Abstract

In this study, the stomach contents of the crocodile toothfish Champsodon snyderi from the offshore waters of the South Sea of Korea were analyzed to understand their feeding characteristics. Bottom-trawlers in the South Sea of Korea were used to collect a total of 228 C. snyderi individuals with lengths ranging from 3.6 cm to 12.3 cm. Based on the index of relative importance and variations in the stomach contents according to fish size, C. snyderi was identified as a spatiotemporal opportunistic feeder that consumes abundant prey resources in the South Sea of Korea. Although no distinct dietary shift was observed with growth, there was a decreasing and increasing trend in the proportion of amphipods and shrimp consumed, respectively, in association with increasing C. snyderi body size in the nearshore waters of the South Sea of Korea. In addition, differences in the stomach content composition were observed in relation to interactions between season and size. Our findings indicate that the feeding characteristics of C. snyderi are affected by the abundance and composition of prey within its habitat.

1. Introduction

Benthic ecosystems in offshore marine environments are structurally and functionally vital systems maintained through complex food web interactions among a diverse range of organisms. Secondary consumers, acting as mesopredators, play a crucial role in sustaining ecosystem functionality by mediating energy transfer between lower trophic levels and top predators, and by regulating community structure [1]. Champsodon snyderi Franz, 1910 (crocodile toothfish), a small-to-medium-sized species belonging to the family Champsodontidae, primarily inhabits sandy or muddy sediments along the continental shelf boundary (at depths of about 50–400 m) within subtropical and temperate regions, including the East China Sea, southern waters of Japan, and Tokyo Bay [2,3,4]. In Korean waters, C. snyderi is frequently observed along the coastal regions of Jeju Island and the South Sea. The distribution of this species is strongly associated with the Tsushima Warm Current, and it plays a mesopredatory role in local fish assemblages. Notably, C. snyderi exhibits nocturnal behavior and engages in diel vertical migration to feed on planktonic prey in the surface layer, thereby mediating the transfer of energy from benthic habitats to the pelagic environment [5,6]. Although the movement ecology of C. snyderi has not been explicitly classified as either resident or migratory in previous studies, the species has been consistently described as a benthic or demersal fish and is frequently captured by bottom trawls. Taken together, these characteristics suggest that C. snyderi exhibits a resident-like demersal lifestyle while maintaining diel vertical migration, primarily associated with nocturnal feeding activity.

Numerous studies have investigated the feeding habits and trophic-level dynamics of ecologically similar demersal fishes, such as those in the families Gadidae and Atherinae. For instance, Yang et al. analyzed the diet of Saurida tumbil in the Beibu Gulf and reported that its main prey comprised juvenile fish and crustaceans, with diet composition and trophic levels varying according to environmental changes and individual growth [7]. In Korea, similar studies have been conducted on species that occupy similar ecological niches to those of C. snyderi, such as Acropoma japonicum and Argentina kagoshimae. These species also play important roles in mediating energy flows within benthic ecosystems [8,9].

In recent years, the offshore waters of the South Sea have experienced notable shifts in benthic biological communities owing to environmental changes, such as rising sea temperatures driven by climate change. These shifts include alterations in species interactions, distribution, community composition, and overall biodiversity [10,11,12,13,14]. Variations in prey communities are likely to alter the feeding strategies and ecological roles of mesopredators such as C. snyderi. Fish community structures in the East China Sea exhibit clear spatial and seasonal variations, reflecting the responses of fish communities to environmental change [15].

However, ecological research on C. snyderi, particularly regarding its feeding habits, remains limited, and it has largely been confined to a few studies conducted in the southern waters of Japan and adjacent regions of East Asia, including the East China Sea [6,16]. In contrast, corresponding data for Korean waters, particularly for the South Sea of Korea, remain virtually nonexistent. Although C. snyderi is not a direct target species of commercial fisheries, FishBase data indicate that it occupies a trophic level of approximately 2.8 or higher, classifying it as a mesopredator that contributes to energy transfer and regulation of the prey community structure within benthic food webs [17].

Mesopredator diets are known to shift flexibly in response to environmental conditions, individual growth, and prey availability. As prey selection can vary with both biotic and abiotic factors, it is essential to conduct detailed studies on the trophic ecology of such species to understand the energy flow and community structure dynamics within marine ecosystems [18].

The present study is the first to comprehensively elucidate the feeding ecology of C. snyderi in the South Sea of Korea based on a quantitative stomach content analysis. Specifically, we examined the diet composition, trophic level, and seasonal and size-related (ontogenetic) variations in the stomach contents of C. snyderi, a mesopredator in offshore benthic ecosystems. By integrating these analyses, this study aimed to provide new understanding of the ecological role of C. snyderi in structuring benthic communities and contributing to benthic–pelagic coupling within Korean marine ecosystems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Sample Collection

