Abstract

This paper describes a study on the vegetation and floristics of the territory of Beit Jibrin in Palestine, in areas such as Forest the Snabreh (Qasa), Khallet Mahmoud and Khallet AL-Taweel, among others. In view of the lack of studies on the phytosociology and communities of plants in the south-west of Palestine, as this region represents a unique diversity of plants, and the addition of these plants to Mediterranean Basin region plants, we conducted this study to identify and describe the plants of this region. Beit Jibrin is an ancient Canaanite Palestinian city that belongs to inframediterranean and thermomediterranean thermotypes, as well as arid, semi-arid and dry ombrotypes. This area is very important floristically, with a high rate of endemism: of the 290 species documented, 37 of them (12.75%) were endemic to the region. Vegetation was sampled on twelve representative plots (releves) and analyzed using the Braun-Blanquet phytosociological analysis method. Two communities of forest maquis, macchie and steppe vegetation were found. Forest vegetation were represented by the Cupresso sempervirentis–Pinetum halepensis ass. nova. association, in the class of Quercetea ilicis Br.-Bl. ex. A. and O. Bolòs 1950, the order of Pinetalia halepensis, Biondi et al. (2014), and a new alliance: Cupresso sempervirentis–Pinus halepensis; forests maquis vegetation as the association of Pistacio lentisci—Quercetum calliprini ass. nova., with the suggested new class of Quercetea calliprini or palaestini in addition to Quercetea ilicis Br.-Bl. ex. A. and O. Bolòs 1950 and the order of Quercetalia calliprini (Zohary 1960), with an alliance of Quercion calliprini (Zohary 1960). These were adapted in arid, semi-arid, dry and sub-humid ombrotypes, as well as infra- and thermotropical to mesomediterranean thermotypes, with many different types of soils, such as limestone, brown ruinsenas, terra rossa and others.

1. Introduction

Palestine is a hotspot for biodiversity and flora, and is considered one of the most biodiverse countries in West Asia and the Mediterranean coast. Palestinian coastal waters and mountain highlands possess a large level of biological diversity, in addition to many endemic and native species. Geographical and biological diversity is very important, consisting of landscapes and ecosystems that include areas of mountainous heights, plains, valleys, cliffs, sand dunes, steppes and forests. This prompted us to study the plant species of an important region located to the southwest of Palestine, west of the Jordan River and the Dead Sea, with the varieties of wild and forest plants it represents, as it is fertile and rich in forests of various plants. Given the lack of studies on plants’ phytosociology or plant communities in this region, as well as its geographical, topographical, biological and biodiversity importance, it was necessary to work on studying the taxonomic, phytosociological and biological characteristics of plants and others. Ecological, climate change, climatic and bioclimate factors play an important role in plant distribution and biodiversity [1,2,3]. More than 2780 plant species have been studied, of which 162 species were endemic; 872 genera and 144 families have been recorded for Palestinian flora [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Furthermore, some scientists have studied plant communities, the phytosociology of plants [16,17,18] and biodiversity in Palestine [19] in addition to the Mediterranean region [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. The purpose of this paper is to study the phytosociology and plant taxa species of the Beit Jibrin region in the southwest of Palestine as well as of the Mediterranean Basin region, especially the eastern Mediterranean.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

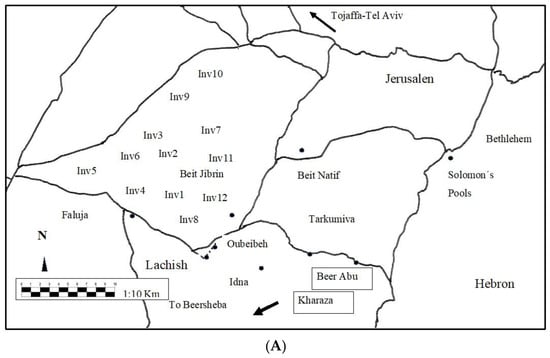

Beit Jibrin (Jibreen) is a Palestinian Arab Canaanite village located 21 km northwest of Hebron and 13 km west of the village of Idna-Hebron, a wide area of hills, mountains and various valleys between the coastal plain to the west and the highland of Hebron to the east, where it is located within coordinates (31°36′19′′ N, 34°53′54′′ E), with rises 275 m above sea level [29]. The total area of the village is 56,185 dunums (56.1 km2), of which 28 km2 are built-up whereas the rest remains as agricultural land [30,31]. Moreover, Beit Jibrin is characterized by the presence of many different archaeological caves (Caves 1000), which were included as a “United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization” (UNESCO) World Heritage Site [32], near which there are many different plants, such as thyme, Pistachios spp., Rhamnus spp., R. palaestinus Boiss. and various herbal plants (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Vegetation in Beit Jibrin (Palestine).

2.2. Vegetation Data Collection

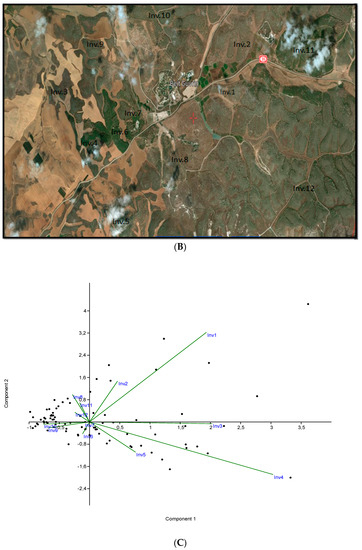

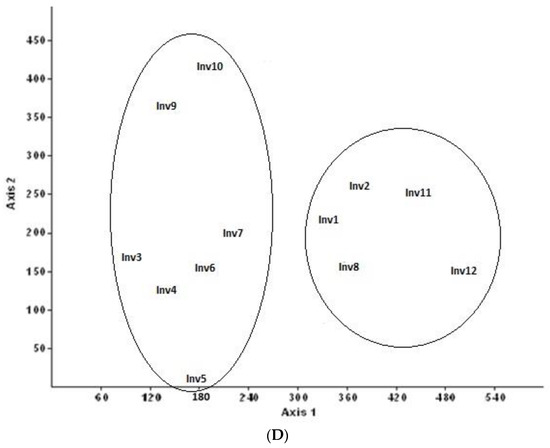

The study included the sampling area in Beit Jibrin, occupied since 1948, where the selection of and data collection of 290 woody plants took place, from Beit Jibrin forests or its hills, as well as some of the scrubland areas, to take biological and ecological indicators and plants for their traditional and thermal patterns (Table 1 and Figure 2A). These data were taken by using a Braun-Blanquet methodology [33,34]. We created a matrix of 290 × 12 related columns to convert the Braun-Blanquet plant phytosociological indicators (+=2, 1 = 3, 2 = 4, 3 = 5, 4 = 6 and 5 = 7) into ones of Van der Maarel [35] (5: covering more than 3/4 of the area; 4: any number of individuals covering ½–3/4 of the area; 3: any number of individuals covering 1/4–1/2 of the area; 2: very numerous or covering at least 5% of the area; and 1: plentiful but of small cover value, and + is a very small amount of cover) (Figure 2B). However, we used a phytosociological nomenclature code in the description of the new syntaxons in the study [36,37,38] and Euclidean distances as well as principal component analysis to evade any lack of data on whole-plant analysis; the XLSTAT Statistical Software for Excel program was used in the analysis process.

Table 1.

Sampling regime.

Figure 2.

(A) The study area from which samples were taken is located in Beit Jibrin; (B) the study area and where the samples were selected by satellite; (C) the principal component analysis; and (D) detrended correspondence analysis.

All the sites mentioned in the table are located in the area of Beit Jibreen and its surroundings—the name of Tal Sandhanh has been changed to Beit Guvrin-Maresha National Park.

