Abstract

Microplastics (MPs) and their chemical leachates are increasingly detected in landfill leachate, raising concerns about impacts on biological nitrogen removal. This study examined the effects of low-density polyethylene (LDPE) and polypropylene (PP) MPs on anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) performance using suspended, attached, and granular biomass. The results showed that exposure to LDPE and PP MPs did not significantly inhibit specific anammox activity (SAA) across all anammox biomass types. However, the leachates of LDPE and PP MPs under relevant EU migration testing guidelines could cause transient inhibition. Non-targeted GC-MS analysis identified 31 and 37 leachable compounds from LDPE and PP, including the toxic plasticizer dibutyl phthalate (DBP). DBP caused concentration-dependent but transient inhibition of nitrogen removal in granular biomass, peaking at 29.4% after 5 h at 100 mg/L, with full recovery within 24 h. Higher DBP retention was observed in granular and attached growth biomass compared to suspended growth biomass. Crucially, complex biomass structures buffer these effects, emphasizing the need to assess both physical and chemical MP aspects in wastewater systems. Consequently, attached growth and granular systems are recommended over suspended growth configurations for leachate treatment, owing to their superior resilience to toxic shock and enhanced retention capabilities.

1. Introduction

Landfilling remains the most widely practiced method for municipal solid waste (MSW) disposal globally, primarily due to its economic and operational feasibility. However, the continuous production of landfill leachate (a complex, highly polluted effluent generated as water percolates through decomposing waste) presents a major environmental drawback. Leachate typically contains a mixture of organic matter, heavy metals, microplastics, and other emerging pollutants [1,2,3]. This issue is particularly acute in regions like Thailand, where a significant portion of MSW is improperly managed, increasing the environmental burden of leachate generation and discharge risks. Mature leachate is highly problematic, characterized by COD levels exceeding 20,000 mg/L, ammoniacal nitrogen (NH4+) above 2000 mg/L, and a critically low carbon-to-nitrogen (C/N) ratio [4].

Conventional biological treatment strategies, such as upflow anaerobic sludge blanket (UASB) reactors and anaerobic membrane bioreactors (AnMBRs), are effective at removing organic carbon from leachate, often achieving COD removal rates of 80–95%, but are ineffective for ammonium removal. This is because the low C/N ratio limits heterotrophic denitrification, and ammonium remains stable under anaerobic conditions [4,5,6]. These limitations highlight the necessity for alternative biological pathways for nitrogen removal from mature leachate.

To effectively treat wastewaters characterized by high nitrogen content and low carbon availability (i.e., a low C/N ratio), the anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) process has emerged as a superior alternative. The anammox process mediates the direct transformation of nitrite (NO2−) and ammonium (NH4+) into nitrogen gas (N2) under strictly anaerobic conditions (Equation (1)). This technology offers significant operational and economic advantages over conventional biological nitrogen removal (BNR), including minimal organic carbon requirements, lower energy consumption due to reduced aeration needs, and minimized sludge production [7,8]. These attributes make anammox an ideal and efficient solution for treating challenging mature landfill leachate.

NH4+ + 1.32NO2− + 0.66HCO3− + 0.13H+ → 0.066CH2O0.5N0.15 + 1.02N2 + 0.26NO3− + 2.03H2O

Within the broader framework of microbial nitrogen transformation pathways, anammox has become a key technology for sustainable wastewater treatment. Recent literature emphasizes that understanding the robustness of anammox systems to emerging chemical and particulate stressors is essential to support their reliable implementation in advanced treatment applications, particularly as wastewater matrices become increasingly complex [9].

However, the complexity of landfill effluent is further compounded by the prevalence of microplastics (MPs). MPs originate from the fragmentation of discarded plastics and have been detected in landfill waste, soil, and leachate [10,11]. MPs commonly found in Thai landfills include LDPE, PP, and PET, reflecting their dominance in packaging [12]. Of particular concern is the leaching of chemical additives from MPs, such as dibutyl phthalate (DBP), a known microbial inhibitor capable of disrupting metabolism in activated sludge systems [13,14]. Although recent studies have primarily focused on PVC microplastics, their findings cannot be directly extended to other polymer types because PVC is chlorine-rich and releases distinct toxic chlorinated leachates [15,16,17]. In contrast, LDPE and PP are non-chlorinated polymers but contain diverse additives that may leach into the environment and influence microbial processes in different ways. This gap highlights the need to evaluate both the particle-related and leachate-related risks of these widely occurring landfill plastics.

Despite increasing attention to MPs in wastewater systems, a critical knowledge gap remains regarding the effects of common landfill-derived polymers, particularly LDPE and PP MPs, on anammox biomass and the role of their associated chemical additives. Among these additives, dibutyl phthalate (DBP) is frequently detected in environmental compartments, including surface waters, sediments, treated wastewaters (sewage treatment plant effluents), sewage sludge, liquid manure, and landfill leachates [18,19,20]. Furthermore, the reported DBP concentrations in municipal landfill leachate worldwide typically range from <1 to 80 μg/L, with notably elevated levels observed in Asian regions, such as China and Thailand, where concentrations of up to 80 μg/L and 35.4 μg/L have been reported, respectively [19,20]. Variability among sites is largely attributed to differences in waste composition and plasticizer usage. Although environmental concentrations are generally low, landfill systems represent a continuous source of DBP due to the ease with which physically bound plasticizers are able to leach from plastic materials. Given that DBP is a known endocrine-disrupting compound with documented toxicity to microbial processes, its potential impact on biological nitrogen removal (BNR) remains insufficiently understood. Therefore, this study systematically investigates both the physical effects of LDPE and PP particles and the chemical effects of their leachates on anammox performance. By examining DBP-induced inhibition across a wide concentration range and comparing responses among suspended, attached, and granular growths biomass, this work addresses an important and largely unregulated aspect of wastewater treatment, providing insight into the vulnerability and resilience of anammox systems to LDPE and PP microplastic-associated contaminants in terms of nitrogen removal performance and specific anammox activity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometer

2.1.1. Migration Experiment

To minimize contamination, all the experimental procedures were performed exclusively with glassware; plastic or metal tools were avoided. All the glass containers and equipment were thoroughly rinsed with deionized (DI) water before use to ensure cleanliness. The test samples comprised plastic pellets measuring 0.3–0.45 cm. Prior to the experiment, original packaging contents were removed, and the pellets were thoroughly rinsed with DI water to eliminate any remaining residues. Following conditions based on Zimmermann, Bartosova [21], and relevant EU migration testing guidelines [22], the migration experiment involved immersing 3 g of plastic pellets in 20 mL of synthetic wastewater within sealed glass containers. These were then incubated in the dark at 35 ± 2 °C for 10 days to simulate potential leaching under both standard and anammox-relevant conditions. After the 10-day incubation period, the leachate solution was subjected to Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) for further analysis.

2.1.2. Solid-Phase Extraction Procedure for Plastic Extraction

To analyze leachable compounds from MPs, a modified QuEChERS (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe) method was employed. Initially, a 10 mL volume of sample was transferred to a 50 mL glass centrifuge tube. Subsequently, 10 mL of pre-chilled acetonitrile (ACN) was added, and the tube was immediately capped and shaken for 2 min to ensure thorough extraction. A pre-packaged QuEChERS salt mixture (4 g MgSO4, 1 g NaCl) was then added, and the mixture was vortexed vigorously for 2 min to induce phase separation and buffering. This mixture was then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min to separate the ACN layer. For cleanup, 10 mL of the ACN extract was transferred to a 50 mL centrifuge tube containing a dSPE mixture (1500 mg MgSO4, 500 mg C18), vortexed for 2 min, and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min to remove matrix interferences. Finally, the cleaned extract was directly transferred to a glass vial for subsequent analysis by Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GCMS). This adapted QuEChERS protocol, based on established methods [23,24], provided a rapid and effective means of preparing microplastic leachate for detailed chemical analysis.