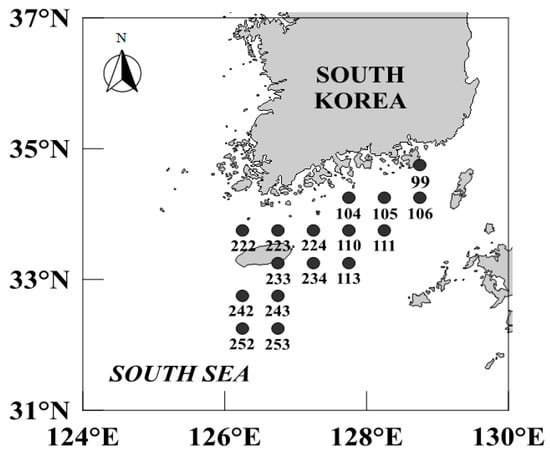

We collected C. snyderi specimens from the South Sea of Korea in February, May, August, and November of 2021 at 16 trawl survey stations (99, 104, 105, 106, 110, 111, 113, 222, 223, 224, 233, 234, 242, 243, 252, and 253) (Figure 1). The samples were obtained using bottom trawl nets aboard the research vessels Tamgu 20, 22, and 23 conducted by the National Institute of Fisheries Science (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Photographs of the crocodile toothfish, Champsodon snyderi, collected from the offshore waters of the South Sea of Korea.

Figure 2.

Map showing the fishing area in the offshore waters of the South Sea of Korea in which the crocodile toothfish, Champsodon snyderi, was sampled in the present study.

Sampling was conducted at depths ranging from 68.9 to 129.4 m, and all sampling operations were primarily conducted during daytime hours. The near-bottom water temperature at each sampling station was measured using a CTD sensor and ranged from 9.37 °C to 17.2 °C during the survey period.

Each specimen was measured for total length (TL, 0.1 cm precision) and body weight (BW, 0.1 g precision), after which the stomachs were removed onboard, fixed in 10% formalin (Samchun Pure Chemical Co., Ltd., Pyeongtaek-si, Republic of Korea), and later examined in the laboratory.

2.2. Stomach Content Analysis

Stomach contents were inspected using a stereomicroscope (LEICA L2, Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany), and prey organisms were classified to the finest feasible taxonomic resolution, ideally at the species level. Prey identification was conducted based on identification keys and field guides provided by Kaname [19] and Hong [20]. For quantitative analysis, prey items were counted individually, and wet weight was measured with a precision of 0.0001 g. When digestion hindered accurate species-level identification, prey were assigned to higher taxonomic categories (genus, family, or order). Stomach content data were expressed as frequency of occurrence (%F), numerical proportion (%N), and weight proportion (%W), which were calculated using the following equations [21],

where Ai refers to the number of C. snyderi individuals in which a particular prey item occurred, while N denotes the total number of individuals that consumed the prey. The variables Ni and Wi represent the numerical abundance and wet weight of each prey category, respectively. The total number and total wet weight of all prey items are given by Ntotal and Wtotal. The index of relative importance (IRI) was calculated according to Pinkas et al. [22] and subsequently expressed as a percentage (%IRI),

For the analysis of size-dependent dietary patterns, C. snyderi individuals were divided into three length-based groups according to total length: <8.0 cm (small), 8.0–9.0 cm (medium), and ≥9.0 cm (large). Information about the size at maturity for C. snyderi is not sufficiently available in existing literature; therefore, individuals were not separated into juvenile and adult stages in this study. Accordingly, size classes were defined based on clear patterns of change in the dietary composition. To examine seasonal patterns in diet composition, samples were categorized into four periods corresponding to spring (May), summer (August), autumn (November), and winter (February).

2.3. Trophic Level

To evaluate the ecological role of C. snyderi, its trophic level (TLk) was determined based on the equation proposed by Cortés [23],

In this equation, Pj refers to the proportional contribution of prey category j based on %IRI, while TLj indicates the corresponding trophic level of that prey group. The %IRI values were calculated based on the numerical abundance, wet weight, and frequency of occurrence of each prey category, and were standardized such that the sum of Pj across all prey categories was 1. Trophic level estimates for prey categories (TLj) were compiled from multiple published sources and averaged to obtain representative values [23,24,25]. When species-level or trophic-level values were unavailable, the average values at the genus or family level were used. A detailed list of prey categories and their corresponding trophic level values is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Prey categories applied in the calculation of standardized dietary composition and trophic levels for the crocodile toothfish, Champsodon snyderi. Mean trophic level values for each prey group were sourced from Cortés [23], Pauly et al. [24], and Ebert and Bizzarro [25].

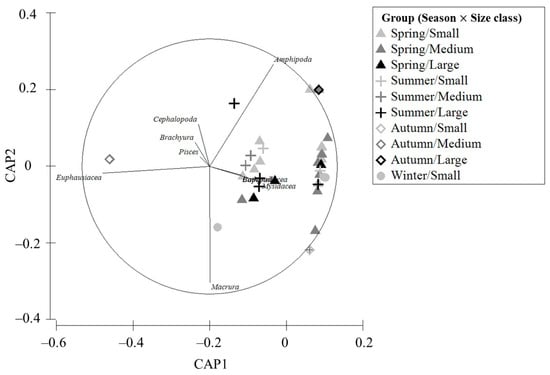

2.4. Multivariate Analysis of Stomach Content Composition

To evaluate the effects of size class, season, and their interaction (size class × season) on the stomach content composition of C. snyderi, a two-way permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) was performed. When significant differences were detected, canonical analysis of principal coordinates (CAP) was subsequently applied to determine the prey taxa most strongly associated with the observed patterns. Prey items exhibiting correlation coefficients ≥ 0.4 were visualized on the first two CAP axes. For multivariate analyses, individuals within each size class and season were randomly pooled into subsets of 3–6 specimens, and mean weight proportions were calculated for each subset. To reduce the influence of highly dominant prey categories, the mean weight data were square root transformed prior to analysis, and a Bray–Curtis similarity matrix was generated. All statistical procedures were conducted using Microsoft Excel 2014, PRIMER v6 (www.primer-e.com), and the PERMANOVA+ add-on package (version 1.0.3) [26].

