective, which mainly includes research that models the location-allocation of facilities, analyses the spatial layouts of UPFs, as well as the unequal accessibility of different UPFs caused by uneven urban development [42,43,44,45]. Lan et al. [46] also reveal the uneven distribution of educational and medical facilities both in urban fringe and inner urban areas. Moreover, a recent study by Zhao et al. [47] discusses differences in high and low-income districts in terms of the quantity of commercial and recreational facilities. Chen et al. [48] explore the geographical concentration of high-quality medical facilities in a Chinese urban context and reveal its negative impact on tidal traffic phenomena.

As the evidence above points out, extensive attempts have been made to parse and understand how social differentiations, decision making processes, and spatial patterns act on the spatial inequality/injustice/inequity in UPFs. However, there is still a lack of detailed guidelines in terms of location-specific design strategies for more equitable opportunities to access and use UPFs. Therefore, the research hypothesis of this paper is that an analytical lens to understand and interpret the spatial inequality/injustice/inequity in UPFs from an ambiguous concept to detailed interventions is needed, with an aim to provide a systematic method and spatial perspective to recognize and unscramble spatial inequality problems in UPFs for the further research. To fill the gap, this research provides a comprehensive overview of the spatial inequality/injustice/inequity research in UPFs and develops a systematic framework to diagnose spatial problems of UPFs, translating them into design language and proposing empirical interventions in a local context.

2. Materials and Methods

To provide a systematic overview of the relationship between UPFs and different dimensions of inequality/injustice/inequity related to spatial distribution, configuration, or policymaking, the authors have collated and reviewed a vast quantity of relevant research. This was done in order to have a better understanding of how spatial inequality/injustice/inequity is rooted in UPFs and the subsequent reflection of inequality/injustice/inequity within the spatial guidelines of the design and planning process.

2.1. Material Collection

A literature review was conducted through the Web of Science database accessed in September 2021, which combined three groups of keywords. The first included terms of “inequality”, “equality”, “injustice”, “justice”, “inequity”, “equity” in order to collect all papers with direct or indirect relations with the fact of unfair and unequal situations. The second part was to distinguish the studies of UPFs, which contained terms of “facility”, “amenity”, and “public service”. Moreover, the search added “spatial” to identify research that discusses the inequality/injustice/inequity issues of UPFs from a spatial perspective. All three groups of keywords were combined with the Boolean operation “AND” to find precise matches. An integrated query string was shown as “TS = ((inequality* OR equality* OR injustice* OR justice* OR inequity* OR equity*) AND spatial* AND (“facility*” OR “amenity*” OR “public service*”))”. The dataset was restricted to English-written journal articles, books, book chapters, and conference papers, and a total of 284 papers were found, spanning from 1993 to 2021. Through the “duplicate removal” function in CiteSpace, 9 duplicates were removed from the search resulting in 275 articles.

After the data were gathered, abstracts were screened and analyzed for their relevance to the research objective. Contents of the retained papers had to meet at least one of the following criteria: (1) locational studies of UPFs; (2) efficiency and equity concerns of UPFs; (3) the usage of UPFs in local communities; (4) underlying reasons of the uneven allocation and accessibility of UPFs (e.g., urban planning process, cost and benefit concerns of the government); (5) methods to reconfigure UPFs for equal access. After the selection, a total of 64 papers were eventually included for further review.

2.2. Research Methods

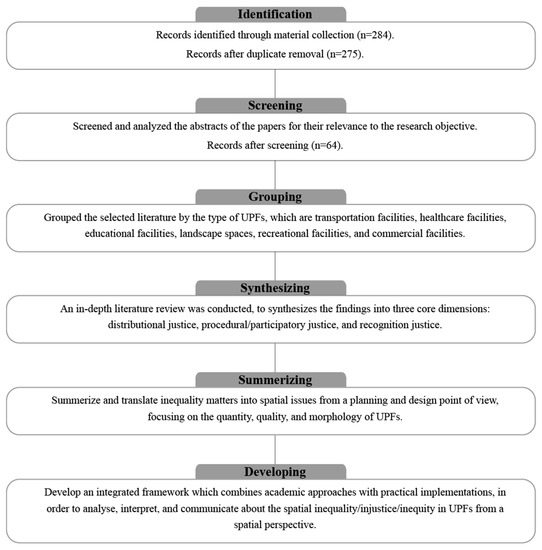

In order to thoroughly understand the literature and establish targeted spatial principles and guidelines from a design and planning perspective, it is important to recognize which dimensions of inequality/injustice/inequity are discussed in this research, as well as the spatial issues that are indicated. To answer this question, the authors first grouped the selected literature by the type of UPFs, which are transportation facilities, healthcare facilities, educational facilities, landscape spaces, recreational facilities, and commercial facilities. Then, an in-depth review of the literature was conducted, and synthesizes the phenomena of spatial inequality/injustice/inequity into three core dimensions of environmental justice: distributional justice, procedural/participatory justice, and recognition justice [49]. Distributional justice concerns the equal per capita distribution of resources; an equality and guaranteed standard of environmental quality for everyone (i.e., clean water, basic standard of air quality); and a guaranteed variation above the minimum based on personal choices and expressed personal preferences [50]. Procedural/participatory justice ensures that those formulating the procedures should maintain elements of neutrality, and that stakeholders should be well represented in the process of decision-making [51,52,53]. Recognition justice implies that people’s unique socio-cultural and local identities (i.e., immigrants, ethnicity, age, gender) are valued, respected, acknowledged, and that they experience fair treatment [52,54]. Based on these particular dimensions of inequality/injustice/inequity, spatial issues in UPFs, either from a distributional, procedural, or recognition perspective, could be explicitly discerned and summarized. As a step forward, evidenced-based empirical planning and design interventions related to spatial issues were proposed in order to promote an inclusive and equal urban environment. Figure 1 shows the workflow of the methodology of this research.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the literature review process.

