1. Introduction

Floods pose a significant threat to public safety, causing important loss in terms of casualties. The majority of flood-related deaths are associated with vehicle incidents in urban environments [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Due to the constant increase in urban populations and growing apprehension about climate change [

10], vehicles are identified as one of the most aggravating factors in urban flooding [

11,

12]. They may become debris when they lose their stability, or traps for users causing accidents, and they can even augment the damage to infrastructure and buildings [

13], as well as traffic disruptions [

14]. Vehicles can lose stability as a result of losing traction or become buoyant in floodwaters, making them susceptible to being swept away and turning into debris. Emergency response services had to deploy considerable resources to rescue individuals trapped in their vehicles due to flooding [

15]. Between 1997 and 2019, many countries reported a high rate of vehicle damage related to flooding: 48.5% of deaths in Australia, over 63% in the United States, and dozens of fatalities and damaged vehicles in Greece and Iran [

5,

16,

17,

18,

19]. These data highlight the seriousness and vulnerability of cars to flood hazards. These findings emphasize the vulnerability of vehicles to flooding and the need to better understand the mechanisms driving vehicle instability in floodwaters.

Hazards associated with urban stationary cars in floodwater rely on their critical threshold of stability, which is conventionally assessed through water depth and velocity. The stability limits of vehicles have been explored by many scientists based on laboratory experiments [

20,

21,

22,

23]. This enables the design of some bilinear curves that express the relationship between flood depth and its velocity for specific vehicles. These threshold curves allow researchers to distinguish, depending on the intensity of the hydraulic variables applied to vehicles, between stable zones, where the vehicles remain insensitive to oscillations, transition zones, marked by a moderate influence of the flow, and unstable zones, where the hydrodynamic conditions seriously compromise their stability. Among these studies, we can cite the most well-known ones, starting with Refs. [

24,

25,

26], which introduced instability thresholds characterized by a linear correlation between the water depth and flow velocity in the subcritical regime, and by their product in a supercritical regime. Model development relied on laboratory experiments carried out on old car models that have different characteristics compared to recent ones; thus, the outcomes of these studies may not remain relevant as of now [

14].

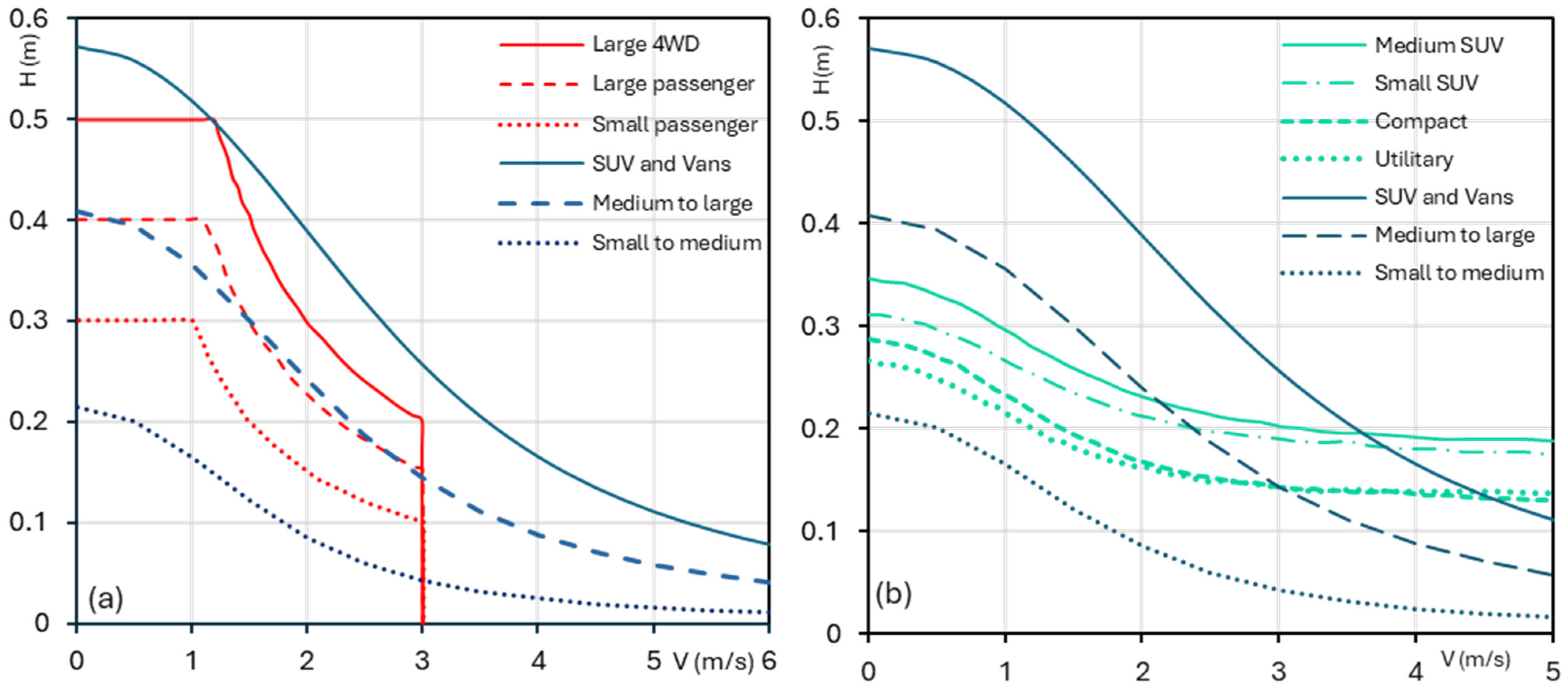

After a period of stagnation in the literature between 1993 and 2010, interest in this issue resurfaced after 2011, with diverse theoretical and experimental studies. For instance, Ref. [

27] introduced a draft of a stability threshold for static vehicles by classifying cars into small passenger, large 4WD, and large passenger according to their physical characteristics. Buoyancy limits were defined at 0.5 m of maximum depth for large 4WD vehicles; for large passenger vehicles, 0.4 m; and for small passenger vehicles, 0.3 m depth. On the other hand, 3.0 m/s was the maximum velocity for all vehicles. Afterward, Ref. [

28] introduced a formula for the incipient velocity of fully submerged vehicles, validated by experimental data obtained under real conditions. Shu et al. [

29] proposed a mechanics-based criterion for partially submerged vehicles, using flume tests to determine stability thresholds. In Ref. [

30], a new experiment on two car models were conducted, using flow orientations of 90° and 180° to validate Shu’s stability formula. Smith et al. [

15] developed a stability threshold for two car categories: small passenger and large 4WD type of vehicles, with a maximum limit velocity flow of 2.0 m/s.