3. Results

3.1. Environmental Variation

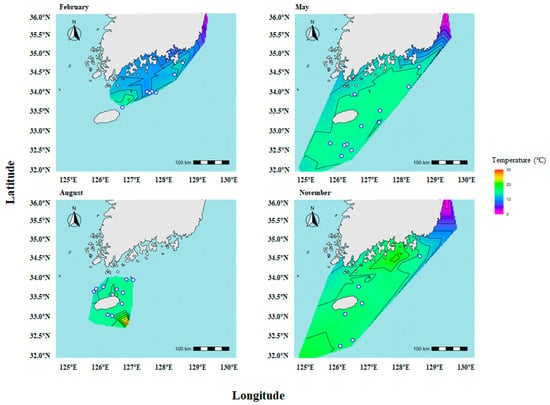

The occurrence patterns of C. snyderi were examined in relation to monthly variations in sea temperature, using in situ data obtained from line-transect oceanographic surveys conducted by the National Institute of Fisheries Science and provided by the Korea Oceanographic Data Center (KODC) (Figure 3). In February, occurrence points were mainly distributed within low bottom-temperature waters ranging from 9.4 °C to 14.7 °C, indicating that C. snyderi can inhabit relatively cold benthic environments during winter. In May, occurrences were predominantly observed in bottom waters with stable temperatures of 14.1–15.0 °C across the study area. In August, occurrence points were primarily associated with bottom temperatures ranging from 13.4 °C to 16.6 °C. By November, bottom water temperatures ranged from 14.7–16.2 °C, and occurrence points were likewise mainly distributed within this range. Overall, these results indicate that C. snyderi occurs within a bottom-water temperature range of approximately 9–16 °C throughout the year, suggesting a clear preference for specific benthic thermal conditions.

Figure 3.

Seasonal sea surface temperature and sampling locations of the crocodile toothfish, Champsodon snyderi, in the South Sea of Korea in 2021. Colored contours indicate sea surface temperature (°C) based on data provided by KODC, while blue circles indicate the sampling stations where C. snyderi specimens were collected during seasonal bottom-trawl surveys conducted in February, May, August, and November.

