Abstract

Arid and semi-arid regions are highly vulnerable to drought and depend heavily on rainfed agriculture. To minimize the impact of drought, a transition from crisis management to risk management is necessary, which requires a comprehensive risk assessment that accounts for not only drought hazard but also drought vulnerability and population exposure. However, integrated studies that account for socio-economic, agricultural, demographic, and climate factors are currently lacking in Iran. The objective of this study is to comprehensively assess the spatio-temporal changes in drought risk from 2000 to 2019 across Iran. We used the standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index (SPEI) and multiple socio-economic and demographic data to compute drought risk. In particular, we used the SPEI to map drought hazard, an analytical hierarchical process method to assess drought vulnerability, and population density data to compute population exposure. Drought risk increased in 57% of the area of Iran, mainly in the northwest, west, and central regions, at a rate of up to 10% per year. In 21% of the area of Iran, drought risk declined by up to 10% per year, predominantly in the northern and southern regions of the Alborz Mountains, encompassing the provinces of Tehran, Gilan, Mazandaran, and Khorasan Razavi. Our results show that the spatial patterns of drought risk vary across Iran and are modulated by the interaction between climatic and socio-economic factors. The results of this study provide useful information for drought risk management and intervention in Iran.

1. Introduction

Drought is one of the most common and complicated natural hazards in the world, affecting more than half of the Earth’s surface every year [1]. The percentage of the world’s territory afflicted by severe drought has increased significantly, more than doubling between the 1970s and the early 2000s, according to analyses performed by the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) [2]. This rise aligns with subsequent assessments that indicate the frequency and severity of droughts are continuing to rise on a worldwide scale [3,4]. In this research, drought is viewed as a long-term decline in precipitation that decreases water availability and creates stress across ecological, agricultural, and social sectors [5,6]. Drought plays a major role in shaping economic outcomes and poses serious challenges to food and environmental security [7]. Population growth and agricultural land expansion are leading to increased water consumption worldwide, exacerbating the impact of droughts. The considerable economic costs and social vulnerability issues associated with drought have prompted a heightened focus on drought vulnerability.

Three closely related factors need to be considered when estimating the likelihood of drought occurrence. The first, drought hazard, is a measure of the frequency and severity of droughts. The second, exposure, describes the ecosystems, infrastructure, and people who live in drought-affected areas. Vulnerability, the third factor, characterizes the degree to which these exposed systems are susceptible to harm and their resilience in the face of stress [8,9,10,11,12].

The fundamental components of the conceptual framework for understanding risk are hazard, exposure, and vulnerability, which show how various elements interact and compound to produce overall impact [13].

Former drought studies mainly used various methodological approaches, presenting valuable insights as well as notable limitations. Most studies focused mainly on drought hazard, indicating drought frequency and severity, and did not cover socioeconomic factors to shape the impacts. Although combining drought hazards, exposures, and vulnerabilities represent a more comprehensive drought risk assessment, such studies are rare at national scales and in limited data regions. These limitations underscore the necessity for a dynamic, spatio-temporal framework to capture the evolving nature of drought risk.

Less developed regions are generally considered more susceptible to drought, given their constrained capacity for adaptation and dependence on agricultural and natural resource-driven economies, which are markedly affected by the consequences of climate change [9,14,15,16].

The economic effects of drought are especially notable in metropolitan nations that depend heavily on water resources, while the social consequences are most severe in countries facing food insecurity, which rely on subsistence and primary agricultural activities [9,17,18,19,20]. Consequently, regions with underdeveloped economies are inadequate.

The first step in identifying the best drought management techniques and reducing negative effects by promoting coping mechanisms and adaptation is assessing the risk of drought [21]. The drought risk faced by a population is defined as the likelihood of loss, harm, or property damage, as well as socioeconomic disruption, arising from the interplay between drought hazard, exposure, and vulnerability [9,22]. A comprehensive drought risk assessment must incorporate the three interrelated components—hazard, vulnerability, and exposure—which evolve in response to climatic, economic, social, and environmental changes within a specific region.

Earlier studies on drought have generally adopted three main methodological strategies: drought hazard assessment, drought vulnerability assessment, and integrated drought risk assessment. These strategies reflect broader disaster risk concepts that link hazard, exposure, and vulnerability [9,11]. Drought hazard assessments primarily focus on the occurrence, duration, and intensity of drought events using meteorological and hydrological indicators, and have been widely applied to characterize the physical and climatic dimensions of drought [1,2]. Although such approaches provide valuable insights into drought occurrence and long-term trends, their strong emphasis on climatic factors alone limits their ability to account for socioeconomic vulnerability and the varying capacities of different systems to cope with drought impacts [9,22].

By contrast, drought vulnerability assessments emphasize social, economic, and environmental sensitivity, as well as adaptive capacity, thereby offering important perspectives on how communities and ecosystems respond to drought stress [14,16,17]. Despite their relevance, these assessments are often static and insufficiently connected to the evolving nature of drought hazards, which restricts their ability to capture changes in drought conditions over time [18,20]. More comprehensive drought risk assessments seek to integrate hazard, exposure, and vulnerability within a unified framework, consistent with risk concepts advanced by the IPCC and UNDRR [9,11]. Nevertheless, such integrated approaches remain limited at national scales and in data-scarce regions, including Iran, and frequently lack consistent representations of drought processes across spatial and temporal scales [23,24,25]. These limitations underscore the need for integrated, spatially explicit, and temporally dynamic frameworks to improve drought risk assessment.

Iran is situated far from moisture sources in the Atlantic and Mediterranean Seas because it lies within the planet’s arid belt. The majority of Iran is also in low latitudes. These two elements have extended the nation’s dry season, especially in the southern half, and made drought a natural aspect of the country’s climate. They have also caused anomalies in rainfall patterns, drastically altering the rainy season [26,27]. The main economic sector in Iran is agriculture. Almost 13% of Iran’s GDP (gross domestic product), 20% of the working population, 23% of non-oil exports, 82% of the country’s domestic food consumption, and 90% of the raw materials utilized in the food processing sector all originated from it. Additionally, 123,580 km2 of arable land benefit the area [28]. In Iran, crisis management has served as the main way of managing natural disasters like droughts in the past couple of decades [29,30].

This reliance on crisis-oriented management has constrained the effectiveness of drought mitigation efforts and, in many cases, intensified socio-economic vulnerability, especially in rural and agriculturally dependent areas.

To lessen the effects of drought, however, a shift from crisis management to risk management is required. Although previous studies have examined drought risk in Iran, significant gaps in understanding remain [23,24,25]. A thorough assessment encompassing all dimensions of drought remains to be conducted. Specifically, research that concurrently investigates drought hazard, exposure, and susceptibility within a cohesive spatio-temporal framework is still lacking, resulting in significant gaps in understanding the comprehensive nature of drought risk throughout Iran.

