Abstract

Studying sedimentary distribution in water reservoirs is essential to understand the depositional processes and develop sustainable environmental management strategies. Characterization of deposited sediments provides information about the sources of particulate matter, transport patterns and predominant deposition mechanisms in different compartments of the reservoir. This study aimed to evaluate active deposition processes and to improve the understanding of sedimentation in water reservoirs. In this case, the Espora hydroelectric power plant, located on the Corrente River, southwestern Goiás, Brazil, was employed as a model environment. Sediment cores were collected at 29 points along the reservoir, covering different aquatic compartments. Particle-size analysis of the sediments was performed based on established methodologies using textural classification to identify sedimentary facies. The results indicated the predominance of stream deposits (sandy material) in areas where water flow velocity was higher, and bed deposits, composed predominantly of clays and silts, in regions of lower water flow velocity and greater depth.

1. Introduction

The increased demand for food, electricity production, irrigation and flood control has intensified the need to expand the construction of water reservoirs around the world [1,2]. Reduction in water turbulence velocity in the reservoirs reduces its transport capacity, favoring the continuous and gradual deposition of sediments and nutrients transported by the course of rivers and streams [3]. This accumulation contributes to reducing water storage capacity, sedimentation problems and siltation, which is one of the main problems in the operational management of reservoirs worldwide [4] and, consequently, to lower energy generation, in addition to compromising the use and useful life of these places over time [2,5].

Globally, reservoirs lose on average 0.5–1.0% of their water storage capacity, with higher rates in areas prone to severe storms [6]. In line with these climatic characteristics of a given region, the geology, topography, type of vegetation and land use in the region contribute not only to the number of sediments that arrive, but also to their quality [7]. In addition to these physical characteristics, the geometry of the reservoir directly influences the distribution and sedimentation of sediments [8].

Valley reservoirs, which are the most common, have an elongated and narrow shape, being shallower in the upstream parts and deeper near the dam, downstream [9]. This configuration results in a well-defined longitudinal depositional gradient [6,10]. Sediments deposited in the reservoir can give rise to three different types of deposits: stream, delta and bed deposits [11,12]. Stream deposits are located further upstream of the reservoir, where deposits of larger and heavier particles, especially coarser sands, occur, and may have clay and silt lenses. Delta deposits occur mainly at the mouths of the tributaries in the reservoir, with different sizes of sediments (sand, silt and clay), which are deposited in an interspersed manner and contribute to the gradual decrease in the useful volume of the reservoir. Bed deposits constitute the material deposited in the bed of a reservoir, known as bed sediment, which can contain different types of particles, such as fine sand, silt and clay, which occur mainly near the dam, with possible occurrence of very fine sand strata. This sediment deposition in the riverbed can reduce water storage capacity and residence time [12,13]. Methodologies employed to evaluate sedimentation processes and to predict the useful life of reservoirs are generally categorized into three major approaches: direct methods, indirect methods, and numerical hydro-sedimentological models [14].

Direct methods are characterized by the quantification of volumetric loss through in situ measurements. This approach includes bathymetric techniques, ranging from traditional single-beam systems to advanced multibeam scanning, as well as sediment-core sampling [15,16]. The study of [15] on the Itacarambi River Reservoir in Brazil exemplifies the application of bathymetric surveys using echo sounding to calculate silted volumes, whereas [16] employed topographic cross-section data to quantify sediment deposition in the Baihetan Reservoir, China. Indirect methods are useful to determine sedimentation rates from hydrometric data, watershed morphometric characteristics, and remote-sensing techniques using satellite imagery, such as the Landsat and Sentinel programs, combined with water-level time series [17]. Indirect estimation may also rely on well-established empirical models, including those proposed by [18,19], which provide sedimentation predictions based on statistical relationships and physical attributes of the drainage basin. The work described by [17] accurately demonstrates this approach by integrating Sentinel-2 imagery and water-level data to estimate sedimentation rates in eight North American reservoirs, achieving a mean error of 0.05% year−1. Finally, numerical hydro-sedimentological models represent the most dynamic approach, simulating the physical processes of sediment transport through mathematical formulations. Modeling systems such as HEC-RAS and MIKE are widely used to reproduce complex phenomena, including the formation and propagation of turbidity currents, sediment stratification, and spatial deposition patterns throughout the reservoir [20]. The study of [20] at the Shihmen Reservoir illustrates the application of a two-dimensional turbidity-current model to develop real-time operational strategies, with model predictions validated against historical typhoon events.

Despite these advances, a research gap remains regarding the application of facies-based sedimentation analysis in small and medium-sized tropical reservoirs, particularly in regions with marked seasonality, where rainy periods generate high sediment loads due to soil leaching, followed by a dry season with low precipitation, as observed in the Brazilian Cerrado. While numerous studies investigate sediment deposition through bathymetry, remote sensing, or numerical modeling, the understanding of how depositional facies evolve under tropical hydroclimatic conditions remains limited. The novelty of this study lies not in selecting a new area, but in applying an integrated facies-based approach combining sediment cores, granulometry, and spatial facies mapping to interpret sedimentation mechanisms in the Espora Reservoir. This methodological integration remains underexplored in Brazilian reservoirs, particularly in the Central-West region, and seeks to address relevant technical for understanding sedimentation processes.

Research on sedimentation in reservoirs in Brazil began to gain relevance from the 1980s onwards [13,14]. The types of sediment deposits were identified using hydro-sedimentological processes involving topography of the bottom of the reservoirs and the textural classes of the sediments [5,13,14]. Some studies were conducted by using reservoir morphometry [21,22], while others the description of sediments, through the analysis of facies, which considered depositional models in action [13,14,23]. Although the Espora Reservoir represents a regional case study, the methodological approach adopted, based on depositional facies, sediment texture, and spatial distribution, has broad applicability for hydroelectric reservoirs located in tropical, subtropical, and semi-arid regions on a global scale, giving its international relevance. In light of recent major climate challenges, marked by the increasing frequency of extreme events, numerous countries face similar problems related to sediment accumulation, loss of storage capacity, and the need for sustainable reservoir management. Thus, the process-based framework developed here provides a transferable tool capable of supporting the understanding of sedimentation mechanisms with the aim of extending reservoir lifespan and energy generation in global contexts.

