Abstract

Microorganisms live in a wide range of environments, performing diverse roles either independently or in association with other organisms forming consortia. This study is focused on those with the ability to bioremediate environments contaminated with petroleum hydrocarbons (PHCs), that is, the case of bacteria, fungi, algae, and consortia. PHC contamination constitutes a major global environmental issue, and presents a serious ecological risk. This research was conducted in the coastal waters of Haina Port (Dominican Republic) and the main objective was to characterise the bacterial communities with bioremediation capacity by sequencing the 16S rRNA. The samples were collected in sterile conditions, and physicochemical and molecular analyses were conducted. The results revealed the composition and distribution of bacterial communities in the area. At the phylum level, Proteobacteria is the dominant group, accounting for 70–90% of the community. At the class level, Gammaproteobacteria is the predominant group, followed by Alphaproteobacteria which ranks second in relative abundance. Bacillaceae appears as the most abundant family at most points. This 16S rRNA survey provides a taxonomic baseline of the microbial community, identifying taxa with documented degradative potential. Future functional analyses and culture studies are required to quantify and confirm the active metabolic pathways of the detected microorganisms.

1. Introduction

In nature, there is a wide variety of microorganisms, either in microbial associations with different properties and functions or in symbiosis with other organisms, and they have developed the ability to use organic molecules as a source of carbon and energy, thus adapting to contaminated environments [1,2,3,4,5]. A wide range of microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, yeasts, and algae, can metabolise contaminating organic compounds and produce water, carbon dioxide, and other, less toxic elements. Herein lies their importance in bioremediation processes in environments contaminated with hydrocarbons [6,7,8,9,10]. Therefore, strategies using microorganisms for the remediation of contaminated environments are a promising alternative. Indeed, they have significant efficiency in reducing pollution levels, coupled with a versatility that allows them to be used with different contaminants and in different environments [11]. Bioremediation is the most efficient, eco-friendly, and cost-effective technology for the transformation of contaminants [12]. Some bioremediation strategies include adding specific compounds to enhance the metabolic activity of the autochthonous microorganisms (biostimulation) and/or adding specific microbial taxa with high biodegradation capabilities (bioaugmentation) [13,14,15,16].

Regulatory ecosystem services, including soil and water purification, have a strong correlation with microbial function. Bacterial diversity and metabolic versatility are essential for maintaining these services. Together, these qualities enable the biodegradation of a wide and diverse spectrum of aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons [5].

Meanwhile, the strong global dependence on fossil fuels (derived from organic waste rich in hydrocarbons) is essential for actions performed in the civil, industrial, and transportation sectors [17]. However, activities such as the extraction, refining, or transportation of these hydrocarbons routinely (in some cases accidentally) produce contamination on what is considered a global level [4,18]. This contamination can affect broad areas (soils, surface waters, and groundwaters) whose final destinations, due to natural biological and physical processes, are seas and oceans [19]. The marine environment is considered the ultimate and largest sump for petroleum hydrocarbon contaminants. Therefore, combating this contamination problem is essential [20]. Petroleum hydrocarbons (PHCs) are one of the most widespread and heterogeneous organic contaminants affecting marine ecosystems. The contamination of coastal areas by PHCs represents a major challenge for both the ecosystem and human health, requiring urgent, effective, and sustainable remediation solutions [21].

Catastrophic events, such as the spillages from the Sanchi crude oil tanker on the coast of Shanghai in 2018, the Exxon Valdez in 1989 on the coast of Alaska [20], and the Prestige on the coast of A Coruña (Spain) in 2002, have highlighted the importance of microorganisms as bioremediators in environments contaminated with hydrocarbons.

A concept that has gained particular relevance in recent years is ‘One Health’, promoted by the World Health Organization, which highlights the interdependence between human, animal, and environmental health [22,23]. From this perspective, the broad distribution of hydrocarbons in the environment (whether in the air, water, or soil, or as deposits) represents a significant threat to human and environmental health [24].

1.1. Hydrocarbons Present in the Environment and Their Toxicity

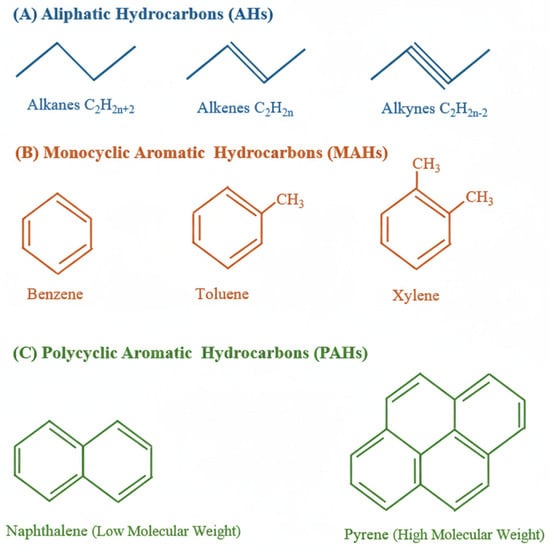

Hydrocarbons are chemically classified as aliphatic hydrocarbons (AHs) and aromatic hydrocarbons (monocyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (MAHs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)). Figure 1 shows some of the structures of aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons.

Figure 1.

Structures of some hydrocarbons: (A) aliphatic hydrocarbons (AHs); (B) monocyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (MAHs); (C) polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), subdivided into those with low molecular weight and high molecular weight.

The toxicity of hydrocarbons affects humans, plants, animals, and microorganisms, with consequences for ecosystem biodiversity and functioning [5], and is closely tied to their availability, influenced by their physical and chemical properties. After they are absorbed, bioavailable chemicals interact with cellular receptors, causing lethal or sub-lethal effects that vary based on the concentration and duration of exposure [25].

The contamination of marine sediments and waters in coastal regions by petroleum hydrocarbons is a widespread problem and represents a major concern due to the potential detrimental consequences for ecosystem biodiversity, functioning, and health [26]. The toxicity of hydrocarbons usually increases with the molecular weight [18,25]. This is the case for PAHs with high molecular weight and boiling point, and therefore low solubility in aqueous solutions [24]. These PAHs are considered particularly dangerous for ecosystems, since they are potentially mutagenic and carcinogenic [25,27,28].

1.2. Mechanisms for Hydrocarbon Biodegradation

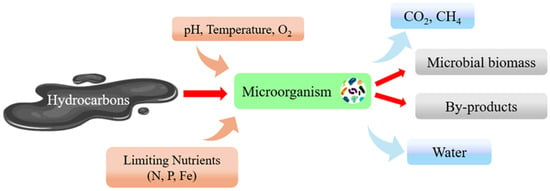

Bioremediation mechanisms can occur under aerobic or anaerobic conditions [29]. They facilitate the degradation of organic contaminants through aerobic or anaerobic respiration and fermentative metabolism, while the transformation and sequestration of heavy metals (which do not degrade) rely on bioaccumulation, biotransformation, and bioleaching activities [30]. Numerous factors influence metabolic processes, such as pH levels, temperature, the availability of oxygen and nutrients (N, P), and the salinity of the medium [14,31,32,33]. These are all key factors for successfully performing bioremediation. As so many variables must be controlled, it is a challenge to compare results obtained in the laboratory with those obtained in situ. Figure 2 illustrates how hydrocarbon molecules are degraded by microbial action, yielding compounds that are less dangerous to the environment.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of bioremediation processes performed by microorganisms.

1.2.1. Aerobic Degradation

The aerobic hydrocarbon degradation processes described by Fritsche and Hofrichter [34] initially require a metabolic strategy to enhance the contact with the contaminant, often by producing biosurfactants (BS) that can solubilise non-polar compounds [35,36]. After this, there is an initial attack of the organic compounds within the cell (a key oxidative process facilitated by intracellular enzymes). This is followed by peripheral degradation, obtaining intermediate compounds, and the final phase involves the biosynthesis of cellular biomass using precursor metabolites such as acetyl-CoA, pyruvate, or succinate derived from the hydrocarbon degradation.

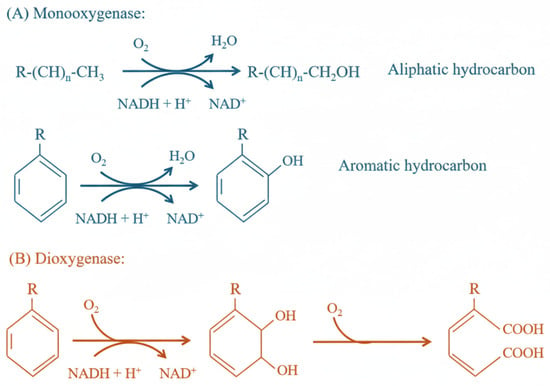

The key oxidative process under aerobic conditions relies on specific oxygenase enzymes that catalyse the incorporation of oxygen into organic compounds, thereby facilitating their cleavage and oxidation. There are two types of oxygenases: monooxygenases, which catalyse the incorporation of only one oxygen atom from the O2 molecule into the substrate, with the simultaneous reduction of the other atom into water; and dioxygenases, which catalyse the incorporation of both oxygen atoms into the organic compound [14,37]. Monooxygenases act on both aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons (Figure 3A), while dioxygenases primarily target aromatic hydrocarbons and, secondarily, open rings, incorporating oxygen atoms into the substrate in both cases (Figure 3B). Regarding the catabolic pathways, aliphatic hydrocarbons are initially oxidised into alcohols, then transformed into fatty acids, and finally channelled into the Krebs cycle to be mineralised into CO2 and H2O. Aromatic hydrocarbons are activated via oxygen addition to form intermediate products, which are subsequently degraded through alternative metabolic routes [14]. Oxidation reactions can only happen inside a bacterial cell, because reduced NADH or NADPH is required, and these degrade rapidly in the extracellular environment. This entails that hydrocarbons must be transported into the cell to be metabolised [5].

