Abstract

This study evaluates the performance of several machine learning models in predicting dissolved oxygen concentration in the surface layer of the Mar Menor coastal lagoon. In recent years, this ecosystem has suffered a continuous process of eutrophication and episodes of hypoxia, mainly due to continuous influx of nutrients from agricultural activities, causing severe water quality deterioration and mortality of local flora and fauna. In this context, monitoring the ecological status of the Mar Menor and its watershed is essential to understand the environmental dynamics that trigger these dystrophic crises. Using field data, this study evaluates the performance of eight predictive modelling approaches, encompassing regularised linear regression methods (Ridge, Lasso, and Elastic Net), instance-based learning (k-nearest neighbours, KNN), kernel-based regression (support vector regression with a radial basis function kernel, SVR-RBF), and tree-based ensemble techniques (Random Forest, Regularised Random Forest, and XGBoost), under multiple experimental settings involving spatial variability and varying time lags applied to physicochemical and meteorological predictors. The results showed that incorporating time lags of approximately two weeks in physicochemical variables markedly improves the models’ ability to generalise to new data. Tree-based regression models achieved the best overall performance, with eXtreme Gradient Boosting providing the highest evaluation metrics. Finally, analysing predictions by sampling point reveals spatial patterns, underscoring the influence of local conditions on prediction quality and the need to consider both spatial structure and temporal inertia when modelling complex coastal lagoon systems.

1. Introduction

The application of machine learning techniques to address complex environmental problems has become increasingly important in recent years [1,2,3], particularly due to their ability to model nonlinear relationships, manage large volumes of data, and provide accurate and robust predictions [4,5]. Coastal lagoon ecosystems represent particularly suitable environments for the development and evaluation of advanced methodological approaches. Their pronounced ecological and socioeconomic importance—especially in relation to fisheries and tourism—combined with clearly defined hydrological boundaries, well-structured biological assemblages, and relatively limited spatial extent, make them valuable natural laboratories. At the same time, these systems exhibit strong spatial and temporal variability and are governed by complex interactions among physical, chemical, and biological processes, presenting both significant challenges and important opportunities for integrated ecological assessment and management [6,7,8,9,10]. Accurate prediction of key parameters such as chlorophyll a and dissolved oxygen concentrations is critical for the effective management and conservation of coastal lagoons, where eutrophication and hypoxic events frequently threaten ecological stability and ecosystem services [7,11,12].

However, the collection of complete time series of key parameters and the quality of data in these environments are often compromised by several limitations. These include the logistical complexity of continuous monitoring, the technical difficulties associated with maintaining sensors in extreme and changing environmental conditions, and the economic and operational constraints that limit both the number of measuring stations and sampling frequency [9,13,14,15].

Despite the difficulties mentioned above, several studies have shown that the application of machine learning algorithms can substantially enhance the prediction of critical parameters in coastal lagoons compared to traditional linear models and other classical techniques. As examples we can mention how Béjaoui et al. (2018) [16] projected the trophic state of the Ghar El Mehl lagoon (Tunisia) based on the analysis of a Random Forest model built solely from information on physical and chemical water parameters, or Concepcion et al. (2021) [17], who applied machine learning models to concentrations of nutrients, dissolved oxygen, chlorophyll a, trace metals, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons to produce a classification of the chemical status of Portuguese marine transition ecosystems, including estuaries and coastal lagoons. In Simonetti et al. (2024) [18], a Random Forest model achieved an accuracy of 91% in classifying dissolved oxygen levels and 86% in identifying severe hypoxia events, using the Orbetello lagoon in Italy as a test case, and Zennaro et al. (2024) [19] investigated the potential of machine learning and deterministic models to predict hypoxia events in the Venice lagoon, also in Italy. More recently, Mauricio et al. (2025) [20] have applied machine learning models to assess water quality in the Jacarepaguá lagoon system, a complex of four interconnected lagoons in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, focusing on biochemical oxygen demand (BOD). Recent studies have applied data-driven methods to support the integrated management of the Mar Menor lagoon. Satellite-based machine learning has enabled accurate monitoring of water quality [11,21], the detection of macroalgal blooms [22], and the forecasting of streamflow at key inflow points [23]. Meanwhile, deep-learning approaches have been employed to predict the dynamics of chlorophyll a and dissolved oxygen [24,25]. In parallel, digital twin-oriented frameworks integrating sensing and analytics have been proposed, building on earlier local contributions [26,27]. Despite these contributions, a major limitation remains: the lack of a unified methodological framework that analyses the importance of spatiotemporal variability and lags in pressure-response relationships between different variables. The fragmentation of studies across different objectives, data sources, and modelling strategies limits the general applicability of the results, particularly in highly heterogeneous coastal lagoon systems with delayed responses.

So, given this complexity associated with coastal lagoon ecosystems and the limited availability of complete and high-quality data, it is necessary to evaluate different methodological approaches that allow adaptation to these constraints, maximising the accuracy of the results obtained. Although the literature has demonstrated the effectiveness of machine learning approaches in these environments, most studies rely on standard algorithms without systematically assessing alternative methodologies or their performance under pronounced spatiotemporal variability. Moreover, management applications require not only accurate but also robust and generalizable near-term predictions under realistic monitoring conditions. Methodological choices including model selection, predictor design, and evaluation strategies can strongly influence predictive skill and transferability to real-world settings. Consequently, modelling approaches must be assessed in terms of their behaviour under noise, missing data, nonlinear dynamics, and strong spatiotemporal heterogeneity. Comparative evaluation of different techniques is therefore essential to identify solutions that achieve an optimal balance between accuracy, robustness, and computational efficiency.

In this context, the primary objective of this study is to assess the performance of various machine learning models in predicting the values of different physical-chemical parameters in the surface layer of the Mar Menor water column, by applying different experimental designs that include delay times in the response of the dependent variable to the main environmental factors and various spatial scales. In addition, it seeks to explore and compare different methodologies that allow for the optimisation of the results obtained. To this end, a total of eight models have been tested. The models used include linear regression techniques such as Ridge regression, Lasso regression, and Elastic Net, which incorporate regularisation to improve generalisation and avoid overfitting. The k-nearest neighbours (KNNs) model, based on the distance between data points, was also employed, as well as regression tree-based approaches, such as Random Forest (RF) and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), which utilise ensemble and boosting techniques to enhance accuracy. Finally, a model based on support vector machines (SVRs) with a radial kernel was tested, capable of handling nonlinear relationships in the data. All models correspond to supervised learning techniques in their regression form, as the objective is to predict numerical variables. The application of these techniques will not only enable the comparison of the predictive capacity of different models but also facilitate the determination of the most effective methodologies to enhance the accuracy and robustness of the results.

The paper includes a brief explanation of the theory behind the algorithms used. It then presents the area of study along with the databases used and the experimental design. From there, it summarises the methodology followed to construct the predictive models and presents the results obtained by the models in the different experiments, comparing them and highlighting the most accurate models in each one. Finally, the results obtained are discussed from a more ecological point of view.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The coastal lagoon of the Mar Menor has been used as a case study to apply the different models described. This lagoon is one of the largest in the Mediterranean and has a long series of data derived from various projects and research works carried out in the lagoon since the 1980s [11,12,28,29].

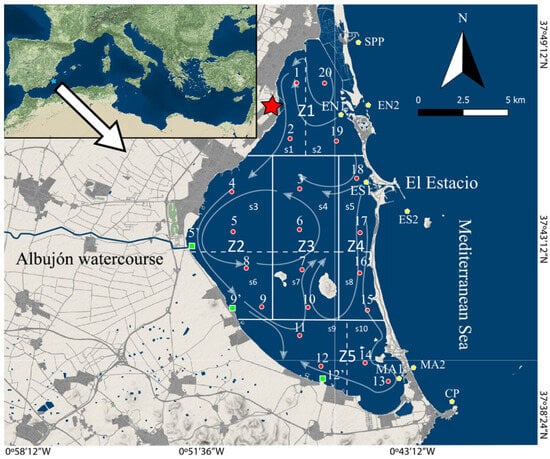

The Mar Menor is a hypersaline coastal lagoon located in the Region of Murcia (Spain), separated from the Mediterranean Sea by a strip of land 22 km long and between 100 and 1200 metres wide, called La Manga del Mar Menor (Figure 1). It covers an area of 136 km2, with an average depth of 4.4 metres and a maximum depth of 7 metres [30].

Figure 1.

Mar Menor monitoring system stations, sectorisation (Z: zone, s: sector), and main currents. The red dots indicate the initial sampling points of the monitoring system (1997). The yellow pentagons indicate the stations added in 2009, and the green squares those added in 2017. The red star indicates the location of the AEMET weather station. The arrows correspond to the dominant currents in the Mar Menor determined by oceanographic modelling [12,30].