Taking into account the absence of research on analyses of reservoirs in the Brazilian Midwest region, Ref. [24] presented a proposal adapted to the model of [25,26,27] to classify and analyze the sedimentation facies of reservoirs. Thus, the objective of this study was to analyze the sedimentation processes and verify which are the depositional models and their distribution in the reservoir of the Espora Hydroelectric Power Plant (HPP) on the Corrente River. With in-depth knowledge about sedimentary facies, their distribution and particle size can be used to optimize sediment management strategies in reservoirs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

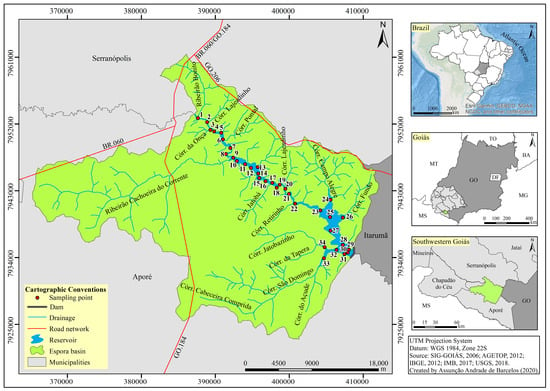

Aiming to fill the research gap on sedimentation in reservoirs in southwestern Goiás, where hydraulic projects are being planned and built, such as the Estrela HPP, at UTM coordinates Longitude 431,638 Latitude 7,954,831, and the Taboca PCH, at UTM coordinates Longitude 441,966 Latitude 7,951,724, between the municipalities of Serranópolis and Itarumã, on the Verde River, a tributary of the right bank of the Paranaíba River basin, the research area was proposed as presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Location of the study area on influence of the Espora HPP.

The reservoir of the Espora HPP is located in the middle third of the Corrente River, formed by the junction of the Formoso and Jacuba rivers, which originate within the Emas National Park, and has an extension of around 450 km. As a tributary of the right bank of the Paranaíba River, it forms the border between the Minas Gerais and Goiás States, forming the Paraná Sedimentary Basin. The reservoir is located downstream of the village of Itumirim, at the intersection of BR 060 and GO 184, among the municipalities of Serranópolis, Aporé and Itarumã, with the UTM-WGS84 Projection system, Sheet SE-22-YB [28,29].

The construction of the Espora HPP reservoir began in 2001 and ended in 2006, with a flooded area of 30.6 km2, water storage of 240 × 106 m3, and an installed energy capacity of 32 MW. The area of the Espora HPP is part of the Paraná Sedimentary Basin, formed by basaltic rocks of the Serra Geral Formation—São Bento Group, corresponding to the Mesozoic Era of the Cretaceous Period, and sandstone rocks, of the Vale do Rio Peixe Formation—Bauru Group. This last-mentioned formation is located at the top of the basin, formed by sandstone extracts, permeated with siltstones or mudstones, sandy, fine to very fine, with light brown to pinkish-orange colors, with carbonate cementation (CaCO3) and rocks from the Undifferentiated Detrital Cover Unit with alluvial deposits, formed in the most recent Quaternary [30]. The relief of the basin, which is part of the Regional Planing Surface (SRAIII-RT), with elevations ranging from 553 to 850 m, is associated with flat and gently undulating slopes [31].

The soils of the basin are mainly Latossolos (Oxisols) and Neossolos Quartzarênicos (Quartzipsamments). Some studies showed that Latossolos Vermelhos distróficos (Oxisols) occupy about 89.2%, while Neossolos Quartzarênicos (Quartzipsamments) occupy around 10.5% of the basin area [31,32], with 91.8% of flat to gently undulating areas, with slope ranging from 0 to 8%.

According to Köppen’s classification, the climate of the Cerrado is Aw type, with an average temperature of around 23.4 °C [33]. The climate of the Brazilian Midwest region has two well-defined seasons, that is, a less rainy period (dry winter) between May and September, and a rainy period (humid summer), from October to April, with average annual rainfall of around 1400 to 1600 mm. The period with the highest levels of rainfall occurs from December to March.

2.2. Sediment Collections

Sediment sampling was performed during the rainy season in the Brazilian Cerrado, a period characterized by increased surface runoff and higher sediment load entering the reservoir. At each sampling site, vertical sediment cores were collected using a KAJAK-type sediment sampler (model LTC04; Limnotec, São Carlos, SP, Brazil). The sampler was attached to a rope and carefully lowered to the reservoir bottom. A PVC tube (50 mm in diameter and 70 cm in length) was coupled to the sampler and served as a liner for recovering undisturbed sedimentary profiles. This procedure was applied at 29 sampling points distributed along a longitudinal transect, from the upstream fluvial sector through the transitional zone to the lacustrine sector of the Espora HPP reservoir, ensuring spatial representativeness of the distinct depositional environments. After collection, the PVC tubes containing the cores were kept in an upright position. Small holes (0.5 mm) were drilled along the upper portion of the sampled material to accelerate drainage and promote controlled drying of the sedimentary profiles. This step allowed efficient removal of excess water while preserving the structural integrity of the cores. Subsequently, the tubes were longitudinally opened using a Makita® circular saw (Model HS7010, Makita Corporation, Anjo, Aichi, Japan, with a 1600 W motor, a 185 mm blade, and a speed of 5500 rpm) and left to dry completely at room temperature, exposing the internal stratigraphy for description and analysis.

Macroscopic analyses of the vertical cores were conducted under natural light, using a magnifying glass to refine visual inspection. The following sedimentological parameters were systematically described: color, grain size, textural variation, mineralogical composition, sedimentary structures, and bed architecture (thickness, geometry, and contact relationships) [34,35] according to the methodology adopted by [13,24,34]. Facies classification followed the system proposed by Cabral et al. [24], which employs combined codes of uppercase and lowercase letters (Table 1) to represent both grain size (uppercase letters) and textural subdivisions or sedimentary structures (lowercase letters). This coding enables standardized and comparable identification of sedimentary facies within the reservoir [26].

Table 1.

Acronyms used for textural and structural identification of bottom sediments in the Espora HPP reservoir.