Figure 3.

Examples of aerobic mechanisms. (A) monooxygenases insert one oxygen atom in aliphatic or aromatic hydrocarbons; (B) dioxygenases insert two oxygen atoms into aromatic compounds.

1.2.2. Anaerobic Degradation

Oxygen availability is sometimes limited and the final acceptor of electrons under anaerobic conditions can be nitrate (NO3−), sulphate (SO42−), or iron (Fe3+). Under these conditions, biodegradation is slower and often negligible when compared to degradation under aerobic conditions [5]. In anaerobic metabolism, the bacteria lack oxygenase enzymes and therefore use alternative mechanisms, with the most widely studied including fumarate addition, carboxylation, anaerobic hydroxylation, dehydrogenation, and methanogenesis.

The rate of degradation is significantly higher under aerobic conditions, where oxygen acts as the ultimate electron acceptor, compared to anaerobic environments [18,25,38]. When there is not enough oxygen in the medium to support microbial metabolism, hydrocarbon degradation in a state of anaerobiosis can gain significant importance, although it is usually a slower process [39].

While research efforts have traditionally focused on bacteria, the use of fungi (mycoremediation) is gaining increasing relevance because of their ability to produce enzymes capable of transforming several toxic chemicals [40,41,42]. One of the species that stands out is Phanerochaete chysosporium [43]. For example, the effectiveness of fungi has been demonstrated by quantifying the changes in the total mass of crude petroleum in the Mediterranean Sea [44] or by studying some fungi species isolated in the Gulf of Mexico capable of degrading alkanes and PAHs [45]. In some cases, fungi synthesise BS, which enhances the bioavailability of hydrocarbons for other microbial communities like bacteria [46].

1.3. Microorganisms Used as Bioremediation Agents in the Marine Environment

The efficiency of microorganisms in biodegradation processes in coastal waters is closely tied to their ability to function in extremely saline environments [47,48]. Tripathi et al. in 2023 demonstrated that bacterial consortia in marine water were able to reduce aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons by approximately 93% and 85%, respectively [49].

Researchers have identified over 79 bacterial genera capable of degrading petroleum hydrocarbons [50]. Moreover, fungi are believed to be the most diversified group of unicellular eukaryotes on Earth with more than 5 million species, and just 5% have been studied [51,52,53]. Therefore, marine ecosystems may serve as vast sources of novel fungal species, offering great potential for bioremediation. The most significant role of microalgae as bioremediation agents is their synergy with other organisms. Due to the complexity of the bioremediation processes, the removal of hydrocarbons from the environment requires bacterial consortia and not just a single species [5]. For example, the formation of microbial consortia with bacteria such as Pseudomonas, Rhodococcus, or Actinobacter is common and highly effective in hydrocarbon degradation [54,55]. Some of the microorganisms identified in bioremediation processes are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of some of the main genera of bacteria, fungi, and microalgae involved in bioremediation.

According to several studies, bacteria belonging to the genera Klebsiella, Chromobacterium, Pseudomonas, Flavimonas, Enterobacter, and Bacillus have the ability to degrade aliphatic hydrocarbons, with a preference for the long-chain n-alkanes (C12–C31). However, a degradation of aromatic hydrocarbons was not evidenced [19]. These bacteria play a crucial role in the process of hydrocarbon bioremediation or biodegradation, with some species using an aerobic or anaerobic process, depending on the specific microorganism.

Among the bacteria investigated, those belonging to the genus Pseudomonas are particularly relevant, as they can proliferate in aerobic and anaerobic conditions. In addition, they have been isolated from both continental and marine waters, showing a notable ability to adapt to adverse conditions, such as high salinity. The metabolic versatility of Pseudomonas allows them to use aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons as a source of carbon and energy and produce a wide range of enzymes that catalyse hydrocarbon structures into simpler, less toxic compounds. In addition, Pseudomonas use several mechanisms, such as the production of biosurfactants (BS) capable of solubilising non-polar compounds, like those present in petroleum and its derivates [35,94]. Researchers found that one strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, AQNU-1, saw a decrease in its potential degradation ability as the molecular weight of hydrocarbons increased [71]. Another genus described in marine environments is Pseudoalteromonas, which has the ability to grow in waters contaminated with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons [10,72].

Other bacteria studied that have the ability to degrade hydrocarbons belong to the genera Bacillus, Geobacillus, and Thermus [57,58,78,95]. Bacillus is described as a Gram-positive genus of bacteria that can be found in land habitats, fresh water, and marine environments [96]. The microorganisms of this genus are considered halotolerant bacteria due to their ability to multiply in marine waters with high concentrations of sodium chloride [96]. A strain of the Bacillus genus with the ability to degrade diesel was studied by Yousefi-Kebira et al. [59]. Similarly to Pseudomonas, its metabolic activity and its ability to produce BS and enzymes involved in the degradation of hydrocarbons mean this group of bacteria plays a significant role in the bioremediation of environments contaminated with hydrocarbons.

The Halomonas genus has been described as one of the microorganisms that can produce exopolysaccharides listed by Poli et al. in 2006 [65]. Halomonas include moderate halophylic and halotolerant bacteria that, as well as being isolated in marine environments, have been found to be isolated in land environments. Both Pseudoalteromonas and Halomonas were found to be highly capable of degrading hydrocarbons and were isolated from saline environments [66].

Also involved in degrading hydrocarbons are Brevibacterium, a group of aerobic Gram-positive bacteria described for the first time in 1953 by Breed [60]. This genus includes strain DSM20657, named Brevibacterium casei by Pavitran [61]. Some species of Brevibacterium are capable of degrading different types of hydrocarbons, such as paraffins, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and crude petroleum, with a similar action mechanism to the other bacteria considered, in addition to their metabolic activity, synthesis of degrading enzymes, and BS production. All of these features facilitate the emulsion and subsequent degradation of the contaminants.

Marinobacter, which are also hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria, as well as Pseudoalteromonas, belong to the Alteromonadaceae, which are bacteria often found in marine environments. They are Gram-negative bacteria that were described for the first time by Gauthier et al. [68]. A strain that degrades PAHs, Marinobacter geseongensis, was described by Roh et al. [97], isolated in seawater. Its ability to grow in various concentrations of sodium chloride (NaCl) between 1 and 25% w/v was studied. As well as the action mechanisms above, these bacteria have the peculiarity of forming a biofilm on the water-hydrophobic substrate interface, thus favouring their degradation. Some Marinobacter strains can fix nitrogen, which is a significant benefit when they are in environments where their availability has to be limited, such as in eutrophication processes.

Another group of bacteria that degrade hydrocarbons (especially PAHs) is the Thalassospira genus, which are Gram-negative bacteria. It was described and studied by several researchers as bacteria that degrade aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons [75,76,77]. Even though most of the studies on the biodegradation of hydrocarbons have focused on bacteria (prokaryotic microorganisms), some eukaryotes have also been described. Of this group, it is worth mentioning that there are algae, fungi, and yeasts [95]. As a result, we can say that many microorganisms can use different compounds that are environmental contaminants as their sole source of carbon, and their distribution in nature is very broad. However, they are present in low concentrations in areas that are not contaminated, and they usually increase in environments subject to significant impacts of the contaminant [37].

Studies based on the analyses of independent culture techniques to see the changes that take place in marine environments impacted by petroleum spills have shown that, following a contamination by hydrocarbons, the variety of the bacterial community can be significantly hampered due to the limited number of species that degrade hydrocarbons [98,99,100]. These mainly belong to the group of Gammaproteobacteria [1].

It is important to remember that, in most cases, contamination comes from complex mixtures, whereas most studies generally focus on investigating the contaminating compounds individually. Furthermore, the bacterial species that are often found in contaminated areas can have very specific features, such as a tolerance to vanadium, which could be adaptations to this type of contaminants [10].

