1. Introduction

China’s traditional fair trade has a history of several thousand years. The “Rites of Zhou” tells the story that three thousand years ago, the “city” had formed an organized state. This was later recorded in the “Book of Changes” and the “Historical Records”. In these historical materials, it is essentially explained that the origin of “fairs” in China is centered around wells. This kind of traditional fair, “by the gathering well” and centered around “trade and retreat” is mostly open air in open-field fairs. The traditional fair exists not only in historical records but also in traditional Chinese poems, such as “Xidu Fu” and “Mulan Ci”.

The traditional fair in this study is a kind of traditional place of trading, which is a form of activity and an urban public space for regular gathering and trading (

Figure 1).

Urban space is the material carrier of urban social and economic development, and traditional fair spaces in urban spaces include most types of community life space and other types of closely related urban public space, especially spontaneously generated fixed and mobile fairs. Additionally, the types of space and their vitality in cities tend to have impacts on the traffic safety and health aspects of the environment; however, many urban developers or managers of fair spaces as a type of urban public space tend to focus on the negative effects. Although fairs bring vitality to cities, this has not led to increased awareness of their value. We hope that on the basis of analyzing the logic of the vitality they bring, we can guide and solve their problems and retain and optimize their vitality.

We focus on three questions:

What is the point of the existence of a traditional fair?

How should traditional fair culture, as a kind of immaterial traditional culture, be inherited?

Can traditional fair elements be added in the existing urban center?

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Historical Inheritance of the Traditional Fair Space

Scholars have different opinions on the origin of traditional fairs. It has been confirmed that the fair trade was the pioneer of commodity exchange in ancient China. From the initial “fairs” and “border cities” to “free fairs” [

1], which have disappeared in many cities, the form and scale of fairs have always been different. The development of China’s traditional fairs in different periods has its own characteristics and regional differences [

2]. As recorded in the local “Chronicles of Shandong”, the development of local traditional fairs arose in the middle of the Ming Dynasty [

3]. Ethnographic records from minority areas also describe the original appearance and development of traditional fairs [

4]. In Europe, one of the origins of traditional fairs was religion [

5]. Although produced later, they were also an important economic activity [

6]. From the aspect of heritage protection, some ancient bazaars also have a certain value for historical aesthetics, culture, and society [

7]. For instance, the fair DjemaaEl Fna in Marrakech has been considered a heritage site by large institutions such as UNESCO and has been around for 1000 years.

The traditional fair has thousands of years of history as a form of commodity circulation organization, with fair trading as its basic function [

8]. Fairs are a daily communication space [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12] and are a public space closest to the daily life of the city, bearing traditional living habits and historical memories [

13,

14]; this is the charm of the traditional fair. The longevity of traditional fairs is threatened due to their likelihood of disappearing in the near future [

15], but they still have a good chance of “repair and renewal” in the aspects of the continuation of spatial texture at the city block level, the weaving of street and lane space, and the creation of public space [

16]. As a result, in recent years, both in China and elsewhere, an increasing number of urban developers have set their sights on the revival of traditional fairs [

17]. Among them, Zhou Dan et al. selected the relevant factors for establishing a regression model and predicted the scale of different types of traditional fair spaces [

18]. From the perspective of public space, traditional fair renewal is not only an urban design problem but also a sociological problem [

19].

2.2. Humanistic and Social Attributes of Traditional Fair Space

The scope of traditional fairs at the macro level of the city indicates that their development or relocation can affect or change street patterns, movement, and building patterns or types, land use, and can even eventually affect the development and formation of urban spaces [

20]. From the perspective of traditional fair spaces, they should not be confined to the geographic concept of traditional fair spaces but should be considered within the construction of social space [

21]. Traditional fair spaces, as a kind of economic phenomenon and a complex social phenomenon, have the continuity of the time and expanding space [

22], and the diverse activities can show the flexibility of space [

23]. This kind of space not only is the most important living space for human beings but also represents the earliest existence of a cultural place. It is a kind of human nature place [

24]. In this traditional fair environment, there exists a social relationship between the trade society and the economic model [

25,

26,

27,

28]. In South Korea and Indonesia, traditional buyers and sellers in fairs, established by social relations, have been described; it is concluded that the traditional fair not only includes a buying–selling relationship but in many cases also includes a concept of life and social cultural interaction. Castells argues that societies are hechas of stories and that these permeate experiences and relationships [

29,

30]. The work is based on an analysis of the traditional fair, and on the basis of the collected data, the service quality of customer rights and the interests of drivers were studied [

31]. According to the relationship between customer satisfaction and customer lifetime value in China, street food vendors can enrich residents’ dining options and make urban streets more vibrant, although the legalization of this model still requires a process [

32].

In addition to paying attention to the history of the traditional fair, the space, and the social relations between the buyers and sellers, some scholars have noticed that the fair serves as a public space that needs to be improved and paid attention to. Indeed, early on, [

33] proposed that as public places, fairs should consider both the organizational health aspect and the public place health aspect. Traditional fairs are one of the public places where people gather and trade, making them prone to the spread of disease [

34]. Therefore, as a public place in people’s life, environmental health problems in traditional fairs should not be underestimated [

35].