Based on facies classification, sedimentary processes and depositional models were interpreted according to the methodological framework of Cabral et al. (2010), as follows [13,24]:

- Bed Deposit (F): composed predominantly of clay and silt; may occasionally contain thin layers of very fine to fine sand.

- Delta Deposit (FS): characterized by the mixture of bottom material (silt–clay, F) and sandy fraction (S); represents the first materials deposited when the fluvial flow loses energy upon entering the reservoir environment.

- Stream Deposit (S): composed mainly of sand, with possible lenses or intercalations of clay and silt [26].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Study Area

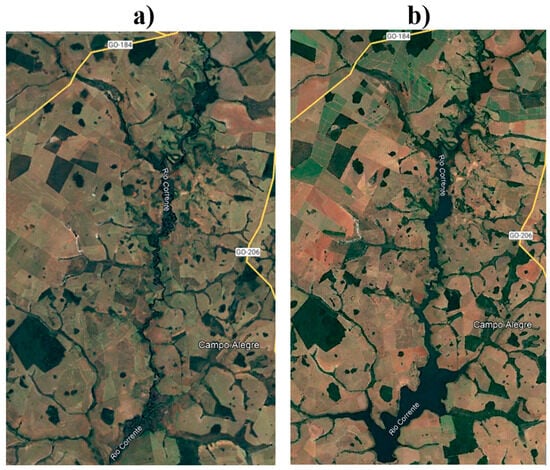

Figure 2a,b present a spatial-temporal cutout of a Google Earth image from 2002 (a) and 2020 (b) showing the area flooded by the Espora HPP dam.

Figure 2.

(a,b)—Spatial-temporal cutout of a Google Earth image from 2002 (a) and 2020 (b) showing the area flooded by the Espora HPP dam.

This project was built on the old bed of this watercourse, sitting on basaltic rocks of the Serra Geral Formation. The banks, currently submerged by the reservoir, are under the influence of sedimentary rocks of the Vale do Rio do Peixe Formation. Since the construction of the plant’s dam, the Corrente River has undergone changes in its bed, mainly due to the transition from a lotic environment to a lentic environment [13,36]. This change reduced its sediment and nutrient transport capacity, resulting in siltation and eutrophication at specific points. Similar results were observed in other hydraulic projects in the southwest of Goiás and in several reservoirs in Brazil [13,23,37].

Another relevant factor in the region is soil degradation, which affects the stability of the earth’s surface in terms of water quality and the siltation of reservoirs. Some studies indicate that erosive processes are directly associated with the expansion of agricultural activities [31,38,39]. Agriculture began in the 1960s and was consolidated in the 1970s and 1980s, being currently marked by a growing presence of sugarcane crop in the Cerrado, which has contributed to the reduction in native vegetation. The results of these studies demonstrate that the southwest of Goiás has high susceptibility to erosion, characterized by gently undulating reliefs supported by sandstones and sandy soils, widely used for extensive pasture [31,39].

The natural physical factors of the Espora HPP watershed, associated with land use, contribute to the increase in emerging environmental fragility [31]. The low slope and the pedological characteristics of the region, such as the less sandy texture of the Latossolos (Oxisols) compared to the Neossolos (Entisols), prevented its classification as an area of high environmental fragility, although the impacts of erosion are evident. Thus, it is clear that soil erosion is the main responsible for the transport of sediments, which have different origins, such as the weathering of rocks, the degradation of river banks, and the displacement of surface particles mobilized by rainfall and surface runoff [40,41]. This process causes the degradation of aquatic environments, compromising ecosystems and the functionality of reservoirs. Soil erosion generates impacts that go beyond surface degradation, directly affecting water quality and the functioning of reservoirs [13,31,36].

Sediment transport in watercourses occurs from different sources, including eroded soil, weathering of rocks, and erosion of river banks. These sediments are mobilized by the action of rain and surface runoff, and are subsequently transported to water bodies, where they can compromise water quality and aquatic biodiversity [42,43]. In view of this scenario, the evaluation of sediment transport in watersheds becomes indispensable for estimating the volume of siltation in watercourses and reservoirs. This diagnosis is essential to predict the useful life of the reservoirs and establish guidelines for sustainable occupation of the region [44,45].

3.2. Analysis of Sedimentary Profiles

The study of sediments is essential for understanding the sedimentation processes in reservoirs, as it allows the detailed analysis of deposition and siltation over time. Evaluation of these profiles makes it possible to identify sedimentation rates, particle size, composition of deposits and contamination, providing information for reservoir management [14,46]. The formation of sedimentary layers may indicate seasonal variations in material input, anthropogenic influences and changes in the hydrodynamic conditions of the reservoir. These analyses are essential to predict the reduction in the storage capacity of reservoirs and to support management strategies that minimize the impacts of siltation [13,24]. In addition, characterization of sedimentary profiles makes it possible to evaluate the origin and transport of sediments, allowing the correlation of erosion sources with the level of deposition in reservoirs [47,48].

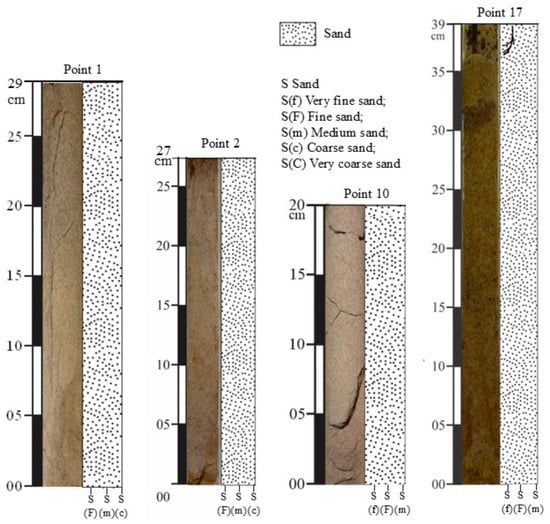

The analysis of the 29 sedimentary profiles of the Espora HPP reservoir allowed the identification of three main depositional models, conceived as Stream, Delta and Bed deposits. The sedimentary profiles P1, P2, P3, P5, P6, P10, P11, P13, P17, P19 and P20 were characterized as stream deposits as presented in Figure 3, reflecting the influence of the high flow velocity of water from the Corrente River and its tributaries.