3.2. TL Distribution

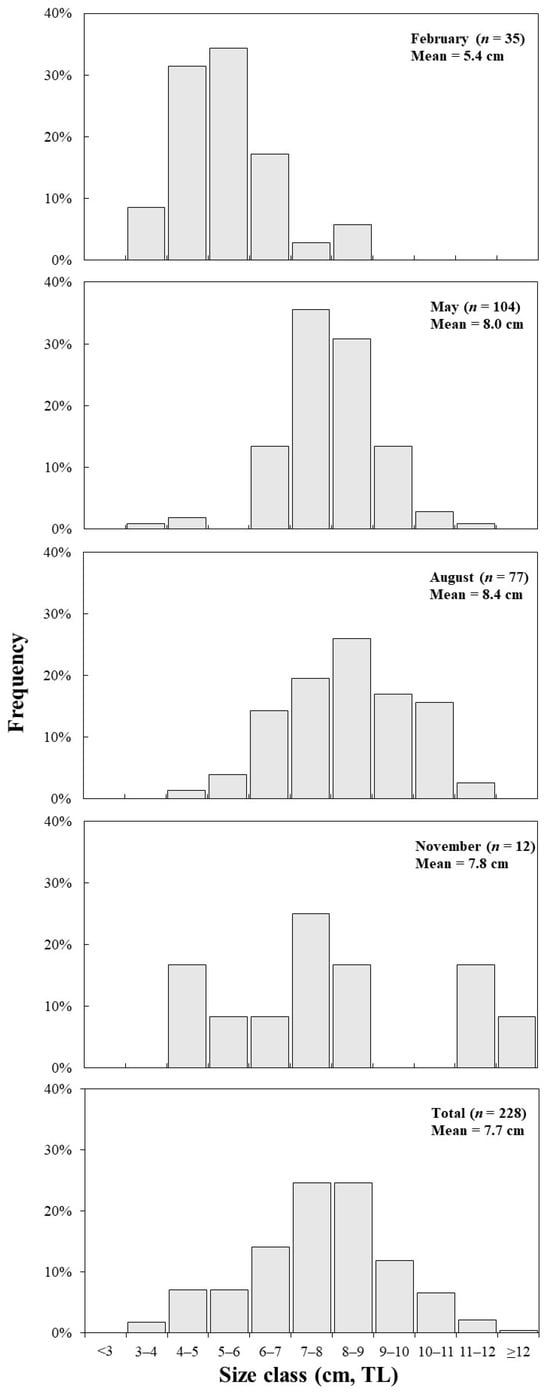

Figure 4 shows the monthly TL distribution of C. snyderi. The results reveal that in February, TLs ranged from 3.6 cm to 8.9 cm, with a mean TL of 5.4 cm. In May, the range extended from 3.6 cm to 11.0 cm, with the mean value increasing to 8.0 cm. In August, TL ranged from 4 cm to 11.7 cm, with the highest mean TL recorded at 8.4 cm, whereas in November, lengths ranged from 4.2 cm to 12.3 cm, with the mean decreasing slightly to 7.8 cm. These monthly variations in TL suggest that relatively larger individuals tend to occur more frequently in May and August, when water temperatures are elevated. A total of 228 specimens were analyzed, with TLs ranging from 3.6 cm to 12.3 cm. Among them, individuals in the 7.0–8.0 cm and 8.0–9.0 cm size ranges each accounted for 24.6% of the total, representing the highest occurrence rates. Analysis of the monthly total length (TL) of C. snyderi revealed that the TL differed significantly among months (one-way ANOVA, p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Length-frequency distribution of the crocodile toothfish, Champsodon snyderi, collected from offshore waters of the South Sea of Korea in February, May, August, and November, as along with the overall Distribution. TL, Total length.

3.3. Diet Composition and Trophic Level

The stomach content analysis of C. snyderi specimens revealed that among the 228 individuals examined, 129 contained identifiable prey items (Table 2). The most important prey group was the amphipods (Amphipoda), which accounted for 66.7% of the occurrence frequency, 64.1% of the numerical proportion, and 13.7% of the weight proportion, resulting in an IRI of 58.2%. Among the amphipods, Themisto (Themisto sp.) were dominant. The second most important prey group was the carideans (Caridea), which accounted for 36.5% of the total IRI. Other prey groups, including euphausiids (Euphausiacea), fish (Pisces), cephalopods (Cephalopoda), and mysids (Mysidacea), were also recorded; however, each accounted for <4.9% of IRI. The mean trophic level of C. snyderi, calculated to evaluate its ecological position, was estimated to be 3.47.

Table 2.

Feeding characteristics of the crocodile toothfish, Champsodon snyderi, collected from the offshore waters of the South Sea of Korea, showing frequency of occurrence (%F), numerical composition (%N), wet weight (%W), and percentage index of relative importance (%IRI).

3.4. Size-Class Differences in Diet Composition

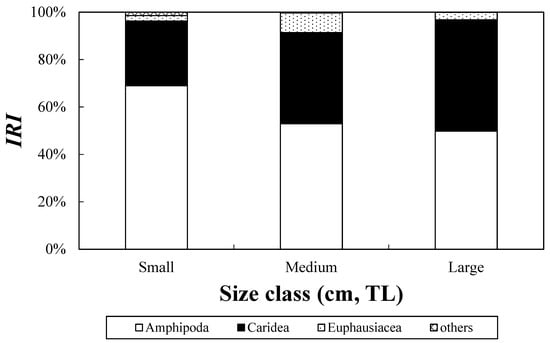

The size-based analysis of the diet composition of C. snyderi (Figure 5) revealed that amphipods dominated the small-sized group, contributing to the highest %IRI (69.0%), followed by carideans (27.3%). Similarly, amphipods were dominant in the mid-sized group at 52.9%, with carideans accounting for 38.4% of the total. In the large group, amphipods and carideans contributed similar proportions of 49.8% and 47.0%, respectively. Overall, no distinct dietary shifts were observed among the size classes, although the proportion of amphipods tended to decrease with growth, whereas the proportion of carideans showed an increasing trend.

Figure 5.

Size class differences in the feeding characteristics of the crocodile toothfish, Champsodon snyderi, collected from the offshore waters of the South Sea of Korea, based on %IRI values across size classes (small-size class: <8.0 cm; medium-size class: 8–9 cm; large-size class: ≥9.0 cm).

3.5. Seasonal Variation in Diet Composition

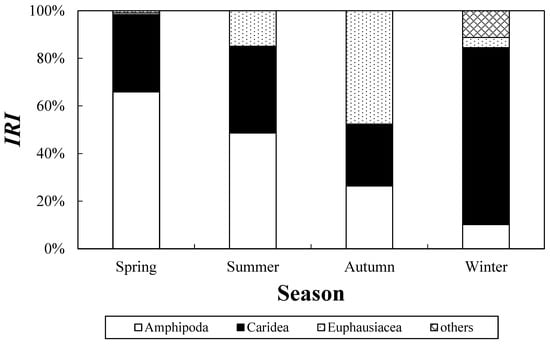

Seasonal trends in the diet of C. snyderi (Figure 6) indicated that carideans were the predominant prey group in spring (%IRI = 74.4%), followed by amphipods (10.1%). In summer, amphipods accounted for the highest proportion (65.9%), while carideans accounted for 32.5%. In autumn, amphipods and carideans represented 48.7% and 36.4% of the %IRI, respectively. In winter, euphausiids constituted the largest proportion of the diet, contributing 47.6% to the %IRI. These results indicate that the dominant prey groups of C. snyderi vary markedly with season.

Figure 6.

Seasonal variation in the feeding characteristics of the crocodile toothfish, Champsodon snyderi, collected from the offshore waters of the South Sea of Korea, based on %IRI values for spring (May), summer (August), autumn (November), and winter (February).