3. Results

3.1. Transportation Facility

Transportation facilities enable people’s accessibility to other UPFs and have a significant impact on building an equal, inclusive, and sustainable living environment. From the perspective of distributional justice, well-developed transportation facilities require an equally distributed public transportation network (i.e., highways, pedestrians, bike lanes) and transit centers (i.e., bus stops, train stations, subway stations) across districts, as well as the equal quality of transportation facilities that guarantees minimum transportation options with variation based on personal choices and preferences (e.g., the quantity of streetlights, the safety and quality level of streetscapes). For example, Xiao et al. [55] pointed out that the distribution of walkable streets plays a vital role in guaranteeing equal access to other types of UPFs and increases convenience in Shenzhen, China. In addition to a slow-traffic system, Li et al. [56] and Zhao et al. [47] examined the uneven distribution of express transportation networks at a city scale and reveal that urban fringe areas normally contained fewer public transportation connections. In other vulnerable regions, such as flood risk areas, some research has found that transportation facilities are greatly influenced by extreme climate events, which highly obstructs people’s access to disaster recovery or other essential livelihood facilities (see, for example, Vadrevu and Kanjilal [57]). Unequal problems were also found in high-density urban areas, and through urban shrinkage, the dilemma of megacities started emerging. For example, residents living in older urban districts may undergo unequal access to local services (e.g., educational facilities, medical facilities, commercial facilities, recreational facilities) due to degraded transportation facilities, meanwhile developing a new urban transportation network could be too expensive [39]. Moreover, an unequal quality of transportation facilities could limit the accessibility. Su et al. [58] revealed that a low quality of streetscapes notably in low-income districts would limit people’s traffic options and affect people’s preference in travelling. This further damages the accessibility to other UPFs and then influences the acquisition of equal educational and job opportunities. Research from the dimensions of recognition justice and participatory justice in transportation facility acknowledges the relations between spatial inequality and the demand disparity and preference of different social groups, and the necessity of integrating them into decision-making progress. For instance, Weng et al. [59] discuss that considering a child’s experience and the challenge they face compared to adults, it is necessary to be conscious about the unequal accessibility for the family with children to their point of interests through the planning of transportation systems.

Overall, key issues in terms of the inequality/injustice/inequity of transportation facilities from a spatial perspective are summarized as: (1) the uneven distribution and coverage of transportation network; (2) temporary breakdown of transportation systems caused by extreme climate events; (3) the uneven quality of transportation facilities across districts; (4) the failure to recognize the walkability of different social groups. Based on the research evidence, probable design and planning interventions from a practical perspective can be generalized as developing an extensive, efficient, and resilient transportation system, improving the spatial quality of transportation facilities, and integrating more comprehensive demographical research; see Table 1 for detail.

Table 1.

The synthesized spatial inequality issues and the corresponding design and planning interventions of transportation facilities.

3.2. Healthcare Facility

Healthcare facilities refers to the services that directly relate to public health, including primary medical centers, large hospitals, caring centers (i.e., geriatric care centers, nursing centers), and public toilets. Distributional justice requires: (1) healthcare facilities to be located equally across cities or guarantee equal access across districts; (2) avoiding uneven quality development of healthcare facilities across districts. Extensive studies have explored the relationship between the geographical location of healthcare facilities and the inequality in receiving such services. For instance, Liu et al. [60] explored the geographical distribution of geriatric care centers in urban and rural areas in Jiangsu Province, China, and revealed that seniors in rural areas may experience more difficulties when seeking for geriatric care services, for example, the time, money, and emotional burden of travelling to urban areas. Studies from Zhao et al. [47] and Chen et al. [48] referred to the uneven distribution of large hospitals and its negative impacts on providing equal medical services across mega cities in China. Their studies revealed that communities living in remote or suburban areas have lower accessibility to large and high-quality hospitals because of the travel time and costs. In addition, Gao et al. [61] pointed out that the geographical concentration of high-quality hospitals would cause tidal traffic phenomenon, which would further decrease the accessibility of these facilities. Ruktanonchai et al. [62] and Munoz and Kallestal [63] showcased that lack of MNH (maternal and newborn health) facilities or the low quality of MNH facilities cause high infant and mother mortality rates, especially in financially challenged communities living in remote areas. There are also a few scholars who explored healthcare facilities from the perspective of recognition justice. For example, Gu et al. [64] showed that even though several geriatric care centers are located close to transit centers in Nanjing, China, seniors prefer to walk there rather than take public transportation. The low walkability in these areas may lower the accessibility of these relevant facilities for the elderly. Maroko et al. [37] studied the inequality in the quality of public toilets in Manhattan, New York, by examining how they provide menstrual hygiene materials (MHM) service and products for women experiencing homelessness. Moreover, Ocholla et al. [38] discussed the bypassing behaviors of less-educated women who seek care for their newborn in remote areas. They found that care seekers bypassed their nearest inpatient newborn unit because women prefer delivery facilities where they feel respected, and the health workers can be trusted. Failure to recognize the demands and preferences of vulnerable social groups leads to a failure of providing equal healthcare service for all people.

