Abstract

This study investigates groundwater levels (GWLs) in the alluvial aquifer of the Sava River valley, located in the north-western part of Croatia. It provides the first quantitative assessment of groundwater levels using machine learning in this part of Europe. Groundwater levels from 1998 to 2017 were predicted using support vector regression (SVR). The input variables were initially monthly data on two basic elements that influence groundwater dynamics (precipitation and the Sava River levels). Later, GWLs from the previous month (GWL-1) were added as an additional predictor. Results demonstrated that the SVR model effectively predicts groundwater levels. Introducing GWL-1 reduced RMSE and MAE values by more than 47% and 46%, respectively, while increasing the R2 value by over 36%. The improvement was more pronounced farther from the Sava River, since GWLs near the river are more directly influenced by river stage fluctuations, diminishing the impact of GWL-1. Compared to the existing regional numerical model (NM), the SVR model outperformed the NM with improvements of approximately 12% to 76% across performance indicators. Our findings suggest that the SVR model provides a reliable method for predicting groundwater levels at specific observation wells, making it a valuable tool for applications such as forecasting groundwater availability for farmers during dry periods and flood risk assessment during periods of heavy rainfall.

1. Introduction

Groundwater is an important water resource that is the primary source of water supply for the population and irrigation water in many countries. The quantitative status of groundwater is most often expressed through the groundwater level or groundwater discharge. It depends on the geological and hydrogeological characteristics of the area, and its geographical and meteorological characteristics.

Groundwater level (GWL) prediction, which is crucial for improving water resources planning and management, is most often the result of physical numerical models (NM) of groundwater flow. However, in the last two decades, machine learning (ML) methods used for GWL prediction have been intensively developed. A comprehensive review including all types of ML models used for GWL modeling is provided in the articles by Rajaee et al. [1], Tao et al. [2], Boo et al. [3], and Hou et al. [4]. Artificial neural network (ANN) models and their advanced versions, extreme learning machine (ELM) models, fuzzy logic (FL) models, and adaptive neuro fuzzy inference system (ANFIS), and deep learning (DL) models are discussed. There are also decision tree and data mining and evolutionary computing models applications, and a non-linear auto-regressive network with exogenous input (NARX) model. Hybrid ML models and statistical model applications are not left out, and attention is also paid to Kernel model applications, among which is the well-established support vector machine (SVM) model. Detailed research findings by Tao et al. [2], who used studies retrieved from journals indexed in the Web of Science, are listed below. It was found that the most commonly used time scale in the reviewed studies was the monthly step. When considering the time period analyzed, it appears that the 1-, 7-, 9-, 11-, and 15-year datasets were the most commonly used. The selection of input variables was mainly based on their influence on groundwater dynamics. Precipitation is generally the main input element of the groundwater balance (groundwater recharge), while evapotranspiration, which is directly influenced by air temperature, is the output element of the groundwater balance (groundwater discharge). It is therefore not surprising that among the most common input variables in ML models aiming to forecast GWL were precipitation (23%) and temperature (15%) [2]. Most studies used these input variables plus GWL, which is still the most common input variable in ML models. As many as 34% of ML models are based on GWL analysis alone [2]. Of the performance metrics (PM) that help understand model performance, the root mean square error (RMSE) and the coefficient of determination (R2) are the most commonly used. In most of the reviewed literature, the type of aquifer was not taken into account, e.g., whether they are aquifers with intergranular porosity or fractured or karst aquifers, and whether the aquifers are unconfined or semi-confined/confined.

Accurate and reliable prediction of GWLs is a critical component of effective groundwater management [5,6]. For instance, such predictions are essential for planning and implementing groundwater management strategies in Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR) systems or in agricultural regions where timely information on groundwater level fluctuations is in high demand. Due to the importance of estimating the relationship between irrigation demand and groundwater availability, ML models represent a practical alternative used for groundwater level prediction [7,8,9]. In this way, they can help with decision-making when it is necessary to consider quick and effective solutions for groundwater management [10].

Although ML models have been developing significantly over the past twenty years, their use in the world is still not widespread. The study by Tao et al. [2] states that Iran (36%), India (17%), the USA (9%), and China (9%) stand out in terms of the number of studies on GWL modeling using ML. In Europe, there are such studies in Great Britain, Germany, and Italy, while in most parts of Europe, they have not yet become popular, as evidenced by the lack of published studies on the subject. To at least partially fill this gap, machine learning was applied in our work to predict groundwater levels in a well-developed alluvial aquifer in the wider area of the Croatian capital, Zagreb. Specifically, the Support Vector Regression (SVR) method is used, a machine learning technique that has become increasingly popular in hydrological sciences due to its ability to provide accurate estimates. This method is grounded in statistical learning theory, making it a reliable tool for predictive modeling [7,11,12]. The excellent ability to generalize, with high prediction accuracy, and the reluctance to overfit are important advantages of SVR [13,14]. Comparing different ML models, Osman et al. [15] further conclude that SVM has a simpler structure, requires fewer hyper-parameters for adjustment, and can provide satisfactory results. By investigating the effectiveness of two machine learning algorithms (RF, SVM) and two deep learning algorithms (LSTM and Simple Recurrent Neural Network—SimpleRNN) in modeling GWL changes, Igwebuike et al. [16] found that they could not conclude on the “best” learning algorithm because the differences in their performance indicators were relatively small. However, the ML models performed slightly better than the DL models. In terms of the accuracy of predicted groundwater levels, the SVM performed best with an MAE of 0.356 m and an RMSE of 0.372 m. Zarafshan et al. [17] also concluded that optimized ML-based approaches are likely to be more effective for predicting groundwater levels than DL. Conversely, in the study by Yeganeh et al. [18], DL model LSTM achieved better results in modeling GWL compared to four shallow ML models (Multilayer Perceptron—MLP, Support Vector Regression—SVR, RF, Gradient Boosting Machine—GBM, and Voting Regression—VR) and another DL model (Convolutional Neural Network—CNN). However, the SVR model followed right behind it, and in both models, the R2 and RMSE values are close to 0.9 and 0.2, respectively, with slightly better values in favor of LSTM. The result confirms the conclusion of Igwebuika et al. [16] that it is difficult to decide on the best model. Previously, Wolpert [19,20] came to a similar conclusion, stating that “all learning algorithms are equivalent”.

