Abstract

The International Joint Commission (IJC) has been involved in a 14-year effort to formulate a new water regulation plan for the Lake Ontario St. Lawrence River (“LOSLR”) area that balances the interests of a diverse group of stakeholders including shipping and navigation, hydropower, environment, recreational boating, municipal and domestic water supply, First Nations, and shoreline property owners. It has embraced the principles of collaborative and participatory management and, applying a Shared Visioning Planning (SVP) approach, has worked closely with stakeholders throughout all stages of this process; however, conflicts between competing stakeholders have delayed and complicated this effort. The overarching aim of this paper is to consider the extent to which the SVP approach employed by the IJC was effective in managing conflict in the LOSLR context. Audio recordings and transcriptions of public and technical hearings held by the IJC in 2013 have been systematically analysed using stakeholder mapping and content analysis methods, to gain insight into the stakeholder universe interacting with the IJC on Plan 2014. The principal conclusions of this paper are that (a) the Shared Vision Planning approach employed by the IJC had some significant successes in terms of conflict management—particularly notable is the success that has been achieved with regards to integration of First Nation concerns; (b) there is a distinct group of shoreline property owners, based in New York State, who remain opposed to Plan 2014—the IJC’s public outreach and participation efforts have not been successful in reconciling their position with that of other stakeholders due to the fact that this stakeholder group perceive that they can only lose out from any regulation change and are therefore unlikely to be motivated to engage productively in any planning dialogue; and (c) a solution would require that the problem be reframed so that this stakeholder can see that they do in fact have something to gain from a successful resolution, which may necessitate bringing the prospect of compensation to the table.

1. Conflict in Participatory Approaches

Participatory approaches to water resources planning are increasingly promoted as best practice [1,2]. For the purposes of this paper participation is defined broadly, following Carr [1], as involvement of the public, institutional decision makers, individuals, or representatives of groups with an interest in or ability to influence how a river is managed, in river management decision making processes. Participation can take many guises; the classic framework used to characterize participation is Arnstein’s [3] ladder, which classifies participation processes based on the degree of power transferred from the process implementer to the participants. At one extreme, participation processes involve little transfer of decision making power to participants; these processes aim only to inform participants about, or perhaps even manipulate them into accepting, decisions that have already been taken. At the other extreme, participants are given real decision-making power, and are actively involved in the decision-making processes. In between these two extremes are participation processes in which participants are consulted on decisions but are not given final decision-making power.

Despite widespread acceptance of the concept, there has been some debate over the benefits participation brings and how it should be implemented in complex social-ecological settings [4]. To address the question of why participation is desirable, Carr [1] explored the mechanisms through which participation impacts river basin management. She concluded that participation can lead to better quality decisions being taken and, if conducted correctly, can increase the legitimacy of decisions, facilitating their implementation. She argued that participation both mobilizes and develops human and social capital, and provides space for deliberation and consensus building. Webler and Tuler [5] surveyed the opinions of watershed planners and activists from across Massachusetts and identified four prominent views of what a ‘good’ participation process should be. For some participants in their study, a good participation process is credible and legitimate, and maintains popular acceptance for outcomes decided, while for others it is one that is able to produce technically competent outcomes. A third set of participants emphasized the importance of fairness and procedural justice, while a fourth saw good participation as involving a process that educates and promotes constructive discourse.

Whichever of these views are held by planners, there is broad consensus that water resources problems are complex and multi-disciplinary; decisions are affected by, and affect, a broad range of stakeholders and actors, each of whom has their own knowledge and perspective of different aspects of the system about which decisions are being taken [6]. Participation is key to ensuring that the full breadth of existing knowledge is represented in the decision-making process. It is this amalgamation of different knowledge and perspectives that simultaneously makes participation so important but also so challenging [7]. When divergent world views and knowledge are brought into close proximity, the potential for conflict is great (ibid). A key challenge for participatory water resources planning, therefore, is finding ways to conduct participatory processes that manage this risk of conflict, so that the fruits of participation can be realized.

Shared Vision Planning (SVP) is a highly structured approach to planning that incorporates meaningful participation into each stage of traditional multi-objective planning [2]. First conceived for the National Drought Study [8] by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, it requires a team be involved in each step of the decision-making process, from problem identification to plan implementation. This team should be composed of stakeholders (those able to affect, and affected by decisions taken), decision-makers, and experts [2]. Collaborative modelling is used as a mechanism through which multiple understandings can be brought together to identify and resolve disputed causal effects and create consensus and transparency regarding the underlying system as a starting point for participative decision making (ibid). As such, it promises a tangible mechanism for effective conflict resolution in participatory approaches to water management. This paper explores the ability of SVP to manage conflict in the case of regulation planning for Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River.

2. Background to the Lake Ontario St. Lawrence River Regulation

Researchers and practitioners in the water sector increasingly recognise that the management of water resources is synonymous with the management of conflict [9,10,11,12]. Andrew [13] identified a number of reasons that natural resource management is particularly prone to conflict: (1) the widespread use of natural resources by large, diverse, and geographically dispersed groups creates complex networks of people and entities with differing power and influence; (2) the problem is compounded by the fact that the interconnectedness of the natural environment means that the actions of one group can have an impact on other groups a great distance away (i.e., upstream/downstream effects); (3) the use of the resource can also have different meaning to different people (i.e., economic livelihood for some; a way of life and cultural identity to others); (4) the diminishing supply of some natural resources may result in ‘structural-scarcity’ and unequal distribution.

