Abstract

The purpose of this article is to explore the influence of new agricultural business entities on farmers’ employment decision and provide reference for improving policies related to new agricultural business entities and farmers’ employment. This paper constructs a theoretical analysis framework of “new agricultural business entities—land transfer and purchase of agricultural socialized services—farmers’ employment decision”, and then empirically tests the impact of new agricultural business entities on farmers’ employment decision by combining the analysis methods of the benchmark regression, propensity score matching and mediation effects. The research shows that: (1) New agricultural business entities are beneficial for promoting farmers’ employment decision. (2) Renting out land and the purchase of agricultural socialized services have a positive and partially mediating effect between the new agricultural business entities and farmers’ employment decision, and the mediating effects of the two paths account for 7.12% and 6.25% of the total effects, respectively. (3) In addition to key variables, personal characteristics of decision-making, family characteristics and production and management characteristics are also key factors that affect farmers’ employment decision. (4) The new agricultural business entities increase the probability of farmers’ employment (with legal contract) and entrepreneurship, and reduce the idle labor force in rural areas. Finally, this study proposes some policy recommendations including establishing a perfect farmland transfer market, developing rural industry properly and improving agricultural socialized service systems.

1. Introduction

At present, the core of the “three rural” problem is the problem of farmers, and the core of this is the income problem. Since farmers’ income is mainly derived from farmers’ labor income, farmers’ employment decision have become the key to the study of rural issues. In 2018, the No.1 Central Document proposes “strengthening support and guidance services, and promoting rural employment and entrepreneurship”. The issue of farmers’ employment has become a major concern for the Chinese government. The two-tier management system based on the household contract management has left the “sequelae” of small-scale cultivated land and highly dispersed plots [1,2], which gradually creates some problems such as low specialization degree of agricultural production, low efficiency and the difficult to achieve the optimal allocation of agricultural labor resources. Aiming at the practical challenges faced by farmers, the state has proposed a series of related policies and measures to cultivate and develop new agricultural business entities, and promote agricultural moderate scale management. As the “leader” of China’s agricultural modernization construction, whether the new agricultural business entities can alleviate the “contradictions between the people and land in rural areas” and promote the farmers’ employment is the key issue discussed in this paper.

The so-called new agricultural business entities refer to agricultural economic organizations formed by rented land in recent years, which are directly engaged in the production and management activities of the primary industry, mainly including family farms, agricultural cooperatives and agricultural enterprises, etc. Compared with small farmers, the new agricultural business entities have larger area of cultivated land, better material and equipment conditions, and a higher technological level and management ability [3], and they are engaged in specialized and large-scale agricultural production and operation organizations with the goal of maximizing profits. According to data released by the agricultural sector, by 2018, there were more than 3 million new agricultural business entities including nearly 600,000 family farms, 2.173 million legally registered farmer cooperatives and 370,000 social service organizations engaged in agricultural production trusteeship [4]. With the continuous development of new agricultural business entities, these have become the important force in the supply of agricultural products in China, and also become the leading force in promoting the development of agricultural modernization.

At present, the academic research on new agricultural business entities mainly focuses on the following four aspects. First, the existing literature mainly focuses on the performance of new agricultural business entities and analyzes the efficiency differences in efficiency between the different new agricultural business entities [5,6,7,8].

The second focus of current research is studying the constraints on the development of new agricultural business entities, such as financing constraints [9], insufficient endogenous development support policies and weak fiscal coordination in supporting agriculture [10]. Thirdly, when the external effects of the new agricultural business entities are considered, current research mainly focuses on the driving effect of the new agricultural business entities on farmers’ employment. For example, from the perspective of qualitative and case studies, some scholars affirmed that the emergence of new agricultural business entities not only absorb many experienced people to return home for employment [11], but also provide jobs for rural residents and solve a part of the surplus labor problem in countryside [12,13]. The fourth focus is the impact of new agricultural business entities on farmers’ performance. The new agricultural business entities reduce farmers’ agricultural production costs and promote farmers’ efficiency and income [14,15] by providing high-quality and low-cost production services [16] and establishing an interest-linking model with small farmers [17].