A comparison of GWL prediction results using NM and ML has been conducted in several studies [21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. In all of them, ML was found to be a superior method for GWL prediction. Analyzing the results of NM and ANN, Zeydalinejad [25] concluded that ML models can be applied to heterogeneous and anisotropic aquifers without considering their detailed characteristics. Ebrahimi et al. [28] found that SVR and NM models provide similar results in predicting GWL under the influence of climate change, suggesting that ML can serve as a tool for rapid decision-making in groundwater management.

To date, no studies have applied ML methods for GWL prediction in the Zagreb aquifer located in the Sava River valley; consequently, a comparative analysis between numerical modeling and ML results has not been conducted. The objectives of our work are (1) to examine the ability of an SVR model, which incorporates a relatively small number of readily available input parameters (precipitation and the Sava River levels) to predict groundwater levels on a monthly scale; and (2) to compare the results of the applied SVR model and the NM according to Larva et al. [29] with a focus on their applicability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study

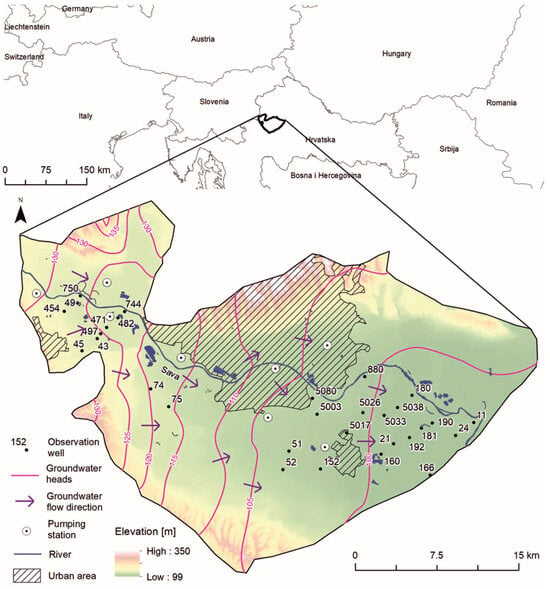

The groundwater level in the Zagreb alluvial aquifer is studied in this paper (Figure 1). In terms of productivity, it is a very important source of water supply in the north-western part of Croatia, including the capital city of Zagreb.

Figure 1.

Study area (modified from Larva et al. [29]).

The aquifer system consists of Quaternary sediments with a thickness that varies from approximately 10 m in the extreme west to 100 m in the east [29,30]. The hydraulic conductivity reaches up to 3600 m/d close to the Sava River. Towards the edges of the Sava valley, the aquifer hydraulic conductivity decreases. The semipermeable layer overlying the aquifer, which protects the groundwater, gradually increases in thickness from the river toward the edge of the alluvium, reaching about 4–6 m.

The aquifer is unconfined and recharged by infiltration of precipitation through a semipermeable covering layer and percolation of water from the Sava River riverbed. The riverbed cuts into a gravel–sand aquifer, establishing a strong hydraulic connection between the Sava River and the surrounding groundwater levels [31]. As a result—combined with the presence of multiple pumping sites near the river (Figure 1)—groundwater replenishment is partially supported through MAR. Due to the significant influence of the Sava River’s water level on groundwater fluctuations, it serves as a key input parameter for groundwater level prediction using machine learning models.

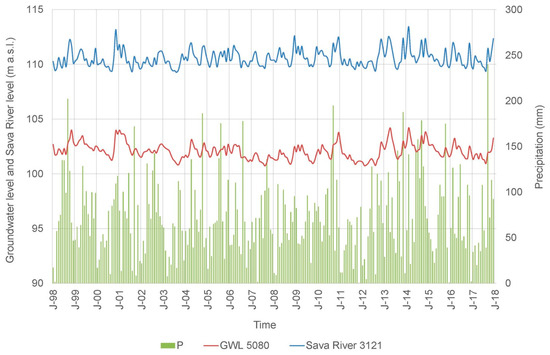

The general flow of groundwater is from west to southeast (Figure 1). Groundwater is drained into the Sava River in some places, and in some places, the Sava River recharges the aquifer. High groundwater levels in the Zagreb area mainly occur at the end of the year, and sometimes at the beginning of the year (Figure 2). Drought is recorded in the summer months. The difference between the high and low groundwater levels is approximately 2.5 m on average [31]. Groundwater levels are at depths between 3.5 and 12.5 m. Similar dynamics are observed in the water levels of the Sava River. Although the rainiest parts of the year are spring and autumn, the maximum monthly precipitation in the period 1998–2017 was recorded several times in August and September.

Figure 2.

Fluctuations in groundwater levels in the Zagreb aquifer (observation well 5080, located 700 m from the Sava River).

2.2. Data

The main factors that influence GWL are precipitation and the water level of the Sava River. River water level is a variable that has not been used frequently in previous studies. In their review of the input variables used in these studies, Hou et al. [4] listed 20 of them, including distance to surface water and stream flow, which describe the influence of surface flow on GWL. In our study, we used the water level of the Sava River because it has a strong influence on GWL and serves as a base for the recharge and discharge of the Zagreb alluvial aquifer. Water levels of the Sava River are monitored at five locations, from the Sava River’s entry into Croatia in the west to its exit from the City of Zagreb in the east. In the current study, the water levels of the Sava River measured at three water gauging stations were used: one in the western part of the study area, another in the central part, and the third in the far eastern part of the study area. At the same time, data from one rain gauge station were used in the analysis. Given the great importance of the Zagreb aquifer, groundwater levels are measured at approximately 250 observation wells. For the purposes of this study, 30 observation wells were selected, arranged in approximately 7 rows perpendicular to the Sava River. Measurements of the water levels of the Sava River and groundwater levels are carried out by the Croatian Meteorological and Hydrological Institute (DHMZ) and Hrvatske vode (legal entity for water management in Croatia). The amount of precipitation is measured by DHMZ. Monthly data on the water levels of the Sava River, groundwater levels, and precipitation in the period from 1998 to 2017 are used in the current study.

2.3. Cross-Correlation Method

The relationships between GWL and precipitation (P), and between GWL and the Sava water levels (H), were studied by cross-correlation analysis, and for each time step, the cross-correlation coefficient rxy(k) was calculated using the equations:

where σx and σy are the standard deviations of the input and output time series, respectively.

