Bridging Time-Scale Mismatch in WWTPs: Long-Term Influent Forecasting via Decomposition and Heterogeneous Temporal Attention

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Does the adopted HD-MAED-LSTM model contribute to enhancing the medium-to-long-term prediction of influent water quality in WWTPs?

- (2)

- Based on the validity of (1), do the decomposition-prediction strategy and specialized attention mechanisms in the model work effectively? How much does each module contribute to the overall model performance?

- (3)

- A systematic analysis of key parameter sensitivity to determine the optimal model configuration.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Data Collection

2.2. Data Preprocessing

2.3. Base Models

2.3.1. Seasonal-Trend Decomposition Using Loess

2.3.2. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)

2.3.3. Encoder-Decoder Architecture

2.3.4. Attention Mechanism

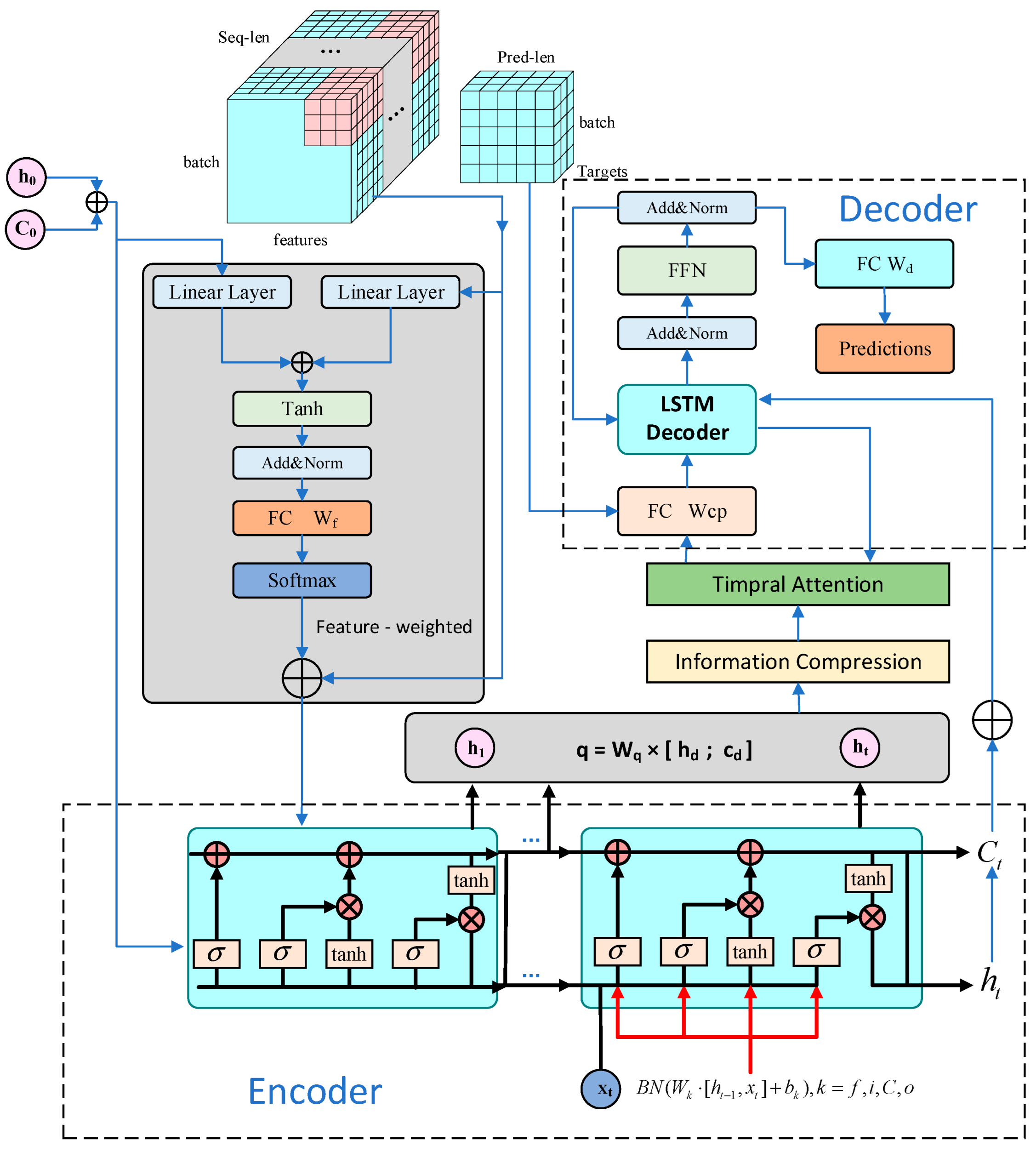

2.4. HD-MAED-LSTM

2.4.1. Feature Attention

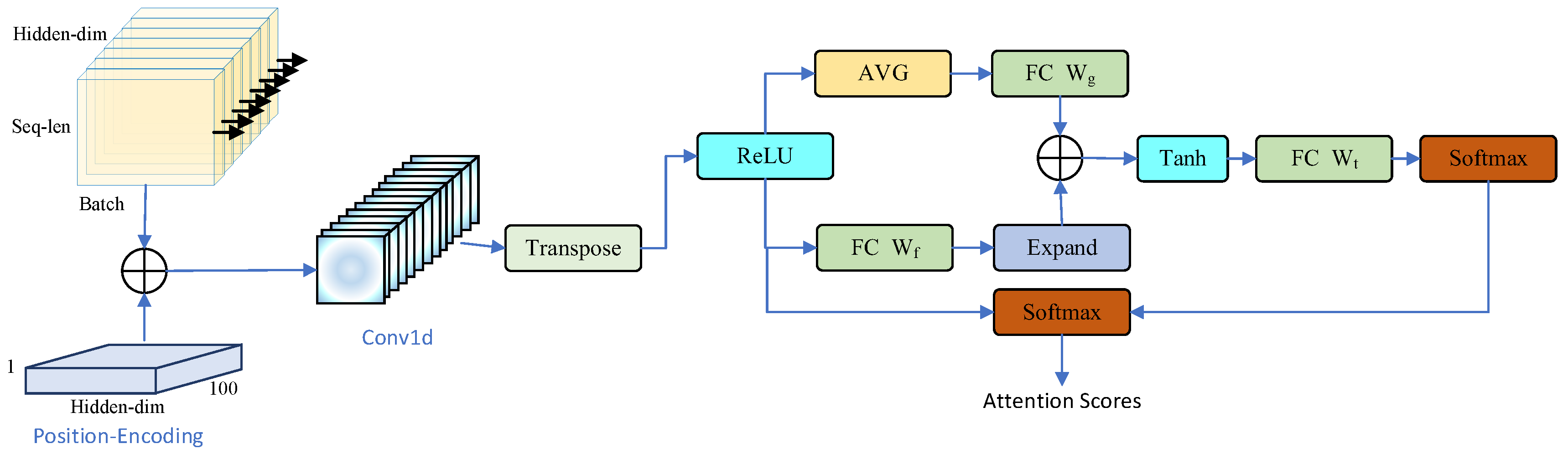

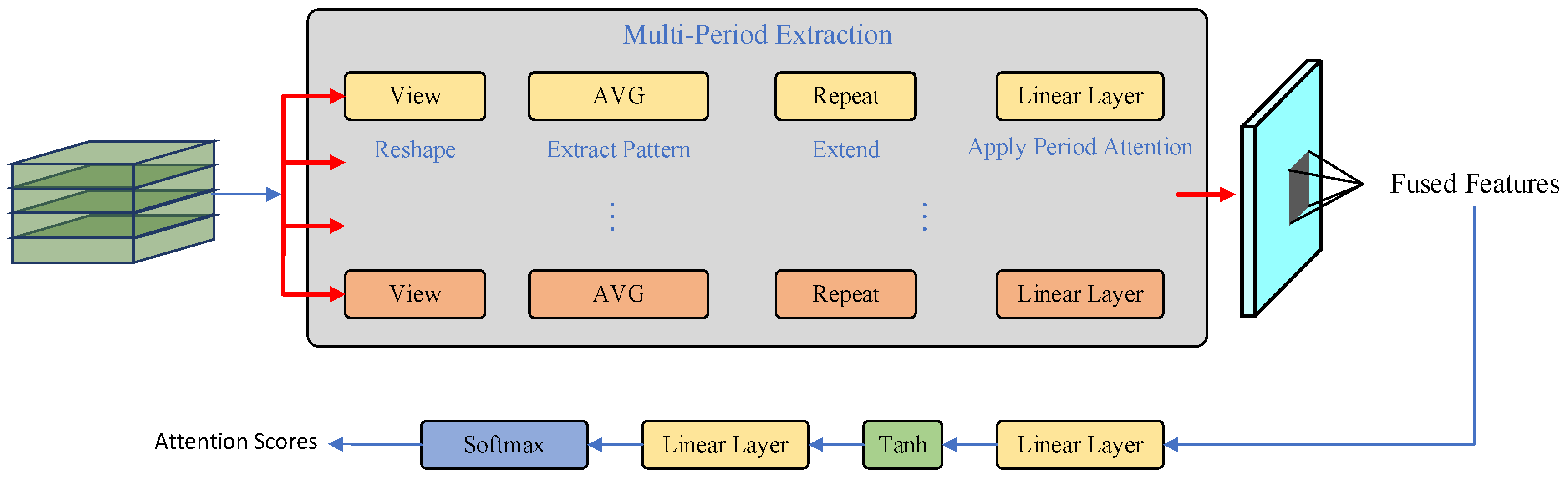

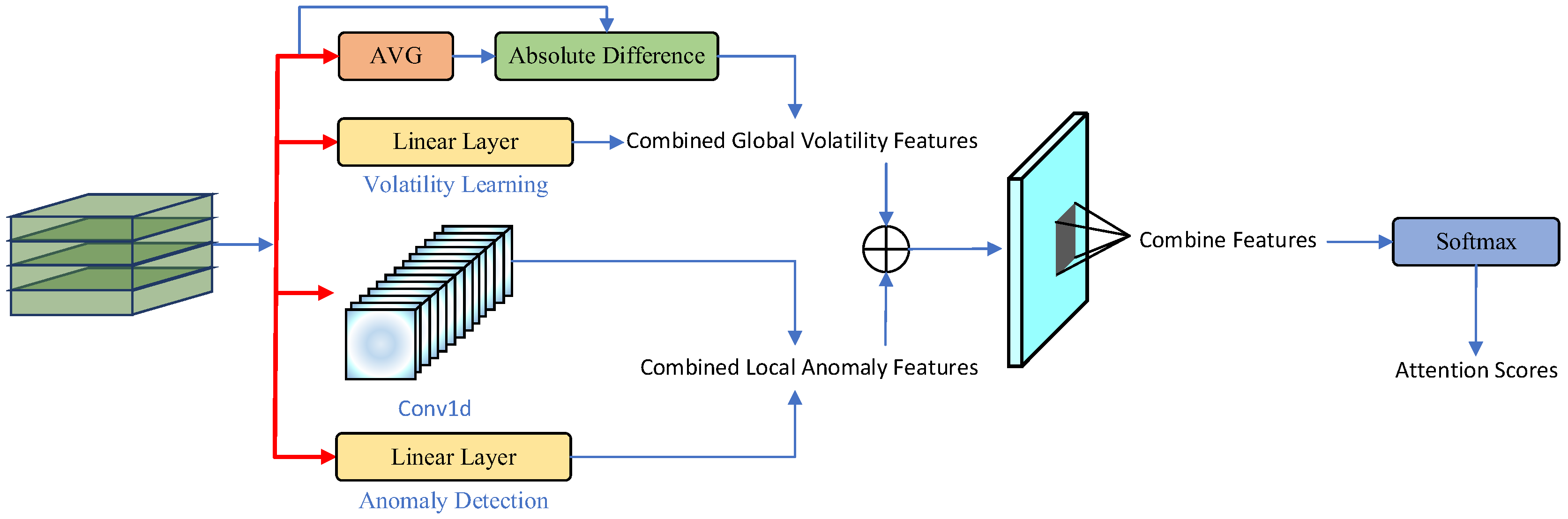

2.4.2. Encoder and Heterogeneous Temporal Attention Mechanism

2.4.3. Decoder and Prediction Reconstruction

2.5. Model Training

2.6. Performance Evaluation

3. Results and Discussion

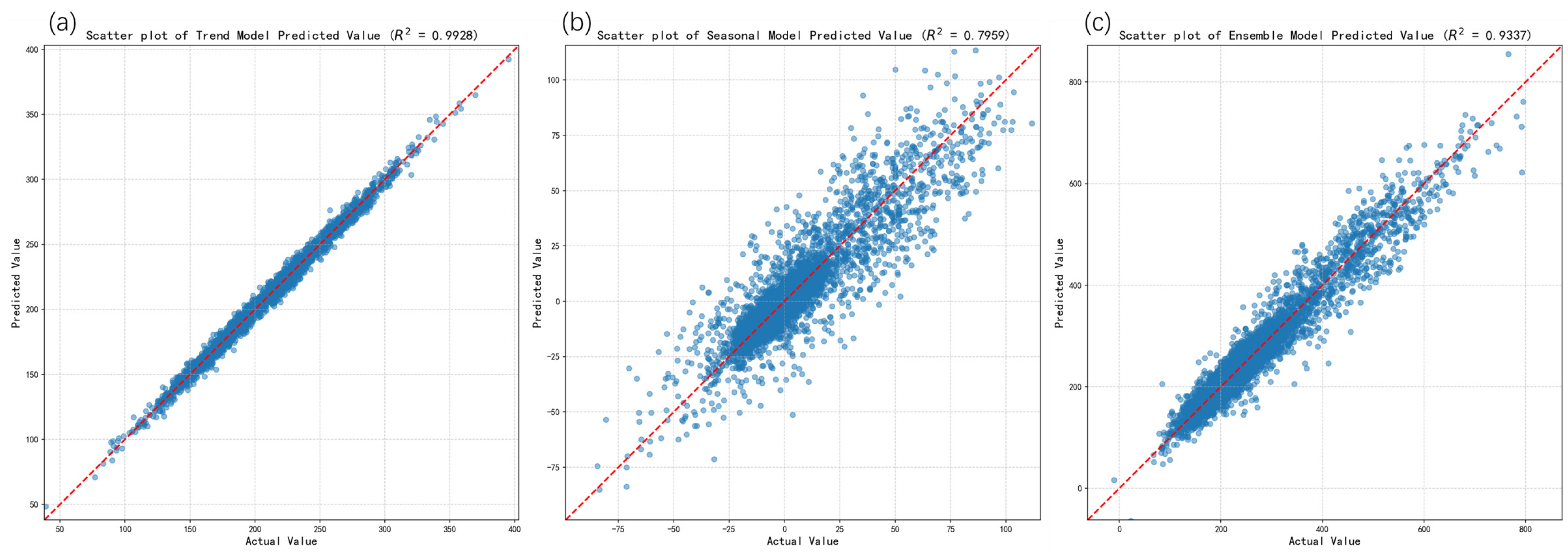

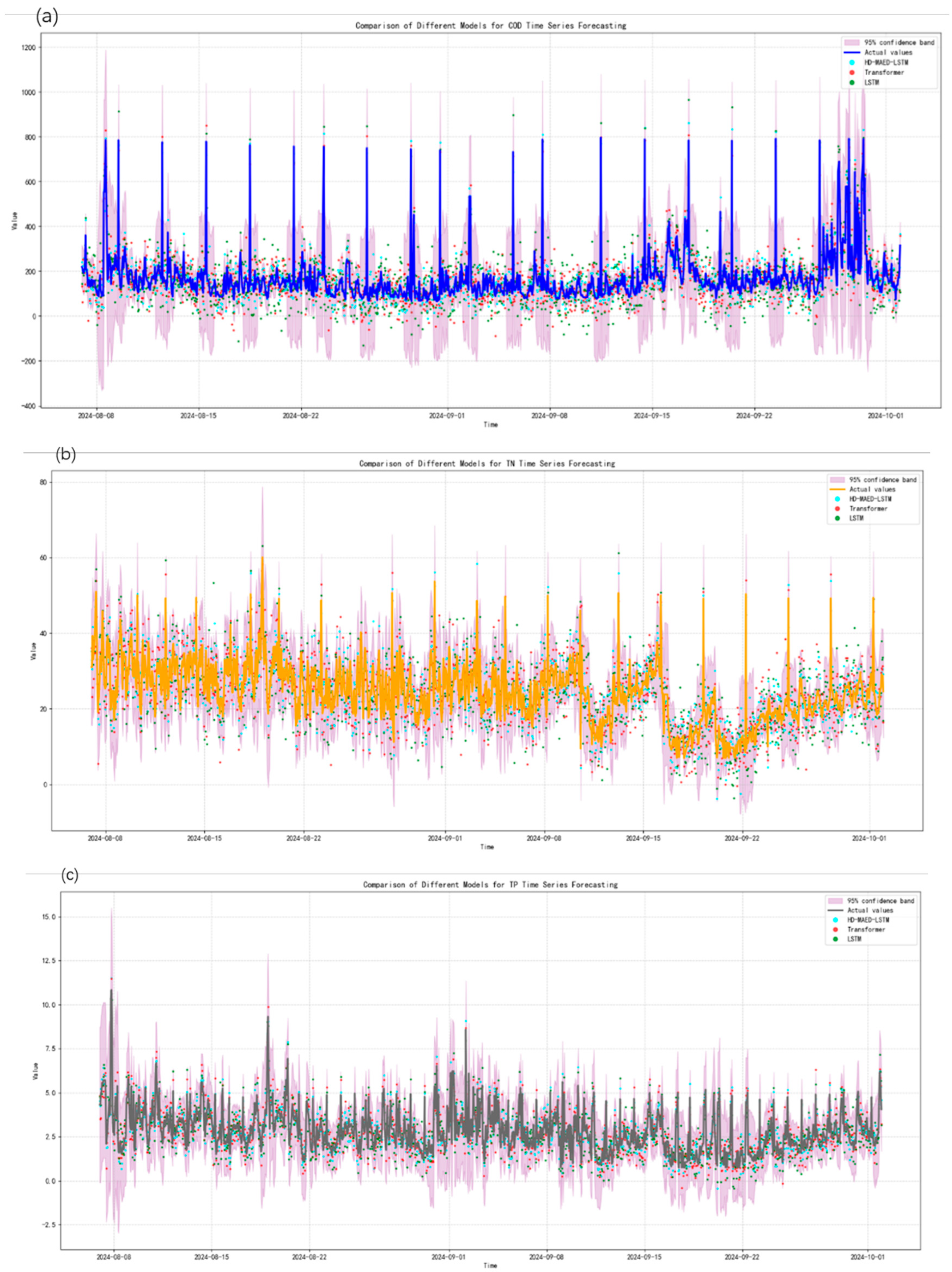

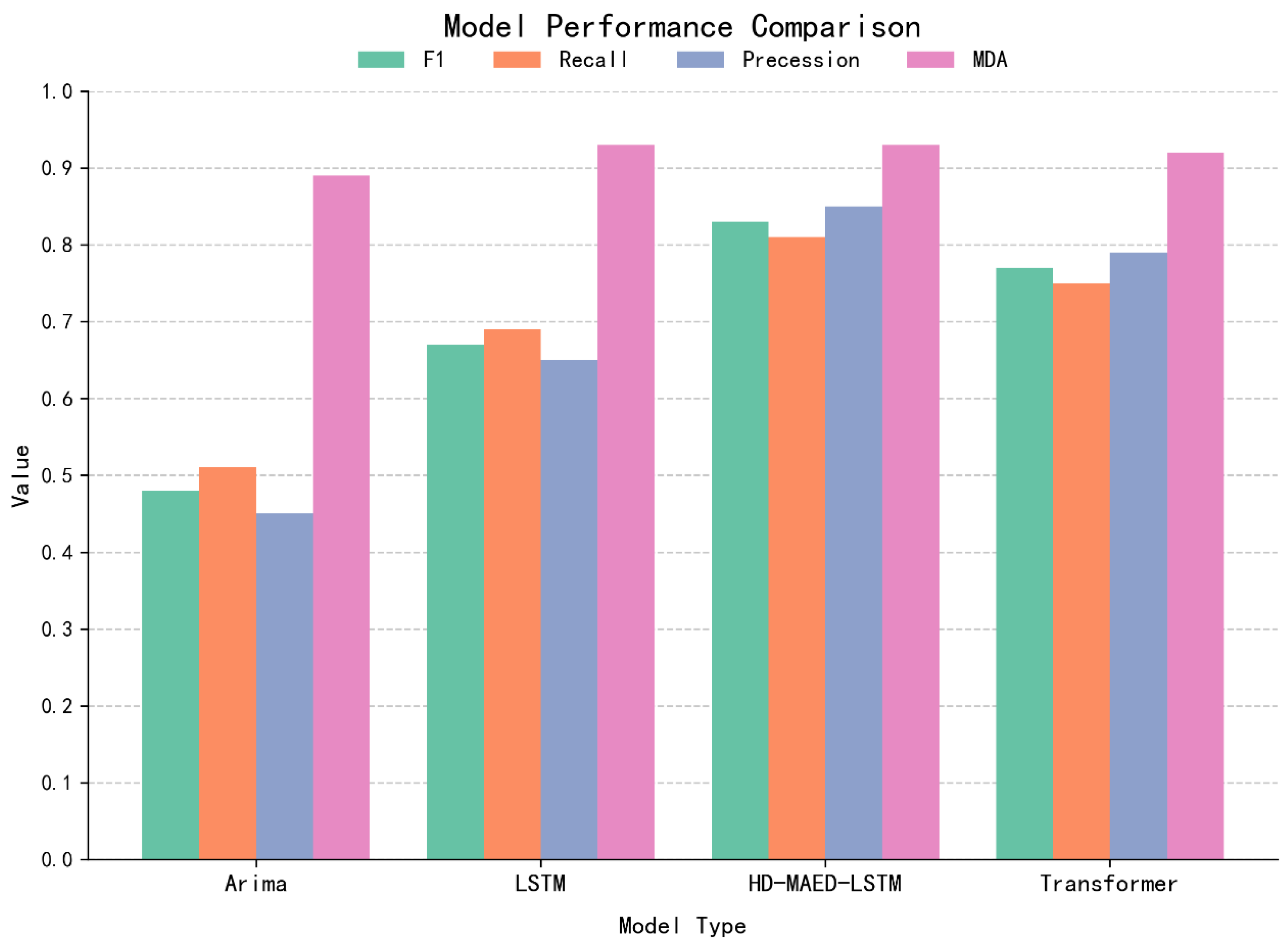

3.1. Performance Analysis

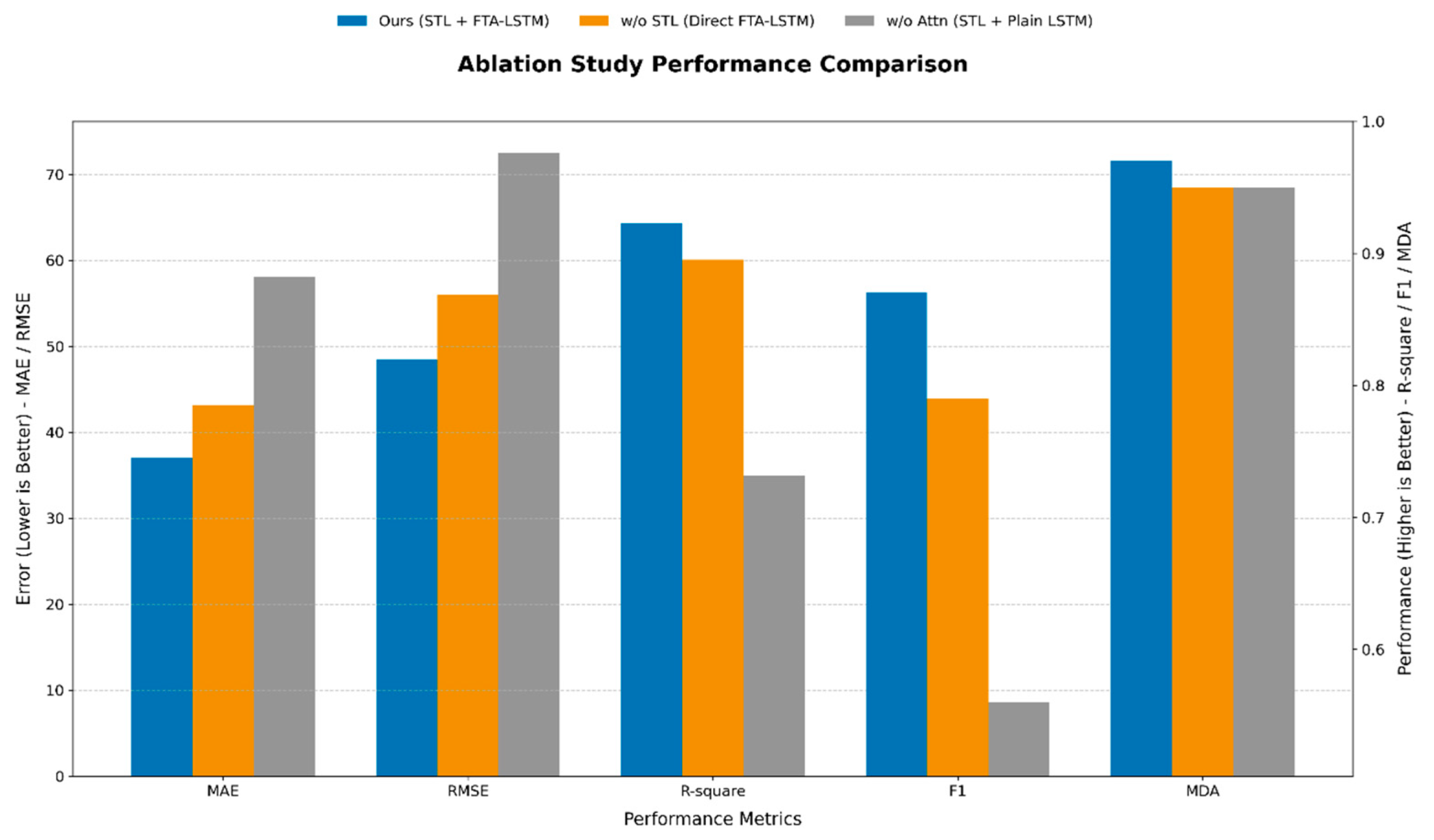

3.2. Contribution Analysis (Ablation Experiment)

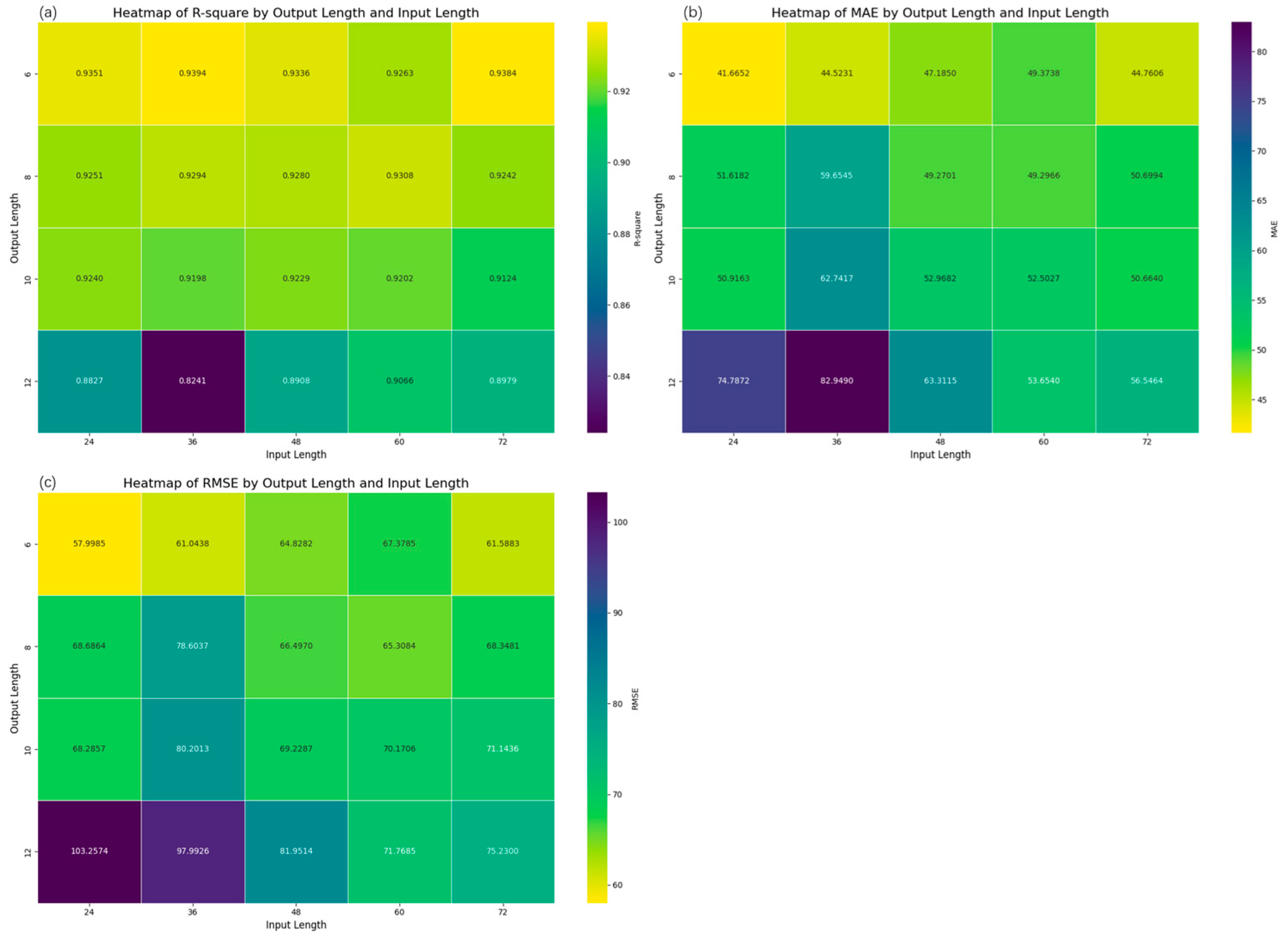

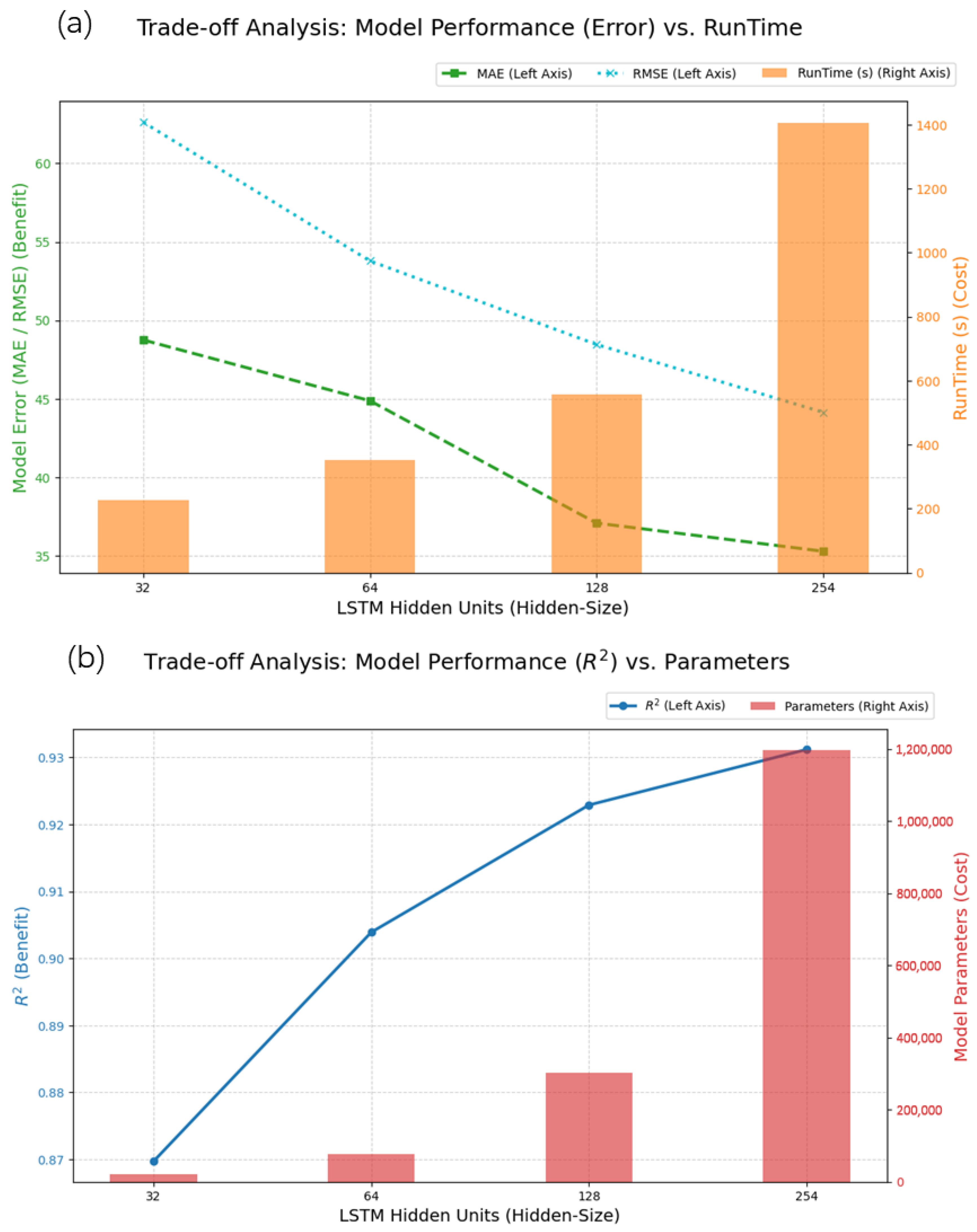

3.3. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

3.4. Discussion on Generalizability to Different WWTP Scenarios

4. Conclusions and Future Work