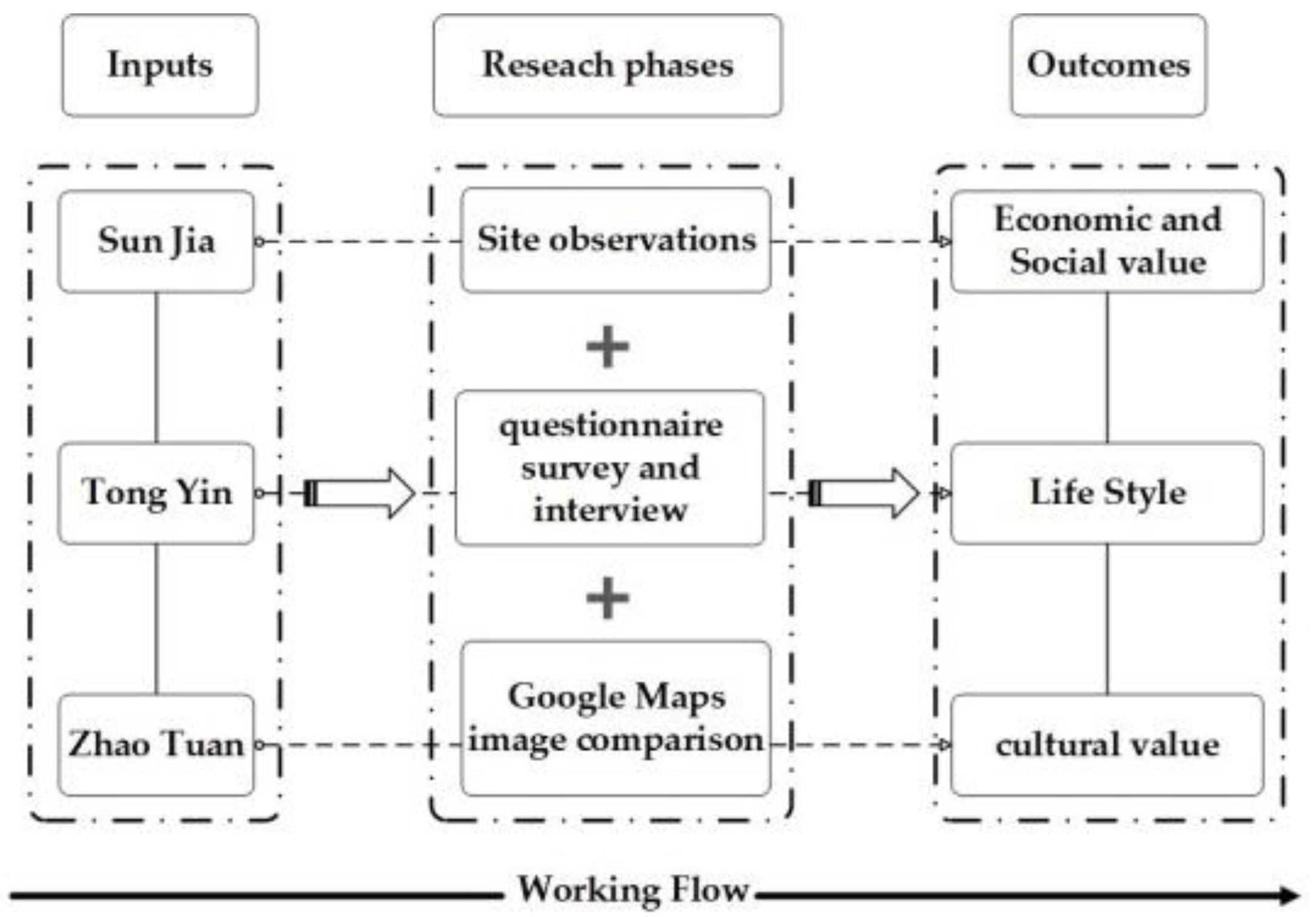

3. Materials and Methods

In order to facilitate observation, data collection, analysis and research, three typical fairs (Sun Jia, Tong Yin and Zhao Tuan) are selected as the study area. Collected through questionnaire and field investigation, the evolution of the three fairs from 2011 to the end of 2018 and their change processes were presented in graphical form through Google Maps image comparison. The details are as follows in

Figure 2.

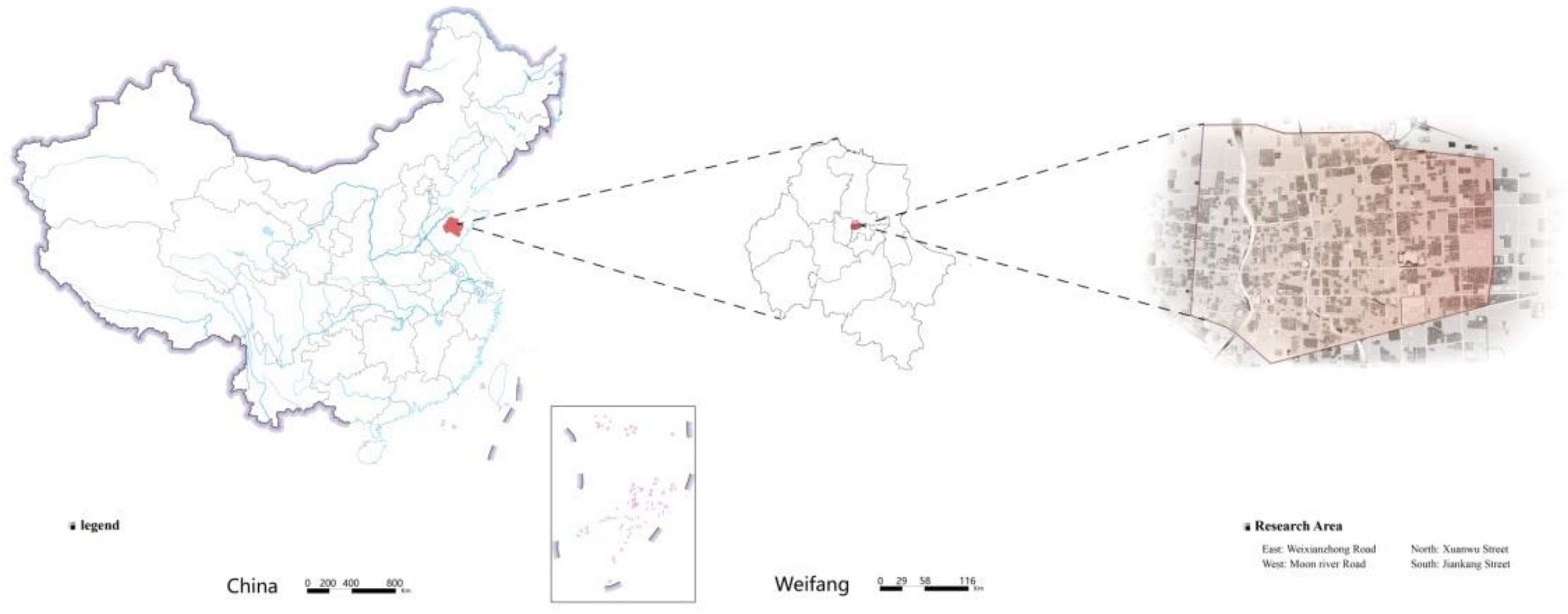

3.1. Study Location

The fair activities in Weifang are selected as the sample for this study based on available documents and information. Historical recorded show that there been continuous fair activities for 450 years, starting from the late Ming Dynasty. Volume 7 of the Weifang County Annals states that fairs reflect needs of human life and depend on trade; it also notes that the size of fairs increased with growing population. In 1672, in the early Qing Dynasty, the Weifang County Annals vividly recorded a fair once again. The traditional fairs continued in the following hundreds of years with steady development(

Figure 3).

Among the 31 fairs in Weifang, Sun Jia, Tong Yin, and Zhao Tuan are selected for our research for the following reasons: First of all, they are all located in the city center and are typical traditional fairs. Zhao Tuan is the oldest fair ever recorded in the Weifang County Annals, while Tong Yin fair is the earliest fair in the city that disappeared. Sun Jia fair is one of the popular fairs. The accelerating urbanization process of Weifang city has reduced the incremental space of the city in recent years, which has had profound impact on the development in fair activities. The three fairs are representative of traditional fairs reflecting related activities in Weifang city during the process of development and urbanization. Accordingly, related data on the fairs are collected and examined to explore the development characteristics and examine problems encountered in the development of the city’s traditional fairs.

3.2. Case Study

The case study methodology is helpful foranalyzing the universality and typicality of fair development among many fairs [

36,

37].A selection of 3 typical traditional fairs were selected from 31 fairs held in the city center of Weifang with the accelerating urbanization and reducing incremental space:

- (1)

Sun Jia: Located near Yuhe Road and Yuqing East Street, the fair opens regularly on lunar calendar days numbered 3 and 8. During the three years from 2015 to 2017, the fair location changed twice, quietly reappeared in 2019, and disappeared completely in 2021.

- (2)

Tong Yin: It opens regularly on lunar calendar days numbered 1 and 6. The fair has been through twists and turns in terms of its size and existence with an unclear future ahead.

- (3)

Zhao Tuan: Located between Fushou East Street and Beigong East Street, it opens regularly on lunar calendar days numbered 5 and 10.

3.3. Method

This section explains the three main methods we adopted, namely, site observation, survey, and image comparison.

3.3.1. Site Observations

For the past 8 years, we have tracked the development of traditional fairs in the urban centers, assessing old traditional fair environments and the current situation of the development of social activities. We have analyzed the changes in traditional fairs and determined rules regarding the changes.

3.3.2. The Questionnaire Survey and Interview

Questionnaire:

Extensive field research was conducted between January and May in 2018. Respondents were randomly selected from the three fairs with 139 valid questionnaires collected out of 160 questionnaires distributed. The questionnaire was designed according to the actual situation of the fair, aiming to have a more appropriate qualitative analysis of the fair. At the same time, the questionnaire also collected interviewees’ information, including their age and gender and the approximate distance between their current residence and the fair. Through the cross-sectional analysis of these collected data, some useful relationships were established.

Information on the purpose and motivation forcoming to the fair was also collected. The participants were asked to recall the key words they could relate to the fair and their expectations of the fair environment. The information on the words and their frequency statistics can used to analyze the participants’ understanding of the traditional fair in Weifang city.

Open-ended interviews:

To better understand the need and opinions of the sellers and buyers and managers of the fairs, we also conducted open-ended interviews. While the questionnaire was distributed, random interviews were conducted among the fair stall owners and fair shoppers to better understand the vitality and limitations of traditional fairs.

To honor ethics-related considerations, all the questionnaires and open-ended interviews fully respect the privacy of the interviewees.

3.3.3. Google Maps Image Comparison

Google Earth satellite images of the main urban area of Weifang city from 2011 to 2018 were used for comparative analysis. We extracted clear and effective continuous images for our research. The change and evolution of the fair were further investigated through a literature review and field investigation.