XLSTAT software (Lumivero, Denver, CO, USA) version 2023.1.2. was used for analyses.

2.4. Support Vector Regression

A support vector machine (SVM) is proposed by Vapnik [32]. It is a machine learning model that is used mostly for classification problems, while the Support Vector Regression (SVR), inspired by the SVM, is a regression algorithm. Building an SVM or SVR model consists of selecting support vectors that support the training architecture for the estimation of input time series, and determining their weights. SVR aims to train the function f(x) so that the input variable, x, can be mapped by the non-linear regression function as follows:

where wn and b are the weight vector and bias, and φn(x) displays the features of the input function. The error between f(x) and the observed values of y can be measured using hyper-parameter ε.

where ε (≥0) is user-defined and represents the maximum acceptable deviation.

Using a set of N (n = 1, 2, 3, …, N) input (xn) and output (yn) data pairs, the values of w and b are estimated by minimizing the objective function, F:

where C and ε are the hyper-parameters. To minimize the objective function, the Lagrange multipliers (αn, αn*) are used, and the final equation with the kernel function, K (xn, x), takes the form:

The SVR was kernelled with the Radial Basis Function (RBF), which has been successfully used in GWL prediction studies [8,11,17,33,34]. The width of the RBF kernel is determined by the gamma (γ) value. Its size is the inverse of the radius of the influence of training, which means that a low gamma value indicates a far-reaching influence of training; that is, it has an impact on a larger area. Conversely, its high value means that the training influence is close; that is, it is limited to a region close to the training example.

GWL prediction was performed in two phases. In the beginning, the determination of the input predictors was carried out, which, along with the adopted values of the SVR parameters, C, ε, and γ, gives the most reliable predicted GWLs. The SVR parameters were obtained by the trial-and-error method as described in Brkić and Larva [35]. The test was conducted at two locations (observation wells), one of which is located closer to the Sava River (piezometer 5080), and the other (piezometer 152) is approximately 6.5 km away from the Sava River (Figure 1). The SVR model was created for the period from January 1998 to December 2017. A monthly time step was used, so the analyzed period consisted of 240 time steps, which was divided into training period (1998–2011) and testing period (2012–2017). The training period consisted of 168 steps, and the testing period consisted of 72 steps; i.e., 70% and 30% of the data were used for training and testing the model, respectively. Approximately 20% of the last observations from the training sample were used for model validation.

After adopting the input predictors and parameters C, ε, and γ, the modeling of GWL at 30 locations (observation wells) started (Figure 1). The observation wells were chosen in such a way that they are located in different hydrogeological environments. Although they tap the same (shallowest) aquifer, the values of hydraulic conductivity differ at their locations due to its heterogeneity. Furthermore, they are located at different distances from the Sava River with different thicknesses of semi-permeable deposits. In this phase, the training period lasted from 1998 to 2012, and the testing period from 2013 to 2017. This small difference from the previous phase was used so that the SVR modeling results could be compared with the results of the numerical model calibration performed by Larva et al. [29]. The training period consisted of 180 steps, and the testing period of 60 steps; i.e., 75% and 25% of the data were used for training and testing the model, respectively. Five-fold cross-validation with the training data was performed.

For data modeling, the XLSTAT software (Lumivero, Denver, CO, USA) version 2023.1.2. was used.

2.5. Performance Metrics (PMs)

In GWL modeling, R2, RMSE, and MAE are the most commonly used performance indicators (PIs) [2,3]. In the current study, four PIs were used to assess the agreement between observed and simulated GWLs in the training period. Each PI reveals different information about the model [2]. The coefficient of determination (R2) measures the goodness of fit of the modeled data with the observed data, and it indicates the extent to which the forecasted data match the observed data. It measures the proportion of variance for a dependent variable that the independent variables of the model can explain. The mean absolute error (MAE) is the average absolute difference between observed and predicted data pairs. The average size of the error is determined by the root mean square error (RMSE). The formulas for their calculation are:

where n is the number of observations, GWLo is the observed GWL, GWLp is the predicted (simulated) GWL, and is the mean value of the observed GWL.

The high values of R2, and the low values of RMSE and MAE, indicate a good model.

3. Results

The correlation between GWL and the water level of the Sava River generally results in a decrease in the R2 value and an increase in the lag time with increasing distance of the observation well from the Sava River (Table 1). However, this relationship is not linear, so even at greater distances from the Sava River, R2 is relatively high and the lag time is small. R2 between GWL and precipitation ranges from 0.27 to 0.38 with a lag time of 0 to 7 months (Table 1). As a rule, a longer lag time refers to observation wells located in an area with a greater thickness of covering deposits. Given that the thickness of the covering deposits increases towards the edge of the alluvium and with the distance from the Sava River, a larger lag time usually refers to observation wells further away from the Sava River. However, the locations of observation wells that are closer to the Sava River, where there is a local thickening of the covering deposits, cannot be ruled out either.

Table 1.

List of monitoring wells, distance from the Sava River, and cross-correlation results.

