Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a key indicator of hygienic and operational deficiencies in swimming pools, particularly in tourist facilities with high and variable user loads. This study reports the results of a four-year regulatory surveillance program (2016–2019) assessing P. aeruginosa contamination in tourist swimming pools in Andalusia, Spain. The program involved 14 hotels and 58 unique installations. A total of 2053 water samples collected from different installation types (outdoor and indoor pools, whirlpools, and cold-plunge pools) were analyzed using standardized ISO methods within the framework of Spanish legislation, and prevalence comparisons were based on proportion tests. The overall prevalence of P. aeruginosa was 5.1%, with marked differences among installation types, reflecting both variation in contamination rates and unequal sampling intensity. Whirlpools consistently showed the highest contamination rates, whereas indoor pools and cold-plunge pools exhibited lower prevalence. No significant differences were observed between chlorine- and bromine-treated pools, and contaminated samples were detected across the full range of disinfectant concentrations, including values within regulatory limits. Temporal analysis revealed that apparent seasonal peaks were installation-dependent rather than reflecting a uniform seasonal trend. Winter detections were confined to indoor pools and whirlpools, which remain operational year-round, while outdoor pools and cold-plunge pools were underrepresented during the low season due to reduced sampling. A marked increase in prevalence was observed in 2019, driven mainly by summer months and high-risk installations; however, this rise was not directly associated with tourist volume and does not support causal inference. These findings highlight the importance of installation-specific and operational factors in shaping P. aeruginosa contamination patterns. The study underscores the need for targeted surveillance strategies focusing on high-risk installations and for cautious interpretation of seasonal patterns in datasets derived from routine regulatory monitoring.

1. Introduction

Recreational water environments are an essential component of modern tourism and public health infrastructure. In regions with high tourist influx, swimming pools and spa facilities represent not only leisure amenities but also complex aquatic systems that require rigorous management to ensure user safety [1,2,3]. Proper maintenance of these systems is critical, as inadequate operation may lead to microbial proliferation, biofilm formation, and increased exposure to opportunistic pathogens [4]. Over the last two decades, several studies across Europe, North America and Australia have highlighted that swimming pool contamination remains a recurring issue, despite advances in disinfection technologies and increasingly stringent regulations [5,6,7,8].

Among the microorganisms of greatest concern in recreational waters, P. aeruginosa occupies a particularly relevant place. This Gram-negative opportunistic pathogen is well known for its ability to colonize aquatic environments, resist disinfection, and persist within biofilms in hydraulic systems and wet surfaces [9]. In addition to its environmental resilience, P. aeruginosa is a major clinical concern due to its intrinsic antimicrobial resistance and prevalence in healthcare-associated infections, which has led to its inclusion in international priority lists for surveillance and research [10,11,12]. Although infections acquired in swimming pools are relatively uncommon, they may include otitis externa, dermatitis, keratitis, hot-foot syndrome, or, in exceptional cases, more severe systemic disease [13,14,15,16]. For this reason, many countries include P. aeruginosa as a microbiological parameter in routine pool monitoring programs.

Tourist swimming pools, particularly those located in warm regions with high seasonal occupancy, may be especially prone to contamination. Factors such as user density, organic load, elevated water temperature, suboptimal hydraulic design, and insufficient mechanical cleaning are widely recognized contributors to increased microbial risk. Previous surveillance studies conducted in tourist swimming pools across different European regions have consistently reported the presence of P. aeruginosa, although with variable prevalence depending on installation type, regulatory context, and sampling design. In Spanish island regions with high tourism pressure, such as the Balearic and Canary Islands, reported prevalence values typically range between approximately 4% and 15%, with higher rates frequently observed in whirlpools and spa facilities [17,18]. Comparable surveys in other European countries have reported prevalence values ranging from below 5% in standard swimming pools to over 50% in high-risk installations such as whirlpools, highlighting the strong influence of installation characteristics and operational conditions [7,19,20,21].

Southern Spain, and particularly Andalusia, represents a highly relevant setting to investigate microbiological safety in tourist swimming pools. Andalusia is one of the most visited tourist regions in Europe, hosting tens of millions of visitors annually, with a high density of hotel-based aquatic installations that operate under intense and seasonally variable user loads. This combination of large-scale tourism, extensive pool infrastructure, and pronounced seasonal dynamics makes Andalusia a representative case study for evaluating operational and hygienic challenges in tourist swimming pools under real-world conditions. Despite the abundant literature on swimming pools, no studies have focused specifically on this region. Moreover, international research has tended to emphasize free chlorine systems, leaving bromine-treated pools comparatively understudied, despite their relevance in spa settings and high-temperature installations. Additional uncertainty persists regarding the influence of user demographics (e.g., children), environmental seasonality, and the ability of disinfectant levels to predict P. aeruginosa contamination under real-world conditions. Addressing these gaps is essential for improving surveillance frameworks and guiding targeted interventions.

The present study provides a four-year assessment of the microbiological quality of tourist swimming pools in Andalusia, Spain, with a particular focus on P. aeruginosa. Building upon prior surveillance efforts in other Spanish regions, this work offers new insights into contamination patterns across different installation types, seasonal trends, and the comparative performance of chlorine and bromine disinfection. By integrating these findings, the study aims to contribute to a deeper understanding of the operational factors influencing P. aeruginosa persistence and to support evidence-based improvements in the management of recreational waters in high-occupancy tourist environments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Surveillance Framework

A four-year surveillance study was conducted between 2016 and 2019 to assess the microbiological and physicochemical quality of recreational waters in tourist swimming pool installations located in Andalusia, southern Spain. All sampled facilities were hotel-based pools catering to tourists and subject to routine inspections under the regional surveillance program for compliance with Spanish national legislation [22] on swimming pool water quality.