Based on an alternative stability definition, Kramer et al. [

31] conducted several laboratory experiments and developed a curve closer to the curve of constant total energy head. A stability threshold equal to the total energy of the water was identified, and a constant value equivalent to the minimum wading depth was assigned to it, depending on the studied vehicle. Claiming that the stability does not depend on the orientation of the car when the Froude number is small, and buoyancy forces take control over the circumstances, for a higher Froude number, the flow angle becomes significant in the instability mechanism (sliding). Additional stability thresholds were defined by Smith et al. [

15], who conducted several tests on a full-scale small passenger (Toyota Yaris Sedan) and a large 4WD based on the product of water depth and flow velocity for every single car. One of the most important and powerful studies in the literature, undertaken by Ref. [

21], tested 12 physical car models using three different scales (1:14, 1:18, and 1:24). According to these measurements, a stability function was defined. It enabled obtaining a curve related to each type of vehicle. This curve has defined instability areas based on friction coefficient values as well. While the authors, as mentioned earlier, have worked on parked vehicles, more recently, Refs. [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36] have drawn attention to the importance of studying the stability of moving vehicles by conducting experiments and modelling insights to understand the dynamic conditions of destabilization better.

Empirical thresholds, obtained from experimental studies representative of specific vehicles, have been developed to characterize their instability in flood conditions (i.e., water level and velocity). Nevertheless, these thresholds are most often based on limited experimental data, which compromises their generalizability to all existing vehicle typologies [

37]. To expand this framework, multiparametric conceptual models have been proposed instead, integrating both vehicle geometry and the forces to which it is subjected, such as drag, buoyancy, weight, and lift. These models are often calibrated using data specific to a given vehicle, which limits their ability to represent the diversity of possible configurations. In addition, up to now, only a few experimental studies on the incipient instability conditions of small-scale vehicles have been conducted [

12,

13,

27,

28,

29,

30,

38]. Therefore, research on vehicle instability in floodwater in general remains limited [

39]. In order to overcome these limitations inherent in the classical dimensional approach, a new generation of approaches that take into account the specifics of cars’ physical properties and hydraulic conditions was implemented firstly in Ref. [

38], which developed an equilibrium model formulated using a dimensionless variable and validated with 3D modelling. Similarly, Lazzarin et al. [

23] introduced an interesting formula based on energy per unit weight and momentum per unit width and weight that can be flexible, applicable, and transferable for pedestrian cars and buildings.

To move beyond current findings in this line of research, this paper aims to develop a new criterion that stands out by generalizing the conventional criteria, focusing only on a single aspect that can predict and identify critical instability thresholds for vehicles exposed to free-surface flows, taking into account the interaction between hydrodynamic condition effects and the physical characteristics of vehicles (i.e., weight, shape, area of the planform). These are modeled through an integrative formula, providing a synthetic and coherent representation of their dynamic coupling. Moreover, the different contributions of the hydrodynamic forces and the influence of the flow regime on the mechanism of the onset of motion are analyzed. This model thus aims to allow a more flexible and interoperable transposition of results by freeing itself from contextual specificities linked to the geometric characteristics of vehicles or specific hydraulic conditions. This is done to introduce a hazard criterion for packed cars in inundated urban areas relevant for implementation in flood mapping.

This work is organized as follows:

Section 1 introduces the work, the literature and the aim of the research.

Section 2 describes the new criterion development, calibration, and estimation of parameter values.

Section 3 presents the results of the work, where the thresholds are presented and a comparative analysis is carried out with regard to previous studies to emphasize the performance of the new criterion. In

Section 4, the work is discussed, pointing out its contribution, strength, limitations, and future work.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. A New Hazard Criterion for Vehicle Instability

In order to assess the hazard of vehicle instability in flood waters, it is important to quantify the intensity of flow conditions that produce the instability, taking into account the submerged object characteristics. According to the principles of free-surface flow hydraulics, the total thrust exerted by a moving current is given by the sum of the hydrostatic and hydrodynamic thrust. Hydrostatic thrust is related to the pressure exerted by the water column on the submerged surface of the object. It depends on the area of the submerged section, as well as the vertical position of its center of gravity relative to the substrate. This force can be expressed as S

h = ƔAh

b. Hydrodynamic thrust, on the other hand, results from the interaction between the moving flow and the exposed lateral surface of the object. It is mainly a function of the fluid density, the flow discharge, and the flow velocity. It can be expressed as S

d = ρQV. For a cross section of any shape, the equation can be written as follows:

where S and Q are the water thrust and discharge per unit width (i.e., specific discharge), Ɣ= ρ.g is the specific weight of water, ρ is the water density, g is the acceleration by gravitation. For a rectangular section, we can write:

In order to highlight the role of both components of the equation contribution in the overall flow system, alpha and beta are linked to the formula to emphasize the hydrostatic and the dynamic components of the formula:

where B is the width of the section of the tank, α, β are the parameters of the equation, A is the area of the transversal section, and h

b is the distance of the gravity center of the object from the free surface of the water, with A = h B.

A customized approach was implemented to optimize the formula’s performance by explicitly assigning specific coefficients. This tailored method aims to ensure a reliable representation of the underlying physical relationships while allowing the formula to accurately capture the subtleties of the phenomenon under study. By taking into account contextual variations and the conditions specific to each situation, this approach improves the formula’s sensitivity to local dynamics, thus ensuring more refined and representative modeling. Indeed, the integrated parameters α and β into the equation aim to calibrate the effect of each thrust component. α contributes to adjusting the water depth of the hydrostatic thrust, while β adjusts the velocity and water depth within the hydrodynamic thrust of water. To obtain the equation of the unit thrust as a function of their parameters, we can write Equation (1) as follows:

In order to obtain the unit thrust expression, after many manipulations of the equation, the incipient velocity formula is obtained as follows:

Therefore, the final equation of the unit thrust is written as:

In order to simplify Equation (7), a compact version of the thrust is introduced with slight adjustments. The constants—such as the unit thrust S/B and the specific weight of the water

—are grouped together in a single expression σ. This allows us to easily manipulate the equation, as well as facilitating the estimation of the integrated parameters.

