Abstract

Sulfur-based autotrophic denitrification (SAD) is limited by low efficiency and poor stability in carbon-deficient photovoltaic (PV) wastewater treatment. This study developed four sulfur-based composite fillers (S0-CFs) comprising 75% elemental sulfur and mineral additives (boron mud, magnesite, and/or siderite) fabricated via melt mixing–jet granulation. Lab-scale operation showed that at a hydraulic retention time (HRT) of 1 h, all S0-CFs achieved high TN removal (89.1–93.8%) with effluent NO3−-N below 1.5 mg/L (>93% nitrate removal efficiency) and stable pH. Although effluent COD increased with a short HRT (1 h) due to biofilm detachment, no leaching of organic or inorganic pollutants from the fillers was observed, and TP was consistently removed. 16S rRNA sequencing confirmed enrichment of autotrophic denitrifiers Thiobacillus and Sulfurimonas, verifying SAD as the dominant pathway. In a 270-day pilot-scale operation, nitrate removal varied with temperature (7.3–27.2 °C) and HRT, reaching 88.2% on average (range: 86.6–90.0%) at 1 h HRT during warm periods (25.8–27.2 °C), dropping to 13.5–38.1% under cold conditions (7.3–16.0 °C) at 0.5 h HRT, and then stabilizing at 64.1% by adjusting HRT to 1 h. Fluoride was removed at 0.51–1.49 mg/L. Additionally, operational cost was 34.5% lower than heterotrophic denitrification. These results demonstrated that S0-CF enabled efficient, stable, and cost-effective nitrogen removal, making SAD more suitable for low-carbon industrial wastewater treatment.

1. Introduction

The principle of sulfur-based autotrophic denitrification (SAD) is that the sulfur-autotrophic bacteria utilize elemental sulfur, sulfides, pyrite, and other reduced sulfur species as electron donors to reduce nitrate to N2 [1,2]. Compared with conventional heterotrophic denitrification, SAD eliminates the need for external organic carbon-source supplementation, thereby substantially reducing excess sludge production and operational costs; meanwhile, the emission of carbon dioxide (CO2) associated with the mineralization of organic matter is also avoided. Moreover, SAD generates minimal nitrous oxide (N2O)—a potent greenhouse gas—resulting in a significantly lower carbon footprint and overall greenhouse gas emissions [3,4]. These make SAD an efficient and low-carbon biological process for nitrogen removal from wastewater.

However, the SAD process using elemental sulfur (S0) as an electron donor, termed S0-AD, still faces several critical challenges in practical applications. The biological oxidation of S0 releases large quantities of protons (H+), often causing a sharp drop in pH that can inhibit microbial activity. Concurrently, sulfate (SO42−), the primary metabolic byproduct, continuously accumulates, potentially causing risks of secondary pollution. More prominently, pure S0 fillers have inherently poor mechanical strength, which are prone to disintegration and attrition under long-term hydraulic shear, thereby compromising long-term stability in fixed-bed reactors or constructed wetlands [5,6,7,8,9]. To address these limitations, researchers have developed composites of S0 with natural minerals. For instance, limestone is commonly incorporated to neutralize acidity and buffer pH fluctuations [6]; iron-bearing minerals, such as pyrite (FeS2), pyrrhotite (Fe1−nS), and siderite (FeCO3), could act as supplementary electron donors (via Fe2+ oxidation) to enhance denitrification kinetics and enable simultaneous phosphorus removal through Fe3+-phosphate precipitation [5,8,9]. Nevertheless, existing composites still suffer from notable drawbacks: limestone increases effluent hardness; iron-rich minerals can be costly; and most formulations fail to adequately resolve the persistent issues of SO42− accumulation and insufficient mechanical durability [7,10,11].

Boron mud, an alkaline industrial byproduct generated during boric acid or borax production, emerges as a promising candidate for an S0-based composite. With annual production exceeding one million tons in China, boron mud is primarily composed of MgO and SiO2, along with minor amounts of Fe2O3, CaO, Al2O3, and B2O3. Its disposal poses environmental concerns due to its high pH (~9), which can cause soil alkalization near stockpiles [12]. More importantly, these very properties offer functional benefits in SAD systems: firstly, MgO slowly hydrolyzes to release OH−, effectively counteracting acidification from S0 oxidation; secondly, Mg2+ can precipitate phosphate as struvite-like minerals, enabling concurrent nutrient removal; thirdly, trace elements, such as Fe, Mg, and B, may support microbial and plant growth in integrated treatment systems [13]. Critically, boron mud is abundant, low-cost, and its magnesium silicate-based matrix has the potential to significantly enhance the mechanical robustness of S0-based composites, which is a key bottleneck in current S0-AD applications.

In China, photovoltaic (PV) wastewater treatment plants commonly struggle with insufficient carbon availability, prolonged hydraulic retention times, and declining microbial metabolic activity during the biological nitrogen removal process, making it difficult to consistently meet the discharge limit of total nitrogen (TN) < 15 mg/L [14]. Although SAD is theoretically well-suited to address these challenges due to its characteristic of not relying on external organic carbon sources, studies specifically targeting PV wastewater treatment remains scarce [15]. Against this backdrop, the development of high-performance sulfur-based composite fillers suitable for this type of wastewater has become a key breakthrough for achieving efficient and stable nitrogen removal.

While recent studies have explored sulfur-based composites using natural minerals like limestone or pyrite, these approaches still rely on the extraction of raw resources and do not address the disposal of industrial solid wastes. This study distinguishes itself by valorizing boron mud—a hazardous alkaline industrial waste—as a functional component for SAD fillers. From the perspective of a circular economy, repurposing boron mud not only mitigates the environmental risks associated with its stockpiling (e.g., soil alkalization) but also replaces the cost of mining natural alkaline minerals [13]. This dual benefit of “waste control by waste” offers a sustainable solution that existing sulfur-based fillers do not provide.

Against this backdrop, this study aims to (1) synthesize and characterize novel S0-based composite fillers (S0-CF) incorporating boron mud, magnesite, and siderite, with a focus on their mechanical strength and pore structure; (2) evaluate their nitrogen removal performance and associated hydrochemical characteristics (e.g., SO42− production and pH variation) under varying HRTs; (3) elucidate the microbial community shifts and metabolic pathways using 16S rRNA sequencing and FAPROTAX analysis; and (4) validate the long-term feasibility and cost-effectiveness of the selected filler (S0-CF 4#) in a 270-day pilot-scale reactor treating real PV wastewater.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Composition and Preparation of S0-CF

Four types of S0-CF were obtained by blending sulfur with boron mud, magnesite powder, with/without siderite powder in certain proportions, followed by a granulation process. The compositions, expressed as weight percentages, are summarized as follows: S0-CF 1#: 75% sulfur, 15% magnesite powder and 10% boron mud; S0-CF 2#: 75% sulfur, 15% siderite powder and 10% boron mud; S0-CF 3#: 75% sulfur, 10% boron mud, 10% magnesite powder and 5% siderite powder; S0-CF 4#: 75% sulfur and 25% boron mud. Their bulk densities were 1.08, 1.12, 1.16, and 1.16 g/cm3, respectively. The specific mass ratios of sulfur to mineral additives were determined based on preliminary experiments, which aimed to balance the mechanical strength of the granules with their porosity and denitrification performance.

The S0-CFs were fabricated using a melt mixing–jet granulation process, with the following specific procedure: industrial-grade liquid sulfur (purity ≥ 99.0%) was heated to 120–135 °C for melting, and then mixed with 200-mesh mineral powders (siderite, magnesite, or boron mud) in the reaction vessel in proportion for 10–20 min to form a homogeneous slurry. The slurry was fed into a convergent-nozzle jet mixer with a 50% diameter reduction, where 1.5 times its volume of air (3.0–7.0 m3/h) was aspirated. Micron-sized bubbles were generated as the mixture passed through a conical diffusion chamber with a narrow front and wide rear structure. Subsequently, the bubble–slurry mixture was uniformly dispersed by a rotating disk distributor (30 r/min) and dripped into cooling water at 30–55 °C with a drop height of 50–400 mm for solidification. Finally, spherical porous S0-CFs with particle sizes of 3–10 mm were obtained.