The relevant data regarding the fairs in this study were collected from the official website of the government and from the researchers’ field investigations.

4. Results

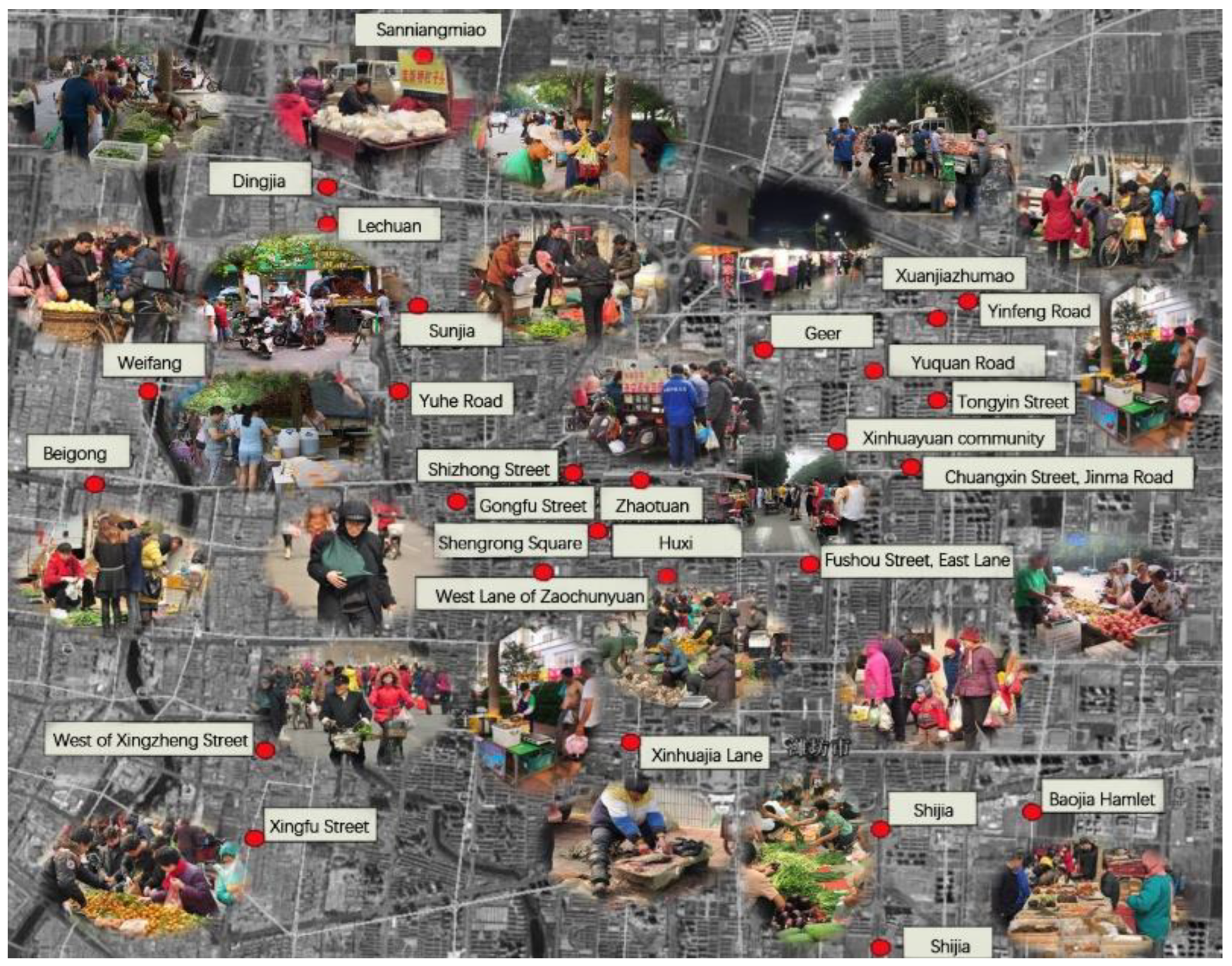

4.1. Existing Conditions and Characteristics of the Traditional Fairs

The existing fairs are mainly distributed in urban centers and are concentrated near residential areas (

Figure 4). From 2011 to 2018, most of the fairs remained in place. However, with the urbanization process and the reduction in space for urban public activities, the venues of the fairs have been squeezed, and, in the case of the fair atSun Jia, it was moved three times in two years.

Based on the investigation of the current situation of Weifang fair and the study of 139 effective questionnaires, it was found that the traditional fairs present the following characteristics in terms of their model and aggregation form.

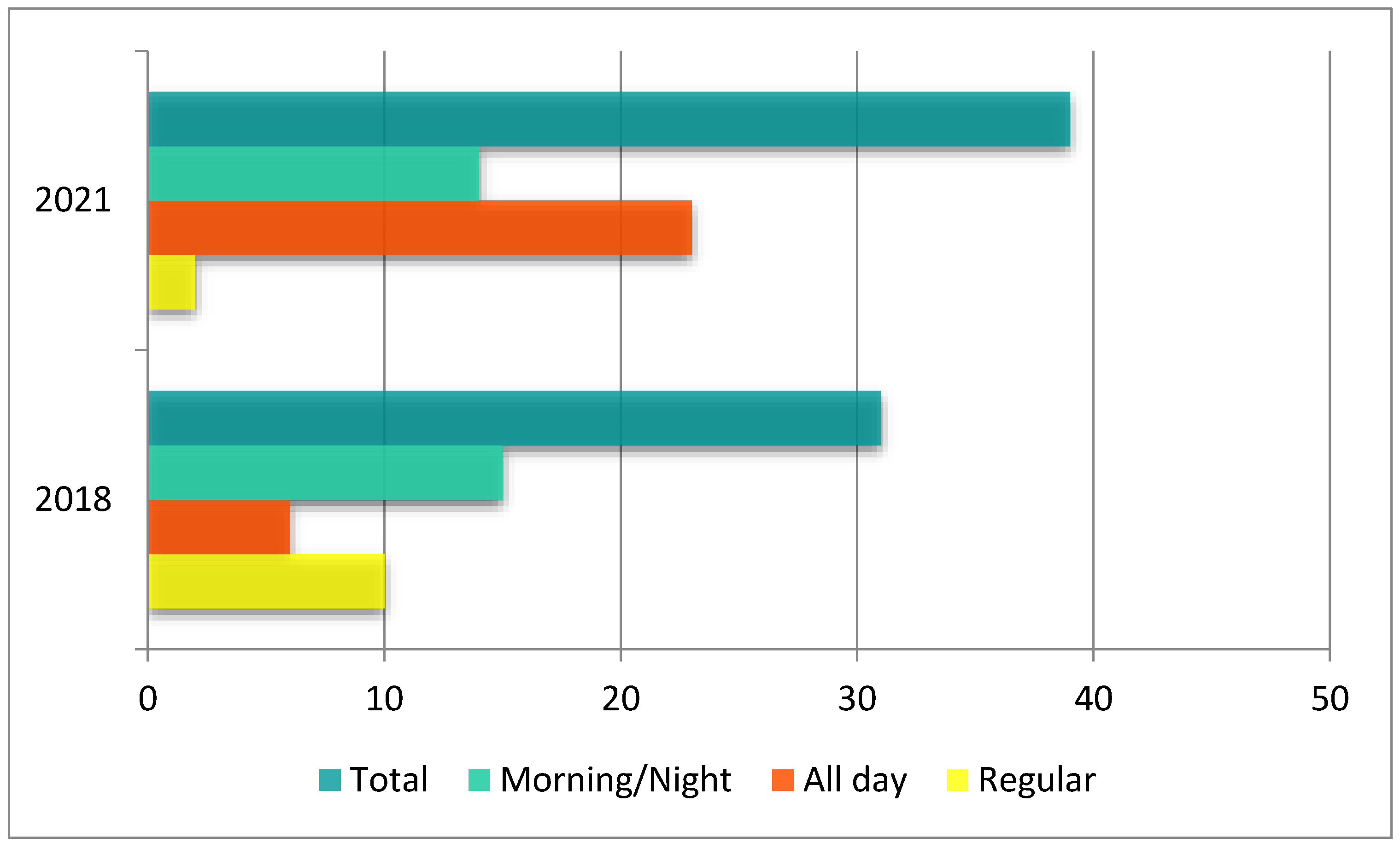

4.1.1. The Traditional Fair Gathering Time Has Two Forms

The regular and daily gathering times: By the end of 2018, among the 31 fairs in the main urban area that we surveyed, the fairs that gathered regularly accounted for 32%, and the daily fairs accounted for 68% (

Table 1). Most of the daily fairs were located near residential areas in built-up environments in the city center.