Throughout these relevant approaches, spatial-oriented issues of unequally planned and designed healthcare facilities can be summarized as: (1) the uneven distribution of healthcare facilities, (2) the geographical concentration of high-quality medical facilities, (3) lack of MNH facilities in remote areas, (4) public toilets failed to provide services for women experiencing homelessness, (5) failure to recognize the bypassing behavior of women care-seekers in remote areas, (6) low walkability for the seniors to geriatric care facilities. To address the above problems, practical design and planning interventions can be generalized as improving the efficiency of transportation network, integrating smaller scale healthcare facilities, improving the spatial quality of healthcare facility, and integrating more comprehensive demographical research; see Table 2 for details.

Table 2.

The synthesized spatial inequality issues and the corresponding design and planning interventions of healthcare facility.

3.3. Educational Facility

Educational facilities refer to structures providing educational purposes, such as primary schools and middle schools. Previous studies point out that disparities always exist according to the locational determinant and some demographic factors. To be specific, Li et al. [56] and Lan et al. [46] found that in large cities of China, the quantity variance of schools between old urban districts and newly developed areas such as urban fringe and outer suburbs directly cause spatial and educational inequality. Wu et al. [34] explored that in migrant worker gathering areas in Hangzhou, China, a shortage of schools led to low graduation rates, which then limits job opportunities and causes income inequality in the long-term. In addition, supply-demand concerns of educational services would effectively influence the surrounding residents and their ability to afford and use public facilities. For example, Wolf et al. [65] found that in Vagos, Portugal, if a new public school is planned in a district with few school-aged children, the inevitable rise of housing values/prices could aggravate the financial burden of low-income households. Apart from distributional studies, behavior preferences between different social groups might cause unequal accessibility. The study from Weng et al. [59] showcased that a walkable street for adults may be hard to travel through or even unwalkable for children, which means that the quality of a nearby transportation facility would influence families with children to achieve certain educational facilities.

Based on the above literature, spatial inequality issues in the planning and design of educational facilities can be summarized as: (1) the uneven distribution of schools in specific areas referring to the unequal accessibility; (2) low walkability may restrict children’s travel options to educational facilities; (3) the planning of schools may lead to a rise in housing value/price, which causes financial burden for certain communities; (4) low-income households are more willing to pay for educational facilities, which causes heavier financial burdens. To address the above problem based on existing research, potential design and planning interventions are developing more efficient transportation facility, improving the quality of transportation facilities near educational facilities, incorporating more comprehensive demographical analysis; see Table 3 for details.

Table 3.

The synthesized spatial inequality issues and the corresponding design and planning interventions of educational facility.

3.4. Commercial Facility

Commercial facilities refer to structures used for providing commercial services, which include but are not limited to retail shops, wholesales, shopping malls, mercantile facilities, and banks. Many studies pointed out the distribution and accessibility of commercial facilities always depend on the allocation and quality of other UPFs. Zhao et al. [47] and Ou et al. [66] suggest that a newly developed school or hospital can potentially attract small-scale commercial facilities, such as retail shops and sub-branches of a bank. Li et al. [67] examined the relationship between the location of a commercial facility and transportation facility. Their study showed that poor a transportation network would worsen the case of unevenly distributed commercial facilities in a city, and cause severe inequality when people are willing to travel to such services. Meanwhile, Xiao et al. [55] noted even though the quantity of commercial facilities were sufficient, low walkability of streets might lead to unequal access, especially for older people and children. Online shopping, as an alternative commercial mode, is proposed to be a solution for people living in areas with inconvenient transportation network. However, due to the uneven coverage of delivery services, the unequal phenomenon might persist [68]. From the perspective of recognition justice, a few studies investigated demands and preferences from specific social groups. Zeng et al. [35] indicated that people living in affordable houses prefer walkable small-scale commercial facilities rather than large shopping centers. Thus, such communities located in newly developed areas, such as urban fringe areas or outer suburbs, did not really cause serious spatial inequality. Through the planning process of these housing projects, it is necessary to recognize and respect the opinions and particular needs of the community [35].

In summary, the inequality problem of commercial facilities can be identified from a spatial perspective as follows: (1) the uneven distribution of commercial facility; (2) low accessibility due to poor transportation network; (3) low quality of streets leading to unequal accessibility; (4) lack of recognition for specific social groups and the corresponding participation during the planning process. Based on previous research findings, potential design and planning interventions can be generalized as investing in transportation system in remote areas, setting multiple scale and spatial layers of commercial facilities, introducing alternatives of large commercial facilities, and integrating more comprehensive demographical analysis; see Table 4 for details.

Table 4.

The synthesized spatial inequality issues and the corresponding design and planning interventions of commercial facility.