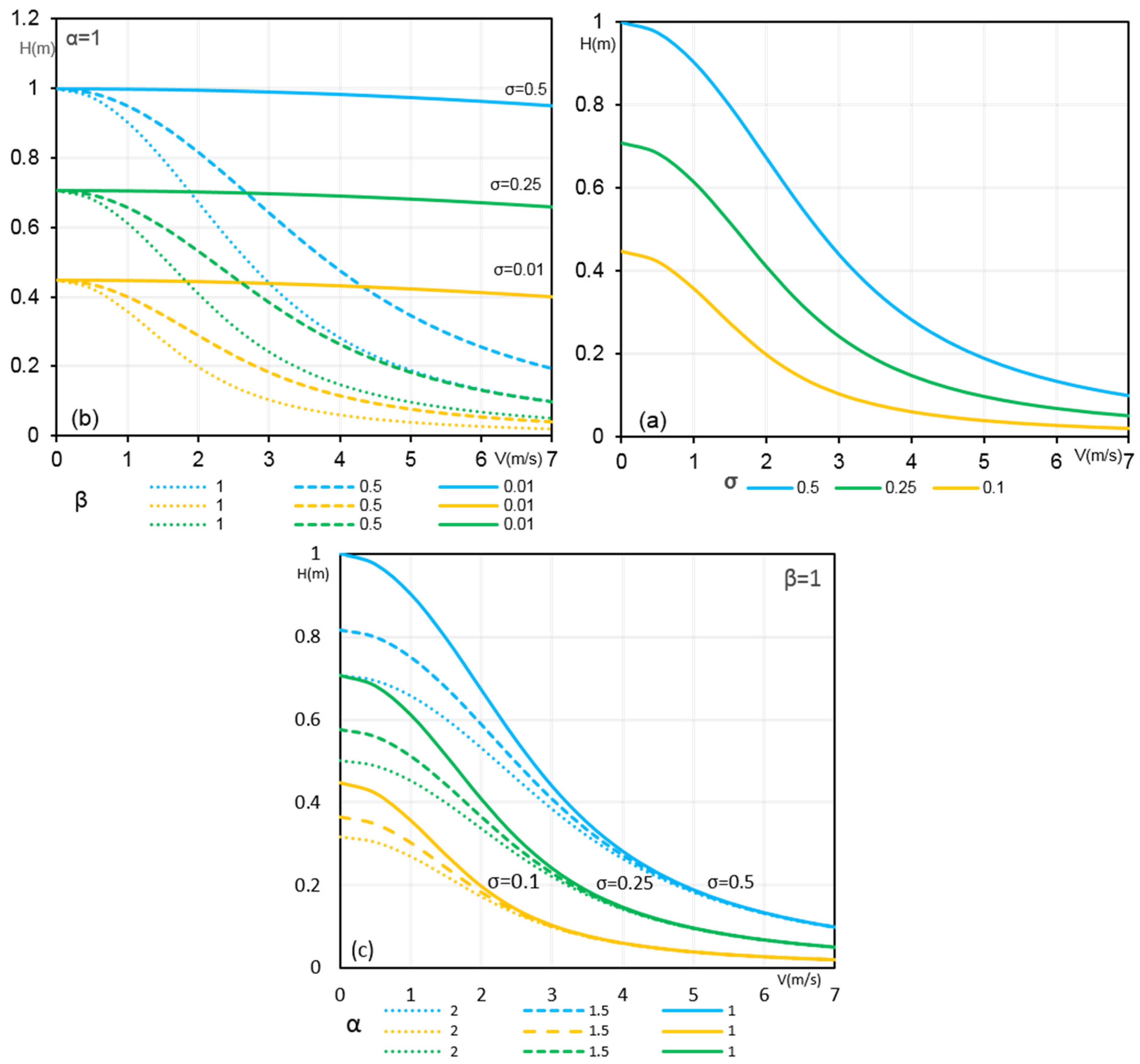

σ is a quantity that directly depends on the hydraulic couple, namely the water depth and the corresponding flow velocity. These two variables often exhibit an inverse relationship: when the water level is important, it specifically indicates a slow flow; however, when the flow velocity is important, the water depth tends to be very shallow. This inverse correlation is illustrated by the shape of the isoline curves in

Figure 1a, which shows that the parameter sigma varies according to the relative changes in water depth and velocity. σ can vary between 1 and 0. σ = 1 represents the normalized value of maximum instability according to the available experimental data, while 0 represents a minimum where hazard is negligible and cars are completely safe.

α and β are two key parameters that accentuate the importance weight and emphasize the contribution of each component of the sigma parameter. Namely, they calibrate the respective influence of the dynamic and the static contribution into the hazard factor. Beta represents the impact of water velocity into the applied force of water on the object,

Figure 1b; with beta = 1, the force depends directly to the velocity v and water depth h. When beta is modified, this affects the slope of the curve, which signifies that the force is modified for a given velocity (same velocity). In addition, if beta increases, the lateral action of the water increases more rapidly with the velocity of water. Alpha in

Figure 1c, can contribute to increasing or decreasing the effect of water depth, which impacts the value of sigma in the intercept of the curve. For a higher alpha value, the sigma isolines are translated by a curve of a general lower depth, and vice versa. For lower values, alpha can adjust the vertical pressure applied to an object, which involves the water column effect with regard to the weight of the object. We are therefore referring to buoyancy. In other words, these two coefficients (α and β) can increase or decrease the sensitivity of the hydrodynamic and hydrostatic action of the water on the submerged object. These parameters can be related to the shape characteristics of the object. For a resistant object, the parameter σ is less sensitive to the velocity, and for a less resistant object, the force is more sensitive to the hydrodynamic action or velocity.

2.2. Stability of Vehicles in Flood Water

2.2.1. Hydrodynamic Forces Exerted on a Vehicle in Flood Water

A parked vehicle under the effect of pressure and momentum of the horizontal forces of the flow, as defined in Ref. [

24], can lose its stability via two distinct hydrodynamic mechanisms (i.e., sliding and floating). The density of a watertight car compared to the density of the water is considerably small; since the upper part of the car is almost empty, a major part of the weight is located in the lower front side where the engine is installed [

38]. The vehicle floats when the buoyancy and lift are higher than the effect of the car’s weight. The sliding instability occurs when drag is more important than the resistance of the tires against the road surface. These modes of instability are linked in a cause–effect relationship to each other in the sense that the lift and buoyancy action can reduce the weight effect, favoring the sliding mechanism even with smaller water flow levels. According to Ref. [