2.1.3. GC Separation Conditions

Volatile and semi-volatile organic compounds were separated using an Agilent 7890A gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with an HP-5 MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 µm film thickness). Helium was employed as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 1 mL/min. The column temperature was programmed as follows: initial temperature of 65 °C held for 1 min, followed by a ramp rate of 5 °C/min to a final temperature of 290 °C, which was held for 8 min. The injector and transfer line temperatures were set at 250 °C and 280 °C, respectively. A 1 µL injection volume was used. For the identification of compounds in the microplastic leachate extracts, a pulsed splitless injection mode was employed (25 psi for 1.1 min, splitless time 1 min). This approach, which allows for the sensitive identification of trace compounds, was adapted from the methodology used in recent studies analyzing organic pollutants via GC-MS [25].

2.2. Culture and Activity of Anammox Bacteria

2.2.1. Synthetic Wastewater Composition and Preparation

A synthetic wastewater was prepared to simulate anammox-relevant conditions, containing ammonium-nitrogen and nitrite-nitrogen at a molar ratio of 1:1.3. The formulation followed the approach reported by Kaewyai, Noophan [26], which was modified from Isaka, Date [27]. To achieve this ratio, 990 mg of ammonium sulfate ((NH4)2SO4) and 1287 mg of sodium nitrite (NaNO2) were dissolved per liter of deionized water, resulting in concentrations of 210 mg/L NH4+-N and 273 mg/L NO2−-N. In addition to the nitrogen sources, the synthetic wastewater contained essential micro-nutrients, buffering agents, and trace elements to support microbial activity, as shown in Table 1. All the components were dissolved in deionized water, and the solution was freshly prepared prior to use to ensure stability and concentration accuracy.

Table 1.

Supporting nutrients and trace elements in synthetic wastewater.

2.2.2. Specific Anammox Activity (SAA)

Specific anammox activity (SAA) was determined by measuring the hourly removal rates of ammonium-nitrogen (NH4+-N) and nitrite-nitrogen (NO2−-N). Total nitrogen (TN) removal, calculated as the sum of NH4+-N and NO2−-N, was plotted against reaction time. The slope of the linear portion of this plot, representing the nitrogen removal rate, was then normalized to anammox biomass, expressed as volatile suspended solids (VSS), as shown in Equation (2).

2.3. Experimental Setup

2.3.1. Short-Term Inhibition of Anammox Activity by DBP

A stock solution of dibutyl phthalate (DBP; 99%, Sigma-Aldrich, Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA) was prepared at 200 mg/L and diluted with synthetic wastewater to obtain working solutions at the target concentrations. For each test condition, 10 mL of anammox culture was transferred into a 100 mL serum bottle, after which the appropriate DBP working solution was added to achieve a final working volume of 100 mL. This configuration produced reactors containing 0, 1, 5, 25, 50, 75, and 100 mg/L DBP. All the reactors were incubated under anaerobic conditions. Nitrogen removal efficiency and the corresponding inhibition percentage were quantified at 5 h and 24 h to assess the short-term impact of DBP on anammox activity. The inhibition calculation was performed using Equation (3).

