Landscape Sensitizing through Expansive Learning in Architectural Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Landscape Sensitizing through Expansive Learning and SES

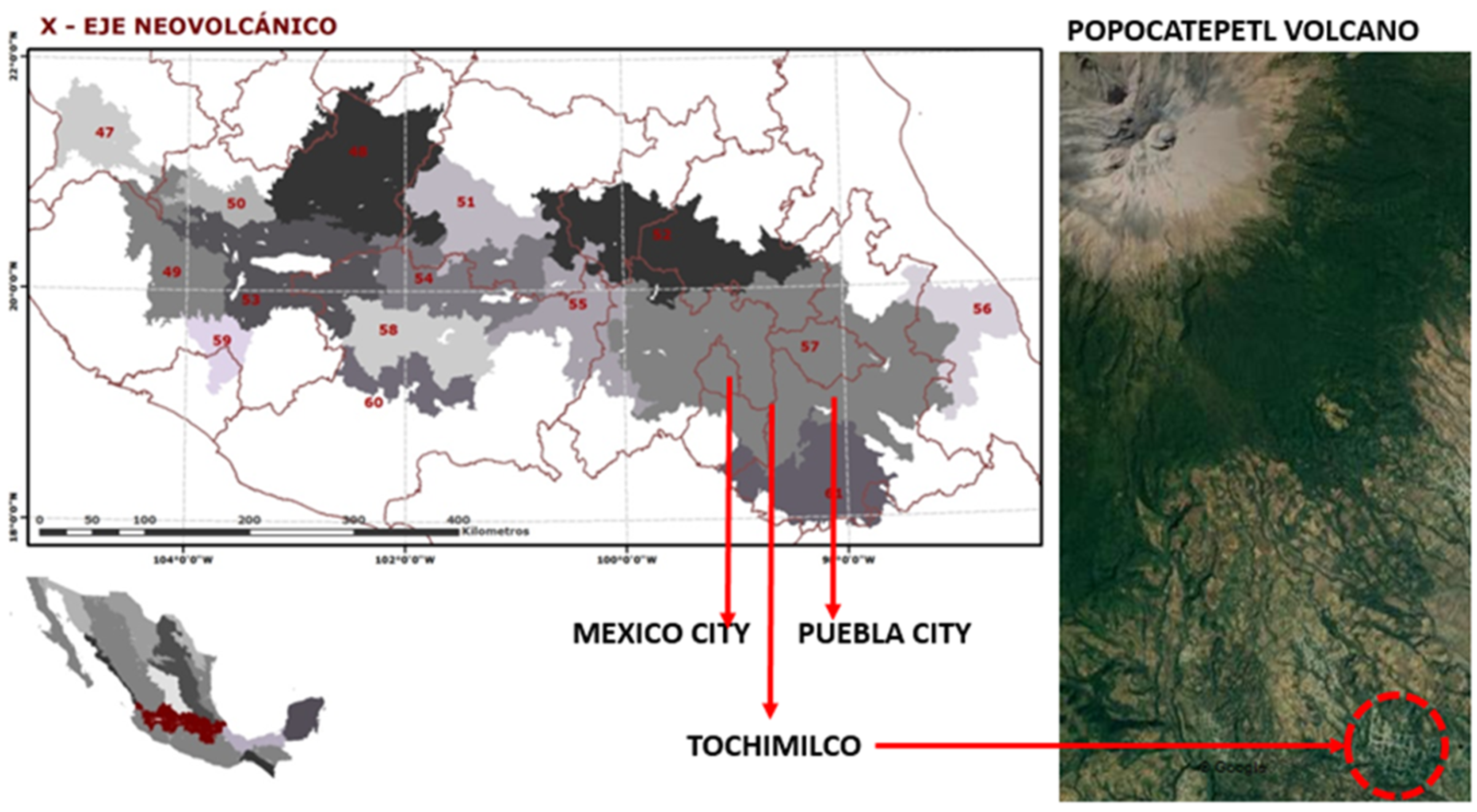

2.1. Problem Statement: Vulnerability of Multidimensional Landscapes in Tochimilco

2.2. Contextualization: Socio-Ecological Systems of Vulnerable Landscapes for Architectural Education

3. Methods and Case Study

3.1. The Case Study (Adopted Community)

- (a)

- Lack of environmental protection for its unique flora and fauna;

- (b)

- Socioeconomic & cultural changes due to local migration to USA and big Mexican cities,

- (c)

- Lack of accountability from local and State authorities to stop illegal loggers;

- (d)

- Abandonment of agricultural activities for urban work; and

- (e)

- Pollution of water sources and productive rural soil.