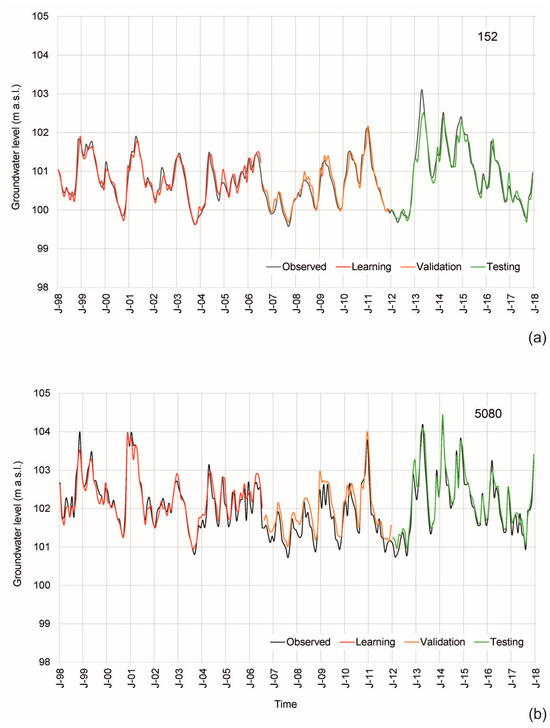

Quantitative assessment of R2, RMSE, and MAE indicates the accuracy of GWL prediction using the SVR model. Cross-correlation analysis determined that the best match of the observed GWLs at the location of observation well 152 was achieved for the Sava water level from the previous month (H-1) and the rainfall from six months ago (P-6) (Table 1), so these were the first time series that were analyzed. The observation well is located along the southern edge of the Sava alluvium, where the aquifer is covered with semipermeable deposits, so the reaction of the groundwater level to the water level of the Sava River and precipitation is slowed down. For all three analyzed datasets, training, validation, and testing, the achieved values of model PIs were R2 = 0.4–0.5, RMSE = 0.36–0.72, and MAE = 0.28–0.58 (Table 2). Better results were achieved when GWL from the previous month (GWL-1) was added to predictors H-1 and P-6 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Input parameters and prediction results of the SVR model for the period 1998–2017 (training period: 1998–2011, and testing period: 2012–2017) for two observation wells.

Different values of SVR parameters were analyzed by trial-and-error method, and the best fit between observed and predicted GWL was achieved for C = 10, ε = 0.01, and ε = 0.1, and γ = 0.01. The R2 value for all datasets (training, validation, testing) varied between 0.92 and 0.94; the RMSE was between 0.12 m and 0.21 m, and the MAE between 0.11 m and 0.15 m (Figure 3). This means that the RMSE and MAE values in the training, validation, and testing periods were reduced by more than 60 % and 61 %, respectively, and the R2 value was increased by more than 89 %.

Figure 3.

Observed and SVR predicted GWLs in different periods of modeling (learning, validation, and testing) for (a) observation well 152 and (b) observation well 5080.

For observation well 5080, the best fit between observed and predicted GWLs was achieved by cross-correlation for the Sava River water level from the current month (H-0) and the precipitation from the previous month (P-1) (Table 1). Using these two time series of data for the learning, validation, and testing periods, the model PIs were found to be very similar to those for observation well 152; R2 ≈ 0.6, RMSE = 0.4–0.7, and MAE = 0.28–0.63 (2). Also, by adding the GWL-1 to the input series H-0 and P-1, the SVR model was improved (Table 2). The best fit between observed and predicted GWLs was achieved for C = 10, ε = 0.01, γ = 0.05, and γ = 0.01. The R2 value for all datasets (learning, validation, testing) varied between 0.9 and 0.94; the RMSE was between 0.21 m and 0.32 m, and the MAE between 0.15 m and 0.28 m (Figure 3). In other words, the RMSE and MAE values in the training, validation, and testing periods were reduced by more than 47 % and 46 %, respectively, and the R2 value was increased by more than 36 %.

Very low values of RMSE and MAE indicate an excellent fit. According to Singh et al. [36], if the RMSE and MAE values are less than half the standard deviation (SD) of the observed data, they can be considered low, indicating the suitability of the model for making predictions. In our case, the SDs of the observed GWLs for the observation well 5080 are 0.64, 0.60, and 0.81 in the learning, validation, and training datasets, respectively. For the observation well 152, the SDs of the observed GWLs are 0.56, 0.55, and 0.85 in the learning, validation, and training datasets, respectively. By comparing the RMSE and MAE values in Table 2, it is observed that the values of these indicators are higher than half the SD (SD/2) in the case of using the input time series for H and P. However, by including the GWL-1 time series in the input data, for observation well 152, regardless of the values of the SVR parameters, the RMSE and MAE values are lower than SD/2 for the learning and validation sets, and only in three cases are the RMSE values higher than SD/2 for the testing set. The situation is similar in the case of observation well 5080, except that the given condition is satisfied for the learning and testing sets, while the RMSE values for all analyzed SVR parameters are higher than SD/2 in the validation set. The bias for observation well 5080 was −0.07, and for observation well 152 was 0.55, indicating a slight overestimation compared to observations.

For further analyses at other observation wells, due to low RMSE and MAE values, and high R2 values, a value of 10 was adopted for the parameter C, and a value of 0.01 for the parameter ε. For observation wells near the Sava River (up to 1 km), a value of 0.05 was adopted for the parameter γ, and for observation wells distant from the Sava River, a value of 0.01. For each observation well, the GWL-1 time series and the H and P time series were used, respecting the time step with the best correlation with the GWL (Table 1).

For most of the analyzed observation wells, a relatively good match was observed between the observed and simulated GWLs for all datasets: learning, cross-validation, and testing data (Table 3). The mean R2 value was 0.83 for the learning dataset, 0.8 for the cross-validation, and 0.81 for the testing dataset. This means that 83% of the GWL variability in the learning period, 80% of the GWL variability in the cross-validation, and 81% of the GWL variability in the testing period were explained by the corresponding input variables, which include groundwater level for the previous month, and, according to Table 1, Sava River water level for the current or previous month, and precipitation for previous months. The mean RMSE and MAE values varied from 0.26 m and 0.19 m in the learning dataset to 0.33 m and 0.25 m in the testing dataset. For the learning period, RMSE values are slightly higher than SD/2 for two observation wells (744 and 471) in the western part of the Zagreb aquifer (Figure 1). For the validation period, RMSE values are higher than SD/2 for four observation wells (49, 744, 482, and 471). All observation wells are located in the western part of the Zagreb aquifer (Figure 1). For both learning and validation periods, MAE values are lower than SD/2 for all analyzed observation wells. For the testing period, RMSE values are slightly higher than SD/2 for six observation wells, four of which (454, 482, 471, and 497) are located in the western part of the aquifer, and two in the eastern part of the aquifer (5003 and 5033) (Figure 1). The MAE value was higher than SD/2 only for observation well 454.

Table 3.

Performance indicators of the SVR model and numerical model calibration [29] for 30 observation wells.

