Abstract

Riverine bacteria are vital to geochemical cycling, climate change, and water environments, and the relative research requires knowledge from multiple disciplines, including microbiology, ecology and river dynamics. The influence of river dynamics and morphology on riverine bacteria is drawing increasing attention; yet, there are few comprehensive reviews on the riverine bacteria from the perspective of river dynamics. Therefore, this paper systematically reviews the research progress from the perspective of river dynamics, focusing on the research techniques and methods of riverine bacteria, the impact of hydrodynamic conditions, the ecological effects of dam construction, and the spatial distribution pattern of river bacteria. The review indicates that hydrodynamic processes and human activities such as dam construction drive community reorganization of planktonic and sedimentary bacteria across scales from microhabitats to macrolandscapes by altering aquatic environments, promoting microbial interactions, and affecting diversity, thereby shaping their complex spatiotemporal distribution patterns. Finally, this paper looks forward to future research directions, emphasizing the need to further reveal the diversity of planktonic and sedimentary bacteria, their genetic functions and community construction mechanisms, and to deeply analyze the feedback driving relationship between hydrodynamics, river morphology and riverine bacteria.

1. Introduction

Bacteria, diverse in species and widely distributed, serve as key drivers of the biogeochemical cycles of the Earth. Rivers are vital carriers for material and energy cycling in natural systems. Bacteria are widely present in rivers, playing a crucial role in Earth’s substance cycling, pollutant diffusion and migration, and greenhouse gas generation and emissions. Previous studies indicate that rivers are significant sources of greenhouse gases, transporting approximately 1 Gt of carbon into the ocean. This amount is in the same order of magnitude as the net carbon flux between the ocean and atmosphere, carbon flux from fossil fuel emissions, and carbon flux from forest fire emissions [1]. The nitrogen cycle in global inland water bodies is primarily driven by bacteria, which are the primary transformers of these nutrients. In addition, bacteria can decompose and mineralize organic pollutants such as carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus and sulfur, converting organic compounds into inorganic chemical components, thereby influencing water quality and contributing to water purification.

The diversity and community structure evolution of riverine bacteria are highly intricate. Microbial ecology studies reveal that riverine bacteria could profoundly alter the physical and chemical properties of water. Simultaneously, environmental factors such as water temperature, pH, conductivity, salinity, nutrients (carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus), and heavy metals affect the microbial community structure. The microbial communities also change periodically along with seasonal and diurnal cycles periodic variations [2,3,4,5,6,7]. Currently, over 95% of bacteria cannot be cultured in laboratories. Research on the evolution of riverine bacteria is still in the early exploratory stage, and knowledge of the diversity, geographical distribution, and community-building mechanisms of riverine bacteria needs enhancement [1,8].

The study on riverine bacteria spans microbial ecology, fluid dynamics and fluvial processes. However, the most current research centers on the relationship between river bacteria and water pollution and the water environment. At the same time, fewer studies have investigated the effects of hydrodynamics, river morphology and hydraulic engineering on river bacteria. The authors retrieved the 157 Chinese papers (including dissertations) in the China Knowledge Network database using the subject keyword “riverine bacteria.” Of these papers, only one was a review paper [9]. Most of these papers concentrate on the impact of river pollution (mainly urban rivers) and land use on the composition of river microbial communities. Conversely, fewer studies specifically examine the effects of hydrodynamics, river morphology, and hydraulic engineering on river bacteria, particularly in the absence of a scientific review of this study.

Hydrodynamic processes and channel evolution influence rivers’ physicochemical properties and microbial habitats. Dam construction substantially impacts riverine bacteria by altering the water–sediment conditions and boundary morphology upstream and downstream of the river. Furthermore, riverine bacteria are classified into two categories: those suspended in the water column and those deposited on the substrate. There is a pressing need for comparative and comprehensive studies that examine the impact of hydrodynamics, dam construction, river geomorphology, and habitat on bacteria, as bacteria in various habitats and spatial distributions respond differently to environmental factors and human perturbations.

Addressing the above-mentioned research gaps, this paper reviews research findings on the impact of multidimensional spatial scales of hydrodynamics, damming, and river morphology on riverine bacteria’s diversity and community structure. It synthesizes and compares the community composition and change rule of bacteria floating in the water body and deposited on the surface of the riverbed or adsorbed in the surface biofilm of the riverbed substrate, identifies existing research deficiencies, and provides scientific references for the future development of river microbiology as a cross-disciplinary subject.

2. Research Techniques and Methods for River Bacteria

2.1. Classification and Sampling Methods for River Bacteria

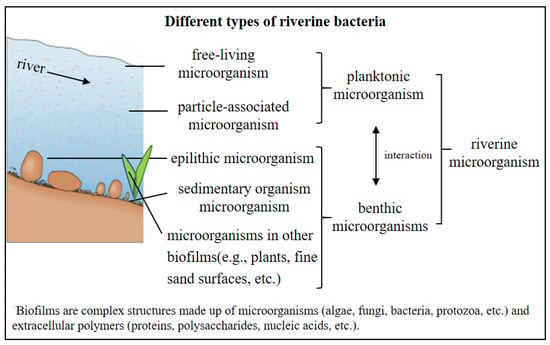

Classification and Sampling Methods for River Bacteria include bacteria, fungi and protozoa. Riverine bacteria can be divided into planktonic bacteria, sedimentary bacteria and epilithic bacteria according to their distribution location and propagation pattern. In this paper, sedimentary bacteria, epilithic bacteria, and bacteria adsorbed on organic or inorganic substrates in the surface layer of the riverbed, except planktonic bacteria, are collectively referred to as sedimentary bacteria. Planktonic bacteria can be subdivided into free-living bacteria suspended in the water and particle-adsorbed bacteria attached to suspended particles. Sedimentary bacteria refer to bacteria in the finer sediment or silt on the riverbed, and epilithic bacteria are bacteria adsorbed in the epilithic biofilm of pebbles. In addition, there are also bacteria adsorbed in the surface biofilm of fine sand, plants, wood, etc. (Romero et al., 2020) [10]. The main categories of riverine bacteria are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Different types of riverine bacteria.

