Abstract

A growing number of urban interventions, such as culture-led regeneration strategies, has emerged alongside growing awareness of the concept of re-urbanization. These interventions evolve to create a holistic urban vision, with aims to promote social cohesion and strengthen local identity as opposed to traditional goals of measuring the economic impact of new cultural developments. Szczecin’s, Poland urban strategy is focused on the expansion of culture—a condition for improving the quality of life and increasing the city’s attractiveness. This article assesses the potential for re-urbanization of Szczecin’s flagship cultural developments. Questionnaire surveys and qualitative research methods were used to assess the characteristics that distinguish cultural projects in the formal, location-related, functional, and symbolic layers, as well as examining their social perception. The results show that the strength of these indicators of urbanscape identity affects how the cultural developments are assessed by the society. Semiotic coherence and functional complexity of the structures have a significant impact on the sense of identification, while their monumentality and exposure contribute to the assessment of the impact on their surroundings. A development with a firm identity, embedded in the city’s tradition not only preserves the cultural heritage of the city but also makes inhabitants feel association with the new project.

1. Introduction

1.1. Context of the Study

Identified in urban areas of highly developed countries since 1960s, degradation and depreciation of city centers have forced a comprehensive and thorough approach not only to changes of the city image, but also the transformation of the city’s functioning concept, especially that industry and manufacturing have ceased to be the main driver for urban development. It seems that the concept of re-urbanization has played a major role in the long-term urban transforman. Since its establishing in the early 1980s as a part of Leo Klassen’s cyclical urban development model, the concept has defined directions and relations of demographic changes from a city and region point of view, while taking into consideration their social, economic, and urban contexts. The concept of re-urbanization has shed new light on issues pertaining to city centers and added broader, structural, and interdisciplinary perspective to urban policies.

During the same period, culture started to play an increasingly important role. It was perceived as a means to improve and remodel the industrial image of a city. It was also seen as a driver for city’s economic growth by boosting consumption and a starting point for physical renovation of core city centers [1,2]. Thus, culture has become a part of urban policies based on flagship projects implemented in city centers. These projects were designed as catalyzers for the regeneration of degraded centers and magnets for new developments [3]. In 1997, the success of Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao by star architect Frank Gerry contributed much to the idea of the culture-led regeneration. The “Cinderella transformation”, as referred to by Giovannini (following Klingmann) [4] (p. 238), well reflects its scale and impact on the city. As noted by Alaily-Mattar et al. [5] (p. 169), since the opening of the facility “the idea that architecturally exceptional signature buildings can play a decisive role in urban regeneration and urban competitiveness has received substantial coverage in the academic as well as the mainstream media”. According to Miles and Paddison [6] (p. 833), “the idea that culture can be employed as a driver for urban economic growth has become part of the new orthodoxy by which cities seek to enhance their competitive position.”

Analyses and criticism of culture-led strategies helped to revise and re-evaluate their goals and expected effects while emphasizing the sense of community, local identity and sense of place. Contemporary culture-led strategies evolve towards a holistic vision which departs from measuring economic effects of culture infrastructure development and focus on social cohesion and strengthened cultural identity of a city. The question of social approval to flagship cultural projects has become increasingly important if we consider consequences of re-urbanization strategies. The same applies to the scope and use of local cultural heritage, place identity, and existing contexts of these projects. It is important to determine whether projects, designed to enhance quality of life, actually use and strengthen endogenic urban resources, both cultural (material and symbolic) and social in the sense of their territorial identity.

When analyzing the effectiveness of the re-urbanization strategy, it is worth asking whether the flagship cultural projects completed do use and reinforce the existing cultural resources of the city and its social potential. The question is whether they continue to the history and the specific nature of a place or respect the existing context. On the other hand, it is worth checking how residents perceive the projects, whether projects reinforce their sense of belonging, or whether they make people feel proud? Do the dwellers know the developments, do they identify with the structures and do they think the structures are important to improving the city’s image? These questions were asked by the author in conducting this study.

1.2. Research Scope and Objectives

In 2014, the Marshal of the Western Pomerania Province, Olgierd Geblewicz solemnly opened the Small Theatre in the center of the city of Szczecin, where he uttered these important words: “I believe that culture has an influence on the regeneration of space.” An attempt to verify this act of faith is a scientific challenge. Assuming that the flagship cultural structures are catalyzing the renewal and revival of the city, there is the endogenic impact associated with the quality of residents’ life and the exogenic impact associated with the image and the economic condition of the city [7]. The locational, spatial, functional and semiotic characteristics of the projects completed determine the two areas of impact of cultural developments on the re-urbanization.

The Szczecin Development Strategy, which encompasses features of a re-urbanization model, puts much emphasis on the expansion of culture as a precondition for improved quality of life and enhanced attractiveness of the city. The document implements the vision of Floating Garden 2050, a branding project, which focuses on the transformation of the post-industrial image of the city [8]. Since its launch in 2008, the city has initiated the construction of eleven large public culture projects. Nine of them are covered by this study. The study compares the social assessment of cultural facilities and their features that determine their symbolic, spatial, local, and functional qualities, with special emphasis on the integration of a place-based identity as their endogenic potential.

The purpose of this article is to assess the potential for re-urbanization of the flagship cultural developments in Szczecin, understood as the elements of culture-led re-urbanization strategy, in terms of the use of endogenous sources of identity and the impact of these developments on the population. This study evaluates several important aspects about the effects of current urban policy in Szczecin. First, it assesses the locational, spatial, and functional characteristics of the flagship cultural developments in Szczecin. Secondly, it examines the special use of local cultural heritage and the identity of a place, including the source and the strength of the symbols of developments completed in the relationship between the cultural institution and the cultural structure (building). Finally, it examines the social impact of these developments, in terms of recognition, relevance to the residents and how they assess the impact of developments on the environment. This allows us to identify possible links between the objective characteristics of cultural development and its social perception. We will also overview the factors of the strengthening of local identity, including public acceptance and a sense of belonging to a place. It is particularly important in the case of cities with a disrupted identity due to the replacement of their inhabitants after WW II. There, the building of local communities and their affiliation with the city has been more difficult.

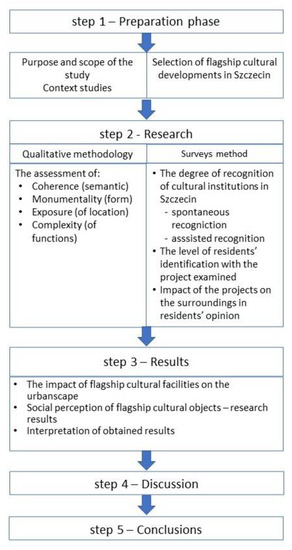

In following the diagram illustrating framework of the study is shown (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The framework of the study. Source: Authors.

2. Research Perspectives on Culture-Led Regeneration within the Model Re-Urbanization

Re-urbanization has been a process identified and studied in European cities since the early 1980s. At that time, the concept was presented by a research team led by Leo Klaassen, within a city model being developed [9]. This model being considered as cyclical sets out a pattern of demographic changes taking place in urban agglomerations, broken down into a central area of the city (core) and by its suburbs (ring). At that time, four stages of urban development were identified and characterized: urbanization, sub-urbanization, de-urbanization, and finally re-urbanization, the latter being considered a special stage, which has not yet occurred and is expected to take place. The model originally defines re-urbanization as a concentration of population in the central area of the city, with a general population decline in the entire agglomeration due to depopulation of the suburbs, partly moving of the center [9]. However, according to the contemporary research into the demographic change in European cities over recent decades, re-urbanization defined in this way has not occurred in any significant number of cities [10,11,12]. Although the population of central areas is actually increasing as part of a long-term process caused by an increasing attractiveness of housing [13,14,15], the population of the suburbs is not declining, so the migration that is taking place is not the return to the center, as Klaassen had expected.