4. Discussion

4.1. SVR Model Performance

In all modeling phases, the SVR model produced RMSE and MAE mostly lower than 0.3 m (Table 3). These PIs are comparable to the results of past studies [9,37,38,39], although different ML algorithms were used. For example, the PIs of the SVR and M5 decision tree models for groundwater level prediction in the Ardebil plain in Iran [9] are very similar to the indicators obtained in our SVR model. For the 24 observation wells analyzed using both ML models, the mean RMSE was approximately 0.30 m and the mean R2 was 0.86 (in original R = 0.92). The input variables included the groundwater level for the previous month, monthly precipitation volume, and groundwater discharge. The groundwater level in the previous month was the most effective input variable. In contrast, the prediction of the mean monthly groundwater level in Vizianagaram district, Andhra Pradesh, India, using ANN, genetic programming (GP), SVM, and ELM [38] showed that ELM performed best, while SVR gave only slightly worse results than ELM. The mean RMSE, MAE, and R2 using the SVR model were approximately 0.59 m, 0.46 m, and 0.89, respectively. Compared to our results, RMSE and MAE are slightly higher, but R2 is a bit better. Furthermore, in another study that analyzed monthly GWLs [39], it was demonstrated that, according to the PIs, the SVM-RBF (support vector machines with radial basis functions) model with RMSE = 1.94 (in original MSE = 3.78), MAE = 1.42, and R = 0.9 performed better than multi-linear regression (MLR), adaptive neural fuzzy inference system (ANFIS), and radial basis neural network (RBNN) for all performance evaluations. The support vector machines with poly kernels (SVM-PK) performed only slightly worse than the SVM-RBF model.

In our case, the results of the SVR model for observation wells 74 and 75 are interesting. The wells are located 3 and 3.5 km from the Sava River. The R2 between GWL and the Sava River water level is relatively low (0.58 and 0.54) with a lag time of 2 months, and the R2 between GWL and precipitation is 0.36 and 0.38 with a lag time of 6 months (Table 1). However, the results of the applied SVR model show relatively good PIs values (Table 3). This confirms that the SVR method has good generalization and prediction capabilities, as reported by Awad and Khanna [13] and Saleh and Rasel [14].

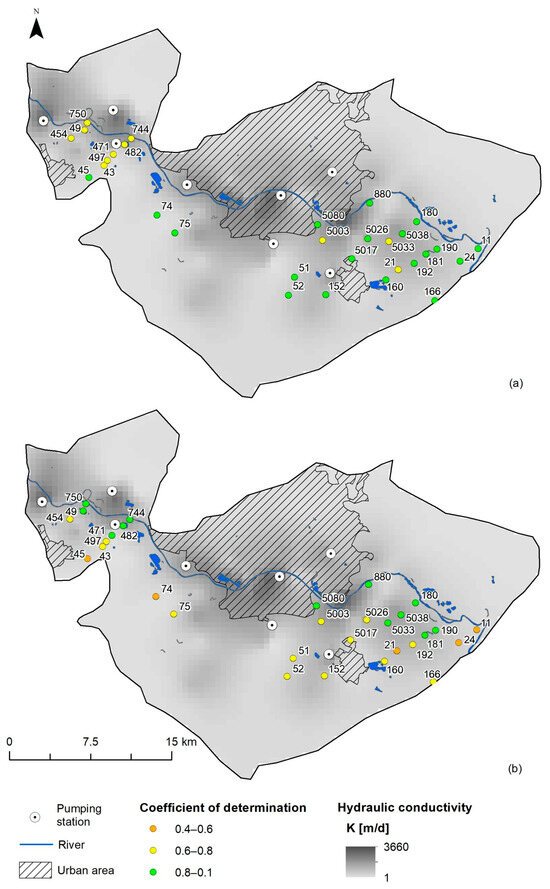

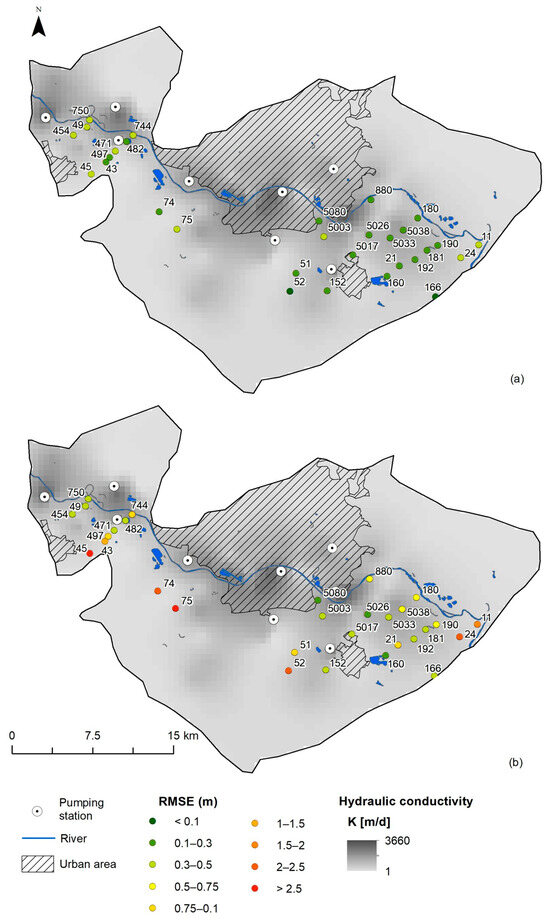

4.2. Comparison of SVR Model and Numerical Model

Comparing the results of the numerical model of groundwater flow in the Zagreb aquifer [29] and the SVR model described here, it was observed that the performance indicators are better for the SVR model than the NM (Table 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5). The mean R2 value for the NM was 0.74, and the mean RMSE and MAE values were 0.88 m and 0.80 m, respectively. This means that the mean R2 in the SVR model (learning dataset) was approximately 10% better than in NM, and the mean RMSE and MAE were approximately 3 and 4 times lower than in NM, respectively. Similar conclusions were reached by Chen et al. [40] and Goodarzi et al. [37]. In their study, the RMSE and R2 values demonstrated that the ML models, and especially the SVM model, achieved higher accuracy than NM.

Figure 4.

Spatial distribution of R2 calculated for the period 1998–2012 using (a) SVR and (b) NM.

Figure 5.

Spatial distribution of RMSE calculated for the period 1998–2012 using (a) SVR and (b) NM.