3.6. Analysis of Feeding Patterns Based on Size Class and Season

A statistical analysis of the feeding relationships of C. snyderi by season and size class using a two-way PERMANOVA (Table 3) showed that prey composition did not differ significantly by season (p = 0.611) or size class (p = 0.073) (p > 0.05). However, a significant difference was detected in the interaction effect between these two factors (p = 0.02) (p < 0.05). The differences in the prey composition according to season and size class using CAP are shown in Figure 7. In the large-size class, amphipods were predominant during summer, whereas a shift toward fish prey was observed in autumn. Copepods and euphausiids were the main contributors to small- and medium-sized classes during spring and winter. These findings indicate that the dominant prey of C. snyderi varies depending on the season and growth stage.

Table 3.

Degrees of freedom (df), sum of squares (SS), mean squares (MS), pseudo-F statistics, and p-values from PERMANOVA tests examining differences in feeding characteristics by season and size class in the offshore waters of the South Sea of Korea.

Figure 7.

CAP ordination showing seasonal and size-class variation in the feeding characteristics of the crocodile toothfish, Champsodon snyderi, collected from the offshore waters of the South Sea of Korea.

4. Discussion

The analysis of demersal water temperature measured at the sampling sites, showed that C. snyderi appeared within a relatively limited range of demersal water temperatures (approximately 9–16 °C) throughout the year, with particularly high occurrences observed in May and August. This suggests that this species prefers specific demersal temperature conditions rather than being widely distributed across a broad temperature range. Temperature is a metabolic regulatory factor that directly influences all physiological and metabolic responses in fish and is one of the most important environmental factors for their survival and growth [27]. As the demersal water temperature rises, conditions that increase metabolic activity and activity levels can form, and these may affect the habitat use and occurrence patterns of demersal fish. These demersal temperature conditions likely favor the activity and habitat use of C. snyderi, contributing to the high occurrence patterns observed in May and August in this study.

The feeding analysis of C. snyderi revealed that amphipods were its primary prey group, with Themisto sp. identified as the most important. Amphipods are distributed across a wide range of marine environments, including coastal waters, continental shelves, estuaries, and deep-sea habitats, and they can survive over a broad temperature range from tropical to temperate and polar regions. They also account for a high proportion of both abundance and biomass in marine ecosystems and play a key role in linking food webs as important food sources for various marine predators, such as whales, fish, and seabirds [28,29,30,31,32]. The South Sea of Korea provides particularly favorable conditions for amphipods because of its soft-bottom environment [33]. A previous survey identified 26 amphipod species and reported the occurrence of the planktonic amphipod Themisto sp. at the same locations where C. snyderi was collected in the present study [34]. This indicates that Themisto sp. are abundantly distributed in the South Sea and that this region functions as an important feeding ground, providing key prey resources for C. snyderi. We identified the caridean shrimp Leptochela sydniensis as the second most important prey. This observation is consistent with the findings of a previous study conducted in the South Sea, which reported that L. sydniensis was the primary prey item of small-scale gurnards (Lepidotrigla microptera) [35]. Another study identified L. sydniensis as the most dominant species among pelagic shrimps found in the South Sea and reported that it consistently maintained high population densities in this region [36]. However, a study conducted in Japan reported that the primary prey items of C. snyderi include crustaceans, particularly gammaridean amphipods, carideans, and penaeidean shrimps (Plesionika grandis and Metapenaeopsis philippii), which differs from the results of the present study [6]. This discrepancy is likely because a previous study reported that C. snyderi primarily consumes benthic prey, suggesting that the species leaves the seafloor only when hunting fish [37]. There are two possible pathways through which amphipods may be present in the stomach contents of C. snyderi. First, they may have been included indirectly through secondary predation, where C. snyderi fed on small fish that consumed amphipods. Second, C. snyderi may have directly preyed on Themisto sp. in the pelagic zone during its nocturnal vertical migration. C. snyderi typically leaves the bottom during feeding and undertakes nocturnal vertical movement toward surface waters [6,38]. Themisto sp., being planktonic, medium- to large-sized zooplankton, are likely targeted during the nocturnal vertical migration of C. snyderi, which serves as a feeding strategy. The alignment between the behavioral ecology of C. snyderi and the spatial distribution of Themisto sp. suggests that this amphipod can function as a major prey source for this species [32].

The trophic level is used to estimate ecological position, and it generally ranges from 2.0–5.0. Values close to 2.0 are representative of herbivores or detritivores, whereas those near 5.0 are representative of carnivores or piscivores [39,40]. In the present study, the trophic level of C. snyderi was calculated as 3.47, which corresponds to that of a mesopredator. The trophic levels of A. japonicum and A. kagoshimae in the South Sea have been reported as 3.34 and 3.22, respectively, indicating that they occupy a similar ecological niche to C. snyderi [8,9]. Higher-level consumers such as Scomber japonicus and Trachurus japonicus exhibit trophic levels of 3.92–4.0 and 3.79, respectively [41,42,43]. These findings suggest that C. snyderi, as a predatory fish feeding primarily on medium- to large-sized planktonic amphipods, such as Themisto sp., plays an important role as an ecological mediator linking energy flow between lower- and higher-level predators.