3.2. Socio Ecological System of Landscape in Tochimilco

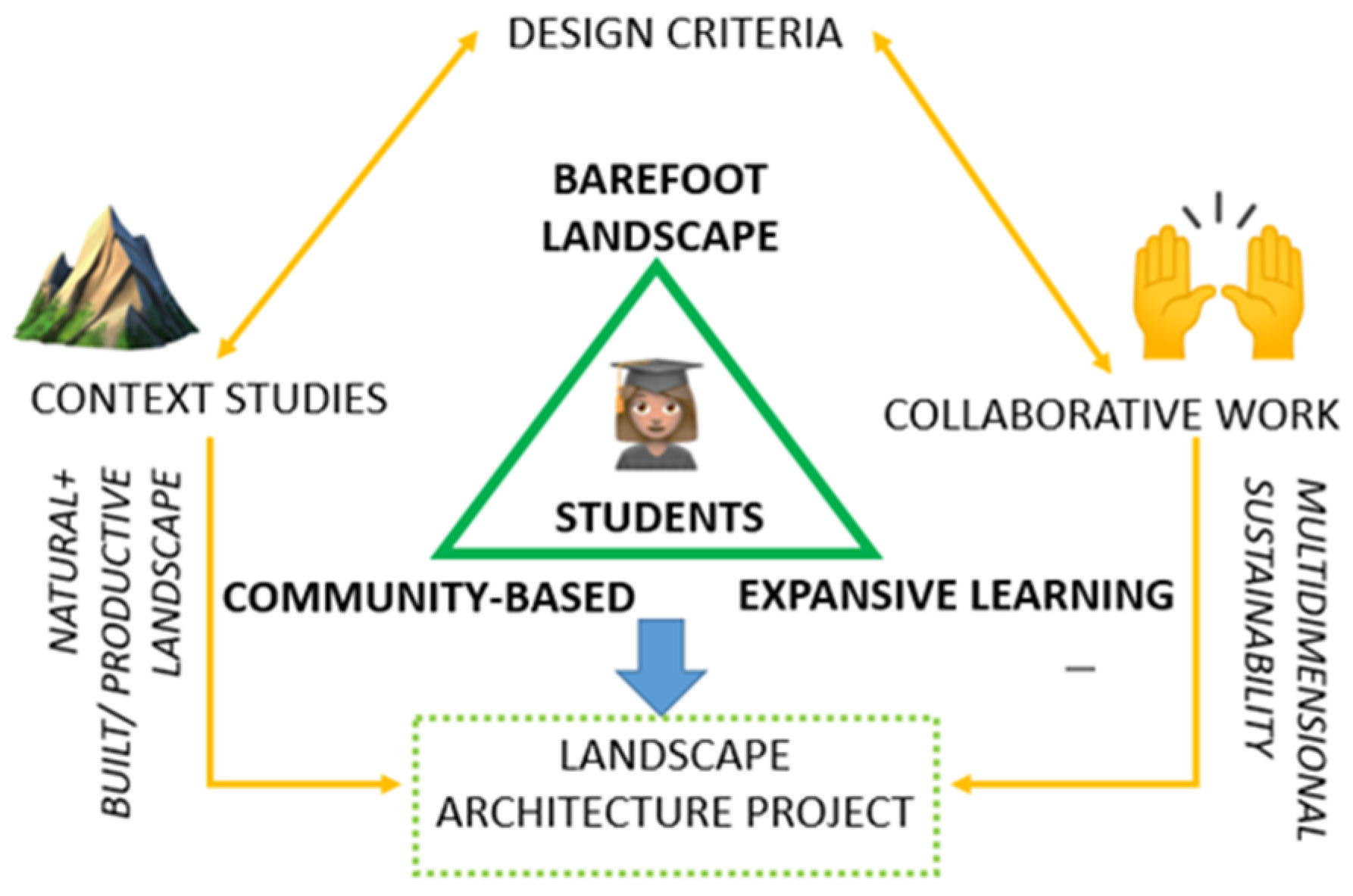

3.3. Barefoot Approach

3.3.1. STAGE 1—Collaborative Approach (Research)

3.3.2. STAGE 2—New Design Criteria (Analysis)

3.3.3. STAGE 3—Collaborative Workshop (Project Development)

3.4. Observations Regarding “Barefoot” Implementation Strategies in Tochimilco

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. First Statement: Architectural Education in Mexico Should Promote Environmental and Landscape Awareness among the Students in Order to Promote Multidimensional Sustainability, Especially When Working in Landscapes with Tangible or Intangible Natural, Cultural, or Historical Values