3.5. Recreational Facility

Recreational facilities refer to urban amenities for culture, sports, and entertainment, which includes community sports hubs, museums, libraries, and public spaces. A few studies explore the geographical distribution of recreational facilities and the following spatial inequality. Specifically, Zhao et al. [47] revealed that low-income districts always lack recreational facilities. Thus, residents’ accessibilities to recreational activity were potentially restrained in Xiamen, China. Li et al. [56] found that in Shanghai, China, the distribution of recreational facility also influenced the nearby housing values, i.e., adequate amenities indicate a higher housing value, while financially challenged communities need to pay more time and money to access recreational facilities. Chen et al. [30] showcased the problematic urban renewal of old districts, in which recreational facilities need to be supplemented and upgraded, but the compact urban layout only provides limited spaces to be developed. In addition, the uneven coverage of the transportation network or poorly developed transportation system across the city decreased the accessibility of large-scale recreational facilities (e.g., sports centers, museums, municipality libraries) [69]. Apart from the locational study of recreational facilities, Delafontaine et al. [70] examined how the management of recreational facilities could cause inequality. Their study revealed that in addition to the concentrated distribution, fixed opening hours of public recreational facilities also lead to unequal accesses because it neglects the demand-difference of different social groups.

In short, the spatial inequality issues of recreational facilities from a design and planning perspective can be summarized as: (1) The uneven distribution of recreational facilities referring to income differences; (2) lack of vacant spaces to develop new recreational facilities in certain areas; (3) low quality and uneven coverage of transportation facilities lead to accessibility problems; (4) failure to recognize the demand-difference of various social groups. Empirically customized design and planning interventions can be summarized as investing in more efficient transportation facilities, integrating smaller scale recreational facilities in certain areas, incorporating more comprehensive demographical and observational research; see Table 5 for details.

Table 5.

The synthesized spatial inequality issues and the corresponding design and planning interventions of recreational facility.

3.6. Landscape Spaces

Landscape spaces refer to the UPFs that provide landscape services to the public, such as small urban green spaces, large urban parks, green belts, and street trees. A majority of spatial inequality/injustice/inequity studies focused on the distribution of landscape spaces and the consequent direct/indirect effects for local residents (e.g., urban heat relief effects, public health improvement, and the beautification of urban environments). Representative examples include the work of Guo et al. [71,72] who explored the uneven distribution of urban green spaces across districts resulting in the chances for people to receive the benefits of landscape resources. Xiao et al. [73] studied the distribution of parks greater than 10 ha in Hongkong from a spatial inequality perspective, revealing that large-scale concentrated landscape areas could provide a few benefits for the living environment. However, they were always distributed remotely and difficult for the people to access due to the high travel and time costs. Nelson et al. [74] showed that deprived communities could be facing more climate challenges because of the uneven distribution of urban trees. Moreover, the quality of landscape spaces would exacerbate the inequality, especially for financially-challenged-communities, to access nature and then increase the overall burden. A study by Pérez-Paredes and Krstikj [75] revealed that parks with safety issues were often found in low-income areas, which would lower the usage rate of landscape spaces. Ibes [76] also pointed out that landscape spaces which are in/surrounded by low-income communities were always lacking maintenance which led to low quality and less utilization. Apart from distributional justice, several studies concentrated on the inequality in accessing landscape spaces from the perspective of recognition justice. Guo et al. [72] found that for elderly people, landscape spaces that were located in an unwalkable distance or connected by low-walkability-streets are considered inaccessible. Feng et al. [77] discovered that parks that hold different kinds of events or activities were favored by children and families with children than other types of landscape spaces. Ibes [76] suggested that the government can use observational research, such as the system for observing play and recreation in communities (SOPARC), to determine who is using these spaces and for future evidence-based planning of landscape spaces.

To sum up, planning and design-oriented spatial issues concerning the inequality in landscape resources can be summarized as: (1) The uneven distribution of landscape spaces; (2) the disparity in the quality of landscape spaces; (3) failure to recognize the preference and usage of landscape spaces among different age groups. Throughout the relevant research findings, potential spatial interventions can be generalized as supplementing landscape features, planning landscape spaces close the transportation facilities, incorporating demographical and observational analysis; see Table 6 for details.

Table 6.

The synthesized spatial inequality issues and the corresponding design and planning interventions of landscape resource.

4. Discussion

4.1. Empirical Interventions for Spatial Inequality Issues in UPFs

This research involved a comprehensive literature review of the spatial inequality/injustice/inequity research in UPFs, diagnose spatial problems of UPFs, translating them into design language, and proposing empirical interventions in a local context. As the results of this research point out, the spatial problems of UPFs can be summarized as the uneven distribution or coverage of UPFs, the disparity in the quality of UPFs, the failure of recognizing special preference and behavior of different social groups, and the failure of engaging adequate stakeholders in the decision-making process. From the urban planning perspective, proposed interventions can be mainly synthesize as: (a) planning integrated transportation network to improve the service radius of UPFs; (b) incorporating demographical analysis and observational research into the early planning process; (c) incorporating participatory approach into the early planning process; (d) boosting smaller scale community based UPFs in deprived areas; (e) raise the walkability of streets around UPFs. From the urban designing perspective, proposed interventions can be summarized as: (a) designing public spaces to fit in multiple types of smaller scale UPFs; (b) redesign vacant or abandoned spaces into new smaller scale UPFs; (c) supplementing urban features (i.e., urban trees, urban furniture) to raise the quality of UPFs; (d) boosting signage and guiding systems around UPFs. As for the UPF management perspective, interventions from the following aspects were proposed: (a) boosting long-term local engagement maintenance system; (b) encouraging local communities to host inclusive events and activities; (c) organizing free check-up and assessment services for people in need; (d) providing waiting facilities (i.e., waiting homes, resting spaces) for people who travel from a far distance.