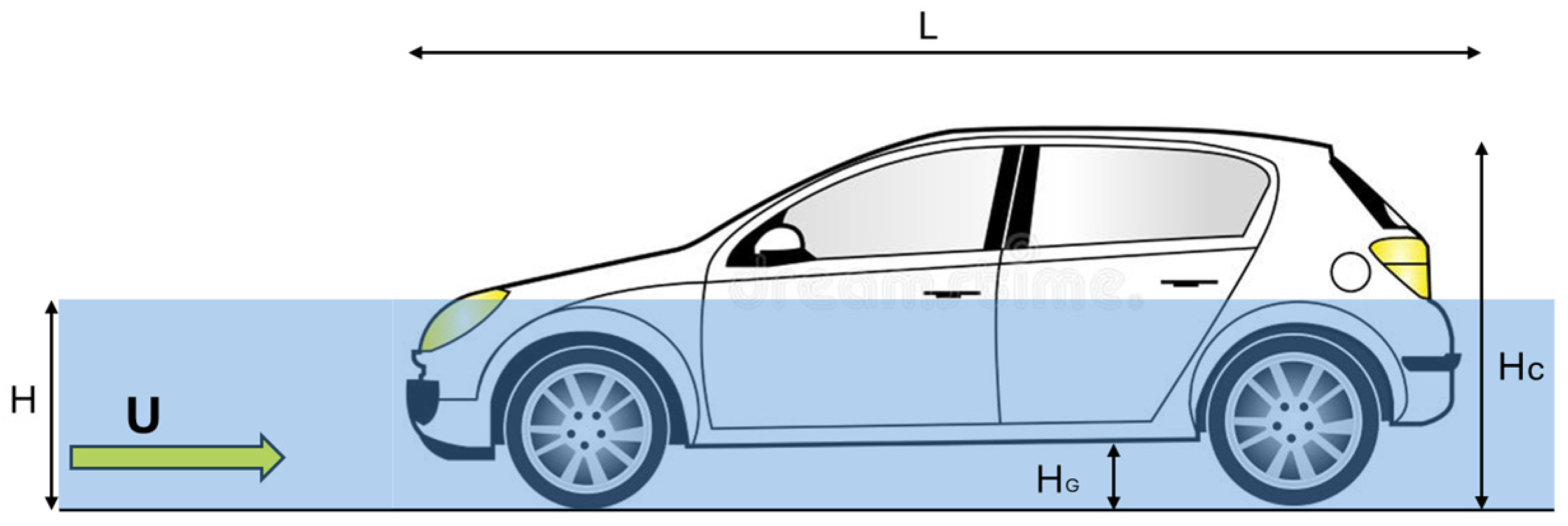

28], the interaction between the flood water and car presents the same similarities with the behavior of sediment transported in a river channel, and the same approach can be applied to vehicles. Thus, analyzing the forces acting on a flooded vehicle is crucial, which requires the specification of the vehicle dimensions (i.e., shape, volume, and density). The stability of a vehicle in a water flow can be depicted via a conceptual scheme representing its submerged fraction as a function of the water depth and the vehicle orientation relative to the flow, with the vehicle facing the incoming flow so that water first interacts with the front of the vehicle, progressively surrounding the body and increasing the water vehicle interaction as the depth rises, which directly influences the onset of instability, as shown in

Figure 2.

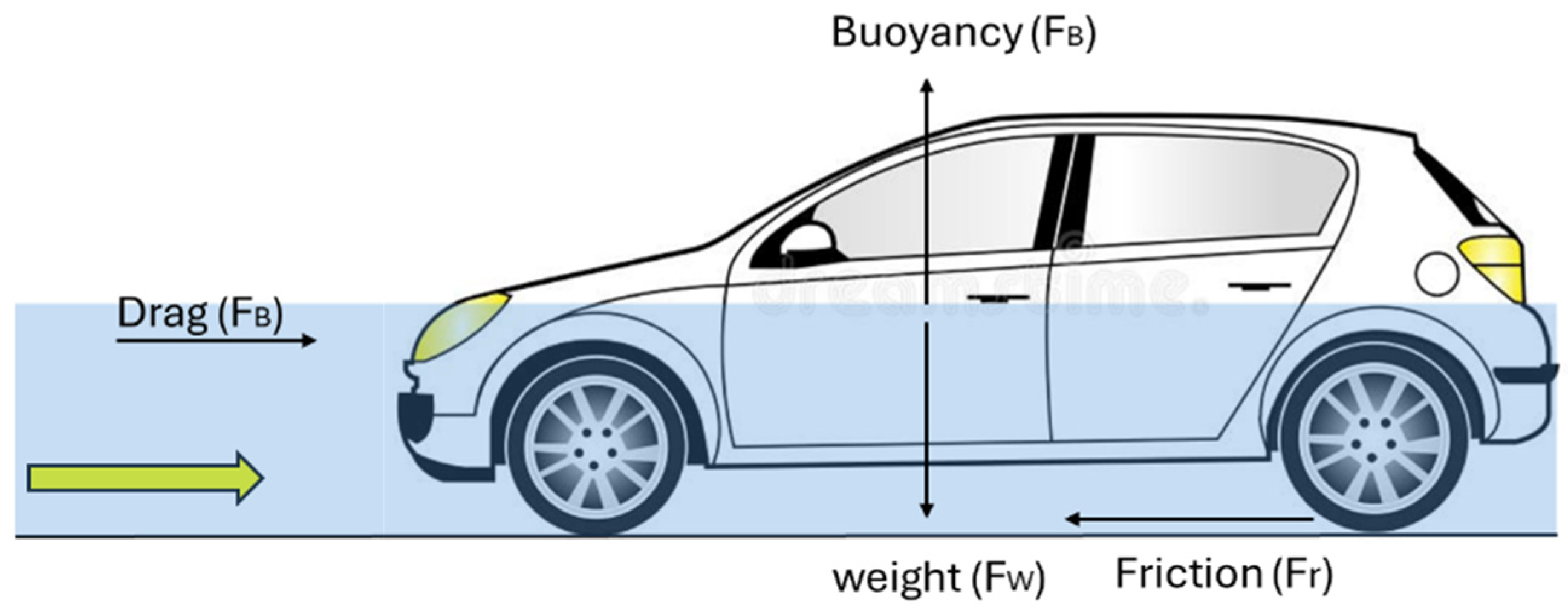

When a vehicle is parked on a flooded road, it is subjected to several forces: lift, drag, buoyancy, friction, and gravity. It is assumed that the wheels of a vehicle are all locked against any movement as it parks on a road; thus, a frictional force will be produced to resist the vehicle from sliding on the road surface.

Figure 3 illustrates the forces acting on a flooded vehicle. These forces are similar to those acting on a coarse sediment particle in a river [

28,

30]. Thus, the incipient motion of a vehicle can be assessed based on principles similar to those used in sedimentology.

The drag force is defined as follows:

where

ρ is the water density,

AD is the projected (profile) area of the vehicle impacted by water—expressed as A

D = w

c × h (w

c is the car width and h is the car submerged height),

CD is the dimensionless coefficient of drag,

CD has to be determined experimentally, and

V is the flow velocity [

37].

The lift force is defined as follows:

where

ρ is the water density;

V is the water velocity;

CL is the lift coefficient; and

A is the submerged area of the projection of the submerged part of the vehicle perpendicular to flow direction, expressed as

= w

c × l

c. V is the vertical velocity generated during the movement of the vehicle [

13,

30,

37].

The buoyancy is expressed as follows:

where

ρ is the density of water, g is the acceleration due to gravity, and V

s is the submerged volume of the vehicle (V

s = w × l × h).