The plants of Palestine, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Negev Desert, the Sinai desert and the Mediterranean coast were used in the study of flora, as cover vegetation of sites in the west of Hebron to the east of the occupied Palestinian coasts, such as Beer Sheva, Ashdod, Ashqelon (Asgalan or Al-Majdal), Lod, Ramle, Jaffa, Haifa, Safad, Acre, Iraq Mansheya and Al-Jalil, and neighboring villages, such as Ajjur, Beit Nir, Al-Dawaimah, Kidna, Faluja, Deir Ula, Qubeibeh, Zachariah and Idna [16,17,18], which form part of this adjacent plant environment. The vegetation has been explicated according to many methodological works, such as Braun-Blanquet and Bolòs [37], Bolòs [39], Oakley [40], Bolòs et al. [41], Pott [42], Biondi [43] and Rivas-Martinez et al. [44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. The west Hebron area has a dry climate, inframediterranean to thermomediterranean thermotype, with precipitation ranges between 250 and 550 mm, and Beit Jibrin is a part of this area and the climate [1,18].

2.3. Statistical Analyses

Data were used to create an Excel table with 290 rows (plants) and 12 columns (relèves); from this table we created a Euclidean distance matrix (DCA), to measure distance, and similarity, by the procedure known as the full correlation method. We subsequently applied principal component analysis (PCA), having previously generated two matrices of correlation and covariance values, and detrended correspondence analysis (DCA) ordination analysis. The statistical software tool used was Community Analysis Package (CAP) 4.0, producing two clearly distinct inventories. However, we have two associations or communities: association 1 (ASL1), consisting of forest samples (groups 1, 2, 8, 11 and 12), and association 2 (ASL2), consisting of groups 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9 and 10, which were grouped together in (PCA) and (DCA).

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Forests Vegetation

Cupresso sempervirentis–Pinetum halepensis ass. nova

Inventories 1, 2, 8, 11 and 12 were dominated by species belonging to Pinus and coniferous woodland, such as C. sempervirens L., C. arizonica L., C. macrocarpaa L., P. halepensis Miller, P. pinea L., P. canariensis C. Smith, P. brutia Tenore, J. phoenicea L., J. excelsa M. Bieb., and J. drupacea Labill., the association dominated by P. halepensis Miller, P. pinea L., P. canariensis C. Smith., P. brutia Tenore, C. sempervirens L., C. sempervirens L. var. horizontalis Miller, C. arizonica Greene, T. occidentalis L., J. phoenicea L., J. excelsa M. Bieb., J. drupacea Labill., A. monspessulanum L., F. retusa L., F. sycomorus L., F. cariaca L., C. equesitifolia L. M. alba L., M. nigara L., O. ficus indica (L.) Mill., O. robusta J.C. Wendl., O. ficus-barbarica A. Berger, S. alba L., P. alba L., P. nigra L., P. euphratica Oliver, Q. calliprinos Webb. or Q. palaestina K., Q. inthaburensis Decne., Q. boissieri Reut. or Q. boissieri Reut. var. latifolia (Boiss.) Zohary, Q. infectoria Olivier, Q. cerris L., etc., P. lentiscus L., R. palaestinus Boiss. (R. lycioides L.), R. alaternus L., Z. Spina-christi L., A. spinosa L., R. palaestinum Feinbrun, A. foetida L., C. abyssinica Kunth and Bouche, L. barbarum L., L. europaeum L., L. depressum Stocks, L. schweinfurthii Dammer, L. shawii Roem. and Schult., S. sinaicum Boiss., S. incanum L., P. pungens Willd., P. brachyodon (Boiss.) Zohary, P. chrysophylla Boiss., B. arabica (Boiss.) Maire and Weiller, P. platystegia Post., P. viscosa Poiret., S. dominica L., S. lanigera Poir., S. thymbra L., S. thymbrifolia Hedge and Feinbrun, S. palaestina L., S. fruticosa Miller, S. officinalis L., S. palaestina Benth., S. aethiopis L., M. fruticosa (L.) Druce., T. capitatum L., T. creticum L., T. capitata (L.) Cav., T. spicata L., B. populneus (Schott and Endl.) R.Br., C. spinosa L., C. sicula Duh., C. aegyptia Lam., A. halimus L., N. mucronata (Forssk.) Asch. and Schweinf., H. persicum Bunge, H.negevensis (Iljin and Zohary) L. Boulos, A. macrostachyum (Moric.) K. Koch, A. javanica (Burm.f.) Juss. ex Schult., S. fruticosa (L.) A. J. Scott, S. palaestina Eig. and Zohary, H. lancifolius (Boiss.) Kothe-Heinr., H. salicornicum (Moq.) Bunge ex Boiss., O. natrix L., L. nobilis L., P. aquilinum (L.) Kuhn, M. azedarach L., P. mascula (L.) Miller, A. filiculoides Lam., L. pyrotechnica (Forssk.) Decne., S. officinalis L., A. aleppica DC., G. tournefortii L., A. arborescens L., A. monosperma Delile, A. garcinii (Burm.f.) DC., P. dioscoridis (L.) DC., A. sieberi Besser., A. horridus L., A. palaestinus Baker, G. villosa Willd, E. aphylla Forskal, E. foeminea Forssk, A. halimus L., A. setifera Moq., A. syriaca Iljin, A. orientalis (L.) Boiss., A. strigosa Boiss. and Hohen., A. tinctoria (L.) Tausch, A. altissima (Miller) Swingle, R. chalepensis L., T. hirsuta (L.) Endl., V. eremobium Murb., V. fruticulosum Post., H. helix L., E. crassifolium L’Her., E. glaucophyllum (L.) L’Hér., E. arborescens (Desf.) Willd., E. acaule (L.) Becherer and Thell., E. creticum Lam., E. falcatum F. Delaroche, E. glomeratum Lam., E. maritimum L., E. cannabinum L., E. hierosolymitana Boiss., E. hirta L., E. hirsuta L., E. terracina L., B. aegyptiaca (L.) Delile, Z. dumosum Boiss., F. bruguieri DC., F. mollis Delile, F. orientalis C. Presl., F. arabica L., C. arabica (Boiss.) Diagn. Pl. Orient, C. lanatus Vahl., C. colocynthis (L.) Schrader, C.s dorycnium L., I. cairica (L.) Sweet, I. imperati (Vahl.) Griseb., H. aureus L., P. orientalis (L.) Feinbrun, M. myrtifolia Boiss. et Hohen., M. nervosa (Desf.) Benth., C. insulare (Candargy) Govaerts, E. cannabinum L., D. bovei (DC.) Anderb., H. sanguineum (L.) Kostel., I. maris-mortui Feinbrun, C. iphionoides (Boiss. and Blanche) Brul., C tinctoria (L.) J. Gay, C. reuteriana Boiss., C. syriaca Boiss., E. philistaeus Feinbrun and Zohary, V. vilosa Roth., F. thymifolia (L.) Webb., G. canum Req. ex DC., G. elongatum C. Presl., G. humifusum M. Bieb., C. acutum L., E. glomeratum Poir., E. fruticosum Desf., E. angustifolium Mill., P. orientalis (L.) Feinbrun, H. bacciferum Forssk., H. arbainense Fresen., M. ciliata (Forskal) I. M. Johnston, C. creticum Mill., F. vulgare Miller, F. biverticillata J. Thieb, F. communis L., F. orientalis L., F. tingitana L., F. syriaca Boiss., C. maculatum L., F. clypeata (L.) Medik, F. eriocarpa (DC.) Boiss., D. harra (Forssk.) Boiss., E. crassipes Fisch. and C. A. Mey., F. bisumbellata (Forssk.) Bubani, F. tenacissima L., V. cruciatum Sieber ex. Boiss., G. arabicum Fresen., G. flavum Crantz, G. grandiflorum Boiss. and A. Huet., H. micranthus L., H. hemistemon J. Gay, H. bulbosum L., F. arundinacea Schreb., H. triquetrifolium Turra, A. parvifolia Sm., I. palaestina (Baker) Boiss., J. unilateralis (Roem. and Schult.) O’Donell, K. aegyptiaca (L.) Nabelek, K. judaica Danin, L. nudicaulis (L.) Hooker fil., L. tuberosus L., L. bicolor (Boiss.) Eig. and Feinbrun, L. pyrotechnica (Forssk.) Decne., F. ferruginea (L.), V. tiberiadis Boiss., V. sinaiticum Benth., V. galilaeum Boiss., V. jordanicum Murb., V. gaillardotii Boiss., V. officinalis L. and V. luteola (Jacq.) Benth. species. Additionally, the community has 23 (7.84%) endemic species, including the following endemic species: R. palaestinus Boiss., P. palaestina Boiss., A. ramonensis Danin, P. syriaca Boiss. and T. palaestina Bertol., accompanied by C. arizonica Greene and some Cupressus species. Forests grew in thermomediterranean–mesomediterranean thermotype regions and dry to humid environments in the soil of carbon substrates, such as brown ruinsenas and light rendzina (terra rossa), with an almost neutral pH, and were habituated in the Mediterranean woodlands, shrub lands and relict maquis trees [16,17,18,19,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62]. The slope was 10–30%, with a plant cover rate of 70%, an average altitude of 314 m and a vegetation height of 9–15 m (12 m) (Table 2). The distributions for life forms of this association are: 251 species, of which 96 (38.09 %) were phanerophytes trees (67), phanerophytes shrubs (15), phanerophytes shrub climbers (3), phanerophytes shrub vines (3), phanerophytes dwarf shrubs (3) and phanerophytes (5); 47 were shrubs, (18.65%) as shrubs (28), chamaephyte semi-shrubs (18) and a chamaephyte shrub climber (1); 48 were chamaephytes (19.04%), as chamaephytes (46), a chamaephyte parasite (1) and a chamaephyte–hemicryptophyte–annual (1); 51 were hemicryptophytes (20.23%), as hemicryptophytes (51) and a hemicryptophyte climber (1); 5 were geophytes (1.98%), as geophytes (4) and a geophyte vine (1); and 3 were helophytes (1.19%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cupresso sempervirentis–Pinetum halepensis ass. nova.