A more detailed look at the modeling results for individual observation wells shows significantly lower R2 values and higher RMSE and MAE values in the NM compared to the SVR model. This primarily applies to locations in the marginal parts of the aquifer (observation wells 43, 45, 74, 75, 52—Figure 4 and Figure 5, Table 3). This is primarily due to the limited understanding of hydrogeological relationships in this part of the aquifer system, which plays a crucial role in the accuracy of physical models like the NM used in the study by Larva et al. [29]. A similar situation was observed for observation wells 24 and 11, which, although located relatively close to the Sava River, are located near the established NM boundary, which affected the result.

The results further show that in cases where the R2 value is significantly higher in the NM than in the SVR model (e.g., observation wells 750, 744, 482), the RMSE and MAE are simultaneously higher in the NM than in the SVR model (Table 3). This means that a larger proportion of the variability in GWL is explained by the input variables in the NM (aquifer system geometry, initial and boundary conditions, and hydrogeological parameters) than by the input data (groundwater level, Sava River level, and precipitation) in the SVR model. However, the difference between the predicted and observed (measured) GWLs is higher in the NM than in the SVR model, as indicated by the RMSE and MAE values (Table 3). This suggests that the SVR model is more accurate, as it better predicts the response variable.

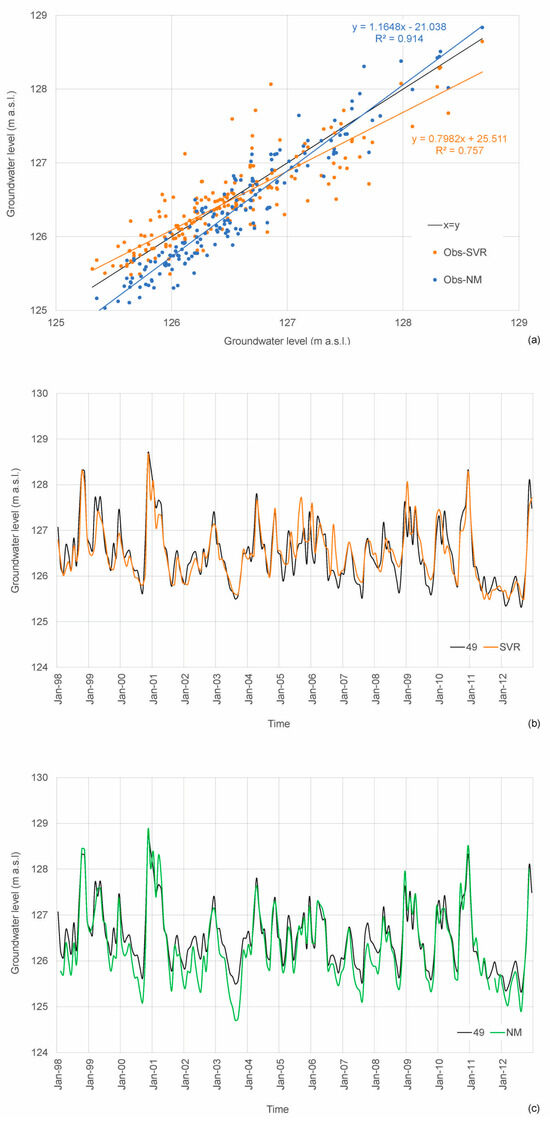

Additionally, different R2 values can correspond to similar errors, as observed in the case of observation well 49 (Table 3, Figure 6). In the SVR model, an R2 value of 0.76 was obtained for the training period, while the NM yielded a higher R2 of 0.91 for the same period (Table 3, Figure 4). Despite this difference, both models produced identical RMSE values of 0.33 m, with MAE values of 0.23 m for the SVR model and 0.27 m for the NM (Table 3, Figure 5).

Figure 6.

Observed and predicted GWL in the observation well 49: (a) observed vs. SVR predicted GWLs, and observed vs. NM predicted GWLs, respectively; (b) time series of the observed and SVR predicted GWL; and (c) time series of the observed and NM predicted GWL.

The main advantage of NMs over ML models is that they are physically based, incorporating the hydrogeological properties of the aquifer. This makes them a better choice for analyzing groundwater dynamics under different stress conditions, such as climate change or groundwater abstraction change, as well as for studying solute transport. However, developing an NM is both time-consuming and requires expertise in groundwater flow.

In less complex scenarios with limited hydrogeological data—where accurate groundwater level predictions are needed at specific observation wells, such as for sustainable groundwater management using MAR, agricultural planning during dry months, or flood forecasting in rainy seasons—ML models offer a more efficient and effective alternative. They require fewer data inputs and can generate predictions much faster. In such cases, ML and DL models have become valuable tools for groundwater level forecasting.

4.3. Limitations

In the current study, the selection of SVR parameters was performed using the trial-and-error approach, i.e., by setting default values for the SVR parameters and evaluating them across all modeling phases: learning, validation, and testing. The best set of default SVR parameter values was selected based on a comparison of the PIs. Today, this approach is used less frequently and has been replaced by selection models that yield optimal SVR parameter values. The most commonly used methods are the grid search method, the genetic algorithm (GA), and particle swarm optimization (PSO). These methods should certainly be employed in future research. The input data for the SVR model were only the main factors affecting GWL, the water level of the Sava River, and precipitation. In addition to the water level of the Sava River and precipitation, GWL is also affected by evaporation, or evapotranspiration, which was not taken into account because they are not monitored as such, and their amounts are not available in the analyzed period. In the study of GWL forecasts using ML, temperature is also one of the input data used [2]. In our study, temperature was not used, even though it could be a partial proxy for evapotranspiration—for example, higher temperatures in summer correspond to higher evapotranspiration and, conversely, lower temperatures in winter give practically no evapotranspiration. The study area is relatively highly urbanized, and the depth of groundwater is greater than the roots of crop vegetation, whose depth is generally less than 2 m, so exceptionally high evapotranspiration is not expected. The average annual calculated potential evapotranspiration (PET) for the period 1961–1990 was 657 mm, which was 77% of the average annual precipitation [41]. For the period 1971–2000, PET was 83% of the average annual precipitation. The average annual air temperature for the period 1979–2024 in Zagreb is increasing intensively, and since 2011, temperature anomalies have generally been positive, with the emphasis that since 2022 they have been constantly above 1.5 °C [42]. It is to be expected that PET has also increased. In this context, future research should focus on whether including temperature in the input data would significantly improve the accuracy of the SVR model. The quantities of groundwater pumped for water supply purposes are relatively stable and do not contribute significantly to the monthly fluctuations of GWL at the analyzed locations, especially since most of them are not in the immediate vicinity of the pumping station. Unfortunately, data on groundwater pumping for irrigation purposes are not known in Croatia. In such circumstances, pumped rates are not taken into account in the GWL forecast using the SVR method. In some future research, when a daily time step is applied and when, for example, the catchment area of a pumping site is observed, pumped rates will have a much more important role in the fluctuations of GWL, and it will not be able to be ignored.