Despite the disapproving voices that the model received [16,17,18], including the impossibility of confirming the occurrence of re-urbanization defined in its model, it must be acknowledged that the Klaassen’s concept has become a great scientific challenge for subsequent researchers seeking to verify the hypotheses. The analytical strength of this model is its urban-and-regional perspective and thereby the inclusion of suburban areas [10]. Importantly, from the perspective of the following research, the model has generated strong interest among researchers in the central areas of cities. Thereby, it contributed to the progress in studies of the city center renewal, the growth of centers’ importance, stabilization and intensification of the housing function within them and studies of the factors driving these processes. They result in a real increase in the city center population in many European cities, thanks to the policies implemented to improve the quality of life in a city. The Klaassen model is still being revised and developed, and the concept of re-urbanization has become the most important element of the model, has been redefined and generated knowledge of urbanization processes.

The concept of re-urbanization contains several layers of dual distinction between its former and contemporary meaning. Firstly, being a phenomenon of urban regeneration, it is seen in two spatial perspectives: as the development of the entire agglomeration or as the regeneration of city centers [19]. Re-urbanization is perceived differently in the field of social geography than in urban studies. In the first approach, it is understood as a socio-demographic model that is conditional on the housing market, while in the second approach, it gains spatial and cultural assets. Re-urbanization is analyzed in quantitative terms, looking at the data on the population of city centers relative to that of agglomerations and the dynamics of changes. It is also analyzed by qualitative methods, considering the types of households and the characteristics of the urban environment. However, as part of the evolving research into the city development model, there is a shift from quantitative approaches to qualitative indicators, where the latter can explain the phenomenon of re-urbanization [1,18,20].

At present, re-urbanization is seen as part of the wider phenomenon of urban changes, and the re-urbanization has been adopted as a term to describe the development of the urban system [21]. The term is often used in modern urban studies relatively freely to denote several “pro-urban” town-planning processes, such as urban renaissance, urban resurgence or back-to-the-city movement, etc. [22,23]. Re-urbanization is understood as the process of long-term stabilization of central areas, including the readiness of their current residents to remain there and the affluence of new people in these areas [24]. The main re-urbanization potentials for the revival of a city’s central area—to make it attractive to live in and make the entire agglomeration competitive—include the richness and uniqueness of the cultural heritage of cities, the diversity of cultural institutions, the concentration and diversity of functions, the developed infrastructure, and the pedestrian-friendly environment. Culture, tourism and administration were seen as flagship in restoring the traditional role of the city center [1,25,26].

The policy to reverse the urban decline and reshape the urban negative image, implemented through cultural strategies, took different forms, and put emphasis on different aspects. The introduction of attractive cultural infrastructure in the city center has become one of the ways to re-urbanize the city center and attract residents and tourists. The construction of prestigious cultural structures was seen as a starting point for the physical restoration of central urban areas and a driving force for economic development, by generating more consumption [1,2]. Griffiths [27] (p. 254) gives three classes of emerging models of cultural strategy, based on three urban development perspectives: “the promotional model”, “the cultural industries model”, and “the integrationist model”. The first model that has a spatial dimension focuses on the physical and functional changes of the city result from the integration of cultural structures into a visually attractive, mixed-use development that attracts people to the center. The second model focuses on the economic dimension, where the role of cultural structures in the economic development of the city is emphasized. The third model defines the social perspective of the city’s development, promotes the value of the city’s life and focuses on aspects of the sense of community, identification with place and local identity. One of the most important impulses for the development of the idea of culture-led regeneration in Europe was the European Capital of Culture initiative. Born in 1983, it has over time become a facilitator of change for the development of cities that were not traditional cultural centers, carrying a strong potential for lasting effects on the city’s economy, image, and space. Examples of such cities are Glasgow, Liverpool, Košice, and Pafos [28,29,30].

The cultural strategies that have been implemented for thirty years are still becoming more popular, although researchers also point to the risks they pose. Cultural re-urbanization strategies—focused on building a new cultural infrastructure in city centers and creating a new image of the city desirable by business elites—entail the risk of confusion and unpredictability in the distribution of benefits, implementation costs, and associated spatial inequalities [31,32,33], with the local community being most affected by this problem. This is often the result of the too strong link between cultural developments and commercial housing development projects [34], which entails the risk of creating “cultural ghettos”, leading to the gentrification of the area, the removal and deterrence of poorer groups of the community [35], and results in the trend toward locating the flagship cultural structures outside the de facto degraded areas, where a project would be at too great risk. The article also highlights the revaluation of the assumed and expected economic role of culture. The potential of cultural strategies to impact the city and the community is pictured smaller than in reality because of too much emphasis on the economic effects of the strategies implemented, such as increasing the labor market, developing tourism, and attracting external developments [6,36,37].

The commercially-oriented and global competition-oriented urban cultural strategies neglect to include local cultural values and specificities [6,36,38]. In addition, researchers in this area see that the local symbolic context is driven out [39] and there is a threat of the unification of urban landscapes, which is due to the completion of flagship cultural developments. The desired iconicity of these structures becomes widespread [40], and the pursuit of renowned architect names is considered a proof of the modernness and competitive edge of almost every major city. This type of architecture is commonly visually stunning, but it lacks real content and meaning [40]. As a result, cities become more and more similar to each other. It is indicated that culture and place become a commodity and the solutions used are increasingly homogeneous [36,41], a clear example of which is a series of thematic repetitions in the development of urban waterfronts. In the longer term, this also has an economic dimension, since, according to Bassett et al. [36] (p. 153): “that undermines uniqueness and the prospect of reaping monopoly advantage”.

Currently, international agreements, such as the Urban Agenda for the EU and the New Urban Agenda, highlight the need to introduce an integrated, sustainable and cross-cutting approach to the multi-faceted urban policy [42,43]. The integration of the place-based and people-based approaches into strategic urban planning [42] is very much desired in culture-led regeneration policies. This fits into the third integration model identified by Griffiths. Urban strategies based on the culture-led regeneration of the city center are a part of a broader issue, namely the establishing of the city development model. Such a model should focus on a long-term stability and enhanced importance of city centers, including intensive development of a residential function and rural-urban linkages typical for the re-urbanization concept and the contemporary Urban Agenda [42].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Context of the Case Study

Szczecin is special being located on the border, on the Baltic coast and on the Odra River. The location of the city has influenced its identity and cultural image, which is created by a complex and multinational history as it was part of many countries: Duchy of Pomerania, Sweden, Brandenburg, Prussia, Germany; and since 1945, the city has belonged to Poland [44]. Therefore, Szczecin is a city of a unique identity and its contemporary landscape is like a palimpsest, a writing material repeatedly covered with new sets of characters, symbols, and names while the existing ones were often erased, unwanted, and illegible. Present-day Szczecin, as a historic shipbuilding and port center, is also facing post-industrial image and post-industrial development problems. As in other post-socialist large cities, the economic, social, and consequently urban transformations began in Szczecin at the beginning of the 1990s, the city entered the stage of de-urbanization, and the problem of downtown degradation was growing rapidly. In 2009, the largest shipyard in the city bankrupted, symbolically closing its industrial era. However it is worth to remember that due to the state-ownership based management and shortage of investment in renovation until 1989, a dilapidation of historical buildings began much earlier. At the same time, modernist projects implemented in 1950s and 1960s significantly changed the structure of the then core city center, chiefly the Old Town, which inflicted severe damage during the war.