The objective of this study is therefore to comprehensively assess the spatio-temporal changes in drought risk across Iran from 2000 to 2019. Unlike previous research, it captures spatial and temporal variability in drought risk by providing an integrated assessment of drought risk that can support a shift from reactive crisis responses toward more proactive and risk-based drought management strategies in Iran. Specifically, in this study, we (1) analyzed how drought hazard, vulnerability, and exposure varied across Iran between 2000 and 2019; (2) evaluated the spatio-temporal changes in drought risk during this period; and (3) identified hotspot areas that need drought risk management intervention across Iran. We showed that the drought risk varies spatio-temporally across Iran, and the spatial pattern was controlled by the interaction between socio-economic and climatic factors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

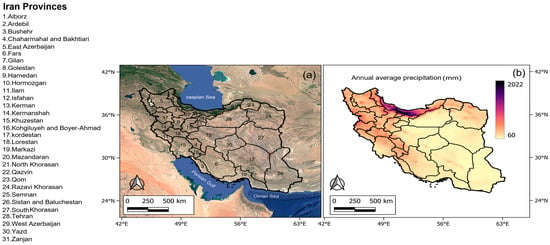

Iran is located between 25° N and 39° N latitude and 44° E and 64° E longitude, covering a total area of 1,648,000 km2 (Figure 1a). Having a primarily arid and semi-arid climate, the northern region experiences Mediterranean and humid weather [31]. The average annual rainfall ranges between about 50 mm and 2000 mm. More than 700 mm of precipitation falls annually in the northern regions, but only approximately 50 mm falls annually in the central region (Figure 1b) [32,33,34]. The annual average temperature ranges between 16 °C and 23 °C [34]. In general, the temperature decreases from south to north and from east to west due to increasing elevation and density of high mountain ranges, as well as the accumulation of the Zagros mountain range and the invasion of Siberian air masses into the central areas of Iran, respectively [35]. The elevation varies from sea level to around 5500 m at Mount Damavand [33].

Figure 1.

(a) Study area displaying the geographic location. Background satellite imagery was obtained from Google Earth (© Google, 2025; Landsat/Copernicus). Administrative boundaries were obtained from the Global Administrative Areas (GADM) database (version 4.0), provided by the GADM project (2024) and used in accordance with the GADM data license [36]. (b) Mean annual precipitation (2000–2019) was derived from the Climate Hazards Group InfraRed Precipitation with Stations (CHIRPS) open dataset [37].

2.2. Data

2.2.1. Drought Hazard Data

To analyze drought hazard, we used the monthly 2000–2019 Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) from the global high-resolution (5 km) drought indices [38]. The data has been retrieved from the Natural Environment Research Council Centre for Environmental Data Analysis (CEDA) in the United Kingdom. The URL for the data is as follows: https://catalogue.ceda.ac.uk/uuid/ac43da11867243a1bb414e1637802dec (accessed on 3 March 2024).

Four high-resolution (5 km) gridded records of drought were created, using the standardized precipitation evaporation index (SPEI) for the years 1981–2022. These SPEI indices, which cover multiple timescales (1–48 months), are derived from monthly precipitation (P) data provided by the Climate Hazards Group InfraRed Precipitation with Station Data (CHIRPS, version 2) and Multi-Source Weighted-Ensemble Precipitation (MSWEP, version 2.8), along with potential evapotranspiration (PET) data from the Global Land Evaporation Amsterdam Model (GLEAM, version 3.7a) and hourly Potential Evapotranspiration (hPET). We developed four distinct SPEI records based on every possible combination of P and PET datasets: CHIRPS_GLEAM, CHIRPS_hPET, MSWEP_GLEAM, and MSWEP_hPET [38].

2.2.2. Drought Vulnerability Data

Vulnerability factors were divided into four main criteria—economic, social, agricultural, and water availability—and 11 sub-criteria based on expert knowledge, specialized literature, and data availability (Table 1) as well as their weights based on the AHP method (Table 2). The World Bank is the primary source of the economic data (GDP per capita, Gini Index, and industrial added value), social data (labor force, aging, and health expenditure per capita), and domestic and agricultural water consumption data [39]. Urban fraction data were obtained from the global 30 m impervious-surface dynamic dataset from 1985 to 2020 [40].

The 2000–2019 cropland fraction data were obtained from the Global Land Analysis and Discovery (GLAD) database [41]. Iran’s boundaries were added to it, and data were extracted throughout the years.

We calculated the water availability from the difference between precipitation and evapotranspiration from 2000 to 2019 (Equation (1)). The precipitation data for the global land area were obtained from CHIRPS [37], and potential evaporation from GLEAM (Global Land Evaporation Amsterdam Model) GLEAM [42], which is a global, satellite-driven evaporation and soil moisture dataset available at 0.1° spatial resolution and daily temporal resolution converted to the annual dataset from 2000 to 2019, has been extensively validated globally. Calculation was employed in order to determine the water availability index as a water resources component in the drought vulnerability calculation [43], indicated in Equation (1).

Water availability = precipitation − potential evaporation

Table 1.

Drought vulnerability components (economic, social, agricultural, and water resources), associated indicators, data sources, and their expected correlations with drought vulnerability [44].

Table 1.

Drought vulnerability components (economic, social, agricultural, and water resources), associated indicators, data sources, and their expected correlations with drought vulnerability [44].

| Components | Indicator | Indicator Name | Correlation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economy | GDP cap | Gross domestic product per capita | Negative | www.worldbank.org [39] |

| Ind Add | Industrial added value | Negative | www.worldbank.org [39] | |

| Gini | Gini Index | Positive | www.worldbank.org [39] | |

| Social | Labor | Labor force | Negative | www.worldbank.org [39] |

| Aging | Elderly people over 65 | Positive | www.worldbank.org [39] | |

| Urban | Fraction of urban area (%) | Negative | globalurbanLand.html [40] | |

| Health | Health expenditure per capita | Negative | www.worldbank.org [39] | |

| Agricultural | Alrr Use | Annual freshwater withdrawals, agricultural | Negative | www.worldbank.org [39] |

| Cropland | Fraction of crop land (%) | Positive | glad.umd.edu/dataset/croplands [41] | |

| Water Resources | Water availability | Water availability | Negative | CHIRPS [37] www.gleam.eu [42] |

| Adom Use | Actual domestic water consumption | Negative | www.worldbank.org [39] |

Table 2.

Weights of components (economic, social, agricultural, water resources) and relevant indicators based on the AHP Method.