This ecosystem, traditionally considered ologotrophic, has withstood a growing influx of nutrients from agricultural activity from the 1990s to the present, demonstrating a great homeostatic capacity [29] whithout any hypoxia event registered until 2019. However, in 2016, this resistance was abruptly interrupted when a conspicuous change in water quality was recorded [11,15]. Since then, after a quick recovery in 2018, to the present, the evolution of the Mar Menor has been marked by several torrential rain events (DANAs), new eutrophic crises, and the occasional appearance of hypoxic pockets, with the resulting deterioration of water quality and occasional mortality of flora and fauna followed by relatively long unstable equilibria periods of good water quality and recovered biological assemblages [11,12,15].

In this context, the Autonomous Community of the Region of Murcia has addressed this issue through various measures that promote the protection and conservation of this emblematic ecosystem. Among these, the measure approved in November 2019 stands out, which established a system for continuous monitoring of the environmental and ecological parameters of the Mar Menor [15]. Thanks to this system, and to previous studies conducted in the lagoon by the “Ecology and Management of Coastal Marine Ecosystems” research group at the University of Murcia, sufficient data have been collected for the preparation of this work. The high environmental and biological heterogeneity of the Mar Menor, its restricted connectivity with the Mediterranean, the strong influence of the drainage basin, and the multiplicity of uses that take place there, and its complex self-regulation and homeostasis mechanisms make this lagoon an ideal case study for examining the ability of predictive models to capture complex nonlinear relationships, synergies, or cumulative effects of different variables or among ecological processes, stochastic meteorological forcing, and the dynamics of eutrophic or hypoxic episodes aggravated by torrential rains, potentially intensified by climate change and at different spatial scales.

The sampling points inside the lagoon are distributed across 10 sectors nested in 5 zones, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of sampling points within the Mar Menor by zone and sector.

2.2. Datasets

The data used in this study can be classified into the following two types: physicochemical, which consist of measurements related to the physicochemical parameters of the Mar Menor water, such as salinity, water temperature, chlorophyll a concentration, and transparency; and meteorological data, which include records of atmospheric parameters such as air temperature, relative humidity, and pressure, among others.

To test the different models, this study used the concentration of dissolved oxygen measured as a percentage in the surface layer of the water column as the study variable. This variable is essential in monitoring and follow-up studies in the lagoon, as it is the critical factor in dystrophic crises in which the appearance of hypoxia phenomena leads to large-scale mortality of organisms, either locally or throughout the entire ecosystem. These crises not only jeopardise the ecological integrity of the ecosystem, but also cause serious social alarm with significant socioeconomic repercussions due to their adverse effects on tourism and fishing, in addition to being key to the conservation of critical and highly valuable species such as the noble pen shell (Pinna nobilis Linnaeus, 1758) and syngnathids such as the seahorse (Hippocampus guttulatus Cuvier, 1829).

Biophysical data have been monitored using a multiparameter oceanographic probe model YSI EXO2 (YSI Incorporated, Yellow Springs, OH, USA) equipped with sensors. The probe has eight sensors that provide data on pH, dissolved oxygen, chlorophyll a concentration, temperature, turbidity, dissolved organic matter, conductivity, and depth. The measurement process involves manually lowering the probe to the seabed at each of the 26 sampling points within the Mar Menor. Probe measurements were compiled into depth-resolved profiles for each variable at all sampling stations. Considering the mean lagoon depth (4.5 m) and the predominantly wind-driven circulation in the Mar Menor [30], the water column was divided into two layers as follows: a surface layer extending to 1.5 m depth, influenced by wind and wave forcing, and a bottom layer defined as the 0.5 m immediately above the seabed not affected by maximum waves, influenced by sediments and benthic processes. For each layer, values were calculated as the mean of observations within the corresponding depth interval, yielding representative bulk conditions while minimising small-scale variability associated with air–water interactions, turbulence, sediment resuspension, and potential sensor disturbance. The use of fixed depth intervals ensures consistency across stations with varying total depths. The biophysical data set comprises 4826 records from sampling points in each of the sampling campaigns, sorted by date, and conducted every two weeks from September 2016 to September 2024.

The meteorological data were provided by the State Meteorological Agency (AEMET) station whose location is shown in Figure 1. Hourly data have been collected from 1 January 1990 to 31 December 2023, for the following meteorological variables: wind speed and direction, temperature, pressure, radiation, precipitation, cloud cover, and relative humidity. To merge both data sets, the following daily aggregate calculations were made on the meteorological variables:

- -

- For the variables wind speed and direction, cloud cover, temperature, pressure, and relative humidity, the daily average has been calculated.

- -

- For the variables evaporation, precipitation, and solar radiation, the total daily cumulative sum has been calculated.

Finally, the oceanographic and meteorological datasets were merged, retaining all physicochemical observations and adding the meteorological record corresponding to each sampling date. In this way, all sampling stations within a given campaign share the same meteorological values, assuming that meteorological conditions are more homogeneous than those of the water column at the spatial scale of the study and standardising small-scale temporal variability. Table 2 shows a summary of the variables contained in the final dataset.

Table 2.

Description of the environmental and meteorological variables used in the study.

2.3. Predictive Models

2.3.1. Ridge Regression

Ridge regression is a regularisation technique that modifies the standard least squares method by introducing an L2 penalty term [31]. The coefficients are therefore estimated by minimising a penalised residual sum of squares (Equation (1)).

The second component, , is a shrinkage penalty. It is smallest when the coefficients (βj) are close to zero, thereby shrinking the estimates towards zero but without forcing them to be exactly zero. The regularisation parameter, λ, governs the trade-off between the model fit (the RSS term) and the magnitude of the coefficients. When λ → 0, the penalty’s influence vanishes, and the Ridge estimates become identical to those of ordinary least squares. Conversely, as λ → ∞, the penalty dominates, forcing the coefficient estimates to approach zero. As in Lasso regression, the tuning parameter λ is selected through k-fold cross-validation.

2.3.2. Lasso Regression

Lasso (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) is a regularisation method that performs both coefficient shrinkage and automated variable selection [32]. It operates by finding the coefficients (β) that minimise an objective function comprising the residual sum of squares (RSSs) and an L1 penalty term (Equation (2)).

The Lasso model is characterised by a single hyperparameter, λ ≥ 0, which controls the strength of the penalty. As λ increases, the penalty term becomes more significant, leading to greater shrinkage of the coefficients. When λ = 0, the Lasso estimates reduce to those of ordinary least squares. As λ → ∞, the coefficients are driven towards zero, potentially eliminating some predictors from the model.

The tuning parameter λ is a critical hyperparameter that is not estimated from the data directly. Instead, it is selected through a procedure known as k-fold cross-validation. This process ensures that the chosen λ value yields a model with strong predictive performance on unseen data, thus mitigating the risk of overfitting.

2.3.3. Elastic Net

Elastic Net regression [33] is a regularised method that linearly combines the L1 and L2 penalties of the Lasso and Ridge models. The objective is to find the coefficients (β) that minimise the following loss function (Equation (3)).

The penalty is a weighted average of the Ridge and Lasso penalties. The inclusion of the factor on the Ridge component is a mathematical convenience that simplifies the computation of the gradient during optimisation.

The Elastic Net model features two hyperparameters that must be tuned:

α: This is the mixing parameter, which takes values in the range [0, 1]. It dictates the blend of penalties:

- -

- If α = 1, the model is equivalent to Lasso regression.

- -

- If α = 0, the model is equivalent to Ridge regression.

λ: This parameter (λ ≥ 0) governs the overall magnitude or strength of the penalty term. Larger values of λ result in greater coefficient shrinkage.

The optimal values for α and λ are determined through k-fold cross-validation, ensuring that the model generalises well to unseen data.

2.3.4. K-Nearest Neighbours

K-nearest neighbours (k-NNs) is a fundamental non-parametric, instance-based algorithm used for regression tasks [34]. Its core principle is to predict the target value, 0, for a new data point, x0, by averaging the values of its closest neighbours in the feature space.

The algorithm first identifies the set of its k-nearest neighbours from the training data, which we denote as N0. A chosen distance metric, such as Euclidean or Manhattan distance, quantifies this nearness. Once the neighbours in N0 are identified, the predicted output 0 is calculated as the average of their corresponding target values (yi).

The primary hyperparameter, k, is a critical choice, typically optimised using cross-validation to control the model’s flexibility.

2.3.5. Random Forest

Random Forest is a powerful ensemble learning method used for regression tasks that builds upon the principle of bootstrap aggregating or ‘bagging’ [35]. The algorithm constructs a multitude of decision trees (B) on distinct bootstrap samples of the training data.