2.3.2. Extended Exposure of Anammox Biomass to LDPE and PP Microplastics

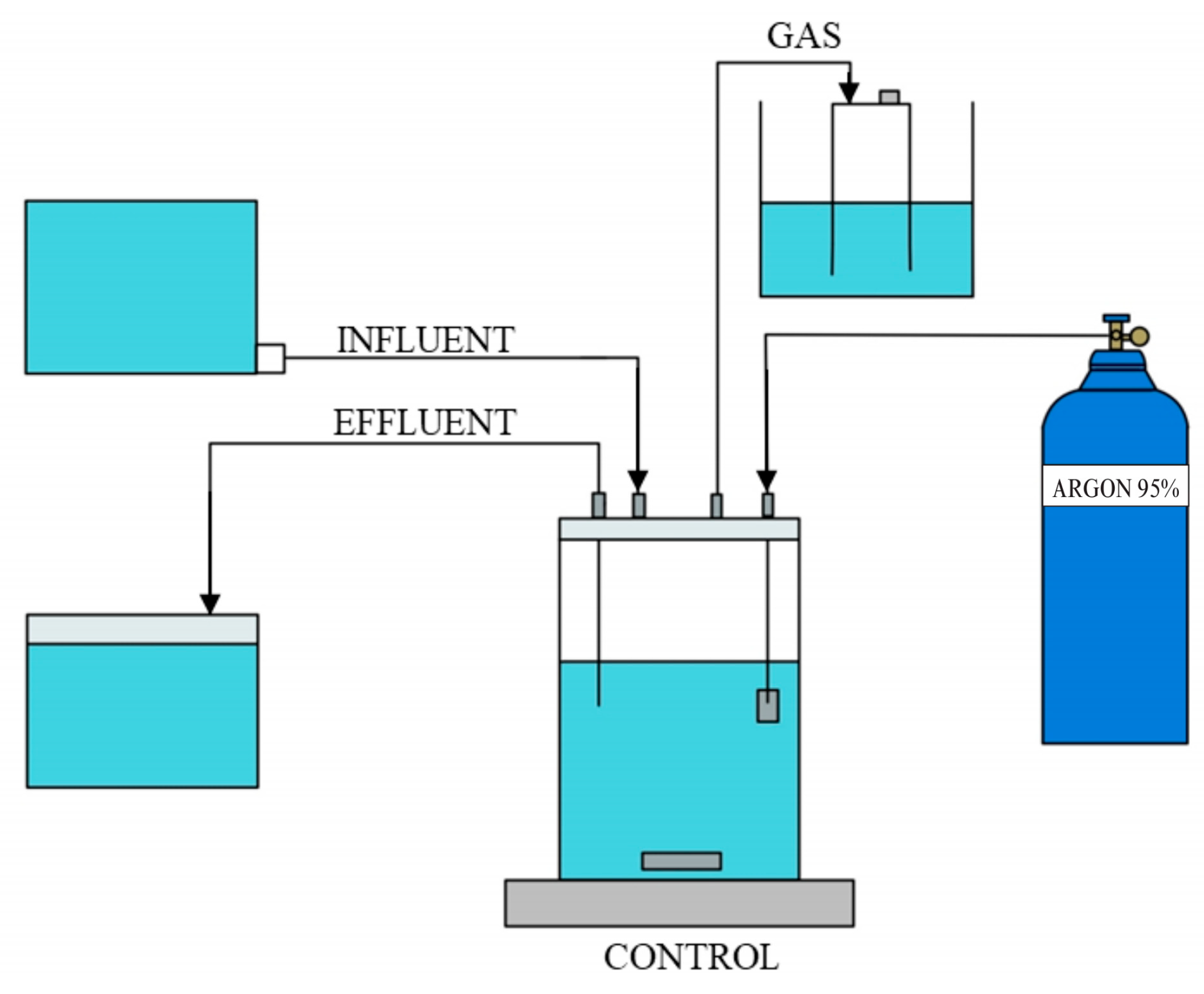

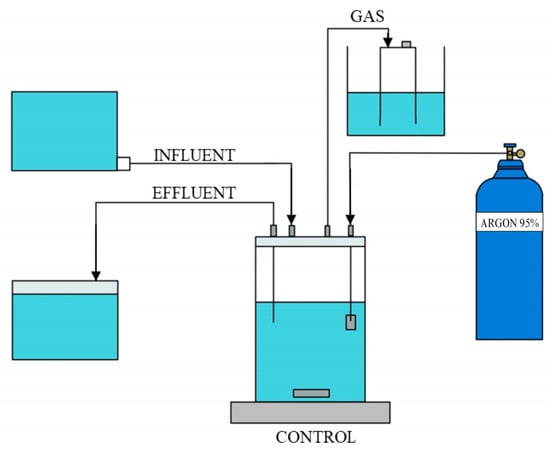

Anaerobic sequencing batch reactors (ASBRs), as shown in Figure 1, were used for long-term cultivation of anammox culturing. Each reactor was inoculated with biomass adjusted to 0.8–1.2 g VSS/L and operated using a 24 h SBR cycle consisting of a 20 min fill, 23 h reaction phase with continuous mixing, 25 min settling, and 15 min decant phase. Strict anaerobic conditions were maintained by flushing the reactors with a gas mixture of 95% argon and 5% carbon dioxide to remove dissolved oxygen. All the reactors were operated in the dark and maintained at a temperature of 37 ± 2 °C.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the anaerobic sequencing batch reactor (ASBR) setup used for anammox cultivation.

In this study, low-density polyethylene (LDPE) microplastics supplied by Siam Plastic and polypropylene (PP) microplastics provided by PSM Plasitech (PSM Plasitech Ltd., Part., Nonthaburi, Thailand) were used. Both polymers were tested in two particle-size classes: approximately 4.75 mm and 0.5 mm. The microplastics were added to the reactors at 0.5 g/L, which is higher than typical environmental levels, to ensure that any potential effects on anammox performance could be clearly evaluated under controlled laboratory conditions.

2.4. Analytical Methods

Ammonia concentrations in the leachate samples were determined using a distillation-based method with a VAPODEST distillation system (C. Gerhardt GmbH & Co. KG, Königswinter, Germany) following standard protocols for water and wastewater analysis. The samples were distilled under alkaline conditions, and the released ammonia was captured in boric acid and titrated with standardized sulfuric acid [28,29]. Nitrite levels were measured spectrophotometrically at 543 nm using the colorimetric method involving sulfanilamide and N-(1-naphthyl) ethylenediamine dihydrochloride (NED), which reacts with nitrite to form a pink azo dye under acidic conditions. Absorbance was read at 543 nm, and concentrations were quantified using a calibration curve prepared from sodium nitrite standards [29].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Identification of Leachates from LDPE and PP

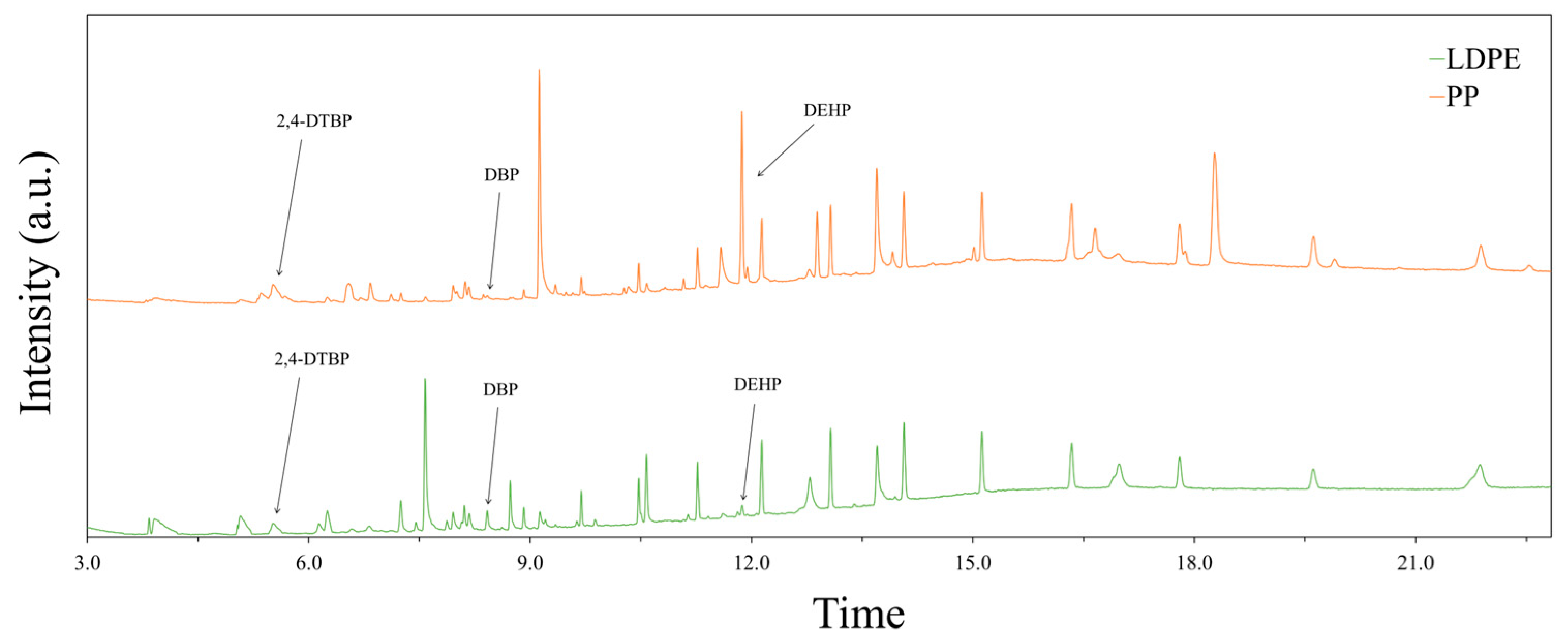

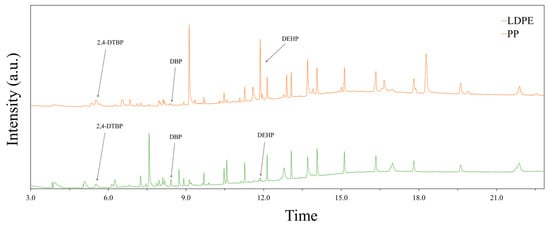

A non-targeted chemical analysis using scan mode, as described in Section 2.1.3, was performed on the LDPE and PP extracts. This analysis revealed a diverse array of compounds, with 31 putatively identified in the LDPE leachates and 37 in the PP leachates. Eight compounds were common to both polymers, including various plastic additives such as plasticizers, lubricants, antioxidants, and other functional additives used in polymer processing. Among these, three chemicals, 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol (2,4-DTBP), dibutyl phthalate (DBP), and bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP), were highlighted due to their well-documented environmental toxicity and potential impacts on microbial communities. The full GC–MS spectra are shown in Figure 2, with the peaks corresponding to these three compounds clearly indicated.

Figure 2.

Identification of selected chemical leachates from LDPE and PP extracts using GC–MS.