Recognizing the potential for conflict, and the need to cooperate, in the management of waterways along their shared border, the United States and Great Britain (on behalf of Canada) entered into the Boundary Waters Treaty (“BWT”) in 1909 and created the IJC. The joint Canada–USA staffed IJC and its various Boards has two basic responsibilities—to act on applications and issue orders if approved, and to conduct studies under formal references from the governments. The IJC is made up of six Commissioners, three appointed by the President of the USA and confirmed by the U.S. Senate, and three appointed by the Canadian Governor in Council, essentially the Prime Minister. The basic aim of the IJC and the BWT is to prevent and resolve disputes. Commissioners act not as representatives of their national government but in the common interest of the people of the basins the IJC works in.

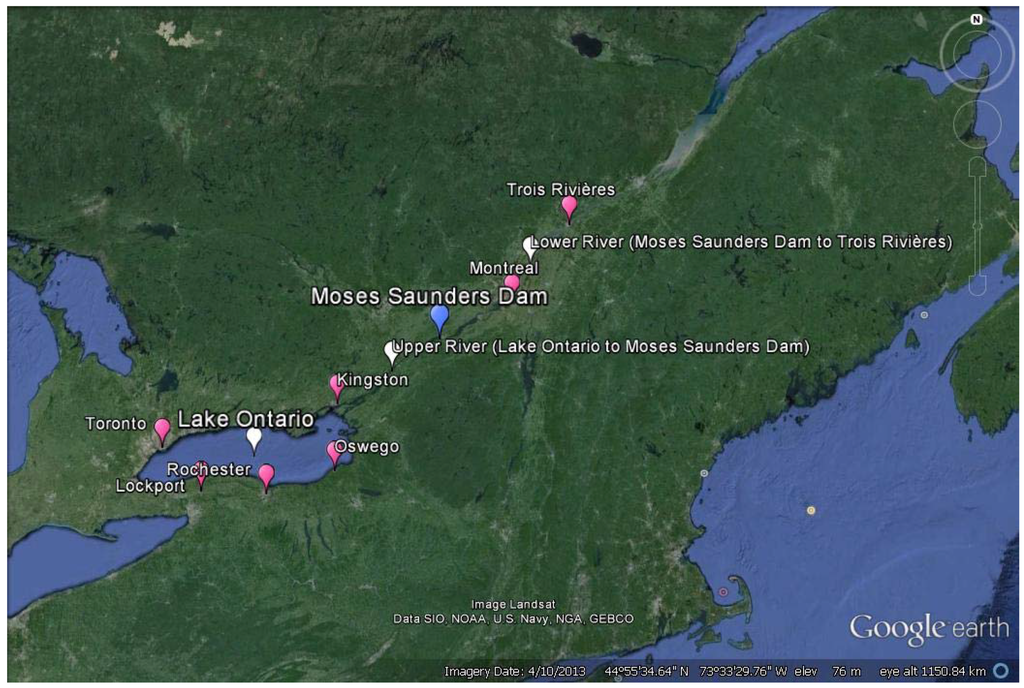

In response to applications from both national governments, the IJC issued an Order of Approval in 1952 (and amended it in 1956) for the construction of the St. Lawrence River Hydropower Project. Figure 1 shows the location of the resulting Moses Saunders Dam in relation to Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River Drainage Basin.

Figure 1.

Map of Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River.

Among the provisions contained in Article VIII of the BWT is a ranking of interests to be considered when devising regulation plans, set out as follows [14]:

- 1

- Uses for domestic and sanitary purposes;

- 2

- Uses for navigation, including the service of canals for the purposes of navigation;

- 3

- Uses for power and for irrigation purposes.

Plan 1958-D was the management plan formulated for regulation of the dam; it respected this order of precedence and since 1963, regulation of Lake Ontario water levels and outflows have occurred under this plan. Notably absent is any mention of the environment and certain special interests such as shoreline property owners and boaters, although the BWT does require the IJC to give all interested parties opportunities to be heard. Plan 1958-D was based on hydrologic conditions experienced from 1860 to 1954. Since that time, there have been changes to water flow patterns, climate conditions, and the composition of interested stakeholders and, as a result, this plan has become outdated [15]. As a consequence, the plan is frequently deviated from, following an unofficial plan referred to as Plan 1958-D with Deviations (Plan 1958-DD).

By 1993, the IJC was receiving numerous complaints, especially from environmental groups and recreational boaters, that the regulation plan was not meeting their needs and as a result the IJC recommended that the Order of Approval be amended to better reflect the current needs of the users and interests of the system [15]. Embracing a new spirit of participatory management, the IJC created the International Lake Ontario St. Lawrence River Study Board (the “Study Board”) in 1999 and entrusted it to perform a comprehensive scientific and environmental analysis of water levels and flow regimes in the LOSLR system and mandated that this effort include public input [16]. A novel feature of the study process was the creation of a special group of stakeholders called the Public Interest Advisory Group (PIAG). The PIAG was an independent advisory group, made up of volunteers, who created a link between the general public and the Study Board. The Canadian and U.S. PIAG chairs were also members of the Study Board; they were tasked to provide advice to the board, feedback to the public, and input at all stages of the process [15]. Between 2000 and 2006, an extensive study was undertaken to combine scientific knowledge, modelling, and a plurality of viewpoints in the development of a new regulation plan. The Study Board assembled numerous public interest and technical committees to model the lake and river systems and a Shared Vision Planning approach was implemented to steer and integrate the results [15,17].