By accepting and attempting to exploit the changes that have taken place, the city has turned to re-brand and adopt a completely new, bold vision of development. In 2008, Szczecin announced the brand and the image concept of Floating Garden 2050 and adopted a long-term management strategy related to them. Regarding its visual and semantic dimensions, the vision of Floating Garden 2050 is based on location and structural qualities of the city, in particular vast bodies of water interlaced with urbanized land. The objective of the vision is to turn Szczecin into “the most visionary city in Europe”. The vision highlights such values as openness, freedom, and harmony between man and nature. It is based on the making use of natural location and the functional, spatial, and symbolic return of the city to the water. By promoting openness, the vision emphasizes and uses endogenous factors: the role of its own complicated identity and the unique landscape. The unique interweaving of the city with water and greenery becomes a motif that forms the brand logo. The adoption of the Szczecin Development Strategy 2025 as a document with a planning dimension [45] in 2011 develops and makes more specific the vision of the Floating Garden. Although the Strategy document does not mention “re-urbanization”, this development model is clear there. Moreover, while the concept of cultural regeneration is not mentioned, it can clearly be found there by close reading. The Strategy defines four strategic objectives: a city of high quality of life, a city of innovative economy, a city with high intellectual potential, and an attractive metropolitan city. As part of the first objective, it is planned to “make Szczecin one of the national cultural centers” by creating a social-and-cultural heart of the city in the inner-city development area and on the industrial brownfields of Międzyodrze. This will be in parallel with the intense regeneration of these housing areas [45]. A rich cultural offer is mentioned alongside natural resources as a condition for creating an attractive and environmentally friendly environment for residents, investors, and tourists [45].

3.2. Subject of the Study

Since the vision of Floating Garden 2050 was announced in 2008, a number of cultural structures with a supra-local character and range have been built or thoroughly retrofitted in Szczecin. These include four categories of projects: thorough reconstruction and modernization of existing buildings (old institutions–old structures), construction of new buildings in a new place for the previously functioning cultural institutions (old institutions–new structures), creation of new cultural institutions, implemented either by adapting historical buildings for new purposes (new institutions–old structures) or by building new buildings (new institutions–new structures).

The first category of developments includes the reconstruction of the Castle Opera House and the expansion of the Polish Theatre. The second category includes the construction of new premises for the Pleciuga) Puppet Theatre and for the Szczecin’s Philharmonic Concert Hall. The third, the most numerous category, includes five projects: the creation of the Museum of Technology and Transportation in the former tram depot, the Academy of Art in the Palace under the Globe, the TRAFO Center of Contemporary Art Center for Contemporary Art in a post-industrial building, the Small Theatre in the former city gate, and the new Lentz Villa cultural facility with an as-yet-unspecified role in the renovated villa. The last category is the Upheavals Dialogue Center Museum and the Maritime Science Center. All these developments are public cultural institutions, belonging either to the local government of the Szczecin Municipality or to the local government of the West Pomeranian Province. The exception is the Small Theatre, which is a private institution of culture. However, all projects have received public funding, including grants under the financing mechanisms of regional policy of the European Union or the European Economic Area. Eight of these projects have been handed over into operation, three are still being completed: The Maritime Science Center, the Polish Theatre and Lentz Villa.

All these cultural projects are located in the Śródmieście district—the downtown of Szczecin, most of which are located centrally and concentrated within the historical boundaries of the Old Town. An exception is the Museum of Technology and Transportation, which is located on the outskirts of Śródmieście, in the historic Niebuszewo-Bolinko district. At a slightly smaller distance, but also beyond the very core of the city, there are the Pleciuga Puppet Theatre and the Lentz Villa. The two new buildings of the Szczecin Philharmonic Concert Hall and the Upheavals Center for Dialogue Museum are directly adjacent, while the remaining buildings, despite their objectively close proximity, remain spatially dispersed. Given the motto of the FG vision, it is worth mentioning that there is only one building directly on the water, the Maritime Science Center, despite the fact that originally the city planned to concentrate the construction of several flagship cultural developments on the post-port island of Łasztownia. The complicated ownership of the area, the difficult to estimate costs of transformation and making a connection between the area and the center on the other bank of the river, as well as the less perceptible and less understood absence of cultural tradition in Łasztownia, caused the city to give up the location of individual structures there and the new cultural district has never been established. The other developments were blended into the city’s urban fabric, affecting the surroundings in different ways and drawing from the tradition of the place in different ways. Significantly, none of the public cultural developments completed since 2008 has been included in the area of regeneration, as defined in 2018 in the Local Urban Regeneration Plan [39] although most of them are adjacent to the area. Therefore, all buildings remain outside the area of integrated regeneration measures.

This study focuses on public investments in the supra-local infrastructure of culture and arts, implemented in the area of Szczecin City Center since in 2008 the City adopted a new vision and brand for the development of Floating Garden 2050. The year 2008 seems to be a good starting point for an analysis of the identity-based impact of cultural projects on the city and its inhabitants, even though the initiative to establish new cultural institutions in Szczecin and create new premises for the existing ones was, for many of them, somewhat earlier, and linked to Poland’s accession to the EU in 2004. However, the moment of adopting the official vision of Szczecin’s development, which is of re-urbanization nature, has strategically justified and has made cultural projects more rapid. Of all public projects in culture and art of a trans-local range, which have been completed since 2004, the studies dealt with structures put into service and one structure under construction. The not yet completed Maritime Science Center was taken into account due to its unique function, monumental form and exposure to the waterfront, which can potentially translate into high recognition of the project and its importance for the community. Finally, nine cultural developments were included in both social research and qualitative analysis (Table 1; Figure 2). In the recognition survey; however, these developments were analyzed against a broader background of all such facilities in Szczecin (Additionally: The Castle of the Pomeranian Dukes, Polish Theatre, Contemporary Theatre, National Museum, The Pomeranian Library, Kana Theatre, Krypta Theatre.).

Table 1.

List of cultural developments. Types of developments (construction project): NI-NS: new institution–new structure, NI-OS: new institution–old structure (adaptation), OI-NS: old institution–new structure, OI-OS: old institution–old structure (modernization/revaluation), source: Authors, [46,47].

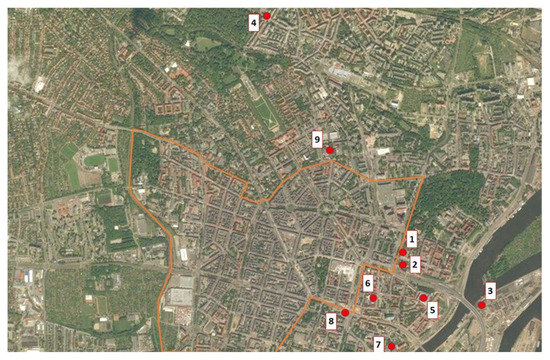

Figure 2.

The area of regeneration, as defined in 2018 in the Local Urban Regeneration Plan and location of nine cultural developments in the city of Szczecin: 1—Philharmonic Concert Hall in Szczecin, 2—Upheavals Dialogue Center Museum, 3—The Maritime Center of Science, 4—Museum of Technology and Transportation, 5—The Castle Opera House, 6—The Academy of Art, 7—Trafostacja (TRAFO Center for Contemporary Art), 8—The Small Theatre, 9—The Pleciuga Puppet Theatre. Source: Google maps, 2021.

3.3. Research Methods

To facilitate the comparison between public perception of selected cultural facilities and their objective qualities, the study adopted an urbanscape approach. According to the definition of the European Landscape Convention, landscape is an area perceived by people, and its character is the result of the action and interaction of natural and human factors. Thus, as an expression of facts and phenomena, landscape is a valuable source of information, and its essence is human perception. This perception includes both recognition of the spatial configuration of the landscape and understanding of its content. The specificity of urbanscape is the interpenetration and interdependence of features that result from the spatial structure of the city, the ways it is used and the history that takes place there.

