Territorial and Gender Differences in the Home Care of Family Members with Dementia

Abstract

1. Introduction

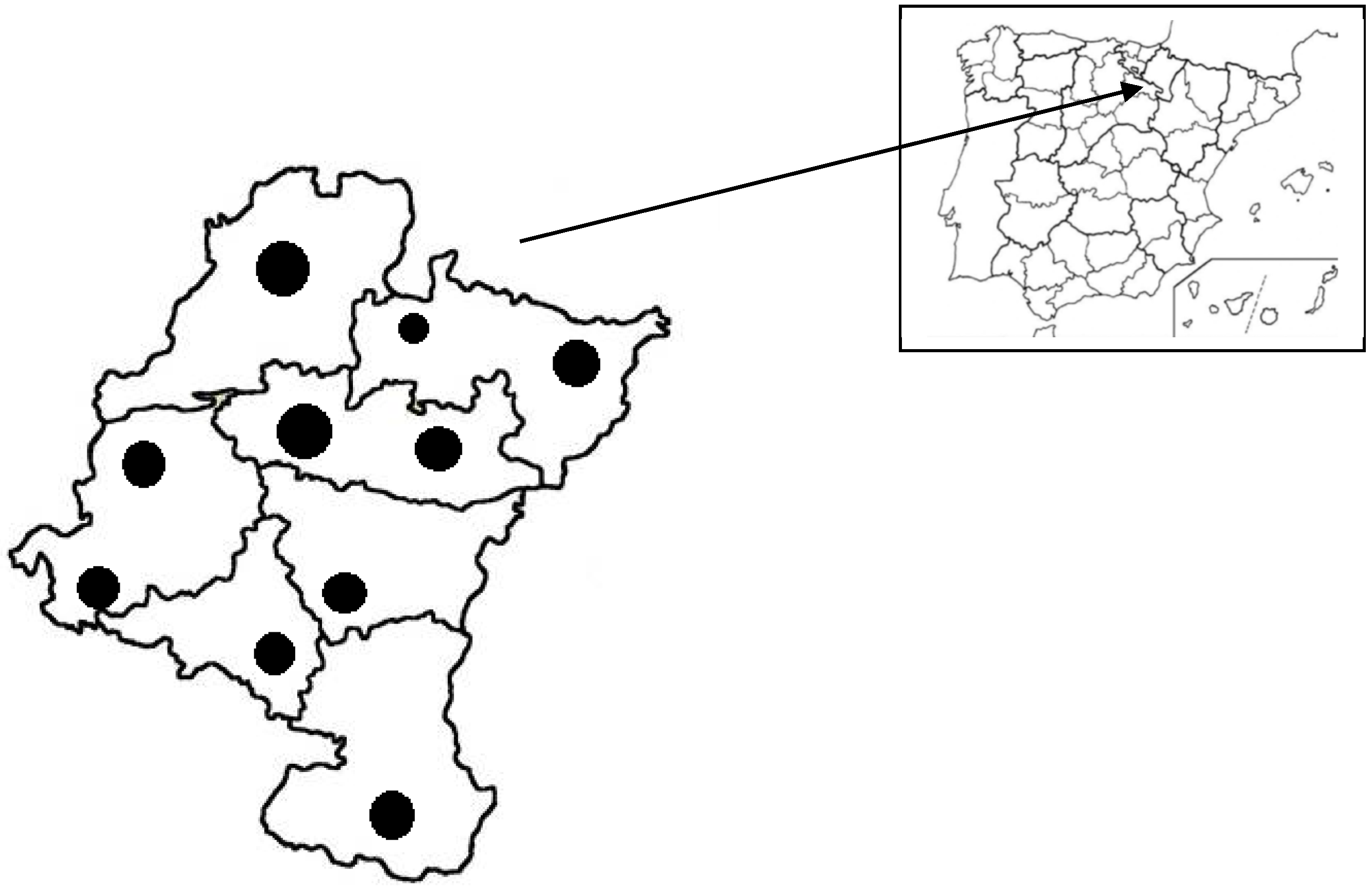

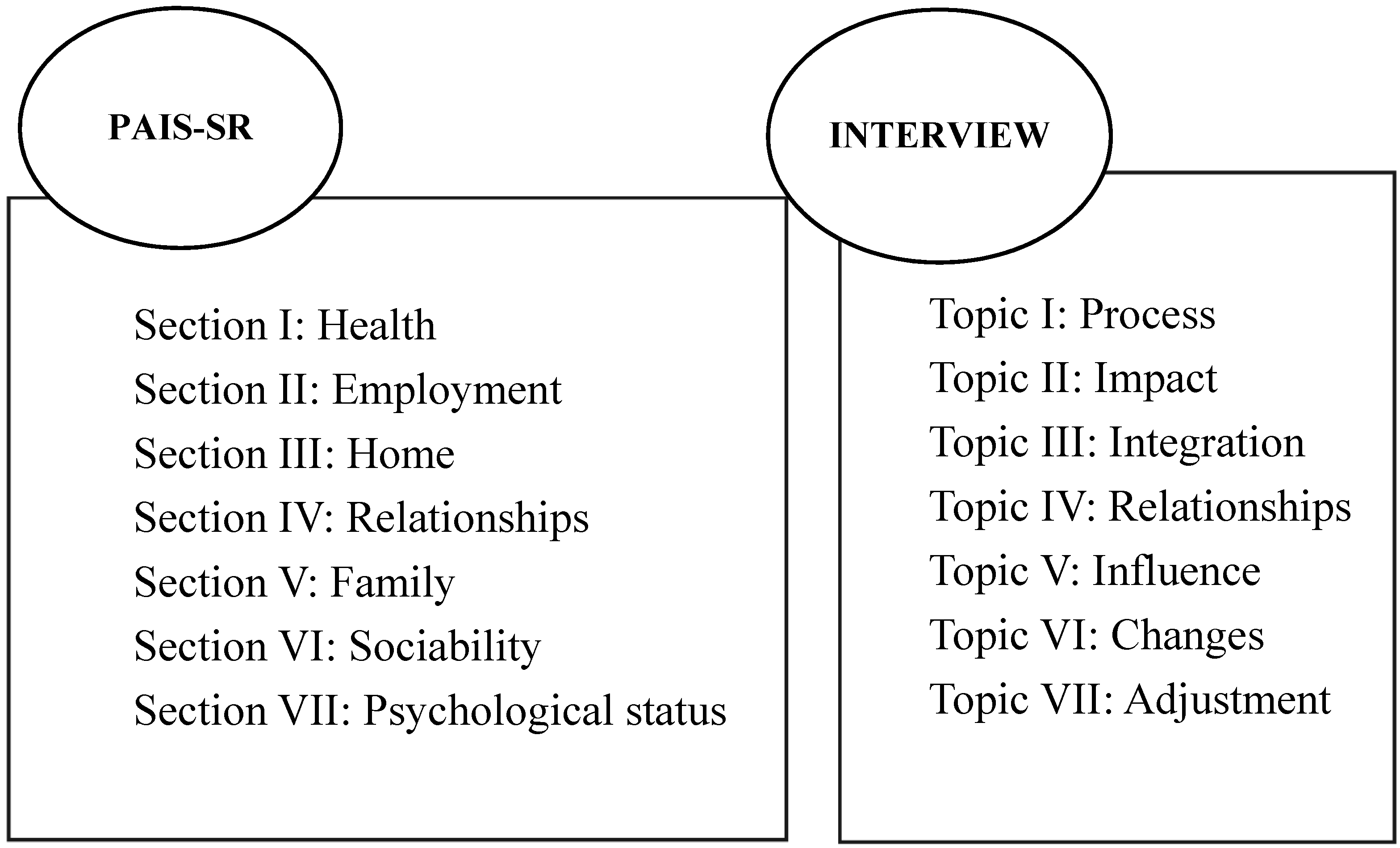

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Family Caregiver Profiles

3.2. Adjustment to the Care of Family Members with Dementia

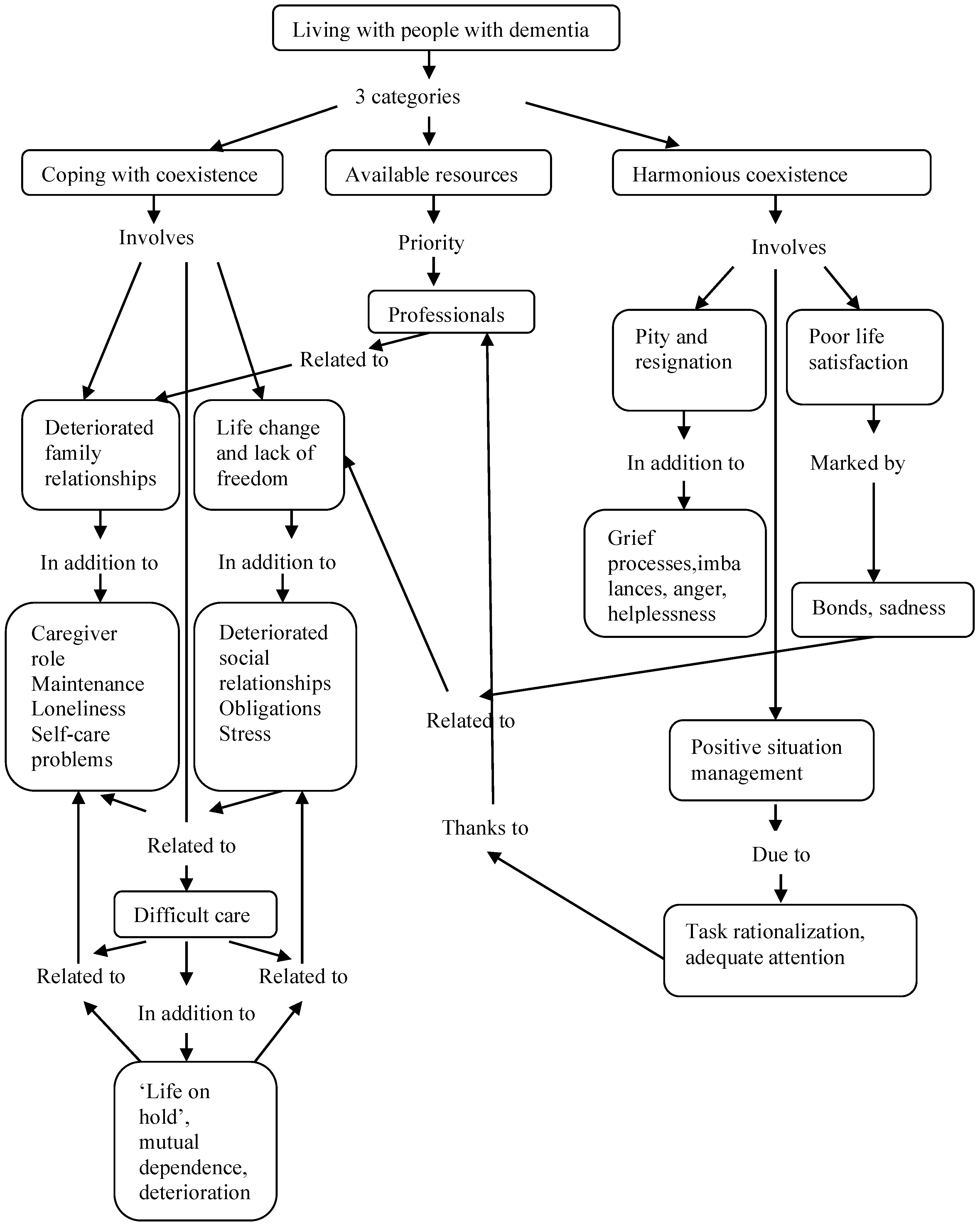

3.2.1. Care Experiences

3.2.2. Coping with and Adjusting to Caring for a Family Member with Dementia

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ehrilch, K.; Bstrom, A.M.; Mazaheri, M.; Heikkila, K.; Emami, A. Family caregivers’ assessments of caring for a relative with dementia: A comparison of urban and rural areas. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2014, 10, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Cámara, S.; Palomino-Moral, P.A.; Moral-Fernández, L.; Frías-Osuna, A.; Del