Biofilm features a complex structure of bacteria and extracellular polymeric substances. These bacteria include algae, fungi, bacteria, and protozoa, while the extracellular polymeric substances are mainly composed of proteins, polysaccharides, and nucleic acids [11].

Different types of microbial samples have different field sampling methods. For planktonic bacteria, overlying water samples can be collected from 0 to 30 cm. The water samples will be collected through a filter membrane with a certain pore size. For instance, Wang (2021) [8] utilized a 3.0 µm filter membrane to collect particle-associated bacteria, followed by using a 0.22 µm filter membrane to capture free-living bacteria in the filtered water. When the surface sediment of the riverbed is fine or silt, a dropper or other tools can be used to directly collect 0~10 cm of surface sediment into sterile test tubes to determine and analyze sedimentary bacteria. Collection of epilithic bacteria typically involves randomly selecting cobblestones of certain sizes, scraping the epilithic biofilm from various cobblestones, and combining them in sterile tubes [4]. In field experiments, glass or ceramic plates are also placed in the riverbed, allowing biofilm growth over time before sampling. All microbial samples should be refrigerated during transport to the laboratory for analysis [12].

2.2. Research Techniques for River Bacteria

Before the 1970s, microbial research heavily relied on laboratory cultivation, mainly focusing on microbial morphology observation and classification. With the advent of the first-generation gene sequencing technologies in the late 20th century and early 21st century, molecular biology techniques such as the construction and sequencing of specific gene clone libraries gained prominence. This shift reduced dependence on pure microbial cultivation, enabling direct analysis of microbial communities. The emergence of second-generation sequencing technologies after 2010 significantly increased sequencing throughput and reduced costs. Third-generation sequencing technologies have also been introduced. Various analysis software such as Mothur, Usearch, QIME, and QIME2 have been developed and optimized, kicking off an explosive growth in microbiomics research [8].

Table 1 summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of culturable microbiomes, amplicon and metagenomics sequencing methods [13]. For cultivable microbiomes, collected samples are crushed, cultivated, purified, and sequenced. The strength of this method lies in targeted selection during cultivation, making strains suitable for specific applications such as pollution remediation. However, it demands high environmental and culture medium requirements, requires relatively complex procedures, takes an extended time (usually over 20 days), and incurs high costs.

Table 1.

Advantages, disadvantages, and application scenarios of high-throughput sequencing technologies for microbiomes (Liu et al., 2020 [13]).

High-throughput sequencing methods for microbiomes based on deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) commonly utilize amplicon sequencing and metagenomics sequencing. Amplicon sequencing is a highly targeted sequencing technique employed to analyze genetic information summarized in specific genomic regions of bacteria for variation. The target region is initially identified and captured, followed by flux sequencing, species identification, and bioinformatic analysis through database comparison [14]. This method is applicable to almost all environmental samples, using marker genes such as 16S rDNA, 18S rDNA, and internal transcribed spacers (ITS). Among them, 16S rDNA, commonly used for bacteria sequencing, encodes the DNA sequence corresponding to rRNA on bacterial chromosomes. It is widely present in both eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells, with a moderate relative molecular mass. It is easy to extract, exhibits conservative base sequences, and possesses constant physiological functions. After collecting environmental samples, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the obtained gene fragments enables the sequencing of a large number of sequences for microbial diversity analysis. Based on the obtained species composition table, software like PICRUSt or tax4Fun can be employed for gene function prediction. However, the limitation of this method is its resolution only to the genus level, susceptibility to primer bias and PCR cycle number, and inability to study genes. It can only rely on existing databases for species functional prediction.

Metagenomics sequencing extracts all microbial DNA directly from environmental samples, constructs genome libraries, and conducts high-throughput sequencing of the entire genome, providing information on the genetic composition and community functions of all bacteria. Compared to amplicon sequencing, metagenomics sequencing offers higher resolution, reaches species and strain-level precision, and enables sequencing of genes in samples to explore gene functions. However, it comes at a higher cost. Therefore, 16S rDNA amplicon sequencing can be employed to study microbial composition, while metagenomics sequencing is necessary for higher classification resolution and functional information [13]. In addition, there are research techniques for virus composition based on DNA and RNA, as well as the study of macro transcriptome based on RNA, which are not detailed here but can be referenced in relevant literature [13].

The main output files obtained from amplicon and metagenomics sequencing are species classification table and functional table. These data can be used for -diversity analysis (assessing diversity within samples), -diversity analysis (assessing differences in microbiome composition between different samples), environmental factor correlation analysis, species annotation analysis, co-occurrence network analysis, gene prediction, operational taxonomic unit (OTU) evolutionary analysis, biomarker analysis, and critical taxa analysis. These analyses help answer questions and form statistical analysis-related charts: What bacteria are present in the microbial community? Is there a significant difference between -diversity and -diversity? Which species, genes, or functional pathways serve as biomarkers for each group?

