Abstract

Sewer corrosion driven by sulfur metabolism threatens infrastructure durability. Current study examined the effect of conductive lining materials on microbial communities and sulfide control under simulated sewer conditions. Three lab-scale reactors (3.5 L total volume, 2.1 L working volume) were prepared with amorphous carbon (SAN-EARTH) and magnetite-black (MTB) linings, while a Portland cement reactor with no coating served as the control. Each reactor was operated for 120 days at room temperature and fed with artificial wastewater. The working volume consisted of 1.4 L of synthetic wastewater mixed with 0.7 L of sewage sludge used as the inoculum source. Sulfate, sulfide, hydrogen sulfide, nitrogen species, pH, and organic carbon were monitored, and microbial dynamics were analyzed via 16S rRNA sequencing and functional annotation. SAN-EARTH and MTB reactors completely suppressed sulfide and hydrogen sulfide, while Portland cement showed the highest accumulation. Both conductive linings maintained alkaline conditions (pH 9.0–10.5), favoring sulfide oxidation. Microbial analysis revealed enrichment of sulfur-oxidizing bacteria (Thiobacillus sp.) and electroactive taxa (Geobacter sp.), alongside syntrophic interactions involving Aminobacterium and Jeotgalibaca. These findings indicate that conductive lining materials reshape microbial communities and sulfur metabolism, offering a promising strategy to mitigate sulfide-driven sewer corrosion.

1. Introduction

Sewer systems are essential for managing stormwater, protecting public health, and maintaining the quality of natural water bodies. Yet, many pipelines are aging or deteriorating, leading to failures such as road collapses caused by compromised structural integrity [1]. A recent incident in Saitama Prefecture, Japan, was linked to severe sewer pipe corrosion, likely exacerbated by long-term degradation and hydrogen sulfide-related damage [2]. Such events emphasize the urgent need for more effective approaches to ease sewer pipe deterioration and prevent future infrastructure failures. Globally, corrosion from sulfur-based metabolites remains one of the major contributors to the decline of sewer networks [3].

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S), one of the sulfur-based corrosive agents, is generated via the metabolic activity of sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) under anaerobic conditions [4] and has become a critical issue, leading to accelerated deterioration of sewer infrastructure and frequent road subsidence incidents [5]. This corrosion process occurs when, under anaerobic conditions, the SRB utilizes sulfate as an electron acceptor, producing sulfide species (S2−, HS−, and H2S). The volatilized H2S then diffuses into the gas phase and is oxidized by sulfur-oxidizing bacteria (SOB) in aerobic zones, forming sulfuric acid that aggressively attacks concrete surfaces [6]. Several mitigation measures to prevent sulfide and hydrogen sulfide formation have been widely developed, such as chemical dosing and pH adjustment; however, these approaches are costly and environmentally challenging [7,8]. To biochemically prevent the generation of hydrogen sulfide, there are several metabolic mechanisms and microbial interactions to transform the free sulfides: (1) utilized by the methanogens to upregulate the hdr genes, (2) conversion into L-cysteine, (3) assimilation into broader cellular metabolic processes, and (4) through direct interspecies electron transfer (DIET) between microorganisms. Previous studies have shown that certain sulfur-oxidizing bacteria (SOB), particularly those within the Thiobacillus genera, are capable of oxidizing H2S to elemental sulfur (S0 and S8) by utilizing oxygen (O2) as the terminal electron acceptor [9,10].

Recently, lining sewer pipes with conductive materials has emerged as a promising strategy to establish alternative electron transfer pathways, thereby reshaping microbial metabolism and ultimately suppressing sulfide formation [11,12]. Several studies have introduced coating methods to mitigate sewer corrosion, including the use of CaSO4·2H2O and Mg(OH)2 [13,14]. Most previous studies have assessed sewer corrosion mainly through indirect indicators such as pH variation, material degradation, and changes in mechanical properties while providing little quantitative evaluation of sulfate, sulfide, and hydrogen sulfide levels. In addition, the microbial processes governing sulfur metabolism and their interactions with different lining materials are still not well characterized.

In this study, we examined sewer pipe reactors lined with carbon-based (SAN-EARTH) and magnetite-iron-based (MTB) conductive materials to evaluate their ability to redirect electron flow, suppress sulfate reduction, stimulate syntrophic interaction between microbial communities, and strengthen microbe–material interactions [15,16]. Earlier studies reported that carbon-based linings can lower hydrogen sulfide emissions by physically adsorbing and retaining H2S within the carbon matrix, facilitating its chemical oxidation, and promoting biologically driven oxidation [12,17]. This enhanced biological oxidation is supported by Electricity-Producing Bacteria (EPB), such as Geobacter, which accelerate electron transfer processes [12,17]. The magnetite MTB lining incorporates iron, which is commonly used as an electrode material to enhance methanogenic activity by stimulating sulfide-consuming enzymatic pathways in methanogenic archaea. Moreover, Fe3+/Fe2+ redox systems have been applied for hydrogen recovery from hydrogen sulfide through electrochemical processes [18,19].

In addition to microbial sulfur transformations, abiotic processes may also contribute to sulfide and hydrogen sulfide metabolism in sewer systems. These processes include pH buffering by lining materials, adsorption of sulfide onto mineral or carbon-based surfaces, and physicochemical redox reactions that alter sulfur speciation without direct microbial involvement. Conductive materials may further support surface-mediated electron transfer and redox reactions, promoting the formation of less corrosive sulfur species. However, the relative importance of these abiotic effects compared with biologically driven processes remains largely unquantified under sewer-relevant conditions.

Despite growing interest in conductive lining materials as a strategy to mitigate sulfur-induced sewer corrosion, their mechanistic influence on microbial community structure remains insufficiently understood. In particular, direct evidence linking conductive linings to shifts in dominant functional microbial groups and sulfur metabolite suppression has not been extensively discussed. To address this gap, the present study systematically evaluates the performance of laboratory-scale sewer reactors coated with carbon-based SAN-EARTH and iron-based MTB, compared with no-coating Portland cement reactor. By integrating sulfur metabolites analysis with microbial community profiling, this work elucidates how SAN-EARTH and MTB linings, compared with conventional Portland cement, enhance sulfate, sulfide, and hydrogen sulfide removal while reshaping microbial diversity and functional interactions within the reactor environment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Operational Conditions of Lab-Scale Conductive Sewer Reactors (CRs)