4.1.2. The Traditional Fairsin Urban Center Mode Diversification

Through the investigation and research, at present, in the central urban area of Weifang city, the modes of operation of the fair are mainly composed of three types: open-square fairs, open-street fairs, and mixed fairs.

4.1.3. Fairs Carry the Inheritance of Regional Culture and Traditional Lifestyles

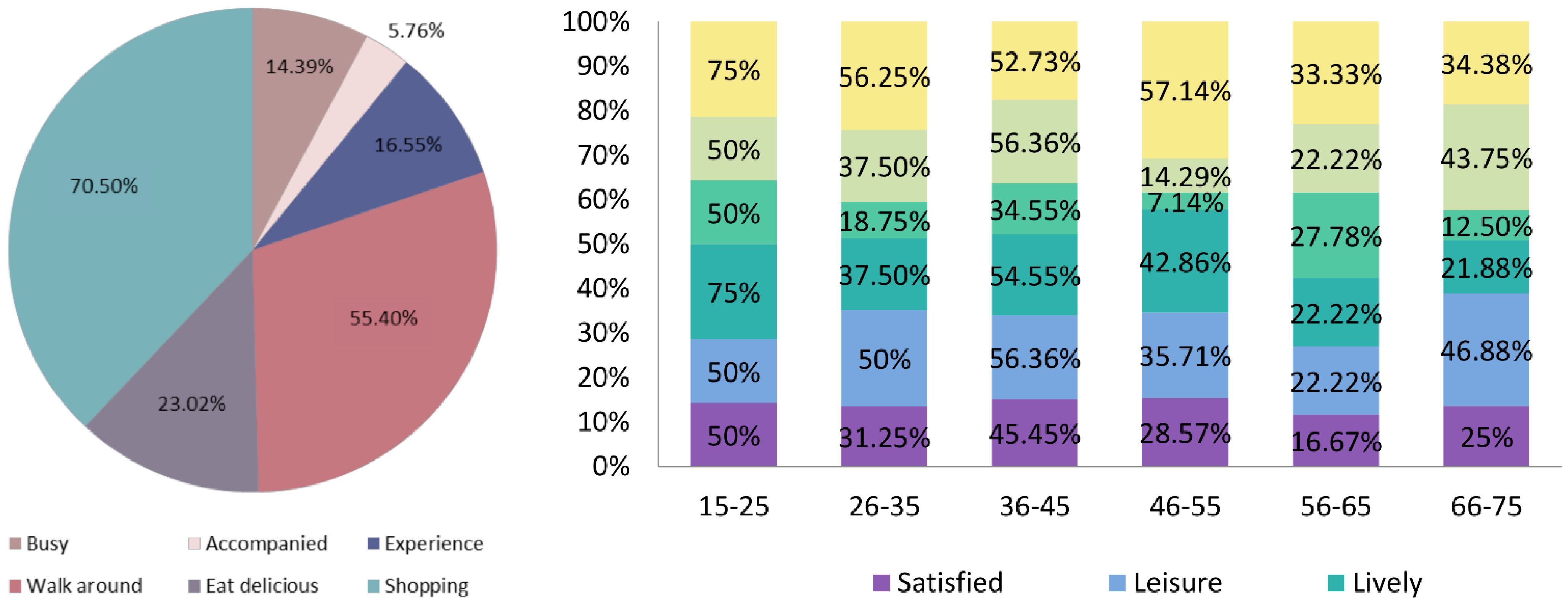

According to the questionnaire survey, in addition to the traditional shopping and eating behaviors, traditional fairs are also motivated by entertainment and life experience. The act of going to the fair was found to evoke childhood memories, arousing nostalgic feelings and generating strong emotional resonance. People of all ages described most of the trade fairs in positive terms such as ”Leisure”, ”Happy”, “Lively”, “Satisfied,” and other positive words that were used to describe most of the fairs, indicating that the shoppers’ behavior in the fairs shows deep participation and experience (

Figure 5).

4.2. Descriptive Analysis

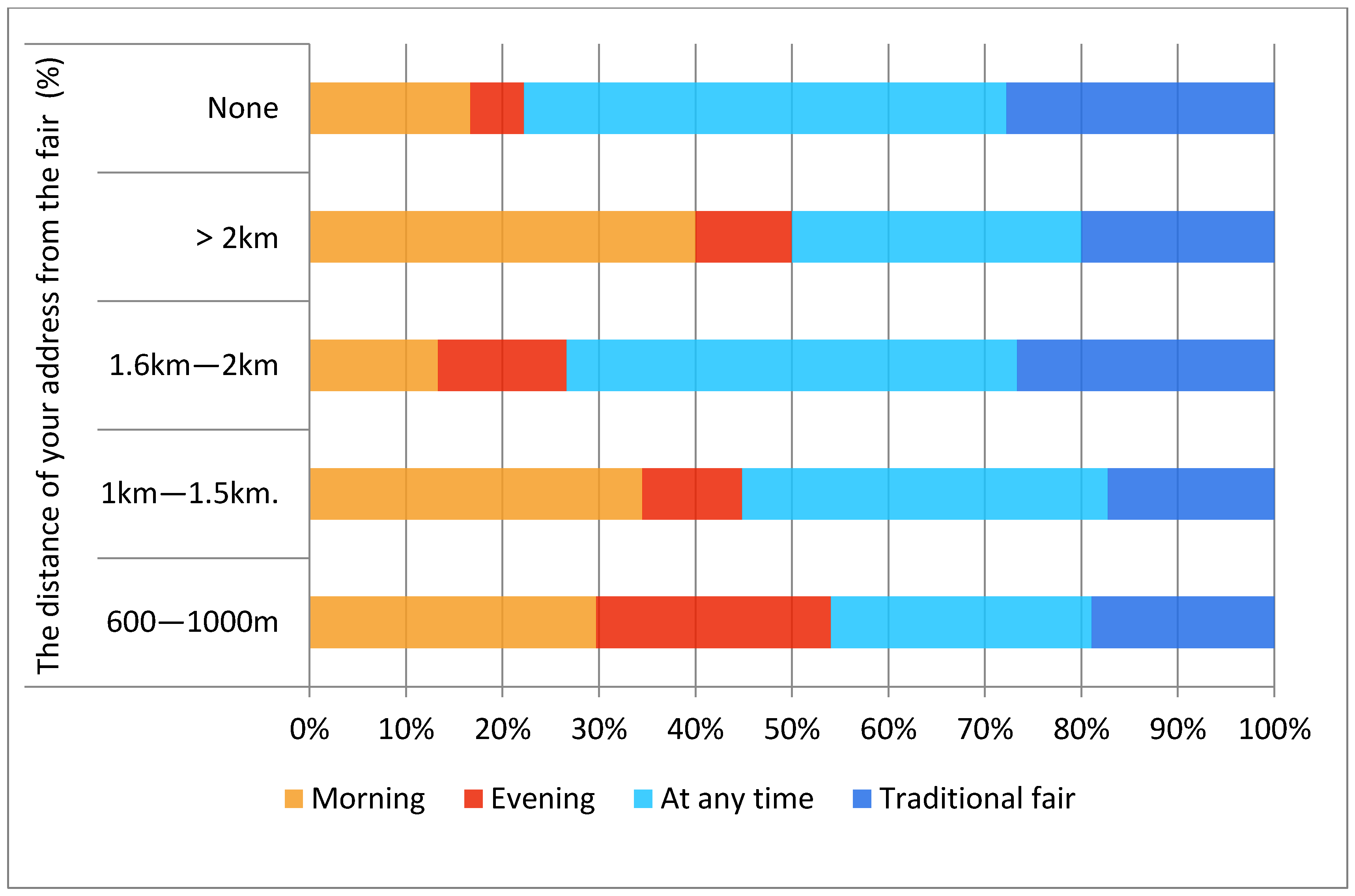

As can be seen from

Figure 6, there wasno significant difference between the choice of going to the morning fairs or the night fairs and the distance between residents’ addresses and the fair (

p > 0.05); that is, the time respondents choose to go to the fair wasnot affected by the distance from home to the fair.