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xie, Y.; Wang, D.; Qiao, J. Dynamic Multi-Objective Intelligent Optimal Control toward Wastewater Treatment Processes. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2022, 65, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Pan, Z.; Chen, Y.; Tan, Z.; Zhang, J. Influent Quality and Quantity Predictionin Wastewater Treatment Plant: Model Construction and Evaluation. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2021, 30, 4267–4276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, M.; Muttaqi, K.M.; Sutanto, D.; Al-Shetwi, A.Q.; Ker, P.J.; Hannan, M.A. Control Technologies of Wastewater Treatment Plants: The State-of-the-Art, Current Challenges, and Future Directions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 181, 113324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamaludin, M.; Tsai, Y.-C.; Lin, H.-T.; Huang, C.-Y.; Choi, W.; Chen, J.-G.; Sean, W.-Y. Modeling and Control Strategies for Energy Management in a Wastewater Center: A Review on Aeration. Energies 2024, 17, 3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arismendy, L.; Cárdenas, C.; Gómez, D.; Maturana, A.; Mejía, R.; Quintero M., C.G. Intelligent System for the Predictive Analysis of an Industrial Wastewater Treatment Process. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhi, N.; Kohen, E.; Mamane, H.; Shavitt, Y. Prediction of Wastewater Treatment Quality Using LSTM Neural Network. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 23, 101632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, L.; Zhao, R.; Yan, K.; Wang, W. Accurate Prediction of Water Quality in Urban Drainage Network with Integrated EMD-LSTM Model. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 354, 131724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, J.; Quan, P.; Wang, J.; Meng, X.; Li, Q. Prediction of Influent Wastewater Quality Based on Wavelet Transform and Residual LSTM. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 148, 110858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yang, K.; Peng, H. Using a Seasonal and Trend Decomposition Algorithm to Improve Machine Learning Prediction of Inflow from the Yellow River, China, into the Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1540912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Li, C.; Hao, H.; Liang, S.; Shen, Q.; Li, D. VBTCKN: A Time Series Forecasting Model Based on Variational Mode Decomposition with Two-Channel Cross-Attention Network. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chang, X.; Li, M.; Roy-Chowdhury, A.; Chen, J.; Oymak, S. Selective Attention: Enhancing Transformer through Principled Context Control. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.12892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wei, Q.; Yin, H. A Hybrid Deep Learning Approach to Improve Real-Time Effluent Quality Prediction in Wastewater Treatment Plant. Water Res. 2024, 250, 121092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddique, M.F.; Saleem, F.; Umar, M.; Kim, C.H.; Kim, J.-M. A Hybrid Deep Learning Approach for Bearing Fault Diagnosis Using Continuous Wavelet Transform and Attention-Enhanced Spatiotemporal Feature Extraction. Sensors 2025, 25, 2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zare Abyaneh, H. Evaluation of Multivariate Linear Regression and Artificial Neural Networks in Prediction of Water Quality Parameters. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2014, 12, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manu, D.S.; Thalla, A.K. Artificial Intelligence Models for Predicting the Performance of Biological Wastewater Treatment Plant in the Removal of Kjeldahl Nitrogen from Wastewater. Appl. Water Sci. 2017, 7, 3783–3791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Sun, M.; Han, H.; Wu, X.; Qiao, J. Univariate Imputation Method for Recovering Missing Data in Wastewater Treatment Process. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 53, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, C.; Duan, H.; Wang, W. Attention-Based Deep Learning Models for Predicting Anomalous Shock of Wastewater Treatment Plants. Water Res. 2025, 275, 123192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagherzadeh, F.; Mehrani, M.-J.; Basirifard, M.; Roostaei, J. Comparative Study on Total Nitrogen Prediction in Wastewater Treatment Plant and Effect of Various Feature Selection Methods on Machine Learning Algorithms Performance. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 41, 102033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzegar, R.; Aalami, M.T.; Adamowski, J. Short-Term Water Quality Variable Prediction Using a Hybrid CNN–LSTM Deep Learning Model. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2020, 34, 415–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, R.B.; Cleveland, W.S.; Terpenning, I. STL: A Seasonal-Trend Decomposition Procedure Based on Loess. J. Off. Stat. 1990, 6, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; Van Merrienboer, B.; Bahdanau, D.; Bengio, Y. On the Properties of Neural Machine Translation: Encoder–Decoder Approaches. In Proceedings of the SSST-8, Eighth Workshop on Syntax, Semantics and Structure in Statistical Translation, Doha, Qatar, 25 October 2014; Association for Computational Linguistics: Doha, Qatar, 2014; pp. 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Sutskever, I.; Vinyals, O.; Le, Q.V. Sequence to Sequence Learning with Neural Networks. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahdanau, D.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1409.0473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. arXiv 2023, arXiv:1706.03762. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hao, J.; Liu, F. Improving Long-Term Multivariate Time Series Forecasting with a Seasonal-Trend Decomposition-Based 2-Dimensional Temporal Convolution Dense Network. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Gong, C.; Yang, L.; Chen, Y. DSTP-RNN: A Dual-Stage Two-Phase Attention-Based Recurrent Neural Network for Long-Term and Multivariate Time Series Prediction. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 143, 113082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.01703. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.P. Time Series Forecasting Using a Hybrid ARIMA and Neural Network Model. Neurocomputing 2003, 50, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodson, T.O. Root-Mean-Square Error (RMSE) or Mean Absolute Error (MAE): When to Use Them or Not. Geosci. Model Dev. 2022, 15, 5481–5487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, U.; Mumtaz, R.; Anwar, H.; Shah, A.A.; Irfan, R.; García-Nieto, J. Efficient Water Quality Prediction Using Supervised Machine Learning. Water 2019, 11, 2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Pianosi, F.; Wagener, T. Technical Report—Methods: A Diagnostic Approach to Analyze the Direction of Change in Model Outputs Based on Global Variations in the Model Inputs. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2020WR027153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Yu, J.; Kang, C.; Ryang, G.; Wei, Y.; Wang, X. A Novel Hybrid Water Quality Forecast Model Based on Real-Time Data Decomposition and Error Correction. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 162, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Huang, J.; Wang, P.; Tang, X.; Zhang, Z. A Coupled Model to Improve River Water Quality Prediction towards Addressing Non-Stationarity and Data Limitation. Water Res. 2024, 248, 120895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Mi, X.; Li, Y. Smart Deep Learning Based Wind Speed Prediction Model Using Wavelet Packet Decomposition, Convolutional Neural Network and Convolutional Long Short Term Memory Network. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 166, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, S.; Parekh, F. Flood Forecasting Using Artificial Neural Network. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1086, 012036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, A.; Nahavandi, S.; Creighton, D.; Atiya, A.F. Lower Upper Bound Estimation Method for Construction of Neural Network-Based Prediction Intervals. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2011, 22, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunova, D.; Bakratsi, V.; Vrochidou, E.; Papakostas, G.A. Machine Learning for Anomaly Detection in Industrial Environments. Eng. Proc. 2024, 70, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Kim, H. A New Metric of Absolute Percentage Error for Intermittent Demand Forecasts. Int. J. Forecast. 2016, 32, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Yang, G. A Hybrid NOx Emission Prediction Model Based on CEEMDAN and AM-LSTM. Fuel 2022, 310, 122486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Ren, Y.; Suganthan, P.N.; Amaratunga, G.A.J. Empirical Mode Decomposition Based Ensemble Deep Learning for Load Demand Time Series Forecasting. Appl. Soft Comput. 2017, 54, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, X.; Shan, Z.; Fang, Y.; Lin, C. An LSTM-Based Method with Attention Mechanism for Travel Time Prediction. Sensors 2019, 19, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, D.; Sun, B.; He, Y.; Fuentes, S. Air Quality Prediction Based on a Spatiotemporal Attention Mechanism. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2021, 2021, 6630944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neagoe, A.; Tică, E.-I.; Vuță, L.-I.; Nedelcu, O.; Dumitran, G.-E.; Popa, B. Hybrid LSTM-ARIMA Model for Improving Multi-Step Inflow Forecasting in a Reservoir. Water 2025, 17, 3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, J.; Zhang, C.; Xu, X.; Qian, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fan, Y.; Hu, Q.; Mao, Y.; Zhao, X. River Water Quality Forecasting: A Novel LSTM-Transformer Approach Enhanced by Multi-Source Data. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2025, 197, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzaz, N.M.; Yusoff, M.K.; Aris, A.Z.; Juahir, H.; Ramli, M.F. Artificial Neural Network Modeling of the Water Quality Index for Kinta River (Malaysia) Using Water Quality Variables as Predictors. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2012, 64, 2409–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheela, K.G.; Deepa, S.N. Review on Methods to Fix Number of Hidden Neurons in Neural Networks. Math. Probl. Eng. 2013, 2013, 425740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, J.; Cui, Y.; Meng, D.; Wang, J.; Song, Y.; Mao, Y. Integrated Prediction of Water Pollution and Risk Assessment of Water System Connectivity Based on Dynamic Model Average and Model Selection Criteria. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Liu, W.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Liu, W. Ensemble Water Quality Forecasting Based on Decomposition, Sub-Model Selection, and Adaptive Interval. Environ. Res. 2023, 237, 116938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Suzuki, G.; Shioya, H. Sustainable Sewage Treatment Prediction Using Integrated KAN-LSTM with Multi-Head Attention. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-Q.; Luo, X.-Q.; Zhou, H.-B.; Chen, J.-J.; Yin, W.-X.; Song, Y.-P.; Wang, H.-B.; Yu, B.; Tao, Y.; Wang, H.-C.; et al. Leveraging Scenario Differences for Cross-Task Generalization in Water Plant Transfer Machine Learning Models. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 2025, 27, 100604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Indicator | Unit | Min | Max | Mean | Med | Std |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | - | 6.74 | 10.91 | 7.27 | 7.26 | 0.22 |