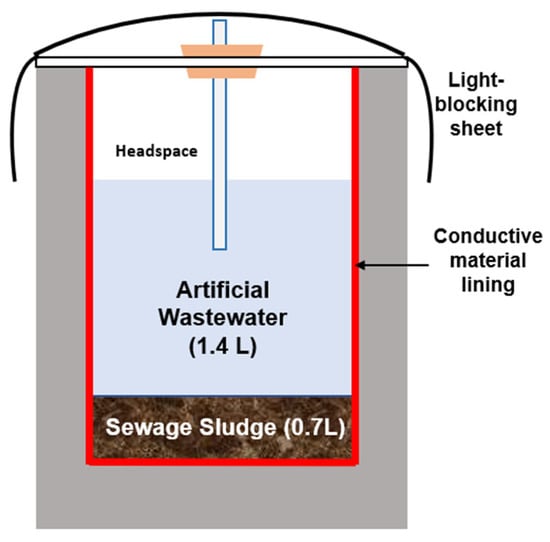

In the current study, the sewer pipe conditions were simulated using rectangular lab-scale reactors, as illustrated in Figure 1. This design was selected for its convenience, durability, and ease of construction. To simulate sewer conditions, sewage sludge was selected as the primary inoculum. The sludge was obtained from the sludge treatment facility of the Eastern Ube Wastewater Treatment Plant in Ube City, Yamaguchi Prefecture, Japan. The facility operates using an activated sludge process. The physicochemical properties of the collected sludge are presented in Table 1. A glucose-based synthetic wastewater, supplemented with essential nutrients to promote microbial growth, was prepared as the substrate with the composition as follow (all in mg/L): 2000 glucose, 20 yeast extract, 400 NaHCO3, 400 K2HPO4, 700 (NH4)2HPO4, 750 KCl, 850 NH4Cl, 420 FeCl3∙6H2O, 810 MgCl2∙6H2O, 250 Mg2SO4∙7H2O with 97 SO42−, 1.8 CoCl2∙6H2O, and 15 CaCl2∙2H2O.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the CR configuration employed in the current study.

Table 1.

Physicochemical properties of the sewage sludge used as primary inoculum.

The study employed a rectangular lab-scale conductive sewer reactor (CR) with a total volume of 3.5 L (123 mm × 123 mm × 235 mm). Three reactor configurations were prepared according to the lining material applied to the internal compartment: (1) uncoated Portland cement, (2) a 5 mm layer of amorphous carbon (SAN-EARTH, 100 wt%) supplied by Sankosha Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan), and (3) a 5 mm magnetite-based lining (MTB, 50 wt%) manufactured by Morishita Bengara Kogyo Co., Ltd. (Iga City, Japan). Each reactor operated at a working volume of 2.1 L, comprising 1.4 L of synthetic wastewater and 0.7 L of sewage sludge (Figure 1). To reduce the risk of contamination, the reactors were covered with an acrylic lid fitted with sampling ports and additionally wrapped with a black protective enclosure.

The experiment was conducted over a period of four months using a fed-batch system designed to closely replicate the organic loading conditions of sewer environments. Every 10 days, 0.2 L of fresh artificial wastewater was added to replace the same volume of spent medium, thereby sustaining microbial activity and preventing starvation. Based on findings from a previous study, a COD/sulfate ratio of 2 was identified as the optimal configuration for sulfide-based compound removal in the reactor [20,21,22]. To maintain this ratio within the desired range, Na2SO4 was supplemented accordingly.

2.2. Data Measurement and Analysis

Sulfate (SO42−) and sulfide (S2−) concentrations were regularly monitored throughout the experiment. Sulfide was quantified using the methylene blue colorimetric method, whereas sulfate was measured via the barium sulfate turbidimetric method. Both analyses were conducted using a HACH Multi-Item Rapid Water Quality Analyzer (DR/890, Central Science Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Chemical oxygen demand (COD) was determined in accordance with the Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater [23]. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) was analyzed using a cylinder-type vacuum method with a GV-100 gas sampling pump and a Gastec short-term detection tube by Gastec.co.jp. Measurements of pH, temperature, and oxidation-reduction potential (ORP) were taken using a pH meter (model D-52) and a pH/ORP meter (model D-72), both manufactured by HORIBA Advanced Techno Co., Ltd., Kyoto, Japan.

Total Organic Carbon (TOC) was measured using the TOCV-CPN (shimadzu.co.jp) with a combustion catalytic oxidation method at 680 °C, and different nitrogen species in water (NH4–N, NO2–N, NO3–N) were analyzed using an automated chemical analyzer (AA3 model, BL-Tech Co., Ltd., Chuncheon-si, Republic of Korea) with continuous flow analysis. Ammonium nitrogen (NH4–N) was quantified via the indophenol spectrophotometric method, nitrite nitrogen (NO2–N) was determined using the naphthylethylenediamine spectrophotometric method, and nitrate nitrogen (NO3–N) was analyzed by the copper–cadmium column reduction–naphthylethylenediamine spectrophotometric method. All measured parameters were analyzed in triplicate. The data obtained from the environmental parameters analysis were visualized using Microsoft Excel and the ggplot2 R packages version 4.0.0 [24]. Statistical significance (p < 0.05) was evaluated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) performed in RStudio (version 2024.12.0, Build 467). All data visualization and graphical analyses were also conducted using RStudio.

2.3. 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing and Microbial Community Analysis

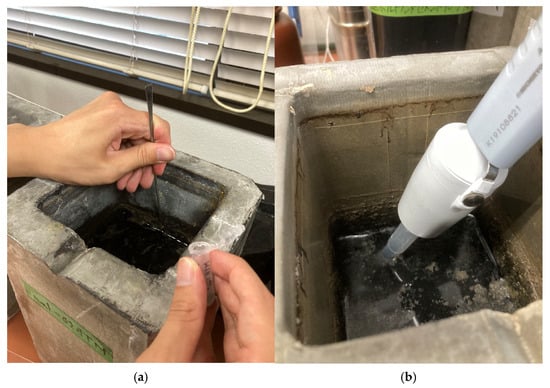

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) was conducted following the protocols described in previous studies [11,25,26]. 1.5 mL of sample was withdrawn from each CR and stored at −22 °C prior to DNA extraction. Samples were obtained from two distinct zones within each reactor, the surface and bottom layers, as shown in Figure 2a,b. Genomic DNA was extracted using the NucleoSpin® Soil Kit (MACHEREY-NAGEL GmBH & Co. KG, Düren, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA concentrations were quantified using the Qubit® dsDNA Assay Kit and measured with a Qubit® 4.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Figure 2.

Illustration of sampling points for the DNA analysis samples in the surface (a) and bottom (b) layer in each CR.

After DNA extraction, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification was performed in two sequential steps. The initial PCR amplified the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene using primers 515F and 806RC in combination with KAPA HiFi HotStart Ready Mix (TaKaRa Bio Inc., Kusatsu, Shiga, Japan). The amplified products were subsequently purified with the NucleoSpin® Gel and PCR Clean-up Kit (MACHEREY-NAGEL GmBH & Co. KG, Düren, Germany) to eliminate residual primers and primer–dimer artifacts. A second PCR was then conducted to attach dual-index barcodes and Illumina sequencing adapters using the Nextera XT v2 Index Kit (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The thermal cycling program followed that of the first PCR, with a reduced number of amplification cycles (30 cycles for the first PCR and 12 cycles for the second).

To remove unincorporated index sequences and prevent non-specific cluster formation during sequencing, the final PCR products were purified using AMPure XP beads, 10 mM Tris buffer (pH 8.5), and 80% ethanol. High-throughput sequencing was subsequently carried out on an Illumina iSeq 100 platform at the Department of Environmental Engineering, Yamaguchi University, Japan. Raw FASTQ sequence data were processed and taxonomically classified using the DRAGEN Metagenomics Pipeline with the Extended Kraken reference database.