One leachate detected from both LDPE and PP was dibutyl phthalate (DBP), a commonly used plasticizer. The quantity and profile of leachates were found to be influenced by the solvent used and the duration of elution, indicating that environmental conditions could significantly affect the release of such chemicals. The presence of DBP is particularly concerning due to its known inhibitory effects on microbial activity. For example, Jianlong [13] reported that even at low concentrations, DBP negatively impacted the performance of activated sludge systems. Specifically, the study showed a linear increase in inhibition of chemical oxygen demand (COD) removal efficiency with increasing DBP concentrations up to 100 mg/L.

These findings highlight the potential for DBP to affect microbial processes. To investigate this, a short-term exposure study was conducted to evaluate the effects of DBP on anammox activity across a range of concentrations, as described in the following section.

3.2. Short-Term Inhibition by DBP on Granular Anammox

The adsorption of DBP by different anammox biomass types was evaluated by dosing 100 mg/L DBP into reactors containing suspended, attached, and granular sludge. Immediately after mixing, the residual DBP concentration in the liquid phase of the suspended sludge reactor was 73.82 mg/L, whereas it was significantly lower in the attached (10.08 mg/L) and granular (7.58 mg/L) reactors, indicating enhanced DBP removal compared to suspended sludge by the latter (Table 2). After 24 h, the DBP concentrations further decreased to 11.02 mg/L in the suspended sludge and approximately 3 mg/L in the attached and granular biomass. This pattern indicates that the attached and granular biomass efficiently adsorbed DBP, likely due to the presence of extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs), which are predominantly proteinaceous (>60%) with low carbohydrate content (~7%) and are known to function as natural biosorbents [30,31]. In contrast, the suspended sludge, which lacks a structured EPS matrix, showed limited adsorption capacity. Granular anammox was, therefore, selected for subsequent experiments because of its high adsorption potential, compact structure, robust performance, superior settleability, and greater tolerance to toxic compounds. Additionally, aerobic granular sludge forms spontaneously without carrier materials, reducing operational costs [32,33]. These findings informed the design of the following study, which examined the effects of varying DBP concentrations on granular anammox activity.

Table 2.

Residual DBP concentration (mg/L) in different anammox biomass types after short-term exposure to 100 mg/L DBP.

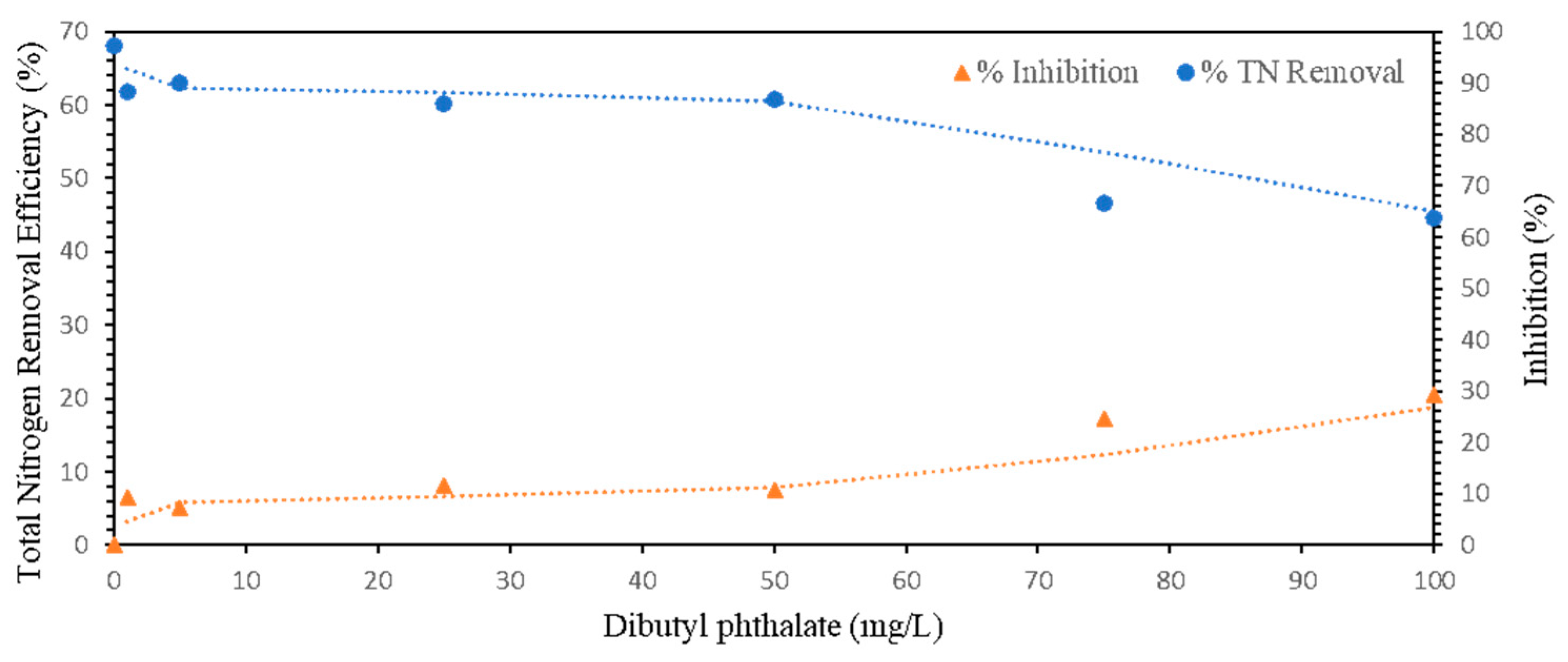

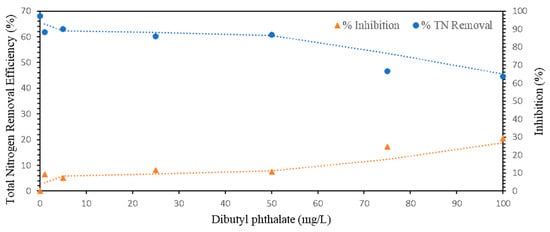

As demonstrated in Section 3.1, dibutyl phthalate (DBP) was identified as a leachate component from both LDPE and PP microplastics. To assess its potential inhibitory effects on anammox activity, ammonia and nitrite removal efficiencies were evaluated using granular anammox biomass exposed to a range of DBP concentrations (0, 1, 5, 25, 50, 75, and 100 mg/L). While the reported DBP concentrations in landfill leachate typically range from <1 to 80 μg/L [19,20], a significantly higher concentration range (up to 100 mg/L) was selected for this study. This ‘shock loading’ approach was intentionally designed to determine the upper toxicity threshold of the anammox biomass and to evaluate its resilience against extreme fluctuations or potential long-term accumulation of DBP within the sludge matrix. Within the first 5 h, total nitrogen removal efficiency declined progressively with increasing DBP concentrations, resulting in inhibition rates ranging from 9.41% to 29.37%. Specifically, nitrogen removal efficiencies decreased from 97.40% in the control to 63.70% at 100 mg/L DBP, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Effect of DBP concentration on TN removal efficiency and inhibition in granular anammox biomass.

Interestingly, after 24 h, the inhibitory effect was substantially reversed. All the reactors, including those exposed to the highest DBP concentration, recovered to near-baseline nitrogen removal performance. At 100 mg/L, inhibition dropped from 29.37% to 3.28%, suggesting that the observed effect was transient rather than a result of permanent toxicity.