When asked which one they would prefer to go to if they could choose supermarket or fair (both are in the same location and are not newly opened places), gender, age, and distance from the fair did not affect respondents’ answers (

Table 2): the samples didnot show significant differences in terms of age or the distance between their addresses and fairs (

p > 0.05). However, there were significant differences by gender (chi = 6.123,

p = 0.013 < 0.05). According to the percentage comparison, the proportion of men choosing the fair was 50.51%, which was significantly higher than that of the supermarket (27.50%), while the proportion of women choosing the supermarket was 72.50%, which was significantly higher than that of the fair (49.49%). It can be seen from the above data that age, gender, and distance from the fair had no great influence on the selection results. The fair has become the main means of purchasing goods in people’s life.

4.3. Comparative Study and Analysis

4.3.1. Three Fairs and Three Fates

A Disappeared Fair: Sun Jia

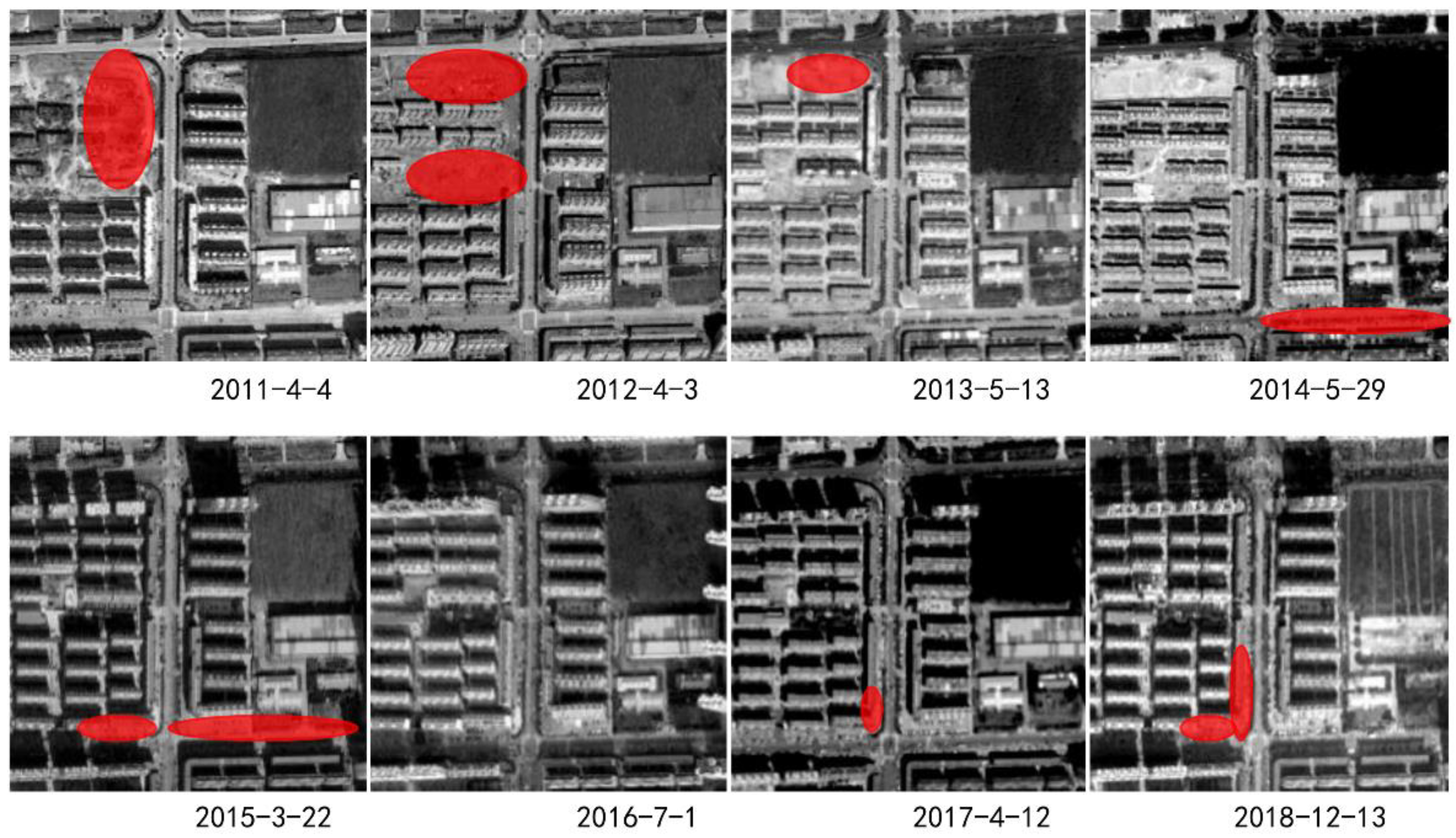

The Google Earth satellite images in

Figure 7 show the evolution of the Sun Jia gathering from 2011 to 2017. In 2011 and 2012, the fair was located on a vacant lot and tended to expand into the road. However, in 2013, due to the new residential area where the original traditional fair was located, the fair was forced to move to the newly repaired Yu Qing Street. This situation was not maintained for a long time. Due to the establishment of a hygienic and civilized city and the re-examination of the hygienic and civilized city, the Sun Jia fair was forced to move out of Yu Qing Street and moved to a vacant street corner vacant in 2015. However, in the three-year period of 2015, 2016, and 2017, the fair location changed twice, and its scope became increasingly smaller. In the face of the shrinking traditional fairs, the people who we interviewed discussed a sense of helplessness.

“I just had a look around the fair. Many vendors I used to be familiar with didn’t know where to set up their stalls.”

- Mrs. Liu, speaking at Sun Jia fairs that moved twice in three years.

“After all, residents near the Sun Jia traditional fairs can come to shop whenever they need, which is very convenient.”

- Mr. Zhang.

However, from the perspective of a businessperson, there was an urgent appeal.

“If we move again, I don’t know where else to go, I feel very uncomfortable, maybe later I have to go to the street stalls.”

- Mr. Zhou, the owner of a Sun Jia fair stall.

“I hope the relevant departments can consider setting up a special area for Sun Jia fairs so that we don’t have to move around so frequently and we can provide better services to street vendors and residents.”

- Mr. Han, the street vendor who set up his stall at the Sun Jia fair.

It can be seen that for both buyers and sellers, the existence of the fair undoubtedly provides a very convenient economic life for the people, and at the same time, in the transaction, a relatively harmonious social relationship between people has been built.

Unfortunately, however, in the second half of 2018, despite everyone’s love and yearning for the Sun Jia fair, it eventually retired from the stage and disappeared from the public view.