2.2. Reactor and Operation

2.2.1. Lab-Scale Reactor and Operation

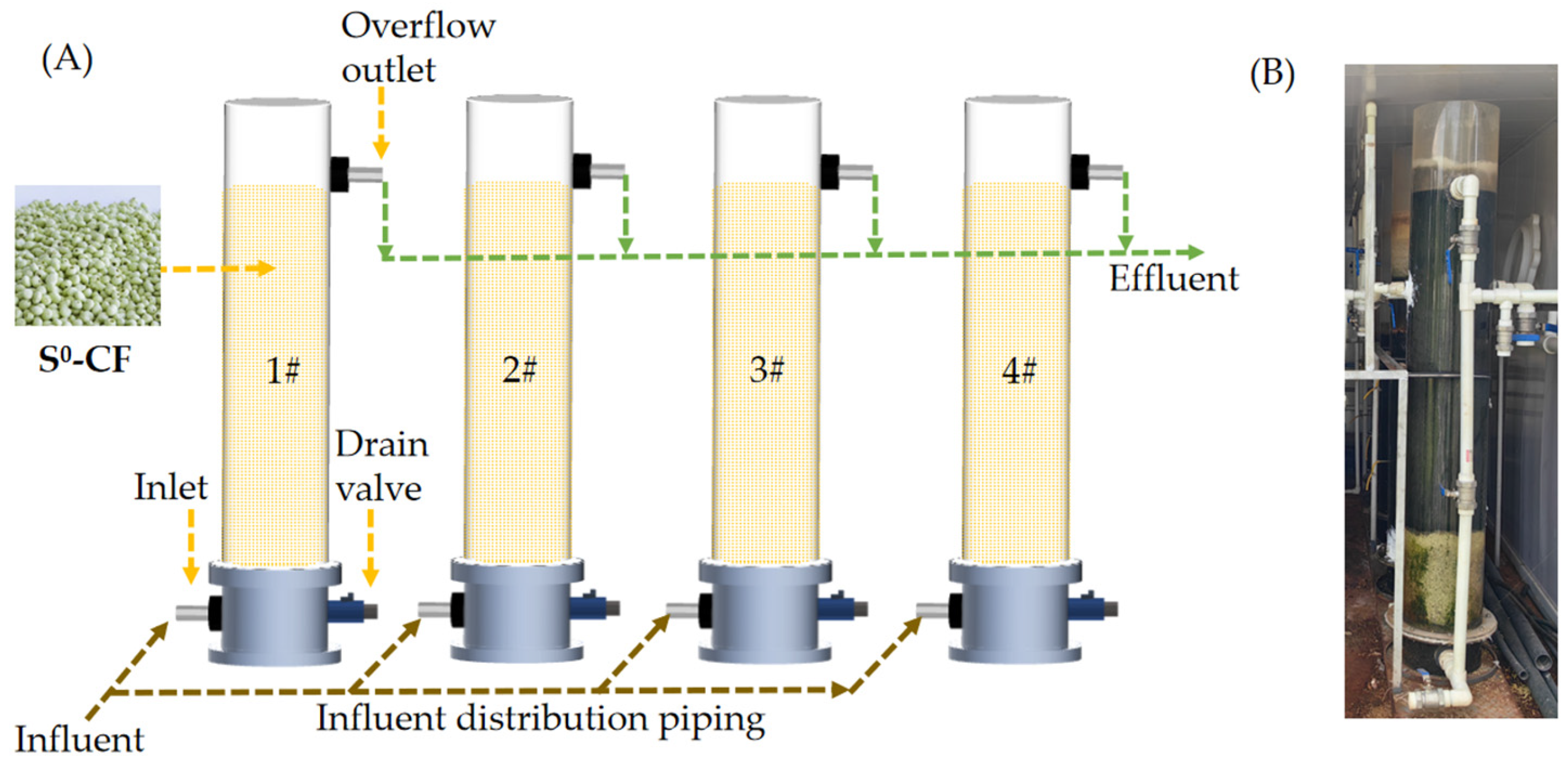

The reactor was made of acrylic glass, with a height of 80 cm and an inner diameter of 10 cm. The total and working volumes of the reactor were 25 L and 22 L, respectively. The above-mentioned 4 types of S0-CFs were added to 4 reactors separately and packed, with the same filling rate of 70%. The reactor was an upflow fixed-bed reactor (Figure 1A), the wastewater was introduced into the reactors via a peristaltic pump, and the temperature of each reactor was maintained at (25 ± 2) °C.

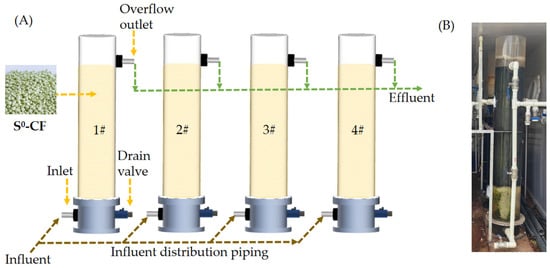

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic diagram of the lab-scale reactor, (B) photograph of the pilot-scale reactor.

The operation of each reactor could be divided into 3 phases. In Phase 1 (days 1–3), the inoculation sludge and nutrient solution were filled into each reactor in a volume ratio of 4:3. The nutrient solution was composed of 300 mg/L KNO3, 523 mg/L NaHCO3, 30 mg/L NH4Cl, and 522 mg/L KH2PO4. Backwashing was performed every 12 h to facilitate initial biofilm formation. In Phase 2 (days 4–10), a continuous low-flow feeding method was adopted with an influent flow rate of 1.25 mL/min, during which visible biofilms could be seen on the reactor wall and S0-CF surfaces, indicating that the biofilm formation start-up was completed. In Phase 3 (days 11–96), the HRT was stepwise reduced to progressively increase the influent nitrogen loading rate. The HRT sequence was set at 20, 16, 8, 4, 1, and 0.5 h. The system was operated for at least 10 days at each HRT level to ensure steady-state performance before moving to the next level.

2.2.2. Pilot-Scale Reactor and Operation

The pilot-scale reactor was also made of acrylic glass with a dimension of Ø30 cm × 200 cm. The total and working volumes of the reactor were 565 L and 480 L, respectively (Figure 1B). The S0-CF 4# was added to the reactor and packed, with a filling rate of 20%. The S0-CF 4# had a bulk density of 1.16 g/cm3, specific surface area of 1.01 m2/g, average pore diameter of 27.00 nm, and compressive strength of 1.35 MPa. The wastewater was introduced into the reactor via a lifting pump. Air–water combined backwashing was adopted every 24 h, with each cycle lasting 1 min. The backwashing air scouring rate was 45 m3/(m2·h) and the water flushing rate was 30 m3/(m2·h).

The operation of the pilot-scale reactor could also be divided into 3 phases. In Phase 1 (days 1–3), the reactor was filled with a mixture of inoculated sludge and photovoltaic wastewater at a volume ratio of 1:1. Backwashing was also performed every 12 h to promote initial biofilm attachment. In Phase 2 (days 4–14), a continuous low-flow feeding was applied at 20 L/h until a distinct biofilm could be seen on the reactor wall and the surface of the S0-CF to indicate successful start-up of the reactor. In Phase 3 (days 15–284), HRT was alternated between 1 and 0.5 h to evaluate the nitrogen removal performance under varying water temperatures (7.3–27.2 °C).

2.3. Inoculated Sludge and Influent

2.3.1. Inoculated Sludge and Influent of the Lab-Scale Reactor

Inoculated sludge was collected from the secondary sedimentation tank of a municipal wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) in Beijing, China. The reactor was fed with simulated wastewater prepared by dissolving analytical-grade reagents in deionized water. The influent composition was as follows: NO3−-N at 20 mg/L (supplied as KNO3, 144.43 mg/L), bicarbonate alkalinity (HCO3−) at 100 mg/L (as NaHCO3, 137.70 mg/L), Fe2+ at 9 mg/L (as FeSO4·7H2O, 44.68 mg/L), NH4+-N at 1 mg/L (as NH4Cl, 3.82 mg/L), Ca2+ at 5 mg/L (as CaCl2·2H2O, 18.38 mg/L), Mg2+ at 10 mg/L (as MgSO4·7H2O, 102.50 mg/L), and TP at 1 mg/L (as KH2PO4, 4.39 mg/L).

2.3.2. Inoculated Sludge and Influent of the Pilot-Scale Reactor

The pilot-scale study was carried out at a wastewater treatment plant located in a PV industrial park in northern China. The inoculated sludge was collected from the anoxic zone of this wastewater treatment plant, with a mixed liquor suspended solids (MLSS) of approximately 5400 mg/L. The influent was taken from the effluent of the coarse screen in this wastewater treatment plant. As detailed in Table 1, the coefficient of variation (CV) and median values were introduced to better characterize the fluctuation of influent water quality. Notably, the CV values for TP, NH4+-N, and NO3−-N were relatively high, reaching 69%, 44%, and 41%, respectively. This indicates that the influent quality fluctuated drastically rather than remaining steady around the mean, particularly for phosphorus and nitrogen species. Such high variability implies that the pilot-scale reactor was subjected to frequent shock loads during the operation. In contrast, the pH remained relatively stable with a low CV of 2%. These conditions imposed a stringent test on the system’s operational stability and adaptability to real-world industrial wastewater.

Table 1.

Composition and concentration of feed water of the pilot-scale reactor.

2.4. Analytical Methods

All water samples were filtered through a 0.45 μm filter membrane before the determination of water quality, including TN, NH4+-N, NO3−-N, NO2−-N, TP, and COD. For the determination of the SO42− concentration, samples were filtered through a 0.22 μm filter membrane. All analyses were performed in accordance with (APHA, 2002). The crystalline phases present in the S0-CFs were identified by X-ray diffraction (XRD) using a Rigaku SmartLab SE diffractometer (Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan), The specific surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution were determined by N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms at 77 K using a Micromeritics ASAP 2460 analyzer (Micromeritics, Norcross, GA, USA), with data analyzed according to the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) theory. The surface morphology and microbial colonization of the S0-CFs were examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using a ZEISS Sigma 360 field-emission scanning electron microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany), with samples sputter-coated with gold prior to observation.

To investigate the succession of functional microorganisms of the lab-scale reactors, sludge samples were collected from the middle section of the packing bed on Day 81 to analyze the microbial community structure at the steady phase. Total genomic DNA was extracted using the TGuide S96 Soil Kit (Tiangen Biotech (Beijing) Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). The hypervariable V3-V4 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified using primers 338F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCA-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′). The amplicons were purified, quantified, and sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq platform by Beijing Saiojino Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China), generating an average of 79,043 raw reads per sample (ranging from 76,194 to 80,054).