4.2. Second Statement: In the Case of Mexico, Expansive Learning Model and Co-Configuration Strategies Involving Local Rural Communites as “Partner of Place” Opens up a Way to More Sensitized Planning and Design Solutions Regarding Multidimensional Environmental and Landscape Values

4.3. Third Statement: “New Localism” and “Partners of Place” Framework Applied through Expansive Learning Inspired by Critical Realism (Cr) in Architectural Education, Promotes Critical Attitude of Top-Down Public Policy Informed by Economic and Real Estate Interests Triggering the Destruction of Valuable Natural, Cultural, or Historical Landscapes in Mexican Rural Communities and Their Landscapes

- (1)

- Considering the vast nature–culture and human–nature values of Mexican landscapes, the architectural education in Mexico should sensitize students to be able to read and understand them in terms of a sustainable relationship between culture, traditions, and sustainable development. Indeed, certainly also the landscape architecture programs with this same focus should be more widely offered by public and private universities.

- (2)

- For the future landscape planning practices, it is important to consider training in the recognition of the bio-cultural essence of place, and of landscape narratives and vulnerabilities as part of the contents of architectural course plans and regenerative projects.

- (3)

- The adoption of methods such as expansive learning are favorable for connecting students, educational institutions, researchers, and local communities to carry out “barefoot” projects as key strategies to trigger professional awareness. Introduction of architectural students to the concept of landscape in Mexican rural areas should be based on an integral view including aspects from the bio-cultural landscape factors and ecological variants to urban image and semiotics to promote the idea of the need of holistic projects that harmoniously connect the landscape and conservation of biodiversity to the local culture and traditional knowledge about the use of natural resources reinforced by the recovery of memories and experiences about the harmonious coexistence with the nature. This opens up a possibility for a more sustainable development for rural communities of Mexico such as Tochimilco.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Halttunen, K. Self, Subject, and the ‘Barefoot Historian. J. Am. Hist. 2002, 89, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mang, P.; Haggard, B. Regenerative Development: A Framework for Evolving Sustainability; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kurjenoja, A.K.; Schumacher, M.; Meza, E.G. Challenges of architectural education in Mexico. In Critical Global Semiotics: Understanding Sustainable Transformational Citizenship; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; p. 109. [Google Scholar]

- Durán-Díaz, P.; Armenta-Ramírez, A.; Kurjenoja, A.K.; Schumacher, M. Community Development through the Empowerment of Indigenous Women in Cuetzalan Del Progreso, Mexico. Land 2020, 9, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeström, Y. Learning by Expanding: An Activity-Theoretical Approach to Developmental Research, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Engeström, Y. Expansive Learning at Work: Toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. J. Educ. Work 2001, 14, 133–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeström, Y. Enriching the Theory of Expansive Learning: Lessons From Journeys Toward Coconfiguration. Mind Cult. Act. 2007, 14, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeström, Y. Expansive learning: Toward an activity-theoretical reconceptualization. In Contemporary Theories of Learing: Learning Theorist, in Their Own Words; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2009; pp. 53–73. [Google Scholar]

- Sipos, Y.; Battisti, B.; Grimm, K. Achieving transformative sustainability learning: Engaging head, hands and heart. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2008, 9, 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P. Axioms for reading the landscape. Interpret. Ordinary Landsc. 1979, 23, 167–187. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas Garrido, R. La Arquitectura del Paisaje en México y el Mundo. Construyendo Querétaro. Available online: https://ulc-constructions.com/la-arquitectura-de-paisaje-en-mexico-y-el-mundo/ (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Uriarte, D.M. La arquitectura de paisaje en México y en el mundo. Bitácora Arquit. 2015, 31, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schumacher, M. Peri-Urban Development in Cholula, Mexico; Technische Universität München: München, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow, R.H. Tres pueblos en el valle de Atlixco. Tlalocan 2016, 4, 274–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conanp. Programa el Hombre y la Biosfera (MAB). Reserva de la Biosfera los Volcanes. 2004. Available online: http://www.conanp.gob.mx/conanp/dominios/iztapopo/documentos/MaB/RB_LOSVOLCANES.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2020).