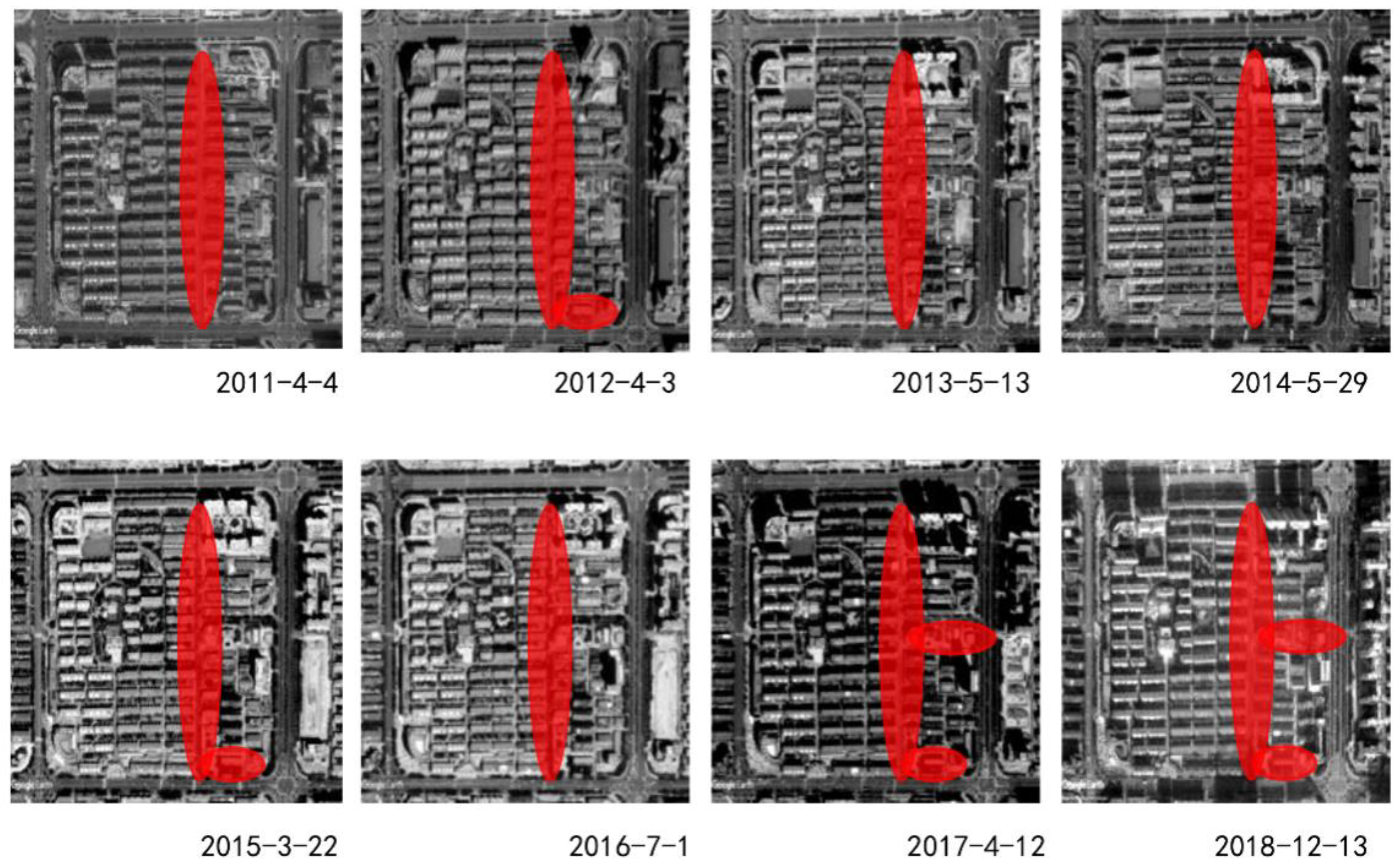

A Surviving Fair: Tong Yin

From prosperity to extinction, and then to the resumption of the fair, it has experienced many twists and turns, making the existing situation worrying. What are shown in

Figure 8 are the changes in the Tong Yin fair between 2011 and 2018. As can be seen from the figure, during the short period of nearly eight years, the Tong Yin street group was relocated five times, namely, in 2012, 2013, 2014, 2016, and 2017. Among these, from 2011 to 2012, the traditional fair was forced to be divided into two sections due to the change inland functions. In 2013, for the same reason, the developers on the land continued to develop, and the increase in the real estate prices forced the fair to continue to shrink. By 2014, due to the new buildings and communities in the original place, the fair was relocated to the roadside. In the following two years, the fair developed well. At this time, Tong Yin Street started from Wei Xian Road in the east and Yin Feng Road in the west, showing a great expansion trend. In 2016, however, due to the re-examination of the “National Civilized City”, the fair was banned. In the following year, the traditional fairs in Tong Yin disappeared from the sight of the people.

“Where did the traditional fairs go? Why haven’t you heard? We used to buy things here; quite unexpected, quite lost.”

- Mr. Sun.

“Although there is a superfair near by, in this traditional fairs, I have bought more than ten years worth of food; suddenly I do not know where to go to buy food.”

- Mr. Li said when Tong Yin fairs was banned.

At the end of 2017, people were delighted to see that there were people gathering together spontaneously in Tong Yin Street and the northwest corner of Yin Feng Road. Regardless of whether the fair experienced several changes or gathering together, it was once again proved that the traditional fair was what the people needed and had become an indispensable part of their lives.

A Thriving Fair: Zhao Tuan

The Zhao Tuan fair was recorded as early as the Ming Dynasty, as in “Zhao Tuan fairs, a mile northeast of the county”. In the later years of the Qing Dynasty, in the 11th year of Emperor Kangxi and the 25th year of Emperor Qianlong, the Wei Fang County Annals and other county annals records recorded the Zhao Tuan fair in anunchanged position in this location; thus, it has existed there for a long time. Currently, the traditional fair is preserved.

In contrast to the previous two traditional fairs, Zhao Tuan continued to exist in the eight-year period of 2011–2018 and is steadily expanding in scale (

Figure 9). In addition, there are records of the fair in the Wan Li years of the Ming Dynasty (from about 1563), which gives the fair a history of more than 450 years.

4.3.2. The Geography Location of the Fair Changes

From the above cases of traditional fairs, we can clearly see that from 2011 to 2018, due to urban construction, supervision, city creation, and other factors, the Sun Jia fair was repeatedly relocated: from 2015 to 2017, there was the situation of three years and two relocations. The Tong Yin fairhas been relocated five times, moving from prosperity to decline and from prevalence to disappearance. The reasons can be roughly summarized as the following three points:

- (1)

Creating a national civilized city. Weifang was awarded the title of civilized city in 2015. Since then, it has been reevaluated as a civilized city every September. The cycle of politics year after year is not only an acceptance of the city’s work effect but also a consideration of the spiritual life of a city. From the perspective of the initial phase of creating a healthy and civilized city, the aim is to make the city where people live more livable. However, this form of creating a city is too stylized, and the means are too mechanized. The “one-size-fits-all” model also cuts out the “sense of place” of urban public spaces that should be preserved.

- (2)

Rapid urbanization development and expansion of urban space construction. With the development of urbanization, the rapid development of urban rail transit has promoted the further expansion of urban space. Compared with 2010, China’s inner urban area increased by 219,000 square kilometers, an increase of 12.26%; the built-up area increased by 202,000 square kilometers, an increase of 50.37%; and the urban construction land increased by 163,000 square kilometers (data missing in 2019), an increase of 40.95%. On the one hand, cities keep expanding, but on the other hand, the urban siphon effect promotes the urban population to gather to the center, and the rapid population influx leads to shortages in the supply of the original urban functions, and the available land is increasingly strained. Due to construction communities, the increase in real estate prices, changes to the nature of the land, the acceleration of urbanization processes, and the decrease in available urban public land, traditional fairs have been forced to relocate or close.

- (3)

The above two fairs Sun Jia and Tong Yin have experienced ups and downs: One disappeared, and one reappeared after a revival. The Zhao Tuan fair can be seen from the county records to thus far be enduring. The built environment has a great influence on fairs. For example, the Sun Jia and Tong Yin fairs, mentioned above, were moved around in unbuilt environments. External land and traffic conditions have a great influence on the location and scale of fairs. Zhao Tuan, Xin Hua Lane Xin, and other fairs with good development trends are basically in public spaces in urban centers. They are either on the side of the road or in small fixed sites, and in either case, they are built in more stable environments.