3. Impact of Hydrodynamic Conditions on Riverine Bacteria

3.1. Mechanisms of Flow Velocity, Discharge, and Flood Processes on Bacterial Communities

Hydrodynamic conditions, such as flow velocity, discharge, and flood processes, can alter the concentrations of chemical and nutrient substances (e.g., dissolved oxygen and dissolved organic carbon) in water. They also affect the habitat, community structure and composition of riverine bacteria. In addition, hydrodynamic processes such as the channelization of beach currents and inflow of tributaries into the confluence may introduce exogenous bacteria (e.g., bacteria in the soil) relative to mainstream bacteria. Currently, there is a lack of clarity regarding the mechanism of hydrodynamic effects on bacteria. Table 2 systematically summarizes representative studies on the direct effects of flow velocity, discharge, and flood processes on riverine bacterial communities. The literature indicates that lower flow velocities combined with finer sediment particles promote biofilm development and sedimentary bacterial abundance (Chen, 2017 [11]), while flow interruption leads to a decline in biofilm diversity (Timoner et al., 2014 [15]). Flood events, on the one hand, increase overall bacterial density by introducing external bacteria and nutrients, yet simultaneously reduce community diversity and enhance spatial homogeneity (Chiaramonte et al., 2013 [16]). On the other hand, floods can drive community succession, with soil-derived bacteria dominating during peak flow and freshwater taxa gradually recovering after the flood recedes (Carney et al., 2015 [17]). Together, these studies reveal the core mechanisms by which hydrodynamic processes directly regulate bacterial community structure and dynamics through altering habitat conditions, resource inputs, and biological transport.

Table 2.

Direct effects of flow, discharge, and floods on bacteria.

3.2. Differential Responses and Interactions of Planktonic and Sediment Bacteria to Flooding Processes

The characteristics of the response of planktonic and sedimentary bacteria to flood processes may differ, and riverbed scouring associated with hydrodynamic processes can result in interactions between planktonic and sedimentary bacteria. Table 3 compiles existing research on the differential responses and interactions between planktonic and sedimentary bacteria during flood events. The results show that planktonic bacterial communities are more sensitive to water-level fluctuations, while sedimentary bacteria remain relatively stable (Tang, 2021 [18]). Floods can release bacteria stored in riverbed sediments through scouring, leading to increased concentrations of indicator bacteria in the water column (Chu et al., 2014 [19]). During flood pulses, planktonic bacteria typically reach peak abundance in the recession phase and exhibit less spatial variation than attached biofilm bacteria (Palijan, 2010 [20]). Substrate type also influences bacterial adaptability to hydrological disturbances; for instance, epipsammic biofilms are more resistant than epilithic biofilms (Timoner et al., 2014 [15]). Moreover, planktonic communities recover slowly after flood disturbances, showing clear ecological lag (Muylaert & Vyverman, 2006 [21]). These findings collectively illustrate that planktonic and sedimentary bacteria employ distinct ecological strategies and recovery trajectories in response to flood disturbances, with complex interactions occurring at the water-sediment interface.

Table 3.

Differential responses of planktonic vs. sedimentary bacteria to floods.

Bacterial diversity is also shaped by multiple environmental drivers; representative influences are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Variations in bacterial diversity in response to major influencing factors.

4. Impact of Dam Construction on Riverine Bacteria

4.1. Impact of Dams on the Distribution of Bacterial Diversity Upstream and Downstream

Dam construction, as a dominant human hydraulic engineering activity, directly alters water temperature and hydrodynamic conditions (e.g., flow velocity, discharge stability) in the up-stream and downstream channels, while intercepting sediment to reduce downstream sediment influx. These human-induced environmental changes reshape the hydraulic, nutritional, and habitat conditions for riverine bacteria, thereby directly regulating bacterial diversity, community structure, and functional traits (e.g., nitrogen cycling pathways). The abundance of sedimentary bacteria species has decreased downstream of the dam in comparison to upstream of the dam, as evidenced by a more significant number of existing studies. However, there is some debate regarding the distinctions in the distribution of planktonic bacteria above and below the dam. As shown in Table 5, the reviewed studies collectively indicate that dam impacts on riverine bacterial communities are complex and context-dependent. For sedimentary bacteria, a consistent pattern emerges across multiple river systems (Yangtze, Lancang, and smaller rivers), with diversity significantly lower downstream of dams, primarily attributed to riverbed scouring. In contrast, the responses of planktonic bacteria are more variable: while some studies report higher abundance upstream or reduced key species downstream, others find minimal differences in community structure between upstream and downstream areas, suggesting influences from factors such as reservoir residence time and operational patterns. Furthermore, spatial distance and environmental heterogeneity are identified as key drivers shaping bacterial community variation in dam-affected river reaches.

Table 5.

Research results on the impact of dams on riverine bacterial communities.

4.2. Comparative Ecological Mechanisms of Planktonic and Sedimentary Bacteria in Response to Dams

Additional case studies in the upper Yangtze River further show that local-scale damming can reshape planktonic bacterial assemblages [35]. Longitudinal patterns in riparian-sediment bacterial communities and their responses to dam construction have also been documented [36].