A collaborative model was developed as part of the SVP approach. Technical work groups were tasked to undertake collaborative research and modelling of one aspect of the overall system. The task groups were: environmental; recreational boating and tourism; coastal processes; commercial navigation; hydroelectric power; and domestic, industrial, and municipal water uses [15]. Stakeholders were assigned to Work Groups based on their interests and concerns. These individual group models were then integrated so that regulation plan options could be simulated and the consequences in terms of multiple objectives (which were also defined by the Work Groups) assessed (ibid). Based on extensive ecosystem and environmental modelling, three alternative plans were developed that incorporated the preferences of interested stakeholders (ibid). This was followed by a period of public consultation that resulted in the IJC choosing to back one of the plans, which was subsequently referred to as Plan 2007. Having selected Plan 2007, the IJC held more extensive public hearings on this option. During the hearings it transpired that the Plan was widely opposed; environmentalists thought that the plan failed to offer the environmental protection they sought, while other stakeholders saw no benefit in the plan for their concerns.

Following the Plan 2007 public hearings and almost complete opposition to that plan, the IJC created one formal Work Group to find a solution. This Work Group was chaired by the IJC and made up of governmental representatives. They used all the work of the Study Board and some of the technical experts and came up with Plan Bv7 (Plan B being one of the three options proposed by the Study Board). Plan Bv7 provided a wider range of flow levels that more closely matched natural flow patterns than the more tightly regulated levels found in the originally proposed Plan 2007 and Plan 1958-D [18]. Facing strong opposition from New York State South Shore property owners concerned about flooding, shoreline erosion, and damage to build structures, Plan Bv7 was further modified to address their concerns. The current regulation proposal, termed Plan 2014, has undergone several iterations and has, at the time of writing, been submitted to the governments of Canada and the United States for approval. The plan comprises both a new approach to the management of water levels and an adaptive management plan, which aims to overcome any data and modelling uncertainties and to allow for continued improvement in the future [18]. Plan 2014 underwent an extensive period of public comment during the summer of 2013; dozens of stakeholder groups and hundreds of individuals participated in these occasionally contentious proceedings. In addition to these in-person hearings held in six cities in Canada and the USA, many individuals have made their positions known in a variety of other forums—to their elected representatives, to the media, at town hall meetings, in published articles, and online. A summary of the timeline of events can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Timeline of events.

A full description and analysis of the public participation process up to and including the 2008 public hearings can be found in Carr, Loucks, and Blöschl [19]. At this mid-point in the whole process, they concluded that there were some considerable strengths of the IJC’s approach including good access to information and meetings, commitment to involving all potentially affected communities and interest groups resulting in broad representation, impartial facilitation, and inclusion of a wide variety of knowledge. They specifically compliment the PIAG, describing them as, “dynamic, dedicated, and well supported”. The present paper extends the work undertaken by Carr, Loucks, and Blöschl through an analysis of the 2013 hearings on Plan 2014, focusing on the extent to which the SVP approach employed by the IJC was effective in managing conflict during LOSLR regulation planning. To frame the research, the following research questions were posed: (a) To what extent was agreement reached by stakeholders in support of Plan 2014? (b) What evidence is there that the resolution process enabled stakeholders to overcome potential conflict and reach agreement? (c) What residual conflict persists and what is the root cause of this conflict? Finally, consideration is given to whether any opportunities exist to move the conflict further towards amicable resolution, and what lessons might be learnt more broadly.

3. Methodological Approach

The study of environmental conflict is, essentially, the study of stakeholder conflict. One definition of “stakeholder” that has been widely cited in the non-profit and natural resources management literature was first proposed by Freeman more than 30 years ago as: “any group or individual that can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organization’s objectives” [11,12,20]. As such, this definition casts a broad net capturing actors, individuals, groups, and associations, whether formal or informal, holding different interests, perspectives, and viewpoints. In the current context, the IJC is confronted with the difficult task of balancing the competing demands of stakeholders and actors, some of whom hold strongly divergent views.

To determine the extent to which the IJC’s planning process was effective at conflict management, a scheme was developed to identify, categorize and analyse the stakeholders interfacing with the IJC on the matter of Plan 2014. The IJC actively embraced the principles of collaborative and participatory management during the period of 14 years that a new water level regulation plan has been under consideration. A large number of stakeholder groups were engaged in various phases of the study. The IJC website provides copies of audio recordings and transcriptions of the public and technical hearings conducted during 2013. These data, which contain numerous statements made by a wide variety of actors and stakeholders, have been systematically analysed as part of the present work with the goal of gaining insight into the stakeholder universe interfacing with the IJC on Plan 2014.

The present analysis took the following steps, based on the methods and tools outlined by Freeman [20], Mendelow [21], Mitchell, Agle, and Wood [22], Elias, Cavana, and Jackson [23], and Elias [12].

To assess the extent that agreement was reached by stakeholders in support of Plan 2014:

- Stakeholders were identified and classified on a stakeholder chart;

- A snapshot of stakeholder positions at the time of the technical hearings was visualised through a stakeholder mapping exercise;

To explore the effectiveness with which the IJC’s planning process enabled stakeholders to overcome potential conflict and reach agreement, it was necessary to first determine the potential for conflict. This was achieved by:

- iii.

- Undertaking a content analysis to identify where stakeholders held potentially conflicting needs, values, beliefs, or expectations relevant to the resolution process;

The potential conflict was then compared to the final positions achieved through the resolution process to see if potential conflict had been effectively avoided.

Finally, to assess whether residual conflict persists and identify the root causes of this conflict:

- iv.