Pino-Casado, R. Problemas en el proceso de adaptación a los cambios en personas cuidadoras familiares de mayores con demencia. Gac. Sanit. 2016, 30, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, A.; Pérez, L. Estrategias de afrontamiento en cuidadoras de personas con Alzheimer. Influencia de variables personales y situacionales. REDIS 2019, 7, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reig, E.; Goerlich, F.J.; Cantarino, I. Delimitación de Áreas Rurales y Urbanas a Nivel Local. Demografía, Coberturas del Suelo y Accesibilidad; Fundación BBVA: Bilbao, Spain, 2016; Available online: https://www.fbbva.es/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/dat/DE_2016_IVIE_delimitacion_areas_rurales.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Ubago, Y.; García, I.; Iraizoz, B.; Pascual, P. Why are some spanish regions more resilient than others? Pap. Reg. Sci. 2019, 98, 2211–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado-Roura, J.R. European Regional Policy. What can be learned. In Handbook of Regional Science; Fischer, M., Nijkamp, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 1053–1086. [Google Scholar]

- Amezcua-Aguilar, T.; Alberich-Nistal, T.; Sotomayor, E. Las personas mayores en el Estado de bienestar: Las políticas sociales en Alemania y España. Cuad. Trab. Soc. 2020, 33, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo Fernández, D. Análisis Comparado de los Modelos de Bienestar Social Vigentes en España, Alemania, Suecia y Estados Unidos; EAPN-Laboratorio de Alternativas: Madrid, Spain, 2018; Available online: https://www.fundacionalternativas.org/laboratorio/documentos/politica-comparada/analisis-comparado-de-los-modelos-de-bienestar-social-vigentes-en-espana-alemania-suecia-y-estados-unidos (accessed on 17 May 2021).