Table 2.

Weights of components (economic, social, agricultural, water resources) and relevant indicators based on the AHP Method.

| Components | Weight | Indicator | Weight | Final Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economy | 0.436 | GDP cap | 0.503 | 0.219 |

| Ind Add | 0.148 | 0.064 | ||

| Gini | 0.348 | 0.152 | ||

| Social | 0.074 | Labor | 0.246 | 0.018 |

| Aging | 0.068 | 0.005 | ||

| Urban | 0.541 | 0.040 | ||

| Health | 0.143 | 0.010 | ||

| Agricultural | 0.194 | Cropland Fraction | 0.666 | 0.129 |

| Agricultural Freshwater Withdrawals | 0.333 | 0.064 | ||

| Water Resources | 0.294 | Water Availability | 0.666 | 0.196 |

| Domestic Water Consumption | 0.333 | 0.098 |

2.2.3. Population Data

Population data used in this study were obtained from the Gridded Population of the World, Version 4 (GPWv4): Population Density, Revision 11 [45], which is publicly available from the NASA Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC) (https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/data/catalog/sedac-ciesin-sedac-gpwv4-popdens-r11-4.11 (accessed on 18 June 2025)).The dataset provides human population density (number of people per square kilometer) derived from data aligned with national censuses and population records for the years 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020. The contributed rasters were obtained by dividing the population number raster for each specific year by the land area raster. The final data were generated at a 30 arc-second (~1 km at the equator) resolution. The shapefiles about the geographical boundaries and administrative provinces of Iran were obtained from GADM. The population numbers of each province were extracted over a 5-period time scale (2000–2003, 2004–2007, 2008–2011, 2012–2015, 2016–2019) to generate a table of average population numbers (Supplementary Figure S1).

2.3. Methods

The following sections describe the detailed methods used to compute the drought hazard index, vulnerability, exposure, and risk. All processing of drought hazard, vulnerability, exposure, and risk was carried out. All data were processed using R software (version 4.4.2), and maps and figures were composed using QGIS software (version 3.44.6).

2.3.1. Drought Hazard Index

The quantitative measurement of drought hazard is based on the utilization of multiple drought indices, as evidenced by numerous research studies [23,44,46,47]. This approach consolidates drought characteristics—magnitude, frequency, and severity—into a single numerical measure, termed the drought hazard index (DHI). This index has been developed for the purpose of measuring the length, intensity and, regional reach of droughts, thus enabling it to serve as a useful indicator for evaluating the relative threat posed by a drought event. The weights (Wi) were determined using drought classifications that have been widely employed, based on the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI). The severity of droughts was categorized as follows [44]: normal to mild droughts (SPEI values between 0.5 and −1.0), moderate droughts (SPEI values between −1 and −1.5), severe droughts (SPEI values between −1.5 and −2), and extreme droughts (SPEI values below −2). Subsequently, an additional division of the weighted categories was conducted. Groups are to be divided using the equal break of the CDF, and assigned rating values (Ri). The range of the variable is from 1 to 4. The DHI was calculated by combining the corresponding weights and rates indicated in Equation (2):

2.3.2. Drought Vulnerability

According to the widely accepted definition provided by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), vulnerability is the propensity or predisposition to be adversely affected [5]. Vulnerability is the extent to which a system is vulnerable to and incapable of withstanding the negative consequences of change [48]. This study uses an integrated drought vulnerability index that considers the environment, society, and the economy as vulnerability factors.

Indicators

The evaluation of drought vulnerability is subject to a number of constraints, and there is no universally applicable set of indicators. It is imperative to establish alternative indicators or proxy variables that can accurately quantify and convey pertinent information during the evaluation of drought risk [49,50]. The following procedures were employed in order to conduct the drought assessment study: data selection, downloading relevant data in various forms, pre-processing, and reformatting. The data were then subjected to a process of normalization and weighted using the Analytic Hierarchy Process approach [51]. Details of the methodology are provided in the following.

Calculating Drought Vulnerability Index (DVI)

The four primary data types were economic, social, agricultural, and water resources. These were chosen based on the literature, expert knowledge, and data availability. The concept of vulnerability is understood to be directly impacted by an area’s socioeconomic conditions and can be used as a barometer to assess the degree of loss or damage after an incident. A number of studies have been conducted to assess the vulnerability of water resources to the effects of climate change [52].

Weighting Method (Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) Method)

In this study, both the Equal Weighted Method and the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) [53] were utilized to accurately determine the weights of the factors. A comparative analysis showed that the AHP method was more efficient. Consequently, the AHP method was selected for its greater validation and contribution to our research. The weights of the indicators were developed based on expert subjectivity and grounded in the previous literature related to the fields of climate, socioeconomic, and agricultural studies.

This approach was developed by Saaty [53,54,55]. The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) is a system for making decisions that is organized into hierarchical levels. It includes objectives, criteria, sub-criteria, and alternatives. The extent to which the decision maker comprehends the situation is indicated by these levels. The decision maker is able to focus on smaller subsets of choices by breaking the problem down into various levels, thus facilitating more accurate and manageable decision-making (Table 3).

Table 3.

Relative importance scale used for assigning weights to drought vulnerability factors through the Analytic Hierarchical Process (AHP), adapted from on the methodology proposed by Saaty (1987) [53].

The four primary steps of the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) are intended to evaluate candidate requirements according to their relative significance. Firstly, an (n × n) matrix must be established with (n) candidate requirements as its rows and columns. Secondly, a predefined criterion and a determined comparative scale should be utilized to compare the requirements. In order to facilitate inverse comparisons, it is necessary to include a value of “1” in the diagonal entries and reciprocal values. The degree of preference should then be entered into the appropriate parts of the matrix. Subsequently, the mean of the standardized columns was calculated in order to estimate the comparison matrix’s eigenvalues. Subsequent to the calculation of the column sums, it is imperative that each entry must be divided by the sum of its columns in order to normalize it. The final step in this process is to add up each row. Finally, the estimated eigenvalues should be used to assign relative values to each condition [56].

Normalization

In order to ensure the comparability of the components employed in the evaluation of drought vulnerability, each component is subjected to independent adjustment. This approach was chosen to allow consistent integration of variables with different units and scales in the DVI calculation. Equations (3) and (4) involve the normalization of factors using their maximum and minimum values.

Equations (3) and (4): (3) Positive correlation with drought vulnerability; (4) negative correlation with drought vulnerability.