A simplified model has been proposed to assess the impact of studied cultural facilities in the urbanscape based on four main, easily identifiable features that form a wider catalogue of features that determine the identity of flagship cultural facilities. Each determinant describes a different identity-oriented layer of a facility in its urbanscape, i.e., form, symbolic meaning, function, and relation with the surrounding. Qualitative methods and surveys were used in the analyses.

3.3.1. Qualitative Methodology

By definition, the buildings of culture should play the role of flagship objects in the urban landscape. In order to verify this, such indicators were proposed for their evaluation as are most distinctive or dominant in the perception of a given layer of the urbanscape, which is important in the case of potentially flagship objects. The indicators relating to the form, function and symbolic of the buildings include respectively: monumentality, complexity, and coherence. The analysis of individual architectural objects in urbanscape terms also requires taking into account the object’s relationship with its surroundings as regards to hierarchy, scale, and order of structure. Buildings play different roles in the city structure, depending on their location, scale, composition of development, landforms, and configuration of spaces between buildings. This aspect is summarized by the exposure indicator.

Therefore, in relation to the semantic, spatial, location and functional characteristics of the completed projects, the following indicators were assumed as evaluation categories:

- coherence (semantics)

- monumentality (form)

- exposure (location)

- complexity (function)

Coherence is based on the semantic specificity and identity of a structure. As a relation between the sign and the content, it refers to the historical continuity in terms of the symbolic role and meaning of the examined facility and the nature of the place on which it was built and its authenticity. It focuses on compliance with the place’s tradition and links to cultural and spatial contexts. In order to determine the parameter of semantic coherence of developments, desk studies were carried out, examining how individual projects refer to, protect and exploit the historical heritage of the city. These studies consider the tradition and specificity of a place, the way it is embedded in the context, the symbolic meaning of the objects and the adaptation of the architectural language. A classification was proposed for the ways of using the identity aspect of a development while maintaining the relationship between the cultural institution and the cultural facility (building).

Monumentality is an indicator referring primarily to the spatial specificity of the structure. It stems from the strength of a structure’s spatial impact, magnificence, and uniqueness. It is linked to representativeness, originality, and iconicity of architecture. To determine the monumentality of cultural developments, perceptual visual studies were carried out to examine the shape, architectural features and the scale.

Exposure is a locational indicator of the building’s characteristics. It represents the strength and range of building’s visibility in the public area of the city. Indicates whether the structure is easy to notice and visibly dominant. The structure’s exposure is determined by the range and attractiveness of its external viewing links, including the possibility of observation from a distance. It results from the location in the city, the layout of the neighborhood and the size of the structure itself. In order to assess the exposure of cultural developments, the urban structure of the Śródmieście was analyzed, diagnosing the network of main public spaces and its nodes, and landscape studies were conducted in their area to diagnose and assess the sightseeing links with the surveyed projects.

Complexity determines the functional layer of the structure, which allows representing the structure’s useful attractiveness. It is defined by the number, type, and proportion of activities and events taking place there. In the analysis of the complexity of functions of individual objects, it was taken into account: what number of additional urban functions do the objects perform (apart from the dominant function); how many different city users (e.g., children, and adults) use the facilities annually (Table 1); and whether the facility is also used at different times on a daily, weekly, or annual basis. Such an analytical approach refers to a classic urban function analysis. In order to assess the functional complexity of the cultural developments examined, their programs and repertoire have been studied in terms of the number and diversity of the events and the social profile of their audience. Additionally, field studies conducted during events were used as a series of participatory observations.

The examined cultural developments were assessed in each of the above mentioned categories, assigning them one of the five grades: low, medium-low, medium-high, high, and very high. These categories, which are indicators of urbanscape identity, were rated equivalently on the same scale so that they could be summed up for individual structures and compared between the structures. The grades correspond to the number of points assigned, from 0 to 4.

3.3.2. Survey Method

A survey was used to assess the impact of new cultural and art projects on the sense of territorial identity of Szczecin’s residents. Through the residents’ perception and subjective opinions, three areas of the social impact of the analyzed developments were examined:

- the degree of recognition of cultural institutions in Szczecin, including the studied projects;

- the level of residents’ identification with the project examined;

- how residents assess the impact of a project on the surroundings.

Recognition of cultural and art structures has been studied with regard to spontaneous and assisted recognition. In the first type of survey, the participants were asked to list the institutions of culture and art in Szczecin that they knew by heart, and then in the second type of survey, they were given a list of sixteen supra-local institutions of culture and art and tick those that were known to them. However, the degree of the residents’ sense of acceptance for an identification with the projects underway was surveyed through a request in which the participants were to shortlist no more than 3 personally most important ones out of nine cultural projects. Likewise, by requesting the surveyed person to name the projects with the strongest impact on the surroundings, the strength of the impact of cultural projects on the surroundings according to residents was surveyed.

The survey was performed via the Internet, with 214 residents of Szczecin and its surroundings answering the questions. The survey covered adult residents only out of the total population of 336,396 people [48]. The survey was divided into four age groups: 18–25 years, 26–45 years, 46–65 years, and over 65 years old. The division is in line with the breakdown of population into pre-working, working, and post-working age groups. Additionally, the working age group has been divided into two sub-groups to make survey results more distinct. The timeframe for the surveys conducted was from July to September 2020.

The assumed margin of error at the level of 5% with 90% confidence level determines the sample size at the level of 270 respondents. During the assumed survey period of two months, the survey was managed to conduct on a sample of 214 respondents. The sample was created as a snowball among the respondents with access to the Internet. The study was therefore not fully representative, but its scale allows to recognize the importance and research usefulness of the study.

4. Results

4.1. The Urbanscpae Identity of Flagship Cultural Developments

4.1.1. Semantic Indicator—Coherence

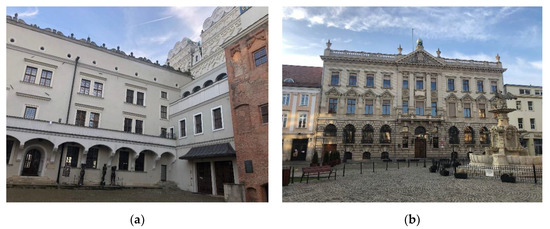

In terms of the conveyed semantic content (coherence of semantics), including links with the tradition, the analyzed developments can be divided into several types. The first group consists of cultural institutions located in adapted historic buildings, with their specific contrast and antinomic old and new functions. Cultural developments that gave new life to abandoned and deteriorating civil structures create an intriguing, though often quite an incoherent message. This is the case with the project of the Small Theatre being an adaptation of the former city gate, with no clear semantic references to the history and former role of the building (Figure 3a). On the other hand, the spatial solutions used in the Trafostacja Gallery (“TRAFO”) successfully accentuate the industrial character of the building, serving as a natural background for the exhibition of contemporary art, but this is most evident in the interior of the building (Figure 4a,b). In some cases, semantic continuity is perfectly maintained, integrating and highlighting those features of the historical structure that determine its specificity and essence in the contemporary transformation. A good example is the Museum of Technology and Transportation located in a former tram depot (Figure 3b). The original purpose of the building of the Museum of Technology and Transportation is easily recognizable and perfectly enhances the contemporary theme of the facility, thereby continuing the identity of the place.

Figure 3.

(a) Small Theatre, Szczecin, Poland; (b) The Museum of Technology and Transportation, Szczecin, Poland. Source: Authors.

Figure 4.

(a,b) Trafostacja (TRAFO Center for Contemporary Art), Szczecin, Poland. Source: (a) Andrzej Golc, https://trafo.art/ Accessed on 8 March 2021 (b) Authors.