- Rangel Oaxaca, M. Historia de Tochimilco. Municipio de Tochimilco, Puebla. 2011. Available online: https://es.slideshare.net/thewolff?utm_campaign=profiletracking&utm_medium=sssite&utm_source=ssslideview (accessed on 2 July 2020).

- Paredes Martínez, C.S. La región de Atlixco, Huaquechula y Tochimilco: La Sociedad y su Agricultura en el Siglo XVI; Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz Máximo, T.; Ocampo Fletes, I.; Parra Inzunza, F.; Cervantes Vargas, J.; Argumedo Macías, A.; Cruz Ramírez, S. Proceso de producción y mecanismos de comercialización de chía (Salvia hispánica L.) por familias campesinas de los municipios de Atzitzihuacán y Tochimilco, Puebla, México. Nov. Sci. 2017, 9, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cruz López, V.; Ocampo Fletes, I.; Juárez Sánchez, J.P.; Argumedo Macías, A.; Castañeda Hidalgo, E. Modo de apropiación de la naturaleza en las unidades de producción campesinas de amaranto y maíz en Tochimilco, Puebla, México. Nov. Sci. 2018, 10, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SEMARNAT. Sistema Nacional de Información Ambiental y de Recursos Naturales Informe del Medio Ambiente; SEMARNAT: Mexico City, Mexico, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- WWF. WWF’s Living Forest Report; WWF: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Heil, G.W.; Bobbink, R.; Boix, N.T. Ecology and Man in Mexico’s Central Volcanoes Area; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Bustos, L.A. Transformación del Paisaje en la Zona Centro de la Región Izta-Popo [1980–2013]; Universidad Veracruzana: Xalapa, Mexico, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Challenger, A. Utilización y Conservación de los Ecosistemas Terrestres de México: Pasado Presente y Futuro; no. 581.5; UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Galicia, L.; Zarco-Arista, A.E. Multiple ecosystem services, possible trade-offs and synergies in a temperate forest ecosystem in Mexico: A review. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 2014, 10, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann-Matthies, P.; Bönigk, I.; Benkowitz, D. Can’t See the Wood for the Litter: Evaluation of Litter Behavior Modification in a Forest. Appl. Environ. Educ. Commun. 2012, 11, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverría, C.; Newton, A.C.; Nahuelhual, L.; Coomes, D.A.; Rey-Benayas, J.M. How landscapes change: Integration of spatial patterns and human processes in temperate landscapes of southern Chile. Appl. Geogr. 2012, 32, 822–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drever, C.R.; Peterson, G.; Emessier, C.; Bergeron, Y.; Flannigan, M. Can forest management based on natural disturbances maintain ecological resilience? Can. J. For. Res. 2006, 36, 2285–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrusquia-Villafranca, I. Geology of Mexico: A synopsis. Biological diversity of Mexico: Origins and distribution. In Biological Diversity of Mexico: Origins and Distribution; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 3–107. [Google Scholar]

- CONANP. Programa de manejo Parque Nacional Iztaccíhuatl Popocatépetl; CONAIP: Mexico City, Mexico, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rzedowski, J. Vegetación de México. 1ra. Edición Digital; CONABIO: Mexico City, Mexico, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- INEGI. Prontuario de Información Geográfica Municipal de los Estados Unidos MexicanosTochimilco, Puebla; INEGI: Mexico City, Mexico, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Linda, S.; Kolomyeytsev, A. Semiotics of the City’s Pedestrian Space. Sr. Mieszk 2014, 13, 125–129. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, U. Function and Sign: The semiotics of architecture. In Rethinking Architecture: A Reader in Cultural Theory; Leach, N., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1997; pp. 182–201. [Google Scholar]