The research objective was to characterise the bacterial communities inhabiting the coastal waters of Haina Port, San Cristóbal province, amplifying the sections of the 16S rRNA gene and focusing on strains with the ability to degrade hydrocarbons. This is a paramount pollution concern for the Dominican Republic’s coast and surrounding areas, posing a significant threat to the environment and communities. Studies have detected peak hydrocarbon concentrations within the port area and the Haina River, an area attributed to transportation activities and the presence of the Dominican Refinery of Petroleum (Refidomsa) and associated fuel storage facilities [101,102]. This study focused on microbial community composition and environmental context, and evaluated whether bacterial taxa commonly associated with hydrocarbon degradation persist under current environmental conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Water Sampling

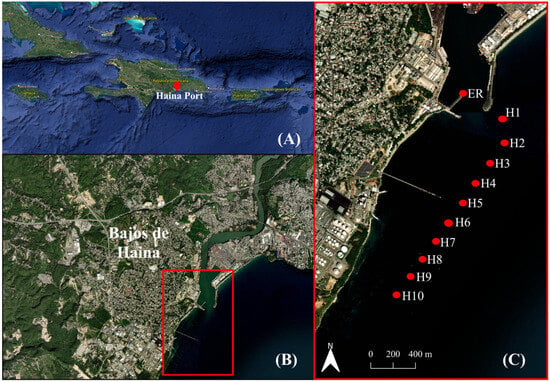

We collected the water samples used for the isolation of the bacteria from Haina Port (September 2024) using sterile containers of 225 mL, collecting from the surface of the current, starting at 18°25′18″ N, 70°01′10″ W and ending at 18°25′18″ N, 70°01′25″ W. A total of 11 sampling points, 2 samples per point, H1 to H10, and 1 in the Haina River estuary (ER), were established, sequentially maintaining a uniform spatial interval of approximately 50 metres, at approximately 0.8 km from the coast to avoid the influence of immediate coastal effluent and direct anthropogenic discharges from the local sewage system. Due to the dynamic sea conditions, logging discrete coordinates for each 50 m interval was technically challenging. However, by maintaining a constant offshore distance of 0.8 km and a steady heading, this transect provides a reproducible spatial framework that accurately delimits the study area. All the samples were collected in sterile conditions and refrigerated at 6 ± 2 °C in the dark until being processed in the laboratory. Sample point H1 corresponds to samples 1 and 2; sample point H2 corresponds to samples 3 and 4; sample point H3 corresponds to samples 5 and 6; sample point H4 corresponds to samples 7 and 8; sample point H5 corresponds to samples 9 and 10; sample point H6 corresponds to samples 11 and 12; sample point H7 corresponds to samples 13 and 14; sample point H8 corresponds to samples 15 and 16; sample point H9 corresponds to samples 17 and 18; and sample point H10 corresponds to samples 19 and 20. We took six additional samples at random during the sampling route to be physically and chemically analysed (P1, P2, P3, P4, P54, P6). The sampling area and the sample points are described in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

(A) Location of Haina Port in the Dominican Republic. (B) Location of the study area. (C) Sample points in Haina Port (Caribbean Sea), H1 to H10. ER corresponds to the sample in the Haina River estuary.

2.2. Physicochemical Analysis

The physicochemical analyses of all six samples taken at random included their pH levels, total organic carbon (TOC), total hydrocarbons (HCs), NO3−, NO2−, NH4+, total Fe, Cu, Co, Mg, total P, suspended solids (SS), and biological oxygen demand (BOD5), which are of particular relevance to the study of microorganisms in aquatic environments.

2.3. Molecular Analysis

The 16S rRNA gene is the DNA sequence coding for bacterial rRNA and is found in the genomes of all bacteria. Its structure is formed by variable regions and conserved regions, with the latter being shared by all bacteria. The variable regions make it possible to identify the different bacteria because of their specificity. The 16S rRNA genetic sequence is the genetic marker used most often to study bacterial taxonomy and phylogeny. The 16S rRNA gene is used to identify bacteria because, although it is greatly preserved in all bacteria, there are also variable regions that act as a unique genetic ‘barcode’ for each species. Sequencing the gene makes it possible to compare the resulting sequences with databases to identify bacteria even if they cannot be cultured in the laboratory, which makes it useful for studies of microbial diversity. The 16S rRNA is an important component of the 30S subunit of a ribosome found in all bacteria and archaea. It is 1500 nucleotides long and contains nine variable regions interspersed between conserved regions. Because the 16S rRNA sequence is ubiquitous in bacteria and archaea, it can be used to identify a wide diversity of microbes within a single sample and single workflow [103].

In this context, bioinformatics plays a complementary role, as it provides analytical tools that make it possible to efficiently interpret the sequences obtained, thus leading to a more accurate identification of bacteria [104].

The procedure to sequence 16S rRNA begins by extracting DNA from the sample or isolated microorganism. Experts then amplify the gene using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique, prepare the library, perform the sequencing, and, lastly, analyse the results obtained. The process described is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Steps to identify bacteria by 16S rRNA sequencing.

2.4. Extracting DNA from the Water Samples

In order to extract metagenomic DNA from each of the points sampled, we followed the protocol established by E.Z.N.A. DNA ® Water DNA Mini Kit Protocol (Omega Bio-tek, Inc., Norcross, GA, USA), filtering the samples using a nitrocellulose filter with a pore size of 0.45 μm and then extracting the total DNA. To quantify the DNA, we used the Minion Oxford Nanopore device (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK). The samples were stored frozen at −20 ± 2 °C [105].

2.5. Amplification and 16S rRNA Sequencing

We sent the genomic DNA products extracted to Novogene (Sacramento, CA, USA) to be processed, to prepare libraries, and for the metagenomic sequencing. The amplicon sequencing analysis of the 16S rRNA gene (ribosomal metagenomics) was performed to determine the bacterial composition of the samples. The hypervariable V3–V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified with the PCR technique using universal primers that are specifically for bacteria:

- Forward: CCTAYGGGRBGCASCAG.

- Reverse: GGACTACNNGGGTATCTAAT

The resulting PCR products were purified, quantified, and then sequenced using the Illumina platform.

2.6. Bioinformatic Analysis

Sequencing libraries were created using the amplified DNA. A PCR was initially performed using specific primers for the V3–V4 region, which had barcodes to tag the sequences and assign them to the original sample. The PCR products with the right size were selected through electrophoresis in a 2% agarose gel. The same number of PCR products from each sample were merged, the ends were repaired, and A tails were added and then bound with Illumina adapter sequences. The grouped libraries were sequenced using the Illumina platform to produce paired-end reads of 250 pb per end, ensuring the depth of sequencing required for the analysis.

Then, the quality of the final libraries was assessed and their effective concentration was quantified using QPCR (a real-time quantitative PCR).

The raw reads were processed as follows:

- Data partitioning. The paired-end reads were assigned to their original samples through the unique barcode. Then, the sequences of the barcode and the primers were removed.

- Assembling the sequences. The overlapped pair-end reads were merged using FLASH (Fast Length Adjustment of SHort reads) [106], a very fast and accurate analysis tool. The assembled sequences were called raw tags.

- Data filtering and quality control. The filtering of the raw tags based on their quality was achieved using the fastp software, version 0.20.1 [107].

- Bioinformatic processing and taxonomic analysis. The bioinformatic analysis of the clean tags was outsourced to the company Biodatec. The processing was performed following the standard workflow for sequencing 16S rRNA amplicons, mainly using the QIIME 2 (v.2023.9) software [108] and related tools.

- Post-sequencing quality control and denoising. Prior to the taxonomic assignment, a quality check was performed on the FASTQ files processed using FastQC (v.0.11.9), summarising the results with MultiQC (v.1.12). The key processing was performed using the DADA2 (v.1.22.O) plugin [109] in QIIME 2 for denoising, merging the reads and removing de novo chimeric sequences. This process generated amplicon sequence variants (ASVs), which represent sequences that are biologically unique.

- Taxonomic and phylogenetic analysis. The ASVs with a similarity threshold of 97% were grouped using VSEARCH (v.2.22.1) [110] to obtain operational taxonomic units (OTUs). The representative sequences were classified taxonomically using a Naive Bayes classifier trained with the SILVA nr v.138.1 database of bacteria and archaea. For the phylogenetic analyses, the representative sequences were aligned using MAFFT (v.7.520) [111] and created a maximum-likelihood tree using FastTree (v.2.1.11) [112]. The end results of the taxonomic identification were displayed using Krona Tools with the psadd (v.0.1.3) package.

2.7. Further Research from the Water Samples

The taxonomic identification provided by 16S rRNA gene sequencing serves as a foundational survey of the microbial community structure. While this approach identifies taxa with documented biodegradative potential, it does not provide direct evidence of active metabolic pathways or functional rates. Consequently, the results presented herein constitute a baseline for microbial presence; further research, including culture-dependent assays, enrichment studies, and metagenomic or transcriptomic analyses, would be required to definitively confirm and quantify the bioremediation capacity of the detected microorganisms.

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical Analyses

The assessment of the physicochemical analyses of the water samples taken from random points in the same study area (P1 to P6) revealed that the pH values ranged from 7.26 at the estuary of the river (P1) to 7.73 at point P6, which are considered normal values. The TOC levels ranged from 0.292 to 0.869 mg/L. These are considered low values, revealing a low organic load in the area. Nitrates (NO3−) ranged from 1.33 to 1.77 mg/L. These are considered low values, revealing that urban waters had a small impact on the sampling area. Meanwhile, nitrites (NO2−) ranged from 0.016 to 0.030 mg/L. These are acceptable values for the area, which could suggest that there is minimal contamination in this site. Ammonium (NH4+) was only found in the P1 sample, which was collected at the Haina River estuary that connects to the coast. The absence of ammonium in the other samples is positive for aquatic life, as this compound is toxic in high concentrations. Low levels of nitrogen species were observed in all cases, which is very positive due to the potential eutrophication issues that high levels could entail. The highest concentration of total Fe was detected in sample P2, at 0.519 mg/L, and could be the result of the area’s industrial activity. Cu was not detected in points P4, P5, and P6. Moreover, in the points where it was detected, it did not reach relevant values. The levels of magnesium detected, between 1133 and 1347 mg/L, are normal for marine waters. The total P levels were low in all samples except P1 (0.2 mg/L). This was expected due to the fertilisers that reach the coast due to the runoff and represents a risk of eutrophication. In addition, the industrial activity in the area can also affect this concentration, although it is not unreasonably high. The values of suspended solids (SS) ranged from 28 to 59 mg/L, which is considered moderate for an area with coastal influence. The BOD5 values were below the detection limit (8.08 mg/L), which reveals a non-existent or minimal presence of biodegradable organic matter in the area. As expected, cobalt was not detected in any of the points sampled by the coast. However, in the P1 sample there was 0.016 mg/L, which could represent an isolated contamination in that area that did not affect the other areas sampled. In general, the physicochemical analyses revealed a low concentration of the compounds analysed in the study area, which is significant when studying the presence of microorganisms that can be strongly impacted by the presence of these compounds. It is particularly important that no metals were detected, as these can be toxic for microorganisms at very low concentrations. The results of the analyses are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of physicochemical analyses performed on six random water samples.