Despite the differences of opinion in the above studies, community building may differ between planktonic and sediment bacteria upstream and downstream of dams. For instance, Wang et al. (2023) [37] found distinct compositions of comammox communities between the upstream and downstream of dams, indicating potential differences in nitrogen cycling pathways between the two areas. Luo et al. (2019) [38] investigated the impact of a hydropower station on bacteria in the Lancang River. The results showed that the lowest bacterial abundance appeared in the downstream, sedimentary bacteria were influenced by reservoir discharge flow rate, sediment particle size, and sediment type, while planktonic bacteria showed stronger correlations with physical and chemical properties of water, such as conductivity and total dissolved solids. Lu et al. (2022) [39] compared the evolution characteristics of planktonic bacteria in dam-affected and natural river channels in the upper reaches of the Yangtze River, and identified dispersal limitation and ecological drift as the main processes influencing microbial community changes in dam-affected river segments, whereas deterministic processes played a stronger role in microbial communities in natural river segments. Tang (2021) [18] concluded that diffusion limitation is the main ecological process of planktonic bacterial communities in the middle section of the Three Gorges Reservoir area. In contrast, it is controlled by environmental selection in the natural river section that is not influenced by the reservoir. Yan et al. (2015) [40] studied the impact of dams on planktonic bacterial communities, finding higher microbial -diversity in backwater areas, where low flow velocity, low turbidity, and high nitrogen content favored increased diversity of planktonic bacteria. Non-backwater areas exhibited more nitrogen-related -proteobacteria, and functional genes related to nitrogen cycling were significantly higher than in backwater areas, indicating stronger nitrogen transformation capabilities of planktonic bacteria in that region.

5. Spatial Distribution Patterns in River Bacteria

Riverine bacteria are distinguished by a spatial attenuation of similarity from upstream to downstream. At the same time, river morphology exhibits multi-scale heterogeneity, with distinct distributional characteristics at multi-dimensional spatial scales, including watershed, reach, and microbial habitat scales. In addition, the spatial distribution and evolutionary characteristics of planktonic bacteria and sedimentary bacteria are also quite different, constituting a complex spatial distribution pattern of riverine bacteria.

5.1. Spatial Decay Characteristics of Microbial Similarity

Rivers accumulate increasing amounts of nutrients from land erosion upstream to downstream. Intuitively, bacterial diversity should be more significant downstream in rivers [1,41]. However, Vannote et al. (1980) [42] found that the maximum bacterial a-diversity occurs in the middle of the river. Liu (2016) [1] studied a 4300-km-long section of the Yangtze River mainstem and showed that the maximum value of bacterial a-diversity also occurred in the middle reaches. Velimirov et al. (2011) [43] discovered that the bacterial population, morphological type composition, and bacterial colonization of the Danube River exhibited a consistent pattern as it traversed the river.

Microbial composition features a distance-decay relationship, indicating that the similarity of bacterial community composition decreases with increasing geographic distance. This phenomenon is related to microbial dispersion and environmental selection processes. For example, Gibbons et al. (2014) [44] measured the sedimentary bacteria of a 140 km-long river segment in the United States, finding a significant correlation between microbial functional gene composition and distance. Liu et al. (2015) [45] investigated planktonic bacteria in the water of 42 reservoirs and lakes in China. They found that bacteria with high abundance and rare bacteria both displayed significant distance-decay relationships, and the distance-decay relationship of abundant bacterial diversity was weaker than that of rare bacteria. Liu et al. (2023) [7] discovered that the distance-decay relationship of highly abundant bacteria was stronger than that of less abundant ones in Wu River and Pearl River, and the relationship was more pronounced in winter-spring than in summer-autumn. He et al. (2021) [46] explored planktonic bacteria in the Weihe River and its tributaries, and showed a significant correlation between the composition of planktonic bacteria in the main stream and geographic distance, whereas this relationship was not significant in the tributaries. Jiang (2021) [14] observed that nitrifying and denitrifying bacteria had distinct geographical and environmental distance-decay relationships. Notably, the decline slope of abundant taxa was considerably higher than that of rare taxa.

5.2. Differences in the Spatial Multiscale Distribution of Bacteria in Rivers and Watersheds

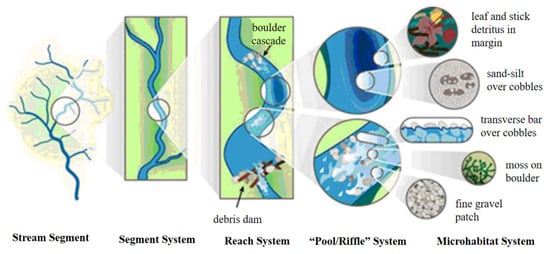

River morphology exhibits multi-scale characteristics (Figure 2), including basin scale, channel scale, reach scale, riverbed geomorphic unit scale (such as step-deep pool, deep channel–shallow shoal), and microhabitat scale for riverine organisms [47,48,49].

Figure 2.

River morphology at different spatial scales [47].

Table 6 systematically synthesizes key studies examining the distribution patterns of riverine bacteria across multiple spatial scales. Research conducted at large landscape scales, such as along the Yenisei and Yangtze Rivers, demonstrates that bacterial community composition clusters according to major geomorphic units and land-use types, reflecting broad environmental gradients (Kolmakova et al., 2014 [50]; Liu et al., 2018 [6]; Gotkow-ska-Plachta et al., 2016 [51]). At the scale of distinct fluvial morphologic units, studies reveal significant variation in sedimentary microbial diversity among habitats such as rapids, deep pools, and floodplains, with diversity often highest in depositional environments (He, 2020 [52]). Finally, at the microhabitat scale, investigations into substrate type—including cobbles, sands, and artificial materials—show that sediment grain size, heterogeneity, and surface properties critically shape biofilm community structure, functional gene abundance, and overall microbial diversity (Romero et al., 2020 [10]; Chen, 2017 [11]; Liu et al., 2023 [7]; Hellal et al., 2016 [12]; Zheng et al., 2024 [34]). Collectively, these findings underscore how spatial scale—from watershed landscapes to individual sediment grains—acts as a fundamental organizer of riverine bacterial assemblages by mediating habitat heterogeneity, resource availability, and ecological interactions.