- Content analysis of the statements made by stakeholder classes who remain opposed to Plan 2014 was undertaken with the goal of elucidating the root causes of opposition.

Each of the methods is described in more detail, prior to results being presented, in the subsequent section.

4. Results

4.1. Categorisation of Stakeholders into Classes

The first task undertaken during the stakeholder analysis was categorisation of stakeholders into classes. The challenge presented by the process of categorisation is to find an appropriate level of aggregation of stakeholders that allows the stakeholder universe to be simplified to a manageable number of groups and perspectives without over-generalising and losing potentially important detail about stakeholder interaction. The goal was to split the stakeholder universe into a limited number of coherent and logical classes along important dividing lines. At the beginning of the stakeholder analysis process it was not clear exactly where these lines could most appropriately be drawn, however. An initial best guess was made and stakeholders were roughly classed as belonging to one of the following groups: environmental concerns, shipping concerns, hydroelectricity concerns, fishing concerns, First Nations, and the general public. As the stakeholder analysis progressed by undertaking the steps described below, it became apparent that these classes did not capture some of the most important attributes of the dispute. Classes were therefore continually re-shuffled in an iterative process throughout the analysis.

For example, during the stakeholder mapping exercise the initial class “general public” was found to be particularly incoherent and heterogeneous so additional effort was put into identifying dividing factors that diversify public opinion so that more homogenous sub-classes could be formed. During the first attempt at this process speakers were categorised geographically according to their state or province of origin. As the analysis proceeded, however, it became clear that geographic divisions could not adequately account for position differences. Opinion varied within the state of New York according to whether the speaker was a Lake Ontario riverside property owner or not. Conversely, the perspective held by those living adjacent to the St. Lawrence River did not appear to diverge depending upon whether the person lived in New York, Ontario, or Quebec. For this reason, the sub-categories used for the general public were “Riverine South Shore”, “Non-riverine South Shore”, and “St. Lawrence”. The perspective of those holding political office was kept separate from individuals speaking on behalf of themselves or small community groups.

In general, if no discernible differentiation could be found between two groups in terms of either position or rationale for that position (see following sections), the groups were merged into one group. If differences were identified in position or rationale within a group, but no apparent logical divisor could be identified, the group remained as one group (albeit one less homogenous group). Table 2 shows the final classification of stakeholders into classes that aim to remain logical but as homogenous as possible.

Table 2.

Final classification of speakers participating in the 2013 public and technical consultations.

4.2. Stakeholder Mapping

A key step in Freeman’s analysis of stakeholders is the preparation of a high-level map of the universe of stakeholder classes [20]. In the LOSLR case study, stakeholders were analysed to identify their positioning in terms of the degree of support or opposition to the proposed Plan 2014. During the IJC’s public and technical consultations in 2013, each speaker was permitted to speak for at least three minutes, longer if time permitted, and present their opinion on Plan 2014.

Each speaker’s statement was examined for evidence to determine the speaker’s position as either “strongly supportive”, “supportive”, “neutral”, “opposed”, or “strongly opposed”. Many speakers explicitly stated their position as for or against Plan 2014, which simplified this task. The determination of whether a speaker was “supportive” or “strongly supportive” was made on the basis of whether the speaker also raised concerns about Plan 2014 during their speech. For example, one speaker said that their organization, “recognizes and supports the intent of Plan 2014” but also that they “have several concerns and recommendations”. This speaker was therefore categorised as “supportive” rather than “strongly supportive”. A distinction between “opposed” or “strongly opposed” was made on the basis of whether the speaker felt there was a need for a new plan but had strong enough concerns with the Plan to oppose it, or whether they felt that there was no need to make changes to the existing plan which they feel works adequately. A typical quote of a speaker who was determined to be “opposed” is, “we should not change the Plan until we have something that is more equal to all interests”. This quote shows that the person is open to changing the regime but feels Plan 2014 is unfair and therefore their position is in opposition to it.

Despite efforts, made in the prior step, to classify stakeholders into coherent classes, some classes retained a degree of heterogeneity (when there was not further apparent logical basis on which to further divide a class) and therefore each aggregated stakeholder class was plotted relative to the range of positions that their sub-groups may hold. While there is undeniably a level of subjectivity to this approach, it is still a useful exercise as even a rough indication of position is useful to select stakeholders for more detailed exploration in the next step of the study.