- Krampen, M. Semiotics in architecture and industrial/product design. Des. Issues 1989, 5, 124–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zukin, S. The Cultures of Cities; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gottdiener, M. The Social Production of Urban Space, 2nd ed.; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- González Jácome, A. Cultura y Agricultura: Transformaciones en el agro Mexicano; Universidad Iberoamericana: Mexico City, Mexico, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, B.; Grabasch, G.; McIntosh, J. Fostering Landscape Identity Through Participatory Design With Indigenous Cultures of Australia and Aotearoa/New Zealand. Space Cult. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Cities for People; Island Press: Washibgton, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, J. Urban Acupuncture; Island Press: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, B.; Nowak, J. The New Localism: How Cities Can Thrive in the Age of Populism; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, N.; Marcuse, P.; Mayer, M. Cities for People, not for Profit: Critical Urban Theory and the Right to the City; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Arellano, S.G.; Corona, A.L. Conceptualización y medición de lo rural. Una propuesta para clasificar el espacio rural en México. In La Situación Demográfica México; CONAPO: Mexico City, Mexico, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Baldenhofer, D. An Emergency Response Strategy Based on Good Governance Principles. The Case of Tochimilco, Mexico; Technische Universität München: München, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Tochimilco’s Landscape Interpretation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Landscape Element | Landscape Type | Denotative Sign | Connotative Sign |

| Forest | Natural | Wood | Provider of complementary economic, health and food resources; collateral force that has to be understood to maintain a balanced co-existence between the human and the non-human environment. |

| Volcano | Natural | Mountain | Ancient divinity; danger; provider of wealth and health as the origin of water resources. |

| Topography | Natural | Hills, valleys, slopes and gorges | Conductors and concentrators of water as providers of health and prosperity. |

| Wells, Streams and Rivers | Natural | Water reservoirs | Provider of power and prosperity through their connection to the apantle (acequia) system; Tlaloc and Jesus Christ as local divine forces related to water. |

| White Willow (Salix bonplandiana) | Natural Wetlands | Iztachuexotl tree | Sacred city of Cholula, union between the moon and water (represented in the local 17th century coat of arms). |

| Forest Under-Growth | Natural | Plants | Health and healing; emergency source for complementary food. |

| Forest Under-Growth | Natural | Ocopetlal, ferns | Memory of the pre-columbine ceremonial use (represented in the local 17th century coat of arms). |

| Forest Under-Growth | Natural | Fungi | Emergency source for complementary food |

| Apantle (Acequia) | Built and Productive | Irrigation and distribution water for urban and agricultural uses | Memory of the past; right for the use of water; power and social hierarchy. |

| Avocado Orchard | Productive | Unproductive and abandoned lands | Symbol and memory of the local agricultural tradition; local icon. |

| Arable Land | Productive | Rural landscape | Soil as the source of fertility and continuity. Harmonious co-existence. |

| Chia | Productive | Traditional agricultural production: plants and methods | Cultural memory, co-existence with the nature, augmented family income achieved due to the type of plant cultivated. |

| Amaranth | Productive | Traditional agricultural production: plants and methods | Cultural memory, co-existence with the nature, augmented family income achieved due to the type of plant cultivated. |

| Corn, Beans and Squash | Productive | Traditional agricultural production: plants and methods | Cultural memory of the occupation of the pre-columbine method of “three sisters”, auto-consumption. |

| Socio-Natural Relationality | ||

|---|---|---|

| Experiential | Human-Non-Human | |

| Natural landscape | Maintenance of nature–human knowledge of wellbeing and health as the basis for human practices. | Understanding of environmental conditions and conditioners of life: climate, geomorphological conditions, water and soil. |

| Artificial landscape | Maintenance of traditional symbolism as a non-textual discourse and narrative of place, | Understanding of the functional juxtaposition of environmental and human elements forming a tissue of a comprehensive co-existence. |

| Productive landscape | Maintenance of inherited and ancestral systems of cultivation due to their capacity to conserve their continuity. | Understanding of the environmental importance of flexible and creative methods of appropriation of nature, adaptation of productive strategies to the environment and of the permanence of the high adaptability of their means and methods to the local natural conditions. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kurjenoja, A.K.; Schumacher, M.; Carrera-Kurjenoja, J. Landscape Sensitizing through Expansive Learning in Architectural Education. Land 2021, 10, 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10020151

Kurjenoja AK, Schumacher M, Carrera-Kurjenoja J. Landscape Sensitizing through Expansive Learning in Architectural Education. Land. 2021; 10(2):151. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10020151

Chicago/Turabian StyleKurjenoja, Anne Kristiina, Melissa Schumacher, and Janina Carrera-Kurjenoja. 2021. "Landscape Sensitizing through Expansive Learning in Architectural Education" Land 10, no. 2: 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10020151

APA StyleKurjenoja, A. K., Schumacher, M., & Carrera-Kurjenoja, J. (2021). Landscape Sensitizing through Expansive Learning in Architectural Education. Land, 10(2), 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10020151