3. Results

3.1. Reactor Performance in Removing Sulfur- and Nitrogen-Based Compounds

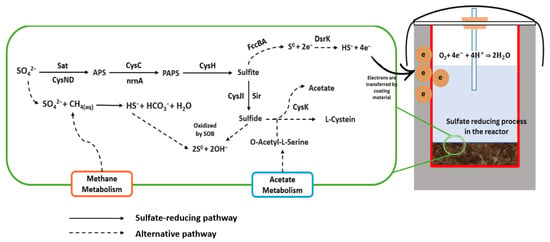

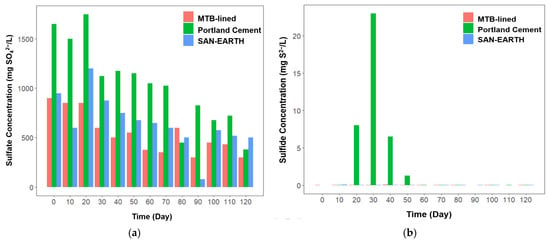

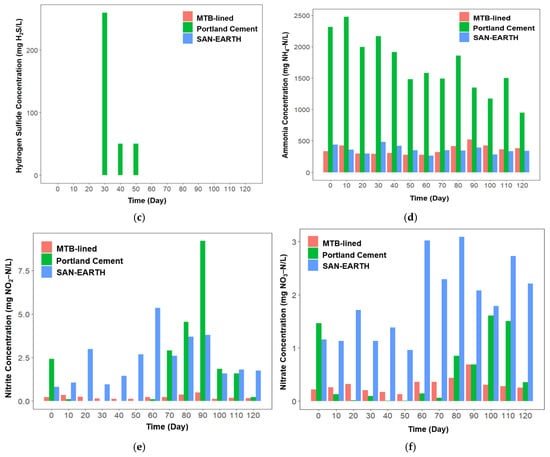

In typical sulfur metabolism pathways, sulfate is reduced by sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB), forming sulfide and hydrogen sulfide. However, as shown in Figure 3, multiple alternative metabolic routes can suppress the accumulation of these reduced sulfur species. These include the oxidation of sulfite and bisulfide to elemental sulfur, the assimilation of sulfide into L-cysteine, and the diversion of electron flow toward water formation rather than hydrogen sulfide generation. The latter pathway is likely facilitated by the presence of conductive coating layers, which provide alternative electron transfer routes and alter microbial redox processes. As shown in Figure 4a, among the sulfur-based compounds, sulfate was the most abundant species detected in all CRs.

Figure 3.

The common sulfate-reducing pathway performed by the SRBs and potential alternative pathways arise from syntrophic relationships with the other microorganisms and the presence of coating materials [11].

Figure 4.

Profile of several key environmental parameters including sulfate (a), sulfide (b), hydrogen sulfide (c), ammonia (d), nitrite (e), and nitrate (f) concentrations in three different CRs.

The Portland cement CR exhibited the highest sulfate concentration, reaching up to 1750 mg SO42−/L on day 20. In contrast, the SAN-EARTH-lined and MTB-lined CRs displayed lower maximum sulfate concentrations of 1200 mg SO42−/L and 850 mg SO42−/L, respectively, despite receiving similar sulfate intake. It took 120 days for the Portland cement-lined CR to reduce the sulfate concentration to as low as 380 mg SO42−/L, indicating the lowest sulfate removal capability among the reactors. In comparison, the SAN-EARTH-lined CR achieved a much greater reduction, lowering the sulfate concentration to 79 mg SO42−/L by day 90. On the same day, the MTB-lined CR recorded a sulfate concentration of 300 mg SO42−/L; however, this reactor consistently maintained sulfate levels below 500 mg SO42−/L from day 60 onward, with only a minor increase to approximately 600 mg SO42−/L on day 80.

In Portland cement CR, elevated sulfate concentrations were followed by increased sulfide and hydrogen sulfide production afterwards (Figure 4b,c). Portland cement CR emitted a maximum of 260 mg H2S/L and 23 mg S2−/L, both were generated on day 30. Interestingly, the SAN-EARTH-lined and MTB-lined CRs did not display similar patterns. These reactors produced insignificant amounts of sulfide and hydrogen sulfide, suggesting that sulfate may have been utilized or transformed through alternative metabolic pathways that do not generate these reduced sulfur species, potentially due to syntrophic interactions among microbial communities. The lower concentrations of sulfate, sulfide, and hydrogen sulfide observed in the SAN-EARTH (amorphous carbon)-lined and MTB (magnetite)-lined reactors suggest that these lining materials may help mitigate corrosion risks in sewer pipes associated with sulfur-based compounds.

In this study, nitrogen compounds were monitored as indicators of potential inhibition of sulfate reduction, since the SRBs and nitrifying–denitrifying bacteria compete for organic substrates as electron donors. SRBs rely on organic matter to drive the reduction in sulfate to sulfide and hydrogen sulfide, whereas nitrifying–denitrifying microorganisms utilize organic carbon during nitrogen transformations, NH4+ under anaerobic conditions, and NO2− and NO3− in the presence of oxygen [27,28,29]. In the Portland cement-lined reactor (CR), ammonia concentration rose sharply by day 10, reaching 2312 mg NH4–N/L (Figure 4d). At this point, sulfide and hydrogen sulfide concentrations remained below 0.1 mg/L, suggesting that high ammonia concentrations inhibited sulfate reduction activity. This phenomenon is consistent with previous reports indicating that sulfide production is suppressed under high ammonia conditions [30,31,32]. When the ammonia concentration decreased to below 2000 mg NH4–N/L, sulfate reduction activity increased significantly, and the production of sulfides and hydrogen sulfide increased between days 30 and 50. However, after day 40, the ammonia concentration gradually declined from approximately 2000 mg NH4–N/L to below 1000 mg NH4–N/L by the end of the experiment, accompanied by reduced sulfate levels and a diminishing level in both sulfide and hydrogen sulfide concentrations.

On the other hand, this trend did not apply to the CRs lined with SAN-EARTH and MTB. Despite low ammonia concentrations (0–500 mg NH4–N/L), hydrogen sulfide was not detected. Interestingly, significant production of nitrite and nitrate was observed in the SAN-EARTH-lined CR (Figure 4e,f). Previous studies have reported that the presence of nitrate significantly suppresses hydrogen sulfide production [33]. The amorphous carbon lining within the SAN-EARTH reactor may have promoted the nitrification process, prioritizing nitrogen conversion processes over sulfate reduction activity.

