Abstract

The contamination of groundwater in karst coal mining areas presents a unique environmental challenge due to the interplay between fragile hydrogeology and intensive anthropogenic activity. This study investigated the concentrations, sources, and health risks of characteristic contaminants in groundwater from a karst coal mining area, aiming to provide a scientific basis for groundwater pollution control. Thirty-two groundwater samples were analyzed for nine target contaminants. Principal component analysis (PCA) and a health risk assessment model were integrated to identify pollution sources and evaluate health risks. Results showed that the concentrations of Fe, Mn, Fluoride, Pb, and Sulfate exceeded the Class III limits of the “Standard for Groundwater Quality” (GB/T 14848-2017), with maximum exceedance multiples of 3.60, 1.51, 1.08, and 1.22 times the standard limits, respectively. The maximum concentrations of Mn, Fluoride, and Pb exceeded the WHO guidelines by factors of 4.75, 0.67, and 1.00, respectively. Furthermore, the Pb concentration also surpassed the USEPA standard by a factor of 0.33. PCA identified three principal components, which together explained 71.065% of the total variance and were attributed to mining activities (PC1), mixed natural and anthropogenic sources (PC2), and natural geological processes (PC3), respectively. The health risk assessment reveals significant risks: arsenic poses a carcinogenic risk (CR > 10−4), while both arsenic and Fluoride contribute to non-carcinogenic risks (HI > 1). The cumulative exposure from these contaminants demands immediate attention.

1. Introduction

Coal resources are the cornerstone of China’s energy structure [1]. Groundwater, representing the dominant freshwater resource (comprising over 95% of Earth’s liquid freshwater), sustains drinking water supplies for approximately 2.5 billion people and irrigates more than 40% of global croplands [2,3,4]. However, there is always an opposition between coal mining and groundwater [5,6,7,8]. Under natural conditions, groundwater chemistry is primarily governed by atmospheric precipitation, evaporation, and water–rock interactions; however, intensive and prolonged coal mining activities increasingly alter the hydrochemical characteristics of aquifers in mining areas [9]. Empirical evidence from various coal mining regions underscores this impact. For instance, in the Zhongning area of Northwest China, Fluoride and nitrate concentrations in groundwater significantly exceeded drinking water standards [10]. Cheng et al. reported that long-term coal mining significantly disturbs groundwater systems, resulting in aquifer water characterized by elevated levels of Na+, , and total dissolved solids (TDS), thereby posing environmental health risks [10]. Bhuiyan et al. found that levels of Mn, Fe, Pb, Cu, etc., in most of the water samples in irrigation and drinking water systems in the vicinity of a coal mine area of northwestern Bangladesh exceeded the national and international standards [11]. Chandra et al. indicated that the average concentrations of Fe and Cd exceeded the limits by 1.43 times and 1.6 times, respectively, and Pb and Mn were close to reaching the permissible limits in groundwater samples near coalfield regions of India [12]. Furthermore, mining-induced aquifer damage can lead to a cascade of environmental issues, including groundwater level decline, water resource depletion, and the drying up of surface springs [13].

Guizhou Province is a representative karst region in southern China where approximately 75% of the terrain is underlain by karst formations [14]. Under natural conditions, karst groundwater often exhibits good quality and serves as a vital water source in many parts of China [15]. However, karst aquifers are commonly highly vulnerable to contamination, which is related to the fast recharge, discontinuous storage, and short residence time [16,17]. The release of toxic contaminants from tailings and waste rocks can pose a significant threat to human health [18]. Chronic exposure to Pb and Hg elements is associated with profound neurological and developmental impairments, as well as cardiovascular, renal, gastrointestinal, and hematological dysfunctions [19]. The general health effects of Fluoride on humans include affected or damaged soft tissues, muscles, erythrocytes, gastrointestinal mucosa, ligaments, spermatozoa and thyroid glands; brittle bones; inferior growth; Alzheimer disease; pain; or impeded movement due to bony and dental lesions [20]. Cd is a possible carcinogen and chronic exposure to elevated levels can lead to respiratory diseases [21]. Zn deteriorates human metabolism [21]. High-level inhalation exposure to Mn can cause central nervous system (CNS) damage and lead to various disorders, such as skeletal defects, infertility, heart disease, and hypertension [18].

Mining operations compromise groundwater quality through processes that are contingent upon hydrogeological conditions, coal seam geochemistry, and aquifer characteristics [22,23]. Mining activities can accelerate local groundwater circulation, enhance mixing effects, and intensify water–rock interactions, leading to more complex groundwater chemistry and damage to the hydrogeological structure [9,24]. Abandoned coal mines in well-developed karst areas especially pose significant hydrogeological challenges [25,26]. After the closure of a coal mine, rising water levels in mine shafts can lead to the seepage of water—carrying high loads of pollutants—into coal seams, roadways, and fractures, potentially contaminating nearby drinking water wells [27]. Additionally, large-scale excavation can induce secondary environmental challenges like ground subsidence and deformation [28]. Due to the concealment of groundwater systems, and their complex and rapidly mobile characteristics, once karst groundwater is contaminated it is extremely difficult to repair [29,30]. Hence, the study of the karst groundwater in mining areas is challenging.

Despite the acknowledged impacts of coal mining on groundwater quality, the source apportionment and integrated health risk assessment of contaminants in karst coal mining areas remain in the research stage. While health risks have been assessed in some mining areas, for the karst coal mining area, these assessments are rarely spatially linked to and informed by quantitative source apportionment results. This limits the ability to formulate targeted, source-specific risk management strategies for complex environments like karst coal mining zones.

To address these gaps, this study focuses on a typical karst coal mining concentration zone in Guizhou Province, China. We employ an integrated methodology combining principal component analysis (PCA) for source apportionment with a health risk assessment model. The primary objectives are to (1) characterize the spatial distribution of coal mining characteristic pollutants (CMCPs); (2) quantitatively identify and apportion their predominant sources (mining, mixed, and natural); and (3) evaluate the associated human health risks of CMCPs. This approach aims to provide a scientific basis not only for identifying pollution hotspots but also for prioritizing source-specific control measures, thereby contributing to the sustainable management of groundwater resources in vulnerable karst mining regions.

2. Study Area

2.1. Location and Climate

This investigation focuses on a region in northern Guizhou Province, China (Figure 1). The highest elevation is found in the southeastern part, while the lowest point lies in the western valley. The area is dominated by typical karst landforms, including corroded peak-cluster depressions, trough valleys, and low-mountain valleys [31]. Based on the on-site investigation, depressions and sinkholes are well-developed within the valleys, where the terrain is relatively gentle, with peak–valley height differences ranging from 20 m to 60 m. In contrast, the gullies exhibit significant incision, with relative elevation differences of approximately 300 m.