- Sousa, M.F.B.; Santos, R.; Turró-Garriga, O.; Días, R.; Dourado, M.C.N.; Conde-Salas, J.L. Factors associated with caregiver burden: Comparative study between Brazilian and Spanish caregivers of patients with Alzheimer´s disease. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2016, 28, 1363–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bien, B.; Wojszel, B.; Sikorska-Simmons, E. Rural and urban caregivers for older adults in Poland: Perceptions of positive and negative impact of caregiving. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2007, 65, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, J. Burden of Care Impacting Family Caregivers of Dependent Community-Dwelling Older Adults in Rural and Urban Settings of Southem Turkey: A Mosaic of Caregiver Issues and Recommendations; University of Dortmund: Dortmund, Germany, 2013; Available online: https://d-nb.info/1103587943/34 (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Madruga, M. Sintomatología psicológica en cuidadores informales en población rural y urbana. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Psychol. (INFAD) 2016, 2, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Agulló-Tomás, M.S.; Zorrilla-Muñoz, V.; Gómez-García, M.V. Aproximación socio-espacial al envejecimiento y a los programas para cuidadoras/es de mayores. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Psychol. (INFAD) 2019, 1, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.A.; Samper, T.; Marín, S.; Sigalat, E.; Moreno, A.E. Hombres cuidadores informales en la ciudad de Valencia. Una experiencia de reciprocidad. OBETS Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2018, 13, 645–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manso, M.E.; Sánchez, M.P.; Cuéllar, I. Salud y sobrecarga percibida en personas cuidadoras familiares de una zona rural. Clínica Y Salud 2013, 24, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dunn, D.J.; Price, D.; Neder, S. Rural caregivers of persons with dementia. Vis. J. Rogerian Nurs. Sci. 2016, 22, 16–24. Available online: https://www.societyofrogerianscholars.org (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Martín, A.; Rivera, J. Feminización, cuidados y generación soporte: Cambios en las estrategias de las atenciones a personas mayores en el medio rural. Rev. Prism. Soc. 2018, 21, 219–242. Available online: https://revistaprismasocial.es/article/view/2430 (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Santana, P. Introdução à Geografia da Saúde: Território, Saúde e Bem-Estar; Universidad de Coimbra: Coimbra, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto Villarino, M.J. Envejecimiento activo en el entorno rural. ¿Igualdad de oportunidades? Doc. Soc. 2017, 185, 149–166. Available online: https://www.caritas.es/main-files/uploads/2019/04/DocSocial185-1.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Wineman, A.; Alia, D.Y.; Anderson, C.L. Definitions of “rural” and “urban” and understandings of economic transformation: Evidence from Tanzania. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 79, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Moreno, E. Concepts, Definitions and Data Sources for the Study of Urbanization: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations Expert Group Meeting on Sustainable Cities, Human Mobility and International Migration, UN/POP/EGM/2017/8: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/unpd_egm_201709_s2_paper-moreno-final.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- OECD. Redefining Urban: A New Way to Measure Metropolitan Areas. 2012. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/regional/redefiningurbananewwaytomeasuremetropolitanareas.htm (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Dickins, M.; Goeman, D.; O’Keefe, F.; Iliffe, S.; Pond, D. Understanding the conceptualisation of risk in the context of community dementia care. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 208, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quesada-García, S.; Valero-Flores, P. Proyectar espacios para habitantes con alzhéimer, una visión desde la arquitectura. Arte Individuo Y Soc. 2017, 29, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lopes-Dos-Santos, M.C. La adaptación psicosocial a la enfermedad y calidad de vida de familiares cuidadores de personas con demencia en el proceso de convivencia. Cuad. Gerontológicos 2017, 22, 27–33. Available online: https://issuu.com/cuadernos_gerontologicos/docs/cuadernos_gerontolo_gicos_22 (accessed on 16 July 2021).