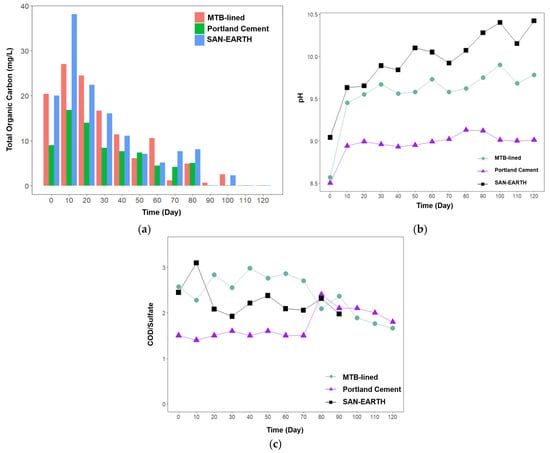

3.2. How Different Lining Materials Affect the Organic Carbon Dynamics and pH Levels

Organic carbon plays a crucial role in the removal of sulfide and hydrogen sulfide, primarily through two mechanisms: serving as an energy source for microbial processes from carbohydrate metabolism, particularly acetate metabolism, and participating in adsorption or chemical reactions within treatment systems [34]. In this study, the SAN-EARTH-lined and MTB-lined CRs exhibited higher TOC concentrations than the Portland cement-lined CR, with high organic carbon removal observed over the 120-day experimental period (Figure 5a). The SAN-EARTH-lined CR recorded the highest TOC level, reaching 38 mg/L on day 10. Although the Portland cement-lined CR showed the lowest TOC levels, which may have coincided with increased sulfide and hydrogen sulfide production, the TOC concentration remained consistently declining after day 40 without any subsequent formation of sulfide or hydrogen sulfide. As a result, no clear relationship could be established between TOC levels and the generation of sulfide or hydrogen sulfide in this study.

Figure 5.

Concentration of total organic carbon (TOC) (a) in three different CRs, along with the corresponding pH profiles (b) and COD/sulfate ratios (c).

In terms of pH profile (Figure 5b), SAN-EARTH-lined CR maintained the highest pH throughout the experiment, gradually increasing from approximately 9.1 to over 10.4. Such strongly alkaline conditions are unfavorable for hydrogen sulfide formation, as sulfide predominantly exists in its ionized forms (HS− or S2−), thereby minimizing the volatilization of hydrogen sulfide gas. Similarly, the MTB-lined CR exhibited a stable alkaline environment (pH 9.4–10.0), which likely contributed to the suppression of hydrogen sulfide release. The presence of magnetite may have provided redox buffering capacity through Fe2+/Fe3+ cycling, supporting partial oxidation of sulfide to less volatile species such as elemental sulfur or thiosulfate. In contrast, the Portland cement-lined CR maintained the lowest pH (8.5–9.2), a range more favorable for the formation and volatilization of hydrogen sulfide. This reactor also exhibited the highest sulfide and hydrogen sulfide concentrations.

The COD/sulfate profile (Figure 5c), when compared with sulfide and hydrogen sulfide concentrations, suggests that sulfide and hydrogen sulfide formation was most pronounced when the COD/sulfate ratio remained within the 1.0–1.5 range. In contrast, the higher COD/sulfate ratios observed in the SAN-EARTH and MTB reactors coincided with low sulfide and hydrogen sulfide accumulation. This decoupling implies that the SAN-EARTH and MTB linings may prevent sulfur transformations by altering electron flow or suppressing the SRB activity, thereby diverting the process away from sulfide generation and effectively mitigating sulfur-based corrosion pathways.

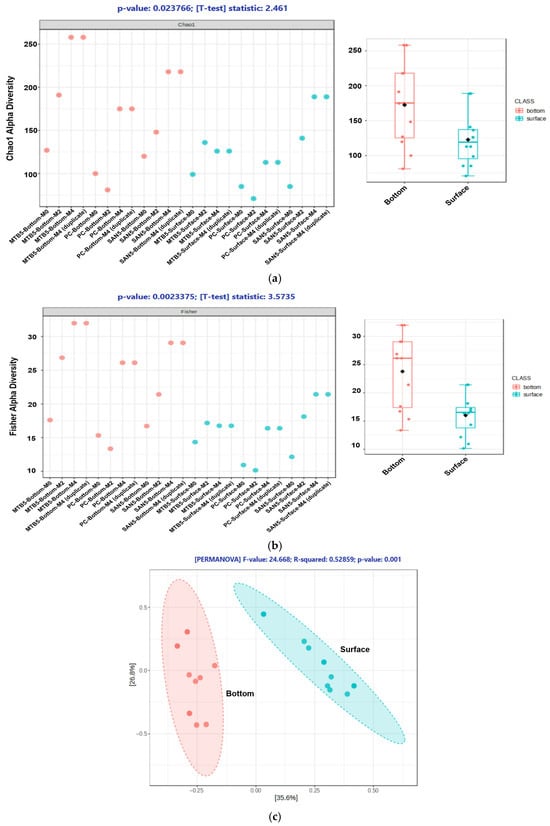

3.3. Alpha and Beta Diversity in Microbial Communities in Three Different CRs

Microbial communities play a crucial role in governing the dynamics of sulfur metabolism within the CRs. To evaluate the influence of lining materials on microbial diversity, alpha diversity analyses were performed using the Chao1 and Fisher indices, while beta diversity was assessed using Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA). The diversity assessment was conducted for two sampling zones: the bottom and the surface layers of the reactors. As shown in Figure 6a,b, both the Chao1 and Fisher indices demonstrated significantly higher microbial diversity in the bottom layer compared to the surface layer. The Chao1 index (p = 0.0238, t = 2.461) revealed a notably greater species richness in the bottom layer, while the Fisher index (p = 0.0023, t = 3.573) further confirmed higher microbial diversity and evenness at the bottom. This pattern indicates that the bottom environment provided more diverse ecological niches, likely supporting a broader range of microorganisms. In contrast, the surface layer exhibited lower richness and diversity, possibly due to more oxidative and unstable conditions that restricted the growth of strictly anaerobic or sensitive taxa. The reduced diversity at the surface zone may also reflect the dominance of a few oxygen-tolerant microorganisms.

Figure 6.

Chao1 (a) and Fisher’s Indices (b) analysis in two groups of microorganisms, followed by the PCoA analysis to elucidate the difference between the two groups (c).

The PCoA analysis (Figure 6c) further revealed a clear separation between microbial communities from the bottom and surface layers. The distant proximity between the two groups signified a strong dissimilarity between them. This dissimilarity may be the result of the different environmental stratification, such as redox potential, oxygen availability, and substrate gradients, which played a crucial role in shaping the microbiome. The bottom layer likely harbored diverse anaerobic microorganisms such as sulfate-reducing and fermentative bacteria, while the surface layer was dominated by aerobic or facultative taxa adapted to oxidative conditions. Collectively, these findings highlight the strong ecological differentiation and layer-specific microbial adaptation within the CRs.