These give us an indication that suggests that association one lies in the Asian regions of the Eastern Mediterranean, and thermomediterranean to mesomedoterranean thermotypes: Cupresso sempervirentis—Pinetum halepensis ass. nova. (Figure 2C; Table 2: ASL 1- Inv. 1, 2, 8, 11 and 12, typus inv. 1).

Percentage of plant species present in the sample studies and communities: V = 100%, IV = 60.1–80%, III = 40.1–60%, II = 20.1–40% and I = 0.1–20%. N: native, E: endemic, Sh: shrub, ASL: association and ASL2: association 2.

3.2. Forest Maquis, Macchie and Steppe Vegetation

3.2.1. Pistacio lentisci–Quercetum calliprini ass. nova

The second association consisted of the forest group (inventories 3, 4, 6, 7, 9, 10 and 5), represented by Quercus genus as Q. calliprinos Webb. (Q. palaestina K., Oak Palestine) [63,64], Q. inthaburensis Decne., Q. infectoria Olivier, Q. boissieri Reut. and Q. cerris L. Additionally, in May 2018 several new varieties of oak were identified, including Q. suber L., Q. ilex L. and Q. robur L., in addition to common oak species, when the geographic information system (GIS) platform technology was used in various areas of occupied Palestine in 1948 by Ezra Barnea [65]. Rhamnus and Pistachio genus, as species of P. lentiscus L., R. palaestinus Boiss. (R. lycioides L.), R. alaternus L., Z. Spina-christi L. Desf. and Z. Lotus (L.) Lam., are heavy forest plains with 37 endemic plants (12.75%), including: R. palaestinus Boiss., P. palaestina Boiss, Q. look Kotschy, A. andrachne L., B. philistaea Bornm., A. obtusifolium Sm., T. palaestina Bertol. and A. ramonensis Danin, accompanied by R. palaestinus Boiss., C. siliqua L. and others Quercus species. The forest or community is in steppe environments that are part of a large area of uneven flat grassland in Southeast Europe and the western Mediterranean, with dry and semi-arid areas and an inframediterranean to thermomediterranean thermotype [16,17,18,19]. The slope is 5–25%, with an average vegetation height of 8.5 m, an average altitude of 272.8 m and a soil type of limestone and terra rosa. The distributions of life forms for this association are: 113 (38.96%) phanerophytes (trees), 109 (37.58%) shrubs and chamaephytes, 55 (17.93%) hemicryptophytes, 9 (2.94%) geophytes and 4 (1.30%) helophytes. This suggested to us that the association is Pistacio lentisci–Quercetum calliprini ass. nova. hoc loco. (Figure 2C,D; Table 3: ASL 2- Inv. 3, 4, 6, 7, 9, 10 and 5).

Table 3.

Association 2. Pistacio lentisci—Quercetum calliprini ass. nova.

The main forests are found in the various mountains and highlands of Palestine, stretching from the heights of the Hebron Mountains in the south to Ras Al-Naqoura, Galilee and Safed in the north. In most of these areas cultivated plants have replaced natural plants for several centuries.

These results show that the study area lies within the region between the Mediterranean Sea and West Asia, and botanists divide Palestinian flora into eight distinct groups, which are: Mediterranean, Eurasia, Euro-Siberian, Irano-Turanian, Sudano-Zambesian, Saharo-Arabian, Americas, Australia and South Africa, as well as plants that grow in Palestine [16,63,64].

Furthermore, the great difference between the pine forests of Pinus halepensis Miller of the western Mediterranean with those existing in Palestine allows us to propose the new alliance Cupresso sempervirentis–Pinus halepensis, with an eastern Mediterranean distribution and dry thermomediterranean environments. As a typus of the Cupresso sempervirentis-Pinus halepensis alliance we chose the association Cupresso sempervirentis–Pinetum halepensis ass. nova. The alliance was characterized by P. Pinea L., P. brutia Tenore, C. sempervirens L. C. arizonica Greene, T. occidentalis L., J. phoenicea L., J. excelsa M. Bieb. and J. drupacea Labill. [66,67,68].

The syntaxonomical interpretation of these associations is shown below:

- 1.

- Forest vegetation:Class: Quercetea ilicis Br.-Bl. ex. A. and O. Bolòs 1950 [69].Order: Pinetalia halepensis Biondi, Blasi, Galdenzi, Pesaresi et Vagge in Biondi et al. [27] (2014).Alliance: Cupresso sempervirentis—Pinus halepensis all. nova.Typus of alliance: Ass. Cupresso sempervirentis—Pinetum halepensis ass. nova.

- 2.

- Maquis, macchie and steppe vegetation:Class: Quercetea calliprini or palaestini nova.Order: Quercetalia calliprini Zohary [64] 1960.Alliance: Querco—Pistacion lentisci all. nova.Association: Pistacio lentisci—Quercetum calliprini ass. nova.