The academic circles affirmed the ability of the new agricultural business entities to promote farmers’ employment, but they still have great potential to expand: firstly, the existing research results focus on the impact of new agricultural business entities on farmers’ employment, and pay less attention to the mechanism of new agricultural business entities on farmers’ employment decision. Second, the existing studies mainly focus on qualitative analysis and case analysis, and few explored the impact of new agricultural business entities on farmers’ employment decision from the quantitative perspective. Third, the research area was relatively small and it was difficult to reflect the basic situation of the whole county. The purpose of this paper is to quantitatively analyze the influence and internal mechanism of new agricultural business entities on farmers’ employment decision on a national level, which provides a theoretical basis and data support for government departments to improve farmers’ employment policies.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Hypotheses

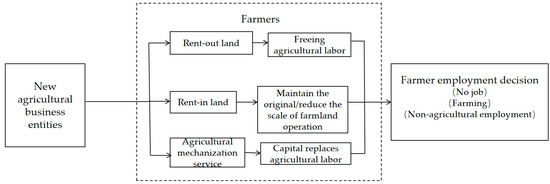

New agricultural business entities in the countryside not only require local cultivated land and labor, but also bring capital and technology to the countryside, which directly and indirectly affect farmers’ employment through multiple channels. The possible mechanisms are as follows:

2.1. The Impact of New Agricultural Business Entities on Farmers’ Employment Decision

As the main force of agricultural production and management, the development of new agricultural business entities is not only beneficial to the new agricultural business entities themselves, but is also conducive to the development of farmers, agriculture and rural areas [11]. First, at the present stage, most of the new agricultural business entities are dominated by employees [18]. With the new agricultural business entities expanding the scale of agricultural land management, the labor structure of the new agricultural business entities has also changed; from the management mode dominated by family agricultural labor force to the agricultural management mode dominated by long-term employees or a small number of employees [19]. Therefore, small farmers reduce idle labor and improve the allocation of family labor by working for new agricultural business entities. Second, through the integration of three industries, the new agricultural business entities integrate agricultural production, processing, sales and leisure services, which means that the primary, secondary and tertiary industries are closely linked and also coordinates their development [20]. For example, the processing and packaging of agricultural products, tourism and leisure agriculture, and other related services provide more employment opportunities for small farmers, so that farmers can expand from a single agricultural sector to secondary and tertiary industries. The increase in local labor demand is conducive to improving local labor wages [21], thereby changing the allocation of farmers’ labor force, and affecting farmers’ employment decision. Therefore, it is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 1.

The new agricultural business entities are conducive to improve the allocation of farmers’ labor force, and then affect farmers’ employment decision.

2.2. The Influence of New Agricultural Business Entities on Farmers’ Employment Decision through Land Transfer

First, new agricultural business entities need a large amount of cultivated land for large-scale operations, which indirectly promotes the development of local land transfer market and facilitates the smooth renting out of land. Renting out land reduces the demand for agricultural labor force to a certain extent, and farmers re-allocate labor according to their own comparative advantages and transfer the released labor to the non-agricultural sector [22,23], which can obtain considerable non-agricultural income and satisfactory land rents. Second, since China’s rural society is based on acquaintance networks, most of the land transferred by farmers comes from relatives, friends or acquaintances in the village, and land rents are generally low or even rent-free. The new agricultural business entities have a large demand for cultivated land after entering the countryside, which increases the local land market competition and leads to the rise in land rents [24]. With constant transaction costs, farmers need to pay higher land rents for rented land. Due to the increase in investment costs and the low farming income of small-scale planting, farmers reduce their willingness to rent land and increase their willingness to rent out land, thereby affecting their employment decision. Therefore, it is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 2.

The new agricultural business entities affect the farmers’ employment decision by promoting farmers to rent out land and inhibiting farmers to rent land.