5.3. Comparison of Differences Between Planktonic and Sedimentary Bacteria

There are discernible disparities in the diversity, community structure, and gene functionalities of planktonic and sedimentary bacteria, which may have different response patterns to hydrodynamic processes such as flooding, changes in river morphology and hydraulic engineering. Table 7 compares the differences between river planktonic and sedimentary bacteria in terms of diversity and influencing factors, as well as the interaction of the two types of bacteria with changes in river flushing and siltation.

Currently, most studies indicate that the diversity and stability of sedimentary bacteria surpass those of planktonic bacteria. For example, studies in major river systems such as the Yangtze River reveal that sedimentary bacteria possess higher richness and diversity, serve as the primary contributors to overall riverine microbial diversity, and show resilience to seasonal temperature fluctuations, in contrast to the more variable planktonic communities (Liu et al., 2018 [6]; Tang, 2021 [18]). This pattern is further supported by findings that sedimentary bacteria can significantly contribute to the composition of planktonic communities (Staley, 2015 [53]) and demonstrate strong seasonal continuity (Wang, 2021 [8]). However, notable exceptions exist, particularly in environments with high suspended sediment loads such as the Yellow River, where planktonic bacteria display equal or even greater diversity (Xia et al., 2014 [54]; Feng et al., 2009 [55]), or in pristine headwaters (Bao, 2020 [56]). These divergent patterns highlight that the relative diversity of planktonic and sedimentary bacteria is not absolute but is mediated by key environmental drivers. Chief among these is suspended sediment concentration, which enhances habitat availability and resources for particle-attached bacteria, thereby boosting planktonic bacterial richness and altering the typical diversity hierarchy, as evidenced by the positive correlation between denitrifier abundance and sediment load (Liu et al., 2013 [57]). Additional factors such as pollution levels and sediment grain size further modulate these complex and context-dependent relationships.

Table 6.

Summary of studies on riverine bacterial distribution across spatial scales.

Table 6.

Summary of studies on riverine bacterial distribution across spatial scales.

| Spatial Scale Category | Reference Documentation | Research Area | Verdict |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large Spatial Scales (Landscapes & Landforms) | Kolmakova et al. (2014) [50] | A 1800 km stretch of the Yenisei River | Three distinctly different bacterial communities corresponded to major landscape scales (montane coniferous forest, plains coniferous forest, and forested tundra-covered permafrost zone). |

| Liu et al. (2018) [6] | 50 sites along the main stem and tributaries of the Yangtze River | The clustering of both planktonic and sedimentary microbial compositions corresponded to five different landforms: mountains, hills, basins, hills-mountains, and plains. | |

| Gotkowska-Plachta et al. (2016) [51] | The Aina River in Poland, intersecting forests, agricultural, and urban land | Different types of land use (forest, agricultural, urban) significantly influenced the differences in bacterial populations. | |

| Scale of Fluvial Geomorphic Units | He (2020) [52] | Three habitats (rapids, deep pools, flood land) in four rivers | Significant differences in sediment/water nutrients were found among habitats. The highest sedimentary microbial diversity was in flood lands, the lowest in rapids. Variation within the same habitat was less than between different river environments. |

| Microhabitat Scale (Riverbed Substrates) | Romero et al. (2020) [10] | Biofilms on different substrate types | Biofilms on cobbles/rocks had a higher proportion of primary producers, while those on finer sediments fostered more heterotrophic bacteria. Epipsammic biofilms (on sand) had higher microbial diversity than epilithic biofilms (on rocks). |

| Chen (2017) [11] | Experimental study on sediment particle size and flow velocity | Bacterial diversity was higher on fine sand surfaces than on coarse sand. The growth of epilithic biofilms was more sensitive to sediment particle size than to flow velocity. | |

| Microhabitat Scale (Riverbed Substrates) | Liu et al. (2023) [7] | Rivers with varying bed-sediment heterogeneity | A higher abundance of bacterial denitrification genes was found in rivers with higher bed-sediment heterogeneity. |

| Hellal et al. (2016) [12] | Field experiment with natural/artificial substrates in a French river | The diversity of cultured bacteria differed significantly among substrates (natural vs. artificial, organic vs. inorganic). | |

| Zheng et al. (2024) [34] | Shiting River channel in Sichuan, biofilms on sediments of varying grain sizes | Bacterial diversity in surface-layer fine sand was significantly higher than on pebbles. Significant intergroup differences existed between bacteria on sediment <2 mm and those attached to pebbles >2 mm. |

Table 7.

Comparison of differences in characteristics and influencing factors between planktonic bacteria and sedimentary bacteria in rivers.

Table 7.