Moreover, forests of pines are found on different geological formations in the world, including in the Mediterranean, Europe and different regions in the Palestine mountains. P. halepensis Miller, P. Pinea L., P. canariensis C. Smith, P. brutia Tenore and Cupressus genus as C. sempervirens L., C. arizonica Greene, T. occidentalis L., J. phoenicea L., J. excelsa M. Bieb. and J. drupacea Labill, C. equesitifolia L., C. sempervirentis and P. halepensis associations have been described by many researchers in antecedent studies [16,17,18,19]. Phytogeographically, plant associations belonging to the forest flora that extend over Europe, the Mediterranean and from the north to the south of Palestine were included within the classes of Quercetea ilicis [69]. Pine and Cupressus forests are placed under two different alliances: the order Pinetalia halepensis, Biondi et al. 2014 [27], and the alliance Juniperon phoeniceae–Pinus acutisquamae and Quercetea ilicis [65]. The components of the alliance of the Pinus halepensis [64] order of Pinetalia halepensis [27] are apparent in this association due to the range of anthropogenic harm to the forest steppes and mountain zones as a result of some military activities for the purpose of training and fire, in addition to the existence of numerous plants that return to this association.

3.2.2. Pistacio lentisci—Quercetum calliprini ass. nova

The second association includes represented inventories (3, 4, 6, 7, 9, 10 and 5) of the principal component analysis in (Table 3, typus inv. 1); the community grows in areas of the Beit Jibrin in the dry, infra- and thermotropical thermotypes. This association is a composition of Q. calliprinos Webb. (Oak Palestine, Q. palaetina Kotschy), Q. inthaburensis Decne., Q. infectoria Olivier, Q. boissieri Reut., Q. cerris L., A. obtusifolium smith, A. monspessulanum L., Q. libani G. Olivier, Q. look Kotschy, Q. boissieri Reut., and P. lentiscus L. P. palaestina Boiss., accompanied with R. palaestinus Boiss., R. disperma Ehrenb. ex Boiss., R. alaternus L., C. siliqua L. and P. khinjuk Stocks species, and it belong to Mediterranean macchie vegetation, evergreen Mediterranean forests and deciduous Mediterranean forests. The soil of this association has a partially basic character, low organic matter and a medium of clayey–loamy texture. Due to the high degradation, numerous steppes and xerophilous species permeated into the floristic structure of this association. Quercus as Oak extends from the eumediterranean and submediterranean regions (Quercetalia ilicis), according to a Braun-Blanquet rating [69,70,71,72,73], and many Quercus species, such as Q. calliprinos Webb., Q. inthaburensis Decne, Q. infectoria Olivier, Q. libani G. Olivier, Q. look Kotschy and Q. boissieri Reut. associations were qualified in neighboring regions and studied. Likewise, the Quercus genus association described in Palestine in the highland mountains and west of Hebron [16,17,18,19] was categorized under the Quercetalia calliprini order. The floristic structure of this association is well-specified by the characteristic species of the order Quercetalia calliprini [63] and a new class, Quercetea calliprini or palaestini. For these causes, the association must be included in the syntax unity aforementioned. However, the second association is dominated by Q. calliprinos Webb. (Q. palaestina Kotschy or Q. coccifera L.), Q. inthaburensis Decne., Q. infectoria Olivier, Q. boissieri Reut., Q. cerris L., Q. look Kotschy, Q. libani G. Olivier, C. siliqua L., S. junceum L., C. siliquastrum L., P. gillesii Hook, A. salicina Lindl., A. cyanophylla Lindl., C. equesitifolia L., S. japonica L., C. villosa (Poir.) Link, R. raetam (Forssk.) Webb. and Berthel., G. monspessulana (L.) O. Bolós and Vigo., A. radiana Savi., P. palaestina Boiss., P. khinjuk Stocks, P. lentiscus L., P. saportae Burnat., P. atlantica Desf., P. terebinthus L., P. vera L., S. molle L., R. coriaria L., R. palaestinus Boiss., (R. lycioides L.), R. alaternus L., Z. Spina-christi L. Desf., Z. Lotus (L.) Lam., P. spina-christi Miller, Z. jujuba Miller, S. tripartita (Ucria) Moffett, S. thea (Osbeck) M.C. Johnst., M. germanica L., C. azarolus L., A. communis L, C. oriana (L.) DC., S. spinosum (L.) Spach, P. syriaca Boiss., C. monogyna Jacq., M. communis Desf., P. coccinea M. Roem., P. spinosa L., F. retusa L., F. sycomorus L., F. cariaca L., M. alba L., M. nigara L., O. europaea L., P. media L., O. oleaster Hoffmanns. and Link, A. obtusifolium Sm. or A. syriscum Boiss., A. monspessulanum L., F. retusa L., F. sycomorus L., F. cariaca L., M. alba L., M. nigara L., O. ficus-indica (L.) Miller, O. robusta J.C. Wendl., O. ficus-barbarica A. Berger, S. alba L., P. alba L., P. nigra L., P. euphratica Oliver, etc.

Forest oaks and maquis evergreen vegetation, such as Q. calliprinos Webb. (Q. palaestina K.), Q. inthaburensis Decne, Q. infectoria Olivier, Q. boissieri Reut., Q. cerris L., P. palaestina Boiss., R. coriaria L., C. siliqua L., S. junceum L., P. gillesii Hook, A. salicina Lindl., A. cyanophylla Lindl., S. japonica L., R. raetam (Forssk.) Webb. and Berthel., G. monspessulana (L.) O. Bolós and Vigo, A. radiana Savi. and O. europaea L., a forest growing in a granular climate community in a habitat, include Mediterranean scrubs, steppes, grasslands, desert oases, urban areas, forest and canyons environments with dry sub-humid regions and an infrared thermal Mediterranean pattern to the mesomediterranean, on limestone composed of grain skeletal fragment organisms and organic matter. Therefore, the floristic arrangement of this association (Ceratonia and Quercus species) in the Mediterranean and Middle East regions extends from the eumediterranean to the Eurasian regions (Quercetalia ilicis), corresponding to its Braun-Blanquet rating [69,70,71,72,73]. Several Quercus and Ceratonia species, such as Q. look Kotschy, Q. boissieri Reut., Q. calliprinos (Q. coccifera L. or Q. palaestina K.), C. siliqua L. [74]., S. junceum L., P. gillesii Hook, A. salicina Lindl., A. cyanophylla Lindl., R. raetam (Forssk.) Webb. and Berthel. and A. radiana Savi. associations were discovered in neighboring regions and studied [16,17]. In the same way, the Quercus and Ceratonia species, such as the Q. look Kotschy and C. siliqua L. associations described in Southern Palestine, as well as to the west of the Hebron area by Ighbareyeh et al. [16], were proposed a new classification under the Quercetalia calliprini order and Querco-istacion lentisci alliance. Consequently, the floristic makeup of this association is well-identified by the specific species of the Quercetalia calliprini order and the Quercetea calliprini or palaestini class; for these causes, the association must be included in the syntaxa unity mentioned. Furthermore, we suggested a new alliance (Querco–Pistacion lentisci), order (Quercetalia calliprini) [64] and class (Quercetea calliprini or Quercetea palaestini), in addition to the Quercetalia ilicis order. The following are diagnostic class species (subordinated units) and vascular plants: Q. calliprinos Webb. (Q. palaestina K.), Q. inthaburensis Decne., Q. infectoria Olivier, Q. boissieri Reut., Q. cerris L., Q. look Kotschy, Q. libani G. Olivier, C. siliqua L., S. junceum L., C. siliquastrum L., P. gillesii Hook, A. salicina Lindl. A. cyanophylla Lindl., S. japonica L., C. villosa (Poir.) Link, R. raetam (Forssk.) Webb. and Berthel., G. monspessulana (L.) O. Bolós and Vigo, A. radiana Savi., P. palaestina Boiss., P. khinjuk Stocks, P. lentiscus L., P. saportae Burnat., P. atlantica Desf., P. terebinthus L., P. vera L., S. molle L., R. coriaria L., R. palaestinus Boiss. (R. lycioides L.), R. alaternus L., Z. Spina-christi L. Desf., Z. Lotus (L.) Lam., P. spina-christi Miller, Z. jujuba Miller, S. tripartita (Ucria) Moffett, S. thea (Osbeck) M.C.Johnst., M. germanica L., C. azarolus L., A. communis L., C. oriana (L.) DC., S. spinosum (L.) Spach, P. syriaca Boiss., C. monogyna Jacq., M. communis Desf., P. coccinea M. Roem., P. spinosa L., F. retusa L., F. sycomorus L., F. cariaca L., F. benjamina L.. M. alba L., M. nigara L., O. europaea L., P. media L., O. oleaster Hoffmanns. and Link, A. obtusifolium Sm. or A. syriscum Boiss., A. monspessulanum L., P. halepensis Miller, P. P. L., P. canariensis C. Smith, P. brutia Tenor, C. sempervirens L., C. sempervirens L. var. horizontalis Miller, C. arizonica Greene, T. occidentalis L., J. phoenicea L., J. excelsa M. Bieb., J. drupacea Labill., A. monspessulanum L., F. retusa L., F. sycomorus L., F. cariaca L., M. alba L., M. nigara L., O. ficus indica (L.) Miller, O. robusta J.C. Wendl., O. ficus-barbarica A. Berger, S. alba L., P. alba L., P. nigra L., P. euphratica Oliver, etc.