Two structures form a separate group in terms of how the cultural heritage of the city is used: The Castle Opera House and the Academy of Art (Figure 5a,b). These developments also have been transformed from historic buildings, but in their case, we are dealing with different degrees of continuation or enhancement of their functions. The impressive, monumental edifices were adapted by revaluation to perform a representative function, taking advantage of the lounge tradition and the specificity of the place.

Figure 5.

(a) The Castle Opera House, Szczecin, Poland; (b) The Academy of Art., Szczecin, Poland Source: Authors.

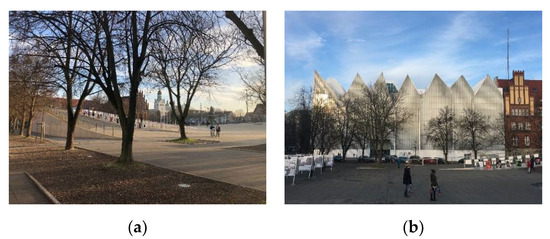

Another group of structures is semiotically distinctive by a direct reference to the history, tradition, and identity of a place where they were built. The choice of sites for the construction of the Upheavals Center of Dialogue Museum and the Szczecin Philharmonic Concert Hall was not accidental; it is strongly linked to the content that these buildings carry (Figure 6a,b). Their form was determined through international architectural competitions. The Philharmonic Hall was erected in the place of its predecessor (Konzerthaus), which had been demolished in the 1960s. New structure symbolically refers to the musical history of the city and continues the tradition of the function and rank of this place as the cultural lounge of Szczecin. The Upheavals Center for Dialogue serves as a museum of the city’s contemporary and tragic history. It was founded in the square, which was previously a quarter of tenement houses destroyed during the war. This was where the protesting residents were brutally pacified in December 1970. The form of the museum which is partially hidden underground is a compilation of two opposing urban forms of this place: the quarter and the square, while the symbolism of the building refers to historical events [7]. Both of these buildings are distinguished by the unique, historically justified and location-dedicated language of architecture, which perfectly reflects the content conveyed.

Figure 6.

(a) The Upheavals Dialogue Center Museum, Szczecin, Poland; (b) The Szczecin Philharmonic Concert Hall, Szczecin, Poland. Source: Authors.

The Maritime Science Center is also a new but long-awaited institution for years (Figure 7a). The symbolism of the structure is robust due to its form and the waterside location in the former port, referring to the specificity of the structure, but the message is not so authentic. The last group closes with the Pleciuga Puppet Theatre (Figure 7b), which is a building where an old institution with traditions was located in a somewhat random place, in no way reminiscent of the specificity of the building or its traditions, and its architecture is devoid of deeper symbolism. The building enjoys a strong tradition of the institution, but in its semantic message it clearly loses out on the lack of use of the identity aspect in the creation of the new building and in the choice of its location (Table 1).

Figure 7.

(a) The Marine Science Center, Szczecin, Poland; (b) The “Pleciuga” Puppet Theatre, Szczecin, Poland. Source: Authors.

4.1.2. Form Indicator—Monumentality

In terms of monumentality, taking into account the quality, representativeness, uniqueness of architectural solutions and the scale of form, the Szczecin Philharmonic Hall and the Upheavals Center for Dialogue are pieces of unique and the most iconic architecture. They were developed through international competitions and have been awarded numerous prizes. A unique, very monumental form has also the Renaissance castle, which accommodates the Castle Opera. However, the opera occupies only a part of the castle building and this institution does not have any spatial distinctiveness. These facts do lower the building’s expressiveness and monumentality rating. The Maritime Science Center is also highly monumental; although, its spatial quality loses a bit as a result of the strong marine theme. The adaptations of old civil structures for museums and galleries should also be considered architecturally successful. Both TRAFO Center for Art and the Museum for Technology and Transportation have a clear and strong spatial form. The Small Theatre is less monumental. The Baroque building of the former city gate is small in scale and has the spatial specificity typical of many such buildings, but it is also representative and stylish. In turn, the building of the Pleciuga Puppet Theatre, despite its larger scale, cannot be called monumental. The structure is devoid of extraordinary or representative features as it is trivial and its spatial form is not adapted to its role. The lack of artistic creativity is striking in this supra-local cultural facility (Table 2).

Table 2.

Assessment of the impact of flagship cultural objects in the landscape. Types of developments (construction project): NI- NS: new institution–new structure, NI-OS: new institution–old structure (adaptation), OI-NS: old institution–new structure, OI-OS: old institution–old structure (modernization/revaluation), source: Authors.

4.1.3. Location Indicator—Exposure

The structures being analyzed are very different in exposure levels. In this respect, the Maritime Science Center and the Philharmonic Concert Hall in Szczecin have a prominent position. These developments are large, centrally located and perfectly visible from the main public spaces, including the main entrance to the city. They all have foregrounds of exposure and are dominants in the city landscape. The Maritime Science Center is accentuated by the waterside location and the Szczecin Philharmonic Concert Hall by being located at the Solidarity Square. The Small Theatre is located in the central and nodal point of the city, on Victory Square. It is threaded like a bead on one of the main composition axes of the city. However, being small in scale, this structure does not dominate the space. Similarly, the Upheavals Center for Dialogue can be assessed in terms of exposure. The building itself is perfectly visible at the main entrance to the city center, but it does not dominate. Its dualistic structure resulting from the confrontation of two contradictory urban traditions: the square and the quarter, has been composed in such a way as to play the role of a vast viewing opening for the neighboring philharmonic building. The Academy of Art plays a less prominent role in the city’s urban composition. The edifice co-creates the baroque frontage of one of the most important squares of the Old Town. Despite having a very ennobling location in the representative part of the city’s public space, the visibility of the building is local and only frontal. The location of the Pleciuga Puppet Theatre is far from the very heart of the city, it also remains outside the main urban axes, which strongly influences the assessment of the building’s exposure, but the facility is to some extent highlighted by its composition in the open area surrounded by streets. The building of the TRAFO Center for Contemporary Art has an intimate but central location. Located in the Old Town, in a side street, it has no further viewing links. It is complicated to assess the Castle Opera because while the castle building is undoubtedly a dominant feature of the city landscape, the opera house itself is not distinguished or marked in the body of the castle. Being concealed in a part of the edifice’s interior, the opera house has little viewing accessibility and exposure. The Museum of Technology and Transportation has the lowest degree of exposure. Its location is peripheral in relation to other studied constructions. In addition, the building is significantly moved back in relation to the first line of the street development, which significantly reduces its visibility (Table 2).

4.1.4. Functional Indicator—Complexity

Despite the defined specificity of the cultural institution, the analyzed structures also have a varying degree of functional complexity. The most diverse and rich utility program is characteristic of the Museum of Technology and Transportation and the Szczecin Philharmonic Concert Hall. These buildings offer an opportunity for different age groups and go much further than their functional specificity. Apart from offering a wide range of concerts, recitals, radio plays and workshops devoted to classical, jazz, and popular music, the Philharmonic Hall holds festivals, conferences, occasional events, film presentations and art exhibitions. A popular café is also run in the building. Museum of Technology and Transportation also offers a similarly rich and complex exhibition, didactic, party and catering offer. The planned the Maritime Center of Science program is also extensive and multidimensional. In addition to their basic activities, TRAFO Center for Contemporary Art and Pleciuga Puppet Theatre do offer an attractive, varied educational program for children and are very popular as meeting places. Ranked behind them is the Upheavals Center for Dialogue, presenting the permanent and additional exhibitions and displays as well as events related to the subject matter of the institution. The program of the Castle Opera House and the Academy of Art is less diversified, although these institutions also try to expand their statutory profile with additional events. The Small Theatre has the narrowest scope of activity among the analyzed cultural institutions, which is certainly due to its compact size (Table 2).