2.3. The Impact of New Agricultural Business Entities on Farmers’ Employment Decision by Purchase of Agricultural Socialized Services

With the development of non-agricultural industries and labor market, the cost of employment keeps rising. In order to reduce production costs, new agricultural business entities purchase agricultural machinery to relieve part of the labor demand when expanding the scale of farmland operation [25]. Due to the loss caused by special funds constrains and annual depreciation [26], the rational new agricultural business entities will provide appropriate technical services to surrounding farmers to reduce asset specificity and agricultural production costs, thereby promoting the development of the local agricultural socialized services market [27]. Farmers choose appropriate agricultural technologies and rent advanced equipment to meet their own needs by imitating the new agricultural business entities. On the one hand, this can alleviate the impact of the weakening of agricultural labor force on agricultural production, so that the weak labor force can also be competent for the current agricultural production and reduce the idle labor force in rural areas; on the other hand, it can reduce the labor intensity of agricultural production [28], release more agricultural labor force, and then change the farmers’ employment decision. Therefore, it is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 3.

The new agricultural business entities influence the farmers’ employment decision by purchase of agricultural socialized services.

Land transfer and purchase of agricultural socialized services mediates the relationship between the new agricultural business entities and the farmers’ employment decision, i.e., “new agricultural business entities—land transfer and purchase of agricultural socialized services—farmers’ employment decision” (as shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A theoretical framework of the influence of new agricultural business entities on farmers’ employment decision.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sources of Date

This paper uses data from the China Household Finance Survey (CHFS) carried out nationwide from 2015, by the Survey and Research Center for China Household Finance of Southwestern University of Finance and Economics. The CHFS samples covered 29 provinces (municipalities and autonomous regions), and they were divided into three research regions: eastern, central and western. The eastern region includes Beijing, Fujian, Guangdong, Hainan, Hebei, Jiangsu, Liaoning, Shandong, Shanghai, Tianjin and Zhejiang. The central region includes Anhui, Henan, Heilongjiang, Hubei, Hunan, Jilin, Jiangxi and Shanxi. The western region includes Gansu, Guangxi, Guizhou, Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, Qinghai, Shaanxi, Sichuan, Yunnan and Chongqing. There are 1396 village committees in 351 counties with a total sample size of 37,289 households. These data have a wide coverage and a large sample size, which has good representativeness and ensures the accuracy of research conclusions to a certain extent. The questionnaire contains the basic information of family members, agricultural production and management and other information to provide the basis for this study. For research needs, the household head ID is used as the identification code to connect the household data with the household head data, and the data were cleaned up. Finally, 8690 valid questionnaires were obtained.

3.2. Variables

The core independent variable was chosen based on the existing studies [4]. This study opted to use “whether the new agricultural business entities exist in the village” to represent the core independent variable. Combining the question “To which of the following operating types does your family business belong?” in the CHFS questionnaire, if the answer is leading specialized households, family farms, agricultural cooperatives, or agricultural enterprises, it indicates that the new agricultural business entities exist in the village, then the value is 1. Otherwise, it is 0 (as see in Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of variables.

Dependent variable: The explained variable in this paper is farmers’ employment decision. This paper divides the types of work into no job, farming, and non-agricultural employment (including employment, self-employment or entrepreneurship and others). It can be seen from Table 2 that the farmers’ employment with new agricultural business entities in the village is significantly higher than that of farmers without new agricultural business entities in the village, and it is significant at the 1% statistical level.

Table 2.

Difference between groups of variables.

Mediator variable: The mediator variables in this article include land transfer (including rent-out land, rent-in land) and purchase of agricultural socialized services. It can be seen from Table 2 that renting land, renting out land and purchase of agricultural socialized services of farmers with new agricultural business entities in the village are significantly higher than those without new agricultural business entities in the village, and they are significantly positive at the 1%, 5% and 10%, statistics levels, respectively.

The control variable was based on the farmers’ employment decision and related literature research [29], the control variables include personal characteristics of decision-making, family characteristics, and agricultural production and management characteristics. Among them, personal characteristics of household head include age, education and political status; family characteristics include average age of family labor, average education level of family labor force, heath status of family members and so on; agricultural production and management characteristics include cultivated land scale, farming income and land expropriation.

3.3. Methods

3.3.1. Benchmark Regression Model

In order to quantitatively estimate the effects of the new agricultural business entities on farmers’ employment decision, the econometric model could be specified as follows:

where Yi represents the farmers’ employment decision of the i-th farmer; Xi is the core independent variable; Ni represents the control variable; α, β, λ are the parameters to be estimated, and ε is the random disturbance term.