In this equation, represents the value of each factor, and and reflect the factor’s minimum and maximum values throughout the research period. The values Z = 0 and Z = 1 represent the lowest and highest vulnerability, respectively. For the factors that were demonstrated to be positively correlated with drought vulnerability, the first part (3) of the method was employed. Conversely, for the factors that were demonstrated to be negatively correlated with drought vulnerability, the second part (4) of the method was employed. The correlation between the factor and total vulnerability was established on the basis of previous investigations and rigorous reasoning [57].

Consistency Ratio (CR)

The consistency ratio (CR) is a measure of the accuracy of the pairwise comparisons [58]. It facilitates the measurement of judgment errors through the calculation of the consistency index (CI) of the comparison matrix and subsequent determination of the consistency ratio. The CI is a primary metric of the precision of the pairwise comparisons. Equation (5):

The maximum principal eigenvalue of the comparison matrix is denoted by and n is the number of requirements.

The consistency indices of randomly generated reciprocal matrices from the scale of 1 to 9 are referred to as the random indices, RI. Equation (6):

A CR of 0.10 or less is generally deemed acceptable for consistency [59]. In this study, all CRs are less than 0.1 (Table S1).

2.3.3. Drought Exposure

The Gridded Population of the World, Version 4 (GPWv4): Population Density, Revision 11Database was utilized for the estimation of populations affected by drought, a process which is indispensable for the evaluation of drought [45]. The gridded population records were utilized to estimate population exposure to drought, following a 30 arc-second (~1 km at the equator) resolution. Subsequently, the Iran boundary and province shapefiles were overlaid, and the population number for each province was extracted.

2.3.4. Drought Risk

The concept of “drought risk to population” has been defined as the likelihood of harm, property damage, and social or economic disruption due to the interaction of hazard, exposure, and vulnerability (see above) [57]. The risk posed by drought to a given population can thus be estimated using Equation (7):

Risk = DHI × DVI × E

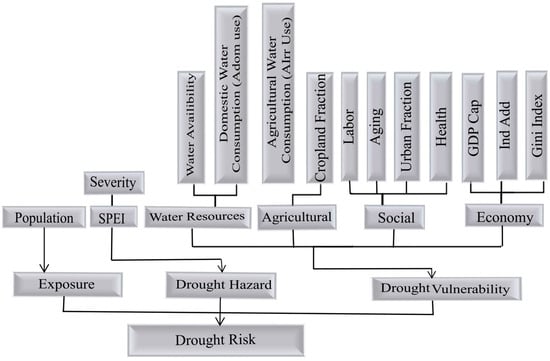

In this equation, DHI is the acronym for the drought hazard index, DVI is the acronym for the drought vulnerability index, and E is the acronym for the level of population exposure [44] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Methodology flow chart showing drought risk components (drought vulnerability, drought hazard, and drought exposure), sub-components, and analysis approach.

3. Results

3.1. Drought Hazard Change

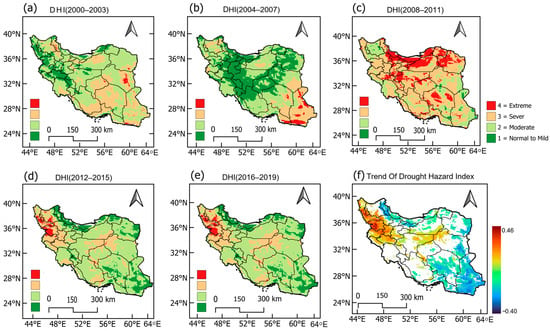

The average drought hazard and its trends from 2000 to 2019 are presented in Figure 3. The Drought Hazard Index (DHI) underwent substantial alterations in approximately 50% of the area of Iran (~792,883 km2). Of this, DHI increased by 21%, impacting 337,982 km2 (see Table 4). The increase in DHI had a significant impact on the northwest (the East and West Azerbaijan and Ardebil provinces), the west (Kordestan, Kermanshah, and Hamedan provinces), and the central (Semnan, Isfahan, and Yazd provinces) parts of Iran. The most significant increase was observed in Kordestan province, with a DHI value of 0.45 in the study period. In contrast, 28% (454,901 km2) of Iran demonstrated a substantial decline in DHI (see Figure 3 and Table 4). There was a decrease in DHI in the northern provinces of Ardebil, Gilan, Mazandaran, and Golestan. The southeastern region, encompassing the Sistan and Baluchestan province, also demonstrated a decline in DHI; this was the most significant reduction in DHI, with a value of −0.4. Supplementary Figures S2 and S3 provide further details about the probability density function and standard deviation for DHI.

Figure 3.

Drought hazard index (a–e) based on the Standardized Precipitation Evaporation Index (SPEI) from 2000 to 2019. Each drought hazard index is averaged over four years. Panel (f) shows the annual trends of the drought hazard index. Only significant (p < 0.05) trends are displayed (f). Non-significant trends have been masked.

Table 4.

The distribution of land area in Iran was significantly affected by drought hazard from 2000 to 2019, with both significantly and non-significantly impacted regions being shown in terms of both percentage and total area.

3.2. Change in Drought Vulnerability

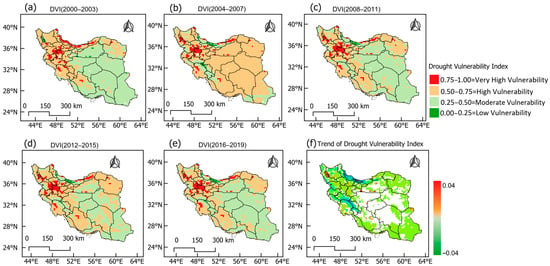

Drought vulnerabilities and their change during 2000–2019 are illustrated in Figure 4 and Table 4. The calculation of the Drought Vulnerability Index (DVI) was performed utilizing 16 indicators (Table 1). Approximately 59% of the study area underwent substantial alterations in drought vulnerability during the initial two decades of the 21st century (Figure 4 and Table 5). Of this, 46% (a total area of 737,456 km2) exhibited an increase in drought vulnerability during this period. The regions demonstrating the most pronounced increases in drought vulnerability are located in western North Iran (West and East Azerbaijan and Lake Urmia) and the central regions (Markazi, Qom, and Semnan provinces). The area that demonstrated the most significant increase was Salt Lake, situated at the intersection of three provinces (Qom, Semnan, and Isfahan), with a value of 0.045, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The drought vulnerability index (a–e) is based on socio-economic, agricultural, and water resource data (2000–2019), which were averaged over four years. Only significant (p < 0.05) trends (f) are displayed. Non-significant trends were masked.

Table 5.

The distribution of land area in Iran affected by drought vulnerability from 2000 to 2019, with both significantly and non-significantly impacted regions being evident in terms of both percentage and total area.