The above interventions were generated based-on the specific spatial problems pointed out by previous literature. By doing so, this research established extensive knowledge-based design and planning interventions in terms of the equal distribution and configuration of UPFs for spatial designers and decision makers in future practices.

4.2. Analytical Framework for the Spatial Inequality in UPFs

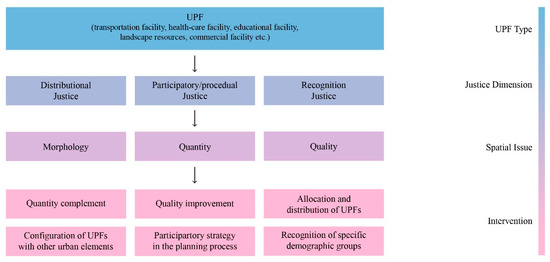

As exemplified by this research, reviewing a vast amount of literature referring to the spatial inequality/injustice/inequity in UPFs holds the potential for both researchers and practitioners to understand the uneven allocation, distribution, and configuration of resources and services across areas and facilitate corresponding design and planning guidelines to achieve a more inclusive and equal urban environment. After extracting and synthesizing the findings, an analytical framework for diagnosing dimensions of inequality in UPFs, interpreting spatial attributes, and proposing location-specific interventions has been elaborated as follows.

As Figure 2 shows, there are four layers that guide the interpretation and communication of the matter of UPF’s spatial inequality/injustice/inequity, which contains UPF type, dimension, spatial issue, and intervention. Different types of UPF have distinct contents and characteristics. To identify the scope and gain an explicit profile of the targeted UPF, it is important to absorb its sub-categories, components, attributes, and service radii (Layer 1). Dimensions of inequality/injustice/inequity are applied to analyze and categorize the detailed unequal phenomena of UPFs (Layer 2). Typically, distributional justice, participatory/procedural justice, and recognition justice are the three key dimensions, which respectively focuses on the morphological, political, and socio-demographical perspectives of the spatial inequality in UPFs [49]. Then, inequality matters can be translated into spatial issues from a planning and design point of view, especially on the quantity, quality, and morphology of UPFs (Layer 3). To be specific, morphology refers to the spatial distribution and organization of UPFs; quantity indicates the numerical allocation of UPFs in a certain area; quality addresses the standard character of UPFs. In response to spatial issues, design-based and planning-based spatial interventions can be proposed primarily from the following aspects: (a) quantity complement; (b) quality improvement; (c) allocation and distribution of UPFs; (d) configuration of UPFs with other urban elements; € participatory strategy in the planning process; (e) recognition of specific demographic groups (Layer 4). This analytical framework displays a hierarchical process of understanding and interpreting the spatial inequality/injustice/inequity in UPFs from an ambiguous concept to detailed interventions. On the one hand, it supplements the body of knowledge, which enables spatial planners and urban designers to become more conscious about fundamental spatial inequality/injustice/inequity effects relevant to the optimization and design of UPFs. On the other hand, it provides a systematic method and spatial perspective to recognize and unscramble spatial inequality problems in UPFs for the further research.

Figure 2.

The structure of the analytical framework for understanding, interpreting, and communicating the spatial inequality/injustice/inequity in UPFs.

4.3. Limitations

To have a comprehensive understanding of the spatial inequality/injustice/inequity referring to UPFs from a design perspective, this research incorporates a systematic review of a large amount of relevant literature, provides an analytical framework to identify spatial issues behind the unequal status, and proposes pragmatic interventions, which are of fundamental importance for planning and design practices. However, it still has limitations in the research scope and content which can be further explored in future studies.

(1) The material collection stage of this study used the terms “facility*”, “amenity*”, and “public service*” to collect papers that focus on the facilities that are the direct carriers of public services, which are related to the shaping of the urban environment and spatial structure. However, there are studies that align with this paper’s research goal but did not use these terms to label themselves. For example, He et al. [78,79] studied the impact of urban heat on population migration and indicated guidance for potential cooling systems and heat prevention facilities. Such studies also presented findings that generate interventions from the perspective of urban planning, design, and management that respond to spatial inequality/inequity/injustice in UPFs.

(2) The selected literature in this study takes an expert approach as the basis which mainly focuses on measuring and describing the spatial inequality/injustice/inequity of UPFs based on the distribution and configuration of spatial elements and relevant socio-geographic factors. However, this does not exclude nor dismiss the importance of grasping the spatial inequality in UPFs from the user’s perspective. Studies that explored the individual’s perception of fairness or people’s evaluation through the use of public amenities also should be included, in order unearth an integrated understanding of the spatial inequality/injustice/inequity in UPFs.