3.3.2. Mediating Effect

Following the mediation effect model developed by Baron and Kenny (1986) [30], we use the following three models to test the mediating effect of land transfer and purchase of agricultural socialized services on the relationship between new agricultural business entities and farmers’ employment decision:

where Yi represents the farmers’ employment decision of the i-th farmer; Ei represents the core independent variable; Xi represents control variables; a2 is the overall effect of the new agricultural business entities on the farmers’ employment decision; b2 is the influence of new agricultural business entities on the mediator variables; Mi is the intermediate conduction mechanism (including land transfer and purchase of agricultural socialized services); c2 and c3 are the direct effects of new agricultural business entities and mediator variables on the farmers’ employment decision of the i-th farmer, respectively; and represents the residual. Bringing Equation (3) into Equation (4), the mediator effect b2c3 of the new agricultural business entities can be obtained. The new agricultural business entities have an indirect impact on the farmers’ employment decision through the mediating variables of transfer land and purchase of agricultural socialized services.

3.3.3. The Propensity Score Matching

It can’t solve the possible problems of the samples to use the above-mentioned traditional linear regression method to test the influence of new agricultural business entities on farmers’ employment decision. Meanwhile, compared with the instrumental variable method and the Heckman two-stage model, the assumption conditions of the propensity matching score method are easier to be satisfied. So in this paper, propensity score matching (PSM) was used to match the treatment group (with new agricultural business entities) and the control group (without new agricultural business entities). Controlling the consistency of external conditions, this paper discusses the impact of new agricultural business entities on the farmers’ employment decision. The research steps are as follows:

Step 1: Calculating the propensity score value. The personal characteristics of decision-making, family characteristics, and agricultural production and management characteristics of the sample objects are selected as covariates, and Logit model is used to calculate whether the sample object has the tendency score of new agricultural business entities.

where Di = 1 and Di = 0 indicates that the new agricultural business entities exist and do not exist in the village, respectively, and Xi represents observable farmers’ characteristics.

Step 2: Performing propensity score matching. In order to ensure the robustness of the matching results, this paper selects the following three mainstream matching methods: K nearest neighbor caliper matching, nearest neighbor matching and local linear regression matching.

Step 3: Calculating the average processing effect. According to the counterfactual analysis framework, the average treatment effect (ATT) of the treatment group is calculated to reflect the impact of new agricultural business entities on the farmers’ employment decision, and its expression is:

where Y1i represents the farmers’ employment decision with new agricultural business entities in the village; Y0i represents the farmers’ employment decision without new agricultural businesses in the village. can be observed, while cannot be observed, and it is necessary to use propensity score matching to construct an alternative index of .

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Benchmark Regression

The Stata 13.0 software is used to estimate the constructed benchmark regression model, and the impact of new agricultural business entities on farmers’ employment decision are obtained (Table 3). The regression results of Table 3 show that the new agricultural business entities have a significant positive impact on farmers’ employment decision, and hypothesis 1 is established.

Table 3.

The influence of new agricultural business entities on the farmers’ employment decision.

In terms of the personal characteristics of decision-making, education of the household head has a significant positive impact on farmers’ employment decision, which is consistent with Dhanaraj and Mahambare (2019) [31]. The main reason is that farmers with a higher education level not only have rich knowledge reserves, but also have good learning ability, so that they have comparative advantages in participating in employment. Age of household head has a significant negative impact on farmers’ employment decision, because young workers are more likely to have employment opportunities [32]. Political status has a significant negative impact on farmers’ employment decision. This can be attributed to the fact that Communist Party members are more vulnerable to new things and new ideas than others, and their acceptance abilities are stronger, which is more conducive to obtaining employment-related information [4,33]. Financial knowledge training has a significant positive impact on farmers’ employment decision. This correlation occurs primarily because economic training enables farmers to master more financial knowledge and skills, thereby increasing the probability of farmers obtaining employment opportunities.

In terms of the family characteristics, the health status of family members has a negative significant impact on farmers’ employment decision, indicating that the larger the proportion of family members with poor health, the smaller the probability of farmers’ employment. The reason for this is that the more people need to be cared for, the longer the farmers spend caring for their family members, which inhibits the participation of labor in employment. The average age of family labor force has a negative significant impact on farmers’ employment decision. The main reason is that the older the family labor force, the lower the labor ability, and the fewer employment opportunities will be obtained. The average education level of the family labor force has a significant positive impact on farmers’ employment decision. This indicates that the higher the education level of the family labor force, the higher the quality of the labor force, the stronger the ability to collect employment information, the more able the family is to adapt to different employment environments, and then the stronger the willingness and behavior to participate in employment.