Figure 3.

Vertical cores of the sampling points of stream deposits in the Espora HPP reservoir.

These profiles showed the transition of a high-energy environment, with sedimentation represented by the particle-size fractions of very fine sand S(f), medium sand S(m) and coarse sand S(c). The analyzed deposits have thicknesses ranging from 20 to 39 cm, showing homogeneous characteristics, light yellow to light brown color and low organic matter content. This composition indicates an environment with oscillatory flow typical of rainy periods, when sediments are carried and subsequently deposited in backwater zones during periods of lower precipitation and lower transport energy. The predominance of sandy sediments in these profiles is directly related to the geology of the region, composed of the Undifferentiated Detrital Cover Units (Qdi), which occupy 17.74% of the left bank of the Espora HPP reservoir, and the Bauru Group of the Vale do Rio do Peixe Formation, which covers 34.37% of the basin and consists predominantly of sandstone rocks [31,36].

The facies corresponding to the stream deposits represent approximately 37.9% of the facies analyzed in the reservoir, characterized by a sedimentary sequence composed of very fine to coarse sands, with good particle-size selection. This process occurs due to the differentiated deposition of sediments: while sandy particles tend to settle more quickly, silty-clayey fractions remain in suspension for a longer period and settle only when the flow velocity decreases significantly. The transport of the bottom material occurs predominantly by rolling or saltation, characterizing an environment of high energy in the rainy periods and differentiated sedimentation according to the variation in fluvial dynamics [1,49].

According to studies on hydro-sedimentological compartmentalization in the Caçu HPP reservoir and in the Foz do Claro River HPP reservoir, a predominance of sandy sediments was also identified in the profiles analyzed in stream deposits. These results corroborate the observations made in the Espora HPP reservoir, where the areas of influence of the sampled points had typical characteristics of stream deposits. In this sector of the reservoir, the hydro-sedimentological dynamics are marked by relatively high flow velocities and more intense oscillatory flows, due to the greater direct influence of the Corrente River. This phenomenon occurs, above all, in stretches where the banks are narrower and the depth is reduced compared to other compartments of the reservoir. These conditions favor the selective deposition of sandy sediments, as identified in the sedimentary profiles analyzed, reinforcing the relationship between the geomorphology of the reservoir and the observed sedimentation patterns.

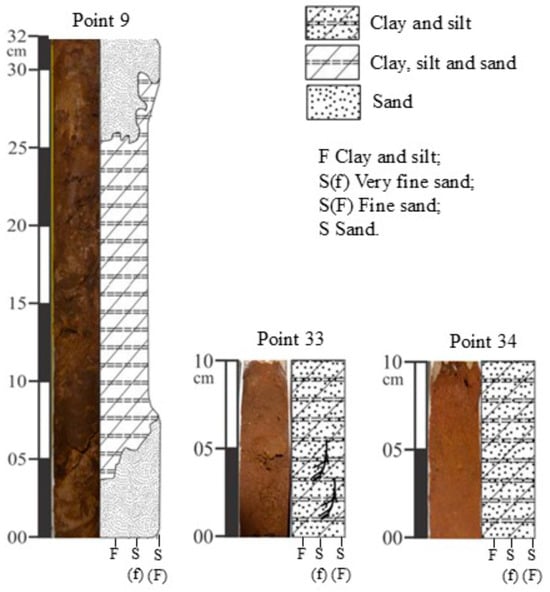

Delta deposits in reservoirs are formed in the mouth areas of tributaries that flow into the water body, where there is a significant reduction in water flow velocity. This deceleration decreases the sediment transport capacity, resulting in progressive deposition. This process is amplified by the increase in the cross-section of the reservoir, which favors different types of sedimentation. The main consequence of this phenomenon is the gradual reduction in the useful volume of the reservoir, impacting its operational capacity over time [14]. In the study area, the delta deposits are represented by 9, 33 and 34, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Facies of the delta deposits of points 9, 33 and 34 in the Espora HPP reservoir.

The characterization of the vertical sedimentary profiles and the analysis of the materials deposited in the cores sampled at these points indicated the predominance of silty-clayey sediments interspersed with silty-clayey sand. The particle-size variation observed in these profiles reflects the influence of different source areas, oscillations in the flow rate of tributaries, variations in rainfall levels and anthropogenic impacts on the contributing watersheds. Sediments with length of 32 cm were found in the cores of point 9, located at the mouth of the Cachoeira do Corrente stream, whose drainage area is predominantly occupied by sugarcane crops and extensive livestock farming. Points 33 and 34, both with 10 cm-long sediments, are located at the mouths of the São Domingos and Tapera creeks, respectively. These three points are under the influence of the Vale do Rio do Peixe (K2VP) and Serra Geral geological formations, with predominant soils of the Latossolo Vermelho and Latossolo Vermelho Distrófico types (Oxisols), mostly used for extensive livestock farming [13]. The sedimentary facies identified in these deposits include S(cl)—clay, S(si)—silt, S(vfs)—very fine sand and S(fs)—fine sand, being composed largely of silty-clayey material.

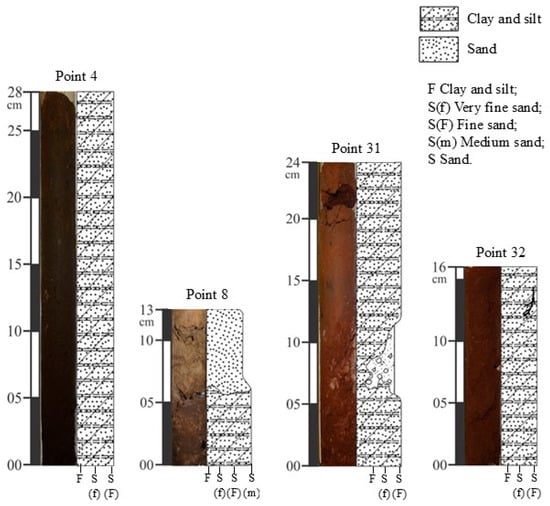

The bed deposits in the Espora HPP reservoir were identified at points P4, P7, P8, P12, P14, P15, P16, P18, P21, P23, P26, P30, P31 and P32, where very fine sand, silt and clay materials predominate as presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Facies of the bed deposits of points 4, 8, 31 and 32 of the Espora HPP reservoir.