3.2. Results from 16S rRNA Sequencing

The results of this study of Haina Port have revealed the composition and distribution of the bacterial communities in the area. The taxonomic analysis made it possible to identify the studied microorganisms based on the 16S rRNA sequencing performed on 10 coastal points on a phylum level, and to classify them by class, order, family, and genus, determining the dominant groups and their relative share according to the percent abundance.

In view of the sample size and the lack of true biological replication, taxic abundances were characterised using a qualitative comparative approach. While this prevents the application of robust inferential statistics, it provides a foundational survey of the dominant microbial groups present across the sampling transect. Future sampling campaigns incorporating higher spatial replication will be required to statistically validate the ecological patterns observed in this preliminary study.

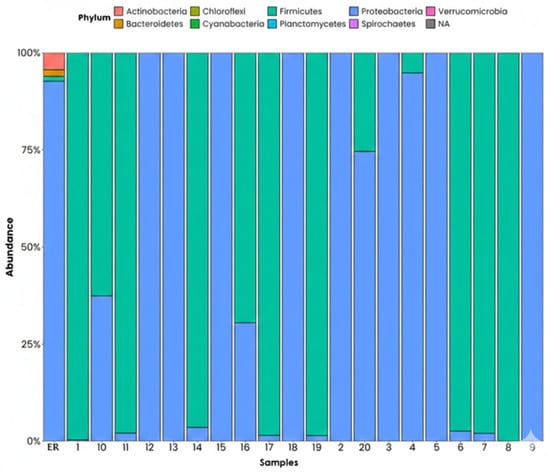

The results obtained on a phylum level (Figure 6) for the different sampling points reveal a variable relative proportion of the bacterial phyla present, which helps understand the fluctuation of the microbial community depending on the environmental conditions of the area studied. The data shows that Proteobacteria is the dominant group, accounting for between 70 and 90% of the community, and this dominance serves as a robust descriptive marker of the microbial community. This phylum is typical of environments impacted by organic contamination, hydrocarbons, heavy metals, and industrial waste, and many of its species can degrade toxic compounds, including hydrocarbons and solvents. The second most abundant phylum is Firmicutes, with its presence ranging from 10 to 50%. This group tends to proliferate in environments with high levels of organic matter, anaerobic conditions, in the presence of spilled hydrocarbons, and around port-related contaminating activities. There are also smaller amounts of Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and other minority phyla. The Actinobacteria usually take part in the degradation of complex compounds. However, their proliferation can be restricted when there is strong microbial competition in that environment. Meanwhile, Bacteroidetes are considered indicators of recent organic contamination, so their presence suggests frequent provisions of waste to the medium.

Figure 6.

Phyla on a phylum level found in the samples, ordered by relative abundance. ER: Haina River estuary; H1: samples 1, 2; H2: samples 3, 4; H3: samples 5, 6; H4: samples 7, 8; H5: samples 9, 10; H6: samples 11, 12; H7: samples 13, 14; H8: samples 15, 16; H9: samples 17, 18; H10: samples 19, 20.

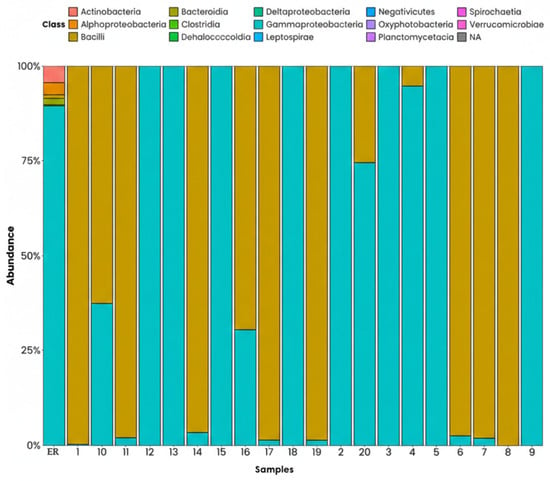

The results of the phylogenetic analysis on a class level show that, in most sampling points, the Gammaproteobacteria are the predominant group, accounting for approximately 70–90% of the relative abundance. This class includes numerous genera known for adjusting to environments contaminated with hydrocarbons, aromatic compounds, heavy metals, and industrial waste, which matches the characteristics of the environment studied. In second place are Alphaproteobacteria, with proportions between 10 and 50% depending on the point assessed. This group is associated with organic compound degradation processes, and some subclasses include microorganisms resistant to saline and chemical stress, which are common conditions in areas with intense industrial activity such as Haina Port.

Clostridia and Bacilli are also present, but to a lesser extent. The Clostridia class is typically associated with anaerobic environments and sediments rich in organic matter, so its presence indicates a low availability of oxygen in certain points. Meanwhile, Bacilli take part in the degradation of organic matter and in the transformation of complex compounds, which reflects specific biodegradative processes in the area. Lastly, the minority classes, represented by Actinobacteria, Bacteroidia, and Verrucomicrobiae, among others, are present in proportions lower than 5%. This reveals a low bacterial diversity in certain points, possibly due to the strong competition exerted by proteobacteria and environmental limitations such as the availability of nutrients or oxygen, or the presence of specific contaminants (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Phyla on a class level, ordered by relative abundance. ER: Haina River estuary; H1: samples 1, 2; H2: samples 3, 4; H3: samples 5, 6; H4: samples 7, 8; H5: samples 9, 10; H6: samples 11, 12; H7: samples 13, 14; H8: samples 15, 16; H9: samples 17, 18; H10: samples 19, 20.

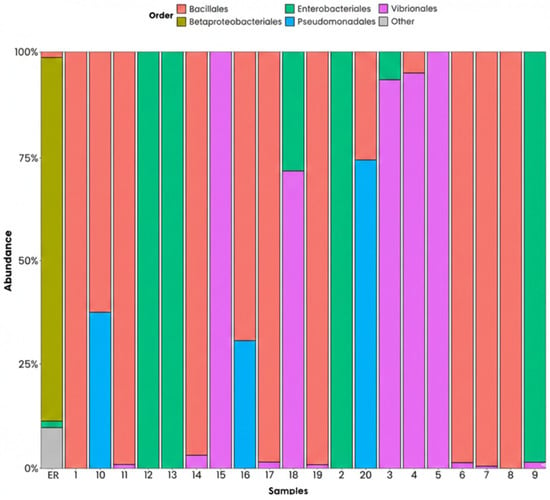

The analysis performed on an order level shows a clear dominance of Bacillales in most of the sampling points, reaching proportions greater than 70%, which suggests a high tolerance to environmental stress and a strong degradative activity in the area. Several points also had a notable presence of Pseudomonadales and Enterobacterales, orders associated with the degradation of hydrocarbons and industrial compounds, and with recent provisions of organic matter, respectively. Likewise, there was a relevant presence of Vibrionales in several points, which indicates possible eutrophication processes and a high availability of nutrients. Meanwhile, Betaproteobacteria and other minority orders were present in reduced proportions, revealing a limited diversity due to the environmental conditions and the competition with dominant groups. As a whole, these patterns suggest that the microbial structure of the port is strongly affected by industrial activities, organic discharges, and the presence of specific contaminants (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Phyla on an order level, ordered by relative abundance. ER: Haina River estuary; H1: samples 1, 2; H2: samples 3, 4; H3: samples 5, 6; H4: samples 7, 8; H5: samples 9, 10; H6: samples 11, 12; H7: samples 13, 14; H8: samples 15, 16; H9: samples 17, 18; H10: samples 19, 20.