3.4. Taxonomic Profile of the Bottom and Surface Microbiome in Three Different CRs

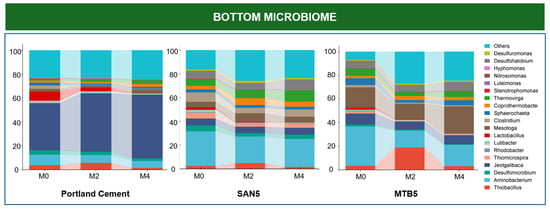

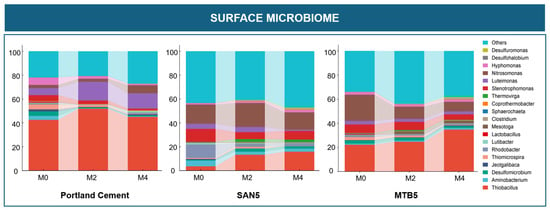

The taxonomic profiles revealed distinct microbial community structures between the surface and bottom zones across the three lining materials (Portland cement, SAN-EARTH, and MTB). Although the bottom zone exhibited higher microbial diversity in terms of both richness and evenness, it also contained a greater number of dominant strains (those exceeding 1% relative abundance across at least three conditions) compared to the surface zone. As shown in Figure 7, the bottom zone communities had a maximum of 27% of taxa categorized as “others” (observed in the MTB-lined CR during the second month of the experiment), whereas the surface microbiome showed a higher proportion of minor taxa, reaching up to 44% in the SAN-EARTH reactor at the final sampling month.

Figure 7.

Relative abundance of microbial communities in the bottom and surface zones of three corrosion CRs lined with different materials.

In the bottom microbiome of the Portland cement CR, Jeotgalibaca dominated the communities throughout the incubation period (39.45–53.35%), followed by a stable abundance of Aminobacterium around 5.92% to 8.66% and a marked decrease in Thiobacillus. Jeotgalibaca was involved in cysteine biosynthesis through sulfide degradation [35,36]. Its metabolic activity helps mitigate hydrogen sulfide formation, thereby playing a crucial role in controlling sulfur-related corrosion. Previous studies have reported a possible syntrophic relationship between Jeotgalibaca and Aminobacterium in the conversion of sulfide into L-cysteine via the O-acetyl-L-serine (OAS) electron donor pathway [11]. In this process, Aminobacterium is responsible for providing OAS, a derivative of L-serine that serves as a key electron donor for Jeotgalibaca to convert sulfide into L-cysteine and acetate. Interestingly, the abundance of Jeotgalibaca was lower in SAN-EARTH-lined CR and MTB-lined CR, where these reactors favored the growth of Aminobacterium and numerous fermentative taxa, as well as some SRB strains.

In the SAN-EARTH-lined CR, Aminobacterium accounted for approximately 23–29% of the total microbial community. Interestingly, an increasing abundance of Clostridium and Thermovirga was also observed in this reactor. Members of the genus Clostridium are widely recognized for their role in reducing various sulfur compounds, such as sulfite, thiosulfate, elemental sulfur, and polysulfide, into sulfide via the dissimilatory sulfite reduction pathway in the same way as the SRBs [37,38]. Likewise, Thermovirga is known to produce sulfide via the reduction of elemental sulfur and thiosulfate [39]. However, despite the presence of these potential sulfide-producing bacteria, no detectable sulfide or hydrogen sulfide was observed in the SAN-EARTH-lined CR.

In addition, the MTB-lined CR favored the growth of Mesotoga, which prevailed up to 22.89% of the total microbial communities. This strain is known as a notable hydrogen producer and electron donor in the presence of an iron-based electrode [40,41]. Desulfohalobium was found as the most abundant SRB identified in this study, along with Thiobacillus. Previous studies have demonstrated the ability of Thiobacillus spp. to oxidize sulfide into elemental sulfur [9,42]. As a sulfur-oxidizing bacterium (SOB), Thiobacillus harbors multiple sulfur-metabolism genes that enable bidirectional sulfur transformations, allowing both the oxidation of sulfide to elemental sulfur and, under certain conditions, the reverse process of sulfide generation from thiosulfate degradation [43]. This characteristic may suggest a possible syntrophic relationship between Thiobacillus and Desulfohalobium, where the former may recycle sulfide produced by the latter into less harmful intermediates such as elemental sulfur.

In the surface microbiome, the dominant taxa differed markedly from those observed in the bottom layer. Thiobacillus emerged as the most abundant genus across all materials, particularly in the Portland cement reactor, where its relative abundance exceeded 40%. Luteimonas also showed notable enrichment in M0, M2, and M4 (5.97%, 15.77%, and 12.87%, respectively), suggesting enhanced sulfur metabolism in these treatments. In contrast, its abundance was considerably lower in the SAN-EARTH-lined and MTB-lined CRs. The surface zone further favored the proliferation of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria such as Nitrosomonas, which reached relative abundances of up to 20% in the SAN-EARTH-lined CR and 21% in the MTB-lined CR, likely contributing to the suppression of SRB activity in this layer.

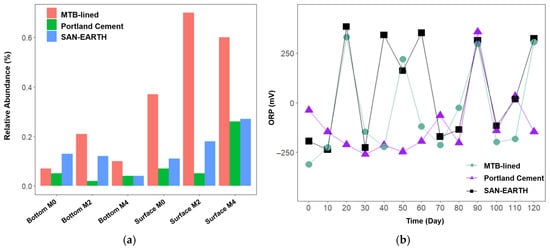

An interesting finding in this study is the gradual increase in the abundance of Geobacter in both SAN-EARTH-lined and MTB-lined CRs, despite not being among the top 1% of dominant taxa. In the MTB-lined CR, Geobacter abundance in the bottom layer increased from 0.07% to 0.21% within two months (Figure 8a), while, in the surface layer, it rose from 0.37% to 0.70% during the same period and stabilized around 0.6% by the fourth month. This pattern suggests that Geobacter favors the surface layer, likely due to its higher redox potential and partial oxygen availability that support extracellular electron transfer (EET) activity.

Figure 8.

Relative abundance of Geobacter (a) and the ORP level observed during experiments in each CR (b).

The presence of Geobacter in both SAN-EARTH- and MTB-lined CRs corresponded with an increase in oxidation–reduction potential (ORP), indicating enhanced redox activity and promoting oxidative processes within the systems. In contrast, the Portland cement CR showed consistently low Geobacter abundance during the first two months, followed by a sharp increase in the surface layer, coinciding with a notable spike in ORP (Figure 8b). This correlation indicates that Geobacter may play a significant role in promoting oxidation reactions within the CRs, especially in the MTB-lined CR (Pearson Correlation = 0.88, ANOVA p = 0.00443). The more positive ORP values reflect stronger oxidative conditions with a higher tendency to accept electrons, thereby facilitating the transfer of electrons from sulfide, which is subsequently oxidized to elemental sulfur. This mechanism highlights the contribution of Geobacter to sulfide removal and the stabilization of redox balance within the CRs.

4. Discussion

The current study highlights the potential reduction of sulfur-based metabolic activity, responsible for corrosion in sewer pipes, through the use of amorphous carbon (SAN-EARTH) and iron-based (MTB) lining materials, in comparison to conventional Portland cement reactors. Past studies have explored protective coatings to control sewer corrosion, including formulations based on CaSO4·2H2O and Mg(OH)2 [13,14]. However, most of these efforts have assessed performance mainly through abiotic indicators such as pH changes, surface degradation, and alterations in concrete strength or hardness while giving limited attention to sulfur species dynamics, including sulfate, sulfide, and hydrogen sulfide. In addition, the microbial community structure and metabolic processes governing sulfide transformation under different coating materials remain insufficiently characterized.