Bed deposits are composed of fine silt and clay particles, which are usually transported in suspension in the waters, especially in areas closest to the reservoir dam, in transition zones with low flow velocity. In these areas, due to the greater depth and width, there is greater settling and deposition of sediments. The material deposited in this environment is predominantly composed of clayey and silty sediments, with small layers of very fine to fine sand, which are deposited below the silt and clay layers. It is possible to observe that the profiles ranged from 0.13 to 0.28 m, with predominance of silty-clayey sand. The codes of the identified facies include: F—clay and silt, S(f)—very fine sand, and S(m)—medium sand. These sediments are influenced by the Vale do Rio do Peixe Formation, located in the areas of higher elevations of the basin, composed of sandstones with a structure of fine to very fine particles.

The proximity to the dam and the distance from the banks are determining factors in the sedimentary dynamics. The farther from the banks and the closer to the dam, the lower the water flow velocity and the longer the residence time of the water in the reservoir, which favors the deposition of silty-clayey materials [13]. Overall, in lacustrine environments with a lower concentration of suspended materials, there is greater water transparency, favoring the deposition of finer materials, such as silt and clay [13,24].

Analysis of the sediment cores of the Espora HPP reservoir revealed that the predominant facies is F, characterized by bed deposits composed of materials with textures ranging from clay to silt. Deposits in reservoirs are directly related to the geological and pedological characteristics of the watershed [50]. Suspended particles, such as silt and clays, tend to be deposited in areas of the reservoir with lower water flow velocity, greater width and depth, and greater water transparency.

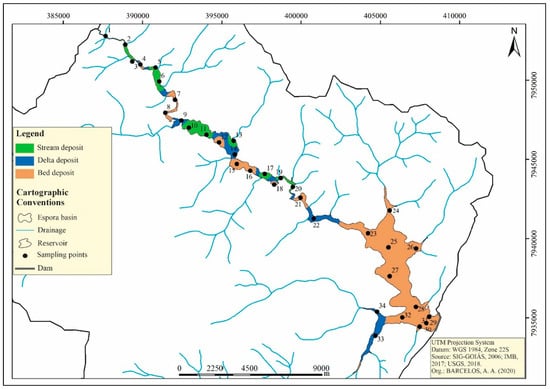

3.3. Spatial Analysis of the Sedimentation Process

Spatial analysis plays a fundamental role in understanding sedimentological processes in reservoirs, as it allows the visualization and interpretation of variations in sediment distribution along different areas of the reservoir. In the case of the Espora HPP, this approach makes it possible to understand how the different types of deposits, such as stream, delta and bed, are spatially distributed and how they are influenced by hydrodynamic, geological and anthropogenic variables. Based on this spatialization, it is possible to map the zones of greatest sedimentation, predict the impact of sedimentation on the useful volume of the reservoir and provide support for the implementation of sedimentation management and control strategies, ensuring the sustainability and efficiency of the plant’s operation.

The spatial analysis of the vertical cores and sedimentary facies in the Espora HPP reservoir reveals important sedimentation patterns that are fundamental to understand the depositional models present in the area. The sedimented material in the reservoir is predominantly sandy, located in the most upstream portion of the reservoir, where the water flow velocity is higher due to the direct influence of the river. In contrast, in the vicinity of the dam, the areas with greater depth and lower flow velocities have a higher concentration of silt and clay, forming a lentic environment with a longer water residence time, a typical model of a lacustrine environment [13,51].

The spatialization of the sedimentary profiles revealed the distribution of the different types of facies and how the stream, delta and bed depositional models are configured in the Espora HPP reservoir, as illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Spatialization of stream, delta and bed deposits of the Espora HPP in the Corrente River.

It was observed that the bed facies are predominant between points 23 and 32, where the water flow velocity is significantly reduced compared to the other areas. In these regions, turbidity concentration and suspended sediment load (SSL) are lower and water transparency is high, favoring the deposition of finer materials, such as silt and clay. The delta deposits were identified at the mouths of the tributaries that flow into the reservoir, especially at points 09 (Cachoeira do Corrente stream), 14 (Boa Esperança creek), 22 (Retirinho creek), 33 (São Domingos creek) and Dam and Jatobazinho and Tapera creeks. These tributaries are predominantly livestock farming areas, except for Cachoeira do Corrente stream and São Domingos creek, which have agricultural areas along their banks and headwaters [31,36]. At these points, the deposits are predominantly composed of silty-clayey and sandy materials. The deposition of sediments in delta areas is one of the main factors that contribute to the gradual reduction in the useful volume of the reservoir, while bed deposits contribute to the siltation of the dead volume [10,52].

In valley-type reservoirs, hyperpycnal delta deposits commonly develop near the mouths of tributaries, where rapid dissipation of flow energy promotes the deposition of coarser sediments, mainly sand. As the flow approaches the dam, the progressive reduction in flow velocity, the increase in water depth, and the longer residence time favor the settling of fine sediments, predominantly silt and clay, forming typical lacustrine bed deposits [52,53]. According to [54], the most vulnerable sectors of a reservoir, those associated with reduced operational safety and decreased useful lifetime, are the areas subjected to the highest sedimentation rates, particularly delta-forming zones and regions near the dam. In the present study, Points 09, 14, 22, and 33 were clearly identified as the most vulnerable areas, as they correspond to sectors receiving the highest sediment inputs from tributaries while exhibiting low sediment transport capacity, resulting in intense and sustained deposition. These tributaries drain catchments characterized by intensive land use, mainly agricultural and livestock activities, which enhance soil erosion and accelerate reservoir siltation. Therefore, Points 09, 14, 22, and 33 represent the critical zones of the reservoir, where the progressive loss of useful storage volume is most likely to occur due to continuous sediment accumulation.