4.3.3. The Revitalization of the Fair

Zhao Tuan’s example shows that a good urban space conducive to the occurrence and development of traditional fairs is necessary. Similarly, a good fair development or renewal can greatly enhance the vitality of urban space [

38,

39]. This is the inherent advantage of traditional exhibition space.

Based on the above analysis, this study suggests that traditional fair spaces should be considered important urban public spaces for development and renewal in urban public space design. The main reasons are as follows.

The fair is mostly concentrated in Kuiwen, a high-tech district with two urban areas: the residential areas are more densely built up. The high-tech district is a newly built urban area. In the early stage of development, there were few supporting businesses, and the distribution of vegetable fairs and super fairs was uneven. As a result, the traditional fairs became the most important places in which people could buy daily goods.

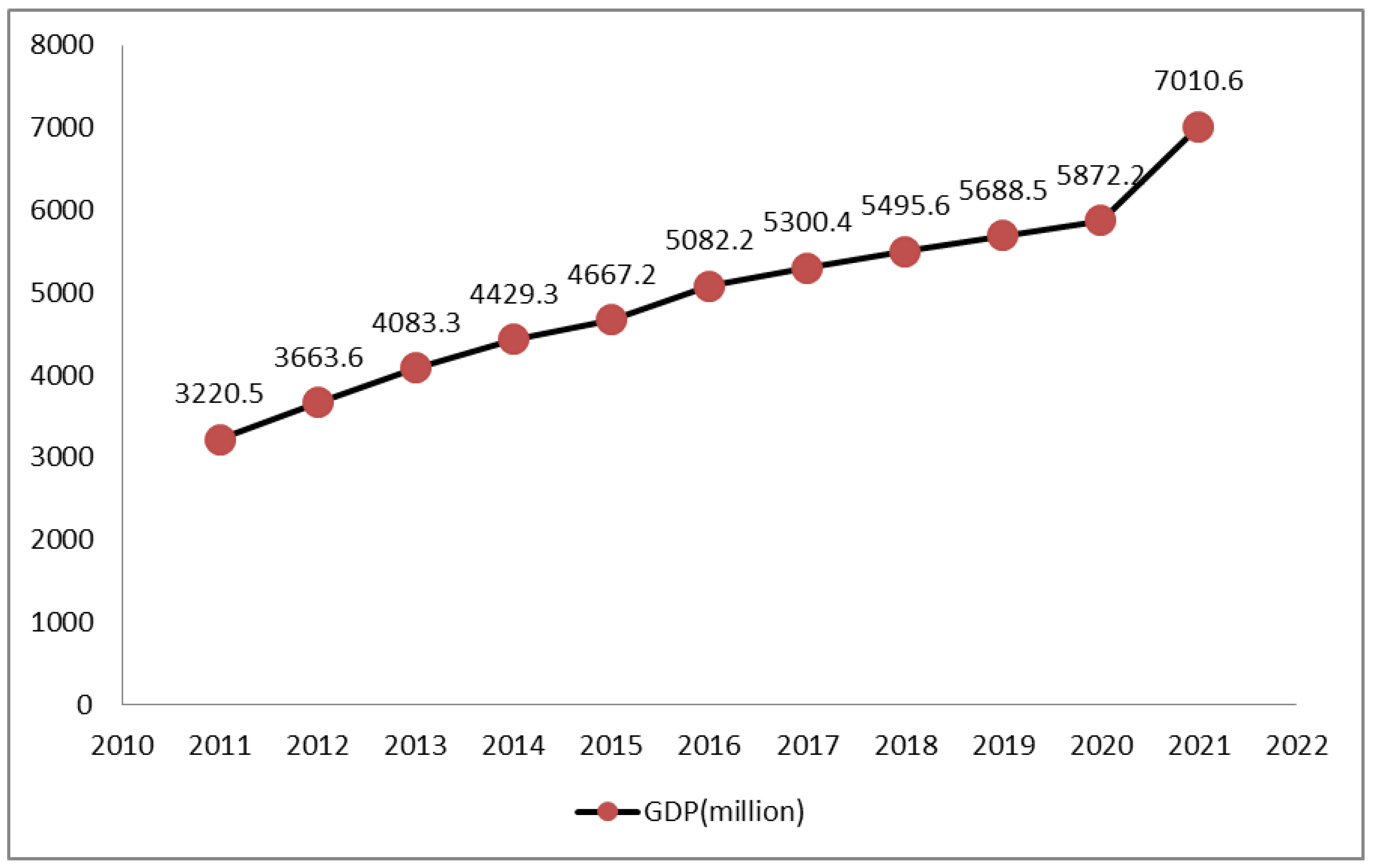

Based on the concept of a 15 min life circle, Weifang has been vigorously carrying out economic recovery and creating reemployment opportunities since 2019. It has increased support for free fairs and free trade in the urban area to provide opportunities for reemployment. Seventeen fixed fairs and four morning/night fairs have been added in the main urban area. This is also because the Weifang government supports and tolerates free economic forms such as the fair that steadily increases Weifang’s GDP year by year (

Figure 10).

Traditional fairs are a part of urban life, and they should be the most dynamic part of urban life. In current societies, reinforced concrete residential boxes for people’s living spaces and the mobile electronic informatization lifestyle affect interpersonal communication, but in fair spaces, we usually see another picture. Here, “firewood and necessities, sauce, vinegar, and tea” do not need to be bought; people sell and bargain, and neighbors can walk together while shopping. Only in this traditional scene of a fair space can one better experience the vitality of the urban living space.

Fairs carry regional culture and traditional ways of life. They are an inheritance of immaterial culture and a return of urban life. The survival of fair spaces in the city center also requires careful consideration by designers in the design process. Such designs must rely on how the traditional fair activates the urban space [

40,

41], such as more interpenetration with the surrounding space and the introduction of more urban functions.

5. Discussion

In the process of urban development, it cannot be denied that the development of traditional fairs is closely related to the growth of economic activity. This study found that between 2011 and 2021, due to urban construction, supervision, the creation of a national civilized city, and other factors, the new urban areas in Wei Fang city squeezed the survival space of urbanfairs. There were 39 fairs in 2011. In 10 years, 9 traditional fairs have disappeared and 26 have been added. The fairs disappeared so quickly it seemed as though a traditional fair disappeared every year (

Figure 11). These results show that urban land use change and decreases in urban public land have had no substantial impact on people’s demands. In the central urban area, most traditional fairs are still preserved, and these are usually in crowded areas, indicating that people’s demands are the reason for the emergenceof these traditional fairs.

The study of traditional fairs in Wei Fang shows that the environment and locations of traditional fairs have become an important part of the surrounding communities and a seasoning of life. Traditional fairs have both attractiveness and competitiveness. What happens between buyers and sellers includes not only trading activities but also social activities. In addition, in the post-epidemic era, people’s demand for public communication spaces has been greatly strengthened. The development of traditional fairs can both satisfy the requirements for people’s economic activities and provide urban public spaces in which people can communicate with one another.

As can be clearly seen from the above, in Wei Fang, the traditional fairs, the excellent cases of the fairs Zhao Tuan in the city center are still being reconstructed or updated. In China, the culture, history, and lifestyle of traditional fairs have existed over a much longer period, but their development and renewal have been slower and more difficult. From the perspective of the continuation of the historical context, before the disappearance of traditional fair culture and the destruction of spaces for fairs in urban centers, studies on the revival of the value and significance of fair culture in urban centers are still urgent.

6. Conclusions

As mentioned above, in this study, we analyzed satellite images of Wei Fang from 2011 to 2018. Comparing the images, we looked at nearly eight years of Wei Fang city center’s traditional fairs distribution, the existing performance characteristics, and the statistical analysis of the fairs’ distribution.

The limitation of this paper is that the study area is only in the city where the researcher lives, but it is also because of this that the author has a deeper feeling about the changes brought by traditional fairs to people’s life. In addition, most of the relevant data and the updated map data of the fair research in this study covered a period up to the end of 2018. When we finished this writing paper, the data were still changing, and the number of traditional fairs was still decreasing. In the latest data from 2021, Zhao Tuan is one of the only few traditional regular fairs in the urban center (the other is Weifang’s fair). Compared with the data from2018, nine traditional regular fairs have disappeared in a short period of less than four years, and only seven remain in the eight areas of the city (

Figure 12). This is inevitable in the process of urban development and change, which highlights the original purpose of this research: to protect the traditional culture and traditional ways of life that are disappearing.