As fish grow, their feeding ability gradually improves and the variety of prey items they consume tends to increase. Furthermore, changes in morphological and ecological traits maximize energy efficiency, leading to a preference for prey at relatively high trophic levels [44]. In the present study, the proportion of amphipods in the stomach contents of C. snyderi decreased with an increase in its growth (small: <8.0 cm, medium: 8–9 cm), while the proportion of carideans and fishes increased (large: ≥9.0 cm). The change in diet composition by size class exhibited a gradual shift rather than an abrupt dietary switch, with larger individuals exhibiting a relatively higher proportion of carideans in their diet. This trend has also been observed in other fish species that feed primarily on zooplankton and small pelagic or mesopelagic crustaceans [9,45,46]. Additionally, Morohoshi and Sasaki reported that individuals with TL ranging from ≤2.9 cm to 4.9 cm primarily consumed gammaridean amphipods, whereas individuals ≥ 5.0 cm fed mainly on crustaceans and the small fish Bregmaceros nectabanus [6]. Considering the findings of the present study in light of previous studies, we infer that as C. snyderi grows, its primary prey resources gradually shift from crustaceans (amphipods and carideans) to small fish, which is accompanied by an increase in dietary diversity.

The analysis of the seasonal diet composition revealed that in spring and summer, the proportion of amphipods in the diet was relatively high, with Themisto sp. identified as a primary prey item. Amphipods occur abundantly from May to July, when water temperatures rise, and their abundance tends to increase during spring and summer. In contrast, previous studies have reported that amphipod occurrence is lowest in winter, which is consistent with the seasonal trends observed in this study [47,48,49]. These results suggest that amphipods function as a major food resource for C. snyderi during spring and summer. Autumn diets were largely characterized by a high contribution of euphausiids. These organisms tend to exhibit higher abundance and species diversity in autumn, with both larval and adult stages often dominant during this season [50]. Similarly, Lee reported high euphausiid densities in autumn [51]. Winter diets were characterized by an elevated proportion of carideans. A study conducted in the waters surrounding the South Sea of Korea reported that the number of carideans caught in winter was significantly higher than that in other seasons, whereas their occurrence rate decreased in autumn, which is consistent with the findings of this study [52].

Overall, these results suggest that C. snyderi adjusts its feeding strategy in response to seasonal variation in prey availability. In addition, the observed seasonal variations in diet are likely associated with differences in the ecological roles and energy demands of the major prey groups. Euphausiids function as key energy transfer agents in marine ecosystems, linking primary producers to higher trophic levels, whereas amphipods are important functional groups in marine benthic food webs, contributing to biodiversity maintenance and energy transfer across trophic levels, and serving as major prey for fishes and other higher trophic level predators [53,54]. In contrast, carideans (shrimp) represent relatively large, energy-rich, demersal prey that are utilized by a wide range of fish because of their high nutritional value [55]. Taken together, the increased consumption of amphipods in spring and summer, euphausiids in autumn, and carideans in winter reflect not only seasonal changes in prey availability but also seasonal shifts in energetic demand and differences in prey accessibility. Although differences in stock structure or life history stages may influence seasonal dietary patterns, such information remains largely unknown for C. snyderi. Furthermore, because quantitative data on the prey community composition in fishing areas are not available, these patterns should be interpreted as reflecting an opportunistic feeding strategy rather than selective prey choice. Therefore, these results suggest that C. snyderi functions as a mesopredator that flexibly adjusts its feeding strategy in response to seasonal changes in prey composition and energy demand, reflecting opportunistic feeding behavior.

Through an analysis of its feeding ecology, the findings of the present study enhance our understanding of the ecological role of C. snyderi in the South Sea of Korea, thereby providing baseline data for future sustainable fishery resource management and ecosystem-based assessments. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in Korea to estimate the trophic level of C. snyderi through conducting a stomach content analysis, and the results demonstrate that this species functions as a mesoprediter in benthic ecosystems. However, research on the feeding ecology of C. snyderi in Korean waters is limited. Even in this study, differences in the occurrence periods and feasibility of sample collection were observed depending on the sea temperature distribution. This finding suggests that systematic and well-planned sampling that considers oceanographic factors such as temperature is necessary for conducting seasonal feeding ecology analyses. Continued expansion of knowledge on the ecological function of C. snyderi could serve as valuable baseline information for understanding predator–prey relationships and energy flow within benthic ecosystems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.S.P. and H.J.K.; methodology, H.S.P.; software, H.S.P.; validation, H.J.K. and G.W.B.; formal analysis, H.S.P.; investigation, H.S.P.; resources, J.M.J.; data curation, H.S.P.; writing—original draft preparation, H.S.P.; writing—review and editing, H.J.K., G.W.B. and J.M.J.; visualization, H.S.P.; supervision, J.M.J.; project administration, J.M.J.; funding acquisition, G.W.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Institute of Fisheries Science (NIFS), Republic of Korea (grant number R2026001).

Data Availability Statement

The oceanic environmental data used in this study were published by the Korea Ocean Data Center (KODC), and can be accessed at https://www.nifs.go.kr/kodc/eng/index.kodc (accessed on 30 June 2025).