The recovery of granular anammox activity is primarily attributed to adsorption, as confirmed by the rapid decrease in liquid-phase DBP concentrations (Table 2). This physical sequestration by the biomass matrix and EPS reduces the bioavailable fraction of DBP, mitigating its immediate inhibitory effect. Additionally, partial biodegradation by coexisting heterotrophic bacteria may have played a secondary role. Although anammox bacteria are unable to degrade DBP directly, previous research has confirmed that heterotrophic consortia within anaerobic sludge can mineralize phthalates under anaerobic or denitrifying conditions [34,35,36]. Therefore, the observed recovery was likely driven by the combined effects of physical sequestration and potential biological degradation.

Beyond adsorption-driven sequestration, the resilience observed in anammox biomass may also relate to the interconnected nature of microbial nitrogen transformation pathways under oxygen-limited conditions. Previous studies have demonstrated that partial aerobic ammonium oxidation can supply nitrite to anammox bacteria, while microbial growth and inorganic carbon assimilation may lead to the formation of EPS and soluble microbial products (SMPs), which are commonly associated with biomass stability and buffering capacity in anammox-based systems [37,38]. Although EPS production and SMP dynamics were not directly quantified in this study, such mechanisms have been widely reported to enhance resistance to transient chemical disturbances by reducing mass transfer of toxic compounds and stabilizing microbial aggregates. In addition, cooperative metabolic interactions between anammox bacteria and coexisting heterotrophic or denitrifying microorganisms may have contributed to the rapid recovery of nitrogen removal following DBP exposure. For example, denitrifying bacteria such as Thauera spp. have been shown to consume SMPs released by anammox cultures, store carbon intracellularly as poly-β-hydroxybutyrate, and facilitate simultaneous nitrate reduction, thereby creating favorable conditions for anammox activity recovery [39]. While microbial community composition was not analyzed in the present study, these literature-reported interactions may partially explain the transient nature of DBP inhibition observed in granular anammox systems.

These observations provided the rationale for the subsequent long-term study in which LDPE and PP microplastic particles were introduced to different anammox biomass types to investigate their potential effects on nitrogen removal performance.

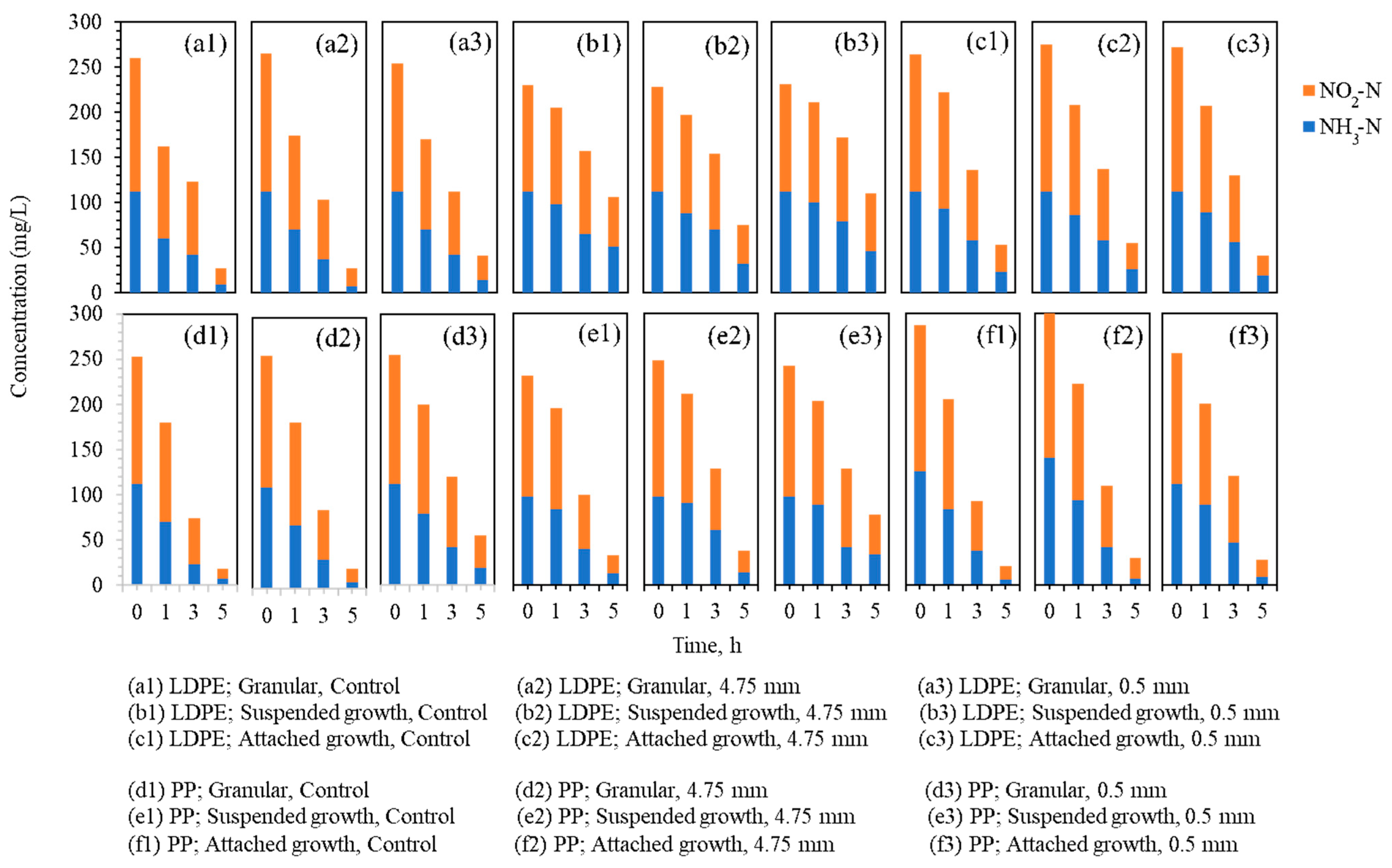

3.3. Effects of LDPE and PP Microplastics on Anammox Activity

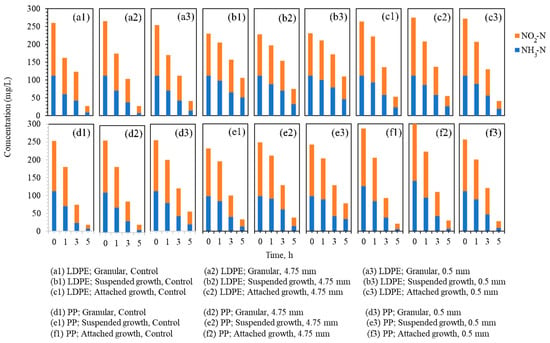

The changes in NH3-N and NO2−-N concentrations during the 5 h anammox reaction under LDPE and PP exposure are shown in Figure 4. Figure 4(a1–a3) illustrate the nitrogen profiles of the granular biomass with the LDPE particles, Figure 4(b1–b3) present the suspended biomass with the LDPE particles, and Figure 4(c1–c3) show the attached biomass with the LDPE particles. Similarly, Figure 4(d1–d3) display the granular biomass with the PP particles, Figure 4(e1–e3) show the suspended biomass with the PP particles, and Figure 4(f1–f3) present the attached biomass with the PP particles.

Figure 4.

Changes in NH3-N and NO2−-N concentrations during 5 h anammox activity tests under LDPE and PP microplastic exposure across three biomass types.