Raw sequencing data were processed using a standard bioinformatics pipeline. Briefly, raw reads were quality-filtered using Trimmomatic (version 0.39), and paired-end reads were merged using Usearch. Chimeric sequences were identified and removed using UCHIME to obtain high-quality effective tags (average effective rate: 91.85%). Sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at a 97% similarity threshold. Taxonomic annotation was assigned against the Silva 138 database using the BLAST algorithm (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi, accessed on 14 January 2026).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

To evaluate the stability and reproducibility of the reactor performance, water quality parameters were monitored continuously throughout the experiment. Data collected during the steady-state operation phase of each HRT are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), representing the temporal variability of the system (n > 3). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA), and data plotting was conducted using OriginPro 2021 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was used to determine the statistical significance of differences in nitrogen removal performance among different fillers. Differences were considered statistically significant at p-value < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of S0-CFs

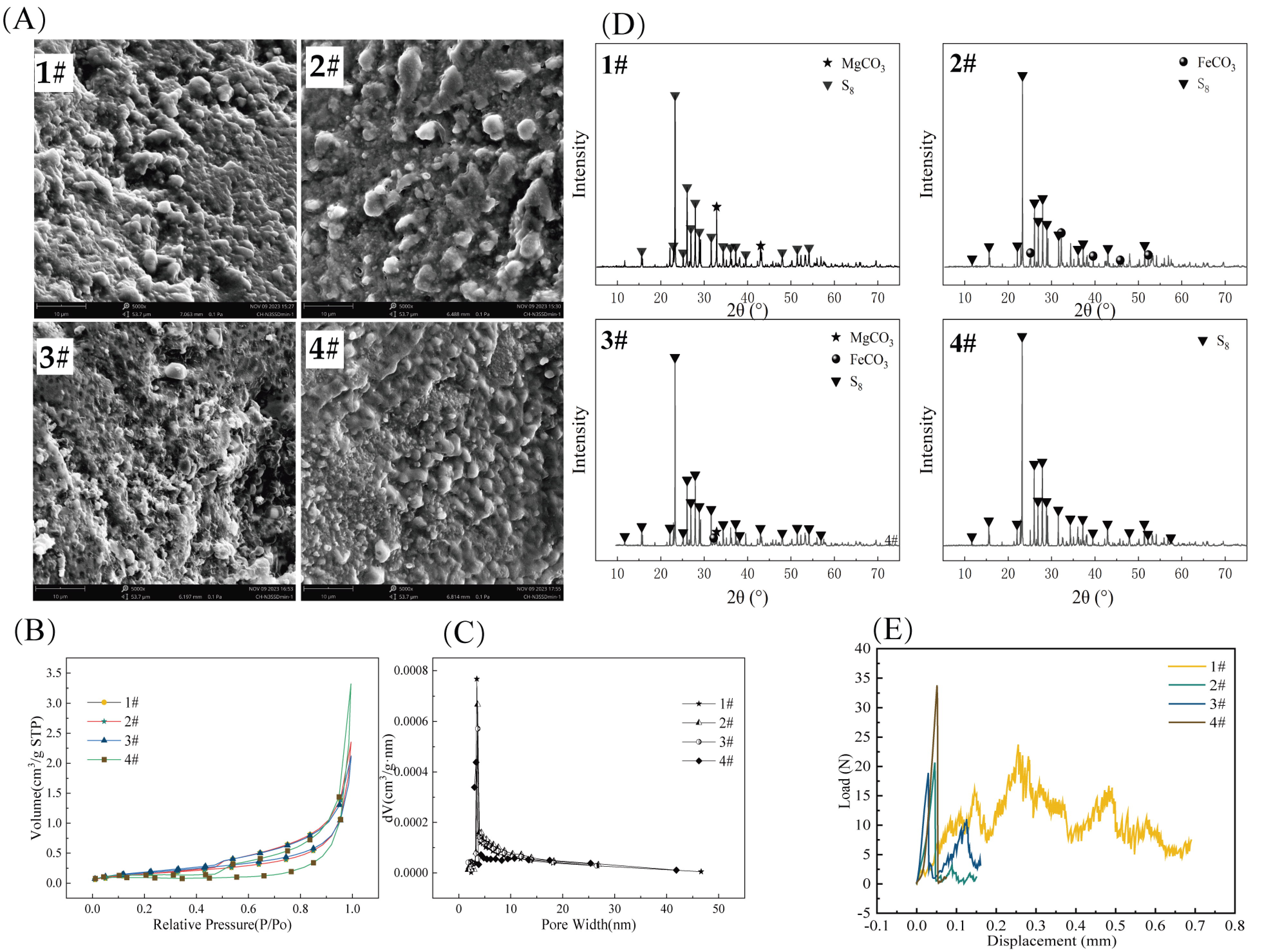

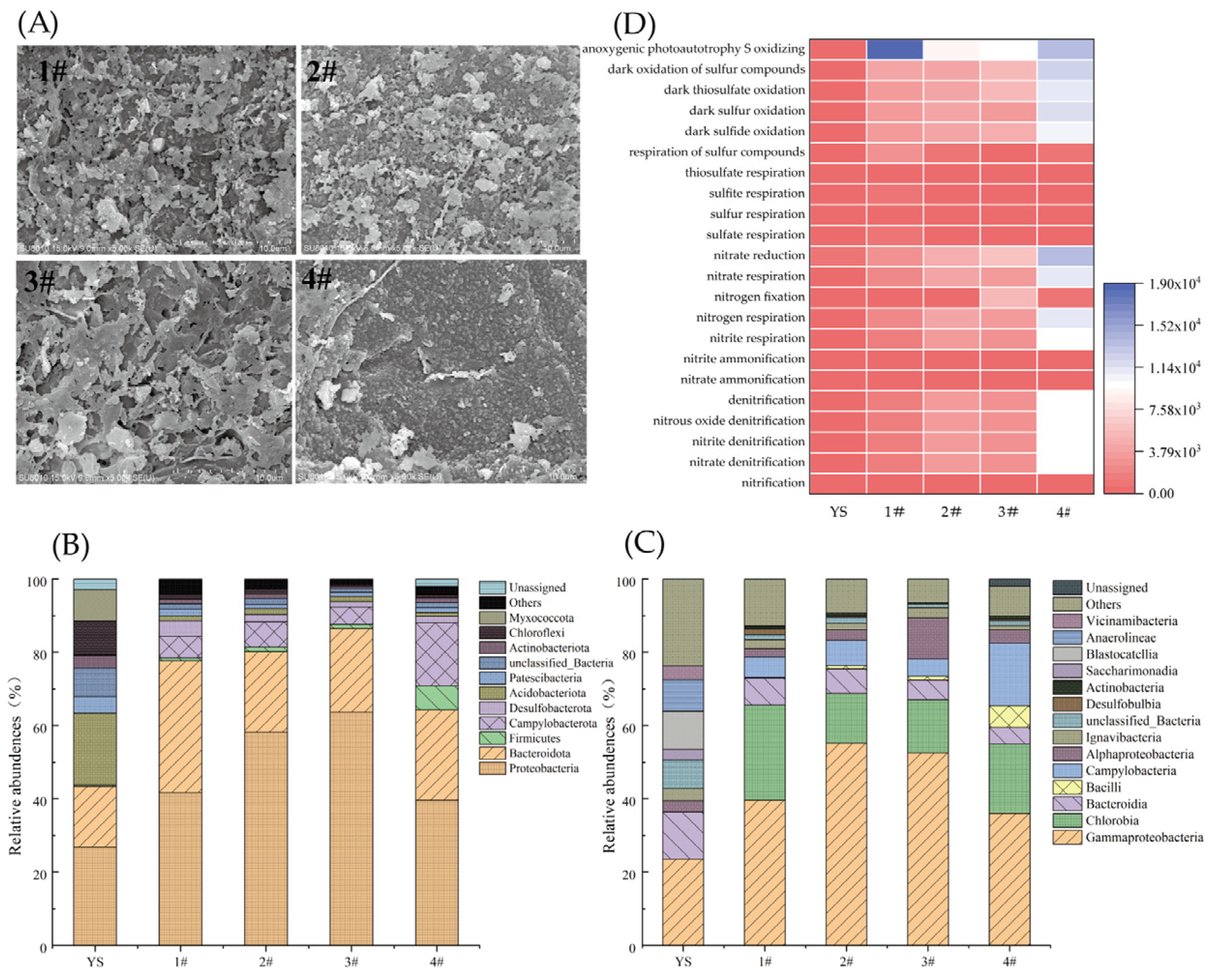

As shown in Figure 2A, the surfaces of all four S0-CFs were covered with crisscrossed grooves and ridges, which could provide attachment spaces for the growth and reproduction of microorganisms. From the adsorption–desorption isotherms, as shown in Figure 2B, all four types of S0-CFs exhibited H3-type hysteresis loops at relative pressures ranging from 0.1 to 1.0, which were classified as Type IV isotherms [16], and no obvious saturated adsorption plateau was observed for any of the S0-CFs. The pore size distribution curves in Figure 2C indicated that the pore diameters of the four fillers ranged from 2 to 50 nm, confirming the presence of mesoporous structures. The specific surface areas of S0-CFs were 0.59, 0.71, 0.66, and 1.01 m2/g, respectively, and the average pore diameters were 24.84, 21.37, 19.82, and 27.00 nm, respectively. The average pore size of S0-CF 4# was markedly larger than that of S0-CF 2# and 3# (p < 0.05), which likely facilitated internal mass transfer. The average pore volumes were 3.64 × 10−3, 3.81 × 10−3, 3.28 × 10−3, and 6.80 × 10−3 cm3/g, respectively.

Figure 2.

(A) SEM photographs, (B) adsorption–desorption isotherm curves, (C) pore size distribution curves, (D) XRD patterns, and (E) compressive strength of the four types of S0-CFs (1#, 2#, 3#, and 4#).