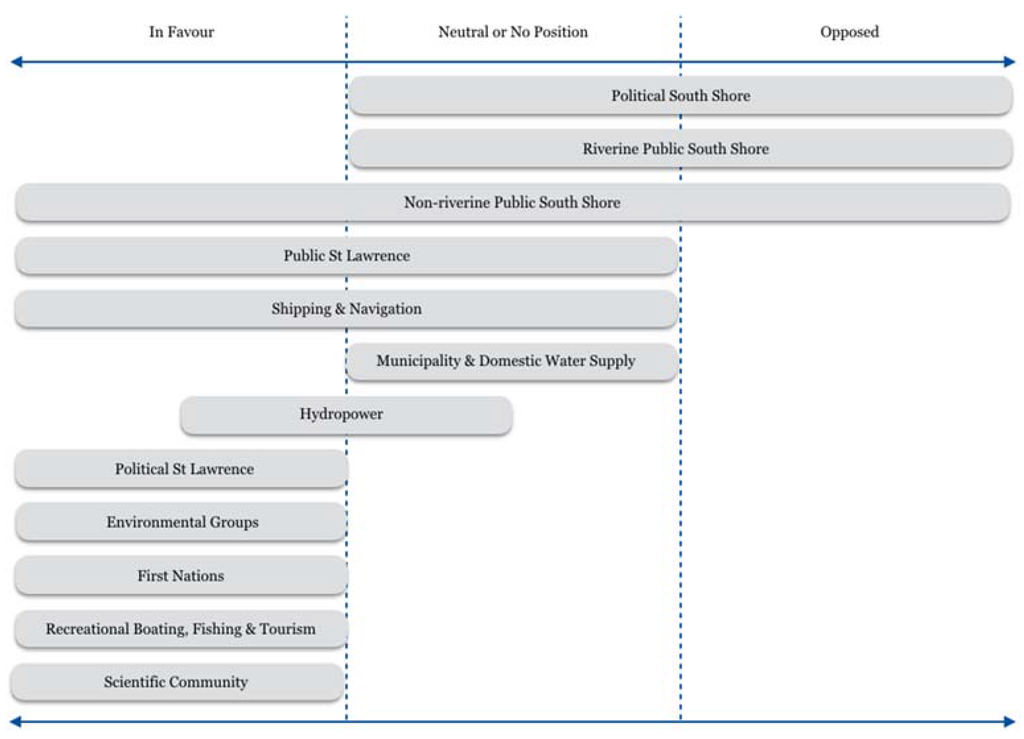

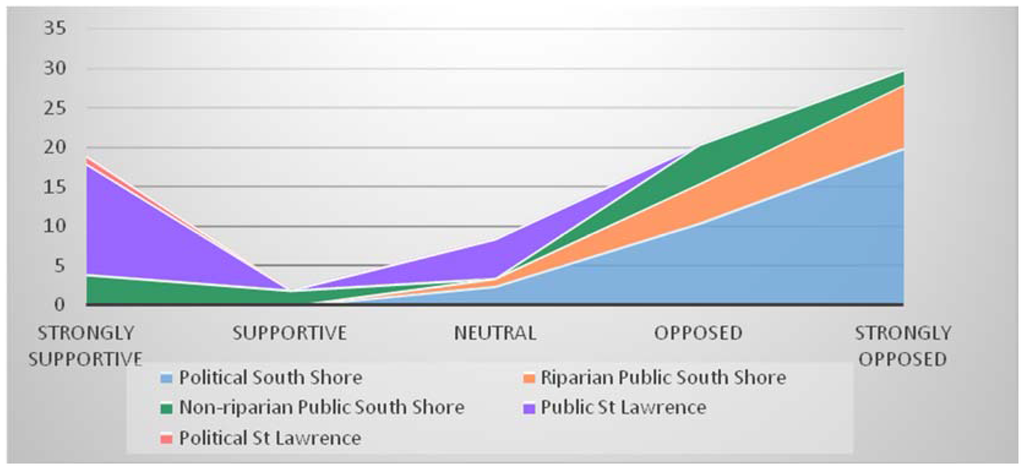

Figure 2 shows results from the stakeholder mapping process, where stakeholder classes are mapped according to their position in terms of degree of support for Plan 2014. Evidence of the rationale behind the assignment of position of the stakeholders, excluding the general public, on the stakeholder map can be found in Table 3. Figure 3 looks specifically at the spread of opinion within the general public and their elected leaders, and the following section takes a closer look at the arguments of the Opposed South Shore public.

Figure 2.

Final position of stakeholders on Plan 2014.

Table 3.

Evidence of assigned position of stakeholders (excluding the general public) towards Plan 2014.

Figure 3.

2013 position of the public on Plan 2014.

4.3. Content Analysis

The content of the available transcripts was analysed with the goal of understanding the perspectives of each type of stakeholder, to assess the potential for conflict as a first step to assessing the success or failure of the IJC’s process. For each stakeholder class, consideration was given to what the stakeholder needs or wants (i.e., what their stake is), the argument they use to support their position, the underlying values and beliefs that form the basis of their position, and any expectations they hold regarding the resolution process. A summary of the needs or wants of key stakeholders is provided in Table 4 below.

Table 4.

Needs or wants of key stakeholders.

An important limitation of the approach that was used was that the data on which the analysis is based are statements made at the end of the resolution process. Ideally a content analysis would have been undertaken both before and after the process to identify perspective changes. One of the significant attributes of the IJC’s process was the effort put into developing a shared understanding of the environmental, technical, and social dimensions of the dam management regime through the collaborative modelling process. It would have been very interesting to see how lines of arguments, and the data upon which arguments were based, were changed by the shared visioning process. Despite this limitation, the content analysis revealed two features of the conflict with great potential to lead to conflict.

The potential for conflict between First Nations stakeholders and other stakeholders became evident through the content analysis process. The values of the Mohawks of Akwesasne stood in stark contrast to those of other stakeholders. The content analysis revealed a completely different worldview from that held by the other stakeholders. It was apparent that they had a structural concern that a process be employed that valued and included their way of knowing. In addition, previous relationship issues were referred to that highlighted the potential for conflict due to strained relations.

The potential for interest-based conflict was also particularly apparent. While the needs of some stakeholders were divergent but not necessarily mutually exclusive (for example, predictable water levels, high water levels during peak commercial times, and more variation in flow do not seem mutually exclusive), others simply seemed to conflict. The water regime cannot be simultaneously consistent in flow (as required by hydropower) and level (as required by shoreline property owners) and varied in flow and level (as required by environmental groups).