Comparison of differences in characteristics and influencing factors between planktonic bacteria and sedimentary bacteria in rivers.

| Characteristics/Influencing Factors | Discrepancy | Bibliography |

|---|---|---|

| variegation | Perspective 1: sedimentary bacteria are more diverse than planktonic bacteria | Feng et al., 2009 [55]; Liu et al., 2018 [6]; Wang, 2021 [8]; Tang, 2021 [18] |

| Perspective 2: planktonic bacteria are more diverse than sedimentary bacteria | Xia et al., 2014 [54]; Bao, 2020 [56] | |

| temperature | Planktonic bacteria (more than sedimentary bacteria) are more affected by temperature | Liu et al., 2018 [6]; Zhang et al., 2021 [58] |

| DO | Planktonic bacteria are more affected by DO | Liu et al., 2018 [6] |

| salinity | Planktonic bacteria are more significantly affected by salinity | Feng et al., 2009 [55]; Wang, 2021 [8] |

| seasonality | Planktonic bacteria vary significantly with the seasons | Feng et al., 2009 [55]; Liu et al., 2018 [6] |

The mechanisms underlying the construction of planktonic and sedimentary microbial communities also differ. For instance, Feng et al. (2009) [55] found that planktonic bacteria belonged to two clusters in the estuarine and offshore regions of the Yangtze River. However, no such spatial differences were observed in sedimentary bacteria. Wang’s (2021) [8] study in the Yellow River estuary also showed that planktonic bacteria in the water column showed a prominent grouping with salinity, while sedimentary bacteria showed no apparent relationship with salinity. Homogeneous selection was the most crucial ecological process in constructing sedimentary bacterial communities, while random processes primarily drove the Planktonic bacterial community construction. Zhang et al. (2021) [58] investigated the planktonic and substrate bacterial communities of numerous rivers and lakes in the southeastern Tibetan Plateau, which are primarily supplied by glaciers. They discovered significant differences in bacterial communities between water and sediment, with limited interactions. Changes primarily influenced the bacterial diversity in sediment in nitrogen compounds and pH, whereas the diversity of planktonic bacteria was more susceptible to evapotranspiration, elevation, and mean annual temperature.

6. Conclusions and Prospects

This paper, centered on the interdisciplinary research theme of river bacteria, spanning microbial ecology, hydraulics, and river dynamics, introduces existing research technologies, methods and results. It summarizes the current research on the effects of hydrodynamics and damming on riverine bacteria and describes the mechanisms of changes in riverine bacteria at spatial scales, spatial distance attenuation, floating and benthic environments. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) In terms of hydrodynamics, changes in flow velocity and discharge can influence river bacteria by altering chemical and nutrient concentrations in the water. External bacteria, relative to instream bacteria, are introduced into the main stream through channelization of flood land flow into the main channel and tributary confluence. During flood processes, there may be differences in response characteristics between planktonic bacteria, sedimentary bacteria, and different types of sedimentary bacteria (e.g., rock-and sand-attached biofilm bacteria).

(2) Dam construction not only alters water temperature and hydrodynamic conditions in the upstream and downstream channels but also intercepts sediment, reducing sediment influx and intensifying bed scouring and armoring downstream. Scour roughening of the riverbed was not conducive to sedimentary bacterial growth downstream of the dam, sedimentary bacterial diversity was generally lower downstream of the dam than upstream of the dam. The conclusion that planktonic bacteria were affected by damming was highly controversial and related to factors such as the way the reservoir was utilized.

(3) River bacteria have a complex spatial and temporal distribution pattern. On the one hand, the similarity of bacterial community composition decreases as spatial distance increases. On the other hand, rivers and watersheds exhibit differences in bacterial communities at multiple spatial scales, including regional scales (e.g., mountains, hills, basins, plains), scales of fluvial geomorphic units (e.g., rapids, deep pools, shallows), and scales of bacterial habitats (e.g., varying riverbed sediment sizes). The distribution of river microbes varies across these geomorphic units. The differences in bacteria at these scales may be less pronounced for the same river than for distinct rivers.

(4) The diversity and change characteristics of planktonic bacteria and sedimentary bacteria are distinct. According to the majority of research, planktonic bacteria are more susceptible to factors such as temperature, dissolved oxygen, and season than sedimentary bacteria. Although sedimentary bacteria are more stable than planktonic bacteria and their diversity is greater than planktonic bacteria, the abundance of planktonic bacteria may be greater than sedimentary bacteria in rivers with a higher sediment content.

Future research avenues should consider the following: (1) Current research on river bacteria is still in its early stages, with conflicting conclusions on various issues. Extensive and in-depth comparative studies are needed to investigate the impact of different hydraulic projects and river morphologies on river bacteria.

(2) Mechanistic studies are required to explore the composition of and changes in planktonic bacteria and sedimentary bacteria communities in relation to water flow and sediment movement. Current research on riverine bacteria focuses mostly on the correlation between bacterial communities and environmental factors while lacking consideration of the link between bacteria and the mechanical mechanisms of water–sand transport.