Furthermore, in this study, SVR simulations were conducted using monthly groundwater levels, Sava River levels, and precipitation as input variables. Despite the heterogeneity of the aquifer (Figure 4 and Figure 5), a relatively good agreement between the observed and simulated groundwater levels (GWLs) was found for most of the analyzed observation wells (Table 3). The results demonstrated that the applied SVR model provides a relatively accurate GWL forecast, performing comparably to more advanced ML and DL models, as shown in the studies by Zarafshan et al. [17], Yeganeha et al. [18], and Igwebuike et al. [16]. However, when forecasting abrupt GWL fluctuations under, e.g., pronounced climate change conditions, models trained on daily data performed significantly better using advanced DL algorithms such as LSTM and XGBoost [43]. Thus, future research should focus on GWL forecasting at finer time scales where additional variables will need to be considered, as well as on exploring novel modeling approaches that can enhance predictive accuracy. Such advancements will contribute to more effective water resource management and better adaptation strategies for climate change.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents groundwater level forecasts for the alluvial aquifer in north-western Croatia. The SVR model was used for modeling, analyzing a 20-year period from 1998 to 2017. Our study provides the first quantitative assessment of groundwater levels using machine learning in this part of Europe.

In the first phase of the research, the input variables for the SVR model included the water level of the Sava River and precipitation. In the second phase, GWLs from the previous month (GWL-1) were added as an additional predictor. The model with three predictors outperformed the model with only two, demonstrating improved accuracy. Introducing GWL-1 reduced RMSE and MAE values by more than 47% and 46%, respectively, while increasing the R2 value by over 36%. The improvement was more pronounced for observation wells located farther from the Sava River, as expected, since groundwater levels near the river are more directly influenced by river stage fluctuations, diminishing the impact of GWL-1.

The SVR model was learned, validated, and tested on data from 30 observation wells, using measured GWL, H, and P. The model’s effectiveness was confirmed by mean PI values: R2 > 0.80 and RMSE and MAE below 0.33 m. Compared to an existing regional NM, the SVR model achieved approximately 12% higher R2, and significantly lower RMSE (by 71%) and MAE (by 76%).