(3) Most of the planning and design guidelines proposed in this study are tangible urban structures, yet there are interventions without constructive forms from a financial or political perspective, such as different types of subsidies offered by the government (e.g., providing traffic allowance can improve travelling preference and the accessibility to other UPFs) as well as flexible regulations (e.g., extra opening hour of certain government sectors for the public). These intangible interventions also have direct or indirect impacts on improving equal urban environment from a spatial perspective.

(4) This study synthesized and discerned specific spatial problems from previous research that investigated spatial inequality/inequity/injustice issues in UPFs. Though most papers studied spatial inequality/inequity/injustice issues in UPFs with locational-based research methods and their findings and suggestions refer to a specific location (i.e., Shanghai, Montreal, Santiago), this research did not comparatively study the literature from the perspective of similar or different locations. Therefore, in a future step of this research, the common rounds and divergence of studies that are based in the same locations can be analyzed with the aim to propose more targeted and location-specific interventions.

(5) This study respectively investigated the unequal status of different types of UPFs. However, the interplay between UPFs is lacking attention. For example, the allocation of educational facilities has a significant influence on attracting small-scale commercial and recreational facilities [47]. These approaches can be considered by spatial practitioners in order to guide the future development of UPFs as a system.

5. Conclusions

The unequal allocation, distribution, and configuration of UPFs would cause significant inequality in providing resources and services to the local residents, marginalizing vulnerable communities and finally resulting in overall injustice/inequity. Though extensive studies have explored the relationship between spatial inequality/injustice/inequity and UPFs, they did not provide niche targeting guidelines in a practical way to develop an equal and inclusive urban environment. To fill the gap, this paper has conducted a systematic framework for reviewing the existing evidence and interlinked spatial inequality/injustice/inequity to UPFs from a planning and design perspective. Based on the analysis of the potential literature, six types of UPFs (i.e., transportation facilities, healthcare facilities, educational facilities, landscape spaces, recreational facilities and commercial facilities) have been analyzed and synthesized through the three dimensions of environmental justice (i.e., distributional justice, participatory/procedural justice, recognition justice) with the intention to translate specific spatial issues into design and planning interventions. The output of this research contributes to: (a) establishing extensive knowledge-based design and planning interventions in terms of equal distribution and configuration of UPFs for spatial designers and decision makers in future practices; (b) providing an integrated framework which combines academic approaches with practical implementations, in order to analyze, interpret, and communicate the spatial inequality/injustice/inequity in UPFs from a spatial perspective.

Author Contributions

Methodology, P.W. and M.L.; Software, P.W.; Formal Analysis, P.W.; Investigation, P.W. and M.L.; Resources, P.W.; Data Curation, P.W.; Writing-Original Draft, P.W.; Visulaization, P.W.; Conceptualization, M.L.; Validation, M.L.; Writing-Review & Editing, M.L.; Supervision, M.L.; Project Administration, M.L., Funding Acquisition, M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by the Starting Research Funds (No. FB45001045) from Harbin Institute of Technology (Shenzhen).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no interest of conflict.