From the data of the survival of traditional fairs in Wei Fang city over a period of several years, we are pleased to see that in recent years, society has become more open to fairs, and the city has become more tolerant of fair content. After the demolition of fairs, reconstruction is not necessarily a good thing; in the urban center of the city, change or renewal is needed for traditional fairs to survive in this environment. Fairs in the city not only provide trade opportunities for the people but also become suitable public spaces and places of communication in the urban center. However, in the process of urbanization, traditional fair spaces become compressed, and the sense of place is diminished; thus, fairs should find new ways to survive. In the center of the city, urban environments have been completed, and the built-up area of urban design should focus on stock space design, especially for existing building patterns that have been formed. Gradual, small-scale renewal design should be carried out to optimize the built environment, to promote the integration of urban public spaces, to assist in the development of traditional fairs, and to establish places in which people can communicate.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and J.Y.; methodology, J.L.; validation, J.Y.;formal analysis, J.L.; investigation, J.L. and Q.M.; resources J.L. and J.Y.; data curation, J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.; writing—review and editing, J.L., Q.M. and T.M.; visualization, J.L. and Q.C.; supervision, J.Y.; project administration, J.Y.; funding acquisition, J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Foundation of China, grant number 17BXW062.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available for use upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors offer thanks to the reviewers and all the editors in the process of revision.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhong, X. A Brief History of China’s Fairs Trade Development; Chengdu University of Science and Technology Press: Chengdu, China, 1996; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y. The Historical Development and Geographical Distribution of China’s Fairs. Geogr. Res. 1999, 3, 318–326. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, W. Analysis of Reasons of Shandong Fairs Trade in Qing Dynasty. East China Econ. Manag. 2007, 21, 84–86. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y. Research on the Change of Traditional Fairs—A Study on Yang Dong Fairs in the Minority Areas of Southwest Hubei Province; Hubei Institute for Nationalities: Shi’en, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M. The Changes of the Fair between the 11th Century and the 18th Century England; Tianjin Normal University: Tianjin, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, M. The origin and evolution of the ancient European fair. J. Lit. Hist. 2008, 7, 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y. Urban Conservation in United Kingdom: An Case Study of the Covent Garden Market, London; Hangzhou Normal University: Hangzhou, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H. Rural Fairs development and small town spatial layout strategies. Urban Plan. 2010, 34, 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; Ding, Q. The Development of Urban Fairs Space, the Unity of Traditional Functions and Modern Requirements. Art Des. 2015, 12, 67–69. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, M. Research on the Planning and Layout of Fairs in Medium-Sized Cities; Shandong University: Jinan, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L. Study on the Renewal and Reconstruction of Spatial Environment of Retail Fairs of Farmers in Mingcheng District of Xi’an; Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology: Xi’an, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, X.; Liu, J.; Zhao, X. The practice of creating the environment and upgrading the format of the new food fairs in Chao Neinan Street. Urban Archit. 2018, 9, 55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J. Research on strategy of improving fairs in the inner-city of Shanghai. Shanghai Urban Plan. 2016, 6, 111–115. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Y. The choice of new urbanization path from city to city—Based on the analysis of the contradiction between habitus and field. J. Chang. Stud. 2017, 1, 138–145. [Google Scholar]

- Putra, R.D.D.; Rudito, B. Planning Community Development Program of Limbangan Traditional market Revitalization with Social Mapping. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 169, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y. Exploration of fairs renovation strategy and method under urban renewal—Taking three fairs renovation in Barcelona as examples. Archit. Cult. 2015, 12, 59–60. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. A bite of London in borough market. Advert. Overv. 2013, 3, 106–109. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, D.; Song, F.; Bao, Q.; Song, W. The Study of the Connotation and the Method of Land Use Size Forecast of Fairs in Towns and Villages. Urban Dev. Res. 2016, 23, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. Strategy Research on Urban Public Space Integration Based on Fairs Renewal; Tsinghua University: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Karnajaya, S. The Influence of Market Relocation on Urban Morphology. Master’s Thesis, Diponegoro University, Semarang, Indonesia, 2002. (In Indonesian). [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J. From geographic space to social space: The transformation of research paradigm of rural fairs. J. Zhengzhou Inst. Light Ind. 2016, 17, 112–120. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y. An Anthropological Analysis of the Traditional Fairs Places and ItsArchitectures in Yunnan; Tongji University: Shanghai, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Aliyah, I.; Setioko, B.; Pradoto, W. Spatial flexibility in cultural mapping of traditional market area in Surakarta: A case study of Pasar Gede in Surakarta. City Cult. Soc. 2017, 10, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. Cultural Identification and Main Body of Life:A Survey on the Form of fair Settlement from the perspective of Economic Anthropology. Planner 2005, 21, 91–95. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, A. Peasant Marketing in Java; Free Press of Glencoe: New York, NY, USA, 1962; Volume 80. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.I.; Lee, C.M.; Ahn, K.H. Dongdaemun, a traditional market place wearing a modern suit: The importance of the social fabric in physical redevelopments. Habitat Int. 2004, 28, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekomadyo, A.S. Tracing Genius Loci of Traditional Markets as Urban Social Space in Indonesia. 2007. Available online: http://www.ar.itb.ac.id/pa/wpcontent/upload/2007/11/201212 (accessed on 2 February 2014).

- Rahadi, R.A. Factors related to repeat consumption behavior: A case study in traditional market in Bandung and surrounding region. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 36, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- La Era de la Información: Economía, Sociedad y Cultura: I: La Sociedad Red; Alianza: Madrid, Spain, 2005.

- La Era de la Información: Economia, Sociedad y Cultura: II: El Poder de la Identidad; Alianza: Madrid, Spain, 2003.

- Wang, H.; Kim, K.H.; Ko, E.; Liu, H. Relationship between service quality and customer equity in traditional markets. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3827–3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, N.; Zhong, T.; Scott, S. From Overt Opposition to Covert Cooperation: Governance of Street Food Vending in Nanjing, China; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 30, pp. 499–518. [Google Scholar]

- Persyaratan Kesehatan Lingkungan Tempat-Tempat Umum; Direktorat Jenderal Pemberantasan Penyakit Menular dan Penyehatan Lingkungan Pemukiman (PPM dan PLP), Departemen Kesehatan: Jakarta, Indonesia, 1993. Available online: https://opac.perpusnas.go.id/DetailOpac.aspx?id=290922 (accessed on 5 April 2020).

- Sakinah, K. Gambaran Sanitasi Pasar Tradisional Tanah Merah: Desa Petrah, Kecamatan Tanah Merah, Kabupaten Bangkalan. Skripsi Thesis, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, East Java, Indonesia, 2006. Available online: https://repository.unair.ac.id/24041/ (accessed on 29 December 2011).

- Nainggolan, R.; Supraptini, D. Sanitasi Pasar Tradisional di Kabupaten Sragen Jawa Tengah dan Kabupaten Gianyar Bal. J. Ekol. Kesehat. 2016, 11, 112–122. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods; Sage Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, J.; Yang, M.; Liu, G.; Li, Y.; Luo, D.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Song, Q. Urban Sub-Center Design Framework Based on the Walkability Evaluation Method: Taking Coomera Town Sub-Center as an Example. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Pang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Lu, C.; Tang, X.; Cheng, W. Mapping Urban Spatial Structure Based on POI (Point of Interest) Data: A Case Study of the Central City of Lanzhou, China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, H.; Dong, J.; Choi, M.; Jeong, J. The Effect of Cultural City on Regional Activation through the Consumer Reactions of Urban Service. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szilágyi, K.; Lahmar, C.; Rosa, C.A.P.; Szabó, K. Living Heritage in the Urban Landscape. Case Study of the Budapest World Heritage Site Andrássy Avenue. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).