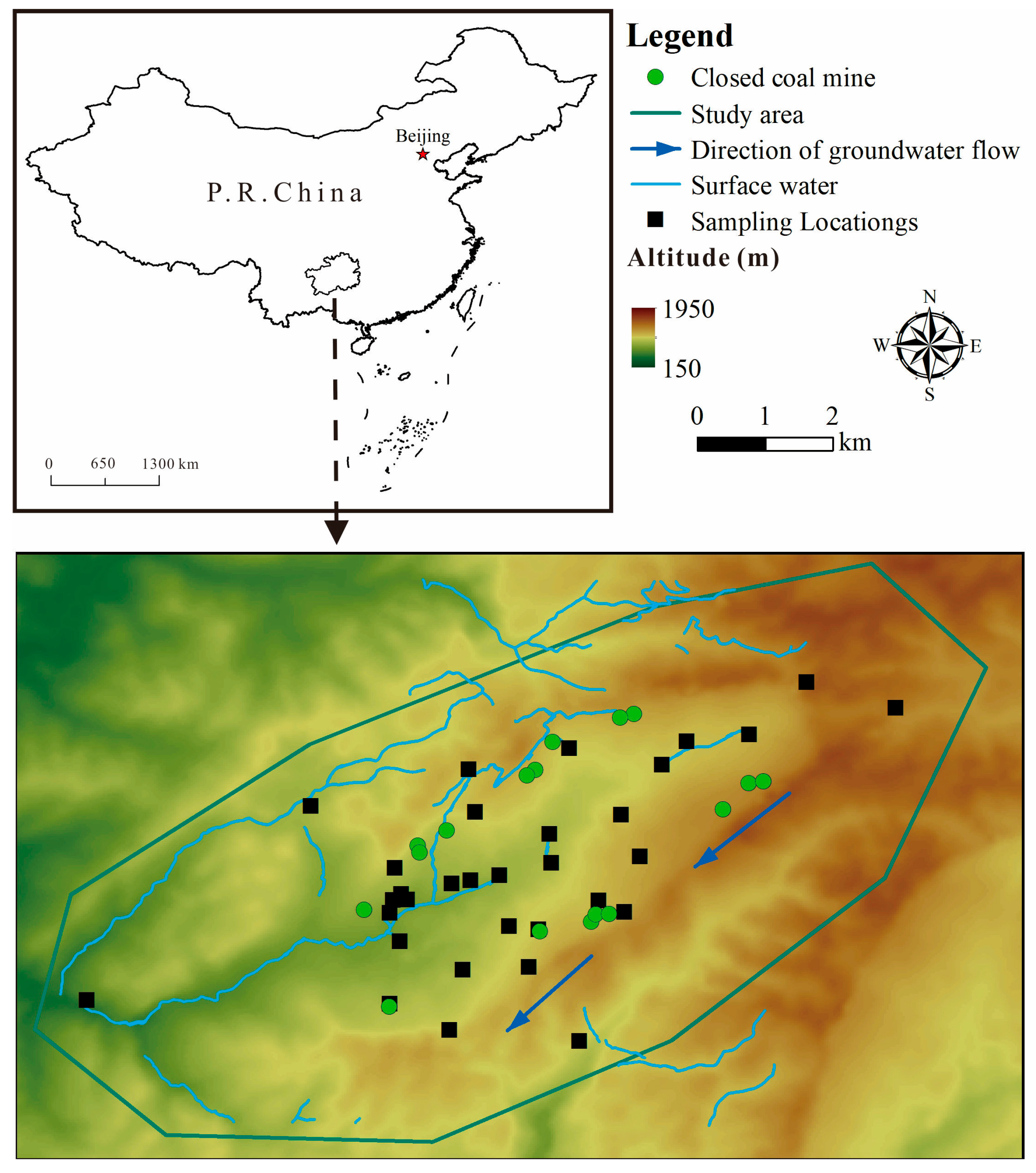

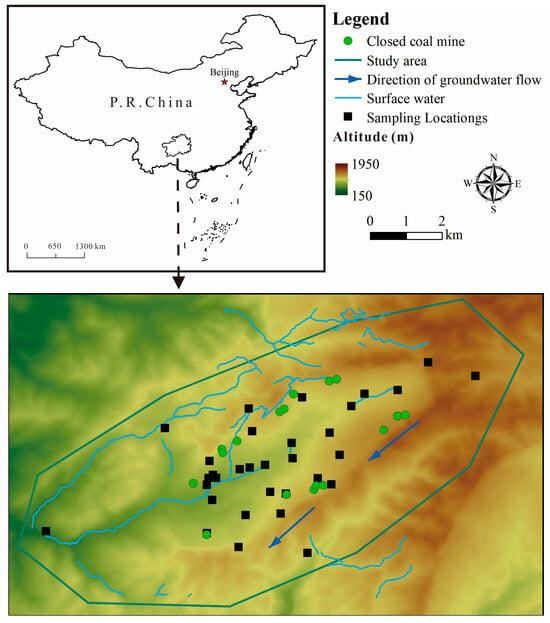

Figure 1.

The distribution of sampling points.

The study area falls within the Cwa zone (temperate, dry winter, and hot summer) of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification system. This classification is derived from the high-resolution Köppen–Geiger climate maps (Version 2) [32]. We specifically used the dataset for the 1991—2020 historical baseline period at a 0.5° spatial resolution (approximately 56 km). According to data from the World Meteorological Organization (climatological information based on the 30-year monthly averages from 1971 to 2000), the highest daily average maximum temperature occurs in August at 30.1 °C, and the highest monthly average precipitation occurs in June at 199.4 mm [33].

2.2. Geology and Hydrogeology

The on-site investigation revealed that the oldest stratum in study area is the Permian System; strata mainly consist of limestone. The Triassic System is mainly composed of limestone, sandstone, mudstone and dolomite. The study area contains small perennial streams with low discharge, flowing from northeast to southwest. A river traverses the central part of the study area, where the valley banks are predominantly composed of limestone. This river receives inflows from gullies and springs along its course, stretching 2400 m within the study area and following a westbound flow path along the low-lying synclinal axis. Long-term monitoring data indicate an average discharge of approximately 330 L/s for this river, with a water chemistry type classified as ——Ca2+.

Based on regional geological and coal mine data, the coal-bearing strata in the study area belong to the Upper Permian Longtan Formation (P3l), with the main minable coal seam occurring at a burial depth of approximately 50–200 m. The underlying strata are Middle Permian Maokou Formation (P2m) limestone, and the overlying strata are Upper Permian Changxing Formation (P3c) limestone, both of which are regionally significant karst aquifers. The Longtan Formation itself is dominated by clastic rocks, acting as a relative aquitard to separate the upper and lower aquifers under natural conditions. However, mining activities can compromise its integrity, inducing fractures that thereby form a hydraulic connection conduit linking the goaf to the aquifers [34,35].

The following hydrogeological characterization is based on a comprehensive field investigation conducted for this study, including geological mapping and analysis of regional hydrogeological survey reports. It is primarily recharged by atmospheric precipitation concentrated between April and October [33]. The recharge mechanisms and intensity are jointly controlled by the lithology, geomorphology, and geological structure. Groundwater dynamics exhibit significant seasonal variations [36], with discharge occurring mainly through concentrated karst springs downstream. Based on regional hydrogeological characteristics, the aquifer system consists predominantly of limestone, with groundwater occurring in dissolution cavities, pores, fissures, and karst conduits [37].

2.3. Coal Mine Factors

According to historical investigations, small-scale coal mining in the study area began predominantly in the 1980s. Most of these mines were distributed near coal seam outcrops, characterized by small production scales and substantial water accumulation in the mining tunnels. To date, all such mines have been closed.

2.4. Selection of Sampling Locations

The groundwater sampling sites were selected based on a combination of scientific and practical considerations to ensure the data were representative of the study area’s hydrogeochemical conditions. The selection criteria were as follows: (1) Points were distributed to cover the main groundwater flow paths, including presumed upstream (recharge) areas, within the mining-impacted zones, and downstream (discharge) areas near springs or rivers. (2) Samples were also collected from springs in nearby villages and agricultural lands to evaluate the potential spread of contaminants to areas of human activity. (3) A limited number of samples were taken from areas presumed to be upgradient or distant from mining activities to provide a local geochemical background reference.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Analysis

Groundwater sampling was conducted from 1–16 April 2024, yielding a total of 32 samples for analysis. All sampling procedures strictly adhered to the Chinese national standards “standard for groundwater quality” (GB/T 14848-2017) [38] and “Technical specifications for environmental monitoring of groundwater” (HJ 164-2020) [39]. The spatial distribution of the sampling points is illustrated in Figure 1. Following collection, samples were promptly transported to a possessing CMA certification for chemical analysis. According to the standard “Emission Standard for Pollutants from Coal Industry” (GB 20426-2006) [40], this study analyzed 9 characteristic coal mine pollutants, including iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), zinc (Zn), Fluoride, mercury (Hg), arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd), lead (Pb) and Sulfate.

Analyses were performed using standardized methods with specified instrumentation: Fe and Mn were determined by flame atomic absorption spectrophotometry (WFX-200 instrument, Beijing Beifen-Ruili Analytical Instrument (Group) Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) following “Water quality—Determination of iron and manganese-Flame atomic absorption spectrophotometric method” (GB 11911-89) [41]. Cd and Pb were analyzed using the same atomic absorption spectrophotometer, according to “Standard examination methods for drinking water-Part 6: Metal and metalloid indices” (GB/T 5750.6-2023) [42]. Hg and As were measured by atomic fluorescence spectrometry (AFS-230E instrument, Beijing Haiguang Instrument Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) per “Water Quality—Determination of Mercury, Arsenic, Selenium, Bismuth and Antimony—Atomic Fluorescence Spectrometry” (HJ 694-2014) [43]. Zn was quantified via atomic absorption spectrometry (WFX-200 instrument) “Water quality—Determination of copper, zinc, lead and cadmium—Atomic absorption spectrometry” (GB 7475-87) [44]. Sulfate was detected by barium chromate spectrophotometry (VIS-7220N instrument, Beijing Beifen-Ruili Analytical Instrument (Group) Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) as per “Water quality—Determination of sulfate-barium chromate spectrophotometry” (HJ/T 342-2007) [45]. The method detection limits for Fe, Mn, Zn, Fluoride, Hg, As, Cd, Pb and Sulfate were 0.03, 0.01, 0.05, 0.05, 0.04 × 10−3, 0.3 × 10−3, 0.5 × 10−3, 2.5 × 10−3 and 8 mg/L, respectively. For quality control, the standard deviation for all measured elements was maintained below 10%.

3.2. Evaluation Methodology

3.2.1. Spatial Distribution Analysis

The spatial distribution of CMCPs was constructed using the inverse distance weighting (IDW) interpolation technique within a Geographic Information System (GIS). This method estimates values at unsampled locations based on the principal of spatial proximity, assigning greater influence to known points that are closer to the prediction site [46,47]. IDW interpolation operates on the fundamental premise that an unknown value can be estimated from known neighboring points, with influence weighted inversely by distance. This distance decay effect ensures that the closest known point exerts the strongest influence, while the impact of farther points diminishes progressively; consequently, the method estimates values at unsampled locations by calculating a weighted average of nearby points [47,48].