XRD pattern (Figure 2D) analysis revealed distinct crystalline phases corresponding to the raw materials used in each S0-CF. S0-CF 1# exhibited distinct characteristic peaks of MgCO3 at 32.7° and 43.0°, which corresponded to the standard card of MgCO3 (PDF#97-007-7482). S0-CF 2# showed obvious diffraction peaks of FeCO3 at 32.1°, 38.5°, 42.4°, 46.3° and 52.8°, corresponding to the standard card of FeCO3 (PDF#00-012-0531). S0-CF 3# displayed a prominent MgCO3 diffraction peak at 32.7° and a distinct FeCO3 diffraction peak at 32.1°. All other characteristic peaks of S0-CF 1#, 2#, and 3# were consistent with the S8 standard card (PDF#97-006-3083). S0-CF 4# was composed of 75% sulfur and 25% boron mud, and it could be seen from the XRD pattern that all diffraction peaks of the synthesized sample aligned with the S8 standard card (PDF#97-006-3083). In general, the four types of S0-CFs were mainly composed of elemental sulfur and a small amount of minerals.

As illustrated in the pressure load–displacement curves (Figure 2E), the maximum loads for S0-CF 1# to 4# were 23.73, 20.65, 18.89, and 33.77 N, respectively, corresponding to calculated compressive strengths of 0.95, 0.82, 0.75, and 1.35 MPa. Among the tested composites, S0-CF 4# (with the highest boron mud content) exhibited the highest compressive strength, representing a marked enhancement in mechanical stability. This reinforcement is likely attributed to the high MgO content in the boron mud. MgO possesses significant hydration reactivity [15] and can react with water to form magnesium hydroxide (Mg(OH)2) gels. These gels act as an inorganic binder, effectively bridging the discrete sulfur phases through interfacial bonding, thereby substantially improving the structural integrity and hardness of the filler.

3.2. SAD Performance of the Four S0-CFs at Varying HRTs

3.2.1. Nitrogen Removal

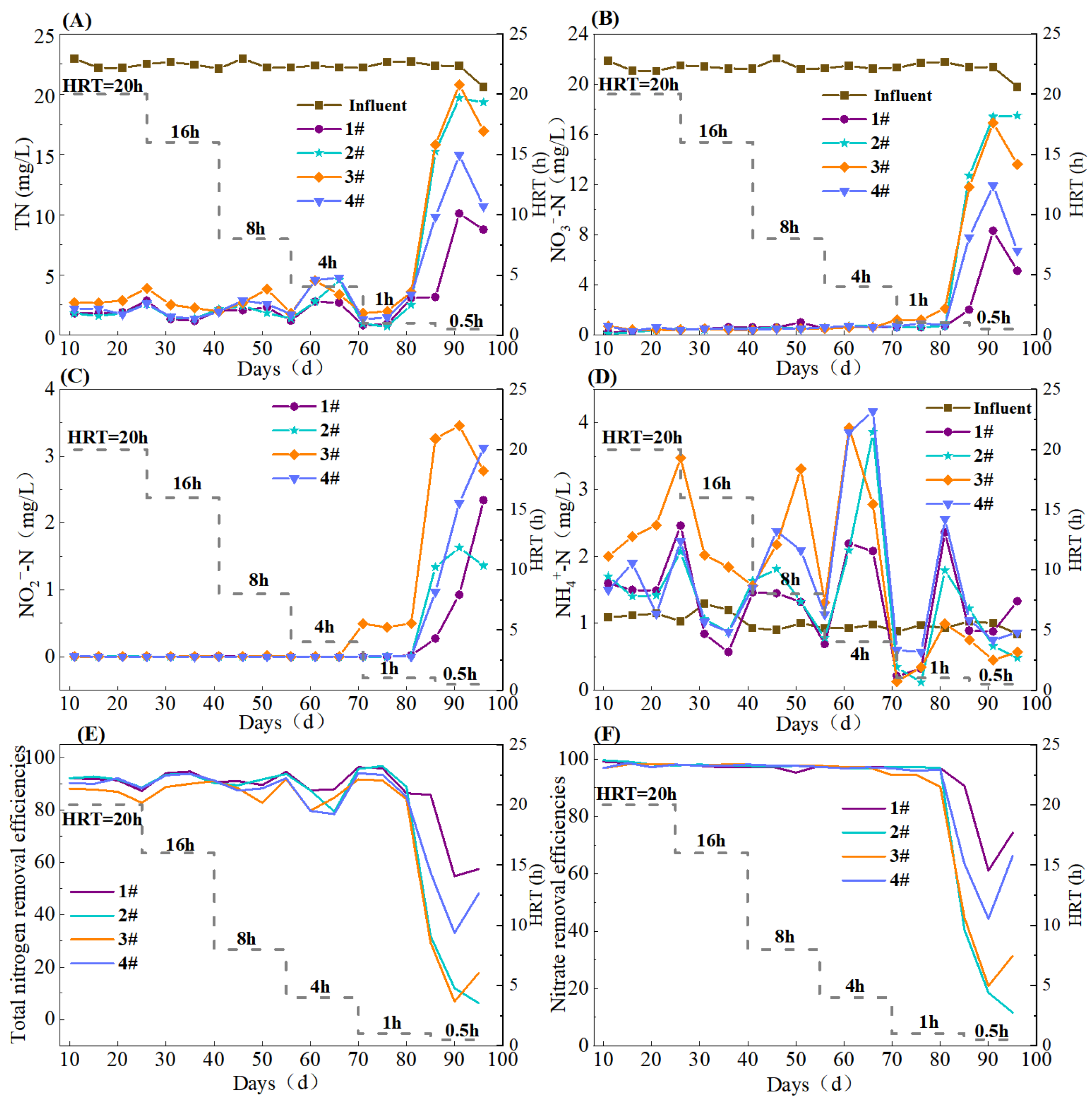

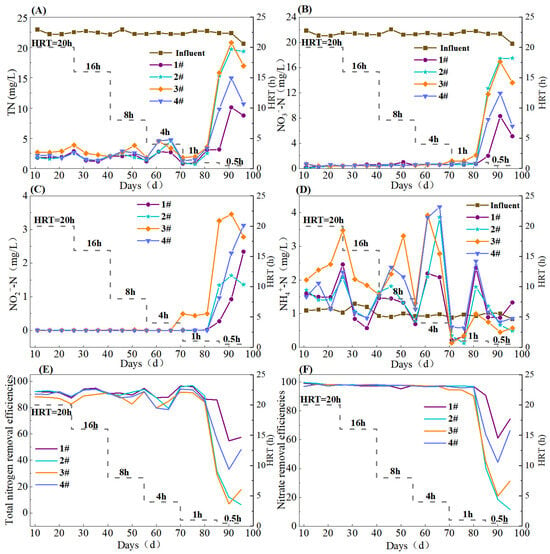

With HRT decreased from 20 to 1 h, the effluent TN concentrations of the S0-CF 1#–4# reactors were (1.92 ± 0.73), (2.00 ± 0.93), (2.83 ± 0.84), and (2.42 ± 1.09) mg/L, respectively (Figure 3A). Upon further reducing the HRT to 0.5 h, the effluent TN concentrations increased to (7.35 ± 3.68), (18.10 ± 2.46), (17.86 ± 2.62), and (18.1 ± 2.75) mg/L, respectively. All four reactors achieved the optimal nitrogen removal at an HRT of 1 h, with TN removal efficiencies of 92.91 ± 4.57%, 93.84 ± 3.48%, 89.08 ± 3.47%, and 90.93 ± 4.07%, respectively. Statistical analysis confirmed that the TN removal efficiency of the S0-CF 2# reactor was significantly higher than that of the S0-CF 3# and 4# reactors (p < 0.05). This significant performance gap is directly supported by the physicochemical characterization results in Section 3.1, which revealed distinct differences in mineral composition and pore structure among the fillers. The S0-CF 2# reactor exhibited the best TN removal performance, likely because Fe2+ released from FeCO3 acted as an electron donor to drive iron-autotrophic denitrification, synergizing with elemental sulfur for denitrification, and thus, enhancing nitrogen removal [17]. Additionally, FeCO3 contributed alkalinity to the system. The performance of the S0-CF 1# reactor was slightly inferior, presumably because, although MgCO3 supplied alkalinity, the synergistic effect of Fe2+-driven denitrification was absent.

Figure 3.

Nitrogen removal efficacy of S0-CF 1#–4# reactors ((A) TN, (B) NO3−-N, (C) NO2−-N, (D) NH4+-N, (E) TN removal efficiency, (F) NO3−-N removal efficiency).

The S0-CF 3# reactor showed the poorest performance, likely due to its smallest average pore size, which limited available contact sites for microbial activities. Conversely, the S0-CF 4# had the largest average pore size; however, an excessively large pore may cause overly smooth water flow within the filler, leading to short-circuiting and insufficient contact between substrates and microorganisms [18]. In addition, although MgO in boron mud provided some alkalinity, its buffering capacity was weaker than that of MgCO3 in the S0-CF 1#. Combined with the absence of Fe2+, the overall nitrogen removal efficiency of the S0-CF 4# reactor was slightly lower than those of the S0-CF 1# and 2# reactors.