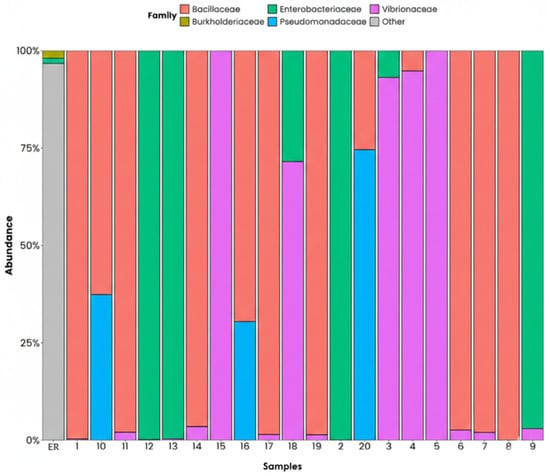

Figure 9 shows the various environmental samples, grouping the identified microorganisms that belong to the different families. The Bacillaceae family appears as the most abundant in most points and this suggests a potential for in situ remediation. However, it is important to note that 16S rRNA gene profiling only allows for taxonomic inference and does not provide direct evidence of functional activity. Therefore, these results should be interpreted as a preliminary indication of degradative potential. Incorporating qPCR of functional markers and microbial enrichment cultures is required to confirm the active role of these communities in hydrocarbon degradation. The Enterobacteriaceae family are the second most abundant in some points studied, with some genera of this family (e.g., Klebsiella, Enterobacter) associated with the degradation of some compounds of petroleum. In addition, their presence indicates an environment contaminated by organic and faecal discharges. The Vibronaceae family stands out in several points. Vibrios are typical of marine environments, but some stand out due to their ability to degrade polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). The Pseudomonadaceae family appears in some points. The Pseudomonas spp. are some of the most well-known worldwide for their ability to degrade complex hydrocarbons, as well as for the production of biosurfactants that have a highly versatile metabolism for the recovery of contaminated areas. The Burkholderiaceae family appears in a minority capacity (less than 5%). This family includes some genera that are potential degraders, such as Burkholderia and Parabuskholderia. The ‘others’ category indicates groups that are not typically associated with degradation processes and thus a possible decrease in the contamination of the environment, which makes the medium less favourable for their growth.

Figure 9.

Phyla analysis on a family level, ordered by relative abundance. ER: Haina River estuary; H1: samples 1, 2; H2: samples 3, 4; H3: samples 5, 6; H4: samples 7, 8; H5: samples 9, 10; H6: samples 11, 12; H7: samples 13, 14; H8: samples 15, 16; H9: samples 17, 18; H10: samples 19, 20.

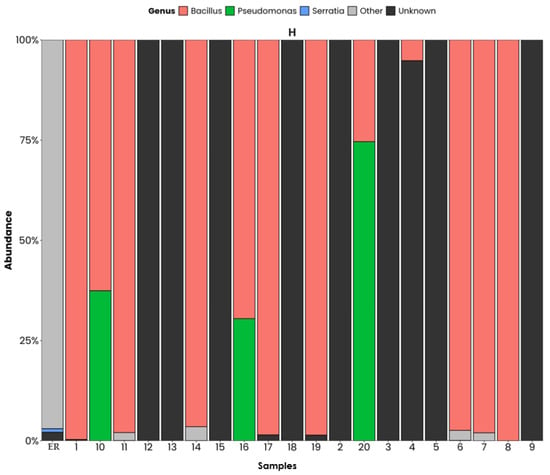

Figure 10 shows the bacterial composition on a genus level for the different sampling points. The bacterial groups that stand out are those with hydrocarbon-degrading potential, with the most abundant being Bacillus in most points, a microorganism known for its high environmental resistance and its ability to degrade linear and aromatic hydrocarbons and produce BS. The Pseudomonas genus appears as the second most abundant genus and is characterised by being one of the most efficient genera for the degradation of PAHs and toxic and persistent compounds. The third most abundant genus is Serratia. This one is only present in one of the sampling points and it is not a common genus in hydrocarbon degradation. Its presence can be an indicator of organic discharges or be associated with contamination of mixed origin. The high proportion of other genera in several samples that are not identified on a genus level can be associated with groups that have not been fully characterised, which may not be related to hydrocarbon degradation processes.

Figure 10.

Phyla on a genus level, ordered by relative abundance. ER: Haina River estuary; H1: samples 1, 2; H2: samples 3, 4; H3: samples 5, 6; H4: samples 7, 8; H5: samples 9, 10; H6: samples 11, 12; H7: samples 13, 14; H8: samples 15, 16; H9: samples 17, 18; H10: samples 19, 20.

4. Discussion

The efficiency of hydrocarbon degradation and its derivatives depends on many factors. The most important ones are those of environmental origin, such as the temperature, nutrient content, or the presence of electron acceptors and substrates, which are crucial for said process to take place [18]. The physicochemical results of the waters of Haina Port show acceptable levels of most of the parameters studied, except for the iron content, which was at higher levels than are allowed for this type of environment. This is in line with the work conducted by Contreras et al. [115], who assessed the waters and sediments of the Haina River and found levels of iron and other heavy metals that were outside the established parameters. However, for work conducted in the Haina River, we must consider that the river ends on the coast (where this study was conducted), meaning it is directly impacted by the contaminants it receives.

The clear dominance of the Proteobacteria phylum, whose presence accounted for 70–90% of most sampling points, coincides with the data reported in other contaminated coastal environments, where this phylum is associated with the degradation of hydrocarbons, heavy metals, and recalcitrant organic compounds [116,117].

The significant presence of Firmicutes (10–50%) reinforces this interpretation, as these microorganisms are usually found in sediments with a high organic load, anaerobic conditions, and a continuous exposure to industrial contaminants [14,118]. Both Proteobacteria and Firmicutes can play a key role in the biodegradation of hydrocarbons, being part of a specialised microbial community that takes hold in environments impacted by anthropogenic activities such as the Haina Port. The prevalence of Bacilli in these zones is likely attributed to their physiological resilience and ability to form resistant endospores, allowing them to survive under the fluctuating environmental stressors typical of port infrastructures [119,120,121,122]. Similar patterns where Firmicutes act as opportunistic responders in hydrocarbon-impacted maritime hubs have been documented on the Brazilian coast [123,124].

On a class level, the predominance of Gammaproteobacteria (70–90%) is consistent with studies performed in areas affected by oil spills and industrial discharges, where this group is associated with genera that are highly efficient at degrading aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons [1]. Meanwhile, Alphaproteobacteria, the second most abundant group, includes bacteria adapted to marine environments subjected to chemical and saline stress, which matches the conditions of the port ecosystem.

On an order and family level, the abundance of Pseudomonadales, Enterobacteriales, Vibrionales, and families such as Pseudomonadaceae, Enterobacteriaceae, and Vibrionaceae coincides with common microbial communities in environments contaminated with hydrocarbons and recent organic matter [120]. These families include genera with specialised metabolic capabilities for degrading hydrocarbons, producing biosurfactants, and adapting to variable conditions of oxygen and salinity.

The strong presence of genera like Bacillus and Pseudomonas represents an additional indicator of chronic contamination, as both are widely recognised for their metabolic versatility and their role in the degradation of hydrocarbons, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) [112,125]. The appearance of minority genera such as Burkholderia suggests the existence of specific niches in the port, possibly linked to sedimentation areas or microenvironments with higher concentrations of recalcitrant contaminants.

Of the bacterial genera found in the area studied, the one that stands out is Pseudomonas, which was described by Varjani et al. [126]. It created a hydrocarbon-utilising bacterial consortium (HUBC) with halotolerant bacteria, specifically Ochrobactrum sp., Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which were found to be good for degrading crude petroleum (3% v/v), with a degradation percentage as high as 83.49%. Furthermore, the Bacillus genus was also found in this study, and in the research conducted by Tao et al. [127], they used a specific co-culture from an endogenous bacterial consortium as well as an exogenous strain of Bacillus subtilis to more effectively accelerate the degradation of crude petroleum. The results obtained in this study match those communicated by Wang C. et al. in 2019 [57], who contend that a bacterial consortium degrades petroleum more efficiently than individual bacteria. They also showed that an autochthonous consortium has the potential to bioremediate crude petroleum spread across a marine ecosystem.

The microbial structure observed reveals that Haina Port has an ecosystem that is subjected to continuous anthropogenic pressure, where the bacterial community has functionally reorganised to respond to the presence of hydrocarbons and other industrial contaminants. This pattern is similar to those reported in ports and industrial coastal areas worldwide, which highlights the need to strengthen environmental monitoring strategies and consider bioremediation approaches that take advantage of the metabolic potential of these microbial communities.

5. Conclusions

This study has identified a significant presence in Haina Port of bacterial genera typically associated with hydrocarbon degradation.

The microbial diversity in this ecosystem is indicative of a bioremediation capacity that warrants further functional validation. As many as eight genera were detected, suggesting the existence of a bacterial consortium with potentially complementary metabolic pathways for the degradation of different types of hydrocarbons. These results provide an opportunity to conduct in vitro bioremediation studies, taking advantage of the native microbiota adapted to the local conditions and the specific contaminants present in the coastal port area.

The results demonstrate that Proteobacteria is the dominant group (70–90%), a phylum whose prevalence is characteristic of marine sediments under chronic pressure from hydrocarbons, heavy metals, and industrial effluents. This dominance is complemented by a significant recruitment of Firmicutes (10–50%), which tend to proliferate in environments with high levels of organic matter, anaerobic conditions, in the presence of spilled hydrocarbons, and around port-related contaminating activities.

Samples 2, 12, and 13 revealed a 100% presence of Enterobacteriaceae, which could indicate waste from direct faecal contamination. This presence, often associated with high organic loading, can alter factors such as the dissolved oxygen levels, pH, and nutrient availability of the marine environment, environmental stressors that likely influence the prevalence of bacteria and overall activity of the hydrocarbonoclastic bacteria in the area. Therefore, environmental policies must be implemented in the area to minimise these contaminants.