In terms of the characteristics of production and management, agricultural labor force has a significant negative impact on farmers’ employment decision. This may be because when the agricultural labor force is greater, farmers are heavily dependent on arable land, thus restricting the transfer of the agricultural labor force to non-agricultural sectors. The cultivated land scale has a significant negative impact on farmers’ employment decision. The result of this is that the cultivated land scale is greater and farmers can carry out large-scale mechanized production, thus reducing the production costs and increasing the agricultural income, and then reducing farmers’ non-agricultural labor participation. Farming income has a negative significant impact on farmers’ employment decision. The reason is that the higher the farming income, the stronger the dependence of farmers on agriculture, the more time, energy and manpower are spent in the process of agricultural production, so the probability of non-agricultural employment is smaller.

4.2. Mediating Effect

According to the above model, this article first examines whether the new agricultural business entities affect the farmers’ employment decision through land transfer and purchase of agricultural socialized services (as shown in Table 4). The regression (2) and regression (4) in Table 4 shown that the new agricultural business entities promote renting out land and inhibit renting land. The reasons are as follows: due to the existence of social networks and circles of acquaintances, most of the cultivated land of farmers came from relatives and friends in the past, and the land rent was low or even rent-free [34]. However, the new agricultural business entities in the countryside strengthen the land market competition and improve land rent, which has increased the cost for farmers to rent land. In addition, small-scale planting of farmers leads to lower agricultural comparative income, lower willingness to rent land and higher willingness to rent out land. In regression (3) and regression (5), after adding intermediary variables (rent-out land and rent-in land), renting out land is still significant, but renting land is not significant. The regression (6) shows that the new agricultural business entities promote farmers to purchase agricultural socialized services. The main reason is that the technology spillover of the new agricultural business entities promotes the development of local agricultural socialized services and enables farmers to obtain convenient agricultural socialized services. Therefore, farmers can replace agricultural labor by purchasing agricultural socialized services, thus releasing more agricultural labor to the non-agricultural employment sector. After adding intermediary variables in regression (7), the new agricultural business entities and purchase of agricultural socialized services variables are significant. At the same time, because the parameter estimates of , and are significant, it indicates that the mediating effect of the rent-out land and purchase of agricultural socialized services exists, but it is a partial mediating effect. The mediation effect accounted for 7.12% and 6.25% of the total effect, respectively. This shows that about 7.12% of the impact of new agricultural business entities on farmers’ employment decision is achieved through renting out land, and 6.25% is achieved through the purchase of agricultural socialized serviced. Thus, hypothesis 2 and hypothesis 3 are established.

Table 4.

The intermediary role of land transfer and purchase of agricultural socialized services in the influence of new agricultural business entities on the farmers’ employment decision.

To test the robustness of the mediating effect, a bootstrap test is used to re-estimate the mediating effect. As can be seen in Table 5, in the two paths of rent-in land and purchase of agricultural socialized services, the 95% confidence intervals of the Percentile and Bias-Corrected for direct and indirect effects do not include 0, so the mediation effect exists. Regression (5) shows that after adding the rent-in land, the variable of new agricultural business entities is still significant, but the rent-in land is no longer significant, so it is impossible to judge the existence of the mediating effect. However, the bootstrap test in Table 5 shows that the 95% confidence intervals of Percentile and Bias-Corrected for the direct and indirect effects contain 0, in the path of rent-in land, so it is considered that rent-in land does not have an intermediary effect on the impact of new agricultural business entities on farmers’ employment decision.

Table 5.

Robust estimation of mediating effect.