Conversely, 13% (213,393 km2) exhibited a substantial decline in DVI (see Table 5), encompassing the Northern (Gilan, Mazandaran) and Western (Lorestan, Chaharmahal and Bakhtiyari, Kohgiloye and BouyerAhmad) regions. The province of Mazandaran underwent a substantial decline in DVI, with a recorded value of −0.046. Supplementary Figures S4 and S5 provide additional information about the probability density function and standard deviation between DVIs.

3.3. Change in Drought Risk

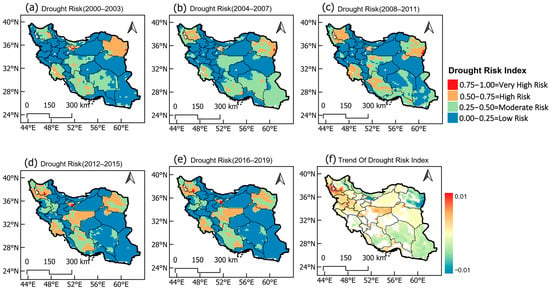

The temporal progression of drought risk alterations within Iran from 2000 to 2019 is shown in Figure 5 and Table 6. Approximately 69% of the country’s total area (1,089,913 km2) exhibited significant changes in drought risk.

Figure 5.

Spatial distribution of the Drought Risk Index (DRI) across Iran from 2000 to 2019 is shown in maps (a–e); map (f) highlights regions where changes in DRI over the study period were statistically significant. Areas with non-significant changes have been masked to emphasize regions with meaningful shifts in drought risk.

Table 6.

The distribution of land area in Iran under drought risk from 2000 to 2019, illustrating both significantly and non-significantly impacted regions. Values are presented as percentages and total area (km2) to illustrate the extent of risk across the country.

Of this, 23% (368,097 km2) exhibited an increase in drought risk during the study period. The regions demonstrating the most substantial hotspots in drought risk are located in the northwest and west of Iran (the provinces of West and East Azerbaijan) and the central regions (the provinces of Isfahan and Semnan). As demonstrated in Figure 5, West Azerbaijan province has undergone the most substantial increase, with a value of 0.01.

A decreasing trend in drought risk was observed in 46% (721,816 km2) of the study area. A marked decline was observed in the northern and southern regions of the Alborz Mountains, encompassing the provinces of Tehran, Gilan, Mazandaran, and Khorasan Razavi. The lowest observed value, −0.01, was recorded in Tehran and Razavi Khorasan provinces. Supplementary Figures S6 and S7 provide additional information about the probability density function and standard deviation of DR.

4. Discussion

The present study evaluated the risk of drought and its constituent elements throughout Iran. Spatial and temporal maps for drought hazard, vulnerability, exposure, and risk were prepared. The findings indicate that the spatio-temporal patterns of drought risk vary across Iran and are determined primarily by the interaction between climatic and socio-economic factors. Elevated risk was observed in regions experiencing concurrent drought hazard and population growth, such as West/East Azerbaijan and Isfahan provinces.

4.1. Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Drought Hazard

A rise in drought hazard was observed throughout the country from 2000 to 2019, with the most severe conditions being documented in the northwest and central regions of Iran. These findings are consistent with the findings of previous studies, which have also indicated an increase in the severity and frequency of droughts due to climate change in those regions [1,60]. The observed rise in drought hazard in the northwest and west is a cause for concern, given these regions’ environmental and agricultural significance. The two most prevalent crops that are typically produced in semi-arid regions of Iran under rainfed circumstances are wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). The fields in Iran’s west and northwest provide over 75% of the nation’s total production of rainfed wheat and barley [59].

Furthermore, the observed decline in drought conditions in northern regions may be attributable to the rainfall patterns and their climatic characteristics. The majority of precipitation falls on the Caspian Sea’s shores and in hilly areas. On the northern slopes of the Alborz range, the average annual precipitation exceeds 2000 mm. Because of the humid environment and increased precipitation levels, the northern regions, especially those close to the Caspian Sea, saw less severe drought [61].

4.2. Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Drought Vulnerability

The increasing trend of drought vulnerability in approximately 46% of the country’s territory, particularly in the western and central regions, signifies the fragility of economic and social frameworks and the reliance of arid regions with constrained water resources on the agricultural sector. This observation is consistent with the findings of previous studies, which emphasized the absence of coordination between the agricultural economy and climate variations [9,57]. The DVI in regions such as Qom and Semnan provinces and Lake Urmia demonstrates the correlation between unsustainable water management and enhanced evaporation and transpiration resulting from climate change, consequently leading to increased vulnerability [26,30]. The substantial inefficiency in Iran’s agricultural sector, which uses more than 92% of the nation’s water, is a major contributing factor [62]. The salinity of groundwater recharge can be considerably elevated by irrigated agriculture, particularly when return flows are high and irrigation efficiency is low [63]. This, in turn, has a detrimental effect on agricultural productivity and has been shown to cause long-term land degradation. The socio-economic dimensions of drought vulnerability across Iran are consequently exacerbated by factors such as limited adaptive capacity, inadequate infrastructure, and poor water resource management.

4.3. Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Drought Risk

Our results show that there is a high risk of drought in the west, northwest, and central regions due to the high exposure and hazard, and vulnerability. These results indicate concurrently the existence of a relationship between climatic conditions and socio-economic circumstances [16].

It should be mentioned that some regions have high levels of drought hazard but relatively low overall risk of drought. Reduced vulnerability or low population exposure, which reduces the risk of drought, is the primary cause of this disparity. For instance, we discovered that likely due to their resilient ecological systems, abundant rainfall, and stable climate, the northern slopes of the Alborz Mountains are the area least vulnerable to drought. Despite sporadic variations in hazard, these areas also have better adaptive capacity and well-developed infrastructure, especially in Mazandaran and Gilan, where exposure and vulnerability are low. In line with the findings of [21,64], the combination of these factors significantly reduces the risk of drought. On the other hand, West Azerbaijan province has the highest risk of drought, which is caused by the convergence of all three risk factors—vulnerability, exposure, and hazard at high levels. Lake Urmia’s drying has resulted in a reduction in water availability and ecosystem resilience, exacerbating drought conditions and ecological stress in the area. At the same time, intensive agricultural practices and population growth have raised demand and exposure on already stressed water systems. Moreover, it has been reported that the region’s vulnerability is exacerbated by a lack of preparedness for drought and deteriorating groundwater quality [25,65]. This phenomenon aligns with the theoretical framework proposed by [16], which posits that the interplay between biophysical hazards and human systems plays a pivotal role in shaping drought risk, superseding the influence of solely climatic factors.

The significance of integrated drought management strategies, which take ecological capacity, infrastructure resilience, and demographic pressures into consideration, is highlighted by these spatial variations. The absence of proactive adaptation measures may ultimately trigger a shift in these trends, even within areas that are currently considered low-risk.