The final goal of this study was to identify the root causes of residual conflict. Having identified in preceding stages of the study that opposition to Plan 2014 persists among a subset of the public living along the South Shore and their local political leaders, content analysis of their statements was also used to identify complaints made by this group regarding Plan 2014. The outputs of this analysis are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Complaints of the Opposed South Shore public.

5. Discussion

5.1. Extent of Agreement Reached

Figure 2 shows that the vast majority of stakeholders were supportive of Plan 2014 at the time of the public and technical consultations. With the exception of a group of a few hundred shoreline property owners based in New York State and their local political leaders, consensus was reached across the majority of stakeholders in support of Plan 2014.

5.2. Effectiveness of the IJC’s Resolution Process

The challenge presented to the IJC to manage conflict over regulation of water levels in LOSLR was significant. The IJC process has achieved many successes. Clear examples can be found of stakeholders changing their position to back the proposed regulation changes. One such example can be found in the statement of JH, speaking on behalf of the Hamilton Harbour Remedial Action Plan. In his 2013 statement to the IJC he recalls, “I appeared before the International Joint Commission in this same room I believe and I had suggested that at that time the Commission not approve Plan 2007 … I’m very pleased to tell you that on behalf of our Remedial Action Plan Group … that we’re very pleased to see the work that’s gone on, and you have our support for Plan 2014”. The commission then asked JH what the difference is between the 2007 Plan and Plan 2014 that led to this change in position. JH responded that Plan 2014 goes further to mimic the natural variation in the water level fluctuation that is so important for ensuring biodiversity in the region. This example is typical of many in the environmental community who wanted improved/greater water level fluctuations, and whose position was opposed to Plan 2007 and supportive of Plan 2014.

A further significant success of the IJC was the effectiveness with which they were able to achieve consensus between First Nation communities and the majority of stakeholders in support of Plan 2014. In the technical hearing in which First Nations participated, two major ongoing issues were identified by Chief Brian David that could have impacted greatly on the conflict resolution process implemented by the IJC. The first is regarding land claims being made in New York State and the Province of Quebec, along with the North Shore of Cornwall Island. The second relates to longstanding problems over the rights of First Nations individuals to travel freely within their territory without being restricted passage by the presence of international borders. Against this backdrop, where relations must undoubtedly have been severely affected, obtaining the support of the First Nations communities was a victory.

The content analysis revealed that inclusion and influence over the decision-making process was important to the First Nations communities; “We have a concern that we know what’s going on and we have some influence over the decision making”. During the consultation process Henry Lickers, Director of the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne Department of the Environment and an important First Nation elder with great influence in the community who has been involved in the IJC’s process for many years, is quoted as saying, “We know that there are many other teachers in this world and we sit here today and listen to our problems that we have, but we know that we have the knowledge that came to us down the corridors of time from elders and ancestors that have preceded us and of us have those trusted elders that we have listened to in the past and hear their knowledge today and we will build on that knowledge that this will be a better place. And so I ask you to bring together your minds and think about those teachers of the world, and can we agree that they are important to us?” indicating a concern that the knowledge of the Mohawks be treated as equal to that of other types of knowledge. A major success of the IJC’s process is best explained by Mr. Lickers, who said that, “I think at that time a lot of the thinking from Akwesasne went forward in recommendations... I think we partly penned it, or actually had influence in the conception of it… This is a really impressive effort and I think that you’re trying to be sensitive and I really want to applaud you and thank you for this effort”.

5.3. Root Causes of Residual Conflict

While the proportion of remaining opposition may be small, the impact of this group on the overall planning process has been significant to date. The content analysis of opposition statements identifies a number of unresolved concerns stated by the Opposed South Shore during the public hearings of 2013.

Comments made during the public hearings reveal issues in the relationship between the Opposed South Shore and the IJC. In particular, there seems to be a lack of trust by some in the IJC, which is apparent from concerns held by some of the public that the IJC had an alternative agenda, was holding secret meetings to which they were not invited or informed, and had data and graphs that they were not sharing. One speaker also questioned the ability of the U.S. and Canadian governments to work effectively together. The accuracy of the data used in the modelling process was refuted, calling into question the validity of the models and thereby the analysis of the likely impacts of management regime change. A particular concern was expressed as to the valuation given to South Shore properties, which was felt to be outdated.

The IJC’s process was directly criticized by some, who argued that an environmental review was lacking, or that a review had taken place but no effort had been made to respond to criticisms made during the review, and finally that no emergency risk maps had been produced. Many questioned the fairness of any effort to update or change dam management policy at all, given that decisions had been taken and structures built on the basis of previous policy decisions. The statement made by RK (Ontario, NY), “Why fix something that is not broken” was the most extreme of a variety of statements that revealed a lack of either understanding of, or valuing of, the local environment. A common theme amongst the Opposed South Shore was the belief that ‘muskrat’ (or other indicator species) concerns were not as valid as their own. Some used the argument that muskrats do not pay tax. The values held by these individuals are therefore at odds with a core value of many of the supporters of Plan 2014, which led directly to the goal of increased biodiversity.

Many of the statements make it clear that the speaker felt too much emphasis was placed on the interests of hydropower and shipping concerns, or larger downstream cities, at the expense of South Shore property owners. They disputed Plan 2014 on the basis that their interests are were not being adequately safeguarded.