Additional factors that contribute to the increase in sedimentation in the Espora HPP reservoir include land occupation in the watershed, with activities such as extensive livestock farming, which causes erosion of the banks, and agriculture, with sugarcane, soybean, and corn cultivation practices [31,36]. Removal of vegetation and preparation of the soil for cultivation increase surface erosion, which contributes to the transport of sediments to the reservoir, especially during periods of higher rainfall, as has been verified in other studies [6,50]. In addition, the geology of the watershed, composed mainly of sandstones from the Vale do Rio Peixe Formation, alluvial deposits, and undifferentiated detrital cover units, also plays a crucial role in sedimentary dynamics. The low compaction and cementation of the materials, combined with environmental degradation, exacerbate the erosive processes, resulting in the transport of particulate matter to the reservoir, especially during heavy rains, which accelerates the sedimentation process and shortens its useful life.

The hydrodynamics of the reservoir also exhibited marked spatial variability. Between Points 01 and 20, the high-energy flow regime still retains typical riverine characteristics, with sand deposits occurring in areas of greater flow velocity. This pattern indicates that this sector is the least vulnerable zone of the reservoir, as the high hydraulic energy (e.g., the upstream lotic sector) limits sediment accumulation and favors the transport rather than the deposition of suspended material. As a result, sedimentation rates are lower, and sandy sediments predominate in this region. Delta deposits occur at points near the dam and in the transition zones, where the energy of the water is reduced, with the mixture of sand, silt and clay fractions. The high hydrodynamics are justified because, between the sector from point 01 to point 20, the reservoir maintains the characteristics of a river. It was possible to verify that the sand deposits are located in the areas with the highest water flow velocity. Delta deposits, on the other hand, occur in places where the tributaries have the power to act on the reservoir, mixing the sand, silt and clay fractions.

Hyperpycnal flows (density currents generated during flood events) are responsible for redistributing sediments throughout the reservoir, creating bed deposits even in areas far from the dam [52]. These flows transport suspended sediments to more distal portions of the reservoir, where hydrodynamic energy is reduced, allowing the deposition of fine materials (silt and clay). A similar process was observed at Points 7, 8, 12, 15, and 16 of the Espora Reservoir. Another important factor is the irregular morphology of the reservoir bottom, with paleochannels and depressions that promote sediment deposition. The presence of tributaries and the complex geomorphology of the valley, such as submerged channels inherited from the pre-impoundment period, can generate low-energy zones even in upstream sectors. This demonstrates that sedimentation is not solely a function of distance to the dam but is also influenced by episodic processes and valley geometry.

The progressive damping of fluvial energy after water enters the reservoir creates transition zones, even in segments located far from the dam. This decreases the flow velocity due to channel constrictions, inflections, abrupt increases in depth, or interactions with submerged bars [51]. Such phenomena favor the deposition of finer sediments, forming bed-type facies even in environments that are not fully lacustrine. Therefore, a consistent explanation can be used for the depositional model observed at Points 15 and 16, which are located within the delta–lake transition zone, characterized by moderate to low energy and by the predominance of bed facies.

Silt-clay concentrations were identified at the points of lower energy, close to the dam, with longer water residence time, greater deposition and sedimentation of the finer material. The facies pattern and the textural distribution for the reservoir reveal a sedimentation model in which materials of coarser particle size predominate in the downstream regions (lotic environment). As the distance to the dam decreases, the deposition of finer sediments, such as silt and clay, occurs. Characterization of the sediment cores and facies analysis indicate that the deposition of sediments in the reservoir is directly influenced by the water circulation and flow velocity, which generally has a multidimensional and non-uniform flow, with periodic and non-uniform circulations, with periodic and permanent circulations depending on the influence of precipitation.

Based on the vertical cores and the type of sediment deposited along the 29 sampling locations, it is possible to infer that the spatial organization of the Espora HPP reservoir follows the classical stream–delta–bed model described by [47,52] and other researchers. A progressive loss of storage capacity is evident, reflected in the predominance of fine sediments (silt and clay) in the lacustrine zone near the dam, with formation of deltaic deposits at the main tributary inlets. These patterns indicate that both the useful storage zone and the dead storage zone are being progressively infilled. Although pre-impoundment bathymetric data are not available for direct comparison with the depositional models, the spatial distribution and thickness of the sedimentary facies provide strong evidence that the reservoir has already lost part of its original storage capacity, particularly in the most vulnerable sectors (Points 09, 14, 22, and 33). This behavior is consistent with global studies documenting the cumulative impact of fine sediment deposition on the reduction in effective storage volume in small hydropower reservoirs.

The depositional patterns identified in the Espora HPP reservoir also allow future trends to be inferred. For instance, if soil-loss processes in the watershed remain at current levels due to intensive land use, widespread agricultural and pastoral activities, the degraded soils and deltaic deposits will continue to progress toward the central portion of the reservoir. Moreover, bed deposits will continue to accumulate fine sediments near the dam. Thus, in the absence of effective sediment-management practices within the watershed, the reservoir is expected to experience accelerated siltation, a reduction in useful storage capacity, and increasing depositional asymmetry over time.

4. Conclusions

The identification of the three main types of sedimentary deposits in the Espora HPP reservoir reinforces the influence of hydrodynamic characteristics on sediment distribution, providing support for more effective sedimentation mitigation strategies. Stream deposits occur in the region upstream of the reservoir, characterized predominantly by sandy sediments. Delta deposits are found at the mouths of tributaries, showing a mixture of sand, silt, and clay. Finally, bed deposits are predominant in the areas near the dam, composed mainly of fine sediments, such as silt and clay. The results show the influence of the geological and hydrodynamic characteristics of the region on the distribution of sediments in the reservoir. Factors such as land use and occupation, erosion of the banks and climatic conditions are determinants in the intensity of the sedimentation process. Understanding these processes is essential for developing management strategies that minimize the impacts of siltation and ensure the sustainability of the reservoir. This study reinforces the need for the continuous monitoring of sediments, combining techniques such as riparian vegetation rehabilitation and erosion control in watersheds to mitigate sediment deposition in reservoirs.