4.4. Implications, Limitations, and Future Directions

In order to assess drought risk with maximum efficacy, it is essential to employ an integrated approach that incorporates economic, social, agricultural, and demographic factors in conjunction with climatic data. Through comprehensive analysis, the intersection of hazard, vulnerability, and exposure has been delineated, thus facilitating the identification of regions within Iran that are particularly vulnerable to drought. These areas comprise the provinces of West and East Azerbaijan as well as central Iran’s Isfahan and Fars. These insights could help policymakers move from reactive to more proactive drought planning. Rather than waiting for catastrophes to occur, one can now plan to reduce risks before they turn into crises. The approach used here also offers a useful basis that can be adapted for use in other drought-prone areas.

While the current research has yielded valuable insights, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. Expert opinion may inject some subjectivity into the evaluation of indicators, particularly when techniques such as AHP are employed. The demographic statistics have another limitation. By using a 0.5-degree resolution, local exposure disparities may be smoothed out, which might be important in areas with both urban and rural populations. It is particularly important to bear in mind that this study neglected aspects that relate to institutions and policies. These factors are often essential in comprehending how communities respond to drought.

To gain a more complete knowledge of the challenges involving vulnerability, governance, and institutional matters, additional aspects must be considered. Such factors include the presence of early warning systems and the availability of drought forecasting programs. The combination of predictions of climate change with patterns of land use and population may facilitate a more profound comprehension of the temporal variation in drought risks. It is important that solutions are more realistic and suited to local conditions if local residents are directly involved through participatory mapping or interviews.

The integration of drought risk assessments into national and provincial water management strategies is imperative to ensure the sustainability of specific projects. Furthermore, the establishment of a connection between agricultural guidance and climatic forecasts has the potential to enhance anticipatory responses at the local level. To address the water requirements of agriculture, urban areas, and ecosystems during extended drought periods, it is recommended to implement flexible legal instruments and adaptive water allocation regulations. Consequently, the transformation of scientific risk assessments into pragmatic resilience strategies for community utilization by authorities and stakeholders could be an efficacious approach.

5. Conclusions

This study provided a combined look at drought risk in Iran from 2000 to 2019. It analyzed drought hazards, the vulnerability of different communities, and how populations are exposed to these risks. The results demonstrate that drought risk has increased across 57% of Iran, particularly in the western, northwestern, and central regions, where intensifying climatic stress coincides with high vulnerability and growing exposure. These regions experience increasing climate stress along with high vulnerability and growing exposure. In contrast, some areas of northern Iran had a lower risk of drought. The observed changes were attributed to reduced vulnerability and an enhanced capacity to adapt to variations, even in the context of climate variability. These findings indicate that the drought risk in Iran is influenced by factors beyond just climate-related issues. It stems from a combination of water-related climate elements and socioeconomic characteristics. This study transitions from focusing solely on the drought hazard approach to adopting a comprehensive perspective on drought risk. It emphasizes the need to prioritize hotspot regions, which should implement mitigation strategies. The results highlight the significance of transitioning from crisis management to drought mitigation management strategies. This shift will strengthen resilience by encouraging improved water management, reducing socio-economic vulnerability, and creating adaptation plans customized for specific locations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/w18030315/s1: Figure S1. Population distribution by region in Iran from 2000 to 2019, illustrating temporal trends and spatial patterns over the 20-year period. Table S1. Consistency ratios (CRs) for each component and criterion derived from the analytic hierarchy process (AHP). All CR values are below 0.1, indicating acceptable consistency and strong agreement among expert judgments. Figure S2. Probability distribution function (PDF) illustrating the spatial variability of the Drought Hazard Index (DHI) in Iran from 2000 to 2019; peaks indicate areas experiencing recurrent drought. Figure S3. Standard deviation (STD) of the Drought Hazard Index (DHI) in Iran from 2000 to 2019, indicating significant interannual variability in drought severity. Figure S4. Probability distribution function (PDF) of the Drought Vulnerability Index (DVI) from 2000 to 2019, used to identify regions with high vulnerability to recurrent drought. Figure S5. Standard deviation (STD) of the Drought Vulnerability Index (DVI) over the study period, indicating spatial variability in drought vulnerability. Figure S6. Probability distribution function (PDF) of the Drought Risk Index (DRI) from 2000 to 2019, illustrating the distribution and frequency of drought risk. Figure S7. Standard deviation (STD) of the Drought Risk Index (DRI) from 2000 to 2019, indicating areas with significant spatial variability in drought risk.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.R., D.Z. and T.A.A.; methodology, P.R., T.A.A. and D.Z.; analysis, P.R. and A.T.P.; writing—original draft preparation, P.R.; writing—review and editing, D.Z., T.A.A., A.M. and A.T.P.; visualization, P.R.; supervision, D.Z. and T.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the Open Access Publishing Fund of Philipps-Universität Marburg.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in: Climate Hazards Group InfraRed Precipitation with Station Data (CHIRPS), available at https://www.chc.ucsb.edu/data/chirps (accessed on 28 April 2024). Global High-Resolution Drought Indices (1981–2022), Natural Environment Research Council Centre for Environmental Data Analysis (CEDA), available at https://catalogue.ceda.ac.uk/uuid/ac43da11867243a1bb414e1637802dec (accessed on 3 March 2024). Global Land Evaporation Amsterdam Model (GLEAM), version 3.7a, available at https://www.gleam.eu (accessed on 18 March 2024). World Bank World Development Indicators (WDI), available at https://www.worldbank.org. Global 30-m Impervious Surface Dynamic Dataset (GISD30), available at https://zenodo.org/records/5220816 (accessed on 25 April 2024). Global Land Analysis and Discovery (GLAD) Cropland Dataset, available at https://glad.umd.edu/dataset/croplands (accessed on 5 May 2024). Centre for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN), Columbia University. Gridded Population of the World, Version 4 (GPWv4): Population Density, Revision 11 (Version 4.11), available at https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/data/catalog/sedac-ciesin-sedac-gpwv4-popdens-r11-4.11 (accessed on 18 June 2024).