The weight force is given as follows:

where

ρ is the density of the vehicle, g is the acceleration due to the gravity, and

Vc is the car volume (

Vc = w × l × h

c).

2.2.2. Incipient Instability of Vehicles in Flood Waters

Considering the case of a stationary vehicle as stated before on a flat ground, the instability condition is presented by forces balance in the direction of the flow. These forces are mainly categorized into vertical forces, F

H and horizontal forces, F

V [

15]:

where F

R is the frictional force and

is the friction coefficient.

Friction force is commonly defined as the product of the friction coefficient

and the normal force, which is the weight of the car (FG) minus the buoyancy (FB) and the lift effect (Li):

The effect of the lift force of a stationary vehicle is neglected, as there is no movement and the vertical force will be null. Therefore, the equilibrium of the forces becomes:

The expression of the incipient motion instability after subsuming the relative forces with their corresponding expressions from Equations (9), (11) and (12) is attained as follows:

Subsequently, an expression of the same variable is then obtained through the manipulation of Equation (8).

By combining Equations (17) and (18) after identifying the corresponding terms, we can write the following:

According to the equality established in Equation (19), the expression of the parameter beta is derived as follows:

This parameter governs the relative weight of the hydrodynamic component of the sigma criterion equation. Its influence becomes particularly significant under the conditions of high velocity and very shallow waters that tend to 0, which leads to the following:

The values of β can be calculated based on the car experiment studies that suggest the measured characteristics of different cars dimensions and can also be obtained from producers’ datasheets. A range of the variation of the parameter β can be estimated for the available cars as well as for the car categories that present dimension similarities. Knowing that, the friction coefficient is constant for all vehicles 0.25–0.75, according to the new data for static friction. Drag coefficient CD ranges between 0.4 and 1.38. These values are standard and can be adjusted according to the selection of the experiments of interest.

For simplification, the effect of the car density can be neglected, since the volume of the car is not easy to obtain. This is because cars are not of a defined, simple shape, and their mass is not equally and homogenously distributed over the entire car area. The frontal part is the densest owing to the presence of the engine. The cockpit part is largely empty. Rather than resting on the ground, the vehicle’s core stands on the tires, which directs water flow underneath the vehicle.

For this reason, it is assumed that the density of the vehicle is equal to that of water, and the product in this case

is equal to 1, which involves the relative density between the vehicle and the water flow. This is valid when the submerged volume of the car is small and the water depth is shallow. In the opposite case, watertightness of the vehicles must be taken into account [

14].

2.3. Data Analysis and Parameter Estimation

This analysis synthesizes an up-to-date set of data reported in previous research studies. A specific focus was attributed to experimental investigations that have tested the interactions of modern vehicles against water flow levels and their corresponding velocities in order to assess stability for the most commonly used cars.