4.1.5. Summary Assessment

In total, taking into account an impact of all desired for flagship cultural facility identity determinant, the Szczecin Philharmonic Concert Hall and the Maritime Science Center are ranked highest. The Philharmonic Concert Hall is an exceptional facility, as it has received the highest ratings in every dimension: location, spatial, symbolic and functional. The Upheavals Center of Dialogue receives a high rating. The Museum of Technology and Transportation, the Castle Opera House, and the Academy of Art have a medium-high position, with their characteristic feature being a significant disparity of ratings in individual categories. The fourth group of objects which have been rated low or very low in at least two categories consists TRAFO Center for Contemporary Art and the Small Theatre. Against the background of the whole group of analyzed cultural developments, the Pleciuga Puppet Theatre stands out clearly in terms of strength of form, symbolism and location. Only in terms of functional diversity does it meet well the criteria of a flagship cultural facility (Table 1).

4.2. Social Perception of Flagship Cultural Objects—Research Results

For survey research, the sample consisted of a total of 214 people, of whom 54% were women and 46% were men. Among the surveyed, 90% are residents of Szczecin and its immediate vicinity and 10% are residents from outside the agglomeration. Respondents are adults, divided into four age groups: 18–25 years, 26–45 years, 46–65 years, and over 65 years old. The most numerous in the sample is the 26–45 age group, comprising 46.2% of the respondents. The second-largest is the 45–65 age group, accounting for 27.6% of the sample, and 14.5% of the respondents represent the oldest age group, people over 65, and 11.7% of the respondents are from the youngest, 18–25 age group.

4.2.1. Recognition of Cultural Developments

The results of the survey on the recognition of individual cultural institutions in Szczecin were divided into four groups, assigning them very high, high, medium, low, or very low grades. A homogeneous method of grading results has been adopted for both categories of recognition: assisted and spontaneous. The ranges for the evaluation of the results were adopted in intervals, adjusting the division to the achieved values. The first assessment threshold was set at 10%, and the next ones every 20 pp. The boundary values dividing the individual grades are: 10, 30, 50, and 70%, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

How residents recognize cultural supra-local institutions in Szczecin. Types of developments (construction project): NI- NS: new institution–new structure, NI-OS: new institution–old structure (adaptation), OI-NS: old institution–new structure, OI-OS: old institution–old structure (modernization/revaluation), source: Authors.

In the recognition survey the total number of sixteen supra-local investments was analyzed in order to demonstrate the recognition of nine cultural developments selected for the case study against the background of all sixteen public cultural institutions of supra-local range in Szczecin (Table 3).

With respect to assisted recognition, the following objects qualify for a very high rating, exceeding 70%: Szczecin Philharmonic (95.4%), Pomeranian Dukes’ Castle (92.9%), Pleciuga () Puppet Theater (91.7%), Polish Theater (87.4%) and the Contemporary Theater (85%), the National Museum (88.3%), the Castle Opera (87.9%), the Pomeranian Library (84.1%), and the new institution of the Museum of Technology and Communication (82.2%). Facilities in the second group, which are mostly new institutions, enjoy a significantly lower level of recognition than those listed above, but still objectively high. They received a high rating. More than half of the respondents declare that they know: The Upheavals Center of Dialogue (65.9%), the Kana Theater (64.5%), the TRAFO Center for Contemporary Art (56.1%), and the Maritime Science Center (52.3%). The group of average grades included the Academy of Arts (45.3%) and the Krypta Theater (41.6%). The list is closed by the Small Theater (21.1%), which was classified as low in terms of assisted recognition. However, none of the objects fell into the category of a very low assessment in terms of assisted recognition.

In terms of spontaneous recognition, only one facility was assigned a very high rating exceeding 70%, the result of which significantly deviates from those of subsequent items: the Philharmonic Concert Hall (76.2%). The second group, with high ratings, consists of institutions which more than half of the respondents were able to name: the Polish Theatre (55.1%) and the Contemporary Theatre (50.5%). A medium rating was given to the following structures: the Castle Opera House (42.1%) and the National Museum (34.6%). Institutions from both of these groups are strongly rooted in the city’s tradition, functioning in the same locations for decades. The highest number of facilities were assigned to the group of the low rating of spontaneous recognition, including the following: The TRAFO Center for Contemporary Art (21.5%), the Pomeranian Dukes’ Castle (20.1%), the Kana Theatre (19.2%), the Museum of Technology and Transportation (16.4%), the Pleciuga Puppet Theatre (14.9%), and The Upheavals Center of Dialogue (11.7%). Cultural institutions, which were the least frequently named by pollsters, receiving results below 10%, are the Pomeranian Library (8.4%), the Academy of Art (8.4%), Marine Science Center (3.4%), the Small Theatre (2.5%), and Krypta Theatre (1.4%). The pollsters in this survey also mentioned other objects that were not included on the list in the assisted recognition survey as those that did not meet the criterion of supra-local cultural institutions. Among them, the largest number of votes was given to the “13 Muz” cultural center (13 Muses), which was mentioned by as many as 17.8% of the respondents, and the historical studio “Pionier” Cinema with a rating of 11.7%. The respondents named multiple times also the following: “Słowianin” Cultural Center (4.7%) and Summer Theatre concert stage (2.3%). The relatively high score of the 13 Muz Cultural Center and the Pionier Cinema indicates that the residents treat these facilities as important, supra-local cultural institutions (Table 3).

In summary, the results of the surveys showed that the cultural institutions in Szczecin are generally familiar to the residents, while at the same time the values in both categories of recognition: assisted and spontaneous differ significantly. Impressive results were achieved in the category of assisted recognition, and much lower when the respondents had to name the cultural and arts institutions they knew themselves. In terms of assisted recognition, the number of institutions declared to be familiar to more than 50% of the respondents includes as many as 13 items out of 16 respondents, while in the spontaneous recognition survey it includes only 3 items out of 16 respondents. The difference between the two types of recognition is significant for all institutions, with the average of about 50 percentage points. Moreover, for three of them, the Pleciuga Puppet Theatre, the Pomeranian Dukes’ Castle, and the Pomeranian Library, the difference is about 75 percentage points. The smallest difference of about 20 percentage points was noted for the Szczecin Philharmonic Hall and the Small Theatre. The results of surveys on spontaneous versus assisted recognition also show greater step differences between subsequent items, but overall they have a similar spread. Moreover, in the assisted survey, as opposed to the spontaneous survey, it can be observed that the degree of recognition of old cultural and artistic long-functioning institutions is higher than that of the new ones, established after 2008, although also the latter include structures with high (Museum of Technology and Transportation) and medium-high (The Upheavals Dialogue Center Museum, TRAFO, and the Maritime Center of Science).

Among all supra-local institutions of culture and art in Szczecin, the recognition of these nine facilities, which constitute new developments and focus of this research, is very different. It could be expected that the highest positions among them will be taken by three developments involving old, well-established institutions: The Szczecin Philharmonic Concert Hall, the Pleciuga Puppet Theatre, and the Castle Opera House, but this is the case only when the respondents select the objects they know from the list. The assisted recognition survey deals with the first of the analyzed developments, and the differences between them are several percent. However, when the respondents are asked to name the cultural and artistic institutions they know themselves, this is no longer so obvious. The Philharmonic Hall in Szczecin remains a clear leader, well-known to interviewees. The facility received a very high rating in both recognition categories, losing only 20 percentage points when named by a person by themselves. Opera House had significantly lower spontaneous recognition than assisted recognition, the difference being over 45 points. Despite this, the Opera House maintains a high position in the spontaneous recognition survey, taking fourth place among all institutions and falling within the range of medium-high ratings. A surprisingly low score in relation to the assisted survey was achieved by the Pleciuga Puppet Theatre. The decline is spectacular, of almost 80 percentage points, the highest of all sixteen institutions. From the very high recognition score in the assisted survey, it fell into a group of objects with a medium-low recognition score in the spontaneous survey. Fewer people mention the theatre than new institutions such as the TRAFO Center for Contemporary Art and the Museum of Technology and Transportation. The theatre was included in the group of a few old institutions that includes the Pomeranian Dukes’ Castle and the Pomeranian Library, which, winning very high positions when the interviewees mark in the list the facilities familiar to them, became unpopular when people had to name it them themselves. These structures, although well known to the inhabitants, are much less recognized or associated with cultural and artistic institutions. The development involving the construction of a new building for the Pleciuga Puppet Theatre did not clearly improve the identifiability of the structure in the survey of spontaneous recognition.