References

- Wei, Y.D. Spatiality of regional inequality. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 61, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.D.; Ye, X. Beyond convergence: Space, scale, and regional inequality in China. Tijdschr. voor Econ. en Soc. Geogr. 2009, 100, 59–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, A. Unequal exchange in the age of globalization. Rev. Radic. Politi. Econ. 2019, 51, 225–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, J.G. American prices and urban inequality since 1820. J. Econ. Hist. 1976, 36, 303–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulme, D.; Toye, J. The case for cross-disciplinary social science research on poverty, inequality and well-being. J. Dev. Stud. 2006, 42, 1085–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozgor, G.; Ranjan, P. Globalisation, inequality and redistribution: Theory and evidence. World Econ. 2017, 40, 2704–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Spatial Inequality and Economic Development: Theories, Facts, and Policies; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Schlosberg, D. Theorising environmental justice: The expanding sphere of a discourse. Environ. Politi. 2013, 22, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihlanfeldt, K.R.; Scafidi, B.P. The neighbourhood contact hypothesis: Evidence from the multicity study of urban inequality. Urban Stud. 2002, 39, 619–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J.E. Macroeconomic fluctuations, inequality, and human development. J. Hum. Dev. Capab. 2012, 13, 31–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikeç, M. Justice and the spatial imagination. Environ. Plan. A 2001, 33, 1785–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ludden, D. Imperial Modernity: History and global inequity in rising Asia. Third World Q. 2012, 33, 581–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincher, R.; Iveson, K. Justice and injustice in the city. Geogr. Res. 2012, 50, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egoz, S.; De Nardi, A. Defining landscape justice: The role of landscape in supporting wellbeing of migrants, a literature review. Landsc. Res. 2017, 42, S74–S89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford English Dictionary; Simpson, J.; Weiner, E. (Eds.) Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Heynen, N.; Perkins, H.A.; Roy, P. The political ecology of uneven urban green space: The impact of political economy on race and ethnicity in producing environmental inequality in Milwaukee. Urban Aff. Rev. 2006, 42, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comber, A.; Brunsdon, C.; Green, E. Using a GIS-based network analysis to determine urban greenspace accessibility for different ethnic and religious groups. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 86, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Kanbur, R. Spatial inequality in education and health care in China. China Econ. Rev. 2005, 16, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fainstein, S.S. New directions in planning theory. Urban Aff. Rev. 2000, 35, 451–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, M.K.; Dunn, C.E. Geo-information tools for participatory spatial planning: Fulfilling the criteria for ‘good’ governance? Geoforum 2012, 43, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, P.; Pinch, S. Urban Social Geography: An Introduction; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Zhou, T.; Mao, C. Does the Difference in Urban Public Facility Allocation Cause Spatial Inequality in Housing Prices? Evidence from Chongqing, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zuo, X. Inside China’s cities: Institutional barriers and opportunities for urban migrants. Am. Econ. Rev. 1999, 89, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F. Boundaries and Categories: Rising Inequality in Post-Socialist Urban China; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apparicio, P.; Séguin, A.-M. Measuring the accessibility of services and facilities for residents of public housing in Montreal. Urban Stud. 2006, 43, 187–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleai, M.; Sliuzas, R.; Flacke, J. An integrated framework to evaluate the equity of urban public facilities using spatial multi-criteria analysis. Cities 2014, 40, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadashpoor, H.; Rostami, F. Measuring spatial proportionality between service availability, accessibility and mobility: Empirical evidence using spatial equity approach in Iran. J. Transp. Geogr. 2017, 65, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransen, K.; Neutens, T.; De Maeyer, P.; Deruyter, G. A commuter-based two-step floating catchment area method for measuring spatial accessibility of daycare centers. Health Place 2015, 32, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Yin, H.; Nakagoshi, N. Using GIS and landscape metrics in the hedonic price modeling of the amenity value of urban green space: A case study in Jinan City, China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 79, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Hui, E.C.-M.; Lang, W.; Tao, L. People, recreational facility and physical activity: New-type urbanization planning for the healthy communities in China. Habitat Int. 2016, 58, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Nagendra, H. Factors influencing perceptions and use of urban nature: Survey of park visitors in Delhi. Land 2017, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Fu, Y.; Zheng, S. Local public service provision and spatial inequality in Chinese cities: The role of residential income sorting and land-use conditions. J. Reg. Sci. 2017, 57, 547–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neutens, T.; Schwanen, T.; Witlox, F.; De Maeyer, P. Equity of urban service delivery: A comparison of different accessibility measures. Environ. Plan. A 2010, 42, 1613–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zheng, X.; Sheng, L.; You, H. Exploring the Equity and Spatial Evidence of Educational Facilities in Hangzhou, China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 151, 1075–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Rees, P.; Xiang, L. Do residents of Affordable Housing Communities in China suffer from relative accessibility deprivation? A case study of Nanjing. Cities 2019, 90, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Yi, C.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, C. Affordability of housing and accessibility of public services: Evaluation of housing programs in Beijing. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2014, 29, 521–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroko, A.R.; Hopper, K.; Gruer, C.; Jaffe, M.; Zhen, E.; Sommer, M. Public restrooms, periods, and people experiencing homelessness: An assessment of public toilets in high needs areas of Manhattan, New York. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocholla, I.A.; Agutu, N.O.; Ouma, P.O.; Gatungu, D.; Makokha, F.O.; Gitaka, J. Geographical accessibility in assessing bypassing behaviour for inpatient neonatal care, Bungoma County-Kenya. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, J.S.; Choi, C.H.; Oh, J.H.; Chae, Y.T.; Jeong, J.-W.; Lee, D. Urban Public Service Analysis by GIS-MCDA for Sustainable Redevelopment: A Case Study of a Megacity in Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobaraki, H.; Hassani, A.; Kashkalani, T.; Khalilnejad, R.; Chimeh, E.E. Equality in distribution of human resources: The case of Iran’s Ministry of Health and Medical Education. Iran. J. Public Health 2013, 42, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibov, N.N. The inequity in out-of-pocket expenditures for healthcare in Tajikistan: Evidence and implications from a nationally representative survey. Int. J. Public Health 2011, 56, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, L. Location-allocation problems. Oper. Res. 1963, 11, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdziej, J. Using hexagonal grids and network analysis for spatial accessibility assessment in urban environments–a case study of public amenities in Toruń. Misc. Geogr. 