3.2.2. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

We employed principal component analysis (PCA), a dimensionality reduction method, to simplify complex datasets. PCA derives a small number of principal components that capture most of the variance present in the original multiple variables, allowing for streamlined analysis without substantial information loss [49,50,51]. In their method, the authors noted that implementation in SPSS software enabled the analysis of inter-indicator correlations and the formation of linearly independent composite indicators from related variables [52].

3.2.3. Health Risk Assessment

The human body’s exposure to heavy metals in groundwater mainly occurs through oral intake and skin contact, and these two routes account for approximately 90% of the total intake of pollutants [51,53]. Scholars have indicated that human exposure to heavy metals and As is mainly occurring through oral intake and, to a lesser extent, through several other pathways, including dermal contact, inhalation and the food chain [26]. At the same time, given the observed use of some water bodies for irrigation or indirect use purposes, a conservative direct-ingestion scenario was adopted in this study to facilitate a precautionary risk assessment (i.e., the exposure level of residents to chemical components in water can be estimated solely based on their intake of drinking water). The health risk assessment model recommended by the standard “Technical guidelines for risk assessment of soil contamination of land for construction” (HJ 25.3-2019) [54] was used to evaluate the health risk of toxic substances (Cd, Pb, As and Fluoride) using the standard “Standards for drinking water quality” (GB 5749-2022) [55] in the groundwater of the study area. The Chemical-specific Groundwater Exposure Risk for Carcinogenic Effects (CGWERca) and Chemical-specific Groundwater Exposure Risk for Non-carcinogenic Effects (CGWERnc) are determined with Equation (1) and Equation (2), respectively.

In the formula, GWCRa is the daily groundwater consumption rate of adults (1.8 L/d); EFa is the exposure frequency of adults (250 d/a); EDa is the exposure duration of adults (25 a); BWa is the average body weight of adults (61.8 kg); ATca is the average time for carcinogenic effect (27,740 d); ATnc is the average time for non-carcinogenic effects (9125 d).

Health risks from groundwater contaminants are defined by two primary metrics: the non-carcinogenic Hazard Index (HI) and the carcinogenic Cancer Risk (CR). These are quantified by the following formulae:

where CR denotes carcinogenic health risks (mg/L); SFo denotes the Oral Ingestion Carcinogenic Slope Factor (Table 1); RfDo denotes the Oral Reference Dose (Table 1); WAF denotes the groundwater allocation factor (0.2).

Table 1.

SFo and RfDo of the CMCPs.

According to the standard “Technical guidelines for risk assessment of soil contamination of land for construction” (HJ 25.3-2019) [54] and referenced USEPA guidelines, the acceptable CR level for regulatory purposes ranges from 10−4 to 10−6. For non-carcinogenic risks, the HI exceeding 1 suggests potential adverse effects on human health [61].

The average population density was derived from the 2020 1 km gridded population dataset for China [62]. Using ArcGIS 10.8, the study area boundary was overlaid on the raster layer. The mean population count per grid cell within the boundary was calculated. This value, directly equivalent to persons per square kilometer (persons/km2), represents the area-weighted average density that accounts for the spatial heterogeneity of settlement, including uninhabited zones.

Field surveys confirm that water from these sources is utilized by the local community through a variety of means (e.g., springs) and serves as a primary source for agricultural irrigation. Consequently, contaminants detected in these groundwater systems present plausible contamination risks. Given this context, and in line with a precautionary screening approach, a health risk assessment based on a conservative direct-ingestion scenario is applied to evaluate the potential baseline risks.

3.2.4. Uncertainty Analysis

This study focused solely on the health risks posed by drinking water, and the assessed risk values may be underestimated compared to real-world scenarios. The risk assessment was conducted based on fixed health analysis parameters for adults, whereas actual conditions involve inherent parameter uncertainties rather than deterministic values. Additionally, the limited number of groundwater samples collected in this study may introduce some degree of randomness in the evaluation results. Although all sampling and analytical procedures strictly adhered to national standards, potential interference factors during sample collection and testing could still influence the measured outcomes. These uncertainties may affect the accuracy of the health risk assessment; however, they do not invalidate the findings.

3.2.5. Data Analysis

The relationship among CMCPs in groundwater was determined using the Pearson correlation and abundance heatmap by Origin Pro (version 2024). We interpreted the results as follows: p < 0.05 was taken to indicate a significant correlation, and p < 0.01 was interpreted as indicating a highly significant one. The PCA and standardization of original data were also performed by IBM SPSS version 22 [63]. Sampling points and groundwater quality were mapped using ArcGIS Desktop 10.8 [64].

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Concentration and Spatial Distribution Characteristics of CMCPs

In Table 2, Fe, Mn, Fluoride, Pb and Sulfate exceeded the limit values of Class III water in the “Standard for Groundwater Quality” (GB 14848-2017) [38]. The maximum Mn concentration detected in groundwater was 0.46 mg/L. This value exceeds the Class III water in the “Standard for Groundwater Quality” (GB 14848-2017) (0.1 mg/L) and the WHO permissible limit (0.08 mg/L), with max exceedance factors of 3.6 and 4.75, respectively. The maximum concentration of Fluoride detected in groundwater was 2.51 mg/L, exceeding the Class III limit (1.0 mg/L) of GB/T 14848-2017 and the WHO permissible limit (1.5 mg/L), with max exceedance factors of 1.51 and 0.67, respectively. However, it did not surpass the standard set by the USEPA. The concentration of Pb in groundwater was 0.02, exceeding the standard values of the “Standard for Groundwater Quality” (GB 14848-2017) (0.01 mg/L), the WHO (0.01 mg/L), and also crossing the standard limit of the USEPA (0.015 mg/L), with max exceedance factors of 1.00, 1.00 and 0.33. The maximum concentrations of Fe and Sulfate in groundwater reached 0.49 mg/L and 556 mg/L, respectively. These values exceeded the Class III thresholds specified in GB/T 14848-2017, with max exceedance factors of 0.63 and 1.22. In contrast, the detected concentrations of Zn, Hg, As and Cd did not surpass any applicable standards or limits.

Table 2.

The content of CMCPs in groundwater.