The surveillance covered 14 hotel facilities comprising 58 distinct pool installations (basins): outdoor pools (n = 38), indoor pools (n = 8), whirlpools (n = 11), and one cold-plunge pool (n = 1). An “installation” was defined a priori as a unique basin operated and monitored independently within each hotel. Selection followed the routine regulatory program; visit frequency varied seasonally with facility operation (see Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 for monthly/yearly sampling counts).

This study was based on routine regulatory surveillance, which provides high real-world relevance but results in uneven sampling across pool types and seasons. In particular, outdoor pools and cold-plunge pools were underrepresented during winter months due to seasonal closure of these installations. This limitation was considered in the interpretation of temporal patterns and is explicitly addressed in the Results and Discussion sections.

2.2. Sampling Strategy

A total of 2053 water samples were collected from the main pool basins following the standardized procedures defined in Royal Decree 742/2013 and ISO 19458:2007 guidelines [22]. However, sampling frequency varied by installation type depending on operational schedules (see Supplementary Table S1 for monthly counts by installation). Sampling points were selected to ensure representative coverage of each installation and included outdoor pools, indoor pools, whirlpools (spas, jacuzzis), and cold-plunge pools.

Samples were obtained using 250 mL sterile containers with sodium thiosulfate (Sharlab, Barcelona, Spain) (for dichlorination) and were transported to the laboratory under refrigerated conditions for analysis within 24 h.

All microbiological and physicochemical analyses were performed exclusively on water samples collected from the pool basin at representative points, in accordance with regulatory protocols. No samples were taken from filters, balance tanks, pipework, surfaces, biofilms, or recirculation systems. This constitutes an important limitation of the study, as contamination sources located within the hydraulic system or on pool surfaces may not be detected through basin water sampling alone.

2.3. Microbiological Analysis

The detection of P. aeruginosa was performed according to ISO 16266-2:2018, by using the Pseudalert® system (IDEXX Laboratories, Westbrook, ME, USA) as a standardized method validated for recreational waters [23,24]. For the purposes of regulatory compliance and statistical analysis, results were treated as qualitative (presence/absence), in line with Spanish legislation, which establishes a zero-tolerance criterion for P. aeruginosa in swimming pool water. Quantitative results were therefore not further analyzed. Briefly, 100 mL of each sample were mixed with the Pseudalert® reagent and incubated at 38 ± 0.5 °C for 24–28 h. Fluorescence under UV light was considered positive for P. aeruginosa. As for E. coli analyses, they were performed using Colilert®-18 (IDEXX Laboratories), following manufacturer instructions and ISO 9308-2 standards [25]. Positive (water contaminated with P. aeruginosa and E. coli) and negative controls (sterile water) were processed in parallel throughout the study. Confirmatory testing by culture or molecular methods was not routinely performed, as the Pseudalert® method is validated for regulatory surveillance and widely used by public health laboratories for compliance monitoring.

2.4. Physicochemical Parameters

During each sampling event, free chlorine and combined chlorine or bromine (where applicable), pH, turbidity and temperature were measured in situ using portable digital meters calibrated daily according to the manufacturer’s specifications [26]. We used a Testo 104 thermometer (Testo, Barcelona, Spain) to determine the temperature in water temperature-controlled installations such as indoor swimming pools, whirlpools, and cold-plunge pools. We used the Lovibond® portable MD100 instrument (Lovibond, Dortmund, Germany) to determine disinfectant levels as well as cyanuric acid levels using the colorimetric method. The pH was also determined by the colorimetric method using the same instrument. The Hanna HI93703 turbidimeter was used for turbidity determination. Ten mL of sample were used in all cases. Measurements were performed simultaneously with microbiological sampling to enable correlation analyses between disinfectant levels, physicochemical conditions, and the presence of P. aeruginosa.

2.5. Compliance with National Standards

According to Royal Decree 742/2013 [27], microbiological parameters such as P. aeruginosa and Escherichia coli were treated as alert/closure criteria, whereas physicochemical variables (e.g., disinfectant residuals, pH, temperature) were considered operational parameters. Microbiological outcomes were analyzed as categorical variables (presence/absence), while physicochemical parameters were treated as continuous variables.

Samples exceeding the parametric values (see Table 1 in results section) were classified as non-compliant. Pools showing microbiological contamination or serious physicochemical deviations were subject to corrective actions or temporary closure by the corresponding facility manager or health authority.

2.6. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize compliance rates and prevalence of P. aeruginosa. According to Royal Decree 742/2013, microbiological parameters (P. aeruginosa and Escherichia coli) were treated as categorical variables (presence/absence), while physicochemical parameters (e.g., disinfectant residuals, pH, temperature) were analyzed as continuous variables. The D’Agostino–Pearson normality test was applied to assess the normal distribution of quantitative parameters. As most parameters showed non-normal distributions, non-parametric methods were applied. The Mann–Whitney test was used to compare continuous variables between contaminated and non-contaminated samples, while Fisher’s exact test was employed for comparisons involving categorical variables, including differences in prevalence among pool types and disinfection systems.

Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. No correction for multiple testing was applied, as analyses were exploratory and focused on predefined, regulatory-relevant comparisons rather than hypothesis-generating screening. Effect size measures (e.g., risk ratios) were not calculated, given the qualitative nature of the primary microbiological outcome and the non-randomized design of the surveillance data. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software version 9.4.1.