Within each biomass type, the LDPE- and PP-dosed reactors exhibited nitrogen conversion trends similar to their respective controls. This indicates that the presence of microplastics did not cause immediate or strong inhibition of anammox performance during the 5 h monitoring period. However, in several reactors containing 0.5 mm particles, particularly in suspended growth (Figure 4(b3,d3,e3)), a noticeable reduction in nitrogen removal efficiency was observed when compared with reactors containing 4.75 mm particles. This suggests that particle size may influence reactor performance, with smaller particles potentially exerting a more pronounced effect.

These observations partially align with the adsorption trends reported in Section 3.2, where the suspended biomass exhibited the lowest capacity for DBP adsorption. The distinct response observed between the biomass types suggests that physical architecture and EPS play a decisive role in mitigating leachate toxicity. Suspended sludge, characterized by a loose floccose structure and low EPS density, lacks a significant diffusion barrier [40]. This lack of structural protection results in higher susceptibility to chemical disturbances, as toxic leachates can penetrate the microbial cells almost instantly. In contrast, the dense EPS matrix in granular and attached biomasses provides a mass transfer resistance that sequesters hydrophobic toxins like DBP, preventing them from reaching the sensitive internal anammox population [41].

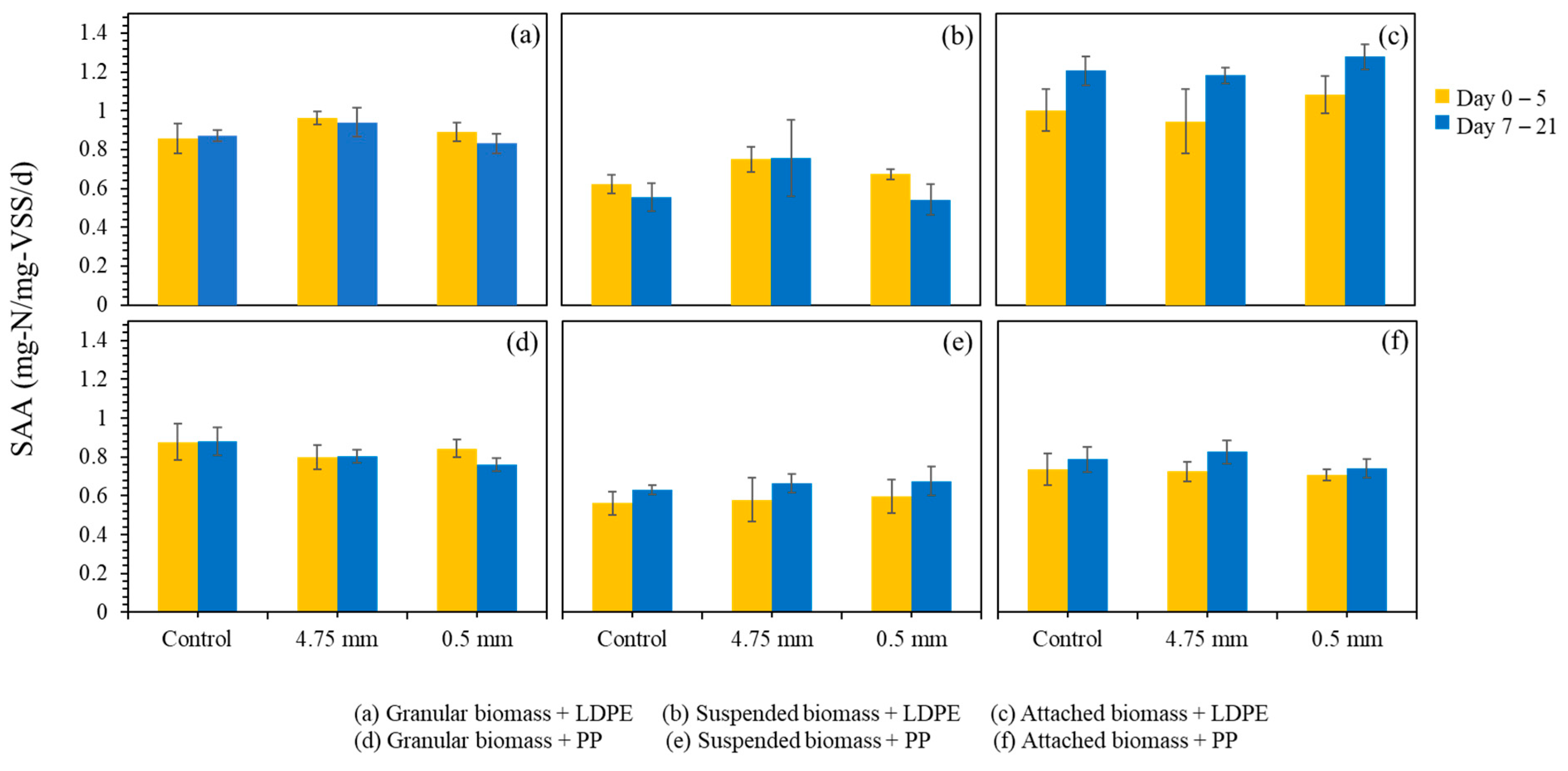

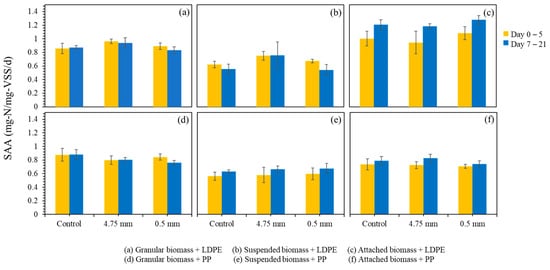

While the nitrogen profiles provide an immediate indication of how each biomass type responds to microplastic exposure, a clearer understanding of potential inhibition or resilience requires evaluation of specific anammox activity (SAA) over a longer operational period. Figure 5 presents the SAA values across multiple days of exposure to LDPE and PP microplastics. In the suspended growth system dosed with LDPE, the SAA values ranged from 0.43 to 0.71 mg-N/mg-VSS/d, which was comparable to the control range of 0.45 to 0.66 mg-N/mg-VSS/d. The average SAA values during days 0 to 5 were 0.67 mg-N/mg-VSS/d for the LDPE-dosed group and 0.62 mg-N/mg-VSS/d for the control. After day 5, slight declines were observed in both groups, but the overall patterns were similar, indicating no clear inhibitory effect of LDPE on suspended anammox activity.

Figure 5.

Specific anammox activity (SAA) of different biomass types during microplastic exposure. (a–c) represent SAA changes under LDPE dosing, and (d–f) under PP dosing. Error bars represent one standard deviation from the mean.

In the attached growth system, LDPE exposure did not cause adverse effects. Instead, the LDPE-dosed group exhibited slightly higher SAA values compared with the control. The initial average SAA values increased from 1.00 mg-N/mg-VSS/d in the control to 1.08 mg-N/mg-VSS/d in the LDPE-dosed system during days 0 to 5, and both groups showed performance improvements after day 5. These results suggest that the LDPE particles did not hinder and may have mildly stimulated attached anammox activity, possibly due to increased mixing effects or particle-supported micro-habitats.

For the granular biomass, both the LDPE control and dosed groups exhibited stable SAA values. The average SAA values during days 0 to 5 were 0.86 mg-N/mg-VSS/d in the control and 0.89 mg-N/mg-VSS/d in the LDPE-dosed group. After day 5, minor fluctuations were observed, but no substantial differences occurred between the two conditions. The compact structure of anammox granules likely contributed to their stable performance.