4.2.2. Social Ratings of the Importance of Cultural Developments

The results of the surveys on the inhabitants’ personal relevance of and their assessment of the environmental impact also fall into five types of ratings: very high, high, medium, low, and very low. A homogeneous way of rating was adopted for both surveys. The specificity of the issue examined by means of these two surveys determines the rather low median of the results, which influenced the adopted evaluation ranges. The level above 40% of indications was considered as very high evaluation, the next thresholds were assumed in intervals of 10 points. High scores were given to sites with more than 30% of indications, medium scores to sites with more than 20%, low scores to sites with more than 10%, and very low scores to sites with less than 10% of indications.

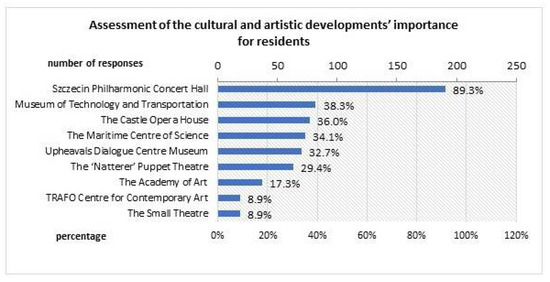

The survey on the level of identification of inhabitants with cultural urban development clearly indicates that there is a leader. The Philharmonic Hall in Szczecin has been ranked as a prominent item, and almost 90% of the population have considered this development to be personally important. This result is not very much dependent on the age of the respondents and the facility received the most votes in the 46–65 age group (93.2%), and the youngest of the respondents (80%). Definitely lower and relatively equal positions were taken by the following developments: Museum of Technology and Transportation (38.3%), the Castle Opera House (36.0%), Maritime Science Center (34.1%), and Upheavals Center for Dialogue (32.7%). They have been assigned a high-rating category. It is worth noting that the rating of the Maritime Science Center varies considerably depending on the age of interviewees, and has been high in two younger groups, with an average of 47.5% of the votes in the 26–45 age group. Only the Pleciuga Puppet Theatre, which was voted for by 29.4% of the respondents, was classified as the medium rating. The completion of the Academy of Art, whose rating of 17.3% was assigned to low rating, turns out to be of lesser importance for the residents. At the same time, it is worth noting that the establishment of the Academy of Art is clearly of higher importance for the youngest group of respondents because as many as 32.0% of them considered this development to be personally important. The TRAFO Center for Contemporary Art (8.9%) and the Small Theatre (8.9%) are considered very low relevant by the population (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Assessment of the cultural developments’ importance for residents. Results of a survey on a sample of 214 people, source: Authors.

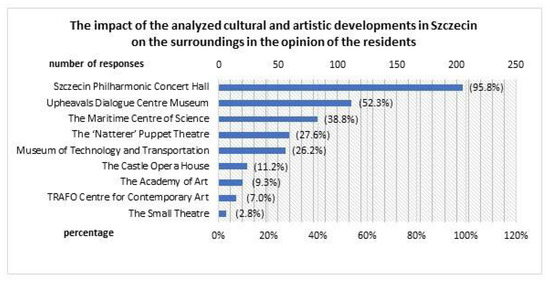

The development’s environmental impact assessment is fairly consistent among the interviewees. Therefore, the results of individual developments differ significantly. Again, the highest, distinctive position among other developments was won by the Szczecin Philharmonic Concert Hall. Its urban importance was recognized by as many as 95.8% of respondents. The second development important for the surroundings was the Upheavals Center for Dialogue adjacent to the Philharmonic Concert Hall, which received 52.3% of votes, with 66.7% of votes in the 26–46 age group. Both these developments were classified to very high rating. One facility, the Marine Science Center was classified to high rating. 38.8% of all respondents, and 46.5% of those in the 26–46 age group, decided that this development strongly affects the surroundings. Slightly more than one in four participants indicated that the construction of the Pleciuga Puppet Theatre (27.6%) and the Museum of Technology and Transportation (26.2%) had such an impact, and these results seem to be medium. In the opinion of the residents, The Castle Opera House (11.2%), has a low impact on the surroundings; a very low impact was found for the following projects: Academy of Art (9.3%), the TRAFO Center for Contemporary Art (7.0%), and Small Theatre, for which only 2.8% of respondents voted (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

The impact of the analyzed cultural developments in Szczecin on the surroundings in the opinion of the residents. Results of the survey on a sample of 214 people, source: Authors.

By comparing the two surveys, we can see a general rule that for most of the projects, their significance was assessed by the respondents to be lower for the surroundings than for themselves. Only three structures were an exception: The Upheavals Center for Dialogue, the Philharmonic Concert Hall, and the Maritime Science Center. The greatest differences between the assessment of the project’s impact on the surroundings and the assessment of their personal significance were identified for the Castle Opera House (by 25 percentage points) and the Museum of Technology and Transportation (by about 12 percentage points). These objects are rated much lower for the strength of their impact on the surroundings than for their impact on the respondents. In the case of the Upheavals Center for Dialogue, the opposite is true. What draws attention is a very high assessment of the impact on the surroundings of this project, not only against the background of the assessment of personal involvement in relation to the facility (increase by 20 percentage points) but also the results of its recognition. In both surveys, the ratings are lowest for the same three projects: The Academy of Art, the TRAFO Center for Art, and the Small Theatre (Table 4).

Table 4.

Residents’ identification with cultural developments and their impact on the surroundings in the residents’ opinion—comparison, assessment, and classification. Types of developments (construction project): NI-NS: new institution–new structure, NI-OS: new institution–old structure (adaptation), OI-NS: old institution–new structure, OI-OS: old institution–old structure (modernization/revaluation), source: Authors.

4.3. Interpretation of Obtained Results

Due to the specificity of the subject and its range, the number of developments covered by the study was relatively small, which certainly made it difficult to assess the impact of the determinants of the specificity of the analyzed cultural developments on their public perception, and did not give a full picture of possible links. In addition, this impact is being modified by several additional factors, such as the operating time of the cultural developments, because although a common time frame has been adopted, part of the developments includes old institutions with a long and well-established operational tradition. Despite this, when comparing the results of surveys on the recognition and social perception of the cultural developments completed in Szczecin with the location, spatial, symbolic, and functional specificity of these facilities, some relationships can be found.