2019, 23, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stanley, B.W.; Dennehy, T.J.; Smith, M.E.; Stark, B.L.; York, A.M.; Cowgill, G.L.; Novic, J.; Ek, J. Service access in premodern cities: An exploratory comparison of spatial equity. J. Urban Hist. 2016, 42, 121–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Liu, D.; Lu, M. City size, migration, and urban inequality in China. China Econ. Reivew 2018, 51, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, F.; Wu, Q.; Zhou, T.; Da, H. Spatial effects of public service facilities accessibility on housing prices: A case study of Xi’an, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, G.; Lin, T.; Liu, X.; Liu, J.; Lin, M.; Ye, H.; Kong, L. Towards sustainable urban communities: A composite spatial accessibility assessment for residential suitability based on network big data. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, B.; Liu, X.; Li, X. Mapping the spatial disparities in urban health care services using taxi trajectories data. Trans. GIS 2018, 22, 602–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosberg, D. Defining Environmental Justice: Theories, Movements, and Nature; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D. Environmental justice and Rawls’ difference principle. Environ. Ethics 2004, 26, 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, E.A.; Tyler, T.R. The Social Psychology of Procedural Justice; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J. Reactions to procedural injustice in payment distributions: Do the means justify the ends? J. Appl. Psychol. 1987, 72, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G. Environmental Justice: Concepts, Evidence and Politics; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosberg, D. Resurrecting the pluralist universe. Politi. Res. Q. 1998, 51, 583–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Wang, G.; Wang, M. Transportation disadvantage and neighborhood sociodemographics: A composite indicator approach to examining social inequalities. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 137, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, Q.; Shi, W.; Deng, Z.; Wang, H. Residential clustering and spatial access to public services in Shanghai. Habitat Int. 2015, 46, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadrevu, L.; Kanjilal, B. Measuring spatial equity and access to maternal health services using enhanced two step floating catchment area method (E2SFCA)–a case study of the Indian Sundarbans. Int. J. Equity Health 2016, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Pi, J.; Xie, H.; Cai, Z.; Weng, M. Community deprivation, walkability, and public health: Highlighting the social inequalities in land use planning for health promotion. Land Use Policy 2017, 67, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, M.; Ding, N.; Li, J.; Jin, X.; Xiao, H.; He, Z.; Su, S. The 15-minute walkable neighborhoods: Measurement, social inequalities and implications for building healthy communities in urban China. J. Transp. Health 2019, 13, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Du, M.; Shen, J.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Y. Research on Geriatric Care for Equalizing the Topological Layout of Health Care Infrastructure Networks. J. Healthc. Eng. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, T. An empirical spatial accessibility analysis of Qingdao city based on multisource data. J. Adv. Transp. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruktanonchai, C.W.; Ruktanonchai, N.W.; Nove, A.; Lopes, S.; Pezzulo, C.; Bosco, C.; Alegana, V.A.; Burgert, C.R.; Ayiko, R.; Charles, A.S.; et al. Equality in maternal and newborn health: Modelling geographic disparities in utilisation of care in five East African countries. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0162006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, U.H.; Källestål, C. Geographical accessibility and spatial coverage modeling of the primary health care network in the Western Province of Rwanda. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2012, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gu, T.; Li, L.; Li, D. A two-stage spatial allocation model for elderly healthcare facilities in large-scale affordable housing communities: A case study in Nanjing City. Int. J. Equity Health 2018, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J.; Feitosa, F.; Marques, J.L. Efficiency and Equity in the Spatial Planning of Primary Schools. Int. J. E-Plan. Res. 2021, 10, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, G.; Zhou, M.; Zeng, Z.; He, Q.; Yin, C. Is there an equality in the spatial distribution of urban vitality: A case study of Wuhan in China. Open Geosci. 2021, 13, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Chen, J.; Qian, T.; Zhang, W.; Wang, J. Spatial accessibility to shopping malls in Nanjing, China: Comparative analysis with multiple transportation modes. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 710–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeling, K.L.; Schaefer, J.S.; Figliozzi, M.A. Accessibility and Equity Analysis of Transit Facility Sites for Common Carrier Parcel Lockers. Transp. Res. Rec. 2021, 2675, 1075–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, Y. Spatial Accessibility to Local Public Services in an Unequal Place: An Analysis from Patterns of Residential Segregation in the Metropolitan Area of Santiago, Chile. Sustainability 2021, 13, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delafontaine, M.; Neutens, T.; Schwanen, T.; Van de Weghe, N. The impact of opening hours on the equity of individual space–time accessibility. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2011, 35, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Song, C.; Pei, T.; Liu, Y.; Ma, T.; Du, Y.; Chen, J.; Fan, Z.; Tang, X.; Peng, Y. Accessibility to urban parks for elderly residents: Perspectives from mobile phone data. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 191, 103642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Liu, B.; Tian, Y.; Xu, D. Equity to Urban Parks for Elderly Residents: Perspectives of Balance between Supply and Demand. International J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Wang, D.; Fang, J. Exploring the disparities in park access through mobile phone data: Evidence from Shanghai, China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 181, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.; Grubesic, T.; Miller, J.; Chamberlain, A. The equity of tree distribution in the most ruthlessly hot city in the United States: Phoenix, Arizona. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 59, 127016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Paredes, E.A.; Krstikj, A. Spatial Equity in Urban Public Space (UPS) Based on Analysis of Municipal Public Policy Omissions: A Case Study of Atizapán de Zaragoza, State of México. Societies 2020, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibes, D.C. A multi-dimensional classification and equity analysis of an urban park system: A novel methodology and case study application. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 137, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Chen, L.; Sun, R.; Feng, Z.; Li, J.; Khan, M.S.; Jing, Y. The distribution and accessibility of urban parks in Beijing, China: Implications of social equity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.-J.; Wang, J.; Zhu, J.; Qi, J. Beating the urban heat: Situation, background, impacts and the way forward in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 161, 112350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.-J.; Zhao, D.; Xiong, K.; Qi, J.; Ulpiani, G.; Pignatta, G.; Prasad, D.; Jones, P. A framework for addressing urban heat challenges and associated adaptive behavior by the public and the issue of willingness to pay for heat resilient infrastructure in Chongqing, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 75, 103361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).