A key innovation of Random Forest is that it introduces an additional layer of randomness to decorrelate the trees. When constructing each tree, at every candidate split, only a random subsample of m predictors is considered from the complete set of p predictors (where m < p). This step prevents a few strong predictors from dominating the structure of all the trees, thereby reducing the variance of the overall model.

The final prediction for a new observation, x, is obtained by averaging the predictions from all B individual trees. This process of averaging many decorrelated trees results in a highly robust and accurate model.

Regularised Random Forest (RRF) extends the conventional Random Forest framework by incorporating a penalization mechanism in the feature selection process to reduce overfitting and promote model parsimony [36]. During the construction of each individual tree, the algorithm penalises the selection of new predictor variables when the associated improvement in the regression split criterion (e.g., reductions in squared error or variance, expressed as decreases in SSE or MSE) is not substantially greater than that achieved by variables selected at preceding nodes within the same tree. This regularisation strategy encourages reuse of a smaller and more stable subset of predictors, making RRF particularly suitable for applications with high multicollinearity or where robust feature selection is required.

2.3.6. Extreme Gradient Boosting

Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) is a highly efficient and scalable implementation of the gradient boosting framework, renowned for its predictive accuracy and computational speed [37]. Like all boosting methods, XGBoost builds a predictive model in a sequential, additive manner. It iteratively adds new weak learners (typically decision trees), where each new tree is trained to correct the errors of the preceding ensemble.

More formally, the model learns in stages. The prediction at step t is updated from the prediction at the previous step t − 1 by adding a new tree, ht(x), scaled by a learning rate, η (Equation (4)).

Unlike standard Gradient Boosting, which often fits trees to the simple residuals, XGBoost fits each new tree to the “negative gradient” of a specified loss function.

A key distinction of XGBoost is its sophisticated, regularised objective function, which is minimised at each step. This objective includes a penalty term, Ω, to control for model complexity and prevent overfitting (Equation (5)).

where the regularisation term Ω (ht) (Equation (6)) penalises both the number of leaves in the tree (T) and the magnitude of the leaf weights (w).

This dual penalty, combined with significant engineering optimisations such as parallelised tree construction and cache-aware algorithms, makes XGBoost a robust and powerful algorithm for a wide range of regression problems.

2.3.7. Support Vector Regression (SVR) with RBF Kernel

Support vector regression (SVR) is a regression methodology derived from the principles of support vector machines [38]. Unlike traditional regression methods that aim to minimise the error for all data points, SVR’s core objective is to find a function that is as ’flat’ as possible. In this context, ‘flat’ refers to a low-complexity function obtained by minimising the norm of the weight vector (i.e., controlling the magnitude of the coefficients in the feature space) while tolerating errors within a specified margin, known as the ϵ-insensitive tube. Data points falling within this tube do not contribute to the loss function, making the model robust to noise.

Formally, SVR solves the following convex optimisation problem (Equation (7)). It seeks to minimise the model complexity (represented by the norm of the weight vector, w) and the penalised errors of points lying outside the ϵ-tube.

Here, C > 0 is a regularisation parameter controlling the trade-off between model flatness and the tolerance for errors. At the same time, ξi and are slack variables representing the magnitude of error for points outside the ϵ-tube.

To model complex nonlinear relationships, SVR employs the ’kernel trick’. This technique implicitly maps the input data into a higher-dimensional feature space where a linear relationship can be found, without ever computing the transformation explicitly. The radial basis function (RBF) kernel (Equation (8)) is a popular choice for this purpose.

The flexibility of the RBF kernel, governed by the hyperparameter γ, allows SVR to capture intricate patterns in the data, making it a powerful tool for nonlinear regression problems.

2.4. Standardisation Method

Possible outliers were reviewed and placed in the context of the time series data to detect possible errors, confirming that in all cases they were real values produced by extreme weather events (storms and DANAs), and were therefore retained in the data matrix. To standardise the predictor variables, the Z-score method has been used. This method adjusts each variable in a data set so that it has a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one (Equation (9)), where Z is the standardised value of the variable, x is the value of the variable, µ is the mean of the variable, and σ is the standard deviation. Standardisation by Z-score enables all variables to be compared and analysed on the same scale, facilitating interpretation and enhancing the performance of machine learning algorithms.

2.5. Training and Test Partition

A chronological division of the data has been chosen, so that the first 80% of the data will be used to train the models, and the remaining 20% will be used as test data to evaluate the predictive capacity of the trained models. Data standardisation is carried out after the sliding window transformation following these steps:

Training data are standardised by Z-score (Equation (9)), saving the means and standard deviations of each of the variables.

Test data are standardised using the Z-score formula, but applying the means and standard deviations of the training set. This measure serves to put the test data in the context of the training data, ensuring consistency, preventing information leakage, and promoting the generalisation of the model to new data.

2.6. Sliding Window Transformation

Given that the objective is to predict the concentration of dissolved oxygen as a percentage of saturation in the surface layer at a future point in time, the models constructed must be capable of predicting based on past observations. Furthermore, each variable can have lagged effects that manifest themselves at different time scales. This requires the creation of lagged variables, i.e., the observations of the predictor variables must be delayed by a specific period. As explained in Section 2.2, the physicochemical data have a fortnightly time frequency, while the meteorological data have a daily frequency. When combining both databases, the fortnightly frequency of the physicochemical data has been maintained; however, the daily data from the meteorological database can be used to create lagged variables between the fortnightly intervals that separate the physico-chemical variable records. The criteria for creating lagged variables have been as follows:

- -

- For physicochemical variables, the time instants chosen were t and t − 1, corresponding to the day of the prediction (t) and the day of the previous sampling campaign. This represents a delay of approximately 15 days in the case of t − 1.

- -

- For meteorological variables, the time instants chosen were t, t − 1, t − 2, ... and t − 7, which correspond to the day of the forecast (t) and the previous 7 days.

The temporal separation between training and prediction data was applied prior to the sliding window transformation, and lagged predictors were subsequently generated independently for each subset, ensuring a realistic forecasting setup.

The introduction of temporal lags implicitly assumes that the underlying physicochemical relationships governing cause–effect interactions remain constant; however, the response times driven by seasonal conditions, interacting processes, or cumulative effects can change. For instance, runoff generation may depend on antecedent moisture conditions and the time elapsed since previous rainfall events, whereas the response of primary production to nutrient inputs can vary seasonally. In the latter case, seasonality is partially encoded through meteorological covariates (e.g., temperature and solar radiation), and the use of multi-year training data enables models to learn season-dependent responses. By contrast, accurately capturing runoff dynamics may require the explicit inclusion of additional state variables, such as soil saturation or inter-event rainfall timing, to further enhance predictive performance.

2.7. Experimental Design

Coastal lagoons are highly heterogeneous systems, both spatially and in terms of their temporal fluctuations, with significant interactions between both factors [9]. Natural phenomena can exhibit different scales of spatiotemporal variability. Spatially, hypoxia events, such as those considered in this study, can affect relatively small areas for a short period or more extensive regions, including the entire ecosystem (e.g., a coastal lagoon). To assess the effectiveness and capacity of the models to make predictions at different scales, we chose to work with time series from all sampling points within the lagoon and different machine learning models for two case studies, considering different time lags in the physicochemical variables:

1. Experiment L0–L7: The dataset used for this experiment consists of records of physicochemical variables on the day of the prediction and records of meteorological variables on the day of the prediction and the previous seven days. With the time delays applied in this case, the dataset for this experiment consists of 4826 records with 98 predictor variables.

2. Experiment L1–L7: The dataset used for this experiment consists of the same records of variables as in Experiment L0–L7, but the records of the physicochemical variables from the previous sampling campaign (approximately 14 days earlier) have also been added. With the time delays applied in this case, the dataset for this experiment consists of 4826 records with 123 predictor variables.

2.8. Feature Selection

The generation of time-lags for all predictor variables substantially increases the dimensionality of the feature space, particularly in Experiment L1–L7, which resulted in 123 predictors. Moreover, lagged variables are often highly autocorrelated, leading to increased redundancy and collinearity among inputs. To improve model efficiency and stability, feature selection was therefore applied to the training dataset. For all models except Lasso, which performs embedded variable selection, recursive feature elimination (RFE) [39] was employed. RFE iteratively fits a model using all available predictors, removes the least informative variables, and evaluates performance at each step until an optimal subset is identified. This approach is especially suitable for models without inherent feature selection, as it reduces redundancy while retaining predictors that enhance cross-validated performance.

2.9. Hyperparameter Selection

The resampling method used was cross-validation of 5 folds with five repetitions. This method essentially involves dividing the data set into distinct subsets, performing the analysis on one subset (the training set), and validating the analysis on the other (the test set). This is repeated several times, using different divisions of the data in each iteration. The objective is to evaluate the model’s performance robustly, thereby avoiding problems such as overfitting.