3. Results

3.1. Overall Compliance

In total, 58 installations across 14 hotels were monitored (outdoor, indoor, whirlpools, and cold-plunge pools), yielding 2053 water samples for regulatory assessment (Table 1 and Table 2; Supplementary Table S3). Out of the 2053 water samples analyzed, 24.8% (95% CI: 22.9–26.6%) did not comply with the quality criteria established in Royal Decree 742/2013. The most frequent causes of non-compliance were insufficient disinfectant concentration, inadequate water temperature, and the presence of P. aeruginosa. In 2.0% of all cases (95% CI: 1.4–2.6%), the deviation was considered severe enough to warrant immediate pool closure.

Table 1.

Compliance with water standards of legislated parameters in the pools investigated.

Table 1.

Compliance with water standards of legislated parameters in the pools investigated.

| Parameter | Parametric Value | Total Samples | Acceptable | Unacceptable | Closure 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Temperature | 24–30 °C 2 | 573 3 | 472 | 82.4 | 101 | 17.6 | 0 | 0.0 |

| pH | 7.2–8 | 2053 | 1946 | 94.8 | 107 | 5.2 | 6 | 0.3 |

| Turbidity | ≤5 | 2053 | 2047 | 99.7 | 6 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Free chlorine | 0.5–2 mg/L | 1837 | 1492 | 81.2 | 345 | 18.8 | 30 | 1.6 |

| Combined chlorine | ≤0.6 mg/L | 1837 | 1796 | 97.8 | 41 | 2.2 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Cyanuric acid | ≤75 mg/L | 1837 | 1827 | 99.5 | 10 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.1 |

| Bromine | 2–5 mg/L | 159 | 131 | 82.4 | 23 | 14.5 | 5 | 3.1 |

| P. aeruginosa | 0 CFU/100 mL | 2053 | 1948 | 94.9 | 105 | 5.1 | 105 | 5.1 |

| E. coli | 0 CFU/100 mL | 2053 | 2038 | 99.3 | 15 | 0.7 | 15 | 0.7 |

| Total | 2053 | 1543 | 75.2 | 510 | 24.8 | 41 | 2.0 | |

Notes: 1 Unacceptable samples with values exceeding the limits established for the pool’s closure due to its dangerousness. Temperature > 40 °C, pH < 6.0 or >9.0; Turbidity > 20; Free chlorine > 5 mg/L; Combined chlorine > 3 mg/L; Cyanuric acid > 150 mg/L; Bromine > 10 mg/L; 2 ≤36 °C for whirlpools. 3 Percentages and totals are computed over the number of valid observations for each parameter. Occasional “not measured/invalid” residuals occurred due to instrument downtime, insufficient sample volume, interferences, out-of-range readings, or incomplete records. These observations were excluded from compliance calculations; therefore, parameter-specific totals (e.g., free chlorine, bromine) may not match the overall number of samples shown in other tables. Temperature was not measured in outdoor pools; Free and combined chlorine were only determined in chlorine-treated pools; bromine was determined in bromine-treated pools.

Table 2.

Contamination by P. aeruginosa in the different types of investigated pools.

Table 2.

Contamination by P. aeruginosa in the different types of investigated pools.

| Type of Installation | Absence | Presence | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Outdoor pools | 1414 | 95.5 | 66 | 4.5 | 1480 | 100 |

| Indoor pools | 162 | 93.6 | 11 | 6.4 | 173 | 100 |

| Whirlpools | 304 | 92.1 | 26 | 7.9 | 330 | 100 |

| Cold-plunge pools | 68 | 97.1 | 2 | 2.9 | 70 | 100 |

| Total | 1948 | 94.9 | 105 | 5.1 | 2053 | 100 |

P. aeruginosa was identified as the main cause of closure, highlighting its continued relevance as a public health concern in tourist swimming pools (see Table 1).

3.2. Prevalence of P. aeruginosa

P. aeruginosa was detected in 5.1% of all samples analyzed. This prevalence was comparable to those reported in other Spanish regions and Mediterranean countries. The observed rate was lower than previously reported for the Balearic Islands and Greece [17,20,28] but similar to values found in the Canary Islands, Croatia, Finland and Italy [7,18,19,29] (Table 2).

Contamination was not uniformly distributed among pool types. When comparing P. aeruginosa prevalence across installation types, the overall association did not reach statistical significance (χ2 test, p = 0.0505). Pairwise Fisher’s exact tests revealed a significantly higher prevalence in whirlpools compared with outdoor pools (p = 0.0175), whereas no significant differences were observed between other installation pairs. The highest prevalence was observed in whirlpools, where P. aeruginosa was detected in 7.9% of samples, followed by indoor pools (6.4%), outdoor pools (4.5%), and cold-plunge pools (2.9%).

The elevated contamination in whirlpools is consistent with their warmer temperatures, higher organic load, and frequent user turnover, conditions that favor bacterial growth and biofilm formation [17,21].

3.3. Influence of Pool Use by Children

The potential influence of pool use by children on P. aeruginosa contamination was also evaluated (Table 3). Although some studies have suggested that young swimmers may increase the organic load and microbiological risk in recreational waters, no statistically significant association was found in this survey between the presence of children and the detection of P. aeruginosa (p > 0.05).

Table 3.

Contamination by P. aeruginosa in water samples from adults and children pools.

This finding indicates that no evidence of an association with user-related factors was observed in this dataset, while operational and installation-related variables showed clearer patterns, reinforcing the importance of maintaining proper disinfection and maintenance protocols across all pool types.