On the other hand, for the flora and vegetation, we found more than 72 families and 800 species of plants including forest oak, maquis, woodland, scrub evergreen, macchie and steppe land Quercus species, such as Q. calliprinos Webb. (Q. palaestina k., Q. inthaburensis Decne., Q. infectoria Olivier, Q. cerris L., etc., and the Pistachio genus, such as species of P. lentiscus L., R. palaestinus Boiss. (R. lycioides L.), R. alaternus L., Z. Spina-christi L. and many macchie and steppes, shrubs, herbaceous and landscape vegetation, such as A. spinosa L., R. palaestinum Feinbrun, A.s foetida L., C. abyssinica Kunth and Bouche, L. barbarum L., L. europaeum L., N. glauca Graham, L. depressum Stocks, L. schweinfurthii Dammer, L. shawii Roem. and Schult., S. sinaicum Boiss., S. incanum L., P. pungens Willd., P. brachyodon (Boiss.) Zohary, P. chrysophylla Boiss., B. saxatilis Sieber ex. C. Presl., B. philistaea Bornm., B. undulata (Sieber ex Fresen.) Bentham, B. arabica (Boiss.) Maire and Weiller, P. platystegia Post., P. viscosa Poiret., S. eigii Zohary, S. dominica L., S. lanigera Poir., S. thymbra L., S. thymbrifolia Hedge and Feinbrun, S. palaestina L., S. fruticosa Miller, S. officinalis L., S. aegyptiaca L., S. palaestina Benth., S. aethiopis L., M. fruticosa (L.) Druce., T. capitatum L., T. creticum L., T. capitata (L.) Cav., T. spicata L., B. populneus (Schott and Endl.) R.Br., J. mimosaefolia D. Don., C. spinosa L., C. sicula Duh., C. aegyptia Lam., C. australis L., A. halimus L., N. mucronata (Forssk.) Asch. and Schweinf., H. persicum Bunge, H. negevensis (Iljin and Zohary) L. Boulos, S. fruticosa (L.) L., A. javanica (Burm.f.) Juss. ex Schult., S. imbricata Forssk., S. cyclophylla Baker, A. macrostachyum (Moric.) Piirainen and G. Kadereit, S. palaestina Eig. and Zohary, H. lancifolius (Boiss.) Kothe-Heinr., H. salicornicum (Moq.) Bunge ex Boiss., O. natrix L., A. andrachne L., L. nobilis L., P. aquilinum (L.) Kuhn, M. azedarach L., P. mascula (L.) Miller, A. filiculoides Lam., L. pyrotechnica (Forssk.) Decne., S. officinalis L., A. aleppica DC., G. tournefortii L., A. arborescens L., A. monosperma Delile, A. garcinii (Burm.f.) DC., P. dioscoridis (L.) DC., A. sieberi Besser., A. horridus L., A. palaestinus Baker, S. asperan L., P. aculeata L., O. baccatus Delile, N. oleander L., C. acutum L., P. aphylla Decne., M. peregrina (Forssk.) Fiori, G. villosa Willd, E. aphylla Forskal, E. foeminea Forssk., A. halimus L., A. setifera Moq., A. syriaca Iljin, A. orientalis (L.) Boiss., A. strigosa Boiss. and Hohen., A. galilaea Boiss., A. tinctoria (L.) Tausch, A. altissima (Miller) Swingle, R. tinctorum L., R. tenuifolia D’Urv., R. chalepensis L., T. hirsuta (L.) Endl., V. eremobium Murb., V. fruticulosum Post., H. helix L., E. crassifolium L’Her., E. glaucophyllum (L.) L’Hér., E. arborescens (Desf.) Willd., E. acaule (L.) Becherer and Thell., E. creticum Lam., E. falcatum F. Delaroche, E. glomeratum Lam., E. maritimum L., E. cannabinum L., E. hierosolymitana Boiss., E. hirta L., E. hirsuta L., E. terracina L., B. aegyptiaca (L.) Delile, Z. dumosum Boiss., N. retusa (Forssk.) Ascherson, F. bruguieri DC., F. mollis Delile, F. orientalis C. Presl., Fagonia arabica L., C. arabica (Boiss.) Diagn. Pl. Orient, C. lanatus Vahl., C colocynthis (L.) Schrader, C. dorycnium L., I. cairica (L.) Sweet, I. imperati (Vahl.) Griseb., H. aureus L., P. orientalis (L.) Feinbrun, M. myrtifolia Boiss. et Hohen., M. nervosa (Desf.) Benth., C. insulare (Candargy) Govaerts, E. cannabinum L., Doellia bovei (DC.) Anderb., H. sanguineum (L.) Kostel., I. maris-mortui Feinbrun, C. iphionoides (Boiss. and Blanche) Brul., C. tinctoria (L.) J. Gay, C. hierosolymitana Boiss., C. reuteriana Boiss., C. syriaca Boiss., E. philistaeus Feinbrun and Zohary, V. vilosa Roth., F. thymifolia (L.) Webb., C. creticus L., G. canum Req. ex. DC., G. elongatum C. Presl., G. humifusum M. Bieb., C. acutum L., E. glomeratum Poir., E. fruticosum Desf., E. angustifolium Mill., H. maris-mortui Zohary, P. orientalis (L.) Feinbrun, H. bacciferum Forssk., H. arbainense Fresen., M. ciliata (Forskal) I. M. Johnston, H. rotundifolium Lehm., C. creticum Mill., M. canescens Boiss., N. marina var. intermedia (Wolfg. ex Gorski) Rendle, D. triradiata Hochst. Ex. Boiss., F. vulgare Miller, F. biverticillata J. Thieb, F. communis L., F. orientalis L., F. tingitana L., F. syriaca Boiss., C. maculatum L., F. clypeata (L.) Medik, F. eriocarpa (DC.) Boiss., D. harra (Forssk.) Boiss., E. crassipes Fisch. and C. A. Mey., F. bisumbellata (Forssk.) Bubani, F. tenacissima L., V. cruciatum Sieber ex. Boiss., G. arabicum Fresen., G. flavum Crantz, G. grandiflorum Boiss. and A. Huet., V. agnus-castus L., G. arabica Jaub. and Spach, H. micranthus L., H. hemistemon J. Gay, H. bulbosum L., F. arundinacea Schreb., H. triquetrifolium Turra, A. parvifolia Sm., I. atrofusca Baker, I. atropurpurea Baker, I. palaestina (Baker) Boiss., I. vartanii Foster, G. italicus Miller, J. acutus L., J. articulates L., J. subulatus Forssk., J. unilateralis (Roem. and Schult.) O’Donell, K. aegyptiaca (L.) Nabelek, K. judaica Danin, L. nudicaulis (L.) Hooker fil., L. tuberosus L., L. bicolor (Boiss.) Eig. and Feinbrun, L. pyrotechnica (Forssk.) Decne., F. ferruginea (L.), V. tiberiadis Boiss., V. sinaiticum Benth., V. galilaeum Boiss., V. jordanicum Murb., V. gaillardotii Boiss., V. officinalis L., V. luteola (Jacq.) Benth., C. monogyna Vahl., C. epithymum (L.), C. pedicellata Ledeb., C. planiflora Ten., C. palaestina Boiss. and many other species. For the Quercetalia calliprinii order [63], we found characteristic species such as Quercus spp., Q. calliprinos Webb. or Q. palaestina K., Q. inthaburensis Decne., Q. boissieri Reut., Q. infectoria Olivier, Q. cerris L., Q. look Kotschy, Q. libani G. Olivier, C. siliqua L., S. junceum L., F. cariaca L., M. alba L., M. nigara L., O. ficus indica (L.) Miller, C. siliquastrum L., P. gillesii Hook, A. cyanophylla Lindl., S. japonica L., C. villosa (Poir.) Link, etc. Species characteristic of the alliance (Querco–Pistacion lentisci) were also found, such as P. lentiscus L., P. palaestina Boiss., P. khinjuk Stocks, P. saportae Burnat., P. vera L., P. atlantica Desf., P. terebinthus L., S. molle L., R. coriaria L., R. palaestinus Boiss. (R. lycioides L.), R. alaternus L., Z. Lotus (L.) Lam., Z. Spina-christi L. Desf., P. spina-christi Miller, Z. jujuba Miller, S. tripartita (Ucria.) Moffett., S. thea (Osbeck) M.C.Johnst., M. germanica L., C. azarolus L., A. communis L, C. oriana (L.) DC., S. spinosum (L.) Spach, P. syriaca Boiss., C. monogyna Jacq., M. communis Desf., P. coccinea M. Roem., P. spinosa L., F. retusa L., F. sycomorus L., F. cariaca L., M. alba L., M. nigara L., O. europaea L., P. media L., O. oleaster Hoffmanns. and Link, A. obtusifolium Sm. or A. syriscum Boiss., A. monspessulanum L., etc.