Table 3 shows the grid of hyperparameters used in the cross-validation search for each of the models.

Table 3.

Hyperparameter grid used for each model.

2.10. Performance Metrics

To compare the performance of the models, the following error metrics were used: RMSE (root mean square error), MAE (mean absolute error), and R2 (coefficient of determination) [40]. These metrics were calculated for both training and test predictions to identify the best models and detect cases of overfitting. In addition, RMSE was prioritised over MAE and R2, as it tends to exaggerate the effect of larger errors.

- -

- RMSE (root mean squared error): It is used to measure the average difference between the values predicted by a model and the actual values (Equation (10)),

- -

- MAE (mean absolute error): Measures the average magnitude of errors without considering their direction (Equation (11)).

Unlike RMSE, MAE does not penalise large errors more than small ones.

- -

- R2 (coefficient of determination): This is a statistical measure that indicates how well a model explains the variability of the data (Equation (12)),

2.11. Wilcoxon Paired Test with Benjamini–Hochberg Adjustment

The Wilcoxon test [41] for paired samples is a non-parametric test that evaluates whether there are significant differences between two related samples, without assuming that their distributions follow a particular shape. It is based on differences in positions (ranges) and is particularly useful when the data do not follow a normal distribution. However, when performing multiple statistical comparisons, the risk of Type I errors increases, i.e., declaring a significant difference when in fact there is none. To control the risk of false discoveries, the Benjamini–Hochberg [42] adjustment is used, which regulates the false discovery rate (FDR) and offers a balance between statistical power and protection against false positives.

2.12. Development Environment

The programming language used to carry out all the methodology, data import, visualisation, model configuration, and analysis of the results was R (Version 4.1.2), in the RStudio environment (Version 2025.09.2+418). The most important packages that were necessary to carry out the work were readxl: Excel files reading (Version 1.4.3) [43]; dplyr: data manipulation (Version 1.1.4) [44]; ggplot2: data visualisation (Version 3.5.1) [45]; VIM: analysis and imputation of missing values (Version 6.2.2) [46]; caret: training and evaluation of machine learning models (Version 6.0-93) [47] (all models have been implemented with this package); and shiny: interactive applications deployment (Version 1.7.4.1) [48]. Table 4 shows the additional packages required to implement each model, along with the caret package.

Table 4.

Packages required for model implementation.

3. Results

3.1. Feature Selection

Table 5 shows the number of predictor variables selected by each model after applying the variable selection techniques mentioned in Section 2.8. In addition, Table 6 and Table 7 mark with an X which variables have been chosen by the models in each of the case studies, highlighting with shading the rows with the variables that all models have selected. In total, twenty predictor variables have been chosen by all models after the selection process.

Table 5.

Number of variables selected for each model in each experiment.

Table 6.

Physicochemical variables selected by each model, marked with an X in each case. Variables selected in all cases are highlighted by shading and their rows.

Table 7.

Meteorological variables selected by each model, marked with an X in each case. Variables selected in all cases are highlighted by shading their rows.

3.2. Model Performance in the Cross-Validation Process (Training)

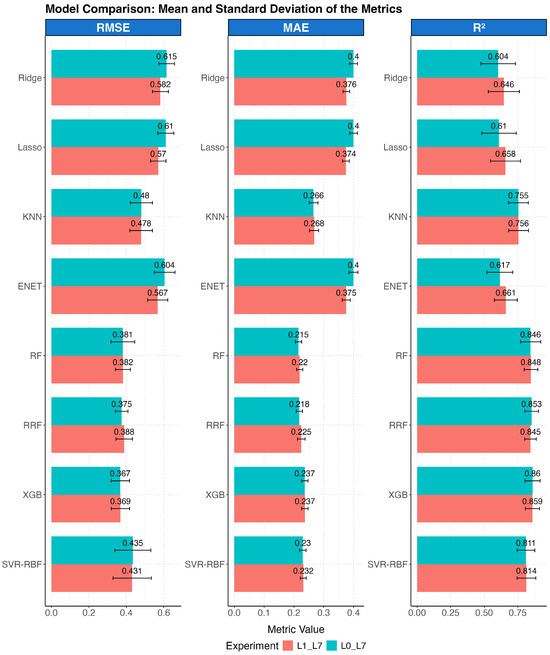

Figure 2 shows a comparison of the average performance of the different machine learning models during the cross-validation process for both experimental configurations. The error metrics for each of the resamples have been averaged, and the corresponding standard deviation is represented by error bars, allowing both the average performance and the variability associated with each model to be visualised.

Figure 2.

Average error metrics obtained by the models in the cross-validation process of both experiments. The bars represent the standard deviation.

In general, the average metrics obtained during the folds of the cross-validation process indicate that incorporating a sampling campaign lag in the physicochemical variables (L1) does not substantially improve the predictive performance of the models during training. The differences between the averages of the metrics evaluated in both configurations were mainly insignificant, with overlapping standard deviation intervals for virtually all models.

Regression tree-based models—Random Forest (RF and RRF) and eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGB)—consistently performed better across all three metrics. On average, the eXtreme Gradient Boosting model stands out as the most accurate, obtaining the lowest MAE values and the highest R2 value (0.86 in L0_L7 and 0.859 in L1_L7). The RF and RRF models also performed very well, with values very similar to those of the XGB model. For its part, the SVR-RBF model shows stable and competitive performance, especially in terms of root mean square error (RMSE). In contrast, linear models such as Ridge and Lasso regressions, as well as Elastic Net, obtained significantly lower performance across all metrics. Their explanatory power is minimal, with R2 values between 0.60 and 0.66, while their prediction errors were considerably higher than those of the nonlinear models.

3.3. Wilcoxon Test

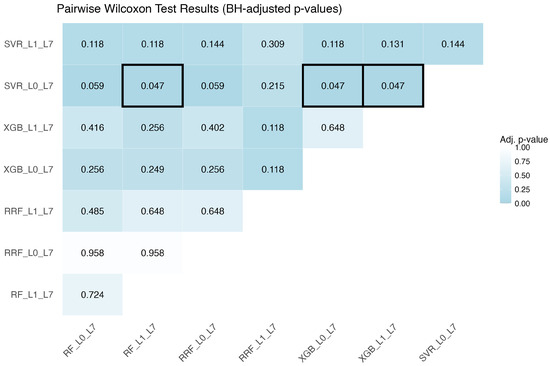

To evaluate potential significant differences between the models during the training process, a Wilcoxon paired test with the Benjamini–Hochberg adjustment was performed using the RMSE values obtained by each model in the training folds. The Random Forest (RF and RRF), eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGB), and SVR-RBF models were selected from both experiments, as they performed best during training. The resulting adjusted p-values are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Heat map showing the adjusted p-values obtained in the Wilcoxon paired test with Benjamini–Hochberg adjustment. Black borders highlight paired comparisons with significant differences (p-value < 0.05).

Analysis of the adjusted p-values using the Benjamini–Hochberg method revealed significant differences in the performance of some models. In particular, statistically significant differences (p-value < 0.05) were identified between the SVR_L0_L7 model and the RF_L1_L7, XGB_L0_L7, and XGB_L1_L7 models, suggesting that SVR_L0_L7 performs differently compared to these models, in this case worse. On the other hand, no significant differences were detected between RF and XGB model variants. There is insufficient evidence to claim that one variant of these models performs systematically better or worse than another within the compared set. This does not imply that the models are identical, but rather that their performance is statistically equivalent in the context of the data and metrics used. Therefore, any of these variants could be considered a valid option from the perspective of predictive performance.

3.4. Model Selection

After analysing the results of the models during the cross-validation process, it is not easy to select which experiment yields the best results, as the most prominent models show very similar metrics in both experiments. To choose the best experiment, Table 8 and Table 9 present the error metrics corresponding to the predictions of the models adjusted with their respective optimal hyperparameters, both in the training and test sets.

Table 8.

Results of model predictions in the L0–L7 experiment for the training and test datasets. Best metrics in each column are highlighted in bold.

Table 9.

Results of model predictions in the L1–L7 experiment for the training and test datasets. Best metrics in each column are highlighted in bold.

According to Table 8 and Table 9, eXtreme Gradient Boosting Machine (XGB) model stands out as the best performing model in the test set, especially in Experiment L1–L7, where it achieves the best RMSE (7.28), MAE (5.06), and R2 (0.29) values. RF and RRF models show high training fit; however, they have lower generalisation capacity, indicating that overfitting may have occurred.

Linear models (Ridge, Lasso, and Elastic Net) show minimal results in the test set, with negative or near-zero R2 values, reflecting their inability to capture nonlinear relationships. On the other hand, KNN and SVR-RBF models achieve good results in the training set, but their performance decreases significantly in the test set, indicating problems with generalisation.