Regarding the reduction of nitrate, with HRT gradually reduced from 20 to 4 h, all four reactors achieved effluent NO3−-N concentrations below 1 mg/L, with removal efficiencies exceeding 95% (Figure 3B). In particular, at an HRT of 1 h, the effluent NO3−-N concentration of the S0-CF 3# reactor increased to 1.50 ± 0.42 mg/L, and the removal efficiency decreased to 93.07 ± 1.92%, while the NO3−-N removal of the other three reactors was stably maintained. At an HRT of 0.5 h, the nitrate removal collapsed across all reactors, with the effluent NO3−-N concentrations rising to 5.13 ± 2.57, 15.87 ± 2.24, 14.10 ± 2.11, and 8.80 ± 2.24 mg/L, respectively, and the average removal efficiencies dropping to 75.33 ± 12.06%, 23.52 ± 12.32%, 32.29 ± 9.75%, and 57.96 ± 9.73%. This sharp decline corresponded to the simultaneous spike in effluent TN, NO3−-N, and NO2−-N concentrations observed around Day 78 (Figure 3). This fluctuation coincided with the transition to the ultra-short HRT of 0.5 h. The sudden hydraulic shock likely caused temporary biofilm detachment and impaired electron transfer, resulting in incomplete denitrification [19]. However, the performance subsequently stabilized, suggesting that the system gradually adapted to the high hydraulic loading. Notably, NO2−-N accumulation first appeared in the S0-CF 3# reactor at an HRT of 1 h, with effluent concentration reaching 0.5 mg/L (Figure 3C). Upon further reducing the HRT to 0.5 h, effluent NO2−-N concentrations of S0-CF 1# to 4# reactors increased to 1.18 ± 0.86, 1.44 ± 0.13, 3.17 ± 0.29, and 2.13 ± 0.89 mg/L, respectively.

As shown in Figure 3D, when HRT was in the range of 20 to 4 h, the average effluent NH4+-N concentrations of the four reactors were significantly higher than the influent concentration. This might be attributed to dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (DNRA), a process that can be driven by reduced sulfur species (e.g., H2S/HS−) acting as electron donors under low-hydraulic-loading conditions [20,21]. However, when HRT was reduced to 1–0.5 h, the effluent NH4+-N concentrations approached the influent level, indicating the DNRA activity was suppressed under high hydraulic loading.

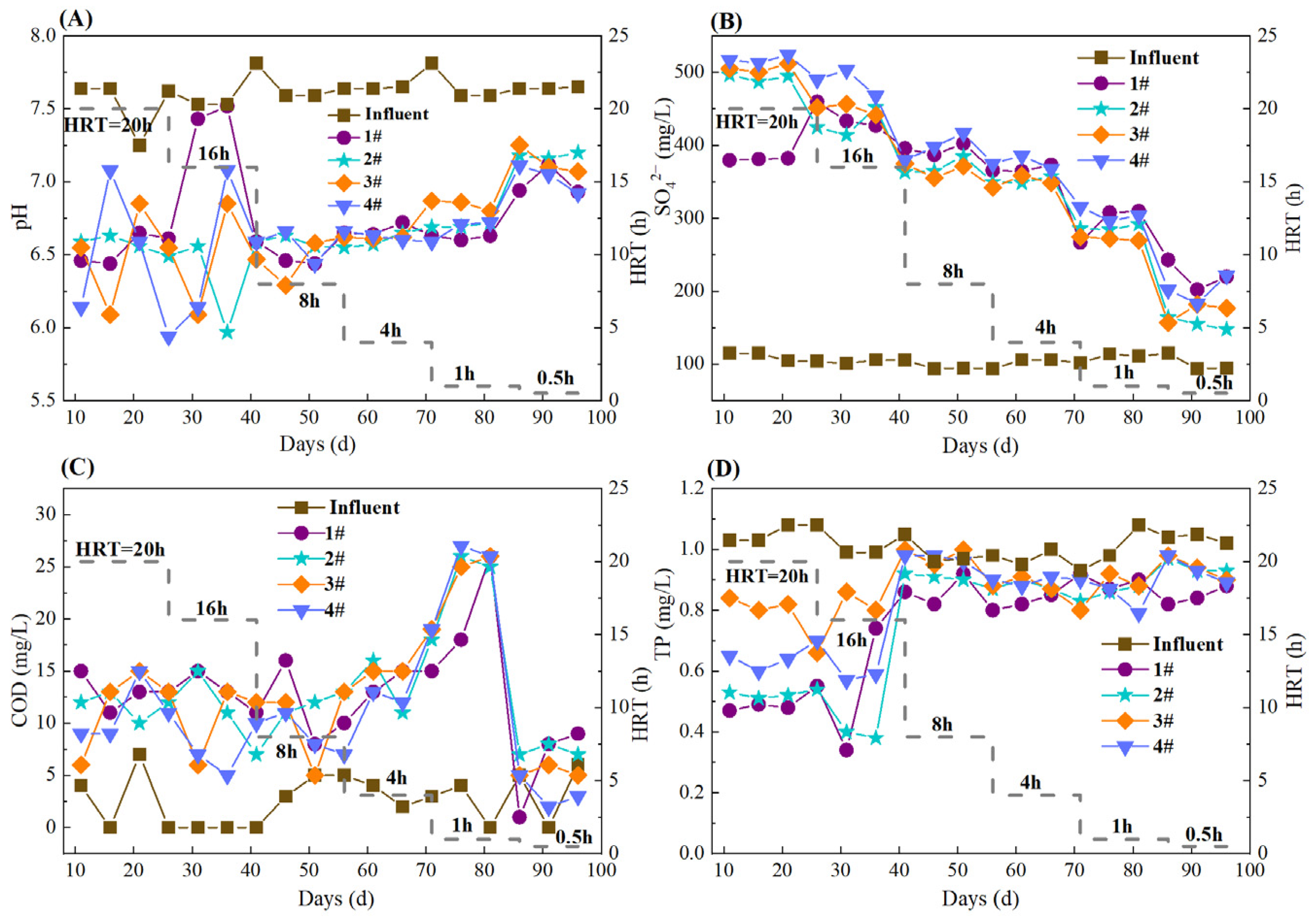

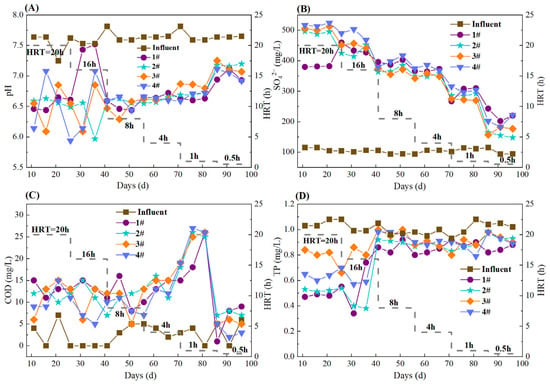

3.2.2. Variations in Effluent SO42−, COD and TP Concentrations

During the whole operation, the pH in the S0-CF 1#–4# reactors remained relatively stable and ranged from 6.44 to 7.52 (S0-CF 1#), 5.97 to 7.20 (S0-CF 2#), 6.09 to 7.25 (S0-CF 3#), and 5.94 to 7.11 (S0-CF 4#) (Figure 4A). These were consistent with the typical effluent pH range of 6.67–7.29 reported for SAD systems [5], indicating the good buffering capacity of the prepared S0-CFs. Theoretically, the removal of 1 mg of NO3−-N will produce 7.54 mg of SO42− [22]. In this study, the actual SO42− production yield ratio (mg SO42− produced per mg NO3−-N removed) decreased as HRT was shortened. At HRTs of 20, 16, 12, 8, and 4 h, the average SO42− yield ranged from 11.31 to 20.20 mg SO42−/mg NO3−-N (Figure 4B), exceeding the theoretical value. The possible reason was the occurrence of sulfur disproportionation, in which elemental sulfur, sulfite, or thiosulfate acted as both electron donor and acceptor, yielding SO42− and sulfide [23]. When the HRT was further shortened to 1 h, the SO42− yield ratios in the S0-CF 1#–4# reactors declined to 8.95 ± 1.07, 8.60 ± 0.19, 8.21 ± 0.14, and 9.53 ± 0.51 mg SO42−/mg NO3−-N, respectively (Figure 4B), indicating that the shorter HRT suppressed sulfur disproportionation. This trend is consistent with the findings of Wan et al. [24], who reported that the yields of sulfide and SO42− in SAD systems increased with longer HRT.

Figure 4.

Variations in water quality parameters in S0-CF 1#–4# reactors. (A) Variations in effluent pH; (B) Effluent SO42− concentrations; (C) Effluent COD concentrations; (D) Effluent TP concentrations.

As shown in Figure 4C, the influent COD concentration was generally below 7.0 mg/L. At HRTs of 20, 16, 12, 8, and 4 h, the increment of effluent COD remained relatively stable, ranging from 5.0 to 15.0 mg/L. When the HRT was shortened to 1 h, the effluent COD increment increased significantly, with the effluent concentration ranging from 15.0 to 26.0 mg/L and fluctuating sharply. This rise was likely due to the excessive water flow impact causing substantial biofilm detachment, which released extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs) and microbial debris into the effluent. Upon further shortening the HRT to 0.5 h, the effluent COD declined rapidly after an initial peak and stabilized below 10.0 mg/L, suggesting that the loosely attached biomass had been largely washed out, resulting in a new steady state with minimal organic release. Additionally, the effluent TP concentrations in all four S0-CF reactors were lower than the influent TP concentration (Figure 4D), indicating that TP removal occurred, probably attributable to the precipitation of iron phosphate or magnesium phosphate, as previously reported [1,8,25], as well as microbial assimilation. Nevertheless, the effluent TP concentrations generally exceeded the stringent limit of 0.5 mg/L (Class I-A) [26]. This limited removal efficiency is likely constrained by the low biomass yield of sulfur-autotrophic denitrifiers, which restricts further phosphorus uptake via cell synthesis.