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the first author used QuillBot (v40.11.1), DeepL Translator (latest available online version; https://www.deepl.com/), and Grammarly (latest available online version; https://app.grammarly.com/) for the purposes of paraphrasing and English-language grammar and style editing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- AghaKouchak, A.; Mirchi, A.; Madani, K.; Di Baldassarre, G.; Nazemi, A.; Alborzi, A.; Anjileli, H.; Azarderakhsh, M.; Chiang, F.; Hassanzadeh, E.; et al. Anthropogenic Drought: Definition, Challenges, and Opportunities. Rev. Geophys. 2021, 59, e2019RG000683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, A. Drought under Global Warming: A Review. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2011, 2, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021–The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; ISBN 978-1-00-915789-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Global Drought Outlook: Trends, Impacts and Policies to Adapt to a Drier World; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2025; ISBN 978-92-64-54069-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects; Field, C.B., Barros, V.R., Dokken, D.J., Mach, K.J., Mastrandrea, M.D., Bilir, T.E., Chatterjee, M., Ebi, K.L., Estrada, Y.O., Genova, R.C., et al., Eds.; Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Field, C.B.; Barros, V.; Stocker, T.F.; Qin, D.; Dokken, D.J.; Ebi, K.L.; Mastrandrea, M.D.; Mach, K.J.; Plattner, G.-K.; Allen, S.K.; et al. Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-1-107-02506-6. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, W.; Fu, Q.; Liu, D.; Li, T.; Cheng, K.; Cui, S. Spatiotemporal Analysis of the Agricultural Drought Risk in Heilongjiang Province, China. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2018, 133, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkmann, J. Measuring Vulnerability to Promote Disaster-Resilient Societies: Conceptual Frameworks and Definitions. In Measuring Vulnerability to Natural Hazards: Towards Disaster Resilient Societies; United Nations University Press: Tokyo, Japan; New York, NY, USA; Paris, France, 2006; pp. 9–54. ISBN 978-92-808-1135-3. [Google Scholar]

- Carrão, H.; Naumann, G.; Barbosa, P. Mapping Global Patterns of Drought Risk: An Empirical Framework Based on Sub-National Estimates of Hazard, Exposure and Vulnerability. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2016, 39, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dracup, J.A.; Lee, K.S.; Paulson, E.G. On the Definition of Droughts. Water Resour. Res. 1980, 16, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDRR. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030; UNDRR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wisner, B.; Blaikie, P.; Cannon, T.; Davis, I. At Risk: Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability and Disasters. In At Risk: Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability and Disasters; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Adaptation Community. Conceptual Framework. Adaptation Community, n.d. Available online: https://www.adaptationcommunity.net/climate-risk-assessment-management/climate-risk-sourcebook/conceptual-framework/ (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Cutter, S.L.; Finch, C. Temporal and Spatial Changes in Social Vulnerability to Natural Hazards. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 2301–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, J.; MacGillivray, B.H.; Gong, Y.; Hales, T.C. The Application of Frameworks for Measuring Social Vulnerability and Resilience to Geophysical Hazards within Developing Countries: A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 711, 134486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.L.; Kasperson, R.E.; Matson, P.A.; McCarthy, J.J.; Corell, R.W.; Christensen, L.; Eckley, N.; Kasperson, J.X.; Luers, A.; Martello, M.L.; et al. A Framework for Vulnerability Analysis in Sustainability Science. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8074–8079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blauhut, V.; Stahl, K.; Stagge, J.H.; Tallaksen, L.M.; De Stefano, L.; Vogt, J. Estimating Drought Risk across Europe from Reported Drought Impacts, Drought Indices, and Vulnerability Factors. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2016, 20, 2779–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumann, G.; Cammalleri, C.; Mentaschi, L.; Feyen, L. Increased Economic Drought Impacts in Europe with Anthropogenic Warming. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2021, 11, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, W.; Fu, Q.; Liu, D.; Li, T.; Cheng, K.; Cui, S. A Novel Method for Agricultural Drought Risk Assessment. Water Resour. Manag. 2019, 33, 2033–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Gentine, P.; Slater, L.; Gu, L.; Pokhrel, Y.; Hanasaki, N.; Guo, S.; Xiong, L.; Schlenker, W. Future Socio-Ecosystem Productivity Threatened by Compound Drought–Heatwave Events. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, P.M.; Adger, W.N. Theory and Practice in Assessing Vulnerability to Climate Change and Facilitating Adaptation. Clim. Chang. 2000, 47, 325–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadalipour, A.; Moradkhani, H.; Castelletti, A.; Magliocca, N. Future Drought Risk in Africa: Integrating Vulnerability, Climate Change, and Population Growth. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 662, 672–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrollahi, M.; Khosravi, H.; Moghaddamnia, A.; Malekian, A.; Shahid, S. Assessment of Drought Risk Index Using Drought Hazard and Vulnerability Indices. Arab. J. Geosci. 2018, 11, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari Alamdarloo, E.; Khosravi, H.; Nasabpour, S.; Gholami, A. Assessment of Drought Hazard, Vulnerability and Risk in Iran Using GIS Techniques. J. Arid. Land 2020, 12, 984–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafi, L.; Zarafshani, K.; Keshavarz, M.; Azadi, H.; Van Passel, S. Drought Risk Assessment: Towards Drought Early Warning System and Sustainable Environment in Western Iran. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 114, 106276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudarzi, M.; Hosseini, S.A. Drought (Assessment, Vulnerability); Salam Sepahan (Miras-e-Kohan): Isfahan, Iran, 2018. (In Persian) [Google Scholar]