As a whole, the findings of this research reveal a microbial system with adaptative features, but which is also vulnerable to continuous anthropogenic pressures in its surroundings. Therefore, we recommend complementing these results with future studies that include functional analyses, an assessment of actual degradation rates, and experimental bioremediation testing in order to move towards sustainable environmental management strategies in Haina Port.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.M. and A.P.-G.; methodology, Y.M., J.D.H.-M., J.N.-P. and M.M.J.; software, Y.M. and V.S.-S.; validation, A.P.-G. and M.M.J.; formal analysis, Y.M., A.P.-G. and M.M.J.; investigation, Y.M. and J.D.H.-M.; resources, Y.M., J.N.-P., J.D.H.-M., M.M.J. and A.P.-G.; data curation, Y.M. and A.P.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.M.; writing—review and editing, Y.M., A.P.-G. and M.M.J.; visualisation, J.N.-P., V.S.-S. and A.P.-G.; supervision, A.P.-G., M.M.J. and I.G.-L.; project administration, M.M.J. and J.D.H.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Fund for Innovation and Scientific-Technological Development (FONDOCYT), Dominican Republic (Grant No.2020-2021-2B2-059), which provided 70% of the funding. The remaining 30% was funded by the Instituto Especializado de Estudios Superiores Loyola (IEESL).

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the citations mentioned, in the text, or in the tables. For more details, contact the corresponding author. The original data presented in the study are openly available in the NCBI BioProject database under accession number PRJNA1402673, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/1402673 (accessed on 21 December 2025), with registration date 14 January 2026.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Instituto Especializado de Estudios Superiores Loyola (IEESL) for the use of their facilities, and W. Maurer and H. Chevalier for their collaboration during this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PHCs | Petroleum hydrocarbons |

| AHs | Aliphatic hydrocarbons |

| MAHs | Monocyclic aromatic hydrocarbons |

| PAHs | Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons |

| BS | Biosurfactants |

| ER | River estuary |

| LOD | Limit of detection |

| TOC | Total organic carbon |

| TPH | Total petroleum hydrocarbon |

| HCs | Total hydrocarbons |

| SS | Suspended solids |

| DBO | Biological oxygen demand |

References

- Yakimov, M.M.; Timmis, K.N.; Golyshin, P.N. Obligate oil-degrading marine bacteria. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2007, 18, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes Sosa, M.B.; Arena Ortiz, M.L. Bacterias y hongos con potencial biodegradador de hidrocarburos en diversos ambientes. In Microbiología Ambiental en México: Diagnóstico, Tendencias en Investigación y Áreas de Oportunidad; Arena Ortiz, M.C., Chiappa Carrara, X., Eds.; UNAM-CONACYT: Mérida, México, 2017; pp. 246–263. [Google Scholar]

- Hazen, T.C.; Prince, R.C.; Mahmoudi, N. Marine Oil Biodegradation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 50, 2121–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Liu, W.; Tian, S.; Wang, W.; Qi, Q.; Jiang, P.; Gao, X.; Li, F.; Li, H.; Yu, H. Petroleum Hydrocarbon-Degrading Bacteria for the Remediation of Oil Pollution Under Aerobic Conditions: A Perspective Analysis. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandolfo, E.; Barra Caracciolo, A.; Rolando, L. Recent Advances in Bacterial Degradation of Hydrocarbons. Water 2023, 15, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayilara, M.S.; Babalola, O.O. Bioremediation of Environmental Wastes: The Role of Microorganisms. Front. Agron. 2023, 5, 1183691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wen, S.; Zhu, S.; Hu, X.; Wang, Y. Microbial Degradation of Soil Organic Pollutants: Mechanisms, Challenges, and Advances in Forest Ecosystem Management. Processes 2025, 13, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezenweani, R.S.; Kadiri, M.O. Evaluating the productivity and bioremediation potential of two tropical marine algae in petroleum hydrocarbon polluted tropical marine water. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2024, 26, 1099–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, L.M.; Rezende, H.C.; Coelho, L.M.; de Sousa, P.A.R.; Melo, D.F.O.; Coelho, N.M.M. Bioremediation of Polluted Waters Using Microorganisms. In Advances in Bioremediation of Wastewater and Pollutes Soil; Murall, M.M.F., Ed.; IntechOpen: Londres, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uad, I. Caracterización Fisiológica y Molecular de Bacterias Degradadoras de Hidrocarburos Aisladas de Fondos Marinos (Del Prestige). Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Granada, Granada, Spain, 2011. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10481/20545 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Megharaj, M.; Naidu, R. Soil and brownfield bioremediation. Microb. Biotechnol. 2017, 10, 1244–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonune, N. Microbes: A Potential Tool for Bioremediation. In Rhizobiont in Bioremediation of Hazardous Waste; Kumar, V., Prasad, R., Kumar, M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beolchini, F.; Dell’Anno, A.; De Propris, L.; Ubaldini, S.; Cerrone, F.; Danovaro, R. Auto- and heterotrophic acidophilic bacteria enhance the bioremediation efficiency of sediments contaminated by heavy metals. Chemosphere 2009, 74, 1321–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, N.; Chandran, P. Microbial Degradation of Petroleum Hydrocarbon Contaminants: An Overview. Biotechnol. Res. Int. 2010, 2011, 941810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, G.O.; Fufeyin, P.T.; Okoro, S.E.; Ehinomen, I.; Biology, E. Bioremediation, Biostimulation and Bioaugmention: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Bioremediation Biodegrad. 2015, 3, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, G.; Saini, R.; Banerjee, T.; Singh, N. Bioaugmentation: A Strategy for Enhanced Degradation of Pesticides in Biobed. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part B 2024, 59, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, K.; Rai, J. Bacterial Metabolism of Petroleum Hydrocarbons. In Biotechnology; Ahmad, M., Ed.; Studium Press: Delhi, India, 2014; Volume 11, pp. 73–93. [Google Scholar]

- Varjani, S.J. Microbial degradation of petroleum hydrocarbons. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 223, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narváez-Flórez, S.; Gómez, M.L.; Martínez, M.M. Selección de bacterias con capacidad degradadora de hidrocarburos aisladas a partir de sedimentos del Caribe colombiano. Boletín Investig. Mar. Costeras 2008, 37, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ron, E.Z.; Rosenberg, E. Enhanced bioremediation of oil spills in the sea. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2014, 27, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dell’ Anno, F.; Rastelli, E.; Sansone, C.; Brunet, C.; Ianora, A.; Dell’ Anno, A. Bacteria, Fungi and Microalgae for the Bioremediation of Marine Sediments Contaminated by Petroleum Hydrocarbons in the Omics Era. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manterola, C.; Rivadeneira, J.; Leal, P.; Rojas-Pincheira, C.; Altamirano, A. One Health. A Multisectoral and Transdisciplinary Health Approach. Int. J. Morphol. 2024, 42, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebov, J.; Grieger, K.; Womack, D.; Zaccaro, D.; Whitehead, N.; Kowalcyk, B.; MacDonald, P.D.M. A framework for One Health research. One Health 2017, 3, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzila, A. Biodegradation of high-molecular-weight polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons under anaerobic conditions: Overview of studies, proposed pathways and future perspectives. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 239, 788–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logeshwaran, P.; Megharaj, M.; Chadalavada, S.; Bowman, M.; Naidu, R. Petroleum hydrocarbons (PH) in groundwater aquifers; An overview of environmental fate, toxicity, microbial degradation and risk-based remediation approaches. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2018, 10, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozada, M.; Marcos, M.S.; Commendatore, M.G.; Gil, M.N.; Dionisi, H.M. The bacterial community structure of hydrocarbon-polluted marine environments as the basis for the definition of an ecological index of hydrocarbon exposure. Microbes Environ. 2014, 29, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Luo, Y.; Teng, Y.; Li, Z. Bioremediation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-contaminated soil by a bacterial consortium and associated microbial community changes. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2012, 70, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Shafy, H.I.; Mansour, M.S.M. A review on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: Source, environmental impact, effect on human health and remediation. Egypt. J. Pet. 2016, 25, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Anno, F.; Brunet, C.; van Zyl, L.J.; Trindade, M.; Golyshin, P.N.; Dell’Anno, A.; Ianora, A.; Sansone, C. Degradation of Hydrocarbons and Heavy Metal Reduction by Marine Bacteria in Highly Contaminated Sediments. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Kumar, M.; Prasad, R. Microbial Action on Hydrocarbons; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2019; ISBN 9789811318405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, J.; Colwell, R. Microbial degradation of hydrocarbons in the environment. Microbiol. Rev. 1990, 54, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKew, B.A.; Coulon, F.; Osborn, A.M.; Timmis, K.N.; McGenity, T.J. Determining the identity and roles of oil-metabolizing marine bacteria from the Thames estuary, UK. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 9, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, F.F.; Rosado, A.S.; Sebastián, G.V.; Casella, R.; Machado, P.L.O.A.; Holmström, C.; Kjelleberg, S.; Van Elsas, J.D.; Seldin, L. Impact of oil contamination and biostimulation on the diversity of indigenous bacterial communities in soil microcosms. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2004, 49, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsche, W.; Hofrichter, M. Aerobic degradation by microorganisms. In Biotechnology Set; Rehm, H.-J., Reed, G., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 144–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cruz, N.U.; Aguirre-Macedo, M.L. Biodegradación de petróleo por bacterias: Algunos casos de estudio en el Golfo de México. In Golfo de México: Contaminación e Impacto Ambiental, Diagnóstico y Tendencias; Botello, A.V., Rendón von Osten, J., Benítez, J.A., Gold-Bouchot, G., Eds.; Universidad Autónoma de Campeche: Campeche, México, 2014; pp. 641–652. [Google Scholar]