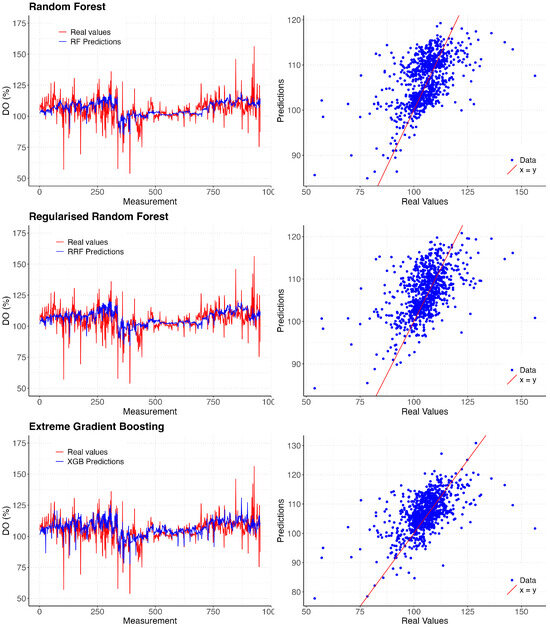

The results indicate that Experiment L1–L7 yields better results when generalising for the test set data, with improvements of nearly 10% in each of the metrics compared to Experiment L0–L7 for almost all models. Predictions of tree-based models on the Experiment L1–L7 test set are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Predictions from tree-based models of the L1–L7 experiment vs. test data (left), predicted vs. actual scatter plot (right).

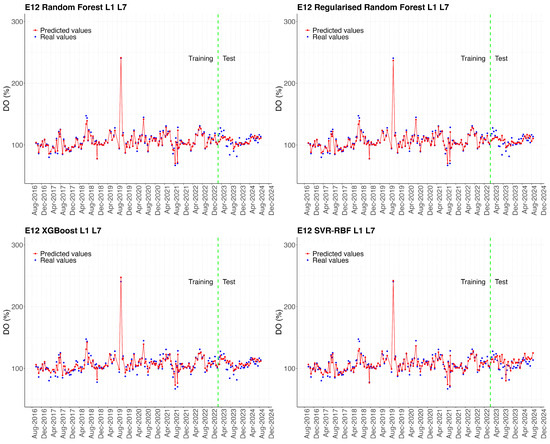

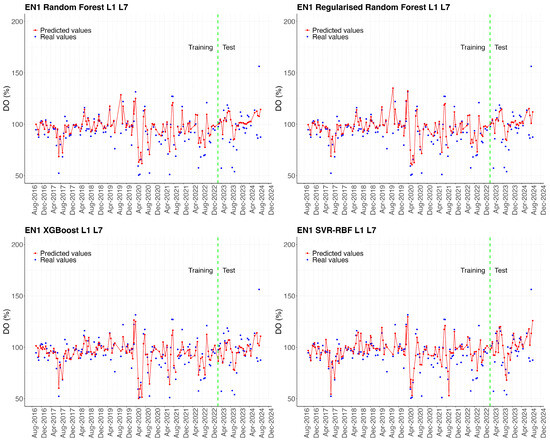

3.5. Predictions Broken Down by Sampling Points

Figure 4 shows the predictions of the Experiment L1–L7 models for the entire test set. However, it is helpful to analyse the model’s performance not only at a global level but also at small scales, depending on the different areas of the Mar Menor, to identify spatial patterns in the accuracy of the models, and evaluate the influence of local conditions on the quality of the predictions. To this end, time series were extracted from sampling points located in different areas of the Mar Menor surface, and the error metrics obtained by the models when predicting the time series for each season were calculated. The results are shown in Table 10. The time series for the stations shown in Table 10 are represented graphically in the Figure A1, Figure A2, Figure A3, Figure A4 and Figure A5 in Appendix A.

Table 10.

Error metrics for time series predictions of sampling points E01, E07, E12, E5b, and EN1. The best metrics in each station are highlighted in bold.

The results in Table 10 show apparent differences in model performance depending on the location of the sampling points. In general, the XGB model achieves the lowest errors at most sampling points, especially in the northern and central areas (E01 and E07). In contrast, higher errors are observed at point E5b, located at the mouth of the Albujón watercourse, and at point EN1, situated in front of the Encañizada. Finally, it should be noted that the SVR-RBF model tends to present higher prediction errors compared to regression tree-based models (RF, RRF, and XGB).

4. Discussion

There is currently no unified methodological framework for machine learning applications in coastal ecosystems, even within the same location. Previous studies on coastal lagoons, including the Mar Menor, are often difficult to compare because they differ substantially in objectives, data type and resolution, spatial coverage (often limited to a single sampling site for validation), temporal windows, and validation protocols. Consequently, confidence in model outcomes is highly context-dependent, and the most robust and broadly applicable modelling strategies remain unclear. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to evaluate and compare several machine learning techniques for predicting dissolved oxygen concentration in the surface layer of the Mar Menor lagoon, using environmental and meteorological variables and detecting relevant time lags in the cause–effect relationships between predictors and oxygen concentration. Two experiments were conducted considering different delays in the predictor variables.

Consideration of spatiotemporal scales, even in relatively small ecosystems, such as coastal lagoons often assumed to be homogeneous, constitutes a central motivation of this study. Monitoring systems generally face constraints in spatiotemporal resolution that depend on the variables measured and the acquisition techniques employed. A trade-off typically emerges: systems with high temporal resolution (e.g., weather stations, buoys, and continuous sensors) are spatially limited by infrastructure and maintenance costs, whereas systems with broad spatial coverage (e.g., field campaigns, drones, autonomous vehicles, and satellites) usually display lower temporal resolution owing to operational and logistical constraints.

Lag design in our analysis was primarily constrained by the sampling resolution of the available datasets and the need to maintain a parsimonious operational forecasting framework. Physicochemical variables were sampled biweekly; shorter lags could therefore not be evaluated. We used measurements from the sampling day (t) and the previous campaign (t − 1; ≈14–15 days) to represent short- and medium-term ecological memory. Meteorological variables, available at daily resolution, were lagged from t to t − 7 days to capture short-term atmospheric forcing. Longer windows (e.g., t − 14, t − 30, or multiple-campaign lags such as t − 2, t − 3) may capture slower biogeochemical responses; however, expanding the lag structure would markedly increase predictor dimensionality—already 98–123 variables prior to selection—and induce redundancy among lagged predictors, increasing overfitting risk. Accordingly, the selected lags were combined with feature selection procedures to maintain model tractability.

Model evaluation followed a strict chronological split, with the earliest 80% of observations used for training and the most recent 20% reserved for testing, emulating an operational forecasting scenario. Lagged predictors were constructed exclusively from past information and generated independently for training and test sets, while standardisation and feature selection were fitted only on the training data and then applied to the test data, thus minimising temporal leakage and supporting a realistic assessment of predictive skill. Nonetheless, because of autocorrelation and potential non-stationarity, standard k-fold cross-validation used during feature selection and hyperparameter tuning may yield optimistic estimates. Time-aware alternatives such as blocked cross-validation or rolling-origin validation with expanding or sliding windows can better preserve temporal order and provide more conservative estimates of out-of-time performance [49].

Ecological memory is crucial for generalisation and predictive power. Incorporating a time lag (L1) for physicochemical variables (approx. 14–15 days) led to significantly better performance on the test set (~10% improvement in metrics). This is a key finding that validates the importance of “ecological inertia” and delayed cause–effect relationships for building models that generalise to future conditions. Furthermore, the results show that the models exhibit very similar performance during training in both experiments. However, when generalising to new data, models incorporating physicochemical variables with a lag of one sampling campaign perform significantly better (Table 8 and Table 9). These findings indicate that the inclusion of time lags improves the representation of environmental dynamics, enhances adaptation to future conditions, and reinforces the relevance of ecological inertia and delayed responses of physicochemical variables. At the same time, evaluation on the test set reveals a pronounced discrepancy between training and test accuracy, particularly for regression tree-based models: training predictions are highly accurate, whereas test performance is more modest (Table 8 and Table 9). Although the models are trained on 80% of the data and achieve high in-sample fits (R2 > 0.9), the strong variability of the system limits explained variance to approximately 29% when applied to the withheld test data. Performance improves at the sampling station scale, reaching R2 values up to 0.53, but these values remain moderate. This likely reflects that the available spatiotemporal resolution and selected lags are not fully optimised to capture complex nonlinear relationships, synergies among ecological processes, cumulative temporal effects, stochastic meteorological forcing, and eutrophic or hypoxic episodes, potentially intensified by climate change. The Mar Menor is a highly dynamic, non-stationary system that has experienced abrupt regime shifts after the 2016 eutrophic crises [14]; consequently, patterns learned from earlier years are not fully retained in the most recent period, reducing out-of-time predictive performance, resulting in a lower test R2, despite reasonable RMSE/MAE values. Tree-based models may partially memorise noise in the training set, improving training accuracy without ensuring persistence under future conditions. Identifying and characterising the capacity of different machine learning approaches to incorporate temporal instability is therefore one of the central objectives of this study.