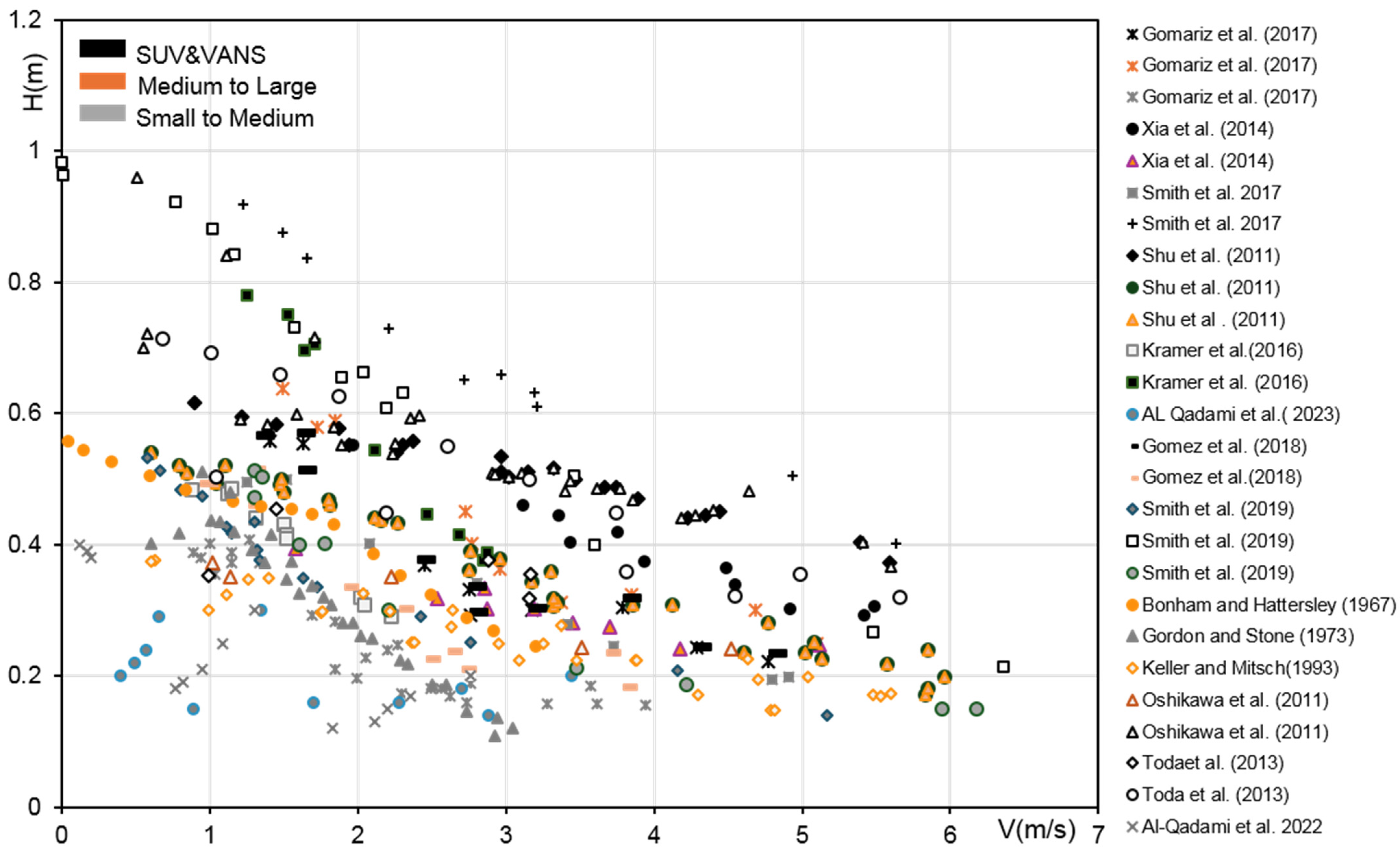

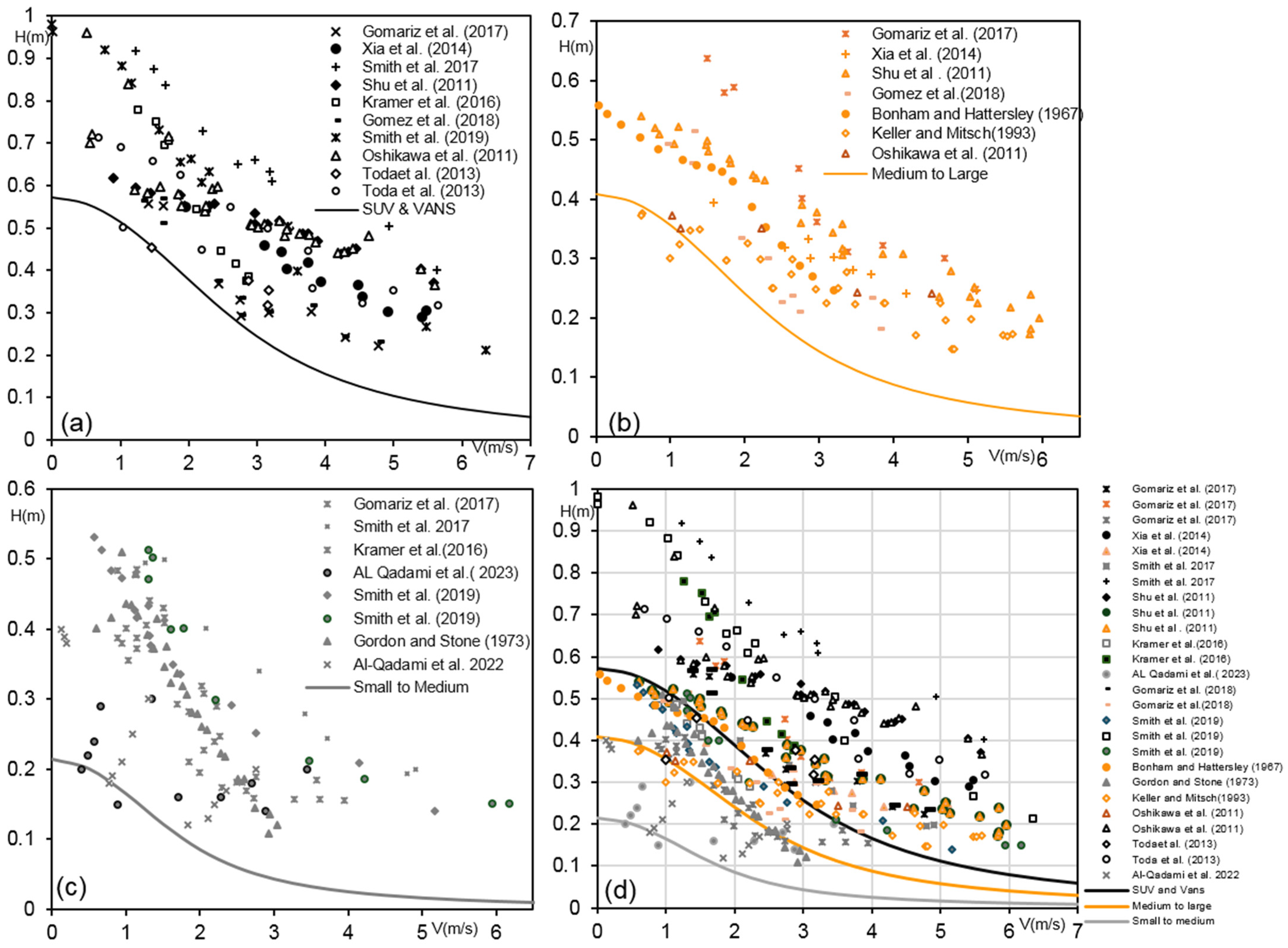

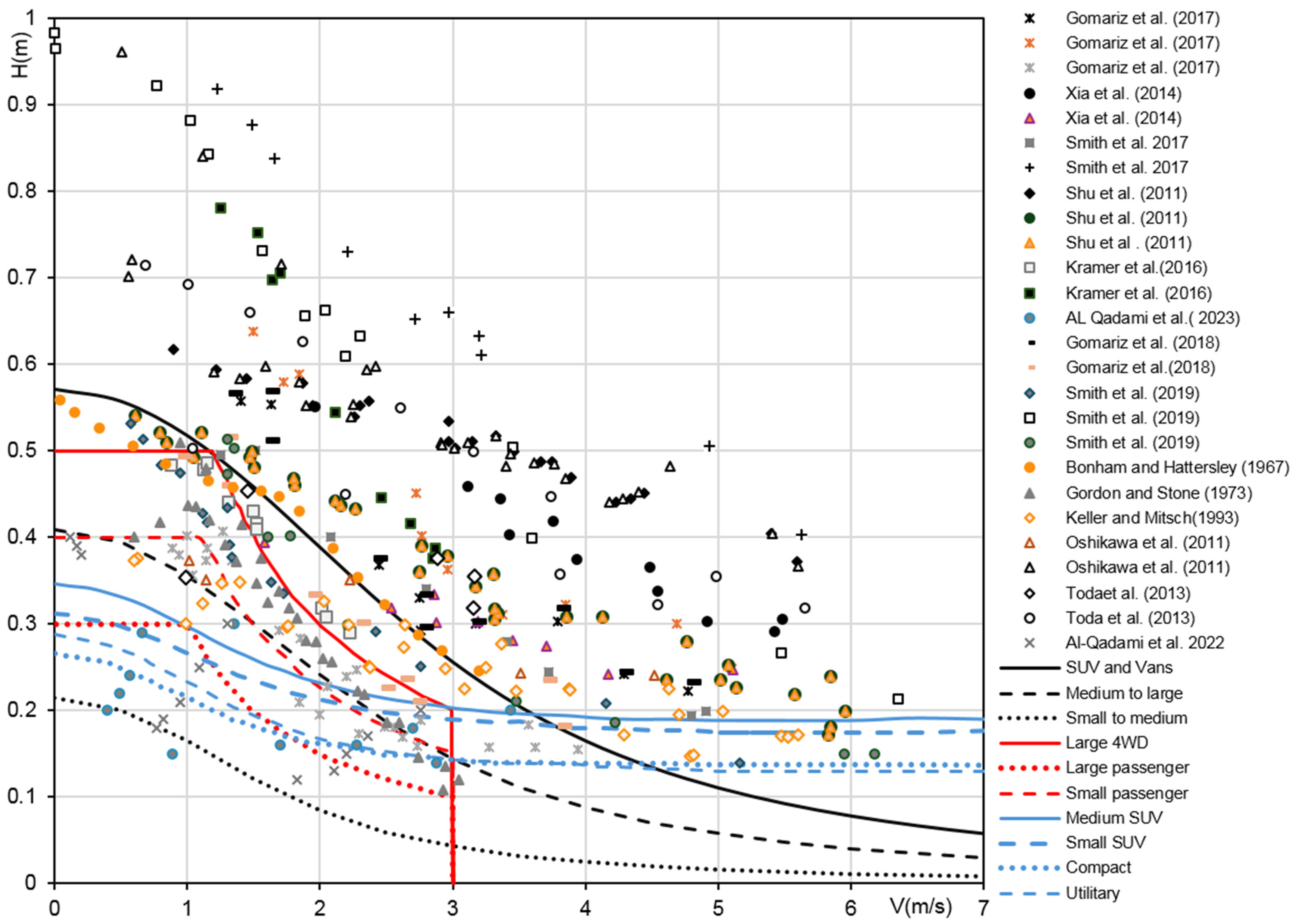

In the second step, all instability thresholds reported in the examined studies were collected. These thresholds are presented in

Figure 4 in the form of cloud data points. As one can notice, the flow depth of each group of points related to a given car category decreases gradually as the velocity increases. This interdependency report variation slightly changes from one tested vehicle to another, depending on the intrinsic properties of each single vehicle model and the test condition. It should be mentioned that not all cars show the same evolving tendency, in the sense that small city cars require less water depth and velocity to lose stability compared to large ones. For instance, the Parodua Viva model tested in Refs. [

35,

36,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46] demonstrated the highest affinity to instability among all the assessed cars due to its compact dimensions. Large cars appear to be the most resistant and safe during flood events, e.g., Nissan Patrol, which was tested in Refs. [

15,

47] on its full scale.

Vehicle stability data were derived from laboratory tests conducted in rectangular flumes, where vehicles were in a stationary state with locked wheels to prevent their movement [

29,

48,

49]. Stability conditions were evaluated based on water depth and incipient velocities. These data were collected from published experimental studies and research reports between 1963 and 2021. Although the data do not cover the full spectrum of existing vehicle instabilities, they reflect a representative sample of widely used vehicle types. They thus provide a reliable database for assessing and modeling vehicle instability under flood-like conditions. The data were subsequently filtered, and data related to small-scale prototypes (1:14, 1:18, 1:24) were converted to full scale (1:1), respecting Froude’s similarity laws, in order to ensure their representativeness at full scale and for homogenization purposes (Equations (22)–(24)).

where

Fr is the Froude number, m and

p subscripts are indication for model or prototype car,

v refers to the velocity, g is the gravitational acceleration, and

L is the characteristic length.

where Lr is the length ratio, L

p is the length in the prototype scale, and L

m is the corresponding length in the model scale. Therefore, water depths and velocities of the prototype are obtained based on the Froude number principle:

where L

r is the scale ratio, h

m and v

m are water depths and velocities of the model scale, and h

n and v

n are the same qualities of the prototype scale.

Figure 4.

Scatter plot of experimental data related to incipient instability in function of water depth and flow velocity of three different vehicle groups: Small to Medium, Medium to Large, and SUVs and Vans [

15,

21,

24,

25,

26,

29,

30,

31,

34,

35,

47,

50,

51,

52].

Figure 4.

Scatter plot of experimental data related to incipient instability in function of water depth and flow velocity of three different vehicle groups: Small to Medium, Medium to Large, and SUVs and Vans [

15,

21,

24,

25,

26,

29,

30,

31,

34,

35,

47,

50,

51,

52].

As part of this analysis, comprehensive data about the intrinsic characteristics of tested vehicles were gathered, for a total of 26 vehicles based on findings from 14 experimental studies [

15,

21,

24,

25,

26,

29,

30,

31,

34,

35,

47,

50,

51,

52]. These studies covered a large range of car types, ranging from small compact vehicles such as those tested in Refs. [

35,