(3) Experimental research on river bacteria is currently scarce. Experimental studies, which allow the control of multiple variables and focus on the changes in target variables, are urgently needed to fill the gap in experimental research on river bacteria.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.D. and S.Z.; investigation Y.D.; writing—original draft, Y.D. validation S.Z.; writing—review and editing, S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52479071).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, T. High-throughput Sequencing for Spatiotemporal Characterization of Microbial Community Structures and Functions in the Yangtze River. Ph.D. Thesis, Peking University, Beijing, China, 2016. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Osgood, M.P.; Boylen, C.W. Seasonal variations in bacterial communities in adirondack streams exhibiting pH gradients. Microb. Ecol. 1990, 20, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, M.A.; Leff, L.G. Nutrients and other abiotic factors affecting bacterial communities in an Ohio River (USA). Microb. Ecol. 2007, 54, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Kim, C.; Yoshimizu, C.; Kohzu, A.; Tayasu, I.; Nagata, T. Longitudinal changes in bacterial community composition in river epilithic biofilms: Influence of nutrients and organic matter. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. Int. J. 2009, 54, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-González, C.; Proia, L.; Ferrera, I.; Gasol, J.M.; Sabater, S. Effects of large river dam regulation on bacterioplankton community structure. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2012, 84, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, A.N.; Wang, J.; Liu, S.; Jiang, X.; Dang, C.; Ni, J. Integrated biogeography of planktonic and sedimentary bacterial communities in the Yangtze River. Microbiome 2018, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Wang, B.; Yang, M.; Li, W.; Shi, X.; Liu, C.Q. The different responses of planktonic bacteria and archaea to water temperature maintain the stability of their community diversity in dammed rivers. Ecol. Process. 2023, 12, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.N. Microbial Community Assembly, Succession and Ecological Function in the Yellow River Delta Wetland. Ph.D. Thesis, Shandong University, Qingdao, China, 2021. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Lei, M.T.; Yang, N. Research and Prospect on river microbial ecology. Water Resour. Prot. 2022, 38, 190–197. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Romero, F.; Acuña, V.; Sabater, S. Multiple stressors determine community structure and estimated function of river biofilm bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e00291-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S. Experiment on Biofilm Growth of Cohesive Sediment and Effect on Adsorption or Desorption. Ph.D. Thesis, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, 2017. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hellal, J.; Michel, C.; Barsotti, V.; Laperche, V.; Garrido, F.; Joulian, C. Representative sampling of natural biofilms: Influence of substratum type on the bacterial and fungal communities structure. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.X.; Qin, Y.; Chen, T.; Qin, Y.; Lu, M.; Qian, X.; Guo, X.; Bai, Y. A practical guide to amplicon and metagenomic analysis of microbiome data. Protein Cell 2020, 12, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.L. The geographic Distribution Patterns and Assembly Mechanisms of Nitrifying-and Denitrifying Microbial Communities in the Typical Wetland Ecosystems. Ph.D. Thesis, Wuhan Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan, China, 2021. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Timoner, X.; Buchaca, T.; Acuña, V.; Sabater, S. Photosynthetic pigment changes and adaptations in biofilms in response to flow intermittency. Aquat. Sci. 2014, 76, 565–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaramonte, J.B.; Roberto, M.d.C.; Pagioro, T.A. Seasonal dynamics and community structure of bacterioplankton in upper Paraná River floodplain. Microb. Ecol. 2013, 66, 773–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, R.L.; Mitrovic, S.M.; Jeffries, T.; Westhorpe, D.; Curlevski, N.; Seymour, J.R. River bacterioplankton community responses to a high inflow event. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. Int. J. 2015, 75, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q. Effect of Damming on Microbial Community in the Upper Reaches of the Yangtze River. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing Jiaotong University, Chongqing, China, 2021. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chu, Y.; Tournoud, M.G.; Salles, C.; Got, P.; Perrin, J.L.; Rodier, C.; Troussellier, M. Spatial and temporal dynamics of bacterial contamination in South France coastal rivers: Focus on in-stream processes during low flows and floods: Bacterial contamination in South France river: Low flow and floods. Hydrol. Process. 2014, 28, 3300–3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palijan, G. Different impact of flood dynamics on the development of culturable planktonic and biofilm bacteria in floodplain lake. Pol. J. Ecol. 2010, 58, 439. [Google Scholar]