Reported goodness-of-fit values in other works span a wide range. For bottom dissolved oxygen (DO), coefficients of determination (R2) vary from 0.67 in Tolo Harbour to 0.82 in Mirs Bay within the same study [50], and values up to 0.978 have been reported for the Mar Menor [24]. For chlorophyll concentration in the Mar Menor, R2 values range from 0.68 for monthly predictions based on daily observations from nine sampling sites (three later discarded) [13] to 0.783–0.829 when satellite-derived signals are used depending on water-column depth [51]. In some studies, fits reach 0.99, although typically for single-station analyses [25]. Across these works, different machine learning techniques are applied, with the study periods, spatial and temporal resolutions, and even the use of interpolated instead of in situ data vary, further complicating comparison. It is important to note the high risk of overfitting in complex models. While tree-based models achieved near-perfect fits on training data (R2 > 0.98), their explained variance on the temporally withheld test set dropped sharply (R2 ~0.29). This highlights a critical challenge: powerful models can memorise noise and past states without capturing the underlying non-stationary dynamics of an ecosystem undergoing regime shifts (e.g., post-2016 eutrophication crises).

It is also necessary to underline that predictive performance is spatially heterogeneous. Model accuracy varied substantially across sampling locations. Performance was best in northern/central basin areas (e.g., E01, E07) and worst at points influenced by acute external forcing, like the Albujón watercourse mouth (E5b) and the Encañizada (EN1). This underscores that a single lagoon-wide model may mask important local dynamics driven by distinct processes.

A comprehensive review aimed at identifying patterns within this heterogeneity—encompassing methodological approaches, variables, environmental conditions, and case-study characteristics—would be highly valuable but lies beyond the scope of the present work. Instead, we emphasise explicit consideration of spatiotemporal variability, lag effects, and system inertia, and the identification of machine learning approaches that best incorporate these features. Dissolved oxygen is particularly suitable because it shows rapid responses to certain environmental and biological stressors and is highly sensitive to synergistic and antagonistic drivers. Increased solar radiation in spring and summer enhances photosynthetic production and therefore oxygen levels, whereas salinity exerts an inverse effect; in temperate lagoons, higher salinity and temperature typically occur in summer, simultaneously reducing oxygen solubility and increasing biological demand. Under such conditions, similarity or differences in environmental and climatic regimes between training and testing periods may critically influence reported performance.

For these reasons, comparing models from different methodological families is essential. Coastal lagoons such as the Mar Menor exhibit marked spatiotemporal heterogeneity, nonlinear interactions among key variables, and causal relationships operating at multiple temporal scales; predictive skill therefore varies across algorithms. Tree-based models appear to be the most suitable for complex ecological systems. Random Forest (RF) and eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGB) models consistently outperformed linear models (Ridge, Lasso, and Elastic Net) and other nonlinear models (SVR-RBF, KNN) in predicting dissolved oxygen, combining accuracy, stability, and consistency, in line with previous studies highlighting the effectiveness of regression tree-based approaches in environmental prediction and classification problems [18,50,52]. This shows that the nonlinear, synergistic relationships in the coastal lagoon are best captured by ensemble tree methods.

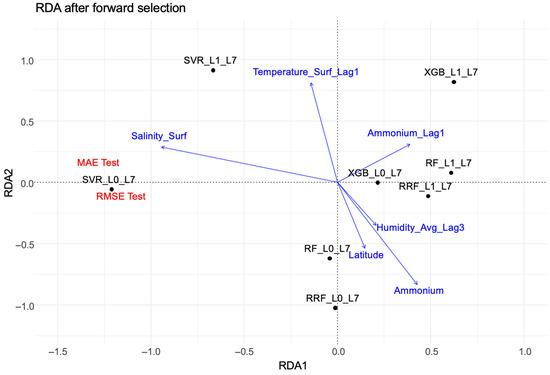

To further explore relationships between model performance and predictor variables, a redundancy analysis (RDA) was performed incorporating test-set error metrics (RMSE, MAE) and the relative importance of variables selected by each model. Forward selection with 4999 permutations was used to identify the most relevant predictors. The results (Figure 5) show error metrics located on the left side of the canonical space, indicating that models with higher error are associated with this region. In particular, the SVR_L0_L7 model exhibits a strong association with these metrics, confirming its significantly poorer performance relative to the other models.

Figure 5.

Redundancy analysis (RDA) biplot displaying the relationships between the predictive performance of the machine learning models (black dots) and the environmental variables (blue arrows). The red labels correspond to the error metrics (RMSE, MAE) considered as supplementary variables in the analysis.

Beyond the expected variables that determine oxygen concentration in the surface water layer, such as wind speed, chlorophyll concentration, dissolved organic matter, or temperature, which are selected by all models, other key predictive drivers are identified as determinants of the predictive capacity of the models. The redundancy analysis (RDA) identified ammonium concentration from the previous campaign (Ammonium_Lag1) as a variable strongly associated with the best-performing models (XGB, RF). Conversely, surface salinity (Salinity_Surf) was linked to higher prediction errors, suggesting it is a source of model uncertainty or represents complex, poorly captured interactions.

The Salinity_Surf variable (surface salinity measured on the day of the forecast) is oriented towards the left region, aligning with the direction of the error metrics. Therefore, surface salinity could contribute to increased forecast errors in specific models. In addition, the arrow for the Temperature_Surf_Lag1 variable also points partly to the left and upwards, indicating that the surface water temperature measured during the sampling campaign has a moderate relationship with these errors, although with less influence than salinity. On the other hand, the Ammonium_Lag1 variable (ammonium concentration measured in the previous sampling campaign) points to the right and is associated with models with lower errors, such as XGB_L1_L7 and RF_L1_L7, reinforcing its importance in improving predictive accuracy.

On the other hand, it is also important to underline the observed limitations in predicting extreme events. This is attributed to the rarity, heterogeneity, and differing causality of such events in the dataset, emphasising the need for long-term, high-resolution monitoring to train robust early-warning systems. The model performance under hypoxic and extreme low-dissolved oxygen conditions is critical for management applications, yet it is precisely under these circumstances that predictive skill is reduced. Beyond the general considerations discussed above, this limitation is strongly influenced by the singular characteristics of the Mar Menor. Hypoxic events were essentially absent prior to the major ecosystem disruption in 2016 [11], and during the study period only two such events occurred, each with distinct starting drivers and spatial expression. The first occurred in September 2019, was associated with water column stratification following a Isolated Depression at High Levels climatic event (DANA) with torrential rainfall and substantial runoff input, leading to hypoxia in the lower metre of the water column in deeper areas across the lagoon and surfacing locally in the north due to wind-driven upwelling. A few weeks later, this event led to local hypoxia in the deep layer of the water column associated with the accumulation of detrital organic matter [12]. The second event, occurring in August 2021, resulted from a more typical eutrophication process and was spatially restricted to the southeastern sector [12]. These crises persisted for few days. Given their differing causal mechanisms, the controlling variables also differed, and the limited number of events severely constrains model learning. These findings underscore the need for sustained, long-term monitoring with adequate spatial and temporal resolution to support the development of reliable predictive models and their future integration into digital-twin frameworks.

The results of this study should be interpreted within the context of prevailing methodological approaches in the literature, in which machine learning applications to coastal water quality have evolved into increasingly robust analytical frameworks. In remote-sensing studies, regressors such as support vector machines, random forests, and neural networks are commonly trained to translate satellite reflectance into primarily optical water-quality indicators (e.g., chlorophyll a, turbidity, and suspended solids) [51,53]. These approaches provide extensive spatial coverage but typically conceptualise the problem as an instantaneous mapping between spectral bands and water-quality variables, without explicitly accounting for ecological memory or cross-scale temporal interactions. In parallel, in situ studies in coastal lagoons have frequently emphasised optimising predictive skill through careful predictor selection and model tuning for eutrophication indicators, particularly chlorophyll a [13,54]. Time-series prediction frameworks based on recurrent neural networks address temporal dependence more directly through sliding windows and time-blocked validation, yet they are commonly trained at single stations and thus prioritise local temporal dynamics over spatial transferability [24,25]. Within this methodological landscape, the present study seeks to explicitly incorporate ecological memory by combining daily meteorological information with lagged in situ variables, and to assess model generalisation using strict temporal partitioning together with evaluation at the sampling-point level. Although our work already defines some of the relevant scales in the case of a variable such as oxygen concentration, it would be important to further investigate the role played by delays in responses and the spatial and temporal variability scales of different variables at higher resolution, as well as to develop new modelling techniques that allow for a multiscale approach of predictive models.