Acknowledgments

We thank the reviewers and editors for their thoughtful reviews of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TL | total length |

| BW | body weight |

| %F | frequency of occurrence |

| %N | numerical percentage |

| %W | weight percentage |

| IRI | index of relative importance |

| CAP | canonical analysis of principal coordinates |

| PERMANOVA | permutational multivariate analysis of variance |

| KODC | Korea Oceanographic Data Center |

References

- Shephard, S.; Reid, D.G.; Greenstreet, S.P.R. Interpreting the large fish indicator for the Celtic Sea. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2011, 68, 1963–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, D. Systematics and distribution of fishes of the family Champsodontidae (Teleostei: Perciformes), with descriptions of three new species. Copeia 1994, 2, 347–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ma, L.; Sun, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H. Spatial variation of demersal fish diversity and distribution in the East China Sea: Impact of the bottom branches of the Kuroshio Current. J. Sea Res. 2019, 144, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, W. Champsodontidae—Gapers. In The Larvae of Indo-Pacific Shorefishes; Leis, J.M., Trnski, T., Eds.; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 1989; pp. 245–258. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, J.M.; Kim, S.; Lee, E.K.; Kim, Y.U. Studies on the fish larvae community in the Sea around Cheju Island in November, 1986. J. Oceanol. Soc. Korea 1998, 3, 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Morohoshi, Y.; Sasaki, K. Intensive cannibalism and feeding on bregmacerotids in Champsodon snyderi (Champsodontidae): Evidence for pelagic predation. Ichthyol. Res. 2003, 50, 387–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Deng, Y.; Qin, J.; Luo, K.; Kang, B.; He, X.; Yan, Y. Dietary shifts in the adaptation to changing marine resources: Insights from a decadal study on greater lizardfish (Saurida tumbil) in the Beibu Gulf, South China Sea. Animal 2024, 14, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, J.H.; Kim, D.G.; Kang, D.Y.; Kang, S.K.; Jeong, J.M.; Baeck, G.W. Feeding habits of the Glowbelly Acropoma japonicum in the South Sea of Korea. Korean J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2022, 55, 374–378. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, J.M.; Lee, S.J.; Baeck, G.W. Feeding ecology of smallmouth Argentine Argentina kagoshimae in coastal waters of the South Sea, Korea. Korean J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2022, 55, 590–597. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, W.P. The role of disturbance in natural communities. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1984, 15, 353–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillebrand, H. On the generality of the latitudinal diversity gradient. Am. Nat. 2004, 163, 192–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunday, J.M.; Bates, A.E.; Dulvy, N.K. Thermal tolerance and the global redistribution of animals. Nat. Clim. Change 2012, 2, 686–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A.H.; Marzinelli, E.M.; Vergés, A.; Coleman, M.A.; Steinberg, P.D. Towards restoration of missing underwater forests. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e84106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinsky, M.L.; Selden, R.L.; Kitchel, Z.J. Climate-driven shifts in marine species ranges: Scaling from organisms to communities. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2020, 12, 153–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cheng, J. Analysis of the interrelation and seasonal variation characteristics of the spatial niche of dominant fishery species—A case study of the East China Sea. Biology 2024, 13, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, K.D.; Jin, H.W.; Lu, Z.H.; Pan, G.L.; Zhu, Z.J. Preliminary study on feeding ecology of Champsodon snyderi in the East China Sea region. Marine Sci. 2012, 36, 79–88, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Froese, R.; Pauly, D. (Eds.) FishBase. World Wide Web Electronic Publication. Available online: https://www.fishbase.org (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Gauzens, B.; Rosenbaum, B.; Kalinkat, G.; Boy, T.; Jochum, M.; Kortsch, S.; O’Gorman, E.J.; Brose, U. Flexible foraging behavior increases predator vulnerability to climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2024, 14, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaname, O. New Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Fauna of Japan; Hokuryu-Kan Publishing Co., Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 1988; pp. 1–803. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.Y. Marine Invertebrates in Korean Coasts; Academy Publishing Company: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2006; pp. 1–479. [Google Scholar]

- Hyslop, E.J. Stomach contents analysis: A review of methods and their application. J. Fish. Biol. 1980, 17, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkas, L.; Oliphant, M.S.; Iverson, I.L.K. Food Habits of Albacore, Bluefin Tuna, and Bonito in California Waters. Fish Bulletin 152 1970, 1–105. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7t5868rd (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Cortés, E. Standardized diet compositions and trophic levels of sharks. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 1999, 56, 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauly, D.; Trites, A.W.; Capuli, E.; Christensen, V. Diet composition and trophic levels of marine mammals. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 1998, 55, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, D.A.; Bizzarro, J.J. Standardized diet compositions and trophic levels of skates (Chondrichthyes: Rajiformes: Rajoidei). Environ. Biol. Fish. 2007, 80, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.J.; Gorley, R.N.; Clarke, K.R. PERMANOVA + for PRIMER: Guide to Software and Statistical Methods; PRIMER-E: Plymouth, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brett, J.R.; Groves, T.D.D. Physiological energetics. Fish Physiol. 1979, 8, 279–352. [Google Scholar]