Similar trends were observed with PP MPs. In the suspended growth system, the control group had SAA values between 0.49 and 0.65 mg-N/mg-VSS/d, averaging 0.56 mg-N/mg-VSS/d in the first 5 days and increasing to 0.63 mg-N/mg-VSS/d afterward. The dosed group showed a slightly broader range (0.46–0.77 mg-N/mg-VSS/d), with average values increasing from 0.60 to 0.68 mg-N/mg-VSS/d over the same periods. These data suggest no significant suppression of anammox activity by PP MPs, and even a slight increase in SAA compared to the control.

In the attached growth system with PP MPs, the control SAA ranged from 0.65 to 0.86 mg-N/mg-VSS/d, averaging 0.74 mg-N/mg-VSS/d during the first 5 days and rising to 0.79 mg-N/mg-VSS/d after. The dosed group exhibited similar results, ranging from 0.66 to 0.80 mg-N/mg-VSS/d, with an average of 0.71 mg-N/mg-VSS/d initially and 0.74 mg-N/mg-VSS/d after 5 days. These small differences further support the conclusion that PP MPs do not have a detrimental effect on attached anammox activity.

In the granular growth system, control values for SAA varied from 0.75 to 1.01 mg-N/mg-VSS/d, with a consistent average of 0.88 mg-N/mg-VSS/d across the full duration. The PP-dosed samples ranged from 0.72 to 0.88 mg-N/mg-VSS/d, with averages decreasing slightly from 0.84 mg-N/mg-VSS/d to 0.76 mg-N/mg-VSS/d over the test period. Although a slight decline was observed, the variation remained within the normal operational range, indicating a negligible impact from PP MPs.

Although PVC microplastics have been shown to significantly inhibit anammox activity due to chlorine-rich leachates [42], no inhibition was observed in this study for LDPE and PP. Considering that DBP exhibited noticeable inhibition only at high concentrations in the independent assays (100 mg/L), the amount of DBP that could reasonably leach from the added LDPE and PP particles during the experimental period is expected to be far below this inhibitory threshold. This supports the observation that microplastic dosing did not suppress anammox performance, as the leachate-derived DBP levels were likely insufficient to exert measurable toxicity. This interpretation is also consistent with the trends reported in sludge anaerobic digestion [43], where low concentrations of synthetic polymers can occasionally support microbial processes, while higher concentrations or toxic leachates tend to impair system performance.

Combined with the findings in Section 3.2, these results suggest that the primary concerns related to LDPE and PP lie not in the direct physical interactions of the particles with anammox biomass, but in their potential to release leachates under specific environmental conditions. Therefore, detailed chemical screening, as presented earlier in this paper, is essential for evaluating the chemical pathways that may influence anammox performance over longer periods.

4. Conclusions

This study investigated the effects of LDPE and PP microplastics (MPs) and their associated chemical leachates, particularly dibutyl phthalate (DBP), on anammox activity across suspended, attached, and granular biomass systems. The results demonstrated that direct exposure to LDPE and PP MPs, at the tested concentrations and timeframes, did not cause significant inhibition of specific anammox activity (SAA) in any biomass configuration. In some cases, slight increases in activity were observed, suggesting that the physical presence of these MPs may not be inherently toxic to anammox bacteria and that anammox communities may exhibit a degree of tolerance to MP exposure.

Non-targeted chemical analysis revealed the presence of several plastic-derived leachates, including DBP, in both the LDPE and PP samples. Although the MPs themselves did not show measurable toxicity, a separate DBP exposure experiment demonstrated concentration-dependent inhibition of nitrogen removal in the granular anammox biomass. However, the inhibition was largely reversible within 24 h. This rapid recovery indicates that anammox biomass can tolerate transient DBP exposure, likely due to adsorption by extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs) and possible biodegradation by coexisting heterotrophic microorganisms. Therefore, both attached growth and granular systems are strongly recommended for field application, given their superior performance compared to suspended growth systems.

Overall, these findings emphasize the need to distinguish between the physical effects of MPs and the chemical risks associated with their leachates. While the LDPE and PP MPs appeared benign within the experimental period, their ability to release inhibitory compounds such as DBP suggests a latent risk to biological nitrogen removal processes. Additionally, although anammox showed short-term tolerance to both MPs and DBP in this study, the long-term ecological implications remain uncertain. Extended evaluations under variable environmental conditions and chronic exposure scenarios are required to fully assess cumulative impacts on anammox-driven treatment systems.

Author Contributions

Initial idea and conceptualization, P.N. and C.-W.L.; analysis and methodology, T.S. and Y.K.; formal analysis and investigation, Y.K.; writing—original draft preparation, P.N. and C.-W.L.; writing—review and editing, P.N. and C.-W.L.; visualization and supervision; P.N.; project administration, P.N. and C.-W.L.; funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is mainly supported by funding from Kasetsart University through the Graduate School of Fellowship Program. Also, there is partial funding from the Faculty of Engineering, Kasetsart University, Bangkok, Thailand, and the Appropriate Technologies for Waste Reuse and Management Research Unit, Naresuan University, Phitsanulok, Thailand.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

This research is funded by Kasetsart University through the Graduate School Fellowship Program. The authors want to thank you, Faculty of Engineering, Kasetsart University, Bangkok, Thailand, for valuable assistance through this research project. Finally, the authors would like to express their gratitude to the Appropriate Technologies for Waste Reuse and Management Research Unit, Naresuan University, Phitsanulok 65000, Thailand, for their great support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MPs | Microplastics |

| LDPE | Low-Density Polyethylene |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| Anammox | Anaerobic Ammonium Oxidation |

| SAA | Specific Anammox Activity |

| GC-MS | Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry |

| DBP | Dibutyl Phthalate |

| MSW | Municipal Solid Waste |

| COD | Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| PET | Polyethylene Terephthalate |

| PVC | Polyvinyl Chloride |

| EU | European Union |

| SPE | Solid-Phase Extraction |

| EPS | Extracellular Polymeric Substances |

References

- Golwala, H.; Saha, B.; Zhang, X.; Bolyard, S.C.; He, Z.; Novak, J.T.; Deng, Y.; Brazil, B.; DeOrio, F.J.; Iskander, S.M. Advancement and challenges in municipal landfill leachate treatment–the path forward! ACS EST Water 2022, 2, 1289–1300. [Google Scholar]

- Golwala, H.; Zhang, X.; Iskander, S.M.; Smith, A.L. Solid waste: An overlooked source of microplastics to the environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 769, 144581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, C.; Al Hageh, C.; Korfali, S.; Khnayzer, R.S. Municipal leachates health risks: Chemical and cytotoxicity assessment from regulated and unregulated municipal dumpsites in Lebanon. Chemosphere 2018, 208, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, L.; Tan, F.; Wu, D. Treatment of landfill leachate using activated sludge technology: A review. Archaea 2018, 2018, 1039453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, X.H.; Cui, S.; Ren, Y.X.; Yu, J.; Chen, N.; Xiao, Q.; Guo, L.K.; Wang, R.H. Simultaneous removal of nitrogen and phosphorous by heterotrophic nitrification-aerobic denitrification of a metal resistant bacterium Pseudomonas putida strain NP5. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 285, 121360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.-Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Liu, J.-Q.; Yan, C.-C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.-L. Synergistic enhancement of UASB reactor for leachate treatment using Fe2O3 nanomodified pumice and ozone oxidation. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 497, 154891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Wang, L.; Cheng, L.; Yang, W.; Gao, D. Nitrogen removal from mature landfill leachate via anammox based processes: A review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, H.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Peng, Y. Anammox-mediated municipal solid waste leachate treatment: A critical review. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 361, 127715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaaban, M.; Zhou, K.; Asgari Lajayer, B.; Wu, L.; Younas, A.; Wu, Y. Advancements in Microbial Nitrogen Pathways for Sustainable Wastewater Treatment. Water 2025, 17, 3409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.S.; Wang, H.; Luster-Teasley, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, R. Microplastics in landfill leachate: Sources, detection, occurrence, and removal. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 2023, 16, 100256. [Google Scholar]