Author Contributions

A.A.d.B.: Data curation, formal analysis; J.B.P.C.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration; F.L.R.: Data curation, formal analysis; P.d.S.G.: Data curation, formal analysis; H.M.R.: Data curation, formal analysis; V.A.B.: Roles/writing—original draft; A.T.P.: Data curation, Funding acquisition, resources, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, Brazil)—Grant numbers: 434884/2018-9 and 313064/2022-9). Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa e Inovação do Estado de Santa Catarina (FAPESC, Brazil)—Grant numbers: 2023/TR331 and 2024TR002572. Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES, Brazil)—Finance Code 001.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

JBPC thanks the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, Brazil) for the financial support (Grant number: 434884/2018-9). ATP thanks the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa e Inovação do Estado de Santa Catarina (FAPESC, Brazil) for the financial support (Grant numbers: 2023/TR331 and 2024TR002572) and CNPq, Brazil for the research productivity fellowship (Grant number: 313064/2022-9). This study was also funded in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES, Brazil—Finance Code 001).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cunha, D.G.F.; Calijuri, M.D.C.; Lamparelli, M.C. A trophic state index for tropical/subtropical reservoirs (TSItsr). Ecol. Eng. 2013, 60, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Gao, B.; Gao, L. Influence of hydrological regime on spatiotemporal distribution of boron in sediments in the Three Gorges Reservoir, China. J. Hydrol. 2021, 601, 126818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.A.; Cho, A.; Abid, M.; Abdul Wajid, H.; Ahmed, M. Modeling sediment transport on the storage capacity and life prediction of Sadpara dam. Mehran Univ. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2025, 44, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, F.-Z.; Lai, J.-S.; Sumi, T. Reservoir Sediment Management and Downstream River Impacts for Sustainable Water Resources—Case Study of Shihmen Reservoir. Water 2022, 14, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foteh, R.; Garg, V.; Nikam, B.R.; Khadatare, M.Y.; Aggarwal, S.P.; Kumar, A.S. Reservoir Sedimentation Assessment Through Remote Sensing and Hydrological Modelling. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2018, 46, 1893–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedláček, J.; Bábek, O.; Grygar, T.M.; Lenďáková, Z.; Pacina, J.; Štojdl, J.; Hošek, M.; Elznicová, J. A closer look at sedimentation processes in two dam reservoirs. J. Hydrol. 2022, 605, 127397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Swarnkar, S. Impact of Reservoirs on Suspended Sediment Dynamics in Rivers: A Review. In Blue Sky, Blue Water; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iradukunda, P.; Bwambale, E. Reservoir sedimentation and its effect on storage capacity—A case study of Murera reservoir, Kenya. Cogent Eng. 2021, 8, 1917329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilgert, S.; Sotiri, K.; Fuchs, S. Review of methods of sediment detection in reservoirs. Int. J. Sediment Res. 2023, 39, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedláček, J.; Bábek, O.; Nováková, T. Sedimentary record and anthropogenic pollution of a complex, multiple source fed dam reservoirs: An example from the Nové Mlýny reservoir, Czech Republic. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 574, 1456–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, T.; Soler, M.; Colomer, J. Sedimentation patterns from turbidity currents associated to hydrodynamical transport modes. Sediment. Geol. 2025, 476, 106802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindelar, C.; Gold, T.; Reiterer, K.; Hauer, C.; Habersack, H. Experimental Study at the Reservoir Head of Run-of-River Hydropower Plants in Gravel Bed Rivers. Part I: Delta Formation at Operation Level. Water 2020, 12, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, P.F.; Pereira Cabral, J.B. Caracterização hidrossedimentológica do reservatório da UHE Foz do Rio Claro (GO). Rev. Bras. Geogr. Física 2023, 16, 2782–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, N.d.O. Hidrossedimentologia Prática, 2nd ed.; Interciência: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, L.T.; Figueiredo, F.P.; Oliveira, F.G. Estimates of Volume and Sedimentation of the Reservoir of the Itacarambi River Dam, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Nativa 2016, 4, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Zuo, Z.; Yan, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, D.; Liu, C.; Yu, D. In situ remediation mechanism of internal nitrogen and phosphorus regeneration and release in shallow eutrophic lakes by combining multiple remediation techniques. Water Res. 2023, 229, 119394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, F.; Minear, J.T.; Rajagopalan, B.; Wang, C.; Yang, K.; Livneh, B. Estimating Reservoir Sedimentation Rates and Storage Capacity Losses Using High-Resolution Sentinel-Satellite and Water Level Data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2023, 50, e2023GL103524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brune, G.M. Trap Efficiency of Reservoirs; Western Oregon University: Monmouth, OR, USA, 1953; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, M.A. Analysis and use of reservoir sedimentation data. In Proceedings of the 1st Federal Interagency Sedimentation Conference, Denver, CO, USA, 6–8 May 1947; pp. 139–140. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.-C.; Lee, F.-Z. Real time response strategy for reservoir storage maintenance and desiltation operations. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collischonn, B.; Clarke, R.T. Estimativa e incerteza de curvas cota-volume por meio de sensoriamento remoto. RBRH 2016, 21, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamagate, A.; Koffi, Y.B.; Ahoussi, K.E.; Kouassi, M.A.; Ehui, H.E.; Yao, K.S.A.; Diallo, S. Sedimentary Inputs and Morphology Characterization of the Bottom Agropastoral Lake of Nafoun (North Ivory Coast). J. Water Resour. Prot. 2020, 12, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, C.d.C.; Cabral, J.B.P.; Lopes, S.M.F.; Oliveira, S.F.; da Rocha, I.R. Qualidade dos sedimentos em relação à presença de metais pesados no reservatório da usina hidrelétrica de Caçu—GO. Rev. Bras. Geogr. Física 2018, 11, 959–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, J.B.P.; Fernandes, L.A.; Becegato, V.A.; da Silva, S.A. Caracterização sedimentológica dos modelos deposicionais do reservatório de Cachoeira Dourada-GO/MG*. Geosul 2010, 26, 175–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevaux, J.C. O Rio Paraná: Geomorfogênese, Sedimentação e Evolução Quaternária do seu Curso Superior (Região de Porto Rico, PR). Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miall, A.D. Principles of Sedimentary Basin Analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.L.; Fan, J. Reservoir Sedimentation Handbook; McGraw-Hill Book Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cabral, J.B.P.; Gentil, W.B.; Ramalho, F.L.; de Barcelos, A.A.; Becegato, V.A.; Paulino, A.T. Sediments of hydropower plant water reservoirs contaminated with potentially toxic elements as indicators of environmental risk for river basins. Water 2024, 16, 2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieg. Sistema Estadual de Estatísticas Informações Geografias de Goiás. 2020. Available online: http://www.sieg.go.gov.br/siegdownloads/ (accessed on 22 November 2020).