4.3. Robustness Test

4.3.1. The Test of Propensity Score Matching

In the process of model construction in this paper, we may face endogenous problems. The core independent variable, the new agricultural business entities, has the problem of “self-selection”. Generally speaking, the self-development of new agricultural business entities has a spillover effect, which plays a significant role in optimizing the allocation of rural household labor and improving the development of the local land market, and then affects the farmers’ employment decision. Conversely, regions with more non-agricultural labor participating will release more cultivated land resources to attract high-quality new agricultural business entities to invest in rural areas. Therefore, the propensity score matching (PSM) model is used to test robustness. Pual et al. (1983) [35] believed that the results of propensity matching scores are reliable and convincing, and require that there is no significant difference between the treatment group and the control group before and after matching, and the absolute value of the standard error of all covariates after matching is less than 20. It can be seen from Table 6 that the absolute value of the standard deviation of each variable after the matching is less than 10, and there is no significant difference in the 11 variables after the matching, so the matching effect is good.

Table 6.

Results of Balance test.

In this paper, K nearest-neighbor caliper matching, nearest-neighbor matching and local linear regression matching are used to measure the average treatment effect of new agricultural business entities on the farmers’ employment decision (as shown in Table 7). The ATT values calculated by the above three methods are 0.036, 0.042, 0.036 and 0.046, respectively, and are all significant at the statistical level of 5%. It can be seen that the ATT values obtained based on different matching methods are different, but still have strong consistency, indicating that the new agricultural business entities promote the employment of farmers, which further indicates that the above benchmark regression results have good robustness.

Table 7.

The treatment effect of propensity score matching.

4.3.2. Replace the Core Explanatory Variable Test

In order to make the results more convincing, this paper replaces the core independent variable, “whether the new agricultural business entities exist in the village”, with “the number of new agricultural business entities in the village”. The regression (8) in Table 8 shows that after replacing the core independent variables, the number of new agricultural business entities in the village has a positive significant impact on farmers’ employment decision at 5% level, which is consistent with the previous results, indicating that the research results are more robust.

Table 8.

The treatment effect of propensity score matching.

4.3.3. Test of Replacing Dependent Variable Variables

Referring to studies by Potter (2006) [36], and Fu et al. (2016) [37], this paper reclassifies employment decision as working (including non-agricultural employment and farming) and no job. The regression (9) in Table 8 shows that after replacing the dependent variable, the new agricultural business entities still have a positive significant impact on the farmers’ employment decision, and the research hypothesis 1 is verified again.

4.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

The above result only shows that new agricultural business entities significantly affect farmers’ employment decision, but does not show what kind of work the farmers participate in. To answer this question, this paper divides the working state of laborers into seven types: non-working, farming, employment (with legal contract), employment (without legal contract), self-employment or entrepreneurship, freelance work and other working states, and then analyzes the influence of the new agricultural business entities on these seven working types. It can be seen from Table 9 that the new agricultural business entities significantly increase the probability of labor participating in farming, employment (with legal contract), and entrepreneurship, but have no significant impact on freelance work and other. As the same time, the new agricultural business entities significantly reduce the probability of farmers being employed (without legal contract) and having no job. This association is primarily due to two reasons: (1) the new agricultural business entities in the countryside drive the development of local related industries to provide stable employment channels for farmers. In addition, in the countryside, the new agricultural business entities promote the development of the local land transfer market, alleviate the obstacles of land to the transfer of farmers’ labor force and encourage farmers to allocate more time to the non-agricultural sector, thereby reducing farmers’ employment (without legal contract) and increasing their employment (with legal contract). Second, the new agricultural business entities promote the development of the local agricultural socialized service market, because they alleviate the demand for high-quality labor force in agricultural production, promte the weak labor force to continue to engage in agriculture, and reduce the idle labor force in rural areas.

Table 9.

The impact of new agricultural business entities on different working conditions.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Conclusions

Based on the data of China Household Finance Survey (CHFS) in 2015, this paper constructs a theoretical model of the impact of new agricultural business entities on the farmers’ employment decision and benchmark regression, mediating effect model and propensity score matching are used to analyze the impact and its mechanism of new agricultural business entities on the farmers’ employment decision. The following conclusions were reached: (1) New agricultural business entities have a significant positive impact on farmers’ employment decision. (2) The new agricultural business entities can promote farmers’ employment decision through rent-out land and purchase of agricultural socialized services. The mediating effects of the two paths account for 7.12% and 6.25% of the total effect, respectively. However, the effect of rent-in land on farmers’ employment decision is not significant, so it is unlikely to play a role through this path. (3) Education of household head, financial knowledge training and average education level of family labor force have significant positive effects on the farmers’ employment decision, while age of household head, political status, average age of family labor, health status of family members, agricultural labor force, cultivated land scale and farming income have negative effects on the farmers’ employment decision. (4) The new agricultural business entities significantly reduce the proportion of idle labor and increase the probability of employment (with legal contract) and entrepreneurship of farmers.