3.3. Succession of Microbial Community Structures

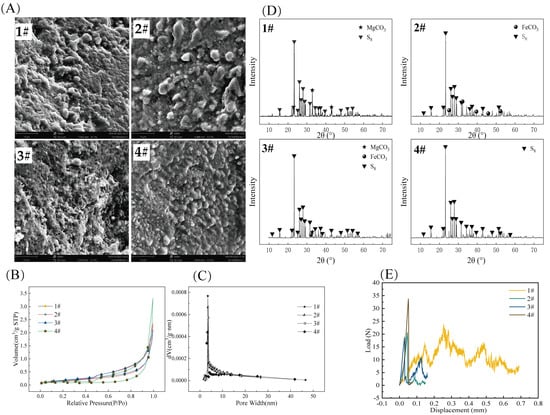

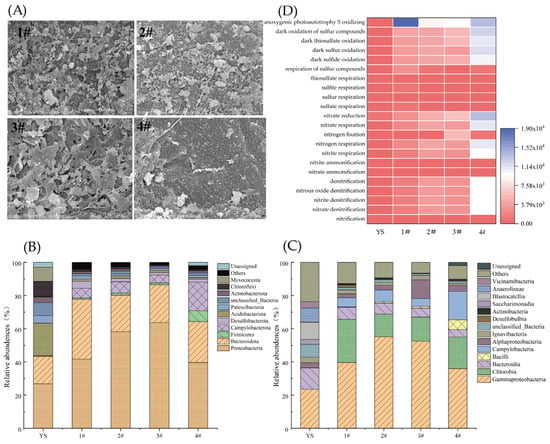

3.3.1. Microbial Morphology on the Surface of S0-CFs

A large number of microorganisms were observed on the surfaces of the four S0-CFs on Day 81 (HRT was 1 h) (Figure 5A). Obvious etch pits appeared on the surface of the S0-CFs, with some areas even showing hollowing. This proved the utilization of the fillers as electron donors to the nitrate removal process by the functional microorganisms [25]. In addition, the microbial morphology and etching degree on the surfaces of the four types of S0-CFs varied from each other, which was mainly associated with the mineral compositions of the fillers [27].

Figure 5.

Characterization of S0-CFs and microbial communities in S0-CF 1#–4# reactors operated at a constant temperature of (25 ± 2) °C. (A) SEM images of S0-CFs 1#–4# at day 81; microbial community’s (B) phylum-level and (C) genus-level composition; and (D) FAPROTAX heatmap of nitrogen and sulfur metabolism functions.

3.3.2. Microbial Community Structure

At the phylum level (Figure 5B), the microbial communities in all S0-CF reactors underwent significant restructuring compared to the inoculated sludge (YS). Proteobacteria became the dominant phylum across all reactors, increasing from 26.8% in inoculated sludge to 41.76%, 58.12%, 63.67%, and 39.63% in S0-CF 1# to 4# reactors, reflecting strong selection for sulfur- and nitrogen-cycling microorganisms under autotrophic denitrification conditions [28]. The relative abundances of Bacteroidota in S0-CF 1# to 4# reactors were 35.92%, 22.03%, 22.79%, and 24.64%, respectively, and have also been reported to play a key role in nitrate removal [29]. In contrast, Actinobacteria, Chloroflexi, and Acidobacteria generally decreased, reflecting a selective pressure that favored specific functional groups while suppressing others [30,31].

At the genus level (Figure 5C), Chlorobium emerged as the most abundant classified taxon, accounting for 24.72%, 13.38%, 14.52%, and 18.85% in S0-CF 1# to 4# reactors, respectively. Chlorobium is a green sulfur bacterium capable of photoautotrophic oxidation of S2− to S0 using light energy. Given that the reactors were operated under ambient laboratory lighting (not complete darkness), the high abundance of Chlorobium suggested it might actively contribute to sulfur cycling. Its presence—along with SO42− accumulation in the effluent—supported the occurrence of both phototrophic sulfur oxidation and sulfur disproportionation.

Concurrently, several genera known to harbor complete denitrification pathways were enriched relative to the inoculated sludge (0%). These include Sulfurimonas (1.97–13.88%) and Thiobacillus (0.13–2.71%), both of which are capable of reducing NO3− or NO2− to N2 using reduced sulfur compounds (e.g., S0, S2−, SO32−) or H2 as electron donors [32]. Additionally, the facultative denitrifier Thiomonas was detected at low but consistent levels (0.36–2.66%); this genus has been reported in hydrogen-based, sulfur-based, and electrochemical denitrification systems [33]. These functional genera possess genes encoding key denitrification enzymes, including nitrate reductase (narG), nitrite reductase (nirS or nirK), nitric oxide reductase (norB), and nitrous oxide reductase (nosZ), enabling complete reduction of NO3− to N2 [34,35,36].

The coexistence of phototrophic (Chlorobium) and chemolithoautotrophic (Sulfurimonas, Thiobacillus) sulfur oxidizers reveals a dual-pathway sulfur metabolism in the S0-CF system. This metabolic versatility, combined with the enrichment of both sulfur-cycling and potentially fermentative taxa (e.g., Bacteroidota), likely enhances the functional stability of nitrate removal under varying operational conditions.

FAPROTAX was employed to predict the potential metabolic functions of the microbial community based on 16S rRNA gene sequences (Figure 5D). Compared to the inoculated sludge (YS), S0-CF 1#–4# reactors exhibited a marked enrichment in functional groups involved in autotrophic denitrification and sulfur oxidation. Specifically, all steps of the denitrification pathway, including nitrate reduction, nitrite reduction, nitrate denitrification, nitrite denitrification, and nitrous oxide denitrification, were significantly enhanced, with predicted abundances increasing by 11.7- to 64.7-fold across the reactors. Concurrently, multiple dark sulfur oxidation processes, such as dark sulfur oxidation, dark sulfide oxidation, and dark thiosulfate oxidation, showed dramatic increases, rising from low levels in the inoculated sludge (<50) to over 10,000 in the S0-CF 4# reactor. The observed shift in the microbial community structure is directly linked to the enrichment of functional sulfur-oxidizing denitrifiers. As confirmed by FAPROTAX analysis, functional groups associated with ‘dark sulfur oxidation’ and ‘nitrate reduction’ increased by over 100-fold compared to the inoculum. Specifically, the genus Thiobacillus (within the dominant phylum Proteobacteria) and the genus Sulfurimonas (within the phylum Campylobacterota) were significantly enriched. Both are well-documented autotrophic denitrifiers capable of coupling nitrate reduction with sulfur oxidation [32], providing a robust biological mechanism for the observed nitrogen removal performance.

3.4. Application of SAD Process Driven by S0-CF 4# in a Pilot-Scale Reactor Treating Actual PV Wastewater

Before the pilot operation, the selection of filler was critical. Although S0-CF 2# (containing siderite) exhibited marginally higher nitrogen removal efficiency in lab-scale tests, S0-CF 4# was selected for the pilot-scale application primarily due to its superior mechanical properties and economic feasibility. As shown in Figure 2E, S0-CF 4# demonstrated the highest compressive strength (1.35 MPa vs. 0.82 MPa for S0-CF 2#), which is essential to prevent clogging and channeling in long-term packed-bed operations.

Regarding environmental safety, the potential risk of boron leaching was minimized by the filler preparation method. The melt mixing–jet granulation process effectively encapsulates the boron mud particles within the hydrophobic elemental sulfur matrix, which acts as a physical barrier to retard the release of soluble minerals. Furthermore, the sustained high nitrogen removal efficiency and robust microbial enrichment observed over the 270-day operation serve as strong indirect evidence that no inhibitory or toxic levels of hazardous substances (including boron) were accumulated in the system. Nevertheless, to fully validate the long-term environmental safety, continuous monitoring of trace elements in the effluent will be conducted in our future engineering applications.