- Carrasco, C.; Borderías, C.; Torns, T. El Trabajo de Cuidado. Historia, Teoría y Políticas; Los libros de la Catarata: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Comas D’Argemir, D. La crisis de los cuidados como crisis de reproducción social. Las políticas públicas y más allá. In Periferias, Fronteras y Diálogos. Una Lectura Antropológica de los Retos de la Sociedad Actual; Universidad Rovira i Virgili: Barcelona, Spain, 2014; pp. 329–349. Available online: http://digital.publicacionsurv.cat/index.php/purv/catalog/book/123 (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Mayobre, P.; Vázquez, I. Cuidar cuesta: Un análisis del cuidado desde la perspectiva de género. Rev. Española Investig. Sociol. 2015, 151, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M. Los ‘cuidados informales’ de larga duración en el marco de la construcción ideológica, societal y de género de los servicios sociales de cuidados. Cuad. Relac. Labor. 2013, 30, 185–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcés, J.; Ródenas, F.J. La teoría de la sostenibilidad social: Aplicación en el ámbito de cuidados de larga duración. Rev. Int. Trab. Soc. Y Bienestar 2012, 1, 49–59. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/azarbe/article/view/151131 (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Canga, A. Hacia una «familia cuidadora sostenible». An. Del Sist. Sanit. Navar. 2013, 36, 383–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez Virto, L. Crisis en la familia. Síntomas de agotamiento de la solidaridad familiar. In VII Informe Sobre Exclusión y Desarrollo Social en España; FOESSA; Fundación Foessa: Madrid, Spain, 2014; Documento de Trabajo 3.7; Available online: http://www.foessa2014.es/informe/uploaded/documentos_trabajo/15102014151608_2582.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Silva, B.; Leite, A.; Santos, R.; Diré, G. A vulnerabilidade dos cuidadores de idossos com demencia: Revisão integrativa. Rev. Pesqui. Cuid. Fundam. 2017, 9, 882–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Granados, M.E.; Jiménez, A. Principios motivacionales en cuidadores informales hombres en el ámbito rural y ámbito urbano. ENE. Rev. Enfermería 2017, 11, 1. Available online: http://ene-enfermeria.org/ojs/index.php/ENE/article/view/606/cuidador_hombre (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Del Río Lozano, M.; García-Calvente, M.M.; Calle-Romero, J.; Machón-Sobrado, J.; Larrañaga-Padilla, M. Health-related quality of life in Spanish informal caregivers: Gender differences and support received. Qual. Life Res. 2017, 26, 3227–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, C.; Soronellas-Masdeu, M.; Alonso-Rey, N. El cuidado desde el género y el parentesco. Maridos e hijos cuidadores de adultos dependientes. Quad. L’institut Català D’antropologia 2017, 22, 82–98. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/155003475.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Mosquera, I.; Larrañaga, I.; Del Río Lozano, M.; Calderón, C.; Machón, M.; García, M.M. Gender inequalities in the impacts of informal elderly caregiving in Gipuzkoa: CUIDAR-SE study. Rev. Esp. Salud Pública 2019, 28, 93. Available online: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1135-57272019000100075 (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Martín-Vidaña, D. Masculinidades cuidadoras: La implicación de los hombres. españoles en la provisión de los cuidados. Un estado de la cuestión. Rev. Prism. Soc. 2021, 33, 228–260. Available online: https://revistaprismasocial.es/article/view/4095 (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Zygouri, I.; Cowdell, F.; Ploumis, A.; Gouva, M.; Mantzoukas, S. Gendered experiences of providing informal care for older people: A systematic review and thematic synthesis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD-Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económicos. Health at Glance: OECD Indicators; OECD: Paris, France, 2017; Available online: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/health-at-a-glance-2017_health_glance-2017-en#page1 (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, N.; Ding, L.; Feng, Y.; Tang, X.; Sun, L.; Zhou, C. Urban–rural disparities in informal care intensity of adult daughters and daughters-in-law for elderly parents from 1993–2015: Evidence from a National Study in China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungdah, S. (Ed.) Asian Countries Strategies towards the European Union in an Inter-Regionalist Context; National Taiwan University Press: Taipei, Taiwan, 2015; ISBN 978-986-350-056-8. GPN 1010303130. [Google Scholar]