- Kazour, M.; Terki, S.; Rabhi, K.; Jemaa, S.; Khalaf, G.; Amara, R. Sources of microplastics pollution in the marine environment: Importance of wastewater treatment plant and coastal landfill. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 146, 608–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puthcharoen, A.; Leungprasert, S. Determination of microplastics in soil and leachate from the landfills. Thai Environ. Eng. J. 2019, 33, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Jianlong, W. Effect of di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP) on activated sludge. Process Biochem. 2004, 39, 1831–1836. [Google Scholar]

- Ziembowicz, S.; Kida, M.; Koszelnik, P. Removal of dibutyl phthalate (DBP) from landfill leachate using an ultrasonic field. Desalination Water Treat. 2018, 117, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateia, M.; Kanan, A.; Karanfil, T. Microplastics release precursors of chlorinated and brominated disinfection byproducts in water. Chemosphere 2020, 251, 126452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Li, Z.; Liu, D.; Song, K. Evaluation of partial nitrification efficiency as a response to cadmium concentration and microplastic polyvinylchloride abundance during landfill leachate treatment. Chemosphere 2020, 247, 125903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ya, T.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X. Responses of microbial interactions to polyvinyl chloride microplastics in anammox system. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 440, 129807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromme, H.; Küchler, T.; Otto, T.; Pilz, K.; Müller, J.; Wenzel, A. Occurrence of phthalates and bisphenol A and F in the environment. Water Res. 2002, 36, 1429–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wowkonowicz, P.; Kijeńska, M. Phthalate release in leachate from municipal landfills of central Poland. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174986. [Google Scholar]

- Boonyaroj, V.; Chiemchaisri, C.; Chiemchaisri, W.; Theepharaksapan, S.; Yamamoto, K. Toxic organic micro-pollutants removal mechanisms in long-term operated membrane bioreactor treating municipal solid waste leachate. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 113, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, L.; Bartosova, Z.; Braun, K.; Oehlmann, J.R.; Völker, C.; Wagner, M. Plastic products leach chemicals that induce in vitro toxicity under realistic use conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 11814–11823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. European Green Deal: Putting an End to Wasteful Packaging, Boosting Reuse and Recycling; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022.

- Anastassiades, M.; Lehotay, S.J.; Štajnbaher, D.; Schenck, F.J. Fast and easy multiresidue method employing acetonitrile extraction/partitioning and “dispersive solid-phase extraction” for the determination of pesticide residues in produce. J. AOAC Int. 2003, 86, 412–431. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, A.A.; Fagnani, E.; Cristale, J. A modified QuEChERS method for determination of organophosphate esters in milk by GC-MS. Chemosphere 2023, 334, 138974. [Google Scholar]

- Elseblani, R.; Cobo-Golpe, M.; Godin, S.; Jimenez-Lamana, J.; Fakhri, M.; Rodríguez, I.; Szpunar, J. Study of metal and organic contaminants transported by microplastics in the Lebanese coastal environment using ICP MS, GC-MS, and LC-MS. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 887, 164111. [Google Scholar]

- Kaewyai, J.; Noophan, P.L.; Cruz, S.G.; Okabe, S. Influence of biochar derived from sugarcane bagasse at different carbonization temperatures on anammox granular formation. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2023, 185, 105678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaka, K.; Date, Y.; Sumino, T.; Yoshie, S.; Tsuneda, S. Growth characteristic of anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing bacteria in an anaerobic biological filtrated reactor. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006, 70, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VAPODEST—Distillation Systems: Product Brochure and Manual. 2022. Available online: https://www.gerhardt.de/en/products/distillation-systems-vapodest/ (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Rice, E.W.; Baird, R.B.; Eaton, A.D.; Clesceri, L.S. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA; American Water Works: New Jersey, NJ, USA; Water Environment Federation: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lotti, T.; Carretti, E.; Berti, D.; Martina, M.R.; Lubello, C.; Malpei, F. Extraction, recovery and characterization of structural extracellular polymeric substances from anammox granular sludge. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 236, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliaccia, B.; Carretti, E.; Severi, M.; Berti, D.; Lubello, C.; Lotti, T. Heavy metal biosorption by Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) recovered from anammox granular sludge. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 126661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamza, R.; Rabii, A.; Ezzahraoui, F.-z.; Morgan, G.; Iorhemen, O.T. A review of the state of development of aerobic granular sludge technology over the last 20 years: Full-scale applications and resource recovery. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2022, 5, 100173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nancharaiah, Y.; Reddy, G.K.K. Aerobic granular sludge technology: Mechanisms of granulation and biotechnological applications. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 247, 1128–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, B.; Liao, C.; Yuan, S. Anaerobic degradation of diethyl phthalate, di-n-butyl phthalate, and di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate from river sediment in Taiwan. Chemosphere 2005, 58, 1601–1607. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M.-Z.; Ma, Y.-W.; Wang, Y.; Wan, J.-Q.; Zhang, H.-P. The fate of di-n-butyl phthalate in a laboratory-scale anaerobic/anoxic/oxic wastewater treatment process. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 7767–7772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Liu, C.; Liao, C.; Chang, B. Occurrence and microbial degradation of phthalate esters in Taiwan river sediments. Chemosphere 2002, 49, 1295–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Haaijer, S.C.; Op den Camp, H.J.; van Niftrik, L.; Stahl, D.A.; Könneke, M.; Rush, D.; Sinninghe Damsté, J.S.; Hu, Y.Y.; Jetten, M.S. Mimicking the oxygen minimum zones: Stimulating interaction of aerobic archaeal and anaerobic bacterial ammonia oxidizers in a laboratory--scale model system. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 14, 3146–3158. [Google Scholar]

- Rittmann, B.E.; Stilwell, D.; Ohashi, A. The transient-state, multiple-species biofilm model for biofiltration processes. Water Res. 2002, 36, 2342–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; He, J. Partnering of anammox and denitrifying bacteria benefits anammox’s recovery from starvation and complete nitrogen removal. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 815, 152696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, B.-J.; Yu, H.-Q. Mathematical modeling of aerobic granular sludge: A review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2010, 28, 895–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Jin, Y.; Zhou, D.; Liu, L.; Huang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Y. A review of the role of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) in wastewater treatment systems. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Su, C.; Chen, Y.; Xian, Y.; Hui, X.; Ye, Z.; Chen, M.; Zhu, F.; Zhong, H. Influence of biodegradable polybutylene succinate and non-biodegradable polyvinyl chloride microplastics on anammox sludge: Performance evaluation, suppression effect and metagenomic analysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 401, 123337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Chen, Z.; Wei, L.; Chen, J.; He, Y.; Liang, B.; Chen, S.; Lu, Y.; Su, C. A comprehensive review of synthetic polymers stress on sludge anaerobic digestion resource and value: Current status, mechanisms, and future potential. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 203, 107948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.