The current research serves as a continuation of our previous study, which investigated the use of MTB, SAN-EARTH, and nickel lining layers to reduce the production of sulfate, sulfide, and hydrogen sulfide [11,12]. The current study demonstrated improved performance, particularly in the SAN-EARTH-lined and MTB-lined CRs, where no noticeable concentrations of sulfide and hydrogen sulfide were detected throughout the experiment. This performance was achieved in the pH range of 9.0–10.5, which is considered ideal for hydrogen sulfide removal in the sewer system. Previous studies suggest that maintaining a pH above 7.5, depending on the material composition and surrounding environmental conditions, creates an ideal environment for the removal of hydrogen sulfide and sulfate [44,45]. At low pH, hydrogen sulfide predominantly exists in its molecular form, which is highly corrosive and volatile. As the pH increases, hydrogen sulfide gradually dissociates into its ionic forms, bisulfide and sulfide, with bisulfide becoming the dominant species under mildly alkaline conditions (pH > 8). In the current study, the SAN-EARTH-lined and MTB-lined CRs maintained relatively higher and more stable pH values, which likely suppressed the formation of molecular hydrogen sulfide and contributed to the observed reduction in sulfide and hydrogen sulfide accumulation compared to the Portland cement CR.

Interestingly, our previous study also identified the dominance of Aminobacterium, Jeotgalibaca, and Thiobacillus, whose syntrophic interactions were found to suppress sulfide and hydrogen sulfide formation by converting them into L-cysteine and, potentially, elemental sulfur. In contrast to our results, the earlier study observed a pronounced enrichment of methanogenic archaea, microorganisms that can participate in hydrogen sulfide turnover. These methanogens primarily use hydrogen as an electron donor, while sulfur species have been shown to induce the expression of heterodisulfide reductase (hdr) genes, thereby promoting the conversion of methyl-CoM to the CoM–S–S–CoB heterodisulfide, a critical step in methanogenesis [46,47]. Accordingly, hydrogen sulfide in the previous system likely enhanced methanogenic activity by supporting key cofactors involved in energy conservation and metabolic control, whereas sulfide depletion in the present system likely constrained the activation of these pathways.

In the current finding, instead of aiding the growth of methanogens, the presence of iron in the MTB lining appears to stimulate the growth of Geobacter, a genus known for its versatile electron transfer capabilities. Geobacter species play a crucial role in sulfide removal by potentially serving as electron-donating partners through direct interspecies electron transfer (DIET) or by transferring electrons directly to electrodes [15,48], in this case, the magnetite iron materials in the MTB layers. These microorganisms facilitate the anaerobic oxidation of sulfide and related sulfur compounds produced by other bacteria, thereby contributing to sulfur cycling and the mitigation of sulfide accumulation [15,16,48]. Functionally, Geobacter acts as a central electron transfer hub, utilizing its extracellular electron transfer (EET) mechanisms, including conductive nanowires and outer membrane cytochromes, to efficiently shuttle electrons to syntrophic partners or terminal electron acceptors [49,50]. This mechanism highlights the potential role of iron-influenced environments in promoting electroactive microbial communities that enhance sulfide oxidation and stabilize reactor performance.

Geobacter was predominantly abundant in the surface zones of MTB-lined CR, likely due to its exoelectrogenic nature, which requires the cells to remain in close proximity or direct contact with conductive surfaces (electrodes) to facilitate efficient extracellular electron transfer [51,52,53]. Similarly, Thiobacillus was also found to be abundant in the surface sampling zone in both SAN-EARTH-lined and MTB-lined CRs. Many Thiobacillus species are facultative aerobes, utilizing oxygen as the terminal electron acceptor to oxidize reduced sulfur compounds, such as sulfide, into elemental sulfur [54,55,56]. The relatively higher availability of hydrogen sulfide in the surface layer provided an essential energy source for these bacteria, further supporting their proliferation and metabolic activity in this zone.

Overall, the SAN-EARTH-lined and MTB-lined CRs demonstrated outstanding performance in mitigating the formation of sulfur-based metabolites, which are the primary contributors to sewer corrosion. This effectiveness can be attributed to the syntrophic interactions among microbial consortia inhabiting both the bottom and surface zones of the reactors. While the current study highlights the potential of conductive lining materials to mitigate sulfide-driven corrosion under controlled laboratory conditions, future work should include replicated reactor systems and expanded datasets as the technology becomes more affordable and widely available. In addition, pilot to field scale observation, extended durability evaluation, and the development of next-generation conductive materials will be essential to confirm durability and practical applicability in real sewer environments.

In addition, despite the current study manage to explain the interaction between microbial communities and its associated impact on sulfide and hydrogen sulfide suppression, it should be acknowledged that the alternative sulfur transformation pathways and syntrophic interactions proposed in this study are inferred primarily from reactor performance trends and microbial taxonomic profiles, rather than from direct quantification of sulfur fluxes or measurement of intermediate sulfur species such as elemental sulfur (S0) or thiosulfate. Although the observed suppression of sulfide and hydrogen sulfide strongly suggests redirection of sulfur metabolism, the absence of sulfur mass balance analysis limits definitive confirmation of the underlying biochemical mechanisms.

Similarly, the functional roles attributed to key microbial taxa, including Jeotgalibaca, Aminobacterium, Clostridium, Thermovirga, Mesotoga, Desulfohalobium, and Thiobacillus, are derived from established metabolic capabilities reported in previous studies and genome-based annotations from other environmental systems, rather than from direct functional measurements within the present reactors. These interpretations, therefore, represent indirect, taxonomy-based functional inferences. Future investigations integrating sulfur speciation, flux analysis, and meta-transcriptomics or targeted functional genes quantification approaches would be valuable to validate these proposed metabolic interactions and syntrophic relationships under conductive lining conditions.

5. Conclusions

The present study investigated the effectiveness of SAN-EARTH carbon lining and MTB lining in mitigating sewer corrosion by suppressing sulfide and hydrogen sulfide formation. The results revealed that the uncoated Portland cement CR exhibited the highest concentrations of sulfate, sulfide, and hydrogen sulfide, while both the MTB-lined and SAN-EARTH-lined CRs showed markedly lower sulfate levels and achieved complete removal of sulfide and hydrogen sulfide. The decent performance of the SAN-EARTH-lined and MTB-lined CRs was followed by an increasing abundance of Thiobacillus, a strong sulfide oxidizer, and Geobacter, which acts as a central hub for electron transfer through direct interspecies electron transfer (DIET) or by donating electrons directly to electrodes, thereby facilitating anaerobic oxidation of sulfide and related sulfur compounds. In the bottom zone, synergistic interactions among Aminobacterium (OAS producer), Jeotgalibaca (L-cysteine producer), and Thiobacillus (sulfur-oxidizing bacteria, SOB) further supported sulfur compound degradation. These findings underscore the crucial role of conductive materials in preventing the formation of sulfur-based metabolites, demonstrating strong potential for practical implementation in real-scale sewer pipe systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.W. and T.I.; Methodology, M.W. and G.A.W.S.; Software, G.A.W.S.; Validation, M.W. and T.I.; Formal analysis, M.W. and G.A.W.S.; Investigation, M.W., G.A.W.S., S.N., S.M., and N.K.; Resources, T.I.; Data curation, M.W., S.N., S.M., and N.K.; Writing—original draft preparation, M.W.; Writing—review and editing, M.W., G.A.W.S., and T.I.; Visualization, G.A.W.S.; Supervision, T.I.; Project administration, T.I.; Funding acquisition, T.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by JST NEXUS, Japan Grant Number JPMJNX25B2.