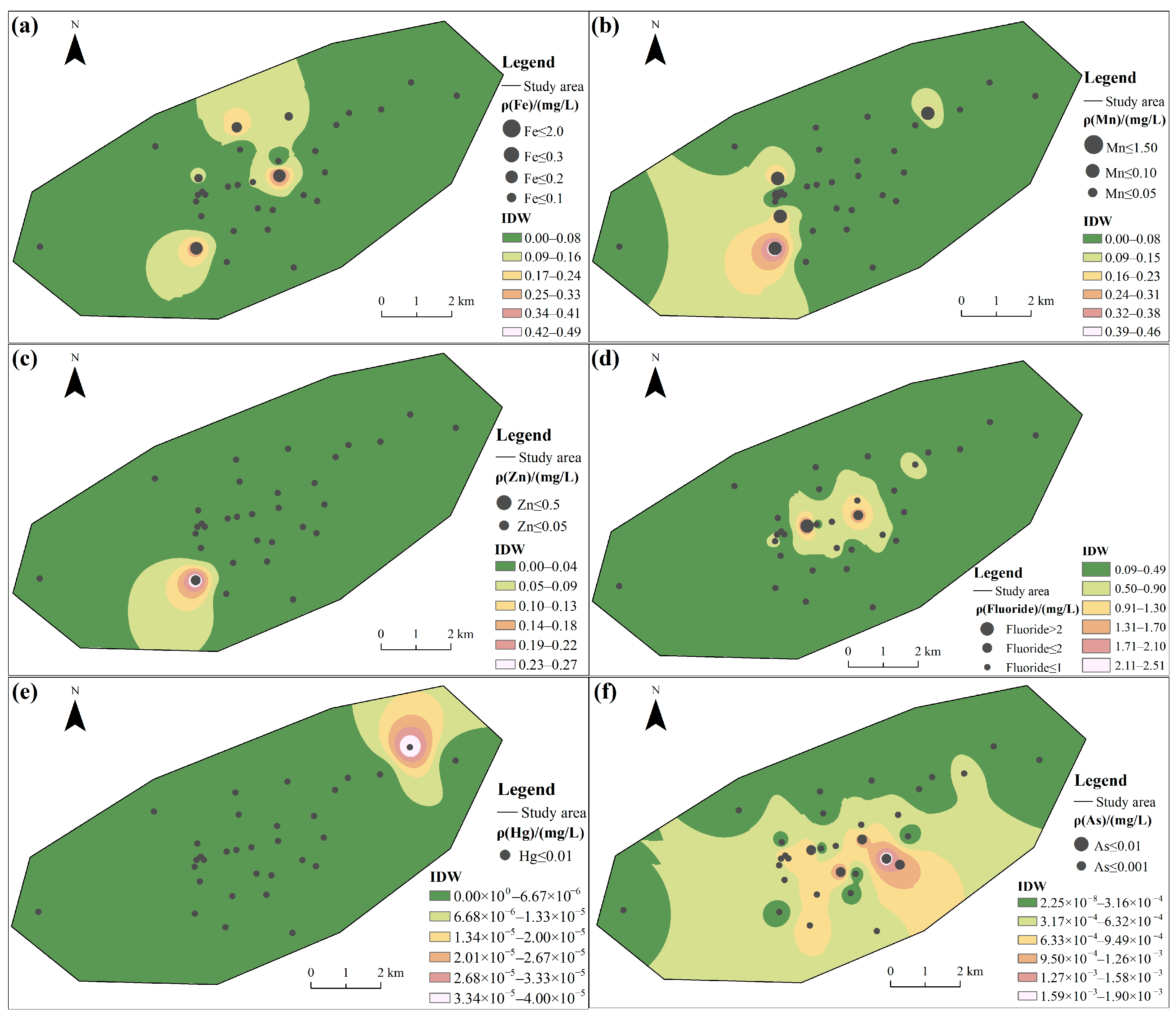

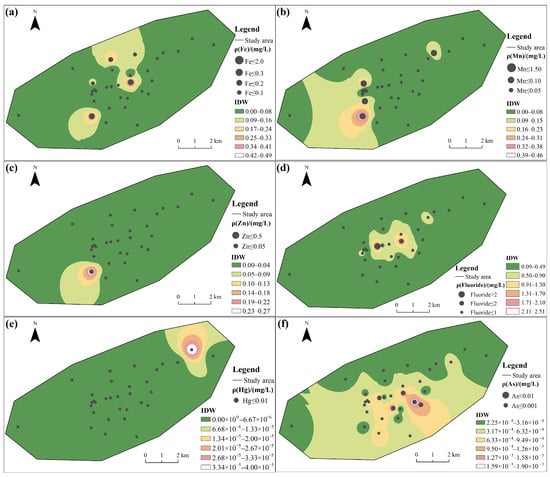

Among the tested CMCPs, the coefficient of variation (C.V.) exceeded 1.00 in the following order: Zn = Hg > Mn > Fe > Cd > Fluoride > Pb > As >1.00, indicating there is a certain variation in water quality among the groundwater samples [10]. The overall spatial distribution characteristics of the elements Mn and Zn (Figure 2b,c) are opposite to those of Cd, Pb, and Sulfate (Figure 2g–i), which show higher concentrations in the southwestern portions of the area. The spatial map also shows that discrete zones of high concentration for Fe were observed (Figure 2a); the central region shows a high concentration of Fluoride and As (Figure 2d,f).

Figure 2.

Spatial distribution of groundwater quality: (a) Fe, (b) Mn, (c) Zn, (d) Fluoride, (e) Hg, (f) As, (g) Cd, (h) Pb, and (i) Sulfate.

4.2. Source Apportionment of CMCPs

4.2.1. Correlation Analysis

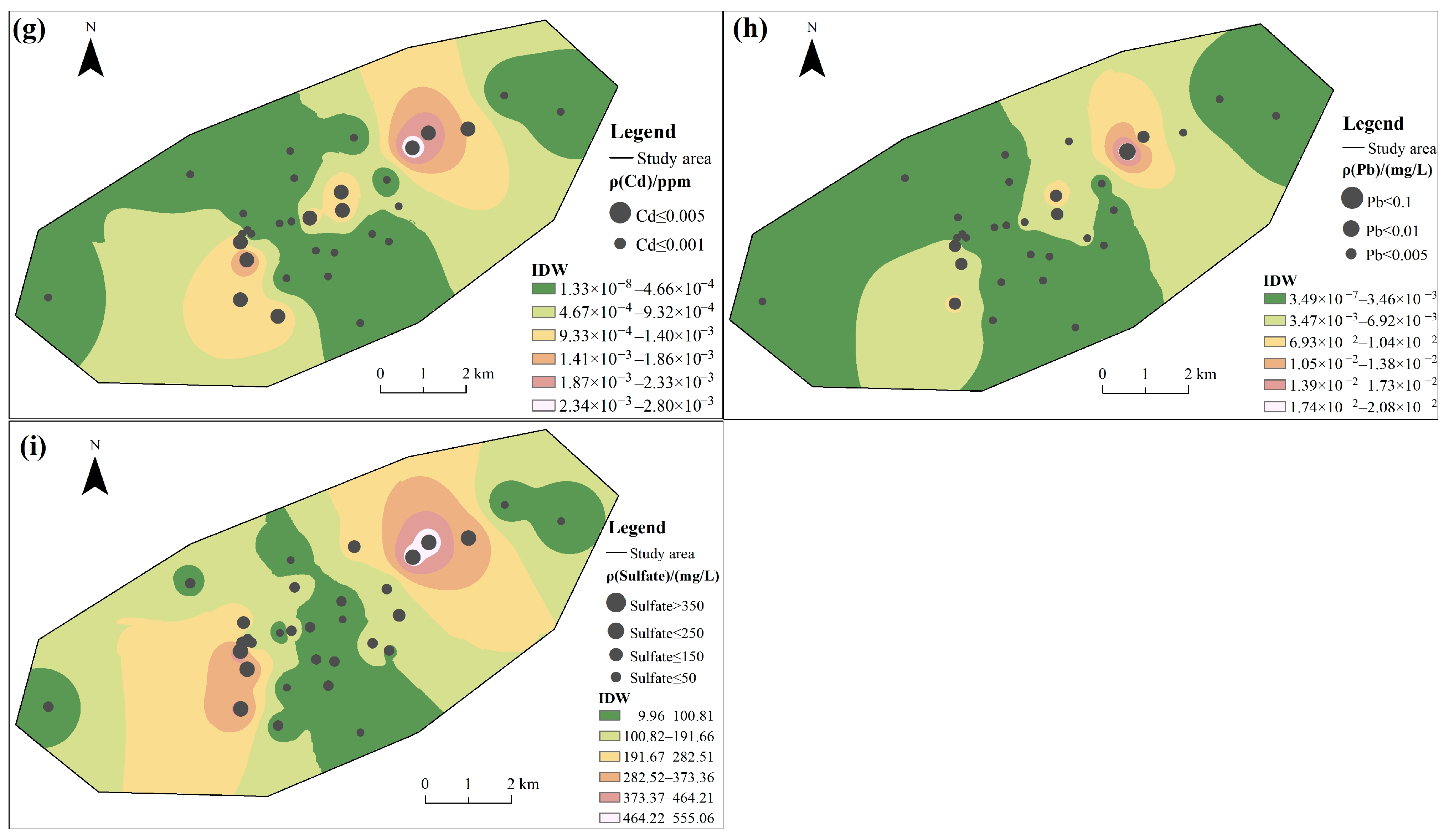

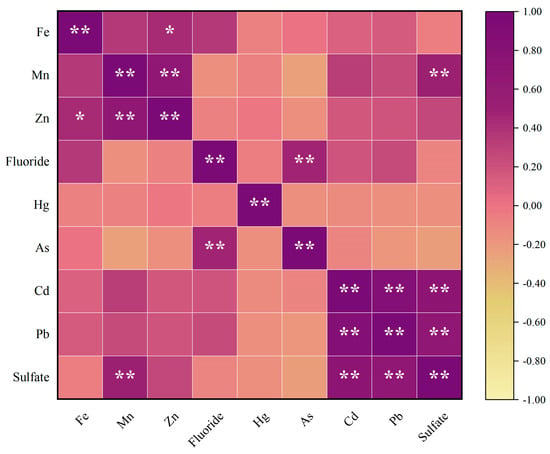

Figure 3 shows the Pearson correlation analysis results of groundwater. The results show that the correlation coefficients between Fe and Zn, indicating significant positive correlations between them (p < 0.05). The correlation coefficients between Mn and Zn, Mn and Sulfate, Fluoride and As, Cd and Pb, Cd and Sulfate and Pb and Sulfate indicate significant strong positive correlations between them (p < 0.01).

Figure 3.

Analysis results of groundwater correlation. * means p < 0.05, ** means p < 0.01.

4.2.2. PCA-Based Source Apportionment

The standardized data were deemed suitable for PCA, as supported by factorability tests. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure yielded a value of 0.62 (exceeding the 0.50 threshold), and Bartlett’s test of sphericity reached significance (p < 0.001). PCA extracted three significant principal components (eigenvalues > 1), which cumulatively capture 71.065% of the total dataset variance (Table 3). The first component (PC1), explaining 34.470% of the variance, showed high loadings for Cd, Pb, and Sulfate. Subsequently, PC2 (19.253%) was characterized by Zn, Mn, and Fe, and PC3 (17.342%) by Fluoride and As.

Table 3.

Rotating load matrix.

According to Table 3, PC1 exhibits high loadings for Cd, Pb, and Sulfate, primarily reflecting their contamination characteristics. The results in Figure 3 indicate significant positive correlations (p < 0.01) between Cd and Pb as well as Sulfate, suggesting that they may share similar sources. Cheng et al. indicates that the damage to underground aquifers during coal mining results in cross-layer pollution between aquifers at different depths, and the high concentration of Na+ and in the deep aquifer migrates to the shallow aquifer through fractured geological structures, thereby polluting the shallow groundwater source [10]. Kim et al. identified in six metalliferous mines and one coal mine in South Korea, which has been shown to be the most reliable indicator of the mining impact on groundwater [67]. Bhuiyan et al. found that the Pb concentration was comparatively higher, with 80% samples exceeding the Bangladesh (Govt.) maximum admissible limit standard for underground mine water, which may pose serious ecological and human health hazards [68]. Dheeraj et al. used the PCA method to study a coalfield region in India, showing large positive loadings of Cd, suggesting an association with nearby mining activities, thus aligning with our study [47]. The combined evidence indicates that PC1 likely originates from mining activities.