The above summary reveals that the Opposed South Shore presented the IJC with a broad array of criticism in 2013, which disputed Plan 2014 on multiple fronts. Is it really the case that this stakeholder class believes that the IJC are engaged in secret meetings and are prepared to put their reputations on the line by basing their arguments on dubious data, to manipulate the process because they have an alternative agenda to serve hydroelectric and commercial shipping companies? It is thought more likely that there is, in fact, an alternative root cause of the conflict that has led to a resolution within the public to refute Plan 2014 by any means necessary.

This seems particularly true given the length to which the IJC went to conduct a process that had all the hallmarks of a participative and democratic process; Carr, Loucks, and Blöschl [19] found little evidence of bias in the statements of the study board facilitators in their analysis of the participative process. The IJC put in place consultation and hearing processes that allowed all stakeholders to have a voice; the public had a direct link to the Study Board through the PIAG and individuals had ample opportunity to express their opinion through both three-minute speeches at the public consultations and via letters and online comment. By making recordings and transcripts of the public consultations freely available, the IJC sought to increase the transparency of the process. The Opposed South Shore, in particular, were also represented by citizen action groups who were invited to participate in the technical working groups.

Some claims made by the Opposed South Shore, for example that no effort had been made to respond to criticisms made during the environmental review process, seem to have little connection with reality. The evidence of extensive environmental sampling and analysis is available for all to see and more time and money was spent on this aspect of the study than any other. If the root cause of the Opposed South Shore’s position can be identified, perhaps it will be possible to gain insight into how the conflict can finally be resolved.

Consideration was given to whether distance from the problem-solving process was a factor in determining an individual’s position with regards to Plan 2014. It is noteworthy that those individuals who were involved in the Technical Working Groups through citizen organisations remained in opposition to Plan 2014 when final positions were stated, as well as those not directly involved. This suggests that even full integration with the IJC’s resolution process was insufficient to bring the strongly Opposed South Shore on board with the Plan. While the SVP process succeeded to align the positions of the vast majority of stakeholders, it failed to align the position of the general public.

It is posited that the Opposed South Shore property owners are (or at least perceive themselves to be) ‘playing’ a ‘game’ of a slightly different nature from the other stakeholders. Every stakeholder, except for the Opposed South Shore, has something to gain through the introduction of new water level regulations. Therefore, each of the other stakeholders is playing a collaborative game in which they want to achieve final agreement; the resolution process is about negotiating how much they can benefit. The Opposed South Shore, conversely, believes that they have nothing to gain from any new plan. Their objective is to keep water levels constant, which is in direct conflict with the principal objective of any new plan (i.e., to return water levels to a more natural and varied pattern). The Opposed South Shore, therefore, is playing a zero-sum game in which there is no hope of benefitting from new plans. The IJC itself has reinforced this position in the past. They stated that “the current Regulation Plan 1958-D with Deviations comes close to minimizing damages for Lake Ontario shoreline property owners” [15]; this implies that finding alternatives that bring benefits to this stakeholder group is highly unlikely. They explicitly acknowledge the zero-sum nature of the problem when they say that, “Changes to the criteria and existing operation plan are not possible without harm to some interests” and go on to justify this harm by saying that the, “majority of Board members do not consider these damages a disproportionate loss” [15].

While the Opposed South Shore perceive themselves to be playing a zero-sum game, the benefits that can be brought by any collaborative process are arguably severely restricted. They have fairly limited power in comparison to the other stakeholders. Perhaps the only strategy which they feel to be available to them is to exert pressure on the IJC by standing in the way of any resolution process—a strategy which to date they have implemented highly successfully (as evidenced by the fact that the resolution process has now been going on for over 14 years).

5.4. Moving Forward

The positions of the stakeholders are now so well entrenched that reaching consensus appears an elusive goal. A solution to this impasse would require a significant re-framing of the problem such that the Opposed South Shore perceive themselves as having something to gain from committing to the resolution process, perhaps by bringing the possibility of compensation to the table. It should be noted, however, that taking a route involving compensation is not without difficulties of its own. For example, issues such as whether or not the owners of structures that have been developed during the time the studies and resolution process have been ongoing should be compensated are likely to be highly contentious. There is also the issue of whether compensation should be used to relocate those living in homes adjacent to Lake Ontario, or whether compensation would be for the rebuilding of damaged property following flood events. This could equally lead to a highly charged and politically contentious debate.

With every conflict there is a necessary compromise to be made between urgency and pressure to implement timely solutions, and a desire to ensure a democratic process is followed that encourages collective action. In the case of the LOSLR conflict, as with other conflicts, some may feel that the emphasis has been placed too firmly on achieving consensus at the expense of timeliness, whilst others may hold the opposite opinion. The fate of LOSLR now lies in the hands of the Governments of Canada and the United States of America, who must weigh up the increasing urgency and impatience to implement a new water regulation management plan against a desire to implement a solution that is supported by all stakeholders concerned. It is the authors’ opinion that, as the environmental damage occurring due to the employment of Plan 1958-DD has now been demonstrated, the urgency to act outweighs the desirability of reaching full consensus. It is possible that the governments will concur with Plan 2014 for the greater good of both countries, and address shoreline property owners separately. It is not clear, at this time, exactly how much political power these few hundred individuals have to influence international boundary decisions.

5.5. Broader Lessons

The successes of the IJC’s approach suggest that SVP can be effective at managing potential conflict between stakeholders who have something to gain from participating meaningfully in the process. It is probable that any participatory approach will fail to completely eliminate conflict where gains to one interest can only be realized at the expense of another. In such cases, other mechanisms, such as the possibility of compensation, might usefully be brought to the table to complement the SVP approach.