However, the ecological characteristics, chorotypes, habitats, climatology and plant geography distributions in this proposed class have been studied, as shown in the fourth table (Table 4), where the plants are distributed into deserts, shrub-steppes, semi-steppe shrublands and Mediterranean woodlands and shrublands, in addition to Mediterranean maquis and forests.

Table 4.

Ecological and habitat characteristics of distributed plants.

Although Beit Jibrin rises slightly above sea level, it represents a unique pattern of forest vegetation and biodiversity. It is rich in endemic plants, which are estimated to account for about 37 (12.75%) endemic species of the total plants, home to more than 290 species of plants, including forests, oak, steppes, copses and high shrub lands. Therefore, they are part of the mountain highland plants, as in the highlands that extend from the southernmost point of Hebron to the north of Palestine, such as Jenin, Safed and Galilee; Palestinian coast plants and the Mediterranean basin region, such as Jabal Al-Sheikh, Jaffa, Acre, Haifa, Nazareth and Ashdod; savannah plants; and other African desert plants, such as Sinai and the Red Sea area. However, Beit Jibrin represents forest plants found in West Asia, the Mediterranean region, North Africa and the Palestinian coast. Beit Jibrin has an infra-thermomediterranean thermotype and a dry ombrotype. In this study, two new plant groups were identified in the Beit Jibrin area: Cupresso sempervirentis—Pinetum halepensis ass. nova and Pistacio lentisci—Quercetum calliprini ass. nova.

The suggested syntaxonomical scheme for this study is:

Class: Quercetea ilicis Br.-Bl. ex. A. and O. Bolòs 1950 [69]

Order: Pinetalia halepensis Biondi et al. (2014) [27]

Alliance: Cupresso sempervirentis—Pinus halepensis all. nova

Cupresso sempervirentis—Pinetum halepensis ass. nova

Class: Quercetea ilicis Br.-Bl. ex. A. and O. Bolòs 1950 [62]

Class: Quercetea calliprini or palaestini nova.

Order: Quercetalia calliprini Zohary 1960 [64]

Alliance: Quercion calliprini Zohary 1955, 1960 [63,64]

Pistacio lentisci—Quercetum calliprini ass. nova

Syntaxonomical scheme:

Class: Quercetea ilicis Br.-Bl. ex A. Bolòs et O. de Bolòs in A. Bolòs y Vayreda 1950 [69]

Order: Quercetalia ilicis Br.-Bl. ex Molinier 1934 [70]

Quercetalia calliprini Zohary 1955, 1960 [63,64]

Alliance: Ceratonio–Pistacion lentisci Zohary ex Zohary et Orshan 1959 [74]

Associations:

-Pistacio palaestinae–Quercetum lokii* (Ighbareyeh et al., 2014) [16]

-Capparido sinaicae–Ceratonietum siliquae (Ighbareyeh et al., 2014) [16]

-Cerasus microcarpae–Quercetum ithaburensis * (Ighbareyeh et al., 2014) [16]

-Pyro siriacae–Abietetum cilicicae * (Ighbareyeh et al., 2014) [16]

-Abio ciliciae–Ceratonietum siliquae (Ighbareyeh et al., 2014) [16]

-Periploco aphylli–Pinetum halepensis (Ighbareyeh et al., 2014) [16]

-Cytisopsis pseudocytiso–Tamaricetum tetragynae (Ighbareyeh et al., 2014) [16]

-Crataego sinaicae–Tamaricetum jordanii (Ighbareyeh et al., 2014) [16]

Class: Quercetea ilicis Br.-Bl. ex A. Bolòs et O. de Bolòs in A. Bolòs y Vayreda 1950 [62]

Order: Quercetalia calliprini Zohary 1955, 1960 [62,63]

Alliance: Ceratonio–Pistacion lentisci Zohary ex Zohary et Orshan 1959 [74]

Associations:

-Pino halepensis–Quercetum lookii* (Ighbareyeh et al., 2018) [75]

-Pistacio palaestinae–Ceratonietum siliquae*(Ighbareyeh et al., 2018) [75]

-Quercus libanii–Tamaricetum palaestineae* (Ighbareyeh et al., 2018) [75]

Class: Quercetea ilicis Br.-Bl. ex A. Bolòs et O. de Bolòs in A. Bolòs y Vayreda 1950 [62]

Order: Quercetalia calliprini Zohary 1955, 1960 [63,64]

Alliance: Pistacio–Quercion lokii (Ighbareyeh et al., 2021) [19]

Ceratonio siliquae—Quercion calliprinae (Ighbareyeh et al., 2021) [19]

Pino halepensis–Cupression sempervirenti (Ighbareyeh et al., 2021) [19]

Associations:

-Pistacio lentisci–Quercetum lokii (Ighbareyeh et al., 2021) [19]

-Ceratonio siliquae–Quercetum callipinii. (Ighbareyeh et al., 2021) [19]

-Pino halepensis–Cupressetum sempervirentis (Ighbareyeh et al., 2021) [19]

* Associations in which olive cultivation is possible.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: J.M.H.I. and E.C.; data curation: J.M.H.I., A.C.-O., and E.C.; formal analysis: E.C.; investigation: J.M.H.I. and E.C.; methodology: E.C. and A.C.-O.; project administration: E.C.; resources: E.C.; supervision: J.M.H.I., A.C.-O. and E.C.; validation, J.M.H.I., A.C.-O. and E.C.; software: J.M.H.I. and E.C.; visualization: E.C., A.C.-O. and J.M.H.I..; writing—original draft: J.M.H.I. and E.C.; writing—review and editing: J.M.H.I., A.C.-O., and E.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work does not have funds for its publication, only a small help from the University of Jaén, Spain.