43] to larger models, including emergency cars often classified as SUVs and vans. For a synthetic comparison, the vehicles are classified into three categories according to their physical shape: Small to Medium, Medium to Large, and SUV and Vans, following the classification guidelines recommended by scientists such as the authors of Ref. [

27].

The analysis involves, in addition, a range of hydrodynamic characteristics and physical quantities. Among these, we can find the drag coefficient, CD, which quantifies the hydrodynamic resistance of a vehicle when it moves through the water flow; a low drag is usually an indication of better aerodynamic efficiency. There is also the lift coefficient, CL; this parameter was not measured in most of the experiments. Under normal standard conditions, it is approximately equal to zero. However, it can be higher when the car is in movement. Since it represents the vertical force acting on the vehicle, a high lift coefficient may decrease the tire contact adherence to the road (friction), affecting stability in high-speed conditions. The friction coefficient plays an important role as well in balancing the drag force μ, especially when the road is rugged and the tires are textured. On the other hand, dimensional characteristics such as width, length, and height are all included in the investigation.

The source of data related to the cars’ geometric configuration and hydraulic properties are both obtained based on laboratory experiments, as the hydraulic incipient motion, and completed from official manufacturer specification sheets. The dataset covers the characteristics of a large range of different car models, including small-scale models, testing results, as well as prototypes. For this reason, part of the experimental results was validated based on Froude similarities in order to be correctly projected on prototypes (see previous section for details). Some geometrical data, especially those corresponding to old models or even several modern ones, could not be retrieved directly; in these cases, an average estimated value was used (i.e., lift coefficient), as shown in

Table 1.

The determination of the beta parameter requires prior knowledge of all these variables describing the geometry of the vehicle together with the hydrodynamic coefficient (CD) and the friction between the road surface and the tires (μ). A range of beta parameters is estimated between 0.2 and 0.9 based on the dimensions of the studied vehicles. These values can be calibrated referring to the experimental stability conditions.

2.4. Model Calibration and Definition of the Threshold Curves

The model calibration and threshold curve definition involved the determination of the stability threshold for each car category. Upon a meticulous analysis of the experimental data, Equation (8) was used, and the hazard parameters were determined accordingly, which allows us to identify the critical values that characterizes the onset stability condition. The calibration of the curve of the parameter equal-values (isolines) were then obtained by integrating the experimental outcomes based on stability conditions and the insights obtained with the physical approach. The minimum value was selected as embodying the critical threshold delineating the stability boundary corresponding to the onset of vehicle movement under the relative hydrodynamic conditions. This threshold was determined through the analytical resolution of the governing equation, reflecting the limit constraints describing the system equilibrium state, between the vehicle’s dynamics and the surrounding hydraulic conditions, then the values of water depth and velocity were obtained accordingly.