The results of the survey indicate that a development embedded in the city’s tradition and semiotically linked with a place and structure’s specific features not only preserves the cultural heritage of the city, but also makes the inhabitants feel the acceptance for an association with the developments completed. Developments which have the highest semantic coherence thanks to being completed with careful and thorough exploitation of local cultural heritage also enjoy the highest acceptance and identification by residents. For the Museum of Technology and Transportation, the Castle Opera House, the Maritime Science Center, and Upheavals Center for Dialogue, the coherence class is very high or high, and for all the five objects, this corresponds to personal significance being assessed by residents as very high or high. On the other hand, the developments with the highest degree of exposure are assessed by the residents as those with the greatest impact on the surroundings. These are Philharmonic Concert Hall in Szczecin, the Upheavals Center for Dialogue and the Maritime Science Center. An exception is the Small Theatre, whose impact on the surroundings was not recognized by the surveyed, despite the facility’s high exposure. It seems that the perception of this facility by the evaluators may be affected by its very low recognition. In addition, in both social categories, the ratings are lowest for the same three developments: The Academy of Art, the TRAFO Center for Contemporary Art and the Small Theatre. They also received a low total rating for the determinants of the strength of the facility’s specificity in particular layers. An exception in this comparison is still the Pleciuga Puppet Theatre, which was given the lowest total score for the strength of the facility’s specificity, but it takes middle positions in social ratings. Again, the differences in results may be explained by the recognition, which in the case of this facility is very high. Such a level of the local community’s sense of identification with the completed developments—as the perception of their urban significance—largely coincides with, or slightly differs from, the assessment of the strength of the developments’ specificity, while it coincides to a much lesser extent with the level of familiarity with these developments.

Based on the results obtained, it can be concluded that the strength of identity of the flagship cultural developments affects their social evaluation, while the strong symbolic and functional layer of the developments is more reflected in the sense of identification with them, and the formal and locational layer in the assessment of the impact on the surroundings. The degree of familiarity and the operation time of the developments are also important. This parameter is important as a corrective factor where there is a significant disparity in the level of familiarity and strength of urbanscape identity indicators.

5. Discussion

To determine the importance of, and affiliation with, new cultural facilities, findings of the public perception survey have been juxtaposed with the impact of cultural facilities on their urbanscape. This highlights only some factors that determine the re-urbanization potential of flagship cultural facilities. It is also only a small section of a much broader field of re-urbanization. It includes economic, social, and spatial aspects that are decisive regarding directions, forms, and rate of urbanization. The hypothesis set at the beginning of the paper that the culture-led regeneration is representative for the impact of re-urbanization on dilapidated city centers can hardly be proven by the study based on new cultural investment projects in Szczecin. Although we can discuss some kind of a scientific rationale, the hypothesis will have to remain in the sphere of authors’ theoretical consideration. Research into re-urbanization, its evolution, and the development and promotion of the culture-led regeneration have certain features in common. Since it refers to the rural-urban relation, the broad interdisciplinary concept of re-urbanization may support the development of the culture-led regeneration towards a more strategic and holistic approach coupled with a contemporary concentration on the endogenic social and cultural potential of a city.

Contemporary urban strategies based on culture-led development of city centers should be considered in a broader context of building a city development model. Such a re-urbanization model should focus on a long-term stability and enhanced importance of city centers, including intensive development of a residential function. Although commonly used, the term culture-led regeneration is imprecise. Regeneration as such applies to dilapidated, social deprivation areas, areas which are the most crisis ridden and usually covered by remedial programs. Flagship culture facilities are frequently built in a city center beyond revitalized areas. This has also proven to be true in Szczecin.

The results of the conducted surveys are part of the contemporary research on the integration model of the culture-led regeneration strategy, aimed at using the endogenous potentials of cities, including social coherence and cultural identity. Miles and Paddison [6] point out that a determinant factor in the success of culture-led regeneration is whether cultural developments involve a residents’ sense of belonging to a place. Similarly, Bailey et al. [49] refers to the role of social identity and the distinctiveness of a place, accepting that the cultural regeneration of an area lies in revitalizing existing sources of local identity and not in introducing new ones. The cultural developments being completed should utilize the existing conditions in such a way as to confirm the relationship between residents and place as well as space [49]. The essence of the activities, within the framework of this approach to cultural regeneration, is to integrate the local specificity and utilize the endogenous potential of the city, where the identity of a place, the importance of the exceptional cultural resources of a place, the search for its uniqueness, and the strength of the potential of the community, are all considered to play a special role [6,39,49,50]. Moreover, Polish researchers confirm the validity of this perspective. Flagship cultural developments can catalyze the renewal and the revival of a city, and their impact is linked to the utilization of the city’s cultural heritage [7]. What is more, the preservation of the city’s cultural heritage and the regeneration of degraded areas is an objective accepted and expected by local community in Poland, namely, for a cultural infrastructure development project to be supported by European Union funds [51]. This relation is also confirmed by the results of the present research. The highest level of acceptance and social identification was obtained in Szczecin by those cultural developments that were characterized by the highest degree of semantic coherence, where the identity of the place was exploited and historical continuity was preserved.

Since the identity of Szczecin has lost its continuity, today it needs a cultural interface. Cultural facilities developed within historical urban areas are an excellent example of the urban transformation and city’s historical continuity that do not antagonize consecutive periods in the development of the city. Since the study has focused on new cultural facilities developed in Szczecin, it highlights the opportunity of using the local cultural potential depending on the investment model. Each of the four models applied in Szczecin: new institution–old facility, new institution–new facility, old institution–new facility, old institution–old facility, refers differently to the identity of a development, covering the issues of the tradition and history of a place, tradition, and symbolism of the institution and the spatial means used. The relationship between the above features entails the possibility a whole range of valuable solutions, but also specific risks.

A natural consequence of the adaptation of historic buildings is to preserve, and often save, a facility being an element of the historical heritage of a city. Moreover, a cultural institution itself has a chance to acquire a unique facility which is semiotically coherent with the new activity, function, and character. Among the developments examined, a particularly successful example of using the endogenic potential of a place—in the model with a new institution and an old facility—is the adaptation of the former tram depot to the Museum of Technology and Transportation. Continuation of identity appears to be the main distinctive feature of this development. However, not all developments under this model were able to achieve such a high level of coherence of the relationship between historical substance and new function. The strongest risk is to ignore the role of history and the specificity of historical building in the construction of a new symbolism of a cultural and artistic institution located there, which often has a contrasting function and prestige.

For another development model, “an old institution–an old facility”, an example of which may be the modernization or expansion of institutions functioning in a historical building, the condition for the continuity of identity seems to be naturally met. However, the relatively small impact of a development on its identity, which characterizes this development model, may turn out to be a disadvantage. The identity of the Castle Opera House has been overshadowed for years, as the facility does not have a separate seat, occupying part of the interiors of the Castle of the Pomeranian Dukes.

In the model “an old institution–a new facility”, the two developments completed in Szczecin have applied completely different approaches to the use of tradition and local identity, making their assessments extremely different. The development of the new seat for the Szczecin Philharmonic Concert Hall is characterized by the use of the strong identity of the place and its continued specificity and prestige, which, together with the use of clear and unique spatial means, has strengthened the identity of the institution itself. The Pleciuga Puppet Theatre’s strong identity has been compromised as its new building is located in a place with no symbolic link to culture, far from the city’s main public zone and has low expressiveness and spatial quality.

Finally, the development model with “new facility and new institution” is, by definition, at risk of underutilization of the local cultural potential. However, this is not necessarily always the case as the example of both Szczecin’s developments completed under this model shows. The Upheavals Center for Dialogue is marked by a great respect for the existing historical and spatial context, while the Maritime Science Center directly evokes the specificity and function of the facility by using its waterside location and maritime form. Development model is classified through the social assessment of the impact on the surroundings—developments that construct new buildings are generally rated higher than those which revitalize or adapt historical buildings; however, when assessing their personal significance for the respondents, this division is no longer so clear.

As the qualitative studies indicate, within each development model there is a possibility of fully utilizing the values of tradition and local identity and obtaining a strong identity for a flagship cultural development which translates into a potential for re-urbanization. At the same time, the application of none of the development models guarantees a strong and coherent identity for the development. In combination with specific investment models, identified risks related to the use of endogenic cultural values are universal and can be applied to develop framework project recommendations integrated into culture-led strategies.

6. Conclusions