Acknowledgments

This work is the result of the first author’s doctoral thesis, directed at the University of Jaén.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jehad, M.H.I.; Suliemieh, A.A.A.; Ighbareyeh, M.M.H.; Cano-Carmoma, E.; Cano-Ortiz, A. Olive (Olea europaea L.) of Jerusalem in Palestine. Trends Tech. Sci. Res. 2019, 3, 555617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ighbareyeh, J.M.H.; Cano-Ortiz, A.; Cano, E. Case study: Analysis of the physical factors of Palestinian bioclimate. Am. J. Clim. Chang. 2014, 3, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ighbareyeh, J.M.H. Effect of environmental factors on Apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) yield in the city of Jerusalem occupied, Palestine. Asian J. Res. Agric. For. 2021, 7, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohary, M. Plant Life of Palestine; Ronald Press Company: New York, NY, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Zohary, M. Flora Palaestina 1966; Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities: Jerusalem, Israel, 1966; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Zohary, M. Flora Palaestina. Part 1, Text Equisetaceae to Moringaceae; Israel Academy of Science and Humanities: Jerusalem, Israel, 1966; p. 346. [Google Scholar]

- Zohary, M. Flora Palaestina 1972; Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities: Jerusalem, Israel, 1972; Volume II. [Google Scholar]

- Zohary, M. Geobotanical Foundations of the Middle East; Gustav Fisher Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 1973; Volumes I and II, p. 739. [Google Scholar]

- Zohary, M. Flora Palaestina 1986; Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities: Jerusalem, Israel, 1986; Volume IV. [Google Scholar]

- Zohary, M. Flora Palaestina 1987; Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities: Jerusalem, Israel, 1987; Volume III. [Google Scholar]

- Dothan, F.N. Flora Palaestina, Part Three, Text Ericaceae to Compositae; Israel Academy of Science and Humanities: Jerusalem, Israel, 1978; p. 481. [Google Scholar]

- Dothan, F.N. Flora Palaestina, Part Four Plates, Text Alismtaceae to Orchidaceae; Academy of Science and Humanities: Jerusalem, Israel, 1986; p. 525. [Google Scholar]

- Danin, A.; Feinbrun-Dothan, N. Analytical Flora of Eretz-Israel; CANA Publishing House Ltd.: Jerusalem, Israel, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Danin, A. The inclusion of adventive plants in the second edition of Flora Palaestina. Willdenowia 2004, 30, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danin, A. Distribution Atlas of Plants in Flora Palaestina Area, 2nd ed.; Academy of Science and Humanities: Jerusalem, Israel, 2004; p. 520. ISBN 9652081671. [Google Scholar]

- Ighbareyeh, J.M.H.; Cano-Ortiz, A.; Suliemieh, A.A.A.; Ighbareyeh, M.M.H.; Cano, E. Phytosociology with other characteristic biologically and ecologically of plant in Palestine. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 3104–3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ighbareyeh, J.; Cano-Ortiz, A.; Carmona, E.; Suliemieh, A.; Ighbareyeh, M. Flora endemic rare and bioclimate of Palestine. Open Access Libr. J. 2017, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ighbareyeh, J.M.H.; Cano-Ortiz, A.; Cano, E. Endemic plant species in the west of Hebron, Palestine. Eur. J. Appl. Sci. 2021, 9, 368–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ighbareyeh, J.M.H.; Suliemieh, A.A.-R.A.; Abu Ayash, A.M.; Sheqwara, M.N.; Ortiz, A.C.; Carmona, E.C. Biodiversity and phytosociological analysis of plants in wadi Al-Quf nursery reserve North–Western of Hebron City in Palestine. J. Plant Sci. 2021, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercanlı, I.; Günlü, A.; Şenyurt, M.; Keleş, S. Artificial neural network models predicting the leaf area index: A case study in pure even-aged Crimean pine forests from Turkey. For. Ecosyst. 2018, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Latorre, A.V.; Navas, P.; Navas, D.; Gil, Y.; Cabezudo, B. Datos sobre la flora y la vegetación de la Serranía de Ronda (Málaga, España). Acta Bot. Malacit. 1998, 23, 149–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Latorre, A.V.; Navas-Fernández, D.; Gavira, O.; Caballero, G.; Cabezudo, B. Vegetación del Parque Natural de Las Sierras Tejeda, Almijara y Alhama (Málaga-Granada, España). Acta Bot. Malacit. 2004, 29, 117–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, P.; Meireles, C.; Vila-Viçosa, C.; Musarella, C.M.; Pinto-Gomes, C. Best management practices to face degraded territories occupied by Cistus ladanifer shrublands—Portugal case study. Plant Biosyst. Int. J. Deal. Asp. Plant Biol. 2013, 149, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-García, F.J.; Akhani, H.; Parsons, R.F.; Silcock, J.L.; Kurt, L.; Özdeniz, E.; Spampinato, G.; Musarella, C.M.; Sánchez, E.S.; Sola, F.; et al. A first inventory of gypsum flora in the Palearctic and Australia. Mediterr. Bot. 2018, 39, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolucci, F.; Peruzzi, L.; Galasso, G.; Albano, A.; Alessandrini, A.; Ardenghi, N.M.G.; Astuti, G.; Bacchetta, G.; Ballelli, S.; Banfi, E.; et al. An updated checklist of the vascular flora native to Italy. Plant Biosyst. Int. J. Deal. Asp. Plant Biol. 2018, 152, 179–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musarella, C.M.; Mendoza-Fernández, A.J.; Mota, J.F.; Alessandrini, A.; Bacchetta, G.; Brullo, S.; Caldarella, O.; Ciaschetti, G.; Conti, F.; Di Martino, L.; et al. Checklist of gypsophilous vascular flora in Italy. PhytoKeys 2018, 103, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, E.; Blasi, C.; Allegrezza, M.; Anzellotti, I.; Azzella, M.M.; Carli, E.; Casavecchia, S.; Copiz, R.; Del Vico, E.; Facioni, L.; et al. Plant communities of Italy: The vegetation prodrome. Plant Biosyst. Int. J. Deal. Asp. Plant Biol. 2014, 148, 728–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galasso, G.; Conti, F.; Peruzzi, L.; Ardenghi, N.M.G.; Banfi, E.; Celesti-Grapow, L.; Albano, A.; Alessandrini, A.; Bacchetta, G.; Ballelli, S.; et al. An updated checklist of the vascular flora alien to Italy. Plant Biosyst. Int. J. Deal. Asp. Plant Biol. 2018, 152, 556–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalidi, W. All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948; Institute for Palestine Studies: Washington, DC, USA, 1992; ISBN 0-88728-224-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hadawi, S. Village statistics of 1945: A classification of land and area ownership in Palestine. Palest. Lib. Organ. Res. Cent. 1970, 34, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Sitta, S. The Return Journey; Palestine Land Society: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 0-9549034-1-2. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Region of the Caves & Hiding: Bet Guvrin-Maresha Archived 2017. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1370/ (accessed on 27 October 2017).