- Fernandes, L.A. Mapa litoestratigráfico da parte oriental da bacia Bauru (PR, SP, MG), Escala 1:1.000.000 (Lithostratigraphic map of the bauru basin eastern part (PR, SP, MG), Scale 1:1.000.000). Bol. Parana. Geociênc. 2004, 55, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birro, S.O.G.; Ross, J.L.S.; Cabral, J.B.P. Analysis of environmental fragility in the area of direct influence of the Espora Hydroelectric Power Plant in Corrente river, Goiás, Brazil. J. Geogr. Spat. Plan. 2021, 22, 140–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, P.T.; Martins, A.P. Análise da Vulnerabilidade Ambiental da Bacia Hidrográfica do Rio Claro (GO) Utilizando Geotecnologias. Geogr. Dep. Univ. Sao Paulo 2018, 36, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, M.R.D.; Marcuzzo, F.F.N.; Barros, J.R. Climatic classification of Köppen-Geiger for the State of Goiás and the Federal District. Acta Geogr. 2014, 8, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.P.A.; Do Amaral, R.F.; Do Nascimento Araújo, P.V. Granulometria e morfometria de sedimentos superficiais costeiros: O complexo de lagoas interdunares da APA Jenipabu, Rio Grande do Norte, Brasil. Holos 2020, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentworth, C.K. A Scale of Grade and Class Terms for Clastic Sediments. J. Geol. 1922, 30, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, J.B.P.; de Barcelos, A.A.; Ramalho, F.L.; da Silva Gomes, P.; Nogueira, P.F.; Paulino, A.T. Eutrophication Levels of Hydropower Plant Water Reservoirs Via Trophic State Index With Evaluation of the Fate of Pollutants Affected By the Land Use Model. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2024, 235, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serbeto, L.F.; Mendes, G.; Ribeiro, C.B.d.M.; Pereira, R.d.O. Determinação da Concentração de Clorofila-a por Sensoriamento Remoto no Reservatório de Chapéu d’Úvas (Mg), Brasil. Rev. Bras. Geogr. Física 2021, 14, 3561–3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, H.S.M.; de Castro, S.S. Mapeamento e identificação de áreas críticas à erosão hídrica linear: O exemplo do bioma Cerrado no estado de Goiás, Brasil. Rev. Bras. Geomorfol 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, E.D.; Castro, S.S. Degradation of Phytophysiognomies of Cerrado and linear water erosive impacts in southwestern Goiás—Brazil. Soc. Nat. 2021, 33, e60606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasa, J.; Dostal, T.; Jachymova, B.; Bauer, M.; Devaty, J. Soil erosion as a source of sediment and phosphorus in rivers and reservoirs—Watershed analyses using WaTEM/SEDEM. Environ. Res. 2019, 171, 470–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poesen, J. Soil erosion in the Anthropocene: Research needs. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2018, 43, 64–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.N.; Mohanadhas, B. Review of the effect of river vegetation on sediment transport and river morphology and erosion prevention. ISH J. Hydraul. Eng. 2025, 31, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lintern, A.; Webb, J.A.; Ryu, D.; Liu, S.; Bende-Michl, U.; Waters, D.; Leahy, P.; Wilson, P.; Western, A.W. Key factors influencing differences in stream water quality across space. WIREs Water 2018, 5, e1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrees, A.; Bakheit Taha, A.T.; Mustafa Mohamed, A. Prediction of sustainable management of sediment in rivers and reservoirs. Chemosphere 2022, 309, 136369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Reis, R.I.; Sardinha, D.d.S. Transporte fluvial de sedimentos e nutrientes a montante do Reservatório da Hidrelétrica Caconde, bacia do Alto Rio Pardo (MG). Rev. Bras. Geogr. Física 2021, 14, 2646–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukas, P.; Melesse, A.M.; Kenea, T.T. Predicting reservoir sedimentation using multilayer perceptron—Artificial neural network model with measured and forecasted hydrometeorological data in Gibe-III reservoir, Omo-Gibe River basin, Ethiopia. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 359, 121018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estigoni, M.V.; Miranda, R.B.; Mauad, F.F. Hydropower reservoir sediment and water quality assessment. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2017, 28, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczyk, P.; Wiatkowski, M.; Gałka, B.; Gruss, Ł. Assessing the Impact of a Hydropower Plant on Changes in the Properties of the Sediment of the Bystrzyca River in Poland. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 795922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, D.; Wang, H.; Ren, Y.; Lu, T.; Bi, N.; Wu, X.; Wang, A. Modeling of the sediment transport and deposition in the Yellow River Estuary during the water-sediment regulation scheme. Catena 2025, 251, 108806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayele, G.T.; Kuriqi, A.; Jemberrie, M.A.; Saia, S.M.; Seka, A.M.; Teshale, E.Z.; Daba, M.H.; Ahmad Bhat, S.; Demissie, S.S.; Jeong, J.; et al. Sediment Yield and Reservoir Sedimentation in Highly Dynamic Watersheds: The Case of Koga Reservoir, Ethiopia. Water 2021, 13, 3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Guo, Q.; Qiqi, L.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, W. Mechanisms of fine-grained sedimentation and reservoir characteristics of shale oil in continental freshwater lacustrine basin: A case study from Chang 73 sub-member of Triassic Yanchang Formation in southwestern Ordos Basin, NW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2025, 52, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bábek, O.; Kielar, O.; Lenďáková, Z.; Mandlíková, K.; Sedláček, J.; Tolaszová, J. Reservoir deltas and their role in pollutant distribution in valley-type dam reservoirs: Les Království Dam, Elbe River, Czech Republic. Catena 2020, 184, 104251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczyk, P.; Gałka, B.; Wiatkowski, M.; Buta, B.; Gruss, Ł. Analysis of spatial distribution of sediment pollutants accumulated in the vicinity of a small hydropower plant. Energies 2021, 14, 5935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madadi, M.R. Reservoir sedimentation management: A state-of-the-art review. J. Appl. Res. Water Wastewater 2022, 2, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.