- Tobío, C. Redes familiares, género y política social en España y Francia. Política Y Soc. 2008, 45, 87–104. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10016/19789 (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Huenchuan, S. Envejecimiento, familias y sistemas de cuidados en América Latina. In Envejecimiento y Sistemas de Cuidados: ¿Oportunidad o Crisis? Huenchuan, S., Roqué, M., Arias, C., Eds.; Documentos de proyectos; CEPAL–Colec: Santiago, Chile, 2006; pp. 11–28. Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/3859/1/S2009000_es (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Lopes, C.; Navarta-Sánchez, M.V.; Moler, J.A.; García-Lautre, I.; Anaut-Bravo, S.; Portillo-Vega, M.C. Psychosocial adjustment of in-home caregivers of family members with dementia and Parkinson’s disease: A comparative study. Parkinson’s Dis. 2020, 2020, 2086834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaut-Bravo, S.; Lopes-Dos-Santos, C. El impacto del entorno residencial en la adaptación psicosocial y calidad de vida de personas cuidadoras de familiares con demencia. OBETS Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2020, 15, 43–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaut-Bravo, S.; Laparra, M.; García, A. Desigualdades territoriales: Una realidad de largo recorrido. In La desigualdad y la exclusión que se nos queda: II Informe CIPARAIIS Sobre el Impacto Social de la Crisis 2007–2014; Laparra, M., de Eulate, T.G., Eds.; Bellaterra: Barcelona, Spain, 2015; pp. 169–214. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Virto, L.; Pérez Eransus, B. La austeridad intensifica la exclusión social e incrementa la desigualdad. Aproximación a las consecuencias de los recortes en servicios sociales a partir de la experiencia en Navarra. Rev. Española Del Terc. Sect. 2015, 31, 65–88. Available online: https://academica-e.unavarra.es/bitstream/handle/2454/33264/101_Mart%C3%ADnez_ExclusionSocial.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Martínez Virto, L.; Pérez Eransus, B. El modelo de atención primaria de servicios sociales a debate: Dilemas y reflexiones profesionales a partir del caso de Navarra. Cuad. Trab. Soc. 2018, 31, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaut-Bravo, S. (Ed.) El Sistema de Servicios Sociales en España; Aranzadi-Thomson Reuters: Cizur Menor, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Anaut-Bravo, S.; Carbonero-Muñoz, D. El rumbo de las políticas sociales de atención sociosanitaria de las situaciones de dependencia. In Las Políticas Sociales que Vendrán; Zambrano, C., Ed.; Aranzadi-Thomson Reuters: Cizur Menor, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Eransus, B.; Martínez Virto, L. (Eds.) Políticas de Inclusión en España: Viejos Debates, Nuevos Derechos: Un Estudio de los Modelos de Inclusión en Andalucía, Castilla y León, La Rioja, Navarra y Murcia; CIS: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- García, I.; Caballeira, J.D. Receta electrónica: Diferencias entre comunidades autónomas que afectan al acceso a los tratamientos y a la calidad de la atención farmacéutica. An. Del Sist. Sanit. Navar. 2020, 43, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, A.; Aranda, A.M.; García, G.; Ramírez, J.M.; Revilla, A.; Velasco, L.; Fuentes, M. Índice DEC 2020, 2021. Available online: https://directoressociales.com/project/indice-dec-2020 (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Porcino, A.J.; Verhoef, M.J. The use of mixed methods for therapeutic massage research. Int. J. Ther. Massage Bodyw. 2010, 3, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sánchez, M.C. La dicotomía cualitativo-cuantitativo: Posibilidades de integración y diseños mixtos. Campo Abierto 2015, 1, 11–30. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317156352 (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- World Health Organization—WHO. Global Action Plan on the Public Health Response to Dementia 2017–2025; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://www.alzint.org/what-we-do/partnerships/world-health-organization/who-global-plan-on-dementia/ (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- Derogatis, L.R. The psychosocial adjustment to illness scale (PAIS). J. Psychosom. Res. 1986, 30, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullinger, M.; Alonso, J.; Apolone, G.; Leplège, A.; Sullivan, M.; Wood-Dauphinee, S.; The IQOLA Project Group. Translating health status questionnaires and evaluating their quality: The IQOLA Project approach. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1998, 51, 913–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portillo, M.C.; Senosiain, J.M.; Arantzamendi, M.; Zaragoza, A.; Navarta, M.V.; Díaz de Cerio, S.; Riverol, M.; Martínez, E.; Luquin, M.R.; Ursúa, M.E.; et al. Proyecto ReNACE. Convivencia de pacientes y familiares con la enfermedad de Parkinson: Resultados preliminares de la Fase, I. Revista Científica Sociedad Española de Enfermería y Neurología 2012, 35, 32–39. Available online: https://www.sedene.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Revista-36.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Derogatis, L.R.; Derogatis, M.A. PAIS & PAIS-SR: Administration, Scoring & Procedures Manual-II Clinical Psychometric Research. 1990. Available online: https://eprovide.mapi-trust.org/instruments/psychosocial-adjustment-to-illness-scale (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- García-Bellido, R.; González, J.; Jornet, J.M. SPSS: Análisis de Fiabilidad Alfa de Cronbach; Universitàt de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 2010; Available online: https://www.uv.es/innomide/spss/SPSS/SPSS_0801B.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2020).