Our findings demonstrate that the applied SVR model is a reliable tool for predicting groundwater levels at specific observation wells. Such predictions are particularly valuable in practical applications, such as forecasting groundwater availability for farmers during dry periods or assessing flood risks during the rainy season.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ž.B.; methodology, Ž.B.; formal analysis, Ž.B. and O.L.; investigation, Ž.B. and O.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Ž.B. and O.L.; writing—review and editing, Ž.B. and O.L.; visualization, Ž.B. and O.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research has received funding from the Croatian Scientific Foundation (HRZZ) under grant number HRZZ-IPS-2024-02-5367.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Hrvatske Vode and the Croatian Meteorological and Hydrological Institute for providing monitoring data. We are grateful to the editors and reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions on our manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rajaee, T.; Ebrahimi, H.; Nourani, V. A review of the artificial intelligence methods in groundwater level modeling. J. Hydrol. 2019, 572, 336–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.; Hameed, M.M.; Marhoon, H.A.; Zounemat-Kermani, M.; Heddam, S.; Kim, S.; Sulaiman, S.O.; Tan, M.L.; Sa’adi, Z.; Mehr, A.D.; et al. Groundwater level prediction using machine learning models: A comprehensive review. Neurocomputing 2022, 489, 271–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boo, K.B.W.; El-Shafie, A.; Othman, F.; Khan, M.M.H.; Birima, A.H.; Ahmed, A.N. Groundwater level forecasting with machine learning models: A review. Water Res. 2024, 252, 121249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Zhou, A.; Huang, P. Trends, challenges, and opportunities in groundwater level modeling with machine learning. Environ. Earth Sci. 2025, 84, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S.; Jha, M.K.; Kumar, A.; Sudheer, K.P. Artificial neural network modeling for groundwater level forecasting in a river island of eastern India. Water Resour. Manag. 2010, 24, 1845–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamowski, J.; Chan, H.F. A wavelet neural network conjunction model for groundwater level forecasting. J. Hydrol. 2011, 407, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, S.M.; Paz, J.O.; Tagert, M.L.M.; Mercer, A. Artificial neural networks and support vector machines: Contrast study for groundwater level prediction. In Proceedings of the 2015 ASABE Annual International Meeting, New Orleans, LO, USA, 26–29 July 2015; p. 152181983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, S.M.; Paz, J.O.; Tagert, M.L.M.; Mercer, A.E. Evaluation of Seasonally Classified Inputs for the Prediction of Daily Groundwater Levels: NARX Networks Vs Support Vector Machines. Environ. Model. Assess. 2019, 24, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattari, M.T.; Mirabbasi, R.; Sushab, R.S.; Abraham, J. Prediction of groundwater level in Ardebil plain using support vector regression and M5 tree model. Groundwater 2018, 56, 636–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Salvo, C. Improving Results of Existing Groundwater Numerical Models Using Machine Learning Techniques: A Review. Water 2022, 14, 2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, S.; Bian, J.; Wan, H.; Sun, X.; Zhang, B. Simulation and uncertainty analysis for groundwater levels using radial basis function neural network and support vector machine models. J. Water Supply Res. Technol.–AQUA 2017, 66, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.D.; Zang, C.P.; Wei, Y.; Jiang, M.H. Data-driven modeling of groundwater level with least-square support vector machine and spatial-temporal analysis. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2019, 37, 1661–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, M.; Khanna, R. Support Vector Regression. In Efficient Learning Machines; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.A.; Rasel, H.M. Machine learning for groundwater levels: Uncovering the best predictors. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2024, 10, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.I.A.; Ahmed, A.N.; Huang, Y.F.; Kumar, P.; Birima, A.H.; Sherif, M.; Sefelnasr, A.; Ebraheemand, A.A.; El-Shafie, A. Past, present and perspective methodology for groundwater modeling-based machine learning approaches. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2022, 29, 3843–3859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igwebuike, N.; Ajayi, M.; Okolie, C.; Kanyerere, T.; Halihan, T. Application of machine learning and deep learning for predicting groundwater levels in the West Coast Aquifer System, South Africa. Earth Sci. Inform. 2025, 18, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarafshan, P.; Etezadi, H.; Javadi, S.; Roozbahani, A.; Hashemy, S.M.; Zarafshan, P. Comparison of machine learning models for predicting groundwater level, case study: Najafabad region. Acta Geophys. 2023, 71, 1817–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeganeh, A.; Ahmadi, F.; Wong, Y.J.; Shadman, A.; Barati, R.; Saeedi, R. Shallow vs. Deep Learning Models for Groundwater Level Prediction: A Multi-Piezometer Data Integration Approach. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2024, 235, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpert, D.H. The Relationship Between PAC, the Statistical Physics Framework, the Bayesian Framework, and the VC Framework. In The Mathematics of Generalization: The Proceedings of the SFI/CNLS Workshop on Formal Approaches to Supervised Learning; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpert, D.H. The supervised learning No-Free-lunch theorems. In Soft Computing and Industry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S.; Jha, M.K.; Kumar, A.; Panda, D.K. Comparative evaluation of numerical model and artificial neural network for simulating groundwater flow in Kathajodi-Surua Inter-basin of Odisha, India. J. Hydrol. 2013, 495, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekzadeh, M.; Kardar, S.; Shabanlou, S. Simulation of groundwater level using MODFLOW, extreme learning machine and wavelet-extreme learning machine models. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 9, 100279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, H.K.; Moghaddam, H.K.; Kivi, Z.R.; Bahreinimotlagh, M.; Alizadeh, M.J. Developing comparative mathematic models, BN and ANN for forecasting of groundwater levels. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 9, 100237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuhaylan, M.R.; Ghumman, A.R.; Al-Salamah, I.S.; Ahmad, A.; Ghazaw, Y.M.; Haider, H.; Shafiquzzaman, M. Evaluating the impacts of pumping on aquifer depletion in arid regions using MODFLOW, ANFIS and ANN. Water 2020, 12, 2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeydalinejad, N. Artificial neural networks vis-a-vis MODFLOW in the simulation of groundwater: A review. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2022, 8, 2911–2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, S.; Rajabi, A.; Shabanlou, S.; Yosefvand, F.; Izadbakhsh, M.A. Prediction of groundwater level variations using deep learning methods and GMS numerical model. Earth Sci. Inform. 2023, 16, 3227–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, K.S.; Shabanlou, S.; Rajabi, A.; Yosefvand, F.; Izadbakhsh, M.A. Prediction of groundwater level fluctuations using artificial intelligence-based models and GMS. Appl. Water Sci. 2023, 13, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, R.S.; Eslamian, S.; Zareian, M.J. Groundwater level prediction based on GMS and SVR models under climate change conditions: Case study—Talesh Plain. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2023, 151, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larva, O.; Brkić, Ž.; Briški, M.; Seidenfaden, I.K.; Koch, J.; Stisen, S.; Refsgaard, J.C. An ensemble approach for predicting future groundwater levels in the Zagreb aquifer impacted by both local recharge and upstream river flow. J. Hydrol. 2022, 613, 128433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brkić, Ž. The relationship of the geological framework to the Quaternary aquifer system in the Sava River valley (Croatia). Geol. Croat. 2017, 70, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, T.; Brkić, Ž.; Larva, O. Using hydrochemical data and modelling to enhance the knowledge of groundwater flow and quality in an alluvial aquifer of Zagreb, Croatia. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 458–460, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vapnik, V.N. The Nature of Statistical Learning Theory; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 123–160. [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo, M.; Kasot, A.; Dhar, A.; Kar, A. On Predictability of Groundwater Level in Shallow Wells Using Satellite Observations. Water Resour. Manag. 2018, 32, 1225–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajewska-Szkudlarek, J.; Kubicz, J.; Kajewski, I. Correlation approach in predictor selection for groundwater level forecasting in areas threatened by water deficits. J. Hydroinform. 2022, 24, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brkić, Ž.; Larva, O. Impact of climate change on the Vrana Lake surface water temperature in Croatia using support vector regression. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 54, 101858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Knapp, H.V.; Demissie, M. Hydrologic Modeling of the Iroquois River Watershed Using HSPF and SWAT; ISWS CR 2004-08; Illinois State Water Survey: Champaign, IL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Goodarzi, M.R.; Bafrouei, H.B.; Vazirian, M. Insight into groundwater level prediction with feature effectiveness: Comparison of machine learning and numerical methods. Hydrol. Res. 2025, 56, 74–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, N.; Sudheer, C. Groundwater level forecasting using soft computing techniques. Neural Comput. Appl. 2020, 32, 7691–7708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirci, M.; Üneş, F.; Körlü, S. Modeling of groundwater level using artificial intelligence techniques: A case study of Reyhanlı region in Turkey. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2019, 17, 2651–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; He, W.; Zhou, H.; Xue, Y.; Zhu, M. A comparative study among machine learning and numerical models for simulating groundwater dynamics in the Heihe River Basin, northwestern China. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaninović, K.; Gajić-Čapka, M.; Perčec Tadić, M.; Vučetić, M.; Milković, J.; Bajić, A.; Cindrić, K.; Cvitan, L.; Katušin, Z.; Kaučić, D.; et al. Klimatski Atlas Hrvatske/Climate Atlas of Croatia 1961–1990, 1971–2000; Državni Hidrometeorološki Zavod: Zagreb, Croatia, 2008; p. 200. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.meteoblue.com/en/climate-change/zagreb_croatia_3186886 (accessed on 2 January 2026).

- Osman, A.I.A.; Latif, S.D.; Boo, K.B.W.; Ahmed, A.N.; Huang, Y.F.; El-Shafie, A. Advanced machine learning algorithm to predict the implication of climate change on groundwater level for protecting aquifer from depletion. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 25, 101152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.