Data Availability Statement

The raw DNA sequencing data generated and analyzed in this study are publicly available in the NCBI repository under BioProject ID PRJNA1390970.

Acknowledgments

Additionally, the authors are grateful to the Collaborative Research Center, National Institute of Technology, Ube College, for providing the use of the TOCV-CPN and AA3 analytical instruments. During the preparation of this manuscript, Microsoft Copilot (GPT-5 model) was used to assist in drafting text and refining language. The authors reviewed and edited all AI-generated content and take full responsibility for the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kuliczkowska, E. The Interaction between Road Traffic Safety and the Condition of Sewers Laid under Roads. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2016, 48, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togo, T. Decayed Sewer Pipes Found Under Roads at 3 Sites in Saitama. Available online: https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/15626136 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Pikaar, I.; Sharma, K.R.; Hu, S.; Gernjak, W.; Keller, J.; Yuan, Z. Reducing Sewer Corrosion through Integrated Urban Water Management. Science 2014, 345, 812–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suyasa, W.B.; Sudiartha, G.A.W.; Pancadewi, G.A.S.K. Optimization of Sulphate-Reducing Bacteria for Treatment of Heavy Metals-Containing Laboratory Wastewater on Anaerobic Reactor. Pollution 2022, 9, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M. Current Status and Issues of Sewerage. J. Environ. Conserv. Eng. 2024, 53, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, T.I.; Rallapalli, S.; Singhal, A.; Robert, D.; Kodikara, J.; Pramanik, B.K.; Arya, S.B. Compounded Fuzzy Entropy-Based Derivation of Uncertain Critical Factors Causing Corrosion in Buried Concrete Sewer Pipeline. npj Clean Water 2025, 8, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Gutierrez, O.; Yuan, Z. The Strong Biocidal Effect of Free Nitrous Acid on Anaerobic Sewer Biofilms. Water Res. 2011, 45, 3735–3743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, O.; Sudarjanto, G.; Ren, G.; Ganigué, R.; Jiang, G.; Yuan, Z. Assessment of PH Shock as a Method for Controlling Sulfide and Methane Formation in Pressure Main Sewer Systems. Water Res. 2014, 48, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, A.J.H.; Lettinga, G.; de Keizer, A. Removal of Hydrogen Sulphide from Wastewater and Waste Gases by Biological Conversion to Elemental Sulphur: Colloidal and Interfacial Aspects of Biologically Produced Sulphur Particles. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 1999, 151, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, W. Biogas Cleaning and Upgrading. In Biogas Technology; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2020; pp. 201–243. ISBN 978-981-15-4940-3. [Google Scholar]

- Sudiartha, G.A.W.; Imai, T. Harnessing Conductive Materials to Reshape Sewer Microbiomes and Mitigate Corrosion from Sulfide and Hydrogen Sulfide Formation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, H.T.; Imai, T.; Fukushima, M.; Promnuan, K.; Suzuki, T.; Sakuma, H.; Hitomi, T.; Hung, Y.-T. Enhancing the Biological Oxidation of H2S in a Sewer Pipe with Highly Conductive Concrete and Electricity-Producing Bacteria. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moa, J.P.S.; Gaw, B.A.C.; Co, J.L.O.; Coo, K.A.C.; Elevado, K.J.T.; Roxas, C.L.C. Performance of Seawater-Derived Mg(OH)2 as a Sustainable Coating Solution for Hydrogen Sulfide-Induced Corrosion Mitigation in Concrete Pipes. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2025, 24, 100872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merachtsaki, D.; Tsardaka, E.-C.; Anastasiou, E.K.; Yiannoulakis, H.; Zouboulis, A. Comparison of Different Magnesium Hydroxide Coatings Applied on Concrete Substrates (Sewer Pipes) for Protection against Bio-Corrosion. Water 2021, 13, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Ying, X.; Zhao, N.; Yu, S.; Zhang, X.; Feng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, H. Interspecies Electron Transfer between Geobacter and Denitrifying Bacteria for Nitrogen Removal in Bioelectrochemical System. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 455, 139821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Wang, X.; Lin, T.-Y.; Kim, J.; Liu, W.-T. Disentangling the Syntrophic Electron Transfer Mechanisms of Candidatus Geobacter Eutrophica through Electrochemical Stimulation and Machine Learning. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, T.; Vo, H.T.; Fukushima, M.; Suzuki, T.; Sakuma, H.; Hitomi, T.; Hung, Y.-T. Application of Conductive Concrete as a Microbial Fuel Cell to Control H2S Emission for Mitigating Sewer Corrosion. Water 2022, 14, 3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Tang, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, C.; Chen, J. Enhancing Electricity-Driven Methanogenesis by Assembling Biotic-Abiotic Hybrid System in Anaerobic Membrane Bioreactor. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 391, 129945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Shang, J.; Yu, Y.; Chung, K.H. Recovery of Hydrogen from Hydrogen Sulfide by Indirect Electrolysis Process. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2019, 44, 5108–5113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Matsunaga, S.; Nakamura, S.; Imai, T. 導電材をライニングした下水管による 硫化物の発生抑制に関する研究 [Development of Technology for Suppressing Hydrogen Sulfide Generation in Sewer Pipes Using Conductive Concrete]. Japan Soc. Precis. Eng. 2025, 1, 1–9. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, T.-Y.; Cha, G.-C.; Seo, Y.-C.; Jeon, C.; Choi, S.S. Effect of COD/Sulfate Ratios on Batch Anaerobic Digestion Using Waste Activated Sludge. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2008, 14, 693–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, A.; Ramírez, M.; Volke-Sepúlveda, T.; González-Sánchez, A.; Revah, S. Evaluation of Feed COD/Sulfate Ratio as a Control Criterion for the Biological Hydrogen Sulfide Production and Lead Precipitation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 151, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APHA; AWWA; WEF. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2005.