6. Conclusions

It is concluded that while the Shared Vision Planning process employed by the IJC had some significant successes, notably the success that has been achieved with regards to integration of First Nations and environmental concerns, the IJC’s public outreach and participation efforts have not been successful in reconciling the positions of all stakeholders. There is a distinct group of shoreline property owners in New York State who remain opposed to Plan 2014 because they perceive that they can only lose out from any regulation change. They are therefore unlikely to be motivated to engage productively in any planning dialogue. A solution would require that the problem be reframed so that this group has something to gain from a successful regulation plan resolution, which may involve bringing the prospect of compensation to the table. The fate of Plan 2014 now lies with the governments of Canada and the United States of America, who may choose to concur with the Plan for the overall public good of both countries and address shoreline property owners separately.

Acknowledgments

The research team gives thanks to Bill Werick, who provided feedback to drafts of this paper. This study was funded by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) Partnership Development Grant, held by Jan Adamowski, and the Brace Centre for Water Resources Management at McGill University.

Author Contributions

Research was conducted and the manuscript written by Alison Furber, building on an earlier paper drafted by Meetu Vijay. Murray Clamen contributed expert knowledge of the LOSLR context and the history and workings of the IJC, and contributed ideas and comment throughout development of the paper. The research was initiated, supervised and reviewed by Jan Adamowski and Wietske Medema.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BWT | Boundary Waters Treaty |

| IJC | International Joint Commission |

| LOSLR | Lake Ontario & St. Lawrence River |

| PIAG | Public Interest Advisory Group |

References

- Carr, C. Stakeholder and public participation in river basin management—An introduction. WIREs Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 2015, 2, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, R.N.; Cardwell, H.E.; Lorie, M.A.; Werwick, W. Disciplined planning, structured participation, and collaborative modeling—Applying Shared Vision Planning to water resources. J. Am. Water Res. Assoc. 2013, 49, 614–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A ladder in citizen participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Korff, Y.; Daniell, K.A.; Moellenkamp, S.; Bots, P.; Bijlsma, R.M. Implementing participation water management: Recent advances in theory, practice and evaluation. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webler, T.; Tuler, S. Public participation in watershed management planning: Views on process from people in the field. Res. Hum. Ecol. 2001, 8, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, K.K.; Fisher, K.T.; Dickson, M.E.; Thrush, S.F.; le Heron, R.L. Improving ecosystem service frameworks to address wicked problems. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, A.; Siebert, R.; Barkmann, T. Incrementality and regional bridging: Instruments for promoting stakeholder participation in land use management in Northern Germany. Soc. Natl. Res. 2016, 29, 868–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute for Water Resources (IWR). Managing Water for Drought; IWR Report 94-NDS-8; Institute for Water Resources: Alexandria, VA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, B. Resource and Environmental Management, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall: Harlow, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Peltonen, L.; Sairinen, R. Integrating impact assessment and conflict management in urban planning: Experiences from Finland. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2010, 30, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanghellini, P. Stakeholder involvement in water management: The role of the stakeholder analysis within participatory processes. Water Policy 2010, 12, 675–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, A.A. A systems dynamics model for stakeholder analysis in environmental conflicts. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2012, 55, 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, J.S. Potential application of mediation to land use conflicts in small-scale mining. J. Clean. Prod. 2003, 11, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Joint Commission (IJC). Guidance in Seeking Approval for Uses, Obstructions or Diversions of Waters under the Boundary Waters Treaty of 1909. Available online: http://www.ijc.org/files/tinymce/uploaded/Guidance-in-Seeking-Approval-for-Uses_EN.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2016).

- International Joint Commission (IJC). Options for Managing Lake Ontario and St. Lawrence River Water Levels and Flows. Final Report by the International Lake Ontario–St. Lawrence River Study Board to the International Joint Commission. 2006. Website. Available online: http://www.ijc.org/loslr/en/library/LOSLR%20Study%20Reports/report-main-e-6KB.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2016).

- International Joint Commission (IJC). Plan of Study for Criteria Review in the Orders of Approval for the Regulation of Lake Ontario–St. Lawrence River Levels and Flows. Report by St. Lawrence River–Lake Ontario Plan of Study Team to the International Joint Commission. 1999. Available online: http://losl.org/PDF/PlanOfStudy_en.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2016).

- Langsdale, S.; Allyson, B.K.; Elizabeth, B.; Erik, H.; Scott, K.; Rick, P. Collaborative modelling for decision support in water resources: Principles and best practices. J. Am. Water Res. Assoc. 2013, 49, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Joint Commission (IJC). Lake Ontario–St. Lawrence River Plan 2014: Protecting against Extreme Water Levels, Restoring Wetlands and Preparing for Climate Change. A Report to the Governments of Canada and the United States by the International Joint Commission. IJC Website, 2014. Available online: http://www.ijc.org/files/tinymce/uploaded/LOSLR/IJC_LOSR_EN_Web.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2016).

- Carr, G.; Loucks, D.P.; Blöschl, G. An analysis of public participation in the Lake Ontario–St. Lawrence River study, Chapter. In Water Co-Management; Grover, V.I., Krantzberg, G., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013; pp. 48–77. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Mendelow, A. Stakeholder mapping. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Information Systems, Cambridge, MA, USA, 7–9 December 1991.

- Mitchell, R.; Agle, B.; Wood, D. Towards a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 853–886. [Google Scholar]

- Elias, A.A.; Cavana, R.Y.; Jackson, L.S. Stakeholder analysis for R & D project management. R D Manag. 2002, 32, 301–310. [Google Scholar]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).