5.2. Suggestions

In summary, the following finding is obtained: First, the local governments should establish a land transfer guarantee insurance system to protect the interests of the new agricultural business entities and farmers. The new agricultural business entities and farmers share insurance premiums, and the county-level government grants a certain percentage of subsidies, so that no matter which party breaches the contract, the other party can receive insurance compensation. Second, the local government should develop rural industries to stabilize the employment channels of farmers. The government should cultivate the agricultural industry consortium to promote the integration of the three industries of the new agricultural business entities, extend the agricultural industry chain, improve the employment-driven capacity of the new agricultural business entities, create more employment opportunities, and provide guarantee for farmers’ employment. Third, the agricultural socialized service system should be established and improved. In the process of fostering new agricultural business entities, local governments guide the new agricultural business entities with service willingness and ability to play their comparative advantages to provide pre-production, in-production and post-production services for surrounding farmers, so as to alleviate labor constraints faced by farmers in agricultural production and promote the organic connection between small farmers and modern agriculture. Fourth, the government should strengthen the training of farmers’ skills, and improve the level of farmers’ human capital of farmers and the personal quality of transferred labor force, so as to realize the high quality transfer of rural labor force.

Our study can be extended in several directions: first, the key variables studied in this paper are only measured by “whether the new agricultural business entities exist in the village”. In the future, we should comprehensively, accurately and scientifically measure the quality of the development of new agricultural business entities, and study the impact of the development of the new agricultural business entities on farmers, rural areas and agriculture. Secondly, this paper uses cross-sectional data. In the future, long-term and more detailed data should be collected to reflect the dynamic process of new agricultural business entities, in order to carry out more in-depth empirical analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Z. and L.C.; methodology, W.Z., L.C. and Y.C.; writing—original draft preparation, L.C.; writing—review and editing, W.Z., L.C., K.D. and Y.C.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42071221).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The research data in this article can be obtained from survey and research Center for China household finance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Falco, S.D.; Penov, I.; Aleksiev, A.; Rensburg, T. Agrobiodiversity, farm profits and land fragmentation: Evidence from bulgaria. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartvigsen, M. Land reform and land fragmentation in central and Eastern Europe. Land Use Policy 2014, 36, 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Yan, W. Analysis on function orientation and development countermeasures of new agricultural business entities. J. Northeast Agric. Univ. 2016, 23, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Zou, W.; Duan, K. The influence of new agricultural business entities on the economic welfare of farmer’s families. Agriculture 2021, 11, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Li, Y. The Values and influence factors of family farms’ efficiency. Manag. World 2020, 36, 168–181, 219. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ji, X.; Liu, S.; Yan, J.; Li, Y. Does security of land operational rights matter for the improvement of agricultural production efficiency under the collective ownership in china? China World Econ. 2021, 29, 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostov, P.; Davidova, S.; Bailey, A. Comparative efficiency of family and corporate farms: Does family labour matter? J. Agric. Econ. 2019, 70, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gao, M.; Xi, Y.; Wu, B. Analysis on the operating performance and difference of new agricultural operation entities—based on the survey data from fixed observation points in rural areas. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. 2018, 5, 10–16, 160–161. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, C. Is new agricultural management entity capable of promoting the development of smallholder farmers: From the perspective of technical efficiency comparison. J. China Agric. Univ. 2020, 25, 200–214. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Wang, S.; Hu, J. Research on inherited barriers and supporting polices of family farms: Based on Micro data and case analysis of family farms in Shandong province. Issues Agric. Econ. 2021, 4, 121–131. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Ding, X. Influence of rural industrial convergence development perception on entrepreneurial learning of returning migrant workers: A compound multiple mediator effect model. J. Harbin Inst. Technol. 2021, 23, 154–160. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Z. The welfare effects from the development of the new agricultural management entities. J. Quant. Tech. Econ. 2016, 33, 41–58. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, R.; Gao, B.; Zhou, P.; Zheng, F. The Driving Capacity of New Agricultural Management Entities and Its Determinants: An Analysis Based on Data from 2615 New Agricultural Management Entities in China. Chin. Rural. Econ. 2017, 11, 17–32. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Blekking, J.; Gatti, N.; Waldman, K.; Evans, T.; Baylis, K. The benefits and limitations of agricultural input cooperatives in zambia. World Dev. 2021, 146, 105616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhofstadt, E.; Maertens, M. Can agricultural cooperatives reduce poverty? heterogeneous impact of cooperative membership on farmers’ welfare in rwanda. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2015, 37, 86–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, M.; Yan, X.; Guo, Y.; Ji, H. Impact of risk awareness and agriculture cooperatives’ service on farmers’ safe production behaviour: Evidences from Shaanxi Province. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 312, 127724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Kou, G.; Wang, S. Thoughts on constructing the benefit affiliating mechanism of new types of agribuiness and small household farmers. J. China Agric. Univ. Soc. Sci. 2019, 36, 89–97. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Chen, W.; Luo, B. How can capital into the countryside drive farmers’ operation: Based on the analysis of Jiangxi Lvneng model. Issues Agric. Econ. 2021, 01, 69–81. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Z. China new agricultural operators since the reform and opening up: Growth, evolution and trend. J. Renmin Univ. China 2018, 32, 43–55. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Ma, B.; Peng, C. Analysis on the factors of the industry convergence for new agricultural management subjects—Based on the survey data of RCRE. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2019, 09, 105–113. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. Research on the proverty-alleviation effect of the agricultural industrialization in Chinese underdeveloped areas-spatial econometric analysis based on the panel data of 15 provinces. J. Shanxi Univ. Financ. Econ. 2020, 42, 52–68. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Deininger, K.; Savastano, S.; Carletto, C. Land fragmentation, cropland abandonment, and land market operation in albania. World Dev. 2012, 40, 2108–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deininger, K.; Jin, S.; Nagarajan, H.K. Efficiency and equity impacts of rural land rental restrictions: Evidence from india. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2008, 52, 892–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheng, W.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, N.; He, Z.; Zhang, L. How did land titling affect china’s rural land rental market? size, composition and efficiency. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, K.; Liu, Y.; Yamauchi, F. Growing advantage of large farms in asia and its implications for global food security. Glob. Food Secur. 2016, 11, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Wang, X.; Lu, H. The dual role and its dynamic transformation of agricultural machinery service of the new agricultural business entities: A preliminary analysis framework. Issues Agric. Econ. 2021, 2, 38–53. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.; Lin, Q. The impact of the development of production outsourcing services on the allocation of rural labor—Based on the perspective of farm household heterogeneity and link heterogeneity. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2021, 6, 101–114. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mi, Q.; Li, X.; Gao, J. How to improve the welfare of smallholders through agricultural production outsourcing: Evidence from cotton farmers in Xinjiang, Northwest China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, L. Self-employment of Chinese rural labor force: Subsistence or opportunity?—An empirical study based on nationally representative. J. Asian Econ. 2021, 28, 101397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 51, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanaraj, S.; Mahambare, V. Family structure, education and women’s employment in rural India. World Dev. 2019, 115, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ji, Y.; Yu, X.; Zhong, F. Machinery investment decision and off-farm employment in rural China. China Econ. Rev. 2012, 23, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, Z.; Wen, F. From employees to entrepreneurs: Rural land rental market and the upgrade of rural labor allocation in non-agricultural sectors. Manag. World 2020, 36, 171–185. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tian, C.; Song, Y.; Boyle, C.E. Impacts of china’s burgeoning rural land rental markets on equity: A case study of developed areas along the eastern coast. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2012, 4, 301–315. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum, P.R.; Rubin, D.B. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983, 70, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, J.S. Changes in labor force participation in the united states. J. Econ. Perspect. 2006, 20, 27–46. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, S.; Liao, Y.; Zhang, J. The effect of housing wealth on labor force participation: Evidence from china. J. Hous. Econ. 2016, 33, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).