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sudiartha, G.A.W.; Imai, T.; Reungsang, A. Syntrophic Relationship among Microbial Communities Enhance Methane Production during Temperature Transition from Mesophilic to Thermotolerant Conditions. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 114903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudiartha, G.A.W.; Imai, T.; Mamimin, C.; Reungsang, A. Effects of Temperature Shifts on Microbial Communities and Biogas Production: An In-Depth Comparison. Fermentation 2023, 9, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Wang, J. Effect of Sulfate Reduction in Sulfur-Based Mixotrophic Denitrification Process: Positive or Negative? Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 514, 163330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto-Ikemoto, R.; Matsui, S.; Komori, T.; Bosque-Hamilton, E.J. Symbiosis and Competition among Sulfate Reduction, Filamentous Sulfur, Denitrification, and Poly-P Accumulation Bacteria in the Anaerobic-Oxic Activated Sludge of a Municipal Plant. Water Sci. Technol. 1996, 34, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Yang, G.; Sun, X.; Li, B.; Tian, Z.; Niu, X.; Cheng, J.; Feng, L. Simultaneous Denitrification and Organics Removal by Denitrifying Bacteria Inoculum in a Multistage Biofilm Process for Treating Desulfuration and Denitration Wastewater. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 388, 129757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanbani Veshareh, M.; Nick, H.M. A Sulfur and Nitrogen Cycle Informed Model to Simulate Nitrate Treatment of Reservoir Souring. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzenos, C.A.; Kalamaras, S.D.; Economou, E.-A.; Romanos, G.E.; Veziri, C.M.; Mitsopoulos, A.; Menexes, G.C.; Sfetsas, T.; Kotsopoulos, T.A. The Multifunctional Effect of Porous Additives on the Alleviation of Ammonia and Sulfate Co-Inhibition in Anaerobic Digestion. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Hu, C.; Zhang, D.; Dai, L.; Duan, N. Impact of a High Ammonia-Ammonium-PH System on Methane-Producing Archaea and Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria in Mesophilic Anaerobic Digestion. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 245, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, N.; Hu, D.; Liang, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, X. Unveiling the Intrinsic Relationship between Ammonia and Hydrogen Sulfide Generation during Composting. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 39, 104298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanjanarong, J.; Giri, B.S.; Jaisi, D.P.; Oliveira, F.R.; Boonsawang, P.; Chaiprapat, S.; Singh, R.S.; Balakrishna, A.; Khanal, S.K. Removal of Hydrogen Sulfide Generated during Anaerobic Treatment of Sulfate-Laden Wastewater Using Biochar: Evaluation of Efficiency and Mechanisms. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 234, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Li, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zheng, S.; Wu, Y.; Xuan, R.; Wu, L.; Miao, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Structural Characteristics of Intestinal Microbiota of Domestic Ducks with Different Body Sizes. Poult. Sci. 2025, 104, 104930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, K.; Liu, L.; Wu, N.; Cheng, D.; Shao, J.; He, J.; Shen, Q. Jeotgalibaca Caeni Sp. Nov., Isolated from Biochemical Tank Sludge. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2023, 73, 006116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, Y.; Suto, K.; Inoue, C. Polysulfide Reduction by Clostridium Relatives Isolated from Sulfate-Reducing Enrichment Cultures. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2010, 109, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, A.-R.; Bonde, G.J. The Availability of Sulphur for Clostridium Perfringens and an Examination of Hydrogen Sulphide Production. Microbiology 1957, 16, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahle, H.; Birkeland, N.-K. Thermovirga Lienii Gen. Nov., Sp. Nov., a Novel Moderately Thermophilic, Anaerobic, Amino-Acid-Degrading Bacterium Isolated from a North Sea Oil Well. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2006, 56, 1539–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, S.; Koutsokeras, L.; Constantinou, M.; Majzer, R.; Markiewicz, J.; Siedlecki, M.; Vyrides, I.; Constantinides, G. Microbial Electrosynthesis Inoculated with Anaerobic Granular Sludge and Carbon Cloth Electrodes Functionalized with Copper Nanoparticles for Conversion of CO2 to CH4. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Qu, Y.; Qi, Q.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Tong, Y.W.; He, Y. The Bio-Chemical Cycle of Iron and the Function Induced by ZVI Addition in Anaerobic Digestion: A Review. Water Res. 2020, 186, 116405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, S.K.; Khan, A.; Rao, T.S. Chapter 22—Microbial Fouling in Water Treatment Plants. In Microbial and Natural Macromolecules; Das, S., Dash, H.R., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 589–622. ISBN 978-0-12-820084-1. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, T.; Kojima, H.; Fukui, M. Complete Genomes of Freshwater Sulfur Oxidizers Sulfuricella Denitrificans SkB26 and Sulfuritalea Hydrogenivorans Sk43H: Genetic Insights into the Sulfur Oxidation Pathway of Betaproteobacteria. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 37, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathnayake, D.; Bal Krishna, K.C.; Kastl, G.; Sathasivan, A. The Role of PH on Sewer Corrosion Processes and Control Methods: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 782, 146616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, A.H.; Hvitved-Jacobsen, T.; Vollertsen, J. Effects of PH and Iron Concentrations on Sulfide Precipitation in Wastewater Collection Systems. Water Environ. Res. 2008, 80, 380–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulo, L.M.; Ramiro-Garcia, J.; van Mourik, S.; Stams, A.J.M.; Sousa, D.Z. Effect of Nickel and Cobalt on Methanogenic Enrichment Cultures and Role of Biogenic Sulfide in Metal Toxicity Attenuation. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spietz, R.L.; Payne, D.; Boyd, E.S. Methanogens Acquire and Bioaccumulate Nickel during Reductive Dissolution of Nickelian Pyrite. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 89, e00991-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.; Wang, S.; Wu, S. Electron Transfer in the Biogeochemical Sulfur Cycle. Life 2024, 14, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, T.C.; Silva, M.A.; Morgado, L.; Dantas, J.M.; Salgueiro, C.A. Diving into the Redox Properties of Geobacter Sulfurreducens Cytochromes: A Model for Extracellular Electron Transfer. Dalt. Trans. 2015, 44, 9335–9344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toshiyuki, U. Cytochromes in Extracellular Electron Transfer in Geobacter. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e03109-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Han, X.; Shan, Y.; Li, F.; Shi, L. Biofilm Biology and Engineering of Geobacter and Shewanella Spp. for Energy Applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 786416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejedor-Sanz, S.; Fernández-Labrador, P.; Hart, S.; Torres, C.I.; Esteve-Núñez, A. Geobacter Dominates the Inner Layers of a Stratified Biofilm on a Fluidized Anode During Brewery Wastewater Treatment. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bond, D.R.; Lovley, D.R. Electricity Production by Geobacter Sulfurreducens Attached to Electrodes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 1548–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, J.R.; Cardon, H.; Montagnac, G.; Picard, A.; Daniel, I. Pressure Effects on Sulfur-Oxidizing Activity of Thiobacillus Thioparus. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2021, 13, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaeffer, W.I.; Holbert, P.E.; Umbreit, W.W. ATTACHMENT OF THIOBACILLUS THIOOXIDANS TO SULFUR CRYSTALS. J. Bacteriol. 1963, 85, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, D.; Börje, L.E. Potential Role of Thiobacillus Caldus in Arsenopyrite Bioleaching. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.