- Shiravand, H.; Bayat, A. Vulnerability and Drought Risk Assessment in Iran Based on Fuzzy Logic and Hierarchical Analysis. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2023, 151, 1323–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirkhani, S.; Chizari, M. Factors Influencing Drought Management in Varamin Township. In Proceedings of the Third Congress of Agricultural Extension and Natural Resources, Mashhad, Iran, 2–3 March 2010; pp. 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Karami, E. Drought management and the role of knowledge and information. In Proceedings of the National Conference on Challenges and Strategies of Drought, Shiraz, Iran, 23–24 May 2009; pp. 40–65. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291969503_Drought_management_and_the_role_of_knowledge_and_information (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Keshavarz, M.; Karami, E.; Vanclay, F. The Social Experience of Drought in Rural Iran. Land Use Policy 2013, 30, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helali, J.; Momenzadeh, H.; Oskouei, E.A.; Lotfi, M.; Hosseini, S.A. Trend and ENSO-Based Analysis of Last Spring Frost and Chilling in Iran. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 2021, 133, 1203–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darand, M.; Pazhoh, F. Spatiotemporal Changes in Precipitation Concentration over Iran during 1962–2019. Clim. Chang. 2022, 173, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoudi, M.; Hakimi, S. A New Model for Vulnerability Assessment of Drought in Iran Using Percent of Normal Precipitation Index (PNPI). Trans. A Sci. 2014, 38, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshir Panahi, D.; Kalantari, Z.; Ghajarnia, N.; Seifollahi-Aghmiuni, S.; Destouni, G. Variability and Change in the Hydro-Climate and Water Resources of Iran over a Recent 30-Year Period. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alijani, B. Variations of 500 hPa Flow Patterns over Iranand Surrounding Areas and Their Relationship with the Climate of Iran. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2002, 72, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Administrative Areas (GADM). GADM Database of Global Administrative Areas, Versions 4.0–4.1; 2015–2022. Available online: https://gadm.org (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Funk, C.; Peterson, P.; Landsfeld, M.; Pedreros, D.; Verdin, J.; Shukla, S.; Husak, G.; Rowland, J.; Harrison, L.; Hoell, A.; et al. The Climate Hazards Infrared Precipitation with Stations—A New Environmental Record for Monitoring Extremes. Sci. Data 2015, 2, 150066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrechorkos, S.H.; Peng, J.; Dyer, E.; Miralles, D.G.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Funk, C.; Beck, H.E.; Asfaw, D.T.; Singer, M.B.; Dadson, S.J. Global High-Resolution Drought Indices for 1981–2022. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2023, 15, 5449–5466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Development Indicators|DataBank. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Liu, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, T.; Gao, Y.; Chen, X.; Mi, J. GISD30: Global 30-m Impervious Surface Dynamic Dataset from 1985 to 2020 Using Time-Series Landsat Imagery on the Google Earth Engine Platform. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 14, 1831–1856. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/5220816 (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Potapov, P.; Turubanova, S.; Hansen, M.C.; Tyukavina, A.; Zalles, V.; Khan, A.; Song, X.-P.; Pickens, A.; Shen, Q.; Cortez, J. Global maps of cropland extent and change show accelerated cropland expansion in the twenty-first century. Nat. Food 2021, 3, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles, D.G.; Bonte, O.; Koppa, A.; Baez-Villanueva, O.M.; Tronquo, E.; Zhong, F.; Beck, H.E.; Hulsman, P.; Dorigo, W.; Verhoest, N.E.C.; et al. GLEAM4: Global Land Evaporation and Soil Moisture Dataset at 0.1° Resolution from 1980 to near Present. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Dutra, E.; Agustí-Panareda, A.; Albergel, C.; Arduini, G.; Balsamo, G.; Boussetta, S.; Choulga, M.; Harrigan, S.; Hersbach, H.; et al. ERA5-Land: A State-of-the-Art Global Reanalysis Dataset for Land Applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 4349–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Sun, F. Integrated Drought Vulnerability and Risk Assessment for Future Scenarios: An Indicator Based Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 900, 165591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center For International Earth Science Information Network-CIESIN-Columbia University Gridded Population of the World, Version 4 (GPWv4): Population Density, Revision 11 2017. Available online: https://earthdata.nasa.gov/data/catalog/sedac-ciesin-sedac-gpwv4-popdens-r11-4.11 (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Dabanli, I. Drought Hazard, Vulnerability, and Risk Assessment in Turkey. Arab. J. Geosci. 2018, 11, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Park, J.; Yoo, J.; Kim, T.-W. Assessment of Drought Hazard, Vulnerability, and Risk: A Case Study for Administrative Districts in South Korea. J. Hydro-Environ. Res. 2015, 9, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N. Vulnerability. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, M.A.; Janetos, A.C. National Indicators of Climate Changes, Impacts, and Vulnerability. Clim. Chang. 2020, 163, 1695–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielman, S.E.; Tuccillo, J.; Folch, D.C.; Schweikert, A.; Davies, R.; Wood, N.; Tate, E. Evaluating Social Vulnerability Indicators: Criteria and Their Application to the Social Vulnerability Index. Nat. Hazards 2020, 100, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. Analytic Hierarchy Process. In Encyclopedia of Operations Research and Management Science; Gass, S.I., Fu, M.C., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 52–64. ISBN 978-1-4419-1137-7. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger, M.J.; Leemans, R.; Schröter, D. A Multidisciplinary Multi-Scale Framework for Assessing Vulnerabilities to Global Change. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2005, 7, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, R.W. The Analytic Hierarchy Process—What It Is and How It Is Used. Math. Model. 1987, 9, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. Axiomatic Foundation of the Analytic Hierarchy Process. Manag. Sci. 1986, 32, 841–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.; Vargas, L. Decision Making in Economic, Political, Social, and Technological Environments with the Analytic Hierarchy Process; RWS: Maidenhead, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, T.L. How to Make a Decision: The Analytic Hierarchy Process. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1990, 48, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadalipour, A.; Moradkhani, H. Multi-Dimensional Assessment of Drought Vulnerability in Africa: 1960–2100. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 644, 520–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, S.; Kumar, A.; Ram, M.; Klochkov, Y.; Sharma, H.K. Consistency Indices in Analytic Hierarchy Process: A Review. Mathematics 2022, 10, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture. Statistics of Agricultural Products, Crop Production in 2013–2014; Office of Statistics and Information Technology, Ministry of Agriculture: Tehran, Iran, 2015. Available online: https://irandataportal.syr.edu/wp-content/uploads/05.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Thomas, T.; Jaiswal, R.K.; Galkate, R.; Nayak, P.C.; Ghosh, N.C. Drought Indicators-Based Integrated Assessment of Drought Vulnerability: A Case Study of Bundelkhand Droughts in Central India. Nat. Hazards 2016, 81, 1627–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkaman Pary, A.; Rastgoo, P.; Opp, C.; Zeuss, D.; Abera, T.A. Impacts of Drought Severity and Frequency on Natural Vegetation Across Iran. Water 2024, 16, 3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. AQUASTAT; Aqua Statistics of Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2016; Available online: https://www.fao.org/aquastat/en/databases/maindatabase/index.html?utm_source (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Foster, S.; Pulido-Bosch, A.; Vallejos, Á.; Molina, L.; Llop, A.; MacDonald, A.M. Impact of Irrigated Agriculture on Groundwater-Recharge Salinity: A Major Sustainability Concern in Semi-Arid Regions. Hydrogeol. J. 2018, 26, 2781–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latifi, H.; Khorramdel, S.; Koocheki, A.; Bannayan, M.; Farzaneh, M.-R. Drought Risk Assessment by Applying Drought Hazard and Vulnerability Indices for Irrigated Wheat (Case Study: Khorasan Provinces, Iran). Preprint [Research Square] 2023. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/375181857_Drought_risk_assessment_by_applying_drought_hazard_and_vulnerability_indices_for_irrigated_wheat_Case_study_Khorasan_provinces_Iran (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Zarafshani, K.; Maleki, T.; Keshavarz, M. Assessing the Vulnerability of Farm Families towards Drought in Kermanshah Province, Iran. GeoJournal 2020, 85, 823–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.