| COD | mg/L | 66.41 | 2841.00 | 217.73 | 169.70 | 165.00 |

| NH3-N | mg/L | 0.24 | 78.91 | 24.68 | 23.98 | 9.24 |

| TP | mg/L | 0.73 | 62.85 | 3.11 | 2.79 | 1.84 |

| TN | mg/L | 6.92 | 98.32 | 33.87 | 32.12 | 15.00 |

| Model Architecture Parameters | Training Parameters | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| STL LOSS | odd | Epoch | 500 |

| STL Period | 24 | Optimizer | Adam |

| Input Windows | 48 | Learning rate | 0.001 |

| Output Windows | 10 | Loss Function | MSE-Loss |

| Hidden units | 128 | Early Stopping | 20 |

| Dropout Rate | 0.3 | Scheduler Patience | 10 |

| L2 Regularization | e | Scheduler Factor | 0.5 |

| Indicator | Unit | Min | Max | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Std |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COD-Trend | mg/L | 88.86 | 333.64 | 136.32 | 164.15 | 213.21 | 52.48 |

| TN-Trend | mg/L | 9.71 | 48.78 | 28.42 | 33.40 | 37.43 | 7.14 |

| TP-Trend | mg/L | 1.04 | 5.04 | 2.39 | 2.75 | 3.29 | 0.76 |

| COD-Seasonal | mg/L | −96.91 | 132.51 | −10.15 | −0.46 | 15.33 | 20.13 |

| TN-Seasonal | mg/L | −15.33 | 24.87 | −3.34 | −1.05 | 1.08 | 6.06 |

| TP-Seasonal | mg/L | −1.47 | 3.17 | −0.35 | −0.13 | 0.16 | 0.60 |

| Target | Dataset Characteristics | Absolute Performance | Relative Performance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Params | Std | CV | R-square | MAE | RMSE | R-MAE |

| COD | 165 | 0.7578 | 0.9229 | 37.0777 | 48.4601 | 0.1703 |

| TN | 1.84 | 0.4428 | 0.9315 | 4.6791 | 6.9446 | 0.1381 |

| TP | 15 | 0.5916 | 0.9133 | 0.4827 | 1.2011 | 0.1542 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lei, W.; Yuan, F.; Xu, Y.; Nie, Y.; He, J. Bridging Time-Scale Mismatch in WWTPs: Long-Term Influent Forecasting via Decomposition and Heterogeneous Temporal Attention. Water 2026, 18, 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18030295

Lei W, Yuan F, Xu Y, Nie Y, He J. Bridging Time-Scale Mismatch in WWTPs: Long-Term Influent Forecasting via Decomposition and Heterogeneous Temporal Attention. Water. 2026; 18(3):295. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18030295

Chicago/Turabian StyleLei, Wenhui, Fei Yuan, Yanjing Xu, Yanyan Nie, and Jian He. 2026. "Bridging Time-Scale Mismatch in WWTPs: Long-Term Influent Forecasting via Decomposition and Heterogeneous Temporal Attention" Water 18, no. 3: 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18030295

APA StyleLei, W., Yuan, F., Xu, Y., Nie, Y., & He, J. (2026). Bridging Time-Scale Mismatch in WWTPs: Long-Term Influent Forecasting via Decomposition and Heterogeneous Temporal Attention. Water, 18(3), 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18030295