- Muylaert, K.; Vyverman, W. Impact of a flood event on the planktonic food web of the schelde estuary (Belgium) in spring 1998. Hydrobiologia 2006, 559, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVilbiss, S.E.; Taylor, J.M.; Hicks, M. Salinization and sedimentation drive contrasting assembly mechanisms of planktonic and sediment-bound bacterial communities in agricultural streams. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 5615–5633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engloner, A.I.; Vargha, M.; Kós, P.; Borsodi, A.K. Planktonic and epilithic prokaryota community compositions in a large temperate river reflect climate change related seasonal shifts. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0292057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Garcia, A.; Rizos, D.; Diskin, M.G.; Morris, D.G. Mechanism of LH release after peripheral administration of kisspeptin in cattle. J. Endocrinol. 2022, 255, 279–290. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, S.; Meng, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L. The potential linkage between sediment oxygen demand and microbes and its contribution to the dissolved oxygen depletion in the Gan River. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1413447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfiansah, Y.R.; Hassenrück, C.; Kunzmann, A.; Taslihan, A.; Harder, J.; Gärdes, A. Bacterial abundance and community composition in pond water from shrimp aquaculture systems with different stocking densities. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Cheng, L.; Wang, L.; Zhu, T.; Cai, W.; Hua, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W. Changes of bacterial communities in response to prolonged hydrodynamic disturbances in the eutrophic water–sediment systems. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Ren, M.; Xu, Y.; Wang, J. Metagenomic insights into surface sediment microbial community and functional composition along a water-depth gradient in a subtropic deep lake. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1614055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, C.; Hein, T.; Kavka, G.; Mach, R.L.; Farnleitner, A.H. Longitudinal changes in the bacterial community composition of the Danube River: A whole-river approach. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, P.; Chen, J.; Miao, L.; Feng, T.; Liu, S. How bacterioplankton community can go with cascade damming in the highly regulated Lancang-Mekong River Basin. Mol. Ecol. 2018, 27, 4444–4458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Tang, Q.; Lu, L.; Wang, Y.; Izaguirre, I.; Li, Z. Changes in planktonic and sediment bacterial communities under the highly regulated dam in the mid-part of the Three Gorges Reservoir. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 839–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Wu, H.; Yang, N.; Hui, C. Dams shift microbial community assembly and imprint nitrogen transformation along the Yangtze River. Water Res. 2021, 189, 116579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Zou, X.; Yang, J.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Guo, J.; Li, Z. Biogeography of eukaryotic plankton communities along the upper Yangtze River: The potential impact of cascade dams and reservoirs. J. Hydrol. 2020, 590, 125495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Liu, M.; Chen, Z.; An, C. Study of bacterial communities in the biofilms on the bed sediments with different particle sizes in the Shiting River, Sichuan. Yangtze River 2024, 55, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, Z.; Tang, Q.; Li, R.; Lu, L. Local-scale damming impact on the planktonic bacterial and eukaryotic assemblages in the upper Yangtze River. Microb. Ecol. 2023, 85, 1323–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, P.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Miao, L.; Liu, S.; Yuan, Q. Bacterial communities in riparian sediments: A large-scale longitudinal distribution pattern and response to dam construction. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Jin, H.; Chen, J.; Zhou, K.; Chen, J.; Zhu, G. Effects of dam building on the occurrence and activity of comammox bacteria in river sediments and their contribution to nitrification. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 864, 161167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Xiang, X.; Huang, G.; Song, X.; Wang, P.; Fu, K. Bacterial abundance and physicochemical characteristics of water and sediment associated with hydroelectric dam on the Lancang River China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.H.; Tang, Q.; Li, H.; Li, Z. Damming river shapes distinct patterns and processes of planktonic bacterial and microeukaryotic communities. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 24, 1760–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Bi, Y.; Deng, Y.; He, Z.; Wu, L.; Van Nostrand, J.D.; Zhou, J. Impacts of the Three Gorges Dam on microbial structure and potential function. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besemer, K.; Singer, G.; Quince, C.; Bertuzzo, E.; Sloan, W.; Battin, T.J. Headwaters are critical reservoirs of microbial diversity for fluvial networks. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2013, 280, 20131760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vannote, R.L.; Minshall, G.W.; Cummins, K.W.; Sedell, J.R.; Cushing, C.E. The River Continuum Concept. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1980, 37, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velimirov, B.; Milosevic, N.; Kavka, G.G.; Farnleitner, A.H.; Kirschner, A.K. Development of the bacterial compartment along the Danube River: A continuum despite local influences. Microb. Ecol. 2011, 61, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbons, S.M.; Jones, E.; Bearquiver, A.; Blackwolf, F.; Roundstone, W.; Scott, N.; Gilbert, J.A. Human and environmental impacts on river sediment microbial communities. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yang, J.; Yu, Z.; Wilkinson, D.M. The biogeography of abundant and rare bacterioplankton in the lakes and reservoirs of China. ISME J. 2015, 9, 2068–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Pan, B.; Yu, K.; Zheng, X.; Wu, Y.; Xiao, L.; Zhu, P. Determinants of bacterioplankton structures in the typically turbid Weihe River and its clear tributaries from the northern foot of the Qinling Mountains. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 121, 107168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frissell, C.A.; Liss, W.J.; Warren, C.E.; Hurley, M.D. A hierarchical framework for stream habitat classification: Viewing streams in a watershed context. Environ. Manag. 1986, 10, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurnell, A.M.; Rinaldi, M.; Belletti, B.; Bizzi, S.; Blamauer, B.; Braca, G.; Ziliani, L. A multi-scale hierarchical framework for developing understanding of river behaviour to support river management. Aquat. Sci. 2016, 78, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mendonca, B.C.C.; Mao, L.; Belletti, B. Spatial scale determines how the morphological diversity relates with river biological diversity. Evidence from a mountain river in the central Chilean Andes. Geomorphology 2021, 372, 107447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmakova, O.V.; Gladyshev, M.I.; Rozanov, A.S.; Peltek, S.E.; Trusova, M.Y. Spatial biodiversity of bacteria along the largest Arctic river determined by next-generation sequencing. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2014, 89, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotkowska-Płachta, A.; Gołaś, I.; Korzeniewska, E.; Koc, J.; Rochwerger, A.; Solarski, K. Evaluation of the distribution of fecal indicator bacteria in a river system depending on different types of land use in the southern watershed of the Baltic Sea. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2016, 23, 4073–4085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.L. Microbial Diversity of Sediment in the Riffle-Deep Pool-Beach Land Systems of Four Rivers, Xi’an, and Strategies for Restoration of Degraded Rivers. Master’s Thesis, Chang’an University, Xi’an, China, 2020. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Staley, C.; Gould, T.J.; Wang, P.; Phillips, J.; Cotner, J.B.; Sadowsky, M.J. Species sorting and seasonal dynamics primarily shape bacterial communities in the Upper Mississippi River. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 505, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, N.; Xia, X.; Liu, T.; Hu, L.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, X.; Dong, J. Characteristics of bacterial community in the water and surface sediment of the Yellow River, China, the largest turbid river in the world. J. Soils Sediments 2014, 14, 1894–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.W.; Li, X.R.; Wang, J.H.; Hu, Z.Y.; Meng, H.; Xiang, L.Y.; Quan, Z.X. Bacterial diversity of water and sediment in the ChangBao estuary and coastal area of the East China Sea. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2009, 70, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, T. The Influence of Seasonal Variation on the Microbial Community of Mohe River Silt and Water Environment. Master’s Thesis, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin, China, 2020. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Xia, X.; Liu, S.; Mou, X.; Qiu, Y. Acceleration of denitrification in turbid rivers due to denitrification occurring on suspended sediment in oxic waters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 4053–4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Shi, Y.; Liu, X.; Yang, Y.; Chu, H. Co-existing water and sediment bacteria are driven by contrasting environmental factors across glacier-fed aquatic systems. Water Res. 2021, 198, 117139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.