5. Conclusions

Prediction of surface dissolved oxygen in the Mar Menor markedly improves when time-lagged physicochemical variables are incorporated, confirming the lagoon’s strong ecological inertia and the need to represent system memory. Models based on decision trees provided the best balance of accuracy and robustness, with eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGB) trained on a dataset that includes lagged physicochemical variables outperforming other approaches, while linear methods and KNN underperformed and SVR-RBF showed overfitting.

Incorporating temporal lags is key. The explicit inclusion of ecological memory (via time-lagged variables) is not just beneficial but essential for developing predictive models that remain valid for future, unseen conditions. This should be a standard consideration in similar ecological forecasting studies.

There is a trade-off between fit and forecast. The study demonstrates a clear dichotomy between excellent in-sample fit and modest out-of-sample predictive power for complex environmental systems. This cautions against over-reliance on training metrics and underscores the necessity of strict, temporally split validation to assess true operational forecasting skill.

One important conclusion that affects the increasing trend to build digital twins of more or less extended coastal systems is that spatial context matters. Conclusions about model performance must be qualified by location. A model’s utility for management decisions will depend on the specific area of interest within the lagoon, as performance is not uniform. Spatial differences in performance reflected local hydrodynamics and external inputs influence, indicating that site-specific calibration is necessary in addition to global modelling. RDA linked higher errors to contemporaneous surface salinity and prior surface temperature, whereas recent ammonium concentrations were associated with greater predictive accuracy as examples of variables that have very different inertia in their effects on oxygen concentration, the former are related to its solubility and the latter, probably to consumer demand. Overall, time-lagged predictors combined with tree-based models offer an effective and transferable framework for dissolved oxygen modelling in Mediterranean lagoon systems. However, future advances will require higher efforts in spatiotemporal monitoring resolution and machine learning approaches capable of integrating multi-scale variability to improve predictive capacity in extreme or localised scenarios. Summarising, the pathway for improvement would include (a) improving spatiotemporal data resolution to capture key processes, (b) developing modelling techniques (e.g., time-aware validation, multiscale approaches) that better handle non-stationarity, and c) prioritising the prediction of extreme, low-probability events through enhanced data collection and targeted model design.

Author Contributions

J.M.L.-G.: Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Model Development, Validation, Visualisation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing; J.P.: Conceptualisation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing—Review and Editing; F.J.: Conceptualisation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Validation; C.M.: Project Management and Administration, Review, Editing, and Validation; A.P.-R.: Conceptualisation, Formal Analysis, Funding Acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project Administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualisation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been made possible thanks to funding from various projects and agreements with the Autonomous Community of the Region of Murcia for the “Monitoring and modelling of water quality and the ecological status of the Mar Menor and impact prevention” (proyecto “44246”, subproyecto 044246240001).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Angel Pérez-Ruzafa (angelpr@um.es).

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declared that the submitted work was carried out without any personal, professional, or financial relationships that could potentially be construed as a conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbours |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RRF | Regularised Random Forest |

| XGB | Extreme Gradient Boosting |

| SVR-RBF | Support Vector Regression Radial Basis Function |

| RDA | Redundancy Analysis |

Appendix A

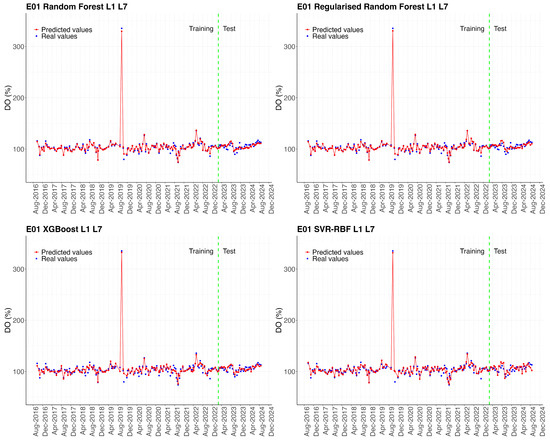

Figure A1.

Comparison between actual values (blue dots) and predictions (red line) of dissolved oxygen (DO %) concentration for sampling point E01. The green dotted line marks the start of the test set, differentiating the training period (left) from the testing period (right).

Figure A2.

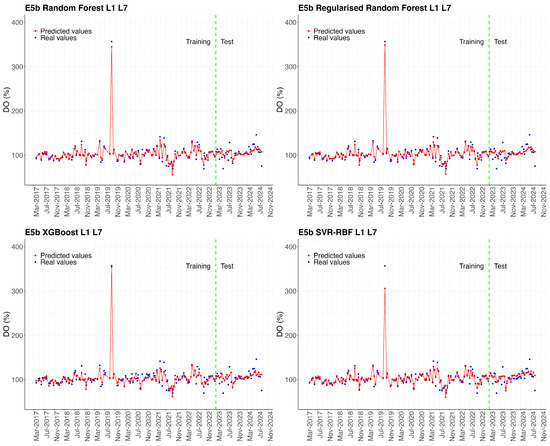

Comparison between actual values (blue dots) and predictions (red line) of dissolved oxygen (DO %) concentration for sampling point E5b. The green dotted line marks the start of the test set, differentiating the training period (left) from the testing period (right).

Figure A3.

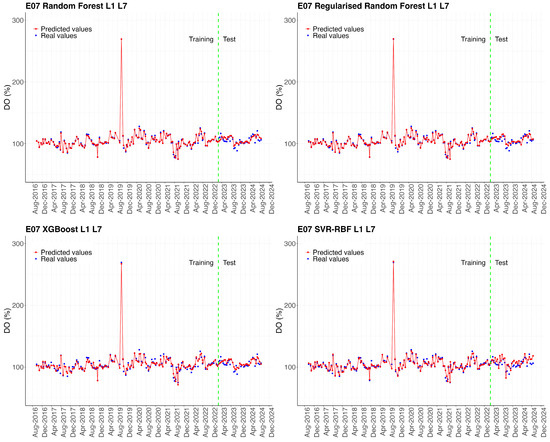

Comparison between actual values (blue dots) and predictions (red line) of dissolved oxygen (DO %) concentration for sampling point E07. The green dotted line marks the start of the test set, differentiating the training period (left) from the testing period (right).

Figure A4.

Comparison between actual values (blue dots) and predictions (red line) of dissolved oxygen (DO %) concentration for sampling point E12. The green dotted line marks the start of the test set, differentiating the training period (left) from the testing period (right).

Figure A5.

Comparison between actual values (blue dots) and predictions (red line) of dissolved oxygen (DO %) concentration for sampling point EN1. The green dotted line marks the start of the test set, differentiating the training period (left) from the testing period (right).