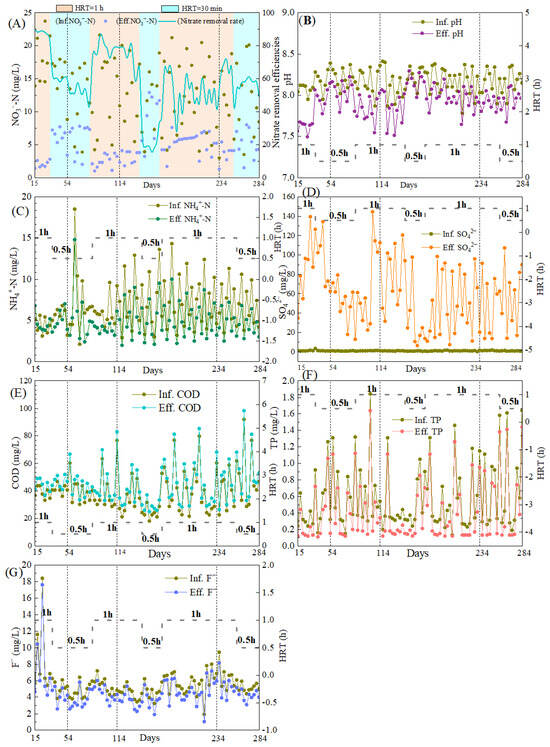

3.4.1. Nitrogen Removal Performance

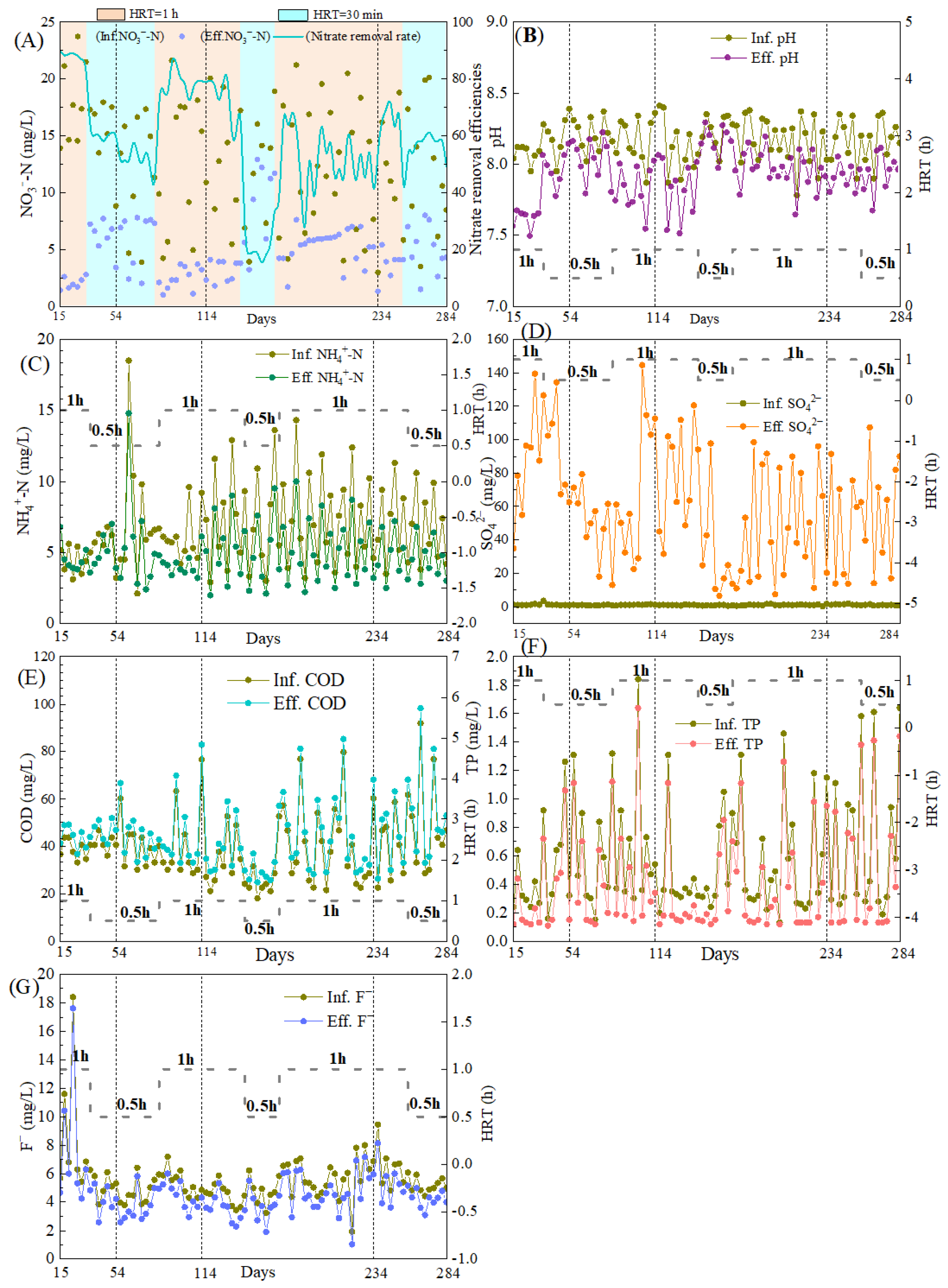

The pilot-scale reactor was operated for 270 days, and, especially in Phase 3 (days 15–284), the reactor was operated under alternating HRT (1 h and 0.5 h) across naturally varying wastewater temperatures (7.3–27.2 °C). Results found that the NO3−-N removal performance was strongly influenced by both temperature and HRT. From Day 15 to 54 (wastewater temperature: 25.8–27.2 °C), the system achieved high and stable NO3−-N removal efficiencies of 86.6–90.0% (average: 88.2 ± 1.3%) at an HRT of 1 h. When the HRT was reduced to 30 min, NO3−-N removal decreased but remained relatively robust, with efficiencies of 57.1–61.4% and effluent NO3−-N concentrations consistently below 7.7 mg/L. At days 55–114 (temperature: 17.2–25.5 °C), the NO3−-N removal efficiency declined, particularly at a short HRT, where it dropped to 35.6%, though effluent NO3−-N remained below 7.8 mg/L. During the cold period (days 115–234, temperature: 7.3–16.0 °C), the system became highly sensitive to HRT reduction. At HRT of 30 min, NO3−-N removal fell to 13.5–38.1%, and effluent NO3−-N concentrations rose to 9.4–12.9 mg/L. However, extending HRT to 1 h effectively ensured effluent NO3−-N below 8.0 mg/L (NO3−-N removal efficiency of 64.1%). As temperatures increased during days 235–284 (11.0–20.1 °C), the NO3−-N removal performance gradually recovered, with the nitrate removal efficiency improving to 78.2% at an HRT of 1 h and 59.8% at 30 min. These results confirmed that temperature was the primary factor controlling SAD, and adjusting HRT to 1 h was an effective operational strategy to stabilize the performance during low-temperature periods [37].

Variations in pH and concentrations of NH4+-N, SO42−, COD, TP, and F− are shown in Figure 6. Throughout the operation, pH remained stable both in influent and effluent (Figure 6B), ranging from 7.78 to 8.41 and 7.49 to 8.29, respectively. The smaller pH drop compared to our previous lab-scale study was likely due to lower and more variable influent NO3−-N concentrations (mostly <15 mg/L), which reduced acid generation during denitrification. Effluent NH4+-N concentrations showed minimal change relative to the influent (Figure 6C), suggesting limited DNRA, possibly owing to the short HRT. On average, 7.23 mg of SO42− was produced per 1 mg of NO3−-N removed, which was slightly below the theoretical stoichiometric value of 7.54 mg, reflecting the partial nitrogen assimilation by biomass [38]. Influent COD and TP concentrations exhibited patterns consistent with those observed in the lab-scale experiments (Figure 6E,F). Influent F− concentrations varied widely (1.91–18.40 mg/L, Figure 6G), yet consistent removal was observed, with 0.51–1.49 mg/L of F− eliminated. The reactor thus demonstrated a measurable capacity for F− attenuation. This was likely attributed to the adsorption onto the porous S0-CF carrier, and the precipitation as MgF2, facilitated by Mg2+ released from MgO, which was the primary component of boron mud incorporated into the S0-CF 4# [39].

Figure 6.

Nitrogen removal performance and water quality variations in the pilot-scale reactor. (A) Nitrogen removal performance; (B) Variations in effluent pH; (C) Effluent NH4+-N concentrations; (D) Effluent SO42− concentrations; (E) Effluent COD concentrations; (F) Effluent TP concentrations; (G) Effluent F− concentrations.

3.4.2. Cost Analysis

Unit price of four types of S0-CF: The unit costs of the S0-CFs were calculated based on the procurement prices of raw materials: sulfur at 2.8 CNY/kg, boron mud at 0.2 CNY/kg, magnesite at 1.3 CNY/kg, and siderite at 1.5 CNY/kg. According to the different formulation ratios, the unit prices were as follows: S0-CF 1# at 2.32 CNY/kg, S0-CF 2# at 2.35 CNY/kg, S0-CF 3# at 2.33 CNY/kg, and S0-CF 4# at 2.15 CNY/kg. Among them, S0-CF 4# exhibited the lowest unit mass cost and thus demonstrated the best economic performance.

Consumption cost of S0-CF 4#: the pilot-scale reactor was operated for 170 days at an HRT of 1 h, treating 122.40 m3 of wastewater, and for 100 days at an HRT of 30 min, treating 144.00 m3 of wastewater. Over the entire period, a total decrease in filler bed height of 8.9 cm was observed. After excluding the 18-day period during which effluent NO3−-N concentrations exceeded the discharge limit (during which the bed height decreased by 1.3 cm, and 25.92 m3 of wastewater was treated), the corrected data showed a net bed height reduction of 7.6 cm, corresponding to a filler consumption of 6.11 kg and a total treated wastewater volume of 240.48 m3. Given that the unit price of S0-CF #4 was 2.15 CNY/kg, the annual filler consumption rate was approximately 31%, resulting in a material cost of 0.055 CNY per cubic meter of treated wastewater, calculated as follows:

Considering that the carbon source (sodium acetate) required 0.084 CNY/m3 in the heterotrophic denitrification process used in the same wastewater treatment plant, comparative analysis showed that by using the S0-CF 4#, the consumption cost of the SAD process was reduced by 34.5% compared with the traditional denitrification process using organic carbon-source addition, demonstrating a superior cost-effectiveness advantage.