3.4. Disinfection Systems

The study included both chlorine- and bromine-based disinfection systems, providing a broader comparison than most previous surveys (Table 4). P. aeruginosa was detected in pools treated with either disinfectant, with no significant differences in prevalence (Fisher’s exact, p = 0.18). This p-value refers specifically to the comparison of P. aeruginosa prevalence between disinfectant types. In contrast, Figure 1 and Figure 2 present within-disinfectant comparisons of disinfectant concentrations between P. aeruginosa-positive and -negative samples, which were analysed separately using Mann–Whitney tests.

Table 4.

Contamination by P. aeruginosa in water samples with different disinfectant treatments.

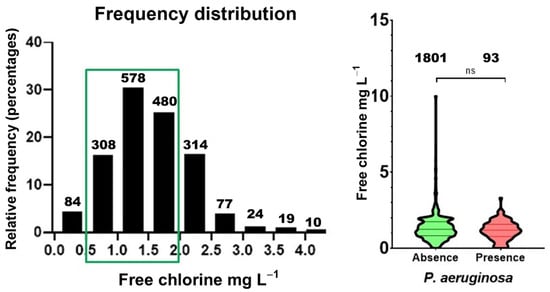

Figure 1.

Frequency distribution of free chlorine levels in P. aeruginosa contaminated and not contaminated pool samples. Left, histogram showing the concentration of free chlorine in ranges of 0.5 mg/L. Green frame indicated appropriate values. Right, violin plot representing individual levels of free chlorine in pools contaminated or not with P. aeruginosa. Statistical comparison between contaminated and non-contaminated samples was performed using the Mann–Whitney test (ns, p = 0.1970). The number of samples included in each interval (n) is also indicated.

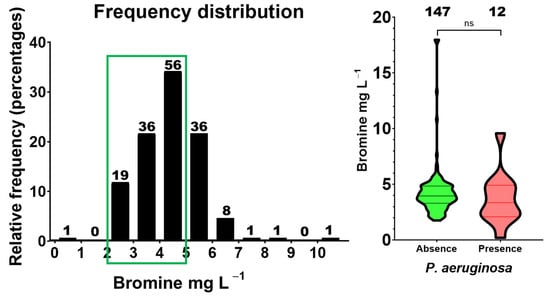

Figure 2.

Frequency distribution of bromine levels in P. aeruginosa contaminated and not contaminated pool samples. Left, histogram showing the concentration of bromine in ranges of 1 mg/L. Green frame indicated appropriate values. Right, violin plot representing individual levels of bromine in pools contaminated or not with P. aeruginosa. Statistical comparison between contaminated and non-contaminated samples was performed using the Mann–Whitney test (ns, p = 0.2653). The number of samples included in each interval (n) is also indicated.

Consistently with these figures, Supplementary Table S4 shows that, among P. aeruginosa-positive samples, residuals occurred both within and below the regulatory ranges for free chlorine (0.5–2.0 mg/L) and bromine (2–5 mg/L), with a smaller number above those ranges. Given small cell sizes in certain installation types, these results are presented as descriptive counts and medians rather than stratified inferential tests, to avoid over-interpretation.

The frequency distribution of free chlorine levels (Figure 1) shows that most samples—both positive and negative—clustered within 0.5–2 mg/L. Nevertheless, a subset of samples exhibited free chlorine < 0.5 mg/L, and these substandard values included several P. aeruginosa-positive cases, indicating insufficient disinfectant residual. Conversely, samples > 2 mg/L were relatively frequent and did not display a clear protective effect against contamination.

A similar pattern was observed in bromine-treated facilities (Figure 2). Most measurements fell within the recommended range (2–5 mg/L), yet P. aeruginosa was detected throughout this interval. Suboptimal bromine concentrations (<2 mg/L) were also observed in a minority of samples and were frequently associated with contamination. Overall, these findings indicate that both disinfectants may fail when residual concentrations fall below regulatory limits, while concentrations within—or even above—the recommended range do not fully guarantee microbiological safety. In the same set of P. aeruginosa-positive samples, pH departures (outside 7.2–8.0) and temperature departures (24–30 °C in outdoor/indoor; ≤36 °C in whirlpools) were infrequent and did not show a consistent pattern by installation type (see Supplementary Table S4).

3.5. Temporal Patterns (Seasonal and Annual Trends)

The monthly distribution of P. aeruginosa contamination revealed a heterogeneous pattern strongly influenced by the type of installation rather than a uniform seasonal trend (Figure 3). Although two apparent peaks were observed in January and August when all pool types were aggregated, the underlying data show that these increases were driven by specific installations. In January, contamination occurred exclusively in whirlpools (1/3 samples, 33%) and indoor pools (1/5 samples, 20%), whereas outdoor pools (0/4 samples) and cold-plunge pools (0 samples collected) showed no detections. This indicates that the “winter peak” does not represent a general increase across all facilities but is instead limited to indoor environments that remain active during the low season. The absence of contamination in outdoor pools and cold-plunge pools in winter reflects not a true zero risk but the reduced or absent sampling of these installations due to seasonal closure.

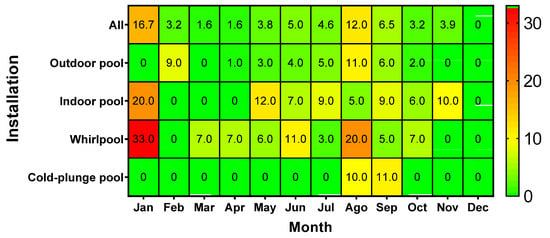

Figure 3.