PC2 shows high loadings of Mn, Zn and Fe, indicating their contamination characteristics. Mining activities generate substantial quantities of waste rock containing sulfide minerals such as pyrite (FeS2) [69]. Bharat et al. observed that, in coal formations, iron is primarily hosted in sulfide minerals like pyrite (FeS2), chalcopyrite (CuFeS2), and arsenopyrite (AsFeS). Upon weathering, this increases iron and Sulfate environmental concentrations [70]. Zhou et al. considered that the natural weathering of sulfide minerals represented by pyrite was related to the Fe release process in abandoned coal mines [71]. Hao et al. found that seasonal variations in Mn contribute to the dynamic nature of geochemical processes [72]. This means that the natural geological process is dominated by Mn release from the weathering of carbonate rocks and Mn-rich mineral dissolution [72,73,74]. Mining activities can lead to elevated concentrations of trace elements (e.g., Mn, Ni, Si, and Sr) through the acidic leaching and release of these constituents from sulfide, silicate, and carbonate minerals within the strata [75]. Lin et al. previously published a study that found Zn and Fe showed a close correlation [76], similar to our study. Moreover, Lin et al. thought Zn could come from schistose rocks with sulfide seams [76]. Bharat et al. identified atmospheric dust, coal burning, and mining waste disposal as key anthropogenic contributors to Zn levels in aquatic systems. [70]. So, these results suggest that PC2 may represent both natural actions and anthropogenic sources.

PC3 exhibits high loadings on Fluoride and As, primarily reflecting their contamination characteristics. As indicated in Figure 3, there is a significant positive correlation between Fluoride and As. The arsenic and Fluoride ions affecting groundwater quality are primarily released from minerals such as arsenopyrite (FeAsS), fluorite (CaF2), and micas, which are hosted within the sedimentary and metamorphic rocks and coal seams of the region [77,78,79]. At the abandoned Kettara mine in Morocco, hydrogeological and geochemical investigations attributed the As contamination in groundwater to a geological origin (mafic rocks) rather than mining activities [80]. According to Rashid et al., “the Middle Jurassic strata are chiefly composed of sedimentary rocks, including limestone, shale, and sandstone. Notably, the presence of minerals like arsenopyrite and fluorite within these strata is a key contributor to aquifer contamination, introducing arsenic and fluoride, respectively” [79]. The main lithologies in this study were limestone and sandstone, similar to Rashid’s study. In the Mahendragarh district, Haryana, India, its high-Fluoride groundwater was likewise attributed to silicate weathering, highlighting the dominance of natural geochemical processes [81]. Wang et al. attributed the enrichment of arsenic and Fluoride in confined aquifers to organic matter degradation. They proposed that elevated temperatures exacerbate this release through a thermally driven process encompassing organic matter mineralization, arsenic desorption, and the dissolution of Fluoride-bearing minerals [82], which shows that PC3 likely originates from natural actions.