References

- Lantz, B. Machine Learning with R; Community experience distilled; Packt Publishing: Birmingham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, N. Application of Machine learning techniques in environmental governance: A review. Adv. Eng. Technol. Res. 2023, 7, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olawade, D.B.; Wada, O.Z.; Ige, A.O.; Egbewole, B.I.; Olojo, A.; Oladapo, B.I. Artificial intelligence in environmental monitoring: Advancements, challenges, and future directions. Hyg. Environ. Health Adv. 2024, 12, 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishat, M.M.; Khan, M.R.; Ahmed, T.; Hossain, S.; Ahsan, A.; El-Sergany, M.; Shafiquzzaman, M.; Imteaz, M.; Alresheedi, M. Comparative analysis of machine learning models for predicting water quality index in Dhaka’s rivers of Bangladesh. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2025, 37, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özüpak, Y.; Alpsalaz, F.; Aslan, E. Air quality forecasting using machine learning: Comparative analysis and ensemble strategies for enhanced prediction. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2025, 236, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, A.; Icely, J.; Cristina, S.; Brito, A.; Cardoso, A.; Colijn, F.; Riva, S.; Gertz, F.; Hansen, J.; Holmer, M.; et al. An overview of ecological status, vulnerability and future perspectives of European large shallow, semi-enclosed coastal systems, lagoons and transitional waters. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2013, 140, 95–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ruzafa, A.; Pérez-Ruzafa, I.M.; Newton, A.; Marcos, C. Coastal lagoons: Environmental variability, ecosystem complexity and goods and services uniformity. In Coastal and Estuaries, the Future; Wolanski, E., Day, J., Elliot, M., Ramesh, R., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 253–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Alías, A.; Marcos, C.; Quispe, J.I.; Sabah, S.; Pérez-Ruzafa, A. Population dynamics and growth in three scyphozoan jellyfishes, and their relationship with environmental conditions in a coastal lagoon. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2020, 243, 106901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ruzafa, A.; Marcos, C.; Pérez-Ruzafa, I.; Barcala, E.; Hegazi, M.; Quispe, J. Detecting changes resulting from human pressure in a naturally quick changing and heterogeneous environment: Spatial and temporal scales of variability in coastal lagoons. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2007, 75, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloern, J.; Abreu, P.; Carstensen, J.; Chauvaud, L.; Elmgren, R.; Grall, J.; Greening, H.; Johansson, J.R.; Kahru, M.; Sherwood, E.; et al. Human activities and climate variability drive fast-paced change across the world’s estuarine-coastal ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 22, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ruzafa, A.; Campillo, S.; Fernández-Palacios, J.M.; García-Lacunza, A.; García- Oliva, M.; Ibañez, H.; Navarro-Martínez, P.C.; Pérez-Marcos, M.; Pérez-Ruzafa, I.M.; Quispe-Becerra, J.I.; et al. Long-term dynamic in nutrients, chlorophyll a, and water quality parameters in a coastal lagoon during a process of eutrophication for decades, a sudden break and a relatively rapid recovery. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Alías, A.; Montaño-Barroso, T.; Conde-Caño, M.R.; Manchado-Pérez, S.; López-Galindo, C.; Quispe-Becerra, J.I.; Marcos, C.; Pérez-Ruzafa, A. Nutrient overload promotes the transition from top-down to bottom-up control and triggers dystrophic crises in a mediterranean coastal lagoon. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 846, 157388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimeno-Sáez, P.; Senent-Aparicio, J.; Cecilia, J.; Pérez-Sánchez, J. Using machine-learning algorithms for eutrophication modeling: Case study of Mar Menor lagoon (Spain). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giménez, J.G.; Granero, A.; Senent-Aparicio, J.; Gómez-Jakobsen, F.; Mercado, J.M.; Blanco-Gómez, P.; Ruiz, J.M.; Cecilia, J.M. Assessment of oceanographic services for the monitoring of highly anthropised coastal lagoons: The Mar Menor case study. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 81, 102554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ruzafa, A. Seguimiento y Análisis Predictivo del Estado Ecológico del Ecosistema Lagunar del Mar Menor y Prevención de Impactos. Consejería de Medio Ambiente, Universidades, Investigación y Mar Menor, Región de Murcia, España. 2024. Available online: https://canalmarmenor.carm.es/wp-content/uploads/Informe_final_abril-2023_junio-2024-Seguimiento-Mar-Menor-Angel-Perez-Ruzafa.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2026).

- Béjaoui, B.; Ottaviani, E.; Barelli, E.; Ziadi, B.; Dhib, A.; Lavoie, M.; Gianluca, C.; Turki, S.; Solidoro, C.; Aleya, L. Machine learning predictions of trophic status indicators and plankton dynamic in coastal lagoons. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 95, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concepcion, R.; Dadios, E.; Bandala, A.; Caçador, I.; Fonseca, V.F.; Duarte, B. Applying limnological feature-based Machine Learning Techniques to chemical state classification in Marine Transitional Systems. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 658434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonetti, I.; Lubello, C.; Cappietti, L. On the use of hydrodynamic modelling and random forest classifiers for the prediction of hypoxia in coastal lagoons. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zennaro, F.; Furlan, E.; Canu, D.; Alcazar, L.A.; Rosati, G.; Solidoro, C.; Critto, A. Hypoxia extreme events in a changing climate: Machine learning methods and deterministic simulations for future scenarios development in the Venice lagoon. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 208, 117028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauricio, D.C.; Lugon, J.; Merlo, A.; Omai, M.; Gonzalez, P.H.; Guerra, R.; Telles, W.; Brandao, D. Application of Machine-Learning techniques for Water Quality Assessment in Coastal Environments: A case study of the Jacarepaguá Lagoon system at Rio de Janeiro/BR. In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2025; PT III; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 15650, pp. 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, D.; Salvador, P.; Sanz, J.; Casanova, J.L. A new approach to monitor water quality in the Menor sea (Spain) using satellite data and machine learning methods. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 286, 117489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-López, E.; Navarro, G.; Santos-Echeandía, J.; Bernárdez, P.; Caballero, I. Machine Learning for Detection of Macroalgal Blooms in the Mar Menor Coastal Lagoon Using Sentinel-2. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisterna-García, A.; González-Vidal, A.; Martínez-Ibarra, A.; Ye, Y.; Guillén-Teruel, A.; Bernal-Escobedo, L.; Skarmeta, A.F. Artificial intelligence for streamflow prediction in river basins: A use case in Mar Menor. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Andreu, F.J.; López-Morales, J.A.; Hernández-Guillén, Z.; Carrero-Rodrigo, J.A.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, M.; Atenza-Juárez, J.F.; Erena, M. Deep Learning-Based Time Series Forecasting Models Evaluation for the Forecast of Chlorophyll a and Dissolved Oxygen in the Mar Menor. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Enrique, J.; Rodríguez-García, M.I.; Ruiz-Aguilar, J.J.; Carrasco-García, M.G.; Enguix, I.F.; Turias, I.J. Chlorophyll-α forecasting using LSTM, bidirectional LSTM and GRU networks in El Mar Menor (Spain). Log. J. IGPL 2015, 33, jzae046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delnevo, G.; Tumedei, G.; Ghini, V.; Prandi, C. Toward a Digital Twin: Combining sensing, machine learning, and data visualization for the effective management of a coastal lagoon environment. In Proceedings of the IEEE 21st Consumer Communications & Networking Conference (CCNC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 6–9 January 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; González-Vidal, A.; Cisterna-García, A.; Pérez-Ruzafa, A.; Zamora Izquierdo, M.A.; Skarmeta, A.F. Advancing towards a marine digital twin platform: Modeling the Mar Menor coastal lagoon ecosystem in the south western Mediterranean. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2026, 178, 108265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Ruzafa, A.; Marcos, C.; Ros, J. Environmental and biological changes related to recent human activities in the Mar Menor (SE of Spain). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1991, 23, 747–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Ruzafa, A.; Fernández, A.I.; Marcos, C.; Gilabert, J.; Quispe, J.I.; García-Charton, J.A. Spatial and temporal variations of hydrological conditions, nutrients and chlorophyll a in a mediterranean coastal lagoon (Mar Menor, Spain). Hydrobiologia 2005, 550, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Oliva, M.; Pérez-Ruzafa, A.; Umgiesser, G.; McKiver, W.; Ghezzo, M.; De Pascalis, F.; Marcos, C. Assessing the Hydrodynamic Response of the Mar Menor Lagoon to Dredging Inlets Interventions through Numerical Modelling. Water 2018, 10, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoerl, A.E.; Kennard, R.W. Ridge regression: Biased estimation for nonorthogonal problems. Technometrics 1970, 12, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibshirani, R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1996, 58, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Hastie, T. Regularization and Variable Selection Via the Elastic Net. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 2005, 67, 301–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cover, T.M.; Hart, P.E. Nearest neighbor pattern classification. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1967, 13, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Runger, G.C. Feature selection via regularized trees. In The 2012 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN); IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In KDD’16: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, H.; Burges, C.J.C.; Kaufman, L.; Smola, A.; Vapnik, V. Support vector regression machines. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 1997, 28, 779–784. [Google Scholar]

- Guyon, I.; Weston, J.; Barnhill, S.; Vapnik, V. Gene selection for cancer classification using support vector machines. Mach. Learn. 2002, 46, 389–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodson, T.O. Root-mean-square error (RMSE) or mean absolute error (MAE): When to use them or not. Geosci. Model Dev. 2022, 15, 5481–5487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcoxon, F. Individual comparisons by ranking methods. Biom. Bull. 1945, 1, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H.; Bryan, J. readxl: Read Excel Files, R package version 1.4.3; The Comprehensive R Archive Network: Boston, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H.; François, R.; Henry, L.; Müller, K.; Vaughan, D. dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation, R package version 1.1.4; The Comprehensive R Archive Network: Boston, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kowarik, A.; Templ, M. Imputation with the R package VIM. J. Stat. Softw. 2016, 74, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M. caret: Classification and Regression Training, R package version 6.0-93; The Comprehensive R Archive Network: Boston, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, W.; Cheng, J.; Allaire, J.; Sievert, C.; Schloerke, B.; Xie, Y.; Allen, J.; McPherson, J.; Dipert, A.; Borges, B. Shiny: Web Application Framework for R, R package version 1.7.4.1; The Comprehensive R Archive Network: Boston, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmeir, C.; Benítez, J.M. On the use of cross-validation for time series predictor evaluation. Inf. Sci. 2012, 191, 192–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]