4. Conclusions

This study evaluated the nitrogen removal performance of four S0-CFs prepared by melting magnesite, siderite, boron mud, and elemental sulfur in different proportions. At HRT = 1 h, optimal performance was achieved, with TN removal > 90%. Effluent NO3−-N concentrations remained below 1.5 mg/L, corresponding to removal efficiencies above 93%. The effluent pH was stable, and no significant increases in COD or TP were observed, indicating negligible secondary contamination from the fillers. 16S rRNA sequencing confirmed the significant enrichment of key autotrophic denitrifiers, specifically Thiobacillus (affiliated with Proteobacteria) and Sulfurimonas (affiliated with Campylobacterota). Compared to the inoculum, their abundance increased markedly, confirming that sulfur-based autotrophic denitrification was the dominant nitrogen removal pathway. A 270-day pilot verified that filler 4, composed solely of boron mud and elemental sulfur, stably produced nitrate-compliant effluent, with partial NH4+-N/F− removal. Notably, the operational cost related to electron donor consumption was approximately 34.5% lower than that of conventional heterotrophic denitrification [40]. These results suggest that boron mud is a potentially feasible and cost-effective filler feedstock, supporting industrial waste valorization and low-carbon water treatment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.Z. and M.L.; methodology, Q.Z. and M.L.; software, Q.Z.; validation, Q.Z., Z.X., S.F. and M.L.; formal analysis, Q.Z. and Y.Z.; investigation, Q.Z., Z.X., S.F., Y.Z., D.C., J.S., H.W., L.H., X.S. and J.Y.; resources, M.L.; data curation, Q.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.Z.; writing—review and editing, M.L., Q.Z., Y.Z. and J.S.; visualization, Q.Z.; supervision, M.L.; project administration, M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Qwen (Model: Qwen3-Max; https://tongyi.aliyun.com/; accessed on 27 January 2026) for language revision and editing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors were employed by the company China Railway Construction Development Group Co., Ltd. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Pang, Y.; Wang, J. Various electron donors for biological nitrate removal: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 794, 148699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Capua, F.; Pirozzi, F.; Lens, P.N.; Esposito, G. Electron donors for autotrophic denitrification. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 362, 922–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wu, G.; Li, R.; Xiao, L.; Zhan, X. Iron sulphides mediated autotrophic denitrification: An emerging bioprocess for nitrate pollution mitigation and sustainable wastewater treatment. Water Res. 2020, 179, 115914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi, S.; Modin, O.; Mijakovic, I. Technologies for biological removal and recovery of nitrogen from wastewater. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020, 43, 107570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Pang, C.; Wen, Q. Coupled pyrite and sulfur autotrophic denitrification for simultaneous removal of nitrogen and phosphorus from secondary effluent: Feasibility, performance and mechanisms. Water Res. 2023, 243, 120422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, A.; Liu, L. Use of limestone for pH control in autotrophic denitrification: Continuous flow experiments in pilot-scale packed bed reactors. J. Biotechnol. 2002, 99, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Z.; Li, L.; Feng, C.; Dong, S.; Chen, N. Comparative investigation on integrated vertical-flow biofilters applying sulfur-based and pyrite-based autotrophic denitrification for domestic wastewater treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 211, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guo, J.; Li, H.; Song, Y.; Chen, Z.; Lu, C.; Han, Y.; Hou, Y. Effect of dissolved oxygen on simultaneous removal of ammonia, nitrate and phosphorus via biological aerated filter with sulfur and pyrite as composite fillers. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 296, 122340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Meng, J.; Hu, Y.; Lee, P.-H.; Zhan, X. A review in Fe(0)/Fe(II) mediated autotrophic denitrification for low C/N wastewater treatment. Water Res. 2025, 282, 123925. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Morrison, L.; Collins, G.; Li, A.; Zhan, X. Simultaneous nitrate and phosphate removal from wastewater lacking organic matter through microbial oxidation of pyrrhotite coupled to nitrate reduction. Water Res. 2016, 96, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, T.; Zhang, X.; Qing, C.; Wang, J.; Yue, Z.; Liu, H.; Yang, Z. Simultaneous removal of nitrate and phosphate from wastewater by siderite based autotrophic denitrification. Chemosphere 2018, 199, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, M.; Zhou, S.; Ying, L.; Yang, H.; Xue, X.; Hsu, S.-C. From waste to defense: Cost-efficient upcycling of boron mud to nuclear radiation shielding. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 211, 107884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Liu, H.; Chen, X.; Ren, C.; Zhao, X.; Jing, Y.; Cheng, D.; Zhang, J. Enhancement of nitrogen removal in constructed wetlands through boron mud and elemental sulfur addition: Regulation of sulfur and oxygen cycling. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 497, 154544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrentó, C.; Urmeneta, J.; Edwards, K.J.; Cama, J. Characterization of attachment and growth of Thiobacillus denitrificans on pyrite surfaces. Geomicrobiol. J. 2012, 29, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Guan, Y.; Bi, W. The effect of alcohol compound on the solidification of magnesium oxysulfate cement-boron mud blends. Materials 2022, 15, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Duan, R.; Hao, W.; Li, Q.; Arslan, M.; Liu, P.; Qi, X.; Huang, X.; El-Din, M.G.; Liang, P. High-rate nitrogen removal from carbon limited wastewater using sulfur-based constructed wetland: Impact of sulfur sources. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 744, 140969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, L.D.; Weibel, D.B. Physicochemical regulation of biofilm formation. MRS Bull. 2011, 36, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhussupbekova, A.; Shvets, I.V.; Lee, P.; Zhan, X. High-rate iron sulfide and sulfur-coupled autotrophic denitrification system: Nutrients removal performance and microbial characterization. Water Res. 2023, 231, 119619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunet, R.; Garcia-Gil, L. Sulfide-induced dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonia in anaerobic freshwater sediments. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 1996, 21, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.-W.; Zhang, H.-L.; Shi, W.-M. Dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium in an anaerobic agricultural soil as affected by glucose and free sulfide. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2013, 58, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, W.; Yang, X.; Ren, Z.; Huang, K.; Qian, F.; Li, J. Long-term operation of a pilot-scale sulfur-based autotrophic denitrification system for deep nitrogen removal. Water 2023, 15, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Liu, F.; Fang, W.; Yang, T.; Chen, G.-H.; He, Z.; Wang, S. Microbial sulfur metabolism and environmental implications. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 778, 146085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, D.; Li, Q.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, S.; Wang, H. Simultaneous reduction of perchlorate and nitrate in a combined heterotrophic-sulfur-autotrophic system: Secondary pollution control, pH balance and microbial community analysis. Water Res. 2019, 165, 115004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wei, D.; Li, F.; Zhang, Y.; Li, R. Sulfur-siderite autotrophic denitrification system for simultaneous nitrate and phosphate removal: From feasibility to pilot experiments. Water Res. 2019, 160, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 18918-2002; Discharge Standard of Pollutants for Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plant. China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 2002.

- Li, D.; Liu, L.; Zhang, G.; Ma, C.; Wang, H. Sulfur-manganese carbonate composite autotrophic denitrification: Nitrogen removal performance and biochemistry mechanism. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 272, 116048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Chen, C.; Lee, D.-J. Nitrogen and sulfur metabolisms of Pseudomonas sp. C27 under mixotrophic growth condition. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 293, 122169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Lv, D.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, X.; Lou, Z.; Baig, S.A.; Xu, X. Adsorption of mercury (II) from aqueous solutions using FeS and pyrite: A comparative study. Chemosphere 2017, 185, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, N.; Sierra-Alvarez, R.; Amils, R.; Field, J.; Sanz, J. Compared microbiology of granular sludge under autotrophic, mixotrophic and heterotrophic denitrification conditions. Water Sci. Technol. 2009, 59, 1227–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, P.; Li, H.; Tian, Y.; Wang, S.; Song, Y.; Zeng, G.; Sun, C.; Tian, Z. Denitrification of landfill leachate under different hydraulic retention time in a two-stage anoxic/oxic combined membrane bioreactor process: Performances and bacterial community. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 250, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; He, S.; Huang, J.C. Comparison of microbial communities in different sulfur-based autotrophic denitrification reactors. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matassa, S.; Verstraete, W.; Pikaar, I.; Boon, N. Autotrophic nitrogen assimilation and carbon capture for microbial protein production by a novel enrichment of hydrogen-oxidizing bacteria. Water Res. 2016, 101, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arsène-Ploetze, F.; Koechler, S.; Marchal, M.; Coppée, J.-Y.; Chandler, M.; Bonnefoy, V.; Brochier-Armanet, C.; Barakat, M.; Barbe, V.; Battaglia-Brunet, F. Structure, function, and evolution of the Thiomonas spp. genome. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6, e1000859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beller, H.R.; Letain, T.E.; Chakicherla, A.; Kane, S.R.; Legler, T.C.; Coleman, M.A. Whole-genome transcriptional analysis of chemolithoautotrophic thiosulfate oxidation by Thiobacillus denitrificans under aerobic versus denitrifying conditions. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 7005–7015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievert, S.M.; Scott, K.M.; Klotz, M.G.; Chain, P.S.; Hauser, L.J.; Hemp, J.; Hügler, M.; Land, M.; Lapidus, A.; Larimer, F.W. Genome of the epsilonproteobacterial chemolithoautotroph Sulfurimonas denitrificans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 1145–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Wang, L.; Jia, T.; Li, X.; Zhang, Q.; Peng, Y. Elemental sulfur–siderite composite filler empowers sustainable tertiary treatment of municipal wastewater even at an ultra-low temperature of 7.3 °C. Nat. Water 2024, 2, 782–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Zeng, M.; Zou, W.; Jiang, W.; Kahaer, A.; Liu, S.; Hong, C.; Ye, Y.; Jiang, W.; Kang, J. A new strategy to simultaneous removal and recovery of nitrogen from wastewater without N2O emission by heterotrophic nitrogen-assimilating bacterium. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 872, 162211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, H.; Chen, X.; Li, N.; Zhao, W. Experimental investigation on preparation of NaMgF3 and MgF2 from the leaching solution of SPL. JOM 2023, 75, 3480–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ma, Q.; Tang, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Z.; Deng, S. Application Potential of Sulfur-Based Autotrophic Denitrification in Low Carbon Wastewater Treatment: Efficiency, Cost and Greenhouse Gas Emission Reduction. Water 2025, 17, 3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.