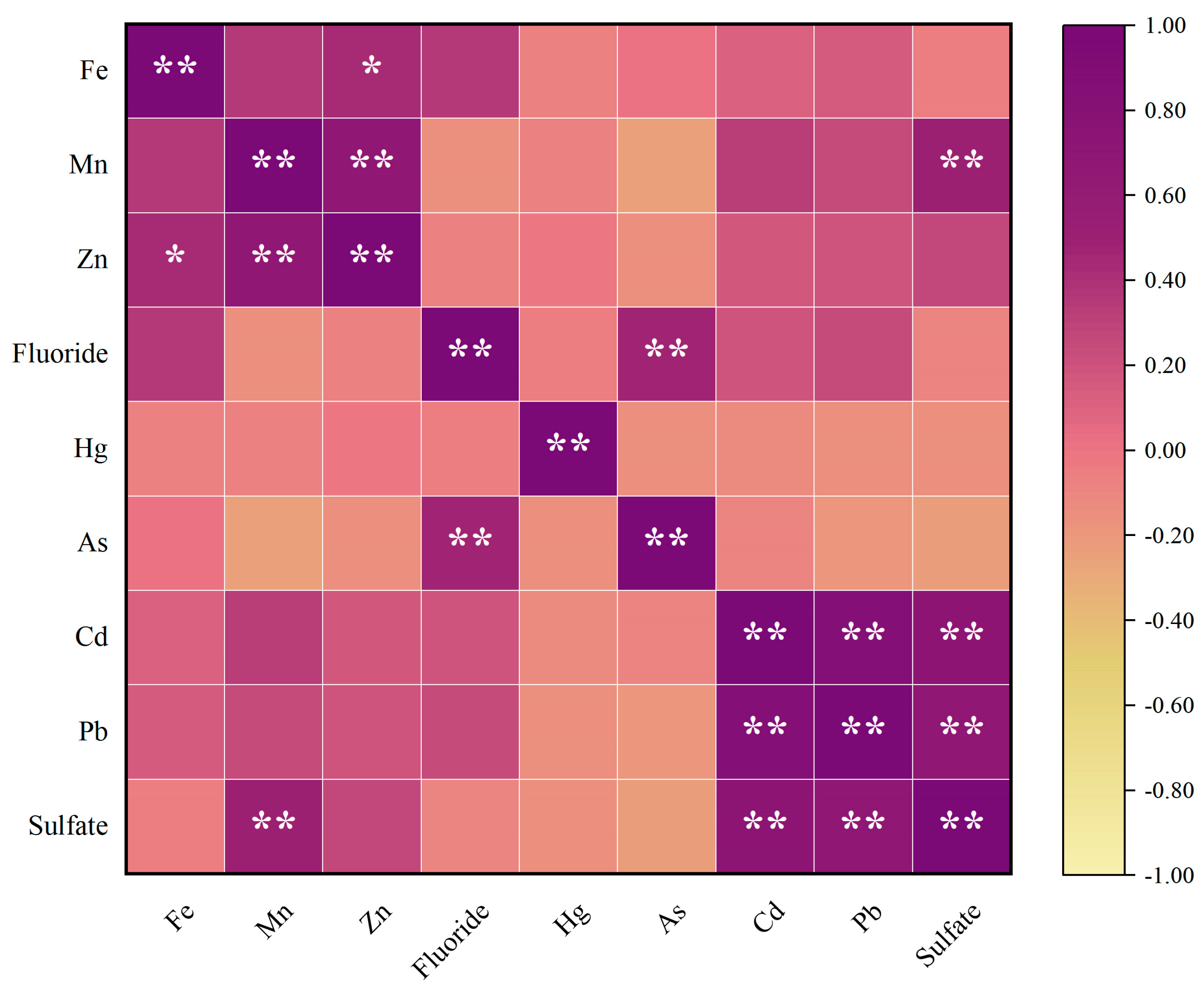

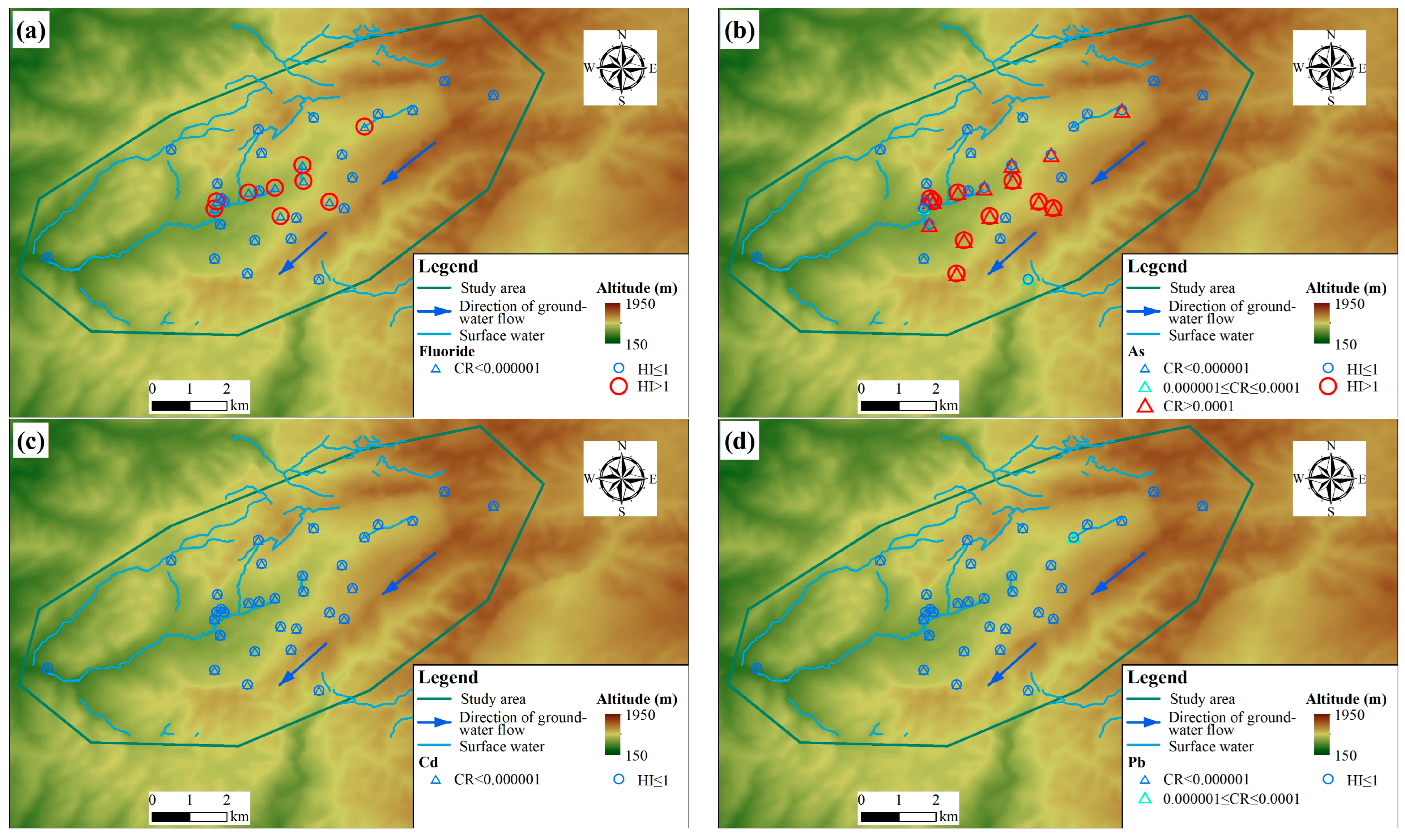

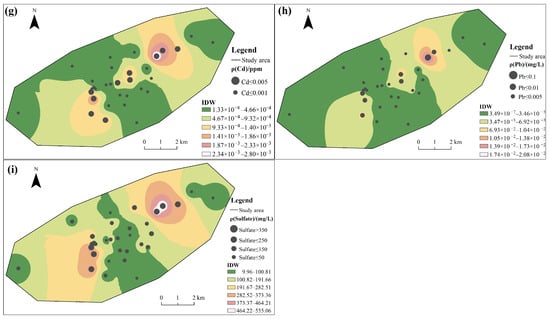

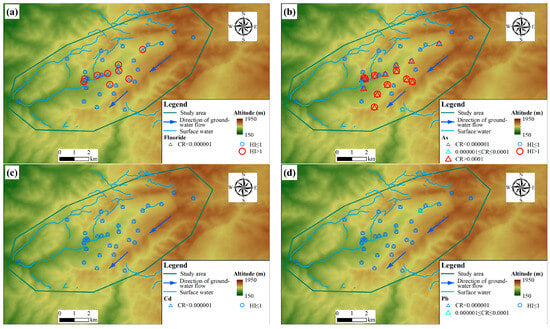

4.3. Water Quality Evaluation of Human Drinking Water Health

The average population density was derived from the 2020 1 km gridded population dataset for China, and the analysis yielded an average population density of 195.69 persons per square kilometer for the study area. This value reflects the rural character of the region, where settlements are dispersed amidst larger tracts of agricultural or natural land. Figure 4 shows the CR and HI statistical table. For cancer risks (CRs), according to the standard “Technical guidelines for risk assessment of soil contamination of land for construction” (HJ 25.3-2019) [54], and the reference USPEA standard, if the CR level in groundwater is between 10−4 and 10−6, we consider that there is no considerable risk regarding detrimental health effects. The Cd and Fluoride in the groundwater were negligible for adults (the absence of value) (Figure 4a,c). Additionally, CR values between 10−4 and 10−6 were observed at other points, including one sampling point associated with lead in the northeastern part (Figure 4d) and two sampling points associated with As in the central part (Figure 4b). However, As carcinogenic risk (CR greater than 10−4) was identified at 15 sampling points (Figure 4b), and the potential risks at these locations merit attention. These areas warrant priority consideration in monitoring and management strategies.

Figure 4.

Cancer Risk (CR) and Hazard Index (HI) health risk assessment results: (a) Fluoride, (b) As, (c) Cd, and (d) Pb.

Groundwater samples were assessed for non-carcinogenic health risks using the Hazard Index (HI), as per HJ 25.3-2019. HI values of less than 1 are interpreted as indicating no significant risk. Any exceedance of 1, however, is deemed to reflect a potential for adverse health effects and thus represents an unacceptable risk level. The results showed that the health risk assessment identified nine sampling points each for Fluoride and As with a HI greater than 1, indicating an unacceptable non-carcinogenic risk. For both elements, these high-risk points are predominantly concentrated in the central part of the study area (Figure 4a,b).

4.4. Synthesis of Key Findings

In summary, the integrated analysis of this karst coal mining basin reveals the following groundwater contamination profile:

(1) The concentrations of Fe, Mn, Fluoride, Pb, and Sulfate in the groundwater of the study area exceeded the Class III limits specified in China’s “Standard for Groundwater Quality” (GB/T 14848-2017), with maximum exceedance multiples of 0.63, 3.60, 1.51, 1.00, and 1.22 times the respective standards. The maximum concentrations exceeded WHO guidelines, with Mn, Fluoride, and Pb being higher by factors of 4.75, 0.67, and 1.00, respectively. Additionally, the Pb level exceeded the USEPA standard by a factor of 0.33. Analysis of the coefficient of variation (C.V.) indicated spatially heterogeneous distributions of Zn, Hg, Mn, Fe, Cd, Fluoride, Pb, and As. Elevated concentrations of Mn and Zn were observed in the southwestern part of the area, contrasting with the spatial pattern of Cd, Pb, and Sulfate, which showed higher levels in the northeast. Fe exhibited discrete high-concentration patches, while Fluoride and As had high contents in the central region.

(2) Correlation analysis revealed a highly significant positive relationship (p < 0.01) between Cd and Pb as well as Sulfate, suggesting their potential common origin. Principal component analysis (PCA) further supported this finding, with PC1 showing high loadings of Cd, Pb, and Sulfate, indicating that mining activities may serve as their predominant pollution source. Correlation analysis revealed a highly significant positive relationship (p < 0.01) between Mn and Zn, as well as the correlation coefficients between Fe and Zn, indicating significant positive correlations between them (p < 0.05). PC2 may therefore represent both natural actions and anthropogenic sources. A significant positive correlation (p < 0.05) was observed between Fluoride and As, and the PCA results indicated that PC3 was primarily loaded with Fluoride and As. This implies that natural geological processes may be the dominant source of these contaminants.

(3) Health risk assessment indicated As posed a carcinogenic risk (CR > 10−4) at 15 sampling points. This finding is consistent with the study by Liu et al. in an industrial hub, which also identified arsenic as a primary contributor to carcinogenic risk [83]. Fluoride and As resulted in a non-carcinogenic risk (HI > 1) at nine sampling points, indicating that there is a possibility for adverse effects on human health. Similarly, research at the abandoned Kettara mine in Morocco indicated that As in groundwater poses a potential threat to public health [80]. In the Mahendragarh district, Haryana, India, Fluoride exposure from groundwater also resulted in a high non-carcinogenic risk [81]. Therefore, for our study area, it is necessary to incorporate regular groundwater quality monitoring into the regional environmental management framework. These threats highlight that it is necessary to follow the evolution of As and Fluoride concentrations, as well as perform microbiological and clinical studies, which are an essential preventive measure.

5. Conclusions

The three PCA-derived sources collectively delineate a “triple-overlay” pollution framework that is likely characteristic of complex mining districts in vulnerable karst terrains. This framework synthesizes three concurrent and interactive processes: (i) direct anthropogenic injection from mining activities (PC1: Cd, Pb, and Sulfate), which is widely recognized as the primary impact; (ii) mining-enhanced geochemical leaching (PC2: Mn, Zn and Fe), wherein the natural weathering of minerals is accelerated by anthropogenic disturbances; and (iii) pristine geogenic release (PC3: Fluoride and As) from the local aquifer matrix, governed by natural water–rock interactions. The co-existence of these processes challenges the simplistic binary attribution of pollution to either “anthropogenic” or “natural” sources and provides a more nuanced conceptual model for environmental assessment in similar settings.