- Budnikova, L.L.; Blokhin, S.A. Food contents of the eastern gray whale Eschrichtius robustus Lilljeborg, 1861 in the Mechigmensky bay of the Bering Sea. Russ. J. Mar. Biol. 2012, 38, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padovani, L.N.; Viñas, M.D.; Sánchez, F.; Mianzan, H. Amphipod-supported food web: Themisto gaudichaudii, a key food resource for fishes in the Southern Patagonian Shelf. J. Sea Res. 2012, 67, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, A.L.; Demchenko, N.L.; Aerts, L.A.M.; Yazvenko, S.B.; Ivin, V.V.; Shcherbakov, I.; Melton, H.R. Prey biomass dynamics in gray whale feeding areas adjacent to Northeastern Sakhalin (the Sea of Okhotsk), Russia, 2001–2015. Mar. Environ. Res. 2019, 145, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, E.A.; Brodeur, R.D.; Morgan, C.A.; Burke, B.J.; Huff, D.D. Prey selectivity and diet partitioning of juvenile salmon in coastal waters in relation to prey biomass and implications for salmon early marine survival. Nor. Pac. Anadromous Fish Comm. Tech. Rep. 2021, 17, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havermans, C.; Auel, H.; Hagen, W.; Held, C.; Ensor, N.S.; Tarling, G.A. Chapter Two-Predatory zooplankton on the move: Themisto amphipods in high-latitude marine pelagic food webs. Adv. Mar. Biol. 2019, 82, 51–92. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, J.Y.; Choi, J.W. The macrozoobenthic community at the expected sand excavation area in the Southern continental shelf of Korea. J. Korean Soc. Oceanogr. 2010, 15, 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.W.; Choi, J.H.; Shin, S.Y.; Kim, J.; Kim, Y.H. Amphipod (Crustacea: Malacostraca) fauna of the continental shelf region in the Southern Sea of Korea. J. Species Res. 2024, 13, 159–177. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, C.H.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, J.H.; Baeck, G.W. Diet composition and trophic level of bluefin searobin, Chelidonichthys spinosusin in the South Sea of Korea. J. Korean Soc. Fish. Ocean Technol. 2024, 60, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, W.G.; Ma, C.W.; Hong, S.Y.; Lee, K.W. Distribution and abundance of planktonic shrimps in the southern sea of Korea during 1987–1991. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2009, 12, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusca, R.C.; Brusca, G.J. Invertebrates; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.L.B. The Sea Fishes of Southern Africa; Central News Agency: Cape Town, South Africa, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Pauly, D.; Christensen, V.; Dalsgaard, J.; Froese, R.; Torres, F. Fishing down marine food webs. Science 1998, 279, 860–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauly, D.; Palomares, M.L. Approaches for dealing with three sources of bias when studying the fishing down marine food web phenomenon. In Fishing Down the Mediterranean Food Webs? Durand, F., Ed.; CIESM Workshop Series 12; CIESM: La Condamine, Monaco, 2000; pp. 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.G.; Seong, G.C.; Jin, S.Y.; Soh, H.Y.; Baeck, G.W. Diet composition and trophic level of jack mackerel, Trachurus japonicus, in the South Sea of Korea. J. Korean Soc. Fish. Ocean Technol. 2021, 57, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, G.C.; Kim, D.G.; Jin, S.Y.; Soh, H.Y.; Baeck, G.W. Diet composition of the chub mackerel Scomber japonicus in the coastal waters of the South Sea of Korea. Korean J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2021, 54, 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.S.; Song, S.H.; Jeong, J.M.; Yang, J.H.; Kim, C.S. Comparison of the feeding characteristics of chub mackerel Scomber japonicus in Jeju Island and the Yellow Sea of Korea. Water 2025, 17, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown-Vuillemin, S.; Barreau, T.; Caraguel, J.M.; Iglésias, S.P. Trophic ecology and ontogenetic diet shift of the blue skate (Dipturus cf. flossada). J. Fish Biol. 2020, 97, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baeck, G.W.; Park, J.M.; Huh, S.H.; Kim, H.J.; Jeong, J.M. Feeding habits of kammal thryssa, Thryssa kammalensis (Bleeker, 1849) in the coastal waters of Gadeok-do, Korea. Anim. Cells. Syst. 2014, 18, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, S.H.; Jeong, J.M.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, K.R.; Baeck, G.W. Feeding habits of the pacific herring Clupea pallasii in the coastal waters of the East Sea, Korea. Korean J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2022, 55, 224–228. [Google Scholar]

- Lorz, H.V.; Pearcy, W.G. Distribution of hyperiid amphipods off the Oregon Coast. J. Fish. Res. Board Can. 1975, 32, 1442–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.J.; Yu, O.H.; Suh, H.L. Seasonal variation and feeding habits of amphipods inhabiting Zostera marina beds in Gwangyang Bay, Korea. J. Korean Fish. Soc. 2004, 37, 122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Lavaniegos, B.E.; Hereu, C.M. Seasonal variation in hyperiid amphipods and influence of mesoscale structures off Baja California. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2009, 394, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.A.; Chang, F.H.; Tao, H.H.; Hsieh, C.H. Seasonal variation of euphausiid life stage and taxonomic composition near the upwelling site Northeast of Taiwan. Cont. Shelf Res. 2023, 269, 105–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.R. Distribution of Euphausiids and Population Structure of Euphausia pacifica in Korea Waters. Ph.D. Dissertation, Pukyong National University, Busan, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, Y.I.; Lee, J.H.; Oh, T.Y.; Lee, J.B.; Choi, Y.M.; Lee, D.W. Distribution and seasonal variations of fisheries resources captured by the beam trawl in Namhae Island, Korea. J. Kor. Soc. Fish. Tech. 2013, 49, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauchline, J. The Biology of Mysids and Euphausiids. Advances in Marine Biology; Academic Press: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1980; Volume 18, pp. 1–681. [Google Scholar]

- Dauvin, J.C. Overview of predation by birds, cephalopods, fish and marine mammals on marine benthic amphipods. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, D.T.; Blaber, S.J.M.; Salini, J.P. Predation on penaeid prawns by fishes in Albatross Bay, Gulf of Carpentaria. Mar. Biol. 1991, 109, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.