- Braun-Blanquet, J. Pflanzensoziologie. Grundzüge der Vegetationskunde, 3rd ed.; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 1964; p. 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun-Blanquet, J. Fitosociología. Bases para el Estudio de las Comunidades Vegetales; Blume: Madrid, Spain, 1979; p. 820. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Maabel, E. Transformation of cover-abundance values in phytosociology and its effects on community similarity. Plant Ecol. 1979, 39, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun-Blanquet, J.; Bolòs, O.D. Les groupements végétaux du bassin moyen de l’Ebre et leur dynamisme. An. Estac. Exp. Aula Dei 1957, 5, 1–266. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, H.; Moravec, J.; Theurillat, J.-P. International code of phytosociological nomenclature. J. Veg. Sci. 2000, 11, 739–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theurillat, J.-P.; Willner, W.; Fernández-González, F.; Bültmann, H.; Čarni, A.; Gigante, D.; Mucina, L.; Weber, H. International code of phytosociological nomenclature. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2020, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolòs, O.; De Molinier, R. Recherches phytosociologiques dans l’île de Majorque. Collect. Bot. 1958, 34, 699–865. [Google Scholar]

- Oakley, K.P. The Excavation of Goarham’s Cave. Gibraltar 1951–1954. Bull. Inst. Archaelogy 1958, 4, 1–219. [Google Scholar]

- Bolòs, O.; De Vigo, J.; Masalles, R.M.; Ninot, J.M. Manual dels Paisos Catalans; Portic: Barcelona, Spain, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Pott, R. Phytosociology: A modern geobotanical method. Plant Biosyst. Int. J. Deal. Asp. Plant Biol. 2011, 145, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, E. Phytosociology today: Methodological and conceptual evolution. Plant Biosyst. Int. J. Deal. Asp. Plant Biol. 2011, 145, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Martínez, S.; Cantó, P.; Fernández-González, F.; Sánchez-Mata, D. Revision de la clase Quercetea ilicis en Espana y Portugal: 1. Subalianza Quercenion ilicis. Folia Bot. Matrit. 1995, 15, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Martínez, S. Clasificación bioclimática de la Tierra. Folia Bot. Matritensis 1996, 16, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Martinez, S.; Sanchez, M.D.; Costa, M. North American boreal and western temperate forest vegetation (Syntaxonomical synopsis of the potential natural plant communities of North America, II. Itinera Geobot. 1999, 12, 5–316. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Martínez, S.; Fernández-González, F.; Loidi, J.; Lousã, M.; Penas, A. Syntaxonomical checklist of vascular plant communities of Spain and Portugal to association level. Itinera Geobot. 2001, 14, 5–341. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Martínez, S.; Díaz, T.E.; Fernández-González, F.; Izco, J.; Lousã, M.; Penas, A. Vascular plant communities of Spain and Portugal. Addenda to the syntaxonomical checklist of 2001. Itinera Geobot. 2002, 15, 5–432. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Martínez, S.; Biondi, E.; Costa, M.; Mossa, L. Datos sobre la vegetación de la clase Quercetea ilicis en Cerdena. Fitosociologia 2003, 40, 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Martınez, S.; Rivas Saenz, S.; Penas, A. Worldwide bioclimatic classification system. Glob. Geobot. 2011, 1, 1–634. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Martínez, S.; Penas, A.; del Río, S.; Díaz, G.T.; Rivas-Sáenz, S. Bioclimatology of the Iberian Peninsula and the Balearic Islands. In The Vegetation of the Iberian Peninsula; Loidi, J., Ed.; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2017; pp. 29–80. [Google Scholar]

- Panetsos, C.P. Natural hybridization between Pinus halepensis and Pinus brutia. Silvae Genet. 1975, 24, 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Grandos, M.; Martín-Vicente, A.; García Novo, F. Introducción del Pinus pinea en el Parque Natural de Doñana. En Actas del Seminario Sobre Reservas de la Biosfera; La Rábida: Huelva, Spain, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Galiano, E. Pasado, presente y futuro de los boques de la Península Ibérica. Acta Bot. Malacit. 1990, 15, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, L.; Aranzazu, M.; Gordo, J.; De Miguel, J.; Mutke, S.; Catalán-Bachiller, G.; Iglesias, S. Las Regiones Procedencia de Pinus pinea L; Ministerio de Medio Ambiente: Madrid, Spain, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- GIL, L. Consideraciones históricas sobre “Pinus pinaster”Aiton en el paisaje vegetal de la península ibérica. Estudios Geográficos 1991, 52, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Montes, E.; Alejandro, M.M.R.; Villalón-Torresn, D. Los pinares de pino piñonero en el sur peninsular. Papel en la dinámica natural en base a la arqueología prehistórica y protohistórica. Nuevas interpretaciones. Cuad. Soc. Esp. Cien. For. 2003, 16, 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Burrascanno, S.; Rosati, L.; Blasi, C. Plant species diversity in Mediterranean old-growth forests: A case study from central Italy. Plant Biosyst. 2009, 143, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farjon, A. Biodiversity of Pinus (Pinaceae) in Mexico: Speciation and palaeo-endemism. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1996, 121, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Latorre, A.V.; Casimiero, F.; García-Sánchez, J.; Cabezudo, B. Flora y vegetación del Paraje Natural Desfiladero de los Gaitanes y su entorno (Málaga). Acta Bot. Malacit. 2014, 39, 129–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Latorrre, A.V.; Casimiro, F.; Cabezudo, B. Flora y vegetación de la sierra de Alcaparaín (Málaga, España). Acta Bot. Malacit. 2015, 40, 107–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pesaresi, S.; Bioindi, E.; Vagge, I.; Galdenzi, D.; Casavecchia, S. The Pinus halepensis Miller Forests in the central-eastern European Mediterranean basin. Plant Biosyst. 2017, 151, 512–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohary, M. Geobotany; Sifriyat Poalim Ltd.: Maanit, Israel, 1955; 590p. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Zohary, M. The maquis of Quercus calliprinos in Israel and Jordan. Bull. Res. Counc. Isr. 1960, 9, 51–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ezra-Barnea. The Israel Oak Registry, International Oak Society Blog 2018. Available online: https://www.internationaloaksociety.org/content/israel-oak-registry#_ftnref1 (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Molero, M.J.; Pérez-Raya, F. Estudio fitosociológico de los sabinares de Juniperus phoenicea L. en el sector Malacitano-Almijarense (provincia corológica Bética). Lazaroa 1987, 7, 301–306. [Google Scholar]

- Bonari, G.; Fernández-González, F.; Çoban, S.; Monteiro-Henriques, T.; Bergmeier, E.; Didukh, Y.P.; Xystrakis, F.; Angiolini, C.; Chytrý, K.; Acosta, A.T.; et al. Classification of the Mediterranean lowland to submontane pine forest vegetation. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2021, 24, e12544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, L. Las Transformaciones Históricas del Paisaje: La Permanencia y la Extinción Local del Pino Piñonero. Los Montes y su Historia. Una Perspectiva Política, Económica y Social; Universidad de Huelva: Huelva, Spain, 1999; pp. 151–186. [Google Scholar]

- Braun-Blanquet, J.; de Bolòs, O. Aperçu des Groupements Végétaux des Montagnes tarragonaises. Collect. Bot 1950, 2, 303–342. [Google Scholar]

- Molinier, R. Études phytosociologiques et écologiques en Provence occidentale. An. Mus. Hist. Nat. Marseille 1934, 27, 1–273. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Martínez, S. La vegetacion de la clase Quercetea ilicis en Espana y Portugal. An. Inst. Bot. Cavanilles 1975, 31, 205–259. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Martínez, S. Sobre la nueva clase Polygono-Poetea annuae. Phytocoenologia 1975, 2, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiouvaras, C.N. Ecology and management of Kermes Oak (Quercus coccifera L.) Shrublands in Greece: A review. J. Range Manag. 1987, 40, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohary, M.; Orshan, G. The maquis of ceratonia siliqua in Israel. Vegetatio 1959, 8, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ighbareyeh, J.M.H.; Carmona, E.C. A phytosociological of plant communities and Biodiversity in the East-South of Idna Village-Hebron of Palestine. Int. J. Geosci. 2018, 9, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).