A critical and pragmatic insight from this study is the necessity to further study the health significance of geogenically sourced contaminants in mining-impacted areas. Although Fluoride and As (PC3) were attributed to natural geological processes, their associated health risks were found to be non-negligible. This underscores a key principle: a natural origin does not equate to an acceptable risk where sustained human exposure occurs. Consequently, water quality management strategies in such regions must expand beyond a sole focus on conventional industrial pollutants. Rigorous and long-term monitoring of inherent geogenic contaminants, informed by local geological knowledge, should be integrated into standard practice to ensure comprehensive public health protection.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/w18030351/s1, Table S1: Information on the sampled wells.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.F.; methodology, X.F. and C.Y.; software, Z.W. and B.H.; validation, H.G. and C.C.; formal analysis, H.G., L.J. and L.N.; investigation, C.Y., H.G. and X.F.; resources, X.F.; data curation, L.J., C.Y. and Z.T.; writing—original draft preparation, H.G. and C.Y.; writing—review and editing, X.F., H.G. and C.Y.; visualization, X.L. and C.Y.; supervision, X.F.; project administration, X.F.; funding acquisition, X.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Bonanza and Precision Mining, Guizhou Provincial Academician Expert Workstation (KXJZ [2024]003), Anhui University of Science and Technology’s high-level talent team launch funding project (YJ20250001), and the National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFC2902100).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jiang, C.; Gao, X.; Hou, B.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Li, C.; Wang, W. Occurrence and environmental impact of coal mine goaf water in karst areas in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 123813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lall, U.; Josset, L.; Russo, T. A snapshot of the world′s groundwater challenges. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2020, 45, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yuan, S.; Shi, J.; Ma, T.; Xie, X.; Deng, Y.; Du, Y.; Gan, Y.; Guo, Z.; Dong, Y.; et al. Groundwater Quality and Health: Making the Invisible Visible. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 5125–5136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X. Characterization of the health and irrigation risks and hydrochemical properties of groundwater: A case study of the Selian coal mine area, Ordos, Inner Mongolia. Appl. Water Sci. 2022, 12, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, W.; Li, W.; Zhang, S.; Niu, Y. Effects of coal mining on the evolution of groundwater hydrogeochemistry. Hydrogeol. J. 2019, 27, 2245–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, A.P.; Younger, P.L. Broadening the scope of mine water environmental impact assessment: A UK perspective. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2000, 20, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallioras, A.; Ruzinski, N. Special Issue: Sustainable Development of Energy, Water and Environment Systems. Water Resour. Manag. 2011, 25, 2917–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Johnson, K.L.; Younger, P.L. The co-treatment of sewage and mine waters in aerobic wetlands. Eng. Geol. 2006, 85, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Huang, L.; Zhang, S.; Han, X.; Xu, J.; Li, Y. Identification of groundwater hydrogeochemistry and the hydraulic connections of aquifers in a complex coal mine. J. Hydrol. 2024, 628, 130496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Yin, H.; Dong, F.; Li, Y.; Guo, Q.; Wang, Y. Hydrochemical characteristics, cross-layer pollution and environmental health risk of groundwater system in coal mine area: A case study of Jiangzhuang coal mine. Environ. Geochem. Health 2024, 46, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, M.A.H.; Islam, M.A.; Dampare, S.B.; Parvez, L.; Suzuki, S. Evaluation of hazardous metal pollution in irrigation and drinking water systems in the vicinity of a coal mine area of northwestern Bangladesh. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 179, 1065–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, G.V.; Ghosh, P.K. Systematic review on groundwater quality and its controlling mechanisms in coal mining regions: Health risk assessment and strategies for sustainability. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Fan, L.; Xia, Y.; Li, C.; Chen, J.; Gao, S.; Wu, B.; Peng, J.; Ji, Y. Impact of coal mining on groundwater of Luohe Formation in Binchang mining area. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2021, 8, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Torres, M.; Paudel, P.; Hu, L.; Yang, G.; Chu, X. Assessing the Karst Groundwater Quality and Hydrogeochemical Characteristics of a Prominent Dolomite Aquifer in Guizhou, China. Water 2020, 12, 2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Lu, C.; Zhao, D.; Li, J.; Zhu, H.; Dong, F. Hydrochemical Evolution of Karst Groundwater and Mining-Induced Activation Effects in a Coal Mining Area: A Case Study from the Tengxian Coalfield, China. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 42548–42560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Yang, G.; Zhu, D.; Xie, H.; Zhao, Y.; Fan, L.; Zou, S. Hydrogeochemistry of karst groundwater for the environmental and health risk assessment: The case of the suburban area of Chongqing (Southwest China). Geochemistry 2022, 82, 125866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.; Meng, S.; Cui, X.; Fei, Y. Hydrochemical characteristics and evolution processes of karst groundwater in Pingyin karst groundwater system, North China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2023, 82, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Tripathy, B.; Kumar, M.S.; Das, A.P. Ecotoxicological consequences of manganese mining pollutants and their biological remediation. Environ. Chem. Ecotoxicol. 2023, 5, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedron, T.; Cristine Augusto, C.; Carvalho Silva, G.; Cezar Valeriano, M.; Benicia Mamián-López, M.; Slaveykova, V.I.; Lemos Batista, B. Human health risk assessment and concentration of Al, Mn, Fe, Cu, Zn, Se, As, Cd, Pb, Hg, Rb, and REEs in chocolate. Food. Chem. Toxicol. 2025, 206, 115770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, H.; Gupta, A.K.; Tripathy, S. Fluoride and human health: Systematic appraisal of sources, exposures, metabolism, and toxicity. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 50, 1116–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karar, K.; Gupta, A.K.; Kumar, A.; Biswas, A.K. Characterization and Identification of the Sources of Chromium, Zinc, Lead, Cadmium, Nickel, Manganese and Iron in Pm10 Particulates at the Two Sites of Kolkata, India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2006, 120, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Q.; Hu, Y.; Liu, Q. Hydrogeochemical impacts of coal mining on multi-aquifer systems: A case study in the Linhuan Mining District, China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 308, 119492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burri, N.M.; Weatherl, R.; Moeck, C.; Schirmer, M. A review of threats to groundwater quality in the anthropocene. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 684, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Hu, Y.; Gao, H.; Su, Q. Dynamic identification and radium—Radon response mechanism of floor mixed water source in high ground temperature coal mine. J. Hydrol. 2021, 603, 126942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.; Han, D.; Song, X.; Liu, S. Environmental isotopes (δ18O, δ2H, 222Rn) and hydrochemical evidence for understanding rainfall-surface water-groundwater transformations in a polluted karst area. J. Hydrol. 2021, 592, 125748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, H.; Hao, X.; Wu, P.; Li, X.; Han, Z.; Cao, X.; Yang, B.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, K.; Chen, M.; et al. Different hydrogeological characteristics of springs associated with abandoned coal mines in well-developed karst area. J. Hydrol. 2025, 653, 132683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Li, B.; Liu, G. Groundwater risk assessment of abandoned mines based on pressure-state-response—The example of an abandoned mine in southwest China. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 10728–10740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jia, B.; Yang, F.; Huang, Q.; Peng, Q.; Wu, R.; Xie, Z. Anthropogenic coal mining reducing groundwater storage in the Yellow River Basin. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 958, 178120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, H.; Dong, W.; Chen, H.; Wang, R. Groundwater vulnerability assessment of typical covered karst areas in northern China based on an improved COPK method. J. Hydrol. 2023, 624, 129904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xin, C.; Yu, S. A Review of Heavy Metal Migration and Its Influencing Factors in Karst Groundwater, Northern and Southern China. Water 2023, 15, 3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ya, L.; Zhang, R.; Xue, X.; Liu, M.; Wang, J.; Lou, J. Research on karst landform classification based on positive and negative terrainsTaking the karst region of Guizhou Province as an example. J. Guizhou Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2024, 42, 9–19. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Beck, H.E.; McVicar, T.R.; Vergopolan, N.; Berg, A.; Lutsko, N.J.; Dufour, A.; Zeng, Z.; Jiang, X.; van Dijk, A.I.J.M.; Miralles, D.G. High-resolution (1 km) Köppen-Geiger maps for 1901–2099 based on constrained CMIP6 projections. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Meteorological Organization (WMO). Climatological Information for Zunyi. Available online: https://worldweather.wmo.int/zh/city.html?cityId=1874 (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Xu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, H.; Wang, K.; Geng, Y.; Chen, J. Physical Simulation of Strata Failure and Its Impact on Overlying Unconsolidated Aquifer at Various Mining Depths. Water 2018, 10, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Zhang, J.; Li, M.; Zhou, N. Experimental evaluation of physical, mechanical, and permeability parameters of key aquiclude strata in a typical mining area of China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 267, 122109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, K.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Xue, P.; Li, J.; Han, D.; Yu, L. Research on Groundwater Drought Characteristics in Guizhou Province Based on GRACE Data. J. China Hydrol. 2025, 1–10. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, J.; He, C.; Jia, Z.; Zhu, L.; Yi, Y.; Gong, J. Research progress on the water-carbon coupling processes at different scales in karst regions. Carsologica Sin. 2025, 44, 261–273. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 14848-2017; Standard for Groundwater Quality; General Administration of Quality Supervision. Inspection and Quarantine of the People′s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2017.

- HJ 164-2020; Technical Specifications for Environmental Monitoring of Groundwater. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People′s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2020.

- GB 20426-2006; Emission Standard for Pollutants from Coal Industry. State Environmental Protection Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2006.

- GB 11911-89; Water Quality-Determination of Iron and Manganese-Flame Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometric Method. State Environmental Protection Administration of China: Beijing, China, 1989.