Heatmap showing the seasonal frequency of P. aeruginosa contamination during the four years. Percentages represent proportion of positive samples per month/type. Values are influenced by sampling density (n) and months with 0% may reflect absence of sampling rather than confirmed absence of contamination (see Supplementary Table S1 for absolute counts).

In contrast, the August peak was broader and involved multiple pool types. Whirlpool contamination reached 9/45 samples (20%), while outdoor pools also showed increased positivity (21/193 samples, 10.9%). Cold-plunge pools showed 1/10 positives (10%), whereas indoor pools exhibited relatively low contamination (1/19 samples, 5.3%). This pattern aligns with the expected effects of high bather load, elevated temperatures, and increased organic input during the peak tourist season.

These results demonstrate that temporal variation is installation-dependent: whirlpools and indoor pools show intermittent contamination throughout the year, while outdoor pools and cold-plunge pools contribute mainly during summer months. Because sampling effort varied considerably across pool types and seasons, percentage-based heatmap patterns should be interpreted with caution, and the inclusion of absolute numbers clarifies that months with “0% contamination” often correspond to very low or absent sampling rather than confirmed absence of P. aeruginosa.

When analyzing yearly prevalence, contamination levels remained relatively stable during the first three years of surveillance (2016–2018), fluctuating around or below 5%. A marked increase was observed in 2019, when the prevalence more than doubled compared with previous years (Table 5). This pattern mirrors similar increases reported in other European regions during the same period and suggests that broader environmental or operational factors may have influenced contamination dynamics in multiple tourist facilities simultaneously [7]. However, analysis of the year-by-year distribution revealed that the marked increase observed in 2019 (11.4%) was not uniformly distributed across months or pool categories. Using the detailed monthly breakdown for 2019 (Supplementary Table S1), most P. aeruginosa detections occurred between June and September, with August (n = 22) and September (n = 14) accounting for more than two-thirds of all positive samples. This indicates that the 2019 increase was driven by a pronounced summer peak rather than a true winter elevation.

Table 5.

Evolution of the contamination by P. aeruginosa over the years. See Supplementary Table S2 for details on the type of installation.

When stratified by installation type (Supplementary Table S2), the rise was primarily attributable to whirlpools (15/78; 19.2%) and outdoor pools (34/346; 9.8%), whereas indoor pools and cold-plunge pools contributed minimally and exhibited very low sample numbers in winter months. Importantly, some installations (particularly cold-plunge pools and outdoor pools) had little or no sampling during the low season, explaining the apparent “winter peak” seen in aggregated heatmaps but not supported by 2019 data. Formal trend testing across years was not applied due to heterogeneous monthly sampling density inherent to regulatory surveillance data.

Overall, the annual increase in 2019 reflects a concentrated surge during the summer months in installation types that inherently present higher risk, rather than a uniform shift across seasons or facilities.

Taken together, these findings highlight that apparent seasonal trends derived from aggregated data may be misleading if sampling density and installation-specific operation are not considered, reinforcing the need for cautious interpretation of percentage-based temporal analyses

4. Discussion

The present study provides one of the most extensive datasets currently available on the microbiological quality of tourist swimming pools in southern Spain, with special emphasis on P. aeruginosa as a key indicator of water safety and operational performance. Overall, the prevalence observed (5.1%) is consistent with values reported in several European regions, supporting the notion that P. aeruginosa remains a persistent and widespread challenge in recreational waters [7,19,28]. In line with previous findings from the Balearic Islands and the Canary Islands, contamination rates in Andalusian tourist facilities followed a similar order of magnitude, reinforcing the idea that Pseudomonas problems in hotels are not region-specific but structurally linked to operational conditions common to most high-occupancy tourist environments [17,18]. Consistent with the regulatory framework, P. aeruginosa was also identified as the leading cause of immediate closures in our series (see Section 3.1 and Table 1).

The differences observed among installation types deserve particular attention. Given the surveillance-based nature of the dataset and unequal sample sizes across installation types, pairwise comparisons were interpreted cautiously. Accordingly, we avoid causal claims based on pairwise contrasts and interpret differences within the operational context of each installation. This framing is consistent with the surveillance design and the unequal sampling by type and season, which further argues for installation-specific rather than system-wide conclusions. As in numerous international studies, whirlpools showed the highest prevalence of contamination [17,21,29,30]. Their combination of elevated water temperature, heavy bather load, high organic input, and the tendency to generate air–water mixing creates optimal conditions for bacterial proliferation and biofilm formation [31]. Conversely, cold-water installations, such as cold-plunge pools, exhibited lower contamination levels, which aligns with the well-known inhibitory effect of lower temperatures on P. aeruginosa growth and persistence.

One of the strengths of the present dataset is the inclusion of both chlorine- and bromine-treated installations, an aspect rarely addressed in comparative surveys. It is important to note that our previous regional studies found a higher prevalence of P. aeruginosa in bromine-treated pools [17,18]. In the current Andalusian series, we did not detect statistically significant differences in prevalence between chlorine and bromine systems (p > 0.05). This apparent discrepancy may be explained by differences in sampling composition, operational routines, monitoring frequency, or seasonal coverage between studies. Bromine systems in tourist settings can present greater variability in residuals due to less standardized dosing or monitoring practices; when poorly managed, this variability could translate into higher contamination risk, as previously observed [17,18]. Therefore, rather than attributing risk to the halogen itself, our combined evidence suggests that operational practices and monitoring quality (dose control, frequency of checks, shock treatments, and attention to hydraulic performance) largely determine the comparative effectiveness of chlorine and bromine in real-world conditions.