- Lê, S.; Josse, J.; Husson, F. FactoMineR: An R Package for Multivariate Analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 25, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peduzzi, P.; Concato, J.; Feinstein, A.R.; Holford, T.R. Importance of events per independent variable in proportional hazards regression analysis II. Accuracy and precision of regression estimates. Accuracy and precision of regression estimates. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1995, 48, 1503–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook; SAGE: Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Garzón, M.; Pascual, Y. Relación entre síntomas psicológicos-conductuales de pacientes con enfermedad de Alzheimer y sobrecarga percibida por sus cuidadores. Rev. Cuba. Enfermería 2018, 34, 2. Available online: http://revenfermeria.sld.cu/index.php/enf/article/view/1584/346 (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Tartaglini, M.F.; Ofman, S.D.; Stefani, D. El sentimiento de sobrecarga y afrontamiento en cuidadores familiares principales de pacientes con demencia. Rev. Argent. Clínica Psicológica 2010, 19, 221–226. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/2819/281921798003.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Brodaty, H.; Donkin, M. Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2009, 11, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raggi, A.; Tasca, D.; Panerai, S.; Neri, W.; Ferri, R. The burden of distress and related coping processes in family caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease living in the community. J. Neurol. Sci. 2015, 358, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.K.; Park, M.; Lee, Y.; Choi, S.H.; Moon, S.Y.; Seo, S.W.; Park, K.W.; Ku, B.D.; Han, H.J.; Park, K.H.; et al. Influence of personality on depression, burden, and health-related quality of life in family cargivers of persons with dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2017, 29, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Santos, A.E.; Facal, D.; Vicho de la Fuente, N.; Vilanova-Trillo, L.; Gandoy-Crego, M.; Rodríguez-González, R. Gender impact of caring on the health of caregivers of persons with dementia. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 104, 2165–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Río-Lozano, M.; García-Calvente, M.M.; Marcos-Marcos, J.; Entrena-Durán, F.; Maroto-Navarro, G. Gender identity in informal care: Impact on health in spanish caregivers. Qual. Health Res. 2013, 23, 1506–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, F.E.; Manquián, E.; Rivasa, G. Bienestar psicológico, estrategias de afrontamiento y apoyo social en cuidadores informales. Psicoperspectivas 2016, 15, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antelo, P.; Espinosa, P. La influencia del apoyo social en cuidadores de personas con deterioro cognitivo o demencia. Rev. De Estud. E Investig. En Psicol. Y Educ. 2017, 14, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, M.; Márquez, F.; Campos, S.; Alcayaga, S. Adaptando mi vida: Vivencias de cuidadores familiares de personas con enfermedad de Alzheimer. Gerokomos 2018, 29, 54–58. Available online: https://scielo.isciii.es/pdf/geroko/v29n2/1134-928X-geroko-29-02-00054.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Camarero-Rioja, L.; Cruz, F.; Oliva, J. Rural sustainability, inter-generational support and mobility. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2016, 23, 734–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losada, A.; Márquez, M.; Vara-García, C.; Gallego, L.; Romero, R.; Olazarán, J. Impacto psicológico de las demencias en las familias: Propuesta de un modelo integrador. Rev. Clínica Contemp. 2017, 8, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comas D’Argemir, D.; Soronellas-Masdeu, M. Men as carers in long-term caring: Doing gender and doing kinship. J. Fam. Isuues 2018, 40, 315–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abellán, A.; Ayala, A.; Pérez, J.; Puyol, R.; Sundström, G. Los Nuevos Cuidadores; Observatorio La Caixa: Barcelona, Spain, 2018; Available online: https://observatoriosociallacaixa.org/es/-/los-nuevos-cuidadores (accessed on 5 October 2021).