It was necessary to adjust the parameter beta afterward in order to find the fitting value that defines the critical threshold among the values estimated previously. The definition of the threshold curve was obtained based on the dataset of the SUV and Vans vehicle subcategory. It was taken as the reference category, as this group of cars is the most resistant compared to other vehicle groups. Based on the latter group, the parameter values were fixed and transposed for the two other subcategories for validation in order to obtain this threshold function. The equation of the criterion sigma was used. The objective was to find the right values for both model parameters. The alpha parameter is the coefficient that emphasis the effect of the water depth in the model equation; this coefficient can be estimated through the equilibrium of forces, particularly between the car’s weight and the buoyancy force. Since the aim of the present work focuses on instability due to the water hydrodynamics, the alpha value is set to be α = 1 optimally for a hydrostatic that depend on water depth only.

The beta parameter, on the other hand, was calibrated and optimized based on the previously obtained values of alpha and sigma for each corresponding value of sigma. Thus, the stability limit of the SUV and Vans subcategory was defined. The minimum fit equation was determined by setting the optimal value of beta to 0.6, after substituting the corresponding variable values to ensure that beta met the minimum of the sigma condition. The sigma values defining the limit curve were established (see next section). The sigma values refer to the minimum observed values of water depth and velocity across all experimental data.

4. Discussion

Converting water depth and flow velocity, outcomes of experimental studies, into indicators of vehicle instability is mandatory to ensure safety [

31]. Research has repeatedly demonstrated that these parameters, in some cases expressed as Froude number, form the basis of physics-driven approaches to predict the likelihood of vehicles to be swept away during flood events [

13,

21,

23,

27,

29,

30,

31,

37,

38,

47,

48]. There is still a real gap in the scientific literature regarding this issue. Very limited studies have addressed it [

8,

20,

33,

34,

55], and most of the existing studies rely on limited experiments for specific, defined vehicle models [

12,

28,

30,

49,

57] and/or consider only one or a few of the problem aspects.

On this basis, a multi-perspective approach was employed to elaborate a new model involving key aspects such as the physical process of the phenomena, hydraulic flow conditions, and the object-based characteristics of the submerged body, namely vehicles, as well as integrating the largest and most up-to-date instability data experiments up to now for calibration and validation. This criterion is grounded on an effective theoretical foundation, developed to be generalizable and flexible, providing a synthetic representation of instability mechanisms through the dynamic coupling of hydraulic forcing and vehicle response. This is unlike simplistic empirical formulations, which lack explicit physical meaning and often do not include the object characteristics effect.

A notable example of the simplified criterion is the

D∙V product number [

21,

27,

52], discussed previously in the Results section, which entails merely critical values for both water depth and velocity to yield an estimation of the hazard under typical circumstances. Kramer et al. [

31] proposed a decisive safety criterion that is based on relevant physical principles, which is the total head energy h

E = h + V

2/2 g obtained as a result of a detailed experimental tests. However, the obtained parameter takes into account only the stability thresholds of one car model. The same concept was used in Ref. [

23] in a flexible parameter called W, which integrated both the total energy head with momentum by combining in the same expression both water depth and velocity, expressed through the Froude number. Another innovative initiative is defined as the mobility parameter, θv, in Refs. [

38,

61] with the experimentally derived data documented in Refs. [

28,

29,

30], including measurements performed on seven vehicle prototypes of different scales (i.e., 1:14, 1:18, 1:43) instead of one car model compared to other criterions. Nevertheless, the amount of data remains limited, which was also declared by the author.

Overall, the proposed criterion thereby provides a coherent and physically justified measure of flood-induced instability. Its interoperability and large representativeness across a large spectrum of vehicle models would allow for facilitating its integration into flood vulnerability models and risk mapping [

37] while enabling the definition of generalized stability thresholds that overcome the limitation of earlier empirical approaches documented in the literature. Nevertheless, the proposed vehicle stability criterion is conditioned by the experimental data available in the literature, which are predominantly obtained under controlled and idealized conditions. These datasets mainly involve stationary vehicles on horizontal surfaces and uniform flow regimes, which may bias stability thresholds toward conservative estimates. As a result, certain real-world effects such as vehicle motion, unsteady flow conditions, and complex surface interactions remain insufficiently represented. Yet, within the bounds of the available data, the model provides a consistent assessment of vehicle stability.

Future Paths

Possible future research paths can (i) extend the application of this criterion beyond vehicles to include other exposed items such as pedestrians or urban infrastructure affected by flooding, as demonstrated in Refs. [

12,

23,

62]. This latter applied this approach to waste containers. (ii) Particular attention can also be devoted to instability through buoyancy and flotation mechanisms. (iii) Exposure and susceptibility can be combined within the damage estimation framework in order to advance the risk of flood assessment through simulations of case study area. (iv) Upcoming work will also address the integration of additional variables associated with flood-prone environments into the formula of the hazard parameter, or associated with the vehicles themselves. Indeed. It is recommended to incorporate a wider range of complex scenarios into vehicle stability analysis [

20]. For instance, including road gradient variations and hydrodynamic regimes is important in these investigations; additionally, focus should not be limited to stationary vehicles but also consider forward-moving prototypes (nonstationary) to better reflect real-world traffic conditions, because this limitation may lead to conservative threshold curves [

47]. In this regard, using a three-dimensional modelling approach to simulate scenarios of flood conditions is a step forward and can be a relevant future perspective to enhance the applicability of its evaluations.

5. Conclusions

This research developed a new hazard parameter to assess the instability of vehicles exposed to flow inundation in urban environments. The innovation of this parameter is grounded on a hybrid physics-based framework with solid physical interpretability, allowing flood hazard assessment based on flow depth and velocity. Its generalizable formulation makes it independent of any single vehicle configuration and transferable across different vehicle categories.

This is achieved through a process of complementary approaches implemented by integrating the combined effect of vehicle geometry features and the hydrodynamic forces acting on it to investigate the governing instability mechanisms. The formula requires a limited number of hydraulic parameters to accurately estimate critical instability thresholds during flooding events. The critical instability threshold values, expressed as functions of water depth and flow velocity, were defined based on experimental data from vehicle tests conducted in hydraulic laboratories. The involved model parameters were optimized accordingly. And, the index of stability is obtained for three categories of tested vehicles.

Comparison between the new model outcomes and two other referential stability criteria demonstrated an overall good agreement, with a better performance depicted by the new model. This confirms the relevance of the proposed hazard parameter. In summary, the model proved to provide an effective and generalizable hazard model that can predict the instability of nonspecific vehicles in flooded conditions. The proposed criterion can be directly integrated into two-dimensional flood models, urban flood hazard mapping, and flood risk and damage assessment frameworks. The model is also pertinent for real-time applications within early warning systems. It provides a quantitative basis for identifying hazardous road segments and supports decision-making related to traffic management, road closures, and emergency response during urban flood events.