- GB/T 5750.6-2023; Standard Examination Methods for Drinking Water-Part 6: Metal and Metalloid Indices. State Administration for Market Regulation: Beijing, China, 2023.

- HJ 694-2014; Water Quality—Determination of Mercury, Arsenic, Selenium, Bismuth and Antimony—Atomic Fluorescence Spectrometry. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2014.

- GB 7475-87; Water Quality—Determination of Copper, Zinc, Lead and Cadmium—Atomlc Absorption Spectrometry. State Environmental Protection Administration of China: Beijing, China, 1987.

- HJ/T 342-2007; Water Quality-Determination of Sulfate-Barium Chromate Spectrophotometry. State Environmental Protection Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2007.

- Choudhury, T.R.; Ferdous, J.; Haque, M.M.; Rahman, M.M.; Quraishi, S.B.; Rahman, M.S. Assessment of heavy metals and radionuclides in groundwater and associated human health risk appraisal in the vicinity of Rooppur nuclear power plant, Bangladesh. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2022, 251, 104072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dheeraj, V.P.; Singh, C.S.; Sonkar, A.K.; Kishore, N. Heavy metal pollution indices estimation and principal component analysis to evaluate the groundwater quality for drinking purposes in coalfield region, India. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2024, 10, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.G.; Diganta, M.T.M.; Sajib, A.M.; Hasan, M.A.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Rahman, A.; Olbert, A.I.; Moniruzzaman, M. Assessment of hydrogeochemistry in groundwater using water quality index model and indices approaches. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.C.; Alves, M.M.; Ferreira, E.C. Principal component analysis and quantitative image analysis to predict effects of toxics in anaerobic granular sludge. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 1180–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.; Liang, X.; Liao, F.; Mao, H.; Xiao, B.; Duan, L.; Shi, Z.; Wang, G.; Yu, R. Geochemical fingerprint and spatial pattern of mine water quality in the Shaanxi-Inner Mongolia Coal Mine Base, Northwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 854, 158812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Wei, Q.; Li, X.; Song, X.; Gao, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhang, R.; Wang, M. Heavy Metal Content Characteristics and Pollution Source Analysis of Shallow Groundwater in Tengzhou Coal Mining Area. Water 2023, 15, 4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, R.W.; Yan, Y.T.; Wei, C.L.; Luo, M.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, Y.H. Hydrochemical Characteristics and Groundwater Quality Assessment Using an Integrated Approach of the PCA, SOM, and Fuzzy c-Means Clustering: A Case Study in the Northern Sichuan Basin. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 907872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, S.; Singh, A.K. Risk assessment, statistical source identification and seasonal fluctuation of dissolved metals in the Subarnarekha River, India. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 265, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HJ 25.3-2019; Technical Guidelines for Risk Assessment of Soil Contamination of Land for Construction. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People′s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2019.

- GB 5749-2022; Standards for Drinking Water Quality. State Administration for Market Regulation: Beijing, China, 2022.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Cadmium CASRN 7440-43-9|DTXSID1023940. Available online: https://iris.epa.gov/ChemicalLanding/&substance_nmbr=141 (accessed on 13 January 2026).

- Nag, R.; Cummins, E. Human health risk assessment of lead (Pb) through the environmental-food pathway. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 810, 151168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, D.; Zhang, W.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, X.; Zou, C. Health risk assessment of heavy metals (Zn, Cu, Cd, Pb, As and Cr) in wheat grain receiving repeated Zn fertilizers. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 257, 113581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Arsenic, Inorganic CASRN 7440-38-2|DTXSID4023886. Available online: https://iris.epa.gov/ChemicalLanding/&substance_nmbr=278 (accessed on 13 January 2026).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Regional Screening Levels (RSLs)—Generic Tables. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/risk/regional-screening-levels-rsls-generic-tables (accessed on 13 January 2026).

- Abedi Sarvestani, R.; Aghasi, M. Health risk assessment of heavy metals exposure (lead, cadmium, and copper) through drinking water consumption in Kerman city, Iran. Environ. Earth Sci. 2019, 78, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X. Resource and Environmental Science Data Registration and Publishing System. China Population Spatial Distribution Kilometer Grid Dataset. 2017. Available online: https://www.resdc.cn/DOI/doi.aspx?DOIid=32 (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Wen, X.; Lu, J.; Wu, J.; Lin, Y.; Luo, Y. Influence of coastal groundwater salinization on the distribution and risks of heavy metals. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 652, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ababakr, F.A.; Ahmed, K.O.; Amini, A.; Moghadam, M.K.; Gökçekuş, H. Spatio-temporal variations of groundwater quality index using geostatistical methods and GIS. Appl. Water Sci. 2023, 13, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality: Fourth Edition Incorporating the First and Second Addenda; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 978-92-4-004506-4. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. National Primary Drinking Water Standards. Available online: https://permanent.access.gpo.gov/websites/epagov/www.epa.gov/OGWDW/mcl.html#7 (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Kim, D.; Yun, S.; Cho, Y.; Hong, J.; Batsaikhan, B.; Oh, J. Hydrochemical assessment of environmental status of surface and ground water in mine areas in South Korea: Emphasis on geochemical behaviors of metals and sulfate in ground water. J. Geochem. Explor. 2017, 183, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, M.A.H.; Bodrud-Doza, M.; Rakib, M.A.; Saha, B.B.; Islam, S.M.D. Appraisal of pollution scenario, sources and public health risk of harmful metals in mine water of Barapukuria coal mine industry in Bangladesh. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 22105–22122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Tang, C.; Wu, P.; Strosnider, W.H.J.; Han, Z. Hydrogeochemical characteristics of streams with and without acid mine drainage impacts: A paired catchment study in karst geology, SW China. J. Hydrol. 2013, 504, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharat, A.P.; Singh, A.K.; Mahato, M.K. Heavy metal geochemistry and toxicity assessment of water environment from Ib valley coalfield, India: Implications to contaminant source apportionment and human health risks. Chemosphere 2024, 352, 141452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, X.; Xu, D.; Zheng, S. The pollution characteristics and causes of dual sources—Iron (Fe) in abandoned coal mines: A literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 471, 143358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Hao, H.; Bu, C.; Long, E.; Wang, H.; Wu, P.; Li, X. Temporal and spatial distribution, sources and health risk assessment of trace elements in a typical karst river basin in Southwest China: Influence of acid mine drainage from abandoned coal mines. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2026, 309, 119524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Du, J.; Jia, C.; Yang, T.; Shao, S. Unravelling integrated groundwater management in pollution-prone agricultural cities: A synergistic approach combining probabilistic risk, source apportionment and artificial intelligence. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 481, 136514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wu, Q.; Gao, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Wu, P.; Zeng, J. Coupled controls of the infiltration of rivers, urban activities and carbonate on trace elements in a karst groundwater system from Guiyang, Southwest China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 249, 114424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Gao, X. Hydrochemistry and coal mining activity induced karst water quality degradation in the Niangziguan karst water system, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 6286–6299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M.; Peng, W.; Gui, H. Heavy metals in deep groundwater within coal mining area, northern Anhui province, China: Concentration, relationship, and source apportionment. Arab. J. Geosci. 2016, 9, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Farooqi, A.; Gao, X.; Zahir, S.; Noor, S.; Khattak, J.A. Geochemical modeling, source apportionment, health risk exposure and control of higher fluoride in groundwater of sub-district Dargai, Pakistan. Chemosphere 2020, 243, 125409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Ayub, M.; Bundschuh, J.; Gao, X.; Ullah, Z.; Ali, L.; Li, C.; Ahmad, A.; Khan, S.; Rinklebe, J.; et al. Geochemical control, water quality indexing, source distribution, and potential health risk of fluoride and arsenic in groundwater: Occurrence, sources apportionment, and positive matrix factorization model. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 460, 132443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashid, A.; Ayub, M.; Gao, X.; Xu, Y.; Ullah, Z.; Zhu, Y.G.; Ali, L.; Li, C.; Ahmad, A.; Rinklebe, J.; et al. Unraveling the impact of high arsenic, fluoride and microbial population in community tubewell water around coal mines in a semiarid region: Insight from health hazards, and geographic information systems. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 480, 136064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyé, J.; Picard-Lesteven, T.; Zouhri, L.; El Amari, K.; Hibti, M.; Benkaddour, A. Groundwater assessment and environmental impact in the abandoned mine of Kettara (Morocco). Environ. Pollut. 2017, 231, 899–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambastha, S.K.; Haritash, A.K. Prevalence and risk analysis of fluoride in groundwater around sandstone mine in Haryana, India. Rend. Lincei. Sci. Fis. Nat. 2021, 32, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guo, H.; Adimalla, N.; Pei, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, H. Co-occurrence of arsenic and fluoride in groundwater of Guide basin in China: Genesis, mobility and enrichment mechanism. Environ. Res. 2024, 244, 117920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yi, B.; Liu, F.; Liu, C.; Yang, S.; Zhang, H.; Kang, W.; Jiang, K. Groundwater metal pollution and health risk assessment in river valley heavy industrial cities of arid regions in China. China Geol. 2025, 8, 526–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.