- Durán, M.A. Dependientes y cuidadores: El desafío de los próximos años. Rev. Del Minist. Trab. Y Asun. Soc. 2006, 60, 57–73. Available online: https://digital.csic.es/handle/10261/100683 (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Navarro, M.; Jiménez, L.; García, M.C.; De Perosanz, M.; Blanco, E. Los enfermos de Alzheimer y sus cuidadores: Intervenciones de enfermería. Gerokomos 2018, 29, 79–82. Available online: https://scielo.isciii.es/pdf/geroko/v29n2/1134-928X-geroko-29-02-00079.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- Lorenzo, T.; Millán-Calenti, J.C.; Lorenzo-López, L.; Maseda, A. Caracterización de un colectivo de cuidadores informales de acuerdo a su percepción de la salud. Aposta Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2014, 62, 1–20. Available online: http://www.apostadigital.com/revistav3/hemeroteca/jcmillan1.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- Agulló-Tomás, M.S.; Zorrilla-Muñoz, V. Technologies and Images of Older Women. In Human Aspects of IT for the Aged Population. Technology and Society. HCII 2020. Copenhagen, Dermark. Proceedings, Part III Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Gao, Q., Zhou, J., Eds.; LNCS 12209; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goerlich, F.J.; Reig, E.; Cantarino, I. Construcción de una tipología rural/urbana para los municipios españoles. Investig. Reg. J. Reg. Res. 2016, 35, 151–173. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10017/27144 (accessed on 20 October 2021).

| Type of Locality | Number of Municipalities | Municipalities Percentage (%) | Population | Population Percentage (%) | Participants Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural * | 261 | 95.96 | 281427 | 43.75 | 18.2 |

| Urban ** | 11 | 4.04 | 361.807 | 56.25 | 81.8 |

| Urban Localities | Rural Localities | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 22 | 9 | 31 |

| Female | 63 | 41 | 104 |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married men | 15 | 6 | 21 |

| Married women | 43 | 31 | 74 |

| Single men | 5 | 3 | 8 |

| Single women | 11 | 9 | 20 |

| Men other | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Women other | 9 | 1 | 10 |

| Employment Situation | |||

| Men full-time | 7 | 4 | 11 |

| Women full-time | 16 | 9 | 25 |

| Men part-time | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Women part-time | 13 | 7 | 20 |

| Retired men | 13 | 3 | 16 |

| Retired women | 13 | 7 | 20 |

| Male homemakers | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Female homemakers | 16 | 14 | 30 |

| Men other | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Women other | 5 | 4 | 9 |

| Education | |||

| Men basic education | 7 | 4 | 11 |

| Women basic education | 29 | 25 | 54 |

| Men vocational education | 4 | 5 | 9 |

| Women vocational education | 7 | 4 | 11 |

| Men secondary education | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Women secondary education | 13 | 4 | 17 |

| Men higher education | 7 | 0 | 7 |

| Women higher education | 14 | 8 | 22 |

| Kinship | |||

| Sons | 13 | 7 | 20 |

| Daughters | 48 | 24 | 72 |

| Male spouses | 9 | 2 | 11 |

| Female spouses | 11 | 13 | 24 |

| Men other | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Women other | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| Care Provenance | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|

| Professional | 50 |

| Cohabiting caregivers | 36.7 |

| Relatives | 13.3 |

| PAIS-SR * | Urban | Rural |

|---|---|---|

| Section III: Domestic environment <12 good perception | 12.6 | 12 |

| Section VI: Social environment <9 good perception | 10.2 | 10.6 |

| Section VII: Psychological distress <10.5 no presence of discomfort | 10.1 | 4.4 |

| Domestic Environment Section III | Social Environment Section VI | Psychological Distress Section VII | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | |||

| Rural | 11.8 | 9 | 4.55 |

| Urban | 12.12 | 11.12 | 10.15 |

| Women | |||

| Rural | 12.47 | 10.81 | 4.76 |

| Urban | 12.41 | 9.36 | 10.32 |

| S2x | Domesticenvironment Section III | Socialenvironment Section VI | Psychologicaldistress Section VII |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | |||

| Rural | 3.33 | 0 | 0.25 |

| Urban | 7.55 | 6.12 | 0.98 |

| Women | |||

| Rural | 9.04 | 5.92 | 2.81 |

| Urban | 13.22 | 10.76 | 10.03 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anaut-Bravo, S.; Lopes-Dos-Santos, M.C. Territorial and Gender Differences in the Home Care of Family Members with Dementia. Land 2022, 11, 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11010113

Anaut-Bravo S, Lopes-Dos-Santos MC. Territorial and Gender Differences in the Home Care of Family Members with Dementia. Land. 2022; 11(1):113. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11010113

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnaut-Bravo, Sagrario, and María Cristina Lopes-Dos-Santos. 2022. "Territorial and Gender Differences in the Home Care of Family Members with Dementia" Land 11, no. 1: 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11010113

APA StyleAnaut-Bravo, S., & Lopes-Dos-Santos, M. C. (2022). Territorial and Gender Differences in the Home Care of Family Members with Dementia. Land, 11(1), 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11010113