The analysis of free disinfectant levels provided additional insights into this relationship. The distribution patterns of free chlorine (and bromine) showed substantial overlap between contaminated and non-contaminated samples, indicating that punctual measurements of residual disinfectant alone cannot fully predict the presence of P. aeruginosa. This observation is consistent with previous literature demonstrating that biofilms, hydraulic dead zones, and protected niches within the system can harbor P. aeruginosa independently of momentary disinfectant levels [31,32]. Therefore, Pseudomonas contamination in pools is not merely a chemical control issue but also a structural and operational one, strongly influenced by system design, maintenance quality, and cleaning frequency [33].

Another relevant finding was the absence of association between P. aeruginosa presence and the use of installations by children. While children are often considered a higher-risk group for fecal contamination and accidental release of organic matter, Pseudomonas is primarily an environmental organism with strong affinity for surfaces, biofilms, and water systems. Several international studies have similarly concluded that contamination is driven far more by system conditions than by demography of pool users [17,18]. The present results reinforce this idea and highlight that preventive measures should prioritize hydraulic optimization and routine maintenance rather than user-related restrictions.

The temporal distribution of contamination also deserves comment. The temporal patterns observed in this study reveal that P. aeruginosa contamination in tourist pools does not follow a uniform seasonal trend but is strongly shaped by the type of installation and by sampling intensity. Although the aggregated heatmap suggested peaks in January and August, the underlying data show that the winter increase was restricted almost exclusively to whirlpools and indoor pools—facilities that remain active during the low season [34]. Outdoor pools and cold-plunge pools showed no detections in winter, but this reflected the absence or very low number of samples rather than a true reduction in risk. This underscores the importance of interpreting seasonal percentages considering the absolute number of samples collected per installation type. In contrast, the August peak represents a genuine seasonal increase, supported by large sample numbers across multiple pool types. Higher contamination in whirlpools and outdoor pools aligns with expected risk factors during peak tourist months, such as elevated temperatures, increased bather load, and higher organic input. Similar summer-associated increases have been documented in other regions [7,33,35,36].

Beyond monthly variation, the annual evolution of prevalence provides additional insight into contamination dynamics. Tourist arrivals in Andalusia increased steadily throughout the study period, from approximately 28.2 million in 2016 to 29.8 million in 2017, 30.6 million in 2018, and 32.5 million in 2019 [37]. Despite this continuous rise in visitor numbers, contamination levels remained relatively stable between 2016 and 2018 and increased markedly only in 2019. Notably, the years with higher tourist influx (2017–2018) were not associated with increased prevalence, indicating that contamination cannot be directly attributed to tourism pressure alone. Furthermore, the increase observed in 2019 was not evenly distributed throughout the year but was largely concentrated in summer months and predominantly affected whirlpools and outdoor pools. Similar interannual increases reported in other European regions, including Croatia and the Balearic Islands [7,17], provide relevant context; however, the available data do not support causal inference regarding broader environmental or operational drivers. Overall, these findings highlight the importance of interpreting interannual fluctuations within the framework of installation type, seasonal operation, and site-specific operational conditions rather than solely in relation to tourism intensity.

Overall, these findings emphasize that temporal variability in P. aeruginosa contamination arises from the interplay of installation-specific vulnerabilities, operational dynamics, and seasonal patterns, rather than from climate or season alone. Surveillance and prevention strategies should therefore prioritize consistent year-round sampling and installation-specific risk assessment, particularly in high-risk environments such as whirlpools.

The finding that P. aeruginosa was the leading cause of immediate pool closures is particularly relevant for public health authorities and the tourism industry. Although clinical infections associated with swimming pools are relatively rare, P. aeruginosa has been implicated in folliculitis, otitis externa, keratitis, hot-foot syndrome, and, in exceptional cases, severe pneumonia among exposed individuals [13,14,15,16]. Given its well-known intrinsic and acquired antimicrobial resistance, some authors now consider this bacterium a pathogen of increasing relevance in both community and healthcare environments [38]. In the context of tourism, the occurrence of repeated closures may also have implications for consumer confidence and facility reputation, representing both health and an economic concern.

An additional relevant finding is the markedly lower prevalence of E. coli compared with P. aeruginosa. While fecal indicators were rarely detected (Table 1), P. aeruginosa was consistently identified across different installation types, supporting its role as a sensitive indicator of operational deficiencies rather than fecal contamination. This reinforces its suitability for routine surveillance in recreational water settings, particularly in tourist facilities where biofilm formation, disinfectant decay, and hydraulic conditions play a critical role.

As with all surveillance-based studies, certain limitations should be acknowledged. First, the study relied on point-in-time sampling, which may underestimate transient contamination events. Second, only samples from the pool basin (not the recirculation circuit) were collected, preventing identification of possible system reservoirs. Third, information on occupancy dynamics, cleaning frequency, and hydraulic performance was not systematically available, which limits the ability to quantify their individual impact. Despite these constraints, the dataset is robust, spans multiple years, and shows remarkable consistency with previous regional studies in Spain and international literature.

Overall, this study contributes valuable evidence to the growing body of data on P. aeruginosa in tourist swimming pools. The findings consistently highlight that contamination patterns are shaped not only by disinfectant levels and temperature but—perhaps more importantly—by operational and structural factors that promote biofilm formation and hinder disinfectant efficacy. The similarities between the present results and those from other Spanish regions reinforce the generalizability of these conclusions and suggest that targeted interventions focused on hydraulic optimization, routine mechanical cleaning, and high-quality maintenance procedures may provide the greatest impact. Taken together, these insights underscore the need for continuous surveillance and improved management practices in tourist pools to safeguard public health and maintain high standards of safety and quality in recreational water environments.