- Liporace, F.; Débora Conde Molina, D.; Giulietti, A.M.; Quevedo, C. Optimización de Bioprocesos Integrados a Partir de Cepas Aisladas de Áreas Crónicamente Contaminadas con Hidrocarburos para la Obtención de Biosurfactantes. Rev. Tecnol. Cienc. 2018, 30, 231–241. Available online: https://rtyc.utn.edu.ar/index.php/rtyc/article/view/160 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Madigan, M.T.; Martinko, J.M.; Bender, K.S.; Buckley, D.H.; Stahl, D.A. Brock Biology of Microorganisms, 14th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nagkirti, P.; Shaikh, A.; Vasudevan, G.; Paliwal, V.; Dhakephalkar, P. Bioremediation of terrestrial oil spills. Feasibility Assessment. In Optimization and Applicability of Bioprocess; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 141–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, I.M.; Swannell, R.P.J. Bioremediation of petroleum hydrocarbon contaminants in marine habitats. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 1999, 10, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daccò, C.; Girometta, C.; Asemoloye, M.D.; Carpani, G.; Picco, A.M.; Tosi, S. Key fungal degradation patterns, enzymes and their applications for the removal of aliphatic hydrocarbons in polluted soils: A review. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2020, 147, 104866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, R.; Khardenavis, A.A.; Purohit, H.J. Diverse Metabolic Capacities of Fungi for Bioremediation. Indian J. Microbiol. 2016, 56, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, E. Promising approaches towards biotransformation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons with Ascomycota fungi. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2016, 38, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Miguel, A.; Ravanel, P.; Raveton, M. A comparative study on the uptake and translocation of organochlorines by Phragmites australis. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 244–245, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovio, E.; Gnavi, G.; Prigione, V.; Spina, F.; Denaro, R.; Yakimov, M.; Calogero, R.; Crisafi, F.; Varese, G.C. The culturable mycobiota of a Mediterranean marine site after an oil spill: Isolation, identification and potential application in bioremediation. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 576, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simister, R.L.; Poutasse, C.M.; Thurston, A.M.; Reeve, J.L.; Baker, M.C.; White, H.K. Degradation of oil by fungi isolated from Gulf of Mexico beaches. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 100, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maamar, A.; Lucchesi, M.-E.; Debaets, S.; Nguyen van Long, N.; Quemener, M.; Coton, E.; Bouderbala, M.; Burgaud, G.; Matallah-Boutiba, A. Highlighting the Crude Oil Bioremediation Potential of Marine Fungi Isolated from the Port of Oran (Algeria). Diversity 2020, 12, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, F.E.; Lim, Z.S.; Sabri, S.; Gomez-Fuentes, C.; Zulkharnain, A.; Ahmad, S.A. Bioremediation of diesel contaminated marine water by bacteria: A review and bibliometric analysis. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somee, M.R.; Shavandi, M.; Dastgheib, S.M.M.; Amoozegar, M.A. Bioremediation of oil-based drill cuttings by a halophilic consortium isolated from oil-contaminated saline soil. 3 Biotech 2018, 8, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathi, V.; Gaur, V.K.; Thakur, R.S.; Patel, D.K.; Manickam, N. Assessing the half-life and degradation kinetics of aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons by bacteria isolated from crude oil contaminated soil. Chemosphere 2023, 337, 139264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, J.; Yergeau, E.; Fortin, N.; Cobanli, S.; Elias, M.; King, T.L.; Lee, K.; Greer, C.W. Chemical dispersants enhance the activity of oil- and gas condensate-degrading marine bacteria. ISME J. 2017, 11, 2793–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawksworth, D.L. The fascination of fungi: Exploring fungal diversity. Mycologist 1997, 11, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, M. The fungi: 1, 2, 3 … 5.1 million species? Am. J. Bot. 2011, 98, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amend, A.; Burgaud, G.; Cunliffe, M.; Edgcomb, V.P.; Ettinger, C.L.; Gutiérrez, M.H.; Heitman, J.; Hom, E.F.Y.; Ianiri, G.; Jones, A.C.; et al. Fungi in the marine environment: Open questions and unsolved problems. MBio 2019, 10, e01189-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Karunakaran, E.; Pandahl, J. Botton-up construction and screening of algae-bacteria consortia for pollutant biodegradation. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1349016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernikova, T.N.; Bargiela, R.; Toshchakov, S.V.; Shivaraman, V.; Lunev, E.A.; Yakimov, M.M.; Thomas, D.N.; Golyshin, P.N. Hydrocarbon-Degrading Bacteria Alcanivorax and Marinobacter Associated with Microalgae Pavlova lutheri and Nannochloropsis oculata. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 572931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, R.E.; Méndez, V.; Rodríguez-Castro, L.; Barra-Sanhueza, B.; Salvà-Serra, F.; Moore, E.R.B.; Castro-Nallar, E.; Seeger, M. Genomic and Physiological Traits of the Marine Bacterium Alcaligenes aquatilis QD168 Isolated from Quintero Bay, Central Chile, Reveal a Robust Adaptive Response to Environmental Stressors. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Lin, J.; Lin, J.; Wang, W.; Li, S. Biodegradation of Petroleum Hydrocarbons by Bacillus subtilis BL-27, a Strain with Weak Hydrophobicity. Molecules 2019, 24, 3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, D.; Li, P.; Frank, S.; Xiong, X. Biodegradation of benzo[a]pyrene in soil by Mucor sp. SF06 and Bacillus sp. SB02 co-immobilized on vermiculite. J. Environ. Sci. 2006, 18, 1204–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi Kebria, D.; Khodadadi, A.; Ganjidoust, H.; Badkoubi, A.; Amoozegar, M.A. Isolation and characterization of a novel native Bacillus strain capable of degrading diesel fuel. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 6, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WoRMS. Brevibacterium Breed, 1953. World Register of Marine Species. Available online: https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=559610 (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Pavitran, S.; Sellamuthu, B.; Kumar, P.; Bisen, P.S. Emulsification and utilization of high-speed diesel by a Brevibacterium species isolated from hydraulic oil. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2004, 20, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasai, Y.; Kishira, H.; Harayama, S. Bacteria belonging to the genus Cycloclasticus play a primary role in the degradation of aromatic hydrocarbons released in a marine environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 5625–5633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, S.; Arumugam, A.; Chandran, P. Optimization of Enterobacter cloacae (KU923381) for diesel oil degradation using response surface methodology (RSM). J. Microbiol. 2017, 55, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, D.K.; Kim, D.U.; Kim, D.; Kim, J. Flavobacterium petrolei sp. nov., a novel psychrophilic, diesel-degrading bacterium isolated from oil-contaminated Arctic soil. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poli, A.; Esposito, E.; Orlando, P.; Lama, L.; Giordano, A.; de Appolonia, F.; Nicolaus, B.; Gambacorta, A. Halomonas alkaliantarctica sp. nov., isolated from saline lake Cape Russell in Antarctica, an alkalophilic moderately halophilic, exopolysaccharide-producing bacterium. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2006, 29, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Checa, F.; Toledo, F.L.; El Mabrouki, K.; Quesada, E.; Calvo, C. Characteristics of bioemulsifier V2-7 synthesized in culture media added of hydrocarbons: Chemical composition, emulsifying activity and rheological properties. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 3130–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, M.J. Enrichment of Potential Halophilic Marinobacter Consortium for Mineralization of Petroleum Hydrocarbons and Also as Oil Reservoir Indicator in Red Sea, Saudi Arabia. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 2020, 42, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, M.J.; Lafay, B.; Christen, R.; Fernandez, L.; Acquaviva, M.; Bonin, P.; Bertrand, J.-C. Marinobacter hydrocarbonoclasticus gen. nov., sp. nov., a New, Extremely Halotolerant, Hydrocarbon-Degrading Marine Bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 1992, 42, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakimov, M.; Giuliano, L.; Gentile, G.; Crisafi, E.; Chernikova, T.; Abraham, W.; Lünsdorf, H.; Timmis, K.; Golyshin, P. Oleispira antarctica gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel hydrocarbonoclastic marine bacterium isolated from Antarctic coastal sea water. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2003, 53, 779–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacwa-Płociniczak, M.; Płaza, G.A.; Poliwoda, A.; Piotrowska-Seget, Z. Characterization of hydrocarbon-degrading and biosurfactant-producing Pseudomonas sp. P-1 strain as a potential tool for bioremediation of petroleum-contaminated soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 9385–9395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Yang, G.; Jia, H.; Sun, B. Crude Oil Degradation by a Novel Strain Pseudomonas aeruginosa AQNU-1 Isolated from an Oil-Contaminated Lake Wetland. Processes 2022, 10, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, T.; Morris, G.; Ellis, D.; Bowler, B.; Jones, M.; Salek, K.; Mulloy, B.; Teske, A. Hydrocarbon-degradation and MOS-formation capabilities of the dominant bacteria enriched in sea surface oil slicks during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 135, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahjoubi, M.; Cappello, S.; Souissi, Y.; Jaouani, A.; Cherif, A. Microbial Bioremediation of Petroleum Hydrocarbon-Contaminated Marine Environments. In Recent Insights in Petroleum Science and Engineering; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017; pp. 326–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, A.; Cho, J.C. Thalassolituus marinus sp. nov., a hydrocarbon-utilizing marine bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 2234–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, L.; Ma, Y.; Shao, Z. Thalassospira xiamenensis sp. nov. and Thalassospira profundimaris sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007, 57, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodama, Y.; Stiknowati, L.I.; Ueki, A.; Ueki, K.; Watanabe, K. Thalassospira tepidiphila sp. nov., a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-degrading bacterium isolated from seawater. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2008, 58, 649–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Wang, H.; Li, R.; Mao, X. Thalassospira xianhensis sp. nov., a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-degrading marine bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2010, 60, 1113–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meintanis, C.; Chalkou, K.I.; Kormas, K.A.; Karagouni, A.D. Biodegradation of crude oil by thermophilic bacteria isolated from a volcano island. Biodegradation 2006, 17, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hawash, A.B.; Zhang, X.; Ma, F. Removal and biodegradation of different petroleum hydrocarbons using the filamentous fungus Aspergillus sp. RFC-1. Microbiologyopen 2019, 8, e00619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, I.F. Biodegradation of Kerosene by Aspergillus niger and Rhizopus stolinifer. J. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 2, 31–36. Available online: https://pubs.sciepub.com/jaem/2/1/7/index.html (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Balaji, V.; Arulazhagan, P.; Ebenezer, P. Enzymatic bioremediation of polyaromatic hydrocarbons by fungal consortia enriched from petroleum contaminated soil and oil seeds. J. Environ. Biol. 2014, 35, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obuekwe, C.; Badrudeen, A.M.; Al-Saleh, E.; Mulder, J.L. Growth and hydrocarbon degradation by three desert fungi under conditions of simultaneous temperature and salt stress. Int. Biodeter. Biodegrad. 2005, 56, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, H.; Li, J.; Sun, H. Degradation of PAHs in soil by Lasiodiplodia theobromae and enhanced benzo[a]pyrene degradation by the addition of Tween-80. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 10614–10625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govarthanan, M.; Fuzisawa, S.; Hosogai, T.; Chang, Y.C. Biodegradation of aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons using the filamentous fungus Penicillium sp. CHY-2 and characterization of its manganese peroxidase activity. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 20716–20723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafra, G.; Moreno-Montaño, A.; Absalón, Á.E.; Cortés-Espinosa, D.V. Degradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soil by a tolerant strain of Trichoderma asperellum. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 1034–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krallish, I.; Gonta, S.; Savenkova, L.; Bergauer, P.; Margesin, R. Phenol degradation by immobilized cold-adapted yeast strains of Cryptococcus terreus and Rhodotorula creatinivora. Extremophiles 2006, 10, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sheekh, M.M.; Hamouda, R.A. Biodegradation of crude oil by some cyanobacteria under heterotrophic conditions. Desalin. Water Treat. 2014, 52, 1448–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sheekh, M.M.; Hamouda, R.A.; Nizam, A.A. Biodegradation of crude oil by Scenedesmus obliquus and Chlorella vulgaris growing under heterotrophic conditions. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2013, 82, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.; Kishore, S.; Bora, J.; Chaudhary, V.; Kumari, A.; Kumari, P.; Kumar, L.; Bhardwaj, A. A Comprehensive Review on Microalgae-Based Biorefinery as Two-Way Source of Wastewater Treatment and Biosource Recovery. Clean Soil Air Water 2023, 51, 2200044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nweze, N.; Aniebonam, C. Bioremediation of petroleum products impacted freshwater using locally available algae. Bio-Research 2009, 7, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, A.; Mukherji, S. Treatment of hydrocarbon-rich wastewater using oil degrading bacteria and phototrophic microorganisms in rotating biological contactor: Effect of N:P ratio. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 154, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.G.; Kumar, J.I.N.; Kumar, R.N.; Khan, S.R. Enhancement of pyrene degradation efficacy of Synechocystis sp., by construction of an artificial microalgal-bacterial consortium. Cogent Chem. 2015, 1, 1064193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.; Luan, T.; Wong, M.; Tam, N. Removal and biodegradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by Selenastrum capricornutum. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2006, 25, 1772–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvishi, P.; Ayatollahi, S.; Mowla, D.; Niazi, A. Biosurfactant production under extreme environmental conditions by an efficient microbial consortium, ERCPPI-2. Colloids Surf. B. 2011, 84, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beilen, J.B.; Li, Z.; Duetz, W.A.; Smith, T.H.M.; Wiltholt, B. Diversity of alkanehydroxylase systems in the environment. Oil Gas Sci. Technol. 2003, 58, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguntoyinbo, F.A. Monitoring of marine Bacillus diversity among the bacteria community of sea water. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2007, 6, 163–166. [Google Scholar]

- Roh, S.W.; Quan, Z.X.; Nam, Y.D.; Chang, H.W.; Kim, K.H.; Rhee, S.K.; Oh, H.M.; Jeon, C.O.; Yoon, J.H.; Bae, J.W. Marinobacter goseongensis sp. nov., from seawater. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2008, 58, 2866–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila, J.; Nieto, J.M.; Mertens, J.; Springael, D.; Grifoll, M. Microbial community structure of a heavy fuel oil-degrading marine consortium: Linking microbial dynamics with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon utilization. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2010, 73, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röling, W.F.M.; Milner, M.G.; Jones, D.M.; Lee, K.; Daniel, F.; Swannell, R.J.P.; Head, I.M. Robust Hydrocarbon Degradation and Dynamics of Bacterial Communities during Nutrient-Enhanced Oil Spill Bioremediation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 5537–5545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKew, B.A.; Coulon, F.; Yakimov, M.M.; Denaro, R.; Genovese, M.; Smith, C.J.; Osborn, A.M.; Timmis, K.N.; McGenity, T.J. Efficacy of intervention strategies for bioremediation of crude oil in marine systems and effects on indigenous hydrocarbonoclastic bacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 9, 1568–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almánzar Martínez, L.X.; Díaz Cleto, L.S. Análisis y Determinación de Hidrocarburos y Plomo en la Zona “El Manantial” Ubicada en la Desembocadura del Río Haína, San Cristóbal, República Dominicana. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional Pedro Henríquez Ureña, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, 2024. Available online: https://repositorio.unphu.edu.do/handle/123456789/6119 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Ruiz-Fernández, A.C.; Alonso-Hernández, C.; Espinosa, L.F.; Delanoy, R.; Solares Cortez, N.; Lucienna, E.; Castillo, A.C.; Simpson, S.; Pérez-Bernal, L.H.; Caballero, Y.; et al. 210Pb-derived sediment accumulation rates across the Wider Caribbean Region. J. Environ. Radioact. 2020, 223–224, 106366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CD Genomics. Introduce to 16S rRNA and 16S rRNA Sequencing. CD Genomics Blog. Available online: https://www.cd-genomics.com/blog/introduce-to-16s-rrna-and-16s-rrna-sequencing/ (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Janda, J.M.; Abbott, S.L. 16S rRNA gene sequencing for bacterial identification in the diagnostic laboratory: Pluses, perils, and pitfalls. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 2761–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omega Bio-Tek, Inc. E.Z.N.A.® Water DNA Mini Kit Protocol, [Manual de Laboratorio]; Omega Bio-Tek: Norcross, GA, EE. UU., s.f. Available online: https://www.omegabiotek.com (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Magoč, T.; Salzberg, S.L. FLASH: Fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2957–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Artyomov, N.M.; Asnicar, A.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science with QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rognes, T.; Flouri, T.; Nichols, B.; Quince, C.; Mahé, F. VSEARCH: A versatile open-source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ 2016, 4, e2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoh, K.; Misawa, K.; Kuma, K.; Miyata, T. MAFFT: A novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 3059–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.N.; Dehal, P.S.; Arkin, A.P. FastTree 2—Approximately Maximum-Likelihood Trees for Large Alignments. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 23rd ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 9377-2:2000; Water Quality—Determination of Hydrocarbon Oil Index—Part 2: Method Using Solvent Extraction and Gas Chromatography. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000.

- Contreras Pérez, J.; Mendoza Gómez, C.; Gómez, A. Determinación de metales pesados en aguas y sedimentos del Río Haina. Cienc. Soc. 2004, 29, 38–71. Available online: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=87029103 (accessed on 18 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Head, I.M.; Jones, D.M.; Röling, W.F. Marine microorganisms make a meal of oil. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006, 4, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogales, B.; Lanfranconi, M.P.; Piña-Villalonga, J.M.; Bosch, R. Anthropogenic perturbations in marine microbial communities. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2011, 35, 275–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlas, R.M. Microbial degradation of petroleum hydrocarbons: An environmental perspective. Microbiol. Rev. 1981, 45, 180–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]