5. Conclusions

This four-year surveillance study demonstrates that P. aeruginosa contamination in tourist swimming pools is strongly influenced by installation type and operational conditions rather than by season alone. Whirlpools emerged as the most vulnerable installations, while apparent winter peaks were shown to reflect sampling patterns rather than true increases in risk. The findings support the use of P. aeruginosa as a sensitive operational indicator and highlight the importance of installation-specific surveillance strategies in tourist pool management.

The present study reinforces that P. aeruginosa remains a persistent microbiological challenge in tourist swimming pools, driven not only by disinfectant performance but by deeper structural and operational determinants. The consistency of our findings with previous data from other Spanish regions and international studies highlights the universal nature of these risks in high-occupancy recreational environments. By identifying whirlpools as the most vulnerable installations, demonstrating the limited discriminative power of residual disinfectant levels, and revealing seasonal patterns that extend beyond the summer season, this work underscores the need for comprehensive management strategies focused on hydraulic optimization, routine mechanical cleaning, and continuous surveillance. Strengthening these aspects will be essential to ensuring safer recreational waters and supporting the long-term quality and competitiveness of the tourism sector.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/w18020186/s1, Table S1: Monthly breakdown of the contamination by P. aeruginosa in the samples collected from the different types of investigated pools. Table S2: Yearly breakdown of the evolution of the contamination by P. aeruginosa in the samples collected from the different types of investigated pools. Table S3: Number of unique installations per hotel by pool type (Andalusia, 2016–2019). Table S4: Regulatory parameters in all Pseudomonas aeruginosa–positive samples by pool type (Andalusia, 2016–2019).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D.-S. and S.A.; methodology, A.D.-S., À.G.-A. and M.M.-B.; validation, S.A., À.G.-A. and M.M.-B.; formal analysis, A.D.-S.; investigation, A.D.-S., À.G.-A. and M.M.-B.; data curation, A.D.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D.-S.; writing—review and editing, S.A., À.G.-A. and M.M.-B.; supervision, A.D.-S. and S.A.; project administration, A.D.-S.; funding acquisition, A.D.-S. and S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the staff at the facilities visited who provided support during the sampling. During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGPT-5.1 to improve the readability and language of the manuscript. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Coxon, C.; Dimmock, K.; Wilks, J. Managing Risk in Tourist Diving: A Safety-Management Approach. In New Frontiers in Marine Tourism: Diving Experiences, Sustainability, Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; pp. 201–220. [Google Scholar]

- Wilks, J. Tourism and aquatic safety: No lifeguard on duty-swim at your own risk. Tour. Mar. Environ. 2017, 12, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, A.; Chochlakis, D.; Koufakis, E.; Carayanni, V.; Psaroulaki, A. Recreational Water Safety in Hotels: Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic and the Way Forward for a Safe Aquatic Environment. Tour. Hosp. 2024, 5, 1167–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Water Recreation and Disease; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9241563052/ (accessed on 11 July 2017).

- Esterman, A.; Roder, D.M.; Cameron, A.S.; Robinson, B.S.; Walters, R.P.; A Lake, J.; E Christy, P. Determinants of the microbiological characteristics of South Australian swimming pools. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1984, 47, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hlavsa, M.C.; Cikesh, B.L.; Roberts, V.A.; Kahler, A.M.; Vigar, M.; Hilborn, E.D.; Wade, T.J.; Roellig, D.M.; Murphy, J.L.; Xiao, L.; et al. Outbreaks Associated with Treated Recreational Water—United States, 2000–2014. Mmwr-Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2018, 67, 547–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lušić, D.V.; Maestro, N.; Cenov, A.; Lušić, D.; Smolčić, K.; Tolić, S.; Maestro, D.; Kapetanović, D.; Marinac-Pupavac, S.; Linšak, D.T.; et al. Occurrence of P. aeruginosa in Water Intended for Human Consumption and in Swimming Pool Water. Environments 2021, 8, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallolio, L.; Belletti, M.; Agostini, A.; Teggi, M.; Bertelli, M.; Bergamini, C.; Chetti, L.; Leoni, E. Hygienic surveillance in swimming pools: Assessment of the water quality in Bologna facilities in the period 2010–2012. Microchem. J. 2013, 110, 624–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crone, S.; Vives-Flórez, M.; Kvich, L.; Saunders, A.M.; Malone, M.; Nicolaisen, M.H.; Martínez-García, E.; Rojas-Acosta, C.; Gomez-Puerto, M.C.; Calum, H.; et al. The environmental occurrence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. APMIS 2020, 128, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Khan, A.U. Global economic impact of antibiotic resistance: A review. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2019, 19, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antimicrobial Resistance in the EU/EEA (EARS-Net)—Annual Epidemiological Report for 2020. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/antimicrobial-resistance-eueea-ears-net-annual-epidemiological-report-2020 (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- Gellatly, S.L.; Hancock, R.E.W. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: New insights into pathogenesis and host defenses. Pathog. Dis. 2013, 67, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajjartabar, M. Poor-quality water in swimming pools associated with a substantial risk of otitis externa due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Water Sci. Technol. 2004, 50, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Cheng, A.S.; Wang, L.; Dunne, W.M.; Bayliss, S.J. Hot tub folliculitis or hot hand-foot syndrome caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2007, 57, 596–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantazidou, G.; Dimitrakopoulou, M.E.; Kotsalou, C.; Velissari, J.; Vantarakis, A. Risk Analysis of Otitis Ex-terna (Swimmer’s Ear) in Children Pool Swimmers: A Case Study from Greece. Water 2022, 14, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craun, G.F.; Calderon, R.L.; Craun, M.F. Outbreaks associated with recreational water in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2005, 15, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doménech-Sánchez, A.; Laso, E.; Albertí, S. Environmental surveillance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in recreational waters in tourist facilities of the Balearic Islands, Spain (2016–2019). Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 54, 102622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doménech-Sánchez, A.; Laso, E.; Albertí, S. Prevalence and Control of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Tourist Facilities across the Canary Islands, Spain. Pathogens 2024, 13, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guida, M.; Gallè, F.; Mattei, M.L.; Anastasi, D.; Liguori, G. Microbiological quality of the water of recreational and rehabilitation pools: A 2-year survey in Naples, Italy. Public Health 2009, 123, 448–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, C.; Economou, V.; Sakkas, H.; Gousia, P.; Giannakopoulos, X.; Dontorou, C.; Filioussis, G.; Gessouli, H.; Karanis, P.; Leveidiotou, S. Microbiological quality of indoor and outdoor swimming pools in Greece: Investigation of the antibiotic resistance of the bacterial isolates. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2008, 211, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.E.; Heaney, N.; Millar, B.C.; Crowe, M.; Elborn, J.S. Incidence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in recreational and hydrotherapy pools. Commun. Dis. Public Health 2002, 5, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 19458; Water Quality-Sampling for Microbiological Analysis. International Organization for Standardization: Geneve, Switzerland, 2007.

- ISO 16266-2; Water Quality-Detection and Enumeration of Pseudomonas aeruginosa-Part 2: Most Probable Number Method. International Organization for Standardization: Geneve, Switzerland, 2018.

- Sartory, D.P.; Brewer, M.; Beswick, A.; Steggles, D. Evaluation of the Pseudalert/Quanti-Tray MPN Test for the Rapid Enumeration of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Swimming Pool and Spa Pool Waters. Curr. Microbiol. 2015, 71, 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 9308-2; Water Quality-Enumeration of Escherichia coli and Coliform Bacteria-Part 2: Most Probable Number Method. International Organization for Standardization: Geneve, Switzerland, 2014.

- Rosende, M.; Miró, M.; Salinas, A.; Palerm, A.; Laso, E.; Frau, J.; Puig, J.; Matas, J.M.; Doménech-Sánchez, A. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Chlorine-Based and Alternative Disinfection Systems for Pool Waters. J. Environ. Eng. 2020, 146, 04019094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Sanidad Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Real Decreto 742/2013, de 27 de septiembre, por el que se establecen los criterios técnico- sanitarios de las piscinas. Boletín Of. Estado 2013, 244, 83123–83135. [Google Scholar]

- Tirodimos, I.; Arvanitidou, M.; Dardavessis, T.; Bisiklis, A.; Alexiou-Daniil, S. Prevalence and antibiotic resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from swimming pools in Northern Greece. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2010, 16, 783–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesaluoma, M.; Kalso, S.; Jokipii, L.; Warhurst, D.; Ponka, A.; Tervo, T. Microbiological quality in Finnish public swimming pools and whirlpools with special reference to free living amoebae: A risk factor for contact lens wearers? Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1995, 79, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tirodimos, I.; Christoforidou, E.P.; Nikolaidou, S.; Arvanitidou, M. Bacteriological quality of swimming pool and spa water in northern Greece during 2011–2016: Is it time for Pseudomonas aeruginosa to be included in Greek regulation? Water Supply 2018, 18, 1937–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guida, M.; Di Onofrio, V.; Gallè, F.; Gesuele, R.; Valeriani, F.; Liguori, R.; Romano Spica, V.; Liguori, G. Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Swimming Pool Water: Evidences and Perspectives for a New Control Strategy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zekanović, M.S.; Begić, G.; Medić, A.; Gobin, I.; Linšak, D.T. Effects of a Combined Disinfection Method on Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilm in Freshwater Swimming Pool. Environments 2022, 9, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamere, L.; Smith, E.; Grieser, H.; Arduino, M.; Hlavsa, M.C.; Combes, S. Pseudomonas Infection Outbreak Associated with a Hotel Swimming Pool—Maine, March 2023. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brousseau, N.; Lévesque, B.; Guillemet, T.A.; Cantin, P.; Gauvin, D.; Giroux, J.-P.; Gingras, S.; Proulx, F.; Côté, P.-A.; Dewailly, É. Contamination of public whirlpool spas: Factors associated with the presence of Legionella spp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2013, 23, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaidou, S.; Anestis, A.; Bartzoki, S.-F.; Lampropoulou, E.; Dardavesis, T.; Haidich, A.-B.; Tirodimos, I.; Tsimtsiou, Z. Microbiological water quality assessment of swimming pools and jacuzzis in Northern Greece: A retrospective study. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2024, 35, 2421–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barben, J.; Hafen, G.; Schmid, J. Pseudomonas aeruginosa in public swimming pools and bathroom water of patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2005, 4, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junta de Andalucía—IECA. Encuesta de Coyuntura Turística de Andalucía (ECTA). 2025. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/institutodeestadisticaycartografia/dega/encuesta-de-coyuntura-turistica-de-andalucia-ecta/visualizacion-de-los-datos-anuales (accessed on 27 December 2025).

- Tacconelli, E. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: The WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.